Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to assess effect of sleep disturbance, cancer-related fatigue, and depression on the quality of life (QoL) of breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Method

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted at an oncology hospital in Cairo, Egypt, from November 2024 to February 2025. A total of 253 breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy were recruited through convenience sampling. Data were collected using validated instruments: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B), Cancer Fatigue Scale (CFS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression. Linear regression models were employed to analyze the relationships between sleep disturbance, fatigue, depression, and QoL.

Results

Findings revealed that 99.2% of patients experienced fatigue, 87.4% reported poor sleep, and 93.3% exhibited depressive symptoms. Regression analysis demonstrated that sleep disturbance had the strongest negative impact on QoL (B = -1.506, p < 0.001), overshadowing both fatigue and depression. Correlation analysis further supported these findings, with sleep disturbance showing the highest negative correlation with QoL (r = -0.81, p < 0.001), followed by fatigue (r = -0.72, p < 0.001) and depression (r = -0.56, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Sleep disturbance, cancer-related fatigue, and depression are significantly associated with reduced QoL in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Among these factors, sleep disturbance appears to be the most influential. Interventions targeting sleep quality may help mitigate related psychological and physical challenges, thereby enhancing patients’ overall well-being.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-025-14538-6.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Quality of life, Sleep disorder, Fatigue, Depression, Chemotherapy

Introduction

Breast cancer is a leading health priority, being the most commonly diagnosed malignancy globally. In 2022, 2.3 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer, resulting in 670,000 fatalities worldwide. By 2050, the incidence of new cases and mortality rates will have risen by 38% and 68%, respectively [17, 33]. It is also the largest source of female cancer-related mortality [55]. A meta-analysis and systematic review in Egypt highlighted that breast cancer is the most frequent cancer among Egyptian women, accounting for 42% of cancers, and most patients come to the hospital at advanced stages [7]. Even though nearly 99% of breast cancer occurs in women, a minority (0.5–1%) also occurs in men. It may occur in women of any age group post-puberty, with the frequency rising with advancing age [53].

Advances in therapy have reduced breast cancer mortality dramatically and improved disease-free survival. However, attaining a satisfying quality of life (QoL) for patients remains difficult. The focus has now shifted towards measuring survivorship in regards to QoL, since cancer affects not just physical health but various aspects of a patient’s life [32]. Health-related QoL is a valuable outcome measure for cancer care, which provides informative data for patients as well as clinicians. QoL measurement helps in setting realistic expectations regarding the impact of treatments on well-being and daily function, identifies common problems that must be treated, and helps to assess the impact of therapies and supportive care interventions [25].

Quality of life (QoL) refers to an individual’s perception of their position in life, influenced by their cultural and value systems, personal goals, expectations, standards, and concerns [29]. It is often linked to overall life satisfaction and well-being. QoL is a multidimensional concept that includes physical health, psychological well-being—such as anxiety and depression levels—and social support [45].

Breast cancer is not solely a physical illness; it is also a condition deeply linked to psychosocial challenges [30]. Patients often experience a range of physical effects, including fatigue, pain, lymphedema, sexual dysfunction, and sleep disturbances [49]. Beyond these physical consequences, breast cancer can lead to psychological distress, manifesting as fear, anxiety, depression, and diminished life satisfaction [39]. The diagnosis and treatment process can intensify emotional distress, contributing to feelings of anxiety, depression, anger, uncertainty, and hopelessness [30]. These negative effects significantly impact both health and overall QoL [10]. Among the various treatment options for breast cancer, chemotherapy is particularly known for its severe side effects, which can profoundly affect a patient’s QoL and influence their willingness to continue treatment [35].

Studies highlight the significant impact of sleep disturbance, depression, and cancer-related fatigue well beyond the treatment phase of cancer. These symptoms are some of the most powerful predictors of QoL because they play a role in chronic insomnia, fatigue, and emotional distress. Insomnia and fatigue are exceptionally common among patients with breast cancer, as among other patients with chronic illnesses [16]. In addition, these symptoms go underdiagnosed and undertreated among patients with cancer, with consequent prolonged suffering and suboptimal well-being [16].

A study on 372 patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy revealed that 99.2% of them experienced fatigue, 87.4% reported poor sleep, and 93.3% exhibited depressive symptoms [26]. Another study also indicated that cancer fatigue has a significant impact on QoL [56]. This type of fatigue not only disrupts patients’ normal functioning in performing daily activities and maintaining working but also contributes to the development of low mood and depression, eventually interfering with both their quality of life as well as the effectiveness of the rehabilitation interventions [52]. Moreover, another research conducted by Akin and Kas Guner [2] examined the interrelation of QoL with cancer-related fatigue. It validated that cancer-related fatigue effectively diminishes cancer patients’ quality of life [2].

Depression is a significant health concern for breast cancer survivors and is associated with lower HRQOL [47]. In addition, two studies found that depression is correlated with a lower quality of life [23, 54]. Given the strong connection between these psychological and physical challenges, addressing sleep disturbances, fatigue, and depression is crucial for enhancing the well-being and recovery of breast cancer patients.

Cancer patients in Egypt encounter numerous psychosocial challenges that greatly affect their quality of life, similar to those in various other regions. A study at the Oncology Center of Mansoura University, which involved 175 cancer patients, revealed significant levels of psychological distress, including anxiety and depression [19]. case-control study conducted at the Minia Oncology Center, involving 400 participants, found significantly higher levels of moderate to severe depression, anxiety, and stress among cancer patients, underscoring the critical need for regular psychological screening in the cancer care [48]. Additionally, research involving 550 individuals recently diagnosed with cancer indicated that 46% faced significant distress, especially among those in the later stages of the disease. Major sources of distress encompass decisions related to treatment, personal issues, and anxiety about the future [1]. In a similar vein, a study with 200 women receiving treatment for breast cancer revealed a significant link between psychological distress and unmet supportive care needs [18].

While previous research has established individual links between sleep disturbances, fatigue, depression, and QoL, few studies have examined their combined effects using multivariate analysis. So, this study seeks to bridge this gap by analyzing how these three factors collectively influence QoL in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. By using linear regression models, this study aims to determine which factor exerts the greatest impact on QoL. Understanding these relationships will provide critical insights for healthcare providers, enabling them to develop targeted interventions that address not only cancer treatment but also the broader well-being of patients.

This study aims to assess the effect of cancer-related fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression on the QoL in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. By evaluating these factors, the study seeks to identify the strongest predictors of QoL, offering evidence to guide targeted interventions that can improve the overall well-being of patients during treatment.

Hypotheses

H1: Depression has a significant negative effect on the quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

H2: Cancer-related fatigue has a significant negative effect on the quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

H3: Sleep disturbance has a significant negative effect on the quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

H4: Sleep disturbance, cancer-related fatigue, and depression together explain a substantial proportion of the variation in QoL.

H5: Patients with a longer duration since diagnosis report higher levels of depression compared to those more recently diagnosed.

Methods

Research design

A descriptive cross-sectional study using a self-report questionnaire was conducted from November 2024 to February 2025 and reported according to the guidelines for Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).

Study setting

This study was conducted at an oncology hospital, a governmental facility in Cairo, Egypt, affiliated with the Ministry of Health, which provides various medical services, including chemotherapy, to cancer patients.

Sample size

To calculate the required sample size for the study, we applied the T-test Independent Power formula, a widely used approach to determining sample size by effect size, statistical power, and significance level [50]. Employing an effect size of −0.388 from a prior study [51], 85% power, and 0.05 significance level, we estimated a minimum sample size of approximately 120 participants. Because there are multiple predictors sleep disturbance, cancer-related fatigue, and psychological distress—while there is just one outcome variable (quality of life), we had a potential 15% rate of attrition in mind. This re-weighting increased the required sample size to about 138 patients in order to cover for missing data and dropouts. However, in case of complex statistical models, such as latent growth modeling or structural equation modeling, a larger sample size (usually ranging from 200 to 300) is recommended in order to enhance the validity of the results [42]. The ultimate sample size was thus set at 253 patients.

Participants

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling method, targeting women diagnosed with breast cancer at the designated hospital. Eligible patients were identified through clinical consultation and review of medical records; selection was non-random and based on patient availability and willingness to participate during scheduled chemotherapy visits. This approach was adopted due to practical constraints, including limited time, resources, and patient flow during the data collection period. It enabled efficient access to patients while maintaining feasibility in reaching the required sample size. The inclusion criteria were that the participants were females aged 18–65 years, diagnosed with breast cancer, undergoing chemotherapy, with normal mental and cognitive status, and able to cooperate throughout treatment, follow-up, and completion of questionnaires. The exclusion criteria were a history of recurrence of breast cancer “Patients with recurrent disease may have different psychological and physical symptom profiles, which could confound the results and reduce comparability with those undergoing first-time treatment”, other concurrent primary cancers “The presence of other cancers could introduce additional sources of fatigue, depression, or sleep disturbance unrelated to breast cancer or its treatment.”, and pregnancy “Pregnancy could independently affect sleep quality, fatigue, mood, and quality of life, making it difficult to isolate the effects of cancer and chemotherapy”.

Eligible patients were approached in person at the outpatient chemotherapy unit during their scheduled treatment visits. After assessing eligibility through consultation with healthcare providers and reviewing medical records, the research team extended verbal invitations to 350 patients. The study’s purpose and procedures were explained in detail, and informed consent was obtained on-site from 307 patients, resulting in a response rate of 87.7%. Of those, 18 patients withdrew before data collection, 16 did not complete the interview, and 20 were excluded due to missing data. Consequently, the final sample analyzed consisted of 253 patients.

Data collection instruments

Patient interview questionnaire

Characteristics of nurses, such as age, Marital status, Employment status, Cancer stage, and Months since diagnosis [31].

Sleep disturbance

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), developed by Buysse et al. [9], was utilized to evaluate sleep disturbances. This 19-item instrument measures seven key components of sleep quality: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The total sleep quality score is derived from these seven components, ranging from 0 to 21. Each element is rated on a scale from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty), with higher scores indicating more significant sleep disturbances. A global PSQI score above 5 is generally considered indicative of poor sleep quality [22]. The Arabic version of the PSQI has demonstrated reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.77 [3]. Additionally, a previous study reported a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.89 for the scale [51].

Quality of life

The Quality of life was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B), it was developed by Cella [12], a five subscale questionnaire with 37 items: physical well-being (range 0–28), social/family well-being (range 0–28), emotional well-being (range 0–24), functional well-being (range 0–28), and a breast cancer-specific subscale (range 0–40). Each is scored on an ordinal scale with 5 items ranging from 0 to 4, such that the total score ranges from 0 to 144, in which higher is better. The FACT-B has demonstrated superior internal consistency, and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.951 [51].

Cancer fatigue scale

The scale was employed to evaluate fatigue in cancer patients, offering insights into its impact on their physical, emotional, and cognitive health, it was developed by Okuyama et al. [43]. It has 15 items and three subscales: physical (7 items), affective (4 items), and cognitive (4 items). All the items are scored from 1 to 5, and the range of total scores is from 15 to 75. Higher scores on the CFS indicate greater fatigue, which may interfere with the functioning and engagement in daily activities by the patient. In another research, the scale was highly consistent internally, as shown by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 [43].

Depression- PHQ-9

The PHQ-9 is a nine-item tool used to screen for depression. It was developed by Kroenke et al. [34]. It requires patients to reflect on how frequently they experienced each symptom over the past two weeks. Response options range from “not at all” (0) to “nearly every day” (3). The total score spans from 0 to 27, with thresholds of ≥ 5, ≥10, and ≥ 15 corresponding to mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively [34]. The PHQ-9 has been shown to have strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of ≥ 0.84 [27].

Data collection

Structured interview questionnaires were conducted with the studied patients to collect data for this study. This process took place from November 2024 to February 2025. Patients were identified through the hospital’s oncology outpatient chemotherapy unit. Eligible participants were screened based on their medical records, which included documented diagnosis of breast cancer, treatment status, and clinical eligibility confirmed by the attending oncologist. Details about the study’s goals, possible advantages, and participants’ rights were explained to the patients before participating in the study. We divided the patients into small groups to facilitate conducting the interview for collecting the data as characteristics of patients, Sleep disturbance, Quality of life, Cancer fatigue scale, and Depression- PHQ-9. All structured interviews were conducted in the outpatient chemotherapy unit of the oncology hospital. Patients were approached and interviewed in a private area within the unit while waiting for or immediately after receiving their scheduled chemotherapy sessions. This setting provided a familiar, non-intrusive environment and ensured patient comfort and privacy during data collection. The researcher was available throughout the data collection period to address any questions, ensuring participants fully understood the study’s objectives. Patients who participated in the pilot study were included in the primary study sample. Finally, incomplete questionnaires were excluded, and any missing data were corrected before analysis.

Validity and reliability

The researchers evaluated the reliability of the study instruments by employing Cronbach’s alpha coefficient test with a statistical significance threshold of p < 0.05. Tool 1 (Pittsburgh sleep quality Index (PSQI)) and Tool 2 (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B)), Tool 3 (Cancer fatigue scale), and Tool 4 (Depression- PHQ-9) exhibit reliability, surpassing the permissible cutoff of ≥ 0.7 for study groups’ values, with α = 0.819, 0.862, 0.813 and 0.846, respectively. Pilot testing of the survey instruments with a representative sample was conducted to assess the items for intelligibility and practicality, identify potential obstacles and concerns during data collection, and test the time required to complete the tools. Pilot study participants were included in the study sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to code and enter the collected data. Descriptive statistics were used to assign demographic characteristics into numbers, that is, frequency distributions, means, standard deviations, and percentages. Quantitative data were presented as values and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the data distribution. A correlation heatmap was generated to visually display correlations between sleep disturbance, quality of life (QoL), cancer-related fatigue, and depression. A longitudinal analysis was conducted to compare the correlations between QoL and key health indicators in patients with breast cancer. To explore these correlations better, a Python script was used to generate a correlation heatmap using synthetic longitudinal data. The script employed Pandas, NumPy, and Seaborn/Matplotlib to manipulate and visualize the data. Furthermore, linear regression analysis was employed to assess the relationship between QoL and significant independent variables, such as sleep disturbance, depression, and cancer fatigue. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

In order to evaluate possible selection bias stemming from participant drop out, we performed sensitivity analysis of the 253 patients completers compared to the 54 patients non-completers (withdrawn, incomplete interviews, or missing data). A set of independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests were performed for each and compared for within group differences: age, cancer stage, employed, marital status and months since diagnosis. The analysis did not find statistically significant differences in age (p = 0.66), cancer stage (p = 0.98), employment status (p = 0.85), months since diagnosis (p = 0.57), Marital Status (p = 0.90), see Table 1 in appendix. Based on these results, the final sample is likely representative of the original group, and attrition is unlikely to cause systematic bias on study outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studied breast cancer patients (n = 253)

| Characteristics | no. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 46.3 (11.7) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 77 | 30.4 |

| Married | 140 | 55.3 |

| Divorced | 24 | 9.5 |

| Widow | 12 | 4.8 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employee | 119 | 47 |

| Unemployed | 88 | 34.8 |

| Retired | 46 | 18.2 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| I | 52 | 20.6 |

| II | 71 | 28.1 |

| III | 85 | 33.6 |

| IV | 45 | 17.7 |

| Months since diagnosis | ||

| Mean (SD) | 32.52 (15.6) | |

SD Standard Deviation

Results

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 253 patients with breast cancer in this study. The mean age of the participants was 46.3 years (SD = 11.7). The majority were married (55.3%), followed by single (30.4%), divorced (9.5%), and widowed (4.8%). Regarding employment status, nearly half of the participants were employed (47%), 34.8% were unemployed, and 18.2% were retired. The distribution of cancer stages showed that the largest proportion of patients was in Stage III (33.6%), followed by Stage II (28.1%), Stage I (20.6%), and Stage IV (17.7%). Additionally, the mean time since diagnosis was 32.52 months (SD = 15.6), indicating variability in the time since diagnosis.

The mean score for depression was 11.58 ± 2.86, with values ranging from 6 to 19, indicating moderate depression. The mean Cancer fatigue was 47.9 ± 8.03, with a range from 35 to 68, indicating a higher level of fatigue. The mean Quality of life mean was 58.11 ± 7.29, with a range from 43 to 81, indicating a poor quality of life. years was 11.05 ± 4.57, with a range from 4 to 19 years, indicating poor sleep (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean scores of depression, cancer fatigue, quality of life, and sleep disturbance (n = 253)

| Study Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 11.58 | 2.86 | 6 | 19 | Moderate |

| Cancer fatigue | 47.9 | 8.03 | 35 | 68 | High |

| Quality of life | 58.11 | 7.29 | 43 | 81 | poor |

| Sleep disturbance | 11.05 | 4.57 | 4 | 19 | Poor sleep |

SD Standard Deviation

According to the linear regression for quality of life of breast cancer patient (Table 3), Model 1 showed that depression (B −1.423, p = 0.000) had a significant adverse effect on quality of life, explaining 31.2% of the variation in quality of life (F = 113.9, p < 0.001). In model 2, cancer fatigue was entered (B = 0.567, P = 0.000). and depression (B −0.347, p = 0.000). The model explained 52.4% of the variation in the quality of life (F = 137.67, p < 0.001). In Model 3, Sleep disturbance (B = 1.506, P = 0.000), cancer fatigue (B −0.163, p = 0.399), and depression (B −0.236, p = 0.087) were included. The model explained 66.8% of the variation in the quality of life (F = 167.44, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that sleep disturbance exerts the most substantial impact on QoL, and when included, may overshadow the effects of fatigue and depression.

Table 3.

Linear regression for quality of life of breast cancer patients (n = 253)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Intercept | 74.61 | 1.5 | 0.000 | 89.31 | 1.9 | 0.000 | 68.97 | 2.53 | 0.000 |

| Depression | -1.423 | 0.13 | 0.000 | -0.347 | 0.150 | 0.000 | -0.236 | 0.138 | 0.087 |

| Cancer fatigue | -0.567 | 0.053 | 0.000 | -0.163 | 0.075 | 0.399 | |||

| Sleep disturbance | -1.506 | 0.144 | 0.000 | ||||||

|

R2=0.312, F=113.9, p 0.000 |

R20.524, F= 137.67, p 0.000 |

R20.668, F= 167.44, p 0.000 |

|||||||

F, p: f and p values for the model

B Unstandardized Coefficients, Beta Standardized Coefficients, t t-test of significance, SE Standard error

*Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05

The results are shown in Fig. 1. highlighted the intricate relationships between fatigue, depression, sleep disturbance, and quality of life in breast cancer patient, which indicated a negative correlation between sleep disturbance and quality of life (r = − 0.81, p < 0.001), fatigue and quality of life (r = − 0.72, p < 0.001), depression, and quality of life (r = − 0.56, p < 0.001). There was also a positive correlation between sleep disturbance and depression (r = 0.74, p < 0.001), fatigue, and depression (r = 0.68, p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between sleep disturbances and fatigue (r = 0.90, p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Correlation heatmap for sleep disturbance, quality of life, cancer fatigue, and depression

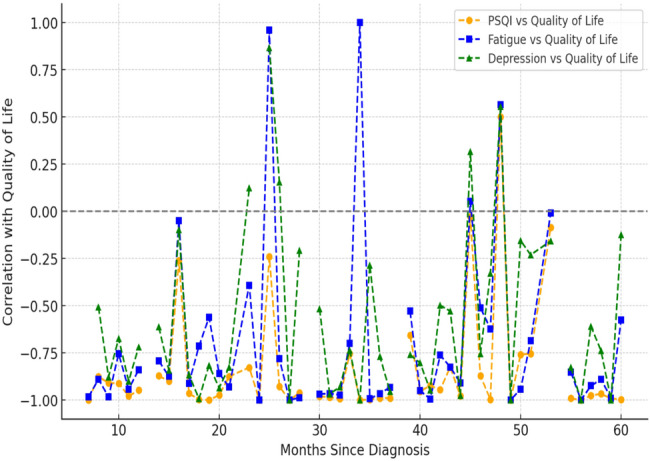

Sleep Disturbance (PSQI) vs. Quality of Life (Orange Line). The negative correlation between the PSQI and quality of life remained consistent regardless of time since diagnosis. This suggests that poor sleep quality consistently lowers quality of Life regardless of how long the patient has been diagnosed, indicating that sleep disturbances remain a long-term issue. Additionally, the Cancer Fatigue Scale vs. Quality of Life (Blue Line). Fatigue has the strongest negative correlation with Quality of Life, meaning that higher fatigue levels lead to significantly lower Quality of Life, showing that fatigue is a persistent issue affecting patients throughout their cancer journey. The magnitude of the correlation suggests that fatigue may be the most important predictor of Quality of Life in this dataset. Finally, the impact of depression (PHQ-9) on quality of life (represented by the green line) increases with time since the initial diagnosis. See more in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Correlations between quality of life and key health factors in breast cancer patients

Discussion

This study explores the impact of cancer fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depression on QoL among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. By assessing these variables, our research attempts to identify the best predictors of QoL, providing feedback that can inform targeted interventions towards enhancing patient wellness. While other studies have previously reviewed cyclic changes in fatigue, depression, sleep, and activity in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, this study is among the first to review how differences in these factors impact QoL compared with time since diagnosis.

The study findings revealed moderate level of depression (M 11.58 SD 2.86) potentially due to the psychological impact of cancer diagnosis, uncertainly about the future, and physical burden og chemotherapy, high level of cancer-related fatigue (M 47.9 SD 8.03) that reflects profound physical exhausting, likely exacerbated by chemotherapy’s side effects, significantly imparing patients’ ability to manage routine activities effectively, poor quality of life (M 58.11 SD 7.29) highlight how treatment related symptoms negatively influence pateints’ physical, emotional, and social well-being, reducing their capacity to engage fully in daily life and rehabilitation program.

Moreover, significant sleep disturbances (M 11.05 SD 4.57) underline the severity of insomnia and disturbed sleep patterns among breast cancer patients (n = 253) undergoing chemotherapy, potentially amplifying their fatigue and depressive symptoms. These results collectively indicate substantial physical, emotional, and ppsychological burdens affecting patients’ overall weel-being during their treatment.

These findings agree with previous studies that reported similar psychosocial problems in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. For instance, it has been reported that prevalence of moderate to severe fatigue during chemotherapy ranges from 26 to 60% [6], depressive symptoms are experienced by 20–39% of patients [40], insomnia is self-reported by 79% [44], and inactivity has been self-reported in 40–74% [8]. Furthermore, depression and anxiety were also determined to account for 18.8% and 12.8% of the variance in sleep quality, respectively [59]. Cho and Hwang [14] reported that the average anxiety score was 6.89 out of 21, and 15.0% of the patients possessed a moderate level of anxiety (above 11 points). Similarly, the average depression score was 6.60 out of 21, and 15.8% were diagnosed with a moderate level of depression.

Follow-up studies have shown that the occurrence of fatigue is as high as 46.3% [24], and worsening fatigue during both chemotherapy regimens [36]. However, outcomes are contrary to those of Yfantis et al. [57], which showed that the overall composite score for the functional scales of the QLQ-C30 illustrated a fairly good QoL and low-grade symptomatology following surgery. Also, research on university hospital in-patients has found higher quality care and lower mortality rates [5].

In our study, we conducted three regression models to determine how these factors contribute individually and collectively to QoL. In Model 1, the single variable of depression accounted for 31.2% of the variability in predicting QoL. This shows that extra depressive symptoms considerably decrease a patient’s perception of their QoL. In Model 2, both fatigue and depression were found to be significantly associated with QoL when cancer-related fatigue was added, which means that they could explain 52.4% of the variation. This reveals that fatigue plays a larger role in the impairment of QoL than depression, and both have a cumulative effect. Model 3, which focused on sleep disturbance, was added to the analysis, and the model confirmed a large part of the variance (R² = 0.668). In this full model, sleep disorders were shown to have the most intense negative link with QoL (B = −1.506, p < 0.001). It should be noted that the effects of both cancer fatigue (B = −0.163, p = 0.399) and depression (B = −0.236, p = 0.087) were no longer statistically significant once sleep disturbance was factored in. These results support sleep disturbance as the main factor, which is more important than the combined effects of fatigue and depression on QoL. Notably, the involvement of sleep deficiency was the most influential factor in the predictive model; its contribution substantially affected both depression and fatigue. Thus, poor sleep quality may be a central factor aggravating physical and psychological distress in patients.

The findings derived from the correlation heatmap further confirm the outcomes mentioned above and depict very negative interrelations between QoL and sleep disturbance (r = −0.81), fatigue (r = −0.72), and depression (r = −0.56). In addition, negative associations could also be observed between sleep disturbance, depression (r = 0.74), and fatigue (r = 0.90) at p value < 0.01., the latter emphasizes the combined nature of these conditions and also suggesting that these problems do not just appear separately but rather reinforce each other. To sum up, attending to sleep problems seems imperative in raising the life quality of breast cancer patients with chemotherapy. Interventions directed to improving sleep quality may lead to the relief of related symptoms like depression and fatigue, therefore putting a patient’s overall well-being on a more solid ground.

These findings are supported by various studies. For instance, Reyes-Gibby et al. [47] reported that depression was inversely related to HRQOL subscales for functioning, financial well-being, and general health, but was directly related to symptom severity. Similarly, studies have shown a negative relationship between depression and QoL [13]. Emre and Yılmaz [20] also observed that patients with breast cancer who reported poor sleep quality and high anxiety and depression were found to have a significantly worse quality of life, and such conditions further impaired their well-being.

In addition, research concerning the relationship between subjective sleep quality and QoL has all equated sleep disorders with lower QoL. This relationship has been observed in patient populations and control populations [36, 37, 38]. Regression analyses of anxiety and depression, with sleep quality as a factor, were significant. Of the sleep quality factors, daytime dysfunction explained the most for anxiety [14]. Also, low sleep quality, depression, and lower scores in QoL were strongly correlated with each other among breast cancer patients [46, 47, 58].

Furthermore, Al-Sharman et al. [4] found that sexual dysfunction, low sleep quality, depression, and anxiety were the predictors of QoL as identified by multiple regression analysis (p ≤ 0.05). Evidence in support of these results comes from research that also establishes depression deteriorates sleep quality [21]. Also, trends on disturbed sleep and tiredness related to cancer showed increasing was followed immediately by steady recuperation, whereas trends on QoL and psychological distress also showed a trend toward diminished effect as time passed on [51]. According to these findings, follow-up care and early psychological interventions should be implemented at the initial diagnostic stage by physicians to prevent high depression among breast cancer patients, ultimately improving their QoL [28, 41].

Poor sleep quality, fatigue, and depression all negatively impact QoL in cancer patients. Sleep disturbances remain a long-term issue, consistently reducing QoL. Fatigue has the most substantial negative effect, making it a key predictor of well-being. Depression tends to worsen in patients who diagnosed for a longer duration than newly diagnosed, playing an increasingly significant role in diminishing quality of life as patients progress through their cancer journey. It remains a persistent challenge and may intensify during extended cancer treatment. Addressing these factors collectively is crucial for improving patient outcomes.

These findings are in agreement with previous research, such as the study of Reyes-Gibby et al. [47], which followed the prevalence of depression over time with a general decline trend as years since treatment increased. Longitudinal variation has also been observed in the profound variations in fatigue, depression, sleep disturbances, and activity level. Fatigue increases, for instance, were strongly correlated with increases in depression prior to chemotherapy infusions [31]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the prevalence of depression decreases with greater time since treatment [11, 15].

Moreover, although the attrition rate for our study was 17.6%, we performed a sensitivity analysis comparing baseline traits for completers and non-completers. The groups did not differ statistically, thus suggesting selection bias is likely of little consequence. Still, we recognize this as a limitation and propose that future research employs methods to minimize attrition and enhance validation through prospective tracking aiming for greater representativeness.

Although the associations identified in this study align with findings from international research, the present study offers important contributions within the Egyptian context. Breast cancer patients in Egypt often present at more advanced stages, face limited access to specialized psychosocial services, and may experience cultural stigma surrounding mental health. By documenting the significant impact of sleep disturbance, fatigue, and depression on quality of life in this setting, the study highlights critical gaps in supportive care and underscores the need for integrating mental health and symptom management into routine oncology services. These findings can support evidence-based recommendations for local clinical practice, inform public health priorities, and guide the development of culturally appropriate psychosocial interventions in cancer care.

Limitation

While the study provides valuable insights, it is limited in that it relied on self-reporting, which may result in response bias. So, we suggested that further study should incorporate objective assessments of sleep patterns and fatigue levels to enhance accuracy. Additionally, the use of convenience sampling may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. However, to mitigate this concern, we performed a sensitivity analysis comparing completers (253 patients) and non-completers (54 patients) who excluded from the analysis on key demographic and clinical variables. The absence of statistically significant differences suggests that the final sample is broadly representative of the initial population approached for participation.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the triple burden of cancer-related fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression on the QoL among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. In addition, sleep disturbance had the most substantial impact on QoL, while fatigue remains a persistent challenge, and depression becomes more critical with patients who have been diagnosed for a longer duration than newly diagnosed. Comprehensive, multidisciplinary interventions targeting these factors are essential for enhancing patient well-being throughout their cancer journey.

Clinical implications

Sleep interventions are essential in improving QoL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and relaxation techniques may be beneficial. Fatigue management strategies, including energy conservation, physical activity, and nutritional support, are also essential. Counseling, support groups, and antidepressant therapy may help mitigate these effects. A multidisciplinary approach addressing fatigue, sleep quality, and mental health simultaneously may yield the most significant improvements in patients’ QoL.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R844), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Abbreviations

- PSQI

Pittsburgh sleep quality index

- FACT-B

Functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast

- CFS

Cancer fatigue scale

- PHQ-9

Patient health questionnaire-9

- STROBE

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

Authors’ contributions

Author Contributions: “Conceptualization”, Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim; Methodology, Nadia Mohamed Ibrahim Wahba, Saher Al Sabbah; validation, Amani Darwish, Abeer Yahia Mahdy Shalby; formal analysis, Rahmah Khubrani, Amal Elhaj Alawad, Sally Mohammed Farghaly; writing—original draft preparation, Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim, Nadia Mohamed Ibrahim Wahba, Saher Al Sabbah, Amani Darwish, Abeer Yahia Mahdy Shalby, Sally Mohammed Farghaly; Editing; Rahmah Khubrani, Amal Elhaj Alawad; statistical analysis. Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim, Sally Farghaly; Visualization: Nadia Mohamed Ibrahim Wahba, Saher Al Sabbah, Amani Darwish; Project administration: Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim, Abeer Yahia Mahdy Shalby; All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Also, all participated in preparing the manuscript.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Project number (PNURSP2025R844), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data availability

All relevant data are available within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was submitted and approved by local ethics committee at MTI university, reference number FAN/152/2024, All participating patients were provided comprehensive information about the study’s purpose, objectives, and potential benefits. The researchers emphasized the study’s voluntary nature, and patients could withdraw their participation without facing any consequences. Patients were required to provide written informed consent before participating in the study. Participation was entirely voluntary, and patients had the right to withdraw at any stage without any consequences. The collected data was coded to maintain confidentiality, ensuring no identifiable information was disclosed. Our study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki principle.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abd El-Aziz N, Khallaf S, Abozaid W, Elgohary G, Abd El-Fattah O, Alhawari M, Khaled S, AbdelHaffez A, Kamel E, Mohamed S. Is it the time to implement the routine use of distress thermometer among Egyptian patients with newly diagnosed cancer? BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1033. 10.1186/s12885-020-07451-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akin S, Kas Guner C. Investigation of the relationship among fatigue, self-efficacy and quality of life during chemotherapy in patients with breast, lung or gastrointestinal cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(1):e12898. 10.1111/ecc.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Maqbali M, Hughes C, Gracey J, Rankin J, Dunwoody L, Hacker E. Validation of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) with Arabic cancer patients. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2020;18(3):217–23. 10.1007/s41105-020-00258-w. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Sharman A, Al-Sarhan A, Aburub A, Shorman R, Bani-Ahmad A, Siengsukon C, Issa B, Abdelrahim W, Hijazi DN, H., Khalil H. Quality-of-life among women with breast cancer: application of the international classification of functioning, disability and health model. Front Psychol. 2024;15. 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1318584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Weissman NW, Person SD, Rousculp M, Canto JG, Bae S, Williams OD, Farmer R, Centor RM. Relationship of hospital teaching status with quality of care and mortality for Medicare patients with acute MI. JAMA. 2000;284(10):1256–62. 10.1001/jama.284.10.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrykowski MA, Schmidt JE, Salsman JM, Beacham AO, Jacobsen PB. Use of a case definition approach to identify cancer-related fatigue in women undergoing adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6613–22. 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azim HA, Elghazawy H, Ghazy RM, Abdelaziz AH, Abdelsalam M, Elzorkany A, Kassem L. Clinicopathologic features of breast cancer in Egypt-contemporary profile and future needs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JCO Glob Oncol. 2023;9: e2200387. 10.1200/GO.22.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beesley VL, Price MA, Butow PN, Green AC, Olsen CM, Webb PM. Physical activity in women with ovarian cancer and its association with decreased distress and improved quality of life. Psycho-Oncol. 2011;20(11):1161–9. 10.1002/pon.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell-Enns H, Woodgate R. The psychosocial experiences of women with breast cancer across the lifespan: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(1):112. 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caplette-Gingras A, Savard J. Depression in women with metastatic breast cancer: a review of the literature. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6(4):377–87. 10.1017/S1478951508000606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cella DF. Methods and problems in measuring quality of life. Supportive Care Cancer: Official J Multinational Association Supportive Care Cancer. 1995;3(1):11–22. 10.1007/BF00343916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, You H, Liu Y, Kong Q, Lei A, Guo X. Association between spiritual well-being, quality of life, anxiety and depression in patients with gynaecological cancer in China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(1):e24264. 10.1097/MD.0000000000024264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho O-H, Hwang K-H. Association between sleep quality, anxiety and depression among Korean breast cancer survivors. Nurs Open. 2021;8(3):1030–7. 10.1002/nop2.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clemmens DA, Knafl K, Lev EL, McCorkle R. Cervical cancer: patterns of long-term survival. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(6):897–903. 10.1188/08.ONF.897-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson JR, MacLean AW, Brundage MD, Schulze K. Sleep disturbance in cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(9):1309–21. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devi S. Projected global rise in breast cancer incidence and mortality by 2050. Lancet Oncol. 2025. 10.1016/S1470-2045(25)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Sayed AA, Sorour AS, Aboel-Seoud AR, Sarhan AM. Supportive care needs in relation to psychological distress level among women under treatment for breast Cancer = احتياجات الرعاية الداعمة و علاقتها بمستوى الضغط النفسي لدى السيدات تحت العلاج بسرطان الثدي. Zagazig Nurs J. 2015;395(3592):1–15. 10.12816/0029177. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmawla DAEA, Ali SM. Psychological distress of elderly cancer patients: the role of social support and coping strategies. Int J Nurs Didactics. 2020;10(02):38–47 Article 02. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emre N, Yılmaz S. Sleep quality, mental health, and quality of life in women. Ind J Cancer. Retrieved March 9, 2025, from https://journals.lww.com/indianjcancer/fulltext/2024/61020/sleep_quality,_mental_health,_and_quality_of_life.14.aspx.

- 21.Endeshaw D, Biresaw H, Asefa T, Yesuf NN, Yohannes S. Sleep quality and associated factors among adult Cancer patients under treatment at oncology units in Amhara region, Ethiopia. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:1049–62. 10.2147/NSS.S356597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedrich M, Schulte T, Malburg M, Hinz A. Sleep quality in cancer patients: a common metric for several instruments measuring sleep quality. Qual Life Res. 2024;33(11):3081–91. 10.1007/s11136-024-03752-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganz PA, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Lash TL, Rakowski W, Silliman RA. Breast cancer in older women: quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in the 15 months after diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(21):4027–33. 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hajj A, Chamoun R, Salameh P, Khoury R, Hachem R, Sacre H, Chahine G, Kattan J, Khabbaz R. Fatigue in breast cancer patients on chemotherapy: a cross-sectional study exploring clinical, biological, and genetic factors. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):16. 10.1186/s12885-021-09072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassen AM, Taye G, Gizaw M, Hussien FM. Quality of life and associated factors among patients with breast cancer under chemotherapy at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222629. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He X, So WKW, Choi KC, Li L, Zhao W, Zhang M. Symptom cluster of fatigue, sleep disturbance and depression and its impact on quality of life among Chinese breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: A cross-sectional study. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:v840. 10.1093/annonc/mdz276.015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinz A, Mehnert A, Kocalevent R-D, Brähler E, Forkmann T, Singer S, Schulte T. Assessment of depression severity with the PHQ-9 in cancer patients and in the general population. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:22. 10.1186/s12888-016-0728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H-P, Chen M-L, Liang J, Miaskowski C. Changes in and predictors of severity of fatigue in women with breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(4):582–92. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingrassia M, Mazza F, Totaro P, Benedetto L. Perceived well-being and quality of life in people with typical and atypical development: the role of sports practice. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2020;5(1): 12. 10.3390/jfmk5010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.İzci F, İlgün AS, Fındıklı E, Özmen V. Psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial problems in patients with breast Cancer. J Breast Health. 2016;12(3):94–101. 10.5152/tjbh.2016.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jim HSL, Small B, Faul LA, Franzen J, Apte S, Jacobsen PB. Fatigue, depression, sleep, and activity during chemotherapy: daily and intraday variation and relationships among symptom changes. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(3):321–33. 10.1007/s12160-011-9294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapoor R, Dey T, Khosla D, Laroiya I. A prospective study to assess the quality of life (QOL) in breast cancer patients and factors affecting quality of life. Innovative Pract Breast Health. 2024;2:100004. 10.1016/j.ibreh.2024.100004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J, Harper A, McCormack V, Sung H, Houssami N, Morgan E, Mutebi M, Garvey G, Soerjomataram I, Fidler-Benaoudia MM. Global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat Med. 2025;31(4):1154–62. 10.1038/s41591-025-03502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langeh U, Kumar V, Ahuja P, Singh C, Singh A. An update on breast cancer chemotherapy-associated toxicity and their management approaches. Health Sci Rev. 2023;9:100119. 10.1016/j.hsr.2023.100119. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu L, Rissling M, Natarajan L, Fiorentino L, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE, Sadler GR, Parker BA, Ancoli-Israel S. The longitudinal relationship between fatigue and sleep in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Sleep. 2012;35(2):237–45. 10.5665/sleep.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L, Fiorentino L, Rissling M, Natarajan L, Parker BA, Dimsdale JE, Mills PJ, Sadler GR, Ancoli-Israel S. Decreased health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer is associated with poor sleep. Behav Sleep Med. 2013;11(3):189–206. 10.1080/15402002.2012.660589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Croft JB, Xu F, Cunningham TJ, Greenlund KJ. Relationship between sleep duration and self-reported health-related quality of life among US adults with or without major chronic diseases, 2014. Sleep Health. 2018;4(3):265–72. 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maass SWMC, Boerman LM, Verhaak PFM, Du J, de Bock GH, Berendsen AJ. Long-term psychological distress in breast cancer survivors and their matched controls: a cross-sectional study. Maturitas. 2019;130:6–12. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medeiros M, Oshima CTF, Forones NM. Depression and anxiety in colorectal cancer patients. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41(3):179–84. 10.1007/s12029-010-9132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michel G, François C, Harju E, Dehler S, Roser K. The long-term impact of cancer: evaluating psychological distress in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in Switzerland. Psycho-Oncol. 2019;28(3):577–85. 10.1002/pon.4981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molwus J, Erdogan B, Ogunlana S. Sample size and model fit indices for structural equation modelling (SEM): the case of construction management research. 2013:347. 10.1061/9780784413135.032.

- 43.Okuyama T, Akechi T, Kugaya A, Okamura H, Shima Y, Maruguchi M, Hosaka T, Uchitomi Y. Development and validation of the cancer fatigue scale: a brief, three-dimensional, self-rating scale for assessment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(1):5–14. 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, Roth T, Savard J, Ancoli-Israel S, Heckler C, Purnell JQ, Janelsins MC, Morrow GR. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: university of Rochester Cancer Center-community clinical oncology program. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):292–8. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perry S, Kowalski TL, Chang C-H. Quality of life assessment in women with breast cancer: benefits, acceptability and utilization. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):24. 10.1186/1477-7525-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reich M, Lesur A, Perdrizet-Chevallier C. Depression, quality of life and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110(1):9–17. 10.1007/s10549-007-9706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Morrow PK, Shete S, Hassan S. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Womens Health. 2012;21(3):311–8. 10.1089/jwh.2011.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sayed SM, El- Sherief MA, Mahfouz EM, Hassan EE, Elsaeed AM, Abdelrehim MG. Screening for psychological distress and affective state among Cancer patients in minia. Minia J Med Res. 2023;34(4):83–92. 10.21608/mjmr.2023.236356.1517. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Steindorf K. Quality of life, problems, and needs of disease-free breast cancer survivors 5 years after diagnosis. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(8):2077–86. 10.1007/s11136-018-1866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, Serdar MA. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2021;31(1):27–53. 10.11613/BM.2021.010502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tao L, Lv J, Zhong T, Zeng X, Han M, Fu L, Chen H. Effects of sleep disturbance, cancer-related fatigue, and psychological distress on breast cancer patients’ quality of life: a prospective longitudinal observational study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):8632. 10.1038/s41598-024-59214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tödt K, Engström M, Ekström M, Efverman A. Fatigue during cancer-related radiotherapy and associations with activities, work ability and quality of life: paying attention to subgroups more likely to experience fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022;21:15347354221138576. 10.1177/15347354221138576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webber K, Carolus E, Mileshkin L, Sommeijer D, McAlpine J, Bladgen S, Coleman RL, Herzog TJ, Sehouli J, Nasser S, Inci G, Friedlander M. Ovquest– life after the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer—an international survey of symptoms and concerns in ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;155(1):126–34. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weitzner MA, Meyers CA, Stuebing KK, Saleeba AK. Relationship between quality of life and mood in long-term survivors of breast cancer treated with mastectomy. Supportive Care Cancer: Official J Multinational Association Supportive Care Cancer. 1997;5(3):241–8. 10.1007/s005200050067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkinson L, Gathani T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1130): 20211033. 10.1259/bjr.20211033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu J, Li Q, Gao Z, Ji P, Ji Q, Song M, Chen Y, Sun H, Wang X, Zhang L, Guo L. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on quality of life in patients with cancer: multiple mediating roles of psychological coherence and stigma. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1):64. 10.1186/s12885-025-13468-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yfantis A, Sarafis P, Moisoglou I, Tolia M, Intas G, Tiniakou I, Zografos K, Zografos G, Constantinou M, Nikolentzos A, Kontos M. How breast cancer treatments affect the quality of life of women with non-metastatic breast cancer one year after surgical treatment: a cross-sectional study in Greece. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):210. 10.1186/s12893-020-00871-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yusuf İlhan OY. B. Sleep quality and quality of life in breast Cancer patients: comparative study with a healthy control group. Turkish J Sleep Med. 10.4274/jtsm.galenos.2023.83007.

- 59.Zhu W, Gao J, Guo J, Wang L, Li W. Anxiety, depression, and sleep quality among breast cancer patients in North China: mediating roles of hope and medical social support. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(9):514. 10.1007/s00520-023-07972-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available within the manuscript.