Abstract

Across three nationally representative surveys (N = 9.2 million), U.S. adults reported increasingly poor mental health between 1993 and 2020. In the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, poor mental health days rose from 3 to 4 days per month, and from 3.55 to 6.02 days per month among young adults ages 18–25. Twice as many young adults spent half or more of their days in poor mental health in 2018–20 compared to 1993–99. Nearly all of the increase occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. In the National Health Interview Survey, 30% more young adults and prime-age adults (ages 26–49) reported moderate to high mental distress in 2017–18 compared to 1997–99. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, more than twice as many young adults, and 50% more prime-age and older (50 +) adults, fit criteria for moderate to severe depression in 2017–20 compared to 2006–07. The pronounced increase in mood disorder symptoms identified among adolescents has now moved up the age scale to younger adults.

Keywords: Psychiatric epidemiology, Depression, Stress, Mental distress

The negative impact of poor mental health can be seen in many societal domains, including medical comorbidities, mortality rates, and economic impact. Mental disorders and their symptoms are often comorbid with a variety of medical conditions [21]; for example, depressive symptoms and heart disease are highly comorbid [26]. In addition, the presence of any mental disorder was strongly related to longevity in a 17-year study, with the age of death 8.2 years younger for those with a mental disorder compared to those without [10]. Causes of death in this study were almost all medical, highlighting that poor mental health contributes to poor physical health.

In addition to the medical cost, morbidity, and life lost due to mental illness, the economic costs of poor mental health are extremely high. For example, studies have shown that poor mental health results in decreased work productivity [5]. While the direct costs of mental disorders (including treatment and hospitalization) are quite high, it is the indirect costs – income lost due to disability, decreased productivity, and mortality – that are the most staggering. In 2010, when mental illness and substance use concerns contributed 10.4% of the global burden of disease, direct and indirect costs of mental disorder were estimated to be between $2.5 and $8 trillion worldwide [32].

Given these burdens, it seems especially important to determine if rates of mental illness have increased over time. Several studies have documented increases in mood disorder indicators such as depression and suicidal ideation among U.S. adolescents since 2010 [22], [36], [40]. However, mood disorder trends among adults have received less attention [35]. It is thus unclear whether the documented increase in mood disorder indicators among American adolescents extends to adults.

In addition, it is unknown whether trends in adults’ mood disorder indicators are due to age, time period, or birth cohort, three different processes that can cause change over time [6], [29], [38]. First, change can be due to age or development; for example, the incidence of mood disorders generally lessens with age, with likelihood of onset increasing at puberty and peaking in the mid-20 s [1]. With the overall U.S. population aging, trends in mood disorders could be at least partially due to age differences, or could be confounded by them. Second, change can be due to time period, or a cultural change that affects people of all ages. Perhaps more (or fewer) Americans of all ages are experiencing poor mental health.

Third, changes in mental health could be due to cohort (also known as generation), a cultural change that affects people differently depending on their year of birth. Perhaps more young Americans in recent cohorts are experiencing mood disorders even if previous (older) cohorts are not. Such a finding would suggest a cohort or generational effect, with cultural changes having a larger effect on younger age groups than older age groups. To this end, we occasionally employ the common names for American generations [34], including Silents (born 1925–1945), Boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1979), Millennials (1980–1994), and Generation Z (1995–2012).

In this paper, we seek to explore trends in mood disorder indicators, including days of poor mental health, mental distress, and depressive symptoms, between the 1990 s and the 2020 s in three nationally representative CDC-administered datasets of U.S. adults (N = 9.2 million) using screening measures. We take a two-pronged approach to examining these trends. First, we document trends in mental health indicators among all adults and within age groups. Second, we perform age-period-cohort (APC) analysis, a relatively new statistical technique that employs hierarchical linear modeling to separate the effects of age, time period, and cohort/generation [38], [39].

1. Study 1

Study 1 draws on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) administered by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Since 1993, the survey has asked U.S. adults how many days in the last 30 days they have suffered from poor mental health, including stress, depression, or emotional issues. Responses to this question have been used to gauge general mental health across numerous studies (e.g., [9], [13], [23]).

1.1. Methods

1.1.1. Participants

U.S. adult participants ages 18 and over (n = 8817,570) took part in the nationally representative BRFSS via telephone between 1993 and 2020. The design is cross-sectional, with different participants assessed each year. Response rates were 50% in most years. Data are publicly available and de-identified. The analysis of de-identified, publicly available data does not constitute human subjects research as defined in 45 CFR 46.102.

1.1.2. Measures

Participants were asked “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” Responses could range between 0 and 30. We also considered the percentage of respondents who experienced poor mental health on more than half of days (15 or more days out of 30; [2]).

1.1.3. Data analysis

As recommended by the survey administrators, sample weights were applied to account for non-response and make the data nationally representative. Participants were grouped by age into the three groups (18–25, 26–49, and 50 +) employed in the National Study of Drug Use and Health and used in previous research on mental health trends [35]. We will refer to these three groups as young adults (18−25), prime-age adults (26−49), and older adults (50 +). Differences across time periods were compared using t-tests, d (difference in terms of standard deviations), and, for the percent suffering from poor mental health on more than half of days, relative risk.

To separate the effects of age, period, and cohort, we performed APC analyses, a technique based on hierarchical linear modeling. Following the recommendations of Yang and Land [39], we conducted a hierarchical APC with cross-classified random effects (HAPC-CCREM). We specified both cohort and period as random effects, leaving age – with linear, quadratic, and cubic terms – as a fixed effect. The model has three variance components: One for variability in intercepts due to cohorts (τu0), one for variability in intercepts due to period (τv0), and a residual term containing unmodeled variance within cohorts and periods. Variance in the intercepts across time periods and cohorts indicates period and cohort differences, respectively. Effectively, this allows us to estimate the mean for each year and cohort, with year and cohort independent of each other and of age. All APC analyses were conducted using the lme4 package [3] in R [25].

1.1.4. Results

American adults reported increasingly more days of poor mental health between 1993 and 2020 (see Table 1). Days of poor mental health increased from a mean of three days a month in 1993–99 to four days a month in 2018–20. Nearly all of the increase occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S. in 2020 (see Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Poor mental health days, by age group and time period.

| 1993–99 | 2000–09 | 2010–14 | 2015–17 | 2018–20 | 1990 s v. 2018–20 | 2010–14 v. 2018–20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days per month | |||||||

| 18–25 | 3.55 (6.92) 95953 | 4.08 (7.52) 185437 |

4.20 (7.66) 129211 |

4.79 (8.14) 89097 |

6.01 (8.90) 87725 |

0.32* | 0.22* |

| 26–49 | 3.22 (7.15) 439767 |

3.61 (7.60) 1168755 |

3.99 (8.11) 683769 |

4.07 (8.17) 375473 |

4.59 (8.50) 356361 |

0.18* | 0.07* |

| 50 + | 2.34 (6.74) 338335 |

2.86 (7.30) 1625649 |

3.33 (7.83) 1520455 |

3.28 (7.81) 890639 |

3.34 (7.83) 789855 |

0.14* | 0.00 |

| All | 2.95 (6.99) 877937 |

3.38 (7.49) 3003920 |

3.73 (7.93) 2346563 |

3.81 (8.02) 1355209 |

4.20 (8.30) 1233941 |

0.17* | 0.06* |

| % more than half of days | |||||||

| 18–25 | 8.78% 95953 |

10.59% 185437 |

11.20% 129211 |

13.32% 89097 |

17.58% 87725 |

2.00 (1.95, 2.05) | 1.57 (1.54, 1.60) |

| 26–49 | 8.17% 439767 |

10.08% 1168755 |

11.67% 683769 |

11.83% 375473 |

13.58% 356361 |

1.66 (1.64, 1.68) | 1.16 (1.15, 1.18) |

| 50 + | 6.95% 338335 |

8.50% 1625649 |

10.13% 1520455 |

9.96% 890639 |

10.20% 789855 |

1.47 (1.45, 1.49) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) |

| All | 8.09% 877937 |

9.52% 3003920 |

10.92% 2346563 |

11.19% 1355209 |

12.55% 1233941 |

1.55 (1.54, 1.57) | 1.15 (1.14, 1.16) |

NOTES: 1. For days per month, numbers are mean, (SD), n and effect sizes are d (difference in standard deviations). * = t-test yields p < .05. 2. For percentage with more than half of days, numbers are percent, n and effect sizes are relative risk and 95% confidence interval. RR’s with confidence interval not including 1 are in bold.

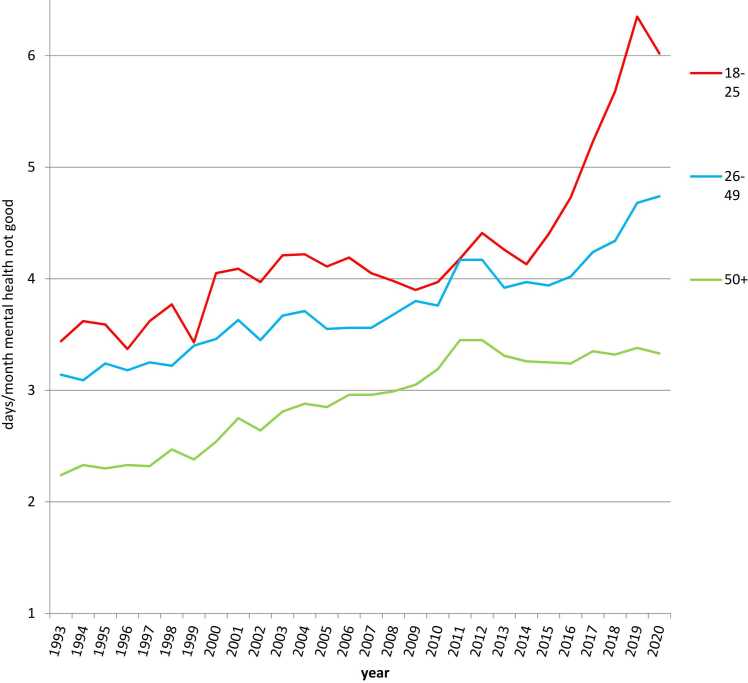

Fig. 1.

Days of poor mental health among U.S. adults, by age group and year, 1993–2020.

The increase in mental distress was most pronounced among young adults ages 18–25, with the number of poor mental health days increasing 69%, from 3.55 in 1993‐99 to 6.01 in 2018–20, with most of that increase occurring after 2014. Twice as many young adults in 2018–20 (vs. 1993–99) reported spending half or more days in poor mental health, and 57% more were in poor mental health most of the time in 2018–20 compared to 2010–14. Increases were also considerable among prime-age adults (ages 26–49), where 66% more spent most of their days in poor mental health in 2018–20 compared to 1993–99 (see Table 1 and Fig. 1).

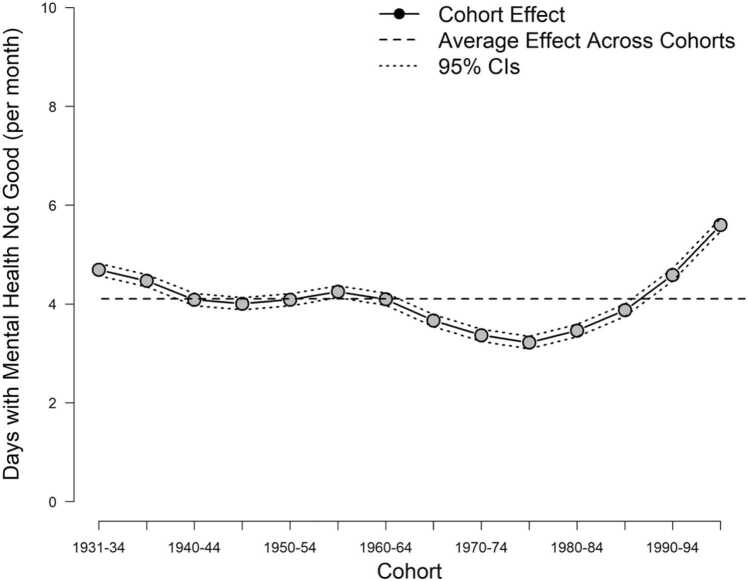

In APC analyses, the effect was primarily due to birth cohort. The number of poor mental health days was lowest among Silents born 1940–1944 (M = 3.27, and with 10% reporting poor mental health on most days) and highest among Generation Z (M = 5.15 and 17% reporting poor mental health on most days; see Fig. 2). The cohort difference in poor mental health days was larger among women than among men; for example, the number of women reporting spending half or more days in poor mental health nearly doubled (from 11% to 21%), while for men it increased 71% (from 7% to 12%). Increases were larger among White Americans (from 9% to 18%) than among Black Americans (10–16%), Hispanic Americans (11–15%), or Asian Americans (5–7%).

Fig. 2.

Days of poor mental health, cohort effects in APC analyses controlling for age and time period.

There was also a period effect across all ages and generations, with the lowest number of poor mental health days among all U.S. adults in 1993 (M = 3.19, 10% reporting poor mental health on most days) and the highest number in 2019 (M = 4.36, 13% on most days; see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Poor mental health days, period effects in APC analyses controlling for age and cohort.

2. Study 2

Study 2 relies on the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), administered by the National Center for Health Statistics division of the CDC. Between 1997 and 2018, the survey included the Kessler-6, a 6-item measure of mental distress including symptoms of sadness and worthlessness. Because the Kessler-6 is a multi-item and validated scale of mental distress, it is a more precise measure of mental health than the single item on general poor mental health days analyzed in Study 1.

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

U.S. adult participants (n = 359,393) took part in the NHIS between 1997 and 2018. The design is cross-sectional, with different participants assessed each year. The NHIS is conducted as a face-to-face interview. Response rates were regularly over 70%. Data are publicly available and de-identified. The analysis of de-identified, publicly available data does not constitute human subjects research as defined in 45 CFR 46.102.

2.1.2. Measures

Participants completed the Kessler-6 (K6), a valid and reliable scale [15] that asks respondents how frequently they experienced symptoms of mental distress during the past 30 days. Participants were asked, “During the PAST 30 DAYS, how often did you feel … 1) so sad that nothing could cheer you up, 2) nervous, 3) restless or fidgety, 4) hopeless, 5) that everything was an effort, 6) worthless. Response choices were recoded as: “all of the time” = 4, “most of the time” = 3, “some of the time” = 2, “little of the time” = 1, and “none of the time” = 0. The possible range of scores on the K6 was 0–24. Scores of 13 and over indicate serious mental distress and scores of 5 and over indicate moderate or serious mental distress [24]. We also examined the percentage of participants who reported experiencing each of the six symptoms at least some of the time. The NHIS stopped using the Kessler-6 in 2018 as the survey was redesigned in 2019.

2.1.3. Data analysis

Sample weights were applied to make the data nationally representative of the U.S. adult population. Participants were grouped by age using the same three age groups (18–25, 26–49, and 50 +) used in Study 1. Differences across time periods were compared using t-tests, d (difference in terms of standard deviations), and, for the percent with moderate or high mental distress and individual items, relative risk. APC analyses were performed using the same constraints as in Study 1.

2.1.4. Results

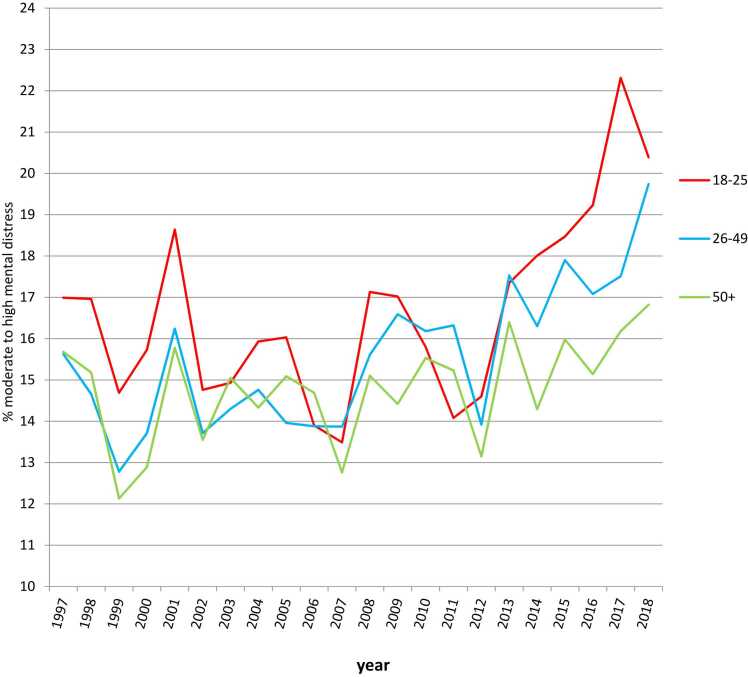

American adults in 2017–18 reported more symptoms of mental distress than those in the 1990s and 2000s. The increase was the most pronounced among young adults ages 18–25, where nearly all of the increase occurred after 2011. In 2017–18, 34% more young adults met criteria for moderate to high mental distress than did in 2010–14. Moderate to high distress also increased among prime-age adults ages 26–49, with a 30% increase between 1997–99 and 2017–18 and a 16% increase between 2010–14 and 2017–18 (see Table 2 and Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Mental distress, by age group and time period.

| 1997–99 | 2000–09 | 2010–14 | 2015–16 | 2017–18 | 1990 s v. 2017–18 | 2010–14 v. 2017–18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean K6 | |||||||

| 18–25 | 2.53 (3.51) 11652 |

2.45 (3.59) 34773 |

2.54 (3.56) 18680 |

2.88 (3.89) 6747 |

3.04 (3.88) 4784 |

0.14* | 0.14* |

| 26–49 | 2.35 (3.70) 48545 |

2.35 (3.76) 130594 |

2.54 (3.87) 67598 |

2.71 (3.92) 24099 |

2.88 (3.99) 18459 |

0.14* | 0.09* |

| 50 + | 2.25 (3.82) 37640 |

2.27 (3.84) 116612 |

2.38 (3.92) 76340 |

2.47 (3.94) 33299 |

2.60 (3.97) 27207 |

0.09* | 0.06* |

| All | 2.34 (3.72) 97837 |

2.34 (3.76) 281979 |

2.47 (3.85) 162618 |

2.62 (3.93) 64145 |

2.77 (3.97) 50450 |

0.11 * | 0.08* |

| % Moderate or high | |||||||

| 18–25 | 16.20% 11652 |

15.75% 34773 |

15.96% 18680 |

18.85% 6747 |

21.36% 4784 |

1.32 (1.23, 1.41) | 1.34 (1.26, 1.43) |

| 26–49 | 14.35% 48545 |

14.66% 130594 |

16.04% 67598 |

17.48% 24099 |

18.64% 18459 |

1.30 (1.25, 1.35) | 1.16 (1.22, 1.20) |

| 50 + | 14.31% 37640 |

14.37% 116612 |

14.90% 76340 |

15.55% 33299 |

16.51% 27207 |

1.15 (1.11, 1.19) | 1.11 (1.07, 1.14) |

| All | 14.61% 97837 |

14.71% 281979 |

15.54% 162618 |

16.80% 64145 |

18.03% 50450 |

1.23 (1.21, 1.26) | 1.60 (1.14, 1.86) |

| % Sad | |||||||

| 18–25 | 10.98% 11680 |

10.18% 34844 |

9.59% 18721 |

10.60% 6771 |

11.40% 4796 |

1.04 (0.95, 1.14) | 1.19 (1.09, 1.30) |

| 26–49 | 10.61% 48668 |

10.83% 130965 |

10.71% 67754 |

10.22% 24174 |

10.39% 18517 |

0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) |

| 50 + | 12.45% 37835 |

12.47% 117238 |

12.44% 76663 |

12.30% 33441 |

12.73% 27326 |

1.02 (0.98, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.07) |

| All | 11.31% 98183 |

11.37% 283047 |

11.30% 162618 |

11.21% 64145 |

11.60% 50450 |

1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) |

| % Nervous | |||||||

| 18–25 | 17.45% 11677 |

17.47% 34844 |

19.18% 18721 |

24.02% 6770 |

25.68% 4796 |

1.47 (1.38, 1.57) | 1.34 (1.27, 1.42) |

| 26–49 | 16.25% 48667 |

16.05% 130986 |

17.66% 67766 |

19.43% 24170 |

21.87% 18517 |

1.35 (1.30, 1.40) | 1.24 (1.20, 1.28) |

| 50 + | 15.61% 37838 |

14.95% 117227 |

15.22% 76662 |

15.76% 33438 |

16.65% 27327 |

1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | 1.09 (1.06, 1.13) |

| All | 16.20% 98182 |

15.84% 283057 |

16.82% 163149 |

18.42% 64378 |

20.00% 50641 |

1.24 (1.21, 1.27) | 1.1.9 (1.17, 1.21) |

| % Restless | |||||||

| 18–25 | 18.94% 11676 |

19.59% 34838 |

19.66% 18718 |

21.79% 6767 |

23.57% 4798 |

1.25 (1.17, 1.33) | 1.20 (1.13, 1.27) |

| 26–49 | 17.72% 48655 |

17.58% 130957 |

18.92% 67744 |

20.76% 24174 |

22.56% 18509 |

1.27 (1.23, 1.32) | 1.19 (1.16, 1.23) |

| 50 + | 15.96% 37812 |

16.15% 117192 |

17.02% 76646 |

17.70% 33430 |

18.99% 27317 |

1.19 (1.15, 1.23) | 1.12 (1.08, 1.15) |

| All | 17.27% 98143 |

17.33% 282987 |

18.21% 163108 |

19.52% 64371 |

21.07% 50624 |

1.22 (1.19, 1.25) | 1.16 (1.14, 1.18) |

| % Hopeless | |||||||

| 18–25 | 5.44% 11671 |

5.45% 34841 |

6.16% 18719 |

6.62% 6764 |

7.22% 4795 |

1.33 (1.17, 1.51) | 1.17 (1.04, 1.32) |

| 26–49 | 5.80% 48660 |

6.29% 130943 |

6.80% 67735 |

7.16% 24162 |

7.26% 18509 |

1.25 (1.18, 1.33) | 1.07 (1.01, 1.13) |

| 50 + | 5.91% 37811 |

6.37% 117168 |

6.86% 76605 |

7.16% 33419 |

7.15% 27311 |

1.21 (1.14, 1.28) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.10) |

| All | 5.78% 98142 |

6.20% 282952 |

6.73% 163059 |

7.09% 64345 |

7.20% 50615 |

1.25 (1.20, 1.30) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) |

| % Everything an effort | |||||||

| 18–25 | 14.64% 11666 |

14.12% 34821 |

15.53% 18695 |

18.01% 6759 |

19.86% 4790 |

1.36 (1.26, 1.46 | 1.28 (1.20, 1.37) |

| 26–49 | 12.71% 48623 |

13.59% 130851 |

15.62% 67689 |

17.25% 24140 |

19.06% 18496 |

1.50 (1.44, 1.56) | 1.22 (1.18, 1.26) |

| 50 + | 12.41% 37806 |

13.25% 117109 |

14.50% 76557 |

15.54% 33398 |

16.69% 27296 |

1.35 (1.30, 1.40) | 1.15 (1.12, 1.19) |

| All | 12.88% 98095 |

13.54% 282781 |

15.12% 162941 |

16.58% 64297 |

18.08% 50582 |

1.40 (1.37, 1.44) | 1.20 (1.17, 1.22) |

| % Worthless | |||||||

| 18–25 | 4.10% 11676 |

4.35% 34832 |

4.34% 18715 |

5.96% 6762 |

6.56% 4794 |

1.60 (1.40, 1.84) | 1.51 (1.34, 1.72) |

| 26–49 | 4.64% 48649 |

4.95% 130895 |

5.25% 67718 |

5.58% 24153 |

5.67% 18503 |

1.22 (1.14, 1.31) | 1.08 (1.01 1.15) |

| 50 + | 5.28% 37798 |

5.54% 117131 |

5.75% 76573 |

5.87% 33399 |

6.06% 27292 |

1.15 (1.08, 1.22) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) |

| All | 4.79% 98123 |

5.09% 282858 |

5.34% 163006 |

5.76% 64314 |

5.97% 50589 |

1.25 (1.19, 1.30) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.16) |

NOTES 1. For total mean, numbers are mean, (SD), n and effect sizes are d (difference in standard deviations). * = t-test yields p < .05. 2. For percents, numbers are percent, n and effect sizes are relative risk and 95% confidence interval. RR’s with confidence interval not including 1 are in bold.

Fig. 4.

Percent of U.S. adults with moderate or high mental distress, by age group and year, 1997–2018.

In APC analyses, there were both cohort and period effects. Mental distress declined from the earliest cohorts born before 1919 (22.8% with moderate to high mental distress) to those born in the early 1940s (15.5%). Mental distress then increased during the Baby Boom cohorts of the late 1940s to the early 1960s (18.2% for those born 1955–59), declined slightly during the Generation X birth years of the late 1960s and 1970s (16.9%, 1970–74), and then rose during the Millennial and Generation Z birth years of the 1980s and 1990s (20.3% 1995–02; see Fig. 5). The rise in moderate to high mental distress between those born 1940–44 and 1995–02 was similar in magnitude by gender (from 18.2% to 23.7% for women, 12.2–16.5% for men) and larger for Blacks (17.6–21.3%) and Whites (15.1–20.8%) than for Hispanics (17.8–20.1%) or Asians (8.9–10.9%). There were also period effects, with mental distress among U.S. adults lowest in 1999 and 2007 and higher in 2001 and 2010 and the years 2013 and 2015–2018 (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Moderate or high mental distress, cohort effects in APC analyses controlling for age and time period.

Fig. 6.

Moderate or high mental distress, period effects in APC analyses controlling for age and cohort.

There were also notable differences in trends based on specific symptoms. The largest changes among young adults appeared for feeling worthless and nervous, and the smallest increases in feeling sad (see Table 2).

3. Study 3

Study 3 draws on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES), administered by the CDC. Since its 2005–06 wave, NHANES has included the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), a measure of depressive symptoms. As the PHQ-9 is meant to serve as a screening tool for major depression, it is a more specific measure of depression than the measures used in Studies 1 and 2.

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

U.S. adult participants (n = 39,467) took part in the NHANES, administered by the CDC, between 2005 and early 2020. The design is cross-sectional, with different participants assessed each year. NHANES data are conducted during two-year periods, with the depression measure included beginning in 2005–06; the most recent two-year data collection period of 2019–2020 was not completed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so the survey administrators combined the data from 2017 to early 2020, with the 2020 data collected before the pandemic significantly impacted the U.S. Response rates were 50% or greater. Interviews were conducted in person. Data are publicly available and de-identified. The analysis of de-identified, publicly available data does not constitute human subjects research as defined in 45 CFR 46.102.

3.1.2. Measures

Adult NHANES participants completed the PHQ-9, a measure designed to screen for symptoms of depression experienced in the last two weeks. The items are based on the DSM criteria for major depressive episode and include symptoms such as “little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” “trouble concentrating on things,” and “thoughts of being better off dead” (alpha = 0.84). Scores can range from 0 to 27, with scores above 10 indicating moderate or severe depression.

We also examined the percent acknowledging any suicidal ideation using the ninth item of the PHQ (answering anything other than “not at all” to having “thoughts of being better off dead”). Previous studies have shown that any positive response on this item is indicative of elevated risk for suicide deaths [19], [31]; an additional study demonstrated its reliability in predicting both suicide attempts and deaths across age groups [27].

3.1.3. Data analysis

At the recommendation of the survey administrators, sample weights were applied to make the data nationally representative of the population. Participants were grouped by age using the same three age groups (18–25, 26–49, and 50 +) used in Studies 1 and 2. Differences across time periods were compared using t-tests, d (difference in terms of standard deviations), and, for the percent with moderate to severe depression, relative risk. Because single-item measures generally have low resolution, we analyzed suicidal ideation assessed by the ninth item of the PHQ as a dichotomous rather than continuous variable; this allowed us to detect the presence of suicidal ideation but not the degree of ideation. Results were similar when the continuous variable was used. APC analyses were performed using the same constraints as in Studies 1 and 2.

3.1.4. Results

Symptoms of depression among American adults rose between 2005–06 and 2017–20, as did the number of adults meeting criteria for moderate to severe depression and those acknowledging suicidal ideation. Moderate to severe depression increased in all age groups between 2005–06 and 2007–08 and stayed elevated among young adults and older adults while declining among prime-age adults. Rates of depression then rose among young adults and prime-age adults between 2015–16 and 2017–20 (see Table 3 and Fig. 7). The number of young adults with moderate to severe depression more than doubled between 2005–06 and 2017–20 (RR = 2.40), and increased by 50% among prime-age adults and older adults. Suicidal ideation jumped 76% among young adults while changing little among prime-age and older adults. Between 2013–14 and 2017–20, moderate to severe depression increased 36% among young adults, but changed little among prime-age and older adults.

Table 3.

Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, by age group and time period.

| 2005–06 | 2007–08 | 2009–10 | 2011–12 | 2013–14 | 2015–16 | 2017–20 | 2005–06 v. 2017–20 | 2013–14 v. 2017–20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean PHQ-9 | |||||||||

| 18–25 | 2.69 (3.28) 1065 |

3.15 (3.57) 743 |

3.38 (3.60) 824 |

3.29 (4.18) 829 |

3.02 (3.66) 855 |

3.03 (3.66) 720 |

3.62 (4.36) 1108 |

0.24* | 0.15* |

| 26–49 | 2.63 (3.65) 1839 |

3.26 (4.24) 2019 |

3.34 (4.24) 2131 |

2.96 (4.31) 1796 |

3.01 (4.24) 2040 |

3.05 (4.04) 1956 |

3.20 (4.02) 2947 |

0.15* | 0.04* |

| 50 + | 2.51 (3.59) 1895 |

2.97 (3.99) 2653 |

2.74 (3.96) 2591 |

2.85 (4.11) 2300 |

3.30 (4.42) 2477 |

3.14 (4.16) 2458 |

3.05 (4.07) 4221 |

0.14* | -0.06* |

| All | 2.59 (3.58) 4799 |

3.12 (4.05) 5415 |

3.09 (4.05) 5546 |

2.96 (4.20) 4925 |

3.14 (4.24) 5372 |

3.09 (4.05) 5134 |

3.19 (4.09) 8276 |

0.16* | 0.01 |

| % moderate to high | |||||||||

| 18–25 | 4.41% 1065 |

7.19% 743 |

7.07% 824 |

7.78% 829 |

7.49% 855 |

7.42% 720 |

10.57% 1108 |

2.40 (1.72, 3.32) | 1.36 (1.02, 1.83) |

| 26–49 | 5.71% 1839 |

8.90% 2019 |

8.50% 2131 |

8.37% 1796 |

8.19% 2040 |

6.94% 1956 |

8.50% 2947 |

1.49 (1.20, 1.86) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.26) |

| 50 + | 5.34% 1895 |

7.51% 2653 |

7.11% 2591 |

7.53% 2300 |

9.45% 2477 |

7.80% 2458 |

8.07% 4221 |

1.51 (1.22, 1.88) | 0.86 (0.73, 1.00) |

| All | 5.38% 4799 |

8.09% 5415 |

7.71% 5546 |

7.90% 4925 |

8.64% 5372 |

7.40% 5134 |

8.59% 8276 |

1.60 (1.39, 1.83) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.11) |

| % with suicidal ideation | |||||||||

| 18–25 | 2.58% 1066 |

3.55% 743 |

3.26% 825 |

3.67% 830 |

3.61% 856 |

4.13% 720 |

4.54% 1110 |

1.78 (1.12, 2.82) | 1.24 (0.80, 1.93) |

| 26–49 | 3.00% 1845 |

3.14% 2026 |

3.27% 2132 |

3.31% 1798 |

2.62% 2041 |

3.42% 1962 |

2.78% 2952 |

0.93 (0.67, 1.30) | 1.07 (0.76, 1.50) |

| 50 + | 3.06% 1923 |

3.63% 2672 |

3.08% 2605 |

3.07% 2312 |

3.90% 2493 |

3.09% 2475 |

3.35% 4234 |

1.10 (0.81, 1.48) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.11) |

| All | 2.96% 4834 |

3.40% 5441 |

3.18% 5562 |

3.26% 4940 |

3.34% 5390 |

3.36% 5157 |

3.29% 8296 |

1.11 (0.91, 1.36) | 0.99 (0.82, 1.19) |

NOTES: 1. For days per month, numbers are mean, (SD), n and effect sizes are d (difference in standard deviations). * = t-test yields p < .05. 2. For percentage with more than half of days, numbers are percent, n and effect sizes are relative risk and 95% confidence interval. RR’s with confidence interval not including 1 are in bold.

Fig. 7.

Percent of U.S. adults with moderate to severe depression, by age group and year, 2005–2020.

Consistent with this pattern, APC analyses showed a period effect between 2005–06 and 2007–08 and a cohort effect between Millennials born 1990–94 (8.2% with moderate to severe depression) and Gen Z′ers born 1995–02 (10.4%; see Fig. 8, Fig. 9). There was also a cohort effect with higher rates of depression among Boomers (11.7% with moderate to severe depression among those born in the 1950s, compared to 7.8% of Silents born 1934 or before). The cohort trends were relatively consistent across gender, but varied somewhat in their peaks and valleys based on race: for Whites, 10.0% for those born 1940–44, 12.8% born 1960–64, 9.3% born 1970–74, and 12.3% born 1995–02; for Blacks, 9.6% born 1935–39, 11.4% 1950–54, 9.6% 1975–79, 10.1% 1995–02. The period trends were more pronounced among women (9.0% in 2005–06, 13.5% in 2007–08, 10.8% in 2015–16, and 12.2% in 2017–20) than among men (7.1% in 2005–06, 7.4% in 2007–08, 7.3% in 2015–16, and 7.5% in 2017–20).

Fig. 8.

Moderate to severe depression, cohort effects in APC analyses controlling for age and time period.

Fig. 9.

Moderate to severe depression, period effects in APC analyses controlling for age and cohort.

4. Discussion

Across three nationally representative datasets employing three different measures (N = 9.2 million), American adults are in increasingly poor mental health. They reported more days of poor mental health, more mental distress, more symptoms of depression, and more suicidal ideation in recent years compared to past decades. Although the pattern and size of the increase varied across the datasets, the rise in poor mental health was generally larger among young and prime-age adults (ages 18–49) than among older adults (ages 50 and up). Nearly all of the increase took place before the COVID-19 pandemic.

These results suggest that the increase in mood disorder symptoms identified among adolescents and college students [11], [40] began to extend to U.S. adults as a whole after 2015, with larger increases among younger adults. Although some previous research suggested the increase in mood disorder indicators was limited to those ages 25 and under and was mostly due to cohort [35], these results with data after 2016 suggest a broader trend in poor mental health extending up the age scale to adults in their prime (26−49) and appearing as both a cohort and period effect.

Generation Z (born 1995–2012), a generation with markedly higher depression and self-harm as adolescents, is apparently continuing to struggle with mood disorder symptoms as they navigate adulthood. Millennials (born 1980–1994), who now dominate the 26–49 age group, are also beginning to show signs of poor mental health after evincing lower rates of suicide and depression as adolescents [33]. Generation X (born 1965–1979), despite experiencing higher depression and suicide rates in their youth [18], as adults generally have lower rates of depression than the generations before and after them. Boomers (born 1946–1964) are notably higher in mental distress and depression than other generations but, after 2015, show a less pronounced increase in general poor mental health than younger adults.

These analyses did not attempt to identify the cause of the increase in mood disorder symptoms. However, some potential explanations seem less plausible, although this discussion is necessarily speculative. The increase in poor mental health continued during a period of economic expansion in the U.S. economy after 2011, which was accompanied by falling unemployment. This suggests that the trends after 2011 are not due to cyclical economic factors, though the increases in mental distress and depression during the recession years of 2007–2010 appearing in Studies 2 and 3 may be partially due to economic factors. The COVID-19 pandemic also does not appear to be a primary cause. Two out of the three datasets collected all of their data before the COVID-19 pandemic had a widespread impact, and the one dataset with pandemic data (BRFSS) showed stability or decline in poor mental health between 2019 and 2020. It also seems unlikely that the rise is due to willingness to admit to mental health issues, given that suicide – a behavior linked to mood disorders that is not subject to self-report biases – also increased among these age groups over the same time period [35].

The trend lines show a general rise in poor mental health since the 1990s and a more pronounced change since the mid‐2010s. Especially among younger adults, the increases appear to pre-date the election of Donald Trump, suggesting his presidency was not the initiating cause. The increases coincide with several factors that (speculatively) may be related, including the rise of a more contentious social media culture [14], increasing political polarization [20], and an increase in electronic communication at the expense of face-to-face social interaction [37] and potentially physical activity [30], sunlight exposure [17], and sleep quality and duration [12], [7], which are in turn linked to mood disorder symptoms [4]. However, it is not possible to definitively identify a cause of the trends with these data. Future studies should assess if these changes in political environment and social connectedness are associated with increases in poor mental health on an individual basis.

This work comes with significant limitations, especially around measurement. None of our outcome measures involves a clinically diagnosed mental disorder, but instead assesses self-reported symptoms of mental disorders. With that said, self-reported, subsyndromal symptoms of mental disorders are objectively distressing and impairing in their own right, and can be associated with outcomes as severe as suicide [28]. In addition, the measures in Studies 2 and 3 did assess cardinal symptoms of major depressive disorder (Studies 2 and 3) and generalized anxiety disorder (Study 2). Moreover, Study 3′s measure assessed each of the nine possible MDD symptoms as described in DSM-5 [1], including suicidal ideation.

Our results highlight that even under the best of conditions in the U.S. (e.g., periods of economic prosperity), mental health is suboptimal. Regardless of the cause of this decline in general mental health, the country is not making needed progress in availability and quality of mental health care. Availability of general mental health resources, let alone specialty mental health care, is currently limited for the general population, but is especially lacking for low-income and other disadvantaged groups [8].

Our results additionally imply several downstream consequences for medical and economic costs. As discussed previously, mental health has a clear connection to physical health, with mental disorders being heavily comorbid with a variety of medical conditions and often resulting in premature mortality. Given the reported increases in poor mental health, we expect that its negative impact on physical health has also increased. Similarly, the economic cost of mental disorders, which already constituted a significant burden both nationally [16] and globally [32] in the 2000s, has likely grown over the last decade.

Disclosures

J.M.T. has done legal consulting for firms including Bergman & Little, Beasley Allen, Motley Rice, and a consortium of state Attorneys General on the topic of social media and mental health and receives royalties from books and speaking honoraria. T.E.J. has done legal consulting for firms such as Bergman & Little on the topic of social media and mental health and receives royalties from books and speaking honoraria. C.M. and N.S.U. have nothing to disclose.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Jean M. Twenge reports a relationship with Bergman & Little that includes: consulting or advisory. Jean M. Twenge reports a relationship with Beasley Allen that includes: consulting or advisory. Jean M. Twenge reports a relationship with Motley Rice LLC that includes: consulting or advisory. Jean M. Twenge reports a relationship with Consortium of State Attorney Generals that includes: consulting or advisory. Thomas E. Joiner reports a relationship with Bergman & Little that includes: consulting or advisory. Co-authors receive royalties from books and speaking honoraria - J.M.T & T.E.J.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D. C: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andresen E.M., Catlin T.K., Wyrwich K.W., Jackson-Thompson J. Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health-related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:339–343. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates D., Maechler M., Bolker B., Walker S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R Package Version. 2014;1:1–7. 〈http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4〉 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandari P.M., Neupane D., Rijal S., Thapa K., Mishra S.R., Poudyal A.K. Sleep quality, internet addiction and depressive symptoms among undergraduate students in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:106. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1275-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bubonya M., Cobb-Clark D.A., Wooden M. Mental health and productivity at work: does what you do matter? Labour Econ. 2017;46:150–165. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell W.K., Campbell S., Siedor L.E., Twenge J.M. Generational differences are real and useful. Ind Organ Psychol: Perspect Sci Pract. 2015;8:324–408. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter B., Rees P., Hale L., Bhattacharjee D., Paradkar M.S. Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings J.R., Allen L., Clennon J., Ji X., Druss B.G. Geographic access to specialty mental health care across high- and low-income US communities. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):476–484. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis D.S., Washburn T., Lee H., Smith K.R., Kim J., Martz C.D., et al. Highly public anti-Black violence is associated with poor mental health days for Black Americans. PNAS Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019624118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Druss B.G., Zhao L., Von Esenwein S., Morrato E.H., Marcus S.C. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49(6):599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffy M.E., Twenge J.M., Joiner T.E. Trends in mood and anxiety symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among US undergraduates, 2007-2018: Evidence from two national surveys. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65:590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford E.S., Cunningham T.J., Croft J.B. Trends in self-reported sleep duration among U.S. adults from 1985 to 2012. Sleep. 2015;38:829–832. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagné T., Schoon I., Sacker A. Trends in young adults’ mental distress and its association with employment: Evidence from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1993–2019. Prev Med: Int J Devoted Pract Theory. 2021;150 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haidt, J. , 2022. Why the past 10 years of American life have been uniquely stupid. The Atlantic.

- 15.Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.-L.T., et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler R.C., Heeringa S., Lakoma M.D., Petukhova M., Rupp A.E., Schoenbaum M., et al. Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):703–711. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larson L.R., Szczytko R., Bowers E.P., Stephens L.E., Stevenson K.T., Floyd M.F. Outdoor time, screen time, and connection to nature: troubling trends among rural youth? Environ Behav. 2019;51(8):966–991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewinsohn P., Rohde P., Seeley J., Fischer S. Age-cohort changes in the lifetime occurrence of depression and other mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:110–120. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louzon S.A., Bossarte R., McCarthy J.F., Katz I.R. Does suicidal ideation as measured by the PHQ-9 predict suicide among VA patients? Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):517–522. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macy M.W., Ma M., Tabin D.R., Gao J., Szymanski B.K. Polarization and tipping points. PNAS. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2102144118. e2102144118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller B.J., Paschall C.B., Svendsen D.P. Mortality and medical comorbidity among patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1482–1487. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mojtabai R., Olfson M., Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orji C.C., Ghosh S., Nwaobia O.I., Ibrahim K.R., Ibiloye E.A., Brown C.M. Health behaviors and health-related quality of life among US adults aged 18–64 years. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(4):529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochaska J.J., Sung H.-Y., Max W., Shi Y., Ong M. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:88–97. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna Austria: 2014. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [computer software] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajan S., McKee M., Rangarajan S., Bangdiwala S., Rosengren A., Gupta R., et al. Association of symptoms of depression with cardiovascular disease and mortality in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(10):1052–1063. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossom R.C., Coleman K.J., Ahmedani B.K., Beck A., Johnson E., Oliver M., et al. Suicidal ideation reported on the PHQ9 and risk of suicidal behavior across age groups. J Affect Disord. 2017;215:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadek N., Bona J. Subsyndromal symptomatic depression: a new concept. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12:30–39. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<30::AID-DA4>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaie K.W. Beyond calendar definitions of age, time, and cohort: the general developmental model revisited. Dev Rev. 1986;6:252–277. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serrano-Sanchez J., Martí-Trujillo S., Lera-Navarro A., Dorado-García C., González-Henríquez J.J., Sanchís-Moysi J. Associations between screen time and physical activity among Spanish adolescents. PloS One. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024453. e24453–e24453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon G.E., Rutter C.M., Peterson D., Oliver M., Whiteside U., Operskalski B., et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(12):1195–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trautmann S., Rehm J., Wittchen H.U. The economic costs of mental disorders: do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders? EMBO Rep. 2016;17(9):1245–1249. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Twenge J.M. Time period and birth cohort differences in depressive symptoms in the U.S., 1982-2013. Soc Indic Res. 2015;121:437–454. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Twenge J.M. Atria Books; New York: 2023. Generations: the real differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers and Silents—and What They Mean for America’s Future. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Twenge J.M., Cooper A.B., Joiner T.E., Duffy M.E., Binau S.G. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128:185–199. doi: 10.1037/abn0000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Twenge J.M., Joiner T.E., Rogers M.L., Martin G.N. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Twenge J.M., Spitzberg B.H. Declines in non-digital social interaction among Americans, 2003-2017. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2020;50:363–367. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y., Land K.C. Age–period–cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys: fixed or random effects? Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36:297–326. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y., Land K.C. Chapman and Hall; Boca Raton, FL: 2013. Age-period-cohort analysis: new models, methods, and empirical applications. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plemmons G., Hall M., Doupnik S., Gay J., Brown C., Browning W., et al. Hospitalization for Suicide Ideation or Attempt: 2008-2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]