Abstract

Renal stones (RS) are common urologic condition with unclear pathogenesis. Role of aging-related differentially expressed genes (ARDEGs) in RS remains poorly understood. This study aims to identify potential aging-related biomarkers for RS, explore the functions of aging-associated genes, and investigate the immunological microenvironment in RS. ARDEGs were collected from the GEO, GeneCards, and Molecular Signatures databases. The roles of ARDEGs were analyzed using Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. Key genes were identified using machine learning methods. Immune infiltration in RS was assessed using the CIBERSORT and ssGSEA algorithms. A total of 22 ARDEGs were identified through analysis, including 9 up-regulated and 13 down-regulated genes. GO enrichment analysis revealed that these genes were mainly involved in RS-related biological processes such as macrophage proliferation and neuroinflammatory response. GSEA analysis showed that RS-associated genes were predominantly involved in immune regulation-related pathways. Using logistic regression, SVM, and LASSO regression algorithms, a successful early-diagnosis model for RS was developed, yielding 7 key genes: CNR1, KIT, HTR2A, DES, IL33, UCP2, and PPT1. Immunocyte infiltration analysis of RS samples showed that CD8 + T cells had the strongest positive correlation with M1 macrophages, while resting NK cells had the strongest negative correlation with activated NK cells. The DES gene showed the strongest positive correlation with resting mast cells, and the IL33 gene displayed the highest negative correlation with regulatory T cells. Bioinformatics analysis screened out 7 new potential markers for RS and explored the possible mechanism of RS senescence. These findings provide novel insights into the relationship between RS and senescence, as well as the diagnosis and treatment of RS, and enhance our understanding of the disease’s occurrence and development mechanisms.

Keywords: Renal Stone, Immune Infiltration, Integrated Bioinformatics, Biomarkers

Subject terms: Immunology, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Data mining, Genome informatics

Introduction

Renal stones (RS), also known as urolithiasis, are mineral deposits that can form in the kidneys, ranging from asymptomatic incidental findings to painful recurrent disorders with substantial morbidity. Clinically, they may be characterized by symptoms such as pain, hematuria, and back pain. They are classified based on their composition into mutually exclusive categories such as calcium oxalate monohydrate, calcium oxalate dihydrate, uric acid, cystine, and others, and represent a significant and increasingly prevalent urological disorder worldwide1. Its pathogenesis is yet to be clarified, and about 10–15% of the global population suffers from this disease, with the incidence of the disease The incidence of renal stones is on the rise2. Although there has been significant progress in renal stone treatment, such as extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, and flexible ureteroscopic lithotripsy3 , renal stones still have a high recurrence rate4.

In addition, stone formation induces other renal and vascular diseases, posing a significant threat to human health5. Currently, patients are usually diagnosed after the onset of symptoms or incidentally during imaging studies2. Current renal stone risk prediction tools mainly focus on RS recurrence, with limited tools available for stone formers in the general population6.

Renal stones are more common in elderly populations than in younger populations7. Aging of the individual has multiple effects on renal stone formation. First, in terms of metabolism, the body’s metabolic function gradually decreases with age, leading to significant changes in urine composition. For example, citrate, oxalate, and total volume of urine are positively correlated with age, but the urinary pH, excretion of calcium, oxalate, and citrate, and relative saturation ratios of calcium oxalate decrease as a result of declining renal function8. In addition, older adults are more prone to metabolic abnormalities, such as hypercalcemia and hyperuricemia, which increase the amount of stone-forming substances in the urine, and the risk of stone formation The risk of stone formation is also elevated9–11. Second, immune dysfunction is also one of the important factors influencing renal stone formation during aging. Studies have shown that the function of macrophages is significantly affected during aging, including a decrease in their phagocytic ability12. This weakening of function may lead to a decrease in the body’s ability to remove stone particles, for example, which further promotes the development of stones13. Finally, the increased production of reactive oxygen species(ROS) in the body during aging leads to a rise in the level of oxidative stress, which damages renal tubular cells and thus affects the normal excretion of stone-forming substances in the urine, providing a favorable microenvironment for stone formation13,14. Therefore, assessing the involvement of aging-related genes in RS and immunity can help to elucidate the mechanistic roles of aging traits in the progression of RS, and to explore new biomarkers for prediction and diagnosis.

This study aimed to identify senescence-associated biomarkers in RS through bioinformatics approaches and to explore the roles and mechanisms of senescence-associated genes and the immune microenvironment. We screened Aging-related differentially expressed genes (ARDEGs) in RS using the limma test and three machine learning algorithms and predicted potential miRNAs and TFs using online databases. The immune infiltration characteristics of RS and its correlation with ARDEGs were investigated using GESA analysis, which provided a new direction for early identification and treatment of RS.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of data

RS—associated datasets GSE73680 and GSE11751815,16 were obtained on the GEO collection via the R program GEOquery17. The samples of data set GSE73680 and GSE117518 are all from Homo sapiens, and the tissue source is Randall’s Plaque Tissue. The chip platform of GSE73680 is GPL17077, and the chip platform of GSE117518 is GPL21827. See Table 1 for details. Of these datasets, GSE73680 contains 29 RS samples and 33 control samples. Need to point out is that, GSE117518 has a small sample size (n = 6, including 3 RS samples and 3 normal samples), this limitation may affect the statistical power of the analysis and the generalizability of the results, and this issue has been fully considered in the subsequent analysis and discussion of this study. Aging—related Genes (ARGs) were acquired from the GeneCards18and Molecular Signatures (MSigDB) 19databases. GeneCards database offers detailed information on the human genome. We conducted a search using “Aging” as the keyword and applied a filter that limited the results to protein—coding ARGs with a relevance score higher than 10. The final dataset included 428 ARGs in total. Similarly, the DEMAGALHAES AGING DN gene set and DEMAGALHAES AGING UP gene set contain 70 ARGs, which were identified by scanning the MSigDB database using the keyword “Aging”. Eventually, 492 ARGs were included after merging and removing duplicates.

Table 1.

GEO Microarray chip details.

| GSE73680 | GSE117518 | |

|---|---|---|

| Platform | GPL17077 | GPL21827 |

| Species | Homo sapiens | Homo sapiens |

| Tissue | Randall’s Plaque Tissues | Randall’s Plaque Tissue |

| Samples in the RS group | 29 | 3 |

| Samples in the Normal group | 33 | 3 |

| Reference |

PMID:27297950 PMID:27731368 |

/ |

GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus.

To facilitate the integration of the datasets, the R package sva20 was employed to remove batch effects between GSE73680 and GSE117518. This process resulted in an integrated GEO dataset comprising 36 RS and 32 control samples. Subsequently, the dataset and annotation probes were standardized and normalized using the R package limma21.

Differentially expressed genes linked to renal stone aging

Based on the GEO dataset, the samples were divided into two groups: the RS group and the control group. Genetic variations between the RS and control groups were examined using the R tool limma. The criteria for identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are |logFC|> 0.00 and p—value < 0.05. Genes with logFC > 0.00 and p—value < 0.05 are considered up—regulated DEGs. Conversely, genes with logFC < 0.00 and p—value < 0.05 are considered down—regulated DEGs.

To identify RS—associated ARDEGs, the integrated GEO dataset was combined with genes obtained from differential analysis. ARDEGs were identified by intersecting ARGs with DEGs using the criteria of |logFC|> 0.00 and p—value < 0.05, and the results were visualized through a Venn diagram. The differential analysis results were presented using R—package ggplot2 to draw volcano and difference sorting maps, and R—package pheatmap to generate a heatmap of ARDEGs’ expression values.

GO enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO)22 is a widely adopted approach for conducting extensive functional enrichment analyses, covering biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC). We performed GO enrichment analysis on ARDEGs using the R package clusterProfiler23. An adjusted p—value < 0.05 and an FDR < 0.25 were considered highly significant. The p—values were adjusted using the Benjamini—Hochberg method.

Gene set enrichment analysis

In gene tables ranked by phenotypic correlation, GSEA24 assessed the distribution tendency of genes in predefined gene sets to determine their impact on phenotypes. Genes from the combined GEO dataset were categorized into the RS group and the control group by using phenotypic correlation ranking. Following that, all genes from the combined GEO dataset underwent GSEA utilizing the R program clusterProfiler. The GSEA criteria consisted of an initial value of 2020, a minimal requirement of 10 genes per genome set, and a maximum limit of 500 genes per genome set. The gene dataset c2.cp.all.v2022.1.Hs.symbols.gmt from MSigDB was used for GSEA. P—values were adjusted using the Benjamini—Hochberg method, and the screening criteria were set as an adjusted p—value < 0.05 and an FDR < 0.25.

Similarly, utilizing the R package clusterProfiler, GSEA was executed on every gene in the RS samples with the following parameters: seed = 2020, with a maximum of 500 genes per set and a starting point of 10 genes per set.

Establishment of a diagnostic model for renal calculi

To derive RS diagnostic models from the integrated GEO dataset, logistic regression analysis was performed on ARDEGs. In situations where the dependent variable, specifically the RS group and the control group, was dichotomous, logistic regression was utilized to investigate the connection between the independent and dependent variables more thoroughly. ARDEGs were filtered with p—value < 0.05 as standard. By constructing a logistic regression model and subsequently employing a forest plot, the molecular structure of ARDEGs inside the logistic regression framework can be visually represented.

Afterward, the SVM25 (Support Vector Machine) model is built according to ARDEGs comprised in the Logistic regression model, and ARDEGs are chosen by several genes with the maximum precision rate and the smallest mistake rate. Then, LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression assessment is carried out on ARDEGs contained in the SVM model through R package glmnet26 with set. Seed (500) as a parameter. This analysis mitigates model over-fit and enhances its generalization capacity by introducing a regularization word (lambda × pure slope value) depending on regression analysis of linearity. LASSO regression analysis yields its conclusions via diagnosis model diagrams and parameter locus charts. The results of the LASSO regression analysis results are the RS diagnostic model, which contains ARDEGs as key genes.

Verification of diagnostic model for renal calculi

Nomogram27, which is represented graphically by a collection of non-intersecting line segments, illustrates the functional association between various distinct variables in a rectangular plane coordinate system. According to the results of Logistic regression analysis, nomogram graphs created by the R package rms show the connections among key genes. The reliability and resolution of the RS diagnosis framework, obtained from outcomes of LASSO regression analysis, were evaluated by generating a Calibration Curve by Calibration Analysis. Decision Curve Analysis28 (DCA) was plotted utilizing R-pack ggDCA on the integrated GEO dataset, focusing on important genes. DCA is an easy approach for assessing clinical prognostic models, diagnostic procedures, and molecular indicators. Next, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve corresponding to the incorporated GEO dataset was produced with the R-pack pROC. The symptomatic efficacy of the Risk Score expression in forecasting the incidence regarding RS was evaluated by computing the area under the curve (AUC). The risk score is calculated as follows:

|

In addition, RS samples were classed as high- or low-risk based on the RS diagnostic model’s moderate risk score. We created group comparison graphs based on gene expression levels to better investigate the variations in the vital genes’ expression levels among RS samples between the low- and high-risk categories. Finally, ROC curves for key genes were produced by applying R-packet pROC. The indicative effectiveness of essential gene expression levels for anticipating the onset of RS was assessed by calculating the area under the ROC curve. The area under the ROC curve typically falls between 0.5 and 1. A more accurate diagnosis is one where the AUC is nearer 1. An AUC value between 0.5 and 0.7 indicates poor accuracy, a value between 0.7 and 0.9 recommends middling accuracy, and a value over 0.9 denotes outstanding precision.

Difference analysis of high- and low-risk groups for renal stones

Given the median risk score of the RS diagnostic model, RS groups were classified into high-risk groups and low-risk groups. Differences in genes between RS and control groups were analyzed using the R tool limma21. Genes with |logFC|> 0.25 and p—value < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Among them, genes with logFC > 0.25 and p—value < 0.05 were up-regulated DEGs, and genes with logFC < -0.25 and p—value < 0.05 were down-regulated DEGs. The results of this comparative study were visualized by R-package ggplot2 volcano map and R-pack heatmap to display the expression capacities of vital genes among ARDEGs.

Regulatory network construction

miRNA plays a pivotal regulatory role in biological development and evolution, modulating numerous target genes. Multiple miRNAs can also regulate the same target gene. To analyze the relationship between key genes and miRNAs, miRNAs associated with the key genes were retrieved from the TarBase database and miRDB database29,30. Furthermore, the regulatory networks between the key genes and miRNAs were obtained. The regulatory structure of mRNA and miRNA was visualized using the Cytoscape software (version 3.9.1)31.

Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression is accomplished through the interaction of transcription factors (TFs) with target genes (mRNAs). Acquired from the ChIPBase database and htftarget database32,33, transcription factors were united in analyzing the regulatory effects of transcription factors on key genes. Cytoscape software (version 3.9.1) was utilized to exhibit the mRNA-TF Regulatory Network.

Immunoinfiltration analysis of integrated datasets

CIBERSORT34, an algorithm rooted in the principles of linear vector support regression, assesses the composition as well as the number of immunity cells in heterogeneous cellular populations by deconvoluting transcript expression matrices. It was implemented to calculate the matrix of immune cell infiltration based on the integrated GEO data set along with the LM22 gene matrix. To achieve precise outcomes for the immune cell infiltration matrix, we excluded data points with immune cell enrichment percentages over zero. The correlation heat map was drawn by R package heat map to present the correlation between CIBERSORT immunological cells and between key genes and immune cells.

ssGSEA35 (Single-Sample Gene-Set Enrichment Analysis) algorithm is used to make highly sensitive and specific distinctions between various human immunological cell phenotypes in the tumor immune microenvironment. The algorithm obtained 24 gene sets to classify various types of immunological cells that infiltrate tumors from the published tumor immune infiltration articles36, which contained a variety of mankind’s immunity cellular subtypes, such as regulatory T lymphocytes, CD8 positive T cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. The enrichment score of the GEO dataset was utilized as a representative indicator to assess the level of immunological cell infiltration in each sample. This score was generated using ssGSEA analysis in the R-pack GSVA. To demonstrate the relevance between ssGSEA and immunological cells, as well as the association between important genes and immunological cells, the correlation heat map was drawn by R-package pheatmap. A correlation coefficient with an absolute value below 0.3 indicates a weak or no association, 0.3 to 0.5 is weak, 0.5 to 0.8 is moderate, and over 0.8 is substantial.

Immunoinfiltration analysis of disease groups

The CIBERSORT34 was employed to calculate the immunological cell infiltration matrix based on the RS group, combining the LM22 characteristic gene matrix. Filter the data whose enrichment fraction of immune cells is over zero, and finally get the concrete outcome from the immunological cellular infiltration matrix. The correlation heat map was drawn by R package heat map to show the findings of the correlation investigation conducted on CIBERSORT immunological cells, as well as the correlations between pivotal genes and immunological cells.

The ssGSEA35 algorithm obtained 24 gene sets for labeling different tumor-infiltrating immune cell types from the published articles. The gene group comprises several subtypes of human immune cells, including CD8 positive T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and regulator T cells. Enrichment scores for renal stones calculated by ssGSEA in R-pack GSVA were applied to indicate the infiltrating level in each immune cell type of every sample. The correlation heat map was drawn by R-pack pheatmap to show the relevance between ssGSEA immune cells and between key genes and immune cells. A correlation coefficient with an absolute value below 0.3 indicates a weak or no association, 0.3 to 0.5 is weak, 0.5 to 0.8 is moderate, and over 0.8 is substantial.

Analysis of statistics

All data processing and analysis in this study were performed using R software (Version 4.2.2). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Intergroup comparisons were conducted using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test (Wilcoxon rank—sum test). Unless specified, results are based on Spearman correlation analysis for calculating correlations between different molecules, with p—value < 0.05 indicating significant differences.

Results

Technical route

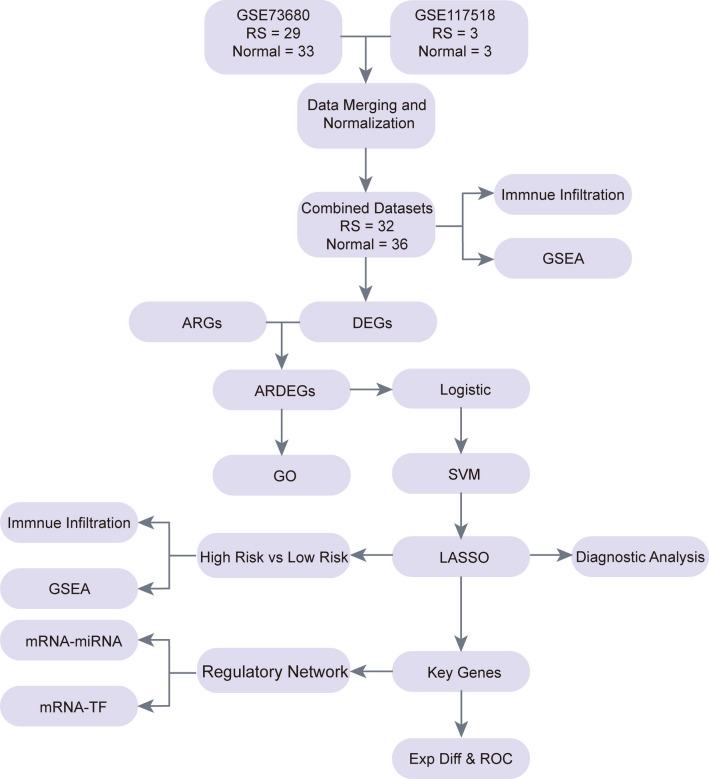

The technical route of this study is graphically illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

ARDEGs Comprehensive Analysis Flow Chart.

Pooling of renal stone datasets

Initially, the R package sva was implemented to process the renal stone (RS) datasets GSE73680 and GSE117518, removing batch effects and yielding an integrated GEO dataset. Subsequently, the datasets were compared before and after batch effect elimination using distribution box plots and principal component analysis (PCA) plots (Figs. 2A–D). Batch removal effectively eliminated batch effects in RS dataset samples, as evidenced by boxplot and PCA map results.

Fig. 2.

Batch Effects Removal of GSE73680 and GSE117518. (A) Boxplot of distribution of GEO data sets before batch consolidation. (B) Boxplot of the distribution of the integrated GEO dataset after batch removal. (C) 2D PCA plot of data set before batch processing. (D) 2D PCA plot of the debauched integrated GEO dataset. PCA, Principal Component Analysis; DEGs, Differentially Expressed Genes. Light purple represents the RS dataset GSE73680, and light blue represents the RS dataset GSE117518.

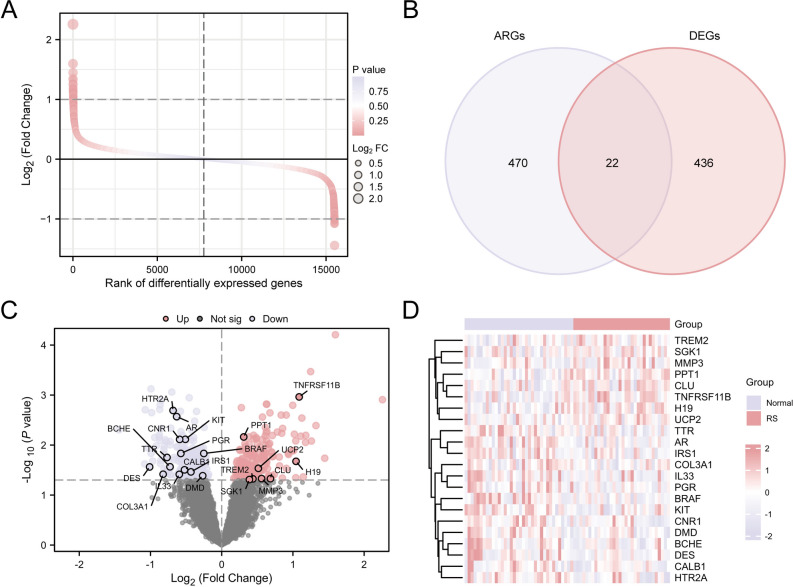

Analysis of differentially expressed genes associated with renal stone-related aging

The GEO dataset was examined using the R tool limma to find genes that exhibited differential expression between the two data sets. The results showed that under the criteria of |logFC|> 0.00 and p-value < 0.05, 211 genes were upregulated and 247 genes were down-regulated. According to the discoveries of this data set’s contrast analysis, the difference ranking diagram (Fig. 3A) and volcano diagram (Fig. 3C) were drawn. To identify ARDEGs, select genes with a logFC > 0.00 and a p—value < 0.05. This process identified a total of 22 ARDEGs. See Table S1 for details. A Venn diagram (Fig. 3B) was then created, which were CLU, SGK1, IL33, COL3A1, CALB1, H19, BRAF, AR, TTR, KIT, DMD, PPT1, PGR, HTR2A, CN R1, BCHE, TNFRSF11B, UCP2, TREM2, DES, MMP3, IRS1. After obtaining the intersection findings, we investigated the differences in ARDEG expression across various samples in the merged GEO dataset, which included RS and control groups. To illustrate the results, the R package pheatmap was implemented to create heat maps (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Differential Gene Expression Analysis for Combined Datasets. Figures A, B, C, and D are based on the comprehensive GEO dataset. (A) Chromosome sequencing map of genes that are expressed differently between the RS group and the control group. (B) Venn map of DEGs and ARGs. (C) Volcano plot of the variances in gene expression between RS and control groups. (D) Heat map of expression values of ARDEGs. DEGs, Differentially Expressed Genes; ARGs, Aging-Related Genes; ARDEGs, Aging-Related Differentially Expressed Genes. Light purple stands for the normal group, and light pink for the RS group.

GO enrichment analysis

The relationships between BP, CC, MF, and RS of 22 ARDEGs were further investigated by GO enrichment analysis combined with logFC analysis. These 22 ARDEGs were used for GO enrichment analysis, and the exact data are presented in Table 2. The results indicated that 22 ARDEGs were found to be mainly associated with biological functions like learning or memory, recognition, macrophage proliferation, memory, neuroinflammatory response, membrane raft, membrane microdomain, plasma membrane craft, presynapse, an integral component of the presynaptic membrane, amyloid-beta binding, steroid binding, glycoprotein in binding, transcription activator binding, SH2 domain binding, etc. (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the GO enrichment study for logFC was displayed by bubble plot (Fig. 4B), string plot (Fig. 4C), and circle plot (Fig. 4D). The circle plot (Fig. 4D) results showed that learning or memory and recognition were biological processes with significant down-regulation.

Table 2.

Result of GO Enrichment Analysis for ARDEGs.

| ONTOLOGY | ID | GeneRatio | BgRatio | pvalue | p.adjust | qvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | GO:0007611 | 8/22 | 264/18,800 | 3.67E-10 | 5.41E-07 | 2.63E-07 |

| BP | GO:0050890 | 8/22 | 306/18,800 | 1.18E-09 | 8.69E-07 | 4.23E-07 |

| BP | GO:0061517 | 3/22 | 12/18,800 | 3.04E-07 | 0.000112 | 5.45E-05 |

| BP | GO:0007613 | 5/22 | 122/18,800 | 2.55E-07 | 0.000112 | 5.45E-05 |

| BP | GO:0150076 | 4/22 | 73/18,800 | 1.45E-06 | 0.000428 | 0.000208 |

| CC | GO:0045121 | 6/21 | 326/19,594 | 8.9E-07 | 4.9E-05 | 2.39E-05 |

| CC | GO:0098857 | 6/21 | 327/19,594 | 9.07E-07 | 4.9E-05 | 2.39E-05 |

| CC | GO:0044853 | 3/21 | 113/19,594 | 0.00023 | 0.00829 | 0.00404 |

| CC | GO:0098793 | 4/21 | 492/19,594 | 0.001674 | 0.041404 | 0.020177 |

| CC | GO:0099056 | 2/21 | 67/19,594 | 0.002319 | 0.041404 | 0.020177 |

| MF | GO:0001540 | 3/21 | 81/18,410 | 0.000103 | 0.012425 | 0.006996 |

| MF | GO:0005496 | 3/21 | 100/18,410 | 0.000193 | 0.012425 | 0.006996 |

| MF | GO:0051861 | 2/21 | 29/18,410 | 0.000494 | 0.021237 | 0.011957 |

| MF | GO:0001223 | 2/21 | 40/18,410 | 0.000942 | 0.025524 | 0.014371 |

| MF | GO:0042169 | 2/21 | 41/18,410 | 0.000989 | 0.025524 | 0.014371 |

Fig. 4.

GO Enrichment Analysis for ARDEGs. (A) ARDEGs GO Enrichment Outcomes Bar Chart. (B) Bubble plot of GO enrichment results for ARDEGs. (C) Chord plot of GO enrichment study for ARDEGs. (D) GO Enrichment Results Circle Plot for ARDEGs. The pink dots inside the circle (D) indicate genes that are up-regulated (logFC > 0.00), whereas the purple dots reflect genes that are down-regulated (logFC < 0.00). ARDEGs, Aging-Related Differentially Expressed Genes; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, Biological Process; CC, Cellular Component; MF, Molecular Function. The screening criteria for GO enrichment analysis are adj. p—value < 0.05 and FDR < 0.25.

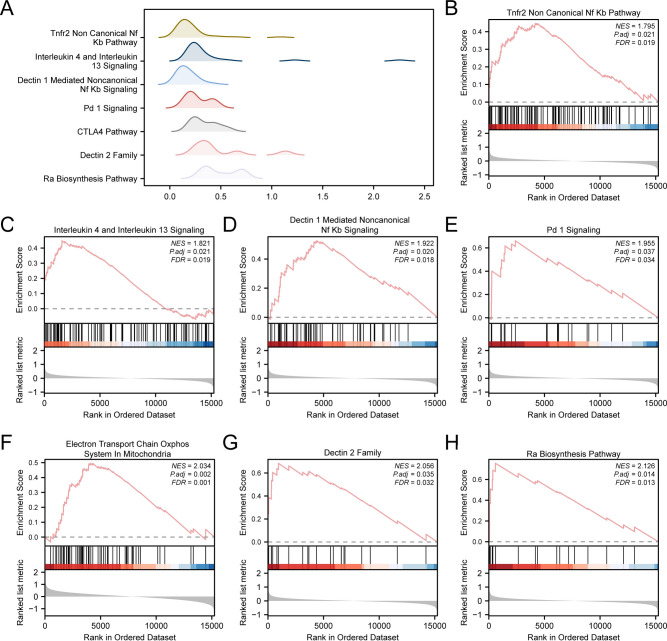

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

To explore the link between gene expression in the integrated GEO dataset and its impact on RS, GSEA was conducted to investigate the involved bioprocesses, affected cellular components, and molecular functions (Fig. 5A). Specific results are provided in Table 3. The results demonstrated that all genes within the integrated GEO dataset showed significant enrichment in Tnfr2 Non-Canonical Nf Kb Pathway (Fig. 5B), Interleukin 4 and Interleukin 13 Signaling (Fig. 5C), Dectin 1 Mediated Noncanonical Nf Kb Signaling (Fig. 5D), Pd 1 Signaling (Fig. 5E), Electron Transport Chain Oxphos System in Mitochondria (Fig. 5F), Dectin 2 Family (Fig. 5G), Ra Biosynthesis Pathway (Fig. 5H), etc.

Fig. 5.

GSEA for Combined Datasets. (A) GSEA7 biological function mountain map presentation of the integrated GEO dataset. (B–H) GSEA showed that RS was significantly enriched in Tnfr2 Non-Canonical Nf Kb Pathway (B), Interleukin 4 and Interleukin 13 Signaling(C), Dectin 1 Mediated Noncanonical Nf Kb Signaling, (D) Pd 1 Signaling, (E) Electron Transport Chain Oxphos System in Mitochondria (F), Dectin 2 Family (G) and Ra Biosynthesis Pathway (H). GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. GSEA screening criteria: adj. p < 0.05 and FDR < 0.25.

Table 3.

GSEA Results for Consolidated Datasets.

| ID | Set Size | Enrichment Score | NES | pvalue | p.adjust | qvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REACTOME_FORMATION_OF_THE_CORNIFIED_ENVELOPE | 115 | 0.629731 | 2.618102 | 1E-10 | 2.4E-07 | 2.21E-07 |

| REACTOME_KERATINIZATION | 194 | 0.491134 | 2.195758 | 3.49E-10 | 3.05E-07 | 2.81E-07 |

| REACTOME_RA_BIOSYNTHESIS_PATHWAY | 17 | 0.755865 | 2.126093 | 0.000138 | 0.0139 | 0.012802 |

| BIOCARTA_SPPA_PATHWAY | 16 | 0.757119 | 2.101562 | 0.000235 | 0.019669 | 0.018115 |

| REACTOME_DECTIN_2_FAMILY | 22 | 0.683914 | 2.055509 | 0.000666 | 0.034751 | 0.032005 |

| REACTOME_DEFECTIVE_GALNT3_CAUSES_HFTC | 13 | 0.761368 | 2.002444 | 0.000589 | 0.032655 | 0.030076 |

| REACTOME_ANTIMICROBIAL_PEPTIDES | 79 | 0.507088 | 1.984135 | 4.1E-05 | 0.00547 | 0.005038 |

| BIOCARTA_CTLA4_PATHWAY | 19 | 0.684456 | 1.980477 | 0.00105 | 0.045655 | 0.042048 |

| REACTOME_INTERFERON_ALPHA_BETA_SIGNALING | 63 | 0.524382 | 1.972349 | 6.04E-05 | 0.007509 | 0.006916 |

| REACTOME_AMINO_ACID_TRANSPORT_ACROSS_THE_PLASMA_MEMBRANE | 28 | 0.611807 | 1.963308 | 0.00076 | 0.037997 | 0.034995 |

| REACTOME_PD_1_SIGNALING | 21 | 0.661742 | 1.955456 | 0.000716 | 0.036527 | 0.033641 |

| WP_PROSTAGLANDIN_SYNTHESIS_AND_REGULATION | 44 | 0.560637 | 1.94856 | 0.00048 | 0.028678 | 0.026412 |

| WP_TYPE_I_INTERFERON_INDUCTION_AND_SIGNALING_DURING_SARSCOV2_INFECTION | 28 | 0.606882 | 1.947503 | 0.000954 | 0.042616 | 0.039249 |

| REACTOME_DECTIN_1_MEDIATED_NONCANONICAL_NF_KB_SIGNALING | 56 | 0.526009 | 1.921981 | 0.000227 | 0.019669 | 0.018115 |

| REACTOME_INTERFERON_GAMMA_SIGNALING | 78 | 0.490313 | 1.910749 | 0.000138 | 0.0139 | 0.012802 |

| WP_PROTEASOME_DEGRADATION | 54 | 0.522199 | 1.892503 | 0.000439 | 0.026996 | 0.024864 |

| REACTOME_ANTIGEN_PROCESSING_CROSS_PRESENTATION | 94 | 0.464328 | 1.865577 | 0.000102 | 0.011638 | 0.010719 |

| REACTOME_SIGNALING_BY_THE_B_CELL_RECEPTOR_BCR | 98 | 0.45224 | 1.835343 | 0.000256 | 0.019669 | 0.018115 |

| REACTOME_INTERLEUKIN_4_AND_INTERLEUKIN_13_SIGNALING | 98 | 0.448715 | 1.82104 | 0.000308 | 0.020965 | 0.019309 |

| REACTOME_TNFR2_NON_CANONICAL_NF_KB_PATHWAY | 94 | 0.446723 | 1.794842 | 0.000309 | 0.020965 | 0.019309 |

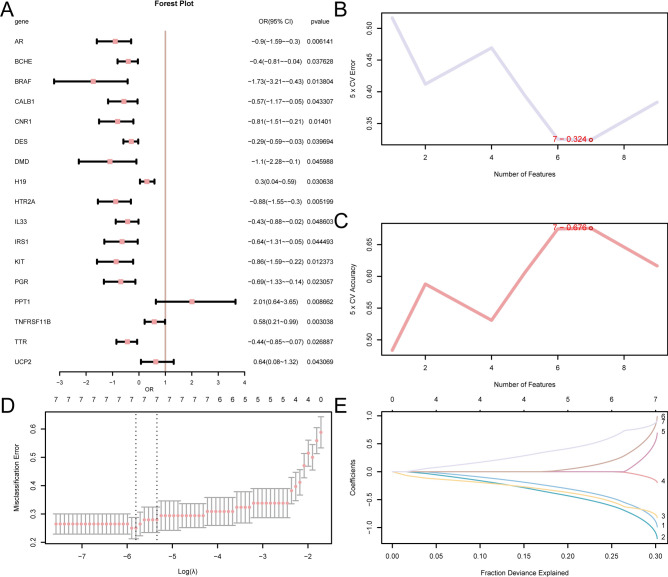

Construction of a diagnosis model of renal calculi

Initially, the diagnostic value of 22 ARDEGs in RS was assessed using Logistic regression. Subsequently, Logistic regression models were constructed and visualized by forest plots (Fig. 6A). The results indicated that 17 ARDEGs were statistically significant (p-value 0.05) in the Logistic regression model, they were AR, BCHE, BRAF, CALB1, CNR1, DES, DMD, H19, HTR2A, IL33, I RS1, KIT, PGR, PPT1, TNFRSF11B, TTR, and UCP2. An SVM model was then established based on these 17 ARDEGs and the SVM technique, achieving the lowest error rate (Fig. 6B) and highest precision (Fig. 6C) among the selected genes. When the number of genes was reduced to seven — CNR1, KIT, HTR2A, DES, IL33, UCP2, and PPT1— the SVM model exhibited the highest precision. Subsequently, based on the seven ARDEGs from the SVM models, LASSO regression analysis was conducted to construct the LASSO regression model and RS diagnosis model. The results were visualized using regression model plots (Fig. 6D) and variable trajectory plots (Fig. 6E). The LASSO regression model incorporated seven ARDEGs: CNR1, KIT, HTR2A, DES, IL33, UCP2, and PPT1.

Fig. 6.

Diagnostic Model of RS. (A) Forest plot of 22 ARDEGs contained in Logistic regression model in RS diagnosis model. (B,C) The SVM method visualizes the number of genomes alongside the smallest rates of error (B) and the number of genes with the greatest precision rate (C). (D,E) The LASSO regression model is shown by plots of the diagnosis model (D) and variable locus (E). ARDEGs, Aging-Related Differentially Expressed Genes; SVM, Support Vector Machine; LASSO, Least Absolute Shrinkage, and Selection Operator.

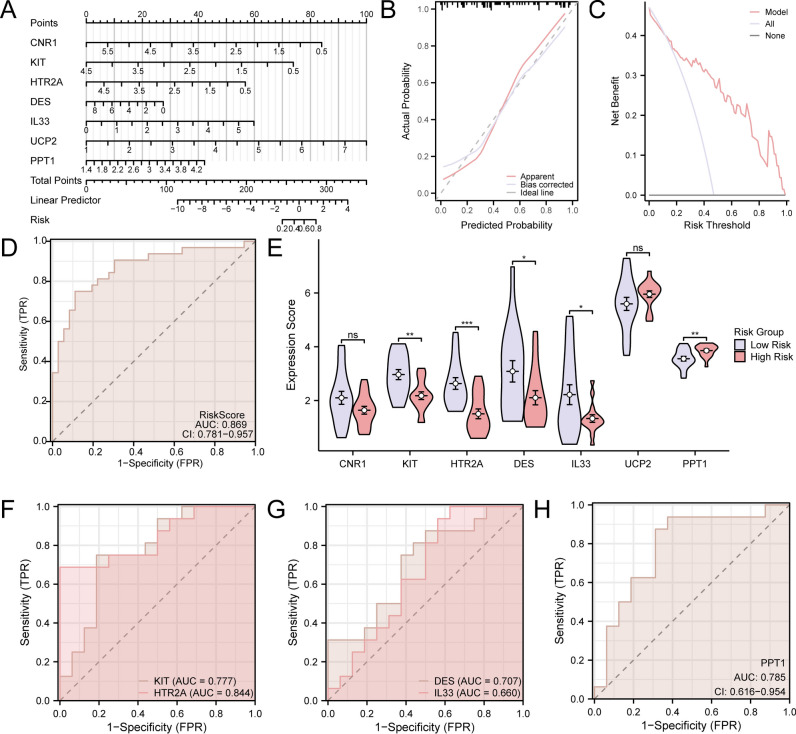

Verification of diagnostic model for renal calculi

To further validate the diagnostic model for RS, nomograms were constructed based on key genes to illustrate their interrelationships within the integrated GEO dataset (Fig. 7A). The results indicated that CNR1 expression had considerably higher utility than other factors in the RS diagnostic model, followed by DES.

Fig. 7.

(A) Nomogram for key genes in the renal stone (RS) diagnostic model using integrated GEO datasets. (B,C) Calibration curve (B) and decision curve analysis (C) for the RS diagnostic model based on key genes from integrated GEO datasets. (D) ROC curve of Risk Score in integrated GEO datasets. (E). Comparison of key genes in RS samples stratified by high and low risk. In the independent ROC-validated risk score model formula, PPT1 (coefficient = + 0.8583), IL33 (coefficient = + 0.5008), HTR2A (coefficient = -0.754), and KIT (coefficient = -1.0539). (F–H) ROC curves of KIT and HTR2A (F), DES and IL33 (G), and PPT1 (H) in RS samples, showing significant expression differences between high and low risk groups. For calibration curves, the y-axis represents net benefit, and the x-axis shows threshold probability. DCA: Decision Curve Analysis; ROC Curve: Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve. *: p—value < 0.05; **: p—value < 0.01; ***: p—value < 0.001. An AUC of 0.7–0.9 indicates moderate accuracy.

To evaluate the reliability and resolution of the RS predictive model, calibration analysis was performed. The calibration curve assessed the model’s predictive accuracy by comparing the fit between model-predicted probabilities and actual probabilities across various conditions (Fig. 7B). The calibration curve revealed that, while the calibration line (dashed line) somewhat deviated from the ideal model’s diagonal, it closely approximated it. DCA evaluated key genes from the integrated GEO dataset for the worth of RS diagnosis models in clinical use. The findings (Fig. 7C) showed that the model’s line surpassed both the entirely positive and negative lines within a specific context. Furthermore, the model’s greater net benefit indicates its superior performance. Additionally, ROC curves were generated using the R package pROC based on risk scores from the integrated GEO dataset. The ROC curves demonstrated that risk scores exhibited moderate accuracy (0.7 < AUC < 0.9) in the integrated GEO dataset, regardless of expression levels and groups. The risk score is calculated as follows:

|

RS samples were subsequently classified into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk score of the RS diagnostic model. Boxplots (Fig. 7D) were used to evaluate whether the expression levels of the seven key genes differed between high- and low-risk RS sample groups. The analysis showed that the expression of pivotal genes between high- and low-risk RS sample groups exhibited highly significant variation (p-value < 0.001) (Fig. 7E). Two key genes, KIT and PPT1, showed substantial statistical significance (p-value < 0.001). DES and IL33 also showed obvious statistical significance (p-value < 0.05). Finally, ROC curves for key genes with significantly different expression levels between high- and low-risk RS sample groups were plotted using the R package pROC. The ROC curves (Figs. 7F–H) indicated that the expression of genes KIT, HTR2A, DES, IL33, and PPT1 had moderate diagnostic accuracy (0.7 < AUC < 0.9) for distinguishing between high- and low-risk RS sample groups.

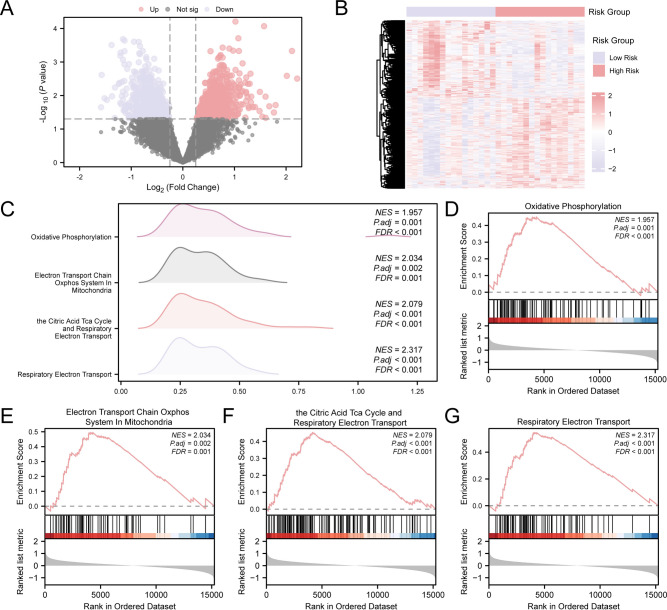

Disparity analysis between GSEA and groups with high or low expression

To further conduct differential analysis on RS, the RS samples were divided into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk score of the RS diagnostic model. The difference analysis of RS samples using R-packet limma showed that there were 1437 DEGs in RS samples. Among these, 776 genes revealed up-regulated (logFC > 0.25 and p—value < 0.05), while 661 genes displayed down-regulated (logFC < -0.25 and p—value < 0.05). According to the difference analysis results, a volcano map (Fig. 8A) was drawn. To present the analysis results, a heat map was generated for different genes utilizing the R package pheatmap (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Differential Gene Expression Analysis and GSEA for Risk Group. (A) Volcano map of differential gene expression between high- and low-risk groups among RS samples. (B) Heat map of DEGs between high- and low-risk groups in RS samples. (C) The mountain map of GSEA4 biological functions of RS samples is displayed. (D–G) GSEA indicated an extensive enrichment of RS in Oxidative Phosphorus (D), Electron Transport Chain Oxphos System in Mitochondria (E), the Citric Acid Tca Cycle and Respiratory Electron Transport (F) and Respiratory Electron Transport (G). GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. The screening criteria for GSEA are adj. p—value < 0.05 and FDR < 0.25.

GSEA was performed to investigate how gene expression levels in RS samples influence RS risk by examining their involvement in bioprocesses, affected cellular components, and molecular functions (Fig. 8C). See Table 4 for specific results. The findings revealed that all genomes present in the RS samples were enriched in biologically linked activities and signal pathways such as Oxidative Phosphorus (Fig. 8D), Electron Transport Chain Oxphos System in Mitochondria (Fig. 8E), the Citric Acid Tca Cycle and Respiratory Electron Transport (Fig. 8F) and Respiratory Electron Transport (Fig. 8G).

Table 4.

Results of GSEA for Risk Group.

| ID | Set Size | Enrichment Score | NES | p-value | p.adjust | qvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP_TYPE_I_INTERFERON_INDUCTION_AND_SIGNALING_DURING_SARSCOV2_INFECTION | 28 | 0.695471 | 2.4115 | 8.35E-07 | 0.0001 | 8.1E-05 |

| KEGG_LYSOSOME | 106 | 0.528733 | 2.342161 | 4.46E-10 | 1.53E-07 | 1.24E-07 |

| REACTOME_MITOCHONDRIAL_TRANSLATION | 83 | 0.547299 | 2.337755 | 3.4E-08 | 8.15E-06 | 6.6E-06 |

| REACTOME_RESPIRATORY_ELECTRON_TRANSPORT | 78 | 0.547449 | 2.317461 | 7.86E-08 | 1.35E-05 | 1.09E-05 |

| WP_MITOCHONDRIAL_COMPLEX_I_ASSEMBLY_MODEL_OXPHOS_SYSTEM | 41 | 0.623822 | 2.2947 | 1.48E-06 | 0.000162 | 0.000131 |

| REACTOME_INTERFERON_GAMMA_SIGNALING | 78 | 0.539937 | 2.285661 | 1.51E-07 | 2.26E-05 | 1.83E-05 |

| WP_TYROBP_CAUSAL_NETWORK_IN_MICROGLIA | 56 | 0.567871 | 2.243024 | 1.48E-06 | 0.000162 | 0.000131 |

| WP_PROSTAGLANDIN_SYNTHESIS_AND_REGULATION | 44 | 0.598436 | 2.239327 | 2.6E-06 | 0.000265 | 0.000215 |

| BIOCARTA_CBL_PATHWAY | 12 | 0.82368 | 2.236697 | 1.13E-05 | 0.000819 | 0.000663 |

| REACTOME_RESPIRATORY_ELECTRON_TRANSPORT_ATP_SYNTHESIS_BY_CHEMIOSMOTIC_COUPLING_AND_HEAT_PRODUCTION_BY_UNCOUPLING_PROTEINS | 82 | 0.519148 | 2.213303 | 1.32E-07 | 2.11E-05 | 1.71E-05 |

| REACTOME_INTERFERON_SIGNALING | 174 | 0.452919 | 2.181016 | 6.39E-10 | 1.92E-07 | 1.55E-07 |

| REACTOME_INFECTION_WITH_MYCOBACTERIUM_TUBERCULOSIS | 26 | 0.634725 | 2.175049 | 0.000148 | 0.00553 | 0.004475 |

| WP_PROTEASOME_DEGRADATION | 54 | 0.552531 | 2.174765 | 7.92E-06 | 0.000613 | 0.000496 |

| REACTOME_HS_GAG_BIOSYNTHESIS | 26 | 0.631992 | 2.165685 | 0.000178 | 0.006246 | 0.005054 |

| KEGG_N_GLYCAN_BIOSYNTHESIS | 42 | 0.586918 | 2.158876 | 4.89E-06 | 0.000408 | 0.00033 |

| WP_SARSCOV2_INNATE_IMMUNITY_EVASION_AND_CELLSPECIFIC_IMMUNE_RESPONSE | 60 | 0.535891 | 2.153066 | 4.94E-06 | 0.000408 | 0.00033 |

| REACTOME_COMPLEX_I_BIOGENESIS | 42 | 0.583425 | 2.146027 | 6.22E-06 | 0.000497 | 0.000402 |

| REACTOME_THE_CITRIC_ACID_TCA_CYCLE_AND_RESPIRATORY_ELECTRON_TRANSPORT | 128 | 0.453225 | 2.079203 | 6.51E-08 | 1.2E-05 | 9.72E-06 |

| WP_ELECTRON_TRANSPORT_CHAIN_OXPHOS_SYSTEM_IN_MITOCHONDRIA | 67 | 0.495695 | 2.033929 | 3.32E-05 | 0.00181 | 0.001465 |

| KEGG_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION | 92 | 0.4508 | 1.957464 | 1.89E-05 | 0.00116 | 0.000939 |

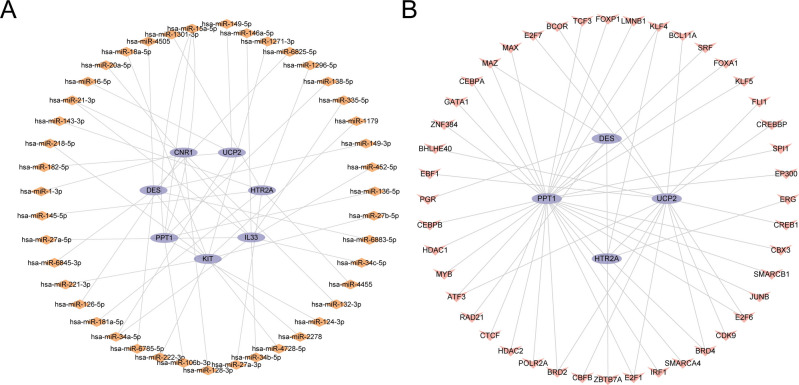

Construction of regulatory networks

First, miRNAs associated with key genes were gathered from the Tar Base and miRDB databases. These miRNAs were then used to construct the mRNA-miRNA Regulatory Network, which was visualized using the Cytoscape application (Fig. 9A). Among them, it contains 7 key genes and 43 miRNAs, see Table S2 for details. Subsequently, TFs connected to key genes were retrieved from the ChIPBase and HTFtarget databases. The application Cytoscape was employed to construct and display the mRNA-TF Regulatory Network (Fig. 9B). Among them, it contains 4 key genes and 44 TFs, see Table S3 for details.

Fig. 9.

Regulatory Network of Key Genes. (A) mRNA-miRNA regulatory networks for key genes. (B) mRNA-TF regulatory network of key genes. TF, Transcription Factor. Purple ovals represent mRNA, orange diamonds miRNA, and pink inverted triangles transcription factors.

GEO Integrated Data Set Immune Infiltration Analysis

The CIBERSORT algorithm was applied to figure out the immune infiltration abundance and correlation of 22 immune cells in the RS and control groups of the integrated GEO dataset. First, a histogram of the CIBERSORT immune cells was plotted on the outcomes of the immune infiltration investigation (Fig. 10A). Next, correlation heatmaps (Fig. 10B) displayed the abundance results from the CIBERSORT immune infiltration assay. The findings revealed the strongest positive association between T cells CD8 and Macrophages M1 (r-value = 0.439), and the strongest negative correlation between resting and activated NK cells (r-value = -0.474). Subsequently, correlations of key genes with immune cell infiltration abundance in the integrated GEO dataset were proved by correlation heat maps (Fig. 10C). The correlation heat map showed that DES exhibited the largest positive association with Mast cells resting (r-value = 0.599), and IL33 displayed the biggest negative relationship with T cells regulatory (Tregs) (r-value = -0.402).

Fig. 10.

Combined Datasets Immunological Infiltration Analysis utilizing CIBERSORT and ssGSEA. (A) Histogram of CIBERSORT immunological cell infiltrating abundance within the integrated GEO dataset. (B) Correlation heat map of CIBERSORT immunological cellular infiltrating abundance in integrated GEO dataset. (C) Heat map of correlations between CIBERSORT immunological cell infiltrating abundance with key genes in the incorporated GEO dataset. (D) Correlation heat map of ssGSEA immunological cellular infiltration abundance within integrated GEO dataset. (E) Heat map of correlations between key genes and ssGSEA immune cell infiltration abundance in the integrated GEO dataset. The absolute value of the correlation coefficient below 0.3 indicates weak or no correlation, between 0.3 and 0.5 weak correlation, between 0.5 and 0.8 moderate correlation, and above 0.8 strong correlation. Purple indicates a negative correlation and red positive correlation. Light red represents the renal RS group and light purple the normal group.

The ssGSEA algorithm was employed to evaluate the number and correlation of 24 immune cells in the RS group and control group of the combined GEO dataset, specifically in terms of immune infiltration. First, correlation results for immune cell infiltration abundance in ssGSEA immune infiltration assays were identified by drawing correlation heat maps (Fig. 10D). The finding revealed that T cm and T helper cells (r-value = 0.7807), Cytotoxic cells and B cells (r-value = 0.618), Mast cells and Cytotoxic cells (r-value = 0.676), T helper cells and CD8 T cells (r-value = 0.676) had moderate positive correlation. T helper cells and NK CD56 dim cells (r-value = -0.597), T cm cells and NK CD56 dim cells (r-value = -0.695), Treg cells and T helper cells (r-value = -0.598), T Reg cells and T cm cells (r-value = -0.591) showed moderate negative correlation.

Finally, correlations of key genes with immunity cell infiltrated abundance in the integrated GEO dataset ssGSEA were exhibited through correlation heat maps (Fig. 10E). Correlation heat map results showed that the key genePPT1 and immune cells macrophages (r-value = 0.526) had the strongest positive correlation, and the key geneHTR2A and immune cells TFH (r-value = -0.608) had the strongest negative correlation.

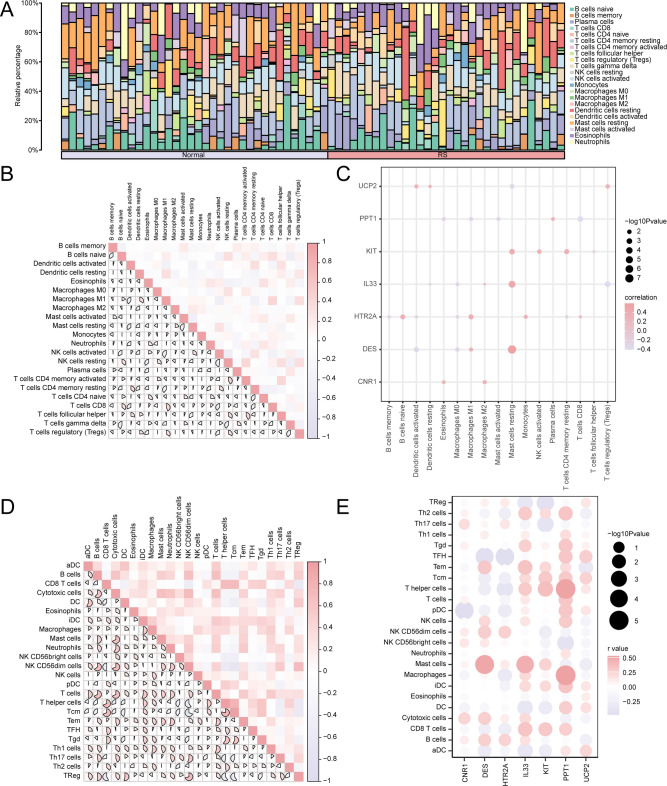

Immunoinfiltration analysis of renal stone samples

The CIBERSORT method was employed to determine the quantity and association of 22 immune cells in high- and low-risk groups of RS. First, using the findings of the immune infiltration investigation, a histogram was generated to visually represent the distribution of CIBERSORT immune cells in the GEO dataset (Fig. 11A). Next, correlation results for immune cellular infiltrating abundance from the CIBERSORT immune infiltration assay were displayed by heat maps (Fig. 11B). The results showed that CD4 memory resting of T cells was positively correlated with NK cells activated (r-value = 0.569), while Macrophages M1 was negatively correlated with Dendritic cells activated (r-value = -0.506). Subsequently, correlations of key genes with immune cell infiltration abundance in the integrated GEO dataset were proved by correlation heat maps (Fig. 11C). Correlation heat map results showed that the key gene IL33 showed the strongest correlation with T cells CD4 memory resting (r-value = 0.429).

Fig. 11.

Risk Group Immune Infiltration Analysis via CIBERSORT and ssGSEA. (A) RS samples’ CIBERSORT immune cell infiltration abundance histogram. (B) Correlation of CIBERSORT immune cell infiltration abundance within RS samples. (C) Heat map of correlation between key genes and CIBERSORT immune cell infiltration abundance in RS samples. (D) RS samples’ ssGSEA immune cell infiltration abundance correlation heatmap. (E) Heat map of correlation of key genes with ssGSEA immune cell infiltration abundance in RS samples. The absolute value of the correlation coefficient below 0.3 indicates weak or no correlation, between 0.3 and 0.5 weak correlation, and between 0.5 and 0.8 moderate correlation. Purple indicates a negative correlation and red positive correlation. Light red represents the High Risk group and light purple the Low Risk group.

The ssGSEA method was used to compute the immune infiltration abundance and correlation of 24 immune cells in the high- and low-risk groups of RS samples. First, correlation results for immune cellular infiltration abundance in ssGSEA immune infiltration assays were confirmed by producing correlation heat maps (Fig. 11D). The outcomes reflected that DC and aDC (r-value = 0.525), iDC and aDC (r-value = 0.653), Cytotoxic cells and B cells (r-value = 0.776), NK CD56 dim cells and B cells (r-value = 0.678), T cells as well as B cells (r-value = 0.789), T helper cells and CD8 T cells (r-value = 0.760), Mast cells and Cytotoxic cells (r-value = 0.741) were moderately correlated. There was a strong correlation between Mast cells and B cells (r-value = 0.823).

Finally, heatmaps (Fig. 11E) displayed the correlations between key genes and immune cell infiltration abundance in the integrated GEO dataset based on ssGSEA. The correlation heat map showed that the key genePPT1 was positively correlated with immune cells Macrophages (r-value = 0.680), DES was positively correlated with immune cells NK CD56 dim cells (r-value = 0.602), IL33 was positively correlated with immune cells Mast cells (r-value = 0.502), DES was positively correlated with immune cells Treg (r-value = 0.501). We observed negative correlations between HTR2A and Thelper cells (r-value = -0.608), DES with TFH (r-value = -0.534), HTR2A with Macrophages (r-value = -0.524).

Discussion

RS has become a widespread health concern worldwide, affecting people in both developed and developing countries37. However, the development of preventive and therapeutic countermeasures for RS has been lagging due to the unclear pathogenesis of RS and the lack of early diagnostic methods. In the field of renal stone research, although several recent studies have been devoted to unraveling its molecular mechanisms, the results often differ between studies38,39. This study, for the first time, considered genes associated with aging. Using advanced molecular biology techniques and data analysis methods, we successfully identified key kidney stone genes closely associated with aging, offering a new perspective for understanding renal stone pathogenesis.

In this study, we collected two GEO datasets and one RS dataset of aging-related genes. Through a series of bioinformatics analyses, we obtained 22 ARDEGs between RS and normal samples. GO analyses showed that these ARDEGs were involved in biological processes such as macrophage proliferation and neuroinflammatory responses, which may imply that abnormal immune responses during aging are associated with the formation and development of RS. GSEA enrichment studies based on the integration of each gene in the RS dataset showed that dendritic cells and interleukin transduction are key pathways in RS. In addition, we developed an RS diagnostic model incorporating machine learning methods and identified seven potential RS diagnostics (CNR1, KIT, HTR2A, DES, IL33, UCP2, PPT1). The high AUC values and good calibration of the model were evaluated using ROC curve analysis, demonstrating the excellent accuracy and reliability of the model in RS diagnosis. This model is expected to be applied in the clinic to help in the early diagnosis of RS. We also established mRNA-miRNA and mRNA-TF regulatory networks to better understand the progression of RS.

IL-33, a tissue-derived nuclear cytokine of the IL-1 family, is widely expressed in many tissue types40. During aging, cellular metabolic changes lead to metabolic product accumulation and pathway disruption, processes in which IL-33 plays a significant role. Research shows IL-33 induces macrophage metabolic reprogramming by promoting mitochondrial uncoupling protein expression, increasing mitochondrial respiratory chain uncoupling, and altering intracellular metabolite levels41. This metabolic reprogramming may cause accumulated metabolites to disrupt normal pathways, leading to metabolic imbalance. Additionally, IL-33 can improve insulin sensitivity, promote lipid metabolic balance, and reduce urinary calcium, oxalate, and uric acid concentrations, aiding urine dilution by decreasing free fatty acid (FFA) accumulation42,43. Metabolic imbalance and high uric acid levels can cause kidney cell dysfunction, affecting urine excretion and crystal formation, thus promoting RS formation. Moreover, IL-33 has multiple effects on immune cells. On one hand, it activates ILC2s to produce cytokines like IL-5 and IL-1344, which induce M2 macrophage polarization45, reducing inflammation and aiding urate crystal immune escape. On the other hand, IL-33 activates Treg cells via the ST2 receptor, promoting their proliferation and immune-regulatory molecule expression42, crucial for immune homeostasis and tissue repair. Therefore, boosting IL-33 expression may be vital for reducing stone formation risk, alleviating kidney inflammation, and lessening kidney damage.

Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) is a mitochondrial uncoupling protein that plays a crucial role in regulating cellular energy metabolism and oxidative stress 46. It acts as a key player as metabolism tends to become dysregulated with aging38927514. UCP2 expression declines with aging, which weakens the efficiency of mitochondrial energy utilization. UCP2 can lower mitochondrial membrane potential through mild uncoupling without affecting ATP production, thus preventing excessive ROS generation47. In a way, it acts like a switch, regulating cellular energy flow. The decline in mitochondrial metabolic efficiency not only impacts energy output but also disrupts lipid metabolism, leading to lipotoxicity48. When adipose tissue functions improperly, it releases a large amount of free fatty acids. The reduction in UCP2 means these fatty acids cannot be oxidized effectively, causing them to accumulate in cells and trigger lipid peroxidation. This lipotoxicity is extremely harmful to the kidneys. It may lead to a decrease in urinary ammonia production and excretion, a lowering of urine pH, and the supersaturation and precipitation of calcium oxalate and uric acid, which are components of RS49. The decrease in UCP2 also results in the accumulation of ROS, exacerbating kidney cell damage. Studies have shown that exposure to high concentrations of calcium ions can induce oxidative stress damage in renal tubular epithelial cells, activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, and trigger pyroptosis. This damage not only directly impairs kidney tissue but also promotes the formation of RS by increasing crystal adhesion and inflammatory responses50. Under oxidative stress conditions, UCP2 can protect kidney cells from damage by reducing ROS generation51. Moreover, ROS and lipotoxicity have a mutually reinforcing relationship. For example, 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), a product of lipid peroxidation, can further stimulate ROS production, creating a vicious cycle52. This cycle not only accelerates the formation of renal stones but also deteriorates the renal immune environment. Therefore, the expression of UCP2 may inhibit the development of renal stones by maintaining cellular energy metabolism and reducing ROS generation.

KIT (c-kit) is a receptor tyrosine kinase that, upon binding to its ligand stem cell factor, plays a key role in regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival53. Although no studies on c-kit have been found in the RS literature, it has been shown that renal-derived c-kit progenitor/stem cells play a reparative role in the glomerular disease process through a paracrine effect54, and tubular epithelial cell injury is an important prerequisite for the promotion of urinary microcrystalline attachment to form stones55.

The DES gene encodes a muscle-specific intermediate filament protein present in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscles. This protein, known as Desmin, is crucial for maintaining muscle structure, cell integrity, force transmission, and mitochondrial equilibrium56. During aging, cytoskeletal stability may be compromised, impairing renal tubular epithelial cells and increasing renal stone formation risk. Research shows that Desmin, the protein encoded by DES, maintains mitochondrial function by preserving mitochondrial membrane potential57. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key factor in RS. Dysfunctional mitochondria release excess ROS, causing lipid peroxidation and DNA damage, which promotes calcium oxalate (CaOx) crystal adhesion and aggregation in renal tubular epithelial cells58. Additionally, mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic pathways (e.g., BAX/BCL-2 imbalance) can lead to renal tubular epithelial cell death, releasing mitochondrial DNA and apoptotic bodies. These activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, fostering an inflammatory microenvironment and providing nucleation sites for crystals58,59. Thus, DES, by maintaining normal mitochondrial function, may play a key role in preventing RS development.

PPT1 is a lysosomal enzyme that is mainly responsible for the depalmitoylation modification of proteins, a process that plays an important role in the regulation of organelle (e.g., lysosomes, mitochondria) function, lipid metabolism, and Ca2⁺ transport60. During aging, lysosomal dysfunction and impaired autophagy flux are significant hallmarks61. As a lysosomal membrane protease, PPT1 expression changes may affect lysosomal degradation, causing cellular debris accumulation and inflammatory factor release, indirectly promoting RS matrix formation62. The absence or dysfunction of PPT1 will lead to abnormal lipid accumulation and affect cellular physiology and metabolism60. Previous studies have demonstrated that abnormal lipid metabolism is involved in the process of renal stone formation. Disturbances in renal lipid metabolism homeostasis can occur in the presence of changes in the extracellular environment, such as large amounts of unesterified fatty acids that are not bound and slowed or non-mobilized lipid droplets. In turn, excess free fatty acids and lipid droplet retention can induce chronic inflammatory responses, cause cellular damage, and ultimately promote RS formation63,64. In addition, the process of renal stone formation is accompanied by responses to organelle stress. For example, impaired mitochondrial function and endoplasmic reticulum stress synergistically play important roles in hyperoxaluria-induced RS formation58. Whereas, defects in PPT1 lead to reduced mitochondrial numbers, abnormal morphology, and impaired function, including disruption of mitochondrial membrane phospholipid metabolism, decreased membrane potential of mitochondria, disturbances in calcium-ion homeostasis, and overproduction of ROS65,66. All of these changes may exacerbate the level of organelle stress, thereby indirectly affecting renal stone formation.

HTR2A, the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor (5-HT2A receptor), is a G protein-coupled receptor belonging to the serotonin receptor family, and this receptor is widely distributed mainly in the central nervous system67. HTR2A is expressed in various immune cells, including B cells, T cells, and macrophages68. Studies have shown that selective 5—HT2A receptor antagonists can inhibit inflammatory cytokine release and promote macrophage M2 polarization69, which helps suppress RS development. Additionally, HTR2A is a crucial target for many antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs. Variants in the HTR2A gene, such as rs6311 (-1438G > A) and rs6313 (102C > T), have been studied for their correlation with drug response and side effects. 70. These polymorphisms can affect HTR2A expression and function, which in turn may influence pain perception and emotional responses in patients with renal stones. An observational study found that depressed patients had a significantly increased risk of developing renal stones71, so genetic factors, including HTR2A variants, may play an important role in both.

CNR1, a key part of the endocannabinoid system, is widely distributed in the central nervous system and peripheral tissues, including the kidneys72. Some studies have found that CNR1 activation can promote oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis, as well as participate in the regulation of renal hemodynamics and sodium reabsorption. These functional changes may also indirectly affect the formation of RS73. During aging, CNR1 expression in the human prefrontal cortex and hippocampus decreases significantly. This change may affect the endocannabinoid system’s overall function, accelerating cellular aging by altering the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Meanwhile, the G-protein coupling ability of the CB1 receptor encoded by CNR1 declines. This may influence extracellular matrix remodeling by modulating the inflammatory microenvironment, such as releasing SASP-related pro-inflammatory factors and chemokines74. Senescent cells secrete various inflammatory factors like TGF-β and IL-6, which can activate macrophages, drive renal interstitial fibrosis, and transform the renal interstitial microenvironment75,76. Renal interstitial fibrosis may slow urine flow, cause crystal retention, and increase stone-formation risk. The SASP-mediated inflammatory microenvironment, such as chronic low-grade inflammation, may also promote stone core formation through oxidative stress and calcium salt deposition. Furthermore, studies suggest CNR1 may play an important role in regulating the interaction between pain and emotions. Agonizing CNR1 can modulate the activity of the ACC (anterior cingulate cortex)-VTA (ventral tegmental area)-ACC positive feedback loop, thus alleviating pain and negative emotions77. This means that developing drugs or treatments targeting CNR1 could potentially relieve pain and discomfort in renal stone patients, improving their quality of life.

GO enrichment evaluation revealed that ARDEGs play a major role in biological processes such as macrophage proliferation and neuroinflammatory responses. Macrophage aggregation and macrophage-associated inflammation or anti-inflammation have been widely reported to play a key role in renal CaOx crystal formation78, and recruited macrophages can promote monohydrate CaOx crystal formation through the interaction of CD44 with osteoblasts and fibronectin79. It has been shown that miRNA-34a can inhibit cell adhesion by targeting CD44, thereby reducing renal stone formation80. Whereas the neuroinflammatory response affects renal interstitial fibrosis by activating immune cells and releasing inflammatory mediators. Studies have shown that macrophage polarization is involved in the mechanism of renal interstitial fibrosis, with M1-type macrophages promoting inflammation and fibrosis, whereas M2-type macrophages have anti-inflammatory and reparative effects, and renal macrophages express inflammatory vesicles, such as NLRP3, which can ultimately lead to renal inflammation, cellular pyroptosis, and renal fibrosis by mediating macrophage polarization. Potential therapeutic targets for kidney diseases include reduction of M1 polarization and induction of M2 polarization. Inhibitors of inflammatory vesicles such as NLRP3 and their signaling molecules are expected to be new therapeutic targets81. Meanwhile, the GSEA results showed that among the signaling pathways related to renal stones, Tnfr2 atypical Nf-Kb pathway, interleukin 4, and interleukin 13 signaling exhibited significant enrichment. Interleukin 4 and interleukin 13 are important anti-inflammatory cytokines, and these cytokines can regulate macrophage polarization through the JAK pathway and promote the formation of M2-type macrophages with phagocytosis of CaOx crystals, thereby inhibiting stone formation 82,83.

To deeply investigate the interactions between immune cells in RS, we performed a comprehensive assessment of the immune infiltration of RS. The results of immune infiltration in the integrated GEO dataset RS and Normal groups revealed the strongest positive correlation between immune cells T cells CD8 and Macrophages M1, and the strongest negative correlation between immune cells NK cells resting and NK cells activated. The results of immune infiltration in the high-risk and low-risk groups in RS samples revealed that immune cell T cells CD4 memory resting had the strongest positive correlation with NK cells activated, and immune cell Macrophages M1 had the strongest negative correlation with Dendritic cells activated. Macrophages M1 and Dendritic cells activated had the strongest negative correlation. It has been previously shown that M1-type and M2-type macrophages play different roles in the formation and development of renal stones.M1-type macrophages play a pro-inflammatory role in renal stone formation, where they induce renal epithelial cell damage by releasing inflammatory factors and ROS, which promotes the deposition of CaOx crystals82. In contrast, M2-type macrophages play an anti-inflammatory role in renal stone formation, and they inhibit stone development by phagocytosis of CaOx crystals84. Moreover, M2-type macrophages are more phagocytic than M1-type macrophages, and regulation of macrophage polarization may be of great therapeutic value for RS82. There is a contradiction in the roles of NK cells in renal injury85. On the one hand, NK cells may promote renal epithelial cell injury by releasing inflammatory factors and cytotoxic particles, thereby promoting CaOx crystal deposition86. On the other hand, NK cells may also play a protective role by modulating the immune response to reduce inflammation87. Activated dendritic cells (DCs) may also play an important role in the immunological environment of renal stone formation and development. Environment. DCs are important antigen-presenting cells that mature and migrate to secondary lymphoid organs to activate T cells after capturing antigen. It has been shown that renal ischemia/reperfusion injury can affect the differentiation and maturation status of DCs, which in turn affects the immune response88.

Diagnosing RS is challenging, typically relying on clinical history and imaging, which have limitations and can lead to misdiagnosis2. Through bioinformatics, we’ve identified CNR1, KIT, HTR2A, DES, IL33, UCP2, and PPT1 as potential RS biomarkers. Our nomogram shows strong predictive power, aiding clinical decisions. We’ve also explored aging-related RS mechanisms and their immune interactions. For instance, UCP2, IL33, and PPT1 drive metabolic imbalance, lipotoxicity, and oxidative stress; KIT is involved in the repair of renal cell tissue; CNR1 mediates the secretion of fibrotic factors and remodels the renal microenvironment; and HTR2A and IL33 disrupt the M1/M2 macrophage balance, affecting crystal formation. This framework supports combined therapies targeting aging pathways and immune checkpoints. Unlike previous studies that focused on crystal chemistry or single inflammatory pathways89, we integrated aging genes and immune microenvironments, revealing a metabolic-aging-immune network of seven key genes. We emphasize IL33's role in metabolic disorders and its new mechanism in inhibiting crystal immune evasion through the ILC2-M2 macrophage axis.

The renal stone diagnostic model based on seven key genes (CNR1, KIT, HTR2A, DES, IL33, UCP2, PPT1) shows great translational potential in clinical practice. First, analyzing these genes’ expression via non-invasive detection can achieve early screening and precise molecular classification of renal stones, such as differentiating inflammatory and metabolic types. Second, the risk-score model allows dynamic prognosis assessment, enabling personalized disease management, like increased follow-up frequency for high-risk patients. Third, therapeutically, targeting specific genes can be beneficial: antagonizing IL33 to suppress inflammation, using PPT1 to repair lysosomal function, and inhibiting HTR2A to relieve neuropathic pain. Looking ahead, we plan to verify the model’s generalizability in multi-center cohorts (e.g., UK Biobank and BioBank Japan), conduct a phase II clinical trial of an HTR2A antagonist, and use gene—editing to study the interaction between UCP2 and DES, mitochondria, and inflammation, providing stronger support for renal stone diagnosis, treatment, and management.

Our study employed bioinformatics and machine learning to identify key genes and develop a diagnostic model. However, the study has limitations, including dataset selection bias, a small sample size, and a lack of external validation. Most crucially, we have not conducted in vivo or in vitro experimental validations such as qPCR or Western blot. Due to these limitations, especially the absence of experimental verification, our conclusions may not fully reflect biological reality. Further experimental validation is necessary to confirm the reliability of our results and their clinical relevance. We plan future experimental validations, including qPCR, Western blotting, and in—vitro or in—vivo models to explore key gene functions.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [grant number 82274512]; the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation [grant number 2023A1515110654]; the Scientific research project of the National inheritance and Innovation Center of traditional Chinese Medicine [grant number 2023QN10].

Author contributions

CChen, SX, and YW contributed to the study design and critical revision of the manuscript. YW, NC, and BZ carried out the study and drafted the manuscript. PZ, BT, CC, NH, and HN analyzed the data and provided tables or pictures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. Gene expression data from the GEO repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) include the following datasets: GSE73680, GSE117518.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuanzhao Wang and Nana Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Songtao Xiang, Email: tonyxst@gzucm.edu.cn.

Chiwei Chen, Email: chenchiwei5542@163.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-05087-w.

References

- 1.Shastri, S. et al. Kidney Stone Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Management: Core Curriculum 2023. Am. J. Kidney Dis.82(5), 617–634 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thongprayoon, C., Krambeck, A. E. & Rule, A. D. Determining the true burden of kidney stone disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol.16(12), 736–746 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He, M. et al. Recent advances in the treatment of renal stones using flexible ureteroscopys. Int. J. Surg.110(7), 4320–4328 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyall, V. S., Wood, K. D. & Pais, V. J. Hydrochlorothiazide and Prevention of Kidney-Stone Recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med.388(21), 2014 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan, S. R. et al. Kidney stones. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers2, 16008 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paranjpe, I. et al. Derivation and validation of genome-wide polygenic score for urinary tract stone diagnosis. Kidney Int.98(5), 1323–1330 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontenelle, L. F. & Sarti, T. D. Kidney Stones: Treatment and Prevention. Am. Fam. Physician99(8), 490–496 (2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran, T. et al. Impact of age and renal function on urine chemistry in patients with calcium oxalate kidney stones. Urolithiasis49(6), 495–504 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raymakers, J. A. Hypercalcemia in the elderly. Tijdschr. Gerontol. Geriatr.21(1), 11–16 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander, R. T., Fuster, D. G. & Dimke, H. Mechanisms Underlying Calcium Nephrolithiasis. Annu. Rev. Physiol.84, 559–583 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, Y. C. et al. Association between elevated serum uric acid levels and high estimated glomerular filtration rate with reduced risk of low muscle strength in older people: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr.23(1), 652 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duong, L. et al. Macrophage function in the elderly and impact on injury repair and cancer. Immun Ageing18(1), 4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, Z. et al. Recent advances on the mechanisms of kidney stone formation (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med.10.3892/ijmm.2021.4982 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajam Y A, Rani R, Ganie S Y, et al. Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology and Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cells, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Taguchi, K. et al. M1/M2-macrophage phenotypes regulate renal calcium oxalate crystal development. Sci. Rep.6, 35167 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taguchi, K. et al. Genome-Wide Gene Expression Profiling of Randall’s Plaques in Calcium Oxalate Stone Formers. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.28(1), 333–347 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis, S. & Meltzer, P. S. GEOquery: a bridge between the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics23(14), 1846–1847 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stelzer, G. et al. The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics54, 1–30 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Leek, J. T. et al. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics28(6), 882–883 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.43(7), e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mi, H. et al. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucl. Acids Res.47(D1), D419–D426 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu, G. et al. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS16(5), 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A102(43), 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanz, H. et al. SVM-RFE: selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinform.19(1), 432 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engebretsen, S. & Bohlin, J. Statistical predictions with glmnet. Clin. Epigenetics11(1), 123 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu, J. et al. A nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer Commun. (Lond)40(7), 301–312 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Calster, B. et al. Reporting and Interpreting Decision Curve Analysis: A Guide for Investigators. Eur. Urol.74(6), 796–804 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vlachos I S, Paraskevopoulou M D, Karagkouni D, et al. DIANA-TarBase v7.0: indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA:mRNA interactions. Nucl. Acids Res., ,43(Database issue):D153-D159. (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Chen, Y. & Wang, X. miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucl. Acids Res.48(D1), D127–D131 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res.13(11), 2498–2504 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou K R, Liu S, Sun W J, et al. ChIPBase v2.0: decoding transcriptional regulatory networks of non-coding RNAs and protein-coding genes from ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res., (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Zhang, Q. et al. hTFtarget: A Comprehensive Database for Regulations of Human Transcription Factors and Their Targets. Genomics Proteomics Bioinform.18(2), 120–128 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods12(5), 453–457 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao, B. et al. Identification and Verification of Immune-Related Gene Prognostic Signature Based on ssGSEA for Osteosarcoma. Front Oncol.10, 607622 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bindea, G. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity39(4), 782–795 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peerapen, P. & Thongboonkerd, V. Kidney Stone Prevention. Adv. Nutr.14(3), 555–569 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aji, K. et al. Comprehensive analysis of molecular mechanisms underlying kidney stones: gene expression profiles and potential diagnostic markers. Front Genet.15, 1440774 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hua, Y. et al. Exploring the molecular interactions between nephrolithiasis and carotid atherosclerosis: asporin as a potential biomarker. Urolithiasis52(1), 169 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cayrol C. IL-33, an Alarmin of the IL-1 Family Involved in Allergic and Non Allergic Inflammation: Focus on the Mechanisms of Regulation of Its Activity. Cells, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Faas, M. et al. IL-33-induced metabolic reprogramming controls the differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages and the resolution of inflammation. Immunity54(11), 2531–2546 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liew, F. Y., Girard, J. P. & Turnquist, H. R. Interleukin-33 in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol.16(11), 676–689 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Purnamasari, D. et al. The role of high fat diet on serum uric acid level among healthy male first degree relatives of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci. Rep.13(1), 17586 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amisaki, M. et al. IL-33-activated ILC2s induce tertiary lymphoid structures in pancreatic cancer. Nature638(8052), 1076–1084 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kral, M. et al. ILC2-mediated immune crosstalk in chronic (vascular) inflammation. Front Immunol.14, 1326440 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo, J. Y. et al. Endothelial UCP2 Is a Mechanosensitive Suppressor of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res.131(5), 424–441 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nesci S, Rubattu S. UCP2, a Member of the Mitochondrial Uncoupling Proteins: An Overview from Physiological to Pathological Roles. Biomedicines (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.van Dierendonck, X. et al. The role of uncoupling protein 2 in macrophages and its impact on obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem.295(51), 17535–17548 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen, L. et al. Kidney stones are associated with metabolic syndrome in a health screening population: a cross-sectional study. Transl. Androl. Urol.12(6), 967–976 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiang, J. et al. Mechanistic studies of Ca(2+)-induced classical pyroptosis pathway promoting renal adhesion on calcium oxalate kidney stone formation. Sci. Rep.15(1), 6669 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mao, S. Emerging role and the signaling pathways of uncoupling protein 2 in kidney diseases. Ren. Fail46(2), 2381604 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu W, Zhu Y, Wang S, et al. From Adipose to Ailing Kidneys: The Role of Lipid Metabolism in Obesity-Related Chronic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants (Basel), (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Martinez-Anton, A. et al. KIT as a therapeutic target for non-oncological diseases. Pharmacol. Ther.197, 11–37 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rangel, E. B. et al. Kidney-derived c-kit(+) progenitor/stem cells contribute to podocyte recovery in a model of acute proteinuria. Sci. Rep.8(1), 14723 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng, H. et al. Interaction between submicron COD crystals and renal epithelial cells. Int. J. Nanomedicine7, 4727–4737 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agnetti, G., Herrmann, H. & Cohen, S. New roles for desmin in the maintenance of muscle homeostasis. FEBS J.289(10), 2755–2770 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dayal, A. A. et al. Vimentin and Desmin Intermediate Filaments Maintain Mitochondrial Membrane Potential. Biochemistry (Mosc)89(11), 2028–2036 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaiyarit, S. & Thongboonkerd, V. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Kidney Stone Disease. Front Physiol.11, 566506 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Canela, V. H. et al. A spatially anchored transcriptomic atlas of the human kidney papilla identifies significant immune injury in patients with stone disease. Nat. Commun.14(1), 4140 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]