Abstract

Fluid administration is a key component in the management of acute ischemic stroke (AIS). However, the effects of different sodium concentrations in resuscitation fluids, particularly on distal organ function, remain controversial. This study compared the impact of four commonly used fluids—0.9% isotonic saline (ISO), 0.45% hypotonic saline (HYPO), 1.5% hypertonic saline (HYPER), and 5% glucose (GLUCO)—on perilesional brain tissue, lungs, and kidneys following AIS. AIS was induced in 28 male Wistar rats. Three hours after stroke induction, animals were randomized to receive one of the four fluids. In the brain, the ISO group showed significantly higher expression of versican and hyaluronan compared to the HYPER group (p = 0.022 and p = 0.018, respectively). Conversely, the HYPER group exhibited significantly elevated levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) compared to the GLUCO group (p = 0.01, p = 0.02, and p = 0.006, respectively). In the lungs, the ISO group demonstrated less alveolar collapse and pulmonary edema compared to the HYPER and HYPO groups (p = 0.01 and p = 0.007, respectively). In the kidneys, both the ISO and HYPO groups showed significantly less brush-border injury than the HYPER group (p = 0.007 and p = 0.032, respectively). Furthermore, blood chloride levels declined over time in the ISO group compared to the others. In conclusion, isotonic fluid administration resulted in the least amount of injury to the brain, lungs, and kidneys in this experimental model of AIS, supporting its use as a preferred resuscitation strategy in the acute phase.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-12491-9.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, Inflammation, Brain damage, Sodium concentration, Fluids

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Physiology

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is a leading cause of long-term disability and mortality worldwide1–3. Early diagnosis and adequate treatment are critical to improving outcomes4–7. Intravenous fluid therapy is commonly recommended for resuscitation, volume replacement, and maintenance in AIS management8. In this context, isotonic saline (0.9% NaCl) is the most frequently used solution in clinical practice9; however, its use has been associated with complications such as hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia10–13.

Hypotonic fluids are generally excreted more efficiently by the kidneys than isotonic solutions14,15 resulting in less sodium and water retention and a more negative fluid balance. These properties suggest reno-protective effects of hypotonic fluids in certain contexts16–19. Nevertheless, their use is not without risks: hypotonic solutions have been linked to hyponatremia, inflammation, and edema in distal organs20,21.

Hypertonic saline, on the other hand, is widely used to reduce cerebral edema and decrease intracranial pressure22. Nonetheless, it carries the risk of inducing severe hypernatremia, increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from epithelial cells23 and complications such as urinary tract infections and renal dysfunction, which may contribute to increased mortality24–28.

Despite the widespread use of these fluids, the impact of different sodium concentrations on the brain and distant organs after AIS remains poorly understood29. Fluids, much like medications, must be chosen with care. Drawing a parallel with antibiotic stewardship, there is a growing need to apply the principles of the “4 Ds”—drug, dose, duration, and de-escalation—to fluid therapy as well30.

In this study, we compared the effects of intravenous fluids with varying sodium concentrations, namely 0.9% isotonic saline (ISO), 0.45% hypotonic saline (HYPO), 1.5% hypertonic saline (HYPER), and 5% glucose (GLUCO) on perilesional brain tissue, lungs, and kidneys in an experimental model of AIS. We hypothesized that hypotonic solutions, when administered within the first 3 h following AIS, would result in less brain injury and offer protective effects on the lungs and kidneys, compared to isotonic and hypertonic saline or glucose-based fluids.

Results

All animals successfully completed the experiment. On average, each animal received a total of 5.4 ± 0.5 mL of fluids, with group-specific volumes as follows: ISO: 5.4 ± 1.4 mL, HYPER: 5.7 ± 1.1 mL, HYPO: 4.5 ± 2.4 mL, and GLUCO: 5.8 ± 0.7 mL. The mean volume of sedatives and neuromuscular blockers administered was 2.7 ± 0.3 mL, while the average volume of the study fluids was 2.7 ± 0.2 mL.

Fluid boluses were administered when mean arterial pressure (MAP) dropped below 60 mmHg, with an average bolus volume of 1.3 ± 0.6 mL. Group-specific bolus volumes were ISO: 1.1 ± 0.5 mL, HYPO: 1.3 ± 0.6 mL, HYPER: 1.1 ± 0.8 mL, and GLUCO: 1.5 ± 0.5 mL. MAP demonstrated a significant time-dependent increase across all groups (p = 0.003), indicating a gradual hemodynamic improvement during the experimental period.

Brain

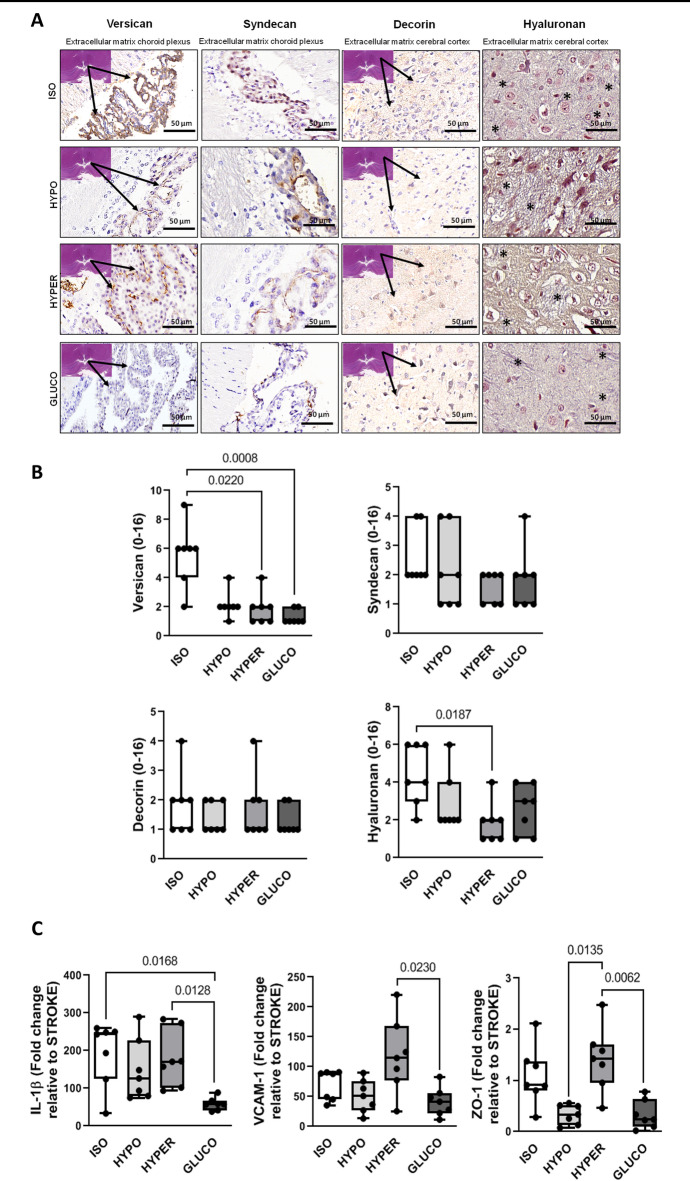

Representative photomicrographs of brain parenchyma are shown in Fig. 1A. Versican levels were significantly higher in the ISO group compared to the HYPER and GLUCO groups (p = 0.0220 and p = 0.0008, respectively). Additionally, hyaluronan expression was elevated in the ISO group compared to the HYPER group (p = 0.0187). In contrast, decorin and syndecan levels did not differ significantly among the groups (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

A: Representative photomicrographs of the cerebral cortex and choroid plexus. Asterisks indicate the extracellular matrix organization pattern stained in blue (hyaluronan) within the cerebral cortex. B: Quantification of versican, syndecan, decorin, and hyaluronan expression. C: mRNA expression of interleukin (IL)-1β, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) in brain tissue. Groups: ISO (isotonic saline), HYPO (hypotonic saline), HYPER (hypertonic saline), GLUCO (5% glucose). Box plots show median and interquartile range (n = 7 per group). Statistical comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05).

In brain tissue, mRNA expression of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) was significantly increased in the HYPER group compared to the GLUCO group (p = 0.012), and in the ISO group compared to the GLUCO group (p = 0.016). VCAM-1 expression was also higher in the HYPER group relative to the GLUCO group (p = 0.023). Furthermore, zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) expression was elevated in the HYPER group compared to both the GLUCO (p = 0.006) and HYPO (p = 0.013) groups (Fig. 1C).

Lungs

No significant differences were observed in blood gas analysis among the groups or overtime (Supplementary Table S1). Airway peak pressure, plateau pressure, and driving pressure increased significantly over time (p = 0.012, p = 0.010, and p = 0.006, respectively), while tidal volume (VT) decreased (p = 0.026). Mechanical power did not differ significantly between groups or overtime (Supplementary Table S2).

Representative photomicrographs of lung parenchyma at intermediate and high magnification are shown in Fig. 2A. The ISO and GLUCO groups preserved normal lung histoarchitecture, with only minor alveolar collapse and edema, in contrast to the more pronounced alterations observed in the HYPER and HYPO groups. Quantitative analysis confirmed these findings: HYPER vs. ISO, p = 0.014; HYPER vs. GLUCO, p = 0.001; HYPO vs. GLUCO, p = 0.008; HYPER vs. HYPO, p = 0.002; ISO vs. HYPO, p = 0.007 (Fig. 2B). In lung tissue, IL-1β expression was significantly lower in the ISO group compared to the HYPO group (p = 0.020). Additionally, aquaporin-5 (AQP-5) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expressions were both higher in the ISO group compared to the GLUCO group (p = 0.010 and p = 0.015, respectively) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

A: Representative photomicrographs of lung parenchyma. Asterisks indicate perivascular edema; arrows indicate alveolar edema. Br: bronchiole; Ve: vessel; Alv: alveoli. B: Quantification of alveolar collapse and pulmonary edema. C: mRNA expression of IL-1β, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and aquaporin-5 (AQP-5) in lung tissue. Groups: ISO, HYPO, HYPER, and GLUCO as defined in Fig. 1. Box plots represent median and interquartile range (n = 7 per group). Statistical comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05).

Kidneys

Chloride concentrations in blood samples decreased by 27.6% over time in the ISO group, significantly more than in the HYPO, HYPER, and GLUCO groups (p = 0.031, p = 0.001, and p = 0.021, respectively) (Fig. 3). Potassium, sodium, and calcium levels remained stable throughout the experiment.

Fig. 3.

Percent change in serum concentrations of sodium, chloride, potassium, and calcium from INITIAL (post-randomization) to FINAL (end of experiment).

Groups: ISO, HYPO, HYPER, and GLUCO. Box plots represent median and interquartile range (n = 7 per group). Statistical comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05).

At the final time point, osmolality, urea, creatinine, and lactate levels were comparable across all groups. However, urine sodium concentrations were significantly lower in the HYPO and GLUCO groups than in the HYPER and ISO groups (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons). Similarly, plasma sodium levels were lower in the HYPO and GLUCO groups compared to the HYPER group (p = 0.019 and p = 0.043, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Biochemical analysis of urine and plasma.

| ISO | HYPO | HYPER | GLUCO | ISO | HYPO | HYPER | GLUCO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Sodium (mmol/L) | 223 ± 51 | 23 ± 12*# | 272 ± 51 | 25 ± 15*# | - | *, p < 0.001 #, p < 0.001 | - | *, p < 0.001 #, p < 0.001 |

| Osmolality (Osm/L) | 802 ± 79 | 1002 ± 196# | 675 ± 111 | 842 ± 228 | - | #, p = 0.002 | - | - | |

| Protein (mg/dL) | 140 ± 71 | 148 ± 46 | 185 ± 103 | 152 ± 62 | - | - | - | - | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 58 ± 16** | 105 ± 19 | 49 ± 18** | 57 ± 14** | **, p = 0.004 | - | **, p < 0.001 | **, p = 0.003 | |

| UPCr (A.U.) | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.3# | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | - | #, p < 0.001 | - | - | |

| Plasma | Sodium (mmol/L) | 151 ± 3 | 144 ± 5# | 152 ± 5 | 145 ± 6# | - | #, p = 0.019 | - | #, p = 0.043 |

| Osmolality (Osm/L) | 372 ± 68 | 351 ± 27 | 363 ± 35 | 355 ± 36 | - | - | - | - | |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 97 ± 39 | 86 ± 27 | 99 ± 17 | 89 ± 13 | - | - | - | - | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Lactate (mg/dL) | 15 ± 6 | 17 ± 6 | 12 ± 4 | 21 ± 16 | - | - | - | - |

All values are given as mean ± standard deviation of 7 animals per group. ISO: isotonic saline; HYPO: hypotonic saline; HYPER: hypertonic saline; GLUCO: 5% glucose; UPCr: urine protein/creatinine ratio. Comparisons performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05). *vs. ISO; **vs. HYPO; #vs. HYPER.

The HYPO group also exhibited: higher urine osmolality than the HYPER group (p = 0.002), and a lower urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCr) (p = 0.001).

Conversely, urine creatinine concentrations were higher in the HYPO group compared to the ISO, HYPER, and GLUCO groups (p = 0.004, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.003, respectively). Urine protein levels did not differ significantly among groups (Table 1).

Representative photomicrographs of kidney tissue are shown in Fig. 4A. The HYPER group showed greater brush border injury compared to the ISO and HYPO groups (p = 0.007 and p = 0.032, respectively), while renal edema was similar across all groups (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A: Representative photomicrographs of kidney tissue. Asterisks denote brush border injury. B: Quantification of renal edema and brush border injury. C: mRNA expression of IL-1β, kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in kidney tissue. Groups: ISO, HYPO, HYPER, and GLUCO. Box plots show median and interquartile range (n = 7 per group). Statistical comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05).

In kidney tissue, mRNA expression of IL-1β and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) did not differ significantly between groups. However, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) expression was significantly higher in the GLUCO group compared to the HYPO group (p = 0.007) (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

In this animal model of AIS, our study identified several key findings: (1) Administration of isotonic saline was associated with preserved brain and kidney histoarchitecture, reduced lung injury (i.e., edema and alveolar collapse), and a time-dependent reduction in plasma chloride levels, not observed with hypotonic saline, hypertonic saline, or glucose; (2) Animals receiving 5% glucose alone exhibited increased NGAL expression in the kidneys compared to those receiving hypotonic saline, without significant changes in brain or lung injury parameters, suggesting isolated kidney damage; (3) The hypotonic saline group demonstrated increased lung edema, urine creatinine, and osmolality, indicating greater lung and kidney injury; and (4) The hypertonic saline group showed evidence of widespread injury, including elevated markers of brain inflammation, disrupted cerebral histoarchitecture, increased alveolar collapse, renal brush border damage, and higher urinary UPCr and osmolality. Thus, our initial hypothesis was based on the potential neuroprotective effects of hypotonic fluids. However, our findings indicate that isotonic fluids more effectively preserve osmotic balance, intravascular volume, and perfusion pressure without exacerbating cerebral edema. In addition, isotonic fluid administration was associated with reduced injury to the renal brush border. These results suggest that maintaining fluid tonicity is essential and should not be altered after stroke.

We employed a focal ischemia model induced by thermocoagulation of pial vessels overlying the primary sensorimotor cortices—an approach that more closely mimics clinical stroke pathology than global ischemia models. Focal ischemia accounts for over 90% of strokes worldwide and is associated with secondary injury to distant organs, such as the lungs and kidneys. Previous studies using this model have documented cerebral inflammation as well as histological lung injury, supporting its translational relevance31,32.

According to current guidelines29 fluid therapy is a cornerstone of stroke management within the first few hours, serving to optimize perfusion, maintain hemodynamic stability, and mitigate complications such as cerebral edema and delayed ischemia. However, the optimal fluid composition remains controversial. While isotonic crystalloids are widely used due to their neutrality and availability9 some studies have suggested that hypotonic solutions may offer renoprotective benefits via enhanced excretion33 whereas hypertonic solutions can reduce cerebral edema but at the cost of adverse renal and systemic effects22,24,28. To date, limited evidence exists on how fluid tonicity influences injury in distal organs following stroke, a gap that our study helps to address.

Hyperosmolar environments have been shown to activate systemic inflammatory responses, likely due to cellular stress induced by osmotic imbalance and changes in cell volume. Conditions such as Sjögren’s syndrome and the pro-inflammatory effects of high-salt diets further support this concept34. Our findings extend this understanding by demonstrating that hypertonic saline, while used to lower intracranial pressure, may exacerbate injury in non-neural organs under stroke conditions35,36.

During the experiment, mean arterial pressure increased over time in all groups, consistent with the clinical goal of maintaining cerebral perfusion post-stroke. A blood pressure threshold of 180/105 mmHg is typically recommended in the acute phase to support the ischemic penumbra29. The fluid administration rate in our model followed established standards for small rodents and did not appear to adversely affect hemodynamic status36,37. The need for larger volumes with crystalloids is consistent with their distribution across intra- and extracellular compartments, unlike colloids, which remain primarily intravascular38,39.

In the brain, the observed upregulation of versican and hyaluronan in the ISO group suggests preservation of extracellular matrix (ECM) integrity40,41 which is essential for maintaining neural architecture and modulating post-ischemic repair. These proteoglycans are known to contribute to structural support, cell signaling, and repair mechanisms following injury. Decorin and syndecan, also ECM components42,43 were not significantly altered among groups, suggesting differential responses to fluid tonicity. While our semiquantitative histological scoring system effectively detected intergroup differences in injury severity, future studies will incorporate quantitative assessments of lesion area using morphometric or imaging-based techniques to complement and validate these findings.

Elevated brain IL-1β levels observed across most groups are consistent with a shared inflammatory response following cerebral ischemia, reflecting microglial activation and neuroinflammation. However, it is important to recognize that IL-1β, as a pro-inflammatory cytokine, exhibits complex and context-dependent roles that may vary during different injury phases, potentially contributing to both injury propagation and reparative processes44–46. Similarly, increased expression of VCAM-1 and ZO-143,44, particularly prominent in the hypertonic saline group—likely indicates endothelial activation and dynamic modulation of blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. VCAM-1 facilitates leukocyte adhesion and transmigration, marking endothelial inflammation, while ZO-1 is a critical tight junction protein whose altered expression can reflect either BBB disruption or compensatory remodeling. These molecular changes should be interpreted within the broader context of histological findings and the overall pathophysiological milieu, as their biological significance is multifaceted and may depend on the temporal stage of ischemic injury and treatment effects. Accordingly, our data suggests that hypertonic saline administration may intensify endothelial activation and barrier perturbations, contributing to secondary brain injury, although these markers alone cannot fully delineate the extent or nature of barrier dysfunction.

In the lungs, the progressive increase in airway pressures and decline in tidal volume over time is consistent with evolving alveolar collapse and edema42. The hypotonic group demonstrated more pronounced pulmonary inflammation, consistent with previous reports linking hyponatremia to lung injury43. While hypertonic saline may initially reduce pulmonary edema in experimental models of ischemia-reperfusion47. Erdogan et al. (2021) investigated the impact of fluid resuscitation on acute lung injury in a rat sepsis model and demonstrated that the type and volume of administered fluids significantly influenced pulmonary inflammation and edema48. Their results highlighted that inappropriate fluid management could exacerbate lung injury by increasing pulmonary vascular permeability and inflammatory responses. Similarly, in our ischemic stroke model, we observed that hypotonic and hypertonic saline administration led to more pronounced lung injury compared to isotonic saline, as evidenced by increased edema and alveolar collapse. These concordant findings reinforce the notion that fluid composition and tonicity are pivotal determinants of lung tissue response in critical illness and underscore the necessity of carefully selecting fluid therapy to minimize secondary organ damage. Incorporating the insights from Erdogan et al. thus strengthens the translational relevance of our study, suggesting that cautious fluid management may be essential not only in sepsis but also in ischemic stroke to prevent exacerbation of lung injury.

In the kidneys, precise sodium regulation is vital49. Plasma chloride reduction occurred only in the isotonic group, potentially offering protection against hyperchloremic acidosis and associated renal dysfunction50. Urinary sodium levels were lower in the hypotonic and glucose groups, whereas NGAL expression—an early marker of tubular injury—was highest in the glucose group, indicating subclinical nephrotoxicity51. These findings underscore that both excess and absence of sodium chloride can be detrimental to renal health under ischemic conditions.

This study has several limitations. First, neurofunctional assessments were not feasible due to the experimental design, although all animals regained consciousness after stroke induction. In clinical settings, functional outcomes are the primary determinant of stroke prognosis and therapeutic success. While our experimental design prioritized early multi-organ evaluation (brain, lung, and kidney) with invasive monitoring and controlled fluid administration, this approach precluded longitudinal follow-up and behavioral testing. Nonetheless, all animals regained consciousness after stroke induction, and the focal ischemia model used here is well characterized and known to produce consistent, functionally relevant cortical injuries in prior studies. To strengthen translational relevance, future investigations should incorporate validated neurobehavioral assessments—such as neurological deficit scoring, limb-use asymmetry, gait analysis, or sensorimotor testing—alongside histological and molecular endpoints. This would allow a more comprehensive evaluation of how fluid composition influences both structural and functional recovery after AIS. Second, only one stroke model was used, limiting extrapolation to other stroke types or severities. Third, all animals were young, healthy, and male, which may not reflect the heterogeneity of clinical stroke populations52. Fourth, the absence of bladder catheterization prevented measurement of urine output. This decision was made to minimize additional procedural stress and confounding factors in this small animal model. Nevertheless, we assessed renal injury using complementary markers such as histological analysis of renal tissue, immunohistochemical expression of NGAL (a sensitive early marker of tubular injury), and urinary creatinine and protein-to-creatinine ratio, which provided indirect evidence of renal impact by different fluid therapies. Future studies will incorporate direct urine output and clearance measurements to enhance the assessment of renal function and improve the translational relevance of these findings. Fifth, the sample size was modest, and a crossover design was not applicable. Sixth, interventions during the experiment (e.g., fluid boluses for hypotension, sedation boluses for hypertension) were standardized across groups, and all animals received equal total fluid volumes. Although hypotonic fluids are not typically used for resuscitation, they were included to isolate the effects of sodium concentration and minimize confounders. Finally, we acknowledge that the absence of a non-stroke or sham-operated control group limits the interpretation of baseline histological and biochemical parameters. The inclusion of such a group would have enabled clearer differentiation between changes attributable to stroke and those arising from fluid composition or systemic responses. However, our primary objective was to compare the effects of different fluid regimens within the context of cerebral ischemia, using a well-established focal stroke model known to elicit consistent patterns of neuroinflammation and distant organ injury31. All animals underwent identical surgical and anesthetic protocols, ensuring comparability across groups. Additionally, historical data from our laboratory using the same model has consistently demonstrated characteristic patterns of cerebral and systemic injury in the absence of fluid intervention, providing a reliable reference for interpretation53,54. Nevertheless, we recognize that future studies should incorporate non-stroke or sham-operated groups to more precisely delineate the contributions of stroke versus fluid-related effects on tissue injury and biomarker expression. This would strengthen mechanistic insight and enhance translational relevance.

Conclusion

These findings support the use of isotonic saline as the most balanced and organ-protective fluid in the early management of acute ischemic stroke. Isotonic solutions were associated with better preservation of cerebral, pulmonary, and renal integrity compared to hypotonic, hypertonic, or glucose-based fluids. While isotonic crystalloids remain the mainstay of clinical practice due to their availability and cost-effectiveness52 our results suggest they may also offer the most favorable multiorgan profile. Further research is warranted to determine optimal fluid strategies tailored to both cerebral and systemic outcomes in patients with acute stroke.

Methods

Study approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CEUA CCS-013/21) of the Health Sciences Centre, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brazil. All procedures adhered to the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care and the U.S. National Academy of Sciences Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The study followed the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research55. Animals were housed under controlled temperature (23 °C) and a 12:12 h light–dark cycle, with free access to food and water. No acclimatization period was applied.

Animal Preparation

Thirty-three male Wistar rats (mean body weight ± SD: 390 ± 4 g) were purchased from the UFRJ animal facility. Anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of xylazine (2.5 mg/kg), ketamine (75 mg/kg), and diazepam (10 mg/kg), and the animals were positioned in a stereotactic frame. Acute ischemic stroke was induced by thermocoagulation of pial vessels over the somatosensory, motor, and primary sensorimotor cortices, as previously described31,32,54. Surgery began when there was no response to a painful stimulus56. Following a midline skin incision, a craniotomy was performed, exposing the left frontoparietal cortex (+ 2 to − 6 mm AP to bregma; +2 to + 4 mm lateral). A hot probe (300 °C) was applied near the surface to coagulate pial vessels without contacting the parenchyma47. Successful ischemia was confirmed macroscopically by vessel color change (red to black) within 5 min. All stroke procedures were performed by a single experienced investigator (C.M.B.) to reduce inter-operator variability. At the end of surgery, tramadol (10 mL/kg) was administered subcutaneously for analgesia.

Experimental protocol

Three hours after stroke induction, rats were alert, ambulating, and free of respiratory distress or pain. Premedication was administered with i.p. midazolam (1–2 mg/kg), followed by i.p. ketamine (100 mg/kg). A 24G catheter (Jelco, Becton Dickinson, USA) was inserted into the tail vein for anesthesia maintenance (midazolam 2 mg/kg/h and ketamine 50 mg/kg/h) and fluid infusion.

Upon reaching surgical anesthesia, a tracheostomy was performed under local lidocaine infiltration (1% solution, 1 mL), and animals were mechanically ventilated (Servo-I; Getinge, Sweden) in volume-controlled mode with the following settings: tidal volume (VT) = 6 mL/kg, respiratory rate (RR) = 80 breaths/min, FiO₂ = 0.4, and PEEP = 3 cmH₂O. A catheter (20G, Arrow International, USA) was placed in the right internal carotid artery to enable continuous mean arterial pressure (MAP) monitoring (LifeWindow 6000 V; Digicare, USA) and blood sampling. Neuromuscular blockade was achieved with intravenous vecuronium bromide (2 mg/kg).

Rats were randomized into four groups, defined by the type of infused fluid. All solutions contained 5% glucose, with sodium chloride adjusted as follows: isotonic (ISO; 0.9% NaCl, Na⁺ = 154 mEq/L), hypotonic (HYPO; 0.45% NaCl, Na⁺ = 77 mEq/L), hypertonic (HYPER; 1.5% NaCl, Na⁺ = 256 mEq/L), and glucose-only (GLUCO; 5% glucose). The assigned fluid was infused at 2 mL/kg/h for 120 minutes21,22. In cases of MAP < 60 mmHg, a fluid bolus of the same solution was administered. A fifth non-ventilated, non-resuscitated stroke group was included for molecular analyses.

MAP and rectal temperature were continuously monitored. Anesthesia was titrated based on reflex testing and MAP trends48. At the end of the experiment (FINAL time point), after assessment of respiratory mechanics, animals received intravenous heparin (1,000 IU), followed 2 min later by sodium thiopental (100 mg/kg). Euthanasia was performed via laparotomy, aortic transection, and exsanguination. Brain, lung (at end-expiratory pressure), and kidney tissues were collected for histologic and molecular analyses. Urine (from bladder puncture) and plasma were stored for biochemical assays.

Data acquisition and processing

A pneumotachograph (ID: 1.5 mm; length: 4.2 cm) was attached to the tracheal cannula for airflow (Vʹ) measurements57. The pressure gradient across the pneumotachograph was recorded using a SCIREQ UT-PDP-02 pressure transducer (SCIREQ, Canada). Respiratory variables were recorded using LabVIEW (National Instruments, USA). VT was calculated by digital integration of the flow signal.

Inspiratory pauses of 5 s allowed measurement of peak and plateau airway pressures, and driving pressure (plateau − PEEP). Mechanical power was calculated as:

mechanical power = 0.098 × RR × VT × [respiratory system peak pressure − (respiratory system driving pressure)/2]. Mechanical variables were analyzed offline in MATLAB (R2007a; MathWorks, USA) at INITIAL and FINAL time points.

Arterial blood samples (300 µL) were collected at INITIAL and FINAL for blood gas and electrolyte analysis (ABL80 FLEX, Radiometer, Denmark), including arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2, 80 to 100 mmHg), partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2, 35 to 45 mmHg), arterial pH (pHa, 7.35 to 7.45), bicarbonate (HCO3−, 22 to 26 mEq/L), and electrolytes such as sodium (Na+, 135 to 145 mmol/L), potassium (K+, 3.6 to 5.5 mmol/L), calcium (Ca2+, 2.2 to 2.67 mmol/L) and chloride (Cl−, 97 to 105 mmol/L). No acid-base or electrolyte corrections were performed during the experiment.

Histology

In brain sections, versican, syndecan, decorin, and hyaluronan expression were scored based on intensity (0–4) and extent (0–4), with final scores ranging from 0 to 16. Scoring criteria reflect neuronal loss, edema, gliosis, and inflammation.

In lungs, edema and alveolar collapse were assessed using a validated weighted scoring system58. Intensity (0–4) and extent (0–4) scores were multiplied to yield final scores (0–16)31,54,59.

Kidney injury was evaluated by tubular cell damage (brush border loss, cell swelling, interstitial edema) scored from 0 to 4 according to the percentage of tissue involved60.

All histological evaluations were performed by a blinded investigator (V.L.C.)61.

Molecular biology

Central slices of the peri-lesional brain, right lung, and kidney were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C. Total RNA was extracted, and gene expression was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. In the brain and lung, mRNA levels of IL-1β and VCAM-1 were measured; in the kidney, IL-1β, KIM-1, and NGAL expression were assessed. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Gene expression was normalized to the 36B4 housekeeping gene62 and fold change was calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method63 relative to the non-ventilated control group.

Detailed biochemical and histological methods are provided in Supplementary Information.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was determined based on prior data showing IL-1β increases with osmolarity, with an effect size of d = 1.7023. Using α = 0.05 and power = 0.8, seven animals per group were required (G*Power v3.1.9.2; University of Düsseldorf, Germany)64.

Parametric data are expressed as mean ± SD, and nonparametric data as median (IQR). Two-way ANOVA with Holm–Šidák correction was used for repeated measures (INITIAL vs. FINAL). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was applied for postmortem parametric data. Nonparametric variables were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism v6.07 (GraphPad Software, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andre Benedito da Silva, BSc, for animal care; Arlete Fernandes, BSc, and Camila Machado, PhD student, for microscopy assistance; Maíra Rezende Lima, MSc, for molecular biology analysis; and Moira Elizabeth Schöttler (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and Filippe Vasconcellos (São Paulo, Brazil) for language editing.

Author contributions

C.M.B — study concept and design; conduct of experiments; interpreting and analyzing data; manuscript writing, review and editing. A.L.V — study concept and design; conduct of experiments; interpreting and analyzing data; manuscript review and editing. D.B.P; P.H.L.C.; C.C.N; V.L.C; D.B; C.R; M.L.N.G.M — interpreting and analyzing data; manuscript review and editing. P.P — interpreting and analyzing data. P.R.M.R; P.L.S; C.S.S — study concept and design; interpreting and analyzing data; manuscript review and editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq 2019/12151-0), the Rio de Janeiro State Research Foundation (FAPERJ E-26/202.766/2018, E-26/010.001488/2019), the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP 2018/20493-6), the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES 88881.371450/2019-01), and the Department of Science and Technology – Brazilian Ministry of Health (DECIT/MS).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hankey, G. J. Stroke in young adults: implications of the long-term prognosis. Jama309, 1171–1172. 10.1001/jama.2013.2319 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang, Q. et al. Vital signs: recent trends in stroke death Rates - United states, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep.66, 933–939. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6635e1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herpich, F. & Rincon, F. Management of acute ischemic stroke. Crit. Care Med.48, 1654–1663. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004597 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacke, W. et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet363, 768–774. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jauch, E. C. et al. Part 11: adult stroke: 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation122, 818–828. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971044 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebinger, M. et al. Effects of golden hour thrombolysis: a prehospital acute neurological treatment and optimization of medical care in stroke (PHANTOM-S) substudy. JAMA Neurol.72, 25–30. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3188 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunz, A. et al. Functional outcomes of pre-hospital thrombolysis in a mobile stroke treatment unit compared with conventional care: an observational registry study. Lancet Neurol.15, 1035–1043. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30129-6 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oddo, M. et al. Fluid therapy in neurointensive care patients: ESICM consensus and clinical practice recommendations. Intensive Care Med.44, 449–463. 10.1007/s00134-018-5086-z (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, W. H., Yan, W. Q., Song, X., Zhou, W. Q. & Chen, Z. Fluid resuscitation with balanced crystalloids versus normal saline in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med.30, 28. 10.1186/s13049-022-01015-3 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfortmueller, C. A. & Fleischmann, E. Acetate-buffered crystalloid fluids: current knowledge, a systematic review. J. Crit. Care. 35, 96–104. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.05.006 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenhut, M. Adverse effects of rapid isotonic saline infusion. Arch. Dis. Child.91, 797. 10.1136/adc.2006.100123 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modi, M. P., Vora, K. S., Parikh, G. P. & Shah, V. R. A comparative study of impact of infusion of ringer’s lactate solution versus normal saline on acid-base balance and serum electrolytes during live related renal transplantation. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl.23, 135–137 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aronson, P. S. & Giebisch, G. Effects of pH on potassium: new explanations for old observations. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.22, 1981–1989. 10.1681/ASN.2011040414 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid, F., Lobo, D. N., Williams, R. N., Rowlands, B. J. & Allison, S. P. Ab)normal saline and physiological hartmann’s solution: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 104, 17–24 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobo, D. N. et al. Dilution and redistribution effects of rapid 2-litre infusions of 0.9% (w/v) saline and 5% (w/v) dextrose on haematological parameters and serum biochemistry in normal subjects: a double-blind crossover study. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 101, 173–179 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Regenmortel, N. et al. Effect of isotonic versus hypotonic maintenance fluid therapy on urine output, fluid balance, and electrolyte homeostasis: a crossover study in fasting adult volunteers. Br. J. Anaesth.118, 892–900. 10.1093/bja/aex118 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Regenmortel, N. et al. 154 compared to 54 mmol per liter of sodium in intravenous maintenance fluid therapy for adult patients undergoing major thoracic surgery (TOPMAST): a single-center randomized controlled double-blind trial. Intensive Care Med.45, 1422–1432. 10.1007/s00134-019-05772-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Regenmortel, N. et al. Fluid-induced harm in the hospital: look beyond volume and start considering sodium. From physiology towards recommendations for daily practice in hospitalized adults. Ann. Intensive Care. 11, 79. 10.1186/s13613-021-00851-3 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Regenmortel, N. et al. Effect of sodium administration on fluid balance and sodium balance in health and the perioperative setting. Extended summary with additional insights from the MIHMoSA and TOPMAST studies. J. Crit. Care. 67, 157–165. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.10.022 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gosling, P. Salt of the Earth or a drop in the ocean? A pathophysiological approach to fluid resuscitation. Emerg. Med. J.20, 306–315. 10.1136/emj.20.4.306 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baez, G. et al. Hyponatremia and malnutrition: a comprehensive review. Ir. J. Med. Sci.10.1007/s11845-023-03490-8 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook, A. M. et al. Guidelines for the acute treatment of cerebral edema in neurocritical care patients. Neurocrit Care. 32, 647–666. 10.1007/s12028-020-00959-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz, L., Guais, A., Pooya, M. & Abolhassani, M. Is inflammation a consequence of extracellular hyperosmolarity? J. Inflamm. (Lond). 6, 21. 10.1186/1476-9255-6-21 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darmon, M. et al. Association between hypernatraemia acquired in the ICU and mortality: a cohort study. Nephrol. Dial Transpl.25, 2510–2515. 10.1093/ndt/gfq067 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulger, E. M. et al. Out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation following severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Jama304, 1455–1464. 10.1001/jama.2010.1405 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aiyagari, V., Deibert, E. & Diringer, M. N. Hypernatremia in the neurologic intensive care unit: how high is too high? J. Crit. Care. 21, 163–172. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.10.002 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, P. P. et al. Hypertonic sodium resuscitation is associated with renal failure and death. Ann. Surg.221, 543–554. 10.1097/00000658-199505000-00012 (1995). discussion 554 – 547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Froelich, M., Ni, Q., Wess, C., Ougorets, I. & Hartl, R. Continuous hypertonic saline therapy and the occurrence of complications in neurocritically ill patients. Crit. Care Med.37, 1433–1441. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c1933 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers, W. J. et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 49, e46-e110 (2018). (2018). 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Malbrain, M. et al. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: it is time to consider the four d’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann. Intensive Care. 8, 66. 10.1186/s13613-018-0402-x (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samary, C. S. et al. Focal ischemic stroke leads to lung injury and reduces alveolar macrophage phagocytic capability in rats. Crit. Care. 22, 249. 10.1186/s13054-018-2164-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan, J. L. et al. Integrative physiological assessment of cerebral hemodynamics and metabolism in acute ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab.42, 454–470. 10.1177/0271678X211033732 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hahn, R. G., Isacson, M. N., Fagerstrom, T., Rosvall, J. & Nyman, C. R. Isotonic saline in elderly men: an open-labelled controlled infusion study of electrolyte balance, urine flow and kidney function. Anaesthesia71, 155–162. 10.1111/anae.13301 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pflugfelder, S. C. et al. Severity of Sjogren’s Syndrome Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca Increases with Increased Percentage of Conjunctival Antigen-Presenting Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.1910.3390/ijms19092760 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Ip, W. K. & Medzhitov, R. Macrophages monitor tissue osmolarity and induce inflammatory response through NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasome activation. Nat. Commun.6, 6931. 10.1038/ncomms7931 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura, Y. Current approach to rodents as patients. J. Exot Pet. Med.19, 36–55. 10.1053/j.jepm.2010.01.014 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowland, N. E. Food or fluid restriction in common laboratory animals: balancing welfare considerations with scientific inquiry. Comp. Med.57, 149–160 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocha, N. N. et al. The impact of fluid status and decremental PEEP strategy on cardiac function and lung and kidney damage in mild-moderate experimental acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Res.22, 214. 10.1186/s12931-021-01811-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hahn, R. G. & Lyons, G. The half-life of infusion fluids: an educational review. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol.33, 475–482. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000436 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Supanc, V., Biloglav, Z., Kes, V. B. & Demarin, V. Role of cell adhesion molecules in acute ischemic stroke. Ann. Saudi Med.31, 365–370. 10.4103/0256-4947.83217 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsukita, S., Furuse, M. & Itoh, M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.2, 285–293. 10.1038/35067088 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keddissi, J. I., Youness, H. A., Jones, K. R. & Kinasewitz, G. T. Fluid management in acute respiratory distress syndrome: A narrative review. Can. J. Respir Ther.55, 1–8. 10.29390/cjrt-2018-016 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caregaro, L., Di Pascoli, L., Favaro, A., Nardi, M. & Santonastaso, P. Sodium depletion and hemoconcentration: overlooked complications in patients with anorexia nervosa? Nutrition21, 438–445. 10.1016/j.nut.2004.08.022 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galea, J. & Brough, D. The role of inflammation and interleukin-1 in acute cerebrovascular disease. J. Inflamm. Res.6, 121–128. 10.2147/JIR.S35629 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amantea, D., Bagetta, G., Tassorelli, C., Mercuri, N. B. & Corasaniti, M. T. Identification of distinct cellular pools of interleukin-1beta during the evolution of the neuroinflammatory response induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the brain of rat. Brain Res.1313, 259–269. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.017 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hendryk, S., Jarzab, B. & Josko, J. Increase of the IL-1 beta and IL-6 levels in CSF in patients with vasospasm following aneurysmal SAH. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett.25, 141–147 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.da Silva, H. et al. Evaluation of temperature induction in focal ischemic thermocoagulation model. PLoS One. 13, e0200135. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200135 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heil, L. B. B. et al. Dexmedetomidine compared to low-dose ketamine better protected not only the brain but also the lungs in acute ischemic stroke. Int. Immunopharmacol.124, 111004. 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111004 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seay, N. W., Lehrich, R. W. & Greenberg, A. Diagnosis and management of disorders of body Tonicity-Hyponatremia and hypernatremia: core curriculum 2020. Am. J. Kidney Dis.75, 272–286. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.014 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilcox, C. S. Regulation of renal blood flow by plasma chloride. J. Clin. Invest.71, 726–735. 10.1172/jci110820 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khawaja, S., Jafri, L., Siddiqui, I., Hashmi, M. & Ghani, F. The utility of neutrophil gelatinase-associated Lipocalin (NGAL) as a marker of acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill patients. Biomark. Res.7, 4. 10.1186/s40364-019-0155-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M. & Altman, D. G. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol.8, e1000412. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendes, R. S. et al. Iso-Oncotic albumin mitigates brain and kidney injury in experimental focal ischemic stroke. Front. Neurol.11, 1001. 10.3389/fneur.2020.01001 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sousa, G. C. et al. Comparative effects of Dexmedetomidine and Propofol on brain and lung damage in experimental acute ischemic stroke. Sci. Rep.11, 23133. 10.1038/s41598-021-02608-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Percie du Sert. Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol.18, e3000411. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bazin, J. E., Constantin, J. M. & Gindre, G. [Laboratory animal anaesthesia: influence of anaesthetic protocols on experimental models]. Ann. Fr. Anesth. Reanim. 23, 811–818. 10.1016/j.annfar.2004.05.013 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mortola, J. P. & Noworaj, A. Two-sidearm tracheal cannula for respiratory airflow measurements in small animals. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir Environ. Exerc. Physiol.55, 250–253. 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.1.250 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uhlig, C. et al. The effects of salbutamol on epithelial ion channels depend on the etiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome but not the route of administration. Respir Res.15, 56. 10.1186/1465-9921-15-56 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.da Silva, A. L. et al. Pressure-support compared with pressure-controlled ventilation mitigates lung and brain injury in experimental acute ischemic stroke in rats. Intensive Care Med. Exp.11, 93. 10.1186/s40635-023-00580-w (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blanco, N. G. et al. Extracellular vesicles from different sources of mesenchymal stromal cells have distinct effects on lung and distal organs in experimental Sepsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2410.3390/ijms24098234 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Chen, Z. et al. Histological quantitation of brain injury using whole slide imaging: a pilot validation study in mice. PLoS One. 9, e92133. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092133 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akamine, R. et al. Usefulness of the 5’ region of the cDNA encoding acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 conserved among rats, mice, and humans as a standard probe for gene expression analysis in different tissues and animal species. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 70, 481–486. 10.1016/j.jbbm.2006.11.008 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc.3, 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Santos, V. D. Therapeutic window for treatment of cortical ischemia with bone marrow-derived cells in rats. Brain Res.1306, 149–158. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.094 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.