Abstract

Background

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is a highly aggressive malignancy with limited treatment options. Identifying novel therapeutic agents for ICC is crucial. Numerous natural compounds have demonstrated remarkable anti-tumor activities and can enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy. Thus, our study aimed to screen natural compounds for their anti-ICC effects.

Methods

A total of 640 natural compounds were screened using a cell viability assay to identify potential compounds that could inhibit the proliferation of ICC cells. The anti-ICC effects of Lycorine Hydrochloride (LY) were confirmed through cell proliferation, colony formation, cell cycle, migration, and invasion assays, as well as in xenograft models. Bioinformatics analyses and validation experiments (Quantitative real-time PCR, Western blot, and immunostaining assays) were utilized to investigate the roles of genes (SQLE, FDFT1, and PTPN11) in ICC. RNA sequencing and immunofluorescence staining were performed to elucidate underlying molecular mechanisms.

Results

LY was identified as a potential ICC inhibitor, exhibiting anti-ICC effects both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, LY inhibited cholesterol synthesis in tumor cells by down-regulating the expression of SQLE and FDFT1. The knockdown of SQLE or FDFT1 significantly inhibited ICC cell proliferation and colony formation. RNA sequencing confirmed that inhibition of FDFT1 suppressed the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, while SQLE inhibition affected specific oncogenic pathways. Additionally, immunofluorescence staining revealed that down-regulation of SQLE reduced PTPN11 expression and inhibited its nuclear translocation. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of SQLE and FDFT1 by LY significantly enhanced sensitivity to several common chemotherapeutic drugs for ICC. Notably, the combination of LY and Gemcitabine (GEM) displayed the most potent synergistic anti-tumor effect across various tumor types.

Conclusion

These findings identify Lycorine Hydrochloride as a promising treatment alternative for ICC and propose a novel combination strategy (LY + GEM) for treating multiple solid tumors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12964-025-02318-5.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, Lycorine Hydrochloride, Cholesterol biosynthesis, SQLE, FDFT1

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is a highly fatal cancer of the liver bile ducts which accounts for 10–15% of all primary liver cancers [1]. Although surgical intervention is commonly favored as the primary therapeutic approach, it is insufficient as few patients are eligible for surgery due to the rapid ICC progression and metastasis. Furthermore, the 5-year survival rate of surgically resected ICC patients is only 25–40% owing to the high recurrence rate [2]. On the other hand, first-line chemotherapy with Gemcitabine (GEM)/cisplatin-based combination therapy for advanced ICC provides modest benefits as it only confers a median overall survival of < 1 year. However, the combined therapy offers a 3-month survival advantage over GEM alone [3]. Consequently, studies are currently being conducted to explore the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy in combination with other treatments to increase the percentage of patients who respond to chemotherapy [4].

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark feature of numerous malignancies [5], and reprogramming cholesterol biosynthesis may be crucial in pathways promoting cell growth, survival, and other cancer-related processes [6]. Through various enzymatic reactions, the endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis pathway converts acetyl-CoA into cholesterol [7]. Two key rate-limiting enzymes, farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 (FDFT1) and squalene epoxidase (SQLE), are critically involved in these enzymatic reactions. While FDFT1 controls squalene synthesis, SQLE catalyzes the rate-limiting phase of squalene conversion to squalene 2,3-oxide [8]. Moreover, FDFT1 and SQLE are expressed abnormally in various cancers and are considered potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer progression [9].

There is growing evidence of FDFT1 involvement in various types of cancer, and most studies have found that increased FDFT1 expression is associated with tumor progression. For example, FDFT1 positively correlates with tumor cell proliferation and stemness in epithelial ovarian cancer [10]. Similarly, FDFT1 over-expression in lung cancer promotes metastasis via enhancing the TNFR1-NF-κB pathway activation and up-regulating MMP1 [11]. In prostate cancer, elevated FDFT1 levels are observed in tumor tissues, and FDFT1 inhibition leads to decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis [12]. In the early stages of colorectal cancer, FDFT1 expression is heightened, which correlates with poor differentiation and advanced tumor stage. Additionally, FDFT1 up-regulation is an independent indicator of unfavorable overall and relapse-free survival among colorectal cancer patients. Moreover, FDFT1 promotes colon cancer cell proliferation and growth [13]. However, potential depletion of FDFT1 associated with malignant progression and poor prognosis has also been reported in colorectal cancer. In this context, FDFT1 functions as a key tumor suppressor via negatively regulating the AKT/mTOR/HIF1α signaling pathway in colorectal cancer [14]. Nevertheless, the reason for FDFT1 inconsistency in tumors is yet to be fully investigated.

On the other hand, SQLE has consistently been identified as an oncogene in various tumors. For instance, SQLE over-expression is more prevalent in aggressive breast cancer subtypes and serves as an independent adverse prognostic factor [15]. By promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, SQLE also contributes to tumor progression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [16]. Furthermore, SQLE drives tumor development in hepatocellular carcinoma via STRAP transcriptional activation and the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway [17]. Additionally, SQLE-mediated tumor progression in pancreatic cancer involves several pathways, including attenuation of ER stress and the activation of the lipid raft-regulated Src/PI3K/Akt, the lncRNA-TTN-AS1/miR-133b/SQLE axis, the mTORC1, and the TNFα/NF-κB signaling pathway [18–20]. Furthermore, SQLE affects tumor immunoinvasion and immunotherapy outcomes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma [19]. By regulating the p53 signaling pathway, SQLE also promotes cervical cancer progression [21]. It has also been reported that SQLE is over-expressed and associated with poor survival in aggressive prostate cancer [22]. Furthermore, SQLE promotes cell proliferation in colorectal cancer through calcitriol accumulation and the CYP24A1-mediated MAPK signaling pathway [23]. Additionally, SQLE facilitates proliferation and metastasis in lung SCC through the ERK signaling pathway [24]. Targeting SQLE shows great promise in cancer treatment, particularly with the inhibitor terbinafine as a potential therapeutic strategy for solid tumors [25]. However, the involvement of SQLE and FDFT1 in ICC remains unexplored.

Herein, we performed a high-throughput screening and identified Lycorine Hydrochloride (LY) as a promising medication for treating ICC. Mechanically, LY blocks cholesterol biosynthesis pathways in ICC cells via FDFT1 and SQLE down-regulation. Further investigation into the roles of FDFT1 and SQLE in ICC revealed their oncogenic properties. Notably, we discovered that suppressing SQLE, rather than FDFT1, has a broader impact on various signaling pathways. Additionally, we identified PTPN11 as a SQLE downstream target, and SQLE could regulate PTPN11 nuclear translocation. Moreover, we discovered that when combined with GEM, LY exerts the most potent synergistic effect compared to other chemotherapeutic agents. This combination regimen demonstrates a synergistic effect across multiple tumor cell lines and effectively reduces the expression of FDFT1 and SQLE. Therefore, these findings collectively imply that LY + GEM may exert an anti-tumor effect by regulating FDFT1 and SQLE expressions. In conclusion, we propose LY, a novel therapeutic compound, as a potential ICC treatment alternative. We also devised an innovative combination therapy regimen comprising the simultaneous administration of LY and GEM, which has great potential for treating various types of tumors.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Three cell lines (RBE, HuCCT1, and QBC939) were acquired from the Immocell Biotechnology (Xiamen, China), which also authenticated them. All cell lines were grown in an RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Gibco). Cells were cultured in optimal conditions, that is, 37 °C, 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. A library of 640 natural compounds (Target Mol) was prepared as stock solutions in DMSO at a 10 mM concentration for the screening. Gemcitabine (T0251), (+)-JQ-1 (T2110), THZ1 (T3664), panobinostat (T2383), cisplatin (T1564), 5-Fluorouracil (T0984), and Lycorine Hydrochloride (T2774) were purchased from Target Mol (Shanghai, China).

Cell proliferation and clone formation assay

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) kit (ALX-850-039-KI02, Enzo) was used to determine cell proliferation. For the clone formation assay, 1000 cells were seeded into six-well plates and cultured in an RPMI-1640 medium containing various concentrations of different drugs. After 24 h of treatment, cells were transferred to a fresh complete medium and cultured for 2 weeks. Subsequently, the colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with a 0.1% crystal violet solution.

Cell cycle and apoptosis assay

Cells were collected after 24 h of treatment with different drug concentrations. The collected cells were then fixed in 70% ethanol at 4 °C overnight and stained with Propidium Iodide (P4170, Sigma) for cell cycle analysis. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, the FITC Annexin-V apoptosis detection kit (556547, BD Biosciences) was used to determine apoptosis. Cell cycle and apoptosis were analyzed using flow cytometry (Accuri C6, BD Biosciences).

Transwell cell migration and invasion assay

The cell migration assay was performed in a 24-well plate with an 8 μm pore-size polycarbonate membrane. The top side of the membrane was coated with matrigel and placed in the upper chamber for cell invasion assay. Cells were seeded into the upper chambers, while the lower chambers were filled with complete medium. The chambers were removed after 24 h, and the inner side was wiped with cotton swabs. The cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and counted under a light microscope.

Plasmids and cell transfections

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences were cloned into psiF-copGFP vectors (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). The shRNA sequences used in this study are presented in Supplemental Table 1. To establish stably transfected cell lines, lentivirus was introduced into HEK-293T cells with the second-generation packaging system pMD2.G and psPAX2, and harvested at 48 h after transfection. ICC cell lines were transduced with virus in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrene and then screened with puromycin for 7 days.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated by using Trizol reagent and reverse transcribed with a StarScript II First-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (A212-05, GenStar) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was conducted in triplicate using the SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). The mRNA expression of genes was evaluated by using the 2−△△Ct method. Supplemental Table 2 outlines the primers sequences used in this study.

Western blot analyses and Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling) and then subjected to Western blot analysis using standard protocols. Primary antibodies for the target proteins were as follows: IDI2(16701-1-AP, Proteintech), IDI1(ab97448, Abcam), DHCR7 (ab103296, Abcam); the other antibodies for SQLE (A2428), FDFT1 (A4651), DHCR24 (A5402), HMGCS1 (A3916), MVK (A20906) and PTPN11 (A19112) were all purchased from ABclonal Technology. β-actin antibody (H11459) was purchased from Sigma and served as the loading control. The immunoreactive proteins were visualized with SuperSignal West Dura Chemiluminescent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For immunofluorescence staining, cells were grown in chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde dissolved in PBS for 20 min and permeabilized in 0.5% Tween 20 and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Cells were blocked with goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 h at room temperature and incubated with PTPN11(1:500; no. 05-636, Millipore) or SQLE antibody (1:500; no. 05-636, Millipore) overnight at 4 °C and secondary antibody (1:2000; goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 568) for 1 h. The slides were mounted with coverslips using ProLong Gold antifade reagent and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstain (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Molecular docking

The molecular structure of Lycorine Hydrochloride (ZINC4023011 ID_4091) was downloaded from the ZINC20 database (https://zinc20.docking.org/). The 3D structure of the target protein was downloaded from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org). The water molecules and the original ligands were removed from the target protein using PyMOL 2.0 (https://pymol.org/2/). The maestro software was used for molecular docking, and PyMOL 2.0 was employed for results visualization.

Animal experiments

Female BALB/C nude mice were purchased from Rise Mice Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Zhaoqing, China). For in vivo experiments, six-week-old BALB/C nude mice were subcutaneously injected with RBE cells (2 × 106 cells). The tumor volume was measured every 5 days with an electronic caliper and calculated using the following formula: 0.5 × length × width2. When the tumor volume reached ~ 50 mm3, treatments were carried out through intraperitoneal injection. Six tumor-bearing mice were selected for each treatment group. Each group was injected with PBS, LY (0.2 mg/kg), LY (0.4 mg/kg), GEM (10 mg/kg), LY + GEM (0.2 mg/kg LY + 10 mg/kg GEM), injections were given three times a week. After treatment for 3 weeks, the mice were sacrificed under anesthesia, and tumor tissues were collected for further analysis. Changes in tumor volume were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v.8.02 (www.graphpad.com), and statistical significance was determined through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Histology immunohistochemistry analyses

All paraffin-embedded tissues of patients in this study were obtained with informed patient consent (n = 5 pairs of adjacent and tumorous tissues, totaling 10 tissues). For immunohistochemistry staining, deparaffinized and rehydrated sections were boiled in Na-citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) for 30 min for antigen retrieval. This was followed by incubation with primary antibodies and developed using the Ultra Vision Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were acquired using an Olympus IX51 microscope and processed using cellSens Dimension software.

Measurement of cholesterol content

Amplex Red Cholesterol and Cholesteryl Ester Assay Kit from Beyotime Biotechnology (S0211S) was used to detect the content of cholesterol by following the manufacturer’s instructions. The detection principle is that Cholesteryl ester is first hydrolyzed by Cholesterol esterase to produce Free cholesterol and fatty acids (FA). Free Cholesterol is further oxidized with oxygen under the action of Cholesterol oxidase (Cho) to form H2O2 and Cholestenone. The total cholesterol content was determined by detecting the fluorescence intensity or absorbance of the reaction product of H2O2 and Amplex Red. The fluorescence intensity and absorbance of resorufin were proportional to the content of cholesterol. From the cholesterol standard solution provided within the kit, a standard curve can be set to calculate the cholesterol, cholesteryl ester, and total cholesterol content in the sample.

RNA-sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells for RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) using the TRI Reagent and Direct-zol RNA kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced by a sequencing service company (Novogene, Beijing, China) using the Illumina sequencing platform. Log2|Fold Change| ≥ 1 and P < 0.05 were used as a cut-off to define up-regulated or down-regulated genes. Metascape (https://metascape.org) and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) were used to identify enriched molecular pathways. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) among the genes was determined on the STRING (https://string-db.org/) database and visualized using Cytoscape 3.8.2 (https://cytoscape.org/).

Gene expression and bioinformatics analysis from the public database

Data were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/) and the gene expression microarray datasets GSE107943 and GSE215997 were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) to explore the expression profile of genes. To analyze the overall survival (OS), we utilized patient data from both GSE107943 and TCGA. In a nutshell, patients were segregated into two groups, one with high expression and the other with low expression of the gene under examination. Besides, the OS and DNA methylation-based stemness index (DNAsi) data for SQLE and FDFT1 in various tumor types in TCGA database were obtained from the SangerBox database (http://SangerBox.com/Tool) [26, 27].

Statistical analysis

All data were obtained from at least three independent experiments and were expressed as mean ± SD. The analysis of data was performed by GraphPad Prism v.8.02 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was performed for two-group comparisons and one-way ANOVA analysis was conducted for multiple group comparisons. Correlation analysis was performed by Pearson correlation test. Differences were considered significant when the P value was less than 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant).

Results

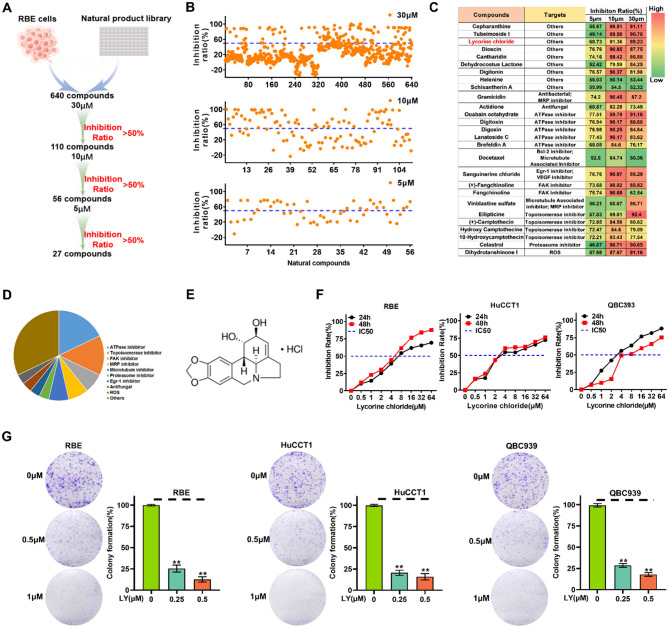

Natural compounds screening identified Lycorine Hydrochloride as a potential ICC inhibitor

We performed a high-throughput screening of a compound library comprising 640 natural compounds in RBE cells to identify small molecules that suppress ICC cell growth. In brief, all compounds were initially screened at a 30 µM concentration, and the cytotoxicity against RBE was assessed using a CCK-8 assay kit (Fig. 1A). From the search, 110 compounds elicited a > 50% reduction in cellular growth and were triaged for further inspection. Of these, 56 and 27 compounds had an IC50 at 10 µM and 5 µM, respectively (Fig. 1B). The 27 compounds were divided into several categories, including ATPase inhibitor, Topoisomerase inhibitor, FAK inhibitor, MRP inhibitor, and other targets based on their putative targets (Fig. 1C and D). Following the literature search, one of the 27 compounds designated as Lycorine Hydrochloride (LY) attracted our attention (Fig. 1E). According to previous research, LY exerts several pharmacological effects, including anti-fungal [28], anti-virus [29], anti-inflammatory [30], and more particularly, anti-tumor impacts [31–36]. However, the potential bioactivities of LY in ICC progression are yet to be determined. Thus, we selected LY to further explore its impact on ICC. We assessed the impact of LY on three types of human ICC cells (RBE, QBC939, and HuCCT1) at various concentrations. The treatment of different LY concentrations resulted in dose and time-dependent growth inhibition in all three ICC cell lines, with IC50 values of 5 µM, 4 µM, and 4 µM, respectively (Fig. 1F). Additionally, LY effectively reduced ICC cell colony formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1G). According to the flow cytometry analysis results, LY arrested the cell cycle in the G2/M phase and triggered apoptotic cell death in different ICC cells (Fig. S1A and B). Moreover, wound-healing and trans-well assays revealed that LY impaired the migration and invasion capabilities of the tested ICC cells (Fig. S1C and D). These findings collectively indicate the potential of LY as a candidate compound for inhibiting ICC development.

Fig. 1.

Screening of natural compounds revealed Lycorine Hydrochloride (LY) as a potential ICC inhibitor. (A) Flow chart showing the screening process of natural compounds. (B) Scatter plot showing the inhibition ratio of RBE cells treated with 640 natural compounds. (C) Distribution of putative targets and the inhibition ratio in RBE cells of the top 27 ranked natural compounds categorized and listed. (D) Pie chart displaying the distribution of targets of the top 27 natural compounds. (E) The chemical structure of LY (Molecular Formula: C17H20NO4+; Formula Weight: 302.35). (F) The cell viability of RBE cells after 24–48 h incubation with different concentrations of LY. (G) The colony formation assay to determine the dose-dependent inhibitory effect of LY on ICC cells. The number of colonies was counted under a microscope. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three simultaneously performed experiments (B, F and G). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

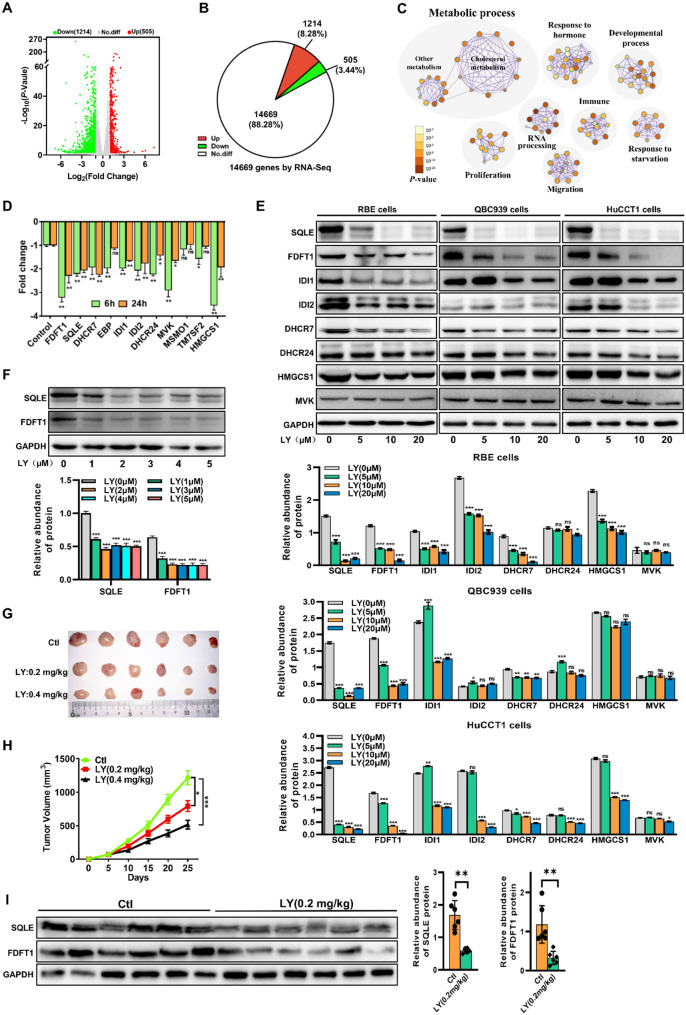

LY interfered with cholesterol metabolism in ICC via SQLE and FDFT1

We conducted RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on RBE cells treated with LY or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 24 h to investigate the mechanism of LY inhibiting the growth of ICC cells. We identified 1719 differently expressed genes (DEGs), of which 1214 and 505 were down-regulated and up-regulated, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). To functionally characterize this outcome, we performed pathway enrichment analyses to identify specific molecular pathways that were differentially enriched following LY treatment. We discovered a significant decrease in the metabolic process, particularly the cholesterol biosynthetic process (Fig. 2C). To verify this change, we examined the cholesterol levels in ICC cells after LY treatment and found that cholesterol content was reduced in ICC cells after LY treatment compared with the control group (Fig. S2A). We then analyzed the DEGs in the pathway to examine the relationship between the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway and the anti-ICC activity of LY. We discovered that the mRNA expression of the key rate-limiting enzymes in the cholesterol synthesis pathway was significantly downregulated following LY treatment (Fig. 2D). We next evaluated the protein levels of the DEGs in LY-treated RBE cells to confirm the above findings and observed down-regulated expression of most rate-limiting enzymes in cholesterol metabolic pathways, particularly SQLE and FDFT1 (Fig. 2E). Notably, even at lower LY concentrations, SQLE and FDFT1 protein levels were significantly reduced (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, we constructed mouse xenograft models using RBE cells to determine the anti-ICC effect of LY in vivo. Compared to the vehicle group, significantly smaller tumor volumes were observed in the LY-treated group (Fig. 2G and H). Additionally, FDFT1 and SQLE expressions were reduced in tissues from mouse xenograft models of RBE cells (Fig. 2I). Finally, we performed molecular docking between LY and SQLE or FDFT1, both of which demonstrated good docking activity between SQLE or FDFT1 protein and LY (Fig. S2B-D). More importantly, LY also reduced cholesterol levels in the serum and tumor tissues of ICC model mice (Fig. S2E). These findings suggest that LY exerts an anti-ICC effect by down-regulating rate-limiting enzymes (especially FDFT1 and SQLE) in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway.

Fig. 2.

Lycorine Hydrochloride affected cholesterol metabolism in ICC via SQLE and FDFT1. (A) A volcano plot showing the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between treatment and non-treatment of LY as determined by the RNA-seq analysis. (B) RNA-seq identified 14,669 genes expressed, among which 505 genes were up-regulated and 1214 genes were down-regulated. (C) Pathway enrichment of the DEGs in RBE cells treated with LY for 24 h. Metascape was used to conduct pathway enrichment, and the network was visualized using Cytoscape 3.8.2. Network of enriched terms, circles are Ontology (GO) terms, colored by P value, where terms containing more genes tend to have a more significant P value. (D) The mRNA expression profile of the DEGs associated with the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway in RBE cells treated with LY for 6 h and 24 h. ns, not significant; RNA expression levels are presented as log2 fold change (log2 FC) relative to the control group; negative values indicate downregulation. (E) Western blot results showing the protein expression level of the DEGs in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway in different ICC cells after treatment with 0, 5, 10, 20 µM LY for 24 h. (F) Western blot results showing the protein expression level of FDFT1 and SQLE in RBE cells after treatment with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 µM LY for 24 h. (G and H) Representative tumor image (G) and tumor volume (H) of RBE cells-derived xenografts treated with different concentrations of LY or PBS (Ctl group), n = 6. (I) The protein expression of SQLE and FDFT1 in the tumor tissues from mouse xenograft models of RBE cells (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SD of three simultaneously performed experiments (D-F and I). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

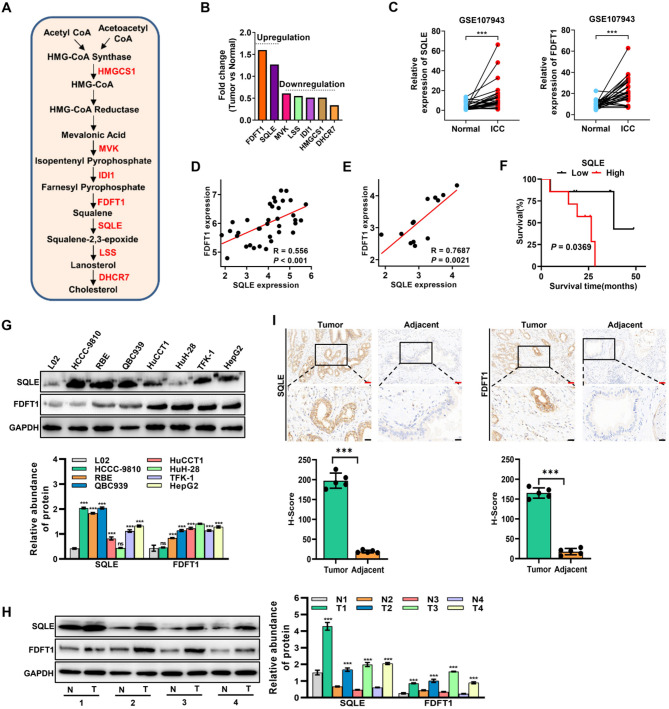

FDFT1 and SQLE play oncogenic roles in ICC

Various rate-limiting enzymes are critically involved in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 3A). To further evaluate the role of rate-limiting enzymes in cholesterol biosynthesis in ICC progression, we analyzed their expression in tissues of ICC patients using public databases. Compared to normal tissues, only FDFT1 and SQLE expressions were higher in ICC patient tissues from both the TCGA and GEO databases (GSE107943) (Fig. 3B and C, and Fig. S3A). Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between FDFT1 expression and SQLE expression in tissue samples from ICC patients (Fig. 3D). Notably, the positive correlation was even more striking in ICC organoids (GSE215997) (Fig. 3E). Additionally, FDFT1 and SQLE expressions were elevated in most tumors from the TCGA database (Fig. S3B and C). Consequently, our subsequent analyses focused on FDFT1 and SQLE genes. Using data from the TCGA database, we analyzed the correlation between FDFT1 or SQLE and the DNA methylation-based stemness index (mDNAsi) of various malignancies [26]. According to the results, SQLE was positively correlated with the mDNAsi of almost all types of tumors, including cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL) (R = 0.325, P = 0.009) (Fig. S3D), whereas FDFT1 was positively correlated with only three tumors (LGG, GBMLGG, and THYM) (Fig. S3E). We further analyzed the correlation between SQLE or FDFT1 and the overall survival (OS) rate of various tumors using data from the TCGA database. The results revealed that high SQLE expression was correlated with poor prognosis in different tumors (Fig. S3F), whereas high FDFT1 expression was associated with poor prognosis in only five tumors (COAD, READ, KIPAN, UVM, and LGG), and in other tumors (MESO, KICH, PAAD, LAML, ACC, GBM, and KIRC), high FDFT1 expression was positively associated with longer survival in patients (Fig. S3G). Using ICC patient information (GSE107943), we found that high SQLE expression was positively correlated with poor prognosis in ICC patients, although high SQLE expression was not correlated with poor prognosis in patients in the TCGA CHOL data (Fig. 3F). We performed an immunoblot analysis to further validate the above results and discovered that FDFT1 and SQLE protein levels were highly expressed in most ICC cell lines and patient tissues than those in human normal hepatocytes or tissues (Fig. 3G and H). Furthermore, the IHC results showed that FDFT1 and SQLE were highly expressed in clinical ICC samples compared to adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig. 3I). These results collectively imply that FDFT1 and SQLE may have oncogenic properties and positively correlate with ICC development.

Fig. 3.

FDFT1 and SQLE have oncogenic roles in ICC. (A) Schematic diagram of the cholesterol biosynthesis-related genes. (B) The expression level of seven cholesterol biosynthetic-associated genes in ICC tissues from TCGA database. (C) The expression level of SQLE (left) and FDFT1 (right) in 27 pairs of ICC tumor and adjacent liver tissues from GEO database (GSE107943). (D) Spearman’s correlation analysis of the expression of SQLE and FDFT1 in CHOL patients from TCGA database (n = 36). (E) Spearman’s correlation analysis of the expression of SQLE and FDFT1 in ICC organoids (GSE215997, n = 13). (F) The OS analysis of human ICC samples from GSE107943 based on SQLE expression. (G) The protein expression level of FDFT1 and SQLE in human normal liver cells (L02) and ICC cell lines. (H) The protein expression level of FDFT1 and SQLE in tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues of ICC patients. (I) Representative IHC analysis of SQLE and FDFT1 expression in paired adjacent and tumorous tissues from ICC patients (n = 5 pairs, 10 tissues in total). Red scale bar: 50 μm; Black scale bar: 20 μm. Data are presented as means ± SD of three simultaneously performed experiments (G and H). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

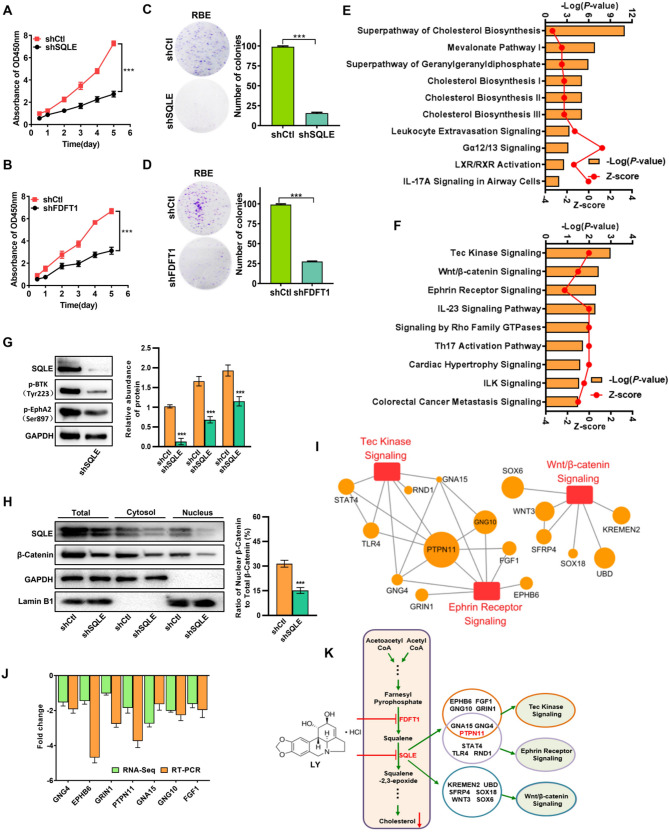

Silencing FDFT1 and SQLE inhibits ICC cell proliferation

To investigate the contribution of FDFT1 and SQLE in ICC progression, we utilized the loss-of-function approach to evaluate their effects on RBE cells (Fig. S4A). We discovered that silencing FDFT1 or SQLE effectively decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 4A and B) and attenuated the RBE cell colony formation ability (Fig. 4C and D). Subsequently, we performed RNA-seq (Fig. S4B) and IPA analyses to investigate the mechanisms underlying the anti-ICC effect after FDFT1 or SQLE inhibition. We discovered that the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway was the most significantly affected after FDFT1 silencing in RBE cells (Fig. 4E). This finding was expected as FDFT1 acted as a rate-limiting enzyme in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. On the other hand, the top three enriched canonical pathways after SQLE silencing in RBE cells were the Tec kinase, the Wnt/β-catenin, and the Ephrin receptor signaling pathways (Fig. 4F). To experimentally validate these bioinformatics predictions, we performed Western blot (WB) analyses to assess the activation status of these pathways. Specifically, WB analyses revealed that SQLE knockdown led to a significant reduction in the expression of phosphorylated Tec kinase (BTK Y223) and Phospho-EPHA2-S897, the active forms of the Tec kinase and Ephrin receptor pathways, respectively (Fig. 4G). For the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, SQLE inhibition resulted in a notable decrease in total β-catenin levels. Concurrently, quantitative analysis of subcellular β-catenin distribution showed a profound reduction in the nuclear β-catenin ratio (nuclear/total β-catenin), directly indicating impaired nuclear translocation of β-catenin—a critical step for Wnt pathway activation (Fig. 4H). Collectively, these results establish that SQLE inhibition suppresses ICC progression through multi-pathway regulation, contrasting with the single-pathway effect of FDFT1 inhibition. Subsequently, we analyzed the DEGs in the top three pathways after SQLE inhibition and found that PTPN11 had the biggest fold change (Fig. 4I, and Fig. S4B). We also analyzed the PPI network of those DEGs and identified PTPN11 as the most core gene (Fig. S4C). Furthermore, subsequent experiments showed that PTPN11 was significantly down-regulated in RBE cells after SQLE inhibition (Fig. 4J). Our results collectively suggest that inhibiting FDFT1 can result in anti-ICC effects, particularly via interrupting the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, whereas SQLE inhibition can exert anti-ICC effects by influencing multiple signaling pathways, especially the Tec kinase, the Wnt/β-catenin and the Ephrin receptor signaling pathways, with PTPN11 being one of its downstream targets (Fig. 4K).

Fig. 4.

Silencing FDFT1 and SQLE inhibits the proliferation of ICC. (A-B) Cell proliferation was measured after SQLE (A) or FDFT1 (B) silencing in RBE cells. (C-D) The effect of SQLE (C) or FDFT1 (D) knockdown on colony formation in RBE cells. (E and F) IPA canonical pathways analysis of the DEGs identified via RNA-seq in RBE cells stably transfected with shFDFT1 (E) or shSQLE (F), compared with RBE cells stably transfected with shcontrol (shCtl). (G) Western blot validation of Tec kinase and Ephrin receptor signaling pathways in shCtl- and shSQLE-transfected RBE cells. Phosphorylated BTK (Y223) and Phospho-EPHA2 (S897) levels were detected to assess pathway activation. (H) Subcellular distribution of β-catenin in shCtl- and shSQLE-transfected RBE cells. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were separated, and β-catenin levels were detected by Western blot. GAPDH (cytoplasmic marker) and Lamin B1 (nuclear marker) served as loading controls. Total β-catenin levels were calculated as the sum of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. (I) The top three enriched pathways and their corresponding DEGs in SQLE silenced RBE cells. The red boxes represent the signaling pathways, whereas the orange circles represent the associated genes. The size of each circle was determined by the -Log10(P value) associated with the respective gene. (J) Real-time PCR validation of the expression profile of some DEGs from RNA-seq data; RNA expression levels are presented as log2 fold change (log2 FC) relative to the control group; negative values indicate downregulation. (K) Schematic illustration that LY negatively regulates the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway through inhibiting FDFT1 and SQLE, and inhibition of SQLE exerts anti-ICC effect by influencing multiple signaling pathways. Data are presented as means ± SD of three simultaneously performed experiments (A-D, G-H, J). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

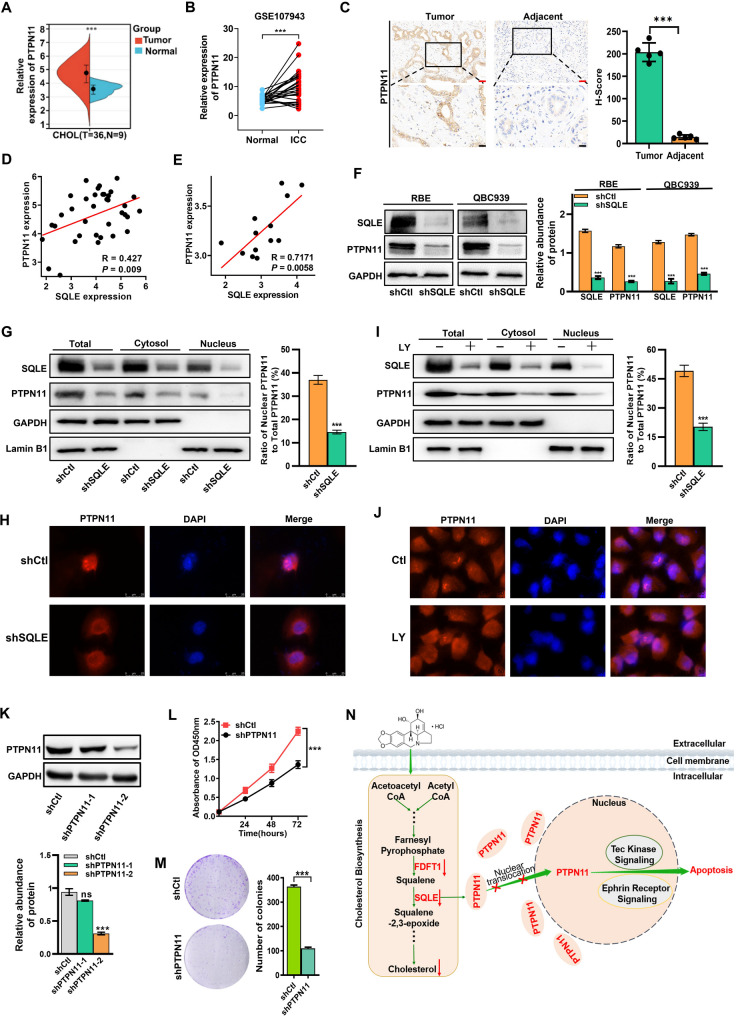

SQLE inhibits PTPN11 nuclear translocation

To establish PTPN11 as an SQLE downstream target, we first evaluated its expression in CHOL samples from the TCGA database. The results showed that PTPN11 was highly expressed in CHOL samples (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained after analyzing expression data obtained from a different data set (GSE107943) (Fig. 5B). Moreover, PTPN11 expression was significantly higher in ICC clinical tissues compared to adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between PTPN11 expression and SQLE expression in ICC tissues samples (Fig. 5D) or ICC organoids (Fig. 5E). According to past research, PTPN11 is mainly found at the edge of nucleoli and in the nucleus [37]. Furthermore, PTPN11 function depends on its localization, that is, cytoplasmic PTPN11 regulates cell growth and development, whereas nuclear-localized PTPN11 regulates gene transcription [38]. Herein, we demonstrated that SQLE knockdown reduced PTPN11 expression (Fig. 5F). To investigate whether SQLE inhibition impacts PTPN11 nuclear translocation, we analyzed PTPN11 protein levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Quantitative analysis of subcellular fractions revealed a significant decrease in the nuclear PTPN11/total PTPN11 ratio following SQLE knockdown (Fig. 5G, Fig. S5A), validated by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 5H), indicating SQLE primarily inhibits PTPN11 nuclear translocation, with total protein reduction likely resulting from decreased nuclear PTPN11-mediated transcriptional regulation. Given our prior finding that LY downregulates SQLE (Fig. 2E, F) and directly binds to SQLE (Fig. S2B-D), we directly assessed LY’s effect on PTPN11 localization via Western blot and immunofluorescence. LY treatment significantly reduced the nuclear PTPN11/total PTPN11 ratio in RBE cells (Fig. 5I, Fig. S5B) and decreased nuclear PTPN11 signals (Fig. 5J), demonstrating specific inhibition of nuclear translocation with a more pronounced effect on nuclear localization than global protein reduction. These results, consistent with the nuclear/total ratio data, indicate that LY inhibits PTPN11 nuclear translocation by downregulating SQLE. shRNA-mediated PTPN11 knockdown significantly suppressed ICC cell proliferation (Fig. 5K and L) and colony formation efficiency (Fig. 5M). Overall, PTPN11 is an SQLE downstream target, and LY inhibits PTPN11 nuclear translocation by downregulating SQLE (Fig. 5N).

Fig. 5.

SQLE inhibits PTPN11 nuclear translocation. (A) The expression level of PTPN11 in ICC tissues (T, n = 36) and adjacent liver tissues (N, n = 9) from TCGA database. (B) The expression level of PTPN11 in 27 pairs of ICC tumor and adjacent liver tissues from GEO database (GSE107943). (C) Representative IHC analysis of PTPN11 expression in paired adjacent and tumorous tissues from ICC patients (n = 5 pairs, 10 tissues in total). Red scale bar: 50 μm; Black scale bar: 20 μm. (D and E) Spearman’s correlation analysis for the expression of PTPN11 in CHOL patients from TCGA database (n = 36) (D) or ICC organoids (E) (GSE215997, n = 13). (F) Expression of PTPN11 after SQLE knockdown in ICC cells. (G) Western blot analysis of PTPN11 expression in nuclear, cytoplasmic, and total protein fractions in shNC (shCtl) and shSQLE RBE cells. (H) Immunofluorescence staining was performed to determine the expression of PTPN11 in RBE cells with or without SQLE knockdown. (I) Western blot analysis of PTPN11 expression in nuclear, cytoplasmic, and total protein fractions in RBE cells with or without LY (1.0 µM) for 24 h. (J) Immunofluorescence staining was performed to determine the expression of PTPN11 in RBE cells with or without LY (1.0 µM) for 24 h. (K) Knockdown of PTPN11 in RBE cells was confirmed by Western blot. (L) The proliferation of RBE cells was measured through the CCK-8 viability assay after PTPN11 silencing. (M) The effect of PTPN11 knockdown on colony formation in RBE cells. (N) Schematic illustration that LY negatively regulates the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway via inhibiting FDFT1 and SQLE, and inhibition of SQLE exerted anti-ICC effect by regulating the nuclear translocation of PTPN11. Data are presented as means ± SD of three simultaneously performed experiments (F to M). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

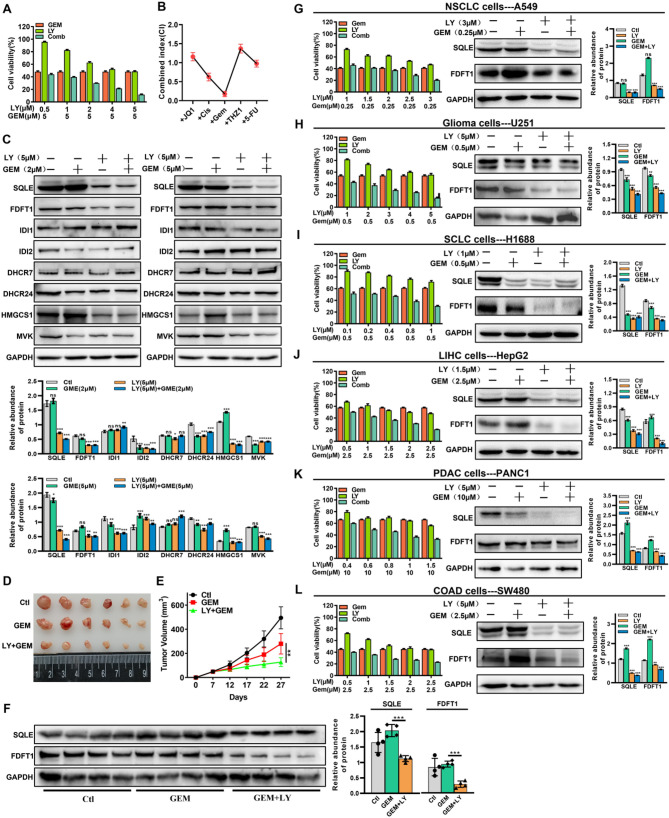

LY synergistically interacts with chemotherapy agents

According to some studies, combination therapy is a promising treatment for ICC [3]. Here, we sought to establish whether LY could cooperate or synergize with five well-known chemotherapeutic compounds. First, the IC50 of 5-FU, cisplatin(Cis), THZ1, Gemcitabine (GEM), and (+)-JQ-1 (JQ1) in RBE were found to be 15 µM, 8 µM, 200 nM, 5 µM, and 25 µM, respectively (Fig. S5A and B). These five therapeutic agents were then administered with LY, and the concentrations of LY or chemotherapeutic agents in the combination therapy were lower than their respective IC50 values. The results revealed that compared to each single-agent treatment, all the combination treatments significantly lowered RBE cell viability (Fig. 6A, and Fig. S5C-F). Remarkably, according to the Combination Index (CI), LY + GEM showed the highest and durable anti-ICC activity (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the LY + GEM combination therapy correlated with decreased SQLE and FDFT1 expression in RBE cells (Fig. 6C). Notably, the GEM + LY combination therapy elicited greater tumor suppression than treatment with GEM alone in a subcutaneous RBE cell-derived tumor model (Fig. 6D and E). Furthermore, the SQLE and FDFT1 protein expressions in the tumor tissues matched the findings in RBE cells (Fig. 6F), and LY combined with GEM indeed reduced cholesterol levels in cells and in vivo (Fig. S5G and H). Using a concentration lower than the individual IC50 values of LY and GEM in various tumor cells (Fig. S5I and J), we further explored the inhibitory effect of the LY + GEM combination therapy on NSCLC (Fig. 6G), glioma (Fig. 6H), SCLC (Fig. 6I), liver cancer (Fig. 6J), PDAC (Fig. 6K), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (Fig. 6L). The results showed that LY increased GEM’s inhibitory effect on these tumor types while decreasing SQLE and FDFT1 protein expressions. These results indicate that LY can enhance the anti-tumor effect of chemotherapy medications, particularly GEM, by suppressing SQLE and FDFT1 expressions.

Fig. 6.

LY synergistically interacts with chemotherapy agents. (A) Cell proliferation was measured in RBE cells after 24 h treatment of LY in combination with different concentrations of GEM. (B) Combination index (CI) of LY combined with different drugs was determined using CalcuSyn software. (C) Western blot analyzed the expression level of cholesterol biosynthetic associated genes in RBE cells treated with LY in combination with GEM (2 µM or 5 µM). (D and E) Representative tumor image (D) and tumor volume (E) of RBE cells-derived xenografts treated with GEM or GEM in combination with LY (n = 6). (F) Western blot analyzed the expression level of SQLE and FDFT1 in tumor tissues of RBE cells-derived xenografts. (G-L). A549 cells (G), U251 cells (H), H1688 cells (I), HepG2 cells (J), PNAC1 cells (K) and SW480 cells (L) were treated with LY in combination with different concentrations of GEM for 24 h, cell viability was measured by using CCK-8 method, and Western blot was used to analyze the protein expression level of SQLE and FDFT1. Data are presented as means ± SD of three simultaneously performed experiments (A-C, F-L). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Discussion

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is a complex clinical problem with a major therapeutic challenge [39]. Due to the insidious onset and vague clinical symptoms in the early stages, most ICC patients are often diagnosed at an advanced stage when surgical treatment is no longer feasible. Furthermore, although systemic chemotherapy is particularly important for inoperable patients [1], standard chemotherapy regimens comprising gemcitabine and platinum-based drugs may be ineffective, with a median survival of < 1 year [3]. Despite significant drug development efforts to produce efficient medications against ICC, no viable treatment has been proposed. Many natural compounds have been shown to possess remarkable anti-tumor activities or improve chemotherapy effectiveness [40, 41]. Notably, natural compounds with high biological activity and low toxicity have gained prominence in the fight against malignant tumors [42]. Furthermore, numerous bioactive natural compounds have exhibited clinical usefulness in cancer prevention and treatment, particularly by targeting various signaling molecules and pathways [43]. Therefore, we performed a high-throughput screening to identify promising natural compounds that potentially possess anti-ICC activity and identified Lycorine Hydrochloride (LY) as an ideal candidate for ICC treatment. In vitro results and mice tumor models suggest that LY effectively treats ICC.

Lycorine Hydrochloride (LY), a natural compound found in the medicinal herb Lycoris radiata, has been shown to suppress tumor activity in several human cancers. For example, with very low toxicity, LY could inhibit ovarian cancer proliferation and tumor neovascularization [31]. Additionally, LY was found to inhibit the JAK2/STAT3 pathway and exert anti-tumor effects in an osteosarcoma xenograft model [32]. It has also been reported that LY promotes autophagy and apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inactivating the TCRP1/Akt/mTOR axis [33]. Furthermore, LY appears to block the Src/FAK-involved pathways implicated in tumor cell metastasis in breast cancer [34]. Moreover, colorectal carcinoma animal models have demonstrated that LY enhanced vemurafenib’s tumor-suppressive effects [36]. Herein, we discovered that LY inhibited ICC cell proliferation by regulating the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway based on RNA-seq analysis. Previous research has linked alterations in cholesterol biosynthesis to tumorigenic processes, and cholesterol is required for cell proliferation, differentiation, and membrane formation [6, 44].

The cholesterol synthesis process is divided into three stages, each with multiple rate-limiting enzymes critically involved in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway [45]. The first stage involves mevalonate (MVA) production, in which HMGCS1 is the primary rate-limiting enzyme, converting HMG-CoA into mevalonate [46]; the second stage is squalene synthesis, which involves FDFT1, a key enzyme that facilitates squalene production via the dimerization of two farnesyl diphosphate molecules in a two-step process [47]; and the final phase is cholesterol production, in which SQLE is the primary rate-limiting enzyme, catalyzing the initial oxygenation step in the cholesterol biosynthesis process [48]. One of the key strategies in anti-tumor research is targeting rate-limiting enzymes involved in the cholesterol synthesis pathway in tumor cells [44]. Our study identified SQLE and FDFT1 as critical downstream targets of LY in ICC cells. Notably, LY exerts dual regulation at both transcriptional and post-translational levels, as demonstrated by the coordinated downregulation of SQLE/FDFT1 expression and LY’s direct binding to their catalytic domains. This dual mechanism likely disrupts both gene transcription and protein stability, providing a comprehensive blockade of cholesterol biosynthesis pathways essential for tumor cell proliferation. In clinical ICC specimens and cell lines, SQLE and FDFT1 are significantly upregulated, with their expression levels positively correlated, indicating their coordinated role in ICC pathogenesis. Functional studies show that inhibition of either SQLE or FDFT1 suppresses ICC cell proliferation and colony formation, highlighting their essential roles in maintaining tumor cell viability. Mechanistically, FDFT1 depletion primarily disrupts squalene synthesis in the cholesterol pathway, while SQLE knockdown triggers broader reprogramming of oncogenic signaling networks, including stress and proliferative pathways. RNA-seq analysis identifies PTPN11 as a potential downstream target of SQLE, linking cholesterol metabolism to nuclear signaling. Notably, our mechanistic experiments revealed a specific role for SQLE in regulating PTPN11 subcellular localization. SQLE knockdown or LY treatment caused a marked reduction in nuclear PTPN11 levels that exceeded the decline in total protein expression, suggesting impaired nuclear translocation rather than global protein downregulation. This establishes SQLE as a critical regulator of PTPN11 subcellular trafficking in ICC progression.

PTPN11 is an oncogene in various human cancers, with its encoded protein, SHP2, regulating multiple cancer-related processes, including cell growth and proliferation, invasion and metastasis, the tumor microenvironment, and immune response [49]. According to research, SHP2 mechanistically promotes the Ras/ERK1/2, PI3K/AKT, JAK/STAT, JNK, and NF-κB signaling pathways [50, 51]. Previous research has demonstrated that the SHP2 function is location dependent; cytoplasmic SHP2 regulates cell growth and development, whereas nuclear-localized SHP2 regulates gene transcription [37]. According to other studies, SHP2 is more concentrated and more distributed in the cytoplasm of high-density cells and the nucleus of low-density cells, respectively [52]. The SHP2-YAP1 interaction is primarily responsible for the cell density-dependent subcellular localization of SHP2. Dephosphorylated YAP/TAZ stimulates the SHP2 nuclear accumulation, which enhances parafibrin tyrosine dephosphorylation and activates downstream genes in the Wnt signaling pathway [38]. Furthermore, SHP2 was found to be a PD-1 downstream effector molecule that facilitates immune evasion by sending T-cell inhibitory signals [53]. These findings suggest that PTPN11 is critically involved in cancer development, highlighting its importance as a high-profile target for cancer treatment in recent years. Herein, we found that PTPN11 is highly expressed in ICC cells and patient tissues. We also found a strong correlation between PTPN11 and SQLE expressions. Importantly, the preferential reduction in nuclear PTPN11 following SQLE inhibition, observed in both loss-of-function and drug-treatment models, indicates that SQLE modulates PTPN11’s nuclear accumulation, likely via regulation of trafficking machinery. This is further supported by molecular docking studies showing direct binding between LY and SQLE, establishing a mechanistic link between LY’s action and PTPN11 localization.

Compared to monotherapy, combined chemotherapy has demonstrated higher efficacy in cancer treatment and has been widely used for decades [54]. Including natural compounds in combined regimens for cancer prevention or treatment is appealing as it offers the potential for lower systemic toxicity and greater efficacy [55]. Several studies have reported that combining additional compounds with chemotherapy medications can lower the required concentration while increasing tumor treatment effectiveness, and that combination therapy is an effective strategy for overcoming tumor resistance [56–58]. Here, we investigated the synergistic effect of LY with five chemotherapeutic drugs, including first-line agents for ICC treatment. Our results showed that the LY + GEM combination therapy exerted the greatest anti-ICC effect. We also evaluated the anti-tumor potential of the LY + GEM combination therapy in various tumors, including NSCLC, glioma, SCLC, LIHC, PDAC, and COAD cells. Remarkably, we observed reduced SQLE and FDFT1 protein expressions in all the tested tumor cell lines. These findings imply that the synergistic anti-tumor effect of the LY + GEM combination therapy may be due to SQLE and FDFT1 down-regulation.

While our current findings establish the dual regulatory framework of LY on SQLE/FDFT1, the upstream signaling pathways mediating transcriptional repression (e.g., specific transcription factors or epigenetic modifiers) and the precise molecular details of LY-protein interactions (e.g., binding affinity and degradation pathways) remain to be fully elucidated. These mechanisms will be critical focus areas in our future studies to further refine the understanding of LY’s anti-tumor mechanism.

In conclusion, our study not only identifies LY as a novel inhibitor of cholesterol biosynthesis in ICC but also uncovers SQLE-dependent regulation of PTPN11 nuclear translocation as a critical mechanistic node. The differential impact on nuclear versus cytoplasmic PTPN11 levels highlights the importance of subcellular localization in oncogenic signaling, providing a robust rationale for targeting this axis in ICC therapy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- ICC

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- LY

Lycorine Hydrochloride

- CHOL

Cholangiocarcinoma

- GEM

Gemcitabine

- SR

Survival rate

- OS

Overall survival

- FDFT1

Farnesyl-Diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1

- SQLE

Squalene epoxidase

- PTPN11

Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 11

- CCK8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- μM

μmol/L

- WB

Western blotting

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GTEx

Genotype-Tissue Expression database

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- shRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

- MVA

Mevalonate

- DMSO

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- DEGs

Differently expressed genes

Author contributions

Fengyun Zhao designed the study, collected samples, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Shuxian Peng performed the experiments, analyzed the data. Liming Zou, Mingtian Zhong and Yanni Huang performed the experiments. Ping Wang and Mingfang Ji participated in RNA-seq data analysis and data interpretation. Xiaodong Ma and Fugui Li designed and supervised the study, provided reagents, provided their expertise in the analysis of the data, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Authorship order among the co-first authors was dependent on their relative contributions.

Funding

This study was supported by the grants from Zhongshan Social Welfare Science and Technology Research Project (No. 2022B3001), Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (No. 2024A03J1156).

Data availability

All raw and processed sequencing data generated in this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE240746. The TCGA publicly available data used in this study are available in the Xena database (https://xenabrowser.net/). Other data and resources generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The protocol and any procedures involving the care and use of animals in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhongshan City People’s Hospital. All the paraffin-embedded tissues of patients used in this study were obtained by informed patient consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiaodong Ma, Email: maxiaodong@m.scnu.edu.cn.

Fugui Li, Email: leef2002@126.com.

References

- 1.Moris D, Palta M, Kim C, Allen PJ, Morse MA, Lidsky ME. Advances in the treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an overview of the current and future therapeutic landscape for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:198–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilyas SI, Affo S, Goyal L, Lamarca A, Sapisochin G, Yang JD, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma - novel biological insights and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:470–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley RK, Bridgewater J, Gores GJ, Zhu AX. Systemic therapies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72:353–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bian X, Liu R, Meng Y, Xing D, Xu D, Lu Z. Lipid metabolism and cancer. J Exp Med 218 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Huang B, Song BL, Xu C. Cholesterol metabolism in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Metab. 2020;2:132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H, Zhou S, Tang Q, Xia H, Bi F. Cholesterol metabolism: new functions and therapeutic approaches in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1874:188394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha NT, Lee CH. Roles of Farnesyl-Diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 in tumour and tumour microenvironments. Cells 9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zou Y, Zhang H, Bi F, Tang Q, Xu H. Targeting the key cholesterol biosynthesis enzyme squalene monooxygenasefor cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:938502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakae A, Kodama M, Okamoto T, Tokunaga M, Shimura H, Hashimoto K, et al. Ubiquitin specific peptidase 32 acts as an oncogene in epithelial ovarian cancer by deubiquitylating farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;552:120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang YF, Jan YH, Liu YP, Yang CJ, Su CY, Chang YC, et al. Squalene synthase induces tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 enrichment in lipid rafts to promote lung cancer metastasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:675–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuma Y, Matsui H, Koike H, Sekine Y, Shechter I, Ohtake N, et al. Role of squalene synthase in prostate cancer risk and the biological aggressiveness of human prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang H, Tang E, Chen Y, Liu H, Zhao Y, Lin M, et al. Squalene synthase predicts poor prognosis in stage I-III colon adenocarcinoma and synergizes squalene epoxidase to promote tumor progression. Cancer Sci. 2022;113:971–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weng ML, Chen WK, Chen XY, Lu H, Sun ZR, Yu Q, et al. Fasting inhibits aerobic Glycolysis and proliferation in colorectal cancer via the Fdft1-mediated AKT/mTOR/HIF1alpha pathway suppression. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Brown DN, Caffa I, Cirmena G, Piras D, Garuti A, Gallo M, et al. Squalene epoxidase is a Bona Fide oncogene by amplification with clinical relevance in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin Y, Zhang Y, Tang Q, Jin L, Chen Y. SQLE induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by regulating of miR-133b in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2017;49:138–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z, Wu W, Jiao H, Chen Y, Ji X, Cao J, et al. Squalene epoxidase promotes hepatocellular carcinoma development by activating STRAP transcription and TGF-beta/SMAD signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2023;180:1562–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You W, Ke J, Chen Y, Cai Z, Huang ZP, Hu P, et al. SQLE, A key enzyme in cholesterol metabolism, correlates with tumor immune infiltration and immunotherapy outcome of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:864244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S, Dong L, Ma L, Yang S, Zheng Y, Zhang J, et al. SQLE facilitates the pancreatic cancer progression via the lncRNA-TTN-AS1/miR-133b/SQLE axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2022;26:3636–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao F, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Li X, Chen K, Long Y, et al. SQLE Inhibition suppresses the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and enhances its sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents in vitro. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:6613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo M, Qiao Y, Lu Y, Zhu L, Zheng L. Squalene epoxidase facilitates cervical cancer progression by modulating tumor protein p53 signaling pathway. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49:1383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalogirou C, Linxweiler J, Schmucker P, Snaebjornsson MT, Schmitz W, Wach S, et al. MiR-205-driven downregulation of cholesterol biosynthesis through SQLE-inhibition identifies therapeutic vulnerability in aggressive prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He L, Li H, Pan C, Hua Y, Peng J, Zhou Z, et al. Squalene epoxidase promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation through accumulating calcitriol and activating CYP24A1-mediated MAPK signaling. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:726–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ge H, Zhao Y, Shi X, Tan Z, Chi X, He M, et al. Squalene epoxidase promotes the proliferation and metastasis of lung squamous cell carcinoma cells though extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10:428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu LP, Huang W, Wang X, Xu C, Qin WT, Li D, et al. Terbinafine prevents colorectal cancer growth by inducing dNTP starvation and reducing immune suppression. Mol Ther. 2022;30:3284–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi L, Huang P, Zou X, Guo L, Gu Y, Wen C, et al. Integrative stemness characteristics associated with prognosis and the immune microenvironment in esophageal cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2020;161:105144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malta TM, Sokolov A, Gentles AJ, Burzykowski T, Poisson L, Weinstein JN, et al. Machine learning identifies stemness features associated with oncogenic dedifferentiation. Cell. 2018;173:338–54. e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang L, Liu X, Sui Y, Ma Z, Feng X, Wang F et al. Lycorine Hydrochloride Inhibits the Virulence Traits of Candida albicans. Biomed Res Int 2019, 1851740 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Liu J, Yang Y, Xu Y, Ma C, Qin C, Zhang L. Lycorine reduces mortality of human enterovirus 71-infected mice by inhibiting virus replication. Virol J. 2011;8:483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang J, Zhang Y, Cao X, Fan J, Li G, Wang Q, et al. Lycorine inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 up-regulation in RAW264.7 cells through suppressing P38 and stats activation and increases the survival rate of mice after LPS challenge. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;12:249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Z, Yu D, Fu S, Zhang G, Pan Y, Bao M, et al. Lycorine hydrochloride selectively inhibits human ovarian cancer cell proliferation and tumor neovascularization with very low toxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2013;218:174–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu H, Wang S, Shi D, Zhong B, Huang X, Shi C, et al. Lycorine exerts antitumor activity against osteosarcoma cells in vitro and in vivo xenograft model through the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:5377–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu H, Qiu Y, Pang X, Li J, Wu S, Yin S, et al. Lycorine promotes autophagy and apoptosis via TCRP1/Akt/mTOR Axis inactivation in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:2711–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji Y, Yu M, Qi Z, Cui D, Xin G, Wang B, et al. Study on apoptosis effect of human breast cancer cell MCF-7 induced by Lycorine hydrochloride via death receptor pathway. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25:633–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu R, Cao Z, Tu J, Pan Y, Shang B, Zhang G, et al. Lycorine hydrochloride inhibits metastatic melanoma cell-dominant vasculogenic mimicry. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:630–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu M, Yu Z, Mei P, Li J, Luo D, Zhang H, et al. Lycorine induces autophagy-associated apoptosis by targeting MEK2 and enhances Vemurafenib activity in colorectal cancer. Aging. 2020;12:138–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsutsumi R, Masoudi M, Takahashi A, Fujii Y, Hayashi T, Kikuchi I, et al. YAP and TAZ, Hippo signaling targets, act as a rheostat for nuclear SHP2 function. Dev Cell. 2013;26:658–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K. Parafibromin/Hyrax activates wnt/wg target gene transcription by direct association with beta-catenin/Armadillo. Cell. 2006;125:327–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rizvi S, Khan SA, Hallemeier CL, Kelley RK, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma - evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:95–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar A, Jaitak V. Natural products as multidrug resistance modulators in cancer. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;176:268–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ali Abdalla YO, Subramaniam B, Nyamathulla S, Shamsuddin N, Arshad NM, Mun KS et al. Natural Products for Cancer Therapy: A Review of Their Mechanism of Actions and Toxicity in the Past Decade. J Trop Med 2022, 5794350 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Mondal A, Gandhi A, Fimognari C, Atanasov AG, Bishayee A. Alkaloids for cancer prevention and therapy: current progress and future perspectives. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;858:172472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang M, Lu JJ, Ding J. Natural products in Cancer therapy: past, present and future. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2021;11:5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feltrin S, Ravera F, Traversone N, Ferrando L, Bedognetti D, Ballestrero A, et al. Sterol synthesis pathway Inhibition as a target for cancer treatment. Cancer Lett. 2020;493:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang Y, Besch-Williford C, Aebi JD, Mafuvadze B, Cook MT, Zou X, et al. Cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitors as potent novel anti-cancer agents: suppression of hormone-dependent breast cancer by the oxidosqualene cyclase inhibitor RO 48-8071. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang IH, Huang TT, Chen JL, Chu LW, Ping YH, Hsu KW et al. Mevalonate pathway enzyme HMGCS1 contributes to gastric Cancer progression. Cancers (Basel) 12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Tuzmen S, Hostetter G, Watanabe A, Ekmekci C, Carrigan PE, Shechter I, et al. Characterization of Farnesyl diphosphate Farnesyl transferase 1 (FDFT1) expression in cancer. Per Med. 2019;16:51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belter A, Skupinska M, Giel-Pietraszuk M, Grabarkiewicz T, Rychlewski L, Barciszewski J. Squalene monooxygenase - a target for hypercholesterolemic therapy. Biol Chem. 2011;392:1053–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Z, Wang M, Ge Y, Chen XP, Xu Z, Sun Y, et al. Tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 inhibitors in tumor-targeted therapies. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:13–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan X, Bu H, Zhou J, Yang CY, Zhang H. Recent advances of SHP2 inhibitors in Cancer therapy: current development and clinical application. J Med Chem. 2020;63:11368–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grossmann KS, Rosario M, Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W. The tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 in development and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;106:53–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi A, Tsutsumi R, Kikuchi I, Obuse C, Saito Y, Seidi A, et al. SHP2 tyrosine phosphatase converts parafibromin/Cdc73 from a tumor suppressor to an oncogenic driver. Mol Cell. 2011;43:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu X, Hou B, Fulzele A, Masubuchi T, Zhao Y, Wu Z et al. PD-1 and BTLA regulate T cell signaling differentially and only partially through SHP1 and SHP2. J Cell Biol 219 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Sauter ER. Cancer prevention and treatment using combination therapy with natural compounds. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13:265–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang W, Li S, Li C, Li T, Huang Y. Remodeling tumor microenvironment with natural products to overcome drug resistance. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1051998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ulrich-Merzenich G, Panek D, Zeitler H, Wagner H, Vetter H. New perspectives for synergy research with the omic-technologies. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erkisa M, Sariman M, Geyik OG, Geyik C, Stanojkovic T, Ulukaya E. Natural products as a promising therapeutic strategy to target Cancer stem cells. Curr Med Chem. 2022;29:741–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang C, Mai Z, Liu C, Yin S, Cai Y, Xia C. Natural products in preventing tumor drug resistance and related signaling pathways. Molecules 27 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw and processed sequencing data generated in this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE240746. The TCGA publicly available data used in this study are available in the Xena database (https://xenabrowser.net/). Other data and resources generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.