Abstract

Various methods are available to detect common deletions and mutations of genes related to thalassemia, including gap-polymerase chain reaction (Gap-PCR), next-generation sequencing (NGS), multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Unequal crossover during the recombination of α1 and α2 hemoglobin can be detected but hardly accurately defined by above-mentioned technologies. A couple with abnormal hematological test results arrived at our department for genetic consultation. Preliminary analysis using NGS revealed a 3.7 kb (chr16:223462–227311) heterozygote deletion in the wife and nearly six copies in the chr16:223462–227311 (GRCh37/hg19) region of the husband. Further Gap-PCR results for the wife were consistent with the NGS results. MLPA and qRT-PCR were performed to detect the potential extra copies of the α-globin gene of the husband. The analyses simultaneously showed that the copy numbers of HBA1/HBA2 genes were nearly six. A specialized primer of the α-globin gene was designed to elucidate the structure of the 4.2 or 3.7 kb repeats of the husband. Third-generation sequencing (TGS) revealed the existence of the four extra tandem duplications of 3.7 kb in DNA strand 1 (chr16:173302–177106, hg38) of the α-globin gene and the existence of a heterozygous c.301−31_301-24delinsG insertion and deletion (InDel) in DNA strand 2 in the HBA1 gene (chr16:177252–177259, hg38). These results were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Integrative Genomics Viewer analysis of the BAM files of NGS detected a low-level (reference/alternative, 0.19%) heterozygous InDel (c.301−31_301-24delinsG) in HBA1. Compared to traditional methods, TGS was better able to detect variants accurately and find rare genotypes and rearrangements of the α-globin gene cluster.

Keywords: Third-generation sequencing, Multiple copies of α-globin gene cluster, Traditional methods, Thalassemia

Introduction

Mediterranean anemia, or thalassemia, is a type of genetic hemolytic anemia caused by red blood cell disorders. It is one of the most common genetic disorders globally, especially in tropical and subtropical regions, such as Africa and Southeast Asia [1]. Over 10% of the population is a carrier of the thalassemia gene in certain southern provinces of China, such as Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, and Hainan [2].There are two types of thalassemia. α-thalassemia (OMIM #604131) is caused by abnormal genetic changes of the hemoglobin subunit alpha 1 (HBA1; OMIM *141800) and HBA2 (OMIM *141850) genes. β-thalassemia is caused by abnormal genetic changes of the hemoglobin subunit beta (HBB; OMIM *141900) gene. α-thalassemia is caused by mutations or deletions in at least one of the four α-globin genes, leading to an imbalance between α-chain and non-α-chain in hemoglobin, which in turn causes hemolytic anemia. The top three deletions responsible for α-thalassemia are Southeast Asian deletion (--SEA), right deletion (-α3.7), and left deletion (-α4.2). The non-deletion types are Hb ConstantSpring (HBA2:c.427T > C), Hb QuongSze (HBA2:c.377T > C), and Hb Westmead (HBA2:c.369 C > G) [3]. However, Triplicated α-globin genesis is generally common, while quadruplication or multicopy are quite rare (Table 1). Studies have shown that αααanti4.2 is commonly observed in Asians, with the population-based prevalence in Southern China of α-globin gene triplication 0.3%, while αααanti3.7 is more prevalent in Africans, Middle Eastern, and Mediterranean populations [4–7].

Table 1.

Genotype frequencies of αααanti3.7 in different regions

| Population | Individuals studied | Genotype frequency of αααanti3.7 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Turkish | 225 | 5 (2.2%) |

| Saudi Arabian | 104 | 4 (3.9%) |

| Omani | 634 | 3 (0.47%) |

| North Indian | 419 | 13 (3.1) |

| Indian | 1253 | 15 (1.1) |

| Dutch | 3500 | 42(1.2%) |

| Mexican | 109 | 11 (10%) |

| lranian | 4010 | 69(1.7%) |

| lranian | 1700 | 20(1.2%) |

| lranian | 6404 | 84(1.31%) |

| Netherlands | 3500 | 42(1.2%) |

| Southern China | 1167 | 11(0.9%) |

| Guangxi, China | 23,900 | 0.39% |

Carriers of α-globin gene duplications alone generally show no clinical abnormalities, but when combined with β-thalassemia, they can present with β-thalassemia intermedia or exacerbate anemia [8, 9]. Patients with β-thalassemia intermedia typically experience moderate to severe anemia, often accompanied by splenomegaly and mild jaundice. Regular blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy are essential for patients with severe β-thalassemia, which impose significant economic and psychological burdens on their families and society [10]. In individuals with heterozygous β-thalassemia (β-thalassemia trait), the presence of triplicate, quadruplicate, or multiple copies of the α-globin gene can exacerbate the imbalance of the α/β-globin chain ratio, which may lead to a more severe clinical phenotype, transforming an otherwise asymptomatic β-thalassemia carrier into an intermediate thalassemia phenotype or worsening the clinical presentation of individuals with intermediate or severe β-thalassemia [8, 9]. Therefore, if one person carries a co-inherited α-globin gene duplication, and his or her spouse carries one β-thalassemia mutation, their offspring has a 25% chance of developing the β-thalassemia intermedia (TI) phenotype.

Traditional genetic diagnostic techniques are unable to identify the duplications of the α-globin gene. Techniques such as Sanger sequencing and single-tube multiplex gap-PCR (Gap-PCR) have been employed to detect common variants that include single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions and deletions (InDels), single nucleotide variants (SNVs), and copy number variations (CNVs) in HBA1/HBA2. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), and next-generation sequencing (NGS) can identify HBA gene duplications, which have shown advantages for screening thalassemia genes. However, NGS is limited in that it cannot accurately distinguish the distribution across chromosomes or detect rare variants located in regular sequences, which may potentially lead to missed or incorrect diagnoses [11]. Third-generation sequencing (TGS) based on the single-molecule real-time (SMRT) technology provides a more precise analysis method for duplication distribution on both chromosomes and can identify novel genotypes and rearrangements of the α-globin gene cluster [12]. Here, we identified the specific location of α-globin gene duplication in the genome by TGS and identified missed InDel by NGS.

Materials and methods

Subjects and hematologic analysis

A 27-year-old male had an abnormal level of mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) of 26.4 pg and normal α2 hemoglobin (HbA2) and fetal hemoglobin (HbF) as determined by automatic high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). His 25-year-old wife had a low hemoglobin level of 105 g/L and an HbA2 level of 2.3% on HPLC. The hematological data of the patients are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hematological data of the couple

| Female | Male | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 25 | 27 | / |

| Hb (g/l) | 105 | 162 |

Adult female:115–150 Adult male:130–175 |

| MCV (fl.) | 98.4 | 90.6 | 82.0-100.0 |

| MCH (pg) | 27.3 | 26.4 | 27.0–34.0 |

| HbA2 (%) | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.5–3.5 |

| HbF (%) | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0–2.0 |

Both patients came to the Department of Medical Genetics, West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University, for further genetic investigation. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Both patients received comprehensive genetic counseling and provided informed consent.

NGS

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood samples using a nucleic acid extraction kit based on the magnetic bead method (MyGenostics, Chongqing, China). The extracted DNA had a minimum concentration of ≥ 25 ng/µL and a 260 nm/280 nm ratio ranging from 1.7 to 2.0. Library preparation was performed using an enzyme digestion method with a V5.0 library preparation kit (MyGenostics). Library products were required to have a fragment length distribution between 200 and 500 bp. Subsequently, the samples were combined into a single hybridization unit, with each sample containing 600 ng. Probes and buffer (GenCap® Universal Nucleic Acid Fragment Enrichment Purification Kit V2.3, MyGenostics) were added to each hybridization unit, which was then hybridized for 12–24 h to achieve enrichment. The double-stranded DNA probes covered the entire length of HBA1, HBA2, and HBB. The concentration of each hybridization unit was quantified using absolute quantitative qPCR, and pooling was performed based on the qPCR results. Sequencing was conducted on the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using a NextSeq CN500 Mid Output Kit (Illumina). After sequencing, data were aligned against preprocessed data and the human reference genome GRCh37/hg19 using BWA (Version 0.7.10; https://www.plob.org/tag/bwa). Base recalibration was conducted using GATK (Version 4.0.8.1; https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). SNPs, insertions, and InDels were annotated using ANNOVAR software (Version 1; http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/) [13]. The BAM files produced by NGS were viewed using Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV) software (Version 2.17.3). Pathogenicity analysis was performed in accordance with the sequence variation interpretation standards and guidelines recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) [14].

Gap-PCR

Gap-PCR was used to identify three common α-thalassemia deletion mutations (-α3.7, -α4.2, and–SEA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Yaneng Bioscience, Shenzhen, China).

qRT-PCR

NGS analysis revealed increased copy numbers of the HBA1/HBA2 genes in the male sample. To confirm this finding, 2−ΔΔCt qRT-PCR was performed [15]. HBA1 and HBA2 contain three highly homologous nucleotide fragments, designated the X, Y, and Z segments [16]. The copy numbers of these genes were evaluated by measuring the Z segments, based on the molecular structures of αααanti3.7 and αααanti4.2 [4]. Primers targeting exon 3 of HBA2 in the Z segments were designed, with the β-actin gene serving as an internal control. Each primer pair yielded a unique sequence. A sample with two copies of HBA1/HBA2 was used as the calibrator. The threshold cycle (Ct) was measured on a 7500 FAST Dx Real-Time PCR platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and was run in triplicate. ΔCt values were calculated as Ct HBA2 - Ct β−actin. ΔΔCt was calculated as ΔCt the male sample - ΔCt calibrator sample. The relative quantification was computed using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with 2−ΔΔCt representing the relative ratio of the male sample to the calibrator sample.

MLPA

The MLPA technique utilized the SALSA MLPA Probemix P140-C1 HBA (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands), which consisted of 45 MLPA probes (34 probes for the α-globin gene cluster and its flanking regions and 11 reference probes). The analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions [17]. Deletion and duplication thresholds were set at < 0.8 and > 1.2, respectively.

TGS

TGS was used to analyze the structure of the 3.7 kb or 4.2 kb repeats. Customized primers for amplification of HBA were used (F: AAATAGGCTGTCCCCAATGCAAGTGAAG, R: CTGAAGCAGCAGGARTGGAGAAGGAAAT). The amplification process was: 98℃ for 2 min; 26 cycles of 98℃ for 10 s, 60℃ for 15 s, and 68℃ for 30 min; and 68℃ for 5 min. After purification, end repair, and ligation with double-barcode adapters to both ends, the SMRT bell libraries were constructed using the Sequel Binding and Internal Ctrl Kit 3.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Subsequently, we sequenced the samples using the PacBio Sequel II platform and processed the raw data using circular consensus sequencing (CCS) software to generate CCS reads. We aligned the CCS reads to primer pair sequences using BLASTn and retained the CCS reads with both primers, which were then aligned to the genome build hg38 using pbmm2 (Pacific Biosciences). Next, we analyzed SNVs, small insertions, and InDels using FreeBayes software (Biomatters, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Multiple HBA genes were identified and visualized using IGV software.

Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing was used to verify the variants of HBA1 and HBA2. The primers were designed using NCBI primer blast software. After purifying the PCR product, sequencing was performed, and the results were visualized using Chromas software version 2.4.1 (Technelysium Pty Ltd., South Brisbane, Australia).

Results

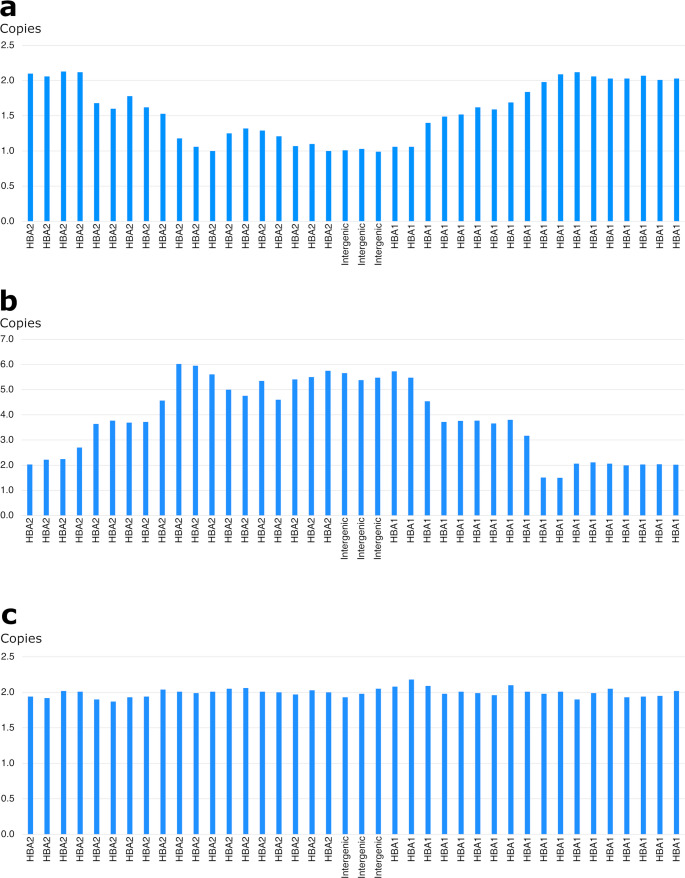

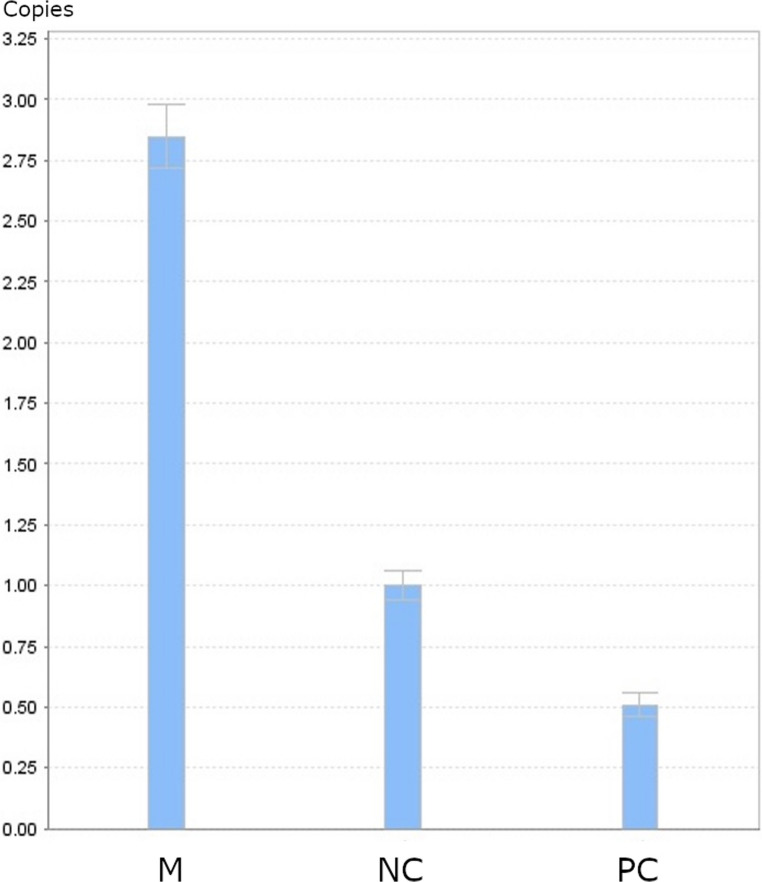

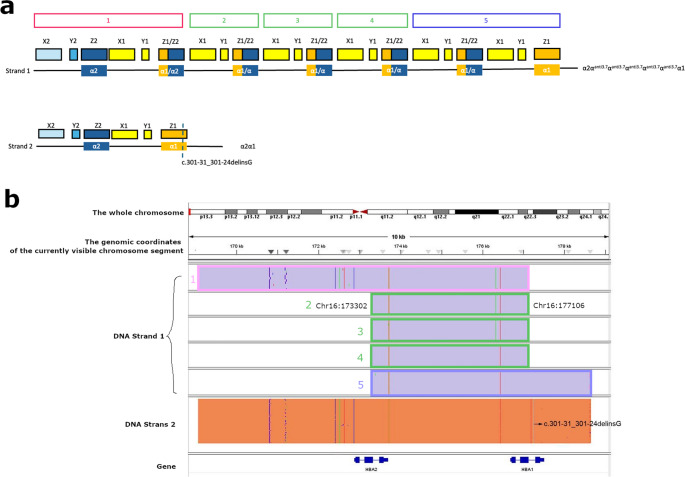

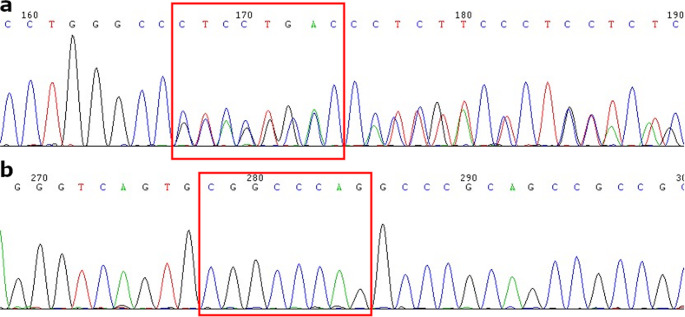

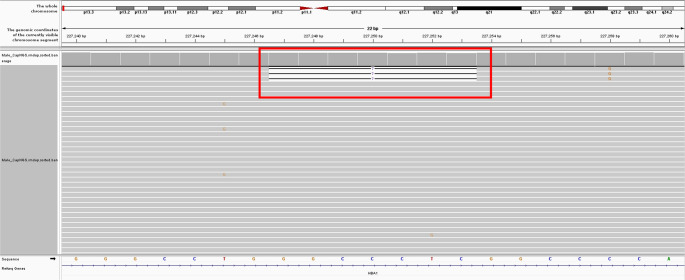

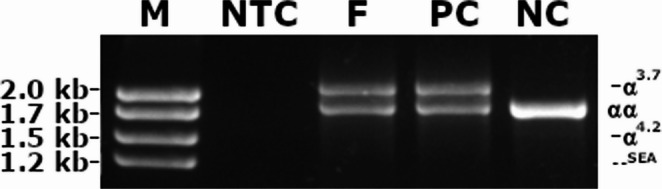

NGS revealed that the female carried a 3.7 kb heterozygote deletion (chr16:223462–227311, average copy 0.61; the threshold was set at 1), with no detectable point mutations in either α- or β-globin genes. To confirm these findings, additional validation Gap-PCR of the female sample was performed. A 3.7 kb heterozygote deletion was found (Fig. 1). Preliminary NGS results of the male sample revealed the presence of nearly six copies α-globin genes in the αααanti3.7 region (chr16:223462–227311, average copy number 2.26). The copy numbers of HBA1/HBA2 in the couple as determined by NGS are shown in Fig. 2. The qRT-PCR result for the male sample is shown in Fig. 3. This result confirmed that the copy numbers of HBA1/HBA2 genes in the male sample were nearly 6 (RQ (2−ΔΔCt) = 2.85), compared with the negative control. MLPA detected enhanced signal intensity in the HBA1 and HBA2 regions of males, and based on the final ratio calculation, it is speculated that the copy numbers of the regions were nearly 6 (Fig. 4). TGS revealed that the allelic configuration of the male was composed of the 4 extra tandem duplications of the 3.7 kb in DNA strand 1 (chr16:173302–177106, hg38) and the normal α-globin in DNA strand 2. Additionally, a heterozygous c.301−31_301-24delinsG InDel was identified in HBA1 cells (Fig. 5). Sanger sequencing revealed a heterozygous c.301−31_301-24delinsG InDel in the HBA1 gene (chr16:177252–177259, hg38), while no such InDel was found in the HBA2 gene. Figure 6 shows the Sanger sequencing results of the HBA1 and HBA2 gene InDels. The primers for Sanger sequencing and qRT-PCR information are provided in Table 3. IGV examination of the BAM files produced by NGS detected a low-level (reference/alternative, 0.19%) heterozygous InDel (c.301−31_301-24delinsG) in HBA1, but not in HBA2 of the male sample (Fig. 7). This is the first report of a patient with 6 copies of the α-globin gene with a heterozygous c.301−31_301-24delinsG InDel in HBA1 gene.

Fig. 1.

The result of Gap-PCR. M: marker; NTC: no template control; F: female sample; PC: positive control(-α3.7/αα); NC: negative control

Fig. 2.

A Copy numbers of HBA1/HBA2 of the female sample by NGS. B Copy numbers of HBA1/HBA2 of the male sample by NGS. C Copy numbers of HBA1/HBA2 of the negative control by NGS

Fig. 3.

The result of qRT-PCR. M: male sample; NC: negative control; PC: positive control, --SEA/αα

Fig. 4.

The result of MLPA. Analysis of the multiple copies of α- globin cluster of the male. The y-axis represents the ratio signal as compared to the negative control (ratio 0.8–1.2); on the x-axis, the MLPA-probe numbers are ordered chronologically in the 5’ to 3’ direction along the region

Fig. 5.

TGS results of the male sample. A After analysis using TGS, the gene structures of two DNA strands were detected, where chain 1 had a complex structure and chain 2 has a heterozygous c.301−31_301-24delinsG InDel. According to the homology of the α-globin gene cluster, we divided it into X, Y, and Z segments[16]. According to the sequencing results, the structure of chain 1 is seen as α2-αanti3.7-αanti3.7-αanti3.7-αanti3.7-αanti3.7-α1. B TGS double-stranded DNA results, corresponding to the structure in A

Fig. 6.

Sanger sequencing verification results of mutation. A DNA sequencing results of HBA1 (chr16:227251–227258) c.301−31_301−24. B DNA sequencing results of HBA2 (chr16:223440–223447) c.301−31_301−24

Table 3.

Primers for Sanger sequencing and qRT-PCRa

| Method | Gene | Mutation | 5’→3’ sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger sequencing | HBA1 | c.301−31_301-24delinsG |

F: GTGGACGACATGCCCAAC R: AGCAAATGCATCCTCAAAGC |

| HBA2 |

F: CTCTTCTGGTCCCCACAGAC R: ACCTCCATTGTTGGCACATT |

||

| qRT-PCRa | HBA2 | / |

F: CCGTGCTGACCTCCAAATACC R: CCTCCATTGTTGGCACATTCC |

| β-actin | / |

F: TGCTGTCTCCATGTTTGATGTATCT R: TCTCTGCTCCCCACCTCTAAGT |

aqRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Fig. 7.

The NGS results of the male sample. A low-level (reference/alternative, 0.19%) heterozygous InDel (c.301−31_301-24delinsG) in the HBA1

Discussion

In this study, two different strategies were employed to validate the NGS and Gap-PCR approaches. Their use on the female patient in this study both indicated a 3.7 kb heterozygous deletion consistent with silent type without hematological alteration or mild anemia (low hemoglobin level).

According to the guidelines of the British Committee for Standards in Hematology, α-thalassemia should be considered if the MCH is < 27 pg in the absence of a hemoglobin variant, β- or δβ-thalassemia heterozygosity [18]. Initially, we assumed that the male patient might be a traditional thalassemia carrier because of the low MCH in the hematological phenotype. Nevertheless, these results are intriguing. The male was found to have nearly 6-copy heterozygote in the αααanti3.7 region (chr16:223462–227311), while a decreased level of MCH was detected. Previous studies have shown that individuals with extra copies of the α-globin gene do not exhibit significant differences in hematological phenotypes compared to normal individuals [19, 20]. Duplication of α-globin genes has resulted from unequal crossover between misaligned homologous segments in the α-globin gene cluster during meiosis. This anomaly is barely detectable in clinical practice when present in isolation, as it is always benign and exerts no obvious influence on hematological parameters [21]. Therefore, in order to determine the relationship between HBA1 c.301−31_301-24delinsG variant and the decreased MCH in this male individual, the ACMG guidelines for classification were introduced. However, this variant was classified as “uncertain”, as it was observed in only one individual (HGB: 103 g/L, MCV: 67 fL, MCH: 19.4 pg, Hb A2: 2.1), but gender and the presence of other variants were not specified [22]. Moreover, the abnormal hemoglobin and white blood cell counts in this patient were inconsistent with our case. We did not identify any other potential cause for the isolated low levels of MCH. So large number of samples are needed to validate the above results.

Tandem duplications of α-globin genes often produce tandem arrays of genes that are usually nonfunctional, similar to pseudogenes [23]. However, co-inheritance of α-globin gene duplication and one β-thalassemia mutation can exacerbate the imbalance in α- and β-globin chains, leading to variable clinical phenotypes, including asymptomatic presentation, significant anemia, ineffectual erythropoiesis, and mild, moderate, or severe clinical features [24]. This information is important for pre-pregnancy genetic counseling. If we had only used traditional 3-level hematologic and genetic screening for thalassemia, the male’s extra copies of the α-globin gene and InDel would not have been detected. If the partner carried β-thalassemia, their offspring would have a 25% chance of developing the TI phenotype. Thalassemia intermedia and major are especially burdensome to the patient himself/herself, the family, and society because of the current lack of effective treatment. Fortunately, this couple was ultimately not considered to be at high risk for thalassemia; therefore, it is not necessary to offer a prenatal diagnosis when the female is pregnant.

As shown in Table 1, the frequencies of αααanti3.7 vary across in different regions. Triplicated α-globin genesis, especially αααanti3.7, is generally common, while quadruplication or multicopy are quite rare. In this study, the results of the male were derived from the complementary validation of multiple techniques. NGS is increasingly employed to amplify all exons and introns of the HBA1, HBA2, and HBB genes. Therefore, most thalassemia-associated mutations in the human HbVar database and thalassemia mutations can be identified in clinical practice [25, 26]. NGS has the advantages of high throughput and relatively low cost; however, it is limited to the identification of rare SNVs in thalassemia genes. The qRT-PCR and MLPA assays were also used to identify unknown CNVs that were missed by traditional assays, and they were also used to estimate the size of arrangement in the HBA region roughly; the procedure was complex and prone to false negatives. Sanger sequencing was used to verify variants in the HBA1 and HBA2 genes, focusing only on known SNPs and InDels; however, this method cannot detect large segment deletions or CNVs. Although conventional methods were used in a stepwise approach to validate the novel α-globin gene multicopy variants identified by NGS, they are unable to address complex issues such as unequal crossover during recombination of the α1 and α2 hemoglobin genes. Additionally, a low percentage of heterozygous may be ignored by NGS, as observed in our initial results. TGS technology, also known as long-molecule sequencing, has recently emerged as a useful method for genetic diagnosis owing to its advantages of long reads, high accuracy, single-molecule resolution, and lack of GC preference [27]. TGS could detect the variants more accurately compared with conventional methods [28] and define novel genotypes and rearrangements of the α-globin gene cluster [29, 30]. TGS applications and usefulness in different omic fields. For genomics, it can detect large structural variants, allow de novo assembly of repeated regions and identify tandem repeats number; for transcriptomics, it highlight differential gene expression, classify unannotated splice isoforms and characterize RNA isoforms at single-molecule level; for epigenomics, it improve methylation status, pinpoint different nucleotides modifications, overcome bisulfite treatment; for metagenomics, it establish specific microbiome profiles, recognize mixed microbial communities and perform targeted gene analysis [31]. It is reported that TGS detected an additional 7.9% of clinically significant variants as compared with PCR-based methods, altering the predicted phenotype for 2.88% of fetuses. Besides, PCR based methods resulted in four testing errors, one of which could have led to the wrongful termination of a pregnancy. This study concluded that compared to PCR based methods, TGS offers a more comprehensive and precise approach, facilitating better-informed genetic counseling and enhanced clinical outcomes than PCR-based methods [28].

We used TGS based on SMRT to reveal the duplications of the 3.7 kb and a heterozygous InDel in the HBA1 gene. The results revealed that TGS technology had significant advantages in thalassemia carrier screening for allele mutations of the globin gene in cis or trans, which could effectively conduct single nucleotide polymorphism linkage analysis in long read-based phasing. To the best of our knowledge, the genotypes identified in this study have not been previously reported. Based on the TGS results, Sanger sequencing was performed for verification, which revealed a heterozygous c.301−31_301-24delinsG InDel in the HBA1 gene, while no such InDel was detected in the HBA2 gene. Subsequently, we re-evaluated the BAM files generated by NGS using IGV software. Upon careful examination, we identified low-level heterozygous (reference/alternative, 0.19%) for the c.301−31_301-24delinsG InDel in the HBA1 gene, but not in the HBA2 gene, in the male sample, which is consistent with the TGS results. The omission by NGS may be due to the presence of the InDel (chr16:227251–227258) within a 6-copy region of the α-globin gene in the αααanti3.7 region (chr16:223462–227311). The abundance of repeated sequences in this region likely diluted the InDel signal, leading to its classification as a low percentage heterozygous and its subsequent omission from the NGS report.

Conclusions

This study identified multiple rare copies of α-globin using various methods. The results further validated the use of the TGS method, which could better cover the entire sequences of HBA1 and HBA2, thus allowing for thorough identification of the rarest deletions or duplications in these two genes. Accurate genetic test results can reasonably explain the clinical phenotype of patients and accurately guide fertility decisions.

Author contributions

H. L: Methodology, writing original draft, validation.

C. Z: Data curation, methodology, supervision, writing review and editing.

J. W: Data curation, methodology, supervision, writing review and editing.

Y.P. D: validation, writing original draft.

Y.T. Y: Data curation, writing original draft.

D. C: Methodology, data curation.

L.B. C: Methodology, data curation.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Informed consent

The patient and her family signed informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cong Zhou, Email: zhoucongnoi@163.com.

Jing Wang, Email: hhwj_123@163.com.

References

- 1.Kattamis A, Kwiatkowski JL, Aydinok Y (2022) Thalassaemia. Lancet 399:2310–2324. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00536-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shang X, Peng Z, Ye Y et al (2017) Rapid targeted Next-Generation sequencing platform for molecular screening and clinical genotyping in subjects with hemoglobinopathies. EBioMedicine 23:150–159. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harteveld CL, Higgs DR (2010) Alpha-thalassaemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 5:13. 10.1186/1750-1172-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long J, Liu E (2021) The carriage rates of αααanti3.7, αααanti4.2, and HKαα in the population of guangxi, China measured using a rapid detection qPCR system to determine CNV in the α-globin gene cluster. Gene 768:145296. 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamid M, Keikhaei B, Galehdari H et al (2021) Alpha-globin gene triplication and its effect in beta-thalassemia carrier, sickle cell trait, and healthy individual. EJHaem 2:366–374. 10.1002/jha2.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piero G, Margaretha B, Harteveld CL (2009) Frequency of alpha-globin gene triplications and their interaction with beta thalassemia mutations. Hemoglobin 33:124–131. 10.1080/03630260902827684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu MY, Zhou JY, Li J et al (2016) The frequency of alpha-Globin gene triplication in a Southern Chinese population. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 32:320–322. 10.1007/s12288-015-0588-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark B, Shooter C, Smith F et al (2018) Beta thalassaemia intermedia due to co-inheritance of three unique alpha globin cluster duplications characterised by next generation sequencing analysis. Br J Haematol 180:160–164. 10.1111/bjh.14294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pang D, Shang X, Cai D et al (2019) Thalassaemia intermedia caused by coinheritance of a β-thalassaemia mutation and a de Novo duplication of α-globin genes in the paternal allele. Br J Haematol 186:620–624. 10.1111/bjh.15958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galanello R, Origa R (2010) Beta-thalassemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 5:11. 10.1186/1750-1172-5-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng C, Zhang H, Ren J et al (2022) Analysis of rare thalassemia genetic variants based on third-generation sequencing. Sci Rep 12:9907. 10.1038/s41598-022-14038-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Xie T, Ma M et al (2023) Case report: identification of a novel triplication of alpha-globin gene by the third-generation sequencing: pedigree analysis and genetic diagnosis. Hematology 28:2277571. 10.1080/16078454.2023.2277571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mccombie WR, Mcpherson JD, Mardis ER (2019) Next-Generation sequencing technologies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 9:a036798. 10.1101/cshperspect.a036798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S et al (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med 17:405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farashi S, Harteveld CL (2018) Molecular basis of α-thalassemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis 70:43–53. 10.1016/j.bcmd.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Instructions for Use SALSA® MLPA® Probemix P140 HBA. Document version C1-08 Issued on 12 March 2025. https://www.mrcholland.com/products/37492/Product%20Description%20P140-C1%20HBA-v08.pdf

- 18.Ryan K, Bain BJ, Worthington D et al (2010) Significant haemoglobinopathies: guidelines for screening and diagnosis. Br J Haematol 149:35–49. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Jiang H, Wu MY et al (2015) Thalassemia intermedia caused by 16p13.3 sectional duplication in a β-Thalassemia heterozygous child. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 32:349–353. 10.3109/08880018.2015.1040932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu L, Shang X, Yi S et al (2016) Two novel copy number variations involving the α-globin gene cluster on chromosome 16 cause thalassemia in two Chinese families. Mol Genet Genomics 291:1443–1450. 10.1007/s00438-016-1193-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shang X, Xu X (2017) Update in the genetics of thalassemia: what clinicians need to know. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 39:3–15. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xian J, Wang Y, He J et al (2022) Molecular epidemiology and hematologic characterization of thalassemia in Guangdong province, Southern China. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 28:10760296221119807. 10.1177/10760296221119807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner A (1998) The fate of duplicated genes: loss or new function? BioEssays 20:785–788. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199810)20:10%3C;785::AID-BIES2%3E;3.0.CO;2-M [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Farashi S, Bayat N, Faramarzi GN et al (2015) Interaction of an α-Globin gene triplication with β-Globin gene mutations in Iranian patients with β-Thalassemia intermedia. Hemoglobin 39:201–206. 10.3109/03630269.2015.1027914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J, Li J, Lai Q et al (2020) Combined use of gap-PCR and next-generation sequencing improves thalassaemia carrier screening among premarital adults in China. J Clin Pathol 73:488–492. 10.1136/jclinpath-2019-206339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Li C, Li J et al (2019) Next-generation sequencing improves molecular epidemiological characterization of thalassemia in Chenzhou region, P.R. China. J Clin Lab Anal 33:e22845. 10.1002/jcla.22845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenger AM, Peluso P, Rowell WJ et al (2019) Accurate circular consensus long-read sequencing improves variant detection and assembly of a human genome. Nat Biotechnol 37:1155–1162. 10.1038/s41587-019-0217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang Q, He J, Li Q et al (2023) Evaluating the clinical utility of a Long-Read Sequencing-Based approach in prenatal diagnosis of thalassemia. Clin Chem 69:239–250. 10.1093/clinchem/hvac200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long J, Sun L, Gong F et al (2022) Third-generation sequencing: A novel tool detects complex variants in the α-thalassemia gene. Gene 822:146332. 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ning S, Luo Y, Liang Y et al (2022) A novel rearrangement of the α-globin gene cluster containing both the -α3.7 and ααααanti4.2 crossover junctions in a Chinese family. Clin Chim Acta 535:7–12. 10.1016/j.cca.2022.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scarano C, Veneruso I, De Simone RR et al (2024) The Third-Generation sequencing challenge: novel insights for the omic sciences. Biomolecules 14:568. 10.3390/biom14050568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.