Abstract

Background

Diversity and race-concordant relationships contribute to improved patient experiences and outcomes. In contrast, the representation of underrepresented in medicine (URiM) individuals in different medical specialties is declining. The essential pathway to improving diversity within the future workforce centers around the inclusion of a diverse cohort of medical students. We aimed to examine the diversity of medical school applications and admissions across sex, race and ethnicity over the past decade.

Methods

This study used data from the Association of American Medical Colleges from 2015 to 2024. URiM individuals refer to minority populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession, including Black, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHPI). Diversity representation was measured using the representation index.

Results

There was an increasing trend in medical school applicants among females but a decreasing trend among males. The number of Asian female applicants increased significantly (51.33%), while the numbers of Black (29.74%) and Hispanic (14.98%) female applicants also showed notable upward trends. Matriculation rates for Black females (mean: 33.64%; SD: 2.28%) and overall URiM females (mean: 35.94%; SD: 2.02%) have consistently remained below White females (mean: 44.22%; SD: 2.66%), Asian females (mean: 43.57%; SD: 2.59%), and the national average for females (mean: 40.96%; SD: 2.05%) over the past decade. The findings indicate that all racial and ethnic groups were underrepresented among both applicants and matriculants over the last decade, with the exception of Asian individuals. The representation index between matriculants and applicants among Black females (-1.46 vs. -1.19; P < 0.001) is widening, which may help explain the underrepresentation discrepancy for overall URiM females (-2.09 vs. -1.83; P < 0.001).

Conclusion

This study highlights both progress and persistent challenges in achieving racial and ethnic diversity in U.S. medical education. While female and URiM applicant numbers have increased, matriculation disparities remain, especially among Black and URiM females. The widening representation gap between applicants and matriculants underscores structural barriers that continue to hinder equity in medical school admissions. A more inclusive physician workforce should begin with meaningful reform in how future doctors are recruited, supported, and selected.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07498-9.

Keywords: Diversity, Medical school applications and admissions, Disparity, Matriculation

Introduction

The urgent and ongoing national demand for diversity within the physician workforce is underscored by the fact that diversity and race-concordant relationships contribute to improved patient experiences and outcomes [1]. In contrast, the representation of underrepresented in medicine (URiM) individuals—racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population, as defined by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) [2]—in different medical specialties is declining, while diversity in the U.S. population continues to increase [3].

In The Difference [4], Scott Page expands the concept of diversity beyond identity markers, emphasizing instead cognitive diversity—the differences in how people think, process information, and solve problems. He identifies four key dimensions: perspectives, interpretations, heuristics, and predictive models. These dimensions shape how individuals perceive problems, categorize information, generate solutions, and anticipate outcomes. From this view, diversity in medicine should not be seen solely as increasing representation but as cultivating a range of cognitive approaches that strengthen collaboration, innovation, and patient care.

While medical institutions and healthcare systems have evolved over the years in terms of inclusiveness, evidence suggests there is still much work to be done. In a report released by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 56% of active physicians in the U.S. were White, and 64.1% were male in 2018 [5]. This metric was representative of the national population of White Americans at the time [6]. However, females were grossly underrepresented despite outnumbering males during this time [6]. In addition, Black Americans made up only 5% of all active physicians [5]. This issue is not solely about the numbers, it’s about the marginalized patients who are negatively impacted by the lack of representation in their healthcare team. These populations routinely face health disparities resulting in increased mortality and morbidity [7]. For example, data collected in 2021 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that Black women experience the highest rates of infant mortality at 10.6 deaths per 1,000 live births [8]. This is twice the national rate of 5.4 deaths [8]. Additionally, Black adults are estimated to have nearly twice the risk of suffering from a stroke when compared to their white counterparts and report the highest rates of stroke-related death [9]. These are just a couple of examples of the health inequities affecting minority groups today, and even more research is needed to comprehensively evaluate the economic and public health impact.

There is much discussion focused on developing plausible solutions to this issue with a popular strategy being to increase the diversity and cultural competency of the nation’s health-care system. Evidence shows that diverse teams reduce health disparities and often lead to improved patient outcomes and satisfaction [10]. However, in order to build these teams, we must prioritize the recruitment, matriculation, and education of a diverse cohort of medical students. The AAMC reinforces this sentiment in their strategic action plan by stating their intention to “diversify tomorrow’s doctors.” [11] This action item highlighted the underrepresentation of Black men, American Indians, and Alaska Natives in medical school especially, and made a commitment to “significantly increase the diversity of medical students.” [11] This is representative of the increased time, effort, and resources being put in by medical schools towards creating a more diverse student population.

Unfortunately, there has been minimal change in the ethnic and cultural composition of medical students despite these efforts. In the 2022–2023 academic year, individuals identifying as either American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) or Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHPI) accounted for less than 1% of the total students enrolled in medical school in the U.S. while Black and Hispanic students represented approximately 8.3% and 6.8% of total enrollement respectively [12]. These numbers have roughly remained the same since 2018, as reported by the AAMC, indicating the matriculation rates of these underrepresented groups have remained stagnant [12].

The essential pathway to improving diversity within the future workforce centers around the inclusion of a diverse cohort of medical students. Therefore, in this study, we strived to evaluate the demographic makeup of medical school applications and admissions over the past 10 years in comparison to the national population with the goal of assessing diversity in academic medicine.

Methods

Data sources

This study used data from the AAMC FACTS tables [13] from 2015 to 2024. The AAMC FACTS tables provide comprehensive information on U.S. medical school applicants, matriculants, enrolled students, and graduates, along with data on MD-PhD students and residency applicants. In this study, we used AAMC FACTS tables data from “Table A-12: Applicants, First-Time Applicants, Acceptees, and Matriculants to U.S. MD-Granting Medical Schools by Race/Ethnicity (Alone) and Gender”.

Definition of variables

Based on AAMC FACTS tables, self-reported racial and ethnic classifications included 1) American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN), 2) Asian, 3) Black or African American, 4) Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish Origin, 5) Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHPI), 6) White, and 7) Others. According to “Table A-12” from AAMC FACTS tables, individuals who selected more than one race/ethnicity are counted in “Multiple Race/Ethnicity”, which was included in “Others” group in our study. In our study, URiM individuals refer to minority populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession, including Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHPI.

In our study, only individuals who reported their legal sex as either male or female were included because applicants who selected “Another Gender Identity” or who declined to report their gender are not included in the publicly available data.

Diversity representation was measured using the representation index, calculated as the ratio of the proportions of each racial and ethnic group relative to their share in the U.S. population based on the Census data [14]. Specifically, the representation index for each racial and ethnic group in each year is calculated as:

proportions of applicants and matriculants/proportions in the U.S. population.

If the index is less than 1, the index is recalculated as:

proportions in the U.S. population/proportions of applicants and matriculants × (−1).

A value greater than 1 indicates overrepresentation, meaning the group is more prevalent in the applicant or matriculant pool than in the general population. In contrast, a value less than −1 indicates underrepresentation, where the group is proportionally less represented than expected based on their population share. For example, a representation index of −2 suggests that the group’s share in the applicant pool is only half of their share in the U.S. population.

Because race‑specific U.S. Census estimates for 2024 have not yet been released, we calculated the 2024 representation index using the 2023 Census data.

Statistical analysis

We utilized descriptive statistics to summarize the data. Trend analysis was conducted using linear regression to evaluate changes in the representation index over time. T-tests were used to compare representation index values between applicants and matriculants across groups. A two-sided p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

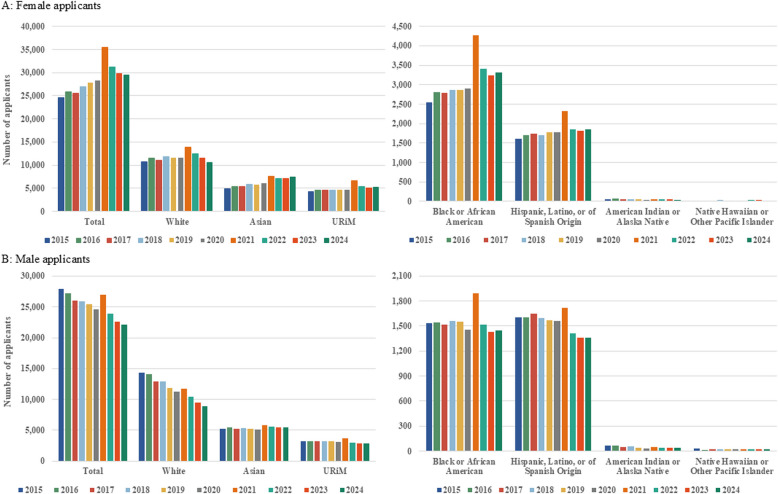

Overall, there was an increasing trend in medical school applicants among females but a decreasing trend among males. (Fig. 1) The total number of female applicants increased from 24,608 in 2015 to 29,528 in 2024, reaching a peak of 35,438 in 2021. (Fig. 1A) Over the past decade, the number of Asian female applicants increased significantly (51.33%), while the numbers of Black (29.74%) and Hispanic (14.98%) female applicants also showed notable upward trends. (Fig. 1A) The number of White female applicants remained relatively stable over time, and the number of AIAN and NHPI female applicants stayed consistently low throughout the period. (Fig. 1A) URiM female applicants increased by 23.09% from 2015 to 2024. (Fig. 1A) In contrast, male applicants decreased from 27,927 in 2015 to 22,088 in 2024. (Fig. 1B) The declining trend was observed among male applicants across all racial and ethnic groups except Asian males, whose numbers exhibited a slight increase (6.42%) over the decade. (Fig. 1B) URiM male applicants decreased by 11.34% from 2015 to 2024. (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Trends in the numbers of applicants by sex, race and ethnicity. URiM: underrepresented in medicine

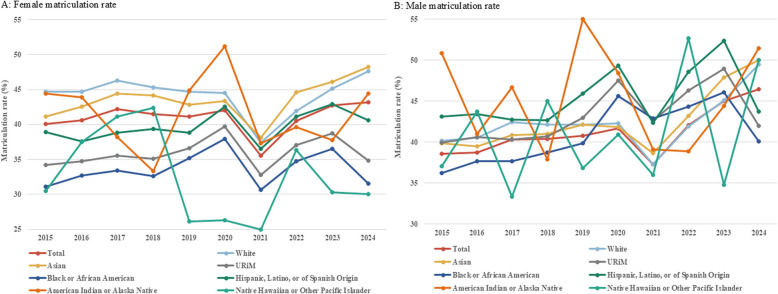

Despite heightened enthusiasm for medical school applications, matriculation rates for Black females (mean: 33.64%; SD: 2.28%) and overall URiM females (mean: 35.94%; SD: 2.02%) have consistently remained below White females (mean: 44.22%; SD: 2.66%), Asian females (mean: 43.57%; SD: 2.59%), and the national average for females (mean: 40.96%; SD: 2.05%) over the past decade. (Fig. 2A) Additionally, male applicants consistently exhibited higher matriculation rates than female applicants across all racial and ethnic groups, with a national average of 41.14% (SD: 2.70%). (Fig. 2B) URiM male applicants had a higher average matriculation rate (mean: 43.20%, SD: 3.08%), particularly among Hispanic (mean: 45.42%, SD: 3.32%) and AIAN (mean: 45.37%, SD: 5.71%) individuals. (Fig. 2B) Notably, matriculation rates hit their lowest point in 2021 and subsequently rebounded for all racial and ethnic groups, except URiM male individuals, especially Black males. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Trends in matriculation rates by sex, race and ethnicity. URiM: underrepresented in medicine

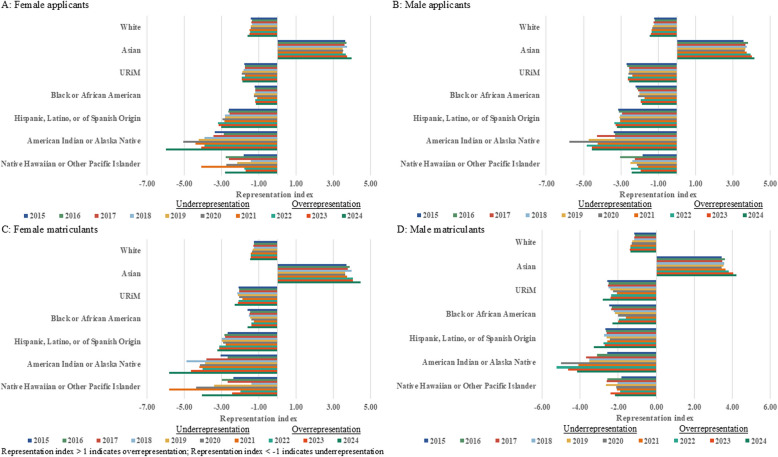

To assess diversity in medical school applicants and matriculants, we calculated the representation index. The findings indicate that all racial and ethnic groups were underrepresented among both applicants and matriculants over the last decade, except Asian individuals whose representation showed an increasing trend. (Fig. 3) The representation index significantly declined over time for the total group (P < 0.05), except among male applicants, and all White subgroups exhibited a consistent downward trend in representation (P < 0.05). (Fig. 3 & Supplementary Table 1) A significantly higher representation index was observed among matriculants compared to applicants in the total group, White individuals, Asian females, URiM males, and Hispanic males (P < 0.05). (Fig. 3 & Supplementary Table 2) It is concerning that the representation index between matriculants and applicants among Black females (−1.46 vs. −1.19; P < 0.001) is widening, which may help explain the underrepresentation discrepancy for overall URiM females (−2.09 vs. −1.83; P < 0.001). (Fig. 3 & Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Trends in the diversity representation in sex, race and ethnicity compared with the U.S. Census. URiM: underrepresented in medicine. Representation index > 1 indicates overrepresentation; Representation index < −1 indicates underrepresentation

Discussion

This study reveals several important trends in medical school diversity over the past decade. While the COVID-19 pandemic may disrupt many professionals, our study provides empirical evidence that it may catalyze interest in medical education [15]. We found a notable increase in the number of URiM female applicants to medical schools following COVID-19 (in 2021), which holds great promise for enhancing the representation of minority physicians in future clinical practice. However, our study suggests for the first time that this catalyzing effect may diminish gradually over time.

While the number of female applicants has steadily increased, particularly among Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals, the number of male applicants has declined, with decreases observed across all racial and ethnic groups except Asian males. Despite growing interest in medical education, female applicants, especially Black and URiM women, continue to experience lower matriculation rates compared to their White and Asian counterparts. Male applicants generally show higher matriculation rates, with URiM men, particularly Hispanic and AIAN individuals, having among the highest rates. Representation index analysis highlights persistent underrepresentation for nearly all groups except Asians, whose presence has steadily increased.

URiM individuals continue to face inadequate representation in medical education. While the number of Black female applicants has increased in recent years, bringing their representation among applicants closer to their demographic share in the U.S. population, their representation among matriculants remains significantly lower. We found that the average representation index for Black female applicants and matriculants is −1.19 and −1.46 over the last decade, representing a 22.69% relative difference, and indicating a continued, relatively considerable loss of potential Black female matriculants. When applied to national applicant pools, this can translate into a significant reduction in the number of URiM individuals entering medical school each year, suggesting a widening representation gap, and underscoring structural barriers that continue to hinder equity in medical school admissions. Although perfect parity between applicant and matriculant pools is not necessarily expected due to the multifactorial nature of admissions decisions, the persistent gap observed for Black and other URiM females stands in contrast to patterns seen among White and Asian female applicants, who show higher representation at the matriculation stage. This disparity highlights a widening underrepresentation gap in admissions outcomes.

It is reported that the group of individuals in high school with intentions to pursue a career in medicine is much more diverse than those who are matriculated by medical school, and those who leak out most are from groups least represented in medicine [16]. Our study found that on the path to medical education, URiM, particularly Black females, are experiencing disproportionate attrition between the applicant and matriculant stages. This reflects broader concerns about the “leaky pipeline”, a term used as a metaphor to describe the attrition of women in science and medicine who leave the academic career path, even as they begin to gain traction and increase their presence in the field [17]. Many factors can contribute to the “leaky pipeline”, including restricted access to quality education, limited mentoring and role models, biases and stereotypes within standardized testing and evaluation, as well as underrepresentation and isolation within the realm of academic medicine [18, 19]. Over the long run, it may widen the diversity gap within the physician workforce. It is important for medical educators to develop strategic approaches to address this “sieve” after the U.S. Supreme Court ended race-conscious admissions programs to improve diversity in medical schools.

A meaningful change is needed within these institutions, with the dire need for diversity and inclusion being the impetus. An organization is more likely to successfully implement this change when it first establishes diversity and inclusion as a core value and fully incorporates it into its mission statement [20, 21]. In addition, it is important that all members of the organization are fully involved in discussions and actions pertaining to this matter [20, 21]. This mission can then be carried out using various initiatives, with evaluation done periodically to assess progress [21]. One suggestion involves actively entering local communities to interact with youth from these underrepresented groups in an effort to inspire an early interest in the medical field [21, 22]. These recruitment efforts can also be applied to minority undergraduate students with an interest in the health field [22].

Several schools have accomplished this by creating outreach activities, pathway programs, and mentorship programs that support interactions between URiM faculty and students. Outreach activities are typically periodic, unconnected events that may include medical college admission test (MCAT) preparation sessions, mock interviews, and campus visits catered towards this population [22]. However, pathway and mentorship programs are a series of experiences occurring over varied lengths of time aimed at easing the progression from high school or college to medical school [22]. When developing these programs, it is essential that institutions focus on providing support that will aid in overcoming the major challenges faced by these individuals [22].

Furthermore, several tactics can be employed to ensure a fair, unbiased application and interview process. In a publication released by Johns Hopkins University Press, the admissions committee reported success in increasing the number of URiM matriculants when they introduced anonymous voting of applicants, involved a large group of faculty in the initial screening process, and utilized a holistic review process [20]. These strategies were centered around reducing individual biases and encouraging a more comprehensive view of each applicant [20].

The impact of diversity within the faculty and leadership of medical schools on URiM matriculation must also be explored. Culturally diverse teams often demonstrate an increased capacity to develop creative solutions and remain in tune with the communities they serve [23]. However, evidence shows that leaders in most medical institutions are highly unrepresentative of the overall U.S. population, with a recent study revealing that underrepresented minorities accounted for only 11% of medical school deans [24]. The same phenomenon is observed when analyzing the proportion of URiM faculty in academic medicine. As a result, these faculty often face a “minority tax” which may manifest as a disproportionate workload relating to diversity initiatives and committee work [25]. These circumstances habitually lead to burnout and even leaving the field of academic medicine altogether [25]. Therefore, prioritizing the hiring of culturally and ethnically diverse individuals into these positions will provide new ideas and fresh perspectives from which to tackle this issue. Overall, increasing diversity in academic medicine is a task that will require dedication and a multidimensional approach. However, it is a worthy endeavor projected to create a more dynamic learning environment for students and faculty alike while providing the foundation of a physician workforce representative of the diverse patient population it serves.

Previous work by Morris et al. (2021) [26] documented four decades of persistent racial and gender inequities in U.S. medical‑school enrollment and thus provides an essential historical benchmark for diversity research. Building on their foundation, our study offers new insights. First, by analyzing the most recent decade of data (2015–2024), we captured post‑COVID‑19 dynamics and the early effects of the Supreme Court’s decision on race‑conscious admissions, revealing a sharp but short‑lived surge in URiM female applications in 2021. Second, we compare the representation index between applicants and matriculants to quantify differences at the admissions stage, highlighting the persistent gap observed for Black and other URiM women. Third, we treat URiM as a distinct analytic category, enabling a comprehensive assessment of trends that disproportionately affect groups historically underrepresented in medicine. These additional insights provide updated, policy‑relevant evidence to inform current diversity initiatives in medical education.

This study has several limitations. First, the use of aggregate data prevents adjustment for individual-level academic metrics such as MCAT scores and GPA, which are important determinants of medical school admissions. Second, the analysis lacks intersectional demographic detail, such as socioeconomic status, immigrant background, which may significantly influence both application and matriculation outcomes. Third, there is a possibility of underreporting or misclassification in self-reported race and ethnicity data, which may bias representation estimates. Fourth, our use of overall U.S. Census population data as the denominator may overestimate underrepresentation, as it does not restrict the comparison to age-eligible individuals (e.g., typical applicant-age population). Future research should leverage individual-level, longitudinal data to control for academic and socioeconomic variables and explore how intersecting identities shape pathways to medical education. Additionally, incorporating age-adjusted population comparisons and exploring structural and institutional-level factors will provide a more nuanced understanding of representation gaps.

Conclusion

This study highlights both progress and persistent challenges in achieving racial and ethnic diversity in U.S. medical education. While female and URiM applicant numbers have increased, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, matriculation disparities remain, especially among Black and URiM females. The widening representation gap between applicants and matriculants underscores structural barriers that continue to hinder equity in medical school admissions. Informed by prior research [20–22], addressing these disparities requires a sustained, institution-wide commitment to diversity, equitable admissions practices, and long-term investments in outreach, mentorship, and leadership representation. A more inclusive physician workforce should begin with meaningful reform in how future doctors are recruited, supported, and selected.

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

GL, ML, and ZKL were involved in conceptualizing this study. ML and XJ analyzed the data included in this study. All authors contributed original writing, editing, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center institutional review board reviewed the study protocol and granted an exemption from full review. Informed patient consent was also waived because the study was a secondary analysis of deidentified data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Minghui Li, Email: mli54@uthsc.edu.

Jing Yuan, Email: jingyuan@um.edu.mo.

Z. Kevin Lu, Email: lu32@mailbox.sc.edu.

References

- 1.Schoenthaler A, Ravenell J. Understanding the Patient Experience Through the Lenses of Racial/Ethnic and Gender Patient-Physician Concordance. JAMA Netw Open. Nov 2 2020;3(11):e2025349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Unique Populations. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/career-development/affinity-groups/gfa/unique-populations

- 3.Lett E, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0207274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page S. The Difference -- a book by Scott Page. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.stevedenning.com/radical-management/the-difference-by-scott-page.aspx

- 5.Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019.https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019

- 6.Population. USFacts. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://usafacts.org/data/topics/people-society/population-and-demographics/population-data/population/

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, et al., eds. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017. [PubMed]

- 8.Infant Mortality. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/infant-mortality/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm

- 9.Stroke Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm

- 10.Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(4):383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A Healthier Future for All: The AAMC Strategic Plan. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/about-us/strategic-plan/healthier-future-all-aamc-strategic-plan

- 12.2023 FACTS: Enrollment, Graduates, and MD-PhD Data. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/2023-facts-enrollment-graduates-and-md-phd-data

- 13.FACTS. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/facts

- 14.National Population by Characteristics: 2020-2024. U.S. Census Bureau. Updated April 9, 2025. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-national-detail.html

- 15.Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The Transformational Effects of COVID-19 on Medical Education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For minorities, road to medical school a leaky pipeline. American Medical Association (AMA). Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/education/medical-school-diversity/minorities-road-medical-school-leaky-pipeline

- 17.Jackson MA. The Leaky Pipeline in Academia. Mo Med May-Jun. 2023;120(3):185–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr DA, Gonzalez ME, Wanat SF. The leaky pipeline: factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):503–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Upshur CC, Wrighting DM, Bacigalupe G, et al. The health equity scholars program: innovation in the leaky pipeline. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(2):342–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capers Q, McDougle L, Clinchot DM. Strategies for achieving diversity through medical school admissions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanford FC. The Importance of Diversity and Inclusion in the Healthcare Workforce. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(3):247–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons M, Caldwell MT, Alvarez A, et al. Physician Pipeline and Pathway Programs: An Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(4):514–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeBlanc C, Sonnenberg LK, King S, et al. Medical education leadership: from diversity to inclusivity. GMS J Med Educ. 2020;37(2):Doc18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nobles A, Martin BA, Casimir J, et al. Stalled progress: medical school dean demographics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(1):163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell KM. The Diversity Efforts Disparity in Academic Medicine. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, et al. Diversity of the National Medical Student Body - Four Decades of Inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(17):1661–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.