Abstract

Background

Due to the patella’s thin overlying skin, metal implants frequently cause local discomfort that necessitates removal. This study aimed to evaluate the intraoperative and early postoperative outcomes of treating comminuted patellar fractures using non-absorbable sutures as the sole internal fixation method via the Nice knot technique.

Methods

This retrospective study reviewed 25 patients with unilateral closed comminuted patellar fractures who underwent open reduction and internal fixation using either non-absorbable sutures tied with a Nice knot (NK group, n = 12) or the traditional tension band technique (TB group, n = 13). Intraoperative surgical time and blood loss were recorded. Postoperative clinical outcomes were evaluated using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain, knee range of motion (ROM), and the Böstman scoring system. Radiographic assessments were conducted to evaluate fracture healing. Complications, including infection, implant loosening, and discomfort or irritation, were also documented.

Results

Although the intraoperative surgical time was slightly longer in the NK group compared to the TB group, the difference was not statistically significant. The difference in blood loss between the NK and TB groups was also not statistically significant. No cases of bone non-union, implant loosening, or internal fixation failure were observed in either group during the follow-up period. One patient in the TB group developed a wound infection one week postoperatively. At the final follow-up, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of VAS scores, knee range of motion (ROM), or Böstman scores. However, in the TB group, five patients reported notable discomfort or irritation caused by the internal fixation.

Conclusion

Compared with traditional tension band fixation, the Nice knot technique reduces soft tissue irritation, avoids implant removal surgery, potentially lowers postoperative infection rates, and achieves comparable fracture healing time and knee function. However, broader validation through multi-center studies is required.

Keywords: Patella fractures, Nice knot, Non-metal fixation, Non-absorbable suture fixation

Introduction

The patella’s unique pulley-like structure is critical for knee function [1, 2]. Patellar fractures account for about 1% of all fractures. If the extensor mechanism of the knee joint is disrupted or joint consistency is affected, surgery is required [3]. Various internal fixation methods are available for treating patellar fractures, including tension band construct, screw fixation, headless compression screws with wiring, nitinol patellar concentrator, and fixed angle plates, among others [4–7]. Due to the thin overlying skin of the patella, metal implants often lead to pain, irritation, prominence and other discomforts. Moreover, it can produce artifacts in knee magnetic resonance imaging scans. Non-absorbable suture (NAS), as an alternative to steel wire for patellar fracture fixation [8, 9], offer superior biomechanical fixation strength and stiffness [10, 11].

However, most clinical applications of NAS still rely on Kirschner wires for fixation [4, 8, 9]. When used alone, suture fixation carries a risk of reduction loss over time [12], which may be attributed to knot instability. The Nice knot, a novel sliding, self-locking, double-strand knot, provides secure and stable fixation without loosening upon tightening [13–15]. In previous clinical practice, we have successfully employed the Nice knot to assist in the reduction of comminuted patellar fractures [16]. Although the simple, sliding, and self-stabilizing design of the Nice knot facilitates bone fragment reduction, its application in the fixation of comminuted patellar fractures has not been formally reported.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the intraoperative and early postoperative outcomes of comminuted patellar fractures treated solely with non-absorbable suture fixation via the Nice knot technique.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

We retrospectively reviewed 25 patients who underwent surgical treatment for unilateral comminuted patellar fractures between January 2023 and February 2024. This study was approved by our Institutional Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The inclusion criteria are as follows:

Age ≥ 18 years;

Unilateral, closed, comminuted patellar fracture;

Patellar fractures involving more than three displaced fragments, with fragment displacement of at least 3 mm and an articular step-off of at least 2 mm.

The exclusion criteria are as follows:

Avulsion fracture of bilateral poles of patella;

Severe osteoporosis or combined with other injuries affecting knee joint function;

Incomplete medical records.

Based on these criteria, 25 patients were included in the study and divided into two groups: the NK group (n = 12) and the TB group (n = 13).

Surgical protocol

All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon (YZ.Q) without the use of a tourniquet. In both the TB group and NK group, an anterior longitudinal incision of the knee joint was made to expose the fracture site, followed by reduction of the bone fragments. Satisfactory fracture reduction was confirmed intraoperatively using fluoroscopy.

Surgical procedure for the TB group

In the TB group, two parallel Kirschner wires were inserted longitudinally across the fracture site from the inferior to the superior pole of the patella. A stainless-steel wire was then looped around the K Kirschner wires in a figure-of-eight configuration anterior to the patella and tightened to achieve compression at the fracture site. If additional stability was required, two supplementary Kirschner wires were inserted laterally through the patella and secured with a cerclage wire looped around the patella. Final reduction and fixation were confirmed using intraoperative fluoroscopy, and the incision was closed in layers.

Surgical procedure for the NK group

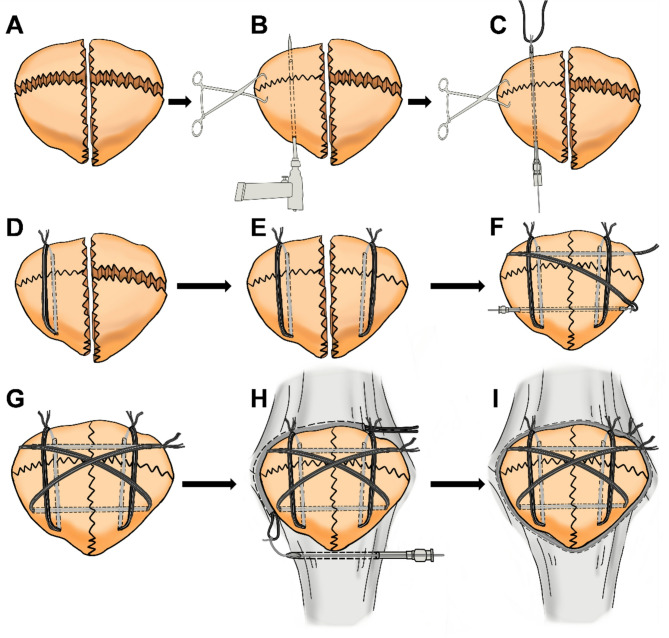

In the NK group, two longitudinal bone channels were created using a 2.0-mm Kirschner wire, positioned similarly to the longitudinally placed wires in the TB group. An abdominal puncture needle measuring 1.8 mm in diameter and 150 mm in length was then inserted into each bone tunnel. The NAS (5-Ethibond, Ethicon), doubled into two strands, was tied with a single knot at its midpoint to a guide wire. After the guide wire was inserted into the abdominal puncture needle, the needle The guide wire was then gently pulled to thread the NAS through the bone tunnel, followed by a firm pull to undo the single knot. The double-strand NAS was subsequently used to perform Nice knot to fix the bone fragments. The position of the knot was adjusted so that it remained in the patellar tendon to avoid skin irritation. Next, two transverse bone tunnels were created using a 2.0-mm Kirschner wire. A double-strand NAS was then passed through these tunnels with the help of a guide wire and secured in a “figure-of-8” configuration using the Nice knot. If additional stability was required, cerclage NAS with the Nice knot was applied. Fluoroscopy was performed again to confirm satisfactory fracture reduction, followed by intraoperative passive knee flexion and extension to assess the stability of the fixation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Surgical diagram of the application of non-absorbable suture fixation via Nice knot for comminuted patellar fractures. A, B, C, D Fixation of Unilateral Comminuted Patellar Fracture with non-absorbable suture fixation via Nice knot. E Fix the other side using the same method. F, G The non-absorbable suture is used to fix the patella with a Nice knot in a “figureof 8” configuration through the horizontal bone channels. (H)(I)Cerclage NAS with the Nice knot is applied to comminuted patellar fractures if necessary

Postoperative management

Surgical time (minutes) was recorded from the initial skin incision to wound closure. Intraoperative blood loss (milliliters) was also documented. Anterior-posterior and lateral radiographs were obtained on postoperative day 2; weeks 3 and 6; and months 3, 6, and 12. Fracture healing was defined by the absence of local pain or tenderness, the ability to walk unassisted, and radiographic evidence of trabecular bone bridging the fracture line [17]. Both groups commenced functional rehabilitation exercises on the first postoperative day, including static quadriceps contractions and straight leg raises. A limited range of knee flexion-extension exercises (0–10°) and ambulation training with a fixed brace were initiated on the first postoperative day. From postoperative day 2 to week 3, straight leg raises and knee flexion-extension exercises (0–30°) were progressively intensified under the supervision of physiotherapists. From postoperative weeks 3 to 6, under physiotherapist supervision, patients performed 60-minute rehabilitation sessions twice daily. Range of motion (ROM) was progressively increased by approximately 5° per day based on individual tolerance, maintaining pain-free or minimal discomfort throughout all exercises. At the 6-week follow-up, all patients were allowed to range the knee freely and walk freely without restrictions. At the final follow-up, knee function was evaluated according to visual analgesic score (VAS), range of motion (ROM) of the knee, and Böstman scales [18]. As previously reported, Böstman’s clinical grading scale included range of movement (3–6 points), pain (0–6 points), work (0–4 points), atrophy (0–4 points), assistance in walking (0–4 points), effusion (0–2 points), giving away (0–2 points), and stair-climbing (0–2 points). All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t-test.

Results

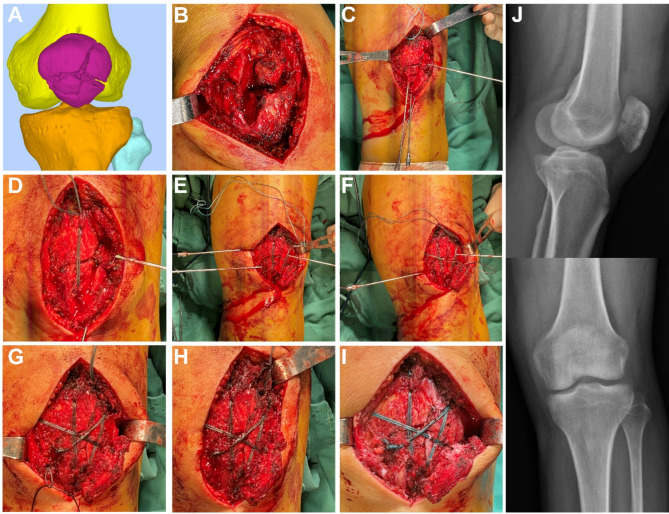

A total of 25 patients with patellar fractures meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Of these, 12 patients underwent Nice knot technique, while the other 13 patients underwent traditional tension band fixation. All patients received operation within 72 h of admission, and all patients were discharged on postoperative day 5. The Fig. 2 depicts a typical surgical case.

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative application of non-absorbable suture fixation via Nice knot for comminuted patellar fractures. A, B Preoperative CT 3D reconstruction and intraoperative photographs indicate a comminuted patellar fracture. C, D Fixation of comminuted patellar fractures on both sides separately. E After establishing two transverse bone channels, fix the patella with a Nice knot in a “figure of 8”. G, H Cerclage wiring is applied to comminuted patellar fracture to enhance stability. I, J Intraoperative photographs and postoperative X-rays demonstrate satisfactory reduction outcomes

Compared to the TB group (89.92 ± 29.36 min, p = 0.57), the intraoperative surgical time in the NK group (96.42 ± 26.18 min) was slightly longer; however, the difference was not statistically significant. The difference in blood loss between the NK group (55.00 ± 36.56 mL, p = 0.63) and TB group (62.31 ± 38.76 mL) was not statistically significant either.

The mean follow-up duration was 16.17 ± 4.11 in the NK group and 15.38 ± 3.12 in the TB group. Both groups of patients achieved bony union within 6 months after surgery. During follow-up, postoperative X-ray demonstrated no cases of fixation failure, indirectly indicating that all surgical knots remained adequately secured. One patient in the TB group developed a wound infection one week after surgery, which was managed with debridement. The wound subsequently healed completely. The Fig. 3 showed a demo case.

Fig. 3.

Peri-operative imaging and functional photographs. A Preoperative X-ray and CT 3D reconstruction indicate a comminuted patellar fracture. B, C Postoperative X-ray and functional assessments at 5 months demonstrate favorable clinical outcomes with satisfactory recovery progress

At the final follow-up, the Böstman scores were 28.08 ± 1.38 in the NK group and 27.54 ± 1.27 in the TB group, with no statistically significant difference (Tables 1 and 2). Likewise, there were no significant differences in VAS scores or ROM between the NK group (VAS: 1.08 ± 0.67; ROM: 121.6° ± 5.4°) and the TB group (VAS: 1.15 ± 0.69; ROM: 120.4° ± 4.48°).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and post-operative follow-up

| Group of NK | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | Age/ Gender |

Time of surgery(min) | Bleeding of surgery(mL) | Last follow up(month) | Böstman scale | Removing internal fixation or not |

| 1 | 62/F | 87 | 20 | 10 | 28 | not |

| 2 | 36/F | 113 | 10 | 14 | 30 | not |

| 3 | 55/M | 120 | 50 | 13 | 28 | not |

| 4 | 56/F | 104 | 100 | 13 | 29 | not |

| 5 | 22/F | 114 | 50 | 17 | 30 | not |

| 6 | 42/M | 129 | 20 | 19 | 29 | not |

| 7 | 69/F | 115 | 100 | 16 | 26 | not |

| 8 | 41/M | 105 | 50 | 15 | 27 | not |

| 9 | 68/F | 75 | 100 | 12 | 26 | not |

| 10 | 52/M | 50 | 100 | 20 | 27 | not |

| 11 | 32/M | 50 | 50 | 22 | 28 | not |

| 12 | 33/F | 95 | 10 | 23 | 29 | not |

Table 2.

Patient demographics and post-operative follow-up

| Group of TB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | Age/ Gender |

Time of surgery(min) | Bleeding of surgery(mL) | Last follow up(month) | Böstman scale | Removing internal fixation or not |

| 1 | 34/M | 148 | 100 | 15 | 29 | yes |

| 2 | 33/M | 67 | 50 | 13 | 30 | not |

| 3 | 60/F | 124 | 100 | 14 | 28 | yes |

| 4 | 42/M | 132 | 100 | 22 | 26 | yes |

| 5 | 40/F | 75 | 50 | 15 | 28 | yes |

| 6 | 37/M | 95 | 100 | 16 | 27 | yes |

| 7 | 77/F | 82 | 10 | 10 | 26 | not |

| 8 | 39/F | 45 | 20 | 18 | 29 | yes |

| 9 | 76/F | 79 | 100 | 14 | 27 | not |

| 10 | 57/F | 85 | 100 | 15 | 26 | yes |

| 11 | 61/F | 80 | 10 | 17 | 28 | yes |

| 12 | 36/M | 97 | 50 | 19 | 27 | not |

| 13 | 66/F | 60 | 20 | 12 | 27 | not |

In the NK group, no patients reported discomfort or irritation related to the internal fixation during follow-up, and all expressed satisfaction with not requiring a second surgery for implant removal. In contrast, five patients in the TB group experienced significant discomfort or irritation caused by the implant. Additionally, eight patients in the TB group underwent secondary surgery for implant removal. Notably, all five patients who reported discomfort had their implants removed at exactly 12 months postoperatively.

Discussion

As the classic fixation method for patellar fractures, tension band wiring converts the tensile forces generated by the extensor mechanism into compressive forces at the fracture site through a “figure-of-eight” configuration.

Two parallel pins are inserted into the patella, and a metal wire is looped in a “figure-of-eight” configuration, passing anterior to the patella and posterior to the pins [4, 19]. In this study, two longitudinal Nice knots served a role similar to that of pins, while the Nice knot tied in a “figure-of-eight” configuration through the horizontal bone channels effectively converted forces. During follow-up, no significant difference in fracture healing time was observed between the TB and NK groups, with all patients achieving bony union within six months postoperatively.

The traditional tension band fixation method typically involves metal implants such as Kirschner wires (K-wires), titanium pins, steel wires, and titanium cables. These implants can lead to skin irritation, discomfort, and an increased risk of infection. Consequently, nearly 60% of patients require a secondary surgery to remove the metal hardware following the initial procedure [20–22]. Using NAS as an alternative to metal implants can solve these problems [12, 23, 24]. In this study, none of the patients in the NK group reported any postoperative infections, nor did they experience significant discomfort or irritation from the internal fixation during follow-up. All patients expressed satisfaction with not requiring a subsequent surgery to remove the fixation implant. In contrast, approximately 38.46% of patients (5 out of 13) in the TB group reported significant discomfort caused by the metal internal fixation implant postoperatively, and one case of wound infection was documented. All five patients who experienced discomfort underwent implant removal within just 12 months after the initial surgery. It is clear that discomfort and irritation caused by metal internal fixation implants significantly affect patients’ daily lives, often necessitating early implant removal. The biomechanical strength and fixation stability of NAS are critical factors in evaluating their suitability as an alternative to steel wire. Studies have demonstrated that NAS offer superior biomechanical strength and stiffness compared to steel wire [10, 11]. However, when NAS is secured with conventional knots, repeated traction forces exerted by the fracture ends during knee flexion and extension can cause the knots to loosen, ultimately leading to internal fixation failure [12]. The Nice knot, a new type of sliding self-locking double-strand knot, can address this issue by preventing loosening during suture tightening, thereby ensuring stable fixation. In clinical practice, we have routinely used the Nice knot for temporary or permanent internal fixation of oblique and spiral diaphyseal fractures and sphenoid bone fragments, which has achieved satisfactory outcomes [25–27]. A previous study demonstrated the effectiveness of the Nice knot in reducing comminuted patellar fractures, achieving excellent intraoperative reduction outcomes [16]. Building on this foundation, the current study further explores the application of the Nice knot for internal fixation of patellar fractures. During surgery, the surgeon routinely performs rapid, repeated maximum knee flexion and extension tests after Nice knot fixation, with no instances of knot loosening observed. As a precaution, patients began gentle, limited-range knee flexion and extension exercises on the first postoperative day, progressing to strengthening exercises at three weeks. All patients achieved satisfactory knee range of motion postoperatively, and no cases of knot loosening or fixation failure were reported during follow-up. Moreover, all fractures demonstrated successful healing outcomes.

Regarding intraoperative conditions, there was no significant difference in blood loss between the two groups, as both had similar incision lengths and exposure ranges. Although the operative time in the NK group was slightly longer than in the TB group, this difference was not statistically significant. The slightly extended duration in the NK group may be attributed to the surgeon’s relative unfamiliarity with the NK fixation technique compared to the more established TB method. This is expected to improve as the surgeon gains greater experience with the NK procedure.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, it is a short-term, retrospective analysis involving a limited number of patients from a single center, which restricts the generalizability of the findings over the short term. Future multicenter randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the findings of this study and to further establish the efficacy and broad applicability of the Nice knot as a reliable internal fixation method for patellar fractures. Secondly, although one case of infection occurred in the TB group and none in the NK group, it remains uncertain whether the use of NAS inherently reduces infection risk—this issue warrants further investigation. Lastly, despite the relatively long follow-up period in this study, even longer-term research is essential to identify potential late complications.

In summary, this study evaluated the intraoperative and early postoperative clinical outcomes of using non-absorbable sutures as the sole internal fixation method for comminuted patellar fractures via the Nice knot technique. Compared to traditional tension band fixation, Nice knot fixation offers several advantages, including reduced soft tissue irritation and discomfort, elimination of the need for secondary implant removal surgery, a potential decrease in postoperative infection rates, and satisfactory fracture healing time and knee joint function. Nevertheless, further studies are warranted to validate these findings across larger patient populations and diverse clinical settings.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- NK

Nice knot

- VAS

Visual Analgesic Score

- ROM

Range of Motion

- TB

Tension Band

- NAS

Non-absorbable Suture

Authors’ contributions

Lian Zeng, Tian Xia and Xinyue Yang prepared the figures and draft the manuscript. Qiankun Xu, Yudong Sun and Chengfeng Li contributed to statistical analysis and data visualization. Hongwei Lu, Wenzhe Sun and Peiran Xue participated in the surgery. Pengqing Zhang and Jianwen Wang conducted clinical follow-up with patients. Yanzhen Qu spearheaded the study design, performed the surgical procedure and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82102546).

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon formal request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (IORG No. IORG0003571). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment, and all data were collected anonymously and processed centrally.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lian Zeng, Tian Xia and Xinyue Yang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Kaufer H. Mechanical function of the patella. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:1551–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huberti HH, Hayes WC, Stone JL, Shybut GT. Force ratios in the quadriceps tendon and ligamentum patellae. J Orthop Res. 1984;2:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sayum Filho J, Lenza M, Tamaoki MJ, Matsunaga FT, Belloti JC. Interventions for treating fractures of the patella in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2:CD009651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinmetz S, Brügger A, Chauveau J, Chevalley F, Borens O, Thein E. Practical guidelines for the treatment of patellar fractures in adults. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh KT, Suh JD, Cho HJ. Open reduction and internal fixation of comminuted patellar fractures with headless compression screws and wiring technique. J Orthop Sci. 2018;23:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lue TH, Feng LW, Jun WM, Yin LW. Management of comminuted patellar fracture with non-absorbable suture cerclage and nitinol patellar concentrator. Injury. 2014;45:1974–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore TB, Sampathi BR, Zamorano DP, Tynan MC, Scolaro JA. Fixed angle plate fixation of comminuted patellar fractures. Injury. 2018;49:1203–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee BJ, Chon J, Yoon JY, Jung D. Modified tension band wiring using fiberwire for patellar fractures. Clin Orthop Surg. 2019;11:244–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noothan PT, Somashekara SA, Sunkappa SR, Karthik B, Rameshkrishnan K. A randomized comparative study of functional and radiological outcome of tension band wiring for Patella fractures using SS wire versus fiberwire. Indian J Orthop. 2023;57:876–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright PB, Kosmopoulos V, Coté RE, Tayag TJ, Nana AD. FiberWire is superior in strength to stainless steel wire for tension band fixation of transverse patellar fractures. Injury. 2009;40:1200–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adjal J, Haugaard A, Vesterby L, Ibrahim HM, Sert K, Thomsen MG, Tengberg PT, Ban I, Ohrt-Nissen S. Suture tension band fixation vs. metallic tension band wiring for patella fractures - A Biomechanical study on 19 human cadaveric patellae. Injury. 2022;53:2749–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camarda L, La Gattuta A, Butera M, Siragusa F, D’Arienzo M. FiberWire tension band for patellar fractures. J Orthop Traumatol. 2016;17:75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudran B, Little C, Duff A, Poon H, Tang Q. Proximal humerus fractures: anatomy, diagnosis and management. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2022;83:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill SW, Chapman CR, Adeeb S, Duke K, Beaupre L, Bouliane MJ. Biomechanical evaluation of the nice knot. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2016;10:15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collin P, Laubster E, Denard PJ, Akuè FA, Lädermann A. The nice knot as an improvement on current knot options: A mechanical analysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:293–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, Jin X, Fryhofer GW, Zhou W, Yang S, Liu G, Xia T. The application of the nice knots as an auxiliary reduction technique in displaced comminuted patellar fractures. Injury. 2020;51:466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CC, Tai CL, Chen WJ. Patellar tension band wiring: a revised technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:12–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Böstman O, Kiviluoto O, Nirhamo J. Comminuted displaced fractures of the patella. Injury. 1981;13:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helfet DL, Haas NP, Schatzker J, Matter P, Moser R, Hanson B. AO philosophy and principles of fracture management-its evolution and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1156–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melvin JS, Mehta S. Patellar fractures in adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar G, Mereddy PK, Hakkalamani S, Donnachie NJ. Implant removal following surgical stabilization of patella fracture. Orthopedics. 2010;33(5):301–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.LeBrun CT, Langford JR, Sagi HC. Functional outcomes after operatively treated patella fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:422–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gosal HS, Singh P, Field RE. Clinical experience of patellar fracture fixation using metal wire or non-absorbable polyester–a study of 37 cases. Injury. 2001;32:129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang Y, Hu J, Zhang P, Zhang J, Yang L, Zhang W, Chen J, He J, Fang Y, Zhou Y, Chen P, Wang J. Clinical application of Kirschner wires combined with 5-Ethibond fixation for patella fractures. Front Surg. 2022;9:968535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu B, Shi L, Ma H, Yu H, Jiang J. Analysis of the efficacy of endobutton plate combined with high-strength suture nice knot fixation in the treatment of distal clavicle fractures with coracoclavicular ligament injuries. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25:927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greco VE, Wiesler E. The Greco-Nice-Lag: lag screw and double nice knot fixation for spiral proximal phalanx Fractures-Connecting the shoulder to the finger. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2024;28:110–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan XL, Wang J, Zhang DH, Mao F, Liao Y. The use of nice knots cerclage to aid reduction and fixation of metacarpal fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148:e338–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon formal request.