Abstract

Background

Several support strategies to support international medical graduates’ transitions in host countries have been published. This review aims to map available strategies and identify gaps for future research.

Methods

A scoping review was performed using the PRISMA-ScR checklist and The Arksey and O’Malley framework. The electronic databases of Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and Education Resources Information Center were systematically searched for relevant studies. This was supplemented by citation exploration, direct reference lists and grey literature searches. Original peer-reviewed publications on existing strategies to support IMGs in the English language between 2010 to June 2023 were included. Study characteristics and themes were analyzed iteratively.

Results

Twenty-nine case reports and one residency training handbook for IMGs had educational support strategies focusing on communication, clinical skills workshops, orientation/induction programs, clinical attachments and observership programs. Eight articles reported social support strategies, including pastoral and administrative support, online social networks for information sharing, and buddying relationships between IMGs, family, friends and peer support groups. Most of the publications were from Australia and United Kingdom.

Conclusion

The review highlighted educational and social support strategies to facilitate the transition of International Medical Graduates in their host countries. Interventions tailored to their individual needs, continuous assessment, and ongoing support tend to be successful. It emphasized the role of social support, improved induction programs and use of internet-based interventions to facilitate IMGs transition in host countries. Further research may evaluate the effectiveness of proposed strategies and establish standardized evaluation criteria.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07389-z.

Keywords: Support strategies, International medical graduates, Health worker immigration

Introduction

International medical graduates (IMGs) are medical graduates who obtained their medical degrees in a country other than their current place of practice [1]. Physicians from low- and middle-income countries may choose to relocate to high-income countries, such as the United States of America (USA), United Kingdom (UK), Australia, or Canada, for better training opportunities and career progression, political, economic, and personal reasons [2–4]. Evidence shows that developed countries depend increasingly on foreign-trained health professionals for essential medical services [5–7]. In their host countries, IMGs encounter difficulties engaging with new systems programs and cultures [8–10]. A recent scoping review on inequitable treatment as perceived by IMGs outlined key challenges, notably marginalization through subtle exclusions, stereotypes and stigmatization [7].

Providing adequate support is crucial to IMGs performing creditably within efficient clinical governance systems [11]. Various strategies to support IMGs’ transition have been reported [6, 12, 13]. Research is needed to examine these strategies to determine their effectiveness, the expedient time to deploy them and ways to improve them.

Reviews on IMGs transition in host countries focused on challenges [14, 15]. and qualification programs [16]. The authors identified language and communication, clinical, educational and work culture, and discrimination challenges as part of the difficulties that immigrant doctors may experience. An in-depth evaluation of these challenges and providing tailored support are appropriate steps in guiding IMGs to make a smooth transition. Kehoe and co-workers published a realist synthesis on supporting IMGs’ transition to their host countries, looking at factors related to the individuals, training, and organizations [17]. To the best of the author’s knowledge, no scoping review has focused on strategies to support IMGs’ transition in their host countries. It is important to map all available information on this topic and identify areas that require further research or improvement in the quality of existing research. A scoping review is the most suitable way to accomplish this goal and is the present study’s focus.

Objectives/research questions

A scoping review was conducted to carefully map available information on the topic, identify gaps and propose future research. Using the patient/population, intervention, comparison and outcomes (PICO) model, the review focused on international medical graduates involved in a training program or engaged in clinical practice. The United Kingdom (England, Scotland and Northern Ireland), Canada, Australia and the United States of America have been identified as choice destinations for migrating international medical graduates [18], and were therefore chosen. The words interventions, strategies or programs will be used interchangeably to describe the support structures. The following research questions were formulated:

What strategies are available to support international medical graduates’ adaptation to their host countries?

What are the outcomes associated with these strategies?

What improvements can be made to make the strategies more effective?

The review has the following objectives goals:

To identify strategies available to support international medical graduates in their host countries, including educational programs, administrative guidelines or policies, and social, cultural and financial support.

To summarize the outcome in terms of sustained improvement in knowledge and/or skills and the generalizability of the intervention.

To present suggested action plans for more effective support strategies and highlight areas for future research.

Methodology

A scoping review was conducted to determine the available literature and guide further research on the strategies for supporting international medical graduates in their host countries from January 2000 to June 2023. As described by (Arksey & O’Malley), scoping reviews examine the extent, breadth, and characteristics of research, assess research activity, summarize, and disseminate information, and identify gaps to determine the need for further research. This review was conducted in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [19], and The Arksey and O’Malley framework for Scoping Reviews [20].

Identification of relevant studies

Search terms were identified using the PICO framework. The population terms were identified as international medical graduate or foreign medical graduate or transnational medical graduate or overseas medical graduate; intervention and/or outcome terms were defined as interventions or strategies or induction or financial or academic or social or cultural. A pilot search (Search 2) was conducted with these search terms in the Medline electronic database on 10/7/2023. Given that this was a scoping review with no comparative groups, the term comparison in the PICO framework was replaced with context for the purpose of this review. In this case, context delineates the geographical scope where migration of medical graduates gravitates towards, and was identified as the United Kingdom, England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, and the United States of America [21]. The outcome was the specific type of documented support provided. A title and abstract search was conducted with the selected host countries. (Search 4) Boolean operators AND/OR were used to narrow or expand the search as necessary. A combined search (search 5) with searches 2 and 4 was then performed. This helped refine the search by limiting recovered articles to those from the selected host countries. A similar search was performed in the electronic databases of Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Scopus, and Web of Science on 27/7/2023, ensuring necessary adaptations to each database. The entire search was supervised and directed by a vastly experienced Medical Librarian, who assisted with search term design. (supplemental file – Appendix 1) Citation exploration was performed initially in Web of Science database on 27/7/2023 and 28/7/2023. Further exploration and harvesting of reference list from relevant articles continued by direct searches until 7/9/2023. As a quality measure of the search strategy, the search was tested against the search instruments and major publications on the subject. The Medline electronic database was searched iteratively, and the last search was conducted on 8/8/2023. The searches were continued at intervals till the last date to ensure that newly published manuscripts within the study period were not omitted in the review. A screenshot of the final Medline search can be found in the supplemental file – Appendix 2. Grey literaturesearch comprised of thesis/dissertation or conference proceedings as well as residency training programs guidelines for IMGs, was also searched for contributing articles or information.

The review includes sources of evidence focusing on strategies, interventions, or programs available to support international medical graduates’ transition in host countries. To cover all publications focusing on available rather than proposed or suggested support strategies, the start date of January 2010 was chosen [17]. The present study sought to identify the outcome of possible changes based on the recommendations noted in earlier publications and observe any identifiable pattern. The references were exported to EndNote Referencing Management Software.

Study selection

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied during the first screening of titles and abstracts (Table 1). Using the EndNote Referencing Management Software, duplicate references from the electronic databases were found and removed. A full text of publications and articles from citation exploration, reference harvesting, and grey literature searches were conducted. Articles that did not conform to the eligibility criteria were excluded. Articles that could not be retrieved were sought from the University of Swansea IFind and Library Documents Supply Unit. Retrieved articles underwent secondary screening in conformity with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles that described any form of support strategy or intervention and those that documented the experience of support narrated by IMGs were included, irrespective of whether the outcome was evaluated or not. This was considered appropriate given that scoping reviews emphasize the breadth rather than the depth of published studies [20]. Articles whose focus was on other international health professionals, not limited to medical graduates, or global health not focused on IMGs or medical graduates but not international or foreign or overseas medical graduates were excluded from the review. All types of study designs; qualitative, quantitative, mixed, commentaries, or reports were included (if they sufficiently described a support strategy) except review articles. Articles not written in the English language were excluded to avoid interpretation errors. Where doubts existed regarding the suitability of an article, a consensus was reached by EPN, DCO and OEO. The outcomes of interventions described in the studies were measured using Kirkpatrick’s framework model [22]. with a slight modification based on the research objectives.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Study focus is on International medical graduates; Study focus is on international health professionals, but IMGs are the majority |

Study focus is on other international health professionals, not limited to medical graduates. Article is on global health not focused on IMGs. International medical students Medical graduates but not international or foreign or overseas medical graduates |

| Intervention | Study focus is on existing support or discusses existing support | Study focus is on suggestions or proposals for necessary support; Study does not clearly and sufficiently describe the intervention or existing support |

| Location | Study subject is based within the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and the United States of America | Study subject is based outside of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and the United States of America |

| Date | Study is published between January 2010 and June 2023 | Study is published before January 2010 or later than June 2023 |

| Language | Study is English | Study is not in English |

| Study design | Study involves primary data, commentary, or reports | Study consists of secondary data (all forms of reviews: systemic, scoping, realist synthesis, rapid review) |

| Peer reviewed | Study is peer-reviewed | Study is not peer-reviewed |

| Full-text availability | Full text is available | Full text is not available |

Results

Charting of data

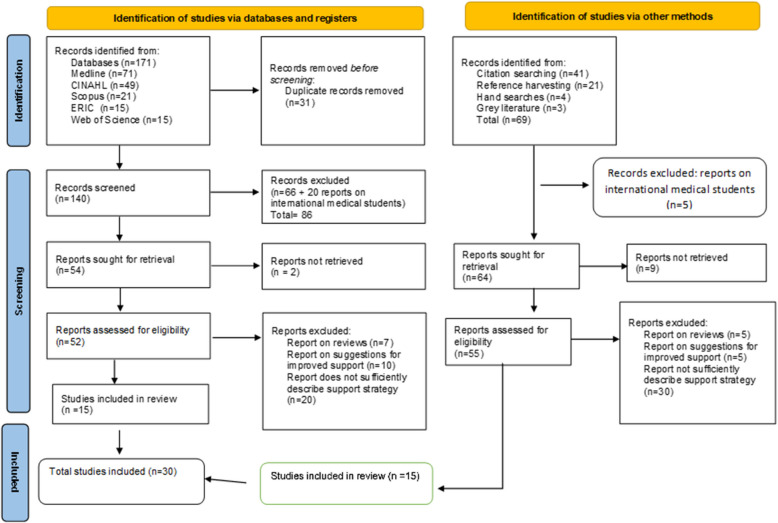

A total of 171 articles were obtained from the electronic databases searched, and 69 articles from citation exploration, reference harvesting, direct and grey literature searches. Thirty-one duplicate articles and 66 others that did not pass the second scrutiny of the Titles and Abstracts were removed. The full texts of 119 articles (54 from electronic databases and 65 from citation exploration, reference harvesting, and direct and grey literature searches) were sought and yielded all but 11 articles. The secondary (full text) screening excluded 50 articles that did not sufficiently describe the support strategy, 12 articles that were review papers, and 15 articles that described proposed or suggested support strategies. Ultimately, 31 articles and one residency training program handbook for IMGs were selected for inclusion in the review. A PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process of the sources of evidence is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of sources of evidence

All included articles were read several times, and relevant data was extracted into an Excel spreadsheet. Data did not follow any rigid framework but was constantly updated iteratively. The study characteristics included the references with dates of publication, methodology host country involved, type of strategy described, a summary of the details of the support strategy or intervention provided, the participants who benefited from the support, number of participants, duration of the intervention and the reported outcome or main effects of the intervention. Where available, information about prior needs assessment and funding availability for the study were equally extracted.

The strength of methodological evidence was not appraised as this was not the goal but to map all the available evidence and identify gaps to inform further research. The suggestions for more effective support for this group of doctors were highlighted.

Collating, summarizing and reporting of results

The general characteristics of all included sources of evidence are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of sources of evidence

| Ref | Host country | Study method | Type of strategy | Summary of support strategy | Participants | Number of participants | Outcome/Main finding | Duration | Prior needs assessment | Funding available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Strategy | ||||||||||

| [23] | USA | Case study | Educational | Web-based workshop on the US health care system, including delivery and payment methods. Special focus on Family Medicine and professional bodies like the AAFP, the AMA. Several SCORM-compliant modules with interspersed quizzes. | International Family Medicine Residents | Variable | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| [24] | Canada | Case study | Educational | Medical communication and assessment project, MCA-P using didactic lectures and supervised clinical placements. Aimed at improving medical communication, clinical skills and professionalism. | IMGs | 274 | Participants and Preceptors reported improved proficiency in language skills and performance on OSCE data | 16 weeks | No | Not stated |

| [25] | UK | Case study | Educational | Communication skills course delivered through presentations, workshops and clinical practice with simulated patients, involving linguists and healthcare professionals. The focus was to improve verbal communication using feedback from language, cultural and clinical perspectives | IMGs | 20 | Improvement in language and communication skills | 3 days | Yes | Yes |

| [26] | Australia | Case study | Educational | Multi-level evaluation strategy to map participants’ baseline and ongoing learning needs and application of learning to the workplace using a modified Kirkpatrick’s model to assess the GIPSIE program | IMGs | 17 | Ongoing learning needs identified. Transfer of learning to workplace confirmed at intermediate evaluation. | >2 months | Yes | Not stated |

| [27] | Australia | Case study | Educational | English language and communication skills training aimed at improving performance at oral examinations | International Physician Trainees | 13 | Improvement in verbal (pronunciation) and nonverbal communication skills | 12 weeks | Not stated | Not stated |

| [13] | Australia | Case study | Educational | The CaLF tool—A communication and Language Feedback tool involving linguists, discourse analysts and medical educators. Feedback is given on both communication skills and language proficiency | IMGs | 5–14 | 80% of participants passed their examination; the CaLF tool is employed in interdisciplinary training of IMGs | 2 hours/weekly x 10 sessions | Yes | Yes |

| [28] | Australia | Case study | Educational | An interdisciplinary clinical and ethical communication training using multimedia | IMGs | Not stated | Participants found the learning experience helpful | Not stated | No | Not stated |

| [29] | UK | Case study | Educational | Communication and consultation skills workshop using Role-plays and experienced GP feedback | IMGs | 13 | Success in examination as well as improvement in clinical practice | 3 workshops duration not stated | No | Yes |

| [30] | Australia | Mixed | Educational | The GIPSIE Program: A Web-based workshop involving simulated patient consultations, examination skills training and management of deteriorating and acutely ill patients training with multisource feedback. | IMGs | 17 | Improvement in participants’ clinical skills | 63 days | Yes | Yes |

| [31] | Australia | Qualitative | Educational | Bridging courses and study groups. Also, the process that allows taking the first part of the licensing examinations in the home country | IMGs | Not stated | IMGs attest to their usefulness | Not stated | No stated | Not stated |

| [32] | UK | Case study | Educational | Language and communication skills training offered to volunteers, aimed to develop patient-centered consultations, and foster a culture where IMGs can discuss their difficulties openly. | IMGs | 14 | Participants showed statistically significant improvement in 2 out of four areas of communication skills | 6 months/15 sessions | Yes | Yes |

| [33] | USA | Case study | Educational | Program of clinical Observerships in Psychiatry to improve clinical and communication skills and familiarize IMGs with US medical system with inclusion of didactics. Also provides a pre-Residency position | International Psychiatry trainees | Not stated | Not stated | 6 months/Variable | Not applicable | Yes |

| [34] | Canada | Case study | Educational | TLC Program—Teaching for Learning and Collaboration: A clinical skills development program. Encouraged negative feedback | International Fellows in Psychiatry | 4 | The program was found useful and applicable to other IMGs’ training. Negative feedback highlighted learning needs better | >3 months | Yes | Not stated |

| [35] | Australia | Case study | Educational | A clinical skills training using structured reflection model as a method of learning and active reflection in clinical practice in informal settings | IMGs |

3–23 Average of 9/session |

Participants’ better appreciation of the roles of the multidisciplinary team facilitated their adaptation and improved their practice | I hour bi-weekly x 6 sessions | Yes | Yes |

| [36] | Australia | Case study | Educational | Face-face and videoconferencing guided tutorials for Specialist Anesthesiologists, aimed to improve performance at examinations | International Anesthesiologist Specialists | 166 | Pass rates at the College examinations improved with attendance at the tutorials | 2 weeks | No | Yes |

| [37] | UK | Case study | Educational | Clinical attachment with a structured timetable and clearly defined clinical and educational supervision; Peer mentoring and learning experiences tailored to individuals. Aimed at improving clinical communication skills and proficiency in desired clinical procedures | IMGs | Not stated | Not stated | Variable 2 weeks – 6 months | Not stated | Not stated |

| [38] | UK | Case study | Educational | Short videos-vignettes used to demonstrate differences in doctor-and-patient-centered consultations; diversity workshop to explore cultural diversity encouraging ‘respectful curiosity’ and follow-up consultation training with role-play. | IMG GP Trainees | 6 | The course was successful and has been adopted for all incoming IMG GP Trainees | 1.5 days | Yes | Not stated |

| [6] | UK | Qualitative | Educational | Induction described as “a very objective view of acculturation | Non-UK trained European Economic Area (EEA) Anesthesiologists | 8 | Participants didn’t find the program helpful. | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| [39] | Australia | Case study | Educational | A standalone digital resource—Doctors Speak Up: Communication and Language Skills for IMGs utilizing culturally- sensitive topics for clinical content, and the CaLF tool. | IMGs | 48 | Participants found the Resource useful and increasingly more doctors use it | Not stated | Yes | Yes |

| [40] | Canada | Case study | Educational | Orientation of IMGs on specialist Psychiatry training using a curriculum derived from Kern’s framework of curriculum development. | IMG Psychiatry Trainees | 19 | Participants felt more ‘comfortable’ managing social isolation and felt they transitioned better | 1 day | Yes | Not stated |

| [41] | USA | Case study | Educational | Acculturation Toolkit—Small group workshops on patient-centered consultations, communication skills in handling challenging clinical situations, using didactics, case-discussions and role-plays. | IMG Pediatric Trainees | 36 | Workshop improved participants’ knowledge and communication skills and eased their transition to Residency | 6 months | Yes | No |

| [42] | Uk | Case study | Educational | Two pilot high-fidelity simulation courses focused on team dynamics and frequently encountered clinical scenarios. Training is followed by debriefing sessions that focus on human factors, communication skills, and authority dynamics. | All IMGs | 22 | Statistically significant improvement in all accessed domains: Basic management, clinical and communication skills; teamwork and leadership. | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| [43] | Canada |

IMG Program |

Educational |

1) Externship Orientation 2) Clinical Externship Assessment Period |

IMGs | Not stated | Not stated | 6–10 weeks | Not stated | Not stated |

| Administrative Strategy | ||||||||||

| [44] | Australia | Qualitative | Administrative | Accommodation and Transportation support from hospitals and recruiting agencies | IMGs | Not stated | IMGs found this helpful | Not stated | Yes | Not stated |

| Combined Strategies | ||||||||||

| [45] | UK | Case study | Educational and Pastoral | Induction consisting of interactive presentations and workshops on the NHS, multi-professional staff, referral procedures and patient pathways. Also role-play based training on challenging communication tasks and conflict resolution. Pastoral support in the form of professional advice, guidance on visas and accommodation, counselling, and provision of Peer-support | OTDs | 12 | Participants found the learning experience helpful | 1 day and Ongoing | Not stated | Not stated |

| [46] | UK | Qualitative | Educational and administrative | Induction. Training posts. Protection by managers and administrators. | Non-UK-qualified doctors | Not stated | Affected individuals valued the program and felt safe | Not stated | No | Yes |

| [47] | USA | Case study | Educational and Employment | Welcome Back Initiative –A Web-based participant-centered program that offers IMGs opportunities for educational support and provides training for re-credentialling, licensure and employment in healthcare as well as in alternative careers | IMGs | 10,700 | About a quarter of participants passed their licensing examinations or gained employment. More than three-quarters were connected to a Residency program | Variable | Yes | Not stated |

| [1] | UK | Case study | Education and Social | Program for Overseas Doctors—POD comprising multiple individualized modules spanning patient-centered consultation and communication skills, intercultural training and clinical consultation skills for challenging situations. Social support networks and guidance on career progression. Buddying and ongoing supervision | Oversea-trained doctors | Not stated | Not stated | 1 year | Yes | Yes |

| [48] | UK | Mixed | Educational and Social | Support from educational and clinical supervisors and Program Directors to gain knowledge in Reflection in clinical practice. Also, Peer and Family support | IMG GP Trainees | 485 | Participants felt that it was helpful | Not stated | Not stated | Yes |

| [49] | UK | Case study | Educational and Social | Peer-led support comprising induction programs, on-going support via an instant-messaging platform, a webinar on training portfolios and follow-up induction questions and answers. | IMG Internal Medicine Trainees | Not stated | Participants reported less difficulty with training and adaptation | 6 months | Yes | Not stated |

| [50] | UK | Case study | Educational and Social | Early near-peer one-to-one linguistic coaching to identify those who need more and offer tailored help. Support with accommodation and transportation. | IMG GP Trainees | 12 | All participants found the training useful and felt that the informal approach helped them to learn and integrate better | 1 day | No | No |

| [8] | Canada | Mixed | Sociocultural | Social media networks between groups of IMGs provide information on training, schools for children, transportation and accommodation; Multicultural training environment facilitate cultural adaptation | IMG Residents in Surgery and Psychiatry | 70 | Participants found the learning experience helpful | Unclear | Yes | Not stated |

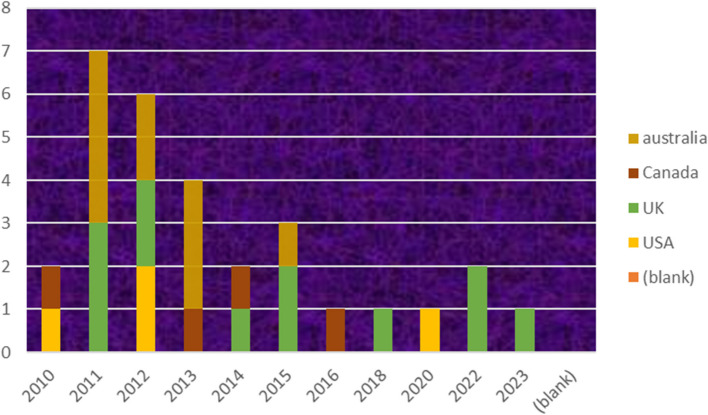

Publications timeline by host countries

Most of the studies were conducted in Australia (9/21, 42.9%) before 2015, but there appears to have been a decline thereafter, with the UK reporting the majority (7/10, 70%) of studies from 2015 to 2023. Figure 2 shows a graphic representation of the timeline.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of publications

Characteristics of the sources of evidence

Most reports were case studies (24/31, 77.4%); 4/31 (12.9%) used qualitative methods (interviews and focus groups), and 3/31 (9.7%) used a mixed qualitative and quantitative methodology in their report. All reported educational interventions except for two publications: one focused on mainly administrative policies [44]. and the other on social support [8]. Six articles, in addition to educational interventions, reported other forms of support strategies such as pastoral [45], employment [47], and social [1, 48, 49].

Types of support strategies

The strategies have been grouped into educational and social strategies for the purpose of a comprehensive review.

Educational strategies

Educational interventions comprised inductions, orientation exercises, workshops, clinical attachments and clinical observership programs. Twenty-eight of 31 (90.3%) focused on these strategies. Seven (25.0 %) of these also reported other forms of intervention.

Inductions, orientations and workshops

Five induction sessions and one orientation program were held in the UK. The sessions included interactive presentations and workshops on the NHS, multi-professional teamwork, patient pathways and referrals, management, and clinical training. Workshops were centered on language and communication skills training, patient-centered consultations, intercultural training, clinical consultation skills for challenging situations, and training to acquire proficiency in clinical procedures. They were typically organized by employers, program directors, or educational supervisors and had variable duration.

The Program for Oversea-trained Doctors (POD) [1] - This was a one-year-long program comprised of several modules that covered patient-centered consultation skills, language and cultural training, and consultation techniques for challenging clinical settings. It also provided social support, career guidance, and ongoing support through buddying relationships. However, it was not clear how many people participated in the program.

The Acculturation Toolkit [41] – This was developed for small groups of IMG Pediatric trainees and offered additional training using didactics, case discussions and role-plays. It lasted for six months with 36 participants.

A structured reflection model (Australia) - Used in clinical skills training for small groups of IMGs in informal settings. It lasted one hour and was bi-weekly for six sessions [35].

The clinical skill workshop (UK) - Involving 13 participants enhanced by incorporating role-plays and receiving feedback from an experienced General Practitioner [29]. To enhance verbal communication for 20 IMGs, the workshops utilized feedback from language, cultural, and clinical perspectives, and involved simulated patients, linguists, and healthcare professionals [25].

The CaLF tool [13] This Communication and Language Feedback tool involves linguists, discourse analysts, and medical educators. who offered feedback on language performance and clinical communication skills. Multimedia facilitated interdisciplinary clinical and ethical communication training for IMGs in Australia with 5–14 participants [28]. A workshop on the English language is tailored to prepare IMG physician trainees for oral examinations [27].

The Medical Communication and Assessment Project MCA-P [24]. Is a 6-week-long clinical communication skills program that targets all IMGs in Canada. It is delivered via didactics and clinical attachments.

Bridging courses and study groups among IMGs were helpful resources geared towards passing examinations [31].

A structured clinical observership program that included didactics, and a pre-residency position was described for International Psychiatry trainees in the USA [33].

Broderick and Zoppi [23] described web-based training focusing on host countries’ health policies and organizations and specialty-specific information in the USA. The program uses Sharable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM) compliant modules with interspersed quizzes to facilitate learning in language and clinical communication skills. Participation was variable.

The Gippsland Inspiring Professional Standards among International Experts (GIPSIE) program [30] aimed to improve clinical communication skills for 17 participants, by using simulated patients to hone skills in managing deteriorating and acutely ill patients with multisource feedback.

The Welcome Back Initiative (WBI) is a web-based workshop that offers language and communication skills training. It also helps (IMGs) in the USA update their credentials, obtain necessary licenses, and secure employment, including alternate employment [48]. It provided for all health professionals (10,700), but international medical graduates accounted for 65% of attendees.

Doctors Speak Up is a Standalone Digital Resource that uses culturally sensitive topics and the CaLF tool to provide language and communication skills training in Australia [39], with 48 participants.

Videos were used to augment tutorials for examination preparation via videoconferencing with 160 participants [36] and to enhance skills transfer in patient-centred consultation skills and cultural sensitivity training using short video vignettes with 6 participants [38].

In the UK, new General Practitioners receive virtual one-to-one coaching on English language communication skills within 2 weeks of starting their training. The sessions, which last 45 minutes to 1 hour, utilize ‘what we say versus what we mean’ exploration slides. Next were standardized consultations with the coach as the patient and had 12 participants [50].

Two pilot high-fidelity simulation courses for all International Medical Graduates (IMGs) that featured common clinical scenarios, focusing on human factors, communication skills, and authority gradients. There were 22 participants who showed significant improvement in confidence levels in all domains assessed [42].

- Alberta International Medical Graduate (AIMG) Externship Program [43] – Provides educational support and assessment for IMGs with guidelines released in a yearly six- or ten- week externship activity handbook. This consists of two mandatory components:

- Externship Orientation - pre-recorded sessions, modules, slideshows, and other informative material available on the AIMG Program Externship website and the SharePoint platform with set deadlines. The second part of the orientation is a 2-week series of live virtual sessions.

- Clinical Externship Assessment Period - Following the orientation sessions, externs participate in a four- or eight-week assessment period in clinical settings determined by the applicable residency program.

The roles of the AIMG Program are to coordinate externship, arrange for a current resident who graduated from the program to mentor an extern, be a resource and monitor the progress of the extern. Ultimately, the Residency Program Director (or appointed representatives) determines at their discretion if the extern will be accepted into residency training at the PGY1 level at the completion of the clinical assessment.

Social strategies

Social strategies comprised social networks, peer support, buddying relationships, family and friends, counseling, provision of information on social amenities like schools for children, employment, and pastoral and administrative interventions. Two (6.7%) articles focused solely on social interventions [8, 44].

Peer-led programs, including webinars on training portfolios and instant messaging platforms that provide ongoing support for six months, are available for IMGs trainees in internal medicine in the UK [49].

Buddying relationships with senior IMGs and Supervisors allowed for ongoing support and supervision [1].

Family and friends were reported to offer the best support and advice to IMGs on reflection in clinical practice [48].

The POD provides a platform for building social support networks and guidance on career progression [1].

The establishment of social media networks like Facebook and e-mail exchanges between groups of IMGs provided information on training, schools for children, transportation, and accommodation. The multicultural setting for IMG trainees in surgery and psychiatry in Canada enhanced cultural adaptation [8].

-

Pastoral/Administrative strategies

Administrative support was reported as assistance with accommodation and transportation concerns provided by hospitals and recruiting agencies for IMGs [44]. Protective support from managers and administrators provided some feeling of security from abuse. The absence of such support ‘led to a situation where many of these doctors felt marginalized and at risk, and there may be complaints of bullying [46, 50].

-

Employment

The Welcome Back Initiative was the only program reported to assist with re-credentialing and employment for IMGs [47].

The duration of the intervention depends on the program. More than half (18, 60%) of the interventions were instituted following a prior need assessment and tailored to the identified needs. Half of the publications provided no information on funding availability.

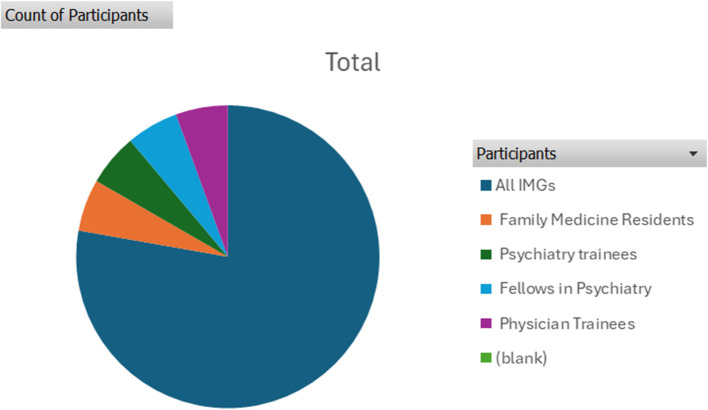

Interventions according to various IMG groups

Small group workshops were often but not always tailored to various specialties in medicine, and large group workshops were offered to all IMGs regardless of specialty (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Interventions according to IMG groups

Outcome of interventions

The interventions’ evaluation did not adhere to a uniform framework. The outcome was accessed based on the modified Kirkpatrick model [22]. Immediate assessment of participants’ reaction post-workshop, ongoing assessment to ascertain the transfer of learning and skills to the workplace, the generalizability of the intervention and availability of empirical evidence for outcome judgment were considered. The studies are grouped from level 1 to level 4B in ascending order (Table 3).

Table 3.

Modified Kirkpatrick’s Model for Evaluation

| Level | Description | Reference number of studies |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reaction to the tutorial by participants and resource persons. No reliability or validity evidence | [8, 28, 38, 45, 48, 50], |

| 2 | Changes in the attitudes or perceptions among participants demonstrated modification of knowledge or skill. No reliability or validity evidence | [24, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 35, 40, 47, 49] |

| 3 | Transfer of new knowledge and skills to the workplace. No reliability or validity evidence | [51] |

| 4A | Change in the system/organizational practice. Adoption of intervention for wider use. No reliability or validity evidence | [34, 39] |

| 4B | Improvement in student or resident learning/performance as a direct result of the educational intervention. Demonstration of reliability or validity evidence | [13, 36, 41, 42] |

Three publications and 1 training program handbook for IMGs did not provide outcome of the intervention or program [1, 23, 37, 43].

Discussion

This review has analyzed the existing literature on support strategies for international medical graduates (IMGs) in the UK, USA, Canada, and Australia over the past 13 years. Most of the published articles originated from the UK and the reason for this might be due to the growing numbers of IMGs working in the NHS [52]. Conversely, the seemly higher number of papers from the UK in this review may also be attributable to less relevance for publications in this area due to availability of a specified country defined IMG program resources and guideline as seen with the Canadian AIMG Program [43]. One of the pitfall of relying solely on information about support available to IMGs using the program guideline is the absence of the outcome or impact of the support program on the participants. On the other hand, it advantages include unification of program activities and harmonization of experiences irrespective of the host training centre.

Educational interventions, usually induction programs and training workshops on language and communication skills were reported by most studies, and were generally helpful, but not sustained long enough to ensure the transfer and retention of knowledge and skills [1]. Induction programs tailored to prior needs assessments or accompanied by continuous assessment and ongoing support with the involvement of senior IMGs appeared to be a more helpful strategy [1, 40, 41]. The disproportionate focus on educational interventions suggests an exaggerated emphasis on the process of learning and relearning for IMGs and is aimed at ensuring that they are properly equipped to deliver the highest quality of care to their host populations [5]. While this approach might be appropriate for early-career IMGs, it is important to create an environment for specialist IMGs, that encourages them to share their extensive knowledge and discuss perspectives that differ from local practices. Such knowledge sharing would be mutually beneficial [6]. Additionally, exploring the experiences of Specialist IMGs to discover what peculiar support they require [6]. Facilitating cultural exchange and learning from each other’s experience, representation at national bodies, advocacy and lobbying resonates with an earlier review [14].

Most of the programs’ evaluations lack a consistent framework, making effective comparisons and universal application difficult. An earlier review on educational interventions for International Medical Graduates (IMGs) reached similar conclusions, highlighting that the theory and evidence on this topic are still evolving [53]. The personalized clinical attachment model, which involves an early assignment of peer mentors and is designed to support personal development, has been recognized as an effective strategy. However, gaining admission to this program is unfortunately complicated [11, 37]. Removing the barriers to accessing clinical attachments would be beneficial. Training trainers, supervisors, and other trainees about the challenges encountered by IMGs will significantly influence positive changes and supportive attitudes [15, 26].

Social support strategies, though under-reported in this review, are vital for effective educational interventions. Evidence shows that early buddy relationships, peer mentoring, and social media networks help international medical graduates (IMGs) with social and financial adjustments, promoting successful workplace integration and better mental health [1, 8, 12, 49]. The establishment of a point, contact person or liaison officer as suggested would provide solid institutional support to deal with security and administrative issues and negotiate bureaucracies like health insurance, banking and other social amenities [15, 44]. A follow-up on its implementation was unavailable and could not be evaluated. Other suggested strategies without a report on implementation are listed in Table 4. Applying models like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Theory of Motivation adds depth to the support strategies, ensuring they are both practical and theoretically sound [8]. The lack of information on funding availability for the studies made it difficult to assess the sustainability and scalability of the support strategies reported.

Table 4.

Summary of suggested support strategies

| Ref | Host country | Type of support | Summary of support |

|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | Australia | Educational | Training on multidisciplinary teams of allied health collaboration in clinical practice |

| [55] | UK | Educational | Competency-based support after needs assessment; ‘buddy-system’ of support, more information on NHS and longer induction |

| [56] | Australia | Educational | Intensive supervision and more emphasis on language and communication training |

| [9] | Canada | Educational | Mentoring for IMGs; educational programs for faculty and non-IMGs on transition challenges of IMGs |

| [57] | America | Educational | A transitional curriculum; training on team dynamics, competency-based orientations |

| Combined | |||

| [12] | America | Sociocultural | Sociocultural support to maintain mental health and aid adaptation |

| [8] | Canada | Sociocultural | Improved access to formal IMGs’ specific support resources, such as online resources and specific fellowship contacts; Adaptation of Marlow’s hierarchy of needs to the provision of support to IMG Fellows |

| [58] | America | Financial and Immigration | Increased funding for graduate medical education; address immigration concerns like visa restrictions and inconsistencies |

| [44] | Australia | Educational and Social | Liaison officer for IMG |

| [59] | Australia | Educational, Financial and Social | Adequate information on the examinations; affordable training opportunities and counselling services |

| [60] | UK | Educational and Social | Clinical attachment (Shadowing); longer Orientation tailored to identified needs; education of non-IMGS; “Buddy-system” between new and senior IMGs; review of PLAB examinations to include more assessment on NHS values; counselling and information |

| [61] | America | Immigration and License | Address immigration concerns like visa restrictions and inconsistencies; Temporary Licensing Statute for Short-Term Clinical Training of FMGs |

| [26] | Australia, Canada and UK | Educational and Social | Learner-oriented and flexible training by adopting a Competency-based approach; targeted and longer training programs as necessary; longer and well-structured orientation; assessment at entry point and direct observation, early intervention for struggling IMGs; avoidance of prejudice, selection and admission bias against IMGs |

| [3] | UK | Immigration, Educational and Institutional | Address immigration concerns like visa restrictions and inconsistencies; improve institutional support structures; establish peer support and personal mentoring |

| [62] | UK | Social and Educational | Build supervisor-supervisee relationships; provide guidance on CV preparations and job application |

A Realist synthesis review emphasized the importance of organizational and program-level interventions to help International Medical Graduates (IMGs) adjust in their host countries [17]. Similar to the current review, it noted the need for personalized interventions and ongoing support from peers and supervisors. In contrast, this scoping review identified additional social and internet-enhanced support strategies and some improvements in the organization and duration of orientation programs not captured in the Realist synthesis.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first scoping review focused on available strategies to support IMGs in their host countries. It highlights a trend toward a combination of initial orientation programs, longitudinal assessment and ongoing support as well as IMG-specific interventions and the central role of social support in overall smooth transition. There are important gaps and areas for improvement in the quality and reporting of research on the topic. Further studies are necessary to determine whether the paucity of publications from the US is a lack of available support for IMG transition or from under-reporting, such as unpublished literature or handbooks.

Limitations include the fact that, being a scoping review, robust appraisal evidence was not undertaken. The restriction to peer-reviewed articles, the English language and the timeframe of publications may have excluded some publications. In addition, residency training programs that provide induction/orientation activities/workshops to IMGs across the world are not readily available online or are not in the published literature. The exclusion of secondary data may have limited the sources of evidence, however, the reference lists of review articles on the topic were searched to ensure relevant studies were not omitted.

Conclusion

This scoping review has identified several educational and social strategies to support international medical graduates’ transition in the US, Canada, Australia and the UK. The focus on IMG-specific interventions, peer and ongoing support and improvement of orientation programs and low reporting of social support strategies were highlighted. The paucity of data on funding availability, the absence of data on longitudinal assessment of intervention outcomes and the general quality of the publications indicates a need for improvement. Further studies are needed to address these gaps and to follow up on the proposals for more effective strategies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Steve Storey and Dr. Ana Silva for guidance during the study.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CaLF

Communication and Language Feedback

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- ERIC

Education Resources Information Center

- GIPSIE

Gippsland Inspiring Professional Standards among International Experts

- IMG

International Medical Graduates

- NA

Not Applicable/ Available

- NS

Not Stated

- PICO

Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes

- POD

Program for Oversea-trained Doctors

- ESR

Extension for Scoping Reviews

- WBI

Welcome Back Initiative

Authors’ contributions

Concept and Design – EPN and OEO; methodology – EPN and OEO.; Database literature search – EPN; Selection of papers and Data acquisition – EPN, DCO and OEO; Data analysis – EPN and DCO; Manuscript preparation and review – EPN, DCO and OEO; Research administration - EPN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Guarantor – EPN.

Funding

No funds or grants were received for this study.

Data availability

All data has been included in the main article and supplemental file.

Declarations

No part of this manuscript has been presented at a scientific meeting or conference. Neither have the results been published in part or full or are currently submitted for publication considerations with another journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This was not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kehoe A, Metcalf J, Carter M, McLachlan JC, Forrest S, Illing J. Supporting international graduates to success. Clin Teach. 2018;15(5):361–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davda LS, Gallagher JE, Radford DR. Migration motives and integration of international human resources of health in the United Kingdom: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies using framework analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pemberton M, Gnanapragasam SN, Bhugra D. International medical graduates: challenges and solutions in psychiatry. BJPsych Int. 2022;19(2):30–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astor A, Akhtar T, Matallana MA, Muthuswamy V, Olowu FA, Tallo V, et al. Physician migration: views from professionals in Colombia, Nigeria, India, Pakistan and the Philippines. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(12):2492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrath P, Henderson D, Phillips E. Integration into the Australian Health Care System: insights from international medical graduates. Aust Fam Phys. 2009;38(10):844–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snelgrove H, Kuybida Y, Fleet M, McAnulty G. “That’s your patient. There’s your ventilator”: exploring induction to work experiences in a group of non-UK EEA trained anaesthetists in a London hospital: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healey SJR, Fakes K, Nair BR. Inequitable treatment as perceived by international medical graduates (IMGs): a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2023;13(7):e071992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sockalingam S, Khan A, Tan A, Hawa R, Abbey S, Jackson T, et al. A framework for understanding international medical graduate challenges during transition into fellowship programs. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najeeb U, Wong B, Hollenberg E, Stroud L, Edwards S, Kuper A. Moving beyond orientations: a multiple case study of the residency experiences of Canadian-born and immigrant international medical graduates. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019;24(1):103–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murillo Zepeda C, Alcala Aguirre FO, Luna Landa EM, Reyes Guereque EN, Rodriguez Garcia GP, Diaz Montoya LS. Challenges for international medical graduates in the US graduate medical education and health care system environment: a narrative review. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajpara M, Chand P, Majumder P. Role of clinical attachments in psychiatry for international medical graduates to enhance recruitment and retention in the NHS. BJPsych Bull. 2023;48(3):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Atri A, Matorin A, Ruiz P. Integration of international medical graduates in U.S. psychiatry: the role of acculturation and social support. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35(1):21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodward-Kron R, Stevens M, Flynn E. The medical educator, the discourse analyst, and the phonetician: a collaborative feedback methodology for clinical communication. Acad Med. 2011;86(5):565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jager A, Harris M, Terry R. A rapid review of challenges faced by early-career international medical graduates in general practice and opportunities for supporting them. BJGP Open. 2023;7:BJGPO.2023.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jalal M, Bardhan KD, Sanders D, Illing J. International: overseas doctors of the NHS: migration, transition, challenges and towards resolution. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(1):76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan-Gokkaya S, Higgen S, Mosko M. Qualification programmes for immigrant health professionals: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0224933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehoe A, McLachlan J, Metcalf J, Forrest S, Carter M, Illing J. Supporting international medical graduates’ transition to their host-country: realist synthesis. Med Educ. 2016;50(10):1015–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duvivier RJ, Burch VC, Boulet JR. A comparison of physician emigration from Africa to the United States of America between 2005 and 2015. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monavvari AA, Peters C, Feldman P. International medical graduates: past, present, and future. Can Fam Phys. 2015;61(3):205–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammick M, Dornan T, Steinert Y. Conducting a best evidence systematic review. Part 1: from idea to data coding. BEME Guide No. 13. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broderick A, Zoppi K. New web-based courses for IMG residents available. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(3):275–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watt D, Violato C, Lake D, Baig L. Effectiveness of a clinically relevant educational program for improving medical communication and clinical skills of international medical graduates. Can Med Educ J. 2010;1(2):e70–80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross D, Smalldridge A. Improving written and verbal communication skills for international medical graduates: a linguistic and medical approach. Med Teach. 2011;33(7):e364–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wearne SM, Brown JB, Kirby C, Snadden D. International medical graduates and general practice training: how do educational leaders facilitate the transition from new migrant to local family doctor? Med Teach. 2019;41(9):1065–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christie J, Pryor E, Paull AM. Presenting under pressure: communication and international medical graduates. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):532-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodward-Kron R, Flynn E, Delany C. Combining interdisciplinary and International Medical Graduate perspectives to teach clinical and ethical communication using multimedia. Commun Med. 2011;8(1):41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fry M, Mumford R. An innovative approach to helping international medical graduates to improve their communication and consultation skills: whose role is it? Educ Prim Care. 2011;22(3):182–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright A, Regan M, Haigh C, Sunderji I, Vijayakumar P, Smith C, et al. Supporting international medical graduates in rural Australia: a mixed methods evaluation. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGrath P, Henderson S, Holewa HA, Henderson D, Tamargo J. International medical graduates’ reflections on facilitators and barriers to undertaking the Australian Medical Council examination. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36(3):296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker D, Robson J. Communication training for international graduates. Clin Teach. 2012;9(5):325–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamoda HM, Sacks D, Sciolla A, Dewan M, Fernandez A, Gogineni RR, et al. A roadmap for observership programs in psychiatry for international medical graduates. Acad Psych. 2012;36(4):300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan A, Hawa R, Sockalingam S, Abbey SE. (Dis)orientation of international medical graduates: an approach to foster teaching, learning, and collaboration (TLC). Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(2):104–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris A, Delany C. International medical graduates in transition. Clin Teach. 2013;10(5):328–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins NS, Taraporewalla K, Edirippulige S, Ware RS, Steyn M, Watson MO. Educational support for specialist international medical graduates in anaesthesia. Med J Aust. 2013;199(4):272–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webb J, Marciniak A, Cabral C, Brum RL, Rajani R. A model for clinical attachments to support international medical graduates. BMJ. 2014;348:g3936. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bansal A, Buchanan J, Jackson B, Patterson D, Tomson M. Helping international medical graduates adapt to the UK general practice context: a values-based course for developing patient-centred skills. Educ Prim Care. 2015;26(2):105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodward-Kron R, Fraser C, Pill J, Flynn E. How we developed Doctors Speak Up: an evidence-based language and communication skills open access resource for International Medical Graduates. Med Teach. 2015;37(1):31–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sockalingam S, Thiara G, Zaretsky A, Abbey S, Hawa R. A transition to residency curriculum for international medical graduate psychiatry trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):353–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katz C, Barnes M, Osta A, Walker-Descartes I. The Acculturation toolkit: an orientation for pediatric international medical graduates transitioning to the United States Medical System. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahmood M, Kasfiki E, Blackmore A, Wright D, Ganesh S, Bestley J. Use of high-fidelity simulation to ensure inclusivity and equality of international medical graduates. Int J Healthc Simul. 2022;2(1):A37–47. 10.54531/DNRM7064.

- 43.Alberta International Medical Graduate Program. Canada Externship Handbook 2024 Edition for Externs; 4-37. https://www.aimg.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Externship-Handbook-2024.pdf.

- 44.McGrath P, Henderson D, Holewa HA. Liaison officer for international medical graduates: research findings from Australia. Illness Crisis Loss. 2013;21(1):15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung CR. NHS induction and support programme for overseas-trained doctors. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):531–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slowther A, LewandoHundt GA, Purkis J, Taylor R. Experiences of non-UK-qualified doctors working within the UK regulatory framework: a qualitative study. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(4):157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernandez-Pena JR. Integrating immigrant health professionals into the US health care workforce: a report from the field. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(3):441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emery L, Jackson B, Oliver P, Mitchell C. International graduates’ experiences of reflection in postgraduate training: a cross-sectional survey. BJGP Open. 2022;6(2):BJGPO.2021.0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allotey J. The impact of peer-led support on the experiences and challenges of international medical graduates in the internal medicine training programme. Future Healthc J. 2022;9(Suppl 2):54–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tilsed F, Cattermole H, Mills C. Linguistic coaching: a pilot study of one-to-one near-peer coaching for international GP trainees in Yorkshire. Educ Prim Care. 2023;34(1):31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nestel D, Regan M, Vijayakumar P, Sunderji I, Haigh C, Smith C, et al. Implementation of a multi-level evaluation strategy: a case study on a program for international medical graduates. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2011;8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.GMC. The changing medical workforce. United Kingdom; 2020. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/somep-2020-chapter-3_pdf-84686032.pdf.

- 53.Lineberry M, Osta A, Barnes M, Tas V, Atchon K, Schwartz A. Educational interventions for international medical graduates: a review and agenda. Med Educ. 2015;49(9):863–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGrath PD, Henderson D, Tamargo J, Holewa HA. ‘All these allied health professionals and you’re not really sure when you use them’: insights from Australian international medical graduates on working with allied health. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35(4):418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warwick C. How international medical graduates view their learning needs for UK GP training. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25(2):84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henderson D, McGrath PD, Patton MA. Experience of clinical supervisors of international medical graduates in an Australian district hospital. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41(4):365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khoujah D, Ibrahim A. Exploring teamwork challenges perceived by international medical graduates in emergency medicine residency. West J Emerg Med. 2023;24(1):50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao NR. “A little more than kin, and less than kind”: U.S. immigration policy on international medical graduates. Virtual Mentor VM. 2012;14(4):329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Balasubramanian M, Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Watkins K, Short SD. Overseas-qualified dentists’ experiences and perceptions of the Australian Dental Council assessment and examination process: the importance of support structures. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(4):412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hashim A. Educational challenges faced by international medical graduates in the UK. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:441–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hudspeth JC, Rabin TL, Dreifuss BA, Schaaf M, Lipnick MS, Russ CM, et al. Reconfiguring a one-way street: a position paper on why and how to improve equity in global physician training. Acad Med. 2019;94(4):482–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kelly L, Sankaranarayanan S. Differential attainment: how can we close the gap in paediatrics? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2023;108(1):54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data has been included in the main article and supplemental file.