Abstract

3D-printing has emerged as a leading technology for fabricating personalized scaffolds for bone regeneration. Among the 3D-printing technologies, vat photopolymerization (VP) stands out for its high precision and versatility. It enables the creation of complex, patient-specific scaffolds with advanced pore architectures that enhance mechanical stability and promote cell growth, key factors for effective bone regeneration. This review provides an overview of the advances made in vat photopolymerization printing of calcium phosphates, covering both the fabrication of full ceramic bodies and polymer-calcium phosphate composites. The review examines key aspects of the fabrication process, including slurry composition, architectural design, and printing accuracy, highlighting their impact on the mechanical and biological performance of 3D-printed scaffolds. The need to tailor porosity, pore size, and geometric design to achieve both mechanical integrity and biological functionality is emphasized by a review of data published in the recent literature. This review demonstrates that advanced geometries like Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces and nature-inspired designs, achievable with exceptional precision by this technology, enhance mechanical and osteogenic performance. In summary, VP's versatility, driven by the diversity of material options, consolidation methods, and precision opens new horizons for scaffold-based bone regeneration.

Keywords: Additive manufacturing, 3D printing, Vat polymerization, Hydroxyapatite, Scaffold, Bone regeneration

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Vat photopolymerization excels in the fabrication of precise and personalized 3D calcium phosphate-based scaffolds.

-

•

Vat photopolymerization supports fabricating both full ceramic and composite calcium phosphate scaffolds.

-

•

The advanced pore designs enabled by Vat photopolymerization promote efficient bone regeneration.

-

•

Vat Photopolymerization enables the fabrication of complex calcium phosphate scaffolds with tailored mechanical properties.

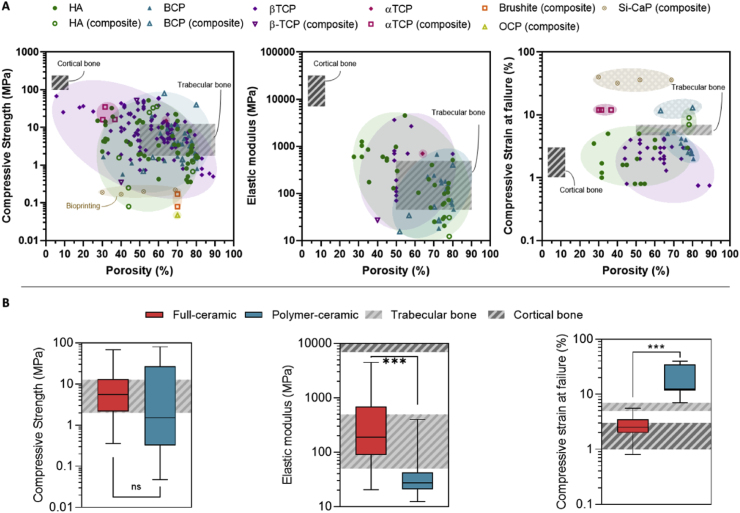

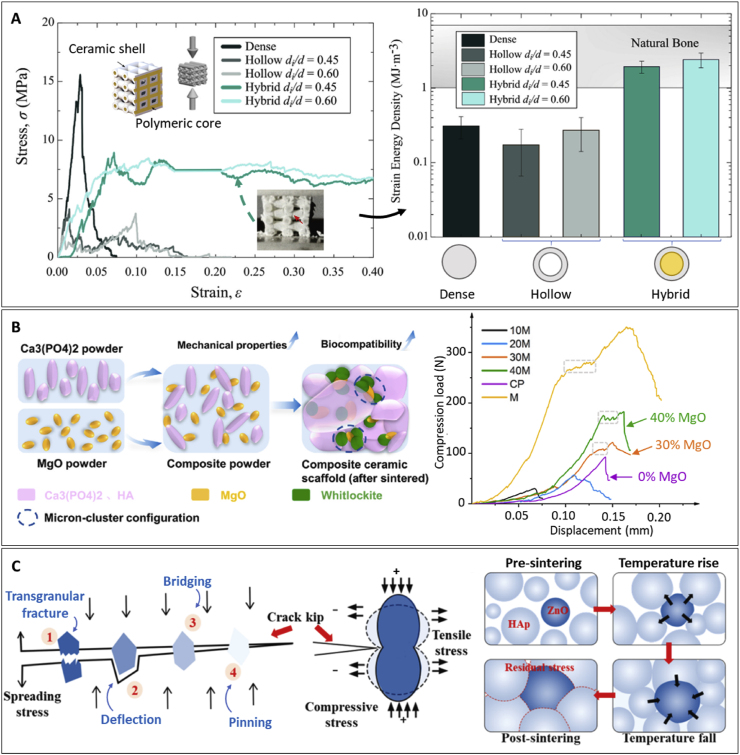

Structured abstractPurpose: 3D printing has steadily garnered increasing popularity for fabricating bone scaffolds. In the last years, vat photopolymerization has emerged as a groundbreaking 3D printing technique for calcium phosphate scaffolds, owing to its high versatility, exceptional printing precision, and material options. This review aims to provide a comprehensive and novel analysis of the advances in vat photopolymerization of calcium phosphate-based scaffolds for bone regeneration, highlighting innovative approaches and strategies.Procedure: This review was conducted through an advanced bibliographic search using Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed. The search focused on a combination of the following areas of interest: vat photopolymerization techniques, the inclusion of calcium phosphate bioceramics, and bone related applications. The selected studies were meticulously analyzed for key aspects such as resin formulations, manufacturing parameters, rheological properties, post-printing processes, mechanical properties, and, finally, biological performances. A particular emphasis was placed on comparing the mechanical performance of the scaffolds based on their composition and architecture, offering a unique categorization and comparative analysis.Results: This study offers a deep insight of the latest studies, by providing details with a novel approach to understand the field's progress. Two primary fabrication routes were determined, each leading to distinct structural and functional properties. Namely, over 75 % of the studies focused on creating full ceramic bodies, while the remaining 25 % explored composite structures. Additionally, this study discusses the latest strategies performed by researches to enhance both the mechanical and biological performance of bone scaffolds. These include advanced innovative scaffold compositions, post-processing techniques, and architectural designs.

1. Introduction

Bone is a highly hierarchical and metabolically active tissue that provides support and protection to vital organs, stores essential ions, and plays a critical role in maintaining bone homeostasis. Despite its regenerative capacity, bone healing can be impaired by systemic factors like age, diabetes or malnutrition, and local factors like poor blood supply, infection, or the presence of large defects caused by trauma or tumor resection. In such scenarios, bone grafting is a common procedure to restore bone function and structure. Worldwide, an estimated 2.2 million bone grafting procedures are performed annually, and are expected to grow by 13 % each year [1]. While autologous bone grafts, so-called autografts, remain the gold standard, the use of synthetic bone grafts for orthopedic interventions strongly surged from 11.8 % in 2008 to 23.9 % in 2018 [2]. In the last ten years, the demand for synthetic-based biomaterials increased by 134 % compared to autografts, which varied by 74 %, and allografts, whose demand decreased by 14 % [2].

Bone tissue engineering addresses large bone defects by integrating biomaterials, cells, and signaling molecules with scaffolds. These temporary structures support bone remodeling while minimizing complications [3]. They enable defect filling with personalized shapes, providing mechanical support, and guiding new tissue growth [4]. Designed to mimic the extracellular matrix, scaffolds facilitate cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and the exchange of nutrients and waste while gradually degrading and being replaced by newly formed bone [5,6].

Synthetic bone grafts have been extensively developed and have achieved clinical relevance, particularly calcium phosphate (CaP) bioceramics. CaPs closely resemble the mineral phase of natural bone in terms of composition and have been shown to be biocompatible, bioactive and osteoconductive. Moreover, in certain configurations, they have demonstrated osteoinductive properties, promoting the differentiation of cells into the bone lineage [7]. One of the main motivations fostering CaP research is the key role of Ca mineralization in endochondral ossification during early fetal development, leading to bone tissue formation. On the other hand, the degradation of certain synthetic CaP-based biomaterials can be integrated into the physiological process of bone remodeling. Finally, the presence of calcium (Ca2+) and phosphorous (Pi), at specific concentrations, can enhance the proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells [8]. Despite their success, their application is largely limited to non-load-bearing scenarios due to their inherent brittleness. To address these structural limitations, calcium phosphates have been combined with biocompatible polymers, providing enhanced elasticity and toughness [9].

Despite the close resemblance to the natural bone mineral phase, CaP geometrical design has been a limiting factor in their overall structural integrity and implementation. Often produced in standardized shapes or blocks, CaPs pre-formed designs fail to adapt to patient-specific bone defects, requiring manual adjustments and tailoring by surgeons, which can further compromise material properties and the clinical outcome. Traditional methods such as particulate leaching [10,11], emulsions, freeze-drying, foaming [12], or the use of templates enable the fabrication of porous scaffolds with high interconnectivity and porosity, similar to bone natural structure [13]. However, while offering simplicity and versatility, these techniques yield poor reproducibility and low patient-specificity [14]. The emergence of cutting edge technologies such as additive manufacturing (AM) has enabled the creation of complex customized scaffolds, with interconnected macroporous architectures that mimic the structure and hierarchy of natural bone [4]. Additive manufacturing (AM), and more precisely 3D printing offers a promising approach to personalized medicine. It allows fabricating patient-specific scaffolds with complex geometries, with high reproducibility and accuracy, not only of the external shape but also of the internal architecture [6].

The ASTM F2792-12a standard identifies seven distinct 3D printing technologies: binder jetting, directed energy deposition, material extrusion, material jetting, powder bed fusion, sheet lamination, and vat photopolymerization. Regarding ceramic 3D printing, these seven technologies can be categorized into four groups: i) Powder bed-based AM, where a roller or scraper system spreads a layer of powder or slurry onto the printing substrate, and a device selectively binds the desired regions; ii) Dispensing-based AM, which uses a dispensing device controlled by a 3D positioning system to progressively deposit material layer by layer, forming a 3D structure; iii) Lamination-based AM, where sheets of material are layered on the printing area, and a cutting device defines the regions of interest; and iv) Vat photopolymerization AM, based on the polymerization of liquid polymer precursors or suspensions with the incorporation of colloidal ceramic particles in the case of ceramic printing [15]. Each of these techniques has its advantages and limitations for the printing of calcium phosphate-based scaffolds, in terms of resolution and material selection.

Dispensing-based AM techniques, such as fused deposition modelling (FDM) and direct ink writing (DIW) are very versatile in terms of materials, allowing to print different polymers loaded with calcium phosphate particles, which can be subsequently sintered or not, resulting in full ceramic or composite scaffolds. Ceramic-FDM works by depositing a composite filament from a nozzle by reducing its viscosity through melting. It has been widely adopted with CaPs to create suitable and robust composites by incorporating biocompatible and bioresorbable thermoplastic polymers such as polycaprolactone (PCL) [16,17] or polylactic acid (PLA) [[18], [19], [20]] without requiring solvents. This approach has enabled the fabrication of dimensionally accurate and mechanically enhanced scaffolds [17]. However, FDM has limitations in terms of ceramic loading, typically achieving optimum loadings ranging from 5 to 15 wt%, with some exceptions incorporating up to 30 to 50 wt% [20]. These values are significantly lower than the mineral content of natural bone, which is around 60–70 wt% [21]. In contrast, DIW, which entails the extrusion of a paste, operates at low temperatures (e.g., room temperature), offering new possibilities for bone scaffold manufacturing [9]. For instance, it can be made compatible with cell printing, which is not possible when using FDM [22]. Additionally, DIW supports higher ceramic loading, enabling the extrusion of highly loaded ceramic pastes that, after post-processing, result in full-ceramic 3D printed porous bioceramic scaffolds [[23], [24], [25]]. To overcome the brittleness of full-ceramic scaffolds, biocompatible polymers such as poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) [26], and PCL [9,27] have also been incorporated into the inks for DIW, resulting in composite scaffolds with enhanced toughness. This approach, compared to FDM, allows increasing the ceramic content, reaching up to 70 wt% and showing improved mechanical and biological properties. However, material extrusion AM requires ceramic suspensions with appropriate viscosity and shear-thinning behavior [28]. To ensure smooth and steady extrusion, the nozzle size is generally large in order to meet a feasible extruding force, ranging from hundreds to thousands of newtons for high-load suspensions. This creates a trade-off between printing accuracy and printability [29]. As a result, printing resolutions are typically above 100 μm [30], limiting the possibility of creating complex structures with high precision that could mimic the architecture of natural bone, even when support structures are used [31].

Higher resolution AM methods such as powder bed-based techniques are also commonly used for scaffold fabrication. Powder bed fusion (PBF) uses a high-energy laser or electron beam to selectively melt (Selective Laser Melting; SLM) or sinter (Selective Laser Sintering; SLS) the spread powder, bonding the particles into a dense structure. In contrast, Binder Jetting (BJ) uses a dispensing nozzle to selectively deposit a liquid binder onto the powder, bonding the particles together in specific areas. These AM techniques allow the production of complex geometries and architectures with the great advantage of not needing support structures in the printing process. However, each technique has its trade-offs when fabricating CaP scaffolds. SLS-based strategies pose a number of challenges in both processing and post-processing. CaPs exhibit very high melting temperatures, making them hard to process, as they require high-power lasers capable of heating ceramic powders to densify particles into stacked 2D layers [32]. While PBF provides high mechanical properties, high precision, and no need for binders, the melting/sintering process may cause phase transformations, temperature gradients and internal residual stresses and cracks [33]. One possible alternative is the incorporation of lower-melting-point thermoplastic polymers such as PCL, poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), polyether ether ketone (PEEK), or polyamide (PA) to obtain composite structures [34]. However, achieving high ceramic loadings is challenging, as it requires increased laser energy, creating a compromise between ceramic loading, printability, and energy consumption. As a result, composite scaffolds fabricated with PBF normally contain 5-50 wt% ceramic content [34]. In opposition, BJ operates at low processing temperature, resulting in lower probability of cracks and no residual stresses. This technique also enables higher ceramic loadings, reaching >70 wt% [35]. Nonetheless, BJ-printed scaffolds experience lower mechanical strength, and lower resolution due to potential binder infiltration, affecting the scaffold's final porosity. Overall, powder bed-based AM techniques are promising approaches for creating complex scaffolds with high precision, achieving layer thicknesses of about 30–200 μm for SLS/SLM and 50–200 μm for BJ [32,36]. However, they are often limited in terms of resulting composition, as a sintering process is needed to remove the binder and fuse the ceramic particles together. Additionally, the large size and high cost of these machines are limiting factors when adapting their integration into clinical or hospital settings.

In this context, Vat Photopolymerization (VP) appears as an innovative technique that has gained increasing attention in medical applications, especially due to its high precision, achieving resolutions of a few tens of micrometers. Compared to other AM techniques, VP offers significant advantages in addressing some of the previously mentioned challenges. Specifically, calcium phosphate particles are mixed into liquid resins to form ceramic suspensions, which are processed in vats where light selectively solidifies layers at low temperatures. Unlike FDM, which requires the material to pass through heated nozzles, VP enables the use of resins heavily loaded with calcium phosphate particles (10–70 wt%) [[37], [38], [39]]. While VP does present challenges related to light-material interactions, it offers greater design capability than material extrusion techniques, enabling the fabrication of complex geometries similar to the architecture of natural bone. Additionally, although challenging, the rheological demands are less stringent than in material extrusion techniques. Furthermore, compared to SLS/SLM, VP does not operate with highly powered lasers and does not require high temperatures, making this technique a more affordable variant that could potentially be integrated into clinical and hospital settings. The risk of defects such as cracks, phase transformations, and dimensional distortions during printing is reduced. However, VP requires extensive post-processing, including cleaning, which can be difficult with tight and low-porous designs, often leading to pore occlusions and residual uncured resin inside the structure. Moreover, common resins often contain toxic components, requiring a binder removal step followed by sintering, resulting in mechanically weak full-ceramic parts. Recent advances in the formulation of biocompatible resins have expanded the potential for obtaining composite structures, a promising approach to overcome post-processing limitations, and enhance mechanical and biological performances.

This review aims to summarize the progress and future perspectives of VP manufacturing of calcium phosphate-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, including: (1) the principles of CaP VP printing and the slurry requirements; (2) the composition and processing strategies of VP-printed CaP-scaffolds; (3) the effect of the material and processing routes on the mechanical and biological response; and (4) the strategies that are being explored to improve the mechanical and biological performance of the scaffolds. Although ceramic VP has been used with various bioceramics and bioactive glasses, this study focuses specifically on calcium phosphates as key materials in bone grafting due to their close resemblance to the mineral phase of bone. Furthermore, the growing interest toward incorporating these materials into advanced VP approaches cannot be overlooked, as it holds significant relevance for an increasingly engaged research community (Fig. S1 in Supplementary information). This review was conducted through a bibliographic search of scientific articles using three databases, Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed. Other sources of information such as patents or clinical study reports may contain valuable but more fragmented and less accessible information, and were considered outside the scope of this study. Similarly, this review is specifically focused on calcium phosphate for bone regeneration and does not address other types of ceramics that may serve different applications with distinct structural and functional requirements. The keywords and search strategy are detailed in the Supplementary information.

2. Vat photopolymerization (VP) techniques

VP manufacturing involves selectively curing a photosensitive material, usually polymers, using a light source, typically in the ultraviolet range. During this process, a tank containing the photosensitive resin is exposed to light, forming the layers of the final geometry which is attached to a building platform. This exposure can either be from the bottom up through a transparent film into the tank containing the resin (bottom-up approach), or from the top down to the tank containing the resin (top-down approach). The light travels from the light source and penetrates the photosensitive resin, colliding with the building platform. The material in between solidifies and attaches to the moving building platform, also known as the build plate, becoming the first layer. The build plate retraces back and the following layers solidify and adhere to one another progressively, creating the final piece layer by layer.

VP techniques can be categorized depending on the employed light sources during photocuring. Basically, laser-based (Fig. 1A) and projection-based sources can be used (Fig. 1B). Laser-based techniques create a linear pattern for each layer. Common examples include Stereolithography (SLA), which uses a laser beam to cure the resin layer by layer linearly (either bottom-up or top-down), and Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP), which utilizes femtosecond lasers to cure the resin at a precise focal point. Projection-based techniques irradiate an entire pattern directly onto the resin, curing it all at once. Typical examples include Digital Light Processing (DLP), which uses a digital micromirror device (DMD) to project the image; Continuous Liquid Interface Production (CLIP), which creates a dead zone hampering the curing of the resin (enabling continuous production); and LCD-DLP 3D printing, also known as Masked Stereolithography (mSLA), which is similar to DLP but uses an LCD panel to mask the UV light source [40].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of Vat Photopolymerization techniques, categorized as: (A) laser-based techniques, such as Stereolithography (SLA) and Two-photon Polymerization (2PP); and (B) projection-based techniques, such as Digital Light Processing (DLP), Liquid Crystal Display-based masking projection (LCD-DLP), or masked stereolithography apparatus (mSLA), and Continuous Liquid Interface Production (CLIP).

The most popular techniques for VP printing of calcium phosphate-based materials are DLP, accounting for over 75 % of the reviewed publications, and SLA, used in around 25 % of the publications.

2.1. Stereolithography (SLA)

SLA is considered one of the earliest VP techniques, first developed in 1986 by Charles Hull [29]. SLA involves using a laser that scans a photosensitive liquid resin leaving behind a solidified line of crosslinked polymer. The photosensitive resin is placed in a vat and the laser scans linearly, selectively irradiating specific areas which become a solidified layer. This process is repeated layer by layer, solidifying and adhering consecutive layers to each other, and resulting in the final print. Typical commercial printers use tens of microwatts lasers (such as a 30 mW [41]), and can be set to hundreds of microwatts (100 mW [42]), and even higher, up to 300 W [43] when employing custom-made SLA printers. The laser beam penetrates solidifying tens of μm high in the z-axis linear patterns. In the x-y plane, the resolution depends on the laser beam-spot size, as represented in Fig. 1A, which is easily adapted to create complex and detailed geometries. However, SLA has some limitations in terms of printing time, as the laser scan results in a slow printing speed.

2.2. Digital Light Processing (DLP)

DLP is a projection-based technique which involves projecting a pattern of light at once onto a photosensitive liquid resin using LED arrays projected towards a Digital Micromirror Device (DMD) or a liquid crystal display (LCD). First, the build plate is immersed into a ceramic-loaded photosensitive resin (or slurry). The movable build plate descends beneath the liquid surface leaving a programmed gap (layer height) between the build plate and the bottom of the transparent vat. Then, the light source, typically a lamp or LED array, irradiates onto the DMD or the LCD, which directs it to the bottom of the tank in the designed pattern. In the case of DMD, multiple micrometric mirrors selectively move to either reflect light towards the vat, or hinder the exposition at that specific location. This way, each micromirror acts as a pixel that solidifies a quantified volume or voxel. Once the slurry solidifies, the platform separates from the bottom of the tank enabling the slurry to flow back underneath. Then, the build plate with the first layer attached to its surface descends again leaving the latter layer height between the hardened layer and the bottom of the tank. The process is repeated until the scaffold is formed layer by layer [44]. Since it prints the entire layer simultaneously, DLP is faster than SLA. On the other hand, LCD screens are controlled by a computer, selectively blocking the light and exposing only the transmission areas that will form the layer. One key advantage of this technology compared to DMD is its relatively more affordable cost, making it the most common commercially available option. However, LCD has some limitations in terms of printing size, which is restricted by the LCD panel, and less lifespan when compared to a projector with DMD [29].

The printing resolution in the z-axis, ranging from 20 to 100 μm, is associated with the layer height and is highly dependent on the stepper motor or linear actuators controlling Z-axis platforms. The most typical layer heights are 25–50 μm, although lower values, down to 20 μm, have been achieved [45,46]. The resolution in the x-y axes, on the other hand, can significantly vary between DMD or LCD due to their differences in their light modulation mechanics and optics. Typically, the resolution is limited to the pixel size that the projection system creates on the resin, resulting in a solidified voxel as the minimum printing volume, represented in (Fig. 1B). While DMD x-y resolutions typically range from 50 to 100 μm, LCD systems can achieve 50–75 μm; however, DMDs provide higher pixel size consistency and uniformity compared to LCD systems where light intensity can vary across the build area and reduce precision.

3. Photocurable resins for Vat photopolymerization of calcium phosphate-based materials

VP of calcium phosphate-based scaffolds has garnered much attention in the field of bone regeneration. Calcium phosphate-loaded photosensitive resins consist of a colloidal suspension of calcium phosphate particles in a liquid photosensitive polymeric resin. Under irradiation, a continuous cross-linked polymeric network containing the calcium phosphate particles is obtained [3,47,48]. The polymeric resin contains polymeric monomers/oligomers, light-sensitive initiator molecules (photoinitiators), and small concentrations of other additives. The selection of the appropriate components and their concentrations plays a crucial role in determining the polymerization resolution, printing time, and accuracy, thereby tailoring the functional properties of the 3D printed structure [30]. These components are typically mixed before printing, using either a planetary ball milling or centrifugal mixers. The elements in the slurry must be carefully selected to ensure high precision, and will be described in the following sections.

3.1. Photocurable polymeric resins

3.1.1. Calcium phosphate-loaded photocurable resins

The central components of the resin are the photocurable prepolymers (monomers or oligomers), which act as the building blocks of the final solidified part. These molecules contain crosslinking functional groups that interact with each other, forming a network. The most commonly used prepolymers are synthetic acrylated prepolymers like poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) [37,[49], [50], [51], [52], [53]], 1,6-hexanediol diacrylate (HDDA) [[54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]], trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TPMTA) [55,[60], [61], [62], [63], [64]], poly(trimethylene carbonate)-methacrylate (PTMC-MA) [[65], [66], [67], [68], [69]], among others. These synthetic polymers provide adequate, mechanically robust structures and are non-cytotoxic, although they are inert in terms of cell-material interactions and often face poor cell adhesion. Natural polymers such as gelatin, collagen, silk-fibroin, or alginate in their acrylated forms (methacrylated gelatin (GelMA) [[70], [71], [72], [73]], methacrylated collagen (ColMA), methacrylated silk-fibroin (SilMA) [74], methacrylated alginate (AlgMA) [75]) have been more recently explored in the field of VP printing for medical applications. Bone-derived decellularized extracellular matrix methacrylate (bdECM-MA), rich in collagen-, glycosaminoglycans- (GAGs), and other bone-specific ECM proteins, is another promising material recently used in VP bioprinting [76]. These materials closely resemble the polymeric composition of natural bone, potentially exhibiting better specificity in cell-material interactions. Another prepolymer that has been recently proposed for the preparation of CaP-containing resins is CSMA-2 ((3R, 3aR, 6S, 6aR)-hexahydrofuro [3,2-b] furan-3,6-diyl)bis(oxy)) bis(ethane-2,1-diyl))bis(oxy))bis(carbonyl))bis(azan ediyl))bis(3,3,5 trimethylcyclohexane-5,1-diyl))bis (azanediyl))bis(carbonyl))bis(oxy))bis(ethane-2,1-diyl) bis(2-methylacrylate)). This novel synthetic bio-based prepolymer has shown excellent printability, good mechanical properties and biocompatibility in vitro and in vivo [39,77], with great osteogenic and angiogenic potential [78].

3.1.2. Photoinitiators

Under light irradiation, the prepolymers start to crosslink to form the solidified network due to the action of photoinitiators. These are molecules that create reactive species in the form of free radicals or cations/anions when exposed to radiation, initiating the polymerization reaction by interacting with the monomers/oligomers. Thereby, the crosslinking mechanisms are categorized as either radical polymerization or cationic polymerization [79]. Some of the most used monomers/oligomers and photoinitiators are displayed in Table 1, detailing their chemical composition and optimal operating wavelength.

Table 1.

Common monomers/oligomers and initiator molecules used in the formulation of photocurable resins. Typical (meth)acrylated monomers/oligomers are selected for their double bonds, which react with each other to form covalent bonds, thus enabling chemical crosslinking (TMPTA molecule figure taken from Ref. [69], and CSMA-2 from Ref. [39]). The initiation and propagation of this reaction are driven by photoinitiator molecules, which convert photolytic energy into reactive species that initiate the polymerization process (photoinitiator molecule figures taken from Ref. [79]).

| Monomer/Oligomer | Molecule | Initiator | Molecule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) |  |

Diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide (TPO) |  |

| λpeak 380 nm | |||

| 1,6-hexanediol diacrylate (HDDA) |  |

Ethyl phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphinate (TPO-L) |  |

| λpeak 379 nm | |||

| Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) |  |

Lithium phenyl-2,4,6 trimethyl-benzoyl phosphinate (LAP) |  |

| λpeak 450 nm | |||

| Poly(trimethylene carbonate)-methacrylate (PTMC-MA) |  |

Phenyl bis (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide (BAPO) |  |

| λpeak 370 nm | |||

| CSMA-2 | |||

The most commonly used mechanism in VP printing is radical photopolymerization. The mechanism is based in the reaction of monomer/oligomer functional groups with free radicals, forming covalent bonds between prepolymers and resulting in crosslinked chains [80]. The process follows three steps: (i) radical generation: under light irradiation photoinitiator molecules react with photons of a specific energy (wavelength), and are responsible of converting this energy into reactive species; (ii) initiation: these species react with prepolymer molecules initiating the polymer chain reaction; and (iii) propagation: polymerization process [30,79,81]. Free radical initiators themselves can be categorized as Norrish-type I (also called α-cleavage), and Norrish-type II. Type I free radical initiators are the most used photoinitiators in VP printing with calcium phosphates. They undergo photo-cleavage resulting in two radical species, both being capable of initiating the polymerization. The wavelength and intensity of light needed to trigger cleavage vary based on the chemical structures of the photoinitiators [79]. Common type I initiators include phosphine oxide-containing molecules, such as diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethyl benzoyl)phosphine oxide (TPO; λpeak ∼ 380 nm), ethyl phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphinate (TPO-L; λpeak ∼ 379 nm), and phenylbis(2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoyl)-phosphineoxide (BAPO; λpeak ∼ 370 nm) (Table 2). In fact, TPO and BAPO, and their commercial branding names (Irgacure®, Omnirad®) are widely used because of their efficiency. Other type I initiators used in VP printing include lithium phenyl-2,4,6 trimethyl-benzoyl phosphinate (LAP; λpeak ∼ 405 nm) [82]. Free-radical type II initiators generate radicals in the presence of a co-initiator, typically hydrogen donating compounds, such as amines, thiols or alcohols. The most commonly used type II initiators are camphorquinones (CQ, λpeak ∼ 480 nm) and thioxanthones [79], such as 2-isopropyl-9h-thioxanthen- 9-one (ITX) [37]. However, compared to type I initiators, type II initiators such as CQ have low photoreactivity, often addressed with the addition of tertiary amines as electron/proton donors or reducing agents [83].

Table 2.

Resin formulations and rheological properties, printing parameters and post-printing processes for vat photopolymerization printing of calcium phosphate full-ceramic scaffolds (D: debinding; CD: chemical debinding; S: sintering; d: dose, I: intensity, P: power, LH: layer height, λ: curing wavelength).

| CaP | Loading | Slurry composition | VP printing | Slurry's viscosity | Post-process | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | _ | Commercial slurry: LithaBone HA 480E (Lithoz GmbH, Vienna, Austria) | DLP (Cerafab7500) | _ | D: up to 800 °C, or CD: LithaSol 30 | [123,124,126,130] |

| LH: 25 μm | S: 1275–1300 °C for 2 h | |||||

| λ: 460 nm | ||||||

| d: 150 mJ/cm2 | ||||||

| 48 wt% | Commercial slurry: HAPM100T01 (CERHUM, Belgium) | DLP (Propmaker V6000) | _ | S: 1170 °C, 1270 °C for 5–90 h | [128,129] | |

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| λ: 365 nm | ||||||

| 45 wt% | Commercial slurry: Shanghai Guangyi Chemical Co., Ltd., China | DLP | <12 Pa s | D: 500 °C for 4 h | [101] | |

| Dispersant: SPA | LH: 100 μm | S: 1400 °C for 1.5 h | ||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| I: 11 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| Protected | SLA (3D Ceram) | _ | D: 240-460-800 °C | [99,131] | ||

| S: 1050 °C | ||||||

| 40 vol% | Monomer: PEGDA (Mn = 250) | DLP (custom) | 0.18 Pa s | S: at 1300 °C for 2 h | [51] | |

| Initiator: 2 wt% PPO (BAPO) | LH: 100 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 3 wt% Triton X-100 | λ: 380–420 nm | |||||

| I: 0.5 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 50 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + HEMA + TMPTA (6:3:1) | DLP (AutoCera) | 10–15 Pa s at 50 Hz | S: 1250 °C | [60] | |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 2 wt% Solsperse 17000 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| I: 8 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 50 wt% | Commercial resin: Shanghai, China | DLP (custom) | _ | S: 1500 °C for 3 h | [132] | |

| 35 vol% | Commercial resin: Rigid resin (XYZ Printing inc. Taiwan) + HDDA (∼3:5) | SLA (Novel 1.0, XYZ) | 3.6–6 Pa s | S: 1250 °C | [102] | |

| Dispersant: 1.5 wt% BYK 180 | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| 30 vol% | Monomer: HDDA | DLP (Photon, Anycubic) | _ | S: 1250 °C for 2 h | [59] | |

| Initiator: BAPO (Omnirad 819) | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 0.15 wt% OA | ||||||

| 55 wt% | Monomer: HDDA | DLP | 380 mPa s at 52 Hz | S: 1250 °C for 3 h | [106] | |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 30 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 3 wt% BYK (not specified) | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| I: 15 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 50 vol%/68 wt% | Monomers: OPPEA + HDDA (mass ratio 1:1) | SLA (Ceramaker 100) | 1.25 Pa s at 100 Hz | S: 1100, 1200, 1300 °C for 2 h | [41] | |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 0.2 wt% S18 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| P: 30 mW | ||||||

| 30 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + TMPTA (4:1) | DLP (AutoCera) | _ | S: 1250 °C for 2 h | [104] | |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: Solsperse KOS163 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| I: 0.9 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 45 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + HEMA + TMPTA (6.3:1) | DLP (AutoCera) | _ | S: 1250 °C for 2 h | [64] | |

| Initiator: 1.5 wt% TPO (regarding resin) | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 2 wt% Solsperse 17000 (regarding powder) | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| I: 8 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 60 wt% | Monomer: Not specified | DLP (Admaflex 130) | _ | S: 1150 °C for 2 h | [107] | |

| Initiator: TPO | ||||||

| Dispersant: BYK 2155 | ||||||

| 46 vol% | Commercial: LithaBone HA400 (Lithoz GmbH) | DLP (CeraFab7500) | _ | S: 1300 °C | [125] | |

| LH: 25 μm | ||||||

| I: 56 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 50 vol% | Commercial: Dentifix-3D (FunToDo®) | mSLA (Phrozen shuffle) | 0.065 Pa s at 100 Hz, <5 Pa s at 1 Hz, TSI<2 | S: 1250 °C for 2 h | [117] | |

| Diluent: 35 vol% PEG-200 | LH: 100 μm | |||||

| λ:405 nm | ||||||

| P: 50.000 mW | ||||||

| 38 vol% | Commercial: 62 vol% LithaBone, not specified (Lithoz GmbH) | DLP (CeraFab7500) | _ | CD: LithasSol 80 | [133] | |

| LH: 25 μm | S: 900–1300 °C | |||||

| 40 vol% | Monomer: Acrylate oligomers (ACMO) | LCD-DLP (Phrozen) | 1,2 Pa s - 1.8 Pa s at 10 Hz | S: 1250 °C for 9 ha | [115] | |

| Absorber: Light Stabilizer 292 | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: SPA | λ: 460 nm | |||||

| 55 wt% | Commercial: Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer kit (3DCeram Sinto, France) | SLA (3DCeram Sinto) | _ | S: 1280 °C for 1 h | [134] | |

| LH: 100 μm | ||||||

| P: 48 mW | ||||||

| 0-60 wt% | Monomer: Cyracures UVR-6105 | SLA (custom) | <3 Pa s at 100 Hz | _ | [43] | |

| Initiator: Cyracures UVI-6976 | LH: 100 μm | |||||

| λ: 370 nm | ||||||

| P: 300 W | ||||||

| 27 wt% | Monomer: methacrylate-based (not specified) | DLP (custom) | _ | S: 1300 °C for 2 h | [135] | |

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| I: 28 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 50 wt% | Polyfunctional acrylic resins (not specified) | SLA (Prodways V6000) | _ | S: 1125 °C, for 5 h | [136] | |

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| 50-56 vol% | Monomer: MBAM | SLA (SPS450B) | <3 Pa s at 30 Hz | S: 1080 °C | [96] | |

| Initiator: photocure-1173 | LH: 100 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: ammonium polyacrylate | P: 300 mW, d: 20.3 mJ/cm2 | |||||

| 10-45 wt% | Commercial: DSM's Somos (ABSlike) | DLP (LAYING II 1510P) | _ | D: 500 °C | [137] | |

| LH: 50 μm | S: 1250 °C | |||||

| 5, 10, 20 wt% | Commercial resin: FormLabs Ceramic RS-F2-CEWH-01 | SLA (FormLabs Form2) | 3.4–4.1 Pa s at 12 rpm | D: up to 300 °C | [138] | |

| λ: 405 nm | S: 1270 °C | |||||

| LH: 100 μm | ||||||

| 60 wt% | Monomers: PUA + PEGDA (Mn 400) (3:1 ratio) | DLP (Admaflec 130 plus) | _ | S: 1150 °C for 2 h | [139,140] | |

| Coating: GelMA (20 wt%) + Icariin (for drug release) | ||||||

| Initiator: 2 % TPO-L | ||||||

| Dispersant: BYK 2155 | ||||||

| 50 wt% | Monomers: HDDA | LCD-DLP (Sonic 4K, Phrozen) | <150 mPa s | D: up to 600 °C | [141] | |

| Initiator: 3 wt% TPO | LH: 50 μm | S: 1200 °C for 2 h | ||||

| Dispersant: BYK 111 | ||||||

| 50 wt% | Monomers: UA + PEGDA (Mn400) (3:1) | DLP | _ | S: 1150 °C for 2h | [142] | |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: BYK 2155 | ||||||

| 45 wt% | Monomer: HDDA | DLP (Autocera-R) | 1 Pa s at 50 Hz | S: 1200 °C | [95] | |

| Initiator: 1.5 wt% BAPO (regarding resin) | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: 5 wt% Solsperse 41000 (regarding ceramic) | ||||||

| Absorbers: 0.2 wt% MEHQ (regarding resin) | I: 5 mW/cm2 | |||||

| Porogen: ethylene glycol | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| 50-70 wt% | Monomers: UA + PEGDA-400 (3:1) | DLP (Admaflec 130+) | 0.3–2 Pa s | S: 1050-1150-1250 °C for 2h | [49,50] | |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 65 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: BYK 2155 | ||||||

| HA + Al2O3 | 20-80 wt% | Monomers: Trimethylolpropane formal acrylate + PEGDA | DLP (CeraStation 160) | _ | S: 1400 °C | [143] |

| Initiator: BAPO | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: SP710 | I: 127.23 mW/cm2 | |||||

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| HA + ZrO2 | 45-70 wt% | Commercial: (Shanghai Guangyi Chemical Co., Ltd.) and (Shanghai Prismlab Co., Ltd.) respectively | DLP (custom, SU-100A) | _ | D: 500 °C for 4 h | [45,46] |

| Dispersant: 2 wt% SPA | LH: 20 μm | S: 1400 °C for 1.5h | ||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| I: 10 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 70 wt% | Monomer: PEGDA (Mn 600) | DLP (custom) | _ | S: 1200, 1300, 1400 °C | [37] | |

| Initiator: TPO | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Absorber: Sudan red | I: 0.9 mW/cm2 | |||||

| Dispersant: KH-570 | ||||||

| _ | Monomers: PEGDA + Hydroxyethyl methacrylate phosphate | DLP | _ | S: 1200 °C | [144] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 % TPO | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: KH-570 + ACMO | LH: 40 μm | |||||

| Absorber:3·10−5 wt% Sudan | ||||||

| 10-60 wt% | Monomers: 45 % HDDA + 35 % ACMO + 15 % TMPTA + 5 % hyperbranched polyester acrylate | DLP (custom) | 10–100 mPa s at 100 Hz | D: up to 600 °C | [63] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 % BAPO (Omnirad® 819) | λ: 405 nm | S: 1100–1250 °C | ||||

| Dispersant: KH-570 + OA + Castor oil | ||||||

| HA + AK (9:1) | 40 vol% | Monomers: 60 wt% HDDA + TPGDA (7:3) | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | D: 600 °C for 3 h | [[56], [57], [58]] |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% TPO | LH: 50 μm | S: 1000–1250 °C for 2h | ||||

| Dispersant: 4 wt% Solsperse 41000 | d: 8 mJ/cm2 | |||||

| 40 vol% + nano-Fe3O4 | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA (7:3) | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | S: 1100 °C for 2 h | [105] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% TPO (regarding resin) | ||||||

| Dispersant: 4 wt% Solsperse 41000 | ||||||

| Si-HA | 55 vol% | Monomer: amine modified polyester acrylate | DLP (PμSLA) (Xianlin 3D) | 2 Pa s at 150 Hz (<5 Pa s) | S: 1160–1200 °C for 2 h | [88] |

| Initiator: EDMD | LH: 250 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: phosphate ester | λ: 365 nm | |||||

| HA + SiO2 | 35 wt% | Monomer: 60 wt% SR454NS acrylic resin | DLP | <4 Pa s | S: 1200 °C for 3 h | [120] |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% Ethyl 4-(Dimethylamino) benzoate | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 2 wt% TAEA | ||||||

| HA + Sr2+ + Mg2+ + Zn2+ | 38 vol% | Commercial resin: 62 vol% Lithoz GmbH | DLP (CeraFab 7500) | _ | D: up to 500–600 °C | [133] |

| LH: 25 μm | S: 900, 1000, 1100, 1200. 1300 °C | |||||

| HA + CaSiO2 + SrPO4 + CaSO4 | 30 wt% | Monomers: acrylic, acrylate monomer | DLP (custom) | _ | D: up to 715 °C for 3 h | [116] |

| Dispersant: SPA | LH: 40 μm | S: 1300 °C for 2 h | ||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| HA + BR | 55 wt% | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA (7:3) | DLP | 0.5–1 Pa s at 30 Hz | D: up to 600 °C | [145] |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% TPO | S: 1300 °C for 2 h | |||||

| Dispersant: 4 wt% BYK 111 | ||||||

| HA + BG (8:2) | 50 wt% | Commercial rigid resin (Anycubic) | LCD-DLP | _ | D: 600 °C at 5 °C/min for 2h | [146] |

| S: 1300 °C at 5 °C/min | ||||||

| HA + ZnO | 60 wt% (95–15, 90–10) | Monomers: PUA + PEGDA (Mn 400) (3:1 ratio) | DLP (Admaflec 130 plus) | _ | S: 1150 °C for 2 h | [147] |

| Initiator: 2 % TPO-L | ||||||

| Dispersant: BYK 2155 | ||||||

| HA + BT (5:5, 3:7, 1:9) | 55 wt% | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA | DLP (Admaflex 130) | _ | D: up to 600 °C at 1 °C/min | [148] |

| Initiator: Initiator 819 (BAPO) | λ: 405 nm | S: 1300 °C for 3h at 3 °C/min | ||||

| Absorber: HEMQ | LH: 40 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: Triton X-100 | ||||||

| HA + BT (2:8) | 45 vol% | Monomers: HDDA | DLP (Cerafab7500) | 0.287 Pa s | D: up to 468 °C at 0.5–1 °C/min | [149] |

| Initiator: Aladdin, Shanghai | λ: 453 nm | S: 1300 °C for 3h at 2 °C/min | ||||

| Dispersant: 2 wt% KH-570 | I: 87 mW/cm2 | |||||

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| HA + BT (3/7) + ZnO | _ | Monomers: 80 % PEGDA (Mn 600) | DLP | _ | D: up to 600 °C | [150,151] |

| Initiator: 2 % TPO-L | I: 2.5 mW/cm2 | S: 1250 °C for 2 h | ||||

| Dispersant: 15 % KH-570 | LH: 20 μm | |||||

| Absorber: 3 % Sudan red | ||||||

| Whitlockite | 75 wt% | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA (7:3) | DLP (Anycubic D2) | 0.5 Pa s at 30 Hz | D: up to 600 °C | [152] |

| Initiator: 3 wt% TPO | S: 1000 °C for 2 h | |||||

| Dispersant: 18.7 wt% BYK 111 | ||||||

| β-TCP | 60 wt% | Monomers: PEGDA (Mw = 200) + β-CEA + HDDA (30: 5.2: 4.8) + HA-DA | DLP (custom) | _ | S: 1150 °C | [153] |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: KH-570 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| 60 wt% | Monomers: PEGDA (Mw = 200) + β-CEA + HDDA | DLP (custom) | 2–3 Pa s (<3 Pa s at 30 Hz) | D: up to 536 °C | [97] | |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | S: 1150 °C for 4 h | ||||

| Dispersant: 1 wt% KH-570 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| 70 wt% | Monomers: AM + MBAM | SLA (custom) | _ | D: 80 °C/h to 660 °C, 115 °C/h to 700 °C | [38] | |

| Initiator: 0.02 wt% photocure-1173 | S: 360 °C/h to 1150 °C for 1 h | |||||

| Dispersant: SPMA | ||||||

| 65 wt% | Commercial: CryoBeryl Software, France | SLA (CryoCeram) | _ | S: 1050 °C for 3 h at 5 °C/min | [154] | |

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| λ: 350–400 nm | ||||||

| I: 5 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 71 wt% | Monomers: 50 wt% HDDA + TGDA + HEMA + TTA + PEGDA | SLA (Admaflex 130) | 3.5–4.4 Pa s (5–10 Pa s < 300 Hz) | S: 1100 °C for 3h | [155] | |

| Initiator: 1 wt% TPO | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: 0.5 wt% Zelec P312 | ||||||

| Diluent: 10 wt% PEG200 | ||||||

| 52 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + OPPEA | DLP (CeraRay CR-1) | 5.76 Pa s at 100 Hz | D: up to 450 °C | [93] | |

| Initiator: 1 wt% TPO | LH: 100 μm | S: 1000 °C for 2 h | ||||

| Dispersant: 2 wt% S18 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| 50 vol% | Commercial: HDDA, TMPTA, epoxy acrylic resin (Liangzhi chemical, Germany) | SLA (Ceramaker) | _ | S: 1100 °C | [108,109] | |

| Dispersant: 2.5 wt% BYK 110 | λ: 355 nm | |||||

| P: 180 mW | ||||||

| 30 wt% | Commercial: photosensitive resin (Anycubic Co, Shenzhen, China) | DLP (custom) | _ | S: 1150 °C for 3 h | [119] | |

| Dispersants: 2 wt% PEG-600 + 3 wt% 1,5-pentanediol | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| 40-60 wt% | Commercial: acrylic resin (FTD Standard Blend 3D Printing resin, Fun To Do, Alkmaar, The Netherland) | DLP (3DLPrinter-HD 2.0) | _ | S: 1200 °C for 2 h | [156,157] | |

| Dispersant: 0.1 wt% OA (regarding resin) | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| λ: 400–500 nm | ||||||

| I: 10 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 40 vol% | Commercial: acrylic resin (FTD Standard Blend 3D Printing resin, Fun To Do, Alkmaar, The Netherland) | DLP (3DLPrinter-HD 2.0) | 1.9 Pa s at 10 Hz | S: RSA (rapid sintering) 5 min dwell, CSA (conventional sintering) 2 h dwell, SPS (vacuum) 5 min dwell at 1200, 1300, 1400, 1500 °C | [[158], [159], [160]] | |

| Diluent: 30 wt% Camphor | LH: 25–50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 0.1 wt% OA (regarding resin) | λ: 385 nm | |||||

| I: 31 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 40 vol% | Commercial: resin (ELEGOO) | DLP (3DLPrinter-HD 2.0) | _ | S: Conventional sintering (CS): 1200 °C for 3 h; 2-step sintering (2SS): 1250/1270/1290/1310 °C for 2 min + 1000 °C for 3 h | [121] | |

| Dispersant: 6 wt% Disperbyk 110 | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| I: 13.2 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 40 wt% | Commercial: 60 wt% FLGPCL02, Formlabs | SLA (SEPS) (custom) | _ | S: 1250 °C for 3 h | [161] | |

| LH: 100 μm | ||||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| 47 vol% | Commercial: Lithabone TCP 300 (Lithoz GmBH, Austria) | DLP (LCM) (Cerafab7500) | 6–12 Pa s | D: up to 850 °C | [103] | |

| LH: 25 μm | S: 1200 °C | |||||

| I: 101 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| _ | Commercial: LithaBone TCP 380 D | DLP (Cerafab7500) | _ | D: 96 h | [122] | |

| LH: 25 μm | S: 1200 °C for 2 h | |||||

| 45 wt% | Commercial: resin (WANHAO Co.) | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | S: 1150 °C for 3 h | [162] | |

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| 50 wt% | Commercial: resin (Suzhou Ding'an Technology Co.) | SLA (custom) | _ | _ | [163] | |

| Dispersant: SPA | I: 10 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 40 vol% | Monomers: TMPTA + HDDA (1:1) | DLP (M-Jewelry U30) | <3 Pa s at 30 Hz | D: 600 °C for 2 h | [55,61,62] | |

| Initiator: BAPO (Omnirad® 819) | LH: 15–65 μm | S: 1100 °C for 2 h | ||||

| Absorber: graphite | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: KH-550 | I: 2.19 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 68 wt% | Commercial resin | SLA (CryoCeram) | _ | D: 600 °C for 1 h at 1 °C/min | [164] | |

| Dispersant: Darvan C + B1001 | LH: 50 μm | S: 1000, 1050, 1120 °C for 3 h at 5 °C/min | ||||

| 60 wt% _ |

Monomers: Aliphatic UA + HDDA (6:4) | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | S: 1100 °C | [165] | |

| Initiator: Hydroxy cyclohexyl phenyl ketone | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: phosphoric acid ester | I: 10 mW/cm2 | |||||

| Monomer: PEGDA (Mw = 200) | DLP | _ | D: up to 440 °C | [166] | ||

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | S: 1150 °C for 3 h | ||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| 43.1 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + TMPTA | SLA (Ceramaker 300) | _ | S: 1200 °C | [167] | |

| Initiator: 3 % TPO | LH: 100 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 5 % JOS-110 | λ: 365 nm | |||||

| I: 52 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| 45 wt% | Commercial resin: 50 % SP700 photosensitive acrylic resin | DLP (Shaoxing) | _ | S: 1160 °Cat 2 °C /min | [110] | |

| Dispersant: 5 % BYK 111 | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| 50 wt% | Monomer: 49 wt% HDDA | SLA (Cerafab 8500) | _ | D: 200 °C for 16 h | [168] | |

| Initiator: 1 wt% CQ | LH: 25 μm | S: 1200 °C for 4 h | ||||

| λ: 406 nm | ||||||

| I: 200 mW/cm2 | ||||||

| β-TCP + MgO | 43 wt% | Commercial: 57 wt% resin, shanghai guangyi chemical co. | DLP (custom) | _ | S: 1500 °C for 3 h | [169,170] |

| Dispersant: 4 wt% SPA | ||||||

| 50 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA (7:3) | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | S: 1250 °C for 2 h | [171] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% TPO | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| Absorber: 0.1 wt% P-hydroxyanisole | d: 12.4 mJ/cm2 | |||||

| Dispersant: Solsperse 41000 (Lubrizol) | ||||||

| β-TCP + BG-58S (8:2) | 45-60 wt% | Monomer: PEGDA | DLP | 30.5–85.92 Pa s at 10 Hz | _ | [53] |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersants: DCA-1228 + PPG | ||||||

| β-TCP + BG | 52 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + OPPEA | DLP (CeraRay 1) | _ | D: 370, 420, 460 °C for 2 h | [172] |

| Initiator: 1 % TPO | LH: 100 μm | S: 710 °C | ||||

| β-TCP + Laponite | 50-60 wt% | Monomer: PEDGA (200) | DLP | _ | _ | [52] |

| Initiator: 0.5 % TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: DCA-1228 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| β-TCP + α-CS | 55 vol% | Monomers: TPGDA + TMP3EOTA | SLA (3DCeram C900) | 40–50 Pa s | S: 1100 °C for 3 h | [173] |

| Initiator: 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenylbenzene | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Dispersants: KH-560 (3–5 %) + KOS110 + Ammonium polyacrylate | λ: 355 nm | |||||

| P: 128 mW | ||||||

| TCP (not specified) | 60 vol% | Acrylate resin (not specified) | SLA (B9Creator) | 0.1–1 Pa s at 1 Hz (<1000 cP) | _ | [174] |

| Dispersant: Surfactant Darvan C (Vanderbilt, USA) | ||||||

| BCP (15/85) | _ | Monomer: Commercial resin type B-0#, Ten Dimensions Technology | DLP (Autocera-L) | _ | S: 1200 °C | [175] |

| Initiator: TPO | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: Solsperse 17000 | I: 24.5 mW/cm2 | |||||

| LH: 25 μm | ||||||

| BCP (1:1) | 35 vol% | Monomer: HDDA | DLP (3DP-21ODS) | 0.47–0.10 Pa s at 0.1–100 Hz | S: 1200 °C for 3 h | [113] |

| Initiator: 1.5 wt% BAPO (Omnirad 819) | LH: 25 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 4 wt% BYK 2001 | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Diluent: 40 wt% Camphor | I: 16.4 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 40-70 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + PMMA (as porogen agent) | DLP | 0.26–0.55 Pa s at 10 Hz | D: 600 °C | [112] | |

| Initiator: 2 wt% PPO (BAPO) | LH: 100 μm | S: 1200 °C for 3 h | ||||

| Absorber: 4 wt% benzopurpurin 4B | ||||||

| Dispersant: Disperbyk 2001 | ||||||

| Diluent: 40 wt% Camphor | ||||||

| 70 wt% | Monomers: IBOA, HDDA, PEGDA (1:3:1) | DLP | 0.8 Pa s at 40 Hz (<3 Pa s) | D: 700 °C | [176,177] | |

| Initiator: 1 wt% TPO (regarding resin) | d: 10 mJ/cm2 | S: 1200 °C for 2 h | ||||

| Dispersant: 4 wt% BYK 111 (regarding ceramic) | LH: 35 μm | |||||

| 65 wt% | Monomer: 28.86 wt% HDDA | DLP (Asiga Max) | 400 mPa s at 50 Hz | S: 1100, 1200, 1300 °C | [47] | |

| Initiator: 1 wt% TPO | ||||||

| Dispersant: 9 wt% BYK 111 | ||||||

| BCP (6:4) | 40-60 wt%a _ |

Monomers: UDMA + camphene-camphor (ratio 2:1) | DLP | _ | S: 1250 °C for 3 h | [178] |

| Initiator: 2 wt% TPO | LH: 220 μm | |||||

| Dispersant: 3 wt% KD4 (Croda, Everberg, Belgium) | ||||||

| Commercial: acrylic monomers, trade secret of Genoss® | DLP (Cubicon Lux) | _ | _ | [179] | ||

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| 50 wt% | Commercial: polyfunctional acrylic resin (Sirris, belgium) | SLA (Optoform) | _ | S: 1125 °C, for 5 h | [180] | |

| LH: 50 μm | ||||||

| 64 wt% | Monomers: Acrylic monomers (proprietary info) | DLP (Cubicon Lux) | _ | S: 1250 °C for 10 h | [181] | |

| Initiator: TPO | ||||||

| 40 wt% | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA (7:3) | DLP (Autocera-M) | <5 Pa s over 60 Hz | S: 1100 °C for 2 h | [100] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Absorber: 0.1 wt% MEHQ | d: 12.5 mJ/cm2 | |||||

| Dispersant: 4 wt% Solsperse 41000 (Lubrizol) | ||||||

| BCP (7:3) | 20 vol% | Commercial: resin FA1260T; SKCytec | DLP (pMSTL) (custom) | _ | S: 1400 °C | [182] |

| 65 wt% | Photosensitive resin (not specified) | DLP (Admaflex 130+) | _ | D: 800 °C for 2.7 h | [183] | |

| LH: 50 μm | S: 1100 °C for 5 h | |||||

| _ | Monomers: UA + PEGDA (Mn400) (3:1) | DLP (Admatec 130) | _ | S: 1050 °C for 2 h | [111] | |

| Initiator: TPO | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: BYK 2155 | ||||||

| BCP | 50 wt% | Not specified + toners as pore forming agents | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | _ | [184] |

| Dispersant: MAEP | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| 50 wt% | Not specified + 2 wt% toners as pore-forming agents | DLP (Autocera-M) | 3 Pa s at 30 Hza | S: 1100 °C for 2 h | [185] | |

| Dispersant: MAEP | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| λ: 405 nm | ||||||

| 50-60 wt% | Monomer: HDDA | DLP (Autocera-M) | 5 Pa s at 30 Hza | S: 1100 °C for 2 h | [54] | |

| Initiator: BAPO | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: steric acid, sebacic acid, OA, MAEP | I: 10–34 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 50 wt% | Monomer: HDDA | DLP (Autocera-R) | _ | D: up to 466 °C | [91] | |

| Initiator: 2 wt% Irgacure® 819 (BAPO) | λ: 405 nm | S: 1250 °C | ||||

| Dispersant: 5 wt% Solsperse 41000 | I: 5 mW/cm2 | |||||

| Absorber: 2 wt% MEHQ | LH: 30 μm | |||||

| 45 wt% | Monomers: HDDA + TMP3EOTA | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | D: up to 550 °C | [55] | |

| Initiator: BAPO (Omnirad® 819) | λ: 405 nm | S: 1100 °C | ||||

| Dispersant: Disperbyk 111 | I: 3.1–7.4 mW/cm2 | |||||

| BCP (6:4) + BG | 30 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA + PEG (54:23:23) | DLP (Autocera-M) | _ | D: up to 650 °C for 1 h | [186] |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% TPO (regarding resin) | λ: 405 nm | S: 1200 °C for 2 h | ||||

| Dispersant: 5 wt% Solsperse 41000 + 1 wt% RAD2500 | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Absorber: 0.1 wt% Easepi 590 | ||||||

| BCP + BG 45S5® | 40 vol% | Monomers: HDDA + TPGDA | DLP (Autocera-M) | 0.1–2.2 Pa s at 20 Hz | S: 1200 °C for 2, 4, 6 h | [57] |

| Initiator: TPO | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Absorber: MeHQ | λ: 405 nm | |||||

| Dispersant: Solsperse 41000 | d: 12.54 mJ/cm2 | |||||

| α-TCP | 45 wt% | Commercial: 50 % SP700 photosensitive acrylic resin | DLP (Shaoxing) | _ | S: 1240 °C | [110] |

| Dispersant: 5 wt% BYK 111 | LH: 50 μm | |||||

| Ca2,5Na(PO4)2 | _ | Monomers: Laromer 8889 + HDDA | DLP (Ember) | _ | S: 1200 °C for 12 h | [114] |

| Initiator: TPO-L | LH: 30–50 μm | |||||

| Absorbers: Sudan II orange + Carbon black | d: 170 mJ/cm2 | |||||

| Dispersant: Triton X-100 | ||||||

Abbreviations: α-β-TCP: tricalcium phosphate, α-CS: α-calcium silicate, β-CEA: β-carboxyethyl acrylate, ACMO: acryloylmorpholin (4-(1-oxo-2-propenyl)-morpholine), AK: akermanite, AM: acrylamide, BAPO: phenylbis(2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoyl)-phosphineoxide, BCP: biphasic calcium phosphate, BG: bioglass, CEA: β-carboxyethyl acrylates, CQ: camphorquinone, EDMD: ethanone, 2,2-dimethoxy-1,2-diphenyl, HA: hydroxyapatite, HA-DA: hyaluronic acid-dopamine, HDDA: 1,6-hexanediol diacrylate, HEMA: 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, IBOA: isobornyl acrylate, MAEP: monoalcohol ethoxylate phosphate, MBAM: N-N′ methylenebisacrylamide, MeHQ: p-hydroxyanisole, OA: oleic acid, OPPEA: 2-([1,1′-biphenyl]- 2-yloxy) ethylacrylate, PEG: poly(ethylene glycol), PEGDA: poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate, PMMA: poly(methyl methacrylate), PPG: polypropylene glycol, PPO: phenylbis (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide, SPA: sodium polyacrylate, SPMA: sodium polymethacryate, TAEA: tris(2-Hydroxyethyl) amine, TGDA: tetraethylene glycol diacrylate, TMP3EOTA: ethoxylated trimethylolpropane triacrylate, TMPTA: trimethylol-propane triacrylate, TPGDA: tripropylene glycol diacrylate, TPO: diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide, TPO-L: ethyl phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphinate, TTA: trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate, UA: urethane acrylate, UDMA: diurethane dimethacrylate.

Commercial chemicals: Irgacure® 819/Omnirad® 819 (BAPO): phenylbis(2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoyl)-phosphineoxide, KH-550: 3-aminopropyl triethoxy silane, KH-560: γ-glycidyloxy-propyltrimethoxy silane, KH-570: γ-methacryloxy-propyltrimethoxy silane, Photocure-1173: 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone, SR454NS: ethoxylated (3) trimethylolpropane triacrylate, Triton® X-100: t-octilfenoxipolietoxietanol, Zelec P312: alcohol phosphates.

Values taken indirectly from graphs and not explicitly described on article's text.

3.1.3. Photoabsorbers

One intrinsic challenge of VP is the precision of the projected light. Light must travel through different materials, from the light source to the tank's bottom film, and finally to the photosensitive resin contained in the building gap. These materials present different refraction indices causing changes in the behavior of light waves. These changes can cause reflection, refraction, and finally scattering phenomena, with loss of light directionality and spreading of the light beam spots [30], thus reducing printing precision. Light-absorbing molecules (photoabsorbers), which attenuate the light scattering are often added to improve the printing resolution and pattern fidelity [30], although they might require longer exposure times and higher photoinitiator concentrations [84]. Improved printing resolution is obtained by a balance between these additives. Typical absorbing molecules include Orasol Orange G (absorbing λopt.range 480–500 nm) [[65], [66], [67], [68], [69]], Quinoline Yellow (absorbing λopt_range 400–450 nm) [85], Tartrazine (absorbing λopt.range 425–450 nm) [86], and Sultan I (absorbing λopt.range 385–415 nm [87].

Resin composition and printing parameters are intrinsically dependent and thus, they need to be tightly balanced to obtain optimal printability. Two key indicators often used to assess optimal printability are cure depth (Cd) and resin viscosity. Cure depth is the farthest point where the light is able to cure the photosensitive resin, thus is highly dependent on the interaction between light and resin. These interactions can be modified either by tailoring the resin formulation or by adjusting the light exposure parameters such as energy, intensity or exposure time, depending on the printing device. To ensure printability, the distance between layers (layer height) must be smaller than Cd.

The reactivity of a resin is commonly evaluated by curing it in a build plate-free volume, where the light penetration is unlimited. By varying the energy dose (i.e., light intensity) and exposure times, different thicknesses of cured resins are obtained. The Cd is represented versus the logarithm of the exposure times while keeping the light energy constant, or versus the logarithm of the light intensities while keeping the layer height constant. These calculations allow identifying the critical energy dose, according to Jacobs's equation (Equation (2)), characteristic of each resin formulation [88]. This empirical equation is commonly used in the literature to analyze experimental data on cure depth to determine the depth of penetration (Dp) and the empirical constant of critical energy (Ec). These values are then used to determine the layer thickness of each layer for light-based fabrication [89].

| Equation 2 |

where Cd represents the cure depth, Ei is the energy dosage per area, Ec represents the “critical” energy dosage, and Dp refers to the “depth of penetration” of the laser beam into the solution, which is inversely proportional to the molar extinction coefficient and the concentration of photoinitiator.

Finally, a key parameter in VP approaches is the rheological behavior of the resin. Resins require a shear-thinning behavior which implies that the resin's apparent viscosity decreases when the shear stress increases, and is due to shear-induced disentanglement of the long polymeric chains. The polymeric chains, which are entangled at rest, align upon shearing, reducing the internal resistance to flow and, thus, its viscosity [90], ensuring printability [91]. Shear-thinning behavior favors an easier flow of the resin underneath the build plate, allowing layer-by-layer printing. This type of characteristic behavior is described by the Herschel-Burkley model (Equation (3)), which allows calculating some rheological parameters, such as the yield stress (), which can be used to characterise the properties of the VP resins.

| Equation 3 |

3.2. Calcium phosphate-loaded photocurable resins

The addition of CaPs into VP resins affects key parameters needed for printability such as the rheological properties of the resins and the light interactions with the light sources. Light penetration is hindered by the suspended particles causing light scattering and light absorption [92]. As a result, these changes in light interaction affect the cure depth (Equation (2)) of the resins. On the other hand, CaPs addition to the resin highly affects the resin's rheological behavior. Resin viscosity increases with the addition of ceramic fillers and can compromise printability. Furthermore, the ceramic filler hydrophilicity, when combined with common hydrophobic resin monomers, can cause agglomeration and sedimentation [93]. The main effect due to the incorporation of ceramic particles is on the shear-thinning behavior of the resins, typically increasing their yield stress (, see Equation (3)). However, high yield stress is commonly considered to be an obstacle to the spreading of new layers and the yield stress tends to rise with increasing solid content [94].

A strategy widely used to modify the rheological properties and suspension stability in ceramic-loaded resins is by adding dispersant molecules which help stabilize the viscosity during the printing process. Dispersants form a protective film on ceramic particles preventing particle collision and maintaining the resin viscosity stable [60]. As dispersant molecules start to adsorb on the surface of ceramic particles, the repulsive forces between particles increase, reducing the viscosity of the slurry. Nonetheless, there is a limit to dispersant adsorption on ceramic particles due to the limited number of dispersant molecules that can be adsorbed onto their surface [41]. When excessive dispersant is added, excess dispersant results in flocculation and subsequent viscosity increase [47,91,95]. This phenomenon also limits the ceramic loading capacity. Generally, the reported viscosity limit for slurries ranges from 3 Pa s [39,43,62,[96], [97], [98]] to 5 Pa s [54,86,99,100], although higher viscous slurries have been successfully used [[101], [102], [103]]. Commercially available dispersants, such as commercial Solsperse® variants [57,60,64,104,105], BYK® variants [47,49,50,102,[106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113]], or common surfactants such as Triton® X-100 [51,114], or sodium polyacrylates [45,46,101,115,116], beyond others, are used to lower the viscosity of the slurry, tuning their printability.

In the case of calcium phosphates, the most commonly used ceramic fillers are hydroxyapatite (HA), β-tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP), and a combination of both known as biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP) [60,113,[117], [118], [119], [120]]. In fact, over 90 % of the reviewed literature use these three CaPs, purely or together with other ceramic fillers such as zirconia (ZrO2), magnesium oxide (MgO), and bioglass, among others (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

(A) Schematic representation of post-printing processes resulting in composite or full ceramic parts. Composite scaffolds, consist of a continuous polymeric matrix containing dispersed ceramic particles. Full ceramic scaffolds are obtained through a high-temperature treatment consisting in debinding and sintering. The resulting microstructure consists of ceramic particles bound together. (B) Schematic representation of different calcium phosphate ceramics and other inorganic components used on both the full-ceramic route (in red) and composite route (in blue), following Table 2, Table 3 (Abbreviations: α-CS: α-Calcium silicate, AK: akermanite, BCP: biphasic calcium phosphate, BG: bioglass, BR: bregidite, BT: barium titanate, CPP: calcium pyrophosphate, HA: hydroxyapatite, MAEP: monoalcohol ethoxylate phosphate, MCPM: mono-calcium phosphate monohydrate, OCP: octacalcium phosphate, Si-CaP: silicon-calcium phosphate, SWCNT: single-walled carbon nanotube, TCP: tricalcium phosphate).

4. Fabrication routes

The resin composition, formulation and printing configuration are closely linked to the fabrication route used. In the literature, two main approaches are identified: producing fully ceramic scaffolds or polymeric-ceramic composite scaffolds. The resin composition and characteristics vary depending on the selected route. In the case of full ceramic scaffolds, the polymeric resin serves a critical role in the printing process but is subsequently removed through high-temperature treatments. Careful consideration of the debinding and sintering processes is essential to ensure structurally robust ceramic frameworks. In contrast, composite scaffolds maintain the polymeric phase, which remains an integral part of the final structure.

Once printed, the scaffolds can be further processed to adjust their physicochemical, mechanical or structural properties. Full ceramic bodies can be obtained by applying a thermal treatment that includes a debinding and a sintering step. The polymer matrix is removed during the debinding process, and the ceramic particles are fused together by solid-state diffusion during the sintering step. Alternatively, the polymeric matrix can be maintained, resulting in a composite scaffold based on a continuous polymeric matrix with dispersed ceramic particles (Fig. 2A). These two processing routes result in two distinct types of scaffolds, with different properties mainly in terms of mechanical and biological response. The first route is the most commonly followed, accounting for 75 % of the analyzed publications. Conversely, only 25 % of the published studies have investigated composite scaffolds (Fig. 2B).

4.1. Full ceramic scaffolds

Full ceramic scaffolds are obtained by removing the polymeric matrix and sintering the ceramic particles through thermal treatment. In this approach the polymeric resin is used as a sacrificial support, and the final goal is to obtain a full-ceramic part.

Commonly, the thermal treatment consists first of a debinding step to decompose the polymeric matrix. The temperature applied is usually slightly above the degradation temperature of the polymer used in the resin. The debinding temperature is often determined by Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA-DTG), which allows to identify the temperature range where the crosslinked polymer decomposes, and a thermal treatment is designed including a slow heating ramp and a dwell time to ensure total polymer debinding and simultaneously preserve the structural integrity of the scaffold [113,121]. Debinding steps are usually programmed with several steps including dwelling times at each step which ensures a homogeneous decomposition of the polymer without affecting the structural integrity of the scaffolds. After eliminating the polymeric phase, the scaffolds undergo a sintering process at high temperature to allow for solid-state grain boundary atomic diffusion, resulting in the consolidation of a full-ceramic part. The sintering temperature, heating ramp, and dwell times affect the grain growth and have a clear effect on the resulting microstructure. This process is commonly set depending on the material to avoid cracks or inconsistent gaps and undesired porosity. Low sintering temperatures lead to loose grains resulting in an increased number of pores, whereas higher temperatures promote grain coarsening, abnormal growth, and may even cause ceramic cracking and failure [41]. Resin formulations and processing parameters reported in the literature for the fabrication of full CaP ceramic scaffolds by VP are summarized in Table 2, including several commercially available CaP-resins, such as Lithabone® from Lithoz GmbH [103,[122], [123], [124], [125], [126]], Dental resin DETAX® [127], Cerhum® [128,129], for which the exact composition is often confidential [40]. Abbreviations can be found in footnotes bellow the table or in Table S1 (supplementary information).

4.2. Composite scaffolds

The high brittleness of full ceramic CaP scaffolds has encouraged the development of composite CaP specimens [157]. These composites must meet certain requirements of biocompatibility and resorbability. Therefore, the polymers used in the resin formulation should also be biocompatible and bioresorbable, degrading upon contact with organic fluids, and disappearing completely from the organism once the defected area is healed without any acidic degradation by-products [65]. In this approach the crosslinked polymeric structure is preserved, resulting in a composite material where a polymer matrix embeds ceramic particles that act as reinforcing agents. Polymer-ceramic printed scaffolds offer a promising solution for bone grafts, combining the strength and flexibility of both components. In this context, the photocrosslinkable resin is no longer a sacrificial phase and becomes an integral part of the final scaffold.

Commonly used resins in this particular approach entail the use of acrylated groups capable of reacting upon light irradiation. However, acrylated resins can exhibit high irritancy levels or even cytotoxicity in the uncured state. The leaching of unreacted monomers/oligomers or photoinitiators, as a result of low double-bond conversion rates, which is used as an indicator for the extent of the reaction, may cause health risks. Chen et al. illustrated the cytotoxicity problems associated to low crosslinking degrees, the concentration of the photoinitiator being a key factor influencing photopolymerization efficiency. When the photoinitiator concentration was too low, the energy to trigger the polymerization reaction was insufficient, leading to unpolymerized monomers, which can have toxic effects. Conversely, if the concentration was too high, excessive light absorption caused rapid polymerization of the surface layers, resulting in incomplete polymerization [73,99,131]. This phenomenon has been already addressed previously. Lee et al. demonstrated the existence of a critical photoinitiator concentration for which the curing depth is maximized for photopolymerization reactions. They reported experimental evidence that there must clearly be an “optimal” concentration to maximize the curing of the gel. In fact, when the photoinitiator concentration is low, just a small fraction of the photons is absorbed, resulting in few free radicals to start the reaction which are unable to form a gel. However, when the concentration of photoinitiator increases, the resulting radical initiation increases which results in higher double-bond conversion. At high photoinitiator concentrations, the photon absorption is so intense that light penetration diminishes, remaining confined near the surface of the resin. This fact induces the formation of a tightly cross-linked, thin layers [89]. To add up, this phenomenon is further aggravated by the presence of ceramic particles in the resin, which absorb part of the light radiation.

The printed parts must be thoroughly rinsed and ultrasonically cleaned, to wash out unpolymerized monomers or loose particles. In some cases, additional curing of the printed structure is carried out to completely crosslink any unpolymerized residue [86,98,187,188]. Moreover, in the case of reactive ceramics that are able to undergo a self-hardening process by a cement-like reaction, a subsequent process can be applied to transform the ceramic phase, as reported by Oliver-Urrutia et al. for an α-TCP-loaded resin [189]. A detailed summary of resin formulations and processing parameters reported in the literature for the fabrication of CaP/polymer composite scaffolds by VP are summarized in Table 3. Abbreviations can be found in footnotes bellow the table or in Table S1 (supplementary information).

Table 3.

Resin formulation, rheological properties and printing parameters for vat photopolymerization printing of calcium phosphate composite scaffolds. Acronyms (LSS: laser spot size, E: energy, d: dose, I: intensity, P: power, LH: layer height, λ: curing wavelength).

| CaP | Loading | Slurry composition | VP printing | Slurry's viscosity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | 40 wt% | Monomer: TATO alkene + TATO thiol | SLA (Peopoly Moai 130) | _ | [87] |

| Initiator: 0.68 wt% TPO | LH: 60 μm | ||||

| Absorbers: Sultan I + PYG | λ: 400 nm | ||||

| Diluents: TMPMP, PETMP, ETTMP | |||||

| 10-20 wt% | Monomer: 60 wt% PEGDA (Mn = 700) | SLA (custom solid-oodle) | _ | [190] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% BAPO | LH: 400 μm | ||||

| Diluent: PEG (Mw = 300) | λ: 355 nm | ||||

| I: 40 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 55 wt% | Monomer: OL-MA (Mn 1420 g/mol) + TEGDMA (1:1) | SLA | _ | [187] | |

| Initiator: Irgacure® 819 (BAPO) | LSS: 100 μm | ||||

| λ: 355 nm | |||||

| 40 wt% | Monomer: 60 wt% PEGDA (Mn 700) | SLA | 5 Pa s at 100 Hza | [131] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% Irgacure® 2959 | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| λ: 355 nm | |||||

| P: 70 mW | |||||

| 8 wt% | Commercial: acrylic-based urethane methacrylated resin (Novafab Powerdent Temp) | DLP (Novafab Vega) | _ | [188] | |

| λ: 405 nm | |||||

| I: 2.3 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 5.2, 16.7 wt% | Monomer: 60–47.4-25.1 wt% PTMC-MA | SLA | 57.5–71.9 mPa s | [65] | |

| Initiator: 5 wt% TPO-L | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| Absorber: 0.15–0.12-0.08 wt% Orasol Orange G | |||||

| Diluent: 40-47.4-58.2 wt% Propylene carbonate | |||||

| 20, 40 wt% | Monomer: PTMC-MA | SLA (Envisiontec Perfactory III) | _ | [[66], [67], [68]] | |

| Initiator: 5 wt% TPO-L | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| Absorber: (0.15–0.1-0.08 wt%) Orange G | I: 1.80 mW/cm2 | ||||

| Diluent: propylene carbonate | |||||

| 7 wt% | Monomer: PPF (70 %) | MSTL (SLA) (custom) | _ | [191] | |

| Initiator: 1 wt% Irgacure® 819 (BAPO) | LH: 215 μm | ||||

| Diluent: DEF (30 %) | λ: 375 nm | ||||

| P: 310 mW | |||||

| 10 vol% | Monomer: PEGDA (Mw250) + AESO (1:1) | mSLA (Anycubic Photon) | 0.2–0.49 Pa s at 50 Hz | [94] | |

| Initiator: 1 wt% Irgacure® 819 (BAPO) | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| 40 wt% | Monomer: OCM-2P | SLA (LS-250) | 260 cSt | [192] | |

| Initiator: Irgacure® 671P | LH: 200 μm | ||||

| Absorber: 0.02 wt% bis-(5-methyl-3-tert-butyl-2-oxyphenyl)-methane | |||||

| Dispersant: PAA | |||||

| 20 wt% | Monomer: PDLLA | SLA (Envisiontec Perfactory Mini) | 4–7 Pa s | [193,194] | |

| Initiator: 4 wt% Lucirin®-TPO-L | LH: 25 μm | ||||

| Absorber: 0.2 wt% tocopherol inhibitor + 0.15 wt% Orange Orasol G | λ: 400–550 nm | ||||

| Diluent: 50 wt% NMP | I: 17 mW/cm2 | ||||

| 55, 75 wt% | Monomer: PLA-MA | SLA (custom) | _ | [195] | |

| Initiator: ethylene glycoxide | LSS: 70 μm | ||||

| Diluent: TEGDMA | λ: 355 nm | ||||

| P: 1.5 mW | |||||

| 10 wt% | Monomer: PEDGA (60 or 40 %) RGD modified | SLA | _ | [196] | |

| Initiator: Not specified | LH: 400 μm | ||||

| I: 25–300 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 10 w/v% | Monomer: 15 w/v% PEGDA + 10 w/v% GelMA + PLGA NPs with TGFb1 | SLA (not specified) | _ | [71] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 w/v% Irgacure® 2959 | |||||

| 10 wt% | Monomer: 10–15 % GelMA | SLA | _ | [70] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 % Irgacure® 2959 | LH: 200 μm | ||||

| E: 20 μJ at 15 kHz | |||||

| 2, 5, 10 w/w % | Monomer: 60 % PEGDA (Mn 700) | SLA (Printrbot®) | _ | [197,198] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 % Irgacure® 819 (BAPO) | LSS 190 μm | ||||

| Diluent: 40 % PEG | λ: 355 nm | ||||

| Energy: 20 μJ at 15 kHz | |||||

| 30 w/v% | Monomers: GelMA + SilMA (1:1) | DLP (BP600, EFL) | _ | [74] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 w/v% LAP | I: 15 mW/cm2 | ||||

| Absorber: 0.05 w/v% Tartrazine | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| 10-50 wt% | Monomers: 30 wt% GelMA | SLA (custom) | [73] | ||

| Initiator: 4 % (w/v) Irgacure® 2959 | P: 180–200 mW | ||||

| LH: 100 μm | |||||

| 10-30 wt% | Monomer: mAESO + PEGDA (1:1) | mSLA (Sonic XL 4K, Phrozen) | _ | [199] | |

| Initiator: 1 % Irgacure® 819 | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| 5.5 wt% | Monomer: GelMA + AlgMA | DLP (EFL-BP-8601) | _ | [75] | |

| Initiator: LAP | I: 14 mW/cm2 | ||||

| LH: 25 μm | |||||

| 5-10 wt% | Monomer: CSMA-2 | DLP (Nobel Superfine, XYZ) | 0.3–0.55 Pa s | [77,78] | |

| Initiator: 2 wt% BAPO | λ: 405 nm | ||||

| I: 5.3–6 mW/cm2 | |||||

| HA + CPP | 5 + 5 wt% | Commercial: Soybean oil-based commercial resin (Anycubic Co.) | SLA (Anycubic Photon S) | 0.501–0.839 Pa s | [200] |

| λ: 355–410 nm | |||||

| HA + Sr | 32.6–38 wt% | Monomers: 10 w/v% GelMA | DLP | [72] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 wt% LAP | λ: 405 nm | ||||

| I: 12 mW/cm2 | |||||

| HA + SWCNT | 12.5 mg/mLa + 0, 1, 2 wt% | Commercial: Dental resin, DITAX | DLP | _ | [127] |

| Dispersant: TEA | LH: 20 μm | ||||

| λ: 360–410 nm | |||||

| β-TCP | 32, 51, 60 wt% | Monomer: PTMC-MA | DLP (Envisiontec Perfactory III mini SXGA+) | _ | [69] |

| Initiator: 5 wt% TPO-L | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| Absorber: Orasol Orange G | λ: 400–550 nm | ||||

| Dispersant: Propylene carbonate | I: 7 mW/cm2 | ||||

| _ | Monomer: GelMA + HyAc-MA | DLP (LumenX, Celllink) | [82] | ||

| Initiator: LAP | LH: 50 μm | ||||

| Absorber: R1800, benzophenone-9 | λ: 400–550 nm | ||||

| I: 7 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 20 vol% | Monomer: 40 % PEGDA (Mw = 400) | DLP (MMSL) (Custom) | _ | [201] | |

| Initiators: 0,25 wt% DAROCUR-1173 + DAROCUR- TPO (2:3) | LH: 100 μm | ||||

| Dispersant: Quaternary ammonium | λ: 400–410 nm | ||||

| I: 14,98 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 5 mg/ml | 30 w/v% PEGDA (Mn 700) + Chitosan (4 mg/ml) | SLA | 100–200 mPa s | [202] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 w/v% Irgacure® 2959 | λ: 365 nm | ||||

| I: 1 mW/cm2 | |||||

| 10 % | Commercial PLA resin (Yisheng New Material) | LCD-DLP (Chuangxiang LD-002R | 200 mPa s | [203] | |

| LH: 50 μm | |||||

| _ | Monomer: PEGDA 508 | SLA (Custom) | _ | [42] | |

| Initiator: 0.5 % Irgacure® 2959 | P: 100 mW | ||||

| BCP | 22.5, 40 wt% | Monomer: 56 wt% PLLA + 20 wt% TMPTMA (crosslinker) | DLP (Kavosh economy) | 0.1–5a Pa s (<5 Pa s) | [86] |