Abstract

Patient

Female, 37-year-old

Final Diagnosis

Catamenial pneumothorax • endometriosis • infertility

Symptoms

Dysmenorrhea • shortness of breath

Clinical Procedure

Diaphragm repair • diaphragmatic endometriosis resection • pleurodesis • thoracotomy • video-assisted thoracic surgery

Specialty

Obstetrics and Gynecology

Objective: Unusual clinical course

Background

Catamenial pneumothorax (CP) is the most common manifestation of thoracic endometriosis syndrome, typically managed with hormonal therapy to suppress ovarian function and prevent recurrence. However, this approach conflicts with pregnancy planning, creating a therapeutic dilemma. While previous reports have discussed CP management, limited evidence exists on long-term strategies that balance disease control with fertility preservation. This case report discusses the use of a GnRH agonist as an alternative to conventional hormonal therapy, demonstrating its potential to delay CP progression while maintaining reproductive potential.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman, P0A0, presented with shortness of breath and a history of dysmenorrhea. A decade earlier, she had been diagnosed with pelvic endometriosis and a similar pneumothorax episode. She declined continuous hormonal therapy to preserve fertility and was instead treated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist. Ten years later, she developed CP and underwent pleurodesis with excision of endometriosis implants. Her postoperative course was uneventful, and she resumed pregnancy planning. This outcome aligns with emerging evidence suggesting that GnRH agonists offer prolonged CP control without compromising fertility, contrasting with the higher recurrence rates seen in patients who do not receive medical management.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates that prolonged CP control is feasible using a GnRH agonist, providing an alternative to continuous hormonal therapy in women prioritizing fertility. Future research should focus on defining the optimal duration of GnRH agonist treatment, identifying patient selection criteria, and evaluating long-term reproductive outcomes in CP patients who do not receive standard hormonal suppression.

Keywords: Endometriosis; Hormone Replacement Therapy; Infertility, Female; Pleurodesis; Pneumothorax

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, non-malignant disorder characterized by abdominal pain during menstruation, driven by a combination of genetic, hormonal, and immunological factors that enhance endometrial cell invasion and angiogenesis impairment [1,2]. It affects approximately 5% to 15% of reproductive-aged women and, although primarily pelvic, it can manifest in extrapelvic locations such as the thoracic cavity [3]. Thoracic endometriosis (TE) is a rare but notable form, in which endometrial tissue grows in the pleura, lungs, diaphragm, or airways [3,4].

The most frequent clinical presentation of TE is catamenial pneumothorax (CP), a spontaneous lung collapse that occurs during or within 72 hours of menstruation onset [5]. CP is marked by chest pain and respiratory distress, and can coexist with pelvic endometriosis, infertility, or other thoracic symptoms like hemothorax or hemoptysis [5,6]. Due to its overlapping features with primary spontaneous pneumothorax and low awareness, CP often remains underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed [7,8].

Accurate diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion in women with recurrent pneumothorax and a history of endometriosis [9]. Diagnostic tools include chest imaging, video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS), and histological confirmation through biopsy, with immunohistochemical markers like cytokeratin-7 and hormone receptors aiding detection [6]. Notable findings can include diaphragmatic fenestrations or pigmented lesions. Histopathology often reveals eosinophilic infiltration and macrophage dominance [9].

The management of CP primarily focuses on treating the pneumothorax and minimizing the risk of recurrence [10]. Hormonal therapy, often used to suppress ectopic endometrial activity, is a mainstay of treatment [11]. However, it poses significant challenges for women seeking to conceive, as it can interfere with ovulation and delay fertility plans [12]. The absence of standardized clinical guidelines for the management of CP in infertile women necessitates an individualized, multidisciplinary approach. This case report explores the management of catamenial pneumothorax (CP) in a woman desiring pregnancy. After receiving a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist for intrauterine insemination but no other hormonal therapy, she developed progressive CP over 10 years. This report shows the clinical complexity of CP in the context of infertility, illustrating the critical need to balance effective symptom control with strategies aimed at preserving reproductive potential. Unlike conventional treatment approaches that prioritize hormonal suppression, this case underscores the need for individualized strategies that balance CP control with fertility preservation.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman, P0A0, came to Margono Hospital referred from Susilo Slawi Tegal Hospital due to shortness of breath. She had been experiencing acute shortness of breath since April 16, 2024. The shortness of breath was not affected by changes in position or weather. She denied symptoms of fever, productive cough, and runny nose. The shortness of breath typically appeared on the third day of the menstrual cycle. She had no history of chronic lung disease or trauma to the chest and abdomen. Previously, she underwent a self-examination with a chest X-ray and consulted a pulmonologist, who advised going to the emergency department of the hospital. She had water seal drainage (WSD) placed on April 20, 2024. However, a follow-up X-ray after 24 hours showed that the lung remained collapsed. Another follow-up X-ray was done 24 hours later, but there was no improvement. She was then referred to Margono Hospital for further management.

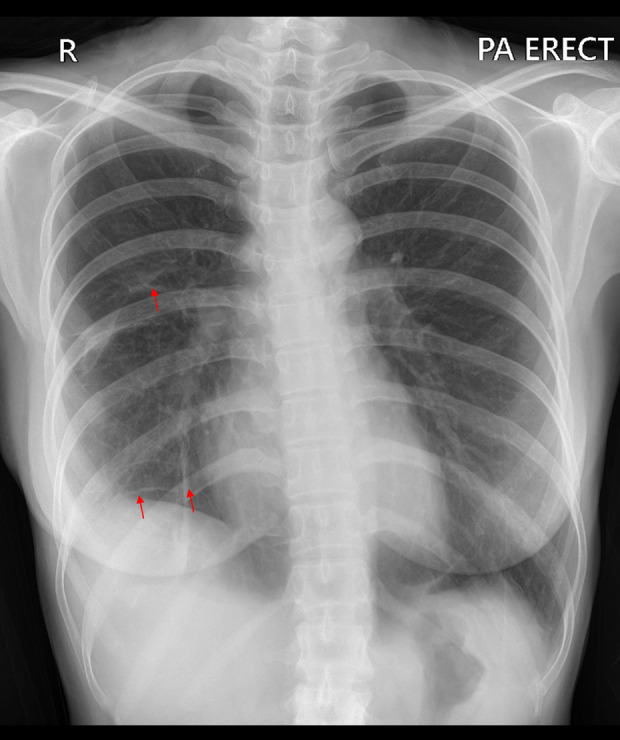

The patient had been having shortness of breath since 2014, and it worsened during the menstrual cycle and disappeared after menstruation. At that time, chest X-ray and ECG results were within normal limits. In July 2023, she had the first acute episode of shortness of breath and sought treatment at RSU Muhammadiyah Tegal. A chest X-ray has done as a referral hospital procedure. The result showed lucency around the edges of the lungs, absent lung marking, mediastinum shift to the opposite, air fluid level in pleural space, and deep sulcus sign, and increased rib separation revealed pneumothorax. Then, WSD was placed on the right lung for management, which only released air without fluid (Figure 1).

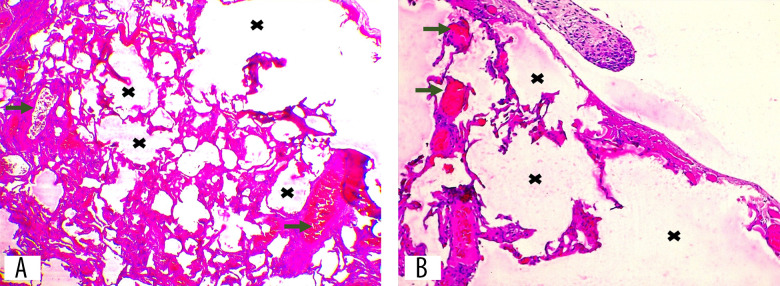

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray on first hospital admission. Yellow arrow indicates increased rib separation; red arrow shows the deep sulcus sign; black arrow highlights air in the right hemithorax displacing both the diaphragmatic dome and the anterior costophrenic angle, indicating a large right-sided pneumothorax; the green arrow demonstrates lucency outlining the lung margin.

Three days later, she was referred to RS Susilo Slawi Tegal because the symptoms did not improve. A follow-up chest X-ray showed the lung remained collapsed. The patient was observed twice for 72 hours, with follow-up X-rays. The results revealed no improvement (Figure 2).

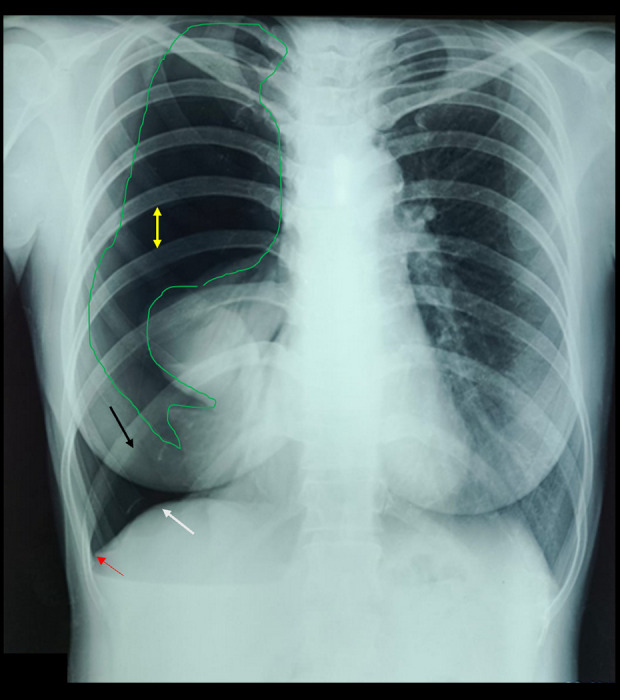

Figure 2.

Follow-up chest X-ray from Soesilo Slawi Tegal Hospital shows a massive right pneumothorax. Yellow arrow indicates increased rib separation; green arrow highlights lucency along the lung margin.

On the 12th day of WSD placement, it was decided to remove the WSD because the lung had not completely expanded. She received routine medication from a pulmonologist (antibiotics, methylprednisolone) and a surgeon (analgesics) afterward. She continued regular follow-ups until October.

The patient experienced menarche at the age of 12 with a normal menstrual cycle. She first experienced dysmenorrhea at the age of 27. The symptoms worsened during the menstrual cycle and disappeared afterward. She also experienced pain during defecation but denied having bloody or mucous stools. In 2017, she was diagnosed with endometriosis via ultrasound examination. She chose to undergo immediate pregnancy planning because she had been infertile for >10 years; therefore, assisted reproductive technology by intrauterine insemination was planned and contraceptive hormonal management was not given.

In 2017, she underwent fertility treatment, taking clomiphene citrate for 1 year. She then continued the fertility program with a different doctor, adding antioxidants for another year. In 2021, she patient underwent her first cycle of insemination with choriogonadotropin injection (hCG recombinant) at RSUD Tegal. In 2022, she had her second cycle of insemination with different injections by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist at RSUD Kariadi. The first IVF cycles consisted of recombinant hCG (Choriogonadotropin alfa, ovidrel 250 mcg, Serono) 36 hours prior to OPU. Subsequent cycles consisted of co-administration of GnRH agonist (Triptorelin acetate, decapeptyl 0.2 mg, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) and recombinant hCG (250 mcg), at 40 and 34 hours, respectively, prior to oocyte retrieval. The result of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) examination after injection was 1.27 ng/mL.

The patient had no history of chronic lung disease in her family or household. The patient was employed as an internal medicine nurse, and wore a mask during her daily work. During admission at Margono Hospital, she underwent several examinations due to shortness of breath. On physical examination, bilateral lung auscultation revealed rhonchi and wheezing. Abdominal examination showed no enlargement and no tenderness. To rule out infectious causes, sputum culture testing was performed, which was negative for tuberculosis, and Xpert MTB examination did not detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A chest X-ray (Figure 3) was performed in accordance with hospital protocol, revealing normal bronchovascular markings. Following the insertion of the water-seal drainage (WSD), the patient showed signs of improvement. To further evaluate the pneumothorax, a non-contrast thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 4) was performed at the request of the cardiovascular thoracic surgeon. The right lung showed no visible rims of gas around the lung edges, bulla, blebs, emphysema, pleural effusion, or air bubbles, confirming minimal pneumothorax.

Figure 3.

Follow-up chest X-ray shows minimal pneumothorax with water seal drainage in place. Yellow arrow indicates the drainage tube; red arrow shows reappearance of bronchovascular markings in the previously avascular pulmonary region.

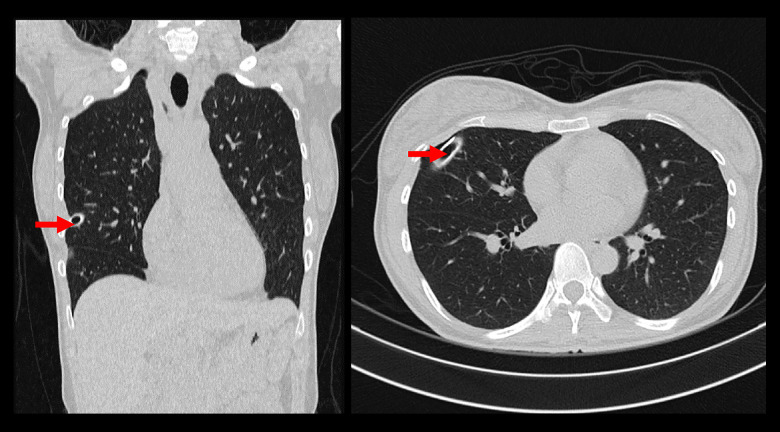

Figure 4.

MSCT Thorax CT scan with contrast showing minimal right pneumothorax (on chest tube), and no masses/consolidations were seen in the bilateral lung. Red arrow shows a minimal pneumothorax.

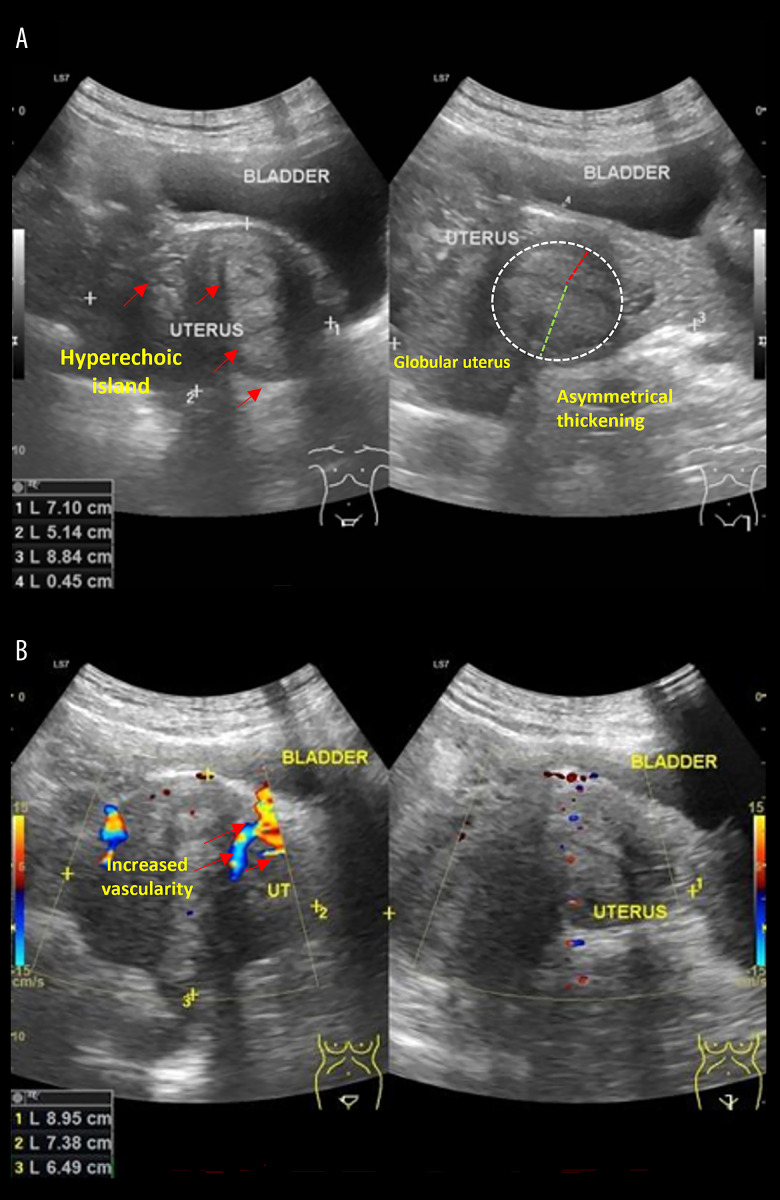

Additionally, a pelvic ultrasonography (Figure 5) was performed by the obstetrician to assess uterine features. The scan revealed uterine enlargement with a globular shape (7.1×5.1×8.8 cm), inhomogeneous density, hyperechoic islands, and increased intralesional vascularity, suggestive of adenomyosis or endometriosis.

Figure 5.

Ultrasonography result in referral hospital. (A) Gray-scale ultrasonography shows hyperechoic islands (red arrows) within the uterine parenchyma, a globular uterine shape, and asymmetrical thickening of the uterine walls (dashed white circle), indicative of possible adenomyosis and endometriosis. (B) Doppler ultrasonography demonstrates increased vascularity (red arrows) within the uterine lesion (perilesion), suggesting endometriosis.

To manage the condition, a pleurodesis thoracotomy was performed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a fertility and endocrinology subspecialist, a cardiovascular thoracic surgeon, and a pulmonologist. During the procedure, pathology biopsy samples were collected from the middle pulmonary lobe bullae and diaphragm wall. The patient underwent VATS for endometriosis cauterization, thoracotomy, pulmonary resection (bullae), diaphragmatic endometriosis resection, diaphragm repair, pleurodesis, and WSD placement.

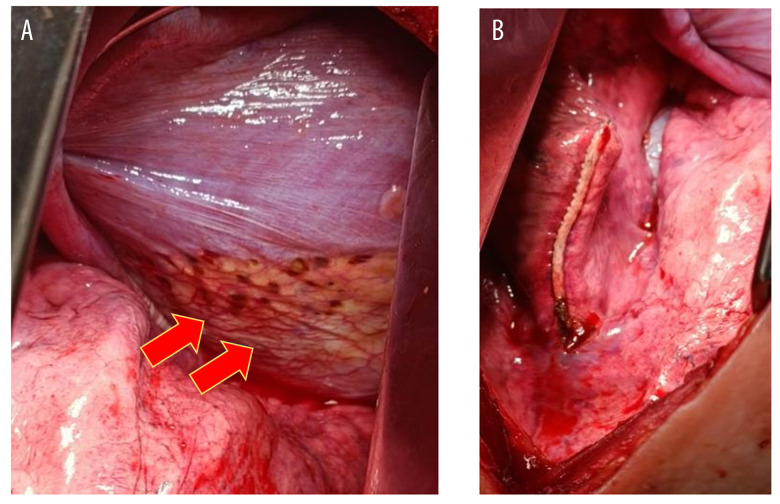

Upon surgical inspection, diaphragmatic endometriosis lesions were observed (Figure 6A, yellow arrow), appearing as superficial “powder-burn” or “gunshot” lesions with a dark-brown coloration on the diaphragm. After resection, the diaphragm was surgically repaired (Figure 6B). The macroscopic specimen collected (Figure 7) was sent to the laboratory for histopathological examination to confirm the diagnosis.

Figure 6.

Intraoperative findings. (A) Before endometriosis resection. (B) After endometriosis resection. Red arrow indicates endometriosis implant on the thoracic cavity.

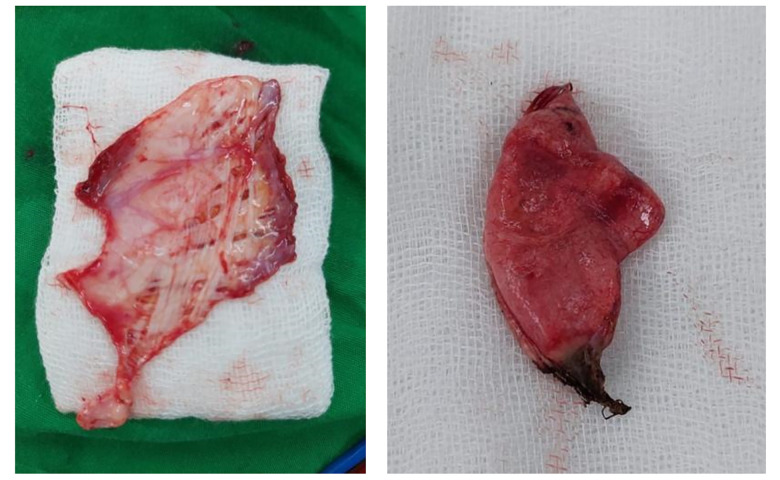

Figure 7.

Specimen findings of endometriosis tissue from thoracotomy.

The biopsy results from thoracotomy showed the diaphragm wall preparation exhibited muscle bundles, fibrous connective tissue, and fat. Within this, there is a noticeable presence of hyperemic enlarged endometrial stroma, which was in contact with hemosiderophages and was accompanied by hemorrhage. An examination of the middle lung revealed bronchi and alveoli that were enlarged and congested with an excessive amount of blood flow. Most of the alveoli show evidence of disintegration, although there were no observable indications of malignancy. The biopsy results indicated the presence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and pulmonary atelectasis. Figures 8 and 9 show the histopathology results of the biopsy.

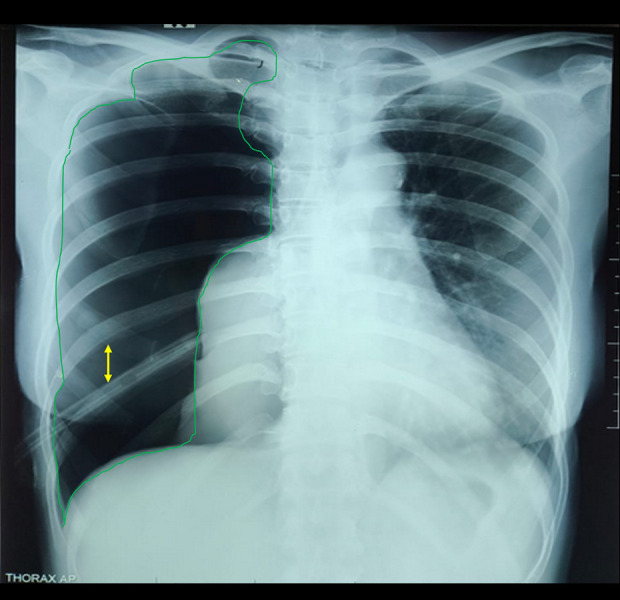

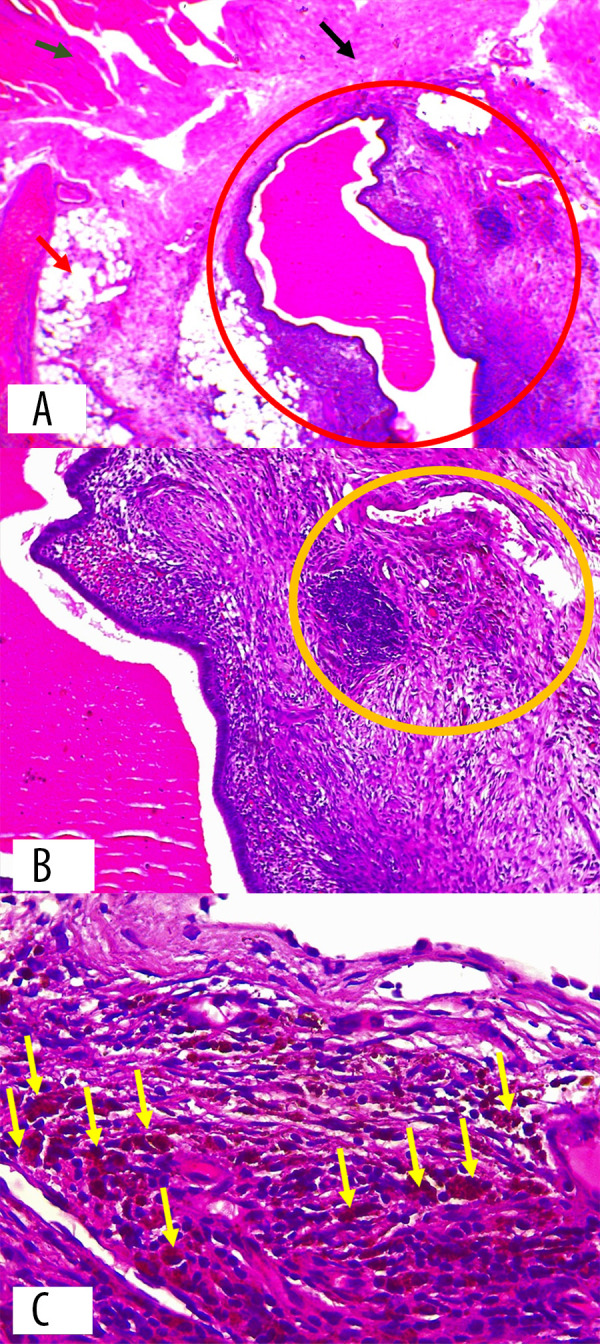

Figure 8.

Histopathology result of diaphragm wall. (A) Endometrial glands and stroma (red circle) located between diaphragmatic muscle bundles (green arrow), fibrous connective tissue stroma (black arrow), and adipose tissue (red arrow) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 40× magnification). (B) Endometrial stroma with hemorrhage and hemosiderin-laden macrophage infiltration (yellow circle) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 100× magnification). (C) Hemosiderin-laden macrophages with brownish-red stained cytoplasm (yellow arrow) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400× magnification).

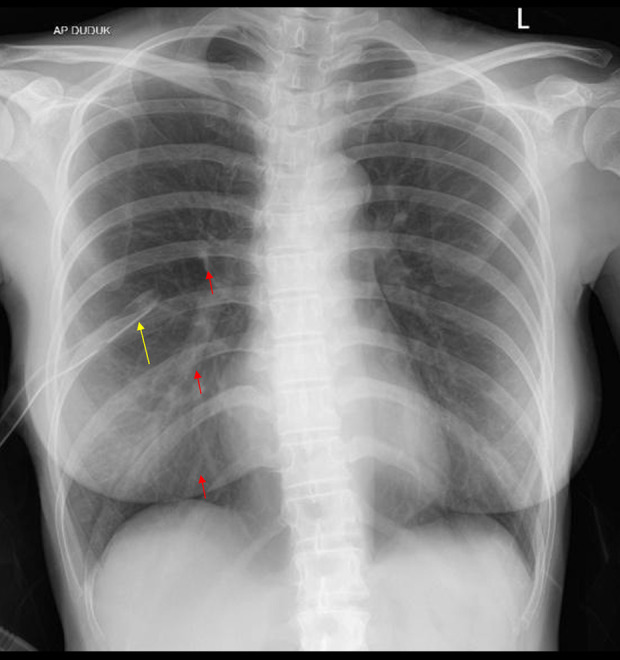

Figure 9.

(A, B) Edematous alveolar tissue with vascular proliferation and dilation (green arrow). Severe alveolar distension (black cross) indicates pneumothorax. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 40× magnification. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 100× magnification.

Postoperative Follow-Up

The patient’s postoperative status was satisfactory and she expressed a persistent desire to proceed with her pregnancy planning strategy. The doctor decided to proceed with the IUI plan and administered 2 shots after the procedure. The follow-up examination at the polyclinic revealed that the patient did not report any shortness of breath. The chest X-ray result showed a normal bronchovascular pattern (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Postoperative chest X-ray shows no signs of progressive pneumothorax. The red arrow indicates visible bronchovascular markings.

Discussion

The management of CP has 2 unique objectives: primary and secondary. The primary objective is to evacuate pleural air using aspiration and insert a tube. Secondary objective is administration of hormones after the procedure to suppress secretion of growth hormone. Effective surgical intervention entails blebectomy of all bullae, pleurodesis, pleurectomy, and suturing the diaphragm after excision of all suspected endometriosis lesions [13].

Endometriosis, characterized by development of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus, is the most common pathological condition associated with catamenial pneumothorax, but the exact cause is unknown. Endometriosis typically presents as a pelvic cul-de-sac, resulting in various pelvic pain symptoms and reproductive complications. It can present in 4 specific forms within the thoracic cavity: catamenial hemoptysis, endometrial stromal nodules in the visceral pleura or lung tissue, and catamenial hemothorax [10]. The exact mechanism by which ectopic endometrial tissue infiltrates the thorax remains unclear and there are several competing theories. The first theory was proposed by Sampson, who documented the first case in 1927, describing retrograde menstruation with implantation in the peritoneum and transdiaphragmatic migration through fenestrations induced by endometriosis [13]. The second theory involves metastatic spread of endometrial tissue through the venous or lymphatic system to implant elsewhere in the body [8,14]. The third involves coelomic metaplasia of undifferentiated stem cells into endometrial tissue, since both the abdominal and thoracic cavity are covered by the coelomic membrane [14]. The precise etiology of catamenial pneumothorax remains unclear, perhaps because, similar to its intrauterine equivalent, ectopic endometrial tissue is affected by the various phases of the menstrual cycle and can discharge air or blood into the pleural cavity, which can cause recurrent spontaneous hemothorax or pneumothorax. Further influencing factors may include the abrupt rupture of small sacs, the breakage of pulmonary air sacs resulting from the constriction of minor airways due to prostaglandins, and the absence of a protective barrier in the cervix, which permits air to pass from the reproductive system through minute apertures in the diaphragm [6].

Several hypotheses explain the pathogenesis of thoracic endometriosis, including retrograde menstruation, coelomic metaplasia, lymphovascular embolization, and direct transdiaphragmatic migration of endometrial cells [10]. The migration hypothesis suggests that clockwise peritoneal fluid flow directs endometrial cells toward the right hemidiaphragm, where they implant and form lesions [15]. The predominance of right-sided thoracic endometriosis and diaphragmatic involvement in chronic pain support this hypothesis [11]. This is consistent with our case, in which the patient exhibited right-sided pneumothorax with diaphragmatic involvement, supporting the concept of direct transdiaphragmatic migration. Table 1 summarizes selected case reports on catamenial pneumothorax and thoracic endometriosis related to our case.

Table 1.

Summary of selected case reports and series on catamenial pneumothorax.

| Author (year) | No. of CP patients | Symptoms | Side involved | Diaphragmatic lesions | Visceral pleural involvement | Histological endometriosis | Hormonal therapy | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph and Sahn (1996) [18] | 28 | Chest pain, dyspnea, recurrence around menses | Mostly right | ~40% with diaphragm defects | ~30% pleural involvement | 31% confirmed | Various regimens | Not detailed |

| Marshall et al (2005) [16] | 8 | Chest pain, dyspnea, cyclic symptoms with menses | 100% right | 5 with diaphragmatic implants, 4 with holes | 2 with pleural implants | Confirmed in some cases | GnRH agonist more effective than OCP | 37.5% |

| Alifano et al (2007) [8] | 5 | Chest pain, dyspnea, recurrence with menses | 27 right/ 1 left | 22 with fenestrations or nodules | 11 with visceral pleural nodules (14%) | 64% confirmed | GnRH agonist (6 months) post-op | 32% |

| Visouli et al (2012) [17] | 110 (80 CP) | Dyspnea, pleuritic pain, menses-associated CP | 100% right | Multiple fenestrations and nodules | 1 lung bleb with hemosiderin | Suggestive, not confirmed | GnRH agonist (1 case); others unclear | Not reported |

| Legras et al (2014) [21] | 229 (80 CP) | Dyspnea, pleuritic pain, menses-associated CP | 63% right | 43/54 (80%) with diaphragmatic lesions | 15% with visceral pleura involvement | Stroma in 92.5%, glands in 62.5%, CD10+ | 34% received pre-operation hormonal therapy | Not detailed |

| Present Case (2024) | 1 | Shortness of breath worsening with menstruation | Right-sided | Superficial brown lesions on diaphragm | Bullae resected; pulmonary atelectasis | Confirmed (CD10+, ER+, PR+) | Single GnRH agonist 7 yrs prior to CP; no suppression post-op (for fertility) | None |

Similar findings have been reported in a case series published by Marshall et al, in which diaphragmatic implants were observed in 5 out of 8 patients, and diaphragmatic fenestrations were present in 50% of cases [16]. All patients with fenestrations also had diaphragmatic endometrial implants, suggesting that the implants contribute to the development of defects [7]. Furthermore, CP has been reported to occur almost exclusively on the right side, with a prevalence of 100% in a case series by Visouli et al [17] and approximately 90% in other studies [6,18,19]. The preference for the right hemidiaphragm has been attributed to the ‘piston effect’ of the liver, which can create negative pressure that facilitates endometrial migration [16].

Recurrence of CP is a well-documented challenge, with surgical recurrence rates reported to range from 8% to 40% [11]. Pelvic endometriosis often precedes thoracic endometriosis, with studies indicating an interval of up to 5 years before thoracic involvement develops [11]. Our patient had pelvic endometriosis for 10 years and had declined hormonal therapy due to her desire for pregnancy. This prolonged course without hormonal suppression may have contributed to the eventual development of CP, consistent with previous reports showing higher recurrence in patients who did not receive hormonal therapy [20].

Our patient had a long-standing history of pelvic endometriosis, supporting the hypothesis that untreated pelvic disease can eventually progress to thoracic involvement. Clinically, CP is characterized by recurrent pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and cough, which are strongly linked to menstruation [15]. Spontaneous pneumothorax typically occurs 24–72 hours before or after the onset of menstruation [8]. Endometrial implants are predominantly located in the right hemithorax (87.5–100% in documented cases), but left-sided and bilateral cases have also been reported [15]. Additionally, 18.8–51% of CP cases are associated with concurrent pelvic endometriosis [15,20].

The diagnosis of catamenial pneumothorax (CP) is often delayed due to low clinical suspicion. Women of reproductive age presenting with recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax should be evaluated for CP. High-resolution CT scans may reveal pleural or parenchymal nodules, pneumothorax, pleural effusions, cavitation, or bullae, but endometrial implants are more frequently identified during thoracoscopic assessment [5]. Histological confirmation of endometrial glands and stroma occurs in 53–75% of clinically suspected CP cases [8,21,22]. Additional evidence of the inconsistent findings of endometrial tissue in the thorax is provided by a 2016 report, which indicated the absence of histologic confirmation in all clinically diagnosed cases, despite the presence of morphologic features (nodular deposits and diaphragmatic fenestrations) observed during surgical examination [23].

CP management typically involves a combination of surgical intervention and hormonal therapy. VATS is both a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure, enabling direct visualization of the thoracic cavity, lung parenchyma, and diaphragm for characteristic brown/blue endometrial implants or parenchymal blebs. Surgical interventions include bleb resection and mechanical pleurodesis to prevent recurrence [24]. In our case, pleurodesis surgery was performed to reduce the risk of recurrence, with successful postoperative outcomes.

Hormonal therapy plays a crucial role in long-term recurrence prevention. GnRH agonists, oral contraceptives, and progestins are the primary medical options. GnRH agonists induce a hypoestrogenic state, reducing ectopic endometrial activity, whereas oral contraceptives and progestins maintain hormonal suppression [25]. However, the choice of therapy must be tailored to the patient’s reproductive goals. Studies have shown that hormonal therapy following surgery reduces recurrence, yet recurrence rates remain high, reaching up to 32% after 2 years of follow-up [8]. This case is unique because, due to her desire for pregnancy, the patient did not receive hormonal contraception for endometriosis. However, despite this, her CP progression was delayed for 10 years following a single administration of a GnRH agonist. This is a possible alternative approach for women prioritizing fertility while managing CP.

It is recommended to implement multimodal management and administer gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analog therapy for 6–12 months [25]. GnRH analogs cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and amenorrhea to achieve ovarian rest and decrease ectopic endometrial activity [7,8,10,26]. Alifano et al emphasised the necessity of inducing amenorrhea promptly after surgery, as the formation of effective pleural adhesions takes time, and cyclic hormonal fluctuations prior to achieving successful pleurodesis can lead to recurrence [8].

Although significant progress has been made in CP management, infertility remains a challenge for affected women because hormonal therapy, which is typically required to prevent recurrence, can postpone pregnancy attempts. Studies have reported successful IVF outcomes in CP patients receiving GnRH antagonist protocols [11]. However, the impact of ovarian stimulation on CP recurrence remains unclear, as evidence on whether ovulation induction increases CP risk is still inconclusive [29]. Our patient had undergone GnRH agonist treatment for intrauterine insemination (IUI), yet CP progression was significantly delayed, suggesting that short-term hormonal suppression can provide temporary CP control without compromising fertility [27]. During surgery, there were no difficulties removing the endometriosis implant within a diaphragm. A postoperative follow-up chest X-ray showed a satisfactory result, with no evidence of recurrent catamenial pneumothorax.

Future research should focus on comparing different hormonal therapy protocols, including GnRH agonists, GnRH antagonists, and progestins, to determine the most effective approach for managing CP in infertile patients. Additionally, studies should assess the impact of ovarian stimulation on CP recurrence rates to identify safer fertility treatment strategies. Furthermore, the development of surgical techniques specifically tailored for reproductive-aged women is essential to optimize CP treatment while preserving fertility.

Conclusions

In the management of catamenial pneumothorax, clinicians should use a comprehensive approach that incorporates both surgical intervention and tailored hormonal therapy. In patients with diaphragmatic involvement, addressing structural abnormalities through surgical repair can enhance the effectiveness of pleurodesis and reduce recurrence risks. Administering a short course (under 6 months) of a GnRH agonist is recommended for preoperative patients not undergoing surgery during their menstrual cycle, as well as for early postoperative patients, to improve pleurodesis success. In this case, the use of a GnRH agonist contributed to delaying CP progression for 10 years without the need for continuous hormonal suppression. Surgical removal of the endometriosis implant from the diaphragm was successfully performed without complications, and postoperative imaging confirmed the absence of recurrence. These findings suggest that short-term GnRH agonist therapy can be a fertility-preserving alternative for CP management in women prioritizing pregnancy. Further research is needed to determine the optimal duration and timing of GnRH agonist therapy, assess its long-term impact on fertility outcomes, and evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different hormonal and surgical strategies for CP management in infertile women.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the nurses and midwives at Margono Hospital their support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Patient Consent: The patient received a comprehensive explanation regarding the case’s particulars and the images to be included in the case report, and she provided written informed consent for publication.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity: All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

Financial support: None declared

References

- 1.Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Obst Gynecol Rep. 2017;6(1):34–41. doi: 10.1007/s13669-017-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):511–19. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cano-Herrera G, Salmun Nehmad S, Ruiz de Chávez Gascón J, et al. Endometriosis: A comprehensive analysis of the pathophysiology, treatment, and nutritional aspects, and its repercussions on the quality of life of patients. Biomedicines. 2024;12(7):1476. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12071476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aljehani Y. Catamenial pneumothorax. Is it time to approach differently? Saudi Med J. 2014;35(2):115–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azizad-Pinto P, Clarke D. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: Case report and review of the literature. Perm J. 2014;18(3):61–65. doi: 10.7812/TPP/13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alifano M, Roth T, Broët SC, Schussler O, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: A prospective study. Chest. 2003;124(3):1004–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagan P, Barthes FLP, Assouad J, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: Retrospective study of surgical treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(2):378–81. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alifano M, Jablonski C, Kadiri H, et al. Catamenial and noncatamenial, endometriosis-related or nonendometriosis-related pneumothorax referred for surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(10):1048–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-587OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mecha E, Makunja R, Maoga JB, et al. The importance of stromal endometriosis in thoracic endometriosis. Cells. 2021;10(1):180. doi: 10.3390/cells10010180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciriaco P, Muriana P, Carretta A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax as the first expression of thoracic endometriosis syndrome and pelvic endometriosis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(5):1200. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marjański T, Sowa K, Czapla A, Rzyman W. Catamenial pneumothorax – a review of the literature. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2016;13(2):117–21. doi: 10.5114/kitp.2016.61044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022(2):hoac009. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solanki KK, Shook M, Yorke J, Vanlandingham A. A rare case of catamenial pneumothorax and a review of the current literature. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42006. doi: 10.7759/cureus.42006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Härkki P, Jokinen JJ, Salo JA, Sihvo E. Menstruation-related spontaneous pneumothorax and diaphragmatic endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(9):1192–96. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.493194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visouli AN, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(Suppl 4):S448–60. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall MB, Ahmed Z, Kucharczuk JC, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: Optimal hormonal and surgical management. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27(4):662–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visouli AN, Darwiche K, Mpakas A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: A rare entity? Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(Suppl 1):17–31. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.s006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph J, Sahn SA. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: New observations from an analysis of 110 cases. Am J Med. 1996;100(2):164–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)89454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoenfeld A, Ziv E, Zeelel Y, Ovadia J. Catamenial pneumothorax – a literature review and report of an unusual case. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1986;41(1):20–24. doi: 10.1097/00006254-198601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korom S, Canyurt H, Missbach A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax revisited: Clinical approach and systematic review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128(4):502–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legras A, Mansuet-Lupo A, Rousset-Jablonski C, et al. Pneumothorax in women of child-bearing age: An update classification based on clinical and pathologic findings. Chest. 2014;145(2):354–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousset-Jablonski C, Alifano M, Plu-Bureau G, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax and endometriosis-related pneumothorax: Clinical features and risk factors. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(9):2322–29. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta CK, Stanifer BP, Fore-Kosterski S, et al. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax in menstruating women has high recurrence. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(4):1125–30. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bricelj K, Srpčič M, Ražem A, Snoj Ž. Catamenial pneumothorax since introduction of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: A systematic review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2017;129(19–20):717–26. doi: 10.1007/s00508-017-1237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown J, Pan A, Hart RJ. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(12):CD008475. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008475.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alifano M. Catamenial pneumothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16(4):381–86. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32833a9fc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Somigliana E, Viganò P, Benaglia L, et al. Ovarian stimulation and endometriosis progression or recurrence: A systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;38(2):185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]