Abstract

Reward-seeking behavior is essential for survival and is greatly influenced by experience, internal states, and physiological factors such as sleep. The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is reward processing hub that integrates external and internal signals to regulate reward-seeking behaviors. However, it is not well understood how NAc activities during reward seeking may be shaped by learning experience, and to what extent that it may be subject to physiological regulations such as sleep. Here, we used in vivo fiber photometry to monitor calcium (Ca2+) activities in the NAc of male and female mice undergoing sucrose self-administration (SA) training. We found that the NAc Ca2+ dynamics during sucrose SA were related to the behavioral outcome and evolved over different training stages. Moreover, acute sleep deprivation increased sucrose SA while reduced NAc Ca2+ responses and dampened its sensitivity to reward update. Thus, our findings suggest that the NAc response during natural reward seeking is dynamic, adaptive to learning experience, and can be blunted by acute sleep deprivation.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Learning and memory

Introduction

Reward seeking is essential to our survival, and reward seeking behaviors are highly adaptive. A multitude of factors regulate reward-seeking behaviors, including internal state, experience and memory, environmental cues, circadian rhythm, and sleep etc. [1, 2]. How these factors regulate the brain reward circuitry is key to our understanding of the adaptive nature of reward seeking.

The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is an interface between limbic and motor regions, in which emotional and motivational signals are integrated to facilitate motor activities [3–5]. The NAc plays an essential role in reward evaluation and processing [6–9]. In support of this, in vivo studies have revealed NAc activity dynamics in humans and animals during reward anticipation, evaluation, and/or responding [10–23]. Moreover, certain aspects of the NAc responses are dependent on reward-associated learning process [24, 25], reflecting an adaptive nature. However, it is not known how stable these reward-associated NAc responses are after initial formation, and how they may be subject to physiological regulations such as sleep.

Sleep disruptions impact reward seeking in both humans and animals [26, 27]. The underlying neural mechanisms are not well understood, though the NAc is thought to be involved. Following acute sleep deprivation (SD), human imaging studies have demonstrated greater NAc responses to reward-associated cues and/or reward deliveries, including food reward and cues [28, 29], monetary gains and risk-related decision-making [30–32]. To better understand how NAc activities may be regulated by sleep and corresponding changes in reward-seeking behaviors, we used a mouse sucrose self-administration model, and applied in vivo fiber photometry to examine real-time NAc activity dynamics during sucrose reward seeking – first through different learning stages, then tested the impact of acute SD.

Methods

Animals

Male and female C57BL/6 J mice (Jackson Laboratory, stock #000664), 9–15 weeks old, were randomly chosen for all experiments. Mice were maintained at room temperature (22 ± 1 °C), controlled humidity (60 ± 5%), and on a 12:12 light/dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 AM (zeitgeber time, ZT 0). Mice were singly housed once they started behavioral training. All mice had free access to food and water. Mouse usage was in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Pittsburgh (#24024571).

Surgery

Viral and optic fiber surgery was conducted around postnatal day (PD) 49–63. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, IP) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, IP) and placed on a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments). A 34-gauge injection needle connected to a Hamilton syringe driven by a microinfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus) was used to unilaterally inject 0.3–0.5 μl/site (0.1 μl/min) of the calcium indicator jRCaMP1b [33] (Addgene viral prep # 100851-AAV9) into the NAc shell (AP + 1.5, ML ± 0.70, DV −5.00). Subsequently, optic fibers (200-μm core) with flat tips were unilaterally implanted above the NAc (AP + 1.35, ML ± 0.70, DV −4.30). All mice were singly housed after surgery. Mice began behavioral training approximately 2 weeks after surgery.

Sucrose self-administration (SA) training

All SA training was conducted in operant-conditioning chambers (Med Associates). Active-lever pressing resulted in the delivery of a single sucrose pellet (20 mg; Bio-Serv, catalog #F05301, chocolate flavored). Inactive lever pressing had no consequences but was counted. Mice underwent overnight training at fixed-ratio (FR) 3 without a fiber optic cable attached for 2 nights, then with an optic fiber cable attached for 1 one night, followed by daily 30 min training at FR1 for ~2 weeks before sleep manipulations. The mice continued with daily training after sleep manipulations till ~ 5 weeks when they completed reversal SA training. All tests were performed under FR1. A single ALP resulted in a 20-sec timeout during which both levers were withdrawn. One pellet was delivered 2 s after each ALP. The mice had ad libitum access to water but not standard chow during overnight training. Daily sucrose SA training was conducted at approximately ZT6. This time was chosen to match the testing time after sleep deprivation procedure (see below).

In vivo fiber photometry

The mice were adapted to handling for 2–3 days prior to attachment to low-autofluorescence patch cords (Doric Lensens). The patch cords were photobleached for ~1 hr prior to recordings per Doric Lenses recommendation to ensure less than ~15% photobleaching during 30 min recordings. JRCaMP1b recordings started at approximately ZT6 during sucrose SA. JRCaMP1b signal in the NAc was obtained by using 560 nm light to monitor Ca2+ responses and 405 nm light (LEDs, Doric Lenses) as isosbestic control signal minimally dependent on Ca2+ activity [33, 34]. Light intensities were ~20–30 μW at the end of the patch cord and kept consistent throughout the recordings. Light was delivered into the NAc via a 200 μm 0.57 N.A. optical fiber (RWD Life Science) fitted with 1.25 mm bronze sleeve (Doric Lenses) for attachment to the optic fiber implant. A rotary joint (Prizmatix) was attached at the top of the optical fiber to maintain optimal light transmission as the mice were freely moving. JRCaMP (F560) and isosbestic signals (F405) were collected by the same optical fiber and passed through a fluorescence mini cube for filtering (FMC6_IE(400-410)_E1(460-490)_F1(500-540)_E2(555-570)_F2(580-680)_S, Doric Lenses). The signals were then focused onto a femtowatt photoreceiver (Model 2151, Newport), amplified, and A-D converted using the RZ5P processor (Tucker David Technologies). Active lever presses (ALP) and inactive lever presses (ILP) were TTL time-stamped in Synapse (Tucker David Technologies).

Fiber photometry data analysis

Raw photometry data (F405, F560) were analyzed blind to treatment conditions using MATLAB R2022a custom-written scripts. Detrending and normalization of each ALP and ILP was calculated by dF = F560 / Median560 – F405 / Median405. dF data was downsampled to 250 Hz and cut to 30 s segments with the midpoint (t = 0) aligned to the onset of ALP TTL time stamps. dF data for each individual 30-sec segment was Z-scored using individual baselines at ~ −15 to −10 s prior to the corresponding ALP. The Z-scored data was averaged per training session per animal and used for group analyses for area-under-the-curve (AUC) and kinetics.

Sleep deprivation

After obtaining a daily performance baseline, mice underwent regular sleep or SD for 4 h ~(ZT2–6). Mice had ad libitum access to food and water throughout the entirety of the SD procedure. Mice were sleep deprived through the gentle-handling method [35]. Briefly, mice were kept awake by introducing novel objects, nesting material, gentle tapping and/or moving the cage, a 1-time bedding change ~ ZT 3, and occasionally, gentle brushing of the tail and vibrissae with a soft brush. This method used in our hands introduces minimal stress to the mice as measured by plasma corticosterone levels [36]. Mice were given 3 days to 1 week to recover between tests.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with overdosed isoflurane, and then perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PB. Brains were removed and given an additional overnight postfix in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C, and then transferred to 30% sucrose in PB for 48 h before sectioning. Coronal sections (35–40 μm) were cut on a cryostat (Leica CM1950) and were collected for imaging. Endogenous fluorescence was captured by the Olympus SLIDEVIEW VS200 slide scanner, and the virus injection sites and levels of expressions were determined based on the images.

Statistics

Group sizes were determined based on power analyses using preliminary estimates of variance by achieving 80% power to observe differences at α = 0.05. Normal distribution was assumed for all data. Behavioral and fiber photometry data were analyzed in GraphPad Prism 9. One-way or two-way ANOVA (including mixed-effects analysis) was conducted followed by post-hoc tests. In all graphs, means were reported as mean ± SEM and p values were from main effects or interactions *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and post-hoc tests #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001.

Results

NAc Ca2+ activity during sucrose reward seeking is related to behavioral outcome and sensitive to training stages

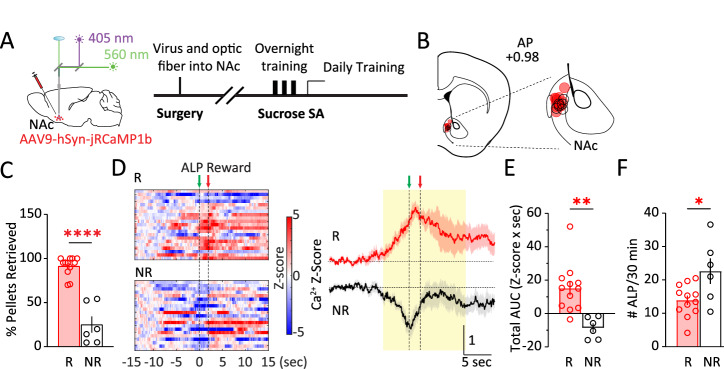

Male and female mice received unilateral intra-NAc injection of AAV expressing a genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor jRCaMP1b [33] and fiber optic implantation, and were trained to press an active lever to obtain sucrose pellet reward (Fig. 1A, B; Methods). After overnight trainings, most mice (12 out of 18) performed ALP and regularly retrieved the sucrose pellets (% Pellets retrieved: 91.4 ± 3.1%; Retrievers) during subsequent tests, whereas some (6 out of 18) learned to ALP but consistently retrieved less (% Pellets retrieved: 25.1 ± 9.2%; Non-retrievers; t16 = 8.572, p < 0.0001; t-test; Fig. 1C), even though the pellets were freely accessible. NAc population Ca2+ activities were monitored via in vivo fiber photometry and aligned to active lever-press (ALP). Whereas the Retrievers typically showed an overall increase in NAc population Ca2+ activities surrounding ALP and reward delivery, the Non-retrievers showed an overall decrease in NAc Ca2+ responses (total AUC −5 to 10 s, t16 = 3.795, p < 0.01; Fig. 1D, E), with a contrasting higher #ALP (t16 = 2.665, p < 0.05; Fig. 1F). Thus, the NAc Ca2+ dynamics were divergently associated with subsequent behaviors. Furthermore, the Retrievers were able to maintain a stable self-administration (SA) performance and continued with the remainder of the experiments, whereas the initial Non-retrievers gradually stopped lever-pressing for sucrose in subsequent training days and thus were not included for further experimentation. Together, these results suggest that the NAc Ca2+ response during reward seeking is related to the reinforcing behavioral outcome.

Fig. 1. NAc Ca2+ activity during sucrose reward seeking is related to behavioral outcome.

A Surgery, fiber photometry configuration, and experimental timeline. B Diagram of a coronal section containing the NAc, showing the positions of fiber optic tips in Retrievers (red) and Non-retrievers (black). C % Pellets retrieved in the two groups of mice: Retrievers (R) and Non-retrievers (NR). D Left, Representative heat maps of NAc Ca2+ Z-scores from a Retriever (R) versus a Non-retriever (NR) mouse during SA training over 30 min. Each row represented an individual trial with ALP aligned at t = 0 s. Right, Group-averaged Z-scores of NAc Ca2+ activity from Retriever mice versus Non-retriever mice, shown as Mean +/− SEM from all mice in each group. Yellow shades, periods used for AUC calculations. Green arrow, time of ALP; red arrow, time of sucrose pellet reward delivery. E The Retrievers had greater total Ca2+ activity than the Non-retrievers, calculated as AUC from −5 s till 10 s. F The Non-retrievers had greater #ALP than the Retrievers during the test as in D, E. ALP active-lever press, AUC area-under-curve, NAc nucleus accumbens, NR non-retriever, R retriever, SA self-administration. Data were represented as mean ± SEM. Each circle represents a mouse. n = 6 – 12 mice in each group. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001.

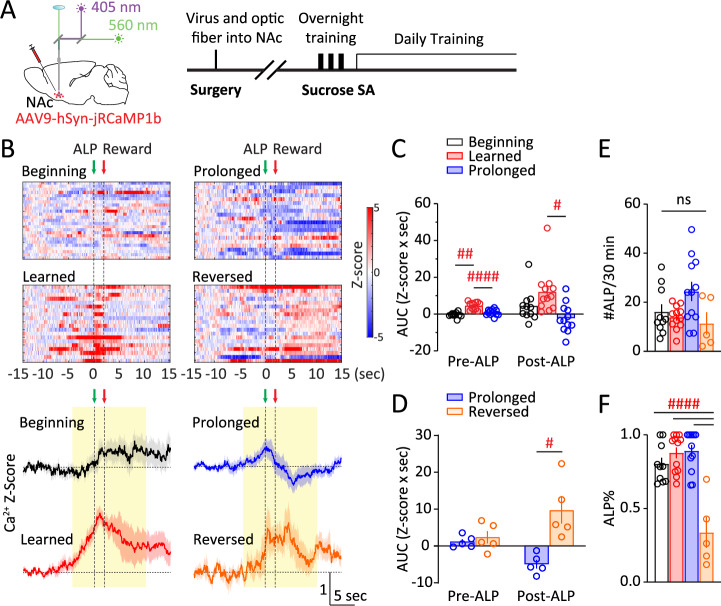

Over the following period of ~5 weeks (Fig. 2A), the NAc Ca2+ responses kept evolving, which were compared and contrasted under four stages (Fig. 2B): i) When mice first acquired sucrose SA (defined as #ALP/#total lever press >2/3), which typically occurred upon finishing the overnight training; ii) when #ALP stabilized over daily training, typically one week after stage i; iii) about 3–4 weeks following stage ii with stable behavioral performances; iv) in a subset of mice, the active-lever and inactive-lever were subsequently reversed. Dividing the NAc Ca2+ responses into two phases, pre-ALP (−5–0 s) and post-ALP (0–10 s), we found that acquisition of sucrose SA increased the pre-ALP Ca2+ responses (stage x phase: F(1.807, 14.45) = 4.799, p < 0.05; stage i versus ii, p < 0.01; 2-way RM ANOVA with Tukey’s test), whereas prolonged training reduced both pre-ALP and post-ALP Ca2+ response (stage ii versus iii, pre-ALP: p < 0.0001; post-ALP: p < 0.05; 2-way RM ANOVA with Tukey’s test; Fig. 2B, C). The reduction in stage iii NAc Ca2+ responses was not because of a loss of jRCaMP1b expression or function – as we tested in a subset of mice, reversal of the active- versus inactive-levers during subsequent SA training revealed prominent Ca2+ activities post-ALP when the mouse pressed the newly assigned active-lever (F(1, 4) = 17.52, p < 0.05; post-ALP in stage iii versus iv, p < 0.05; 2-way RM ANOVA with Šídák’s test; Fig. 2B, D, S1A). At the behavioral level, there was no overall difference in #ALP or ALP% across training stages, except for ALP% in reversal learning (#ALP: F(3, 35) = 3.130, p < 0.05 but no significant multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, Fig. 2E; ALP%: F(3, 35) = 19.27, p < 0.0001; reversal training compared to onset, learned, and prolonged training, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, Fig. 2F), suggesting that the changes in NAc Ca2+ responses were not because of overall ALP performance differences across the training stages. Together, these results suggest that the NAc is engaged upon initial reward learning as well as during reversal learning, but less activated after prolonged training even if the performance of reward seeking is at similar levels. Moreover, the NAc is engaged from before the reward-seeking action till after reward delivery, and both phases of the NAc responses are dampened after prolonged training. We thus focused on mice during the stable responding stage ii for sleep manipulation experiments.

Fig. 2. NAc Ca2+ activity during sucrose reward seeking is sensitive to training stages.

A Surgery, fiber photometry configuration, and experimental timeline. B Top, Representative heat maps of NAc Ca2+ Z-scores from a mouse through the four stages. Each row represented an individual trial with ALP aligned at t = 0 s. Bottom, Averaged NAc Ca2+ Z-scores in all the mice across sucrose SA training stages, shown as Mean +/− SEM. Yellow shades, periods used for AUC calculations. Green arrow, time of ALP; red arrow, time of sucrose pellet reward delivery. C AUC of NAc Ca2+ Z-score integrated at pre-ALP (−5–0 s) or post-ALP (0–10 s) across stages i to iii. D AUC of NAc Ca2+ Z-score integrated at pre-ALP (−5–0 s) or post-ALP (0–10 s) across stages iii to iv. E No changes in #ALP across training stages. F No changes in ALP% at stages i to iii, and a decrease during stage iv. Data were represented as mean ± SEM. Each circle represents a mouse. n = 10 – 12 mice for stages i to iii, and n = 5 for stage iv. ALP active-lever press, AUC area-under-curve, NAc nucleus accumbens, SA self-administration. Post-hoc test # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, #### p < 0.0001; ns = not significant.

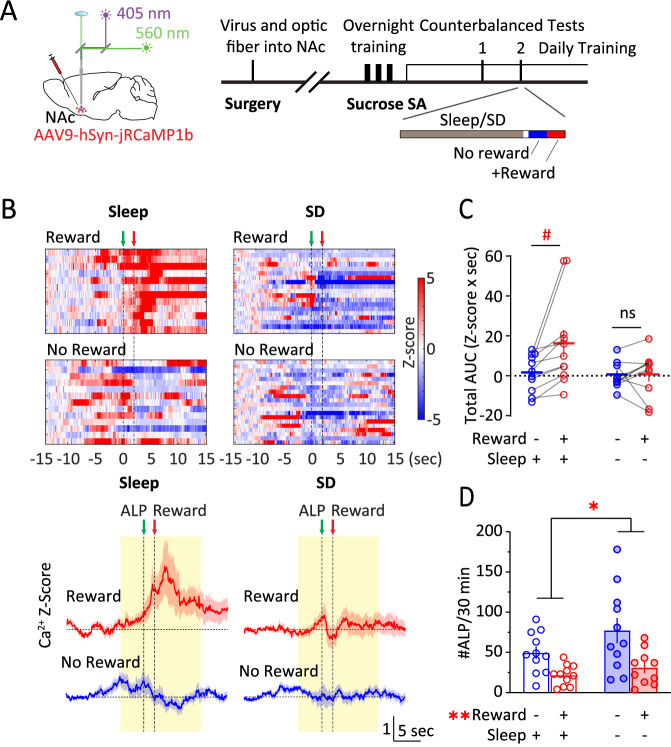

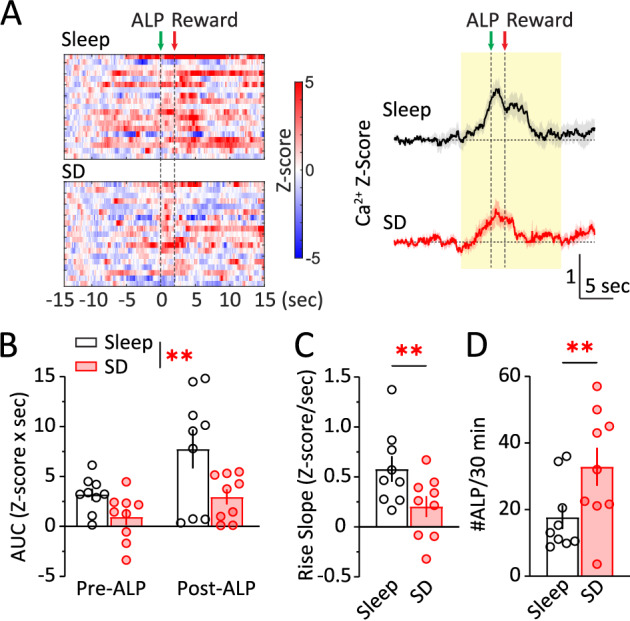

Acute sleep deprivation reduces NAc Ca2+ activity during sucrose reward seeking

A single episode of acute sleep deprivation (SD) directly impacts reward seeking in both animals and humans [28, 29, 36–55] and impairs NAc synaptic transmission [36, 54]. How may acute SD alter NAc activities during reward seeking? We measured NAc Ca2+ dynamics during sucrose SA following acute SD (Fig. 3A). Compared to normal sleep days, NAc Ca2+ responses were decreased following acute SD (SD x phase: F (1, 8) = 0.966, p = 0.355; main effect of SD, p < 0.01, RM 2-way ANOVA; Fig. 3B). Moreover, the rise slope of NAc Ca2+ at −2 – 0 s before ALP was reduced after SD (t8 = 2.975, p < 0.01; paired t-test; Fig. 3C). The decrease in NAc Ca2+ was accompanied by an increase in #ALP for sucrose following SD (t8 = 3.179, p < 0.01; paired t-test; Fig. 3D), and an increase in pellet consumption (t8 = 2.864, p < 0.05; paired t-test), consistent with previous reports that acute SD increases sucrose reward seeking in male mice [36, 54]. Together, these results suggest that acute SD reduces NAc activities while increasing sucrose reward seeking.

Fig. 3. Acute sleep deprivation reduces NAc Ca2+ activity during sucrose reward seeking.

A Left, Representative heat maps of NAc Ca2+ Z-scores from a mouse performing sucrose SA following normal sleep or acute SD. Each row represented an individual trial with ALP aligned at t = 0 s. Right, Averaged NAc Ca2+ Z-scores from all the mice during sucrose SA following normal sleep or acute SD, shown as Mean +/− SEM. Yellow shades, periods used for AUC calculations. Green arrow, time of ALP; red arrow, time of sucrose pellet reward delivery. B AUC of NAc Ca2+ Z-score integrated at pre-ALP (−5–0 s) or post-ALP (0–10 s) following normal sleep or acute SD. C SD reduced the rise slope of NAc Ca2+ responses (−2–0 s). D SD increased #ALP per 30 min. ALP active lever press, AUC area-under-curve, SD sleep deprivation. Data were represented as mean ± SEM. Each circle represents a mouse. n = 9 mice. **p < 0.01.

Acute SD dampens NAc Ca2+ responses to reward update

How may NAc activities adapt to changes in reward availability? We used a two-step design for the following sucrose SA test (Fig. 4A). During step-I, a 30-min test, ALP did not result in sucrose pellet delivery. Then, step-II followed for another 30 min, during which ALP resulted in sucrose pellet delivery as usual. Under normal sleep, NAc Ca2+ response was minimum during step-I when sucrose reward was not available, and was largely revealed during step-II; however, after acute SD, this response update based on reward availability was diminished (sleep x reward: F (1, 9) = 5.591, p < 0.05, 2-way RM ANOVA; Fig. 4B, C). The behaviors showed an increase in #ALP following SD (SD x reward: F(1, 9) = 2.375, p = 0.158, main effect of SD, p < 0.05, main effect of reward, p < 0.01; RM 2-way ANOVA; Fig. 4D). Together, these results suggest that the NAc Ca2+ activities are sensitive to reward update, which is impaired by acute SD.

Fig. 4. Acute sleep deprivation reduces NAc Ca2+ responses to reward update.

A Surgery, fiber photometry configuration, and experimental timeline. On the testing day, following normal sleep or acute sleep deprivation, mice were tested for SA without sucrose pellet delivery for ~30 min followed by regular SA with pellet delivery for another ~30 min. B Top, Representative heat maps of NAc Ca2+ Z-scores in an example mouse across the four conditions. Each row represented an individual trial with ALP aligned at t = 0 s. Bottom, Averaged NAc Ca2+ Z-scores from all the mice during SA following normal sleep or acute sleep deprivation, in the absence or presence of sucrose pellet delivery. Yellow shades, periods used for AUC calculations. Green arrow, time of ALP; red arrow, time of sucrose pellet reward delivery. C Total AUC of NAc Ca2+ Z-score (−5–10 s) following normal sleep or sleep deprivation, and in the absence or presence of sucrose pellet deliveries. D #ALP under normal sleep or sleep deprivation in the absence or presence of sucrose pellet delivery. ALP active lever press, AUC area-under-curve, NAc nucleus accumbens, SA self-administration, SD sleep deprivation. Data were represented as mean ± SEM. Each circle represents a mouse. n = 10–11 mice in each condition. Main effect * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, post-hoc test # p < 0.05.

Discussion

The NAc serves as a limbic-motor interphase that mediates reward evaluation and processing [3–5]. Here, we show that the NAc Ca2+ dynamics during reward seeking are related to behavioral outcome and evolve through training stages. Moreover, acute SD reduces overall NAc responsiveness during reward seeking and dampens NAc sensitivity to reward update.

Reward seeking-associated NAc Ca2+ dynamics evolves along the course of behavioral training. As the mice acquired sucrose SA, the NAc Ca2+ activities started to increase especially before ALP (Fig. 2B, C). The increase in Ca2+ and its timing are both consistent with a recent study using Ca2+ imaging in a similar reward-seeking model in mice [56]. Over extended training, however, NAc Ca2+ activities were diminished, both before and after ALP (Fig. 2B, C), even though #ALP remained high (Fig. 2E). This suggests that the NAc is less engaged once reward-seeking behavior is proficient. Considering that fiber photometry depicts population activities, it could either be that NAc processing becomes exceedingly efficient, requiring reduced number of neurons and less overall activities to achieve similar behavioral outcomes; or that NAc processing may be largely by-passed by other regulatory circuits, for example, those that mediate habitual behaviors [57]. Indeed, at stage iv, most mice (4 out of 5) perseveringly pressed the inactive lever more than the active lever (ALP% <45%) long after the two levers were reversed – for as long as we tested, up to 7 days. This suggests that as the behavior transitions to presumed habitual, NAc activities could be less involved. Either scenario could account for the immediate increase in NAc Ca2+ activities when the active and inactive levers were reversed (Fig. 2B, D), which likely reengages NAc to evaluate the reward associated with the newly assigned active lever.

The NAc Ca2+ dynamics can be roughly divided into pre- and post-lever press responses. Whereas the post-lever press responses reflect reward delivery (Fig. 4B, S1A), how may pre-lever press responses be interpreted? It is unlikely that the NAc pre-lever press Ca2+ reflects motor activities, based on the following: 1) during initial training, the Non-retrievers pressed the active lever more than the Retrievers, yet their pre-ALP Ca2+ was low; 2) similarly, in stage iii training, pre-ALP Ca2+ was reduced compared to stage ii (Fig. 2C), even though #ALP remained robust (Fig. 2E); 3) under no-reward testing phase following sleep deprivation, pre-ALP Ca2+ was low (Fig. 4Bright) despite augmented #ALP (Fig. 4D). Together, these results argue against the association of pre-ALP Ca2+ with the motor activities for lever press. On the other hand, our results are consistent with the notion that the pre-ALP activities reflect anticipation of reward that precedes self-initiated reward seeking [56, 58]. This component was increased from the beginning stage i to the learned stage ii (Fig. 2B, C), consistent with the presumed augmentation of reward anticipation as the training progressed. The pre-ALP Ca2+ may be also associated with the internal evaluation of the anticipated reward, as it is higher in the Retriever mice during the initial training than in Non-retrievers (Fig. 1D). Moreover, after prolonged training in stage iii the pre-ALP Ca2+ was decreased compared to stage ii (Fig. 2C), which could be consistent with a decrease in the salience of the anticipated reward. Subsequent reversal of levers in stage iv did not increase the pre-ALP Ca2+(Fig. 2D), as the anticipation of reward to be associated with a new lever pressing was yet to be established. On the other hand, stage iv pre-ILP Ca2+ was larger than stage i pre-ALP Ca2+, even though the motor aspects were similar (Fig. S1A, B). This may be accounted for by the better-established anticipation of reward in stage iv than in stage i, even if it was a false expectation as the levers were swapped. Together, the NAc pre-ALP Ca2+ may reflect anticipation of reward, rather than merely the motor activities leading to lever press.

Our current study does not differentiate between NAc principal neurons that predominantly express D1 type dopamine receptors (D1 neurons) versus those that express D2 dopamine receptors (D2 neurons) [59]. Using D1-Cre and D2-Cre mice, a recent study monitored NAc D1 and D2 neuron Ca2+ activities during self-initiated reward seeking [56]. It was shown that D1 and D2 neuron Ca2+ activities rise prior to lever pressing for sucrose, and moves into synchrony following initial learning, both are consistent with our observations (Fig. 2B). It was also shown that D1 neuron activities typically precede D2 neuron activities before lever pressing [56]. Regarding the changes in NAc dynamics following training, another study by Deseyve et al. measured D1 and D2 neuron responses during a Pavlovian learning paradigm in mice, and showed that both D1 and D2 neurons reduced Ca2+ responses to reward-associated cues at late training [13]. It remains to be determined for self-initiated reward seeking, whether the training-induced decrease in NAc Ca2+ responses involves both D1 and D2 neuron response changes.

Following acute SD, #ALP for sucrose was increased (Fig. 3D), whereas NAc Ca2+ responses were decreased (Fig. 3A–C). This is consistent with our previous reports that acute SD increases sucrose SA in mice [36, 54], and that the overall NAc activity measured by c-Fos expression is inversely correlated with #ALP for sucrose reward seeking (study under review). A tentative interpretation is that the NAc activities reflect the level of arousal, consistent with the accumulating evidence that NAc diverse cell types and projections regulate sleep and wakefulness [60–65], which is intimately associated with reward seeking. Thus, reduced arousal – such as that following SD – may bias toward habitual behaviors. Similarly, during prolonged SA training (Fig. 2B, C), arousal may also be suboptimal. By contrast, during stage iv reversal training which likely involves heightened arousal, NAc Ca2+ response was elevated (Fig. 2B, D). Nonetheless, following normal sleep under no-reward condition, NAc Ca2+ response was minimal, even though the mice appeared to be highly aroused – #ALP was higher than under reward condition (Fig. 4D). Thus, NAc Ca2+ response may be intersectionally associated with arousal and reward, requiring both for full activation. Along this reasoning, high arousal combined with reward may fully engage NAc activities for adaptive learning and decision-making processes [24, 66, 67], which may be compromised under SD.

Regarding the cellular mechanisms underlying SD-induced dampening of NAc responses, one possibility is that SD reduces the excitatory synaptic inputs onto NAc neurons. For example, both prefrontal cortical and rostral amygdala glutamatergic inputs to NAc shell principal neurons show reduced glutamate release [36, 54], and the overall excitatory/inhibitory balance in synaptic transmission onto these neurons is shifted toward inhibition following acute SD [36, 54]. Likewise, a human imaging study demonstrated that poor sleep decreased the coupling between the dorsal lateral PFC and NAc during reward processing suggesting altered top-down regulation [68]. Thus, reduced excitatory drives may decrease NAc activities during reward seeking. At the behavioral level, this may render the NAc less responsive to reward, which in turn, precipitates habitual behaviors. Our results are in contrast to human imaging studies which predominantly document an SD-induced increase in NAc response to reward or reward-associated cues, which accompanies increased motivation for reward [28–32, 53]. There are a few potential differences, including that, i) we monitored self-initiated reward seeking rather than cue-elicited reward seeking; ii) we used well-trained mice that took the task as a daily routine rather than associating the task with a highly salient reward such as money – often used in human studies; and iii) our mice had free access to food during SD, whereas human studies on food reward typically require a fasting period before the test [28, 29, 53]. Thus, there could be distinct neural mechanisms that contribute to SD-induced increase in natural reward seeking under different circumstances.

SD not only reduced NAc Ca2+ activities during learned reward-seeking behavior (Fig. 3), but also blunted its response to changes in reward availability (Fig. 4B, C). This is consistent with the notion that SD promotes habitual over goal-directed reward-seeking behaviors [69], and impairs behavioral flexibility specifically through “feedback blunting” [70]. The underlying neural mechanisms are not clear, though possibly related to the decreased functional coupling between the PFC and subcortical regions, in the context of reducing top-down dynamic attentional controls [70].

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Joseph Widjaja and Lydia Liszewski for support in data analysis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: YHH, ALA, Methodology: ALA, LC, Investigation: ALA, LC, TRB, Supervision: YHH, Writing: ALA, YHH.

Funding

The reported work was supported by NIH funds DA046491 (YH), DA046346 (YH, YD), and DA057954 (YH).

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

Code availability

All MATLAB scripts were based on version R2022a and are available upon request.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal usage was in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Pittsburgh (#24024571). This is an animal study only, and informed consent to participate is not applicable. All authors have given their consent for the publication of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-025-03442-z.

References

- 1.Balleine BW. Neural bases of food-seeking: affect, arousal and reward in corticostriatolimbic circuits. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:717–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Northeast RC, Vyazovskiy VV, Bechtold DA. Eat, sleep, repeat: the role of the circadian system in balancing sleep-wake control with metabolic need. Curr Opin Physiol. 2020;15:183–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelley AE. Ventral striatal control of appetitive motivation: role in ingestive behavior and reward-related learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27:765–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mogenson GJ, Jones DL, Yim CY. From motivation to action: functional interface between the limbic system and the motor system. Prog Neurobiol. 1980;14:69–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Neurobehavioural mechanisms of reward and motivation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox J, Witten IB. Striatal circuits for reward learning and decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20:482–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, Lin Y, Yu M, Zhou K. The nucleus accumbens in reward and aversion processing: insights and implications. Front Behav Neurosci. 2024;18:1420028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:321–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML. Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron. 2015;86:646–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clithero JA, Reeck C, Carter RM, Smith DV, Huettel SA. Nucleus accumbens mediates relative motivation for rewards in the absence of choice. Front Hum Neurosci. 2011;5:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day JJ, Roitman MF, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Associative learning mediates dynamic shifts in dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1020–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day JJ, Carelli RM. The nucleus accumbens and Pavlovian reward learning. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:148–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deseyve C, Domingues AV, Carvalho TTA, Armada G, Correia R, Vieitas-Gaspar N, et al. Nucleus accumbens neurons dynamically respond to appetitive and aversive associative learning. J Neurochem. 2024;168:312–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francois J, Huxter J, Conway MW, Lowry JP, Tricklebank MD, Gilmour G. Differential contributions of infralimbic prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens during reward-based learning and extinction. J Neurosci. 2014;34:596–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Hairston J, Schrier M, Fan J. Common and distinct networks underlying reward valence and processing stages: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1219–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Doherty JP, Deichmann R, Critchley HD, Dolan RJ. Neural responses during anticipation of a primary taste reward. Neuron. 2002;33:815–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oren S, Tittgemeyer M, Rigoux L, Schlamann M, Schonberg T, Kuzmanovic B. Neural encoding of food and monetary reward delivery. Neuroimage. 2022;257:119335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagnoni G, Zink CF, Montague PR, Berns GS. Activity in human ventral striatum locked to errors of reward prediction. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:97–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stice E, Yokum S, Burger KS, Epstein LH, Small DM. Youth at risk for obesity show greater activation of striatal and somatosensory regions to food. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4360–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taira M, Millard SJ, Verghese A, DiFazio LE, Hoang IB, Jia R, et al. Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core encodes the general excitatory components of learning. J Neurosci. 2024;44:e0120242024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dillen LF, van Steenbergen H. Tuning down the hedonic brain: cognitive load reduces neural responses to high-calorie food pictures in the nucleus accumbens. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2018;18:447–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang KS, Smith DV, Delgado MR. Using fMRI to study reward processing in humans: past, present, and future. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115:1664–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan H, Shlobin NA, Jung Y, Zhang KK, Warsi N, Kulkarni AV, et al. Nucleus accumbens: a systematic review of neural circuitry and clinical studies in healthy and pathological states. J Neurosurg. 2023;138:337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Floresco SB. The nucleus accumbens: an interface between cognition, emotion, and action. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:25–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultz W. Neuronal reward and decision signals: from theories to data. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:853–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavaliotis E, Boardman JM, Clark JW, Ogeil RP, Verdejo-Garcia A, Drummond SPA. The relationship between sleep and appetitive conditioning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023;144:105001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause AJ, Simon EB, Mander BA, Greer SM, Saletin JM, Goldstein-Piekarski AN, et al. The sleep-deprived human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:404–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demos KE, Sweet LH, Hart CN, McCaffery JM, Williams SE, Mailloux KA, et al. The effects of experimental manipulation of sleep duration on neural response to food cues. Sleep. 2017;40:zsx125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St-Onge MP, McReynolds A, Trivedi ZB, Roberts AL, Sy M, Hirsch J. Sleep restriction leads to increased activation of brain regions sensitive to food stimuli. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:818–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullin BC, Phillips ML, Siegle GJ, Buysse DJ, Forbes EE, Franzen PL. Sleep deprivation amplifies striatal activation to monetary reward. Psychol Med. 2013;43:2215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkatraman V, Chuah YM, Huettel SA, Chee MW. Sleep deprivation elevates expectation of gains and attenuates response to losses following risky decisions. Sleep. 2007;30:603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkatraman V, Huettel SA, Chuah LY, Payne JW, Chee MW. Sleep deprivation biases the neural mechanisms underlying economic preferences. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3712–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dana H, Mohar B, Sun Y, Narayan S, Gordus A, Hasseman JP, et al. Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity. Elife. 2016;5:e12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molina RS, Qian Y, Wu J, Shen Y, Campbell RE, Drobizhev M, et al. Understanding the fluorescence change in red genetically encoded calcium ion indicators. Biophys J. 2019;116:1873–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colavito V, Fabene PF, Grassi-Zucconi G, Pifferi F, Lamberty Y, Bentivoglio M, et al. Experimental sleep deprivation as a tool to test memory deficits in rodents. Front Syst Neurosci. 2013;7:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Z, Wang Y, Cai L, Li Y, Chen B, Dong Y, et al. Prefrontal cortex to accumbens projections in sleep regulation of reward. J Neurosci. 2016;36:7897–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atrooz F, Alrousan G, Hassan A, Salim S. Early-life sleep deprivation enhanced alcohol consumption in adolescent rats. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:856120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benedict C, Brooks SJ, O’Daly OG, Almen MS, Morell A, Aberg K, et al. Acute sleep deprivation enhances the brain’s response to hedonic food stimuli: an fMRI study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berro LF, Tufik SB, Frussa-Filho R, Andersen ML, Tufik S. Sleep deprivation precipitates the development of amphetamine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2018;671:29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bjorness TE, Greene RW. Sleep deprivation enhances cocaine conditioned place preference in an orexin receptor-modulated manner. eNeuro. 2020;7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brondel L, Romer MA, Nougues PM, Touyarou P, Davenne D. Acute partial sleep deprivation increases food intake in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1550–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duraccio KM, Zaugg K, Jensen CD. Effects of sleep restriction on food-related inhibitory control and reward in adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019;44:692–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Garcia F, Priego-Fernandez S, Lopez-Mucino LA, Acosta-Hernandez ME, Pena-Escudero C. Increased alcohol consumption in sleep-restricted rats is mediated by delta FosB induction. Alcohol. 2021;93:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greer SM, Goldstein AN, Walker MP. The impact of sleep deprivation on food desire in the human brain. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamidovic A, de Wit H. Sleep deprivation increases cigarette smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martins PJ, Marques MS, Tufik S, D’Almeida V. Orexin activation precedes increased NPY expression, hyperphagia, and metabolic changes in response to sleep deprivation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McNeil J, Forest G, Hintze LJ, Brunet JF, Finlayson G, Blundell JE, et al. The effects of partial sleep restriction and altered sleep timing on appetite and food reward. Appetite. 2017;109:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puhl MD, Boisvert M, Guan Z, Fang J, Grigson PS. A novel model of chronic sleep restriction reveals an increase in the perceived incentive reward value of cocaine in high drug-taking rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;109:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rihm JS, Menz MM, Schultz H, Bruder L, Schilbach L, Schmid SM, et al. Sleep deprivation selectively upregulates an amygdala-hypothalamic circuit involved in food reward. J Neurosci. 2019;39:888–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Satterfield BC, Raikes AC, Killgore WDS. Rested-baseline responsivity of the ventral striatum is associated with caloric and macronutrient intake during one night of sleep deprivation. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Jauch-Chara K, Born J, Schultes B. A single night of sleep deprivation increases ghrelin levels and feelings of hunger in normal-weight healthy men. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:331–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:846–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.St-Onge MP, Wolfe S, Sy M, Shechter A, Hirsch J. Sleep restriction increases the neuronal response to unhealthy food in normal-weight individuals. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38:411–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Liu Z, Cai L, Guo R, Dong Y, Huang YH. A critical role of basolateral amygdala-to-nucleus accumbens projection in sleep regulation of reward seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:954–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang CL, Schnepp J, Tucker RM. Increased hunger, food cravings, food reward, and portion size selection after sleep curtailment in women without obesity. Nutrients. 2019;11:663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schall TA, Li KL, Qi X, Lee BT, Wright WJ, Alpaugh EE, et al. Temporal dynamics of nucleus accumbens neurons in male mice during reward seeking. Nat Commun. 2024;15:9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lipton DM, Gonzales BJ, Citri A. Dorsal striatal circuits for habits, compulsions and addictions. Front Syst Neurosci. 2019;13:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wassum KM, Ostlund SB, Maidment NT. Phasic mesolimbic dopamine signaling precedes and predicts performance of a self-initiated action sequence task. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:846–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baik JH. Dopamine signaling in reward-related behaviors. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan G, Zhao B, Zhang M, Guo Y, Yan Y, Dai D, et al. Nucleus accumbens corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons projecting to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis promote wakefulness and positive affective state. Neurosci Bull. 2024;40:1602–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo YJ, Li YD, Wang L, Yang SR, Yuan XS, Wang J, et al. Nucleus accumbens controls wakefulness by a subpopulation of neurons expressing dopamine D(1) receptors. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roy K, Zhou X, Otani R, Yuan PC, Ioka S, Vogt KE, et al. Optochemical control of slow-wave sleep in the nucleus accumbens of male mice by a photoactivatable allosteric modulator of adenosine A(2A) receptors. Nat Commun. 2024;15:3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Toth BA, Chang KS, Fechtali S, Burgess CR. Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens promotes REM sleep and cataplexy. iScience. 2023;26:107613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oishi Y, Xu Q, Wang L, Zhang BJ, Takahashi K, Takata Y, et al. Slow-wave sleep is controlled by a subset of nucleus accumbens core neurons in mice. Nat Commun. 2017;8:734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eban-Rothschild A, Rothschild G, Giardino WJ, Jones JR, de Lecea L. VTA dopaminergic neurons regulate ethologically relevant sleep-wake behaviors. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1356–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eijsker N, van Wingen G, Smolders R, Smit DJA, Denys D. Exploring the role of the nucleus accumbens in adaptive behavior using concurrent intracranial and extracranial electrophysiological recordings in humans. eNeuro. 2020;7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Basar K, Sesia T, Groenewegen H, Steinbusch HW, Visser-Vandewalle V, Temel Y. Nucleus accumbens and impulsivity. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:533–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Galvan A. The effects of poor quality sleep on brain function and risk taking in adolescence. Neuroimage. 2013;71:275–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen J, Liang J, Lin X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Lu L, et al. Sleep deprivation promotes habitual control over goal-directed control: behavioral and neuroimaging evidence. J Neurosci. 2017;37:11979–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Honn KA, Hinson JM, Whitney P, Van Dongen HPA. Cognitive flexibility: A distinct element of performance impairment due to sleep deprivation. Accid Anal Prev. 2019;126:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

All MATLAB scripts were based on version R2022a and are available upon request.