Abstract

Background/Objectives

Currently, the increased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and elevated levels of dyslipidemia pose a major public health challenge. We aimed to investigate the association between dyslipidemia and H. pylori infection from the perspective of age category.

Methods

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted on 3530 non-obese and non-diabetic individuals who underwent a physical examination at the 991st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of People’s Liberation Army from January to December 2024. Physical measurements, hematological markers, and detection of H. pylori were gathered from all patients. According to the results of the detection of H. pylori, the subjects were divided into the H. pylori-positive group and the H. pylori-negative group. The correlation between H. pylori infection and blood lipid levels was compared between the two groups according to age category. Binary Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the factors influencing H. pylori infection.

Results

Among 3530 healthy subjects, 1176 cases (33.31%) were in the H. pylori-positive group and 2354 cases (66.69%) were in the H. pylori-negative group. In the 30–59 age group, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), triglycerides (TG), and total cholesterol (TC) levels were significantly higher in H. pylori-positive individuals compared to H. pylori-negative individuals (P < 0.05), with no significant differences in other age groups (P > 0.05). Binary Logistic regression showed that H. pylori infection was associated with elevated LDL-c [OR = 2.100, 95%CI (1.771–2.491), P < 0.001], elevated TC [OR = 2.844, 95%CI (2.232–3.623), P < 0.001], male gender [OR = 1.267, 95%CI (1.054–1.524), P < 0.05], ages 40–49 [OR = 1.602, 95%CI (1.181–2.173), P < 0.05].

Conclusions

H. pylori infection is associated with dyslipidemia in non-obese and non-diabetic people, especially those aged 30–59. In men aged 40–49, H. pylori positivity was more strongly related to elevated TC and LDL-c, highlighting the importance of routine H. pylori screening in this age group.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Dyslipidemia, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram-negative bacterium that is strongly associated with the occurrence of chronic gastritis (90%), peptic ulcers (5-10%), and gastric cancer (1%) [1, 2]. The global population exhibits a general susceptibility to H. pylori infection, which is prevalent across various regions and ethnic groups, with infection rates reaching up to 50%. China, in particular, has a high prevalence of H. pylori infection and a high incidence of gastric cancer [3]. Eradication of H. pylori can significantly reduce the risk of gastric cancer [4]. In 1994, H. pylori was classified as a Group I carcinogen, and in 2022, the US Department of Health and Human Services formally recognized H. pylori as carcinogen [5, 6]. Recent studies have broadened the understanding of H. pylori infection, revealing its association not only with gastrointestinal disease but also with hematological, neurological, and cardiovascular diseases, underscoring the importance of early detection and treatment [7, 8]. Furthermore, extensive research has shown an association between H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia [9, 10], meanwhile, a meta-analysis found no significant association between H. pylori seropositivity and TC or TG levels [11]. The relationship between H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia in different age groups remains underexplored, particularly in the context of age-specific metabolic changes.

This study, a retrospective cross-sectional survey, aims to assess the association of H. pylori infection with dyslipidemia in the Chinese non-obese and non-diabetic population from the perspective of age category.

Materials and methods

Research object

A total of 3530 patients met the inclusion criteria in a physical examination at the 991st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of People’s Liberation Army from January to December 2024. All personnel were required to maintain a stable diet and body weight for at least 2 weeks before blood collection, avoid overeating, avoid strenuous physical activity for 24 h, overnight fast for 8–12 h, and rest for at least 5 min in a seated position. Clinical information was collected and analyzed, including medical history, age, gender, body mass index (BMI), serum lipid parameters [total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c)], and 14C-urea breath test results. Inclusion criteria: ① Patients aged 20–70 years, regardless of gender, completed 14C-urea breath test and serum lipid parameters; ② complete clinical data; ③ no previous or current H. pylori eradication therapy and dyslipidemia therapy [12]; ④ non-obese and non-diabetic population. Exclusion criteria: ① patients with a history of malignancy, abnormal liver or kidney function, mental illness, and obesity or diabetes; ② patients with severe cardiopulmonary dysfunction; ③ patients receiving H. pylori eradication therapy and dyslipidemia therapy; ④ BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c ≥ 6.5); ⑤ incomplete clinical data. The incomplete data were deleted. The incomplete data were serum lipid parameters (TG, TC, LDL-c, or HDL-c), and the proportion of missing data was 4.59%, which was less than 5%. Deletion and mean-filling methods were used to handle the missing data. The results of the statistical analysis showed that the conclusions drawn from the two methods of handling missing data were consistent.

Determination of sample size

The sample size was calculated using PASS 21, based on a presumed 50% infection rate, 95% confidence level, and 5% CI width. Post-hoc power analysis was not conducted; however, the large sample size (n = 3,530) ensures sufficient statistical power for detecting meaningful associations.

Definition of H. pylori infection

Subjects fasted for at least 6 h before testing and completed the 14C-urea breath test. The entire 14C-urea capsule was swallowed during the examination. The patient was instructed to remain seated quietly and to as little as possible after taking the medicine. Within 15–25 min, the patient was instructed to take a long inhalation followed by a slow exhalation, and forced exhalation was prohibited. The test was performed immediately after exhalation. Samples were then analyzed using a 14 C-urea breath analyzer. To account for the possibility of false-positive and false-negative results near the critical value, a value ≥ 75 is considered positive [13].

Definition of dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia was defined as meeting one of the following criteria: HDL-c level < 0.9 mmol/L; LDL-c level ≥ 3.4 mmol/L, TG level ≥ 1.7 mmol/L, TC level ≥ 5.2 mmol/L, according to the Chinese guidelines for Lipid Management (2023) [14]. Dyslipidemia was defined as either “borderline high LDL-c, TC, TG " or “low HDL-c,” whichever occurred first [15].

Observation target

The main observations were as follows: (1) To understand the overall H. pylori infection rate; (2) The included researchers were divided into 20–29 ages, 30–39 ages, 40–49 ages, 50–59 ages, and ≥ 60 ages, and the situation of H. pylori infection in different age groups was compared; (3) The patients were divided into H. pylori-positive group and H. pylori-negative group, and the four indicators of blood lipids were compared between the two groups according to age category; (4) one-way ANOVA was used to analyze the correlation between H. pylori infection and four indicators of blood lipids; (5) binary Logistic regression model was used to analyze the factors influencing H. pylori infection.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted by the ethical principles of the Medical Ethics Committee of the 991st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of People’s Liberation Army (No. 991YJ-202316). Data were anonymized using numerical coding to maintain patient confidentiality, and all data collected were used only for this research.

Statistical data analysis

SPSS 22 software was used for statistical analysis. Continuous and categorical variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (x̅±s) and counts or percentages, using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA and chi-square test for comparisons between the two groups. A binary Logistic regression model was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) associated with H. pylori infection. The dependent variable was the presence of H. pylori infection, and the variables included in the analysis were analyzed using one-way ANOVA or chi-square tests for statistical significance. Confounders were controlled using the forward stepwise method. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Part 1

Baseline status of H. pylori infection

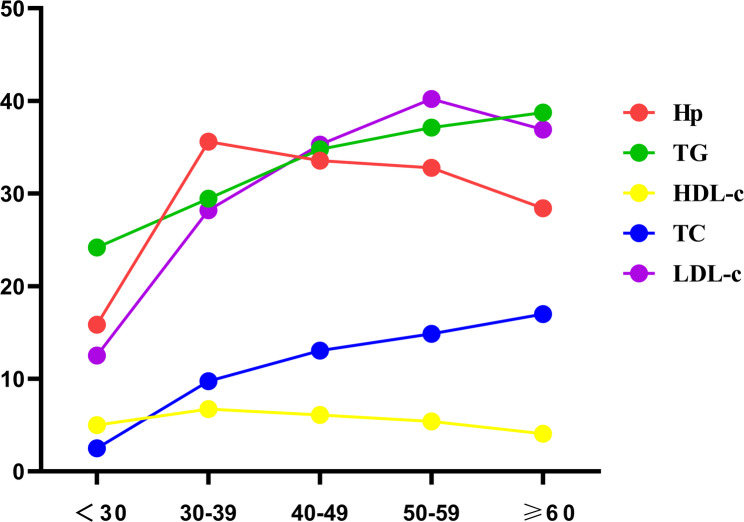

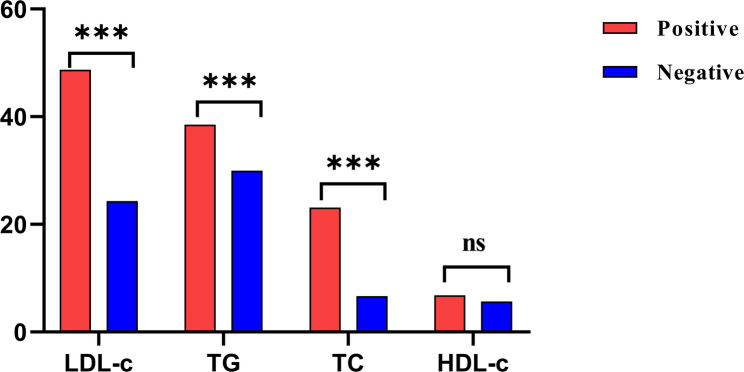

The baseline characteristics of all enrolled participants are shown in Table 1. Of 3530 individuals, 1176 (33.31%) were infected with H. pylori, and 2354 (66.69%) were not infected with H. pylori. The infection rate was 35.18% (914/2598) in males and 28.11% (262/932) in females. There was no significant difference in mean age between the H. pylori-positive group and the H. pylori-negative group (P > 0.05). To further explore the relationship between the two was examined by age category. The overall infection rate was highest in those 30–39 ages (35.59% (567/1593)) and lowest in those 20–29 ages (15.83% (19/120)). The infection rate was higher in those aged 40–49 and 50–59 than in those aged > 60. There was no significant difference in age between the two groups, but there were significant differences in gender and age category between the two groups (P < 0.05). Figure 1 shows the abnormal proportions of H. pylori infection, HDL-c, TG, LDL-c, and TC in each age category. The proportion of H. pylori infection was higher in the age category of 30–59 years, which was more than 30%. The proportion of abnormal HDL-c was stable in all age groups, lower than 7%; the proportion of abnormal LDL-c was different in different age groups, and the abnormal proportion increased with increasing age, but the abnormal proportion was highest in the 50–59 age group, reaching 40.22%. The proportion of TG and TC also increased with age, but the abnormal proportion of TG was higher than that of TC in all age groups, and the abnormal proportion was highest in people aged > 60 years (38.75% vs. 16.97%). Figure 2 shows the abnormal proportions of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c in the H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups. The abnormal proportion of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups were (48.72% vs. 24.34%), (23.13% vs. 6.66%), (38.52% vs. 29.95%), and (6.80% vs. 5.65%). There was no significant difference in HDL-c between the two groups (P > 0.05), but the comparison of LDL-c, TC, and TG between the two groups was significant (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

General data of patients in the two groups (using student’s t test or chi-square test)

| Variable | H. pylori-positive group n = 1176(%) | H. pylori-negative group n = 2354(%) | t/X2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 15.43 | 0.00 | ||||

| male | 914(77.72) | 1684(71.54) | ||||

| Female | 262(22.28) | 670(28.46) | ||||

| Average | 42.19 ± 10.56 | 42.66 ± 10.76 | 1.22 | 0.22 | ||

| age/year | ||||||

| Age category/year | 23.27 | 0.00 | ||||

|

20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 ≥ 60 |

19(15.83) 567(35.59) 270(33.54) 243(32.79) 77(28.41) |

101(84.17) 1026(64.41) 535(66.46) 498(67.21) 194(71.59) |

Fig. 1.

The proportion of H. pylori positive, HDL-c, TG, LDL-c, and TC abnormality in each age category. H. pylori infections were marked in red, TG abnormal in green, HDL-c abnormal in yellow, TC abnormal in blue, and LDL-c abnormal in purple

Fig. 2.

Abnormal proportions of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c in the H. pylori-positive group and the H. pylori-negative group. “Positive” represents the proportion of H. pylori-positive patients with abnormal LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c, marked in red, and “Negative” represents the proportion of H. pylori-negative patients with abnormal LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c, marked in blue. *** indicates significance <0.01, ns indicates significance >0.05

Correlation between H. pylori infection status and dyslipidemia

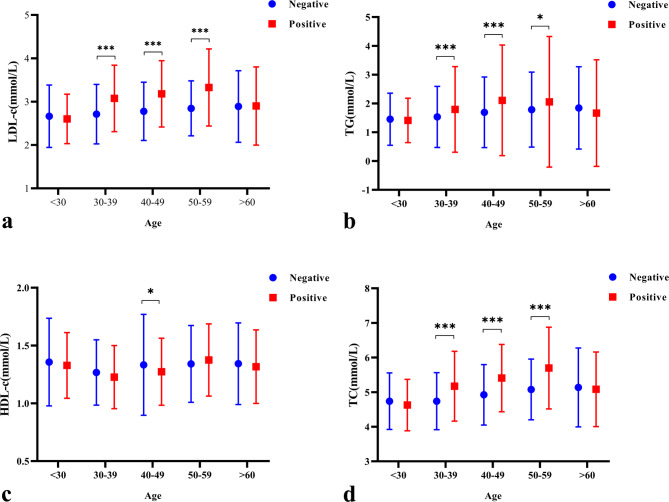

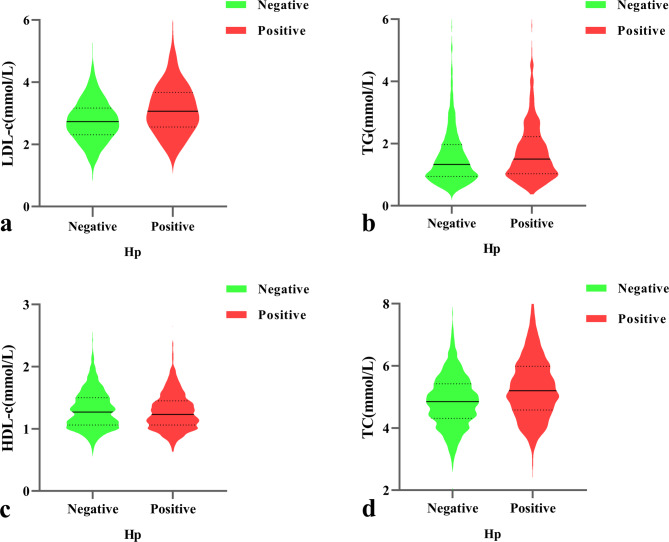

The comparison of mean ± standard deviation (SD) of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c levels at the age categories in the H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups is shown in Table 2. Statistically significant differences in H. pylori infection status were assessed by comparing H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative individuals. In the total category of participants, the levels of LDL-c (3.133 ± 0.810), TC (5.319 ± 1.062), and TG (1.905 ± 1.746) were higher in the H. pylori-positive group than in the negative group (2.768 ± 0.690, 4.885 ± 0.888, 1.645 ± 1.186). The HDL-c level in the positive group was lower than that in the negative group (1.276 ± 0.294 vs. 1.308 ± 0.345, both P < 0.05). Figure 3 Age category shows the mean ± SD of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups. The median (IQR) levels of LDL-c (Fig. 4a), TG (Fig. 4b), HDL-c (Fig. 4c), and TC (Fig. 4d) by H. pylori-infection status are shown in Fig. 4. The median (IQR) levels of LDL-c, TG, and TC in the H. pylori-positive group were higher than those in the H. pylori-negative group in the 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 age groups, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05), whereas there was no significant difference in blood lipid levels between the H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups in the < 30 and ≥ 60 age groups (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparative the mean ± sd of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c levels at the age categories in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups (using one-way ANOVA)

| Overall Participants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | H. pylori-positive group (mean ± SD) | H. pylori-negative group (mean ± SD) | p | ||||

|

LDL-c TC |

3.133 ± 0.810 5.319 ± 1.062 |

2.768 ± 0.690 4.885 ± 0.888 |

0.00 0.00 |

||||

|

TG HDL-c |

1.905 ± 1.746 1.276 ± 0.294 |

1.645 ± 1.186 1.308 ± 0.345 |

0.00 0.00 |

||||

| Age category (Age < 30) | |||||||

|

LDL-c TC TG HDL-c |

2.602 ± 0.569 4.627 ± 0.744 1.410 ± 0.771 1.328 ± 0.284 |

2.664 ± 0.719 4.739 ± 0.816 1.452 ± 0.905 1.357 ± 0.379 |

0.72 0.58 0.85 0.76 |

||||

| Age category (Age 30–39) | |||||||

|

LDL-c TC TG HDL-c |

3.075 ± 0.767 5.172 ± 1.008 1.792 ± 1.485 1.227 ± 0.273 |

2.713 ± 0.686 4.739 ± 0.824 1.533 ± 1.060 1.267 ± 0.283 |

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.07 |

||||

| Age category (Age 40–49) | |||||||

|

LDL-c TC TG HDL-c |

3.182 ± 0.765 5.407 ± 0.972 2.107 ± 1.920 1.273 ± 0.290 |

2.777 ± 0.672 4.924 ± 0.873 1.692 ± 1.226 1.333 ± 0.437 |

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.04 |

||||

| Age category (Age 50–59) | |||||||

|

LDL-c TC TG HDL-c |

3.328 ± 0.889 5.696 ± 1.179 2.057 ± 2.267 1.375 ± 0.312 |

2.846 ± 0.634 5.077 ± 0.877 1.785 ± 1.302 1.341 ± 0.332 |

0.00 0.00 0.04 0.18 |

||||

| Age category (Age ≥ 60) | |||||||

|

LDL-c TC TG HDL-c |

2.900 ± 0.901 5.082 ± 1.077 1.667 ± 1.850 1.317 ± 0.318 |

2.889 ± 0.826 5.136 ± 1.140 1.844 ± 1.429 1.343 ± 0.353 |

0.93 0.73 0.31 0.58 |

||||

Fig. 3.

Age category showed the mean ± SD of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups. H. pylori-positive groups were marked in red, and H. pylori-negative groups were marked in blue. *** indicates significance <0.01, * indicates significance <0.05. a: LDL-c level and Helicobacter pylori infection status in each age group; b: TG level and Helicobacter pylori infection status in each age group; c: HDL-c level and Helicobacter pylori infection status in each age group; d: TC level and Helicobacter pylori infection status in each age group

Fig. 4.

Illustration of the median (IQR) of LDL-c, TC, TG, and HDL-c levels in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups, respectively. Dyslipidemia in the H. pylori-positive group was marked in red, and dyslipidemia in the H. pylori-negative group was marked in green. a: level of LDL-c by H. pylori-infection status; b: level of TG by H. pylori-infection status; c: level of HDL-c by H. pylori-infection status; d: level of TC by H. pylori-infection status

Part 2

The influencing factors of H. pylori infection were analyzed by binary logistic regression

Using one-way ANOVA or Chi-square test to screen out two groups of significant factors. The results showed that age category, gender, LDL-c, TG, and TC were statistically significant. A binary Logistic regression model was used to screen out factors related to H. pylori infection. With H. pylori infection as dependent variable (0 = no, 1 = yes), age category (20–29 years = 0, 30–39 years = 1, 40–49 years = 2, 50–59 years = 3, ≥ 60 years = 4), gender (female = 0, male = 1), LDL-c (not elevated = 0, elevated = 1), TG (not elevated = 0, elevated = 1), TC (not elevated = 0, elevated = 1) were used as independent variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. After adjustment for confounders, binary logistic regression analysis showed that male gender, age 40–49 years, elevated LDL-c and TC were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection (P<0.05). Binary Logistic regression analysis revealed the following associations with H. pylori infection: (1) elevated LDL-c [OR = 2.100, 95%CI (1.771–2.491), P < 0.001] vs. normal levels; (2) elevated TC [OR = 2.844, 95%CI (2.232–3.623), P < 0.001] vs. normal levels; (3) male gender [OR = 1.267, 95%CI (1.054–1.524), P < 0.05] vs. female; (4) age 40–49 [OR = 1.602, 95%CI (1.181–2.173), P < 0.05] vs. other age groups. As shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Influencing factors of H. pylori infection in binary logistic regression model

| Variable | β | SE | Waldχ2 | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| elevated LDL-c | 0.742 | 0.087 | 72.692 | 2.100 | 1.771~2.491 | 0.000 |

|

elevated TC male 40–49 age |

1.045 0.237 0.471 |

0.124 0.094 0.156 |

71.573 6.357 9.176 |

2.844 1.267 1.602 |

2.232~3.623 1.054~1.524 1.181~2.173 |

0.000 0.012 0.002 |

Discussion

H. pylori was first identified in 1982 by Australian researchers in gastric biopsy specimens from people with chronic gastritis. This bacterium typically colonizes the human stomach and causes chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa, which can progress to atypical hyperplasia and even malignant lesions [16, 17]. The prevalence of H. pylori infection exceeds 50% in the general population [18–21], with marked differences between developed and developing countries, as well as regional variations within countries [22, 23]. The incidence of H. pylori infection is increasing every year, has a significant impact on both physical and mental health, imposes a substantial economic and healthcare burden, and has therefore become a focus of research in recent years [24–27]. As research progresses, it becomes clear that H. pylori infection may not only contribute to gastrointestinal disorders but may also be involved in diseases of the hematological, neurological, and cardiovascular systems [28–31].

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading chronic non-communicable disease threatening human life and health worldwide. Epidemiological, genetic, and clinical intervention studies have fully confirmed that LDL-c is a pathogenic risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [32]. TC levels often increase with age and are lower in young and middle-aged women than in men. TC levels are higher in postmenopausal women than in men of the same age [14]. The association between H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia was first identified in 1996 in a Finnish case-control study. H. pylori infection may exacerbate metabolic disorders through inflammatory processes and elevated TG, TC, and LDL-c, thereby increasing the risk of CVD [33]. H. pylori can cause chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa, and the global effect of inflammation may be related to the mechanism of atherosclerosis [34]. In addition, studies show that high TG levels are an inflammatory and metabolic predictor in several conditions. These include CVD [35], type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [36], hypertension [37], chronic nephritis [38–40] and hepatic steatosis [41]. Low levels of HDL-c have also been reported in hypertension [42], non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis [43], T2DM [44], thyroiditis [45], metabolic syndrome [46], pre-diabetes [47], diabetic kidney disease [48], and even in new-onset diabetes [49].

The mechanisms by which H. pylori infection affects blood lipids are diverse: (1) H. pylori infection can lead to anorexia, dyspepsia, and malabsorption as a result of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcers, which in turn may affect food intake and energy metabolism, potentially contributing to the development of dyslipidemia [50]. (2) H. pylori infection affects lipid metabolism by activating pro-inflammatory cytokines that affect lipolysis, stimulate hepatic fatty acid synthesis, and activate lipoprotein lipase in adipose tissue. In addition, H. pylori infection induces the production of several pro-inflammatory mediators and vasoactive substances, thereby increasing oxidative stress and insulin resistance through autoimmune pathways. The local microenvironment can be altered by several factors. Abnormal blood lipid levels and insulin resistance have a bidirectional interaction. Insulin resistance contributes to dyslipidemia, typically characterized by elevated TC and TG. Hyperinsulinemia induces sympathetic activation, upregulates α1-adrenergic receptors and angiotensin II, decreases lipoprotein lipase activity, and impairs TG catabolism, thereby promoting lipid dysregulation and atherogenesis [51]. (3) H. pylori infection can induce oxidative stress in gastric epithelial cells, triggering various pathophysiological mechanisms and eliciting host responses [52, 53]. Oxidative stress alters HDL-c-associated enzymes, leading to reduced HDL-c levels and subsequent lipoprotein and lipid abnormalities. In addition, serum amyloid A (SAA), an inflammatory mediator, can be induced to replace key HDL components, further reducing HDL-c levels and affecting lipid distribution and blood lipid profiles [54]. (4) H. pylori infection alters the structure of the gastrointestinal flora, thereby reducing the diversity of the flora. H. pylori infection interferes with the homeostasis of the internal environment and lipid metabolism by the intestinal flora [55]. A large study confirmed that the gut microbiome plays an important role in blood lipid changes [56].

Our study population was a normal population without obesity and diabetes. The population was divided into H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative groups according to the results of the 14C-urea breath test. There was significant difference in gender between the two groups, but there was no difference in age. However, the infection rate was higher in those aged 30–59 ages than in those aged 20–29 ages and > 60 years. There was a significant difference in age category between the two groups (P < 0.05). This is in line with the results of Sun et al., who reported that more men than women tended to be infected with H. pylori, with the highest positive rate in the 30–39 age group and the lowest rate in the < 30 age group [57]. Compared with H. pylori-negative individuals, H. pylori-positive individuals had significantly higher LDL-c, TC, and TG levels and lower HDL-c levels (all P < 0.05). These differences remained significant in the 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 age groups (P < 0.05). However, no significant differences in lipid profile were observed in the age groups < 30 or ≥ 60 years (P > 0.05). Binary logistic regression showed the odds of H. pylori infection were significantly higher in individuals with elevated LDL-c (OR = 2.100, 95% CI: 1.771–2.491) and elevated TC (OR = 2.844, 95% CI: 2.232–3.623) compared to those with normal levels. Similarly, males had 1.267-fold increased odds (OR = 1.267, 95% CI: 1.054–1.524) compared to females, and the 40–49 age group had 1.602-fold increased odds (OR = 1.602, 95% CI: 1.181–2.173) compared to other age groups (all p-values < 0.05). This was consistent with Izhari et al. study [58], who reported that one-unit increase in the level of TC, TG, and LDL-c increased the odds of being infected with H. pylori by 226.2% (AOR:3.26, 95%CI:1.778–6.258, p < 0.001), 30% (AOR:1.298, 95%CI:0.928–1.834, p > 0.05), and 67% (AOR:0.333, 95%CI:0.156–0.676, p < 0.01), respectively. A meta-analysis also showed that H. pylori infection was positively associated with LDL-c, TC, and TG [59].

In this study, using age category, we found that H. pylori infection was more closely associated with dyslipidemia in the 30–59 age group and the possible reasons were as follows: (1) With increasing age, the basal metabolic rate gradually decreases, the rate of lipolysis slows down, lipase activity decreases, and there is a tendency for fat accumulation and abnormal lipid metabolism. (2) In postmenopausal women, decreasing estrogen levels can lead to decreased levels of HDL-c and increased levels of LDL-c [60]. (3) H. pylori infection can cause chronic inflammation of the stomach lining. With age, there may be a reduced ability to clear H. pylori, resulting in the persistence of this inflammatory response. Dyslipidemia may also exacerbate oxidative stress and inflammation, creating a vicious cycle. Oxidative stress caused by H. pylori infection affects the function of the immune system, which in turn has a greater impact on blood lipids and exacerbates cardiometabolic disease [61]. (4) Unhealthy lifestyle and eating habits also play a role. People in this age group often face greater work and life pressures, leading to irregular eating patterns, high-fat and high-calorie diets, and lack of exercise. These factors alone increase the risk of dyslipidemia, and H. pylori infection may interact with these adverse lifestyle factors to exacerbate dyslipidemia. In younger people, the metabolism is more active and H. pylori infection may be cleared more easily. However, in older adults with conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, the effects of H. pylori may be less evident. It is therefore important to monitor the relationship between H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia in this age group.

The pathogenesis of H. pylori is based on its ability to produce a variety of virulence factors [62]. Cytotoxic-associated protein (CagA) and vacuolated toxin (VacA) are the most important virulence factors of H. pylori [63]. Studies have confirmed an association between infection with CagA-positive strains and coronary heart disease [64]. Studies have shown that lipid metabolism can be effectively improved after H. pylori eradication treatment. Wang et al. [65] suggested that after adjustment for confounding factors, H. pylori eradication would alleviate the deterioration of lipid metabolism, and patients with low total protein (TP) would benefit more from lipid metabolism after eradication, suggesting the positive role of H. pylori in controlling and improving lipid metabolism. The results of Adachi et al. showed lower concentrations of TC, TG, and LDL-c and higher levels of HDL-c in successfully eradicated H. pylori subjects compared to those with persistent H. pylori infection [66]. Park Y et al. [15] reported that H. pylori infection might play a pathophysiological role in developing dyslipidemia, whereas H. pylori eradication may reduce the risk of dyslipidemia. A triple therapy regimen for H. pylori eradication in Egypt found that there was a significant association between treatment of H. pylori infection and reduction in LDL-c, TG, and TC with an increase in HDL-c in both the 7-day and 10-day groups [67].

Although this study was a cross-sectional survey of a large sample of non-diabetic and non-obese populations, it is imperative to acknowledge that certain limitations were also evident in this study. First, this study is limited to a single center in China, the source of patients is relatively single, which may cause selective bias. Due to factors such as diet and genetic polymorphism, which may limit generalizability to other populations or ethnic groups. To establish more reliable evidence, there is a need for prospective multicenter cohort or international studies that would improve external validity. Second, this is a cross-sectional study, and although it confirmed the association between H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia, it could not determine the sequence of H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia. Third, the effect of H. pylori eradication on blood lipids was not included in the study. Fourth, the H. pylori infection status was only determined by the 14C-urea test, and H. pylori virulence factors and the influence of different types on dyslipidemia were not analyzed. Fifth, confounding factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and socioeconomic status—which may affect both H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia—were not measured in this study. This limitation may have introduced residual confounding, potentially over- or underestimating the observed associations. Sixth, missing data (4.59%) were limited to lipid parameters (TG, TC, LDL-c, HDL-c) and were handled using both listwise deletion and mean imputation. Although results were similar across both methods, we acknowledge that mean imputation has methodological limitations, and no formal sensitivity analysis was performed, which may affect robustness. Further studies should be needed in the following areas: First, lifestyle and environmental factors will be further collected in people aged 30–59 to assess the impact of lifestyle and environmental factors on H. pylori infection and dyslipidemia. Second, long-term cohort studies should be conducted to follow the effects of H. pylori infection on dyslipidemia over a long period and to observe the effects of H. pylori infection on blood lipids in obese or diabetic populations, to improve the scalability of the study. Third, future prospective cohort studies should evaluate whether H. pylori eradication therapy improves LDL-c, TC, and TG levels over time. Fourth, H. pylori virulence factors will be further analyzed to determine whether certain strains are more strongly associated with dyslipidemia.

Conclusions

Our results show that H. pylori infection is associated with dyslipidemia in the non-obese and non-diabetic population, especially those aged 30–59. In men aged 40–49, H. pylori positivity was more strongly associated with elevated TC and LDL-c, highlighting the importance of routine H. pylori screening in this age group. The occurrence of dyslipidemia in H. pylori-positive individuals may trigger atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, and cerebral infarction in the population. Given the statistically significant association of dyslipidemia with H. pylori-positive individuals, effective management of the lipid profile of H. pylori-positive patients would be beneficial to minimize the clinical impact of infection on CVD.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants for their cooperation and support.

Abbreviations

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- LDL-c

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-c

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- PPI

Proton pump inhibitor

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- ASCVD

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BMI

Body mass index

- HbA1c

Glycated hemoglobin A1c

- OR

Odds ratios

- CI

Confidence intervals

- SD

Standard deviation

Author contributions

HHS played a pivotal role in shaping the conceptual framework, conceptualizing and designing this study, assisting in data collection, supervising data entry, carrying out the initial analysis, drafting the initial manuscript, and reviewing and revising the final manuscript. JWW and XYZ contributed to the composition of the manuscript. DLZ were responsible for collecting data and conducting data analysis. KY and SX drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the final manuscript. Furthermore, all ICMJE requirements for authorship have been met, and this work is original and honest. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the 991st Hospital of Joint Logistic Support Force of People’s Liberation Army (991YJ-202316).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants underwent review and approval by the Ethics Committee of the 991st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of People’s Liberation Army (No. 991YJ-202316). Our study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective study used de-identified historical medical records and did not involve any intervention or additional risk to participants. The Ethics Committee of the 991st Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of the People’s Liberation Army waived informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kai Yue, Email: 397374436@qq.com.

Song Xu, Email: 99043339@qq.com.

References

- 1.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, et al. European Helicobacter and microbiota study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht vi/florence consensus report. Gut. 2022;71(9):1724–62. 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327745. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding SZ, Du YQ, Lu H, Wang WH, Cheng H, Chen SY, et al. Chinese consensus report on family-based Helicobacter pylori infection control and management (2021 edition). Gut. 2022;71(2):238–53. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv HN, Xie C. Overview and prospect of study on Helicobacter pylori infection in China (In Chinese). Chin J Digestion. 2021;41(4):217–20. 10.3760/cma.j.cn311367-202110201-00075. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan L, Chen Y, Chen F, Tao T, Hu Z, Wang J, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric cancer prevention: updated report from a randomized controlled trial with 26.5 years of follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):154–62. 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NTP (National. Toxicology Program).15th report on carcinogens. Rep Carcinog. 2021;15:roc15. 10.22427/NTP-OTHER-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancer Prevention and Control Committee of the Chinese Preventive Medical Association, colposcopy and Cervical Lesions Committee of the Gynecologists Branch of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association, Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology Branch of the Chinese Eugenic Science Associationetc. Chinese expert consensus on the use of human papillomavirus nucleic acid testing for cervical cancer screening. Chin Med J. 2022;2023(10316):1184–95. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranjbar R, Ebrahimi A, Sahebkar A. Helicobacter pylori infection: conventional and molecular strategies for bacterial diagnosis and antibiotic resistance testing. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2023;24(5):647–64. 10.2174/1389201023666220920094342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katelaris P, Hunt R, Bazzoli F, Cohen H, Fock KM, Gemilyan M, et al. Helicobacter pylori world gastroenterology organization global guideline. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(2):111–26. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satoh H, Saijo Y, Yoshioka E, Tsutsui H. Helicobacter Pylori infection is a significant risk for modified lipid profile in Japanese male subjects. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17(10):1041–8. 10.5551/jat.5157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim TJ, Lee H, Kang M, Kim JE, Choi YH, Min YW, et al. Helicobacter pylori is associated with dyslipidemia but not with other risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38015. 10.1038/srep38015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danesh J, Peto R. Risk factors for coronary heart disease and infection with Helicobacter pylori: meta-analysis of 18 studies. BMJ. 1998;316(7138):1130–2. 10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moretti E, Gonnelli S, Campagna M, Nuti R, Collodel G, Figura N. Influence of Helicobacter pylori infection on metabolic parameters and body composition of dyslipidemic patients. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9(7):767–72. 10.1007/s11739-013-1043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu JM. 14 C Urea breath test quality control scheme (In Chinese). Anhui Med Sci. 2019;40(1):1000–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joint Committee on the Chinese Guidelines for Lipid Management. Chinese guidelines for lipid management (2023, in Chinese). Chin J Cardiol. 2023;51(3):221–55. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20230119-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park Y, Kim TJ, Lee H, Yoo H, Sohn I, Min YW, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection decreases risk for dyslipidemia: a cohort study. Helicobacter. 2021;26(2):e12783. 10.1111/hel.12783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokolova O, Naumann M. Matrix metalloproteinases in Helicobacter pylori -Associated gastritis and gastric Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1883. 10.3390/ijms23031883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan M, Liu J, Zuo X. Dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Chin Med J(Engl). 2023;136(1):13–23. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruera M, Amezquita MV, Riquelme AJ, Serrano CA, Harris PR. Helicobacter pylori infection and UBT-13 C values are associated with changes in body mass index in children and adults. Rev Med Chil. 2022;150(11):1467–76. 10.4067/S0034-98872022001101467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Zhang T, Lu Y, Wang C, Wu Y, Li J, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection affects the human gastric microbiome, as revealed by metagenomic sequencing. FEBS Open Bio. 2022;12(6):1188–96. 10.1002/2211-5463.13390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishigaki Y, Sato Y, Sato H, Iwafuchi M, Terai S. Influence of Helicobacter pylori infection on Hepcidin Eexpression in the gastric mucosa. Kurume Med J. 2023;68(2):107–13. 10.2739/ku-rumemedj.MS682011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi JM, Park HE, Han YM, Lee J, Lee H, Chung SJ, et al. Non-alcoholic/metabolic‐associated fatty liver disease and Helicobacter pylori additively increase the risk of arterial stiffness. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:844–954. 10.3389/fmed.2022.844954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minty M, LêS, Canceill T, Thomas C, Azalbert V, Loubieres P, et al. Low-diversity microbiota in apical periodontitis and high blood pressure are signatures of the severity of apical lesions in humans. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2):1589. 10.3390/ijms24021589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren S, Cai P, Liu Y, Wang T, Zhang Y, Li Q, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in china: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(3):464–70. 10.1111/jgh.15751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkey C, Avery A, Coupland CAC, Crooks C, Dumbleton J, Hobbs FDR, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication for primary prevention of peptic ulcer bleeding in older patients prescribed aspirin in primary care (HEAT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10363):1597–606. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poosari A, Nutravong T, Namwat W, Sa-Ngiamwibool P, Ungareewittaya P, Boonyanugomol W. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of esophageal cancer in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2023;24(3):1073–80. 10.31557/APJCP.2023.24.3.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding SZ, Du YQ, Lu H, Wang WH, Cheng H, Chen SY et al. Chinese Consensus Report on Family-Based Helicobacter pylori Infection Control and Management (2021 Edition). Gut.2022;71(2):238–253. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Li C, Yue J, Ding Z, Zhang Q, Xu Y, Wei Q, et al. Prevalence and predictors of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic individuals: A hospital-based cross-sectional study in shenzhen, China. Postgrad Med. 2022;134(7):686–92. 10.1080/00325481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou XZ, Lyu NH, Zhu HY, Cai QC, Kong XY, Xie P, et al. Large-scale, national, family-based epidemiological study on Helicobacter pylori infection in china: the time to change practice for related disease prevention. Gut. 2023;72(5):855–69. 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang J, Lin Y. Vonoprazan on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023;34(3):221–6. 10.5152/tig.2022.211041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen C, Li C, Lv M, Dai X, Gao C, Li L, et al. The prospective multiple-centre randomized controlled clinical study of high-dose amoxicillin-proton pump inhibitor dual therapy for H. pylori infection in Sichuan areas. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):426–35. 10.1080/07853890.2022.2031269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malfertheiner P, Camargo MC, El-Omar E, Liou JM, Peek R, Schulz C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):19. 10.1038/s41572-023-00431-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European atherosclerosis society consensus panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459–72. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tali LDN, Faujo GFN, Konang JLN, Dzoyem JP, Kouitcheu LBM. Relationship between active Helicobacter pylori infection and risk factors of cardiovascular diseases, a cross-sectional hospital-based study in a Sub-Saharan setting. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):731. 10.1186/s12879-022-07718-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gravina AG, Zagari RM, De, Musis C, Romano L, Loguercio C, Romano M. Helicobacter pylori Extragastric Diseases: Rev World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(29):3204–21. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aktas G. Letter regarding associations of non-HDL-C and triglyceride/HDL-C ratio with coronary plaque burden and plaque characteristics in young adults. Biomol Biomed. 2023;23(1):187. 10.17305/bjbms.2022.7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bilgin S, Aktas G, Atak Tel BM, Kurtkulagi O, Kahveci G, Duman T. Triglyceride to high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is elevated in patients with complicated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Facultatis Medicae Naissensis. 2022;39(1):66–73. 10.5937/afmnai39-33239. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurtkulagi O, Aktas G, Duman TT, Bilgin S, Atak Tel BM, Kahveci G. Correlation between serum triglyceride to HDL cholesterol ratio and blood pressure in patients with primary hypertension. Precision Med Sci. 2022;11(3):100–5. 10.1002/prm2.12080. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson JLC, Bakker SJL, Tietge UJF. Triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio and premature all-cause mortality in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2021;36:936–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfaa321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson JLC, Bakker SJC, Tietge UJF. The triglyceride to HDL-cholesterol ratio and chronic graft failure in renal transplantation. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15:301–10. 10.1016/j.jacl.2021.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia W, Yao X, Chen Y, Lin J, Vielhauer V, Hu H. Elevated TG/HDL-C and non-HDL-C/HDL-C ratios predict mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:1–9. 10.1186/s12882-020-01993-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurtkulagi O, Bilgin S, Kahveci GB, Atak Tel BM, Kosekli MA. Could triglyceride to high density lipoprotein-cholesterol ratio predict hepatosteatosis? Exp Biomed Res. 2021;4:224–9. 10.30714/j-ebr.2021370081. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aktas G, Khalid A, Kurtkulagi O, Duman TT, Bilgin S, Kahveci G, et al. Poorly controlled hypertension is associated with elevated serum uric acid to HDL-cholesterol ratio: a cross-sectional cohort study. Postgrad Med. 2022;134(3):297–302. 10.1080/00325481.2022.2039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kosekli MA, Kurtkulagi O, Kahveci G, Duman TT, Tel BMA, Bilgin S et al. The association between serum uric acid to high density lipoprotein-cholesterol ratio and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the abund study. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2021;67(4):549–554. 10.1590/1806-9282.20201005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Aktas G, Kocak MZ, Bilgin S, Atak BM, Duman TT, Kurtkulagi O. Uric acid to HDL cholesterol ratio is a strong predictor of diabetic control in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):1098–102. 10.1080/13685538.2019.1678126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurtkulagi O, Tel BMA, Kahveci G, Bilgin S, Duman TT, Ertürk A, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is associated with elevated serum uric acid to high density lipoprotein-cholesterol ratio. Rom J Intern Med. 2021;59(4):403–8. 10.2478/rjim-2021-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kocak MZ, Aktas G, Erkus E, Sincer I, Atak B, Duman T. Serum uric acid to HDL-cholesterol ratio is a strong predictor of metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2019;65(1):9–15. 10.1590/1806-9282.65.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balci SB, Atak BM, Duman T, Ozkul FN, Aktas G. A novel marker for prediabetic conditions: uric acid-to-HDL cholesterol ratio. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2024;125(3):145–8. 10.4149/BLL_2023_130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aktas G, Yilmaz S, Kantarci DB, Duman TT, Bilgin S, Balci SB, et al. Is serum uric acid-to-HDL cholesterol ratio elevation associated with diabetic kidney injury? Postgrad Med. 2023;135(5):519–23. 10.1080/00325481.2023.2214058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kosekli MA, Aktas G, Serum uric acid to HDL cholesterol ratio is associated with, diabetic control in new onset type 2 diabetic population. Acta Clin Croat. 2023;62(2):277–82. 10.20471/acc.2023.62.02.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou X, Zhu Y, Liu J, Liu J. Effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on the development of chronic gastritis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023;34(7):700–13. 10.5152/tjg.2023.22316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou SM, Zhang XY, Li YM. Correlation analysis of glucose and lipid metabolism in elderly patients with Helicobacter pylori infection complicated with metabolic syndrome (In Chinese). J Public Health Prev Med. 2023;34(2):135–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-2483.2023.02.030. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang S, Chen Z, Zhu S, Lu H, Peng D, Soutto M, et al. PRDX2 protects against oxidative stress induced by H. pylori and promotes resistance to cisplatin in gastric cancer. Redox Biol. 2020;28:101319. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gobert AP, Wilson KT. Polyamine- and NADPH dependent generation of ROS during Helicobacter pylori infection: A blessing in disguise. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;105:16–27. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie Q, He Y, Zhou D, Jiang Y, Deng Y, Li R. Recent research progress on the correlation between metabolic syndrome and Helicobacter pylori infection. PeerJ. 2023;11:e15755. 10.7717/peerj.15755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Francisco AJ. Helicobacter pylori infection induces intestinal dysbiosis that could be related to the onset of atherosclerosis. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:9943158. 10.1155/2022/9943158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu J, Bonder MJ, Cenit MC, Tigchelaar EF, Maatman A, Dekens JA, et al. The gut Microbiome contributes to a substantial proportion of the variation in blood lipids. Circ Res. 2015;117(9):817–24. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun Y, Fu D, Wang YK, Liu M, Liu XD. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and its association with lipid profiles. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2016;117(9):521–4. 10.4149/bll_2016_103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Izhari MA, Al Mutawa OA, Mahzari A, Alotaibi EA, Almashary MA, Alshahrani JA, et al. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) Infection-Associated dyslipidemia in the Asir region of Saudi Arabia. Life (Basel). 2023;13(11):2206. 10.3390/life13112206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimamoto T, Yamamichi N, Gondo K, Takahashi Y, Takeuchi C, Wada R, et al. The association of Helicobacter pylori infection with serum lipid profiles: an evaluation based on a combination of meta-analysis and a propensity score-based observational approach. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0234433. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim DY, Ko SH. Common regulators of lipid metabolism and bone marrow adiposity in postmenopausal women. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(2):322. 10.3390/ph16020322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pourmontaseri H, Bazmi S, Sepehrinia M, Mostafavi A, Arefnezhad R, Homayounfar R, et al. Exploring the application of dietary antioxidant index for disease risk assessment: a comprehensive review. Front Nutr. 2025;11:1497364. 10.3389/fnut.2024.1497364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miernyk KM, Bruden D, Rudolph KM, Hurlburt DA, Sacco F, McMahon BJ, et al. Presence of CagPAI genes and characterization of VacA s, i and m regions in Helicobacter pylori isolated from Alaskans and their association with clinical pathologies. J Med Microbiol. 2020;69(2):218–27. 10.1099/jmm.0.001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, et al. European Helicobacter study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht IV/ Florence consensus report. Gut. 2012;61(5):646–64. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh RK, McMahon AD, Patel H, Packard CJ, Rathbone BJ, Samani NJ. Prospective analysis of the association of infection with CagA bearing strains of Helicobacter pylori and coronary heart disease. Heart. 2002;88(1):43–6. 10.1136/heart.88.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Wang W, Gong R, Yao H, Fan M, Zeng J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori alleviates lipid metabolism deterioration: a large-cohort propensity score-matched analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2022;21(1):34. 10.1186/s12944-022-01639-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adachi K, Mishiro T, Toda T, Kano N, Fujihara H, Mishima Y, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on serum lipid levels. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2018;62:264–9. 10.3164/jcbn.17-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elkhodary NM, Farrag KA, Elokaby AM, El-Hay Omran GA. Efficacy and safety of 7 days versus 10 days triple therapy based on levofloxacin-dexlansoprazole for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: A pilot randomized trial. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52(5):356–64. 10.4103/ijp.IJP_364_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.