Abstract

Intestinal stem cell (ISC) aging diminishes the regenerative capacity of the intestinal epithelia, but effective therapeutic strategies to counteract human ISC aging remain elusive. Here, we find that the synthesis of α-lipoic acid (ALA) is reduced in old human small intestine. Notably, ALA supplementation inhibits ISC aging and decreases the number of atypical Paneth cells in old human intestinal organoids and in old mouse small intestines. Importantly, we discern that the effect of ALA on mitigating ISC aging is contingent upon the presence of Paneth cells. Inhibiting the mTOR pathway in Paneth cells with ALA or rapamycin significantly increases cyclic ADP ribose (cADPR) secretion and decreases Notum secretion, which, in turn, enhances ISC functions. In this work, our findings substantiate the role of ALA in inhibiting human ISC aging and present a potential therapeutic approach for managing age-related human intestinal diseases.

Subject terms: Ageing, Ageing, Stem-cell niche, Intestinal stem cells

This study reveals that α-lipoic acid (ALA) is reduced in aged mouse and human intestine and ALA supplementation reduces aging hallmarks. Paneth cells play a role in the effects of ALA.

Introduction

The small intestine is a vital organ in the human body responsible for the digestion of food and the absorption of nutrients. Additionally, the epithelial cells of the small intestine also form a tight barrier against the lethal microorganisms and toxins from the intestinal lumen, resulting in the loss of approximately 10 billion epithelial cells from the human body every day1,2. The healthy small intestine possesses a remarkable capacity for self-renewal, and the intestinal stem cells (ISCs) can replenish damaged epithelial cells through rapid proliferation and differentiation1,3. However, the aging process can negatively impact the regenerative ability of ISCs4, leading to a decline in the absorptive ability, barrier function, and immune function of the small intestines5. Ultimately, the risks of multiple diseases like malnutrition, intestinal inflammation, chronic constipation, and intestinal tumors are increased in elderly populations6. As a result, there has been a growing interest in finding ways to inhibit the aging of ISCs4.

Our previous study screened out that α-lipoic acid (ALA), an organosulfur compound also known as thioctic acid, possessed the ability to reverse age-associated dysfunction of Drosophila midguts7. The similarities between the biological functions of Drosophila midguts and mammalian small intestines suggest the potential of ALA in inhibiting ISC aging in humans8. Additionally, given that the epithelial structures and cell compositions are quite different between Drosophila and mammals9,10, further investigation is required to determine whether ALA can inhibit human ISC aging and improve age-related intestinal disease in humans.

The human small intestine epithelium is folded into millions of finger-like villi and valley-like crypts8, and the ISCs are located at the crypt bases10. These intestinal crypts offer specialized microenvironments, commonly referred to as ISC niches, that sustain ISC survival and function9. Among the integral components of these niches are Paneth cells, which are exclusive to mammalian small intestine and do not occur within invertebrate intestine (Fig. 1a)11. Beyond their role in protecting the intestinal epithelia through antimicrobial peptide secretion, including lysozyme and defensins, Paneth cells are instrumental in maintaining ISC niche homeostasis by delivering a range of signals12,13. These specific structures enable the crypts of the mammalian small intestine to serve as a foundation for intestinal organoid development in vitro, and these intestinal organoids are capable of replicating the self-organizing capacity of ISCs and imitating intestinal epithelium formation14. Therefore, intestinal organoids are recognized as ideal in vitro tools for ISC research and are used to identify drug efficacy for gut diseases15. However, due to the restricted accessibility of human small intestine tissue, the majority of studies utilize intestinal organoids derived from mice. Although mouse models have greatly helped us develop many potential therapeutic strategies for human diseases, inherent species differences exist. For instance, disparities between humans and mice in the timeline of embryonic intestinal development imply that animal study results may not be accurately extrapolated to human tissues16. It is thus imperative to investigate drugs that prevent ISC aging in human intestinal tissues and organoids to yield more clinically valuable outcomes.

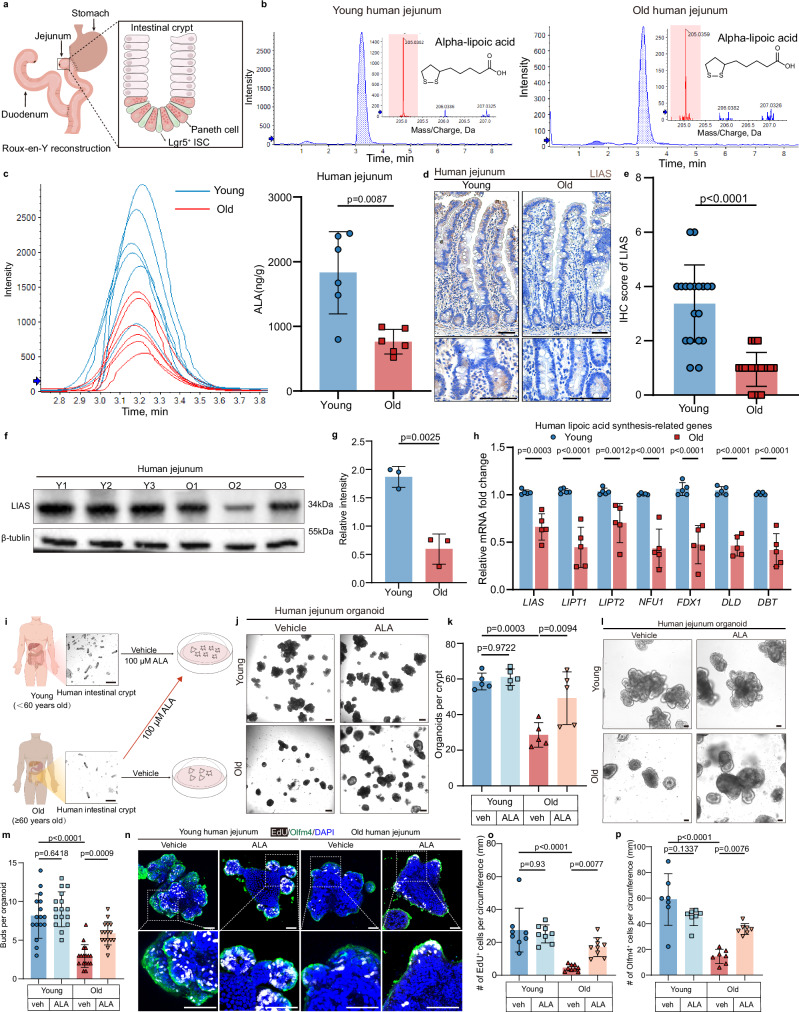

Fig. 1. ALA synthesis decreases in small intestines of old human, and ALA supplementation inhibits human ISC aging.

a Schematic of human jejunal tissue collection during Roux-en-Y reconstruction and crypt structure. b LC-ESI-MS/MS chromatograms of ALA in young and old human jejunum. c ALA levels quantified by LC-ESI-MS/MS (n = 6 biologically independent donors per group). d, e Representative LIAS immunohistochemistry (scale bars, 75 μm) in jejunum from young (n = 6) and old (n = 8) donors (d) and quantification (n = 19 crypts per group, from 6 donors) (e). f, g Immunoblot (f) and quantification (g) of LIAS (n = 3 donors per group). h RT-qPCR of LIAS-pathway genes (n = 5 donors per group). i Schematic diagram (scale bars, 250 μm) of small intsetinal organoid culture from young and old human crypts. The figure was created by figdraw.com. j–p Organoids from young and old donors treated with vehicle or ALA (100 μM) for 7 days. Representative organoid images (scale bars, 250μm) (j), Organoid number per crypt (n = 6 biologically independent donors/group) (k), representative images of organoid buds (l, scale bars, 75 μm), buds per organoid (n = 16 organoids/group, from 6 donors) (m), organoids stained with DAPI (blue), Olfm4 (green), EdU (white) (scale bars, 100μm) (n), and EdU⁺ cell quantification, from left to right, n = 8, 8, 9, 9 in (o), from 6 donors. Olfm4⁺ cells per organoid (n = 7 organoids, from 6 donors) (p). Each organoid is considered a technical replicate; Human donor is the biological replicate. Data information: Error bars s.d. P values: One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (k, m, o, p): (m), p = 1e–8 for young vs old; (o), p = 5e–6 for young vs old; (p), p = 6e–7 for young vs old. Two-way ANOVA analysis followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (h), p = 1e–8 for LIPT1 and DBT, p = 3e–8 for NFU1, p = 2e–8 for FDX1 and DLD. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (c, e), p = 3e–7 for (e). and unpaired, two-tailed t test (g). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In this work, we find that ALA supplementation remarkably reverses the aging phenotypes of ISCs. Additionally, we identify that the inhibiting effects of ALA on ISC aging are dependent on the presence of Paneth cells. Inhibiting the mTOR pathway in Paneth cells with ALA or rapamycin significantly increase cyclic ADP ribose (cADPR) secretion and decrease the Notum secretion, which enhances ISC functions. These results imply a potential therapeutic role for ALA in the treatment of aging-associated human intestinal diseases.

Results

The synthesis of ALA in human small intestines reduces upon aging

Our previous research demonstrated a decrease in ALA abundance in the aged midguts of Drosophila7. However, whether this decrease occurs in the small intestines of old humans remains unknown. To address this question, we collected normal jejunum tissues from patients of gastric cancer undergoing Roux-en-Y reconstruction (Fig. 1a). The levels of ALA in the human small intestine samples were quantified by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a), and we found significantly lower jejunal ALA levels in old humans than in young humans (Fig. 1b, c). Since ALA can be synthesized endogenously in mitochondria17, we investigated the expression of lipoic acid synthetase (LIAS), a key enzyme involved in ALA synthesis, in the jejunum through immunohistochemistry and western blot analysis. Our results indicated a marked decrease in LIAS expression in the jejunum of elderly individuals compared to young individuals (Fig. 1d–g). In addition, the mRNA levels of genes related to the formation of LIAS and ALA, including LIAS, LIPT1, LIPT2, NFU1, FDX1, DLD, and DBT18, were significantly decreased in old human jejunum (Fig. 1h). Diminished expression of LIAS and related genes was also observed in the small intestines of old mice compared to young mice (Supplementary Fig. 1b–d). These data indicate that ALA synthesis in human small intestines is reduced upon aging.

ALA supplementation inhibits aging phenotypes in cultured human small intestinal organoids

To investigate the potential effect of age-associated ALA reduction on the decline in ISC regenerative capacity in old humans, we cultured intestinal organoids from the small intestinal crypts of young and old humans (Fig. 1i). The human intestinal crypts were cultured in basal medium with or without the addition of 100 μM ALA as indicated (Fig. 1i). We found that the intestinal crypts from older humans generated significantly fewer intestinal organoids (Fig. 1j, k) and organoid buds (Fig. 1l, m) compared to those from younger individuals, indicating impaired ISC proliferation and differentiation capacity in older humans. Additionally, the intestinal organoids from older humans exhibited a marked decrease in EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs (Fig. 1n–p). These organoid experiments further confirmed the impaired proliferation capacity of ISCs in older humans. Of note, supplementation with ALA led to a significant enhancement in the organoid-forming capacity (Fig. 1j, k) and organoid bud formation (Fig. 1l, m) in crypts from old humans, as well as boosting the amounts of EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs in intestinal organoids of old humans (Fig. 1n–p). ALA supplementation did not further promote the organoid-forming capacity or organoid bud formation or increase the amount of EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs in the intestinal organoids of young humans (Fig. 1j–p). Collectively, these data confirm that ALA supplementation could inhibit ISC dysfunction in old human small intestinal organoids.

ALA supplementation inhibits ISC aging and promotes intestinal epithelium regeneration in old mice

To investigate the effects of ALA on inhibiting ISC aging in vivo, young and old male mice were administered ALA (100 mg/kg/day) for 3 months; mice receiving regular drinking water served as controls (Fig. 2a). Compared to those of the young control mice, the number of SOX9+ ISCs, EdU+ cells, and SOX9+ EdU+ ISCs were significantly decreased in the intestinal crypts of old mice (Fig. 2b–e). In contrast, ALA supplementation significantly mitigated the decrease in SOX9+ ISCs, EdU+ cells, and SOX9+ EdU+ ISCs in old mice (Fig. 2b–e). Furthermore, we found decreased expression of Olfm4 in intestinal crypts of old mice, and ALA supplementation increased the expression of Olfm4 in old mouse crypts as well (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Moreover, in old mice, the level of Occludin and Claudin-1 in the small intestine were significantly reduced, indicating a decline in gut barrier function (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d). Conversely, ALA markedly elevates the expression of Occludin and Claudin-1 in old mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d). Previous studies have highlighted the crucial role of healthy mitochondria in ISC renewal12, with mitochondrial abnormalities being a key feature of ISC aging19. Using transmission electron microscopy, we found that the proportion of mitochondria with compromised cristae integrity is significantly higher in the ISCs of old mice compared to their younger counterparts (Fig. 2f, g). Importantly, ALA significantly increased the proportion of normal mitochondria in old mice (Fig. 2f, g). Notably, ALA supplementation did not have significant effects on the number of SOX9+ ISCs, EdU+ cells, and the mitochondrial cristae integrity of ISCs in young mice (Fig. 2b–g).

Fig. 2. ALA inhibits ISC aging and promotes epithelial regeneration in old mice.

a–g Young and old mice were treated with vehicle (veh) or ALA (100 mg/kg/day) in drinking water for 3 months. Experimental design (a), EdU (red) and SOX9(green) staining (b, scale bars, 25μm), yellow arrow: ISCs, and quantification of crypts (c–e, n = 16 crypts/group from 7 mice;). TEM analysis of ISC mitochondria (f, scale bars: 1μm and 500 nm; (g), n = 15 ISCs/group from 3 mice). Yellow dashed lines: ISCs; M (red), ISC mitochondria; N (blue), nucleus. h–p Crypts from young and old mice were cultured with vehicle or ALA (100 μM) for 6 days. Experimental design (h), representative images of intestinal organoids (i, scale bars, 250 μm), organoid number(j, n = 7 mice/group, each biological replicate represents an independent organoid culture from one mouse), bud morphology (k, scale bars, 50μm), and quantification (l, n = 26 organoids/group from 7 mice), RT-qPCR of Lgr5, Olfm4, and Ascl2 (n = 6 mice/group) (m), staining of DAPI, Olfm4, and EdU (n, scale bars, 50μm); quantification of EdU⁺ and Olfm4⁺ cells (o, p, n = 14 organoids/group from 7 mice) q–u Young and old mice were injected with indomethacin (10 mg/kg) for 1 day followed by 7 days vehicle or ALA. Experimental design (q). H&E staining and histology scores (r, s, scale bars, 75μm; n = 5 mice/group), TEM images of crypts (t, 1 μm and 500 nm) and mitochondrial integrity quantification (u, n = 15 cells from 3 mice/group). Yellow lines: ISCs; N (blue), nucleus; M (red), mitochondria. Data are mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (c–e, j, l, o, p): (c), p = 4e–9 (young vs old), 8e–9 (old vs old+ALA); (l), p = 2e–9 (young vs old); (p), p = 6e–10 (young vs old), 3e–7 (old vs old+ALA). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s (g, m) or Sidak’s test (s, u): (g) within 0–50% mitochondrial integrity, p = 8e–9 (young vs old), 1e–10 (young vs old+ALA, old vs old+ALA); (m) p = 8e–6 for Olfm4 (old vs old+ALA); (u) at 0–50% integrity, p = 2e–7; at 0%, p = 1e–15. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further validate the effect of ALA on promoting the regenerative capacity of ISCs in old mice, we cultured intestinal organoids derived from small intestinal crypts of male mice in basal medium with or without the addition of 100 μM ALA (Fig. 2h). As expected, the intestinal crypts of old mice formed significantly fewer intestinal organoids (Fig. 2i, j) and organoid buds (Fig. 2k, l) than those of young mice. Besides, intestinal organoids developed from old mouse crypts exhibited significantly lower expression of ISC biomarkers, including Lgr5, Olfm4, and Ascl2 (Fig. 2m), along with a notable decrease in the number of EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs (Fig. 2n–p). Consistent with the findings for human intestinal crypts, ALA supplementation significantly promoted the crypt organoid-forming capacity (Fig. 2i, j) and increased the number of organoid buds (Fig. 2k, l) in old mice. Furthermore, ALA supplementation also increased the expression of ISC biomarkers (Fig. 2m) and number of EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs (Fig. 2n–p) in the intestinal organoids of old mice. However, ALA supplementation did not have significant effects on the organoid-forming capacity (Fig. 2i, j), organoid bud formation (Fig. 2k, l), ISC biomarker expression (Fig. 2m), or the number of EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs (Fig. 2n–p) in the intestinal organoids from young mice. Of note, ALA supplementation also enhanced the function of ISCs in organoids derived from old female mice (Supplementary Fig. 2e–l).

To investigate whether ALA supplementation can improve the repair ability after intestinal injury, we established indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury models in mice as previously reported (Fig. 2q)20. Initial observations one day after indomethacin injection revealed small intestinal ulcers in all mouse groups, with no significant differences in histological scores among them (Fig. 2r, s). Meanwhile, there were no significant differences in the number of SOX9+ ISCs, EdU+ cells, and SOX9+ EdU+ ISCs among the groups (Supplementary Fig. 2m–p). By the seventh day post-indomethacin injection, old mice receiving only drinking water exhibited markedly higher histological scores compared to young mice, indicating a decrease in small intestine regeneration capacity. Conversely, ALA supplementation significantly improved the intestinal epithelium regeneration in old mice, as evidenced by reduced histological scores (Fig. 2r, s). Furthermore, on the seventh day post-indomethacin injection, the number of SOX9+ ISCs, EdU+ cells, and SOX9+ EdU+ ISCs in the intestinal crypts of old mice was significantly lower than that in young mice (Supplementary Fig. 2q–t). Importantly, ALA supplementation significantly increased the number of SOX9+ ISCs, EdU+ cells, and SOX9+ EdU+ ISCs in the intestinal crypts of old mice, with no notable effect on young mice (Supplementary Fig. 2q–t). Notably, nearly all EdU+ cells were located within the intestinal crypts and co-localized with SOX9+ ISCs or transit-amplifying (TA) cells (Supplementary Fig. 2m–t). These results indicate that during the intestinal repair process in aged mice, ALA promotes the proliferation of ISCs, rather than other mature differentiated non-ISC cells. Additionally, on day seven after indomethacin injection, we observed that the proportion of mitochondria with compromised cristae integrity is significantly higher in old mice treated with drinking water than those receiving ALA supplementation (Fig. 2t, u). Overall, these data suggest that ALA supplementation can inhibit ISC aging and promote intestinal epithelium regeneration in old mice.

ALA supplementation restores abnormal Paneth cell accumulation in human and mouse intestines upon aging

Paneth cells are the main components of small intestinal crypts, with prior investigations indicating an elevated presence of Paneth cells within the intestinal crypts of old mice4,9. In this study, we also observed dramatically increased numbers of Paneth cells in the small intestinal crypts of old humans compared to young humans (Fig. 3a, b). The morphological characteristics of lysozyme staining granules in Paneth cells, as visualized through immunofluorescence, serve as indicators of the functional state of Paneth cells. In humans, these morphologies are classified as normal state (D0) or 5 abnormal categories (D1: disordered; D2: diminished; D3: diffuse; D4: excluded; D5: enlarged) (Fig. 3c). In mice, the granule morphology of lysozymes in Paneth cells can be categorized as normal (D0) or 3 abnormal categories (D1: disordered; D2: depleted; D3: diffuse) (Supplementary Fig. 3a)21,22. Notably, a significantly higher percentage of abnormal lysozyme staining was observed in intestinal crypts of old humans compared to young humans (Fig. 3d, e), indicating an increased number of abnormal Paneth cells in small intestines of old humans. In addition, the small intestines of mice (as indicated in Fig. 2a) were subjected to lysozyme immunofluorescence staining. Compared to those of young control mice, the intestinal crypts of the old mice had significantly increased numbers of Paneth cells (Fig. 3f, g) and higher percentages of abnormal lysozyme staining (Fig. 3h, i). Notably, ALA supplementation significantly reduced the numbers of Paneth cells and the percentages of abnormal lysozyme staining in old mice, but had no significant effects on Paneth cells in young mice (Fig. 3f–i). Consistent with these findings, transmission electron microscopy revealed an increased prevalence of abnormal secretory granules in the Paneth cells of old mice compared to young mice, with ALA supplementation ameliorating the secretory granule abnormalities in the Paneth cells of old mice but not young mice (Fig. 3j). Additionally, Tunel staining indicated no significant differences in apoptosis among the Paneth cells across the groups (Supplementary Fig. 3b), suggesting that the reduction of Paneth cells in old mice treated with ALA is unrelated to apoptosis.

Fig. 3. ALA supplementation restores abnormal Paneth cell accumulation in human and mouse intestines upon aging.

a, b Representative images of Paneth cells (a, scale bars, 50 μm) and quantification in young and old human crypts (b, n = 27 crypts/group from 6 independent donors). c–e Diagram of lysozyme distribution patterns: normal (D0), disordered (D1), diminished (D2), diffuse (D3), excluded (D4), enlarged (D5) (c). Representative staining showing lysozyme granules (d, scale bars, 25 μm); white/yellow arrowheads indicate normal/abnormal granules. Quantification of distribution patterns (e, n = 15 crypts/group from independent 6 donors). f–j Young and old mice were administered drinking water with vehicle or ALA (100 mg/kg/day) for 3 months. Representative images of Paneth cells (f, scale bars, 75 μm), and quantification (g, n = 33 crypts/group from 7 biologically independent mice), Representative images showing lysozyme granules (h, scale bars, 10 μm; white/yellow arrowheads indicate normal/abnormal granules in Paneth cells). Distribution of lysozyme patterns (i, n = 14 crypts/group from 7 mice). Representative TEM images of Paneth cells (j, scale bars, 1μm; yellow/red stars indicate normal/abnormal granules). k, l Intestinal crypts from young and old humans were cultured with vehicle or ALA (100 μM) for 7 days. Representative lysozyme staining in organoids (k, scale bars, 75μm) and Paneth cell quantification (l, n = 7 organoids/group from 3 independent human donors). m–p Mouse intestinal crypts were cultured with vehicle or ALA (100 μM) for 6 days. Representative lysozyme staining (m, scale bars, 75μm) and Paneth cell quantification (n, n = 18 organoids/group from 7 mice). ELISA of Reg3g and Defa6 in organoid supernatants (o, p, n = 3 biological replicates/group). All data are mean ± SD. P values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed t test (b), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (g, l, n, o, p); for (n), p = 6e–9 (young vs old), 8e–5 (old vs old+ALA). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s test (e); for (e), p = 2e–8 (young vs old within D0 and D1–D5). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (i). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Given the ablating effects of ALA on the abnormal Paneth cell accumulation in the intestinal crypts of old mice, we next sought to determine whether ALA elicited similar effects in the small intestines of old humans. To accomplish this, intestinal organoids were derived from young and old human small intestinal crypts (as described in Fig. 1i). In line with the intestinal crypts of humans, we observed significantly more Paneth cells in the intestinal organoids of old humans than in those of young humans, while ALA markedly reduced the number of Paneth cells in the intestinal organoids of old humans (Fig. 3k, l). Meanwhile, we also observed a significant increase in the number of Paneth cells in organoids derived from old male or female mice, while ALA treatment significantly reduced the number of Paneth cells in these organoids (Fig. 3m, n and Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). Furthermore, we isolated Paneth cells from mouse intestinal organoids and found that the expression of Reg3g and Defa6, the key functional markers of Paneth cells23,24, was significantly reduced in Paneth cells derived from old mouse organoids (Supplementary Fig. 3e–h). Importantly, ALA markedly enhanced the expression of Reg3g and Defa6 in old Paneth cells (Supplementary Fig. 3e–h). Additionally, we found that ALA promotes the expression of REG3G and DEFA6 in old human Paneth cells (Supplementary Fig. 3i), as well as significantly increasing the secretion of lysozyme (Supplementary Fig. 3j). Notably, The ELISA indicated that ALA supplementation significantly increased the levels of Reg3g and Defa6 in the supernatant of old mouse and human intestinal organoids (Fig. 3o, p; Supplementary Fig. 3k, l). Collectively, our data suggest that ALA supplementation can restore the accumulation of abnormal Paneth cells in small intestines of old humans and mice.

Inhibition of ALA synthesis in young mice replicates the aging phenotype of small intestines in old mice

After observing a decrease in ALA synthesis in human and mouse small intestines upon aging, we next assessed whether suppressing ALA synthesis in young mice could replicate the aging-related changes observed in the small intestines. To induce inhibition of ALA synthesis, we administered elesclomol and PF9366 in our subsequent experiments. Elesclomol functions by impeding the production of Fe-S clusters, a critical constituent of LIAS crucial for enzymatic activity, thereby diminishing the synthesis of ALA18,25,26. Conversely, PF9366, a methionine adenosyltransferase 2A (MAT2A) inhibitor, hampers the generation of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), consequently impeding LIAS function27,28.

The intestinal crypts of young mice were cultured with either 10 μM elesclomol or 0.5 μM PF9366, and intestinal crypts cultured with basal medium were used as controls (Fig. 4a). Using LC-ESI-MS/MS, we found that intestinal organoids cultured with elesclomol or PF9366 intervention had a dramatic decrease of ALA levels compared to the controls (Fig. 4b, c). Furthermore, intestinal crypts cultured with elesclomol or PF9366 formed significantly fewer intestinal organoids (Fig. 4d, e) and organoid buds (Fig. 4d, f) compared to the controls. In addition, intestinal organoids cultured with elesclomol or PF9366 intervention displayed a significantly increased number of Lysozyme+ Paneth cells (Fig. 4g, h) and decreased number of Lgr5+ ISCs (Fig. 4g, i). Notably, compared to the intestinal crypts cultured with elesclomol or PF9366 alone, additional supplementation with 100 μM ALA significantly increased the intestinal organoids formations (Fig. 4d, e), organoid buds (Fig. 4d, f), Lgr5+ ISCs (Fig. 4g, i), and decreased the number of Paneth cells (Fig. 4g, h). In addition, we introduced siRNA targeting Lias (siLias) into young intestinal organoids, resulting in a significant reduction in Lias expression (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). We observed that the suppression of Lias expression using siRNA elicited effects comparable to those observed with elesclomol or PF9366, including decreased intestinal organoids formations, organoid buds, Lgr5+ ISCs, and increased number of Paneth cells (Supplementary Fig. 4c–h). Furthermore, ALA significantly ameliorated the aging phenotype induced by siLias in these organoids (Supplementary Fig. 4c–h). These findings suggest that suppressing ALA synthesis through elesclomol, PF9366, or siLias induced aging phenotypes in intestinal organoids of young mice, a condition that could be reversed by ALA administration.

Fig. 4. ALA biosynthesis suppression mimics intestinal aging in young mice.

a–c Crypts from young mice were cultured for 6 days with vehicle, elesclomol, PF9366, with/without ALA. Schematic of treatment groups (a). LC-ESI-MS/MS chromatograms (b), and ALA quantification (c, n = 3 mice/group). d–i Representative images (d) (scale bars: 250 μm/50 μm) and quantitation of organoid number (e, n = 5 mice/group) and buds (f, veh: n = 13, elesclomol: n = 16, elesclomol+ALA and PF9366: n = 14, PF9366 + ALA: n = 15 organoids, all from 5 mice). Immunofluorescence for Lgr5-EGFP (green), Lysozyme (red). (g, scale bars, 50 μm, n = 6 mice/group). Quantification of Lysozyme⁺ (h, veh and PF9366 + ALA: n = 25, elesclomol: n = 35, elesclomol+ALA: n = 29, PF9366: n = 22 organoids) and Lgr5⁺ cells (i, veh, elesclomol+ALA, PF9366 + ALA: n = 19 organoids; elesclomol, PF9366: n = 18 organoids, all from 6 mice). j–r Young and old mice were injected with veh or elesclomol (j). SOX9⁺ staining (k, scale bars: 25 μm) and quantification (l, n = 10 crypts/group). Lysozyme staining (m, scale bars, 75 μm) and Paneth cell counts (n, n = 15 crypts/group, from 6 mice). Representative lysozyme granule images (o, scale bars, 10 μm; white arrowheads: normal, yellow: abnormal). Percentage of abnormal Paneth cells (p, n = 14 crypts/group). TEM of intestinal crypts (q, red dashed: Paneth cells; yellow: ISCs; yellow/red stars: normal/ abnormal granules; N, nucleus; L, lumen; M, mitochondria; scale bars: 5μm, 1μm) and mitochondrial integrity quantification (r, n = 15 cells/group from 3 mice). Data represent mean ± SD. P values: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (c, e, f, h, i, l, n); f p = 5e−11 (vehicle vs elesclomol), 1e−12 (vehicle vs PF9366); h, p = 4e−10 (veh vs elesclomol), 1e−11 (veh vs PF9366); 4e−13 (elesclomol vs elesclomol+ALA), 4e−11 (PF9366 vs PF9366 + ALA); i, p = 1e−7 (veh vs elesclomol), 7e−8 (veh vs PF9366), 3e−6 (PF9366 vs PF9366 + ALA). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s test (p) and Tukey’s test (r); p, within D0, p = 1e–9 for young vs old; within D1–D3, p = 1e–9 for young vs old; r, within the 0–50%, p = 5e–6 (young vs young+elesclomol); within 50–100%, p = 2e–13 (young vs young+elesclomol); Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore the impact of inhibiting ALA synthesis on small intestine in vivo, young mice were injected with 50 mg/kg elesclomol, while young and old mice injected with vehicle served as controls (as depicted in Fig. 4j). In comparison to the young control mice, the young mice injected with elesclomol had a significant reduction in SOX9+ ISCs (Fig. 4k, l) and Olfm4 expressions (Supplementary Fig. 4i) within their intestinal crypts, similar to the results in old mice. Moreover, young mice injected with elesclomol demonstrated a notable increase in the number of Paneth cells (Fig. 4m, n) and a higher proportion of Paneth cells exhibiting abnormal lysozyme staining in the intestinal crypts (Fig. 4o, p). Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy revealed that young mice injected with elesclomol exhibited a higher proportion of mitochondria with compromised cristae integrity in ISCs and a higher prevalence of abnormal secretory granules in Paneth cells (Fig. 4q, r). Collectively, these results indicate that inhibition of ALA synthesis in young mice could replicate the aging phenotypes of small intestines.

ALA delays ISC aging through a Paneth cell-dependent mechanism

To investigate the potential mechanisms by which ALA improves the function of aging ISCs, we first examined whether ALA affects the gut microbiota in old mice. 16S rRNA sequencing was performed in both control and ALA intervention old mice. The results indicated that the community composition of the gut microbiota was similar between the two groups, with no significant differences observed in either β diversity or α diversity (Supplementary Fig. 5a–g). These findings suggest that the mechanism by which ALA improves the function of aging ISCs is independent of the gut microbiota.

Having observed substantial alterations in Paneth cells and ISCs with ALA supplementation during aging, we isolated Paneth cells and ISCs from the intestinal crypts of old mice and old mice subjected to ALA intervention. We found that the ALA content in the Paneth cells and ISCs of the ALA intervention group was significantly higher than that in the control group, indicating that the administration of ALA to old mice significantly promotes an increase in the intracellular levels of ALA in Paneth cells and ISCs (Supplementary Fig. 5h–k).

To elucidate the potential association between Paneth cells and the inhibitory effects of ALA on ISC aging, we established a co-culture system utilizing Lgr5+ ISCs and CD24+ Paneth cells (Fig. 5a). The Lgr5+ ISCs were isolated from intestinal organoids of young mice, and the CD24+ Paneth cells were isolated from the intestinal organoids of both young and old mice (Fig. 5b). Following a three-day co-culture period, spheroid organoids were observed in all groups (Fig. 5c). Subsequent examination after eight days of co-culture revealed that intestinal organoids derived from the co-culture of ISCs and old Paneth cells exhibited aging characteristics compared to those from the co-culture of ISCs and young Paneth cells, evidenced by a notable reduction in intestinal organoids and organoid bud formations (Fig. 5d–f). Importantly, the supplementation of 100 μM ALA in the co-culture of ISCs and old Paneth cells resulted in a significant increase in intestinal organoids and organoid bud formations (Fig. 5d–f).

Fig. 5. ALA delays ISC aging through a Paneth cell-dependent mechanism.

a–f Lgr5hi cells from young Lgr5-EGFP mice and CD24+ Paneth cells from both young and old mice were sorted and co-cultured in matrigel. Schematic diagram illustrating the sorting procedure of ISCs and Paneth cells using flow cytometry (a). Representative FACS plots of Lgr5-EGFP+ cells and CD24+ Paneth cells from the intestinal organoids of young Lgr5-EGFP mice and old C57BL/6 mice (b). (n = 3 biologically independent mice per group). Representative images of Lgr5hi ISCs co-cultured with Paneth cells from young and old mice at day 3 (c) and 8 (d). (scale bars: 250 μm). The number of colonies (e) and buds (f) at day 8. (e): n = 3 biologically independent co-culture replicates per group. (f): n = 9 organoids/group, obtained from 3 biologically independent mice. g–k The diagram (g) showing the workflow for preparing conditioned media from organoids of young and old mice. Lgr5hi cells were cultured with conditioned media or conditioned media+ALA. Representative images (h, i, scale bars, 250 μm) of organoids derived from young Lgr5hi ISCs. Quantification of organoids (j) and organoid buds (k) in each group. (j): n = 4 biologically independent mice replicates per group. (k): n = 12 organoids/group, obtained from 4 biologically independent mice. Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as the mean ± SD. one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (e, f, j, k); for (k), p = 1e−7 for young CM vs old CM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In order to replicate the ISC microenvironment in the absence of Paneth cells, conditioned medium (CM) was collected from intestinal organoids of young and old mice as previously reported29. The Lgr5+ ISCs sorted from intestinal crypts of young mice were co-cultured with CM (Fig. 5g). After co-culture for three days, spheroid organoids appeared in each group (Fig. 5h). By the eighth day, ISCs co-cultured with CM from old intestinal organoids exhibited a significant decrease in intestinal organoids and organoid buds compared to those co-cultured with CM from young intestinal organoids (Fig. 5i–k). Notably, ALA supplementation had no significant effect on the formation of intestinal organoids or organoid buds in ISCs co-cultured with CM from old intestinal organoids (Fig. 5i–k).

Furthermore, we also performed similar experiments with isolated old ISCs (Supplementary Fig. 5l). The old ISCs co-cultured with old Paneth cells or CM from old intestinal organoids exhibited a significant decrease in intestinal organoids, organoid buds, EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs compared to those co-cultured with young Paneth cells or CM from young intestinal organoids (Supplementary Fig. 5m–x). Importantly, ALA significantly increased intestinal organoids, organoid buds, EdU+ cells and Olfm4+ ISCs in old ISCs co-cultured with old Paneth cells rather than those co-cultured with CM from old intestinal organoids (Supplementary Fig. 5m–x). Collectively, these results indicate that ALA regulates ISC proliferation and differentiation through a Paneth cell-dependent manner.

ALA inhibits mTOR pathway activity in Paneth cells of old mice

To gain insight into the underlying mechanisms of how Paneth cells regulate the effect of ALA on inhibiting ISC aging, transcriptome sequencing was conducted on intestinal organoids of old mice cultured with or without 100 μM ALA (data shown in Supplementary Data 2). Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated distinct clustering patterns between old intestinal organoids with and without ALA supplementation (Fig. 6a), indicating a significant difference in gene transcription levels between these two groups. Subsequent Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses revealed transcript enrichment of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in various signaling pathways within the intestinal organoids of the two groups (Fig. 6b, c). In particular, both KEGG and GO exhibited an enrichment in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway (Fig. 6b, c). Additionally, volcano plots (Fig. 6d) and a heatmap (Fig. 6e) illustrated significant down-regulation of transcripts associated with mTOR-related genes, such as Lpin3, Slc3a2, Eif4ebp1, Atp6v1e1, and Sec1330–33, in old intestinal organoids cultured with ALA compared to those cultured in basal medium alone. Moreover, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analyses confirmed that the mRNA levels of these mTOR-related genes were significantly decreased in old intestinal organoids cultured with ALA (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6. mTOR pathway activity in Paneth cells of old mice is inhibited by ALA.

a–f Intestinal organoids of old mice cultured with or without ALA were used for RNA sequencing and RT-qPCR. (n = 3 biologically independent mice per group). Principal-component analysis (PCA) (a) of the transcriptomes. KEGG (b) and GO (c) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. Volcano plot (d). Each dot represents a gene; Blue symbols represent significantly down-regulated mass bins (Log2 FC < −0.4 and p < 0.05), red symbols represent significantly upregulated mass bins (Log2 FC > 0.4 and p < 0.05), while gray symbols indicate non-significantly altered mass bins. Heatmap showing the expression of key genes related to the mTOR signaling pathway (e). The color code shows the Z score for each gene along the whole dataset. mRNA expression of indicated genes (f) (n = 4 biologically independent mice per group). g Crypts isolated from young and old mice were cultured with/without ALA for 6 days (n = 4 biologically independent mice per group). Representative images (scale bars, 50 μm) of immunostaining with pS6 (green), Lysozyme (red) and DAPI (blue) in each group. The dotted circle indicates Paneth cells. h The expression of lysozyme (red) and pS6 (green) was detected in mouse intestinal crypts from different groups by immunofluorescence (scale bars, 100 μm). The dotted circle denotes Paneth cells (n = 7 biologically independent mice per group). i, j Paneth cells were sorted from young and old mice treated with or without ALA (n = 3 biologically independent mice per group). Representative immunoblots of indicated proteins in Paneth cells (i) and quantification of p4E-BP1 and pS6 expression (j) (n = 3 biologically independent mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (j) and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (f). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Previous studies have reported that the mTOR pathway plays an important role in regulating the homeostasis of mouse ISC niches by affecting the functions of Paneth cells or ISCs34. To investigate the impact of ALA on the mTOR pathway expression in Paneth cells and ISCs, we utilized immunofluorescence techniques to assess the presence of phosphorylated S6 (pS6), a marker indicative of mTOR pathway activation35, within mouse intestinal crypts and organoids. In organoids derived from old mice, immunofluorescence staining revealed significant colocalization of pS6 in Paneth cells, as demonstrated by dual staining with anti-pS6 and anti-lysozyme antibodies (Fig. 6g). Conversely, in organoids from young mice or old mice treated with ALA, minimal pS6 staining was observed in Paneth cells (Fig. 6g). Additionally, elevated pS6 expression was detected in Paneth cells of old mouse intestinal crypts, whereas Paneth cells in crypts of young mice or old mice supplemented with ALA exhibited reduced pS6 expression levels (Fig. 6h). Moreover, we sorted Paneth cells from intestinal crypts of young mice, old mice, and old mice fed with ALA. Western blot uncovered a significantly higher expressions of two mTOR pathway-related markers, p4E-BP136 and pS6, in Paneth cells of old mice than those of young mice (Fig. 6i, j). Of note, ALA prevented the up-regulation of p4E-BP1 and pS6 in mouse Paneth cells upon aging (Fig. 6i, j).

We observed that EdU+ ISCs and/or TA cells from old mouse intestinal organoids had more pS6 expressions than those from young mouse (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Furthermore, pH3+ ISCs and/or TA cells were markedly colocalized to pS6 in intestinal crypts of old mice instead of young mice (Supplementary Fig. 6b). We also isolated ISCs from young mice, old mice, and old mice fed with ALA. As expected, the expressions of p4E-BP1 and pS6 were significantly higher in ISCs of old mice than the young mice (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). Our findings suggested an increased expression of mTOR pathway in ISCs upon aging, which was consistent with the previous study that reported enhanced mTOR activation in ISCs/TA cells of old mice3. Notably, we found that ALA supplementation did not significantly inhibit the expression of mTOR pathway in ISCs of old mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a–d). Collectively, these results suggest that ALA inhibit the activity of mTOR pathway in Paneth cells instead of ISCs in old mice.

To explore the potential mechanisms by which ALA affects the mTOR pathway, we conducted a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network analysis. The results revealed that LIAS is closely associated with O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT) (Supplementary Fig. 6e), an upstream protein that positively regulates the activity of mTOR pathway37. To further validate the direct interaction between ALA and OGT, we performed the molecular docking and biolayer interferometry (BLI), which demonstrated a significant binding affinity between ALA and OGT (Supplementary Fig. 6f–h). Subsequently, we observed that the OGT inhibitor, OSMI-138, significantly increased the intestinal organoids formations, organoid buds, Olfm4+ ISCs, and decreased the number of Paneth cells in old mouse organoids (Supplementary Fig. 6i–p). Furthermore, OSMI-1 significantly reduced the expression of p4E-BP1 and pS6 in old Paneth cells, suggesting that mTOR pathway activity is suppressed (Supplementary Fig. 6q, r).

ALA supplementation inhibits ISC aging by regulating the mTOR-dependent cADPR and Notum paracrine in Paneth cells

We have identified that ALA inhibits ISC aging through a Paneth cell-dependent mechanism, with ALA leading to a down-regulation of the mTOR pathway in Paneth cells. However, the specific involvement of Paneth cells in the inhibitory effect of ALA on ISC aging remains unclear (Fig. 7a). Paneth cells can regulate the function of ISCs by secreting specific signal molecules10, and it was reported that inhibition of mTOR pathway by calorie restriction or rapamycin could promote the paracrine of cADPR in Paneth cells, thereby enhancing the function of ISCs39. To explore whether ALA supplementation also promotes the secretion of cADPR in Paneth cells, the level of cADPR was examined in mouse Paneth cells and intestinal organoids using ELISA. We found a notable decrease in cADPR levels in Paneth cells isolated from intestinal crypts of old mice than those from young mice, while ALA administration significantly increased the cADPR levels in Paneth cells isolated from old mice (Fig. 7b). There was no significant difference in cADPR levels of Paneth cells between young mice with and without ALA administration (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, old mouse intestinal organoids exhibited significantly lower cADPR levels compared to young mouse organoids, while ALA or rapamycin administration substantially increased cADPR levels in old mouse intestinal organoids (Fig. 7c). Of note, the MHY1485, an activator of mTOR, could counteract the effect of ALA on increasing the cADPR in intestinal organoids of old mice (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7. ALA supplementation inhibits ISC aging by regulating the mTOR-dependent cADPR paracrine in Paneth cells.

a Schematic model of stem cell maintenance by Paneth cells in ISC niche. The solid arrows indicate activation and the blunt-ended arrows represent inhibition. b Intracellular cADPR in the sorting Paneth cells using an ELISA kit. Amounts of cADPR were normalized to total protein (n = 3 biologically independent mice per group). c Endogenous cADPR levels in organoids treated with rapamycin, ALA, and MHY1485 were measured using an ELISA kit (n = 3 biologically independent mice per group). d–i Crypts isolated from old mice were cultured with rapamycin, MHY1485, cADPR and 8-Br-cADPR together with/without ALA. Representative images (scale bars, 250 μm) of mouse intestinal organoids (d), quantification of organoid amount (n = 7 biologically independent mice per group) (e), representative images (scale bars, 50 μm) of organoid buds (f), quantification of bud per organoid (n = 13 organoids/group, obtained from 7 biologically independent mice) (g), representative staining (scale bars, 50μm) of EdU cells (h), quantification of EdU+ cell amount in mouse intestinal organoids(i). (n = 10 organoids/group, obtained from 7 biologically independent mice). j Schematic models of ALA functions in Paneth cells to prevent ISC aging. Data are displayed as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used in (b, c, e, g, i). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Moreover, we observed that the addition of ALA, rapamycin, or cADPR individually, as well as the combined application of ALA with rapamycin or cADPR, significantly enhanced the generation of intestinal organoids (Fig. 7d, e), organoid buds (Fig. 7f, g), and increased the number of EdU+ cells (Fig. 7h, i) in old mouse intestinal organoids. However, activating mTOR via MHY1485 or blocking cADPR with 8-Br-cADPR counteracted the effects of ALA on the intestinal organoids of old mice (Fig. 7d–i). Additionally, following cADPR intervention in ISCs sorted from old mouse crypts, the proportion of mitochondria with compromised cristae integrity was significantly reduced in these ISCs (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b).

Notably, another study by Pentinmikko et al. reported that increased mTOR pathway activity in old Paneth cells promotes the secretion of Notum, ultimately leading to the inhibition of ISC function13. This study, along with our own, highlights the involvement of the mTOR pathway in aging Paneth cells, suggesting the necessity to investigate whether ALA also affects Notum secretion by inhibiting the mTOR pathway in old Paneth cells. Through the isolation of Paneth cells from organoids derived from different groups, we also found that Notum expression levels in old Paneth cells were significantly higher than those in young Paneth cells, and that ALA markedly reduced Notum expression in old Paneth cells (Supplementary Fig. 7c–e). These results suggest that ALA, by inhibiting the mTOR pathway in old Paneth cells, enhances ISC function through the promotion of cADPR secretion while concurrently reducing Notum secretion (Fig. 7j).

Discussion

The aging of ISCs serves as the pathophysiological foundation of many intestinal diseases. Consequently, inhibiting ISC aging is a critical strategy for enhancing intestinal homeostasis and decreasing the incidence of intestinal diseases among elderly populations. Using the Drosophila midgut as a drug screening platform, our previous studies identified several natural compounds, including ALA, taurine, caffeic acid, and quercetin, that can inhibit age-associated midgut degeneration in Drosophila7,40–42. However, whether these natural compounds can also inhibit human ISC aging remains unclear due to significant differences between Drosophila and mammals in their epithelial structures and cellular compositions9,10. In this study, we found that ALA synthesis was inhibited upon aging, leading to a decreased level of ALA in old human small intestines. Based on the intestinal organoids of humans and mice, as well as in vivo mouse experiments, we confirmed the effect of ALA supplementation on inhibiting ISC aging and promoting the regeneration of intestinal epithelia. Finally, we identified that the effect of ALA on inhibiting ISC aging was dependent on the suppression of mTOR pathway in old Paneth cells. Consequently, our research posits a prospective therapeutic approach for addressing age-associated intestinal diseases in humans.

One advantage of this study is our access to human small intestine samples. Despite sourcing jejunum tissues from gastric cancer patients, only those devoid of peritoneal seeding metastasis of tumor were chosen. Furthermore, during Roux-en-Y reconstruction, jejunum tissues were collected approximately 40 cm from Treitz’s ligament. Thus, we can consider these jejunum samples as normal tissues, given the negligible tumor influence. Our study confirms that aging can lead to decreased expression of ALA synthesis genes and decreased ALA content in human small intestines. In the human jejunum tissues, we observed significant decreases in the expression levels of LIAS and related genes, as well as ALA levels, in the jejunum of older patients. Concurrently, we developed intestinal organoids from human small intestinal crypts to provide a robust model for exploring human intestinal organogenesis and physiology16. We noted that organoids developed from old human intestinal crypts exhibited aging phenotypes, manifested as diminished organoid-forming capacity, reduced number of organoid buds, and decreased proliferative ISCs. These aging phenotypes were reversed upon ALA supplementation, suggesting that ALA can inhibit ISC aging and stimulate human intestinal epithelial regeneration. Furthermore, our in vivo experiments showed that ALA could augment the number of ISCs in the intestinal crypts of older mice and stimulate intestinal epithelial repair in old mice after indomethacin-induced damage. These data further corroborate the effects of ALA on inhibiting ISC aging in mammals. ALA is an important coenzyme factor for multiple enzymes in mitochondria, participating in mitochondrial aerobic metabolism and nucleic acid synthesis43. In addition, ALA exhibits several biological functions, such as antioxidation to eliminate oxygen free radicals, sugar and lipid metabolism regulation, inflammatory response inhibition, and cell apoptosis reduction17,44. Although we noted a decrease in endogenous ALA synthesis in old human small intestines, ALA is also naturally available in plant foods and meats17. Recent clinical trials have reported that oral ALA is beneficial in improving multiple diseases, such as neuropathic pain, migraines, and diabetic neuropathy, and the safety of oral ALA in humans is well-documented45–47. Taken together, the data from our study highlight the value of applying ALA to inhibit human ISC aging and promote small intestine homeostasis in elderly populations.

Another key finding of our study is that ALA attenuates ISC aging through a mechanism reliant on Paneth cells. We observed the accumulation of abnormal Paneth cells within old intestinal crypts and organoids, and this was ameliorated by ALA supplementation. Notably, we also observed a decline in the secretion of functional molecules (DEFA6, Reg3γ, and cADPR) from old Paneth cells, which ALA supplementation improved. These results indicate that morphological changes of lysozyme granules in Paneth cells correlate with their secretory function and support the mechanism by which ALA enhances ISC function through promoting the secretion of cADPR from old Paneth cells. Moreover, when co-cultured with old Paneth cells or CM from old intestinal organoids, young ISCs developed intestinal organoids exhibiting pronounced aging phenotypes. These observations suggest that the aging of the stem cell niche, particularly through Paneth cell dysfunction, is a critical factor in ISC aging.

Our work reveals that ALA suppresses the mTOR pathway in Paneth cells, rather than in ISCs, to increase cADPR secretion and reduce Notum secretion, which, in turn, enhances the functionality of aged ISCs. Previous studies have demonstrated the role of the mTOR pathway in regulating Paneth cell function, thereby influencing ISC homeostasis. Consistent with our findings, some studies have shown that inhibiting the mTOR pathway through caloric restriction or rapamycin administration promotes cADPR secretion in Paneth cells, subsequently improving ISC function39. In addition, another study reported that inhibiting mTOR activity in Paneth cells with rapamycin enhanced the intestinal regenerative capacity of old mice13. However, the impact of mTOR expression in ISCs on their functionality were controversial. D. He et al. reported heightened mTOR activation in mouse ISCs upon aging, which resulted in decreased proliferative capacity and diminished intestinal villi size and density3. Conversely, another study by M. Igarashi et al. demonstrated that calorie restriction suppressed mTOR signaling in Paneth cells, leading to increased SIRT1 activity and subsequent mTOR activation in neighboring ISCs, ultimately enhancing ISC proliferative abilities34. These findings suggest that the role of mTOR in ISCs may vary depending on the specific conditions, and the regulatory effects of Paneth cells on ISCs might potentially mask the true role of mTOR activity in ISCs.

Our study presents certain limitations that warrant further investigation. First, we utilized elesclomol, PF9366, or siLias to suppress ALA synthesis in mice and intestinal organoids, while the establishment of a Lias gene knockout mouse model was not achieved. Furthermore, it has been reported that heightened mTOR activation in ISCs of old mice could result in reduced proliferative capacity of ISCs. While our study found that p4E-BP1 and pS6 expression in od ISCs was not significantly decreased when treated with ALA. Accordingly, further investigation is necessary to elucidate the expression of the mTOR pathway in ISCs and the implications for ISC function regulation. Additionally, we need to clarify that ALA exhibits a wide range of biological functions. Although this study primarily reveals that the significant improvement of ALA in the proliferation of old ISCs is dependent on the involvement of Paneth cells. As for whether ALA has direct effects on other cellular functions of ISCs, further investigation is required in future studies. At last, we confirmed the effect of ALA on inhibiting ISC aging using human intestinal organoids, and clinical trials about the application of ALA in elderly populations are still needed to verify our results.

Methods

Ethical regulation statement

For human samples, the study protocol followed the ethical principles of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, in 2023 (Approval No. 20231885). All animal procedures complied with the approved protocol of the West China Hospital Animal Experiment Ethics Committee (Ethics License No. 20230426005).

Human subjects and small intestine tissue

Human jejunum tissues were obtained from 14 patients of gastric cancer undergoing Roux-en-Y reconstruction at West China Hospital, Sichuan University (detailed patient information provided in Supplementary Data 1). Exclusion criteria comprised peritoneal seeding metastasis of gastric cancer, a history of other malignant tumors, and a history of small intestinal disease. During the Roux-en-Y reconstruction, jejunum tissues were collected approximately 40 cm from the Treitz’s ligament. Subsequently, jejunum samples were fixed in 4% PFA and routinely embedded in paraffin. Furthermore, jejunum samples intended for organoid culture were transferred to ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored on ice until use. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study protocol adhered to the ethical principles of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Human Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, in 2023 (approval number 20231885).

Mice and drug treatment

The mouse strain used in this study, Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 (strain name: B6.129P2-Lgr5tm1 (cre/ERT2) Cle/J, stock number: 008875), was obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Additionally, C57BL/6 J female and male mice (6-8 weeks old and 15-22 months old) used in this research were purchased from GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China).

All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free (SPF) facilities at the Animal Experimental Center of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, and were supervised by the Experimental Animal Center following the Regulations of the Institutional Animal Care Committee (GB/T 35892-2018). The mice were housed under controlled conditions (22 ± 1 °C, 45–60% relative humidity) with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and had ad libitum access to standard chow (SPF-F02, SiPeiFu) until sacrifice. For the lipoic acid (ALA) feeding experiment, 15-month-old male C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into groups of 7 mice each. After a week of acclimatization to their respective diets, the mice were provided with drinking water containing 100 mg/kg/Day ALA for 3 months to achieve the full anti-aging effects of ALA48. The drinking water was replaced weekly, and ALA intake was measured daily. The concentration of ALA in the drinking water was adjusted to achieve a daily treatment dose of 100 mg/kg body weight. ALA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (T1395), dissolved in 2 mM NaOH solution, pH adjusted to 7.2 with 2 mM HCl, and made up to volume with ddH2O.

The indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury models were established using young (6-8 weeks old) and old (18-24 months old) C57BL/6 mice20. These mice were adapted to laboratory conditions for one week before the experiment and then randomly divided into the following 4 groups (n = 10 in each group): (1) Young mice were subcutaneously injected with 10 mg/kg indomethacin (Aladdin, I106885) and were fed with the control drinking vehicle dissolved in water. (2) Young mice were subcutaneously injected with 10 mg/kg indomethacin and were fed with drinking vehicle dissolved in water+100 mg/kg/Day ALA. (3) Old mice were subcutaneously injected with 10 mg/kg indomethacin and were fed with the control drinking vehicle dissolved in water. (4) Old mice were subcutaneously injected with 10 mg/kg indomethacin and were fed with drinking vehicle dissolved in water+100 mg/kg/Day ALA. Mice in each group were euthanized at 24 h and 7 days post-indomethacin injection for subsequent analysis.

For the inhibition of ALA synthesis, twelve C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were evenly and randomly divided into two groups. The experimental group of mice received intraperitoneal injections of 50 mg/kg elesclomol (MedChemExpress, STA-4783) every other day for 2 weeks. The control group received intraperitoneal injections of an equivalent volume of elesclomol solvent, specifically corn oil. All animal procedures complied with the approved protocol of the West China Hospital Animal Experiment Ethics Committee (Ethics License No. 20230426005).

Crypt isolation and mouse intestinal organoid culture

The procedure for isolating female and male mouse intestinal crypts was conducted in accordance with established protocols49. In brief, the mouse small intestine underwent a cold PBS flush, was longitudinally opened, and had mucus removed. The intestine was then sectioned into small fragments and immersed in a PBS solution containing 5 mM EDTA (Aladdin, B301167) on ice for a duration of 2 h. The small intestine fragments were transferred into a pipette with 10 ml of cold PBS, and the tissue fragments were then vigorously suspended to separate the intestinal crypts effectively. Subsequent to this step, the supernatant was passed through a 70 μm nylon mesh to concentrate the crypts. The resultant supernatant underwent centrifugation at 200g for 3 min to segregate crypts from individual cells. Then, the isolated crypts were seeded into a mixture of culture medium and Matrigel (Corning 356230, growth factor reduced) at a 1:1 ratio. Each droplet of the mixture, comprising 50 μl, accommodated 500 crypts, with an overlay of ENR culture medium. The culture medium consisted of Advanced DMEM/F12 (Gibco, 12634010), GlutaMAX™ (Gibco, 35050061), 10 mM Hepes (Gibco, 15630080), Β27 1X (Gibco, 17504044), N2 1x (Gibco, 17502001), 1 mM N-Acetyl-L-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, A7250), recombinant mouse Noggin (100 ng/ml; PeproTech, 250-38), recombinant mouse EGF (50 ng/ml; Peprotech 315-09), and recombinant human R-spondin1 (500 ng/ml; Cat# GMP-CX83; Novoprotein, Shanghai, China).

The organoids were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and saturated humidity in a CO2 incubator. Unless otherwise indicated in the figure legends, organoid formation rates were evaluated after 2 days of cultivation. Following an initial organoid culture period of 5-9 days, the quantity of buds per organoid was measured, and passaging was conducted. Passaging involved the mechanical dissociation of organoids into individual crypt fragments, which were subsequently plated onto fresh Matrigel at a 1:2 ratio.

The specified concentrations of the following drugs were added to the standard culture medium: ALA (100 μM, Sigma-Aldrich T1395), Elesclomol (10 μM, MedChemExpress STA-4783), PF9366 (0.5 μM, MedChemExpress 72882-78-1), Rapamycin (10 μM, Selleck AY-22989), MHY1485 (10 μM, Merck SML0810), cADPR (10 μM, Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-201512), 8-Br-cADPR (10 μM, Santa Cruz Biotechnology SC-201514), OSMI-1 (1 μM, MedChemExpress, HY-119738).

Human organoid culture

Following the aforementioned protocol, human jejunum crypts were isolated and subsequently embedded in Matrigel for cultivation utilizing the Human Intestinal Organoid Kit (bioGenous, K2002-HI). According to the instructions provided with the kit, primary cultures were maintained in human intestinal organoid expansion medium, while passaged cultures were maintained in human intestinal organoid maintenance medium supplemented with recombinant human insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) (100 ng/ml; Cat# C032; Novoprotein, Shanghai, China), recombinant human fibroblast growth factor (FGF) basic (FGF-2) (50 ng/ml; PeproTech, 100-18B)50. During passaging, the organoids were treated with ALA (Sigma-Aldrich T1395, 100 μM) and passaged weekly, maintaining cultivation for 3–4 weeks. During passaging, 5 mM EDTA was used to dissociate an equal number of organoids in each culture condition. After 5-7 days of cultivation, the counts of organoids and buds were recorded.

Flow cytometry and isolation of ISCs and Paneth cells

To isolate single cells, isolated crypts or mature organoids were dissociated at 37 °C using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco 25200072) supplemented with DNAse I (200 U/ml, Roche, 10104159001) for a duration of 40 min to isolate single cells20. After washing, cells were incubated with anti-CD24-PE antibody (Biosciences, 553262) in the absence of light at 4 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were labeled with fixable viability dye eFluor 780 (eBioscience, 65-0865) to distinguish living cells. Prior to cell sorting, samples were filtered through a 40-micron mesh filter (BD Falcon). Cell sorting was performed using the FACS Aria III sorter (BD Bioscience, USA). Isolated ISCs were identified as Lgr5-EGFPhi CD24low/-; while Paneth cells were characterized as CD24hi SideScatterhi Lgr5-EGFP-. Cell population analysis was conducted using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC).

Culture of isolated ISCs and Paneth cells

After sorting, ISCs and Paneth cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio, then centrifuged at 250g for 5 min. Then, 30 μl of Matrigel was pipetted into a 48-well plate (Corning 3548), with 2000–3000 cells seeded per 30 μl of Matrigel. The Matrigel containing ISCs and Paneth cells solidified in a 37 °C incubator for 20–30 min. Subsequently, Matrigel droplets were covered with 300 μl of organoid culture medium and cultured in a 37 °C, 5% CO2, fully humidified incubation environment. When culturing isolated ISCs and Paneth cells in ENR medium, supplementation included an additional 10 μM Jagged-1 peptide (Anaspec, AS-61298), 500 μg/ml of R-spondin-1 (final concentration 1 μg/ml), and 10% Afamin-Wnt-3A serum-free conditioned medium (MBL)39,51. Y-27632 at a concentration of 10 μM (ApexBio, A3008) was added to the medium for the initial three days. The culture medium was refreshed every alternate day. ALA was added on the first day of culturing sorted ISCs and Paneth cells. Unless otherwise indicated, organoid formation rate statistics were performed on day 3 of culture, and organoid budding statistics were assessed on day 8.

Collection of conditioned medium

The culture medium of young and aged intestinal organoids was harvested following a 5-day culture period29. The medium was then centrifuged at 1000g for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected as the conditioned medium. Prior to usage, the conditioned medium was supplemented with 50 ng/ml EGF (Peprotech, 315-09), 100 ng/ml noggin (Peprotech, 250-38), 1 μg/ml R-Spondin-1 (Cat# GMP-CX83 Novoprotein, Shanghai, China), 10 μM Jagged-1 peptide (Anaspec AS-61298), and 10% Afamin-Wnt-3A serum-free conditioned medium (MBL). Additionally, 10 μM Y-27632 (ApexBio, A3008) was added to the conditioned medium for the initial 3 days, and the conditioned medium was replaced every three days.

SiRNA-directed gene silencing

Two days before electroporation, mouse organoids were passaged and cultured in organoid medium. To promote the formation of cystic hyperproliferative crypts, the medium was supplemented with 10 µM CHIR99021 (HY-10182, MedChemExpress), 10 µM Y27632 (HY-10071, MedChemExpress), and 10 mM nicotinamide (N108087, Aladdin)52.

Mouse Lias siRNA was purchased from Tsingke Biological Technology (Hangzhou, China). The siRNA sequences were as follows: Lias siRNA sense strand, 5′-GCCGACGUGGACUGUUUAA-3′, and antisense strand, 5′-UUAAACAGUCCACGUCGGC-3′ (antisense). Details of the organoid transfection procedure were based on previously reported methods53.

Organoids were dissociated into single cells using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco 25200072) at 37 °C. The resulting single cells were resuspended in BTXpress electroporation buffer (BTX) along with the siRNA and subjected to electroporation using the Gene Pulser Xcell™ Total System (Bio-Rad, 1652660) under parameters optimized as described by Fujii et al.53. Following electroporation, the single cells were cultured in the ENR medium supplemented with 10 μM Jagged-1 peptide (Anaspec, AS-61298), 500 ng/mL R-spondin-1 (final concentration, 1 μg/mL), and 10% Afamin-Wnt-3A serum-free conditioned medium (MBL) to facilitate the generation of organoids.

Three days after electroporation, total RNA from edited organoids was extracted and then reversely transcribed into cDNA. Subsequently, qRT-PCR was performed to validate the knockdown efficiency.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry for intestinal tissues

The intestinal tissues were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde Fix Solution (PFA) (Servicebio, G1101), embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through a series of ethanol and water baths. For antigen retrieval, slides were heated in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min. Slides were blocked with 5% BSA solution for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies pre-diluted as follows: anti-rabbit Lysozyme (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, PA5-16668), anti-mouse phospho-S6 (1:400, Cell Signaling Technology, 62016), anti-rabbit LIAS (1:100, Proteintech, 11577-1-AP), anti-rabbit SOX9 (1:1000, Abways Technology, China, CY5400) and anti-mouse Olfm4 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, 39141).

After washing three times with 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST), the primary antibody was thoroughly rinsed. Subsequently, the slices were then incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI at room temperature for 2 h. The secondary antibodies and their dilutions were as follows: Goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 (1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Goat anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for nuclear staining. For specific lias staining, we employed an HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Rabbit (1:100, Beyotime, A0208) and DAB substrate kit (Beyotime, P0203) for signal detection. The nucleus is stained by hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich). The observation of samples was conducted under a Leica DMi8 optical microscope (Leica) equipped with Leica Application Suite X (3.7.0.20979). All acquired images were processed and analyzed using software such as Adobe Illustrator.

Immunofluorescence for organoids

The human and mouse intestinal organoids were first fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Beyotime, P0096). Fluorescent labeling was conducted with anti-rabbit Lysozyme (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, PA5-16668), anti-mouse phospho-S6 (1:400, Cell Signaling Technology, 62016S), anti-mouse Olfm4 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, 39141), anti-rabbit REG3G (1:50, Sangon Biotech, D122683), anti-rabbit DEFA6 (1:1000, Servicebio, GB114861) and anti-mouse GFP (1:1000, Abcam, ab1218) following overnight incubation at 4 °C. Goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 (1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and goat anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used as secondary antibodies. Nuclei were then stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Immunofluorescence images were captured using the Leica TCS-SP8 confocal microscope.

EdU assay

The assessment of organoid proliferation was performed using the EdU-647 Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (C0081S, Beyotime). Initially, 20 μM 5-ethynyl-2’deoxyuridine (EdU) was added to the culture medium, and the organoids were cultured for 2 h. Subsequently, the organoids were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After fixation, organoids were treated with 0.5% PBST to allow the reagent to penetrate the cells. Next, the organoids were co-incubated with 1× Click reaction solution for 30 min to label DNA containing EdU. After this, cell nuclei were stained with DAPI for 30 min to enable visualization.

To measure the proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells, EdU at 5 mg/kg was intraperitoneally injected into mice 2 h prior to killing. Intestines were collected and Edu positive cells were detected by the EdU-647 Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (C0081S, Beyotime).

Finally, the organoids and the tissue sections were observed under a Leica TCS-SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope, and the LAS X image processing software was employed for the analysis of EdU+ cell count, thereby evaluating the level of cell proliferation.

TUNEL and immunofluorescence co-staining assay

Cell death was detected using the TUNEL FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (A111-01, Vazyme Biotech) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, paraffin-embedded intestinal sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through a series of graded alcohols. Following antigen retrieval, the slides were incubated with 0.2% PBST for 10 min, followed by washing with PBS. The samples were then incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture in a humidified chamber at 37 °C for 60 min, protected from light. After this incubation, the samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-rabbit Lysozyme (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, PA5-16668) and stained with goat anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 h. Subsequently, DAPI Staining Solution (C1005, Beyotime) was used to stain the nuclei. Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Leica TCS-SP8 confocal microscope.

Histological analysis of the indomethacin-induced injury in small intestine

The intestinal tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for 12-24 h, followed by dehydration and embedding in paraffin. Subsequently, the sections underwent staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and the image acquisition was performed using the Leica DM6 B optical microscope. The histological assessment of small intestinal sections was evaluated based on established criteria54.

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry analysis

Chemical reagents

ALA, chromatography-grade acetonitrile (ACN), formic acid, and methanol are all sourced from Sigma-Aldrich.

Tissue sample preparation

The specific steps for ALA extraction were as follows: First, accurately weigh 200 mg of the intestinal sample, 50 mg of the organoids, 50 mg old intestinal stem cells, or 50 mg Paneth cells into a mortar, and grind the tissue using a liquid nitrogen grinding method7. Subsequently, introduce 800 µL of methanol solution to transfer the sample to a 1.5 mL EP tube, and rotate for 3 min at 1500g (4 °C). Following centrifugation, retrieve the supernatant. Proceed by placing the sample at −80 °C for 30 min, sonicating in an ice bath for 10 min, and centrifuging at 4 °C and 13,300g for 15 min. Transfer 700 µL of the supernatant to an EP tube. Finally, vacuum concentrate and dry the extraction solution. The extracted solution was then dissolved in 500 µL of acetonitrile solution, centrifuged at 4 °C and 13,300g, and 150 µL of the supernatant was taken for metabolite analysis. All samples were prepared in at least three independent biological replicates.

Calibration curves

Prepare ALA standard solutions with concentrations of 625, 1250, 2500, 5000, and 10,000 ng/ml. Inject 2 µL of the solution into the LC-ESI-MS/MS mass spectrometer (TripleTOFTM 5600 + , AB SCIEX, USA). Use the peak area of the standard solution (x-axis) against the concentration of the standard solution (y-axis) to create a standard curve. The linearity within the range of 625 to 10,000 ng/ml is excellent (r2 = 0.9926). The linear regression equation is Y = 0.04250*X + 132.8; r2 = 0.9926.

Determination of ALA

ALA mass spectrometry analysis was performed using a TripleTOF AB 5600+ high-resolution mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, USA) in the Research Center of Natural Resources of Chinese Medicinal Materials and Ethnic Medicine, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine. The system featured an electrospray ionization (ESI) ion source coupled with an LC-30A ultra-high-performance liquid chromatograph (Shimadzu, Japan). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Kinetex XB-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7μm) (Phenomenex, USA). The mobile phase comprised of 0.1% formic acid in water (Phase A) and acetonitrile (Phase B). The mobile phase gradient was set as follows: from 0 to 10 min, a linear gradient to 40% B; the flow rate was maintained at 0.25 mL/min, with the column temperature at 40 °C, and an injection volume of 2 µL.

Optimization of the mass spectrometry parameters included: ion spray voltage set to −4500 V; source temperature at 550°C; curtain gas at 30 psi; nebulizer gas (GS1) at 50 psi; heater gas (GS2) at 50 psi; de-clustering potential (DP) at −80 V; capillary temperature at 320°C; ion source heater at 300 °C; source voltage at 3.6 kV; sheath gas (N2) at 35 arbitrary units; auxiliary gas at 10 arbitrary units; sweep gas flow at 0 arbitrary units; S-Lens RF level at 60%; collision energy (CE) at −30 eV; and collision energy spread (CES) at 20 eV. Data collection was facilitated using AB Analyst TF Software (AB SCIEX, Framingham, USA). The experiments were conducted in negative ion mode, scanning from m/z 100 to 2000.

Transmission electron microscopy

Mouse small intestine tissues were freshly collected immediately after sacrifice, washed gently with pre-cooled PBS, and cut into small fragments. The tissue fragments were promptly fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight for TEM analysis.

As described above, senescent intestinal stem cells were sorted and cultured. cADPR (10 μM, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-201512) was added four days prior to Paneth cell development. Organoids lacking Paneth cells were then collected for transmission electron microscopy analysis.

The Matrigel containing growing organoids and the small intestine were first fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde, followed by post-fixation with 1% osmium tetroxide. Subsequently, the samples underwent gradual dehydration in acetone and were infiltrated with a mixture of dehydrating agent and epoxy resin (Epon812) in ratios of 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3, with each step lasting 30 to 60 min. The infiltrated samples were then placed in appropriate molds, embedded in an embedding medium, and polymerized by heat to form solid matrices, known as embedding blocks. Next, ultrathin sections approximately 50 nanometers thick were cut from the embedding blocks, stained initially with uranyl acetate for 10 to 15 min, followed by lead citrate staining for 1 to 2 min, all conducted at room temperature. Finally, observation was performed using a JEM-1400PLUS transmission electron microscope.

Moreover, we manually assessed cristae density of individual mitochondria within each image. The mitochondria were categorized into three groups: mitochondria with cristae of normal appearance filled (cristae density approximately 50– 100%); mitochondria with a loss of cristae density exceeding 50% (cristae density approximately 0–50%); mitochondria with a cristae density of 0. All quantifications were performed without knowing the sample identifications22,55.

Morphologic analysis of Paneth cells

Tissue sections from the proximal margins of each excised tissue were evaluated by pathologists, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Only sections containing a minimum of 100 well-preserved crypts and no significant inflammation were utilized for Paneth cell analysis. Pathologists performed a blind evaluation of distinct Paneth cell characteristics. Paneth cells located within Peyer’s patches were not included in the analysis.

The quantification method for lysozyme distribution remains consistent with the previously described approach21,22. The Paneth cell of human was categorized as either normal (D0) or one of five abnormal types, including: disordered (D1, abnormal granule distribution and size), diminished (D2, ≤10 granules), diffuse (D3, presence of lysozyme or defensin in cytoplasmic smears but no identifiable granules), excluded (D4, most granules lack stainable material), and enlarged (D5, rare, mega granules). While in mice, the granule morphology of lysozyme in Paneth cells can be categorized into normal (D0) and 3 abnormal categories (D1: disordered; D2: depleted; D3: diffuse).

Western blotting analyses