Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms are prevalent mental health issues among college students. Physical activity has been recognized as a potential protective factor. However, the mechanisms through which physical activity alleviates depressive symptoms remain unclear.

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the associations between physical activity, psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students. The mediating roles of psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility on these associations were also examined.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted with 1205 college students from four universities in Shanghai, China. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) were used to assess physical activity and depressive symptoms, respectively. Psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility were measured using the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory Short Form (MPFI-24). PROCESS macro models were used to analyze the mediating effects of psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility on the relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms.

Results

The results showed a significant negative correlation between physical activity and depressive symptoms (r = -0.15, p < 0.01). Psychological inflexibility played a partial mediation role in the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms (indirect effect: -0.24, 95% CI: -0.48 ~ -0.01). However, psychological flexibility did not mediate the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

The study suggested that psychological inflexibility partially mediated the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms among college students. Interventions targeting physical activity and psychological inflexibility may be effective strategies for lowering depressive symptoms in this population.

Keywords: Physical activity, Psychological flexibility, Depressive symptoms, College students, Mental health

Introduction

Depression is a common public health issue[1]. It is characterized by persistent sadness, loss of interest in daily activities, and feelings of hopelessness, and often accompanied by cognitive impairments and physical symptoms such as fatigue and sleep disturbances [2]. Globally, more individuals are affected by depression, with women disproportionately impacted [1]. In China, more than 90 million people experience depressive symptoms, and the prevalence of depression among Chinese college students has reached 23.8% in recent years [3]. College students are particularly vulnerable to depression due to the unique stressors they may face, including academic pressures, interpersonal conflicts, financial concerns, and the transition from adolescence to adulthood [4–6]. Such stressors, combined with the absence of robust mental health support systems, place this population at elevated risk for developing depressive symptoms [4–6]. Depression is linked with increased the risks of some mental illness and premature death [7, 8], and also impaired interpersonal, social functioning [1, 9]. Given the high prevalence of depression and the relatively low rates of diagnosis and treatment among college students, it becomes critical to investigate protective factors that may alleviate or prevent depressive symptoms in this population [10, 11].

Physical activity has been recognized as an effective non-pharmacological intervention for alleviating depressive symptoms [12–14]. A growing body of evidence suggests that regular engagement in physical activity and exercise can significantly reduce symptoms of depression [12], improve mood regulation [15], and enhance overall psychological well-being [16]. In addition, physical activity is associated with improved coping strategies, such as increased self-esteem, emotional resilience, and enhanced regulation of stress, which are particularly beneficial for college students [17]. Moreover, existing studies also suggested that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) seems to be more effective for reducing depressive symptoms [17, 18].

Recent evidence has showed the role of psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility in depression management [19]. Psychological flexibility, within the context of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), refers to the capacity to adaptively respond to varying situations, maintain a present-focused awareness, and engage in values-driven behavior, even when confronted with negative emotions or depressive thoughts [20]. Conversely, psychological inflexibility is defined as the stereotypical avoidance of rigid responses to stimuli that interfere with well-being and valued behaviors (e.g., unpleasant inner experiences), which often worsens depressive symptoms by preventing meaningful action [21, 22]. The theoretical framework of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) emphasizes the importance of psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility in mental health, particularly in depression management. The ACT indicates that psychological inflexibility is the basic cause of mental problems in the population and that increased psychological flexibility serves as a treatment for intervention [23–25]. Recent studies suggested that higher levels of psychological flexibility were associated with more effective coping strategies, while higher levels of psychological inflexibility exacerbated emotional distress, further contributing to the severity of depressive symptoms [26–28].

As a protective factor, participation in physical activity has been found to positively influence psychological mechanisms, such as psychological flexibility [29], thereby enhancing individuals’ ability to cope with stress and reduce depressive symptoms [30, 31]. Participation in higher level of physical activity helps individuals to divert their attention from negative thoughts and emotions and it was associated with lower level of psychological inflexibility [31]. More evidence suggests that regular and moderate physical activity can reduce levels of psychological inflexibility by enhancing adaptability to the external environment and improving social adjustment, willpower, and problem-solving skills [32, 33]. In contrast, individuals with higher levels of psychological inflexibility may struggle to engage with psychological benefits of physical activity, worsening their emotional and mental health outcomes [34, 35]. Therefore, it is possible that psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility may mediate the associations between physical activity and depression, which has not been investigated through the perspective of positive and negative mental health outcomes in previous studies.

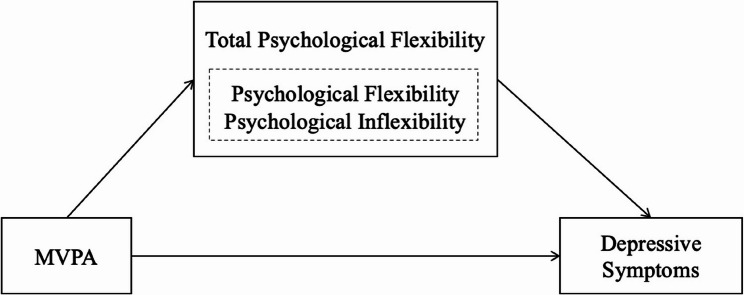

Taken together, the current study aimed to examine the associations between physical activity and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students, with a particular focus on the mediating roles of psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility. The theoretical hypotheses are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model

Materials and methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Shanghai, China, during the spring semester of 2024. College students from four universities were recruited using a snowball sampling method and completed an anonymous online survey. Initially, a total of 1250 participants responded and returned the questionnaires. After removing invalid responses due to regular answering patterns and incomplete data, 1205 valid questionnaires were included in the final analysis. Participants were undergraduate students (mean age = 19.84 ± 1.31, 57.8% females). Among them, 63.6% were freshman. 38.2% had a bachelor’s degree or higher in father’s education and 34.4% had a bachelor’s degree or higher in mother’s education.

The study adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Board for Human Research Protections of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. All participants provided informed consent after being informed of the purpose and procedures of the study.

Physical activity

Physical activity levels were self-reported using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) developed by Craig et al. and its Chinese version has demonstrated good validity and reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.72) in Chinese populations [36, 37]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the IPAQ-SF in this study was 0.70. IPAQ-SF measures physical activity over the previous seven days, including vigorous (e.g., heavy lifting, fast bicycling), moderate (e.g., bicycling at a regular pace, or doubles tennis), and walking activities lasting at least 10 min (e.g., During the last 7 da ys, on how many days did you do vigorous physical activities like aerobics, running, fast bicycling, or fast swimming in your leisure time.). The total moderate physical activity (MPA) and vigorous physical activity (VPA) was calculated separately by multiplying the number of days by the average time per day for each activity. The sum of MPA and VPA was then used to determine the total moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA).

Psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility

Psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility were measured using the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory Short Form (MPFI-24) developed by Rolffs et al. and its Chinese version (Cronbach’s α = 0.90 for psychological flexibility subscale and 0.89 for psychological inflexibility subscale) has been validated in Chinese populations [21, 38]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the MPFI-24 in this study was 0.90. It consists of two subscales (psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility), including 24 items (e.g., ‘I paid close attention to what I was thinking and feeling.’). Participants responded on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = “never true” to 6 = “always true”). Higher psychological inflexibility scores indicate greater psychological inflexibility, and lower psychological flexibility scores reflect reduced psychological flexibility.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) developed by Zhang et al. and it has been validated (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) in Chinese college students [39, 40]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the CESD-10 in this study was 0.74. The CESD-10 evaluates physical symptoms, depressive mood, and positive affect (e.g., ‘Had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing’), with responses scored on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were summarized for all variables. Normality was checked using skewness and kurtosis values. Spearman correlation analyses were used to assess the relationships between physical activity, psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, and depressive symptoms. Then, the associations between physical activity, psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, total psychological flexibility, and depressive symptoms were assessed using multiple linear regression analysis. The PROCESS macro (version 3.4) in SPSS was used to identify mediating effects of psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility and total psychological flexibility in the associations between physical activity and depression [41]. Indirect effects were estimated using bootstrapping with 5000 resamples, providing bias-corrected confidence intervals. The bootstrap test applies to parameters that are not normally distributed. The mediating effect was significant if the 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect did not include zero. All analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The statistical significance set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among MVPA, psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, total psychological flexibility and depressive symptoms. MVPA was negatively correlated with psychological inflexibility (r = −0.06, p < 0.01) and depressive symptoms (r = −0.15, p < 0.01), but it was positively corrected with correlated with psychological flexibility (r = 0.13, p < 0.01) and total psychological flexibility (r = 0.05, p < 0.05). Moreover, psychological flexibility was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = −0.17, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with psychological inflexibility (r = 0.13, p < 0.01) and total psychological flexibility (r = 0.78, p < 0.01). Psychological inflexibility demonstrated a positive correlation with total psychological flexibility (r = 0.66, p < 0.01) and depressive symptoms (r = 0.42, p < 0.01). Total psychological flexibility is positively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.13, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables

| Variables | Descriptive statistics and reliabilities | Correlations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | MVPA (hour/day) | Psychological Flexibility | Psychological Inflexibility | Total Psychological Flexibility | Depressive Symptoms | |

| MVPA (hour/day) | 0.45 | 0.63 | 6.64 | 70.77 | - | ||||

| Psychological Flexibility | 44.82 | 12.74 | −0.27 | −0.07 | 0.13** | - | |||

| Psychological Inflexibility | 35.44 | 10.52 | 0.64 | 0.99 | −0.06** | 0.13** | - | ||

| Total Psychological Flexibility | 80.27 | 18.37 | −0.36 | 1.75 | 0.05* | 0.78** | 0.66** | - | |

| Depressive Symptoms | 11.02 | 4.58 | 0.36 | 0.90 | −0.15** | −0.17** | 0.42** | 0.13** | - |

Notes: MVPA moderate-vigorous intensity physical activity; * P<0. 05, **P<0. 01

Associations between psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, total psychological flexibility and depressive symptoms

Table 2 shows the associations between the psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, total psychological flexibility and depressive symptoms. After controlling for demographic factors such as gender, age, grade, and parental education levels, psychological flexibility (β = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.06 ~ −0.02) and MVPA (β = −1.08, 95% CI: −1.49 ~ −0.67) were associated with lower level of depressive symptoms, while psychological inflexibility (β = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.16 ~ 0.21) and total psychological flexibility (β = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.03 ~ 0.06) were associated with higher level of depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Associations between Psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, total psychological flexibility and depressive symptoms

| Dependent Variable | Depressive Symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | LLCI | ULCI |

| Psychological Flexibility | −0.04** | −0.06 | −0.02 |

| Psychological Inflexibility | 0.18** | 0.16 | 0.21 |

| Total Psychological Flexibility | 0.04** | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| MVPA | −1.08** | −1.49 | −0.67 |

Notes: MVPA moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity, LLCI lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI), ULCI upper limit of the 95% CI; * P<0. 05, **P<0. 01

Associations between MVPA and psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility and total psychological flexibility

The associations between MVPA and psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility and total psychological flexibility are shown in Table 3. After controlling for demographic factors such as gender, age, grade, and parental education levels, MVPA was significantly associated with lower level of psychological inflexibility (β = −1.29, 95% CI: −2.25 ~ −0.33). However, the associations did not persist only between MVPA and psychological flexibility, but also between MVPA and total psychological flexibility (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Associations between psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, total psychological flexibility and depressive symptoms

| Predictors | MVPA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | β | LLCI | ULCI |

| Psychological Flexibility | −0.30 | −1.46 | 0.85 |

| Psychological Inflexibility | −1.29** | −2.25 | −0.33 |

| Total Psychological Flexibility | −1.59 | −3.26 | 0.08 |

Notes: MVPA moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity, LLCI lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI), ULCI upper limit of the 95% CI; * P<0. 05, **P<0. 01

Testing for mediation effects

As shown in Table 4, after controlling for gender, age, grade, and parental education levels, MVPA was inversely associated with depressive symptoms (direct effect: −1.08, 95% CI: −1.49 ~ −0.67, p < 0.001). However, psychological flexibility showed no indirect effect on the association between MVPA and depressive symptoms (p > 0.05). The paths between MVPA, psychological flexibility, and depressive symptoms are illustrated as shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Mediation analysis of psychological flexibility, psychological inflexibility, total psychological flexibility in the relationship between MVPA and depressive symptoms

| Effect Size | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | −1.07 | 0.21 | −1.48 | −0.66 |

| Psychological Flexibility | ||||

| Direct Effect | −1.08 | 0.21 | −1.49 | −0.67 |

| Indirect Effect | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.08 |

| Psychological Inflexibility | ||||

| Direct Effect | −0.83 | 0.19 | −1.20 | −0.47 |

| Indirect Effect | −0.24 | 0.12 | −0.48 | −0.01 |

| Total Psychological Flexibility | ||||

| Direct Effect | −1.00 | 0.21 | −1.41 | −0.59 |

| Indirect Effect | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.19 | 0.06 |

Notes: SE Standard Error, LLCI lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI), ULCI upper limit of the 95% CI

Fig. 2.

Mediation Model Illustrating the Indirect Effects of Psychological Flexibility on the Relationship between MVPA and Depressive Symptoms. Notes: MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity; ***P<0. 001

After controlling for covariates, MVPA was inversely associated with depressive symptoms (direct effect: −0.83, 95% CI: −1.20 ~ −0.47, p < 0.001). MVPA also had a significant indirect effect on depressive symptoms (indirect effect: −0.24, 95% CI: −0.48 ~ −0.01) among college students through psychological inflexibility. The mediation model in Fig. 3 illustrates the indirect effects of psychological inflexibility on the relationship between MVPA and depressive symptoms.

Fig. 3.

Mediation Model Illustrating the Indirect Effects of Psychological Inflexibility on the Relationship between MVPA and Depressive Symptoms. Notes: MVPA, moderate-vigorous intensity physical activity; **P<0. 01, ***P<0. 001

After controlling for covariates, MVPA was inversely associated with depressive symptoms (direct effect: −1.00, 95% CI: −1.41 ~ −0.59, p < 0.001). However, total psychological flexibility showed no indirect effect on the association between MVPA and depressive symptoms (p > 0.05). Figure 4 presents the mediation model showing the indirect effects of total psychological flexibility on the relationship between MVPA and depressive symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Mediation Model Illustrating the Indirect Effects of Total Psychological Flexibility on the Relationship between MVPA and Depressive Symptoms. Notes: MVPA, moderate-vigorous intensity physical activity; **P<0. 01, ***P<0. 001

Discussion

This study investigated the potential mediating roles of psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility in the associations between physical activity and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students. The results showed that psychological inflexibility partially mediated the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms, whereas psychological flexibility did not demonstrate a significant mediating effect. These findings suggest that the beneficial effects of physical activity on depressive symptoms may be partly due to the reduction of psychological inflexibility.

Previous studies have highlighted the role of psychological flexibility in emotional regulation and stress resilience [26]. Kashdan and Rottenberg demonstrated that psychological flexibility facilitated adaptive responses to stress and improves emotional well-being [26]. Similarly, Gloster et al. suggested that interventions aimed at enhancing psychological flexibility could significantly reduce depressive symptoms over time [42]. However, in this study, physical activity was not associated with psychological flexibility, and total psychological flexibility score and the score of psychological flexibility subscale did not significantly mediate the associations between MVPA and depressive symptoms among college students. One explanation for the non-significant mediating effects is that psychological flexibility may require more intensive psychological interventions, such as structured therapy, to induce meaningful changes [43, 44]. According to the ACT model, psychological flexibility involves complex cognitive and emotional regulation processes that may not be easily altered by physical activity alone [23, 24].

Interestingly, the current study demonstrated that the score of psychological inflexibility subscale partially mediated the association between MVPA and depressive symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, these results provided the first line of evidence that the beneficial effects of physical activity on depressive symptoms may be partly mediated by the reduction of psychological inflexibility. These findings are consistent of that higher level of physical activity was associated with lower level of psychological inflexibility [31], and further worsening their emotional and mental health outcomes [34, 35]. The findings not only supported the beneficial role of physical activity in lowering depressive symptoms, but also extended the literature by showing the mediating role of psychological inflexibility. However, more studies are needed to confirm the findings in a larger sample of participants. These findings have important practical implications, especially for mental health interventions targeting college students. Interventions that combine physical activity with strategies to reduce psychological inflexibility, such as ACT-based approaches, could be particularly effective in alleviating depressive symptoms [45]. Higher education institutions should consider integrating physical activity programs with psychological interventions aimed at reducing psychological inflexibility [46]. For example, combining physical activity programs with mindfulness training or emotional regulation strategies may be beneficial for college students experiencing academic stress and emotional challenges [47].

Although this study was among the first studies investigating the mediating roles of psychological flexibility in the associations of physical activity and mental health, it also has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits its potential to make causal inference. A reverse causality may exist in the observed associations. Future studies should adopt longitudinal study designs to better understand the dynamic processes of how changes in physical activity, psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility influence depressive symptoms over time. Second, this study collected self-reported data on physical activity, which may introduce response bias. Future studies could employ device-based measures such as accelerometers to obtain objective data. Additionally, this study did not screen for psychopathology (e.g., exercise addiction) when assessing the protective effects of MVPA, which may be related to psychological inflexibility. Future studies should incorporate behavioral addiction assessments when exploring the relationship between MVPA and psychological inflexibility. Finally, this study was conducted among college students, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations. More studies are needed to replicate these results in more diverse populations and examine potential cultural or regional differences in the relationships among physical activity, psychological flexibility, and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

This study indicated that psychological inflexibility partially mediated the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms among college students. Psychological flexibility did not mediate the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms. Interventions targeting physical activity and psychological inflexibility may be effective strategies for lowering depressive symptoms in this population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for participating in the study. The authors also thank Dandan Liu, Jian Liu and coauthors for providing the Chinese version of MPFI-24.

Authors’ contributions

XD: Writing– original draft, Writing– review & editing, Supervision, Validation, Project administration, Resources, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. EC: Writing– review & editing, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. YL: Writing– review & editing, Writing– original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. TC: Writing– original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. TCT: Writing– original draft, Writing– review & editing, Resources. QG: Writing– review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Resources. TH: Writing– review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Resources. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was no foundation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Board for Human Research Protections of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (approval number: H2022225I). All participants provided informed consent after being informed of the purpose and procedures of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thapar A, Eyre O, Patel V, Brent D. Depression in young people. Lancet. 2022;400(10352):617–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Zhang N, Bao G, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei XY, Xiao LM, Liu YN, Li YM. Prevalence of depression among Chinese University Students: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acharya L, Jin L, Collins W. College life is stressful today - Emerging stressors and depressive symptoms in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2018;66(7):655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamaideh SH. Stressors and reactions to stressors among university students. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(1):69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(3):391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from disease control priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1672–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365(9475):1961–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, et al. Major depressive disorder. Nature Rev Dis Prim. 2016;2(1):16065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein BI, Carnethon MR, Matthews KA, et al. Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder predispose youth to accelerated atherosclerosis and early cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(10):965–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apóstolo J, Bobrowicz-Campos E, Rodrigues M, Castro I, Cardoso D. The effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in older adults with depressive disorders: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;58:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrick RE, Dickinson RA, Gentry MT, et al. Treatment resistant late-life depression: A narrative review of psychosocial risk factors, non-pharmacological interventions, and the role of clinical phenotyping. J Affect Disord. 2024;356:145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(18):1203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Hendrikse J, Sabiston CM, Stubbs B. Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;107:525–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malm C, Jakobsson J, Isaksson A. Physical Activity and Sports-Real Health Benefits: A Review with Insight into the Public Health of Sweden. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(5):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, et al. Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Bmj. 2024;384:e075847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang D, Yang M, Bai J, Ma Y, Yu C. Association between physical activity intensity and the risk for depression among adults from the national health and nutrition examination survey 2007–2018. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:844414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCracken LM, Buhrman M, Badinlou F, Brocki KC. Health, well-being, and persisting symptoms in the pandemic: What is the role of psychological flexibility? J Contextual Behav Sci. 2022;26:187–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson KG. The ACT matrix: A new approach to building psychological flexibility across settings and populations. New Harbinger Publications; 2014;1–246.

- 21.Rolffs JL, Rogge RD, Wilson KG. Disentangling Components of Flexibility via the Hexaflex Model: Development and Validation of the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI). Assessment. 2018;25(4):458–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther. 2011;42(4):676–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes SC, Levin ME, Plumb-Vilardaga J, Villatte JL, Pistorello J. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013;44(2):180–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bluett EJ, Homan KJ, Morrison KL, Levin ME, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety and OCD spectrum disorders: an empirical review. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(6):612–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):865–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arslan G, Allen KA. Exploring the association between coronavirus stress, meaning in life, psychological flexibility, and subjective well-being. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27(4):803–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fonseca S, Trindade IA, Mendes AL, Ferreira C. The buffer role of psychological flexibility against the impact of major life events on depression symptoms. Clinical Psychologist. 2020;24(1):82–90. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arslan G, Yıldırım M, Tanhan A, Buluş M, Allen KA. Coronavirus stress, optimism-pessimism, psychological inflexibility, and psychological health: psychometric properties of the coronavirus stress measure. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021;19(6):2423–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo J, Huang X, Zheng A, et al. The influence of self-esteem and psychological flexibility on medical college students’ mental health: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:836956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Shen Q, Wang S, Liu Y, Wang Z, Bai C, Zhang T. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caponnetto P, Casu M, Amato M, et al. The effects of physical exercise on mental health: from cognitive improvements to risk of addiction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Alcaraz-Ibáñez M, Sicilia Á, Burgueño R. Social physique anxiety, mental health, and exercise: analyzing the role of basic psychological needs and psychological inflexibility. Span J Psychol. 2017;20:E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uğur E, Kaya Ç, Tanhan A. Psychological inflexibility mediates the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and psychological vulnerability. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(9):4265–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gloster AT, Meyer AH, Lieb R. Psychological flexibility as a malleable public health target: Evidence from a representative sample. J Context Behavior Sci. 2017;6(2):166–71. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2003;35(8):1381–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan M, Lyu J, He P. Chinese guidelines for data processing and analysis concerning the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi=Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2014;35(8):961–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu DD, Liu J, Shen XX, Hou CX, Xue C, Tang L. Validity and reliability of the simplified mutidimensional psychological flexibility inventory. Chin Ment Health J. 2023;37(06):538–44. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Wu ZY, Fang G, Li J, Han BS, Chen ZY. Development of the Chinese age norms of CES-D in urban area. China J Health Psychol. 2010;24(02):139–43. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang GQ, Bai H, Zeng GQ. Effect of supervisor-student relationship on depression in college students: Chain mediating effect. China J Health Psychol. 2023;31(01):129–34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Res Methods Instruments Comput. 2004;36(4):717–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gloster AT, Klotsche J, Ciarrochi J, et al. Increasing valued behaviors precedes reduction in suffering: Findings from a randomized controlled trial using ACT. Behav Res Ther. 2017;91:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arntz A, Stupar-Rutenfrans S, Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P. Prediction of treatment discontinuation and recovery from borderline personality disorder: results from an RCT comparing schema therapy and transference focused psychotherapy. Behav Res Ther. 2015;74:60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng Q, Zhang QL, Du Y, Ye YL, He QQ. Associations of physical activity, screen time with depression, anxiety and sleep quality among Chinese college freshmen. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan AJ, Jorm AF. Self-help interventions for depressive disorders and depressive symptoms: a systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2008;7:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dudley D, Okely A, Pearson P, Cotton W. A systematic review of the effectiveness of physical education and school sport interventions targeting physical activity, movement skills and enjoyment of physical activity. Eur Phys Educ Rev. 2011;17(3):353–78. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chacón-Cuberos R, Olmedo-Moreno EM, Lara-Sánchez AJ, Zurita-Ortega F, Castro-Sánchez M. Basic psychological needs, emotional regulation and academic stress in university students: a structural model according to branch of knowledge. Stud Higher Educ. 2021;46(7):1421–35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.