Abstract

Introduction

Triage is a system of ranking sick or injured persons according to their severity. Its data is critical for evidence-based action. The aim of this study was to assess the quality and completeness of emergency department triage tool in three tertiary Ethiopian public hospitals.

Method

This study utilized a multicenter cross-sectional design with sample size estimation calculated using a single population proportion formula. Data were collected from multiple sites and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25. All statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate the completeness of triage documentation.

Result

In a review of 450 client charts from three tertiary hospitals providing acute care, the completeness of triage data varied. Patient name, age, and gender were documented with a completeness of 79.1 %, 77.5 %, and 70.8 %, respectively. The cumulative analysis of the triage early warning score showed, highest recorded completeness was for heart rate (98.4 %), followed closely by respiratory rate (96.0 %). However, significant discrepancies were noted in other areas, such as systolic blood pressure, which had an overall completeness of 87.7 %. Temperature assessment was notably poor, with a cumulative completeness of only 59.3 %. Other parameters, including mobility and AVPU/CNS assessments, showed completeness of 86.4 % each.

Conclusion

This study identifies significant inconsistencies in triage documentation completeness across three Ethiopian hospitals, highlighting an urgent need for interventions. Standardized triage scales and continuous professional development focusing on documentation are crucial to enhance patient safety and optimize care delivery.

Keywords: Triage tool completeness, Emergency severity index, Triage early warning score

African Relevance.

-

•

Globally, emergency care is still developing compared to other medical fields, and emergency health systems are expanding across Africa.

-

•

Triage is one of the older practices in emergency medicine, but its application in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) remains limited.

-

•

The African healthcare system struggles with resource scarcity, particularly in emergency departments.

-

•

Many deaths in LMIC emergency rooms occur within the first 24 h of presentation, and recognizing very ill or injured patients early can lead to timely lifesaving interventions.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Triage is a system of sorting patients according to need when resources are insufficient for all to be treated at the same time; in addition, it’s a method of ranking sick or injured people according to their severity. It serves as a method for directing the appropriate patient to the right location at the right time for the right reason. To do so, there is a need to do a brief clinical assessment that determines the clinical urgency of the emergency category stated. Triage is a rather old medical procedure that has been around since the 18th century; however, its use in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is restricted. Triaging is not only limited to routine health facility emergency service but also being practiced in the field of disaster as well as military medicine, even though the objective and principle are slightly differing [1,2].

As it is the fact that most emergency rooms of LMIC deaths occur within the first 24 h of presentation, many of these deaths could be prevented if very sick and injured patients were identified and appropriate lifesaving treatment started immediately upon their arrival. This can be ensured by rapid triage for all patients presenting to the hospital in order to determine whether any priority signs are present and provide appropriate emergency treatment. A comprehensive emergency triaging system comprises a visual assessment of the patient’s situation, taking a brief triage history, and performing a focused physical examination to determine the appropriateness of acuity. Effective triaging includes strong evaluation ability, and quick and decisive judgment skills of the triage officer. To achieve its objective, a triage system has to have operating procedures, standards, and infrastructure, and one of its key tools is a triage format [[3], [4], [5], [6]].

The triage system varies from one health institution to the next based on available medical services, community needs and the load of the emergency department, but the primary objective of triaging remains the same [7].

Emergency care is in its infancy in comparison to other specialties in most of the world, and emergency health systems are developing throughout Africa, including Ethiopia. Ethiopia is a LMIC African nation that has committed to strengthening emergency care systems [[8], [9], [10]].

Ethiopia is one of the oldest nations, with an estimated population of >120 million, has fewer than 100 emergency medicine and critical physicians and <250 emergency nurses as of 2022. On top of limited human resources, the country has scarce and inadequate acute care infrastructure [11].

The triage related statistics are important scientific information that should be available for the constant evaluation of emergency services and continuous quality improvement of triage, morbidity, mortality, and reducing Emergency Department (ED) overcrowding [6]. Currently, there is a lack of evidence concerning the quality and completeness of triage data in LMIC, particularly within the context of Ethiopia.

This study was conducted in public tertiary hospital ED’s in Ethiopia. This study aimed to assess the quality and completeness of emergency department triage tool in three Ethiopian Public hospitals. This study could provide scientific data on triage systems for hospital management, policymakers, and the scientific community as a whole.

Methods

The study was carried out from September 1, 2022, to October 30, 2023, in the EDs of three tertiary public hospitals in Ethiopia. To ensure the anonymity of the hospitals involved in the study, we referred to them as A, B and C. Data collection took place from October 1 to October 5, 2022. These hospitals' ED serve as teaching institutions and provide tertiary care for over 40,000 critically ill patients annually, with the triage process primarily managed by nursing staff and nurse-led in their ED’s [[12], [13], [14]]. To conduct this survey multicenter cross-sectional study design was used. All client charts from the selected hospitals during the study period constitute the source population. The study population were patient's chart served in study areas in study period. All charts of ED served patients during study period were reviewed. Patients’ chart with no triage paper, and age below 12 were excluded. Given the absence of prior research in a similar setting, the sample size was estimated using a single population proportion formula. Assuming a minimum prevalence of 50 % for triage format completeness, a 95 % confidence level, and a 5 % margin of error, the calculated sample size was 384 charts. To ensure representativeness and proportionate data distribution across the three study areas, a decision was made to collect 150 charts from each study area, resulting in a total sample size of 450 charts. In each of the three hospitals, an initial chart was selected using a lottery method. This involved placing all available client charts into a container and randomly drawing one chart at a time. After the initial chart was drawn, subsequent selections were made using a systematic sampling approach. This involved establishing a sampling interval based on the total number of available charts in each hospital. To implement this method, we calculated the sampling interval (k) as follows:

The selection continued in this systematic manner until a total of 150 charts had been collected across all three hospitals. Therefore, based on the available charts for each study area, the sampling interval (k) values are set at every 3 intervals for A and B, while for C, the interval is every 2.

Experts developed two structured checklists to assess the completeness of triage documentation, tailored to the triage formats used at the study sites. A utilized the modified emergency severity index, while B and C followed the adapted South African triaging scale. Each checklist was aligned with the specific emergency triage tools of the three hospitals, with items scored to ensure internal consistency. Prior to full-scale data collection, a pilot test was conducted to evaluate the clarity, comprehension, and efficiency of the checklists. Feedback from the pilot test informed necessary revisions, ensuring the optimization of the data collection instrument. Trained research assistants, each holding a minimum of a Bachelor of Science degree in a health-related field, were responsible for data extraction from patient charts. All research assistants underwent comprehensive training on the utilization of the data collection tool to ensure consistency and accuracy in data collection. Descriptive analysis of the data was conducted. All the statistical analyses were performed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 25).

Prior to enrollment, all research staff participated in human subjects’ protection training to ensure data confidentiality for all study participants. Local staff were involved as facilitators were trained in line with Ethiopian ministry of health research data management standards. The consultant was ensuring compliance with ethics through site visits and ongoing training and communication. The quality control procedures included the following: All fields are completed with participant data; if no data was available, this is specified. Random checks by implementation staff on completion of data forms and adherence to the protocol. All data were stored within the encrypted software on encrypted computers. The study was conducted in compliance with the applicable regulatory requirements in Ethiopia. Quality assurance site visits were conducted by the study team, to ensure compliance with applicable regulations and ethical standards regarding protocol compliance, eligibility verification, source documentation collection and maintenance, and data collection form completion, as necessary. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College, and permission has also been granted from the other two study sites following their review of the IRB and research proposal. All study forms were identified with only the study ID. Data were not obtained directly from patients. No vulnerable populations were directly involved in the investigation.

Results

For logical explanation, the study findings are divided into three sub-headings: pre-triage variables (name, age, gender, address, date, and time of patient arrival, prehospital treatment information, mode of transportation, referred institution, chief complaint, allergy, and past medical history), triage score variables (triage early warning scores), and triage tool disparity.

Pre-triage variables

The completeness of socio-demographic data, which includes the patient's name, age, and gender, was measured at 79.1 %, 77.5 %, and 70.8 %, respectively. The documentation of patient names was the lowest in study area C, where it reached only 40.7 %. In the same hospital, gender and age records were also low, at 39.3 % and 35.3 %, respectively.

Regarding data completeness for patient arrival date and time, the completion rates were 96.8 % and 88.8 %, respectively, with similar rates observed across the three institutions for arrival dates. However, the documentation of patient addresses was notably lower, at only 63.3 % overall. Among the institutions, B reported the highest address completion rate at 92.7 %, while C had the lowest at just 31.3 %. Prehospital care information was documented in an average of 47.7 % of cases, with a minimum of 6 % and a maximum of 80 %. The mode of transportation was recorded in approximately 88.8 % of instances. The chief complaint appeared in 90.2 % of the triage documents analyzed, achieving 100 % completeness only in C. Past medical history was documented in 15.5 % of cases, with the lowest frequency at 4 % and the highest at 42 %. Allergy history was recorded for 29.3 % of patients, with a peak documentation rate of 78.7 %. Information regarding referring institutions was recorded in 93.7 % of cases, and all data from the institutions were consistent (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Completeness of Socio-Demographic and Pre-Hospital Clinical Data Among Patients Triaged in Adult Emergency Departments of Selected Teaching Hospitals in Ethiopia, October 1–5, 2022.

| S. No. | Variables | A N = 150 ( %) | B N = 150 ( %) | C N = 150 ( %) | Cumulative N = 450 ( %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Complete patient name | 150 (100) | 145 (96.7) | 61 (40.7) | 356(79.1) |

| 2. | Gender | 145 (96.7) | 145 (96.7) | 59 (39.3) | 349 (77.5) |

| 3 | Age | 127 (84.7) | 139 (92.7) | 53 (35.3) | 319 (70.8) |

| 4. | Date of arrival | 150 (100.0) | 147 (98.0) | 139 (92.7) | 436 (96.8) |

| 5. | Time of arrival | 138 (92.0) | 147 (98.0) | 115 (76.7) | 400 (88.8) |

| 6. | Address area | 99 (66.0) | 139 (92.7) | 47 (31.3) | 285 (63.3) |

| 7. | Pre-hospital treatment information | 9 (6.0) | 86 (57.3) | 120 (80.0) | 215 (47.7) |

| 8. | Mode of transportation | 125 (83.3) | 139 (92.7) | 136 (90.7) | 400 (88.8) |

| 9. | Chief complaint | 122 (81.3) | 134 (88.7) | 150 (100) | 405 (90.2) |

| 10. | Past medical history | 63 (42.0) | 6 (4.0) | 1 (7.0) | 70 (15.5) |

| 11. | Allergy history | 13 (8.7) | 118 (78.7) | 1 (7.0) | 132 (29.3) |

| 12. | Referring institution | 137 (91.3) | 139 (92.7) | 146 (97.3) | 422 (93.7) |

Triage score variables

In relation to the triage early warning score, the component with the lowest recording is temperature, which was documented in only 59.3 % of cases cumulatively. Notably, in one of the study areas (A), this figure dropped to just 6.7 %. The second lowest recorded measurement was blood pressure in C, where it was recorded at only 66 %.

Because the triage early warning score is derived using all of the components, missing one component makes it extremely difficult to categorize the patient during triage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Completeness of triage early warning score documentation among patients triaged in the adult emergency departments of selected teaching hospitals in Ethiopia October 1-5, 2022.

| S. No. | Variable | A N ( %) |

B N ( %) |

C N ( %) |

Cumulative N ( %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | HR | 148 (98.7) | 147 (98.0) | 148 (98.7) | 443 (98.4) |

| 2. | RR | 140 (93.3) | 148 (98.7) | 144 (96.0) | 432 (96.0) |

| 3. | Systolic BP | 146 (97.3) | 150 (100) | 99 (66.0) | 395 (87.7) |

| 4. | Temperature | 10 (6.7) | 138 (92.0) | 119 (79.3) | 267 (59.3) |

| 5. | Mobility | 106 (70.7) | 145 (96.7) | 138 (92.0) | 389 (86.4) |

| 6. | AVPU/CNS | 106 (70.7) | 144 (96.0) | 139 (92.7) | 389 (86.4) |

| 7. | Trauma | 103 (68.7) | 144 (96.0) | 137 (91.3) | 384 (85.3) |

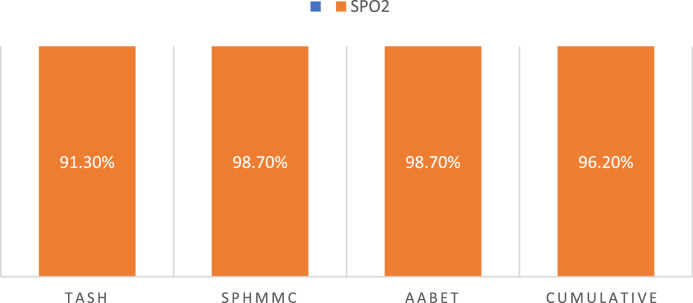

The evaluation of saturation status varies among the three study sites. At A, saturation is incorporated into the triage early warning score. Conversely, at B and C, saturation is documented separately from the early warning score but remains a consideration in patient management. Fig. 1 illustrates the completeness of patient oxygen saturation data.

Fig. 1.

Oxygen saturation documentation data completeness of patients triaged in adult emergency departments of selected tertiary teaching hospitals in Ethiopia, between October 1 to October 5, 2022.

Random blood sugar testing is a component of all institutions' triage scale; however, it is optional and only required for diabetic patients and patients with impaired mental status. Because the triage format does not contain diabetes and altered mental status diagnoses, hence we omitted the specific data because its completeness is going to be less informative.

The triage score is mentioned in 67.3 % of triage papers, the least found to be from C, which accounts for 31.3 %, while the triage category accounts for 97.3 % and is almost similar in all three hospitals (Table 3).

Table 3.

Completeness of triage documentation—specifically triage score, triage category, treatment provided, investigations ordered, name of triage officer, and officer's signature—among patients triaged in the adult emergency departments of selected teaching hospitals in Ethiopia, October 1 - 5, 2022.

| S. No. | Variable | A N ( %) |

B N ( %) |

C N ( %) |

Cumulative N ( %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Triage score | 144 (96.0) | 112 (74.7) | 47 (31.3) | 303 (67.3) |

| 2. | Triage category | 144 (96.0) | 145 (96.7) | 149 (99.3) | 438 (97.3) |

| 3. | Triage treatment | 14 (9.3) | 43 (28.7) | 5 (3.3) | 62 (13.7) |

| 4. | Triage investigation | 6 (4.0) | 43 (28.7) | 5 (3.3) | 54 (12.0) |

| 5. | Officer name | 89 (59.3) | 145 (96.7) | 145 (96.7) | 379 (84.2) |

| 6. | Officer signature | 142 (94.7) | 144 (96.0) | 141 (94.0) | 427 (94.8) |

Triage room patient treatment is least mentioned in the triage paper and accounts for 13.7 % of the time, both A and C hospital accounts for lower records 9.3 % and 3.3 % respectively. Similarly, the triage investigation is only mentioned in 12 % of the case, and it is least recorded for both A (4 %) and C (3.3 %). The lowest record of officer name was seen in A at 59.3 %, and the officer signature is nearly similar in all three hospitals, which is cumulatively 94.8 % (Table 3).

Triage system disparities

In the study areas, two different triage systems are in use. One location (A) includes two additional data variables in its triaging tool. In contrast, the other two sites (B and C) utilize a similar triage system that has been adapted from the South African triaging scale, incorporating four additional data variables unique to those institutions, one derived from the South African scale and three specifics to the institutions themselves, as illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Variations in Triage Systems Among Adult Emergency Departments of Selected Tertiary Teaching Hospitals in Ethiopia (October 1–5, 2022).

| Study area | Triage data components unique to study area | Data completeness N = 150 |

|---|---|---|

| A | Patient disposition from triage | 11(7.3 %) |

| Decision time of triage | 135(90 %) | |

| B | Other clinical determinant (conditions like current seizure, face burn or inhalation, hypoglycemia, acute shortness of breath, uncontrolled hemorrhage, coughing blood, chest pain, acute psychosis, poisoning/overdose, pregnancy with abdominal trauma, etc.) | 0(0 %) |

| Overall illness duration | 0(0 %) | |

| Contact address | 8(5.3 %) | |

| Other history | 10(6.6 %) | |

| C | Other clinical determinant (conditions like current seizure, face burn or inhalation, hypoglycemia, acute shortness of breath, uncontrolled hemorrhage, coughing blood, chest pain, acute psychosis, poisoning/overdose, pregnancy with abdominal trauma, etc.) | 0(0 %) |

| Overall illness duration | 0( %) | |

| Contact address | 8(5.3 %) | |

| Other history | 9(6 %) |

Discussion

This study assessed the completeness of triage documentation in selected tertiary teaching hospitals in Ethiopia, highlighting areas needing improvement to ensure optimal patient care and safety. The primary goal of triage is to efficiently prioritize patients needing urgent care, considering the facility's resources and local disease burden [[15], [16], [17]]. Beyond sorting patients, the triage system aims to minimize variations in health professionals' decisions to enhance patient safety. Inadequate adherence to the triage system and incomplete documentation can compromise patient safety, and triage models are designed to mitigate such risks [18].

Pre-triage variables

The findings reveal significant shortcomings in the completeness of socio-demographic data at C, with critical information such as patient name, gender, and age poorly documented. This suggests that essential patient information is not being consistently recorded, which can hinder effective patient care and management. Incomplete documentation can lead to challenges in patient identification treatment planning and may affect the hospital's ability to analyze health trends or outcomes effectively. In research carried out in northern Ethiopia, of 251 reviewed charts, 42.1 % contain triage forms, and none were not fully completed; nonetheless, all patients' names and patient medical record numbers were completed, and age and sex were completed >95 % of the time [15]. This showed better completeness than our findings. The study's facilities lack basic socio-demographic data, leading to potential errors in patient identification and treatment.

The finding indicates that while two hospitals maintain a high standard of documentation regarding patient arrival dates and times, there is a significant inconsistency in the recording practices at hospital C. Accurate documentation of arrival times is crucial for assessing the timeliness of care provided to patients. Inconsistent records can lead to delays in treatment, miscommunication among healthcare providers, and potentially poorer patient outcomes. High completeness in documentation allows for better tracking of patient flow and resource allocation within hospitals. In contrast, gaps in documentation at C could hinder effective management and planning, leading to inefficiencies. For studies that rely on data from multiple hospitals, inconsistencies in documentation can skew results or reduce the reliability of findings, limiting the ability to draw meaningful conclusions. The documentation gap could be possibly caused by staffing shortages or high turnover rates, leading to rushed documentation practices and oversight [19]. There may be insufficient training or standardization in documentation practices among staff at C compared to other institutions.

In a previous study conducted in northern Ethiopia, the date and time were recorded in 88.3 % and 91.1 % of cases, respectively [15]. This finding aligns with the results of the current study, suggesting a consistent trend in data documentation practices across different regions. However, it is important to consider the contextual factors that may influence these results. The healthcare systems in both studies may share similarities, such as resource limitations and patient flow dynamics, which could affect the completeness of documentation. Additionally, cultural attitudes towards record-keeping and the training of healthcare personnel may also play a role. Understanding these contextual elements is crucial for interpreting the findings and improving data accuracy in clinical settings

Prehospital care information was inconsistently documented, with a notably low level of recording at A and a comparatively higher rate at C. The mode of transportation was more consistently documented across hospitals. These findings suggest the need for a more standardized approach to documenting prehospital care details, which are crucial for informing treatment decisions and ensuring continuity of care in emergency settings [16]. In the similar study conducted in the Ayder hospital in 2017, only two instances had pre-hospital first aid information recorded, and only 33.3 % of the cases had a referral source listed [15].

Triage score variables

Our analysis of the Triage Early Warning Score (TEWS) highlights significant deficiencies in documenting vital signs. Temperature recordings were notably sparse, particularly at A, raising concerns about the ability to detect febrile conditions early. Blood pressure measurements also showed inadequate documentation at C. Conversely, mobility and level of consciousness were better recorded, yet overall completeness remains insufficient, emphasizing the need for improved documentation practices in triage settings. The study conducted in northern Ethiopia showed a 97.8 % completion rate for heart rate, which was the most frequently recorded vital sign. Systolic blood pressure (93.3 %), temperature (39, 86.7 %), trauma exposure (84.4 %), mobility (82.2 %), respiratory rate (82.2 %), and consciousness (82.2 %) were the next most frequently recorded vital signs [15]. The Triage Early Warning Score (TEWS) relies on all its components; missing any one makes patient categorization challenging. Incomplete TEWS data can significantly hinder timely identification of patients at high risk for deterioration or adverse outcomes [17].

Triage treatment receives minimal attention in the triage documentation, representing a small portion of the overall focus, while triage investigations are also infrequently noted. The documentation of officer names is notably low at one facility, and the consistency in officer signatures across all three hospitals indicates a strong adherence to this practice. Properly recording the names and signatures of triage officers is essential for fostering effective professional communication and accountability. Without these records, addressing identified gaps becomes increasingly difficult, potentially compromising the quality of care provided. Incomplete patient information significantly hinders emergency triage by complicating severity assessments and potentially delaying or misprioritizing treatment. This can lead to worsened conditions, complications, or even death, as well as errors in medical records and billing. To mitigate these risks, healthcare providers must prioritize gathering comprehensive patient information, even under high workload conditions. In a study conducted in Dar es Salaam emergency centers, Tanzania, lack of proper documentation contributed to ineffective triage systems and delays [20]. In the study conducted in Sweden, some of the variables are documented more often than the others. This wide variation between the highest and lowest frequencies of documentation and correct triage level indicates poor adherence to the intention of the triage system, which is to reduce the nurses’ individual variation and to ensure patient safety [18].

Triage system disparity

In our study areas, there have been two different triaging systems being implemented. Variations in triage tools across health institutions can lead to significant inconsistencies in patient care, ultimately affecting clinical outcomes and resource allocation. When different facilities employ diverse triage systems, the criteria for prioritizing patients can vary widely, resulting in disparities in how quickly and effectively individuals receive necessary medical attention. This inconsistency can exacerbate delays in treatment for critical conditions, increase the risk of adverse outcomes, and create challenges in inter-facility transfers, where patients may be assessed differently depending on the institution's triage protocol. Furthermore, such variations can complicate training for healthcare providers, as they must navigate multiple systems and guidelines, which may lead to confusion and errors in judgment during high-pressure situations. Addressing the underlying causes through enhanced training [[21], [22], [23], [24]], better staffing, and improved systems could help standardize practices across all institutions and enhance the quality of care provided to patients [15,18,[25], [26]].

Strength and Limitation of Study: As this is a multi-center study, it offers valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and institutional leaders to address the identified shortcomings. However, being a cross-sectional study may limit the ability to generalize the findings.

Conclusion

This study reveals significant inconsistencies in the completeness of triage documentation across three hospitals in Ethiopia. These findings underscore the urgent need for interventions to improve documentation practices in order to enhance patient safety, minimize medical errors, and optimize overall care delivery.

Standardization of triage scales and the implementation of continuous professional development programs focused on triage documentation are essential steps towards achieving this goal. Further research is warranted to explore the underlying barriers to complete triage documentation and to develop and evaluate targeted strategies for improving compliance with established triage protocols.

Dissemination of results

The result of the study will be presented to the community of included Hospitals in the study, and will be disseminated to concerned stakeholderS in order to enhance appropriate intervention and guide future plans for the development of effective triage tools or modification of the existing ones.

Authors contribution

The authors contributed to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: WW, AZ, SY, MS, TB, TGS, BT, ZGD, DA, EG, EAA, TBI, ST, AA, and AWT each contributed to conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, validation, and writing – review and editing. WW, MS, and AA contributed to funding acquisition and project administration. WW, SY, MS, ST, ZGD, DA, EG, EAA, TBI, and AWT contributed to supervision. WW, BT, and MS contributed to formal analysis and writing – original draft, respectively. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Ethiopian Society of Emergency and Critical Care Professionals provided funding. The funder had no role in the research design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the dedicated data collectors whose meticulous efforts were vital to the success of this study. Additionally, we appreciate the support and collaboration of the institutions involved and Ethiopian society of emergency and critical care professionals for funding, which greatly facilitated this research endeavor.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.afjem.2025.100888.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hess E.P., Wells G.A., Jaffe A., et al. A study to derive a clinical decision rule for triage of emergency department patients with chest pain: design and methodology. BMC Emerg Med. 2008;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray S.E., Finch C.F. Assessing the completeness of coded and narrative data from the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset using injuries sustained during fitness activities as a case study. BMC Emerg Med. 2016;16:24. doi: 10.1186/s12873-016-0091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmberg L., Mani K., Thorbjørnsen K., et al. Trauma triage criteria as predictors of severe injury - a Swedish multicenter cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(40) doi: 10.1186/s12873-022-00596-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skyttberg N., Chen R., Koch S. Man vs machine in emergency medicine – a study on the effects of manual and automatic vital sign documentation on data quality and perceived workload, using observational paired sample data and questionnaires. BMC Emerg Med. 2018;18(54) doi: 10.1186/s12873-018-0205-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen J.A., Rasmussen L.S., Rydahl-Hansen S. Barriers and facilitating factors related to use of early warning score among acute care nurses: a qualitative study. BMC Emerg Med. 2017;17:36. doi: 10.1186/s12873-017-0147-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerie S., Tilahun A., Mandesh A. Triage skill and associated factors among emergency nurses in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2017: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:658. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Considine J., Botti M., Thomas S. Do knowledge and experience have specific roles in triage decision-making? Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(8):722–726. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.015. AugPMID: 17656608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordi K., Grossmann F., Gaddis G.M., et al. Nurses’ accuracy and self-perceived ability using the Emergency Severity Index triage tool: a cross-sectional study in four Swiss hospitals. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23:62. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0142-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zachariasse J.M., van der Hagen V., Seiger N., Mackway-Jones K., van Veen M., Moll H.A. Performance of triage systems in emergency care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026471. May 28PMID: 31142524; PMCID: PMC6549628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . 2nd ed. World Health Organization; 2009. UPDATED GUIDELINE: paediatric emergency triage, assessment and treatment care of critically ill children; pp. 1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelwahab R., Yang H., Teka H.G. A quality improvement study of the emergency centre triage in a tertiary teaching hospital in northern Ethiopia. Afr J Emerg Med. 2017;7(4):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.05.009. DecEpub 2017 Aug 8. PMID: 30456132; PMCID: PMC6234140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demas T., Getinet T., Bekele D., Gishu T., Birara M., Abeje Y. Women's satisfaction with intrapartum care in St Paul's Hospital Millennium Medical College Addis Ababa Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):253. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1428-z. Jul 28PMID: 28754136; PMCID: PMC5534094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibhat S.G., Fenta T.G., Sander B., et al. Health-related quality of life and its predictors among patients with breast cancer at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:165. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1239-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zemedie Biruktawit, Sultan Menbeu, Zewdie Ayalew. Acute poisoning cases presented to the Addis Ababa Burn, Emergency, and Trauma Hospital Emergency Department, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Emerg Med Int. 2021;2021:5. doi: 10.1155/2021/6028123. Article ID 6028123pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdelwahab R., Yang H., Teka H.G. A quality improvement study of the emergency centre triage in a tertiary teaching hospital in northern Ethiopia. Afr J Emerg Med. 2017;7(4):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.05.009. DecEpub 2017 Aug 8. PMID: 30456132; PMCID: PMC6234140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peta D., Day A., Lugari W.S., Gorman V., Ahayalimudin N., Pajo V.M.T. Triage: a global perspective. J Emerg Nurs. 2023;49(6):814–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2023.08.004. NovPMID: 37925222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yancey C.C., O'Rourke M.C. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2024. Emergency department triage. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557583/ Jan-. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jönsson K., Fridlund B. A comparison of adherence to correctly documented triage level of critically ill patients between emergency department and the ambulance service nurses. Int Emerg Nurs. 2013;21(3):204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.07.002. JulEpub 2012 Aug 9. PMID: 23830372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidet M., Canoui-Poitrine F., Revaux F., Perennou T., Bertin M., Binetruy C., Palazzi J., Tapiero E., Nguyen M., Reuter P.G., Lecarpentier E., Vaux J., Marty J. Factors affecting medical file documentation during telephone triage at an emergency call centre: a cross-sectional study of out-of-hours home visits by general practitioners in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):531. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4350-4. Jul 30PMID: 31362748; PMCID: PMC6668156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aloyce R., Leshabari S., Brysiewicz P. Assessment of knowledge and skills of triage amongst nurses working in the emergency centres in Dar es Salaam. Tanzania. African Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014;4(1):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burgess L., Kynoch K., Hines S. Implementing best practice into the emergency department triage process. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2019;17(1):27–35. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000144. MarPMID: 29782353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malak M.Z., Mohammad Al-Faqeer N., Bashir Yehia D. Knowledge, skills, and practices of triage among emergency nurses in Jordan. Int Emerg Nurs. 2022;65 doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2022.101219. NovEpub 2022 Oct 30. PMID: 36323189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bednarek-Chałuda M., Żądło A., Antosz N., Clutter P. Polish perspective: the influence of national emergency severity index training on triage practitioners' Knowledge. J Emerg Nurs. 2024;50(3):413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2023.12.002. MayEpub 2024 Feb 12. PMID: 38349291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malyon L., Williams A., Ware R.S. The Emergency Triage Education Kit: improving paediatric triage. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2014;17(2):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2014.02.002. MayEpub 2014 Apr 16. PMID: 24815203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.di Martino P., Leoli F., Cinotti F., Virga A., Gatta L., Kleefield S., Melandri R. Improving vital sign documentation at triage: an emergency department quality improvement project. J Patient Saf. 2011;7(1):26–29. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31820c9895. MarPMID: 21921864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerdtz M.F., Waite R., Vassiliou T., Garbutt B., Prematunga R., Virtue E. Evaluation of a multifaceted intervention on documentation of vital signs at triage: a before-and-after study. Emerg Med Australas. 2013;25(6):580–587. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12153. DecEpub 2013 Nov 8. PMID: 24308615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.