Abstract

Quality assurance in behavior planning may best be accomplished when quality measures match governing policies that closely parallel best practice standards. This article provides an example of state government creating practice guidelines for focused behavioral services delivered in a home and community-based waiver system. We provide an overview of existing quality assurance instruments for behavior plans and share a unique quality review tool with several automated features designed to assess adherence to these practice guidelines. Considerations are offered for others with interest in policy to practice alignment, along with suggestions on how behavior analysts can successfully participate in policy making and quality assurance.

Keywords: Quality assurance in functional behavior assessment and behavior support plans, Behavior plan scoring tool, Regulation of behavior analysis, Policy development

Background for the Alignment of Policy with Practice

The United States and the Commonwealth of Virginia entered into a settlement agreement in 2012 stemming from the U.S. Department of Justice’s investigations into Virginia’s training centers and associated filing alleging violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (United States of America v. Commonwealth of Virginia, and Peggy Wood et al. v. Robert McDonnell et al., 2012). The settlement agreement, as well as the subsequent joint filing of compliance indicators, served to outline a set of benchmark expectations for the Commonwealth’s community-based services for developmentally disabled citizens.1 These include but are not limited to case management, nursing, crisis, risk management, and germane to this article, behavioral services. The Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services (DBHDS) oversees such community-based services and acts as the Commonwealth’s lead agency in achieving the requirements of the settlement agreement.

Therapeutic consultation is a home and community-based (HCBS) waiver service in Virginia that provides for an array of therapies (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, n.d.; Therapeutic Consultation Service, 2021). These include focused behavioral services via a functional behavior assessment (FBA), as well as behavior support planning (BSP), direct therapy, and supporter training and consultation (for information on focused versus comprehensive behavior analysis approaches, see Council of Autism Service Providers [2020]). HCBS 1915(c) waivers are developed by states under federal guidelines to provide community-based support and services for targeted groups of individuals, as opposed to receiving services in an institutional setting. Such state operated waiver programs must be less costly than providing institutional services, protect the health and welfare of waiver recipients, outline provider standards in serving the needs of the waiver population, and adhere to person-centered and individually tailored care plans (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, n.d.).

In the joint filing of compliance indicators, the Commonwealth was required to update developmental disability (DD) waiver regulations governing the therapeutic behavioral consultation service to outline expectations for behavioral programming and the structure of behavior plans (Therapeutic Consultation Service, 2021; United States of America v. Commonwealth of Virginia, and Peggy Wood et al., 2020). This led to the development of associated practice guidelines on the minimum elements of an adequately designed behavioral program (Virginia Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services & Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services, 2021). Such robust expectations also resulted in the creation of a quality assurance review tool to determine adherence to these requirements.2

In the discussion that follows, we outline the development of regulations and guidance for behavioral services in the DD waiver system in Virginia and provide a brief on research on quality assurance and quality review tools for FBA and BSP. Our discussion details the rationale and process surrounding the creation of an automated instrument that can be used to determine adherence to regulatory expectations for problem-focused behavioral programming. We suggest this instrument may be useful for behavior analysts interested in quality assurance and can also be used as a self-monitoring tool for behavior analysts for FBAs and BSPs that are generated on their own or within their agencies. We offer considerations for behavior analysts interested in aligning policy with practice and conclude with suggestions regarding how the field can provide quality assurance reviews to ensure that behavioral programming meets accepted practice standards.

Development of Regulations and Practice Guidelines in Virginia

In 2016, the Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS) and DBHDS initiated significant redesign to Virginia’s DD waiver system to include therapeutic consultation. As part of these redesign efforts, DBHDS set out to develop a draft list of behavior support plan content areas, which was led by the first and second authors who are both BCBAs with 30 years of combined experience in FBA, BSP, and family and practitioner training across an array of environments. Using both professional experiences and the extant literature, a draft list of behavior support plan content areas was cultivated and distributed to the respective leadership of the Virginia Association for Behavior Analysis and the Virginia Positive Behavior Support project at Virginia Commonwealth University for feedback. After this feedback, the draft list was used to shape the proposed regulatory changes. The stages of regulatory action included public comment periods, with comments made by members of the behavioral community offering recommendations for the structure of FBAs and BSPs that generally aligned with the proposed regulations. Public comment was considered and used to shape the behavior support plan content areas and other service requirements (e.g., producing training evidence for certain authorization types) that became effective in March 2021. The finalized waiver regulations addressed the settlement agreement compliance indicator requiring waiver regulations to include expectations for behavioral programming and associated content areas for behavior plans (Virginia Registrar of Regulations, 2019; United States of America v. Commonwealth of Virginia, and Peggy Wood et al., 2020; Therapeutic Consultation Service, 2021).

Concurrent to the lengthy regulatory process of updating waiver regulations, the first and second authors commenced further review of literature and drafting of what became the “Department of Behavioral Health and Department of Medical Assistance Services Practice Guidelines for Behavior Support Plans” (henceforth referred to as “the practice guidelines”). The practice guidelines address compliance indicator requirements on the minimum elements of an adequate behavioral program. For example, the practice guidelines require that for behaviors targeted for decrease and increase, an operational definition, method of measurement, and examples/nonexamples for target behaviors are to be included in BSPs (Virginia Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services & Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services, 2021).

The steps required to create or update regulations and guidance can be a complex and protracted process and touch numerous facets of state government operations. Based on the type of action being undertaken, there can be multiple required public comment periods, the result of which may be used to modify the language of the proposed regulation or guidance (Virginia Regulatory Town Hall, n.d.). The practice guidelines became effective and were posted on the Virginia Regulatory Town Hall website in July 2021. As a result of the waiver regulations updates and practice guidelines development, documentation requirements and associated time limits for completion were specified for the first time for this service (e.g., requirement of a FBA, BSP, and plan for training to receive a second authorization). These stipulations helped to set the stage for the creation of a quality assurance instrument and review process.

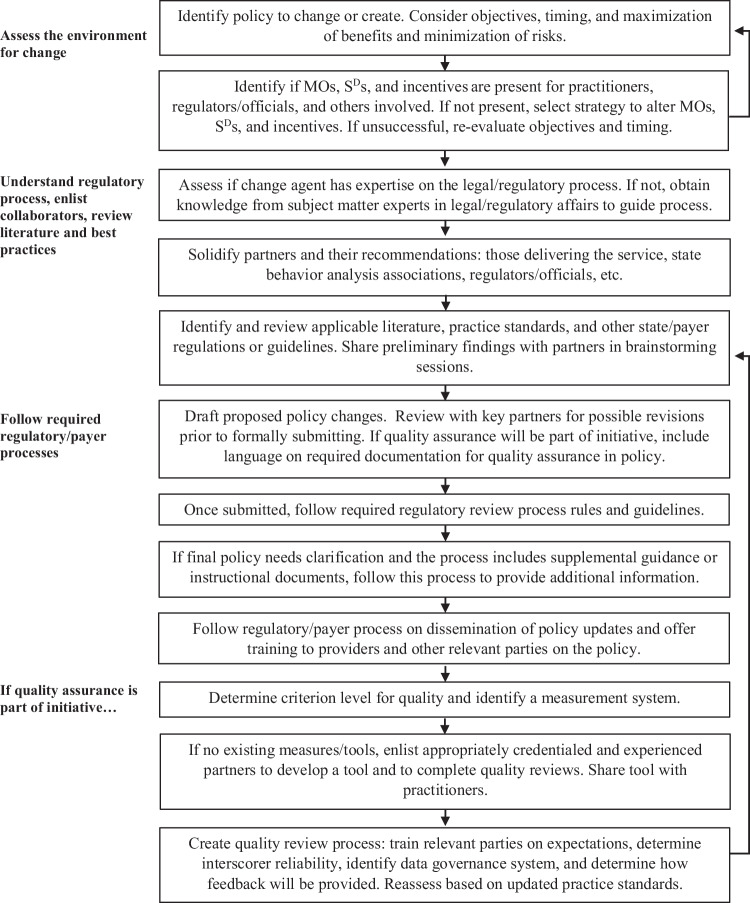

Figure 1 offers considerations for readers who may serve as a driving change agent or participate in the process of policy development for behavior analysis services, to include attention to sculpting the framework for a quality assurance process. These considerations serve as examples based on the experiences of the first two authors both during and in retrospect of the process of participating in policy updates. Readers must understand that processes may vary based on the nature of the policy change initiative and overarching legal, regulatory, and/or payer requirements.

Fig. 1.

Considerations for policy to practice alignment and initiating quality reviews

Creation of an Automated Scoring Quality Assurance Tool

We determined that a unique quality review tool was required to determine adherence, given the language in the compliance indicators requiring behavioral programming alignment to the recently formulated practice guidelines. Thus, the authors set out to create a mechanism to evaluate the level of adherence of FBAs, BSPs, and related service deliverables in comparison to the practice guidelines. The name Behavior Support Plan Adherence Review Instrument (BSPARI) was selected, with the functions and purposes of the instrument to be determining adherence (or lack thereof) to the practice guidelines and simultaneously providing an apparatus for feedback to authors of FBAs and BSPs. A Microsoft Excel workbook was used to create a rubric that incorporated the 12 core content areas in the practice guidelines, with an additional area on graphical displays and analysis to align with regulatory and general best practice expectations.

In formulating the BSPARI, the first two authors reviewed the minimum elements outlined in the practice guidelines and included these in the Microsoft Excel workbook to visually correspond to their related content area from the regulations. This was completed by reviewing the practice guidelines' language and then incorporating the relevant language as distinct line items on the BSPARI. In addition, regulatory content requiring graphed data was emphasized to include specifications for graphs for both behaviors targeted for increase and decrease, resulting in a total of 69 possible “minimum elements” across 13 content areas.

In conceptualizing future reviews of behavioral programming, it was posited that reviews would minimally have to be completed by a BCBA in good standing with at least 5 years postcertification and training in function-based behavior support plan development. Five years postcertification was suggested, because the reviewer would provide feedback on the results of the review to the plan author and would allow for substantial experience across a range of behaviors and populations. This cutoff has been used for consulting supervisors by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) and as a means to assess supervisorial strain as a ratio of newly certified behavior analysts to those with 5 or more years’ experience (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2023; Deochand et al., 2023). Although not intended to function as formal supervision to the plan author, we aligned this indication with the BACB’s Consulting Supervisor Requirements for New BCBAs Supervising Fieldwork (BACB, 2023), because we concluded that advanced practical experience would be needed to provide effective feedback to fellow clinicians.

In initial draft iterations of the BSPARI, several things became readily apparent: (1) not every content area and associated minimum element should have equal weight in determining overall adherence to the practice guidelines; (2) some sort of overall minimum score for acceptable adherence would need to be formulated; and (3) not all of the possible 69 minimum elements would be applicable for every behavioral program (e.g., history of previous behavioral services may not be known). To address these issues, a Scoring Instructions Guide and Feedback Process (henceforth “scoring instructions”) document was drafted. The scoring instructions list the required content areas and minimum elements for a behavioral program, provide definitions for each element, include weighted scores and permutations for each content area, and denote elements that may not be applicable to every behavioral program.

Scoring and Initial Reviews

In scoring the BSPARI, the reviewer would use the submitted service authorization documentation required by the regulations (FBA, BSP, etc.) to determine if the required minimum elements were present or absent, signifying presence and adequacy with a check mark (√) and absence (or deficiency) with an X. In some cases, a double check mark (√√) was used where additional resolution was needed to indicate the presence of an item across all instances, whereas a single check mark (√) indicated partial inclusion of the item but not across all instances in the plan. For example, if there were summary statements for all graphical displays present then it would receive a double check mark (√√) for the content area. If, however, this statement was present for some but not all graphs present, then a single check mark (√) would be used.

During initial reviews of behavioral programming, the first and second authors completed four independent reviews of the same behavioral programming, referenced the scoring instructions to manually score the BSPARI, and then compared scores to refine the BSPARI and its associated scoring logic through several initial draft iterations. Two clinicians with experience delivering therapeutic behavioral consultation services in Virginia were recruited to review the scoring instructions and minor adjustments to scoring logic were made based upon their critiques. The finalized BSPARI has 40 total weighted points available, with minimum adherence being set at 34 points (85% of possible weighted points achieved). Hence, any score from 34 to 40 points would be in adherence with the practice guidelines, and any score from 0 to 33 points would not be in adherence with the practice guidelines. The BSPARI, scoring instructions, and additional information on feedback, training, and fidelity processes can be obtained by contacting the first author or by visiting the following website: https://dbhds.virginia.gov/developmental-services/behavioral-services/.

Weighted Scoring Determinations

As an example of assigning weighted points to content areas and associated minimum elements most critical for plan success, 1 maximum point is available for basic demographic information, whereas 10 points are available for the FBA and hypothesized function(s). Essential elements were emphasized via scoring logic assignments. For example, tying a requirement for FBA methods beyond indirect assessment to the scoring logic such that if only indirect assessments were used, it would not be possible for the plan to reach minimum adherence levels to the practice guidelines. This scoring assignment was shaped by review of literature noting the limitations of indirect assessment methods in FBA (Dufrene et al., 2017; Lloyd et al, 2021). Other notable scoring logic assignments include incorporating a behavior skills training approach and weighting this approach at two out of three possible points in the “plan for training” section, as well as requiring a summary statement on graphs to foster visual analysis and decision making and assigning five points overall in this section.3 In addition, an equal score is provided for either simply listing out the activities sought out and enjoyed by the individual or completing a formalized or empirical preference assessment.4

In the “person centered information" section, the scoring links together the person’s communication modality, routines/current schedule, and information about reinforcers such that if any of these areas were absent, no points would be awarded in this section. Important emerging topics in the field, including cultural awareness and trauma informed care (see Deochand & Costello, 2022; Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022; Rajaraman et al., 2021; Sivaraman & Fahmie, 2020) were outlined within the practice guidelines, but it was recognized that this information may not be readily available or in some instances may not want to be discussed by the person receiving services.

Treatment objectives were not targeted within the practice guidelines, or tied into the scoring logic, as these are already required for services delivered through DD waiver services in Virginia (Virginia Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services, 2018). For those that are interested in adapting the BSPARI to or setting up quality assurance frameworks in other locations, we suggest determining if legal/regulatory requirements are already inclusive of treatment objectives in the overarching service system. If not, this is an area that should be considered in policy or otherwise baked into the quality review process.

Table 1 provides the broad content areas and minimum required elements of the practice guidelines and BSPARI and suggests supplemental elements that practitioners may want to consider in FBA and BSP. In addition to the references noted in Table 1, the “resources” tab on the BSPARI can be accessed for additional references.

Table 1.

BSPARI minimum required elements and additional elements for practitioner consideration in FBA and BSP

| BSP Content Area | Minimum Required Elements These elements are outlined in the Practice Guidelines and evaluated with the BSPARI |

Additional Elements for Consideration These elements are not outlined in the Practice Guidelines but are offered as additional considerations for practitioners completing FBA and BSP |

References Literature on key of elements to FBA/BSP that relate to the element; see “Resources” tab on BSPARI tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Individual’s name1 | Preferred pronouns and prefixes/suffixes or nickname | (Quigley et al., 2018)1 |

| Date of birth and/or age1 | Intended purpose for each medication’s prescription (especially those prescribed for a behavioral challenge) as well as dietary information/ restrictions/ allergies/ side-effects specified3 | (Leland & Stockwell, 2019)2 | |

| Gender identification2 | |||

| Medical/behavioral health diagnostic information | Medical rule out for referral when applicable4 and or additional referrals (speech/ psychiatric etc.)5 | (Li & Poling, 2018)3 | |

| Current living situation and location(s) where BSP is being implemented | (Bailey & Burch, 2020)4 | ||

| Medicaid/ Member ID | History of emergency involuntary institutionalization, law enforcement involvement, criminal behavior, drug use, etc.6 | (LaVigna et al., 2005)5 | |

| Medications3 | |||

| Legal status (in particular as it relates to ability to make own decisions and self-direct treatment, and who will consent to plan) | Contra-indicated medical conditions that could potentially impact behaviors of interest5 | ||

| Date of initial plan and dates of revisions (and nature of revisions) | Physical mobility/ level of independence in daily living functions specified6 | (Willis et al., 2011)6 | |

| Authoring clinician’s name/credentials/contact information1 | Supervising BCBA’s information and experience description working with specific challenging behavior(s) and client population | ||

| History & Rationale | Current and/or relevant historical info about this person and their life | Summaries of other psychological or psychiatric reports and/or previous treatment failures8 | (Rajaraman et al., 2021)7 |

| The reason and rationale for BSP/necessity for intervention6 | Ecological analysis of all settings the client is in, as well as environmental modifications influencing certain behaviors of interest6 | (Farmer & Floyd, 2016)8 | |

| Dangerous behavior: topographies, intensities, risks and/or negative outcomes | |||

| Risk and benefits related to prescribed behavioral programming4 | |||

| Known history of previous services and impact on behavior (if known) | |||

| Trauma history (if applicable)7 | |||

| Person Centered Information | Individual’s communication modality or modalities (e.g. expressive & receptive capabilities, method(s) of communication, etc.).9 | Includes other languages spoken and goals of the client and their verbal community (acculturation vs assimilation scales)5 | (Horner et al., 2000)9 |

| Routines/current schedule10 | Includes challenges to particular routines | (Hieneman, 2015)10 | |

| Individual and guardian’s participation10 | Includes short and long term life goals of the client and or caregivers | (Leaf et al., 2020)11 | |

| What activities are enjoyed and sought by the individual/preference assessment information/results11 | Self-care skills, domestic skills, academic skills, leisure skills, community skills5 | ||

| Individual’s strengths and positive contributions9 | Assessment of caregiver/ staff involvement | (McLaughlin & Carr, 2005)12 | |

| Particular aversions/dislikes9 | |||

| Who in the individual’s life is especially preferred12 | (Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022)13 | ||

| Other cultural/heritage considerations13 | |||

| Functional Behavior Assessment | The FBA incudes descriptive assessment and/or functional analysis14 | Risk assessment procedure or statement regarding suitability of assessment selected18 | (Dufrene et al., 2017)14 |

| The FBA methods used are described15 | Indicates the contribution of certain skill deficits in the occurrence of challenging behavior19 | (Cooper et al., 2020)15 | |

| FBA conducted in location where services are occurring | Validity assessment6/ check or statement of results of FBA | ||

| Setting events/motivating operations listed16 | Described within 4-term contingency | (Nosik & Carr, 2016)16 | |

| Antecedents15 | Setting events/motivating operations | (LeBlanc et al., 2020)17 | |

| Consequences15 | Discriminative stimuli & S-delta(s) | (Deochand et al., 2020)18 | |

| Data results and/or graphical displays1 | Antecedents | (Killu et al., 2006)19 | |

| FBA is current (since most recent Individual Services Plan meeting, or statement of clinician’s affirmation of the validity of FBA) | Consequences5 | ||

| Non-operant conditions that influence behavior (if applicable) 17 | |||

| Hypothesized functions | Hypothesized functions listed20 | Describe the context for idiosyncratic or synthesized functions if identified21 | (Positive Environments, Network of Trainers, 2021)20 |

| Functions match to typical operant functions for all behaviors20 | (Tiger & Effertz, 2021)21 | ||

| Behaviors targeted for decrease | Lists each behavior targeted for decrease15 | Plan for fading contrived punishers/aversives while minimizing prompting24 | (Williams & Vollmer, 2015)22 |

| Operational definition22 | |||

| Methods of measurement for each behavior23 | (LeBlanc et al., 2016)23 | ||

| Inclusion in definition of examples/nonexamples15 | (Vollmer et al., 1992)24 | ||

| Behaviors targeted for increase | Lists each behavior targeted for increase15 | Plan for fading contrived reinforcers while minimizing prompting24 | (McKenna et al., 2017)25 |

| Operational definition22 | |||

| Methods of measurement for each behavior23 | (Phillips et al., 2017)26 | ||

| Inclusion in definition of examples/nonexamples15 | |||

| Antecedent interventions | Tactics promote environment in which functionally equivalent replacement behaviors (FERB) acquisition will occur25 | Stimulus discrimination training procedures29 | (Rettig et al., 2019)27 |

| Tactics that address setting events and/or motivating operations (MOs)26 | Details on stimulus control transfer procedures30 | (Boyle et al., 2021)28 | |

| Tactics/de-escalation strategies that address immediate antecedents and/or precursors27 | |||

| Strategies that describe stimuli that should or should not be present28 | (Kodak et al., 2022)29 | ||

| Consequence interventions | Tactics incorporate a function-based treatment approach for challenging behavior31 | Reinforcement schedules, delays, or punishment schedule are specified and appropriate22 as well as criteria for new goals (short and long term)6 | (Cenghar et al., 2018)30 |

| Tactics use the least-restrictive intervention to be successful approach for challenging behavior 32 | Risk assessment procedure or statement regarding suitability of interventions selected4 | (Newcomb & Hagopian, 2018)31 | |

| Tactics minimize reinforcement for challenging behavior(s)33 | Cost benefit analysis for intervention and expected outcome gains4 | (Van Houten et al., 1988)32 | |

| Inclusion of preferences/reinforcers, schedule of Sr+/-, and/or expectations for learning environment/materials/teaching conditions to increase desired behavior(s)22 | Inclusion of generalization and maintenance strategies22 | (Vollmer et al., 2020)33 | |

| Safety & Crisis Guidelines | Safety gear outlined34 | Statement regarding anticipated weaknesses/ limitations of the behavior plan35 as well as a safety criterion for re-evaluation of assessment and procedures | (Oropeza et al., 2018)34 |

| Crisis protocol or where to obtain the protocol9 | |||

| Describes supports needed to ensure safety of person and others9 | Statement regarding how any implemented restrictions is to the benefit of the client36 | (Crates & Spicer, 2012)35 | |

| Describes topographies, intensities, & negative outcomes20 | |||

| If restraint or time out is included, notes debriefing procedures | (Phillips et al., 2010)36 | ||

| If restraint or time out is included, notes criteria for release or refers to provider policies and procedures | |||

| Plan for training | Outlines a plan for training staff, family, or other supporters that notes clinician obtaining and reviewing data37 | Simplified accessible “cheat sheet” for staff or caregiver implementation4 | (Becraft et al., 2023)37 |

| Plan incorporates a behavior skills training approach38 | Fidelity training comparison between covert and overt checks. Presentation of inter-observer agreement scores.39 | (Sun, 2022)38 | |

| Training record (or plan for training based on authorization type) is available in service authorization system related to recent review period | Treatment integrity is specified as to frequency of monitoring22 | (Pétursdóttir, 2017)39 | |

| Periodic service review (PSR) schedule for behavior plan is specified24 | |||

| Appropriate signatures | Plan is signed by individual or legal guardian1 | Behavior analyst signature present along with all previous authors of the behavior plan | (Ivory & Kern, 2022)40 |

| Signature for consent includes date | Consent is obtained prior to assessment, treatment, restrictive plans, and research.22 | ||

| Contact information for guardian or individual is present | Weekly or regular check-in with caregivers specified40 | ||

| If a restrictive component is included, updated consent is included and coincides with when restriction began11 | |||

| Graphical displays & analysis | Visual display (e.g. graphs) for each behavior targeted in the BSP, to include behavior for decrease and increase24 | Graphs are arranged by hypothesized function and those graphs that are interrelated are presented together | (Kubina et al., 2017)41 |

| Summary statement present for each graph | Summary statistics are presented in tables for relevant review agencies to review changes in the data | ||

| Graphs have indicators that demonstrate decision making and/or analysis is occurring (based on behavior trends and/or revision dates)41 | Graphs maintain aspect ratios for relevant comparisons | ||

| Graphs represent entire necessary review period (if any data is absent a reason why is included) | |||

| Graphs demonstrate that data review is occurring at least monthly if restraint or time out is included24 | Periodic progress report on goal achievement24 |

Note. There are other quality elements that can be included in FBA and inserted within a BSP. Additional considerations are also noted and are not inclusive of all possible elements available in the literature

Quality Assurance and Quality Review Tools

Although the desired content of both FBA and BSP are aptly detailed in the larger corpus of behavioral literature (see Cipani, 2018; Cooper et al., 2020; Horner et al., 2000; Quigley et al., 2018; Williams & Vollmer, 2015), there is limited research on quality assurance in FBA and BSP. Whereas studies on training packages for families or staff to improve assessment or treatment implementation are readily available in the research (see Lloveras et al., 2022; Monzalve & Horner, 2021; Nuta et al., 2021; Pétursdóttir, 2017; Sun, 2022; Thompson & MacNaul, 2023), there is less research that examines the improvement or quality of FBA or BSP as a function of training (Browning-Wright et al., 2007; Dutt et al., 2023; Wu, 2017). Studies examining the impact of regulatory, legal, or policy guidance changes on plan quality appear further limited. Thus, it remains unclear if such policy changes alone can result in substantive improvement in the quality of FBA and BSP (Phillips et al., 2010; Wardale et al., 2016). Lastly, examinations of policy requirements aligning to accepted practice standards are also finite. Analyses we reviewed were specific to the governing requirements of educational settings, as opposed to home and community-based settings (Collins & Zirkel, 2017; Killu et al., 2006). We suggest that a quality assurance structure can best be achieved when regulatory/payer requirements align with best practices in the field and when the method for determining quality (i.e., a quality review instrument) conforms to those requirements.

Quality Review Tools

There are only a handful of instruments that have been crafted to evaluate the quality of FBAs and BSPs. Each tool has areas of overlap and establishes FBA and BSP requirements from the literature, but some offer unique elements and rating criteria dependent on their specific client or setting location. Some tools do not contain a specific rating criterion and instead may be intended to guide plan development as opposed to reviewing the quality of a plan that has already been penned. A summary of these behavior support plan quality assurance evaluation tools (inclusive of the BSPARI), their content areas reviewed, criteria, and associated scoring information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of contents, criteria, and scoring for behavior plan quality assurance tools

| Quality review tool | Name of content areas | Number of criteria evaluated | Rating Criteria | Scoring method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment and Intervention Plan Evaluation Instrument (AIEI) |

Identifying Information Reason(s) for Referral Data Sources Background Information Functional Analysis/Functional Assessment Motivational Analysis Mediator Analysis Long-range Goals Short-range Behavioral Objectives Data Collection Supports Strategies Comments and Recommendations |

140 | No identified criteria cutoff, except 85% or higher for trainersa | Quantitative total percent score |

(LaVigna et al., 2005) (Crates & Spicer, 2012) |

| The Behavior Assessment Guide |

General Format Reason(s) for Referral Description of Assessment Activities Background Information Functional Analysis Motivation Analysis Mediator Analysis Recommended Support Plan Comments and Recommendations |

176b | No identified criteria cutoff | Quantitative total percent score and qualitative comments | (Willis et al., 2011) |

| Behavior Support Plan Adherence Review Instrument (BSPARI) |

Demographics History & rationale Person centered information FBA Hypothesized functions Behaviors targeted for decrease Behaviors targeted for increase Antecedent interventions Consequence interventions Safety & crisis guidelines Plan for training Signatures (consent) Graphical displays & analysis |

69 | Minimum 34 of 40 weighted points (85%) | Quantitative total percent weighted score, automated scoring via Microsoft Excel® | |

| The Behavior Support Plan Assessment Tool |

Description of challenging behavior Description of functional analysis Proactive strategies Reactive strategies Restrictive interventions Consultation Review |

10 | No identified criteria cutoff | Nominal scale (e.g., yes, partially, no) | (Phillips et al., 2010) |

| Behavior Support Plan Quality Evaluation Guide-II (BSPQE-II) |

Problem behavior Predictors/triggers of problem behavior Analysis of what supports the problem behavior is logically related to predictors Environmental structure is logically related to what supports the problem behavior Predictors related to function of behavior Function related to replacement behavior Teaching strategies specify teaching of FERB Reinforcers Reactive strategies Goals and objectives Team coordination and implementation Communication |

12 |

Weak (Fewer than 12 points or < 50%) Underdeveloped (13–16 points or 54%–67%) Good (17–21 points or 71%–88%) Superior (22–24 points or > 91%)c |

Quantitative weighted score | (Browning-Wright et al., 2007, 2013) |

| Individual Student Systems Evaluation Tool (ISSET): Version 3.0d |

Part I: Foundations Commitment Team Based Planning Student Identification Monitoring and Evaluation Part II: Targeted Interventions Implementation Evaluation and Monitoring Part III: Intensive Individualized Interventions Assessment Implementation Evaluation and Monitoring |

35 | Summary score for each part of ISSET, no identified criteria cutoff | Quantitative weighted score converted to percentage for each part | (Anderson et al., 2014) |

| Positive Behavior Supports Assessment Guide |

Focus and Functions Instructional and Preventive Positive and Equivalents Long Term and Comprehensive |

12 (four criterion sets with three descriptors each) |

Clear evidence Lacks evidence |

Qualitative scoring with comments | (Kroeger & Phillips, 2007) |

a Some trainers in a “train the trainer” model were selected based on their own behavior plans receiving 85% or higher on the AIEI; see Crates and Spicer (2012) for supplemental information

b Additional elements may be possible based on the number of behaviors targeted

c Percentages provided in this table are recalculated from Browning-Wright et al. (2007)

d The features of the ISSET specific to individualized FBA and BSP quality evaluations are outlined in Part III of the tool and contain a total of 10 evaluation areas; see Anderson et al. (2014) for additional context

The BSPARI offers several unique features that are not present in other quality review tools. The scoring for the BSPARI is automated based upon the reviewer’s scoring selections, which are bound by dropdown selections on the tool. To achieve automated scoring, nested IF statements (Microsoft, 2022) were used on the BSPARI based on the scoring logic set out in the scoring instructions. Therefore, point values for content areas are automatically assigned on the BSPARI based on the reviewer’s scoring selection for an element. Conditional formatting visually illustrates adherence (or lack thereof), with the scoring section for each content area and the overall score at the end of the instrument displaying a green or red background based on points received. A green background in the scoring area signifies adherence to the content area (or meeting the overall criterion on the entirety of the instrument) and a red background indicates lack of adherence.

The advent of automated scoring may improve scoring reliability and efficiency. It reduces the need for scorers to reference scoring instructions and mitigates the likelihood of scoring transfer errors. Such keystroke errors could provide erroneous scores that contrast with the scoring rules logic, such as awarding more points than are possible for a content area. Automated scoring tied into a simple color-coding schematic may translate to time saving benefits in the scoring process and in highlighting areas for the author of the FBA and BSP to focus on.

Another area of distinction for the BSPARI is the tool’s ability to highlight resources for clinicians on a separate worksheet contained within the same Microsoft Excel workbook. This “resources” tab marries with the results of the BSPARI scoring to provide hyperlinks to digital object identifier (DOI) references deriving from over 20 different journals, as well as additional book chapters, web resources, and regulatory requirements relevant to each content area and its associated minimum elements. The citations in the “resources” tab were gleaned both from keyword searches in journal databases (e.g., ProQuest), as well as from each author’s own professional knowledgebase. For example, a resource associated with the minimum element in the FBA section on data results and graphs provides the citation and DOI to Chok’s 2019 tutorial on creating functional analysis graphs.

Using conditional formatting in Microsoft Excel, any minimum element on the BSPARI scoring worksheet marked with an X (absent or inadequate) will highlight in red the corresponding reference(s) in the “resources” tab to provide related literature to access to improve the FBA and/or BSP content. The automated, color-coded scoring feature of the BSPARI bound to a weighted points system, along with the associated “resources” feature, are aspects of the instrument that the authors have not found in review of FBA and BSP quality assurance evaluation tools in the behavioral literature.

Discussion

Over the past several decades, behavioral literature has curated an extensive array of best-practice content on FBA and BSP. Unfortunately, there are few studies examining actual changes in behavior plan content as a function of regulatory or policy requirements and/or an associated quality assurance review process. The professional practice of applied behavior analysis (ABA) is going through historic growth and there is a heightened need to evaluate the quality of those services (Deochand et al., 2023). The first step in that process is to examine the written stipulations regarding those services and determine if they conform to established practice standards. We then need to ascertain if FBAs and BSPs are being developed with fidelity to such standards and create a framework for quality review to ensure a minimum level of adherence while striving for the gold standards of best practices. One strategy to increase transparency in the review process is to share review tools that offer scoring feedback, which offers authors the opportunity to self-monitor and revise their plans to ensure they meet the mandatory minimum standards.

The effort to successfully smelt legal, regulatory, or private payer requirements for therapeutic services with best practice for treatment requires the participation of skilled practitioners in that field. We suggest that behavior analysts are best equipped to shepherd the development of guidelines that governing bodies or payers fashion and adopt for behavior analysis services. In the experience of the first and second authors, the promulgation of new regulations for focused behavioral services required collaboration with several practitioner guilds that deliver the service, coordination with internal champions at a sizable state agency, and commitment to an extensive regulatory process. This process required multiple edits, modifications, and levels of approval needed to arrive at a final product. We propose that behavior analysts employed by payers or regulatory bodies that participate in similar undertakings must solicit input and communicate with key community partners while simultaneously adhering to internal policies and procedures regarding the regulatory process.

Regardless of whether a behavior analyst participates in change endeavors from within or outside of the payer/regulatory body, a potential obstacle to the alignment of regulatory language to best practice is communication with relevant parties who do not have experiences steeped in the procedures, tactics, and lexicon of ABA. Explaining those behavior analytic terms that can be confusing to partners outside of our verbal community, in a manner that can be understood, is crucial for success. Depending on the audience, the acceptability of our terms might vary (Banks et al., 2018; Friman, 2021), therefore we must do our best to communicate how our values drive us in our mission to effect change that benefits our clients. To secure buy-in that results in a final product that aligns with best practices, we must be able to dispel misrepresentations of our field and explain our terms and how they fit within other frameworks (Deochand & Costello, 2022).

Considerations

The compliance indicators for the settlement agreement between the United States and the Commonwealth of Virginia deliver expectations for a focused behavioral service in a HCBS waiver system and concurrently provide the foundation for quality assurance via a set of practice guidelines outlining minimum elements for FBA and BSP. This has both necessitated and provided an opportunity for a solution-related tool such as the BSPARI, where an automated weighted scoring system and resource generator can be used by a seasoned reviewer to determine quality and outline applicable literature. It serves as a means of sharing information, scoring behavior plans, and minimizes human errors from incorrect tallying of scores.

The benefits of an automated scoring tool may also produce a risk of granular elements that contributed to score deficiencies being overlooked in a feedback session with a plan author. For example, a reviewer may be less likely to point out observed deficiencies to a plan author as a function of the reviewer not hand-scoring the content areas and tallying the final score. This can be mitigated in several ways, including by having salient stimulus properties (color-coding) on the tool that informs the reviewer and plan author if all points were achieved or not for each content area and for the overall criterion on the tool. An additional risk mitigation strategy may be having the reviewer provide written summary findings on areas found to be adequate and areas needing improvement to the plan author, along with providing a scored copy of the tool. The professional background and training of the reviewer using a tool like the BSPARI can affect the aperture by which they view the adequacy of a particular element, though inconsistencies in scoring can be mitigated via ongoing interscorer reviews across a team. Updates to the scoring instructions (and the instrument) may be needed based on findings from interscorer reviews to refine criteria and enhance reliability. At the time of this article, the BSPARI is being used for quality reviews in Virginia; however, this article does not present validity or reliability findings on the BSPARI.

Researchers have suggested that machine learning can enhance decision making and could be employed to determine functions of behavior (Turgeon & Lanovaz, 2020). As we look to the future, it is possible that artificial intelligence can be used by behavior analysts in the development of FBA and BSP, along with the quality review process for these documents. At present, we can lay the groundwork for such a future state by developing regulations and/or payer expectations in accordance with best practices and using quality review measures such as those reviewed in this article.

We do not suggest that a quality review tool alone can substitute for comprehensive peer review paired with ongoing supervision and professional development that can be offered through a mentor–mentee relationship. With that noted, in an era where our field is rapidly expanding and quality assurance is of high importance, tools that provide a method for quality evaluations concurrent to delivering resources to practitioners will help regulators and practitioners alike. We concur with previous commentary suggesting that data, tools, protocols, videos, and software should be made available open access, especially when it facilitates replication (Tincani & Travers, 2019). Our hope is that the BSPARI can be used by other behavior analysts with an interest in quality assurance of FBA and BSP, or even be custom-tailored by behavior analysts to the expectations of regulators of problem-focused behavior analysis services in other states. Behavior analysts that have interest in self-monitoring their own behavioral programming or that of colleagues (i.e., within-agency peer reviews) may also appreciate the structure and automation offered via the BSPARI.

A fundamental aim of this article is to advance the notion that behavior analysts must participate in efforts to align policy with practice for behavior analysis services. We further contend that quality assurance may have increased validity when quality review instruments align with rules or regulations that themselves are steeped in best practice. Future research is warranted to determine the impact of quality feedback reviews of FBA and BSP by funders or regulators of behavior analysis services on the overall fidelity of behavioral programming to governing regulations or guidelines.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bobbie Hansel-Union, Matthew Osborne, and Brian Phelps for their review and feedback on the BSPARI and its Scoring Instructions, and we also thank Kathryn duPree, Donald Fletcher, Patrick Heick, and Joseph Marafito for their feedback on the DBHDS/DMAS Practice Guidelines for Behavior Support Plans and initial BSPARI draft.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to present this information.

Data Availability

There is no associated data for this article. The referenced tool and instructions can be accessed by contacting the primary author or at https://dbhds.virginia.gov/developmental-services/behavioral-services/.

Declarations

Ethical Consent

No human subjects were used in this article.

Content

The authors alone are responsible for the content of the article. The content of this article does not express an official position of the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services, any other state agency in Virginia, or of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest or financial gain with the development of this article or associated tool.

Footnotes

This article incorporates identity-first language; see Botha et al. (2023) and Vivanti (2020) for conversations on person-first and identity-first language.

The associated provisions and related compliance indicators in the settlement agreement most specific to behavioral services are as follows: provision III.C.6.a.i-iii, compliance indicator filing references 7.14 through 7.20; provision V.B., compliance indicator filing reference 29.21.

Scoring possibilities in the graphing section consider presence/absence of graphs for challenging and desirable behaviors, completeness of data set to authorization period, visual analysis indicators (i.e., condition change lines), and a brief summary statement of treatment progress.

Given the various educational and professional pedigrees of practitioners that could deliver therapeutic behavioral services (behavior analysts, positive behavior support facilitators, psychologists, counselors, social workers), background training on empirically based preference assessments may vary. Thus, equal value was provided for minimally considering the putative reinforcers for the individual.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq. (1990).

- Anderson, C. M., Lewis-Palmer, T., Todd, A. W., Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., & Sampson, N. K. (2014). Individual student systems evaluation tool: Version 3.0. Educational & Community Supports, University of Oregon.

- Bailey, J., & Burch, M. (2020). Ethics for behavior analysts (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, B. M., Shriver, M. D., Chadwell, M. R., & Allen, K. D. (2018). An examination of behavioral treatment wording on acceptability and understanding. Behavioral Interventions,33(3), 260–270. 10.1002/bin.1521 [Google Scholar]

- Becraft, J. L., Cataldo, M. F., Yu-Lefler, H. F., Schenk, Y. A., Edelstein, M. L., & Kurtz, P. F. (2023). Correspondence between data provided by parents and trained observers about challenging behavior. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice,23(4), 254–274. 10.1037/bar0000276 [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2023). Consulting supervisor requirements for new BCBAs supervising fieldwork.https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Consultation-Supervisor-Requirements-and-Documentation_230203-a.pdf

- Botha, M., Hanlon, J., & Williams, G. L. (2023). Does language matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: A response to Vivanti. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders,53, 870–878. 10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, M. A., Bacon, M. T., Carton, S. M., Augustine, J. T., Janota, T. A., Curtis, K. S., Forck, K. L., & Gaskill, L. A. (2021). Comparison of naturalistic and arbitrary discriminative stimuli during schedule thinning following functional communication training. Behavioral Interventions,36, 3–20. 10.1002/bin.1759 [Google Scholar]

- Browning-Wright, D., Mayer, R. G., Cook, C. R., Crews, D. S., Kraemer, B. R., & Gale, B. (2007). A preliminary study on the effects of training using Behavior Support Plan Quality Evaluation Guide (BSP-QE) to improve positive behavioral support plans. Education & Treatment of Children,30, 89–106. 10.1353/etc.2007.0017 [Google Scholar]

- Browning-Wright, D., Mayer, G. R., & Saren, D. (2013). Behavior intervention plan quality evaluation scoring guide II. Positive Environments, Network of Trainers, CA.

- Cenghar, M., Budd, A., Farrell, N., & Feinup, D. M. (2018). A review of prompt-fading procedures: Implications for effective and efficient skills acquisition. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities,30, 155–173. 10.1007/s10882-017-9575-8 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (n.d.). Home & Community Based Services 1915(c). Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/home-community-based-services/home-community-based-services-authorities/home-community-based-services-1915c/index.html

- Chok, J. T. (2019). Creating functional analysis graphs using Microsoft Excel for PCs. Behavior Analysis in Practice,12(1), 265–292. 10.1007/s40617-018-0258-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipani, E. (2018). Functional behavior assessment, diagnosis, and treatment: A complete system for education and mental health settings (3rd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L. W., & Zirkel, P. A. (2017). Functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans: Legal requirements and professional recommendations. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions,19(3), 180–190. 10.1177/1098300716682201 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Functional behavior assessment. In Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (Eds.), Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed., pp. 627–653). Pearson.

- Council of Autism Service Providers. (2020). Applied behavior analysis treatment of autism spectrum disorder: Practice guidelines for healthcare funders and managers (2nd ed.). www.casproviders.org

- Crates, N., & Spicer, M. (2012). Developing behavioural training services to meet defined standards within an Australian statewide disability service system and the associated client outcomes. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability,37, 196–208. 10.3109/13668250.2012.703318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deochand, N., & Costello, M. S. (2022). Building a social justice framework for cultural and linguistic diversity in ABA. Behavior Analysis in Practice,15, 893–908. 10.1007/s40617-021-00659-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deochand, N., Eldridge, R., & Peterson, S. M. (2020). Toward the development of a functional analysis risk assessment decision tool. Behavior Analysis in Practice,13, 978–990. 10.1007/s40617-020-00433-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deochand, N., Lanovaz, M. J., & Costello, M. S. (2023). Assessing Growth of BACB Certificants (1999–2019). Perspectives on Behavior Science, 1–32. 10.1007/s40614-023-00370-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dufrene, B. A., Kazmerski, J. S., & Labrot, Z. (2017). The current status of indirect functional assessment instruments. Psychology in the Schools,54(4), 331–350. 10.1002/pits.22006 [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, A., Cheng, A., TzeAng, B., & Nair, R. (2023). A pragmatic trial evaluating the effectiveness of web versus live training in functional behavior assessment and interventions among special educators. Behavioral Interventions,38(3), 569–589. 10.1002/bin.1933 [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, R. L., & Floyd, R. G. (2016). An evidence-driven, solution-focused approach to functional behavior assessment report writing. Psychology in the Schools,53, 1018–1031. 10.1002/pits.21972 [Google Scholar]

- Friman, P. C. (2021). There is no such thing as a bad boy: The circumstances view of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,54(2), 636–653. 10.1002/jaba.816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieneman, M. (2015). Positive behavior support for individuals with behavior challenges. Behavior Analysis in Practice,8, 101–108. 10.1007/s40617-015-0051-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., Todd, A. W., & Lewis-Palmer, T. (2000). Elements of behavior support plans: A technical brief. Exceptionality,8(3), 205–215. 10.1207/S15327035EX0803_6 [Google Scholar]

- Ivory, K. P., & Kern, L. K. (2022). Assessing parent implementation of behavior support strategies and self-monitoring to enhance maintenance. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions,24(1), 58–68. 10.1177/10983007211042106 [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Gomez, C., & Beaulieu, L. (2022). Cultural responsiveness in applied behavior analysis: Research and practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,55, 650–673. 10.1002/jaba.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killu, K., Weber, K. P., Derby, K. M., & Barretto, A. (2006). Behavior intervention planning and implementation of positive behavioral support plans: An examination of states’ adherence to standards for practice. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions,8, 195–200. 10.1177/10983007060080040201 [Google Scholar]

- Kodak, T., Bergmann, S., Cordeiro, M. C., Bamond, M., Isenhower, R. W., & Fiske, K. E. (2022). Replication of a skills assessment for auditory-visual conditional discrimination training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,55(2), 622–638. 10.1002/jaba.909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger, S. D., & Phillips, L. J. (2007). Positive behavior support assessment guide: Creating student-centered behavior plans. Assessment for Effective Intervention,32, 100–112. 10.1177/15345084070320020101 [Google Scholar]

- Kubina, R. M., Kostewicz, D. E., Brennan, K. M., & King, S. A. (2017). A critical review of line graphs in behavior analytic journals. Educational Psychology Review,29(3), 583–598. 10.1007/s10648-015-9339-x [Google Scholar]

- LaVigna, G. W., Christian, L., & Willis, T. J. (2005). Developing behavioural services to meet defined standards within a national system of specialist education services. Pediatric Rehabilitation,8, 144–155. 10.1080/13638490400024036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, J. B., Milne, C., Aljohani, W. A., Ferguson, J. L., Cihon, J. H., Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., McEachin, J., & Leaf, R. (2020). Training change agents how to implement formal preference assessments: A review of the literature. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities,32, 41–56. 10.1007/s10882-019-09668-2 [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, L. A., Raetz, P. B., Sellers, T. P., & Carr, J. E. (2016). A proposed model for selecting measurement procedures for the assessment and treatment of problem behavior. Behavior Analysis in Practice,9(1), 77–83. 10.1007/s40617-015-0063-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, L. A., Lerman, D. C., & Normand, M. P. (2020). Behavior analytic contributions to public health and telehealth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,53(3), 1208–1218. 10.1002/jaba.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leland, W., & Stockwell, A. (2019). A self-assessment tool for cultivating affirming practices with transgender and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) clients, supervisees, students, and colleagues. Behavior Analysis in Practice,12(4), 816–825. 10.1007/s40617-019-00375-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, A., & Poling, A. (2018). Board certified behavior analysts and psychotropic medications: Slipshod training, inconsistent involvement, and reason for hope. Behavior Analysis in Practice,11(4), 350–357. 10.1007/s40617-018-0237-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloveras, L. A., Tate, S. A., Vollmer, T. R., King, M., Jones, H., & Peters, K. P. (2022). Training behavior analysts to conduct functional analyses using a remote group behavioral skills training package. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,55(1), 290–304. 10.1002/jaba.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, B. P., Torelli, J. N., & Pollack, M. S. (2021). Practitioner perspectives on hypothesis testing strategies in the context of functional behavior assessment. Journal of Behavioral Education,30, 417–443. 10.1007/s10864-020-09384-4 [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, J. W., Flower, A., Falcomata, T., & Adamson, R. M. (2017). Function based replacement behavior interventions for students with challenging behavior. Behavioral Interventions,32, 379–398. 10.1002/bin.1484 [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, D. M., & Carr, E. G. (2005). Quality of rapport as a setting event for problem behavior: Assessment and intervention. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions,7(2), 68–91. 10.1177/10983007050070020401 [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft. (2022). IF function.https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/if-function-69aed7c9-4e8a-4755-a9bc-aa8bbff73be2

- Monzalve, M., & Horner, R. H. (2021). The impact of the Contextual Fit Enhancement Protocol on behavior support plan fidelity and student behavior. Behavioral Disorders,46, 267–278. 10.1177/0198742920953497 [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb, E. T., & Hagopian, L. P. (2018). Treatment of severe problem behaviour in children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities. International Review of Psychiatry,30, 96–109. 10.1080/09540261.2018.1435513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosik, M. R., & Carr, J. E. (2016). On the distinction between the motivating operation and setting event concepts. The Behavior Analyst,38, 219–223. 10.1007/s40614-015-0042-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuta, R., Koudys, J., & O’Neill, P. (2021). Parent treatment integrity across multiple components of a behavioral intervention. Behavioral Interventions,36(4), 796–816. 10.1002/bin.1817 [Google Scholar]

- Oropeza, M. E., Fritz, J. N., Nissen, M. A., Terrell, A. S., & Phillips, L. A. (2018). Effects of therapist-worn protective equipment during functional analysis of aggression. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,51(3), 681–686. 10.1002/jaba.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pétursdóttir, A. L. (2017). Distance training in function-based intervention to decrease student problem behavior: Summary of 74 cases from a university course. Psychology in the Schools,54, 213–227. 10.1002/pits.21998 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, L., Wilson, L., & Wilson, E. (2010). Assessing behaviour support plans for people with intellectual disability before and after the Victorian Disability Act 2006. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability,35, 9–13. 10.3109/13668250903499090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C. L., Iannoccone, J. A., Rooker, G. W., & Hagopian, L. P. (2017). Noncontingent reinforcement for the treatment of severe problem behavior: An analysis of 27 consecutive applications. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,50, 357–376. 10.1002/jaba.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Positive Environments, Network of Trainers. (2021). Essential 10: Essential Components of Behavior Intervention Plans. https://www.pent.ca.gov/bi/essential10/documents/essential10-rubric.pdf

- Quigley, S. P., Ross, R. K., Field, S., & Conway, A. A. (2018). Toward an understanding of the essential components of behavior analytic service plans. Behavior Analysis in Practice,11, 436–444. 10.1007/s40617-018-0255-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman, A., Austin, J. L., Gover, H. C., Cammilleri, A. P., Donnelly, D. R., & Hanley, G. P. (2021). Toward trauma-informed applications of behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,55, 40–61. 10.1002/jaba.881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig, L. A., Fritz, J. N., Campbell, K. E., Williams, S. D., Smith, L. D., & Dawson, K. W. (2019). Comparison of blocking strategies informed by precursor assessment to decrease pica. Behavioral Interventions,34, 198–215. 10.1002/bin.1660 [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraman, M., & Fahmie, T. A. (2020). A systematic review of cultural adaptations in the global application of ABA-based telehealth services. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,53(4), 1838–1855. 10.1002/jaba.763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. (2022). Behavior skills training for family caregivers of people with intellectual or developmental disabilities: A systematic review of literature. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities,68(3), 247–273. 10.1080/20473869.2020.1793650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic Consultation Service. 12VAC30-122-550. (2021). https://law.lis.virginia.gov/admincode/title12/agency30/chapter122/section550/

- Thompson, C., & MacNaul, H. (2023). Using pyramidal training to address challenging behavior in an early childhood education classroom. Education Sciences,13(6), 539. 10.3390/educsci13060539 [Google Scholar]

- Tiger, J. H., & Effertz, H. M. (2021). On the validity of data produced by isolated and synthesized contingencies during the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,54(3), 853–876. 10.1002/jaba.792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tincani, M., & Travers, J. (2019). Replication research, publication bias, and applied behavior analysis. Perspectives on Behavior Science,42, 59–75. 10.1007/s40614-019-00191-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon, S., & Lanovaz, M. J. (2020). Tutorial: Applying machine learning in behavioral research. Perspectives on Behavior Science,43, 697–723. 10.1007/s40614-020-00270-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States of America v. Commonwealth of Virginia, and Peggy Wood et al. 3:12CV59-JAG. (2020). https://dbhds.virginia.gov/assets/doc/settlement/indreview/joint-filing-of-complete-set-of-agreed-compliance-indicators-as-filed-01.14.20.pdf

- United States of America v. Commonwealth of Virginia, and Peggy Wood et al. v. Robert McDonnell et al., 3:12CV59-JAG. (2012). https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/crt/legacy/2012/09/05/va_orderapprovingdecree_8-23-12.pdf

- Van Houten, R., Axelrod, S., Bailey, J. S., Favell, J. E., Foxx, R. M., Iwata, B. A., & Lovaas, I. O. (1988). The right to effective behavioral treatment. The Behavior Analyst,11, 111–114. 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services. (2018). 2018 person-centered ISP guidance. https://townhall.virginia.gov/L/GetFile.cfm?File=C:/TownHall/docroot/GuidanceDocs/720/GDoc_DBHDS_6379_v1.pdf

- Virginia Department of Behavioral Health & Developmental Services & Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services. (2021). Practice guidelines for behavior support plans. https://www.townhall.virginia.gov/L/GetFile.cfm?File=C:/TownHall/docroot/GuidanceDocs/602/GDoc_DMAS_7024_v1.pdf

- Virginia Registrar of Regulations. (2019, February 4). Volume 35, Issue 11. http://register.dls.virginia.gov/vol35/iss12/v35i12.pdf

- Virginia Regulatory Town Hall. (n.d.). Regulatory actions and stages. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://townhall.virginia.gov/um/actiontypes.cfm

- Vivanti, G. (2020). Ask the editor: What is the most appropriate way to talk about individuals with a diagnosis of autism? Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders,50, 691–693. 10.1007/s10803-019-04280-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, T. R., Iwata, B. A., Zarcone, J. R., & Rodgers, T. A. (1992). A content analysis of written behavior management programs. Research in Developmental Disabilities,13, 429–441. 10.1016/0891-4222(92)90001-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, T. R., Peters, K. P., Kronfli, F. R., Lloveras, L. A., & Ibañez, V. F. (2020). On the definition of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,53(3), 1299–1303. 10.1002/jaba.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardale, S., Davis, F. J., Vassos, M., & Nankervis, K. (2016). The outcome of a statewide audit of the quality of positive behaviour support plans. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability,43, 202–212. 10.3109/13668250.2016.1254736 [Google Scholar]

- Willis, T. J., LaVigna, G. W., & Donnellan, A. M. (2011). Behavior assessment guide. Institute for Applied Behavior Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. E., & Vollmer, T. R. (2015). Essential components of written behavior treatment plans. Research in Developmental Disabilities,36, 323–327. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P. (2017). The effect of teacher training on the knowledge of positive behavior support and the quality of behavior intervention plans: A preliminary study in Taiwan. Universal Journal of Educational Research,5(9), 1653–1665. 10.13189/ujer.2017.050923 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There is no associated data for this article. The referenced tool and instructions can be accessed by contacting the primary author or at https://dbhds.virginia.gov/developmental-services/behavioral-services/.