Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the factors that influence the acquisition of personal ophthalmic instruments (POIs) among optometry students in Ghana. Participant characteristics and patterns of ophthalmic instrument acquisition were collected using a structured questionnaire. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to examine the relationships between factors influencing POI acquisition.

Results description

Overall, 60.2% of students did not have their own ophthalmic instruments. Slightly more than one third (39.8%) owned a POI that was primarily an ophthalmoscope. Multiple logistic regression showed that financial difficulty (AOR: 0.45, CI: 0.29–0.71, p = 0.001), and lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality (AOR: 0.26, CI: 0.10–0.66, p = 0.005) were significantly associated with lower odds of POI acquisition. About 63.3% of students cited financial difficulty as the main barrier to POI acquisition. The findings call for cost adjustments by stakeholders and increase awareness to optimize POIs acquisition among students. Taken together, the findings aim to improve clinical training and reduce disparities in optometry education among optometry students in Ghana.

Keywords: Ophthalmoscope, Retinoscope, Access, Barriers, Facilitators , Clinical training, Ghana

Introduction

Optometry students form the backbone of the optometrists’ workforce in Ghana [1–4]. Optometrists specialise in eye care and are uniquely positioned to manage visual disorders of infectious and non-infectious origin among people of all ages using pharmacotherapeutic and optical approaches [5, 6]. They play a critical role in addressing vision impairment and blindness that respectively affect an estimated 2.2 billion and 43.3 million people globally [7, 8]. Together, this role is vital to ensure the overall visual health and quality of life of all persons [9, 10].

Annually, optometry students are enrolled into the Ghana Optometric Association, the professional optometric body responsible for the advancement of optometry in Ghana following the completion of a six-year Doctor of Optometry program [11, 12]. Unlike other medical training programmes, optometry training is only offered at two schools in Ghana: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) and the University of Cape Coast (UCC). Given their pivotal role in advancing the professional landscape of optometry in Ghana, it is crucial that optometry students in these institutions have access to high-quality clinical training.

Central to the training of optometry students is the use of personal ophthalmic instruments (POIs); this essential arsenal is used to routinely detect potential ocular lesions. In particular, the ophthalmoscope is a multipurpose diagnostic aid for examining the anterior and posterior segments of the eye whereas retinoscope are useful in the objective detection of uncorrected refractive errors. Nonetheless, ophthalmoscope also facilitate the detection of refractive errors in the absence of retinoscope and are used to screen for refractive errors in children and uncooperative patients [13]. Taken together, ophthalmoscope is therefore used as an object of representation for estimating students’ ownership of ophthalmic instruments in the jurisdiction of the current research.

Previous studies have revealed the shortage of ophthalmic instruments among optometrists in Ghana, which impedes the provision of quality eye care services [5, 6, 14]. However, evidence on the adequacy of ophthalmic instruments for training optometry students in Ghana remains unclear. Currently, the student population in these preeminent schools of optometry has seen an exponential growth rate and this has resulted in a high student-to-instrument ratio [1–4]. This observation has prompted optometry educators (lecturers, senior colleagues and practising optometrists) to advocate for optometry students acquiring their own POIs. This will collectively help to complement their institutional practical training and, importantly, allow them to hone their skills through continuous practice during optometric internships and outreach programmes.

However, to date, there are no institutional policies mandating that optometry students in Ghana acquire their own POIs, nor are there standardised pathways for acquiring them. The current cost of POIs is high, with a standard ophthalmic diagnostic set containing an ophthalmoscope and a retinoscope priced at 750 USD before tax. In contrast, most optometry students solely rely on stipends from mainly parents which may posit a financial barrier to POI acquisition. The proportion of optometry students who own POIs and the challenges they face in securing these ophthalmic instruments remain unclear. Therefore, understanding the patterns of POI acquisition and the factors influencing POI ownership among optometry students is crucial for institutional planning to enhance the quality of optometric training.

To this end, this study examines the factors that influence the acquisition of POIs among optometry students in Ghana. The study revealed that over 60% did not have POIs and that was mainly influenced by financial difficulties and lack of access to information on the quality of POIs. Collectively, the above findings suggest that stakeholders should increase awareness of the quality of ophthalmic instruments and subsidise their cost to improve student access and optimise clinical optometry training in Ghana.

Materials and methods

Study design, population, and setting

This multi-centre, cross-sectional study was conducted among optometry students enrolled at the Schools of Optometry and Visual Sciences at KNUST in Kumasi and UCC in Cape Coast, Ghana, from January to August 2023. The estimated number of Optometry students in these schools were 1,061 as at the time of the study. Based on our sample calculation, 485 students were purposively sampled from the two institutions: 283 from KNUST and 202 from UCC, representing a 100% response rate.

Sample size and sampling

Given the absence of previous data, we used the Cochran single proportion equation (N = z²p(1-p)/e²), where N is the sample size, z² is the abscissa of the normal curve that cuts an area α at the tail or standard normal deviation at a 95% confidence interval, and p is the assumed POI acquisition rate (50%, with a 20% non-response rate yielding a total sample size of 462). However, we collated data from 485 participants, which increases the statistical power of the study and enables us to detect any differences between groups with and without POIs. Furthermore, to ensure representativeness, we purposively sampled optometry students in both clinical and non-clinical years, since they are the focus of the discussion.

Data collection

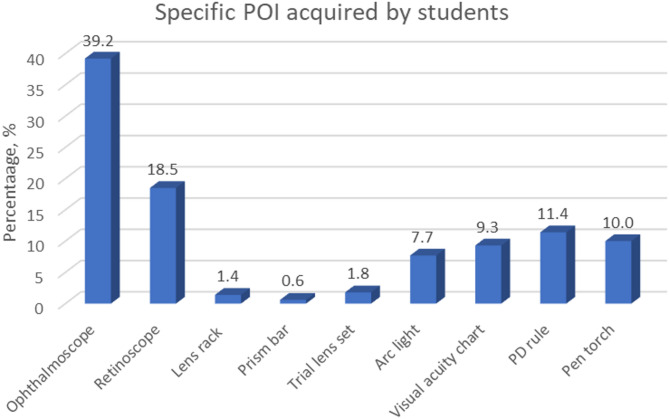

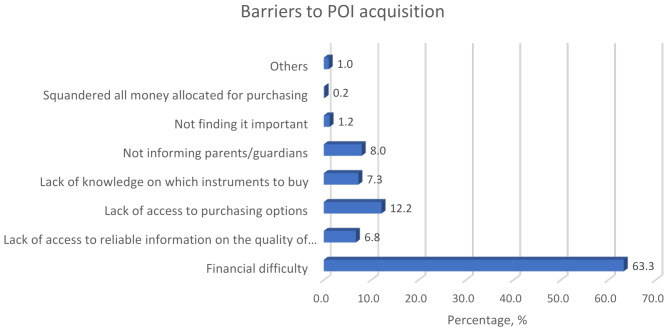

Data were collected in person using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was pre-tested with 15 optometry students and revised as necessary to ensure clarity. The questionnaire covered four broad areas: Participant characteristics (age, sex, institution of study), type of ophthalmic instruments (as shown in Fig. 1), facilitators (year of study, frequency of use of POI, importance POI acquisition, advised or prompted to acquire POI, year advised or prompted to acquire POI, source of prompt and/or advice to acquired POI), and barriers (financial difficulties, lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality, lack of access to purchase options, lack of knowledge on which instruments to purchase, lack of information from parents or guardians, not considering it important to purchase POI, wasting all money allocated for purchase) to ophthalmic instrument purchase (as shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Specific personal ophthalmic instruments acquired by optometry students

Fig. 2.

Barriers to acquisition of personal ophthalmic instrument by optometry students

Statistical analysis

The survey data were imported into Microsoft Excel and checked for duplicates. The cleaned dataset was imported into Statistical Package and Service Solution version 25 compatible with Windows 11 for formal analysis. The distribution of the data was examined using Chi-square statistics, and the association between explanatory and response variables was determined using bivariate and multivariate logistic regression at a significance of p ≤ 0.05. For analytical purposes having an ophthalmoscope was considered the main outcome variable. The ophthalmoscope was used because of its basic use in clinical practice by both clinical and non-clinical year optometry students, with the former using it for demonstration purposes and/or clinical rotations and the latter using it for in-house clinical practice and during outreach or clinical rotations. Furthermore, the ophthalmoscope was also the commonly owned POI in this study (Fig. 1).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana (CHRPE/AP/407/23) after formalized institutional approval from authorities of the Departments of Optometry and Visual Sciences at KNUST and UCC. The study obtained informed consent from all student participants and adhered to the Tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Description of the sample

Table 1 shows the distribution of participants’ characteristics, facilitators, and barriers by whether or not they acquired POI. Of the 485 optometry students enrolled, there was a significant age (p = 0.016) but not sex (p = 0.341) differences among participants with and without their own POI. Students in clinical years were significantly more likely to own a POI than those in pre-clinical years. (p = 0.009). However, no significant difference was observed in the frequency of use of POI, importance POI acquisition, advised or prompted to acquire POI, year advised or prompted to acquire POI, source of prompt and/or advice to acquired POI (p > 0.05). There was a statistically significant difference in financial difficulty (p = 0.001) and lack of access to reliable information about the quality of device instruments (p = 0.004) as a barrier to POI acquisition, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the sample

| Variables | Total (n = 485, 100%) | Acquired (n = 193, 39.8%) | Not acquired (n = 292,60.2%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (frequency) | % (frequency) | % (frequency) | ||

| Participant characteristics | ||||

| Age (± SD) | 21.66 (± 2.246) | 21.97 (± 2.389) | 21.45 (± 2.120) | 0.016 |

| Sex | 0.341 | |||

| Male | 55.5 (268) | 52.8 (102) | 57.2 (166) | |

| Female | 44.5 (215) | 47.2 (91) | 42.8 (124) | |

| Facilitators to POI acquisition | ||||

| Year of study | 0.009 | |||

| Non-clinical years | 53.9 (261) | 46.6 (90) | 58.8 (171) | |

| Clinical years | 46.1 (223) | 53.4 (103) | 41.2 (120) | |

| Frequency of use of POI in studies | 0.204 | |||

| Never | 17.2 (83) | 21.8 (42) | 14.1 (41) | |

| Rarely | 14.7 (71) | 14.0 (27) | 15.2 (44) | |

| Sometimes | 21.9 (106) | 22.3 (43) | 21.7 (63) | |

| Often | 21.1 (102) | 20.7 (40) | 21.4 (62) | |

| Very often | 25.1 (121) | 21.2 (41) | 27.6 (80) | |

| Importance of POI acquisition | 0.118 | |||

| Not important | 0.4 (2) | 1.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Slightly important | 0.6 (3) | 1.0 (2) | 0.3 (1) | |

| Moderately important | 3.3 (16) | 3.6 (7) | 3.1 (9) | |

| Important | 8.7 (42) | 5.7 (11) | 10.7 (31) | |

| Very important | 87.0 (420) | 88.5 (170) | 85.9 (250) | |

| Prompted/Advised on POI acquisition | 0.957 | |||

| Yes | 95.2 (461) | 95.3 (183) | 95.2 (278) | |

| No | 4.8 (23) | 4.7 (9) | 4.8 (14) | |

| Year prompt/advise was received | 0.125 | |||

| Non-clinical years | 97.2 (454) | 95.8 (183) | 98.2 (271) | |

| Clinical years | 2.8 (13) | 4.2 (8) | 1.8 (5) | |

| Source of prompt/advise | 0.112 | |||

| Lecturers | 77.0 (364) | 83.2 (159) | 72.7 (205) | |

| Head of department | 15.4 (73) | 11.0 (21) | 18.4 (52) | |

| Course mates | 1.1 (5) | 1.6 (3) | 0.7 (2) | |

| Senior course mates | 4.9 (23) | 3.1 (6) | 6.0 (17) | |

| Clinic/Hospital | 0.8 (4) | 0.5 (1) | 1.1 (3) | |

| Parent/Guardian | 0.4 (2) | 0.5 (1) | 0.4 (1) | |

| Others | 0.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.7 (2) | |

| Barriers to POI acquisition | ||||

| Financial difficulty (Yes) | 75.1 (364) | 67.4 (130) | 80.1 (234) | 0.001 |

| Lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality (Yes) | 8.0 (39) | 3.6 (7) | 11.0 (32) | 0.004 |

| Lack of access to purchasing options (Yes) | 14.4 (70) | 11.9 (23) | 16.2 (47) | 0.200 |

| Lack of knowledge on which instruments to buy (Yes) | 8.7 (42) | 8.3 (16) | 8.9 (26) | 0.814 |

| Not informed parents or guardians (Yes) | 9.5 (46) | 10.4 (20) | 8.9 (26) | 0.592 |

| Not finding it important to acquire POI (Yes) | 1.4 (7) | 1.6 (3) | 1.4 (4) | 0.868 |

| Squandered all money allocated for purchasing (Yes) | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.3 (1) | 0.416 |

| Other reasons (Yes) | 1.2 (6) | 0.5 (1) | 1.7 (5) | 0.244 |

%, percentage frequency; KNUST, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology; UCC, University of Cape coast; POI, Personal Ophthalmic Instrument; Chi-square analyses showing the distribution between the predictors and outcome at a significance of p ≤ 0.05. The outcome was dichotomized as acquired and not-acquired of POI. For clinical relevance and analytical purposes, having an ophthalmoscope has been considered to have a POI

Patterns of POI acquisition among optometry students in Ghana

Slightly more than one-third (39.8%) of the students had purchased a POI (see Table 1). The most commonly owned instruments were an ophthalmoscope (39.2%) and a retinoscope (18.5%), as shown in Fig. 1. The main barriers to POI acquisition were financial difficulties (63.3%), lack of access to purchase options (12.2%), uninformed parents or guardians (8.0%), lack of knowledge about which instrument to buy (7.3%), and lack of access to reliable information about instruments’ quality (6.8%), as shown in Fig. 2.

Factors associated with POI acquisition among optometry students in Ghana

In the bivariate logistic regression, age (COR: 1.11, CI: 1.02–1.21, p = 0.017) and being in clinical years (COR: 1.63, CI: 1.13–2.35, p = 0.009) were significantly associated with increased odds of acquiring personal ophthalmic instruments among students, whereas financial difficulty (COR: 0.51, CI: 0.34–0.78, p = 0.002), and lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality (COR: 0.31, CI: 0.13–0.71, p = 0.006) were significantly associated with decreased odds of acquiring personal ophthalmic instruments among students After statistical adjustment in the multiple logistic regression, students who faced financial difficulties (AOR: 0.45, CI: 0.29–0.71, p = 0.001) or lacked access to reliable information on instruments’ quality (AOR: 0.26, CI: 0.10–0.66, p = 0.005) were less likely to own a POI as seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with POI acquisition among optometry students in Ghana

| Variables | Bivariate regression | Multivariate regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR | 95% CI | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Participant characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 1.11 | 1.02–1.21 | 0.017 | 1.10 | 0.98–1.23 | 0.098 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | Ref | ||||||

| Female | 1.19 | 0.83–1.72 | 0.342 | ||||

| Facilitators to POI acquisition | |||||||

| Year of study | |||||||

| Non-clinical years | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Clinical years | 1.63 | 1.13–2.35 | 0.009 | 1.31 | 0.80–2.14 | 0.282 | |

| Frequency of use of POIs in studies | |||||||

| Never | Ref | ||||||

| Rarely | 0.60 | 0.32–1.14 | 0.119 | ||||

| Sometimes | 0.67 | 0.37–1.19 | 0.169 | ||||

| Often | 0.63 | 0.35–1.13 | 0.122 | ||||

| Very often | 0.50 | 0.28–0.89 | 0.018 | ||||

| Prompted/Advised on POI acquisition | |||||||

| No | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 1.02 | 0.43–2.42 | 0.957 | ||||

| Year prompt/advise was received | |||||||

| Non-clinical years | Ref | ||||||

| Clinical years | 2.37 | 0.76–7.36 | 0.136 | ||||

| Source of prompt/advise | |||||||

| Lecturers | Ref | ||||||

| Head of department | 0.52 | 0.30–0.90 | 0.019 | ||||

| Course mates | 1.93 | 0.32–11.71 | 0.473 | ||||

| Senior course mates | 0.46 | 0.18–1.18 | 0.106 | ||||

| Clinic/Hospital | 0.43 | 0.04–4.17 | 0.466 | ||||

| Parent/Guardian | 1.29 | 0.08–20.77 | 0.858 | ||||

| Others | 0.00 | 0 | 0.999 | ||||

| Barriers to POI acquisition | |||||||

| Financial difficulty, Yes | 0.51 | 0.34–0.78 | 0.002 | 0.45 | 0.29–0.71 | 0.001 | |

| Lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality (Yes) | 0.31 | 0.13–0.71 | 0.006 | 0.26 | 0.10–0.66 | 0.005 | |

| Lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality (Yes) | 0.71 | 0.41–1.21 | 0.201 | ||||

| Lack of knowledge on which instruments to buy (Yes) | 0.93 | 0.48–1.77 | 0.814 | ||||

| Not informed parents or guardians (Yes) | 1.18 | 0.64–2.19 | 0.592 | ||||

| Not finding it important to acquire POI (Yes) | 1.14 | 0.25–5.14 | 0.868 | ||||

| Squandered all money allocated for purchasing (Yes) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Other reasons (Yes) | 0.30 | 0.04–2.58 | 0.272 | ||||

| Received support/assistance from institution, (Yes) | 0.82 | 0.48–1.39 | 0.460 | ||||

COR, crude odds ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference; Bivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with significance set at p < 0.05. All variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis were included in the multiple logistic regression model with a significance level of p < 0.05

Discussion

This novel study investigated the acquisition of POIs among optometry students in Ghana. The study determined the proportion of students who had acquired their own POI and identified the factors influencing this acquisition, as well as the barriers students face. Slightly more than a third of the students owned POIs, with ophthalmoscopes being the most owned instrument. After adjusting for covariates, financial difficulties and lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality were significantly associated with lower likelihood of POI ownership. Financial difficulties emerged as the primary barrier to acquisition among students.

Optometry education in Ghana has witnessed remarkable growth in recent years, leading to a substantial increase in student enrollment [1–4]. This surge, concentrated in the country’s two training institutions, has placed considerable strain on existing infrastructure, faculty capacity, and educational resources. These challenges are further compounded by ongoing economic instability, which has driven unprecedented inflation in the cost of goods, including ophthalmic instruments. Consequently, optometric institutions face increasing difficulty in procuring clinical equipment in sufficient quantities to meet the growing student demand. Although access to instruments enhances hands-on training and fosters the development of technical competencies [15, 16], financial constraints and limited access to reliable information on the quality of POIs may hinder students’ ability to acquire their own instruments thereby restricting opportunities for independent practice and technical skill acquisition.

Although nearly 90% of optometry students valued POIs for their studies, only about one-third owned them, revealing a clear gap between their academic needs and available resources. The acquisition of clinical instruments extends beyond their use during clinical training to include their use in professional clinical practice and outreach activities [2–4]. While these findings underscore the importance of POI acquisition, they also reveal low ownership rates among students. The limited access to instruments hampers deliberate practice outside scheduled sessions, widening skill gaps between those who can and cannot afford equipment. This threatens competency-based education, as psychomotor skills like instrument handling require repetition to build confidence and speed both critical to effective clinical decision-making and patient care. Resource shortages along the education-to-practice continuum have been documented in other African countries [17, 18]. Qualitative studies from South Africa and Uganda, for example, highlight similarly under-resourced training environments and limited access to instruments as factors that students believe hinder their clinical preparedness [17, 18]. In contrast, some health-professional programmes elsewhere demonstrate higher rates of personal instrument ownership. For instance, over 95% of Serbian medical students reportedly owned a stethoscope by their fourth year, reflecting both the relatively low cost of the instrument and entrenched norms around individual ownership [19]. Collectively, the low acquisition rates of POI observed in this study may be ascribed to financial constraints (Fig. 2).

In this study, a key factor influencing POI acquisition among optometry students was the interplay between clinical training demands, financial constraints, and evolving technological preferences. Ophthalmoscopes were the most commonly owned POIs (Fig. 1), underscoring the emphasis placed on mastering direct ophthalmoscopy as a fundamental clinical skill. Successfully visualizing the fundus which includes complex anatomical structures such as the retina, optic disc, macula, and retinal vasculature is central to developing humanized diagnostic proficiency in optometric practice that requires a high degree of observational and interpretive skill [20, 21]. This clinical imperative likely motivates students to invest in ophthalmoscopes in order to meet practical expectations and skill benchmarks [22]. Recent studies indicate a growing preference among students for smartphone-based digital ophthalmoscopes, citing greater usability and improved diagnostic performance [23]. Although this digital shift has not yet been widely integrated into optometric training in Ghana, it signals a potential turning point. As digital tools become more affordable and accessible, traditional POIs such as the direct ophthalmoscope may see declining relevance particularly if cost-effective alternatives better serve the needs of financially constrained students. Another related example is the low ownership rate of retinoscopes in our study population. Despite their critical role in objective refractive assessments especially for children and non-cooperative patients, only 18.5% of students owned one (Fig. 1). Estay et al. estimate that students require at least 13.4 h of practice to achieve even 60% performance levels, with better outcomes associated with increased practice time [24]. Given that skill acquisition is highly dependent on access, the low rate of retinoscope ownership raises important concerns about whether students are receiving sufficient exposure to this essential technique. Reduced ownership may also reflect a growing reliance on automated objective refraction technologies, which are becoming more common in clinical settings across Ghana. Although the basic procedure of retinoscopy is relatively straightforward, mastering the skill requires the integration of procedural technique and declarative knowledge, making it both cognitively and technically demanding. Students frequently report challenges in learning retinoscopy further underscoring the need for hands-on practice [25]. Future research should explore how the increasing adoption of automated technologies is shaping the development of core optometric skills.

Financial barriers clearly play a decisive role in POI acquisition. Financial difficulty was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of owning a POI (see Table 2) and emerged as the most commonly reported barrier to purchasing instruments (Fig. 2). In Ghana, students often rely on limited parental stipends to meet both academic and living expenses, leaving little room for discretionary purchases like clinical tools. Future studies could explore the relationship between parental socioeconomic status and POI ownership to better understand the economic dimension of this challenge. However, in the absence of institutional or supplier support, many students are unable to acquire the tools necessary for independent practice and skill development. This shortfall has broader implications for the quality of clinical training and the professional readiness of graduates. Subscription-based models for equipment acquisition offer a viable alternative to the outright purchase of medical instruments [26]. Financial constraints are increasingly driving the adoption of such models in healthcare settings, and similar approaches could be adapted for educational contexts. A subscription-based model for POI acquisition would allow optometry students to lease essential ophthalmic instruments for a defined period such as the duration of their clinical training. This approach could significantly reduce the financial burden of upfront purchases while still enabling students to access personal equipment for practice and skill development.

Lack of access to reliable information on instrument quality was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of POI ownership among students (Table 2). This finding is unsurprising, given the absence of established purchasing pathways between POI manufacturers and optometric institutions in Ghana. The lack of formal supplier-buyer relationships and the perceived risk of acquiring substandard instruments may further discourage students from making independent purchases. To address this, targeted advocacy and the development of formal partnerships between POI manufacturers and educational institutions could help improve access and foster trust, ultimately increasing POI acquisition rates among students.

Consistent with this, financial difficulty emerged as the leading barrier to POI acquisition in our study population. The impact of educational costs is well documented across various educational settings, including undergraduate medical education [27–31], continuing professional development [32, 33], and graduate studies [34]. These studies, aligned with our findings and underscore the profound influence of financial burden on students’ ability to access essential learning tools and resources.

This study has several notable strengths. It represents the first documented investigation into the acquisition of POIs among optometry students in Ghana, an area with important implications for clinical training and workforce readiness. By identifying the key facilitators and barriers to POI acquisition, the study provides a valuable foundation for the development of policies and advocacy programs aimed at improving student access to ophthalmic instruments. Additionally, the likelihood of social desirability bias is reduced, as students are unlikely to report not owning a POI if they actually possess one. However, there are some limitations. The use of ophthalmoscope ownership as a proxy for POI acquisition, while practical, may overestimate overall acquisition rates, given the markedly low ownership of other essential instruments such as retinoscopes. Nevertheless, due to its relatively higher ownership rate, the ophthalmoscope remains the most statistically and pragmatically appropriate proxy available. Importantly, this study did not assess whether students who own POIs demonstrate superior clinical skills compared to their peers without them. Future research should explore this relationship within the same population to better understand the impact of POI ownership on clinical competency and to strengthen the case for broader access to clinical instruments in optometric education.

In light of the above findings, the authors make the following recommendations: Firstly, a standard ophthalmic diagnostic kit [] containing an ophthalmoscope, retinoscope, pen torch/transilluminator and PD ruler should be made available to all optometry students prior to the commencement of their clinical training. Secondly, optometry training institutions should establish formal partnerships with manufacturers of ophthalmic instruments to develop structured procurement plans and negotiate discounted prices for students. Thirdly, institutions, along with relevant stakeholders such as the Ministry of Health and the Ghana Optometric Association, should actively advocate for student-targeted equipment grants and financial assistance from non-governmental and non-profit organizations. Awareness campaigns should be directed at parents to highlight the critical role of POIs in the clinical education and professional development of optometry students.

Limitations

This study has few limitations: first, POI acquisition was defined as having ownership of ophthalmoscope. Though an ophthalmoscope is an important ophthalmic instrument, its use as a proxy in this study may be an overestimation of the overall POI acquisition rates considering the low ownership of other instruments. Again, the cross-sectional design of the study presents only a snapshot of POI acquisition rates at the particular period during data collection, and this may not reflect the changes and trends in acquisition over the years. Data collected at a point in time do not capture changes that may have occurred since then and thus, may not accurately reflect the current acquisition rates.

Conclusion

About 60% (60.1%) of optometry students did not have their own ophthalmic instruments, with the main reasons being financial difficulties and lack of access to reliable information about the quality of ophthalmic instruments. These findings are concerning given the key role of POIs in clinical training and practice. The study sheds light on the poor POI acquisition patterns among optometry students in Ghana and provides recommendations to optimize acquisition. Taken together, the findings have potential implications for improving optometric education in Ghana.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the authorities of the Schools of Optometry and Visual Science at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology and the University of Cape Coast for permission to conduct this study and the students for their willing participation. The authors also appreciate the services of Josephine Ampong (Department of Optometry and Visual Science at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology) and Dr. Jessica Eyeson (School Medical Sciences University of Cape Coast) for expertly proofreading the entire manuscripts for language clarity and typographical errors which undeniably have improved the readership of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval, COR: Crude odds ratio

- POIs

Personal ophthalmic instruments

- UCC

University of Cape Coast

- KNUST

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology

Author contributions

Contributions: Conceptualization: K.O.A.; drafted the original manuscript: I.O.D.J., K.O.A., B.O., and E.A.A.; Data collection: P.M., M.K.A., A.A., B.K.O. and S.B.O; data curation: I.O.D.J., K.O.A., E.A.A, A.K.A.A, formal analysis: I.O.D.J and E.A.A; data interpretation: I.O.D.J, K.O.A., E.A.A., A.K.A.A., P.M., M.K.A, A.A., B.K.O. and S.B.O.; review and editing: I.O.D.J, K.O.A., E.A.A., A.A. A.K.A.A., P.M., M.K.A, A.A., B.K.O., B.O, and S.B.O.; supervision: K.O.A. correspondence: K.O.A.

Funding

The authors received no funding support from government, private, and not-for-profit organization.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana (CHRPE/AP/407/23) after formalized institutional approval from authorities of the Departments of Optometry and Visual Sciences at KNUST and UCC. The study obtained written informed consent from all student participants and adhered to the Tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ovenseri-Ogbomo G, Kio FE, Morny EK, et al. Two decades of optometric education in ghana: update and recent developments. Afr Vis Eye Health. 2011;70:136–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobia-Acquah E, Owusu E, Akuffo KO, Koomson NY, Pascal TM. Career aspirations and factors influencing career choices of optometry students in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0233862. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233862. Published 2020 May 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boadi-Kusi SB, Kyei S, Okyere VB, Abu SL. Factors influencing the decision of Ghanaian optometry students to practice in rural areas after graduation. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):188. 10.1186/s12909-018-1302-3. Published 2018 Aug 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boadi-Kusi SB, Kyei S, Mashige KP, Abu EK, Antwi-Boasiako D, Carl Halladay A. Demographic characteristics of Ghanaian optometry students and factors influencing their career choice and institution of learning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(1):33–44. 10.1007/s10459-014-9505-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boadi-Kusi SB, Ntodie M, Mashige KP, Owusu-Ansah A, Antwi Osei K. A cross-sectional survey of optometrists and optometric practices in Ghana. Clin Exp Optom. 2015;98(5):473–7. 10.1111/cxo.12291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akuffo KO, Osei Duah Junior I, Acquah EA, et al. Low vision practice and service provision among optometrists in ghana: a nationwide survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2025;32(1):1–8. 10.1080/09286586.2024.2317816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Blindness and vision impairment. 10 August 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment

- 8.GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e130–43. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30425-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdulhussein D, Abdul Hussein M. WHO vision 2020: have we done it?? Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2023;30(4):331–9. 10.1080/09286586.2022.2127784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JH, Ramke J, Jan C, et al. Advancing the sustainable development goals through improving eye health: a scoping review. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6(3):e270–80. 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00351-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acheampong HO, Kumah DB, Addo EK, et al. Practice patterns in the management of amblyopia among optometrists in Ghana. Strabismus. 2022;30(1):18–28. 10.1080/09273972.2021.2022715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akuffo KO, Agyei-Manu E, Kumah DB, et al. Job satisfaction and its associated factors among optometrists in ghana: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):12. 10.1186/s12955-020-01650-3. Published 2021 Jan 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijendran S, Kamath YS, Alok Y, Kuzhuppilly NIR. Determination of refractive error using direct ophthalmoscopy in children. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:989–96. 10.2147/OPTH.S453207. Published 2024 Apr 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyeremeh S, Mashige KP. Availability of low vision services and barriers to their provision and uptake in ghana: practitioners’ perspectives. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21(2):896–903. 10.4314/ahs.v21i2.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warner DL, Brown EC, Shadle SE. Laboratory instrumentation: an exploration of the impact of instrumentation on student learning. J Chem Educ. 2016;93:1223–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilmour-White JA, Picton A, Blaikie A et al. Does access to a portable ophthalmoscope improve skill acquisition in direct ophthalmoscopy? A method comparison study in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):201. Published 2019 Jun 13. 10.1186/s12909-019-1644-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Zulu NL, Van Staden D. Experiences and perceptions of South African optometry students toward public eye care services. Afr Vis Eye Health. 2023;82(1):a726. 10.4102/aveh.v82i1.726 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mucunguzi B, Guti W, Tumwine M, et al. Ugandan optometry students’ experiences of their clinical training: a qualitative study. BMC Res Notes. 2024;17(1):296. 10.1186/s13104-024-06961-y. Published 2024 Oct 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gazibara T, Radovanovic S, Maric G, Rancic B, Kisic-Tepavcevic D, Pekmezovic T. Stethoscope hygiene: practice and attitude of medical students. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24(6):509–14. 10.1159/000434753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohler J, Tran TM, Sun S, Montezuma SR. Teaching smartphone funduscopy with 20 diopter lens in undergraduate medical education. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:2013–23. 10.2147/OPTH.S266123. Published 2021 May 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doria C. The ophthalmoscope and the physician: technical innovations and professionalization of medicine. J Mater Cult. 2023;28:264–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly LP, Garza PS, Bruce BB, Graubart EB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Teaching ophthalmoscopy to medical students (the totems study). Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(5):1056–e106110. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu AR, Fouzdar-Jain S, Suh DW. Comparison study of funduscopic examination using a smartphone-based digital ophthalmoscope and the direct ophthalmoscope. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2018;55(3):201–6. 10.3928/01913913-20180220-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estay AM, Plaza-Rosales I, Torres HR, Cerfogli FI. Training in retinoscopy: learning curves using a standardized method. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):874. 10.1186/s12909-023-04750-y. Published 2023 Nov 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollis J, Allen PM, Heywood J. Learning retinoscopy: a journey through problem space. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2022;42(5):940–7. 10.1111/opo.13007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olivia Tonks. Overcoming barriers to subscription models for medical equipment in healthcare. IDR Medical. 2024. https://info.idrmedical.com/blog/overcoming-barriers-to-subscription-models-for-medical-equipment-in-healthcare?

- 27.Ball M, Lam L, Tigue M, Herzberg S, Finck L. The burden of unexpected costs in medical school. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(12):e0312401. 10.1371/journal.pone.0312401. Published 2024 Dec 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foo J, Rivers G, Allen L, Ilic D, Maloney S, Hay M. The economic costs of selecting medical students: an Australian case study. Med Educ. 2020;54(7):643–51. 10.1111/medu.14145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersdorf RG. Financing medical education. Acad Med. 1991;66(2):61–5. 10.1097/00001888-199102000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DaRosa DA, Skeff K, Friedland JA, et al. Barriers to effective teaching. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):453–9. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820defbe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindor KD, Pawlina W, Porter BL, et al. Commentary: improving medical education during financially challenging times. Acad Med. 2010;85(8):1266–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e5a75c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vought-O’Sullivan V, Meehan NK, Havice PA, Pruitt RH. Continuing education: a national imperative for school nursing practice. J Sch Nurs. 2006;22(1):2–8. 10.1177/10598405060220010201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos MC. Nurses’ barriers to learning: an integrative review. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2012;28(4):182–5. 10.1097/NND.0b013e31825dfb60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd LD, Bailey A. Dental hygienists’ perceptions of barriers to graduate education. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(8):1030–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornwell K. Comparing equipment for optometry students: which diagnostic set is best? Eyes on eyecare. 2020. https://eyesoneyecare.com/resources/comparison-best-diagnostic-sets-optometry-students/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.