Abstract

Background

Relatives play an important role as caregivers in facilitating the recovery of their intensive care unit (ICU) patients during the transition period. Insight into the relatives’ needs is key to improving the continuum of transitional care and guiding family-centred high-quality health care services. This study aimed to comprehensively explore the needs of the relatives during the transition and to identify the factors influencing these needs in China.

Methods

This study adopted a mixed-method explanatory sequential design. The survey completed by relatives included needs levels, anxiety and depression levels, social support levels, and relocation stress levels. Qualitative data from semistructured interviews were collected after the survey to complement and explain the quantitative data. Twelve relatives were interviewed, and the qualitative data were analysed via thematic analysis.

Results

There were 161 valid responses and 12 relatives participated in unstructured face-to-face interviews. The present study identified a relatively high overall level of need. The highest overall mean scores on the need scale subscales were observed for communication needs, need for caregiving skills, and information needs. Six themes were identified: communication and access to information, caregiving guidance, emotional support, financial burden, information for a family care manual, and the comfort of the environment. The level of need was influenced by factors including age, educational attainment, caregiving experience, level of anxiety and depression, and level of relocation stress.

Conclusion

This mixed methods study identified in depth the needs of relatives during the transition period in China. This knowledge will help medical staff better understand relatives’ needs, recognize high-need target relatives and priority should be given to the implementation of tailored supportive care measures.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-025-03608-6.

Keywords: Needs, Relatives, Transitional care, Intensive care unit

Introduction

Recently, critical care technology has been continuously developed, which has significantly improved the survival rate of intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Data from a relevant study show that about 84% of ICU patients can be successfully transferred out every year in China [1]. When the patient’s condition stabilizes and no longer relies on continuous vital sign monitoring and life support from ICU medical staff, the patient will be transferred to a general ward for follow-up treatment [2]. Although the patients’ conditions have been stabilized after treatment, they still need to receive complex and meticulous care services for a period of time after being transferred out of the ICU. Critically ill patients are prone to develop ICU-acquired weakness and decreased activity function during their stay in the ICU, which seriously affects their rehabilitation after transfer out [3]; meanwhile, ICU patients are also susceptible to developing negative emotions such as loneliness, depression, and anxiety, which bring dual challenge physiologically and psychologically to the treatment and rehabilitation. Therefore, these patients in the clinical setting desire the participation of their relatives in decision-making and care [4, 5].

Within the context of China’s strained healthcare resources, hospital bed shortages and overcrowding are prevalent, compounded by a relative scarcity of human resources in wards [6]. Furthermore, deeply rooted Confucian collectivist values emphasize strong familial bonds, leading relatives to actively participate in patient care. Relatives often assume multifaceted roles, acting as caregivers, treatment assistants, and psychological supporters. This involves closely monitoring the patient’s condition, assisting with mobility, managing dietary needs and bodily functions, and providing emotional support. Meanwhile, relatives serve as critical sources of patient information, facilitating doctor-patient communication and integrating family resources throughout the treatment and rehabilitation process. For instance, relatives are expected to possess a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s condition and treatment plan and to actively engage in medical decision-making [7–9].

This seems to be somewhat different from the situation in Western countries. In Western countries, the medical system places more emphasis on the leading role of medical staff, and the participation of relatives during the transition period is relatively low, with more following the arrangements made by medical staff. During hospitalization, nurses and other medical personnel primarily manage treatment and basic care [10]. In China, the phenomenon of deep family involvement in patient care stems from a variety of factors such as special national circumstances, medical environment, traditional concepts, and healthcare principles. Relatives recently transferred from the ICU to general wards often lack caring experience and knowledge, while patients during the transition remain physically vulnerable and require a high standard of care quality and safety. Consequently, relatives express numerous expectations and needs pertaining to care skills, information acquisition, communication, and psychological support. Therefore, a deeper understanding of relatives’ needs is key to improving the continuum of transitional care and guiding family-centred high-quality healthcare services.

Internationally, although there are differences in the delineation of family caring responsibilities in different countries and regions, the involvement of relatives in caring has gradually increased with the transformation of healthcare models and the development of family caring. Particularly with the development of patient- and family-centered care models in recent years, researchers have begun to focus on the conditions of relatives of ICU patients during the transition period. These studies have mainly used qualitative methods to understand the caregiving burden, experiences, and psychological states of relatives during the transition period. Several studies have reported that relatives often experience insufficient information communication in general wards [7, 11–13]. It is crucial for medical staff to engage in proactive communication with relatives and provide them with accurate and pertinent information [12]. Furthermore, relatives reported poor experiences in the general ward and were eager to receive guidance from medical staff for fear that their negligence or mishandling would affect the patient’s recovery. They also wanted to be recognized as an important supportive force by medical staff in the overall care of their loved ones and to be given more opportunities to participate in the care [7, 11–13]. Meanwhile, relatives also confided the hardships and strains of the caregiving process, experiencing both physical and psychological suffering [8].

By reviewing the literature, we found that although many studies have focused on the experiences or perceptions of relatives during the transitional period, few have explored the needs of relatives; the majority were mainly qualitative and lacked quantitative analyses. Furthermore, the needs of relatives may vary on the basis of demographic characteristics, indicating that these factors require further exploration and validation [14]. The comprehensive identification and mapping of the needs of relatives during the transition period would benefit from a mixed method. This knowledge would not only help medical staff gain a deeper understanding of relatives’ needs and provide more attentive and precise medical care but also contribute to the establishment of family-centred high-quality healthcare services. Therefore, the aim of this study was to comprehensively explore the needs of relatives during the transitional period and to identify the factors that influence these needs in China.

Materials and methods

Design

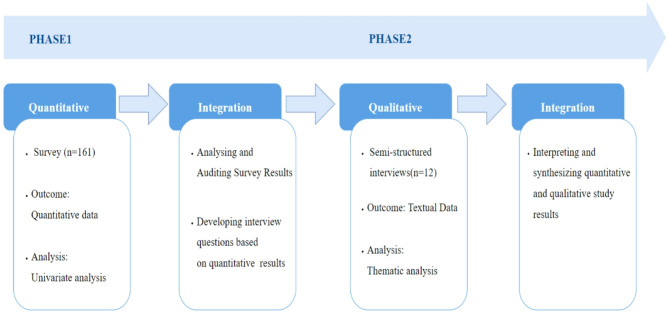

This study adopted a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design to thoroughly explore the needs of relatives of patients during the period after ICU transfer, which followed the Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study (GRAMMS) checklist [15]. Initially, quantitative data was collected and analyzed to assess the current state of these needs and identify associated factors. Subsequently, qualitative research was conducted, guided by the quantitative findings, to explore the meaning underlying specific needs. This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding by addressing the limitations inherent in using either qualitative or quantitative methods independently [16]. The process of this mixed-methods study is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Process of this mixed methods study

Participants

Relatives of ICU patients during the period after ICU transfer were recruited at a tertiary hospital in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, China. The inclusion criteria were defined for both relatives and their patients. For patients, eligibility required being aged ≥ 18 years, having stayed in the ICU for ≥ 24 h, and being stabilized and transferred to a general ward for continued treatment. For relatives, the inclusion criteria were being aged ≥ 18 years, assuming primary responsibility for medical decision-making and caregiving (with a total caregiving time ≥ 6 h per day), and agreeing to participate in this study after explanations were provided. Relatives were excluded if they were unable to fill out the questionnaire for reasons such as cognitive impairment or communication disorders.

For the quantitative section, the usual recommended number of participants in a mixed-methods study is over 50, whereas for the qualitative section, the recommended number is no more than 30 [17]. Ultimately, this study included 161 participants, which conforms to the fundamental participant criteria for mixed methods research.

Instruments

Chinese version of the relatives’ needs scale during the patients in ICU transitional period (RNSP-ICU).

The Chinese version of the RNSP-ICU, developed by Ye Lei et al. [18] in 2021, was mainly based on the social support theory [19] and in the context of Chinese culture, which aims to comprehensively assess the needs of relatives during the transition period from the ICU to a general ward. The scale consists of 22 items across 5 dimensions: need for caregiving skills, communication needs, instrumental support, emotional support, and information needs. These needs are scored using a 5-point Likert scale; scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 correspond to not needed, rarely needed, sometimes needed, often needed, and always needed, respectively. The total score ranges from 22 to 110 points, where a higher score indicates a higher level of individual needs. The scale has a Cronbach’s α of 0.895 and a retest reliability of 0.874. In the current sample, the Cronbach’s α of the total scale was 0.920, and those of each dimension ranged from 0.525 to 0.883.

Family relocation stress scale (FRSS)

FRSS was developed by HyunSoo et al. [20] in 2015 to assess relocation stress of the families of patients transferred from ICU. The scale comprises 17 items with four dimensions. All item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 17 to 85, where lower scores indicating higher levels of family relocation stress. It showed good reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.83. The Chinese version of the FRSS was strictly validated psychometrically and translated linguistically by Zhao Jing et al. [21]. The Cronbach’s α was 0.845 for the total scale and 0.638–0.853 for each dimension.

Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS)

To measure subjective perceived social support, we used the Chinese version of MSPSS adapted from Zimet et al. [22], which was strictly validated by Qianjin Jiang et al. [23], with 12 items across 3 dimensions. The scale adopted a 7-point Likert format, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with a total score of 84 and with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived social support. It had a Cronbach’s α of 0.91 and a test-retest reliability of 0.85.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

To assess the levels of anxiety and depression of relatives, we used the Chinese version of HADS adapted from Zigmond et al. in 1983 [24], which was strictly validated by Ye Weifei et al. [25]. The HADS comprises 14 items, divided into an anxiety subscale (7 items) and a depression subscale (7 items). Each item is scored from 0 to 3, and the total score ranges from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety and depression. Relatives showing signs of anxiety or depression were identified by a total subscale score of 8 or above.

Data collection

Quantitative data

Data collection was carried out from July to September 2024. In the quantitative study, a non-probability consecutive sampling approach was employed. The investigators (TXJ and YLG) identified eligible patients. On the day the patient was transferred to the general ward, the investigators visited the wards, explained the purpose of the study and invited the relatives to participate. After obtaining the informed consent of the relatives, they signed the informed consent form. For any question, the researcher provided explanations to enable accurate responses. Additionally, for relatives with low educational attainment or writing difficulties, the researcher read the questionnaire aloud to assist them in completing the survey. Lastly, the completeness of the scale filling was verified on-site.

Qualitative data

To collect qualitative data, interview invitations were extended to relatives who had participated in the questionnaire survey. A purposive sampling selection was made, and the maximal variations in terms of demographic characteristics and caregiving experience were considered. An informed consent form was obtained from each interviewee. The interviews were mainly conducted by TXJ and were conducted within one week after the patient’s transfer to the general ward. The interview time was scheduled to avoid the interviewee’s treatment and rest periods, and the location was chosen in a quiet area of the ward, such as the demonstration classroom. The interview was audio recorded with the consent of the interviewee. For participants who were reluctant to be audio recorded, field notes would be adopted to document. These notes would be completed immediately during and after the interview and subsequently submitted to the participants for review so that they can make modifications as needed. To encourage interviewees to freely express their true thoughts and feelings, an open-ended and non-leading questioning approach was adopted. Field notes documented the interviewee’s facial expressions and body language, as well as the interviewer’s feelings and reflections.

Based on the results of the quantitative study, literature review, and discussions among team members, an interview guide was drafted and pre-interviews were conducted with two interviewees to further refine the guide. The finalized interview guide comprised the following main questions: (1) What problems and difficulties did you encounter during the period following ICU transfer? (2) What needs did you have during the period following ICU transfer? (3) How do you expect medical staff to assist you during the period following ICU transfer? (4) What do you think about receiving a family care manual? If provided, what content would you expect it to include? (5) Is there anything else you would like to share? Each interviewee lasted approximately 20–30 min. Data saturation was judged to have been reached when no new concepts, themes, or information emerged from the newly collected data, and when the data already collected were sufficient to answer the research questions as well as to achieve the research objectives.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

Quantitative data were organized using Microsoft Excel, and statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23. Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize the demographic characteristics and the needs subscale of the relatives. For continuous variables, if the distribution was normal or approximately normal, the mean and standard deviation were reported; otherwise, the median and interquartile range were calculated. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. A t-test and one-way analysis of variance were utilized to compare the total scores of RNSP-ICU across different demographic characteristics of relatives. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted using Fisher’s LSD tests to identify specific group differences. Spearman’s correlation analysis was adopted to explore the relationship between the total scores of HADS, FRSS, MSPSS, and RNSP-ICU.

Qualitative data

After each interview, the researcher (TXJ and YLG) transcribed verbatim and encoded to remove the identification information within 24 h. One of the participants declined audio recording, so the interviewers (TXJ and YLG) made detailed notes during the interview. The transcript was checked the accuracy before analysis and then stored and analysed in NVivo11 (QSR International, USA, 2015). Corresponding field notes were also attached to the transcribed text. The data were analysed using thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke [26]. The method involves the following 6 steps: (1) familiarizing yourself with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. In this study, TXJ read all the transcribed text repeatedly and completed the initial coding (steps 1 and 2). All authors (TXJ, HYL, CYS, YLG) collaboratively classified homogeneous codes as themes and organized them (steps 3 and 4). They discussed all the codes and themes in an online meeting to reach a consensus (step 5). Finally, TXJ summarized and formed the report (step 6).

Research team and reflexivity

The researchers were ICU nurses, critical care professors, and doctoral candidates in nursing, with a shared interest in this topic. All authors have clinical experience in the intensive care field and possess professional knowledge in qualitative research. Throughout the study, the researchers constantly kept writing reflective diaries. Researchers should not bring their preconceptions and experiences derived from clinical practice into the qualitative data analysis. To ensure the reliability and verifiability of qualitative data, a detailed audit trail was constructed to document each step of the data analysis process. In addition, a peer review process was conducted whereby researchers reviewed and provided comments on data collection, coding and interpretation.

Rigour and trustworthiness of qualitative data

To ensure rigor, this study strictly adhered to the qualitative guidelines [27]. To ensure consistency, the researcher (TXJ) conducted interviews with participants from beginning to end; he neither provided care in the research setting nor had any prior relationship with the study participants. Method triangulation using multiple data sources (including interview transcripts, field notes, and observation results) and researcher triangulation involving four or more researchers in the analysis process were utilized throughout the coding process. All codes and themes were peer-reviewed by all research members. Sample citations were drawn directly from the participants’ reports.

Integration of the quantitative and qualitative data

In this study, we compared, integrated and presented quantitative and qualitative results together. The quantitative data were systematically integrated first and then the qualitative data were handled in depth. The qualitative data from the interviews helped to explain and complement the quantitative findings and deepened the understanding of the key elements of the relatives’ needs.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the ethics committee of a hospital (No. KL20240743) and in strict adherence to the ethical principles articulated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed in detail about the purpose, confidentiality and voluntary nature before the study began, and all participants gave informed consent. They were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without providing reasons. Electronic data about the participants, including audio and textual material, etc., were stored on an encrypted server within the hospital. The data was de-identified and kept strictly confidential. Only the researcher could access the audio and text materials, which would be stored securely for five years. After the expiration date, it will be destroyed following relevant regulations.

Results

Quantitative results

Of the 187 relatives invited to participate, 168 (89.8%) completed the questionnaire. Seven questionnaires were removed due to obvious logical errors. A total of 161 questionnaires were utilized for the final analysis. 79 (49.1%) relatives were aged 36–50 years, 81 (50.3%) were female, 75 (46.6%) had middle/high school education, 130 (80.7%) had a partner to care for the patient together, and 85 (52.8%) had experience caring for patients. Notably, the incidence of depression among relatives was 45.3%, and the incidence of anxiety was 31.1%. Other sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relatives’ profile and its association with the need level

| Categories | Total score on RNSP-ICU | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | M(SD) | t/F | p value | ||

| Age | 3.807 | 0.026* | |||

| 18–35 years | 34(21.1%) | 95.29(12.37) | |||

| 36–50 years | 79(49.1%) | 88.86(15.36) | |||

| 51–75 years | 48(29.8%) | 87.52(15.98) | |||

| Sex | 0.409 | 0.683 | |||

| Male | 80(49.7%) | 90.31(14.86) | |||

| Female | 81(50.3%) | 89.33(15.54) | |||

| Marital status | 3.539 | 0.059 | |||

| Married | 129(80.1%) | 88.53(15.66) | |||

| Single | 26(16.2%) | 95.81(11.67) | |||

| Others | 6(3.7%) | 91.50(12.93) | |||

| Level of education | 12.724 | < 0.001* | |||

|

Primary school or below Junior/senior high school |

26(16.1%) 75(46.6%) |

80.23(16.32) 87.97(14.80) |

|||

| Junior college or above | 60(37.3%) | 96.28(12.20) | |||

| Profession | 2.133 | 0.079 | |||

| Government organization/enterprise employee | 31(19.3%) | 93.74(13.73) | |||

| Farmer/worker | 54(33.5%) | 86.02(14.29) | |||

| Retiree | 9(5.6%) | 91.67(19.44) | |||

| Freelance worker | 59(36.6%) | 89.76(16.03) | |||

| Student | 8(5.0%) | 98.63(8.43) | |||

| Place of residence | 0.948 | 0.344 | |||

| Urban area | 52(32.3%) | 91.46(15.24) | |||

| Rural area | 109(67.7%) | 89.04(15.14) | |||

| Monthly income per capita (yuan) | 1.891 | 0.133 | |||

| <3000 | 46(28.6%) | 85.87(15.86) | |||

| 3000–6000 | 74(46.0%) | 90.34(14.90) | |||

| 6001–9000 | 21(13.0%) | 94.33(13.08) | |||

| >9000 | 20(12.4%) | 92.25(15.50) | |||

| Relationship to patient | 1.298 | 0.296 | |||

| Parent | 26(16.1%) | 93.69(12.39) | |||

| Spouse | 28(17.4%) | 85.61(17.87) | |||

| Child | 86(53.4%) | 90.76(14.73) | |||

| Sibling | 6(3.7%) | 84.33(12.93) | |||

| Other | 15(9.3%) | 87.80(16.58) | |||

| Has a partner who also cares for the same patient | 0.782 | 0.435 | |||

| Yes | 130(80.7%) | 90.28(15.08) | |||

| No | 31(19.3%) | 87.90(15.65) | |||

| Has experience in caregiving | -2.834 | 0.005* | |||

| Yes | 85(52.8%) | 86.72(16.15) | |||

| No | 76(47.2%) | 93.29(13.25) | |||

| M(SD) | r | p value | |||

| The total score of HADS | 161 | 12.16(8.97) | 0.493 | < 0.001* | |

| The total score of FRSS | 161 | 65.31(8.11) | -0.325 | < 0.001* | |

| The total score of MSPSS | 161 | 66.32(8.95) | 0.094 | 0.237 | |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; HADS: hospital anxiety and depression Scale; FRSS: family relocation stress scale; RNSP-ICU: relatives’ needs scale during the patients in ICU transitional period; MSPSS: multidimensional scale of perceived social support

The total score of RNSP-ICU was (89.82 ± 15.17). The subscales with the highest score were (a) communication needs (4.42 ± 0.48), and need for caregiving skills (4.31 ± 0.72), followed by (b) information needs (4.04 ± 0.82), (c) emotional support (3.95 ± 1.15), and lastly (d) instrumental support (3.62 ± 1.07). With respect to the percentage of needs, among all the 22 items, only “Item 14: hope the nurse can organize a family care meeting” did not exceed 50%; the remaining items all exceeded 50% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Needs, means and SDs of the relatives’ needs scale during the patient’s ICU transitional period dimensions (n = 161)

| Items | Need n(%)a | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Need for caregiving skills | 4.31 ± 0.72 | |

| 1. Medical staff will tell me what situations require immediate notification of the medical staff | 150(93.1%) | 4.51 ± 0.79 |

| 2. Medical staff will tell me how to help the patient with daily care to make the patient comfortable, e.g. grooming, massage | 109(67.7%) | 3.88 ± 1.26 |

| 3. Medical staff will tell me how to help the patient with early functional exercises | 134(83.2%) | 4.17 ± 1.06 |

| 4. Medical staff will tell me the patient’s dietary precautions | 149(92.5%) | 4.48 ± 0.81 |

| 5. Medical staff will tell me the key points to focus on when caring for the patient at the bedside | 150(93.1%) | 4.52 ± 0.76 |

| Need for communication | 4.42 ± 0.48 | |

| 6. I am able to communicate with medical staff every day to understand the patient’s condition and care issues | 157(97.5%) | 4.71 ± 0.53 |

| 7. Doctors are able to communicate with me when there will be a change in the patient’s treatment plan | 160(99.4%) | 4.79 ± 0.45 |

| 8. The department will establish an information exchange group for the same kind of disease | 84(52.2%) | 3.31 ± 1.48 |

| 9. Medical staff are able to answer my questions truthfully | 157(97.5%) | 4.69 ± 0.59 |

| 10. The explanation given by medical staff is easy to understand | 153(95%) | 4.60 ± 0.58 |

| Instrumental support | 3.62 ± 1.07 | |

| 11. The food provided by the hospital canteen will be very palatable | 95(59%) | 3.52 ± 1.54 |

| 12. Two family members will be allowed to take care of the patient at the same time under certain special circumstances | 129(80.1%) | 4.24 ± 0.99 |

| 13. Medical staff will also be concerned about the health of family members | 111(69%) | 3.84 ± 1.41 |

| 14. The ICU nurse can organize a family caring meeting before transfer | 74(46%) | 3.05 ± 1.58 |

| 15. A manual for family care during the ICU transition period can be provided | 97(60.2%) | 3.47 ± 1.54 |

| Emotional support | 3.95 ± 1.15 | |

| 16. Medical staff will recognize the role that family members play in a patient’s recovery | 122(75.8%) | 3.97 ± 1.24 |

| 17. Medical staff can help me overcome my doubts and fears for the future | 113(70.1%) | 3.89 ± 1.32 |

| 18. Medical staff will encourage patients and families through sharing successful cases | 116(72%) | 4.00 ± 1.28 |

| Information needs | 4.04 ± 0.82 | |

| 19. Receive communication regarding the basic professional information about the doctors and nurses who are in charge of the patient in the general ward, such as their professional title and level of experience | 113(70.2%) | 3.90 ± 1.22 |

| 20. Receive communication regarding whether the patient’s current condition is suitable for transfer | 129(80.2%) | 4.22 ± 1.02 |

| 21. Before the patient is transferred out of the ICU, allow me to visit and learn about the general ward environment | 89(55.3%) | 3.43 ± 1.43 |

| 22. Receive communication regarding the patient’s next treatment strategy | 156(96.9%) | 4.63 ± 0.67 |

| Total score of all items | 89.82 ± 15.17 |

SD: standard deviation; ICU: intensive care unit

aNeed n(%): The number and percentage of family members who chose the options of “often needed” and “always needed”

Demographic variables such as age, level of education, and experience in caregiving were found to have statistically significant impacts on the total RNSP-ICU score (Table 2). The results indicated that relatives from a younger age group and those with a higher level of education were more likely to have more needs. A post-hoc LSD test demonstrated significant differences in scores between relatives aged 18–35 years and relatives from older age groups (a) 36–50 years (p = 0.048) and (b) 51–75 years (p = 0.001). In addition, relatives with primary school or below had significantly lower scores than those with higher educational experience (a) junior/senior high school (p < 0.001) and (b) junior college or above (p = 0.001). Furthermore, relatives without experience in caregiving and those who obtained higher total HADS scores had more needs. Relatives with lower total FRSS scores also exhibited more needs.

Qualitative results

Twelve participants completed the interviews, and their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 3. After the transcript content was analysed, the following six themes were identified: communication and access to information, caregiving guidance, emotional support, economic issues, information for a family care manual, and comfort of the environment.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic of data interview participants

| Categories | N |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–35 years | 3(25.0%) |

| 36–50 years | 6(50.0%) |

| 51–75 years | 3(25.0%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 5(41.7%) |

| Female | 7(58.3%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 8(66.7%) |

| Single | 3(25.0%) |

| Others | 1(8.3%) |

| Level of education | |

|

Primary school or below Junior/senior high school |

2(16.7%) 5(41.7%) |

| Junior college or above | 5(41.6%) |

| Profession | |

| Government organization/enterprise employee | 3(25.0%) |

| Farmer/worker | 4(33.3%) |

| Retiree | 1(8.3%) |

| Freelance worker | 3(25.0%) |

| Student | 1(8.3%) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban area | 2(16.7%) |

| Rural area | 10(83.3%) |

| Monthly income per capita (yuan) | |

| <3000 | 4(33.3%) |

| 3000–6000 | 6(50.0%) |

| 6001–9000 | 2(16.7%) |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Parent | 2(16.7%) |

| Spouse | 2(16.7%) |

| Child | 7(58.3%) |

| Sibling | 1(8.3%) |

| Has a partner who also cares for the same patient | |

| Yes | 11(91.7%) |

| No | 1(8.3%) |

| Has experience in caregiving | |

| Yes | 5(41.7%) |

| No | 7(58.3%) |

Theme 1: communication and information access

This was the most common theme. Most of the participants expressed their desire to have a detailed understanding of the patient’s condition status, treatment plan and disease prognosis. Furthermore, they hoped that medical staff would answer their queries truthfully and patiently to enhance the communication effect.

“Currently, our main need is that the physician conducting daily rounds provides us with comprehensive and detailed information regarding the patient’s condition, including any improvements observed and their extent. Furthermore, we want to know the overall treatment plan for the patient, as well as the forthcoming medication regimen and the intended effects of these medications.” (P3, Male, 48 years).

“Everyone says that recovery after surgery is essential. We want to know the next steps of treatment, how to manage his preexisting diabetes and how we can help promote his recovery… Will his bowel function be affected after this surgery?” (P6, Male, 38 years).

“We hope that the doctor can explain the patient’s disease and condition to us without reservation… they could be patient and provide clear explanations.” (P3, Male, 48 years).

Some participants expressed a desire to establish an information-sharing group focused on the same disease to facilitate access to information on the disease and precautions needed.

“I propose the establishment of a WeChat group for individuals with the same disease, where medical staff can share information regarding disease precautions and necessary supplies. We can flip through it at our convenience to avoid forgetting some important details.” (P5, Female, 22 years).

Theme 2: caregiving guidance

After the transfer to a transition unit, the burden of care was shouldered by the relatives. However, most interviewed participants lacked relevant knowledge and skills in caring and felt confused. Several participants stated, “We have no caregiving experience. We do not know how to properly and effortlessly turn the patient over, how often to turn the patient over, and how to change the care pads…” (P2, P3, and P8).

Some participants also expressed confusion about the operation and precautions regarding the medical equipment.

“What should be the normal range of the electrocardiogram monitoring? What do these numbers mean? Additionally, how should we operate this analgesic pump?” (P8, Female, 56 years).

Some participants would like the nurses to teach them basic rehabilitation exercises, such as body turns and ankle movements. (P1, Female, 62 years) Some participants wanted to know about the patient’s current position requirements, both during daily activities and when taking nasal feeds. (P1, Female, 62 years)

Some participants also expressed the need for the key points of observing the patient’s condition, “I hope that medical staff can tell me what to focus on and what situations require an immediate call to them.” (P1, Female, 62 years; P12, Female, 22 years).

Some participants were perplexed by the current dietary care for the patient, such as adjustments to the postoperative diet, control of fluid intake, and management of special disease diets. They would like to receive professional and detailed guidance.

“We want to know the fluid intake requirements for patients after cardiac surgery. Specifically, how should the water be properly allocated… to meet the patient’s needs regarding thirst and also to control the total amount effectively?” (P2, Male, 46 years).

“We are quite concerned about the impact of total gastrectomy on his diet and do not know how to arrange his diet scientifically, such as the appropriate number of meals per day, what kinds of food are suitable… we hope to receive professional guidance.” (P6, Male, 38 years).

Theme 3: emotional support

Faced with uncertainty, the severity of the illness, and the hardships of long-term care, some relatives developed negative emotions. They need emotional support and psychological guidance from medical staff.

“During this week, our moods have been fluctuating as the patient’s condition has changed. My husband, who is only in his fifties, had never anticipated such an accident. He suffered from heatstroke and fell from the elevated tower… All the family members are extremely anxious and cannot accept this.” (P9, Female, 52 years).

“We are so exhausted and overburdened in providing care and cannot sleep well at night either. We are a bit overwhelmed as this goes on over a long time. We are more upset and anxious… many things need to be done at home.” (P7, Male, 44 years).

Theme 4: financial burden

Owing to financial difficulties, some participants hoped that medical insurance could cover more expenses to alleviate the economic burden.

“The financial burden is our main problem and we hope that our health insurance will cover more expenses. The costs of treatment in ICU were very high and we are already heavily in debt. We can’t work currently because we need to stay here to care…” (P11, Male, 38years).

Theme 5: information for a family care manual

Some participants expressed the need for a family care manual, which could include specific disease care knowledge, the introduction and handling of potential complications, and operational instructions for medical devices. They expected the manual to improve their caregiving skills and reduce their dependence on medical staff.

“We need the manual, which can provide tailored guidance on the daily management and wound care of his burn injuries.” (P1, Female, 62 years).

“If the manual is available, I will read it carefully. For the content, we want to know about the knowledge pertinent to my mother’s illness (upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage), such as precautions for caregiving and key points for monitoring her status.” (P5, Female, 22 years).

“We anticipate that the manual could provide information on the postoperative care of cardiac surgery, including potential complications and standard treatment protocols. By acquiring this knowledge in advance, we can be prepared ourselves… Additionally, the manual could delineate the normal data range of instruments such as monitors, and instructions for medical equipment so that relatives can refer to it.” (P2, Male, 46 years).

Theme 6: comfort of environment

Some participants also raised specific demands regarding the comfort of the ward environment, including factors such as noise levels, light and accompanying facilities.

“We would like to change to a quieter and cleaner ward. The rooms here are too bright and noisy…” (P1, Female, 62 years).

“The single room only has a folding bed, and the other person has to sleep on a chair. If the sofa was converted into a double-use, adjustable one, it would increase the bed. The sofa in the rest area is tilted, and the light stays on at night… At 11 p.m. or 12 p.m., some relatives are still on the phone outside, and their conversation sounds are as noisy as in a vegetable market… They interfere with our sleep.” (P2, Male, 46 years).

Mixed-methods findings

The quantitative data found that the most important needs of families included ‘communication needs’, ‘need for caregiving skills’ and ‘information needs’, and these results were confirmed and supplemented by the qualitative data.

In terms of nursing skills, the qualitative findings further tapped into more detailed information that relatives wanted to learn various caregiving skills and know about the operation and precautions of medical equipment and current positional requirements, which supplemented the quantitative findings. Regarding diet, relatives also expressed more detailed information and wanted to know how to arrange diet and fluid intake scientifically and reasonably.

Several new themes emerged in this study, including financial burden, comfort of environment, and information for a family care manual, which complemented the quantitative findings. This study found that some family members were facing financial burden. At the same time, family members also raised demands regarding the comfort of the ward environment, including factors such as noise levels, light and accompanying facilities, and they expected improvements in these aspects. Some participants also affirmed the need for a family care manual and elaborated on what it should contain. More combined results from the quantitative and qualitative phases were presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Integration of quantitative and qualitative results

| Dimensions | Items | Need n(%)a | Qualitative Themes | Merging/Integrating results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for caregiving skills | 1. Tell me what situations arise that require immediate notification… | 150(93.1%) | Caregiving guidance |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Need for observation points. |

| 2. Tell me how to help the patient with daily care… | 109(67.7%) |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. More details: learn various caregiving skills; know how to operate and the precautions for specific medical equipment; current position requirements. |

||

| 3.…help patients with early functional exercises | 134(83.2%) |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Learn basic rehabilitation exercises. |

||

| 4.Tell me the patient’s dietary precautions | 149(92.5%) |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Dietary guidance: scientific and reasonable diet, control of fluid intake. |

||

| 5.Tell me the key points to focus on when caring… | 150(93.1%) |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Need for observation points. |

||

| Communication needs | 6.…know about the patient’s condition and care issues | 157(97.5%) | Communication and information access |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Know the status of the patient’s condition, treatment plan and disease prognosis in detail. |

| 7.…a change in the patient’s treatment plan | 160(99.4%) | |||

| 8.…establish an information exchange group for the same kind of disease | 84(52.2%) |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Establish an information-sharing group focused on the same disease. |

||

| 9.…answer my questions truthfully | 157(97.5%) |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Explain queries without reservation; be patient and provide clear explanations. |

||

| 10.The explanation…is easy to understand | 153(95%) | |||

| Instrumental support | 11.It is hoped that the food…will be very palatable | 95(59%) | ||

| 12.…two family members will be allowed to take care of the patient…. | 129(80.1%) | |||

| 13.…be concerned about the health of family members | 111(69%) | |||

| 14.…organize a family caring meeting before transfer | 74(46%) | |||

| 15.It is hoped that a manual for family care… | 97(60.2%) | Information for a family care manual |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. It complemented the quantitative findings. Some participants affirmed the need for a family care manual and elaborated on what it should contain. |

|

| Emotional support | 16.…recognize the role that family members play in a patient’s recovery | 122(75.8%) | ||

| 17.…help me overcome my doubts and fears for the future | 113(70.1%) | Emotional support |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Need for emotional support and psychological guidance. |

|

| 18.…medical staff will encourage patients and families… | 116(72%) | |||

| Information needs | 19.…know basic professional information about the doctors and nurses… | 113(70.2%) | ||

| 20.…know whether the patient’s current condition is suitable for transfer | 129(80.2%) | |||

| 21.…allow me to visit and learn about the general ward environment | 89(55.3%) | |||

| 22.…know the patient’s next treatment strategy | 156(96.9%) |

Confirmed by quantitative and qualitative results. Know the next steps in the treatment plan. |

||

| Financial burden | New information emerged in qualitative phase. | |||

| Comfort of environment | New information emerged in qualitative phase. |

aNeed n(%): The number and percentage of family members who chose the options of “often needed” and “always needed”

Discussion

The present study identified a relatively high overall level of needs among relatives during the transition period. The quantitative data indicated that the most important needs of relatives concerned communication, information, and care skills; these findings are complemented and explained by the qualitative data. The level of need was influenced by factors including age, educational attainment, caregiving experience, level of anxiety and depression, and level of relocation stress. These findings help address the growing but still limited literature regarding specific factors related to the needs of relatives of patients. The qualitative data also revealed other needs related to environmental comfort and financial burden. This knowledge is conducive to formulating targeted supportive care measures to fulfil the needs of relatives during the transition period.

During the transitional period, relatives exhibited a relatively high overall need level, which indicates that although relatives have diverse characteristics, there is universality in terms of specific needs. Among the subscales of the RNSP-ICU, “communication needs”, “need for caregiving skills” and “information needs” obtained the highest overall mean scores, which were complemented and explained by qualitative data. These findings are consistent with previous qualitative studies, where care guidance and information needs were the main concerns of relatives during the ICU transition period [7, 8, 11]. In this study, relatives were more concerned with the basic needs of patients than their own needs. Regarding communication and information needs, previous qualitative studies found that if relatives can obtain sufficient support and information, as well as participate in the care process, it will make them feel a sense of secure and professional care; they want to acquire numerous crucial pieces of information, such as medication, diet, treatment, and care plans, to prevent errors [11, 12]. However, some qualitative studies have found that relatives experienced information deficiencies during the transition period, which confused them and hindered the implementation of safe care [7, 11–13]. Thus, we recommend that ward managers support nurses in spending more time communicating with patients and relatives to establish connection and open bridges. In addition, as our results have shown, the introduction of mobile application communication platforms (e.g., WeChat) can effectively meet the diverse information needs of relatives and improve communication efficiency [8, 28].

In terms of nursing skills, both the qualitative and quantitative research findings indicate that relatives want to know the key points of the patient’s condition for observation, dietary guidance, and functional exercise. In China, influenced by traditional family values and other factors, relatives often want to be personally involved in the patient’s care process. The patient’s condition remains critical during the transitional period, which requires high-quality care; the number of nurses in general wards is smaller than that in ICUs, and they cannot provide one-on-one close monitoring like in ICUs; relatives recently transferred from the ICU to general wards also tend to lack caring experience and knowledge. Therefore, relatives were eager to obtain more professional guidance on caring skills to meet the patient’s caring needs. Recent qualitative studies have shown that relatives expect their caregiving role to be acknowledged and supported by medical staff during the transition period [11–13]. They hope to receive guidance and advice to enhance their caring skills needed to cope with the new situation and effectively assist their loved ones in the recovery process [7, 8, 11]. Specifically, our qualitative study revealed more detailed information that relatives wanted to learn various caregiving skills and know about the operation and precautions of medical equipment and current positional requirements, which supplemented the quantitative findings.

Several new themes emerged in our study, including financial burden and comfort of environment, which complemented the quantitative findings. A previous mixed study reported that due to high emotional stress or the need to accompany patients in the hospital, relatives were unable to work, thereby incurring a significant economic burden [29]. In a recent qualitative study, it was found that relatives hope to receive financial guidance, but most of them stated that they received little or no financial assistance during their hospital stays. They experienced bureaucratic hurdles in understanding their medical costs and insurance coverage, which left them stressed, distrustful and confused [30]. This suggests that medical staff can proactively offer comprehensive financial guidance services to relatives. Furthermore, they could actively communicate and coordinate with the hospital administration to simplify the relevant processes, such as expense inquiries and reimbursements. For special patients with financial difficulties, public welfare projects can be carried out to help alleviate their financial burden.

Meanwhile, relatives expressed a desire for improvements in noise levels, lighting, and accommodation in our study. Similar to caregivers working in other types of ICUs, participants mentioned comfort requirements regarding the ward environment, spatial layout, and infrastructure [7, 14, 29]. Such improvements are likely to increase relatives’ satisfaction [31]. Concerning information for a family care manual, this theme has seldom emerged in previous qualitative studies. A recent study has found that relatives reported that healthcare providers provided too much information, making it difficult for them to remember [8]. To better meet the information needs of relatives, providing relatives with a targeted and practical family care manual might be a feasible solution. This would transform professional knowledge into standardized written materials, covering various aspects of knowledge, and allowing family members to learn independently to enhance their knowledge level and long-term self-care abilities.

We found that relatives with higher levels of education exhibited higher levels of need. There are several possible explanations for this finding. On the one hand, it may be due to the fact that such relatives have a greater ability to understand disease and treatment knowledge explained by medical staff and are more willing to communicate actively with medical staff to obtain care information, thus exhibiting higher levels of need. On the other hand, this might be because those with lower educational attainment are more inclined to accept the existing situation rather than asking for changes according to their own wishes. Our study also revealed a higher level of need among younger relatives and those who lacked caregiving experience. When faced with ICU transition patients with complex, unstable conditions and high professional care needs, these inexperienced relatives may find it difficult to adapt; therefore, they are likely to need more support and assistance from medical staff. For the younger relatives, they may lack caregiving experience and have poorer coping skills and psychological resilience.

Our study found that relatives with higher levels of anxiety and depression exhibited higher levels of need. Notably, the incidence of anxiety and depression among relatives exceeded 30%, highlighting the urgency of addressing emotional needs, as also summarized in the qualitative interviews. This finding is consistent with those of previous qualitative research indicating that when faced with disease uncertainty, fluctuating conditions, and the hardships of long-term care, relatives are under great psychological pressure and emotional burden [8, 13, 32]. This may have increased their levels of need to some extent. In addition, relatives with higher levels of relocation stress exhibited higher levels of need. The reason for this may be that the uncertainty and unpredictability of ICU discharge make some relatives unprepared and uncertain about the care for the patient, which triggers anxiety and fear, resulting in increased stress levels and, consequently, increased levels of need. This suggests that we should pay more attention to these high-needs relatives and provide them with more care and assistance to relieve their psychological stress and meet their practical needs.

Our findings provide a solid foundation for implementing personalised needs interventions and optimising care management, and also offer a strong evidence base for meeting the needs of relatives more efficiently, e.g. know whether the current condition of the patient is suitable for transfer and the next treatment plan; allow two family members to care. The findings of this study further highlight the importance and urgency for medical staff to be proactive in responding to and meeting the personalized needs of relatives. Based on this, effective support programs for relatives need to be developed and transitional care models adapted to specific clinical settings need to be explored to ensure that high-quality healthcare services are provided to patients during the transitional period. The findings of this study will not only help medical staff to gain a deeper insight into the needs of relatives so that they can provide more attentive and precise medical services, but also help to promote the construction of a family-centered, high-quality healthcare service system.

Limitations

There are several potential limitations associated with our study. First, there is the possibility of subjective bias inherent in the self-report scale. Second, we investigated only the general ICU of a tertiary hospital in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, China, thus presenting a limitation in geographical extrapolation; given the differences in the division of caring responsibilities between Chinese and Western relatives during hospitalization, the findings of this study may not be applicable to groups of relatives in Western healthcare settings. Third, a purposive sample was used in this study, and despite our best efforts to ensure that the sample could comprehensively cover the relatives of intensive care patients with diverse characteristics, there was still a certain degree of selection bias. Fourth, the Cronbach’s α for some dimensions of the RNSP-ICU did not meet the standard value in this study. This may be associated with a limited sample size and needs to be verified in future research. Fifth, due to the influence of social expectations and Confucian culture, some relatives may have reservations about expressing their expectations. Finally, the exploration of the factors associated with the level of need is preliminary, indicating that further in-depth research is warranted in the future.

Conclusion

This study used a mixed-methods approach to explore the needs of relatives during the transition period in China. The quantitative data indicated that the most important needs of relatives concerned communication, information, and care skills, while the qualitative data complemented and explained the quantitative data. The qualitative data also revealed other needs related to environmental comfort and financial burden. The level of need was influenced by factors including age, educational attainment, caregiving experience, level of anxiety and depression, and level of relocation stress. This knowledge will help medical staff better understand relatives’ needs, and priority should be given to the implementation of tailored supportive care measures during the transition period, such as directing care skills, improving the comfort of the environment, and adopting multimodal communications and collaborative procedures.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all relatives for their support to this study. We would like to thank Ye Lei, the original RNSP-ICU scale developer, for his permission to administer the RNSP-ICU scale in our study.

Author contributions

Tiangxiang Jiang: Conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, data collection, data curation, writing–original draft, writing–review & editing. Yangling Ge: Methodology, data collection, resources, supervision, validation. Caiyan Su: Data curation, resources, supervision, validation, project administration. Hongyang Lu: data analysis, data curation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

All data for this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province (approval number: KL20240743) and in strict adherence to the ethical principles articulated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed in detail about the purpose, confidentiality and voluntary nature before the study began, and all participants gave informed consent. They were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without providing reasons.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tianxiang Jiang, Email: jia313315@163.com.

Caiyan Su, Email: sucy@enzemed.com.

Yangling Ge, Email: geyl@enzemed.com.

References

- 1.Du B, An Y, Kang Y, Yu X, Zhao M, Ma X, Ai Y, Xu Y, Wang Y, Qian C, et al. Characteristics of critically ill patients in ICUs in Mainland China. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mottaghi K, Hasanvand S, Goudarzi F, Heidarizadeh K, Ebrahimzadeh F. The role of the ICU liaison nurse services on anxiety in family caregivers of patients after ICU discharge during COVID-19 pandemic: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedrich O, Reid MB, Van den Berghe G, Vanhorebeek I, Hermans G, Rich MM, Larsson L. The sick and the weak: neuropathies/myopathies in the critically ill. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(3):1025–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerritsen RT, Hartog CS, Curtis JR. New developments in the provision of family-centered care in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(4):550– 553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li B, Yang Q. The effect of an ICU liaison nurse-led family-centred transition intervention program in an adult ICU. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(3):435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Q, Zhao L, Ye XC. Shortage of healthcare professionals in China. BMJ. 2016;354:i4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhan Y, Yu J, Chen Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Wan Y, Li S. Family caregivers’ experiences and needs of transitional care during the transfer from intensive care unit to a general ward: A qualitative study. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(2):592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu J, Wang H, Pei J, Meng J, Song Y. The dyadic coping experience of ICU transfer patients and their spouses: A qualitative study. Nurs Crit Care. 2024;29(4):672– 681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li T, Gong YL, Sha F, Dong X, Miao CX, Liu YL. The status quo and influencing factors of readiness of primary caregivers of patients transferred out from intensive care units. Chin Nurs Manage. 2018;18(10):1347– 1351. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodakowski J, Leighton C, Martsolf GR, James AE. Caring for family caregivers: perceptions of CARE act compliance and implementation. Qual Manag Health Care. 2021;30(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Op't Hoog S, Dautzenberg M, Eskes AM, Vermeulen H, Vloet LCM. The experiences and needs of relatives of intensive care unit patients during the transition from the intensive care unit to a general ward: A qualitative study. Aust Crit Care. 2020;33(6):526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gyllander T, Näppä U, Häggström M. Relatives’ experiences of care encounters in the general ward after ICU discharge: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meiring-Noordstra A, van der Meulen IC, Onrust M, Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Luttik ML. Relatives’ experiences of the transition from intensive care to home for acutely admitted intensive care patients-A qualitative study. Nurs Crit Care. 2024;29(1):117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amorim M, Alves E, Kelly-Irving M, Silva S. Needs of parents of very preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units: A mixed methods study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;54:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(2):92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage; 2017.

- 17.Ingham-Broomfield R. A nurses’ guide to mixed methods research. Australian J Adv Nurs. 2016;33(4):46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye Lei, Ye XH, Zhang AQ, Rui Q. Development of relatives’ needs scale during the patients in ICU transitional period: construction, validity and reliability testing. J Nurs Sci. 2021;36(18):35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic medicine 1976. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Oh H, Lee S, Kim J, Lee E, Min H, Cho O, Seo W. Clinical validity of a relocation stress scale for the families of patients transferred from intensive care units. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(13–14):1805–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Jing, Xiaoying Y. Reliability and validity test for Chinese version of the migration stress scale of family members among ICU patients. J Nurses Train. 2018;33(17):1552–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Q. Medical psychology. People’s Medical Publishing House; 2004.

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye Weifei, Junmian X. The application and evaluation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in comprehensive hospital patients. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 1993;2(3):17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JL, Adkins D, Chauvin S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(1):7120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox CE, Ashana DC, Riley IL, Olsen MK, Casarett D, Haines KL, O’Keefe YA, Al-Hegelan M, Harrison RW, Naglee C, et al. Mobile Application-Based communication facilitation platform for family members of critically ill patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(1):e2349666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell M, Dwan T, Takashima M, Beard K, Birgan S, Wetzig K, Tonge A. The needs of families of trauma intensive care patients: A mixed methods study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;50:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dotolo DG, Pytel CC, Nielsen EL, Im J, Engelberg RA, Khandelwal N. Financial hardship: A qualitative study exploring perspectives of seriously ill patients and their family. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;68(5):382–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eltaybani S, Ahmed FR. Family satisfaction in Egyptian adult intensive care units: A mixed-method study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;66:103060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rückholdt M, Tofler GH, Randall S, Buckley T. Coping by family members of critically ill hospitalised patients: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;97:40–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data for this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.