Abstract

The composition of the distal ileum microbiota and the impact of fecal exposure during intracorporeal urinary diversion (ICUD) on gastrointestinal (GI) complications remain unclear. This study included 146 patients with bladder cancer who underwent ICUD without bowel preparation and received only a single day of antibiotic prophylaxis. Fecal samples were collected directly from the distal ileum during surgery, and ascitic fluid was obtained postoperatively from abdominal drains. Among the patients, 129 (88.3%) had minimal microbial growth in ileal feces, while 17 (11.7%) showed significant colonization. The most commonly identified organisms were Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, and Candida. The incidence of GI complications was significantly higher in patients with positive ileal fecal cultures compared to those with no detectable growth (39.4% vs. 7.7%, P < 0.001), and even more pronounced in patients with positive ascitic cultures (72.5% vs. 11.3%, P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis identified positive ascitic cultures as an independent predictor of GI complications. Additionally, frailty was significantly associated with the presence of microbial growth in ascitic fluid. These findings suggest that, although the distal ileal microbiota is largely suppressed under short-term antibiotic prophylaxis, the presence of intra-abdominal bacteria or fungi is strongly linked to postoperative GI complications, including ileus. Frailty may contribute to microbial dysbiosis and the persistence of intra-abdominal pathogens, particularly Enterococcus and Enterobacter species.

Keywords: Infection, Cystectomy, Ileus, Microbiome, Bowel preparation, Antibiotic prophylaxis

Subject terms: Microbiology, Urology

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) complications, such as postoperative ileus (POI) and intra-abdominal infections (IAI), are common following radical cystectomy (RC), with incidence rates ranging from 14 to 29%1–3. Traditionally, to minimize fecal contamination and reduce the risk of IAI and anastomotic leakage, patients undergoing intestinal surgery have received fasting, mechanical and oral bowel preparation, and intraoperative irrigation of the isolated ileum during urinary diversion4. However, the introduction of robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC), particularly with intracorporeal urinary diversion (ICUD) and enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, has led to the routine omission of bowel preparation. Previous studies in urologic surgery have shown no additional benefit from preoperative mechanical bowel preparation for intestinal urinary diversion5,6. RARC with ICUD (iRARC) under ERAS has been associated with faster bowel recovery and reduced GI complications7–9 despite concerns that omitting fasting, bowel preparation, and washing of the isolated ileum may increase fecal contamination and subsequent IAI. Therefore, we introduced iRARC with ERAS to reduce GI complications. Contrary to our expectations, a substantial rate of POI was observed even after iRARC, especially in frail patients with low G-8 scores10, and the ERAS protocol did not reduce POI in frail patients9. Recent studies have revealed frailty-related microbial changes and antibiotic resistance11,12. Thus, we hypothesized that there are limits to preventing GI complications through surgical and perioperative improvements alone, and that ongoing complications may be due to frailty and/or abdominal contamination.

Effective perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis can reduce IAI after ICUD. Therefore, it is important to develop antibiotic regimens tailored to the microbiota of the distal ileum and their antibiotic sensitivities. However, guidelines for perioperative prophylaxis in RARC currently show inconsistencies13,14 owing to the lack of specific evidence derived from urological surgeries regarding the microbiota of the distal ileum15 and the actual impact of fecal exposure during ICUD on GI complications.

This study identified the cultivable microbiota of the distal ileum and evaluated their impact on postoperative GI complications in patients with bladder cancer undergoing iRARC.

Results

Baseline and perioperative characteristics

In total, 146 patients with bladder cancer who underwent iRARC were recruited. Most patients (96%) had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 1 or 2. There were 46 patients with frailty (Geriatric-8 score ≤ 13) (31.5%). A total of 119 patients (81.5%) underwent ERAS. A total of 124 (84.9%) and 22 (15.1%) patients received an ileal conduit and a neobladder, respectively. There were 41 (27.4%) patients experienced GI complications, including 37 (25.3%) with POI and four (2.7%) with symptomatic peritonitis and/or abscesses. The other covariates are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline and perioperative characteristics.

| Characteristics | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| (n = 146) | |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 73 (67–77) |

| Median BMI, kg/m2 (IQR) | 22.3 (20.6–24.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 113 (77.4) |

| Female | 33 (22.6) |

| ASA, n (%) | |

| 1 | 56 (38.4) |

| 2 | 84 (57.5) |

| 3 | 6 (4.1) |

| Previous abdominal surgery, n (%) | 38 (26.0) |

| Frailty (G-8 score ≤ 13), n (%) | 46 (31.5) |

| Preoperative use of proton pump inhibitor, n (%) | 22 (15.1) |

| Preoperative use of H2 blocker | 6 (4.1) |

| Antibiotic use within 3 months | 12 (8.2) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 120 (82.2) |

| Implementation of ERAS, n (%) | 119 (81.5) |

| Operative time, median (IQR), min | 431 (402–498) |

| Intestinal tract reconstruction time, median (IQR), min | 38 (31–48) |

| EBL, median (IQR), mL | 200 (100–300) |

| Intraoperative crystalloid administration, median (IQR), mL | 2500 (2200–3000) |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 4 (2.7) |

| Diversion type, n (%) | |

| Ileal conduit | 124 (84.9) |

| Ileal neobladder | 22 (15.1) |

| pT3 or higher, n (%) | 40 (27.4) |

| pN positive, n (%) | 19 (13.0) |

| Gastrointestinal Complications, n (%) | 41 (27.4) |

| Postoperative ileus | 37 (25.3) |

| Intra-abdominal infections (Peritonitis / abscess) | 4 (2.7) |

IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; EBL, estimated blood loss.

Colony quantities in cultured ileal feces and ascites

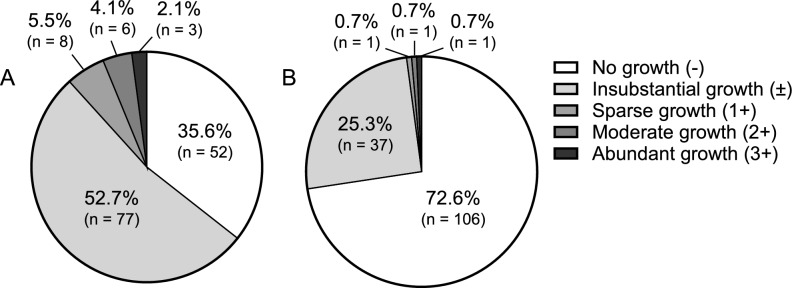

The microbiota of the ileal feces of 129 patients (88.3%) was sparse (no growth in 52 patients, 35.6%; substantial growth in 77 patients, 52.7%), whereas 17 patients (11.7%) showed substantial growth of > 1 × 103 CFU/mL. On Post Operative Day (POD) three, the ascites in 106 patients (72.6%) showed no growth, whereas 40 patients (27.4%) showed a positive culture (Fig. 1, Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Colony quantities in cultured ileal feces and ascites.The proportion of patients was classified according to the number of cultivated colonies in (A) ileal feces or (B) ascites.

Positivity of cultured ascites according to the colony quantities in cultured ileal feces

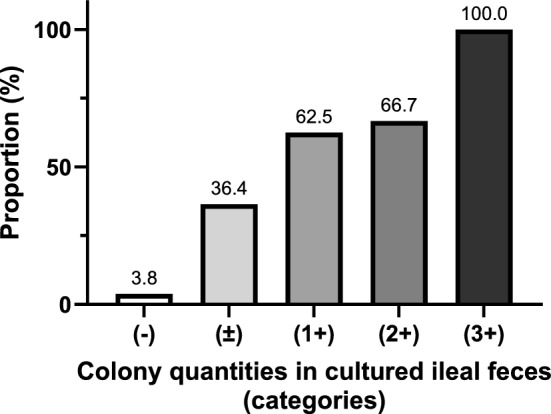

The number of positively cultured ascitic fluid was proportional to the number of colonies in the cultured ileal feces. The rates of positive ascites following no growth ( −), insubstantial growth ( ±), sparse growth (1 +), moderate growth (2 +), and abundant growth (3 +) in ileal feces were 3.8%, 36.4%, 62.5%, 66.7%, and 100%, respectively (Fig. 2, Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Positivity of cultured ascites according to the colony quantities in cultured ileal feces. The proportion of patients with positively cultured ascites was classified according to the quantification of cultivated colonies in the ileal feces.

Association between positive culture and gastrointestinal complications, and its type of bacteria and fungi

The flora of the ileal feces was dominated by Streptococcus (46.8%), Enterococcus (26.6%), Enterobacter (21.3%), Klebsiella (10.6%), and Candida (11.7%). The ascites flora were dominated by Enterococcus (37.5%), Enterobacter (22.5%), and Candida (47.5%) (Table 2). The rate of GI complications was significantly higher in patients with positive cultures than in those without fecal growth (39.4% vs. 7.7%, P < 0.001) or ascites (72.5% vs. 11.3%, P < 0.001). No IAI was observed in patients with negative fecal or ascites culture results (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between positive culture and GI complications, and its type of bacteria and fungi.

| Ileal feces, n (%) | Ascites, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positivity of culture | P value | P value | ||

| Negative (no growth) | 52/146 (35.6) | < 0.001 | 106/146 (72.6) | < 0.001 |

| GI complications | 4/52 (7.7) | 12/106 (11.3) | ||

| POI | 4 | 12 | ||

| IAI | 0 | 0 | ||

| Positive | 94/146 (64.4) | 40/146 (27.4) | ||

| GI complications | 37/94 (39.4) | 29/40 (72.5) | ||

| POI | 33 | 25 | ||

| IAI | 4 | 4 | ||

| Type of bacteria and fungi | ||||

| Gram-positive cocci | Streptococcus 44/94 (46.8) | Enterococcus 15/40 (37.5) | ||

| Enterococcus 25/94 (26.6) | Staphylococcus 2/40 (5.0) | |||

| Staphylococcus 6/94 (6.4) | ||||

| Rothia 3/94 (3.2) | ||||

| Lactcoccus 1/94 (1.1) | ||||

| Granulicatella 1/94 (1.1) | ||||

| Gram-positive bacilli | Lactbacillus 9/94 (9.6) | Corynebacterium 1/40 (2.5) | ||

| Corynebacterium 3/94 (3.2) | Anaerobic species 1/40 (2.5) | |||

| Actinomyces 1/94 (1.1) | ||||

| Gram-negative cocci | Neisseria 1/94 (1.1) | NA | ||

| Veillonella 1/94 (1.1) | ||||

| Gram-negative bacilli | Enterobacter 20/94 (21.3) | Enterobacter 9/40 (22.5) | ||

| Klebsiella 10/94 (10.6) | Escherichia 1/40 (2.5) | |||

| Escherichia 6/94 (6.4) | Pseudomonas 1/40 (2.5) | |||

| Haemophilus 5/94 (5.3) | ||||

| Citrobacter 3/94 (3.2) | ||||

| Raoultella 2/94 (2.1) | ||||

| Acinetobacter 3/94 (3.2) | ||||

| Bacteroides 1/94 (1.1) | ||||

| Hafnia 1/94 (1.1) | ||||

| Aeromonas 1/94 (1.1) | ||||

| Fungi | Candida 11/94 (11.7) | Candida 19/40 (47.5) |

GI, gastrointestinal; POI, postoperative ileus; IAI, intra-abdominal infections.

Type of bacteria and fungi in cultured ileal feces and ascites in patients with intra-abdominal infections

Four patients (2.7%) developed symptomatic peritonitis and/or abscesses (IAI). All showed positive cultures in both ileal feces and ascitic fluid. The pathogens identified included Enterobacter cloacae (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, CRE), Enterobacter aerogenes (CRE), Enterococcus faecalis, Candida glabrata, and Candida albicans. Blood culture results were consistent with the organisms found in the ileal feces and/or ascitic fluid (Table 3).

Table 3.

Type of bacteria and fungi in cultured ileal feces and ascites in patients with intra-abdominal infections.

| Patient No | Age | Sex | Medication history | Diversion type | Symptoms (POD at diagnosis) | Type of complication | Type of bacteria or fungi (ileal feces) | Type of bacteria or fungi (ascites) | Blood culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 74 | M | Steroid, anti-rheumatoid, PPI, antibiotic | Ileal conduit | Abdominal pain, fever (POD4) | Abscess, ileus, superficial SSI | Enterobacter cloacae (CRE) (3 +) | Enterobacter cloacae (CRE) ( ±) | negative |

| Enterococcus faecalis (1 +) | |||||||||

| 2 | 66 | M | Antihypertensive agent, PPI | Neobladder | Abdominal pain (POD9) | Peritonitis, abscess, ileus | Enterobacter cloacae (1 +) | Enterobacter cloacae ( ±) | Enterobacter cloacae |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (1 +) | |||||||||

| 3 | 78 | M | Antihypertensive agent, antilipidemic agent | Ileal conduit | Abdominal pain, fever (POD7) | Peritonitis | Enterobacter aerogenes (CRE) (2 +) | Enterobacter aerogenes (CRE) ( ±) | Enterobacter aerogenes (CRE) |

| γ-streptococcus ( ±) | Enterococcus faecalis ( ±) | ||||||||

| 4 | 77 | M | Anticoagulant, PPI | Ileal conduit | Fever (POD8) | Abscess | Lactococcus garvieae ( ±) | Candida glabrata ( ±) | Candida glabrata |

| Klebsiella oxytoca ( ±) | Candida albicans ( ±) |

POD, postoperative day; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SSI, surgical site infection; CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

Identification of predictors for gastrointestinal complications and positive cultured ascites

In the multivariate analysis, positively cultured ascites were significantly associated with an increased risk of GI complications (OR 4.440, 95% CI 1.530–12.90; P = 0.005) (Table 4). Frailty (OR 3.880, 95% CI 1.320–10.60; P = 0.01) and preoperative antibiotic use (OR 3.130, 95% CI 1.040–9.420; P = 0.03) were significantly associated with an elevated risk of culture-positive ascites (Table 5).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis for gastrointestinal complications.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Intercept | 0.001 (0.001–0.381) | 0.02 | ||

| Age | 1.080 (1.010–1.160) | 0.03 | 1.030 (0.955–1.110) | 0.45 |

| BMI | 0.899 (0.774–1.040) | 0.16 | ||

| Male gender | 0.759 (0.255–2.260) | 0.62 | ||

| ASA | 3.420 (1.820–12.10) | 0.008 | 2.450 (0.972–11.60) | 0.1 |

| Previous abdominal/pelvic surgery | 2.210 (0.808–6.040) | 0.12 | ||

| Preoperative use of proton pump inhibitor | 1.940 (0.679–5.510) | 0.22 | ||

| Preoperative use of H2 blocker | 2.890 (0.558–15.00) | 0.21 | ||

| Antibiotic use within 3 months | 2.100 (0.625–7.060) | 0.23 | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 1.030 (0.338–3.130) | 0.96 | ||

| pT3 or higher | 0.261 (0.055–1.220) | 0.09 | ||

| pN positive | 0.581 (0.118–2.870) | 0.51 | ||

| Operative time | 0.998 (0.992–1.005) | 0.50 | ||

| Intestinal tract reconstruction time | 0.997 (0.965–1.030) | 0.87 | ||

| Diversion type (neobladder) | 0.139 (0.017–1.090) | 0.06 | ||

| EBL | 0.999 (0.997–1.000) | 0.50 | ||

| Intraoperative crystalloid administration | 1.000 (0.999–1.000) | 0.62 | ||

| Blood transfusion | 1.400 (0.262–9.100) | 0.67 | ||

| ERAS | 0.637 (0.232–1.750) | 0.38 | ||

| Postoperative Alb | 0.277 (0.061–1.260) | 0.10 | ||

| Postoperative CRP | 1.170 (0.994–1.370) | 0.05 | ||

| Positive cultured ileal feces | 4.820 (1.540–15.10) | 0.006 | 1.750 (0.481–6.380) | 0.39 |

| Positive cultured ascites | 7.640 (3.000–19.40) | < 0.001 | 4.440 (1.530–12.90) | 0.005 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; EBL, estimated blood loss; ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; Alb, albumin; CRP, c-reactive protein.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis for positive cultured ascites.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Intercept | 0.002 (0.001–0.378) | 0.02 | ||

| Age | 1.090 (1.020–1.160) | 0.005 | 1.040 (0.973–1.110) | 0.24 |

| BMI | 0.901 (0.788–1.030) | 0.13 | ||

| Male gender | 2.220 (0.693–7.120) | 0.18 | ||

| ASA | 3.450 (1.500–7.950) | 0.003 | 1.390 (0.493–3.910) | 0.53 |

| Previous abdominal/pelvic surgery | 0.976 (0.380–2.510) | 0.96 | ||

| Preoperative use of proton pump inhibitor | 2.040 (0.735–5.640) | 0.17 | ||

| Preoperative use of H2 blocker | 3.840 (0.790–14.20) | 0.08 | ||

| Antibiotic use within 3 months | 5.650 (1.870–18.60) | 0.003 | 3.130 (1.040–9.420) | 0.03 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.619 (0.355–1.130) | 0.23 | ||

| Frailty (G-8 score ≤ 13) | 6.250 (2.570–15.20) | < 0.001 | 3.880 (1.320–10.60) | 0.01 |

| Operative time | 0.996 (0.990–1.000) | 0.18 | ||

| Intestinal tract reconstruction time | 1.000 (0.972–1.030) | 0.91 | ||

| Diversion type (neobladder) | 0.428 (0.116–1.570) | 0.20 | ||

| EBL | 1.000 (0.998–1.000) | 0.72 | ||

| Intraoperative crystalloid administration | 1.000 (0.999–1.000) | 0.56 | ||

| Blood transfusion | 1.300 (0.274–8.300) | 0.76 | ||

| ERAS | 0.762 (0.301–1.930) | 0.56 | ||

| Postoperative Alb | 0.457 (0.125–1.670) | 0.23 | ||

| Postoperative CRP | 0.987 (0.864–1.130) | 0.84 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; EBL, estimated blood loss; ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; Alb, albumin; CRP, c-reactive protein.

Microbiota composition and antibiotic resistance profiles stratified by frailty

Frailty patients had a significantly higher rate of GI complications than non-frail patients (63.0% vs. 12.0%, P < 0.001). The rates of positive cultures of ileal feces (80.4% vs. 57.0%, P = 0.008) and ascites (58.7% vs. 13.0%, P < 0.001) were significantly higher in frail patients than in non-frail patients. Regarding microbiota composition, patients with frailty had higher proportions of Enterococcus (ileal feces: 37.8% vs. 19.3%; ascites: 44.4% vs. 23.1%) and Enterobacter (ileal feces: 40.5% vs. 8.8%; ascites: 29.6% vs. 7.7%) than non-frail patients (Table 6). The antibiotic susceptibility rates of Enterococcus and Enterobacter isolated from ileal feces were similar in frail and non-frail patients, while all three CRE with poor antibiotic susceptibility were isolated from frail patients (Tables S4, S5, S6). Antifungal susceptibility rates of Candida were excellent in both groups (Table S7).

Table 6.

Association between Frailty and GI complications, and its type of bacteria and fungi.

| Variable | Non-frail (n = 100) | Frail (n = 46) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI complications, n (%) | 12 (12.0) | 29 (63.0) | < 0.001 |

| POI | 11 (11.0) | 26 (56.5) | |

| IAI | 1 (1.0) | 3 (6.5) | |

| Positivity of cultured ileal feces, n (%) | 57 (57.0) | 37 (80.4) | 0.008 |

| Type of bacteria and fungi (ileal feces) | |||

| Gram-positive cocci | Streptococcus 34/57 (59.6) | Streptococcus 10/37 (27.0) | |

| Enterococcus 11/57 (19.3) | Enterococcus 14/37 (37.8) | ||

| Staphylococcus 4/57 (7.0) | Staphylococcus 2/37 (5.4) | ||

| Rothia 3/57 (5.3) | |||

| Lactcoccus 1/57 (1.8) | |||

| Granulicatella 1/57 (1.0) | |||

| Gram-positive bacilli | Lactbacillus 6/57 (10.5) | Lactbacillus 3/37 (8.1) | |

| Corynebacterium 1/57 (1.8) | Corynebacterium 2/37 (5.4) | ||

| Actinomyces 1/57 (1.8) | |||

| Gram-negative cocci | Neisseria 1/57 (1.8) | ||

| Veillonella 1/57 (1.8) | |||

| Gram-negative bacilli | Enterobacter 5/57 (8.8) | Enterobacter 15/37 (40.5) | |

| Klebsiella 5/57 (8.8) | Klebsiella 5/37 (13.5) | ||

| Escherichia 4/57 (7.0) | Escherichia 2/37 (5.4) | ||

| Haemophilus 4/57 (7.0) | Haemophilus 1/37 (2.7) | ||

| Citrobacter 1/57 (1.8) | Citrobacter 2/37 (5.4) | ||

| Raoultella 2/57 (3.5) | Acinetobacter 1/37 (2.7) | ||

| Acinetobacter 2/57 (3.5) | Bacteroides 1/37 (2.7) | ||

| Hafnia 1/57 (3.5) | Aeromonas 1/37 (2.7) | ||

| Fungi | Candida 6/57 (10.5) | Candida 5/37 (13.5) | |

| Positivity of cultured ascites, n (%) | 13 (13.0) | 27 (58.7) | < 0.001 |

| Type of bacteria and fungi (ascites) | |||

| Gram-positive cocci | Enterococcus 3/13 (23.1) | Enterococcus 12/27 (44.4) | |

| Staphylococcus 1/13 (7.7) | Staphylococcus 1/27 (3.7) | ||

| Gram-positive bacilli | Corynebacterium 1/13 (7.7) | ||

| Anaerobic species 1/13 (7.7) | |||

| Gram-negative bacilli | Enterobacter 1/13 (7.7) | Enterobacter 8/27 (29.6) | |

| Pseudomonas 1/13 (7.7) | Escherichia 1/27 (3.7) | ||

| Fungi | Candida 6/13 (46.2) | Candida 13/27 (48.1) | |

GI, gastrointestinal; POI, postoperative ileus; IAI, intra-abdominal infections.

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to elucidate the microbiota of the distal ileum under antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who did not undergo mechanical or oral bowel preparation, using direct sampling during ICUD. As expected, the bacterial load in ileal feces was substantially suppressed by cefmetazole in most patients (88.3%). However, the presence of residual bacteria or fungi in the peritoneal cavity, as indicated by ascitic fluid cultures (27.4%), was significantly associated with POI and IAI. Notably, frailty is associated with remnant bacteria or fungi, suggesting a microbiota distinct from that of non-frail patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the cultivable microbiota of the distal ileum under antibiotic prophylaxis during ICUD and the impact of fecal exposure on postoperative GI complications.

Skipping fasting, bowel preparation, and washing of the isolated ileum might increase fecal exposure and the risk of IAI, but previous studies have shown no clear benefit of these steps before intestinal urinary diversion5,6. These findings suggest that the ileal microbiota is inherently sparse and further suppressed by perioperative antibiotics. Nevertheless, the detailed microbiota composition of the distal ileum and the appropriate prophylactic antibiotics have not been elucidated.

Generally, bacterial populations increase from approximately 104–5 cfu/mL in the duodenum to 107–8 cfu/mL in the distal ileum. The proportion of gram-positive to gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, and strictly anaerobic bacteria increases from the proximal to the distal segments of the ileum and colon16, whereas taxonomic classification has been inconsistent across studies because of differences in sample collection and analytical methodologies17,18. We believe that direct sampling of the distal ileum during ICUD is an ideal method for determining the exact microbiota of ileal feces. Given a cultivable bacterial density of approximately 104 cfu/mL in the ileum compared to 1011–1012 cfu/mL in the colon19, sample contamination is unavoidable in retrograde transcolonic sample collection procedures. Other sampling approaches, such as ileostomies, antegrade enteroscopy, capsules, and indwelling luminal catheters, represent the microbiota of the more proximal parts of the small intestine, such as the duodenum and jejunum, which are unsuitable for evaluating urinary diversion. In the present study, the cultivable microbiota of ileal feces was sparse or had no growth and was considerably less diverse than previously reported colon-like microbiota, with a dominance of anaerobic bacteria and an estimated cultivable bacterial load of approximately 106–108 cfu/mL17,18. This is consistent with a previous study that evaluated the cultivable microbiota in the distal ileum using direct sampling during RC under antibiotic prophylaxis with oral ofloxacin and metronidazole, in addition to the intravenous administration of metronidazole from the start of surgery15. These results suggest that the microbiota of the distal ileum at the time of ICUD is substantially or totally suppressed by prophylactic antibiotics; therefore, fecal exposure does not considerably increase IAI. The quantity and duration of fecal exposure during ICUD may not be associated with the rate or extent of GI complications. In the univariate analysis, the neobladder tended to have a lower risk of GI complications (OR, 0.14) than the ileal conduit, although the neobladder had a larger amount of fecal exposure and longer exposure time. This implies that the remaining pathogenic microbes are more important than the amount or duration of fecal exposure in younger non-frail patients.

Appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis is required to minimize the risk of GI complications after ICUD, although a consensus is lacking. The AUA guidelines recommend a single dose of cefazolin with alternative options, such as clindamycin plus aminoglycoside, second-generation cephalosporin, or aminopenicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor (with or without metronidazole)13. In contrast, the European Association of Urology recommends cefuroxime or an aminopenicillin/β-lactamase inhibitor plus metronidazole14. We routinely administered cefmetazole, a second-generation cephalosporin with a spectrum covering many Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Escherichia, and anaerobic bacteria20, within 24 hours without oral antibiotics. The reason for using only cefmetazole as a prophylactic antibiotic in our institute was the complexity of multiple antibiotic uses and its favorable sensitivity to anaerobic bacteria. In addition, metronidazole should be preserved for severe IAI or anaerobic infections, and antibiotic resistance should be avoided by overuse of metronidazole. As expected, Staphylococcus (6.4%), Haemophilus (5.3%), Klebsiella (10.6%), Neisseria (1.1%), Escherichia (6.4%), and anaerobic bacteria (2.2%) were suppressed in the ileal feces. In contrast, Streptococcus (46.8%), Enterococcus (26.6%), and Enterobacter (21.3%) were frequently detected, whereas the remaining Enterococcus, Enterobacter, and Candida species in the ascites appeared to be responsible for symptomatic IAI. Although IAI was observed in only 2.7% (4/146) of the patients in our cohort using a single day cefmetazole, there is room for discussion regarding the optimal duration and whether other antibiotics or antifungal drugs should be added to treat these pathogenic microbes21,22.

Although substantial bacterial or fungal growth in ileal feces and positive ascitic cultures were relatively uncommon in our cohort, their presence was strongly linked to GI complications. All four patients with IAI had positive cultures in both ileal feces and ascitic fluid, suggesting that a high concentration of microbes in the ileum and their persistence in the abdomen may lead to symptomatic IAI. Notably, positive cultures from ileal feces or ascites were associated not only with IAI but also with POI. While evidence directly connecting residual microbes in the abdomen to POI is limited, studies in general surgery have shown that prolonged ileus is often related to IAI and anastomotic leakage23. In addition, infection and local inflammatory responses, as well as bowel manipulation triggering inhibitory alpha-2 adrenergic reflexes, have been shown to contribute to POI24,25. We previously reported that a substantial rate of POI exists even after iRARC, and that frail patients with low G-8 scores have a higher risk of POI10. Moreover, the ERAS protocol did not reduce POI in frail patients after iRARC, although it enhanced bowel recovery and reduced POI in non-frail patients9. These results suggest that improving surgical techniques and perioperative management alone may not fully prevent POI, and that persistent POI could be driven by factors such as frailty and/or abdominal contamination.

One notable finding of this study is that frailty is a significant predictor of positive ascitic fluid cultures, indicating a higher risk of GI complications caused by microbial changes and antibiotic resistance. Generally, microbial changes occur naturally and continuously in the gut as a consequence of the aging of the gastrointestinal and immune system26, and exhibit a distinct composition in both healthy and frail elderly individuals11. Indeed, patients with frailty had a considerably higher proportion of Enterococcus and Enterobacter including CRE, than non-frail patients in the present study. Because frailty-related dysbiosis of the microbiota has been shown to be associated with antibiotic resistance12,27, we hypothesized that the remaining intra-abdominal pathogenic bacteria were caused by antibiotic resistance. However, our analyses of the antibiotic susceptibility rates of Enterococcus and Enterobacter isolated from ileal feces were comparable. Given that cefmetazole inherently has poor sensitivity to Enterococcus and Enterobacter, we concluded that the remaining bacteria related to frailty were mainly caused by the distinct microbiota of the distal ileum and not by antibiotic resistance.

In addition to frailty, the preoperative use of proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers has been reported to increase both bacterial and fungal growth15,28, although they were not notable predictors of GI complications or a positive culture of ascitic fluid in the present study. Previous studies have shown that preoperative antibiotic use significantly alters the gut microbiome29. Consistent with this finding, a history of antibiotic use within three months was an independent predictor of positive cultured ascites in the present study.

Consequently, the development of frailty- or gut microbiota-based targeted intervention strategies is imperative, given that our study and previous studies explain the association between frailty, gut microbiota, and GI complications30. Possible interventions are as follows: First, as the early diagnosis of frailty is indispensable to properly establish frailty-based management, we recommend geriatric assessment during initial outpatient clinic visits. Other than the G-8 score31, previous studies have reported various geriatric assessment tools and their effectiveness for radical cystectomy32. Second, prehabilitation has been applied to reduce modifiable risk factors before surgery and optimize functional status33. As we previously described, prehabilitation including optimal exercise may reduce frailty-related POI9. Third, the administration of prophylactic prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics may be effective in improving preoperative microbiota. The short-term effects of probiotics or synbiotics, such as the reduction of postoperative infections, have been explored in pancreatoduodenectomy, gastric surgery, and colorectal surgery34–36. Based on the discussion of the association between neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and the gut microbiome, a previous single-center RCT suggested that perioperative probiotic supplements could reduce postoperative infections and improve the recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients with gastric cancer receiving NAC37. Other studies have shown that NAC does not significantly change the gut microbiota38,39, whereas the composition of the gut microbiome affects the efficacy of NAC in muscle-invasive bladder cancer40. Fourth, broad-spectrum prophylaxis combined with oral antibiotics may contribute to reduced persistence of bacteria or fungi in ileal feces, ascites, and subsequent GI complications. RC under antibiotic prophylaxis with oral ofloxacin showed a lower proportion of Enterococcus and Enterobacter than our cohort, suggesting the effectiveness of oral quinolones in managing these pathogens, although they did not evaluate frailty or postoperative complications15. Broad-spectrum antibiotics targeting Enterococcus and Enterobacter may also be effective, although there are concerns about antibiotic overuse and antibiotic resistance. Regarding Candida, only one patient had symptomatic intra-abdominal candidiasis, although there was a high prevalence of Candida species in the ascitic cultures (47.5%). Because most patients with Candida positive cultures were considered clinically insignificant, routine antifungal prophylaxis was not administered at our institute. Clinical guidelines recommend empirical antifungal therapy along with appropriate drainage and/or debridement only for patients with clinical evidence of IAI and significant risk factors for candidiasis along with appropriate drainage and/or debridement41. However, the association between remnant intraperitoneal Candida spp. and POI remains unclear. Peritoneal washing after IUCD in frail patients might be effective in reducing the remaining bacteria and fungi in the abdominal space, although washing did not show a clear benefit for the overall cohort. Culture-based surveillance might be useful for selecting optimal antibiotic or antifungal agents in cases of IAI. Culture results are generally revealed after patients have symptoms and are diagnosed with GI complications. However, further studies are required to validate these findings.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center cohort study with a relatively small sample size, which might have resulted in selection bias and unmeasured confounders. Therefore, the risk factors derived from multivariate analysis should be interpreted with caution. Secondly, iRARC and direct sampling of ileal feces were performed by multiple surgeons, potentially reducing the generalizability and quality of the culture samples. In addition, the collection of ascitic fluid from the drainage bag may have introduced contamination. Third, the culture method employed in this study was a conventional technique, which is more limited in its ability to detect diverse bacterial species than the Expanded Quantitative Urine Culture (EQUC) method. Thus, it is likely that the culture method used in the present study does not reflect the full spectrum of normal flora, although this method may be sufficient for identifying pathogenic organisms. Fourth, the external validity of our findings is questionable because most patients were older, had cancer, and received prophylactic antibiotics, although most patients had no known intestinal diseases. Furthermore, measuring the actual effect of antibiotic prophylaxis administered at the start of surgery is challenging because of the lack of a control group that did not receive prophylaxis. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the microbiota of the distal ileum during ICUD, its effects on GI complications, and the association between frailty and the distinct microbiota. Further research is required to validate our findings and refine frailty-based management strategies, including microbiota-based antibiotic prophylaxis for iRARC.

In conclusion, the microbiota of the distal ileum under antibiotic prophylaxis was substantially suppressed and did not independently increase IAI. Nevertheless, the remaining intraperitoneal bacteria and fungi are closely associated with GI complications, including POI. Frailty may be associated with dysbiosis and the subsequent residual intra-abdominal bacteria, particularly Enterococcus and Enterobacter. Further research on optimal antibiotic prophylaxis for iRARC based on our findings is required.

Methods

Patient cohort

This retrospective cohort study included 146 patients who underwent iRARC at the Fujita Health University between 2019 and 2024. The primary endpoint of this study was to characterize the cultivable microbiota in the distal ileum under antibiotic prophylaxis. Secondary objectives included assessing the association between ileal microbiota and postoperative GI complications, as well as identifying related risk factors. The surgical procedures for iRARC, ERAS protocol, frailty definition, and POI criteria have been described in previous studies9,42. Frailty was assessed using the G-8 questionnaire, which includes eight items covering multiple geriatric domains and yields a score ranging from 0 to 17. Patients with a score of 13 or below were classified as frail9,10. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (authorization number: HM24-499). Due to the retrospective design, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the board at Fujita Health University. All procedures complied with the guidelines of the European Association of Urology (EAU), local regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Operative and perioperative protocols

No bowel preparations (mechanical or oral antibiotics) were administered. All patients received cefmetazole (CMZ, a second-generation cephalosporin)-based perioperative prophylaxis unless contraindicated due to allergy or a documented history of cefmetazole-resistant infection. Cefmetazole (1 g for body weight < 80 kg and 2 g for body weight ≥ 80 kg) was routinely administered at the start of surgery, every four hours during surgery (one to two times), and six hours after surgery (once). Ileal feces samples were collected approximately 15–25 cm from the ileocecal valve by swabbing the intestinal lumen with robotic forceps during ICUD. Ascitic fluid samples were obtained from the abdominal drain on POD 3.

Cultivation and identification

For microbial culture, samples from robotic forceps washing fluid and abdominal drainage fluid were inoculated onto blood agar plates and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2-enriched atmosphere for two days. If Gram staining results were negative, additional cultures were performed using HK semi-fluid agar and incubated for five days. In parallel, Brucella HK agar plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions for 5 days. Bacterial growth was assessed by experienced laboratory technicians. Species identification was carried out using the VITEK MS system (bioMérieux), which employs matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). The resulting spectra were analyzed using the VITEK MS software and the VITEK MS IVD Database version 3.0. Cultured colonies were evaluated and classified using a semi-quantitative grading system (Table S1). Bacterial growth exceeding 1 × 103 CFU/mL was defined as “substantial,” based on previously published criteria15,42.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression analysis was performed both univariate and multivariate analyses to identify predictors of GI complications and positively cultured ascites. The variables used in the analyses were age, body mass index, sex, previous abdominal surgery, preoperative use of proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, antibiotics within three months, pT stage, pN status, frailty, operative time, intestinal tract reconstruction time, diversion type, estimated blood loss, amount of crystalloid administered, blood transfusion rate, implementation of ERAS, postoperative albumin, C-reactive protein level, positive cultured ileal feces, and positive cultured ascites. Statistically significant variables in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p-value < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Manami Hamagishi for the bacterial and fungal cultivation, quantification, and identification at the local laboratory.

Author contributions

K.Z. contributed to the experimental design, data collection, and manuscript writing. T.N. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the data and manuscript.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and Supplementary Information.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-07932-4.

References

- 1.Shabsigh, A. et al. Defining early morbidity of radical cystectomy for patients with bladder cancer using a standardized reporting methodology. Eur. Urol.55, 164–174. 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.031 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuh, B. E. et al. Standardized analysis of frequency and severity of complications after robot-assisted radical cystectomy. Eur. Urol.62, 806–813. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.06.007 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djaladat, H. et al. 90-Day complication rate in patients undergoing radical cystectomy with enhanced recovery protocol: a prospective cohort study. World J. Urol.35, 907–911. 10.1007/s00345-016-1950-z (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabibi, A. et al. Bowel preparation versus no preparation before ileal urinary diversion. Urology70, 654–658. 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1107 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shafii, M., Murphy, D. M., Donovan, M. G. & Hickey, D. P. Is mechanical bowel preparation necessary in patients undergoing cystectomy and urinary diversion?. BJU Int.89, 879–881. 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02780.x (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Large, M. C. et al. The impact of mechanical bowel preparation on postoperative complications for patients undergoing cystectomy and urinary diversion. J. Urol.188, 1801–1805. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.039 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazargani, S. T. et al. Gastrointestinal complications following radical cystectomy using enhanced recovery protocol. Eur. Urol. Focus4, 889–894. 10.1016/j.euf.2017.04.003 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan, W. S. et al. Intracorporeal robot-assisted radical cystectomy, together with an enhanced recovery programme, improves postoperative outcomes by aggregating marginal gains. BJU Int.121, 632–639. 10.1111/bju.14073 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zennami, K. et al. Impact of an enhanced recovery protocol in frail patients after intracorporeal urinary diversion. BJU Int.134, 426–433. 10.1111/bju.16340 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zennami, K. et al. Risk factors for postoperative ileus after robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion. Int. J. Urol.10.1111/iju.14839 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Cosquer, G., Vergnolle, N. & Motta, J. P. Gut microb-aging and its relevance to frailty aging. Microb. Infect.26, 105309. 10.1016/j.micinf.2024.105309 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh, J., Robison, J. & Kuchel, G. A. Frailty-associated dysbiosis of human microbiotas in older adults in nursing homes. Nat. Aging2, 876–877. 10.1038/s43587-022-00289-7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lightner, D. J., Wymer, K., Sanchez, J. & Kavoussi, L. Best practice statement on urologic procedures and antimicrobial prophylaxis. J. Urol.203, 351–356. 10.1097/ju.0000000000000509 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kranz, J. et al. European association of urology guidelines on urological infections: Summary of the 2024 guidelines. Eur. Urol.86, 27–41. 10.1016/j.eururo.2024.03.035 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villmones, H. C. et al. The cultivable microbiota of the human distal ileum. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.021 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi, H., Takahashi, R., Nishi, T., Sakamoto, M. & Benno, Y. Molecular analysis of jejunal, ileal, caecal and recto-sigmoidal human colonic microbiota using 16S rRNA gene libraries and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism. J. Med. Microbiol.54, 1093–1101. 10.1099/jmm.0.45935-0 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kastl, A. J. Jr., Terry, N. A., Wu, G. D. & Albenberg, L. G. The structure and function of the human small intestinal microbiota: Current understanding and future directions. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.9, 33–45. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.07.006 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotter, P. D. Small intestine and microbiota. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol.27, 99–105. 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328341dc67 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarner, F. & Malagelada, J. R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet361, 512–519. 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12489-0 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones, R. N. Cefmetazole (CS-1170), a “new” cephamycin with a decade of clinical experience. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.12, 367–379. 10.1016/0732-8893(89)90106-5 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pariser, J. J. et al. The effect of broader, directed antimicrobial prophylaxis including fungal coverage on perioperative infectious complications after radical cystectomy. Urol. Oncol.34(121), e129–e114. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.10.007 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prunty, M. et al. National adherence to guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis for patients undergoing radical cystectomy. J. Urol.209, 329–336. 10.1097/ju.0000000000003069 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moghadamyeghaneh, Z. et al. Risk factors for prolonged ileus following colon surgery. Surg. Endosc.30, 603–609. 10.1007/s00464-015-4247-1 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holte, K. & Kehlet, H. Postoperative ileus: A preventable event. Br J Surg87, 1480–1493. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01595.x (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livingston, E. H. & Passaro, E. P. Jr. Postoperative ileus. Dig. Dis. Sci.35, 121–132. 10.1007/bf01537233 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hohman, L. S. & Osborne, L. C. A gut-centric view of aging: Do intestinal epithelial cells contribute to age-associated microbiota changes, inflammaging, and immunosenescence?. Aging Cell21, e13700. 10.1111/acel.13700 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson, P. J. et al. Associations of the skin, oral and gut microbiome with aging, frailty and infection risk reservoirs in older adults. Nat. Aging2, 941–955. 10.1038/s43587-022-00287-9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu, J. et al. Compared to histamine-2 receptor antagonist, proton pump inhibitor induces stronger oral-to-gut microbial transmission and gut microbiome alterations: A randomised controlled trial. Gut73, 1087–1097. 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330168 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modi, S. R., Collins, J. J. & Relman, D. A. Antibiotics and the gut microbiota. J. Clin. Invest.124, 4212–4218. 10.1172/jci72333 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, H. et al. A gut aging clock using microbiome multi-view profiles is associated with health and frail risk. Gut Microb.16, 2297852. 10.1080/19490976.2023.2297852 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yajima, S. & Masuda, H. The significance of G8 and other geriatric assessments in urologic cancer management: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Urol.10.1111/iju.15432 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duwe, G. et al. Radical cystectomy in patients aged < 80 years versus ≥ 80 years: analysis of preoperative geriatric assessment scores in predicting postoperative morbidity and mortality. World J. Urol.42, 552. 10.1007/s00345-024-05248-y (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minnella, E. M., Carli, F. & Kassouf, W. Role of prehabilitation following major uro-oncologic surgery: a narrative review. World J. Urol.40, 1289–1298. 10.1007/s00345-020-03505-4 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rayes, N. et al. Effect of enteral nutrition and synbiotics on bacterial infection rates after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann. Surg.246, 36–41. 10.1097/01.sla.0000259442.78947.19 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaharuddin, L., Mokhtar, N. M., Muhammad Nawawi, K. N. & Raja Ali, R. A. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of probiotics in post-surgical colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol.19, 131. 10.1186/s12876-019-1047-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kotzampassi, K. et al. A four-probiotics regimen reduces postoperative complications after colorectal surgery: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. World J. Surg.39, 2776–2783. 10.1007/s00268-015-3071-z (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu, G. et al. Effect of perioperative probiotic supplements on postoperative short-term outcomes in gastric cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Nutrition96, 111574. 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111574 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behrens, S. et al. Neoadjuvant therapy does not impact the biliary microbiome in patients with pancreatic cancer. J. Surg. Oncol.128, 271–279. 10.1002/jso.27281 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takaori, A. et al. Impact of neoadjuvant therapy on gut microbiome in patients with resectable/borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreatology23, 367–376. 10.1016/j.pan.2023.04.001 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bukavina, L. et al. Role of gut microbiome in neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in urothelial carcinoma: A multi-institutional prospective cohort evaluation. Cancer Res. Commun.4, 1505–1516. 10.1158/2767-9764.Crc-23-0479 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pappas, P. G. et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of Candidiasis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis.62, e1-50. 10.1093/cid/civ933 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pimentel, M., Saad, R. J., Long, M. D. & Rao, S. S. C. ACG clinical guideline: Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Am. J. Gastroenterol.115, 165–178. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000501 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and Supplementary Information.