Abstract

Rosa species hold considerable economic and medicinal importance, used in traditional medicine, essential oils, and landscaping. However, the mechanisms of floral scent formation in roses are not well understood, hindering genetic improvement. To bridge this gap, we conducted a combined transcriptome and metabolome analysis, identifying nine key fragrance compounds. Using Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), we linked 574 genes to these compounds. From these, we identified candidate genes through differential expression, functional annotations, and protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks. We predicted candidate genes, NUDIX1, NUDIX2, GERD, AFS1, AFS2, CYP82G1, HMG1, NCED2, CCD7, PSY, ICMEL2, MAD1, and MAD2 that might terpenoid-related genes, as well as potential benzenoid/phenylpropanoid-related candidate genes, DET2, DET3, ICS2, PAL1, UGT74B1, MYB330, GST, CAD1, HST, PCBER1, LAC15, CSE, PER25, PER47, PER63, FBA, LNK2, PRE1, and PRE6. Additionally, three function-unknown genes, LOC112167529, LOC112174760, and LOC112183447, were predicted as candidate genes potentially involved in the formation of floral scent.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-08137-5.

Keywords: Rosa, Floral scent, WGCNA, PPI, Hub gene

Subject terms: Metabolomics, Metabolomics, Transcriptomics

Introduction

The genus Rosa, a member of the Rosaceae family, comprises approximately 300 species and a diverse array of cultivars1. Rosa, commonly known as the rose, is a woody perennial flowering plant indigenous to Asia, North America, Europe, and northwest Africa. Rose has been used for its medicinal, nutritional, and ornamental properties. Although cultivars grown to extract floral scent components are less, they can bring greater economic value than ornamental cultivars. For instance, Rosa damascena, known for its distinctive scent, has been cultivated in the perfume, cosmetic, and healthcare industries2.

The floral scent compounds in roses vary among varieties and are influenced by climatic conditions, soil composition, agronomic practices, and other stimuli3. Fragrant rose petals serve as edible organs and sources for essential oil extraction. The components of petal extracts are primarily derived from secondary metabolites, which are bioactive compounds with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties4,5. The essential components of rose essential oils include 2-phenylethanol, citronellol, nonadecane, geraniol, nerol, linalool, heneicosane, β-caryophyllene, and phenyl ethyl acetate6,7. Additionally, it contains allyl-chain-substituted guaiacol derivatives, such as eugenol and methyl eugenol. The formation of floral scent compounds is linked to terpenoid, phenylpropanoid, and fatty acid metabolic pathways8. However, further investigation is required to determine whether there are other pathways involved in regulating floral scent formation.

The biosynthesis of these fragrant compounds is regulated by multiple genes, some of which have been successfully cloned from roses9. For example, the rose alcohol acetyltransferase gene has been cloned and transferred into petunia to investigate its ability to convert phenyl ethyl alcohol and benzyl alcohol into the corresponding acetate esters10; The carotenoid cleavage oxygenase gene plays a role in the biosynthesis of terpenes, such as β-ionone11,12; The phenylacetaldehyde synthetase gene is involved in 2-phenylethanol production13; The Nudix hydrolase 1 gene has been discovered as part of a monoterpenoid synthesis pathway that catalyzes geraniol synthesis, enhancing floral aroma14. Besides, specific genes have been speculated involved in floral scent metabolite biosynthesis in roses. For instance, the orcinol O-methyltransferase gene may be crucial in fragrance production in seasonal flowers15–17; The rose deoxy-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase and alpha-1 antitrypsin genes obtained from the rose cultivar Tangzi are considered important candidates to regulate the secondary metabolism of aromatic components, potentially playing a key role in monoterpene biosynthesis18.

Despite identifying several genes associated with the rose fragrance phenotype, there remains a dearth of research on screening key genes for genetic improvement, given the complexity of fragrance substances and their metabolic pathways. This study examined the metabolome and transcriptomes of petal samples from three fragrant rose cultivars and one scentless rose. Metabolome and transcriptome data were integrated and analyzed using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to identify potential floral scent formation-related genes. Then, protein-protein interactions (PPI) analysis was employed to predict hub genes involved in floral scent formation and their related regulatory mechanisms. The findings of this study provide valuable insight into the selection and genetic enhancement of fragrant roses.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Four rose varieties, including Rosa hybrida cv. ‘Iceberg’, Rosa hybrida cv. ‘Damascena’, Rosa var. ‘Qin Xiang’, and Rosa hybrida cv. ‘Crimson Glory’, were used (Fig. S1). The four cultivars were grown in a nursery at Chongqing Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Iceberg with white scentless flowers was used as the control group, while the others with pink or red flowers with strong fragrances were used as the treatment groups. Petal samples were collected from the four plants during the blooming stage. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C. In this study, four repetitions of petal samples for each variety were prepared for subsequent omics tests. The abbreviations CK, DM, QX, and CG represent the Iceberg, Damascena, Qin Xiang, and Crimson Glory groups, respectively.

Metabolomic analysis

Non-target metabolomic analysis of rose samples was performed using gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOF/MS) and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (UHPLC–ESI–MS/MS) platforms. Metabolites were extracted and detected using Suzhou PANOMIX Biomedical Tech Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). The metabolite extraction and detection procedures for GC-TOF/MS were conducted following published protocols19,20. Similarly, for UHPLC–ESI–MS/MS, the extraction method21, liquid chromatography conditions22, and mass spectrometry conditions23 were used according to published protocols.

The metabolomics data were analyzed and graphed using the R platform (version 4.3.1). All metabolites were annotated using the PANOMIX, Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), Mzcloud, Massbank, LipidMaps, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases. Orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) models were established using multiple supervision methods to screen differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) between the scentless and fragrant groups. The relative importance of each metabolite in the OPLS-DA model was tested using the variable importance in projection (VIP) value. Metabolites with VIP ≥ 1 and P < 0.05 were considered DAMs.

Transcriptome sequencing and functional annotation analysis

Total RNA extraction, RNA library construction, and transcriptome sequencing were performed by the Suzhou PANOMIX company. Briefly, the total RNA of rose petals was extracted using the MirVana miRNA isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of the RNA was evaluated using Agilent2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The polyA mRNA was enriched from total RNA using Oligo (dT) magnetic beads and RNA was interrupted to a length of about 300 bp by ion interruption. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with 6-base random primers and reverse transcription using RNA as the template, followed by second-strand cDNA synthesis using first-strand cDNA as the template. RNA library fragments were enriched using PCR amplification and selected library according to the fragment size (450 bp). Then the concentration of the library was detected using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Finally, the RNA libraries were paired-end (PE) sequenced using next-generation sequencing (NGS) based on the Illumina HiSeq platform. Raw reads were processed by removing low-quality reads, reads containing adapters, and reads with an average quality score below Q20. Clean reads were aligned to the Rosa reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/11715) using TopHat224. Functional annotations of the mRNAs were performed using various databases, including gene ontology (GO), KEGG, eggNOG, Swiss-Prot, and Non-Redundant Protein Sequence Database (NR).

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis was applied using the “DESeq2” package (http://bioconductor.org) in the R platform. Moderated t-tests were performed using empirical Bayes estimation to determine the fold change between each fragrant rose (QX, DM, and CG) and CK. The adjusted P-value for multiple testing was calculated using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. DEGs were screened based on the threshold criteria of log2|fold change| ≥ 2 and P < 0.05.

Gene co-expression network construction

The gene co-expression network was constructed using the R package “WGCNA” based on gene expression values (FPKM, fragments per kilobase per million). Before network construction, an appropriate soft threshold value was computed and determined. The genes were assigned to different modules based on their co-expression relationships, and the relative contents of DAMs were used as traits to calculate module-trait relationships. Additionally, module eigengenes (MEs) were calculated to determine the primary components of the first principal component within a module with the same expression profile, thereby capturing the overall characteristics of module genes. Hub genes were identified by computing gene significance (GS) and module membership (MM). The MM was defined as the correlation between the expression profile and ME. Trait-related genes were selected according to the threshold of |GS| ≥ 0.9 and |MM| ≥ 0.8.

PPI network construction

The WGCNA-selected genes were mapped to the STRING database (version 12.0) for PPI network construction to screen hub genes. The PPI network was constructed using a package “STRINGdb” in R that provides the R interface to the STRING PPI database (http://www.string-db.org). Additionally, the PPI network was visualized using the package “igraph”. To explore the regulatory mechanisms, interactions with a combined score of > 0.400 (medium confidence score) were imported into Cytoscape (version 3.10.2) for topological analysis algorithms. The maximal clique centrality (MCC), maximum neighborhood component (MNC), density of MNC (DMNC), and Bottleneck were obtained in Cytoscape using the CytoHubba plugin. The top genes with high scores of MNC, MCC, DMNC, and Bottleneck were defined as hub genes.

Validation of transcriptome data using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from petal samples using the SteadyPure Plant RNA Extraction Kit (Accurate Biology, AG21019, China) and quantified using a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). These petal samples were from the same sample of RNA sequencing. The cDNA was reverse-transcribed using the Evo M-MLV Mix Kit with gDNA Clean for qPCR (Accurate Biology, AG11728, China). RNA expression was normalized by quantifying the Ubiquitin C (UBC) as a housekeeping gene. The qRT-PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX 96 RT-PCR system using the SYBR Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (Accurate Biology, AG11701, China). The data were analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method. Primers were designed using Primer525 and are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Results and discussion

Fragrant roses, known for their oil-bearing properties, are extensively cultivated in the temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The biosynthesis of floral fragrance compounds is crucial for roses used in essential oil production. Recent advancements in genetic research on floral scent formation have encountered challenges due to the intricate nature of its metabolic regulatory pathways and the diverse array of aroma components. An integrative analysis of the metabolome and transcriptome offers a promising approach to elucidate the relationship between genes and metabolites. To bridge this knowledge gap, a comprehensive dataset comprising petal metabolome and transcriptome data was generated for fully bloomed petals, as this developmental stage exhibits the highest concentration of fragrance components26.

Metabolic differences between the fragrant and scentless roses

A comprehensive analysis identified 816 metabolites across four rose varieties, with 254 metabolites detected via GC-TOF/MS (Supplementary Excel 1) and 562 via UHPL–ESI–MS/MS (Supplementary Excel 2). The metabolic profiles are illustrated through heatmaps (Figs. S2A-B), which reveal distinct variations in metabolite abundance and enrichment among the different rose varieties.

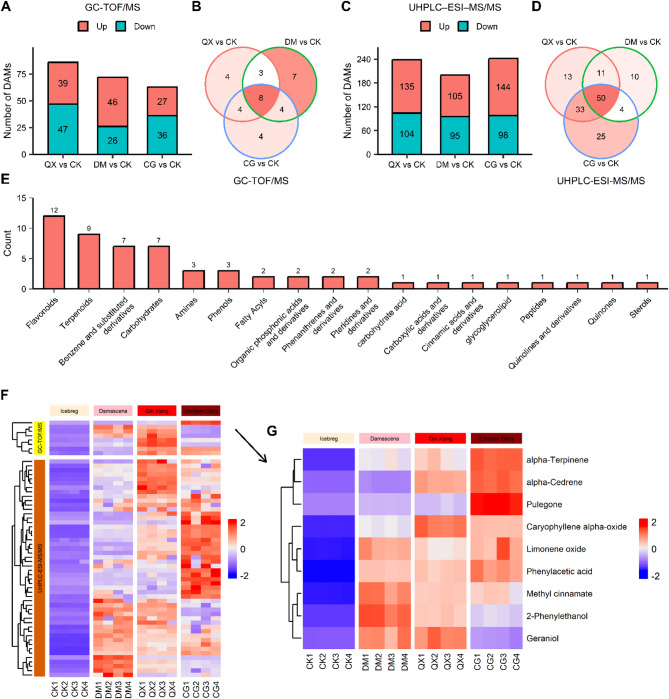

Further analysis of the metabolite data was conducted using OPLS-DA with the R package “ropls” to identify the DAMs (VIP > 1, P < 0.05, log2|FoldChange| > 1). Based on GC-TOF/MS data, 27, 46, and 39 metabolites were upregulated in CG, DM, and QX, respectively, compared to CK (Fig. 1A). Metabolites exhibiting significant upregulation (log2FoldChange > 2) within each comparison group were subsequently identified. A Venn diagram highlights the shared metabolites, identifying eight that are significantly upregulated (Fig. 1B). Similarly, analysis of the UHPLC–ESI–MS/MS data revealed that 144, 105, and 135 metabolites were upregulated in CG, DM, and QX, respectively (Fig. 1C), with 50 of these being highly upregulated and overlapping (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of differential metabolites between the fragrant and scentless roses. (A) Number of differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) of GC-MS data (VIP > 1, P < 0.05, log2|FoldChange| > 1). (B) Venn diagram illustrates the numbers of highly upregulated (log2FoldChange > 2) DAMs of GC-MS data. (C) Number of DAMs of LC-MS data. (D) Venn diagram illustrates the numbers of highly upregulated DAMs of LC-MS data. (E) Classification of overlapping DAMs of the GC-MS and LC-MS data. (F) Heatmap of overlapping DAMs. (G) Selected floral scent metabolites from overlapping DAMs. GC-MS, GC-TOF/MS; LC-MS, UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS; CK, Iceberg; DM, Damascena; QX, Qin Xiang; CG, Crimson Glory.

We categorized all overlapping metabolites into 18 distinct classes, with flavonoids representing the most abundant class, followed by terpenoids, benzene and substituted derivatives, and carbohydrates (Fig. 1E). A heatmap displays the relative abundance of these overlapping metabolites (Fig. 1F). Despite the significant accumulation of these metabolites in fragrant roses compared to the control group, the heatmap indicates variability in metabolite accumulation among different varieties.

Terpenoids, benzenoids/phenylpropanoids, fatty acid derivatives, and other compounds are prevalent constituents of floral fragrances5,8. Consequently, floral fragrance compounds were selected from these categories. Based on metabolite classification and an extensive literature review, we identified nine of these overlapping metabolites as targets for subsequent gene association analysis (Table 1; Fig. 1G). Among the selected compounds, four were identified as monoterpenoids, two as sesquiterpenoids, and three as benzene-containing compounds.

Table 1.

Floral fragrance compounds selected by comparing the four Rose species.

| No. | Compound | PubChem ID | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | ||||

| 1 | Geraniol | 637,566 | It is a monoterpenoid with a sweet rose odor and is a common constituent of rose essential oil. | 3,7,27 |

| 2 | Pulegone | 442,495 | It is a monoterpene ketone with a pleasant natural minty fragrance and taste. | 28,29 |

| 3 | Alpha-Terpinene | 7462 | It is a monoterpene with a cyclohexadiene, refreshingly herbaceous-citrusy, and is found in the essential oils of many aromatic plants. | 30 |

| 4 | Limonene oxide | 91,496 | It is a limonene monoterpenoid and an epoxide with a citrusy aroma. Limonene is a common constituent of floral scent. | 3,4,7 |

| 5 | Alpha-Cedrene | 6,431,015 | It is a sesquiterpene with a fresh, light woody aroma that has a role as a volatile oil component. | 31 |

| 6 | Caryophyllene alpha-oxide | 14,350 | It is a sesquiterpenoid with an odor midway between cloves and turpentine. Caryophyllene is a common constituent of floral scent. | 4,7 |

| Benzene-containing compounds | ||||

| 7 | 2-Phenylethanol | 6054 | It is a primary alcohol and a member of benzenes and is one of the abundantly emitted scent compounds in rose flowers. | 5,7,32,33 |

| 8 | Phenylacetic acid | 999 | It contains a phenyl functional group and an acetic acid functional group and is used in some perfumes, possessing a honey-like odor. | 32 |

| 9 | Methyl cinnamate | 637,520 | It is a methyl ester and an alkyl cinnamate with a fruity balsamic scent and is widely used in the flavor and perfume industries. | 34 |

Assembly and annotation of the Rose transcriptome

Transcriptome sequencing technology enables large-scale sequencing of transcripts from specific tissues of a species at a particular developmental stage. Notably, the fully expanded stage of rose petals exhibits the highest concentration of fragrance components26, suggesting that certain genes actively transcribed during this phase may contribute to the biosynthesis of floral fragrance.

We prepared and analyzed 16 RNA libraries derived from rose petals (Supplementary Excel 3). Supplementary Table 2 presents the transcriptome data statistics and quality assessments. The findings demonstrated high sequencing quality and a well-balanced base composition, meeting the standards for high-throughput sequencing quality. Following sequence alignment, a total of 30,924 genes were identified for subsequent analysis. A heatmap and a principal component analysis (PCA) plot illustrating global expression patterns were generated (Figs. S3A-B), which revealed consistent expression patterns across all biological replicates, thereby confirming the reliability of the sequencing data. These results can validate the adequacy of sequencing quality for subsequent analyses.

Identification of DEGs in Rose petals

DEGs were identified using the “DESeq2” package, applying a screening threshold of P-adjust < 0.05 and log2|fold change| > 2. In the comparative analyses of QX versus CK, DM versus CK, and CG versus CK, we identified 3,916, 4,795, and 4,158 DEGs, respectively. Specifically, within the QX versus CK, 2,187 genes were upregulated and 1,729 genes were downregulated (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in DM versus CK, 2,486 genes were upregulated, and 2,309 genes were downregulated (Fig. 2B). In CG versus CK, 2,072 genes were upregulated, and 2,086 genes were downregulated (Fig. 2C). Venn analysis further revealed 1,634 overlapping DEGs across the three groups (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis. (A) Volcano plot of RNA-seq data of QX versus CK group. (B) Volcano plot of RNA-seq data of DM versus CK group. (C) Volcano plot of RNA-seq data of CG versus CK group. (D) The Venn diagram illustrates the overlapping DEGs among the comparative groups. (E) The UpSet plot illustrates number of the expressed genes (FPKM > 1.0) from the overlapping DEGs. DEGs were classified as expressed (FPKM > 1.0) and non-expressed (FPKM < 1.0) genes. CK, Iceberg; DM, Damascena; QX, Qin Xiang; CG, Crimson Glory.

Genes with FPKM < 1.0 were classified as non-expressed. To identify genes potentially associated with fragrant roses, the genes that were non-expressed in these fragrant roses were excluded from the 1,634 overlapping DEGs. Namely, gene was retained if its mean of FPKM was greater than 1 both in the QX, DM, and CG varieties. An UpSet plot was employed to illustrate the retained number of expressed genes, resulting in a total of 1,025 genes (Fig. 2E), which were subsequently used for WGCNA.

Identification of floral fragrance-related genes using WGCNA

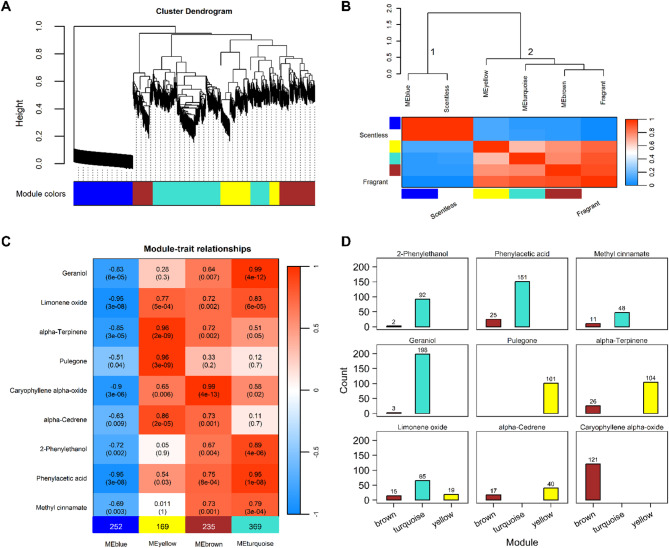

WGCNA is an effective method for constructing gene co-expression networks and elucidating the relationships between gene networks and target traits35,36. The 1,025 genes identified from the UpSet plot were employed to generate co-expression network modules. Before network construction, the soft-threshold power (β) was determined using the R function “pickSoftThreshold”, which identified an optimal β value of 12 (Fig. S4).

The analysis revealed four distinct co-expression modules within the cluster dendrogram, labeled as the blue, yellow, brown, and turquoise modules, comprising 252, 169, 235, and 369 genes, respectively (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, the eigengenes of these modules were calculated and clustered based on their correlations to assess their co-expression similarities. The eigengene adjacency heatmap effectively segregated the modules into two distinct clusters. Cluster 1 was composed of a single module (the blue module) that exhibited a positive association with the scentless rose (Fig. 3B). Conversely, Cluster 2 encompassed three modules that predominantly demonstrated positive associations with the fragrant roses (Fig. 3B). These findings suggest that the genes within the blue module exhibited a negligible association with the formation of floral fragrance. Consequently, genes related to floral fragrance were selected from the three modules in Cluster 2 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Identification of floral fragrance-related genes by WGCNA. (A) Clustering dendrograms of genes and module detecting. (B) Eigengene dendrogram and adjacency heatmap. (C) Heat map of the correlation between floral fragrant compounds and gene modules. Heatmap colors represent the correlation level, the numbers out and in parentheses are correlation coefficient r and P value, respectively. Numbers in bottom color label represent number of genes within module. (D) Bar plots indicate number of significantly correlated genes of each compound within each module (threshold |GS| ≥ 0.9 & |MM| ≥ 0.8). WGCNA, weighted gene co-expression network analysis.

The module-trait relationships heatmap illustrates the associations between the modules and the nine previously mentioned floral fragrance compounds. Five compounds showed an extremely significant correlation (P ≤ 0.001) with the turquoise module, four with the brown module, and four with the yellow module (Fig. 3C). In particular, the turquoise module exhibited exceptionally high correlations (r ≥ 0.9) with geraniol and phenylacetic acid, whereas the brown module displayed a similarly strong correlation with caryophyllene alpha-oxide. Furthermore, the yellow module showed very high correlations with alpha-terpinene and pulegone.

Subsequently, by applying the thresholds of |GS| ≥ 0.9 and |MM| ≥ 0.8, we identified genes that were significantly correlated with each compound within their respective modules. This selection process refined the gene set associated with floral compounds to a total of 574 genes. The results are summarized in Fig. 3D. Within the benzene-containing compounds, 59, 94, and 176 genes were associated with methyl cinnamate, phenylacetic acid, and 2-phenylethanol, respectively (Fig. 3D). In the terpenoid category, 57, 99, 101, 121, 130, and 201 genes were linked to alpha-cedrene, limonene oxide, pulegone, caryophyllene alpha-oxide, alpha-terpinene, and geraniol, respectively (Fig. 3D).

Prediction of key candidate genes via differential expression

Based on gene expression levels, the 574 floral fragrance-related genes identified through WGCNA were classified into high (FPKM ≥ 100), medium (100 > FPKM ≥ 10), and low (10 > FPKM ≥ 1) expression groups. During the collection phase, the petals exhibited an elevated state of floral fragrance production, indicating that genes with high expression and significant differential expression at this stage may possess potential biological significance in the biosynthesis of floral fragrance. A total of 123 genes were found to be highly expressed across CG, DM, and QX (Fig. 4A). Among these, six genes—NUDIX1, NUDIX2, GERD, F3GT1, UGT74AC1, and RVE8—demonstrated a log2FoldChange > 6 when comparing CG, DM, and QX to CK (Fig. 4B; Table 2). Recent studies have identified a rose nudix hydrolase as a key enzyme in geraniol biosynthesis14,37,38. Therefore, the candidate gene NUDIX1, annotated as a nudix hydrolase, may contribute to the biosynthesis of terpenoid floral fragrance compounds. It is further hypothesized that the transcripts of NUDIX2 may also be associated with floral fragrance production. Additionally, germacrene D synthase (GERD) has been recognized as a terpene synthase gene involved in sesquiterpenoid biosynthesis39. Interestingly, although no direct link has been reported between RVE8, F3GT1, and UGT74AC1 and floral fragrance, these genes were highly expressed in fragrant rose petals.

Fig. 4.

Identification of candidate genes from highly expressed genes. (A) Venn diagram of highly expressed genes (FPKM ≥ 100). (B) Upset plot of highly expressed gene. DM, Damascena; QX, Qin Xiang; CG, Crimson Glory. DM_lg2FC, highly expressed gene with log2FoldChange > 6 in DM compared to Iceberg (CK). QX_lg2FC, highly expressed gene with log2FoldChange > 6 in QX compared to CK. CG_lg2FC, highly expressed gene with log2FoldChange > 6 in CG compared to CK.

Table 2.

Prediction of fragrance-related candidate genes via differential expression and annotations.

| No. | Gene ID | Symbol | Length | Description | Annotationa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly expressed gene | |||||

| 1 | LOC112200430 | NUDIX1 | 691 | Geranyl diphosphate phosphohydrolase; nudix hydrolase 1 | |

| 2 | LOC112189710 | NUDIX2 | 740 | Geranyl diphosphate phosphohydrolase | rcn00902 |

| 3 | LOC112195178 | RVE8 | 1371 | Protein REVEILLE 8 | |

| 4 | LOC112198073 | F3GT1 | 1857 | Anthocyanidin 3-O-galactosyltransferase | |

| 5 | LOC112197891 | UGT74AC1 | 1629 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 74E1-like | |

| 6 | LOC112167657 | GERD | 1895 | (-)-Germacrene D synthase | GO:0010334; GO:0010333; GO:0016114; rcn00909 |

| Annotated as terpenoid-related genes | |||||

| 7 | LOC112202294 | AFS1 | 2097 | Alpha-farnesene synthase | GO:0010334; GO:0010333; GO:0046246; rcn00909 |

| 8 | LOC112202298 | AFS2 | 1951 | (E, E)-alpha-farnesene synthase-like | GO:0010334; GO:0010333; GO:0046246 |

| 9 | LOC112168955 | CYP82G1 | 1661 | Trimethyltridecatetraene/Dimethylnonatriene synthase | GO:0016114; GO:0046246 |

| 10 | LOC112169394 | HMG1 | 2281 | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase | GO:0016114; rcn00900 |

| 11 | LOC112168397 | NCED2 | 2215 | 9-Cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 2 | GO:0016114; GO:0016106 |

| 12 | LOC112188552 | CCD7 | 2142 | Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 7 | GO:0016114; GO:0016106 |

| 13 | LOC112190337 | PSY | 1329 | Phytoene synthase | GO:0016114 |

| 14 | LOC112188852 | ICMEL2 | 2142 | Isoprenylcysteine alpha-carbonyl methylesterase 2 | rcn00900 |

| 15 | LOC112170113 | MAD1 | 1213 | Probable mannitol dehydrogenase | rcn00902 |

| 16 | LOC112187218 | MAD2 | 1358 | Probable mannitol dehydrogenase | rcn00902 |

| Annotated as benzenoid/phenylpropanoid-related genes | |||||

| 17 | LOC112174126 | DET2 | 1139 | Very-long-chain enoyl-CoA reductase-like | GO:0042537 |

| 18 | LOC112174127 | DET3 | 1184 | Very-long-chain enoyl-CoA reductase-like | GO:0042537 |

| 19 | LOC112178629 | ICS2 | 2058 | Isochorismate synthase 2 | GO:0042537 |

| 20 | LOC112191949 | PAL1 | 2097 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1 | GO:0042537; GO:0009699; rcn00940 |

| 21 | LOC112199520 | UGT74B1 | 1664 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 74B1 | GO:0042537 |

| 22 | LOC112179508 | MYB330 | 1292 | Myb-related protein 33 | GO:0042537; GO:0009699 |

| 23 | LOC112165480 | GST | 1109 | Probable glutathione S-transferase | GO:0042537 |

| 24 | LOC112187991 | CAD1 | 1420 | Probable cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 | GO:0009699; rcn00940 |

| 25 | LOC112201401 | HST | 1792 | Shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase | GO:0009699; rcn00940 |

| 26 | LOC112168748 | PCBER1 | 1271 | Phenylcoumaran benzylic ether reductase | GO:0009699 |

| 27 | LOC112185407 | LAC15 | 2100 | Laccase-15 | GO:0009699 |

| 28 | LOC112173581 | CSE | 1700 | Caffeoylshikimate esterase | rcn00940 |

| 29 | LOC112189050 | PER25 | 1140 | Peroxidase 25 | rcn00940 |

| 30 | LOC112201637 | PER47 | 1218 | Peroxidase 47 | rcn00940 |

| 31 | LOC112183965 | PER63 | 1508 | Peroxidase 63 | rcn00940 |

aGO:0010333: Terpene synthase activity; GO:0010334: Sesquiterpene synthase activity; GO:0016114: Terpenoid biosynthetic process; GO:0046246:Terpene biosynthetic process; GO:0016106: Sesquiterpenoid biosynthetic process; GO:0009699: Phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process; GO:0042537: benzene-containing compound metabolic process; rcn00900: Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis; rcn00902: Monoterpenoid biosynthesis; rcn00909: Sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis ; rcn00940: Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis.

Prediction of key candidate genes via GO and KEGG annotation

An analysis of the floral fragrance-related genes (574 DEGs) was conducted using GO and KEGG. The GO analysis revealed significant enrichment in 103 Biological Process (BP), 50 Molecular Function (MF), and 5 Cellular Component (CC) terms. Notably, the top ten BP terms were extremely significant (P < 0.001), with the top five being the auxin-activated signaling pathway, response to auxin, cellular response to auxin stimulus, peptidyl-threonine phosphorylation, and peptidyl-threonine modification (Fig. 5A). These findings suggest that auxin-related biological processes and peptidyl-threonine phosphorylation may contribute to the regulation of floral fragrance formation. The MF terms that were extremely significantly enriched included glucosyltransferase activity and UDP-glucosyltransferase activity, both of which may be involved in floral fragrance formation. In the CC category, two GO terms, anchored component of membrane and anchored component of plasma membrane, were found to be highly significantly enriched (P < 0.01), suggesting their potential involvement in floral fragrance formation. The KEGG enrichment analysis identified 85 enriched pathways, with seven pathways showing significant enrichment (P < 0.05). Notably, plant hormone signal transduction, carotenoid biosynthesis, starch and sucrose metabolism, and cysteine and methionine metabolism were highly significantly enriched pathways (Fig. 5B), indicating their possible critical roles in floral scent formation.

Fig. 5.

GO and KEGG pathway analysis of floral fragrance-related genes. (A) GO analysis. (B) KEGG pathway analysis. GO, gene ontology; KEGG, Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes.

Given that our target compounds included terpenoids and benzene-containing compounds, which are common components of floral fragrances5,8, we predicted candidate genes based on relevant GO and KEGG annotations. First, eight genes were selected based on GO annotations related to terpenoids (Table 2). Among these, the genes AFS1, AFS2, and GRED were annotated with terpene synthase activity (GO:0010333) and sesquiterpene synthase activity (GO:0010334). Additionally, AFS1, AFS2, and CYP82G1 were annotated with the terpene biosynthetic process (GO:0046246). The genes NCED2, HMG1, CCD7, PSY, CYP82G1, and GRED were annotated with the terpenoid biosynthetic process (GO:0016114), with NCED2 and CCD7 also being annotated with the sesquiterpenoid biosynthetic process (GO:0016106). Furthermore, 11 genes were selected based on GO annotation related to benzenoid/phenylpropanoids (Table 2). Among these, ICS2, MYB330, PAL1, GST DET2, DET3, and UGT74B1 were annotated as involved in the benzene-containing compound metabolic process (GO:0042537). PYRC5, MYB330, PAL1, LAC15, HST, and CAD1 were annotated as involved in the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process (GO:0009699). Second, seven genes were selected based on KEGG annotations related to terpenoid biosynthesis, as detailed in Table 2. Among these, NUDIX1, MAD1, and MAD2 were annotated as involved in monoterpenoid biosynthesis, GERD and AFS1 were associated with sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis, while HMG1 and ICMEL2 were linked to terpenoid backbone biosynthesis. Additionally, seven genes associated with phenylpropanoid biosynthesis were selected, including PER25, PER47, PER63, PAL1, HST, CSE, and CAD1 (Table 2).

A comprehensive literature review of the candidate genes revealed that several, including AFS40, GRED39, CCD111, CYP82G141, and HMG142, have been previously associated with terpenoid-floral scents. This suggests that AFS1, AFS2, and CCD7 may also be related to floral fragrance. Furthermore, genes including PAL143,44, CAD145, PCBER46,47, LAC48, and CSE49 have been linked to phenylpropanoid/benzenoid-floral scents.

Prediction of key candidate genes via PPI network analysis

The PPI network elucidates the relationships among these genes or proteins, offering insights into the significant molecular regulatory network within rose petals50. The topological analysis of the PPI network facilitates the identification of hub genes. A PPI network was subsequently constructed to predict hub genes by mapping the 574 DEGs selected via WGCNA onto the STRING database. The results demonstrated that 533 proteins were successfully mapped, achieving an efficiency rate of 92.86%. The PPI network generated 292 interaction pairs (Fig. 6A). Scores derived from topological algorithms using CytoHubba were assigned to each node within the PPI network, with the MCC, DMNC, MNC, and Bottleneck scores ranking the genes across the entire network. A Venn analysis of the four algorithms revealed 33 overlapping genes (Figs. 6B-C). Additionally, the MCODE algorithm was employed to extract 11 subnetworks within the PPI network (Fig. 6D and Table S3). The subsequent integration of CytoHubba with MCODE identified 21 hub genes (Fig. 6E; Table 3).

Fig. 6.

Identification of candidate genes from floral fragrance-related genes using PPI network analysis. (A) Visualization of entire PPI network. Lines indicate protein-protein interactions and proteins with a degree above three were visualized in detail. (B) Venn diagram shows the overlap of four different algorithms of cytoHubba. MCC, Maximal clique centrality; MNC, Maximum neighborhood component; DMNC, Density of MNC. (C) PPI network maps about 33 overlapping genes. (D) The significant module identified from PPI network via MCODE. (E) Venn diagram shows 21 hub genes obtained by combining cytoHubba and MCODE algorithms. PPI, Protein-protein interaction. MCODE, Molecular Complex Detection.

Table 3.

Fragrance-related hub genes from PPI network analysis combining the CytoHubba and MCODE.

| No. | Gene ID | Symbol | Length | Description | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LOC112165291 | APR3 | 1842 | 5’-Adenylylsulfate reductase 3 | rcn00920(Sulfur metabolism); GO:0000096(sulfur amino acid metabolic process) |

| 2 | LOC112165974 | TPS1 | 3632 | Alpha, alpha-trehalose-phosphate synthase [UDP-forming] 1 | rcn01003(Glycosyltransferases); rcn00500(Starch and sucrose metabolism) |

| 3 | LOC112172366 | APK1 | 1660 | Adenylyl-sulfate kinase 1 | rcn00230(Purine metabolism); rcn00920(Sulfur metabolism); GO:0000096(sulfur amino acid metabolic process) |

| 4 | LOC112176478 | HMGCL | 1591 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase | rcn04146(Peroxisome); rcn00280(Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation); rcn00650(Butanoate metabolism) |

| 5 | LOC112178629 | ICS2 | 2058 | Putative isochorismate synthase |

rcn00130(Ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis); GO:0019438(Aromatic compound biosynthetic process) |

| 6 | LOC112189843 | LNK2 | 2947 | Protein LNK2 isoform X1 | GO:0019438(aromatic compound biosynthetic process) |

| 7 | LOC112191949 | PAL1 | 2561 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1 |

rcn00940(Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis); rcn00360(Phenylalanine metabolism); GO:0006558(L-phenylalanine metabolic process); GO:0019438(Aromatic compound biosynthetic process) |

| 8 | LOC112192949 | LNK3 | 1702 | Protein LNK3 | |

| 9 | LOC112196306 | PKS1 | 1959 | Phytochrome kinase substrate 1 | |

| 10 | LOC112198236 | SUS2 | 2841 | Sucrose synthase 2-like | rcn01003(Glycosyltransferases); rcn00500(Starch and sucrose metabolism) |

| 11 | LOC112199841 | BAG5 | 1150 | BAG family molecular chaperone regulator | |

| 12 | LOC112195178 | RVE8 | 1371 | Protein REVEILLE 8 | GO:0019438(Aromatic compound biosynthetic process) |

| 13 | LOC112195332 | PCUBI4 | 1418 | Polyubiquitin | rcn04121(Ubiquitin system); rcn04120(Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis) |

| 14 | LOC112185897 | PRE1 | 968 | Transcription factor PRE1 | GO:0019438(Aromatic compound biosynthetic process) |

| 15 | LOC112199892 | PRE6 | 1256 | Transcription factor PRE6 | GO:0019438(Aromatic compound biosynthetic process) |

| 16 | LOC112176267 | FBA | 4617 | Putative fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | GO:0019438(Aromatic compound biosynthetic process) |

| 17 | LOC112180515 | EARLI1 | 937 | Lipid transfer protein EARLI 1 | |

| 18 | LOC112189138 | FLA2 | 1590 | Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein 2 | |

| 19 | LOC112167529 | LOC112167529 | 1444 | Uncharacterized protein | |

| 20 | LOC112174760 | LOC112174760 | 1511 | Uncharacterized protein | |

| 21 | LOC112183447 | LOC112183447 | 3834 | Uncharacterized protein |

Notably, among the 21 hub genes, several, including PAL1, ICS2, and RVE8, had been previously identified in the candidate gene set through differential expression or functional annotation. Furthermore, three genes remain uncharacterized: LOC112167529, LOC112174760, and LOC112183447. Concurrently, we conducted a literature review on the roles of these hub genes in floral fragrance formation. The results reveal that the hub gene PAL1 has been extensively studied in relation to floral fragrance, whereas the other genes have not been thoroughly examined in this context. We propose that several of these genes may act as upstream regulatory genes or participate in the synthesis of precursor compounds essential for floral scent, thereby exerting an indirect influence on fragrance formation. Amino acid pathways are recognized as one of the biosynthetic origins of floral scent precursor compounds51. Specifically, branched-chain amino acids (L-valine, L-isoleucine, and L-leucine), aromatic amino acids (L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine, and L-phenylalanine), and L-methionine are known contributors to plant scent formation52. Consistent with our hypothesis, some of the candidate genes were annotated within the amino acid pathways. Thus, genes involved in amino acid metabolism, such as APR3, APK1, and HMGCL, may also play roles in the production of floral scent. Additionally, hub genes such as ICS2, FBA, LNK2, PAL1, RVE8, PRE1, and PRE6, which were annotated with aromatic compound biosynthetic process, may impact the development of phenylpropanoid/benzenoid-floral scents (Table 3).

qRT-PCR validation of differential expression

To validate the RNA-seq data, we selected 16 genes for qRT-PCR analysis. These genes were confirmed as being significantly upregulated in the three fragrant roses compared with those in the scentless rose, confirming the trends identified in the RNA-Seq dataset (Fig. S5A). Linear fitting of RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR data was performed using the R software. The expression values were log2-transformed. The RNA-seq and qRT-PCR results demonstrated a high consistency, with a regression slope of 0.712 and an R2 of 0.84 (Fig. S5B). These regression outcomes confirm the credibility and accuracy of the RNA-seq data.

Conclusion

Nine principal floral fragrance compounds were selected by comparing metabolic differences. Subsequently, 574 genes related to floral fragrance were screened from DEGs using WGCNA. To further refine the set of fragrance-related genes, various methods were employed to predict candidate genes. Firstly, we predicted a total of 31 candidate genes through differential expression, GO annotation, and KEGG annotation. Among these, NUDIX1, NUDIX2, GERD, AFS1, AFS2, CYP82G1, HMG1, NCED2, CCD7, PSY, ICMEL2, MAD1, and MAD2 are potentially involved in terpenoid biosynthesis. Additionally, DET2, DET3, ICS2, PAL1, UGT74B1, MYB330, GST, CAD1, HST, PCBER1, LAC15, CSE, PER25, PER47, and PER63 may be related to benzenoid/phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Furthermore, we screened out 21 hub genes through computational prediction using CytoHubba and MCODE. Among these hub genes, ICS2, FBA, LNK2, PAL1, RVE8, PRE1, and PRE6 are potentially related to benzenoid/phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Notably, ICS2, PAL1, and RVE8 were predicted by multiple methods. Additionally, three novel genes, LOC112167529, LOC112174760, and LOC112183447, with currently unknown functions, may contribute to floral scent formation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the funding support of the Chongqing Postdoctoral Science Foundation (cstc2021jcyj-bshX0066), the funding support of Basic Scientific Research Projects of 2023 Chongqing Financial Special Fund (cqaas2023sjczqn008), the funding support of the Project of Chongqing Technology Innovation and Application (CSTB2024TIAD-LUX0004), the funding support of Shandong Technology Innovation Guidance Program (Shandong Chongqing Science and Technology Cooperation)(2024LYXZ024,)the funding support of Municipal Finance Special Fund of Chongqing Academy of Agricultural Sciences (NKY-2022AB029), and grant support from Chongqing Human Resources and Social Security Bureau (Projects Foundation of Abroad-Studying and Returning Personnel).

Author contributions

Chan Xu: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Yuan Chen: Validation, Resources, Methodology. Zongli Hu: Data curation, Validation. Qiaoli Xie: Validation, Resources, Conceptualization. Hang Guo: Investigation, Data curation. Guoping Chen: Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Shibing Tian: Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information files. The original RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive, accession number: PRJNA1276230.

Declarations

Ethics statement

The authors declare that they have followed all the rules of ethical conduct regarding originality, data processing and analysis, duplicate publication, and biological material.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chan Xu, Email: xchan8808@163.com.

Guoping Chen, Email: chenguoping@cqu.edu.cn.

Shibing Tian, Email: 2508436730@qq.com.

References

- 1.Katekar, V. P., Rao, A. B. & Sardeshpande, V. R. Review of the Rose essential oil extraction by hydrodistillation: an investigation for the optimum operating condition for maximum yield. Sustainable Chem. Pharm.29, 100783 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demirbolat, I. et al. Effects of orally consumed Rosa Damascena mill. hydrosol on hematology, clinical chemistry, lens enzymatic activity, and lens pathology in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Molecules24(22), 4069 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mileva, M. et al. Rose flowers—A delicate perfume or a natural healer? Biomolecules11(1), 127 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudareva, N. & Pichersky, E. Biochemical and molecular genetic aspects of floral scents. Plant Physiol.122(3), 627–634 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gang, D. R. Evolution of flavors and scents. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol.56(1), 301–325 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhavan, H. & Mehrizi, R. Z. Effects of Damask rose (Rosa Damascena Mill.) extract on chemical, microbial, and sensory properties of Sohan (an Iranian Confection) during storage. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control. 3(3). (2016).

- 7.Sadraei, H., Asghari, G. & Emami, S. Inhibitory effect of Rosa Damascena mill flower essential oil, geraniol and citronellol on rat ileum contraction. Res. Pharm. Sci.8(1), 17 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhlemann, J. K., Klempien, A. & Dudareva, N. Floral volatiles: from biosynthesis to function. Plant. Cell. Environ.37(8), 1936–1949 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Channelière, S. et al. Analysis of gene expression in rose petals using expressed sequence tags. FEBS Lett.515(1–3), 35–38 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guterman, I. et al. Generation of phenylpropanoid pathway-derived volatiles in transgenic plants: Rose alcohol acetyltransferase produces phenylethyl acetate and benzyl acetate in petunia flowers. Plant Mol. Biol.60(4), 555–563 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, F. C. et al. Substrate promiscuity of RdCCD1, a carotenoid cleavage oxygenase from Rosa damascena. Phytochemistry70(4), 457–464 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura, N. et al. Genome structure of Rosa multiflora, a wild ancestor of cultivated roses. DNA Res.25(2), 113–121 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roccia, A. et al. Biosynthesis of 2-phenylethanol in rose petals is linked to the expression of one allele of RhPAAS. Plant Physiol.179(3), 1064–1079 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnard, J. L. et al. Biosynthesis of monoterpene scent compounds in roses. Science349(6243), 81–83 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scalliet, G. et al. Biosynthesis of the major scent components 3, 5-dimethoxytoluene and 1, 3, 5-trimethoxybenzene by novel rose O-methyltransferases. FEBS Lett.523(1–3), 113–118 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scalliet, G. et al. Role of petal-specific orcinol O-methyltransferases in the evolution of rose scent. Plant Physiol.140(1), 18–29 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scalliet, G. et al. Scent evolution in Chinese roses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.105(15), 5927–5932 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng, L. et al. Flowery odor formation revealed by differential expression of monoterpene biosynthetic genes and monoterpene accumulation in rose (Rosa rugosa Thunb). Plant Physiol. Biochem.75, 80–88 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiehn, O. & Kind, T. Metabolite profiling in blood plasma. In Metabolomics: Methods and Protocols (ed. Weckwerth, W.) 3–17 (Humana Press, 2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Fiehn, O. et al. Quality control for plant metabolomics: reporting MSI-compliant studies. Plant J.53(4), 691–704 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasilev, N. et al. Structured plant metabolomics for the simultaneous exploration of multiple factors. Sci. Rep.6(1), 37390 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zelena, E. et al. Development of a robust and repeatable UPLC – MS method for the long-term metabolomic study of human serum. Anal. Chem.81(4), 1357–1364 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Want, E. J. et al. Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat. Protoc.8(1), 17–32 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol.14, 1–13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalitha, S. Primer premier 5. Biotech Software & Internet Report: The Computer Software Journal for Scient, 1(6), 270–272. (2000).

- 26.Sun, Y. et al. Changes in volatile organic compounds and differential expression of aroma-related genes during flowering of Rosa rugosa ‘shanxian’. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol.60, p741–751 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conart, C. et al. A cytosolic bifunctional geranyl/farnesyl diphosphate synthase provides MVA-derived GPP for geraniol biosynthesis in rose flowers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.120(19), pe2221440120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baser, K., Kirimer, N. & Tümen, G. Pulegone-rich essential oils of Turkey. J. Essent. Oil Res.10(1), 1–8 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrakis, E. A. et al. Quantitative determination of pulegone in pennyroyal oil by FT-IR spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem.57(21), 10044–10048 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheljazkov, V. D. et al. Distillation time alters essential oil yield, composition, and antioxidant activity of male Juniperus scopulorum trees. J. Oleo Sci.61(10), 537–546 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu, Z. et al. Chemical compositions and functions of camphor tree volatiles. Caribb. J. Sci.51(3), 519–526 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu, Y. J. et al. Antityrosinase and antimicrobial activities of 2-phenylethanol, 2-phenylacetaldehyde and 2-phenylacetic acid. Food Chem.124(1), 298–302 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirata, H., Ohnishi, T. & Watanabe, N. Biosynthesis of floral scent 2-phenylethanol in rose flowers. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.80(10), 1865–1873 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Bhatia, S. et al. Fragrance material review on methyl cinnamate. Food Chem. Toxicol.45(1), S113–S119 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umer, M. J. et al. Identification of key gene networks controlling organic acid and sugar metabolism during watermelon fruit development by integrating metabolic phenotypes and gene expression profiles. Hortic. Res.7(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Wang, R. et al. Integrative analyses of metabolome and genome-wide transcriptome reveal the regulatory network governing flavor formation in kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). New Phytol.233(1), 373–389 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergman, M. E., Bhardwaj, M. & Phillips, M. A. Cytosolic geraniol and citronellol biosynthesis require a nudix hydrolase in rose-scented geranium (Pelargonium graveolens). Plant J.107(2), 493–510 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouwmeester, H. et al. The role of volatiles in plant communication. Plant J.100(5), 892–907 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guterman, I. et al. Rose scent: genomics approach to discovering novel floral fragrance–related genes. Plant. Cell.14(10), 2325–2338 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan, E. & Othman, R. Characterization of α-farnesene synthase gene from Polygonum minus. (2012).

- 41.Lee, S. et al. Herbivore-induced and floral homoterpene volatiles are biosynthesized by a single P450 enzyme (CYP82G1) in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.107(49), 21205–21210 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manina, A. S. & Forlani, F. Biotechnologies in perfume manufacturing: metabolic engineering of terpenoid biosynthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24(9), 7874 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bera, P., Mukherjee, C. & Mitra, A. Enzymatic production and emission of floral scent volatiles in Jasminum sambac. Plant Sci.256, 25–38 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan, R. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Polianthes tuberosa during floral scent formation. Plos One. 13(9), e0199261 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, T. et al. Comprehensive analysis of endogenous volatile compounds, transcriptome, and enzyme activity reveals PmCAD1 involved in cinnamyl alcohol synthesis in Prunus mume. Front. Plant Sci.13, 820742 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atkinson, R. G. Phenylpropenes: occurrence, distribution, and biosynthesis in fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem.66(10), 2259–2272 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koeduka, T. et al. Eugenol and isoeugenol, characteristic aromatic constituents of spices, are biosynthesized via reduction of a coniferyl alcohol ester. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.103(26), 10128–10133 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang, J. et al. Laccase production and differential transcription of laccase genes in Cerrena sp. in response to metal ions, aromatic compounds, and nutrients. Front. Microbiol.6, 1558 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim, J. Y. et al. Altered profile of floral volatiles and lignin content by down-regulation of caffeoyl Shikimate esterase in Petunia. BMC Plant Biol.23(1), 210 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen, B. et al. Identifying protein complexes and functional modules—from static PPI networks to dynamic PPI networks. Brief. Bioinform.15(2), 177–194 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dudareva, N. et al. Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytol.198(1), 16–32 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maoz, I., Lewinsohn, E. & Gonda, I. Amino acids metabolism as a source for aroma volatiles biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol.67, 102221 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the supplementary information files. The original RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive, accession number: PRJNA1276230.