Abstract

Purpose

Motor skills are essential for carrying out daily tasks and the practice of physical activities can help to increase these skills. Being combat sports, it can be an alternative practice with this objective. However, it is not known which is the ideal modality. Therefore, the aim was to analyze the effects of nine months of practicing Muay Thai (MT) and Judo on the motor skills of children and adolescents.

Methods

A sample of 109 young people from a Philanthropic Institution was distributed into: control (n = 36), Judo (n = 29) and MT (n = 44). The following motor skills tests were carried out: balance on the beam, side jumps, single-leg jump and transfer onto the platform. The intervention lasted nine months, twice a week for one hour.

Results

After nine months, the Judo and Muay Thai groups showed increased values in lateral jumps (Judo p-value < 0.001; Muay Thai p-value < 0.001), and transfer platform (Judo p-value = 0.007; Muay Thai p-value < 0.001) from the pre-moment compared to the post-moment. In the single-leg jump, the Judo (p-value = 0.011) and MT (p-value < 0.001) groups were different compared to the control group.

Conclusion

The practice of combat sports was effective in causing improvements in the motor skills of young.

Keywords: Children, Adolescents, Motor skills, Judo, Muay Thai

Introduction

A motor skill is a voluntary task or action that aims to move a certain region of the body. These movements can be simple or complex, and are separated into fundamental or specialized skills. Fundamental skills include stability (e.g. balancing and rolling), locomotion (e.g. running and jumping) and manipulation (e.g. throwing and kicking). Specialized skills consist of more refined skills, such as a sequence of jumps, for example [1].

Motor skill levels, in turn, are made up of a varied set of aptitudes, whether they are health-related (strength, muscular endurance, flexibility) or performance-related (speed, agility and balance) [2, 3]. These skills are essential for performing everyday tasks such as climbing a set of stairs or aiming for sports performance, i.e. for a person to be able to perform any level of motor skill, a set of aptitudes is required which are influenced by the quality and quantity of motor experiences that the person has had [4–6].

Motor development takes place in phases and stages, one of the main phases of which is in childhood and is influenced by environmental and individual conditions, and the practice of physical activities can help to increase motor skills [7, 8]. However, children and adolescents who spend large amounts of time in sedentary activities may be more likely to have their motor development impaired [9]. It is therefore essential to encourage young people to practice physical activity from an early age so that they have a better chance of maintaining or increasing their motor skills. In a meta-analysis that included twenty studies, Van Capelle et al. [10] reported that different types of physical activity interventions were associated with improved levels of motor skills in schoolchildren.

In this sense, different physical activity practices can be encouraged for children and adolescents, and one of the physical activity practices that has been gaining followers is combat sports. This type of activity can be classified into combat sports of domain and percussion. Domain combat spports are fights whose technical principles involve “grabbing” using systems of levers and twists; judo and jiu-jitsu are examples of domain fights, while in percussion fights the main objective is to touch the opponent; examples of this type of combat sports include karate and Muay Thai [11].

Alesi et al. [12] in a study comparing 19 karate children with 20 sedentary children observed that better values were observed in the battery of motor tests in karate children when compared to sedentary children. Similar findings were observed by Li et al. [13] in a study with children aged 5–6 years in which after practicing martial arts for 30 min twice a week, the children who were in the training group had better values in the balance ability test when compared to their peers who were in the free activity group. Padulo et al. [13] observed beneficial effects on the muscular power and amplitude of children aged between 8 and 12 years after a week of high-intensity karate training. In the study by Katic et al. [14], which assessed 50 karate practitioners aged between 13 and 15, it was found that, compared to other groups, karateka had higher quantitative measures of flexibility, psychomotor speed, coordination and burst of strength. These data demonstrate the benefits that combat sports can bring to those who practice them.

Despite the benefits of combat sports for the motor skills of children and adolescents, some aspects still need to be studied in greater depth, one of which is that only one of the studies cited was an intervention study, and even then it lasted only 10 weeks; another factor is that these studies did not consider adjustments for sex, age and somatic maturation in their analyses, factors which can influence motor skills. It should also be pointed out that there are few longitudinal studies in the literature that have aimed to compare whether two different types of combat sports, domain and percussion, could exert different influences when compared to each other or to young people who have not practiced this type of physical activity. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the effects of nine months of practicing two different types of fighting disciplines, one of which is percussion (Muay Thai) and one of domain (Judo), which provide different responses in motor skills when compared to each other, as well as to compare these responses with young people who do not practice these sports disciplines, considering sex, age and somatic maturation as adjustment factors.

Methods

Sample

The study had a longitudinal design, lasting nine months, and its activities began in the first half of 2017 (June), in the city of Presidente Prudente - SP. The research was carried out in partnership with a philanthropic institution that offers various activities to young people in situations of socioeconomic vulnerability. (chess, computing, different sports, among others). As inclusion criteria, in order to take part in the study, the young people had to: (i) be between 6 and 15 years old; (ii) be duly enrolled and taking part in the institution’s activities; (iii) not have any kind of serious orthopaedic illness that would make it impossible for them to practice combat sports activities; (iv) not be pregnant. All the participants presented a Free and Informed Consent Form duly signed by their parents or guardians, authorizing them to take part in the study. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CAAE: 26702414.0.0000.5402).

Anthropometric measurements

Body mass, height and trunk height was measured in the same way as in the study of Saraiva et al. [15] in accordance with the standards of Freitas Jr [16].

Somatic maturation

Somatic maturation was assessed using the formula for Maturity Offset, to estimate how many years are left or have passed the peak high velocity. This formula was developed by Mirwald et al. [17] and uses anthropometric measurements such as weight, height, trunk height and leg length. However, a different formula is used for each sex. Somatic maturation was used to adjust the statistical analyses of the parameters evaluated in this study because the sample was made up of children and adolescents who are in a developmental phase, which could influence the variables analyzed here. To calculate the age at peak high velocity, the Maturity Offset was subtracted from the chronological age.

Motor skills

To assess motor skills, the four tests from the KTK (Körperkoordination Test für Kinder - KTK) battery by Kiphard and Schilling [18] were used, consisting of walking backwards on balance beam, jumping sideways (lateral jump), hopping for height (single-leg jump, trials using each leg) and moving sideways (platform transfer). This assessment was carried out before the project began and after it ended.

The walking backwards on balance beam is a test that assesses coordination and precision. This test consists of three bars measuring: Wooden beam 1: 3.60 m x 6 cm; Wooden beam 2: 3.60 m x 4.5 cm; Wooden beam 3: 3.60 m x 3 cm. In this test, the student has to walk over each bar three times (starting from beam 1 to beam 3) and each step taken over the bar is counted (the support of the first foot does not count as a step). The number of steps taken at a time is a maximum of eight.

The lateral jump test consists of the child/adolescent jumping with both legs over a piece of wood, from one side to the other, as fast as possible for 15 s. The test consists of two attempts with an interval of 1 min between them. At the end, the number of jumps is added up.

The purpose of the single-leg jump is to assess the lower limbs, using twelve foam blocks measuring 5 cm in height. In this test, the subject’s task is to jump with one leg over one or more foam blocks placed on top of each other. The height the subject has to jump varies from 5 cm to 5 cm, for example, totaling a maximum height of 60 cm. For each height, if the individual manages to pass the first time, 3 points are scored, if they succeed on the second valid attempt, 2 points are scored and on the third attempt, 1 point is scored. Errors are considered to be when the individual knocks over the foam blocks when jumping, overcomes the foam block but falls to the ground with both legs or jumps with the left leg and falls to the ground with the right leg and vice versa. If the individual fails to jump a certain height after 3 attempts, the test is terminated. The maximum score obtained is 36 points for each leg, giving a total of 72 points.

In the platform transfer test, the material consists of two wooden platforms measuring 25 × 25 × 1.5 cm, at the corners of which four 3.5 cm high feet are screwed. The test consists of this task: the individual stands on one of the platforms and, at the assessor’s signal, must transfer the platforms as many times as they can in a period of twenty seconds. The individual performs the test twice and at the end the values of the two attempts are added together to give a final score.

Intervention

The intervention group was made up of two different modalities: Judo and Muay Thai. The fighting practice classes were held in a space provided (already containing tatami mats) by this Philanthropic Institution. The fight classes were offered at times when these teenagers would already be in the project, avoiding clashes with their school’s class schedule, as well as avoiding possible travel costs, since the Institution develops projects with children and adolescents residents of the neighborhood where it is located. All participants were assessed before the beginning and at the end of the nine months of intervention. Following physical activity guidelines [20], sessions were held twice a week, lasting approximately 60 min, through activities and games that incorporated specific movements from combat sports (projections, displacements, balance and imbalance in the case of judo and touches through kicks and punches, and dodges in the case of Muay Thai [11]. These activities had moderate intensity and were evaluated using the Borg scale [19] through the participants’ subjective perception of effort. Intensity was measured using this scale because the use of heart monitors is not recommended in contact sports, as they could cause abrasions.

Control group

The control group was also made up of young people who did not participate in the fighting activities organized at the Institution, but who participated in other activities offered by this association (chess, computer science, theater, recreational activities, among others) and who also had the desire to carry out the evaluations of the health sessions offered in the fights project.

Statistical analysis

The Komogorov-Smirnov normality test was used in the statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the groups at baseline. The comparison of possible differences between the three groups (judo, Muay Thai and control) was carried out by repeated measures ANOVA adjusted for sex, Maturity Offset and class attendance (dichotomized 0 for those above 75% and 1 for those who exceeded absences). In addition, the delta (Δ) was calculated by subtracting moment 1 (M1) from moment 2 (M2) and the Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for sex, Maturity Offset, class attendance and the variable itself at the initial moment, since there was a difference between the groups at the initial moment for transferring on the platform and balance beam. Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to identify any differences. The statistical package used was SPSS version 13.0 and the significance level adopted was p-value < 0.05.

Results

In the sample description, when comparing the groups at the initial moment, there was a difference between them in the variables of balance beam and transfer on the platform (p-valor = 0.044) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of the sample at the initial moment

| Control (n = 36) Mean (SD) |

Judo (n = 29) Mean (SD) |

Muay Thai (n = 44) Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 9.31 (2.94) | 9.03 (1.54) | 9.16 (0.83) |

| Body mass (kg) | 41.38 (18.84) | 44.13 (16.32) | 36.91 (9.94) |

| Height (cm) | 138.66 (17.79) | 144.28 (12.46) | 138.65 (7.58) |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 20.49 (5.17) | 20.61 (5.25) | 18.98 (4.02) |

| Maturity Offset (years) | -3.93 (1.89) | -3.90 (1.04) | -4.19 (0.57) |

| APHV (years) | 13.24 (1.14) | 12.94 (0.72) | 13.35 (0.46) |

| Balance beam (steps)* | 36.67 (15.49) | 36.21 (15.00) | 43.66 (13.48) |

| Lateral jump (jumps) | 46.50 (14.58) | 47.76 (14.71) | 49.30 (13.84) |

| Single-leg jump (score) | 26.58 (21.03) | 36.55 (13.39) | 33.66 (18.38) |

| Transfer platform (transfers)* | 17.08 (4.52) | 17.41 (3.77) | 19.32 (4.29) |

SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index; APHV = age of peak high velocity; *= difference between groups p-value = 0.044

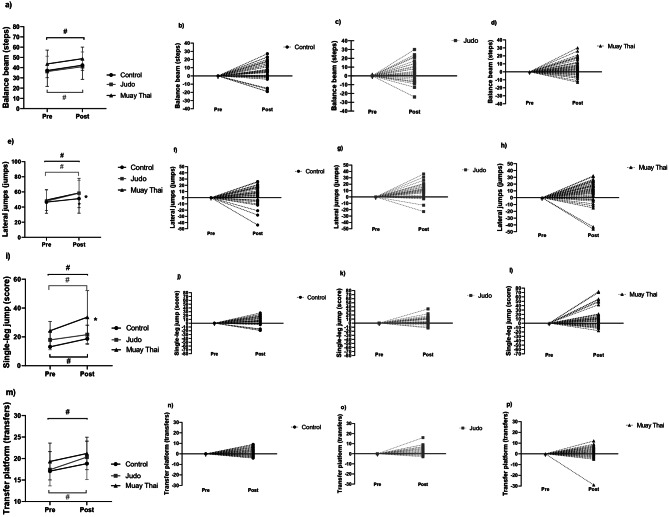

When the repeated measures ANOVA with adjustment for sex, age, frequency of intervention and the variable itself in the baseline (balance bean and transfer platform) was analyzed, in the balance beam, there was a difference in the effect time (F1,2= 34.298; p-value < 0.001; η2p = 0.252), but not in the effects group (F1,2= 2.885; p-value = 0.060; η2p = 0.054), and interaction (F1,2= 2.885; p-value = 0.060; η2p = 0.054) (Fig. 1a). Specifically, the control (p-value = 0.031) and Muay Thai (p-value < 0.001) groups showed an increase in balance beam values from the pre-moment compared to the post-moment. In addition to the time effect (F1,2= 7.274; p-value = 0.008; η2p = 0.066), lateral jumps also showed a difference in the group effect (F1,2= 3.248; p-value = 0.043; η2p = 0.059), but not interaction (F1,2= 1.668; p-value = 0.194; η2p = 0.031) (Fig. 1e). The control group presented lower values in lateral jumps, being different from the Muay Thai group (p-value = 0.038). The Judo groups (p-value < 0.001) and the Muay Thai group (p-value < 0.001) showed increased values in lateral jumps from the pre-moment compared to the post-moment. Just like the single-leg jump, which showed a difference in time effect (F1,2= 4.359; p-value = 0.039; η2p = 0.041), and group effect (F1,2= 11.379; p-value < 0.001; η2p = 0.181), but not interaction effect (F1,2= 0.736; p-value = 0.481; η2p = 0.014) (Fig. 1i). Control group presented lower single leg jump values, different from the Judo group (p-value = 0.011) and the Muay Thai group (p-value < 0.001). All groups showed increased values in the single leg jump from the pre moment compared to the post moment: control group (p-value = 0.002), Judo group (p-value = 0.002) and Muay Thai group (p-value = 0.002). In turn, transfer platform time effect (F1,2= 77.371; p-value < 0.001; η2p = 0.431), but not group (F1,2= 1.657; p-value = 0.196; η2p = 0.031) and interaction effect (F1,2= 1.657; p-value = 0.196; η2p = 0.031) (Fig. 1m). The Judo (p-value = 0.007) and Muay Thai (p-value < 0.001) groups showed an increase in transfer platform values from the pre-moment compared to the post-moment.

Fig. 1.

Balance beam (a), lateral jumps (e), single-leg jump (i), and transfer platform (m); Individual values for balance beam of control (b), Judo (c), and Muay Thai group (d); Individual values for lateral jumps of control (f), Judo (g), and Muay Thai group (h); Individual values for single-leg jump of control (j), Judo (k), and Muay Thai group (l); Individual values for transfer platform of control (n), Judo (o), and Muay Thai group (p). Note: Mean and standard deviation of balance beam, lateral jumps, single-leg jump, and transfer platform. Individual values are presented as the difference between the post-test in relation to the pre-test; * indicates the difference between groups and # indicates the difference between times

Considering that there were differences between the groups at the initial moment, an ANCOVA was performed adjusting for, in addition to the variables in the previous table, the variable itself at the initial moment. Thus, there was a difference between the deltas in the single-leg jump (p-value < 0.001) (Table 2). Specifically, Muay Thai showed higher values when compared to the control group (p-value = 0.002).

Table 2.

Comparison of motor skills deltas between groups after nine months of intervention

| Control (n = 36) ΔMeana (SD) |

Judo (n = 29) ΔMeana (SD) |

Muay Thai (n = 44) ΔMeana (SD) |

Levene | F | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance beam (steps) | 3.69 (1.68) | 2.57 (1.75) | 8.18 (1.56) | 0.154 | 2.885 | 0.060 |

| Lateral jumps (jumps) | 3.10 (2.61) | 9.80 (2.70) | 11.02 (2.38) | 0.531 | 2.504 | 0.087 |

| Single-leg jump (score) | 4.38 (1.96) | 10.22 (2.00) | 17.92 (1.76)b | 0.566 | 11.297 | < 0.001 |

| Transfer platform (transfers) | 1.08 (0.71) | 2.02 (0.73) | 3.00 (0.65) | 0.875 | 1.657 | 0.196 |

a= Adjusted for sex, frequency, Maturity Offset and the variable itself at the initial moment; b= Muay Thai is different from control p = 0.002; SD = standard deviation; M1 = initial moment; M2 = moment after 9 months

Discussion

In the present longitudinal study, which carried out the activities of the philanthropic institution, it was observed that young people who practiced Judo or Muay Thai compared to the control group obtained better results in the lateral jump, single-leg jump, and platform transfer tests when compared from the initial moment to the final moment after 9 months of intervention.

Groups of children and adolescents undergoing interventions with a physical activity program show better motor performance when compared to individuals who do not practice any physical activity. Van Capelle et al. [10] concluded that physical activities in preschoolers (3 to 5 years old) that were applied by teachers bring significant benefits in functional motor skills. A recent systematic review analyzed the effects of combat sports such as karate, judo, taekwondo and aikido on children and adolescents between 4 and 18 years of age and observed positive effects in relation to the components of physical discovery, when compared to experimental programs, but also with control group [20].

Venetsanou et al. [21] analyzed the motor proficiency of 66 children, aged 4 to 6 years, through the impact of a 20-week intervention with an introductory program to traditional Greek dance. After the intervention period, it was observed that the experimental group improved, this was due to activities that involved percussive, rhythmic, locomotion movements that were focused on the body awareness of this population, and the control group also showed an improvement that can be explained due to the growth process itself in which motor performance tends to evolve with advancing age, a situation that occurred in this study where the control group also had an evolution in the tests performed.

A study carried out in Serbia by Bala et al. [22] evaluated the differences in body composition and motor skills of 341 children trained and untrained in judo. The sample was separated into age and sex groups, with male and female Judokas aged 11 to 13 and aged 14 to 16 practicing and not practicing the martial art. In general, for both sexes, significant differences were observed in chest measurements, arm circumference, smaller skinfolds in the triceps, greater strength and greater speed when compared to untrained men, but girls had better motor coordination, and boys had a better difference. in the circumference of the forearm, which possibly occurred due to genetic differences between the sex, in general, judo practitioners stand out in body composition and motor skill levels when compared to individuals not trained in this modality. Children trained with an adequate training volume may have specific characteristics of the sport practiced. The greater the weekly training load, the greater the contribution to physical fitness and motor coordination levels [23, 24].

In a quasi-experimental study, Fernandes et al. [25] evaluated motor skills in 43 schoolchildren with an average age of 7 years, who underwent an intervention based on athletics. The KTK test battery was used to analyze the performance of these individuals, separating them by sex, age, control and experimental groups, with better performance of boys in the single-leg jump test and lateral jump pre and post intervention and transfer onto the platform in the post-intervention period, while the girls excelled in the pre and post balance beam test, and transposition on the platform in the pre. The study by Fernandes et al. [25] did not obtain a significant difference by age, while in the group analysis, the experimental group had a significant difference in the balance beam, side jump and single-leg jump. These differences can be observed due to activities that require a large number of jumps within athletics, being possible influencers for this result since the control group carried out the activities of the school’s normal schedule. In general, these results prove that the practice of physical activities is effective for the motor development of adolescents. One of the possible reasons may come from the wide range of motor experiences that different types of physical activity provide. Furthermore, it should be noted that in combat sports such as judo and Muay Thai it is necessary to use both sides of the body and not just the dominant hemibody, allowing the individual to develop laterality in depth and subsequently be able to have greater motor development.

This study has some strengths, such as a nine-month intervention period, monitoring of somatic maturation, statistical analysis used in conjunction with data adjustment, and two combat sports modalities, which are scarce in the database. Another point is that the information refers to Latin American children and adolescents, providing new findings in the literature, since most studies that aimed to evaluate the effects of sports practice on the motor skills of children and adolescents were carried out in developed countries [26]. There were main limitations, such as the non-randomization of sample, being susceptible to selection bias and reduced internal validity, also affecting intragroup equivalence at baseline. In addition, the fact of this intervention has been carried out among youth with low socioeconomic status from a philanthropic institution precludes generalizability of the findings to broader populations. However, we highlight the difficulty of carrying out an RCT in a philanthropic institution such as the one where we carried out our study. In this institution, children and adolescents chose the sports (judo or muay thai) they preferred to participate in. This was done at the request of the philanthropic institution’s coordination. The lack of monitoring of the activities carried out by the children in the control group outside the philanthropic institution during their leisure time during the intervention period should be considered a limitation. Non-use to use physiological monitoring tools (e.g., heart rate monitors or accelerometers) were not used due to the contact nature of combat sports. Although we used the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale, which is subjective and may vary across individuals, it should be considered a limitation. Failure to adjust analyses for psychological, nutritional, academic, and environmental factors (e.g., home support, peer influences) may also affect the findings through their possible influence on motor development.

We concluded that the practice of combat sports can improve the motor skills of children and adolescents, with both Judo and Muay Thai obtaining better results than the control group. Muay Thai proved to be more effective in general in the tests carried out and obtained significant results in the single-leg jump test. However, future studies are needed to form a broader database on combat sports and their impact and relationship with different areas of health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude the philanthropic institution for the partnership, to the volunteers who participated in the study, to the parents and/or guardians who authorized them to participate, and to all the research staff members in the collection, intervention, and tabulation of data.

Author contributions

B.T.C.S., W.R.T., A.B.S, , and D.G.D.C. wrote the main manuscript text; B.T.C.S., E.P.A., S.C.B.S., D.T.F., G.F. prepared figures and tables; B.T.C.S., W.R.T., A.B.S, E.P.A., S.C.B.S., D.T.F., G.F., L.D.D., and D.G.D.C. reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the city of Presidente Prudente, São Paulo, Brazil and was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the São Paulo State University-FCT/UNESP (CAAE: 26702414.0.0000.5402, Opinion number: 549.549, approved on March 7, 2014). The parents/legal guardians provided written consent. Lastly, the participants were recruited by convenience, and those who refused to participate were not included in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gallahue DL, Ozmun JC, Goodway JD, de Sales DR, Petersen RDS. Compreendendo o desenvolvimento motor – bebês, crianças, adolescentes e adultos., 7th ed., 2013.

- 2.Batez M, Milošević Ž, Mikulić I, Sporiš G, Mačak D, Trajković N. Relationship between motor competence, physical fitness, and academic achievement in young School-Aged children. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1–7. 10.1155/2021/6631365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams TC, Terlizzi BM, De Meester A, Sacko RS, Irwin JM, Luz C, Rodrigues LP, Cordovil R, Lopes VP, Schneider K, Stodden DF. Potential relevance of a motor skill proficiency barrier on health-related fitness in youth. Eur J Sport Sci. 2023;23:1771–8. 10.1080/17461391.2022.2153300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biino V, Giustino V, Gallotta MC, Bellafiore M, Battaglia G, Lanza M, Baldari C, Giuriato M, Figlioli F, Guidetti L, Schena F. Effects of sports experience on children’s gross motor coordination level. Front Sports Act Living. 2023;5. 10.3389/fspor.2023.1310074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Lopes LO, Lopes VP, Santos R, Pereira B. Associações entre actividade física, habilidades e coordenação Motora Em Crianças Portuguesas. Revista Brasileira De Cineantropometria E Desempenho Humano. 2010;15–21. 10.5007/1980-0037.2011v13n1p15.

- 6.Barnett LM, Lai SK, Veldman SLC, Hardy LL, Cliff DP, Morgan PJ, Zask A, Lubans DR, Shultz SP, Ridgers ND, Rush E, Brown HL, Okely AD. Correlates of gross motor competence in children and adolescents: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46:1663–88. 10.1007/s40279-016-0495-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laukkanen A, Pesola A, Havu M, Sääkslahti A, Finni T. Relationship between habitual physical activity and gross motor skills is multifaceted in 5- to 8‐year‐old children. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24. 10.1111/sms.12116. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Borges Neto JdeS, Benda RN, Novais RLR, Campos CG, Bicalho JMF, Romano MCC, Lamounier JA. Desempenho motor de habilidades fundamentais de estudantes de Ambos Os Sexos do Ensino fundamental. Res Soc Dev. 2021;10:e361101523109. 10.33448/rsd-v10i15.23109. [Google Scholar]

- 9.dos Santos G, Guerra PH, Milani SA, Santos ABD, Cattuzzo MT, Ré AHN. Comportamento sedentário e competência Motora Em Crianças e adolescentes: Revisão. Rev Saude Publica. 2021;55:57. 10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055002917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Capelle A, Broderick CR, van Doorn N, Ward RE, Parmenter BJ. Interventions to improve fundamental motor skills in pre-school aged children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:658–66. 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchini E, Del FB, Vecchio. Estudos Em modalidades esportivas de combate: Estado Da Arte. Revista Brasileira De Educação Física E Esporte. 2011;25:67–81. 10.1590/S1807-55092011000500008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alesi M, Bianco A, Padulo J, Vella FP, Petrucci M, Paoli A, Palma A, Pepi A. Motor and cognitive development: the role of karate. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4:114–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padulo J, Chamari K, Chaabène H, Ruscello B, Maurino L, Sylos Labini P, Migliaccio GM. The effects of one-week training camp on motor skills in karate kids. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2014;54:715–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katić R, Jukić J, Milić M. Biomotor status and Kinesiological education of students aged 13 to 15 years - example: karate. Coll Antropol. 2012;36:555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saraiva BTC, Scarabottolo CC, Christofaro DGD, Silva GCR, Freitas Junior IF, Vanderlei LCM, Ritti-Dias RM, Milanez VF. Effects of 16 weeks of muay Thai training on the body composition of overweight/obese adolescents., IDO MOVEMENT FOR CULTURE. J Martial Arts Anthropol. 2021;21:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freitas IF, Júnior. Padronização de Medidas antropométricas e Avaliação Da composição corporal, Selo literário 20 Anos Da regulamentação Da Profissão. São Paulo: de Educação Física; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirwald RL, Baxter-Jones ADG, Bailey DA, Beunen GP. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:689–94. 10.1097/00005768-200204000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiphard EJ, Schilling F. Körperkoordinationstest für Kinder: KTK, 1974. [PubMed]

- 19.Borg G, Hassmén P, Lagerström M. Perceived exertion related to heart rate and blood lactate during arm and leg exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1987;56:679–85. 10.1007/BF00424810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stamenković A, Manić M, Roklicer R, Trivić T, Malović P, Drid P. Effects of participating in martial arts in children: A systematic review. Children. 2022;9:1203. 10.3390/children9081203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venetsanou F, Kambas A. How can a traditional Greek dances programme affect the motor proficiency of pre-school children? Res Dance Educ. 2004;5:127–38. 10.1080/14617890500064019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bala G, Drid P. Anthropometric and motor features of young judoists in Vojvodina. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:1347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farhat F, Masmoudi K, Hsairi I, Smits-Engelsman BCM, Mchirgui R, Triki C, Moalla W. The effects of 8 weeks of motor skill training on cardiorespiratory fitness and endurance performance in children with developmental coordination disorder. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015;40:1269–78. 10.1139/apnm-2015-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Opstoel K, Pion J, Elferink-Gemser M, Hartman E, Willemse B, Philippaerts R, Visscher C, Lenoir M. Anthropometric characteristics, physical fitness and motor coordination of 9 to 11 year old children participating in a wide range of sports. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126282. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Fernandes S, de Moura SS, da Silva SA, Coordenação motora de escolares do ensino fundamental: influência de um programa de intervenção. J Phys Educ. 2017;28. 10.4025/jphyseduc.v28i1.2842.

- 26.Eddy LH, Wood ML, Shire KA, Bingham DD, Bonnick E, Creaser A, Mon-Williams M, Hill LJB. A systematic review of randomized and case‐controlled trials investigating the effectiveness of school‐based motor skill interventions in 3‐ to 12‐year‐old children. Child Care Health Dev. 2019;45:773–90. 10.1111/cch.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.