Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondrial (ER-Mito) interface, termed mitochondrial-ER contacts (MERCs), plays significant roles in the maintenance of bioenergetics and basal cell functions via the exchange of lipids, Ca2+, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in various cell-types/tissues. Genetic deletion of mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), one of the key components of ER-Mito tethering, in cardiomyocytes (CMs) in vivo revealed the importance of the microdomains between mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), a differentiated form of ER in muscle cells, for maintaining normal mitochondrial Ca2+ (mtCa2+) handling and bioenergetics in the adult heart. However, key questions remain to be answered: 1) What tethering proteins sustain SR-Mito contact site structure in SR-Mito contact sites in the adult ventricular CMs (AVCMs), the predominant cell type in adult heart; 2) Which MERC proteins operate in AVCMs to mediate specific microdomain functions under physiological conditions; 3) How is the MERC protein expression profile and function altered in cardiac pathophysiology. In this review, we summarize current knowledge regarding the structure, function, and regulation of SR-Mito microdomains in the heart, with particular focus on AVCMs, which display unique membrane organization and Ca2+ handling compared to other cell types. We further explore molecular mechanisms underpinning microdomain dysfunction in cardiac diseases and highlight the emerging roles of MERC proteins in the development and progression of cardiac pathology.

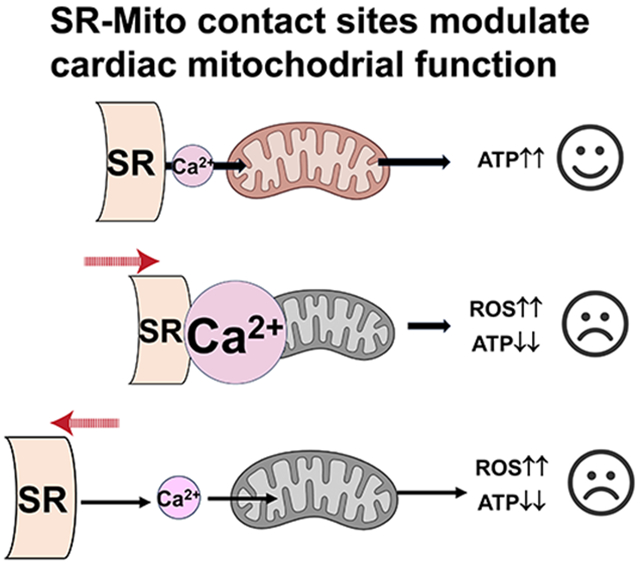

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Mitochondrial function is modulated by physical interactions with other organelles, such as the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR), peroxisomes, and nucleus (95, 114). Among these, the structural and functional significance of ER/SR-mitochondrial (ER/SR-Mito) interface, termed mitochondrial-ER contacts (MERCs), is well established (2, 89, 96). By virtue of their proximity to Ca2+-release sites on the ER/SR (e.g., inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptors [IP3Rs]) and ryanodine receptors [RyRs]), mitochondria at ER/SR-Mito contact points are exposed to elevated Ca2+ concentrations that promotes efficient Ca2+ uptake, thereby regulating ATP synthesis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (2, 89) in various cell types/tissues, including cardiomyocytes (CMs)/hearts. In addition to Ca2+ handling, these contact sites also mediate lipid and ROS exchange, which are critical for the maintenance of mitochondrial bioenergetics (2, 89). Genetic ablation of mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), a key tethering component of ER/SR-Mito contacts, in CMs revealed the importance of the microdomains between mitochondria and SR, a differentiated form of ER in muscle cells, for normal mitochondrial Ca2+ (mtCa2+) handling and bioenergetics in the heart (13, 41, 86, 93). However, several questions remain: 1) What additional MERC proteins have a structural role at contact sites in the heart beyond Mfn2? 2) Which signaling pathways regulate Ca2+, lipid, and ROS at the ER/SR-Mito microdomains during cardiac stress? and 3) How are processes altered in cardiac disease, and what are the downstream effects on mitochondrial and cardiomyocyte (CM) function?

Here, we provide an overview of recent reports on the structural and molecular basis of MERC functions, particularly in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes (AVCMs). As the primary drivers of cardiac contractile force AVCMs exhibit a unique structure characterized by a highly developed network of transverse tubules (T-tubules) that deeply invaginate the plasma membrane, to facilitate efficient electrical signal transmission and coordinated contraction throughout the ventricular muscle in the adult heart (77). Because MERC structure and functions in AVCMs differ significantly from other cell types (see section 2), we attempt to specifically emphasize studies conducted in AVCMs and in vivo animal models rather than the observations and perspectives from non-CMs and CM model cells such as neonatal CMs and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived CMs (see recent reviews (28, 59, 64, 65)).

2. Molecular identity of ER/SR-Mito tethering in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes

In mammalian AVCMs, the predominant cell type in the heart, mitochondria are the most abundant intracellular organelles, numbering in the range of ~ 7000 per cell and occupying up to 35% of the cell volume(106). At least three distinct subpopulations of mitochondria are recognized in AVCMs: interfibrillar, subsarcolemmal, and perinuclear, each distinguished by characteristic morphology and localization (45, 52). Interfibrillar mitochondria, aligned in longitudinal rows between myofibrils, lie in close proximity to the SR. Unlike the ER found in non-muscle cells, the SR in cardiomyocytes is highly specialized for Ca2+ cycling and excitation-contraction coupling (78). Consequently, most MERCs in AVCMs are formed by the interaction between interfibrillar mitochondria and junctional SRs located at the Z-bands. This unique spatial arrangement of interfibrillar mitochondria enables privileged signaling crosstalk between the SR and mitochondria, including Ca2+, ROS, redox, and pH cascades. Other mitochondrial subpopulations, subsarcolemmal and perinuclear mitochondria are less organized and show variability in morphology. The perinuclear rough ER (76) may also form close contacts with perinuclear mitochondria, contributing to multiple alternative MERC subtypes as shown in dog AVCMs (121).

In large animals, a single mitochondrion or two interfibrillar mitochondria with relatively uniform size and shape typically span a single sarcomere from Z-band to Z-band (30, 90). However, the number of mitochondria residing between the Z-bands is greater in rodents, often two or more mitochondria (16, 81, 90), which provides various-sized and shaped interfibrillar mitochondria. Consequently, the MERC functions in AVCMs, especially in the interfibrillar mitochondria, may differ between species. Given potential differences, in this review, we explicitly state the species used in referenced works in this review.

Several ER-mitochondrial tethering complexes have been characterized in non-CMs (see reviews (34, 116, 119)), typically consisting of an ER-resident protein and an outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) resident protein. Key examples include: 1) Mfn2-Mfn1/Mfn2 homo/heterotypic complexes, 2) IP3R-voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC) complex mediated by the chaperone glucose regulated protein 75 (GRP75), 3) vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB)-protein tyrosine phosphatase-interacting protein 51 (PTPIP51) complex, and 4) protein B-cell receptor-associated protein 31 (Bap31)-mitochondrial fission protein Fission 1 homologue (Fis1) complex. Additionally, the ER-membrane protein PDZ domain-containing protein 8 (PDZD8) has been proposed as part of the ER-Mito tethers in neurons. However, the mitochondrial counterpart of PDZD8 remains unidentified in any cell type, and the function of PDZD8 in MERCs has not been investigated in the heart (Table 1).

Table 1.

Protein expressions of potential SR/ER-Mito tethering proteins in the adult hearts

| Protein/gene name |

Subcellular location |

Protein expression in human hearts |

Protein detection in MAM mass spec in rat hearts |

Reports on AVCMs/hearts related to ER/SR-Mito tethering function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mfn2 | SR/ER, OMM | Medium | Yes | (13, 41, 86, 93) |

| Mfn1 | OMM | Not Detected | Yes | (13, 88) |

| VAPB | SR/ER | Medium | Yes | |

| PTPIP51 | OMM | Medium | No | (92) |

| IP3R1 | SR/ER | Low | No | (86) |

| IP3R2 | SR/ER | Medium | No | |

| IP3R3 | SR/ER | Medium | No | |

| GRP75 | Cytoplasm | High | Yes | (86) |

| VDAC1 | OMM | Medium | Yes | (86) |

| VDAC2 | OMM | High | Yes | (113) |

| VDAC3 | OMM | High | Yes | |

| DJ-1 | Cytoplasm | Low | Yes | |

| FUNDC1 | OMM | Medium | Yes | (113) |

| Bap31 | SR/ER | Not Detected | Yes | |

| Fis1 | OMM | High | Yes | |

| PDZD8 | ER | medium | No |

According to the Human Protein Atlas (109), most of the proteins listed above are detectable in adult human heart tissues and CMs (Table 1). Furthermore, quantitative proteomic analysis using mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM)-enriched fractions from adult rat hearts detected most of the candidates of the tethering proteins (68) (Table 1). In the following sub-sections, we summarize recent reports on the tethering structural proteins in CMs/ heart tissue, with particular attention to the Mfn2-Mfn1/Mfn2 complex, the IP3R-GRP75-VDAC complex, and the VAPB-PTPIP51 complex in AVCMs. To date, there are no reports specifically investigating the roles of Bap31, Fis1, and PDZD8 in SR-Mito tethering in AVCMs/ heart tissue (Table 1).

2.1. Mfn2-Mfn1/Mfn2 complex:

While the IP3R-GRP75-VDAC complex was the first proposed ER-Mito tethering structure (107), predating the discovery of Mfn2 dimers (21), Mfn2 is now recognized as the most extensively studied tethering complex in rodent and human AVCMs and cardiac tissues (Table 1). Studies using CM-specific Mfn2 knock-out (KO) mice have demonstrated that Mfn2 is a critical determinant of the physiological morphology of SR-Mito microdomains as well as in the maintenance of normal mtCa2+ handling and bioenergetics in the adult heart (13). In non-CMs, ER-located Mfn2 can form homodimers (Mfn2-Mfn2) or heterodimers with OMM-localized Mfn1 (21, 83). However, in adult mouse hearts, CM-Specific Mfn1 KO does not significantly affect the size of SR-Mito microdomains (13, 88). These observations suggest that the Mfn2 homodimers play a more dominant role than Mfn2-Mfn1 heterodimers in maintaining SR-Mito contacts under physiological conditions (13, 88). Supporting this, Mfn1 expression in human heart tissue is markedly lower than Mfn2 (or reported as “not detectable” in Human Protein Atlas, see Table 1). Interestingly, despite this, Mfn1 expression level has been proposed as a biomarker for heart failure (HF) in non-responding patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy(47). This suggests a potential pathological role for Mfn1, though further studies are needed to clarify its function within MERCs in human cardiac disease. Although Mfn2 is widely considered a tethering protein, several controversial studies in non-CMs have shown that Mfn2 deletion increases ER-Mito coupling (15, 32, 56) (see also a review (33)). In the AVCMs, Walsh’s group similarly reported no significant change in SR-Mito contact site size following KO of Mfn2 in mice (88). These discrepancies may result from differences in KO/KD strategies, experimental models (i.e., in vitro vs. in vivo), or imaging and analysis techniques. Nevertheless, even when differences are observed, the reported changes in the ER/SR-Mito distance Mfn2 KO or KD are relatively modest, falling within 15-18 nm range (13, 21), suggesting that Mfn2 likely fine-tunes rather than determines the SR/ER-Mito distance. Given that Mfn2 also plays a canonical role (i.e., OMM fusion), it remains unclear whether and how Mfn2 regulates the MERCs via tethering-independent mechanism. Further mechanistic studies beyond gene deletion or KD approaches are needed to dissect Mfn2’s diverse functions in AVCMs.

2.2. IP3R-GRP75-VDAC complex:

Glucose regulated protein 75 (GRP75), a product of the HSPA9 gene, also known as Mortallin, PBP74, and mitochondrial HSP70 (mtHSP70) was initially identified as a molecular chaperone that functionally links the metabolic flow, Ca2+, and cell death signaling between the ER and mitochondria by physically connecting VDAC isoform 1 (VDAC1) at the OMM with ER Ca2+-release channels, IP3Rs (107). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments by De Stefani and Rizzuto’s group demonstrated that GRP75 interaction is isoform-specific: GRP75 forms a complex with VDAC1, but not VDAC2 and VDAC3(25). These data support the role of VDAC1 as the primary conduit for Ca2+ transit among the VDAC isoforms involved in intrinsic apoptosis (25). Additionally, they showed that at least two IP3R isoforms, IP3R1 and IP3R3, can bind to GRP75 (25). Given the high sequence homology among the three IP3R isoforms (35) and evidence that all three are required for maintaining ER-Mito contact sites independent of their role in Ca2+ flux (3), it is plausible that IP3R2 can also associate with GRP75 to form a tethering complex. In adult heart tissues, IP3Rs, GRP75, and VDACs are all expressed, although expression levels of VDACs vary among the isoforms (see Table 1). In mouse AVCMs, the presence of an IP3R1-GRP75-VDAC1 complex likely exists since the association of IP3R1, GRP75, and VDAC1 was detectable by immunoblotting with subcellular fractionated proteins from mouse hearts (86) (Table 2). While IP3R-, GRP75-, and VDAC-KO mice have been generated, there are no published studies examining whether any structural and functional alterations in SR-Mito contact sites occur in the hearts of these animals. Interestingly, DJ-1, a protein originally linked with autosomal recessive early-onset Parkinson’s disease, has been proposed as one of the regulators of the IP3R3-GRP75-VDAC1 complex (63). DJ-1 has also been reported to exert cardioprotective effects under various pathological stress conditions(29, 102, 103). However, whether these effects are mediated via the modulation of the IP3R-GRP75-VDAC1 complex in AVCMs remains unclear.

Table 2.

Proteins associated with SR-Mito Ca2+ transport in adult ventricular myocytes (AVCMs)

| Protein | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RyR2 | SR | |

| SERCA2a | SR | |

| phospholamban (PLB) | SR |

|

| sarcolipin (SLN) | SR |

|

| IP3Rs | SR | |

| MCU | IMM | |

| EMRE | IMM |

|

| MICUs | IMM |

|

| VDACs | OMM |

|

| NCLX | IMM |

|

FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1) is a highly conserved OMM protein that can bind to IP3R2 in neonatal CMs to modulate ER Ca2+ release (113). Importantly, FUNDC1 is also required to maintain the integrity of MERC structures (113) (Table 1). Since FUNDC1 KO mice showed significant alterations in mitochondrial morphology and oxygen consumption rate, further studies are needed to precisely understand whether the effects of FUNDC1 on MERC structures are mediated via the Ca2+-flux of IP3R2, alterations of mitochondrial morphology, and/or structural changes in the IP3R-GRP75-VDAC tether complex. In summary, all the components of the IP3R-GRP75-VDAC complex and its regulatory proteins are expressed in the adult heart. However, the relative contribution of the IP3R-GRP75-VDAC complex and Mfn2 dimers (see section 2.1) to SR-Mito tethering in AVCMs is still unknown.

2.3. VAPB-PTPIP51 complex:

Vesicle-associated Membrane Protein-Associated Protein B (VAPB) is part of the VAMP-associated protein family and is a key player for facilitating tethering at membrane contact sites between the ER and other intracellular membranes such as mitochondria or plasma membrane (47). So far, investigation on the roles of VAPB in CMs is still in its early stages (73, 104). To date, no reports show the specific role of VAPB in the formation of ER/SR-Mito contact sites and its contributions to the MERC functions in the CMs (Table 1). A single report showed that at least its binding partner PTPIP51, also known as RMDN, may regulate SR-Mito physical contact sites in the mouse AVCMs (92) (Table 1); PTPIP51 KD has been shown to decrease SR-Mito contacts in mouse hearts in vivo, suggesting the potential existence of the VAPB-PTPIP51 complex in the SR-Mito contact sites in AVCMs.

3. SR-Mito contact-site proteins and their biological functions in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes

ER-Mito microdomains play crucial roles in the exchanges of Ca2+ and lipid as well as the hubs for cellular signaling pathways that impact processes such as autophagy, apoptosis, inflammasome formation, and metabolic modulation (2, 7, 18, 38, 89, 94, 96). These functions are orchestrated by diverse proteins enriched within the MERC regions. A recent quantitative proteomics study identified 1871 proteins in the MAM fractions from adult rat hearts (68), most of which are presumably from SR-Mito contact sites of AVCMs. Among them, 216 proteins were previously reported as “consensus MAM proteins”. Notably, in cardiac MAMs, mitochondrial proteins were the predominant subcellular contributors. In contrast, in other tissues, such as the liver, brain, and testis, ER-resident proteins were the largest group (68). These findings suggest that SR-Mito contact sites in AVCMs differ significantly from ER-Mito contact sites in other cell types in both structure and function. Proteins identified in cardiac MAMs spanned a range of functional categories (from most to least abundant): Metabolism (e.g., ATP bioenergetics and lipid metabolism), organelle organization (e.g., mitochondrial fission/fusion), signaling (e.g., apoptosis and immune response), post-translational modification (e.g., phosphorylation and dephosphorylation), transport (e.g., vesicle and cation transport), and autophagy.

To date, the most thoroughly investigated MERC function in AVCMs is Ca2+ handling, which is central to excitation-contraction-metabolism coupling in the heart (see reviews (24, 111, 120)). This has been dissected using in vivo knockout (KO) and knockdown (KD) mouse models targeting specific Ca2+-handling proteins (see Table 2). As outlined in Section 2, mitochondrial dynamics proteins, notably Mfn1 and Mfn2, have also been shown to modulate SR-Mito contact sites in AVCMs. In addition, several studies have begun to explore the consequences of KO/KD of lipid metabolism-associated proteins at SR-Mito interfaces. In this section, we overview the recent reports that investigated two MERC functions in AVCMs, Ca2+ and lipid transport. Although other potential MERC functions, such as bioenergetics, apoptosis, immune response, and autophagy, are of great interest, they are hampered by an extremely limited number of publications assessing these functions in the context of SR-Mito contact sites of AVCMs. Therefore, these MERC functions and their potential relationship with cardiac physiology and pathology will be discussed in the following sessions as a perspective.

3.1. Ca2+ transport:

We previously showed the first indication of the existence of Ca2+ communication between SR and mitochondria through the SR-mitochondrial microdomain in CMs; the application of Ca2+ chelator 1,2-Bis(2-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) to the cytosol in saponin-permeabilized CMs was able to suppress the global cytosolic Ca2+ transient but not the mitochondrial Ca2+ transient following rapid caffeine-induced SR Ca2+ release, demonstrating the privileged communication between SR and mitochondria that relies upon local communication at the micrometer scale (100). Similarly, Maack’s group demonstrated SR-Mito Ca2+ transport in the intact AVCMs after the physiological SR Ca2+ release by L-type Ca2+ channel activation (51).

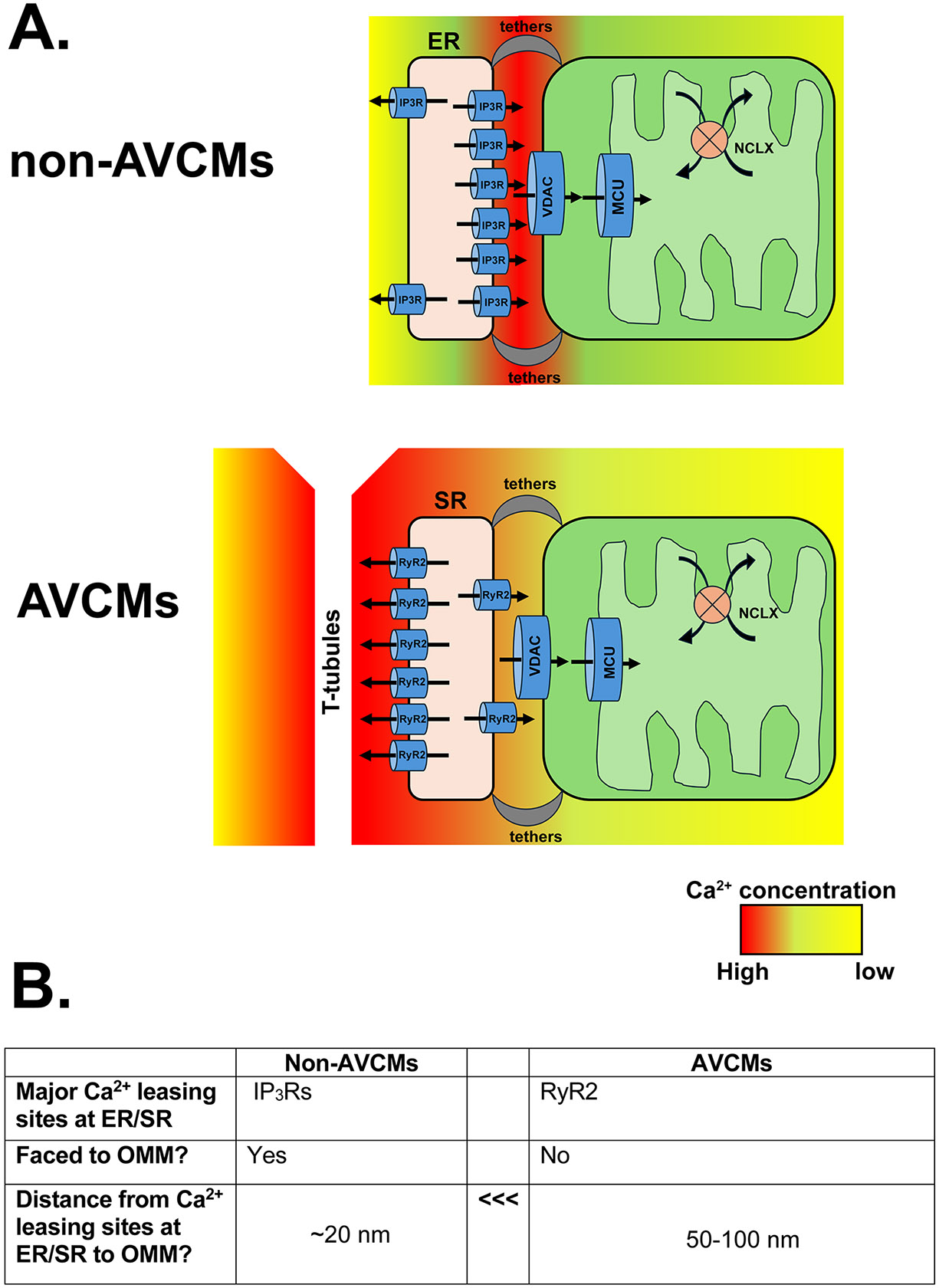

In non-CM cells, it is widely established that IP3Rs, the major Ca2+ release units at the ER membrane, face toward ER-Mito contact sites and are involved in Ca2+-mediated crosstalk between ER and mitochondria (26) (Fig. 1A, left); The IP3Rs release Ca2+ from ER lumen to the ER-Mito interface where microdomains of Ca2+ reach concentrations of 10–30 μM (17). This Ca2+ flows into the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) via VDACs at the OMM, then crosses the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) through pores created by the mtCa2+ uniporter (MCU)-protein complex (mtCUC) at the IMM into the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 1A, left).

Fig. 1. Structural difference in Ca2+ transport system at MERCs in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes (AVCMs) and non-AVCMs.

A. Schematic diagrams of MERC Ca2+ transport system in non-CM (top) and AVCMs (bottom). Major Ca2+ releasing units of ER (i.e., IP3Rs) face towards mitochondria, whereas major Ca2+ releasing unit of SR (i.e., RyR2) face towards T-Tubules. The Ca2+ concentration after the ER/SR Ca2+ release was shown as heat maps. Distributions of MCU and NCLX within the mitochondria in AVCMs are simplified, and the SR-Ca2+ uptake system is abbreviated (see details in Section 3.1). B. Summary of the key differences in the structural MERC Ca2+ transport system in AVCMs and non-CMs.

In AVCMs, beat-to-beat Ca2+ release from junctional SR occurs almost exclusively via ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2) and not from the IP3Rs (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the majority of RyR2s were localized along the T-tubule side of the SR rather than the SR-Mito microdomains (Fig. 1A, right and 1B) (36, 71). Indeed, this unique localization of RyR2s at junctional SR tightly controls Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) in CMs (4), but high local concentrations of Ca2+ after CICR in the microdomains between the T-tubule membrane and SR should diffuse near OMM to trigger mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via VDACs and mtCUC. However, the actual exposure time to high local Ca2+ concentrations (10-20 μM) at MERCs, that can trigger mtCa2+ uptake via mtCUC (50), might be quite brief (i.e., approximately 10 ms) (112). Moreover, the mtCUC channel conductance from adult mouse hearts is extremely small compared to that from other organs (31). Therefore, Lederer’s group proposed that physiological mtCa2+ uptake via mtCUC during the heartbeats is small and inherently inefficient due to the greater distance from RyR2 at junctional SR to the OMM (50–100 nm) compared to that from IP3R at ER to the OMM in non-CMs (~20 nm) (91), thus does not significantly impact any global Ca2+ handling profile in AVCMs (112) (Fig. 1B). However, we previously demonstrated biased localization and subunit composition of mtCUC complexes at the SR-Mito contact sites: the EMRE-containing mtCUC is preferentially expressed at the MERC area rather than other IMM areas that do not face junctional SR (22). This specialized mtCUC distribution may compensate for the spatial (i.e., RyR2-OMM distance) and functional (i.e., low mtCUC channel conductance) disadvantages and facilitate effective Ca2+ transfer from SR to mitochodnria. Furthermore, cardiac mitochondria are relatively deficient in the mtCUC component MICU1, conveying enhanced sensitivity to low cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations(43). In contrast to specialized mtCUC distribution at MERCs in the AVCMs (22), we also reported that mitochondrial Ca2+ extrusion via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCLX) is excluded from IMM regions facing the junctional SR-Mito contact sites (23). These asymmetries in the localization of Ca2+ uptake and extrusion machinery may enhance mtCa2+ handling at minimal energetic cost. While our idea is based on functional, biochemical, and imaging assays, Bers’s group reported relatively uniform MCU distribution over the mitochondrion in the rabbit AVCMs (66). Takeuchi and Matsuoka reported that NCLX is preferentially localized in MERC area in mouse AVCMs (108). This discrepancy may reflect species differences and/or the different methodologies selected, but further computational modelling is needed to establish whether efficient mtCa2+ influx/efflux is driven by geometric positioning or specialized MERC organization as we propose.

Although mass spectrometry and MAM Western blotting have detected RyR2 in cardiac MAM fractions (68, 74), its expression is likely much lower than that in T-tubule side, as shown in the studies using electron microscopy (36, 71). One possibility is that a small RyR2 subset residing in the MERCs formed by junctional SRs and interfibrillar mitochondria contributes to localized Ca2+ release at the MERCs. Indeed, there are several reports suggesting the functional coupling of RyRs and VDAC2 in the mouse and zebrafish hearts (98, 101) and physical interactions between RyR2 and VDAC2 at MERCs were shown in the rat neonatal CMs (79). However, due to the limited number of RyR2 within the MERCs formed by junctional SR and interfibrillar mitochondria in the AVCMs, further studies are required to precisely determine whether this small number of RyR2 facing OMM has a significant impact on the junctional SR-Mito Ca2+ transport. Moreover, as suggested by Kim’s group, these RyR2-VDAC2 interactions exist only in the specific population of mitochondria, such as subsarcolemmal mitochondria, but not in interfibrillar mitochondria (79).

Another possibility is that RyR2 expressed at the networked SRs, which reside between the Z-lines and interacts significantly with interfibrillar mitochondria (71), may provide an additional and faster Ca2+ transport pathway to the OMM of interfibrillar mitochondria. This specific population of RyR2 could contribute to propagating CICR (70), but the relative contribution to mtCa2+ transport in interfibrillar mitochondria remains unclear.

In addition to the main SR Ca2+ releasing channel RyR2, Dedkova and Ritter’s group showed that all three isoforms of IP3Rs are expressed in the mouse AVCMs, and Gq protein-coupled receptor stimulation can trigger the Ca2+-release from SR via these IP3Rs, promoting mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (99). While the localization of IP3R at the MERCs in AVCMs remains to be directly confirmed, these data suggest that IP3Rs-dependent Ca2+ transfer may contribute to SR-mitochondrial signaling outside of the beat-to-beat context.

In summary, there are three potential Ca2+ releasing pathways from SR pathways that underlie Ca2+ transfer to interfibrillar mitochondria in AVCMs: 1) limited localization of RyR2 at MERCs formed by junctional SRs, 2) RyR2 expressed at the network SR, and 3) the IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release at MERCs. Additionally, we also need to take into consideration that the activity of SR/ER Ca2+-ATPases (i.e., Ca2+ uptake into SR) is capable of modulating the amplitude and the speed of the Ca2+ elevation and reduction within the MERC region (91). Indeed, SERCA2a and its regulatory protein phospholamban were detected from adult mouse hearts (40, 74) (Table 2). Future studies are needed to define how these spatial and molecular mechanisms integrate into the broader Ca2+-signaling landscape of the AVCMs.

3.2. Lipid transport:

Cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol are mitochondria-specific phospholipids that are synthesized within mitochondria (46). Among these, cardiolipin, a critical regulator for mitochondrial respiration (96), exists in its highest concentrations in the heart, reflecting the organ’s high oxidative demand. Mitochondria can also synthesize phosphatidylethanolamine (46). However, to synthesize these lipids, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, and sterols must be imported from neighboring organelles, including ER. For optimal Lipid transport, ER-Mito contact distance needs to be around 10 nm, a size shorter than the efficient Ca2+ transport from IP3Rs (39). Recent studies showed that MERCs possess multiple lipid-synthesizing enzymes and transport machinery (see review (96)). Many of these enzymes and transport proteins are also detectable in MAM proteomes, including those from adult rat AVCMs (68).

Among MERC-localized tethering proteins, Mfn2 and PTPIP51 have emerged as critical regulators of lipid metabolism in addition to their structural roles (see Section 2). Specifically, Mfn2 facilitates the transfer of phosphatidylserine and PTPIP51 phosphatidic acid from ER to mitochondria, respectively (44, 117). Although CM-specific KO and KD of Mfn2 and PTPIP51 in mice have been tested (see section 2), it has not been precisely investigated whether any changes in the lipid metabolism in AVCMs occur after the ablation of Mfn2 or PTPIP51. Given a lipid overload-induced dysfunction of cardiac mitochondria (49), lipid metabolism at MERCs in AVCMs may play a critical role in maintaining bioenergetics and membrane integrity in cardiac mitochondria.

4. Role of SR-Mito contact sites in cardiac pathophysiology

As shown above, recent research in non-CM cells highlighted the significance of MERCs in the various critical cellular processes under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. As we described in the above section, MERC functions in non-AVCMs and AVCMs should have critical differences such as mtCa2+ homeostasis, because major MERCs in AVCMs are the SR-Mito contact sites (i.e., not ER-Mito). These structural and functional differences in AVCMs may also provide unique contributions to the development and progression of cardiac pathophysiology.

4.1. Ischemic/reperfusion injury:

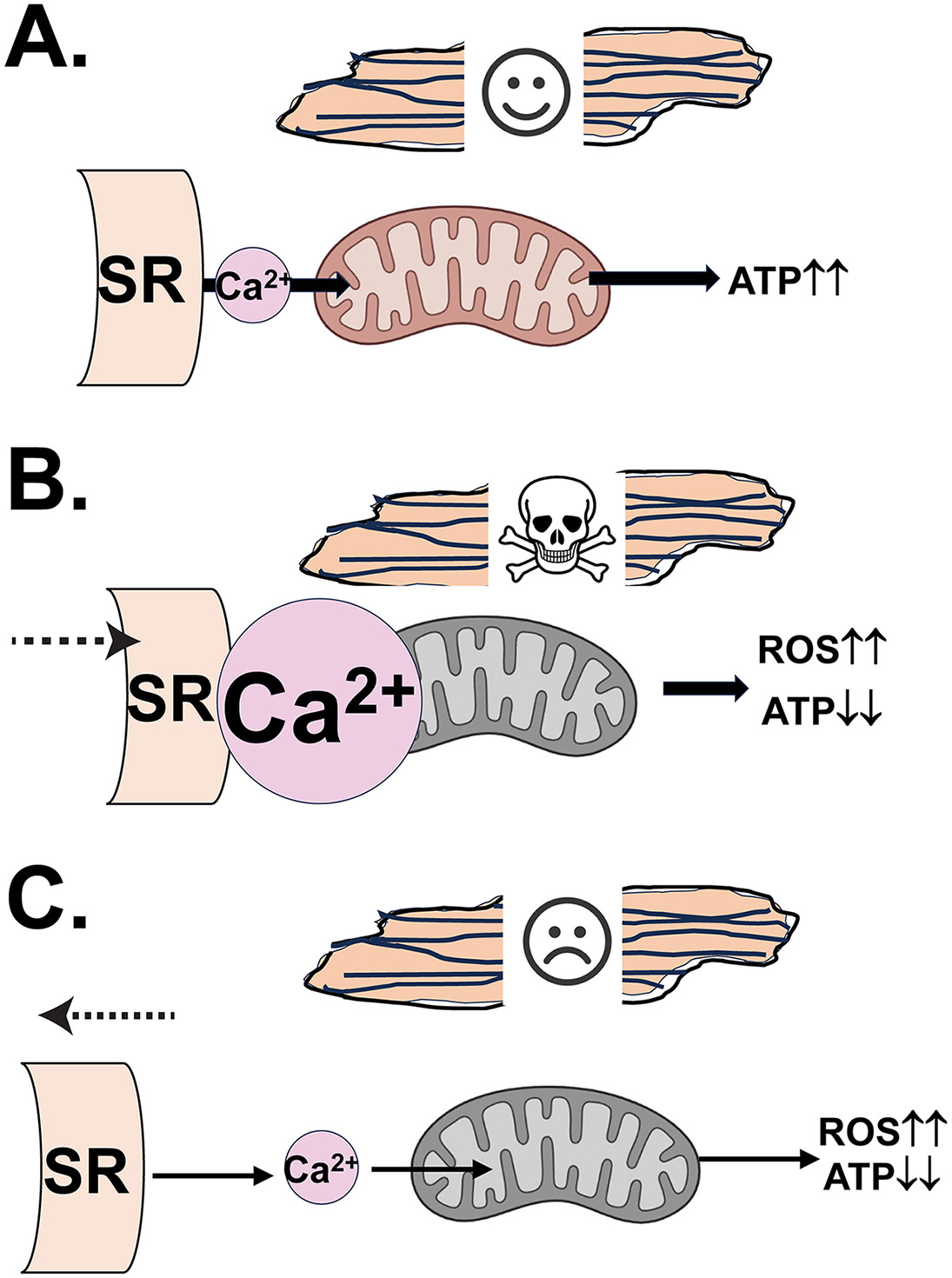

Although it is still controversial whether basal Ca2+ concentration at the mitochondrial matrix is involved in maintaining basal bioenergetics in the AVCMs (37, 61, 111), physiological mtCa2+ loading via mtCUC is required for the "fight-or-flight" response that enables the heart to match its workload with ATP production during adrenergic stimulation (53, 72) (Fig. 2A). The size and organization of SR-Mito contact sites is critical for this response. For instance, Mfn2 KO in AVCMs blunts bioenergetic response against the cytosolic Ca2+ elevation after β-adrenoceptor stimulation, indicating that proper SR-Mito architecture is necessary for efficient mtCa2+-mediated metabolic coupling (13). (Fig. 2A). The mtCa2+ overload via mtCUC and subsequent opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), ROS generation, and apoptotic signaling activation are well-established phenomena, especially under ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) (37). Ramasam’s group showed that under I/R stress, SR-Mito distance becomes significantly shorter, which exacerbates mitochondrial Ca2+ overload (118) (Fig. 2B). They also found that a canonical effector for Rho small GTP-binding proteins, diaphanous-related formin 1 (DIAPH1) is overexpressed during I/R, whereupon it binds to Mfn2, which modulates SR-Mito distance, mitochondrial turnover, mitophagy, and oxidative stress (85, 118); Strikingly, cardiac specific DIAPH1 KO increases SR-Mito distance without impacting the basal cardiac function, and promotes AVCMs to be protected against I/R injury (118). This observation suggests that a significant decrease in SR-Mito distance is detrimental to cardiac stress, such as I/R. Indeed, Ovize’s group also showed that inhibition or deletion of the regulatory proteins for IP3R-GRP75-VDAC complex protects AVCMs from hypoxia-reoxygenation injury, passively via modifying in the amount/size of SR-Mito microdomains (40, 86). In line with this idea, we also tested the impact of enhancing the SR-Mito interaction by the cardiac-specific introduction of synthetic linker construct in vivo (84). However, synthetic linker expression does not impact on the overall cardiac function or promote mitochondrial Ca2+ overload-mediated apoptotic signaling activation despite the changes in SR-Mito contact site morphology. This result, combined with the report of the basal cardiac function of DIAPH1 KO mice (118), suggests that chronic alterations of SR-Mito distance in the adult hearts may not affect the basal cardiac functions, possibly via an adaptive, compensatory mechanism. (84). Nevertheless, integrated SR-Mito structures are essential during prenatal cardiac development, and disruptions in MERC structure during this period are known to cause severe defects (14)

Fig. 2. Structural alterations of SR-Mito microdomains in the adult ventricular cardiomyocytes and their potential impact on the cardiac functions under pathophysiological conditions.

A. Physiological mtCa2+ loading via SR-Mito microdomains and mtCUC is required for the "fight-or-flight" response that enables the heart to match its workload with ATP production. B. The mtCa2+ overload via cytosolic Ca2+ elevation and narrowed SR-Mito contact sites under I/R promotes mitochondrial depolarization, ROS generation, mPTP opening, and apoptotic signaling activation. C. The mtCa2+ reduction due to the wide SR-Mito contact sites in heart failure causes lower ATP production and higher mitochondrial ROS generation.

4.2. Heart failure:

Chronic HF is the leading cause of mortality in cardiovascular disease (8). It is characterized by both structural remodeling (e.g., detubulation and myofilament degradation) (57, 97) and transcriptional changes, including the reactivation of fetal gene expression profiles(75). As described in Sections 2 and 3, SR-Mito tethering structures and MERC proteins facilitate communication between these organelles and regulate various cellular processes critical for AVCM functions.

Recently, co-existence of HF and increased SR-Mito distance (and/or decrease in the amount/size of contact sites) was reported in the animal models (19, 113) (Fig. 2C). However, the investigation of the MAM protein expression profiles in the human HF has just begun, and the information is still limited. Using topographic electron microscopy analysis and human AVCMs isolated from the ischemic, ischemic-dilated, and dilated cardiomyopathy patient hearts. Elrod’s group recently reported a significant increase in the SR-Mito distance compared to those from nonfailing control hearts (55) (Fig. 2C). Moreover, like HF animal models (19, 113), Elrod’s group also showed decreased expression of the major tethering proteins in failing hearts compared to controls, suggesting that SR-Mito tethering structure is likely diminishing under human HF (55). Increased SR-Mito distance can lower the Ca2+ concentration at the mitochondrial matrix, which impairs heart function by decreased ATP production and higher ROS production (42, 62, 105) (Fig. 2C).

Cardiac hypertrophy, often a precursor to non-ischemic HF, further illustrates dynamic MERC remodeling. During early hypertrophy, AVCMs increase their expression of MAM proteins, followed by a progressive decline as the disease advances (69). This suggests that loss of tethering proteins may contribute to the transition from compensatory hypertrophy to HF. However, cardiac-specific KO of Mfn1/2 or PTPIP51 itself does not lead to overt HF, despite mild dysregulation of mitochondrial bioenergetic impairments. (13, 41, 92). These findings imply that loss of SR-Mito contacts alone is insufficient to cause HF in the adult heart but may facilitate or exacerbate disease progression under stress conditions(19, 113). Nevertheless, further studies are needed to precisely understand whether MERC remodeling initiates HF pathogenesis or occurs as a secondary consequence of broader structural and metabolic changes. A detailed understanding of MERC involvement in adaptive vs. maladaptive remodeling will help clarify its role in HF.

4.3. Diabetic cardiomyopathy:

Diabetic cardiomyopathy, a major complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus, is frequently associated with Ca2+ signaling abnormalities in AVCMs (1, 90). HF patients with diabetes experience worse clinical outcomes, including a higher risk of mortality and hospitalization compared to those without diabetes (87). Understanding the cellular mechanisms of unique diabetic cardiomyopathy is therefore essential for the development of targeted therapy. Importantly, weighted gene co-expression network analysis showed that MERC-related genes were clustered into a module correlated with diabetic cardiomyopathy (69), suggesting the critical link between MERC protein expression and SR-Mito communication in disease progression. In a high-fat, high-sucrose diet mouse model, Paillard’s group reported a significant increase in the number of tighter interacted SR-Mito contact sites (less than 10 nm) in AVCMs compared to control animals (27). Such tight organelle associations facilitate lipid transport but may impair efficient Ca2+ transport from IP3Rs to mitochondria in non-CMs (39). Moreover, the normalization of the size of SR-Mito contact sites with the genetic introduction of an artificial tethering construct rescued the abnormality in the mtCa2+ homeostasis and bioenergetics, underscoring the consequences of SR-Mito remodeling (27). Challenges in this field are as follows: 1) lack of evidence of SR-Mito contact sites in human diabetic cardiomyopathy (i.e., whether the alteration trend in human is similar direction with the animal model or not), 2) identifying the SR-Mito distance that produces most efficient Ca2+ transport to the mitochondria specifically in the AVCMs since the major SR Ca2+ releasing sites in AVCMs is RyR2 (see section 3), 3) understanding the relative contribution of MERC changes and global mitochondrial morphology changes (48). Lastly, clarifying the exact SR-Mito distance suitable for lipid transport in AVCMs is particularly important to understand the pathology of lipid overload-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in the heart. Answering these questions will enhance the understanding of how MERC remodeling contributes to diabetic cardiac pathology and may reveal therapeutic targets to restore mitochondrial function in this context.

4.4. Cardiomyopathy associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy:

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) frequently exhibits cardiomyopathy. Babu’s group discovered overexpression of sarcolipin (SLN), a potent inhibitor of the SERCA pump, in the ventricles of mouse DMD models and human DMD (110). They further demonstrated that the overexpressed SLN is preferentially localized in the MAMs of DMD AVCMs (Table 2), which potentially increases Ca2+ concentration in the MERC area by inhibiting SERCA2a activity (i.e., inhibiting Ca2+ uptake into junctional SR), leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated cellular oxidations (74). These reports strongly support the idea that SERCA2a is indeed an important factor for determining the microdomain Ca2+ concentration within the MERC region in AVCMs (see 3.1). While the SERCA2a and its regulatory proteins are in the MERC regions, further studies are needed to determine whether these proteins can modulate the microdomain structure in AVCMs, given that interaction between SERCA2 and Mfn2 has been shown in non-CM cells (115).

5. Summary and future perspectives

In this review, we highlighted the recent reports on the structural and molecular basis of SR-Mito contact sites in AVCMs, which are functionally and morphologically distinct from ER-Mito contact sites observed in other cell types. As summarized above, most studies to date focus on Ca2+ transfer from the SR to mitochondria, while other MERC functions, such as downstream mitochondrial bioenergetics, apoptosis, ROS production, and mitophagy, are generally examined as downstream consequences of altered Ca2+ handling. Although lipid metabolism at MERCs has been well recognized in the context of cardiac pathology (20), the specific role of SR-Mito contact sites in AVCM lipid exchange remains largely unexplored. Similarly, while immune signaling is a known function of MERCs (12, 80), no studies have directly examined this in the AVCM context. Future studies will provide some clues to assess whether SR-Mito contact sites possess these roles beyond Ca2+ transport in the AVCMs.

In this review, we emphasized the roles of SR-Mito contact sites in AVCMs, a major form of MERCs in this cell type, since SR and ER are recognized as functionally distinct internal membrane compartments (78) (Fig. 1A). However, a small population of the ER-Mito contact sites should also exist in AVCMs in addition to SR-Mito contact sites. As briefly mentioned in Section 2, ER-Mito contact sites in AVCMs are likely located at the perinuclear area where perinuclear mitochondria (52) and the majority of IP3Rs (82) are located. . Such perinuclear mitochondria would be ideally positioned to engage in retrograde signaling toward the nuleus by direct and indirect routes, including via signaling crosstalk with redox-sensitive IP3 receptors (5, 11)Precise dissections of each MERC function in the different subcellular locations, such as applying live AVCM imaging to quantitatively measure MERC functions in both the dyads and perinuclear area (67) may uncover the potential roles of ER-Mito contact sites in the perinuclear mitochondria of AVCMs.

As mentioned in Section 2, MERC function from AVCMs might be slightly different across species, particularly in large animals, including humans, because of differences in the morphology of the interfibrillar mitochondria and the cytosolic Ca2+ environment (e.g., slower heartbeats), although majority of the cited research in this review is from rodent models. While sex differences in expressed genes encoding mitochondrial proteins, and the machinery for SR Ca2+ release, mtCa2+ uptake, and mitochondrial ROS have been reported (10, 16, 54), there are currently no reports specifically investigating the potential sexual dimorphism in MERC structures and functions in AVCMs. Collecting this information may be critical to develop human-specific and sex-specific computational models for mtCa2+ influx/efflux at MERCs in AVCMs, which would serve as valuable tools for precisely understanding the pathological importance of MERCs in the development of human cardiac diseases.

Lastly, atrial CMs are the second major CM type in the heart, which have distinct features of plasma membrane and SR membrane structures and Ca2+ handling mechanism (6, 9). A recent study using the sinoatrial node-specific Mfn2 KO mice showed the critical role of SR-Mito contact sites and Mfn2 in sinoatrial node automaticity (93). The decrease in the number of SR-Mito contact sites and Mfn2 protein levels was shown in right atrial appendages of patients with persistent atrial fibrillation compared with control patients (58). These reports clearly showed the importance of Ca2+ transport at SR-Mito contact sites in atrial CM function under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Future studies are needed to test whether other tethering machineries (see section 2) also exist in atrial CMs and, if so, what their relative contributions are compared to Mfn2.

Grants

This work was partly supported by NIH/NHLBI R01HL171710 (to J.O.-U. and B.S.J.), R01HL136757 (to J.O.-U.), R01HL160699 (to B.S.J.), R01HL164941 (to S.-S.S.), and R01HL122124 (to S.-S.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Al Kury LT. Calcium Homeostasis in Ventricular Myocytes of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. J Diabetes Res 2020: 1942086, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barazzuol L, Giamogante F and Cali T. Mitochondria Associated Membranes (MAMs): Architecture and physiopathological role. Cell Calcium 94: 102343, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartok A, Weaver D, Golenar T, Nichtova Z, Katona M, Bansaghi S, Alzayady KJ, Thomas VK, Ando H, Mikoshiba K, Joseph SK, Yule DI, Csordas G and Hajnoczky G. IP(3) receptor isoforms differently regulate ER-mitochondrial contacts and local calcium transfer. Nat Commun 10: 3726–3, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol 70: 23–49, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth DM, Enyedi B, Geiszt M, Varnai P and Hajnoczky G. Redox Nanodomains Are Induced by and Control Calcium Signaling at the ER-Mitochondrial Interface. Mol Cell 63: 240–248, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bootman MD, Smyrnias I, Thul R, Coombes S and Roderick HL. Atrial cardiomyocyte calcium signalling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813: 922–934, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borodiiuk NA, Semenova EN and Liampert IM. Cross reactions between polysaccharides of group A, L, and A-variant streptococci. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol (3): 22–27, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozkurt B, Ahmad T, Alexander K, Baker WL, Bo Kelly, Breathett K, Carter S, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM, Fonarow GC, Greene SJ, Heidenreich P, Ho JE, Hsich E, Ibrahim NE, Jones LM, Khan SS, Khazanie P, Koelling T, Lee CS, Morris AA, Page RL2, Pandey A, Piano MR, Sandhu AT, Stehlik J, Stevenson LW, Teerlink J, Vest AR, Yancy C, Ziaeian B and WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS. HF STATS 2024: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics An Updated 2024 Report from the Heart Failure Society of America. J Card Fail 2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandenburg S, Arakel EC, Schwappach B and Lehnart SE. The molecular and functional identities of atrial cardiomyocytes in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863: 1882–1893, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Y, Vergnes L, Wang Y, Pan C, Chella Krishnan K, Moore TM, Rosa-Garrido M, Kimball TH, Zhou Z, Charugundla S, Rau CD, Seldin MM, Wang J, Wang Y, Vondriska TM, Reue K and Lusis AJ. Sex differences in heart mitochondria regulate diastolic dysfunction. Nat Commun 13: 3850–5, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandel NS. Mitochondria as signaling organelles. BMC Biol 12: 34–34, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Yang Y, Zhou Z, Yu H, Zhang S, Huang S, Wei Z, Ren K and Jin Y. Unraveling the complex interplay between Mitochondria-Associated Membranes (MAMs) and cardiovascular Inflammation: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Int Immunopharmacol 141: 112930, 2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Csordas G, Jowdy C, Schneider TG, Csordas N, Wang W, Liu Y, Kohlhaas M, Meiser M, Bergem S, Nerbonne JM, Dorn GW 2nd and Maack C. Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk. Circ Res 111: 863–875, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Liu Y and Dorn GW 2nd. Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res 109: 1327–1331, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho KF, Branon TC, Rajeev S, Svinkina T, Udeshi ND, Thoudam T, Kwak C, Rhee H, Lee I, Carr SA and Ting AY. Split-TurboID enables contact-dependent proximity labeling in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117: 12143–12154, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clements RT, Terentyeva R, Hamilton S, Janssen PML, Roder K, Martin BY, Perger F, Schneider T, Nichtova Z, Das AS, Veress R, Lee BS, Kim D, Koren G, Stratton MS, Csordas G, Accornero F, Belevych AE, Gyorke S and Terentyev D. Sexual dimorphism in bidirectional SR-mitochondria crosstalk in ventricular cardiomyocytes. Basic Res Cardiol 118: 15–1, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Csordas G, Thomas AP and Hajnoczky G. Quasi-synaptic calcium signal transmission between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. EMBO J 18: 96–108, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Csordas G, Varnai P, Golenar T, Roy S, Purkins G, Schneider TG, Balla T and Hajnoczky G. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell 39: 121–132, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuello F, Knaust AE, Saleem U, Loos M, Raabe J, Mosqueira D, Laufer S, Schweizer M, van der Kraak P, Flenner F, Ulmer BM, Braren I, Yin X, Theofilatos K, Ruiz-Orera J, Patone G, Klampe B, Schulze T, Piasecki A, Pinto Y, Vink A, Hubner N, Harding S, Mayr M, Denning C, Eschenhagen T and Hansen A. Impairment of the ER/mitochondria compartment in human cardiomyocytes with PLN p.Arg14del mutation. EMBO Mol Med 13: e13074, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Da Dalt L, Cabodevilla AG, Goldberg IJ and Norata GD. Cardiac lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 119: 1905–1914, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Brito OM and Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 456: 605–610, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De La Fuente S, Fernandez-Sanz C, Vail C, Agra EJ, Holmstrom K, Sun J, Mishra J, Williams D, Finkel T, Murphy E, Joseph SK, Sheu SS and Csordas G. Strategic Positioning and Biased Activity of the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter in Cardiac Muscle. J Biol Chem 291: 23343–23362, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De La Fuente S, Lambert JP, Nichtova Z, Fernandez Sanz C, Elrod JW, Sheu SS and Csordas G. Spatial Separation of Mitochondrial Calcium Uptake and Extrusion for Energy-Efficient Mitochondrial Calcium Signaling in the Heart. Cell Rep 24: 3099–3107.e4, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De la Fuente S and Sheu S. SR-mitochondria communication in adult cardiomyocytes: A close relationship where the Ca(2+) has a lot to say. Arch Biochem Biophys 663: 259–268, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Stefani D, Bononi A, Romagnoli A, Messina A, De Pinto V, Pinton P and Rizzuto R. VDAC1 selectively transfers apoptotic Ca2+ signals to mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 19: 267–273, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Stefani D, Rizzuto R and Pozzan T. Enjoy the Trip: Calcium in Mitochondria Back and Forth. Annu Rev Biochem 85: 161–192, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dia M, Gomez L, Thibault H, Tessier N, Leon C, Chouabe C, Ducreux S, Gallo-Bona N, Tubbs E, Bendridi N, Chanon S, Leray A, Belmudes L, Coute Y, Kurdi M, Ovize M, Rieusset J and Paillard M. Reduced reticulum-mitochondria Ca(2+) transfer is an early and reversible trigger of mitochondrial dysfunctions in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol 115: 74–7, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding Y, Liu N, Zhang D, Guo L, Shang Q, Liu Y, Ren G and Ma X. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Front Pharmacol 15: 1398381, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dongworth RK, Mukherjee UA, Hall AR, Astin R, Ong S, Yao Z, Dyson A, Szabadkai G, Davidson SM, Yellon DM and Hausenloy DJ. DJ-1 protects against cell death following acute cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Death Dis 5: e1082, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fawcett DW and McNutt NS. The ultrastructure of the cat myocardium. I. Ventricular papillary muscle. J Cell Biol 42: 1–45, 1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fieni F, Lee SB, Jan YN and Kirichok Y. Activity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter varies greatly between tissues. Nat Commun 3: 1317, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A, Pozzan T and Pizzo P. Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 2174, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filadi R, Greotti E and Pizzo P. Highlighting the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connection: Focus on Mitofusin 2. Pharmacol Res 128: 42–51, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filadi R, Theurey P and Pizzo P. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling in health and disease: Molecules, functions and significance. Cell Calcium 62: 1–15, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foskett JK, White C, Cheung K and Mak DD. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol Rev 87: 593–658, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F and Ramesh V. Comparative ultrastructure of Ca2+ release units in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Ann N Y Acad Sci 853: 20–30, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garbincius JF, Luongo TS and Elrod JW. The debate continues - What is the role of MCU and mitochondrial calcium uptake in the heart? J Mol Cell Cardiol 143: 163–174, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giacomello M, Drago I, Bortolozzi M, Scorzeto M, Gianelle A, Pizzo P and Pozzan T. Ca2+ hot spots on the mitochondrial surface are generated by Ca2+ mobilization from stores, but not by activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Mol Cell 38: 280–290, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giacomello M and Pellegrini L. The coming of age of the mitochondria-ER contact: a matter of thickness. Cell Death Differ 23: 1417–1427, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gomez L, Thiebaut PA, Paillard M, Ducreux S, Abrial M, Crola Da Silva C, Durand A, Alam MR, Van Coppenolle F, Sheu SS and Ovize M. The SR/ER-mitochondria calcium crosstalk is regulated by GSK3beta during reperfusion injury. Cell Death Differ 23: 313–322, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall AR, Burke N, Dongworth RK, Kalkhoran SB, Dyson A, Vicencio JM, Dorn GW II, Yellon DM and Hausenloy DJ. Hearts deficient in both Mfn1 and Mfn2 are protected against acute myocardial infarction. Cell Death Dis 7: e2238, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamilton S, Terentyeva R, Perger F, Hernandez Orengo B, Martin B, Gorr MW, Belevych AE, Clements RT, Gyorke S and Terentyev D. MCU overexpression evokes disparate dose-dependent effects on mito-ROS and spontaneous Ca(2+) release in hypertrophic rat cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 321: H615–H632, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasan P, Berezhnaya E, Rodriguez-Prados M, Weaver D, Bekeova C, Cartes-Saavedra B, Birch E, Beyer AM, Santos JH, Seifert EL, Elrod JW and Hajnoczky G. MICU1 and MICU2 control mitochondrial calcium signaling in the mammalian heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121: e2402491121, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez-Alvarez MI, Sebastian D, Vives S, Ivanova S, Bartoccioni P, Kakimoto P, Plana N, Veiga SR, Hernandez V, Vasconcelos N, Peddinti G, Adrover A, Jove M, Pamplona R, Gordaliza-Alaguero I, Calvo E, Cabre N, Castro R, Kuzmanic A, Boutant M, Sala D, Hyotylainen T, Oresic M, Fort J, Errasti-Murugarren E, Rodrigues CMP, Orozco M, Joven J, Canto C, Palacin M, Fernandez-Veledo S, Vendrell J and Zorzano A. Deficient Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Phosphatidylserine Transfer Causes Liver Disease. Cell 177: 881–895.e17, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hom J and Sheu SS. Morphological dynamics of mitochondria--a special emphasis on cardiac muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 811–820, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horvath SE and Daum G. Lipids of mitochondria. Prog Lipid Res 52: 590–614, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsiao YT, Shimizu I, Wakasugi T, Yoshida Y, Ikegami R, Hayashi Y, Suda M, Katsuumi G, Nakao M, Ozawa T, Izumi D, Kashimura T, Ozaki K, Soga T and Minamino T. Cardiac mitofusin-1 is reduced in non-responding patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Rep 11: 6722–y, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu L, Ding M, Tang D, Gao E, Li C, Wang K, Qi B, Qiu J, Zhao H, Chang P, Fu F and Li Y. Targeting mitochondrial dynamics by regulating Mfn2 for therapeutic intervention in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Theranostics 9: 3687–3706, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu Q, Zhang H, Gutierrez Cortes N, Wu D, Wang P, Zhang J, Mattison JA, Smith E, Bettcher LF, Wang M, Lakatta EG, Sheu S and Wang W. Increased Drp1 Acetylation by Lipid Overload Induces Cardiomyocyte Death and Heart Dysfunction. Circ Res 126: 456–470, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G and Clapham DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427: 360–364, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohlhaas M and Maack C. Adverse bioenergetic consequences of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger-mediated Ca2+ influx in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 122: 2273–2280, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuznetsov AV, Troppmair J, Sucher R, Hermann M, Saks V and Margreiter R. Mitochondrial subpopulations and heterogeneity revealed by confocal imaging: possible physiological role? Biochim Biophys Acta 1757: 686–691, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwong JQ, Lu X, Correll RN, Schwanekamp JA, Vagnozzi RJ, Sargent MA, York AJ, Zhang J, Bers DM and Molkentin JD. The Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Selectively Matches Metabolic Output to Acute Contractile Stress in the Heart. Cell Rep 12: 15–22, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laasmaa M, Branovets J, Stolova J, Shen X, Ratsepso T, Balodis MJ, Grahv C, Hendrikson E, Louch WE, Birkedal R and Vendelin M. Cardiomyocytes from female compared to male mice have larger ryanodine receptor clusters and higher calcium spark frequency. J Physiol 601: 4033–4052, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Latchman N, Margulies K, Prosser B and Elrod J. Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)-mitochondria tethering is lost in human heart failure. Physiology 39: 1839, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leal NS, Schreiner B, Pinho CM, Filadi R, Wiehager B, Karlstrom H, Pizzo P and Ankarcrona M. Mitofusin-2 knockdown increases ER-mitochondria contact and decreases amyloid beta-peptide production. J Cell Mol Med 20: 1686–1695, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li A, Shami GJ, Griffiths L, Lal S, Irving H and Braet F. Giant mitochondria in cardiomyocytes: cellular architecture in health and disease. Basic Res Cardiol 118: 39–3, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J, Qi X, Ramos KS, Lanters E, Keijer J, de Groot N, Brundel B and Zhang D. Disruption of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Contacts Underlies Contractile Dysfunction in Experimental and Human Atrial Fibrillation: A Key Role of Mitofusin 2. J Am Heart Assoc 11: e024478, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li YE, Sowers JR, Hetz C and Ren J. Cell death regulation by MAMs: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic implications in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Dis 13: 504–2, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lipskaia L, Keuylian Z, Blirando K, Mougenot N, Jacquet A, Rouxel C, Sghairi H, Elaib Z, Blaise R, Adnot S, Hajjar RJ, Chemaly ER, Limon I and Bobe R. Expression of sarco (endo) plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) system in normal mouse cardiovascular tissues, heart failure and atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843: 2705–2718, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu JC. Is MCU dispensable for normal heart function? J Mol Cell Cardiol 143: 175–183, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu T, Yang NA Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD, Sidor A and O'Rourke B. MCU Overexpression Rescues Inotropy and Reverses Heart Failure by Reducing SR Ca(2+) Leak. Circ Res 128: 1191–1204, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y, Ma X, Fujioka H, Liu J, Chen S and Zhu X. DJ-1 regulates the integrity and function of ER-mitochondria association through interaction with IP3R3-Grp75-VDAC1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 25322–25328, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Y, Huo J, Ren K, Pan S, Liu H, Zheng Y, Chen J, Qiao Y, Yang Y and Feng Q. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM): a dark horse for diabetic cardiomyopathy treatment. Cell Death Discov 10: 148–3, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu B, Chen X, Ma Y, Gui M, Yao L, Li J, Wang M, Zhou X and Fu D. So close, yet so far away: the relationship between MAM and cardiac disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 11: 1353533, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu X, Ginsburg KS, Kettlewell S, Bossuyt J, Smith GL and Bers DM. Measuring Local Gradients of Intra-Mitochondrial [Ca] in Cardiac Myocytes During SR Ca Release. Circ Res 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu X, Thai PN, Lu S, Pu J and Bers DM. Intrafibrillar and perinuclear mitochondrial heterogeneity in adult cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 136: 72–84, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu X, Gong Y, Hu W, Mao Y, Wang T, Sun Z, Su X, Fu G, Wang Y and Lai D. Ultrastructural and proteomic profiling of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes reveal aging signatures in striated muscle. Cell Death Dis 13: 296–4, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luan Y, Guo G, Luan Y, Yang Y and Yuan R. Single-cell transcriptional profiling of hearts during cardiac hypertrophy reveals the role of MAMs in cardiomyocyte subtype switching. Sci Rep 13: 8339–2, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lukyanenko V, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Smirnov A, Wiesner TF and Gyorke S. Dynamic regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) content and release by luminal Ca(2+)-sensitive leak in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J 81: 785–798, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lukyanenko V, Ziman A, Lukyanenko A, Salnikov V and Lederer WJ. Functional groups of ryanodine receptors in rat ventricular cells. J Physiol 583: 251–269, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luongo TS, Lambert JP, Yuan A, Zhang X, Gross P, Song J, Shanmughapriya S, Gao E, Jain M, Houser SR, Koch WJ, Cheung JY, Madesh M and Elrod JW. The Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Matches Energetic Supply with Cardiac Workload during Stress and Modulates Permeability Transition. Cell Rep 12: 23–34, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma X, Li M, Liu Y, Zhang X, Yang X, Wang Y, Li Y, Wang J, Liu X, Yan Z, Yu X and Wu C. ARTC1-mediated VAPB ADP-ribosylation regulates calcium homeostasis. J Mol Cell Biol 15: mjad043. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjad043, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mareedu S, Fefelova N, Galindo CL, Prakash G, Mukai R, Sadoshima J, Xie L and Babu GJ. Improved mitochondrial function in the hearts of sarcolipin-deficient dystrophin and utrophin double-knockout mice. JCI Insight 9: e170185. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.170185, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Margulies KB, Bednarik DP and Dries DL. Genomics, transcriptional profiling, and heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 1752–1759, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McFarland TP, Milstein ML and Cala SE. Rough endoplasmic reticulum to junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum trafficking of calsequestrin in adult cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 556–564, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Michaelis R, Rooschuz B and Dopper R. Prenatal origin of congenital spastic hemiparesis. Early Hum Dev 4: 243–255, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Michalak M and Opas M. Endoplasmic and sarcoplasmic reticulum in the heart. Trends Cell Biol 19: 253–259, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Min CK, Yeom DR, Lee KE, Kwon HK, Kang M, Kim YS, Park ZY, Jeon H and Kim DH. Coupling of ryanodine receptor 2 and voltage-dependent anion channel 2 is essential for Ca2+ transfer from the sarcoplasmic reticulum to the mitochondria in the heart. Biochem J 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Missiroli S, Patergnani S, Caroccia N, Pedriali G, Perrone M, Previati M, Wieckowski MR and Giorgi C. Mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) and inflammation. Cell Death Dis 9: 329–2, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morimoto S, O-Uchi J, Kawai M, Hoshina T, Kusakari Y, Komukai K, Sasaki H, Hongo K and Kurihara S. Protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors increases Ca2+ leak in mouse heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 390: 87–92, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakayama H, Bodi I, Maillet M, DeSantiago J, Domeier TL, Mikoshiba K, Lorenz JN, Blatter LA, Bers DM and Molkentin JD. The IP3 receptor regulates cardiac hypertrophy in response to select stimuli. Circ Res 107: 659–666, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Naon D, Zaninello M, Giacomello M, Varanita T, Grespi F, Lakshminaranayan S, Serafini A, Semenzato M, Herkenne S, Hernandez-Alvarez MI, Zorzano A, De Stefani D, Dorn GW 2nd and Scorrano L. Critical reappraisal confirms that Mitofusin 2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tether. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113: 11249–11254, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nichtova Z, Fernandez-Sanz C, De La Fuente S, Yuan Y, Hurst S, Lanvermann S, Tsai H, Weaver D, Baggett A, Thompson C, Bouchet-Marquis C, Varnai P, Seifert EL, Dorn GW2, Sheu S and Csordas G. Enhanced Mitochondria-SR Tethering Triggers Adaptive Cardiac Muscle Remodeling. Circ Res 132: e171–e187, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O'Shea KM, Ananthakrishnan R, Li Q, Quadri N, Thiagarajan D, Sreejit G, Wang L, Zirpoli H, Aranda JF, Alberts AS, Schmidt AM and Ramasamy R. The Formin, DIAPH1, is a Key Modulator of Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. EBioMedicine 26: 165–174, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paillard M, Tubbs E, Thiebaut PA, Gomez L, Fauconnier J, Da Silva CC, Teixeira G, Mewton N, Belaidi E, Durand A, Abrial M, Lacampagne A, Rieusset J and Ovize M. Depressing Mitochondria-Reticulum Interactions Protects Cardiomyocytes From Lethal Hypoxia-Reoxygenation Injury. Circulation 128: 1555–1565, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Palazzuoli A and Iacoviello M. Diabetes leading to heart failure and heart failure leading to diabetes: epidemiological and clinical evidence. Heart Fail Rev 28: 585–596, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Papanicolaou KN, Khairallah RJ, Ngoh GA, Chikando A, Luptak I, O'Shea KM, Riley DD, Lugus JJ, Colucci WS, Lederer WJ, Stanley WC and Walsh K. Mitofusin-2 maintains mitochondrial structure and contributes to stress-induced permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biol 31: 1309–1328, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Perrone M, Caroccia N, Genovese I, Missiroli S, Modesti L, Pedriali G, Vezzani B, Vitto VAM, Antenori M, Lebiedzinska-Arciszewska M, Wieckowski MR, Giorgi C and Pinton P. The role of mitochondria-associated membranes in cellular homeostasis and diseases. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 350: 119–196, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pinali C and Kitmitto A. Serial block face scanning electron microscopy for the study of cardiac muscle ultrastructure at nanoscale resolutions. J Mol Cell Cardiol 76: 1–11, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Qi H, Li L and Shuai J. Optimal microdomain crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria for Ca2+ oscillations. Sci Rep 5: 7984, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Qiao X, Jia S, Ye J, Fang X, Zhang C, Cao Y, Xu C, Zhao L, Zhu Y, Wang L and Zheng M. PTPIP51 regulates mouse cardiac ischemia/reperfusion through mediating the mitochondria-SR junction. Sci Rep 7: 45379, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ren L, Gopireddy RR, Perkins G, Zhang H, Timofeyev V, Lyu Y, Diloretto DA, Trinh P, Sirish P, Overton JL, Xu W, Grainger N, Xiang YK, Dedkova EN, Zhang XD, Yamoah EN, Navedo MF, Thai PN and Chiamvimonvat N. Disruption of mitochondria-sarcoplasmic reticulum microdomain connectomics contributes to sinus node dysfunction in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119: e2206708119, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M and Pozzan T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science 262: 744–747, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rossmann MP, Dubois SM, Agarwal S and Zon LI. Mitochondrial function in development and disease. Dis Model Mech 14: 10.1242/dmm.048912. Epub 2021 Jun 11, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sassano ML, Felipe-Abrio B and Agostinis P. ER-mitochondria contact sites; a multifaceted factory for Ca(2+) signaling and lipid transport. Front Cell Dev Biol 10: 988014, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schaper J, Kostin S, Hein S, Elsasser A, Arnon E and Zimmermann R. Structural remodelling in heart failure. Exp Clin Cardiol 7: 64–68, 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schweitzer MK, Wilting F, Sedej S, Dreizehnter L, Dupper NJ, Tian Q, Moretti A, My I, Kwon O, Priori SG, Laugwitz K, Storch U, Lipp P, Breit A, Mederos Y Schnitzler M, Gudermann T and Schredelseker J. Suppression of Arrhythmia by Enhancing Mitochondrial Ca(2+) Uptake in Catecholaminergic Ventricular Tachycardia Models. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2: 737–747, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seidlmayer LK, Kuhn J, Berbner A, Arias-Loza PA, Williams T, Kaspar M, Czolbe M, Kwong JQ, Molkentin JD, Heinze KG, Dedkova EN and Ritter O. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial crosstalk influences adenosine triphosphate production via mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake through the mitochondrial ryanodine receptor in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 112: 491–501, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sharma VK, Ramesh V, Franzini-Armstrong C and Sheu SS. Transport of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria in rat ventricular myocytes. J Bioenerg Biomembr 32: 97–104, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shimizu H, Schredelseker J, Huang J, Lu K, Naghdi S, Lu F, Franklin S, Fiji HD, Wang K, Zhu H, Tian C, Lin B, Nakano H, Ehrlich A, Nakai J, Stieg AZ, Gimzewski JK, Nakano A, Goldhaber JI, Vondriska TM, Hajnoczky G, Kwon O and Chen J. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake by the voltage-dependent anion channel 2 regulates cardiac rhythmicity. Elife 4: 10.7554/eLife.04801, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shimizu Y, Lambert JP, Nicholson CK, Kim JJ, Wolfson DW, Cho HC, Husain A, Naqvi N, Chin LS, Li L and Calvert JW. DJ-1 protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating mitochondrial fission. J Mol Cell Cardiol 97: 56–66, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shimizu Y, Nicholson CK, Polavarapu R, Pantner Y, Husain A, Naqvi N, Chin L, Li L and Calvert JW. Role of DJ-1 in Modulating Glycative Stress in Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc 9: e014691, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Silbernagel N, Walecki M, Schafer MK, Kessler M, Zobeiri M, Rinne S, Kiper AK, Komadowski MA, Vowinkel KS, Wemhoner K, Fortmuller L, Schewe M, Dolga AM, Scekic-Zahirovic J, Matschke LA, Culmsee C, Baukrowitz T, Monassier L, Ullrich ND, Dupuis L, Just S, Budde T, Fabritz L and Decher N. The VAMP-associated protein VAPB is required for cardiac and neuronal pacemaker channel function. FASEB J 32: 6159–6173, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Suarez J, Cividini F, Scott BT, Lehmann K, Diaz-Juarez J, Diemer T, Dai A, Suarez JA, Jain M and Dillmann WH. Restoring mitochondrial calcium uniporter expression in diabetic mouse heart improves mitochondrial calcium handling and cardiac function. J Biol Chem 293: 8182–8195, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sun N and Finkel T. Cardiac mitochondria: a surprise about size. J Mol Cell Cardiol 82: 213–215, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, De Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, Nagy AI, Balla T and Rizzuto R. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol 175: 901–911, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Takeuchi A and Matsuoka S. Spatial and Functional Crosstalk between the Mitochondrial Na(+)-Ca(2+) Exchanger NCLX and the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca(2+) Pump SERCA in Cardiomyocytes. Int J Mol Sci 23: 7948. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147948, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson A, Kampf C, Sjostedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist P, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J and Ponten F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347: 1260419, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Voit A, Patel V, Pachon R, Shah V, Bakhutma M, Kohlbrenner E, McArdle JJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Mendell JR, Xie L, Hajjar RJ, Duan D, Fraidenraich D and Babu GJ. Reducing sarcolipin expression mitigates Duchenne muscular dystrophy and associated cardiomyopathy in mice. Nat Commun 8: 1068–7, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang P, Fernandez-Sanz C, Wang W and Sheu S. Why don't mice lacking the mitochondrial Ca(2+) uniporter experience an energy crisis? J Physiol 598: 1307–1326, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Williams GS, Boyman L, Chikando AC, Khairallah RJ and Lederer WJ. Mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 10479–10486, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu S, Lu Q, Wang Q, Ding Y, Ma Z, Mao X, Huang K, Xie Z and Zou M. Binding of FUN14 Domain Containing 1 With Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor in Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes Maintains Mitochondrial Dynamics and Function in Hearts in Vivo. Circulation 136: 2248–2266, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Xia M, Zhang Y, Jin K, Lu Z, Zeng Z and Xiong W. Communication between mitochondria and other organelles: a brand-new perspective on mitochondria in cancer. Cell Biosci 9: 27–8. eCollection 2019, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yang J, Xing X, Luo L, Zhou X, Feng J, Huang K, Liu H, Jin S, Liu Y, Zhang S, Pan Y, Yu B, Yang J, Cao Y, Cao Y, Yang CY, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Xia X, Kang T, Xu R, Lan P, Luo J, Han H, Bai F and Gao S. Mitochondria-ER contact mediated by MFN2-SERCA2 interaction supports CD8(+) T cell metabolic fitness and function in tumors. Sci Immunol 8: eabq2424, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yang S, Zhou R, Zhang C, He S and Su Z. Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Dev Biol 8: 571554, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yeo HK, Park TH, Kim HY, Jang H, Lee J, Hwang G, Ryu SE, Park SH, Song HK, Ban HS, Yoon H and Lee BI. Phospholipid transfer function of PTPIP51 at mitochondria-associated ER membranes. EMBO Rep 22: e51323, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yepuri G, Ramirez LM, Theophall GG, Reverdatto SV, Quadri N, Hasan SN, Bu L, Thiagarajan D, Wilson R, Diez RL, Gugger PF, Mangar K, Narula N, Katz SD, Zhou B, Li H, Stotland AB, Gottlieb RA, Schmidt AM, Shekhtman A and Ramasamy R. DIAPH1-MFN2 interaction regulates mitochondria-SR/ER contact and modulates ischemic/hypoxic stress. Nat Commun 14: 6900–x, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang P, Konja D, Zhang Y and Wang Y. Communications between Mitochondria and Endoplasmic Reticulum in the Regulation of Metabolic Homeostasis. Cells 10: 2195. doi: 10.3390/cells10092195, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang Y, Yao J, Zhang M, Wang Y and Shi X. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAMs): Possible therapeutic targets in heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med 10: 1083935, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zheng J, Wei C, Hase N, Shi K, Killingsworth CR, Litovsky SH, Powell PC, Kobayashi T, Ferrario CM, Rab A, Aban I, Collawn JF and Dell'Italia LJ. Chymase mediates injury and mitochondrial damage in cardiomyocytes during acute ischemia/reperfusion in the dog. PLoS One 9: e94732, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]