Abstract

Background

The efficacy of supplementation with branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and vitamin D with exercise in elderly people remains unclear. This study aimed to examine whether the combination of exercise and supplementation with BCAA- and vitamin D-containing high-protein food would be effective in improving soft lean mass and physical functions in elderly people with impaired physical functions.

Methods

This 12-week interventional study recruited elderly people ≥ 60 years of age with impaired physical activity (locomotive syndrome, LS). The participants were assigned to one of the following three groups: exercise group (group EX, n = 46), exercise with supplementation of BCAA- and vitamin D-containing high-protein food group (group EF, n = 45), and control group (group C, n = 31). Subjects in group EX were instructed to perform locomotion training, and those in group EF were instructed to consume high-protein test food in addition to locomotion training. The soft lean mass, a self-administered questionnaire (Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale-25, GLFS-25) and physical tests (stand-up test, two-step test), and the value of 25OH vitamin D were compared among the three groups after three months of intervention.

Results

There were no significant declines in soft lean mass in group EF, while significant declines were detected in the other two groups. There were significant differences in the stand-up test scores among the three groups (p = 0.03). A post-hoc analysis showed a significant difference between groups C and EF. There was a significant difference in the two-step test scores among the three groups (p = 0.004). A post-hoc analysis showed significant differences between groups C and EX, and between groups C and EF. There were no significant differences in the GLFS-25 scores among the groups. There was a significant increase in the value of 25OH vitamin D after three months in group EF (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

This study showed that BCAA and vitamin D supplementation with exercise in elderly subjects with declining physical functions resulted in maintenance of soft lean mass, improvement in physical functions (stand-up test score and two-step test), and an increase in 25OH vitamin D.

Trial registration

This study was prospectively registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network on 01/02/2018 (UMIN000030567).

Keywords: Branched-chain amino acid, Vitamin D, Exercise, Soft lean mass, Physical function

Background

Aging is a natural stage of life involving physical, psychological, and social changes. It is crucial that older adults adopt strategies to maintain or improve their quality of life to age actively and healthily. Among the most recommended non-pharmacological strategies is physical exercise [1]. Strength training serves as a key strategy for healthy aging, not only preventing frailty and falls but also improving quality of life in older adults. Strengthening lower limbs reduces the short-term risk of falls and contributes to maintaining balance and functional autonomy, thus enhancing quality of life [2]. Sarcopenia is an age-related condition characterized by a decline in muscle mass, strength, and function, which is linked to impaired mobility, reduced quality of life, and increased risk of traumatic injuries, including fractures [3–5]. However, individuals with decreased muscle strength but without significant muscle mass loss—referred to as dynapenia—may be overlooked, since sarcopenia diagnosis primarily relies on reduced muscle volume. To address broader mobility impairments beyond sarcopenia, the Japanese Orthopaedic Association introduced the concept of “locomotive syndrome (LS)” in 2007, defined as a decline in mobility caused by deterioration of locomotive organs [6]. Reduced mobility —encompassing activities such as walking, standing, and sitting—due to dysfunction of bones, muscles, or joints, has been identified as a risk factor for requiring medical and nursing care [6, 7].

To prevent the development of sarcopenia and LS, previous studies have shown the pivotal role of habitual exercise and nutritional intervention in elderly people [8–10]. Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), which include leucine, isoleucine, and valine, are three of the nine essential amino acids in humans. Supplementation with BCAAs has been shown to accelerate muscle protein synthesis, leading to increased muscle mass and strength in elderly individuals [11–13]. Likewise, vitamin D deficiency is associated with reduced muscle volume and function, while vitamin D supplementation improves these parameters [14–16]. The combined effect of exercise and nutritional intervention, including BCAA and vitamin D supplementation, has been demonstrated to be more effective than either intervention alone in enhancing muscle health in older adults [17–19]. Nevertheless, evidence remains limited regarding the combined impact of exercise and supplementation with both BCAAs and vitamin D on muscle condition and physiological function in elderly populations. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of combining exercise with supplementation of a high-protein product containing BCAAs and vitamin D in improving locomotion-related outcomes and body composition among elderly individuals with diminished physical function.

Methods

Study design and participant recruitment

This 12-week interventional study was conducted from 2018 to 2020. This study was approved by the institutional review board (Approval No. I-0027). All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2013. All participants gave written informed consent before participating in this study.

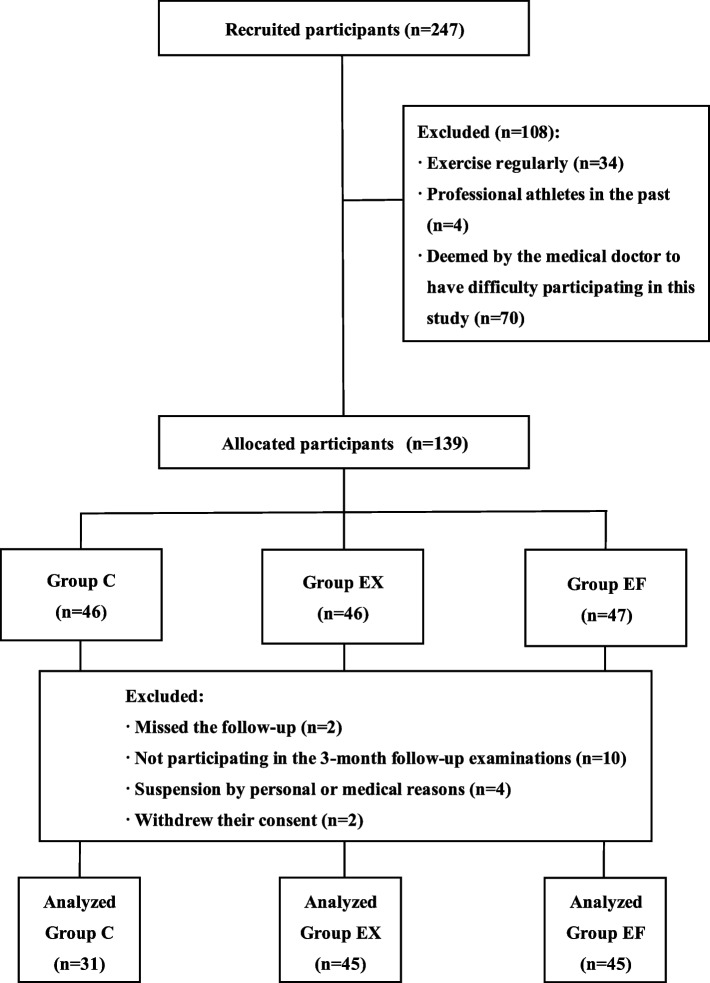

Participants were recruited from people ≥ 60-years-old who lived in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. The participants were recruited from three different towns in Miyazaki Prefecture. Because this study was not a randomized comparative study, the enrolled participants from the same town were finally allocated to the same group. Exclusion criteria included regular exercisers, former professional athletes, and individuals judged by a medical doctor as unable to participate in the study. Of the 247 individuals initially enrolled, 108 were excluded based on the criteria above. Additionally, 2 participants were lost to follow-up, 10 could not attend the 3-month follow-up examination, and 4 withdrew for personal or medical reasons. Two participants withdrew consent during the study. Ultimately, 121 elderly subjects completed the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the enrollment of the study participants

The participants’ baseline data (Table 1) included demographic data (age, gender, height, weight, body mass index), grade of LS, presence of pain (knee, back, hip, shoulder, others), and medical history. Medical history included lifestyle-related diseases (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, other lifestyle-related diseases), cardiovascular diseases (angina, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, other heart disease), cerebrovascular diseases (intracranial hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, other brain diseases), and kidney diseases (chronic kidney disease, kidney stones, nephritis, pyelonephritis, nephrogenic anemia, and hyperkalemia), and others.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

| Group C | Group EX | Group EF | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male/female | 7/24 | 6/39 | 7/38 | 0.552 |

| Age, yrs | 77.3 ± 7.0 | 78.0 ± 7.4 | 76.6 ± 6.5 | 0.607 |

| Height, cm | 150.1 ± 8.6 | 150.7 ± 7.1 | 150.2 ± 7.9 | 0.917 |

| Weight, kg | 53.9 ± 10.4 | 53.8 ± 8.0 | 52.2 ± 10.1 | 0.634 |

| Body mass index | 23.8 ± 3.1 | 23.6 ± 2.6 | 23.0 ± 3.7 | 0.554 |

| Grade of locomotive syndrome, grade 1/2/3 | 16/15/0 | 29/16/0 | 31/14/0 | 0.297 |

| Medical history (%) | 71.0 | 68.9 | 53.3 | 0.190 |

| Presence of pain (%) | ||||

| Knee pain | 41.9 | 44.4 | 24.4 | 0.108 |

| Lower back pain | 32.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 0.994 |

| Hip pain | 3.2 | 11.1 | 4.4 | 0.302 |

| Shoulder pain | 23.8 | 13.3 | 11.1 | 0.192 |

| Other pain | 6.5 | 13.3 | 2.2 | 0.129 |

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

Research procedures

In this study, participants were assigned to one of three groups:

Exercise only group (EX): performed locomotion training [20].

Exercise plus supplementation group (EF): same exercise as group EX plus one serving of BCAA- and vitamin D-containing high-protein food within 30 min post-exercise.

Control group (C): no intervention. Weekly phone calls monitored adherence.

In group EX, participants were instructed to perform locomotion training [20]. In group EF, in addition to the same exercise protocol assigned to group EX, participants were instructed to take one bag of BCAA-and vitamin D-containing high-protein food ("BODY MAINTÉ Jelly", Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd) within 30 min after locomotion training. Table 2 shows the nutritional characteristics of the study product. During the study period of three months, participants in groups EX and EF were given a phone call once a week to confirm the performance of locomotion training. In addition, continuous intake of the study product was confirmed in group EF.

Table 2.

Nutritional components of the BCAA-and vitamin D-containing high-protein product used in this study

| Energy: 90 kcal, |

|---|

| Protein: 10 g, Fat: 0 g, Carbohydrates: 13 g |

| Salt equivalent: 0.11 g, Vitamin B6: 5 mg, Vitamin D: 10 μg |

| Amino acid: 2,500 mg (Valine: 500 mg, Leucine: 1,000 mg, Isoleucine: 500 mg, |

| Arginine: 500 mg), Citric acid: 1,250 mg |

| Lactic acid bacteria: Lactiplantibacillus pentosus ONRICb0240 |

*Nutritional facts label per bag (100 g) of product

Locomotion training

Locomotion training consisted of the following four types of exercises: open-eye single- leg standing, squatting, heel-raise exercise, and forward lunge exercise. Locomotion training has been reported to be effective in preventing LS [21].

Open-eye single-leg standing

Open-eye single-leg standing is an exercise in which one lower leg is raised slightly off the floor. To improve their balance ability, participants performed the exercise for each lower leg for one minute three times per day.

Squatting

Squats are exercises in which the knees are slowly flexed for a couple of seconds and then slowly returned to their original position. However, locomotion training also recommends getting up from a chair with hands on the table for those who cannot squat. To improve lower limb muscle strength, participants performed five repetitions three times per day.

Heel raise exercise

Heel-raise exercise is an exercise in which stand up straight with your feet about hip-width apart then slowly lift your heels off the ground, rising onto the balls of your feet, slowly returned to their original position.

Forward lunge exercise

The forward lunge exercise is an exercise in which the legs are stepped forward, the body is lowered until both knees are bent, and the front heel is pushed back to the starting position.

Regarding heel-raise exercise and forward lunge exercise, the participants performed one set of 10 repetitions, three times per day.

Evaluation of the outcomes

The measurement of soft lean mass, self-administered questionnaire and physical tests for the assessment of LS, and blood test were performed at two points: baseline and 3 months after intervention.

Measurement of the soft lean mass

Soft lean mass of the trunk and limbs was measured via bioelectrical impedance analysis (Inbody S10, Inbody Japan, Tokyo, Japan), using a standardized standing position. The accuracy of this method has been validated in frail elderly individuals (> 75 years) [22].

Geriatric locomotive function scale-25 (GLFS-25)

The GLFS-25 is a self-administered questionnaire designed to assess LS in elderly individuals. This questionnaire was developed by the Japanese Orthopaedic Association to evaluate physical function, daily activities, and social participation. This scoring system comprises 25 questions, including four on pain within the last month, 16 on daily activities during the last month, three on social functions, and two on mental health during the last month. Each question was graded on a five-point scale from 0 (no impairment) to 4 (severe impairment). The total score ranges from 0 to 100 points (with 0 being the healthiest and 100 being the least healthy).

Physical tests (stand-up test, two-step test)

To evaluate locomotive ability, two simple physical tests, a stand-up test and a two-step test, were performed [23, 24]. In the stand-up test, the strength of the lower extremities was evaluated by standing on one or both lower legs from a seat with a specific height (40, 30, 20, and 10 cm). The minimum height from which the participant could stand up without assistance was the result. The results were scored from 0 to 8 according to the study by Ogata et al. [23]. In the two-step test, participants moved forward with the widest length of the two strides from the starting line. The score was calculated by dividing the distance by the participant’s height. The best result of two attempts was the result.

Blood test (25 OH vitamin D)

The 25OH vitamin D concentration was evaluated by a blood test.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for between-group comparisons; paired t-tests for within-group changes. Chi-square tests analyzed categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Sample size was estimated using soft lean mass data from 39 elderly volunteers (mean age, 75.1 [range 70–88] years; female, n = 30; male, n = 9). With α = 0.05 and 80% power, 41 participants per group were needed to detect a 1.5% difference. Accounting for 10% dropout, 46 participants per group were recruited.

Results

Change of soft lean mass

The soft lean mass at baseline and after 3 months and the relative changes in the three groups are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in the soft lean mass of all body parts at baseline and after three months among the three groups. Regarding the relative change in soft lean mass between baseline and after three months, there was a significant difference in the lean mass of the left lower extremity among the three groups: group C (−0.17) vs. group EX (−0.18) vs. group EF (−0.01), p = 0.047.

Table 3.

Comparison of soft lean mass at baseline and after 3 months

| Group C | Group EX | Group EF | §P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lean mass | Baseline | 33.32 ± 6.58* | 33.33 ± 4.54* | 32.21 ± 5.28 | 0.549 |

| (kg) | After 3 M | 32.58 ± 6.34* | 32.70 ± 4.40* | 32.07 ± 5.30 | 0.842 |

| Change | −0.74 ± 1.15 | −0.64 ± 1.33 | −0.14 ± 1.15 | 0.063 | |

| *P value | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.418 | ||

| Right upper limb | Baseline | 1.71 ± 0.56* | 1.61 ± 0.34 | 1.56 ± 0.38 | 0.318 |

| (kg) | After 3 M | 1.66 ± 0.54* | 1.59 ± 0.35 | 1.56 ± 0.40 | 0.598 |

| Change | −0.05 ± 0.11 | −0.02 ± 0.09 | 0.00 ± 0.09 | 0.106 | |

| *P value | 0.014 | 0.149 | 0.847 | ||

| Left upper limb | Baseline | 1.69 ± 0.54* | 1.61 ± 0.33 | 1.54 ± 0.37 | 0.286 |

| (kg) | After 3 M | 1.64 ± 0.52* | 1.59 ± 0.34 | 1.54 ± 0.39 | 0.591 |

| Change | −0.05 ± 0.11 | −0.02 ± 0.09 | 0.00 ± 0.09 | 0.062 | |

| *P value | 0.017 | 0.127 | 0.776 | ||

| Trunk | Baseline | 15.74 ± 3.52* | 15.29 ± 2.23 | 14.97 ± 2.59 | 0.493 |

| (kg) | After 3 M | 15.50 ± 3.45* | 15.22 ± 2.32 | 14.99 ± 2.69 | 0.733 |

| Change | −0.24 ± 0.55 | −0.07 ± 0.46 | 0.02 ± 0.49 | 0.097 | |

| *P value | 0.024 | 0.319 | 0.883 | ||

| Right lower limb | Baseline | 5.19 ± 1.43* | 5.31 ± 1.04* | 5.03 ± 1.29 | 0.562 |

| (kg) | After 3 M | 4.99 ± 1.35* | 5.13 ± 0.90* | 5.00 ± 1.23 | 0.843 |

| Change | −0.20 ± 0.33 | −0.19 ± 0.44 | −0.03 ± 0.30 | 0.062 | |

| *P value | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.576 | ||

| Left lower limb | Baseline | 5.18 ± 1.38* | 5.31 ± 1.04* | 5.03 ± 1.23 | 0.511 |

| (kg) | After 3 M | 5.01 ± 1.31* | 5.13 ± 0.90* | 5.02 ± 1.21 | 0.868 |

| Change | −0.17 ± 0.32† | −0.18 ± 0.42 | −0.01 ± 0.28† | 0.047 | |

| *P value | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.829 |

*compared between the baseline and after 3 months by paired t-test

§compared between the three groups by ANOVA

† significant differences between the three groups (p > 0.05)

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

In terms of the relative change in lean mass in each group, statistically significant declines in lean mass in the all body parts were detected in group C. In group EX, statistically significant declines were detected in the total lean mass and bilateral lower limbs. In group EF, there were no significant declines in lean mass in any part of the body.

Physical tests (stand-up test and two-step test) and GLFS-25 scores

The results of physical tests (stand-up test and two-step test) and GLFS-25 scores are shown in Table 4. Regarding the stand-up test score, there was a significant difference in the score after three months among the three groups (p = 0.03). A post-hoc analysis showed a significant difference between groups C and EF. Regarding the two-step test, there was a significant difference in the score after three months among the three groups (p = 0.004). A post-hoc analysis showed significant differences between groups C and EX, and between groups C and EF. Regarding the GLFS-25 score, there was no significant difference after three months among the three groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of physical tests and GLFS-25 scores at baseline and after 3 months

| Group C | Group EX | Group EF | §P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand-up test score | Baseline | 3.58 ± 0.99 | 3.62 ± 0.98* | 4.04 ± 1.04 | 0.072 |

| After 3 M | 3.52 ± 1.26† | 3.84 ± 1.17* | 4.22 ± 1.06† | 0.033 | |

| Change | −0.07 ± 0.57 | 0.22 ± 0.74 | 0.18 ± 0.61 | 0.147 | |

| *P value | 0.536 | < 0.001 | 0.058 | ||

| Two-step test | Baseline | 1.206 ± 0.155 | 1.230 ± 0.156* | 1.249 ± 0.127 | 0.446 |

| After 3 M | 1.182 ± 0.130†‡ | 1.286 ± 0.155*† | 1.268 ± 0.123 ‡ | 0.004 | |

| Change | −0.002 ± 0.104† | 0.056 ± 0.166† | 0.019 ± 0.109 | 0.008 | |

| *P value | 0.203 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | ||

| GLFS-25 score | Baseline | 10.29 ± 6.66 | 9.36 ± 5.57* | 7.33 ± 6.35* | 0.097 |

| After 3 M | 8.87 ± 6.32 | 7.11 ± 5.10* | 5.73 ± 6.23* | 0.076 | |

| Change | −1.42 ± 3.91 | −2.24 ± 5.74 | −1.6 ± 3.69 | 0.709 | |

| *P value | 0.052 | 0.004 | 0.009 |

*compared between the baseline and after 3 months by paired t-test

§compared among the three groups by ANOVA

†, ‡ significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05)

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

25OH vitamin D concentration

The 25OH vitamin D concentration are shown in Table 5. There was a significant difference in the 25OH vitamin D concentrations after three months among the three groups (p < 0.001). There were significant declines in the 25OH vitamin D concentration after three months in groups C and EX. There was a significant increase in the 25OH vitamin D concentration after three months in group EF (p < 0.001).

Table 5.

25OH Vitamin D concentration at baseline and after 3 months

| 25OH Vitamin D | Group C | Group EX | Group EF | §P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 19.32 ± 5.81* | 18.51 ± 4.86* | 18.77 ± 4.36* | 0.78 |

| After 3 months | 18.48 ± 5.12*† | 17.00 ± 3.87*‡ | 21.93 ± 4.18*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Change | −0.84 ± 4.58† | −1.51 ± 4.10‡ | 3.16 ± 4.14 †‡ | < 0.001 |

| *P value | 0.316 | 0.017 | < 0.001 |

*compared between the baseline and after 3 months by paired t-test

§compared among the three groups by ANOVA

†, ‡ significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05)

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

Change of the grade of locomotive syndrome

In group C, the grade of LS improved in 9.7% (3/31) and deteriorated in 9.7% (3/31). In group EX, the grade of LS improved in 26.7% (12/45) and deteriorated in 6.7% (3/45). In group EF, the grade of LS improved in 28.9% (13/45) and deteriorated in 6.7% (3/45).

Discussion

This interventional study evaluated the effects of combining exercise with BCAA- and vitamin D-enriched supplementation in elderly individuals with declining physical function. Key findings of the present study were as follow: (1) Group EF maintained soft lean mass; (2) Groups EX and EF improved physical performance; (3) only Group EF showed increased 25OH vitamin D levels.

Many previous studies have reported the efficacy of exercise and food supplementation in preventing the development of sarcopenia or LS [8–10, 25]. BCAAs have been shown to accelerate protein synthesis and prevent protein degradation [3, 4, 26, 27]. Additionally, Busquets et al. found that BCAA was associated with decreased lysosomal protease activity, which leads to the decreased expression of proteolytic genes [5, 28]. Shimomura et al. reported that BCAA supplementation before and after exercise was effective in decreasing exercise-induced muscle damage and promoting muscle-protein synthesis, showing the efficacy of combined exercise and intake of BCAAs on the muscle function [11]. Peng et al. also supported the combination of exercise and BCAA supplementation for increasing the muscle volume in elderly subjects [29]. According to a recent systematic review by Bai et al. [30], supplementation with BCAAs may be beneficial for strengthening handgrip and maintaining muscle volume in the elderly. However, this systematic review also reported a high degree of heterogeneity among the included studies, suggesting that more studies are needed to verify the clinical significance of BCAA supplementation for elderly individuals.

Vitamin D influences muscle via gene expression and inflammatory pathways [31, 32]. Regarding the influence of vitamin D supplementation on the muscle function in elderly subjects, Cangussu et al. reported strength improvements after nine months of supplementation [33]. Other trials observed increases in vitamin D receptor levels and muscle fiber size [34]. Combined BCAA and vitamin D interventions have also been shown to be effective for elderly individuals [35–37]. Bauer et al. reported that vitamin D and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplementation without exercise was effective in improving hand-grip strength and lower-extremity functions in older sarcopenic individuals [35]. However, few studies have examined the combined effect of exercise and BCAA plus vitamin D supplementation. Only one prior study has explored an 8-week intervention in sarcopenic adults, showing functional gains but no impact on daily activity [38]. The authors reported a significantly better improvement in hand grip strength and calf circumference in the intervention group compared with the control group, although no significant improvement in ADL performance was detected. In the present study, exercise with combined BCAA and vitamin D supplementation prevented soft lean mass decline, and improved physical performance, and increased serum 25OH vitamin D in elderly individuals with functional decline, suggesting the promising efficacy of this strategy (exercise plus BCAA and vitamin D supplementation) for preventing the development of sarcopenia or LS in elderly individuals. Further clinical studies with a large sample size are needed to clarify the practical application of this strategy in elderly individuals.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, although this was an interventional study, the participants were not randomly allocated to each group; thus, there was a potential selection bias. Second, the sample size was not large although a sample size calculation was performed prior to the study to provide > 80% power. Third, there was no group in which BCAA- and vitamin D-containing high-protein food supplementation was offered without exercise. Fourth, although statistical significances were detected in the physical tests (stand-up test and two-step test) after three months of intervention among the three groups, clinical significance of these findings remains unclear solely by the current study. Fifth, the intervention period was three months and the influence of the intervention over a longer period is unclear. Finally, elderly subjects with grade 3 LS were not included in this study. Therefore, the influence of exercise plus BCAA- and vitamin-D containing high-protein food supplementation on subjects with a more severe decline in their physical function was not assessed. Despite these limitations, the present study will contribute to a better understanding of the efficacy of exercise plus BCAA- and vitamin-D containing high-protein food supplementation in elderly individuals.

Conclusions

This 12-week interventional study showed that exercise combined with BCAA and vitamin D supplementation can maintain muscle mass, enhance physical function, and improve 25OH vitamin D status in elderly adults experiencing physical decline.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff members of the Tsuno Town Welfare Division and the Kijo Town Welfare and Health Division for their cooperation in conducting this study. We would also like to express our deep gratitude to Ms. Michiko Sugita, Ms. Anna Koide, Ms. Megumi Iwakiri, and other staff members who cooperated with data creation and management, and Mr. Hisashi Tanaka, Academic Department, Nutraceuticals Division, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.

Abbreviations

- LS

Locomotive syndrome

- BCAA

Branched-chain amino acid

- GLFS-25

Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale-25

Authors’ contributions

YN, TF, TY, KO: conception and design, drafting of the article. HK, KH, TF, KO, HA: acquisition and analysis of the data. EC, NK: conception and design, supervision of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research funding and materials were provided by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Miyazaki University Medical Ethics Committee (Research Project Number: I-0027). The study protocols were completed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

Competing interests

Hiroyuki Kimura and Koichiro Hamada are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest. BODY MAINTÉ Jelly is a high-protein food containing BCAA and vitamin D from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yoshihiro Nakamura and Koki Ouchi contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Sanchís-Soler G, Sebastiá-Amat S, Parra-Rizo MA. Mental health and social integration in active older adults according to the type of sport practiced. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2025;255: 104920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seguin R, Nelson ME. The benefits of strength training for older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3 Suppl 2):141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(4):601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayer AA, Cruz-Jentoft A. Sarcopenia definition, diagnosis and treatment: consensus is growing. Age Ageing. 2022. 10.1093/ageing/afac220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott D, Blizzard L, Fell J, Giles G, Jones G. Associations between dietary nutrient intake and muscle mass and strength in community-dwelling older adults: the Tasmanian older adult cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(11):2129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K. A “super-aged” society and the “locomotive syndrome.” J Orthop Sci. 2008;13(1):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura K. Locomotive syndrome: disability-free life expectancy and locomotive organ health in a “super-aged” society. J Orthop Sci. 2009;14(1):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi S, Yamada K, Ito YM, Fuji T, Sato K, Ohe T. Frequency-response relationship between exercise and locomotive syndrome across age groups: secondary analysis of a nationwide cross-sectional study in Japan. Mod Rheumatol. 2023;33(3):617–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura A, Ito N, Asanuma K, Akeda K, Ogura T, Sudo A. Do exercise habits during middle age affect locomotive syndrome in old age? Mod Rheumatol. 2018;28(2):334–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoyama Y, Nishi M, Murayama H, Amano H, Taniguchi Y, Nofuji Y, Narita M, Matsuo E, Seino S, Kawano Y, et al. Dietary variety and decline in lean mass and physical performance in community-dwelling older Japanese: a 4-year follow-up study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(1):11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimomura Y, Murakami T, Nakai N, Nagasaki M, Harris RA. Exercise promotes BCAA catabolism: effects of BCAA supplementation on skeletal muscle during exercise. J Nutr. 2004;134(6 Suppl):1583s–7s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SY, Lee HJ, Lim JY. Effects of leucine-rich protein supplements in older adults with sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;102: 104758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komar B, Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Effects of leucine-rich protein supplements on anthropometric parameter and muscle strength in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(4):437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bollen SE, Bass JJ, Fujita S, Wilkinson D, Hewison M, Atherton PJ. The Vitamin D/Vitamin D receptor (VDR) axis in muscle atrophy and sarcopenia. Cell Signal. 2022;96:110355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato Y, Iwamoto J, Kanoko T, Satoh K. Low-dose vitamin D prevents muscular atrophy and reduces falls and hip fractures in women after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20(3):187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass JJ, Nakhuda A, Deane CS, Brook MS, Wilkinson DJ, Phillips BE, Philp A, Tarum J, Kadi F, Andersen D, et al. Overexpression of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) induces skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Mol Metab. 2020;42: 101059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson DJ, Bukhari SSI, Phillips BE, Limb MC, Cegielski J, Brook MS, Rankin D, Mitchell WK, Kobayashi H, Williams JP, et al. Effects of leucine-enriched essential amino acid and whey protein bolus dosing upon skeletal muscle protein synthesis at rest and after exercise in older women. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(6 Pt A):2011–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bukhari SS, Phillips BE, Wilkinson DJ, Limb MC, Rankin D, Mitchell WK, Kobayashi H, Greenhaff PL, Smith K, Atherton PJ. Intake of low-dose leucine-rich essential amino acids stimulates muscle anabolism equivalently to bolus whey protein in older women at rest and after exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308(12):E1056-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornton M, Sim M, Kennedy MA, Blodgett K, Joseph R, Pojednic R. Nutrition interventions on muscle-related components of sarcopenia in females: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Calcif Tissue Int. 2024;114(1):38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Japanese Orthopedic Association Corporation: Locomo Challenge Promotion Conference, LOCOMO Pamphlets FY 2015 version. In.

- 21.Ishibashi H. Locomotive syndrome in Japan. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2018;4(3):86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim M, Kim H. Accuracy of segmental multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis for assessing whole-body and appendicular fat mass and lean soft tissue mass in frail women aged 75 years and older. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(4):395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogata T, Muranaga S, Ishibashi H, Ohe T, Izumida R, Yoshimura N, Iwaya T, Nakamura K. Development of a screening program to assess motor function in the adult population: a cross-sectional observational study. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(5):888–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muranaga SHK. Development of a convenient way to predict ability to walk, using a two-step test. J Showa Med Assoc. 2003;63:301–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duan Y, Qi Q, Cui Y, Yang L, Zhang M, Liu H. Effects of dietary diversity on frailty in Chinese older adults: a 3-year cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norton LE, Layman DK. Leucine regulates translation initiation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle after exercise. J Nutr. 2006;136(2):533s–7s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blomstrand E, Eliasson J, Karlsson HK, Köhnke R. Branched-chain amino acids activate key enzymes in protein synthesis after physical exercise. J Nutr. 2006;136(1 Suppl):269s–73s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busquets S, Alvarez B, Llovera M, Agell N, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM. Branched-chain amino acids inhibit proteolysis in rat skeletal muscle: mechanisms involved. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184(3):380–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng LN, Yu PC, Hsu CC, Tseng SH, Lee WJ, Lin MH, Hsiao FY, Chen LK. Sarcojoint®, the branched-chain amino acid-based supplement, plus resistance exercise improved muscle mass in adults aged 50 years and older: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Exp Gerontol. 2022;157: 111644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bai GH, Tsai MC, Tsai HW, Chang CC, Hou WH. Effects of branched-chain amino acid-rich supplementation on EWGSOP2 criteria for sarcopenia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(2):637–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cereda E, Pisati R, Rondanelli M, Caccialanza R. Whey protein, leucine- and vitamin-D-enriched oral nutritional supplementation for the treatment of sarcopenia. Nutrients. 2022. 10.3390/nu14071524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasimi N, Sohrabi Z, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Eskandari MH, Bedeltavana A, Famouri M, Talezadeh P. A novel fortified dairy product and sarcopenia measures in sarcopenic older adults: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(4):809–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cangussu LM, Nahas-Neto J, Orsatti CL, Bueloni-Dias FN, Nahas EA. Effect of vitamin D supplementation alone on muscle function in postmenopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(10):2413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ceglia L, Niramitmahapanya S, da Silva MM, Rivas DA, Harris SS, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Fielding RA, Dawson-Hughes B. A randomized study on the effect of vitamin D₃ supplementation on skeletal muscle morphology and vitamin D receptor concentration in older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):E1927-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer JM, Verlaan S, Bautmans I, Brandt K, Donini LM, Maggio M, McMurdo ME, Mets T, Seal C, Wijers SL, et al. Effects of a vitamin D and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplement on measures of sarcopenia in older adults, the PROVIDE study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(9):740–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bo Y, Liu C, Ji Z, Yang R, An Q, Zhang X, You J, Duan D, Sun Y, Zhu Y, et al. A high whey protein, vitamin D and E supplement preserves muscle mass, strength, and quality of life in sarcopenic older adults: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verlaan S, Maier AB, Bauer JM, Bautmans I, Brandt K, Donini LM, Maggio M, McMurdo MET, Mets T, Seal C, et al. Sufficient levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and protein intake required to increase muscle mass in sarcopenic older adults - The PROVIDE study. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(2):551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeuchi I, Yoshimura Y, Shimazu S, Jeong S, Yamaga M, Koga H. Effects of branched-chain amino acids and vitamin D supplementation on physical function, muscle mass and strength, and nutritional status in sarcopenic older adults undergoing hospital-based rehabilitation: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(1):12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.