Abstract

Magnesium–lithium hybrid ion batteries (MLIBs) offer a promising energy storage technology that combines the safety and dendrite-free plating/stripping of Mg anodes with the rapid Li+-dominated diffusion in cathode materials. However, for electrodes that undergo significant volume/structural changes during cycling, conventional slurry-cast fabrication often leads to microstructural degradation, active material detachment, and consequently, poor cycling stability and rapid capacity fading. Here, we report a self-standing, carbon- and binder-free tantalum trisulfide (TaS3) nano fibrous (NF) film, synthesized via a facile one-step physical vapor transport reaction that addresses these challenges through mechanistic innovations. Mechanistic investigations reveal that the TaS3 NF electrode undergoes dual cationic (Ta5+/Ta3+) and anionic (S2 2–/S2–) redox reactions, accompanied by electrochemically induced phase transitions and in situ exfoliation. The dual redox couples provide a large number of Li+ ion storage sites, while the structural changes lead to fiber-level nanosizing, which in turn promotes fast (near) surface ion storage and pseudo capacitive behavior. Despite these significant transformations, the robust fibrous architecture retains structural integrity throughout prolonged cycling, as confirmed by in operando and ex situ characterization. This dual-redox, in situ exfoliation, and architecture-driven mechanism underpins the electrode’s exceptional cycling stability and high rate capability. As a result, the TaS3 NF electrode achieves a high reversible capacity of 178.5 mA h g–1 at 50 mA g–1, maintains 91.6% of reversible capacity after 100 cycles, and delivers 144.4 and 119.0 mA h g–1 at 500 and 1000 mA g–1, respectively, surpassing those of slurry-cast bulk TaS3 controls. Furthermore, the maintenance of a flexible film structure after extended cycling suggests potential applicability in next-generation wearable and structurally adaptive energy storage systems. These findings highlight the potential of self-standing, carbon- and binder-free film electrodes in advancing the cycling stability, energy density, and design versatility of MLIB systems and beyond.

Keywords: magnesium−lithium hybrid ion batteries, tantalum trisulfide (TaS3), self-standing electrodes, nanofiber, cycling stability, mixed anionic and cationic redox

1. Introduction

The increasing global demand for sustainable and efficient energy storage solutions has driven the development of advanced rechargeable battery technologies. Among these, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have become the dominant choice due to their high energy density, long cycle life, and wide application in portable electronics and electric vehicles. Their exceptional energy density and extended cycle life have positioned them at the forefront of electrochemical energy storage solutions. However, the growing reliance on LIBs has raised significant concerns regarding the scarcity of lithium resources, fluctuating costs, and safety risks, including thermal runaway and flammable electrolytes. These limitations have prompted a reassessment of existing battery technologies and exploration of alternative systems that can meet future energy storage demands.

Magnesium-ion batteries (MIBs) have emerged as a promising alternative to LIBs, offering several inherent advantages. Magnesium metal anodes exhibit minimal dendrite formation during repeated plating and stripping processes in many high-performance electrolytes, significantly reducing safety risks associated with short circuits and fire hazards. This property enables the safe use of magnesium metal as an anode material in MIBs, offering a substantial capacity of 2205 mA h g–1, significantly surpassing the typical capacities of alternative anodes in LIBs such as graphite (ca. 372 mA h g–1). Furthermore, the abundance of magnesium and its low toxicity make it an attractive option for large-scale energy storage applications. Despite these benefits, the high charge density and strong polarizing nature of Mg2+ ions result in poor ion diffusion kinetics and low reversible magnesium storage capacities in most cathode materials, presenting a major challenge to the development of MIBs.

To overcome these challenges, magnesium–lithium hybrid ion batteries (MLIBs) have been developed as a promising solution. MLIBs combine the safety and dendrite-free properties of Mg anodes with the rapid diffusion kinetics of Li+ ions in cathode materials. By introducing lithium salts (e.g., LiCl, LiBH4, and LiTFSI) into magnesium electrolytes, MLIBs enable reversible Li+ intercalation into cathode hosts while retaining the advantages of the magnesium anode. Notably, the thermodynamic incompatibility (−3.04 V for Li+/Li and −2.37 V for Mg2+/Mg vs SHE) prevents Li plating on Mg and underpins the operational stability of MLIBs, which has been confirmed by previous reports. This hybrid approach has demonstrated substantial performance improvements (compared to MIBs) in various intercalation-type cathode materials that have already proven effective in LIBs, such as polyanionic compounds (e.g., LiFePO4, LiTi2(PO4)3, and Li3V2(PO4)3; 100–150 mA h g–1) − and transition metal oxides (TMOs; e.g., VO2 and TiO2; 150–200 mA h g–1). , Transition metal chalcogenides (TMCs), with higher electrical conductivity than TMOs, have further been extensively explored. For instance, layered MoS2 has been employed in MLIBs and exhibited reversible capacity of ca. 210 mA h g–1 at a current density of 20 mA g–1. Layered VS2 was reported to exhibit a reversible capacity of 181 mA h g–1 at 50 mA g–1. Additionally, conversion-type TMC materials have been reported to exhibit considerable capacities; however, repeated conversion reactions often result in the agglomeration of metal particles and lithium/magnesium sulfides, leading to rapid capacity fading during long-term cycling.

Despite these advancements, the conventional slurry-cast fabrication of cathodes presents certain possible limitations. The use of binders and conductive carbon introduces inactive components (20–30 wt %) into the electrode, reducing energy density and increasing the likelihood of parasitic side reactions. Additionally, for electrodes experiencing substantial volume and structural changes during repeated cycling, the adhesion between active materials and the conductive matrix is often insufficient. This can lead to active material detachment, inconsistent electrical conductivity, and ultimately rapid capacity degradation. Self-standing, flexible (SSF) electrodes have emerged as a feasible solution to these issues, particularly for electrodes subject to significant structural transformations, such as VS4. , By eliminating the need for binders, conductive carbon, and current collector, SSF electrodes offer the potential for higher energy density. The interconnected framework in SSF electrodes facilitates reliable and long-lasting electrical and ionic transport while maintaining structural uniformity during discharge–charge cycles, mitigating significant structural changes and active material detachment, thereby enhancing cycling stability and capacity retention. Moreover, the inherent flexibility of SSF electrodes makes them particularly suitable for wearable energy storage devices, such as body-conformable health monitors, smart textiles, and other flexible electronics. These applications demand both high electrochemical performance and mechanical robustness to withstand repeated deformation during operation. As a result, SSF electrodes are increasingly recognized not only as one of the most effective solutions to the limitations of conventional electrodes undergoing substantial structural transformation, but also as a key enabler for advancing wearable energy storage technologies.

In recent years, (quasi-)one-dimensional (1D) chain-like TMCs have garnered significant attention for their unique structural and electrochemical properties in rechargeable batteries. Vanadium pentasulfide (VS4) is a notable example that has been extensively studied in LIBs, MIBs and MLIBs, among others. , In VS4, redox-active S2 2– anions, in conjunction with V4+ cations, participate in a dual anionic/cationic redox process, enabling multielectron transfer and delivering extra capacity. This mechanism contrasts with layered transition metal dichalcogenides containing only nonreducible S2– anions. When applied in MLIBs, VS4 achieves notable capacities ranging from 300 mA h g–1 to 400 mA h g–1, ,, yet suffers from pronounced capacity decay during initial cycles, likely due to structural degradation and active material detachment. Beyond VS4, however, dual redox-active (quasi-)1D TMCs remain largely underexplored in MLIBs, highlighting the importance of investigating alternative materials capable of harnessing both cationic and anionic redox processes in a stable and structural robust framework. SSF tantalum trisulfide (TaS3), a typical quasi-1D chain-like TMC featuring both S2 2– and S2– in its structure, has been previously synthesized via a physical vapor transport (PVT) method and studied as an electrode material for LIBs. , Despite the scarcity of Ta, its use in TaS3 film electrodes is justified by the high sustainability. Unlike other electrode materials that may require complex recycling processes, self-standing TaS3 films can be easily recycled and regenerated due to their simple structure, free of complex additives or binders, making them an environmentally friendly option for battery applications.

In this study, we present, for the first time, the application of self-standing, flexible, nano fibrous TaS3 films as cathode materials for MLIBs. These films are composed of interwoven ultralong nanofibers, ranging from 100 nm to several hundred nanometers in lateral dimensions, which are formed by stacking smaller fibers. This unique architecture ensures stable electrical conductivity, efficient ion transport, and mechanical robustness during cycling. Electrochemical evaluations reveal that TaS3 nanofiber (NF) electrodes outperform conventional slurry-cast counterparts, delivering a high reversible capacity of 178.5 mA h g–1 at 50 mA g–1, robust cycling stability with 91.6% capacity retention over 100 cycles, and excellent rate capability. Mechanistic studies (via ex situ scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and in operando powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)) demonstrate that the fibrous microstructure remains intact, despite significant phase/structural changes, exfoliation and in situ nanosizing during cycling. The high Li+-dominated capacity arises from mixed cationic (Ta5+/Ta3+) and anionic (S2 2–/S2–) redox reactions, as confirmed by ex situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and Raman spectroscopy. Furthermore, the robust flexibility of TaS3 NF films makes them particularly suitable for integration into wearable and flexible electronic devices, where mechanical durability and lightweight properties are essential. These findings highlight the potential of self-standing, carbon- and binder-free film electrodes to address the limitations of conventional electrodes and pave the way for future high-energy-density, cycling-stable, and wearable MLIB systems and beyond.

2. Experimental Section

All experiments outlined below were conducted at room temperature (RT), unless explicitly stated otherwise.

2.1. Synthesis of TaS3 Nanofibers (NFs) and Bulk TaS3

The synthesis of TaS3 NFs was conducted via a modified physical vapor transport (PVT) reaction, using a custom-designed fused-silica tube reactor (Figure S1a), similar to one described in our previous work. The reactor tube (250 mm in length, 12 mm in inner diameter) featured a neck positioned 120 mm from the base, allowing the spatial separation of tantalum powder (Aldrich, 99.5%) placed at the bottom and sulfur pellets (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.98%) positioned above the neck. This configuration serves two critical purposes: (i) it prevents premature contact between molten sulfur and solid tantalum, which could otherwise trigger uncontrolled side reactions and hinder the anisotropic growth of TaS3 NFs; (ii) it ensures that tantalum is only exposed to sulfur vapor during heating, thereby facilitating uniform vapor–solid reaction and the formation of well-defined fibrous products. Compared to conventional chemical vapor transport (CVT) methods, this PVT approach does not require any transport agents and minimizes the formation of byproducts. In addition, the method is readily scalable: by appropriately adjusting the inner diameter and pressure-bearing capacity of the silica tube, as well as the quantity of starting materials, large-scale synthesis can be achieved without compromising product quality. These features make this approach particularly attractive for the fabrication of self-standing electrode films toward practical applications.

Specifically, 0.9 g of tantalum powder was transferred into the tube through the neck using a small funnel, followed by placing the sulfur pellet near the neck. Subsequently, the tube was evacuated and flame-sealed under a still vacuum of 3 × 10–4 mbar. The sealed tube was then placed horizontally in a box furnace (Brothers Box Furnace, BR-12N-5) and heated to 550 °C at a rate of 200 °C h–1 for a dwell time of 66 h. During this heating process, the sulfur pellet melts and then evaporates, or sublimes into sulfur gas, which transports to the bottom of the tube and reacts with the Ta powder to form the TaS3 NF film. After the reaction, the tube was allowed to naturally cool to RT. A photograph of the quartz tube containing the TaS3 NFs after heating and cooling to room temperature is provided in Figure S1b. The product consists of the fiber aggregates located in the upper region and the bulk condensed particles located at the bottom (Figure S1c).

The fiber aggregates can be easily separated and spread using tweezers and a doctor blade. As illustrated in Figure S1d, the as-collected fiber aggregates, resembling a “trouser leg”, can be made with a straight cut along the length of the “leg” (simplified as a cylindrical film) using sharp scissors. Subsequently, the cut fiber aggregates can be spread and flattened using a doctor blade, forming the flat film that can be cut into film discs as electrodes for MLIBs. These self-standing TaS3 films are soft and can undergo folding up to 180° without being ruptured, indicating good structural flexibility (Figure S2).

2.2. Synthesis of Cubic Li2TaS3

Cubic Li2TaS3 was synthesized for the first time by ball milling. Initially, TaS2 was synthesized from a mixed powder of 0.9 g of Ta and 0.32 g of S using a similar method as described for the TaS3 synthesis, except for the absence of a neck on the quartz tube. Subsequently, 0.842 g of the as-synthesized TaS2 powder and 0.158 g of Li2S powder (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.98%) were hand-mixed and sealed in a 50 mL tungsten carbide (WC) jar in an Ar-filled glovebox. Additionally, 10 WC balls (10 mm diameter, 7.6 g per ball) were placed in the jar to ensure a ball-to-powder ratio of 76:1. A Retsch, PM 100 planetary ball mill was employed for milling, with parameters set to 510 rpm for 60 h, with intervals of 2 min between 5 min of reverse rotations. After the mechanochemical synthesis, a dark brown powder was collected and stored in the glovebox.

2.3. Material Characterization

As-synthesized air-stable samples were characterized in air atmosphere, whereas the air-sensitive cycled samples were handled and measured under vacuum or inert gas (Ar or N2) atmosphere using homemade vessels, such as flame-sealed capillaries and airtight domed holders.

PXRD patterns were acquired in Bragg–Brentano geometry (flat plate, reflection) over a 2θ range of 5°–70° with a step size of 0.0175° and a scan rate of 0.083° s–1 on a Rigaku MiniFlex diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα (λ = 0.154 nm) X-ray source operated at 40 kV and 40 mA and in transmission geometry (capillary, 5°–70°, 0.0131°, 0.016° s–1) on a PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with an unmonochromated Cu Kα X-ray radiation operated at 45 kV and 40 mA. In operando PXRD patterns were collected in Bragg–Brentano geometry (flat plate, reflection) between 5°–65° 2θ with a step size of 0.0263° at a scan rate of 0.074° s–1 on the PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer. For in operando PXRD experiments, a homemade CR2032 coin cell with a 7 μm-thick Kapton window (8 mm diameter, sealed with glue and PVDF) at the center of the positive case was employed.

Raman spectra were collected at RT using a LabRAM HR spectrometer equipped with a green laser with a wavelength of 532 nm. The as-synthesized samples were prepared and measured in air by pressing the TaS3 film and powder onto glass slides. The cycled samples were sealed in Ar by flame. TG-DSC measurement was performed using a TA Instruments SDT Q600 instrument, ramping from RT to 650 °C at a rate of 10 °C min–1 in a 2% O2/98% Ar atmosphere (100 mL min–1).

Constituent species and their oxidation states were probed by X-ray photon spectroscopy (XPS) using Thermo Scientific Nexsa and Kratos AXIS Supra+ X-ray photoelectron spectrometers, both equipped with an Al Kα X-ray source. All high resolution XP spectra were analyzed and curve fitted according to Conny and Powell, typically employing dual Gaussian–Lorentzian functions to obtain precise binding energies. , X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements for the S K-edges (2440 to 2500 eV) were performed at the BL2A beamline of the UVSOR Synchrotron Facility, Institute for Molecular Science (Japan). The spectra were collected in total electron yield mode. SEM-EDS experiments were performed on a TESCAN CLARA microscope equipped with an Oxford Instruments UltimMax 65 energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer at 15 kV. The TaS3 NFs and bulk powdered specimens were prepared by adhering a small piece of TaS3 NF film or scattering a small amount of TaS3 bulk powder onto conductive carbon tape in air and coating with a thin layer (ca. 10 nm of thickness) of gold via plasma sputtering. Electrochemically cycled electrodes were prepared in the glovebox without gold coating and sealed in a 14 mL vial before being promptly transferred to the SEM chamber, with an air exposure time of less than 10 s. TEM imaging was conducted on a FEI Tecnai G2 F30 Microscope (300 kV). The TEM specimens were prepared by dispersing approximately 1 mg of the as-made TaS3 NFs in 1 mL absolute ethanol in an ultrasonic bath for 5–10 min. Subsequently, one drop of the dispersion was deposited onto an ultrathin carbon-coated Cu TEM grid and air-dried for an hour.

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

The electrochemical performance of both TaS3 NF and bulk TaS3 electrodes was assessed in CR2032 type coin cells. Magnesium metal foil pieces (0.2 mm thickness, diameter 15 mm, 99.5%, sourced from Huabei Magnesium Processing Plant) were used as anodes. As-synthesized TaS3 NFs were directly used as cathodes. For bulk TaS3 electrodes, slurries were prepared by blending 0.07 g of active material, 0.02 g of conductive carbon (carbon black, 99%, Alfa Aesar), and 0.01 g of polyvinyldifluorine (PVDF, 98%, average molecular weight ∼ 534,000, Sigma-Aldrich) binder in ca. 0.5 mL of N-methyl pyrrolidone (anhydrous, 99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich). The resulting slurries were coated onto carbon paper chips (12 mm diameter, 0.19 mm thickness, areal density of 0.44 g cm–2, Saibo Electrochemistry) and dried under vacuum (0.1 mbar) in a drying oven at 60 °C overnight. The typical mass of the self-standing TaS3 NFs or slurry-cast bulk TaS3 on the carbon paper current collector was around 1–2 mg, or 0.88–1.77 mg cm–2. In an Ar-filled MBraun LabStar glovebox (O2 and H2O < 0.5 ppm), 10.0 mL solution of 0.4 M “all-phenyl complex” (APC, MIB electrolyte) electrolyte was prepared by dropwise addition of 4.0 mL of a solution of phenyl magnesium chloride (PhMgCl, 2.0 M in tetrahydrofuran (THF), Sigma-Aldrich) into 0.534 g of AlCl3 (ultra dry, 99.99%, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 6 mL of THF (≥99.9%, anhydrous, inhibitor-free, Sigma-Aldrich) under magnetic stirring. Additionally, a 2.0 mL 1 M LiCl-APC (MLIB electrolyte) solution was prepared by adding 0.085 g of LiCl (≥99.9%, Aldrich) into 2.0 mL of 0.4 M APC, followed by stirring overnight in the glovebox. The electrolyte used for the assembly of comparative LIBs was 1.0 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC = 50/50 (v/v) (battery grade, Sigma-Aldrich). The volume of electrolyte used for the assembly of coin cells was around 90 μL.

Discharge and charge experiments, as well as galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) experiments, were conducted using a LAND CT2001A battery test system over a voltage range of 0.4–2.2 V. For GITT experiments, the test batteries were discharged for 600 s at a current density of 25 mA g–1, followed by a relaxation period (no current applied) of 1200 s. These discharging/relaxation or charging/relaxation steps were repeated until the discharging limit of 0.4 V or charging limit of 2.2 V was reached. The GITT curve data and details on how they were used to calculate diffusion coefficients are provided in Equation S4 and Figure S19. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed using a PalmSens4 potentiostat at RT. CV experiments were conducted over a voltage range of 0.4–2.2 V at scan rates of 0.1–0.5 mV s–1. Scans began from the open-circuit voltage down to the low-voltage cutoff, followed by a sweep up to the high-voltage cutoff. EIS experiments were performed over a frequency range of 100 000 to 0.01 Hz with a potential amplitude of 10 mV. The obtained Nyquist plots were fitted using AfterMath software.

3. Results and Discussion

The PXRD patterns of TaS3 NFs and bulk TaS3 are presented in Figure S3. It can be observed that peaks in the pattern of TaS3 NFs can be mainly assigned to an m 1-TaS3 monoclinic phase with space group C2/m, while the pattern of bulk TaS3, with quite a few reflections absent, may be considered an orthorhombic structure (o-TaS3; PDF - 18–1313; space group of C2221). However, the assignment of bulk TaS3 is not conclusive due to the lack of detailed crystal structure information for this orthorhombic phase in the literature. Previous studies indicate that TaS3 NFs comprise mainly of the m 1-phase with a minority of a second monoclinic phase m 2 (m 2-phase) present. Therefore, Rietveld refinement of the PXRD data (transmission geometry, capillary mode) was performed based on the above two-phase mode to achieve compositional and structural parameters for the two components in the as-synthesized TaS3 NF product. As shown in Figure a and Tables S1–3, the refinement results reveal a mixture of m 1- and m 2-phases in the TaS3 NFs product, accounting for 96.6(5) wt % and 3.4(2) wt %, respectively. The refined crystal parameters for m 1-phase, a = 19.9127(9) Å, b = 3.3382(1) Å, c = 15.1685(3) Å, and β = 112.463(5)°, are comparable to published values. The crystal information on the m 2-phase is provided in Tables S2–3. Rietveld refinement for bulk TaS3 was also attempted using the m 1-phase crystal structure, and the corresponding results are provided in Figure S4 and Table S4. Similar to the initial flat plat PXRD analysis, it was observed that the refinement could not resolve some obvious peaks for the m 1-TaS3 phase, and the refined results show a greater deviation to the m 1-TaS3 model when compared to those of TaS3 NFs. From the overall refinement profile, however, it appears that bulk TaS3 exhibits a structure similar to TaS3 NFs but with notably higher symmetry, probably due to the slightly different chain arrangements in their structures. The crystal structure for TaS3 NFs is shown in Figure b-d. TaS3 (using the major m 1-phase in NFs as an example) consists of pseudolayers separated by a van der Waals (vdW) gap. These pseudolayers are formed from the arrangement and weak bonding of infinite 1D [TaS6] n chains (which extend along the b-axis via S–Ta–S polar covalent bonds) along the c-axis. The interlayer spacing of the (002) reflection is ca. 9.2 Å for the dominant m 1-phase in the TaS3 NF material, as derived from the Rietveld refinement.

1.

(a) Fitted PXRD diffraction profile for TaS3 NFs (transmission geometry, capillary mode). Crystal structure of TaS3 NF showing projections down the (b) b-axis, (c) a-axis, and (d) c-axis, with unit cell shown, as visualized by Vesta software. (e) Raman spectra of as-made TaS3 NFs and bulk TaS3. High-resolution XPS spectra of the: (f) Ta 4f and (g) S 2p regions for TaS3 NFs.

Raman spectra of the as-prepared TaS3 NFs (m-phase) and bulk TaS3 (possibly o-phase) are presented in Figure e. The signals in both spectra are consistent with those of TaS3 NFs reported and theoretically calculated by Mayorga-Martinez et al., and are comparable to the vibrational modes of TaS3 NFs investigated by Wu et al. The peak at approximately 58 cm–1 can be attributed to two-shear (S) eigenmodes, namely, interchain displacement parallel (S∥) and perpendicular/nonparallel (S⊥) to the Ta-chain. The peaks ranging from 60 cm–1 to 425 cm–1 are likely due to Ag-like vibrational modes which are yet to be determined accurately, while the signal at approximately 495 cm–1 is ascribed to Ag S–S modes. The slightly higher intensity of the peak at 253 cm–1 is attributable to the presence of the m 2-phase in the TaS3 NFs. Note that Raman spectroscopic studies of TaS3 remain very limited and nonsystematic, thus the above discussion should be considered instructive instead of conclusive.

XPS was employed to investigate the surface chemical states of the Ta and S elements in TaS3 NF. Six peaks are observed in the fitted Ta 4f high-resolution spectrum (Figure f). The doublet peaks at ca. 23.7 and 25.6 eV are ascribed to the Ta 4f7/2 and Ta 4f5/2 transitions, respectively, and match well with the characteristic binding energies of Ta4+ (those coordinated with disulfide anions) in tantalum chalcogenides. Given that Ta in TaS3 has a formal (or average) valence state of around +4.67, the peaks at ca. 24.3 and 26.3 eV can be attributed to the Ta5+ (those coordinated with sulfide anions) of TaS3. Indeed, by calculating the atomic percentages of Ta5+ (ca. 58.5%) and Ta4+ (ca. 41.5%) species of TaS3 from the Ta 4f spectrum, a mean valence state of +4.59 is obtained, which closely aligns with the theoretical value. The last pair of peaks at ca. 25.9 and 28.0 eV are typical for Ta5+ in Ta2O5. It is not surprising to witness the surface oxidation of the TaS3 NFs given their air sensitivity and their tendency to release H2S, for example, when exposed to air. This surface oxidation is further supported by multiple lines of evidence: (a) the appearance of Ta–O signals in both the Ta 4f and O 1s spectra after Ar+ etching (Figure S5a, b), indicating the presence of tantalum oxide species at or near the surface; (b) the identification of a monoclinic Ta2O5 layer on the fiber surface, as revealed by HRTEM analysis (Figure f); and (c) the absence of any Ta–O phase features in the PXRD pattern and Raman spectra, along with the uniform fibrous morphology observed in SEM images (Figure a, b), which shows no evidence of secondary oxide phases. The high-resolution spectrum in the S 2p region shows four peaks after data fitting (Figure g). The paired peaks at ca. 162.7 and 163.9 eV, corresponding to S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2, can be attributed to S2 2– species. , Meanwhile, the second set of peaks at ca. 161.6 and 162.7 eV is ascribed to S2– in TaS3. The total negative charge from S2 2– and S2– species (−4.59) balances the positive charge of Ta ions in TaS3, in accordance with charge neutrality principles. Furthermore, the Ta 4f and S 2p spectra of bulk TaS3 (Figure S5c, d) closely resemble those of TaS3 NF, confirming their comparable chemical environments.

2.

Results of electron microscopy characterization on the as-prepared TaS3 NFs displaying: (a) low-magnification (×20k) and (b) high-magnification (×120k) SEM images; (c) SEM-EDS elemental maps for Ta, S, and O, respectively; (d) low-magnification, (e) high-magnification TEM, and (f) HRTEM images.

The morphology and composition of TaS3 NFs and bulk TaS3 were characterized using SEM-EDS and TEM instruments. In Figures a, b, SEM images at low and high magnifications reveal that the former sample exhibits a network structure composed of numerous ultralong fibers with length of a few centimeters (also see Figure S1c) and lateral size of less than 1 μm. Looking closer, each micron-sized fiber appears to be made up of bundles of nanofibers with diameters spanning 100 to 300 nm. In contrast, bulk TaS3 consists mainly of micron-sized particles ranging from several micrometres to tens of micrometres, although the enlarged SEM image shows densely packed short needle-shaped crystallites (Figure S6). An SEM image and the corresponding elemental maps for Ta, S, and O in fibers shown in Figure c, illustrate uniform and homogeneous distributions of the constituent elements. The EDS spectrum (Figure S7) indicates an S:Ta mole ratio of 2.67:1, slightly lower than the stoichiometric value of 3:1. This deviation could be attributed to surface oxidation and/or inaccuracy in the quantification of Ta due to the lack of suitable elemental EDS standards for this element. Previous reports have noted even lower S-to-Ta ratios (of ∼2) in TaS3 due to the absence of standardization. To obtain a more accurate S/Ta ratio on a bulk scale, a TGA experiment was conducted in an O2/Ar atmosphere, and the calculation details and results are shown in Figure S8. The S/Ta ratio calculated through TGA is 2.91 ± 0.02, corresponding very well to the stoichiometry of TaS3. The slight sulfur deficiency may be related to the presence of certain amount of sulfur vacancies within TaS3 NF, which, well documented in the literature, facilitate ion diffusion and provide additional sites for ion storage. , TEM images in Figure d, e exhibit numerous cross sections of the nanofibers, confirming their lateral dimensions (typically 100–250 nm) in good accordance with the SEM results. The HRTEM image further reveals lattice fringes in single nanofibers (Figure f). Measurements of different lattice fringe distances were performed using the DigitalMicrograph software (Figure S9), yielding d-spacings of 9.13(3) Å for the (200) crystal plane and 3.78(2) Å for the (20 ®4) plane, both associated with the m 1 and/or m 2 phase identified in the PXRD pattern. Additionally, a third set of lattice fringes, observable near the periphery of the fiber region exposing the (20 ®4) plane, was indexed to the (002) planes of monoclinic Ta2O5, corroborating the presence of surface oxidation as previously inferred from the XPS analysis.

The electrochemical performance of the as-synthesized TaS3 NF electrodes in MLIBs was determined and compared with slurry-cast electrodes prepared from bulk TaS3. Two key aspects are assessed: (a) the significance of the LiCl additive to the electrochemical properties of the TaS3 electrode and (b) the effect of the flexible fibrous morphology on the performance of the electrodes. Initially, the impact of LiCl addition to the “all phenyl complex” (APC) electrolyte on the performance of the self-standing nanofibrous TaS3 electrode was investigated using a cyclic voltammetry (CV) approach. CV curves of the TaS3 NF electrode in LiAPC and APC electrolytes were obtained at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s–1. In pure APC electrolyte, no electrochemical redox peaks are observed in the CV curves of the TaS3 NF electrode (Figure S10a), indicating negligible magnesium ion intercalation. However, as depicted in Figure a, with the presence of LiCl in the electrolyte, significant cathodic/anodic redox peaks emerge at ca. 0.74 V/ (1.09, 1.61, and 1.91 V) in the first CV scan, indicating the intercalation/deintercalation of Li+ and possibly Mg2+ ions. The second CV curve exhibits a broadened and weakened cathodic peak at higher voltage compared to the first cycle which suggests an irreversible change during the first cycle. Subsequent scans show cathodic peaks, corresponding to the reduction of S2 2– and Ta5+ ions (See mechanistic analysis in coming sections), shift to progressively higher voltages (ca. 1.45 and 1.04 V, respectively) and appear to remain, with stabilized anodic peaks at ca. 1.15, 1.58, and 1.96 V, indicating improved electrochemical properties and stable, reversible redox reactions. CV curves of the TaS3 NF electrode in an LIB and the bulk TaS3 electrode in an MLIB were also obtained for comparison (Figure S11). Both electrodes in MLIBs exhibit similar electrochemical behavior to the TaS3 NF electrode in LIBs, indicating the intercalation of Li+ cations as the primary charge carriers. The initial four (dis)charge curves of the TaS3 NF electrode at a current density of 50 mA g–1 are presented in Figure b. A plateau at approximately 0.85 V contributes to a first discharge capacity of ca. 197 mA h g–1, while the first charge curve exhibits two slopes in the ranges of ca. 1.1–1.3 V and 1.6–1.8 V, respectively, and a plateau at ca. 1.94 V, suggesting an irreversible change during the initial cycle. The first charge capacity is 179 mA h g–1, resulting in a high initial Coulombic efficiency of ca. 91%. Subsequent (dis)charge cycles exhibit similar electrochemical behavior, with improved discharge voltage and reduced voltage hysteresis. Conversely, when galvanostatic cycling was performed in cells with a pure APC electrolyte, the TaS3 NF electrode showed a discharge capacity of approximately 5.6 mA h g–1 in the first cycle and even less in subsequent cycles (Figure S10b). These observations align with the CV results discussed above. For comparison, the initial four (dis)charge curves of the TaS3 NF electrode in an LIB and of the bulk TaS3 electrode in an MLIB are also provided (Figure S12). The presented (dis)charge curves closely resemble those of the TaS3 NF electrode in an MLIB, indicating that the charge storage capacity of the TaS3 electrode materials in MLIB can be primarily attributed to Li+ cations.

3.

Galvanostatic cycling performance of TaS3 NF and bulk TaS3 electrodes: (a) Initial six CV curves of the self-standing TaS3 NF electrodes at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s–1 between 0.4 and 2.2 V and (b) the initial four (dis)charge curves of the same electrode at a current density of 50 mA g–1 in an MLIB. (c) Cycling performance at a current density of 50 mA g–1 (TaS3 NF in LiAPC and APC, TaS3 bulk in LiAPC), (d) variable current densities over 70 cycles (TaS3 NF and TaS3 bulk in LiAPC), and (e) at a high current density of 500 mA g–1 to evaluate long-term cycling performance (TaS3 NF and TaS3 bulk in LiAPC).

The investigation then delved into the impact of the flexible fibrous morphology on the performance of the TaS3 electrode in MLIBs. Direct fabrication of a slurry-cast electrode using the TaS3 NF film was not feasible (see Note S1 in the Supporting Information) due to its mechanical integrity. Instead, bulk TaS3 with a similar crystal structure was used as a control material. 1C is defined as 250 mA g–1, based on the theoretical capacity under the assumption of full involvement of the Ta5+/Ta3+ cationic and S(-I)/S(-II) anionic redox couples, as supported by XPS and XAS analysis (Figure ). Figure c illustrates the cyclic performance of the TaS3 NF electrode compared to its bulk material counterpart at a current density of 50 mA g–1 or 0.2 C. It is evident from the graph that TaS3 NF exhibits steady cycling behavior, retaining an excellent 91.6% of its reversible charge capacity after 100 cycles (ca. 163.5 mA h g–1 out of 178.5 mA h g–1), while the capacity of the bulk TaS3 electrode significantly diminishes to only 56.1% (111.7 mA h g–1). These results underscore the enhanced electrochemical performance derived from the uniform and interconnected nanofibrous morphology of the self-standing and binder-free TaS3 electrode material. It is worth noting that the subtle differences in the crystal structure between TaS3 NF and bulk forms may also contribute to the observed variations in electrochemical performance, albeit to a lesser extent. The integrated structure is expected to prevent material exfoliation and detachment from the matrix, thereby reducing potential inactive (“dead”) electrode parts during repeated discharge and charge cycles and maintaining a stable Li+ cation/electron transport network within the nanofibers. Indeed, it has been widely reported that free-standing interconnected electrode materials exhibit superior performance compared to conventional slurry-prepared electrodes. , However, most of these active materials in free-standing electrodes are attached to carbon nanofibers, which inevitably compromises capacity and energy density. An example of a chalcogenide electrode that does not rely on a carbon matrix is self-standing, 3-dimensional, and interconnected porous MoS2, which demonstrates superior performance in LIBs compared to other MoS2 electrode materials blended with carbon and binders. , As in the CV measurements, when using unmodified APC electrolyte, TaS3 could only deliver a negligible capacity, emphasizing the crucial role of LiCl as a provider of Li+ in the functioning of TaS3 electrode materials.

5.

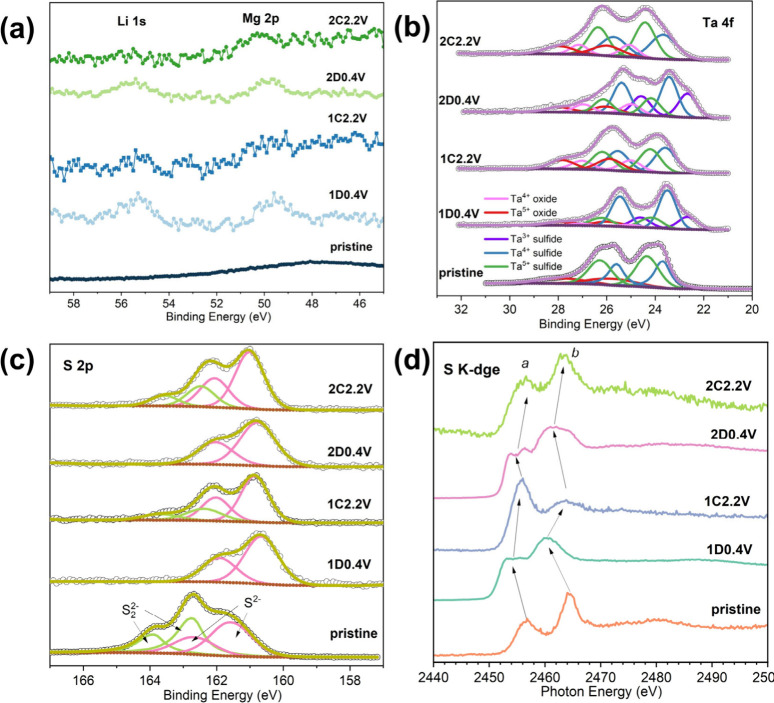

High-resolution XPS spectra of (a) Li 1s and Mg 2p, (b) Ta 4f, and (c) S 2p regions, and (d) the S K-edge XAS spectra of the TaS3 NF electrode at different (dis)charge states.

The TaS3 NF electrode also demonstrates robust rate capability compared to bulk TaS3 (Figure d). With continuously increasing current densities of 50 mA g–1 (0.2 C), 100 mA g–1 (0.4C), 200 mA g–1 (0.8C), 400 mA g–1 (1.6C), 500 mA g–1 (2C), and 1000 mA g–1 (4C) every ten cycles, TaS3 NF maintains high discharge capacities of ca. 185.5 mA h g–1, 173.7 mA h g–1, 164.9 mA h g–1, 150.0 mA h g–1, 144.4 mA h g–1, and 119.0 mA h g–1, respectively. However, the bulk TaS3 electrode delivers lower capacities of 120.7 mA h g–1 and 103.3 mA h g–1 at the higher rates of 500 mA g–1 (2C) and 1000 mA g–1 (4C), respectively. Moreover, when cycling back to low rate from high rate, the TaS3 NF electrode retains more reversible capacity (ca. 92%; 65th, 169 mA h g–1 out of fifth, 186 mA h g–1) than the bulk electrode (ca. 78%; 65th, 137 mA h g–1 out of fifth, 175 mA h g–1). The selected (dis)charge curves at various current densities in the rate measurement are provided in Figure S13. As shown in Figure e, when evaluating the long-term cycling performance at high current density (after 10 initial cycles at 0.2C), the TaS3 NF electrode exhibits a capacity of 110.7 mA h g–1 after 1000 cycles at 2C, corresponding to 73.1% of the starting capacity, while the bulk TaS3 electrode only retains 67.3% (97.2 mA h g–1 out of 144.2 mA h g–1) after approximately half the equivalent number of cycles. The results again corroborate the benefits of employing the nanofibrous, flexible TaS3 film as binder-free electrode for improving cycling stability and capacity, especially at high rates when potential structural damage from exfoliation/detachment is more pronounced.

The morphology changes that the TaS3 NFs undergo on cycling were investigated using SEM. Figure displays SEM images of TaS3 NF electrodes in the uncharged state, and after the first, second, and 50th charge/discharge cycles. The most notable evolution observed is a progressive exfoliation of the original fibers along the fiber length direction during the initial two (dis)charge cycles, resulting in the formation of numerous thin saw-like nanoribbons with a thickness of less than 100 nm and lateral sizes ranging from 200 to 500 nm. Clear evidence of electrochemical exfoliation can be observed in Figure b-e, where several peeling regions are marked with yellow dashed circles. Moreover, the detailed peeling joints and a representative example showing substantial exfoliation of large fibers are provided in Figure S14. After the 50th charge, it can be observed that the lateral size of the fibers remains of the same order of magnitude to that after the first two cycles, indicating that exfoliation mainly occurs in the early discharge and charge processes (Figures f and S14f). Photographs of the TaS3 NF electrode after the 50th charge cycle highlight that the self-standing flexibility of the film was well preserved (Figure S15), underscoring the robustness of the TaS3 NF electrode and its suitability for potential integration into wearable energy storage devices. The mechanical resilience of the electrode ensures its ability to adapt to the dynamic and deformable environments required for wearable applications, where flexibility and stable performance are critical. The morphological change, associated with the exfoliation of TaS3 NFs, is believed to result from the volume change induced by the intercalation of Li+ cations. Similar behavior has been reported in other transition metal trichalcogenides, such as TiS3, HfS3, and ZrS3. , A possible explanation is provided below. Similar to other trichalcogenides in the literature, TaS3 tends to form micro- to nanosized crystals with high aspect ratios due to its quasi-1D [TaS6] n chain structure. These chains are assembled via weak interchain interactions, which makes cleavage along planes perpendicular to the chain direction (the b-axis) relatively easy. TiS3 has previously been shown to have low theoretical cleavage energies of 0.714, 0.716, and 0.815 J m–2 to separate the [TiS6] n chains along the (101), (101̅), and (100) planes, respectively, as compared to the lowest cleavage energies of 0.320 J m–2 along the (001) planes for the exfoliation of pseudolayers, which contrast to the higher values of up to 2.706 J m–2 required to break the intrachain covalent bonds along the (010) planes. In another study, O̅nuki et al. directly observed that the width of a bulk ZrS3 single crystal along the a-axis expanded significantly after chemical lithiation using n-butyllithium solution, whereas the length along the b-axis remained nearly unchanged. These previous observations indicate that separation between chains in trichalcogenides is energetically more favorable than breaking the chains themselves. Therefore, it can be deduced that when additional stress is induced in the structure of TaS3 by the intercalation and deintercalation of Li+ ions, the weak interchain interactions allow the [TaS6] n chains to expand and separate easily. This process could lead to the exfoliation of pristine TaS3 fibers into considerably smaller ribbon crystals while maintaining high aspect ratios. The exfoliation process causes little collapse or detachment of the nanofibers/ribbons during cycling, preserving the length and high aspect ratios of the nanoribbons and maintaining the robust interconnected fibrous structure. This phenomenon helps rationalize the relatively stable cycling performance (i.e., high capacity retention after extended cycles and under high rates) of the NFs in comparison to bulk TaS3.

4.

SEM images of the TaS3 NF electrode materials in the (a) uncharged, pristine state, and after the first (b) discharge (1D0.4 V) and (c) charge (1C2.2 V), (d) the second discharge (2D0.4 V) and (e) charge (2C2.2 V), and (f) the 50th charge (50C2.2 V) cycles. The yellow dashed circles highlight the regions where exfoliations occur.

XPS was employed to investigate the presence of Li and Mg, as well as the chemical states of Ta and S during the first two (dis)charge cycles. Figure a displays the high-resolution spectra in the Li 1s and Mg 2p regions. It is evident that in the first and second discharged (1D0.4 V and 2D0.4 V) states, the Li 1s and Mg 2p peaks are present. Although the intensity and resolution in the Li 1s and Mg 2s region are relatively low, it is evident that upon charging, the intensity of the Li 1s peak noticeably decreases, while the Mg 2p peak changes very little. EDS results (Figure S16 and Table S5) of the cycled electrodes further reveal a very limited Mg content (equivalent to ca. 15 mA h g–1), along with subtle yet observable variations between the first and second cycles. This suggests that Li+ cations serves as the primary charge carriers in TaS3 NF, while Mg2+ contributes only marginally through partially reversible storage. This reversible component of Mg storage is likely associated with pseudo capacitive behavior enabled by electrochemically induced fiber thinning and increased surface accessibility after the first cycle. The fitted Ta 4f regions of the TaS3 electrode at different states are presented in Figure b. It can be observed that (the first and second) discharge of the TaS3 NF electrodes lead to the emergence of new peaks/intensity at lower binding energies of ca. 22.7 and 24.6 eV, attributable to the 4f7/2 and 4f5/2 transitions of Ta3+, respectively. As minimal changes are observed in the peak intensities of Ta4+ species within the S2 2–-containing chains - and given that the reduction of these Ta4+ species is not expected above 0.4 V, similar to TiS3 - it is inferred that Ta5+ species in the S2 2–-free chains undergo reduction to Ta3+ during discharge cycles. Upon charging, these doublet peaks shift back to higher binding energies of ca. 24.2 and 26.2 eV that represent the Ta5+ state of TaS3, suggesting reversible oxidation of Ta upon extracting Li+ ions. Peaks for Ta4+ (ca. 25.0 and 27.0 eV) and Ta5+ (ca. 25.9 and 27.9 eV) from respective oxides are also present in the spectra, possibly due to the oxidation of the electrode materials during electrode washing, handling, and the transfer to the instrument. In the S 2p region of the high-resolution spectra (Figure c), the doublet peaks for S2 2– completely disappear after the first discharge, suggesting the reduction of S(-I) to S(-II). Upon charging, S in the form of S2 2– partially recovers. The second discharge–charge cycle follows a similar pattern to the first cycle. Notably, the characteristic binding energies of S2– and S2 2– species shift to slightly lower and higher values after discharge and charge, respectively. This phenomenon was also observed in other disulfide-containing compounds (e.g., amorphous TiS4) during lithiation or delithiation, and was attributed to the increased (lower S 2p binding energy) or decreased (higher S 2p binding energy) ionic character of S2– and S2 2– species coordinated with transition metal and Li ions in the electrode compound. XAS S K-edge spectra of the TaS3 NF electrodes at various discharge and charge states were also measured for the corroboration of the S2 2–/S2– anionic redox reaction. As shown in Figure d, the XAS spectrum of the pristine TaS3 NF electrode displays a pre-edge peak at ca. 2456.6 eV (marked as “peak a”), which arises from transitions to unoccupied S 3p states hybridized with Ta 5d bands. Additionally, the other peak positioned at ca. 2464.3 eV (“peak b”) can be assigned to transitions to higher energy states, such as S 3p states hybridized with Ta 6s or 6p bands, corresponding to the complete ejection of the core electron into the continuum. After the first discharge, peak a shifts to lower photon energy and splits into two weak, overlapping peaks at ca. 2453.4 and 2455.2 eV, while peak b shifts to a lower energy position of 2460.5 eV. These peak shifts indicate an increase in the electron density around sulfur and a decrease in the effective nuclear charge, providing strong evidence for the reduction of S(-I) to S(-II) anions. The splitting of peak a is likely caused by Li+ intercalation, which alters the local electrostatic interactions of sulfur anions with tantalum d orbitals. This may involve a coordination change in tantalum, transitioning from trigonal prismatic to octahedral symmetry. Upon the first charge, peaks a and b return to their higher energy positions, with the splitting of peak a disappearing. This observation indicates the reversible oxidation of S(-II) anions back to S(-I). The behavior in subsequent cycles closely resembles that of the first cycle. These XPS and XAS results unequivocally confirm the electrochemical activity of sulfur anions and tantalum cations in the TaS3 NF electrode. Together, these findings support a dual redox mechanism in which both sulfur and tantalum contribute to charge storage with complementary roles. Analogous reaction mechanisms can be found in VS4 in MIBs, Li2TiSe3 in LIBs, and Na2FeS2 in SIBs.

To gain insight into the structural evolution during electrochemical Li+ (and trace amount of Mg2+) cation insertion/deinsertion, in operando PXRD experiments were conducted, and the data were processed and plotted as contour graphs. Figure a displays the in operando PXRD patterns of the TaS3 NF electrode during the initial three (dis)charge cycles. During the first discharge, all the peaks for TaS3 NFs progressively fade away and ultimately disappear by the end of discharge at 0.4 V. Subsequently, a new set of peaks gradually emerge at approximately 11.0°, 12.6°, 14.0°, 16.0°, 17.3°, 26.6°, 28.7°, 34.9°, 48.3°, 50.4°, and 60.3° (all 2θ), indicating the formation of (a) new lithium-intercalated phase(s). As the 1D fiber/ribbon-like morphologies of the discharged electrode material are well maintained, it could be assumed that the presence of these new peaks may correspond to the arrangement of 1D [TaS6] n chains with the incorporation of Li+ (and trace Mg2+) ions. The transmission mode ex situ PXRD patterns of the first discharged electrode and the mechanically synthesized cubic Li2TaS3 are shown in Figure S17. It is observed that the pattern of the TaS3 NF electrode shows an obvious mismatch with those of monoclinic (calculated based on monoclinic Li2NbS3) and as-made cubic Li2TaS3, indicating that the intercalation of Li+ (and trace amount of Mg2+) does not result in the formation of these phases. Therefore, these new peaks are attributed to a phase (phase M) of composition Li d Mg f TaS3 (d < 2; f ≈ 0) based on the evolution of the peaks in the subsequent cycles. During the first charging process, the peaks for phase M first shift to slightly higher angles and then disappear by the maximum cutoff voltage of 2.2 V, whereas broad scattering regions (marked by blue arrows; Figure b and Figure S18) subsequently emerge at the end of the charging process. These features indicate the formation of an amorphous TaS3-like phase (“pseudo-TaS3”) after deintercalation of most of the Li+ (and trace amounts of Mg2+) ions. However, there are still ca. 10.3 at. % of Li+ (and a trace amount of Mg2+) ions trapped in the pseudo-TaS3, possibly making the details of the local structure subtly different compared to that of the pristine TaS3 NF electrode. These observations suggest that the extraction of Li+ (and trace amounts of Mg2+) is only partially reversible. In the subsequent two cycles, phase M remains present with the (de)intercalation of Li+ (and trace Mg2+) ions, although its diffraction peak at ca. 12.6° tends to shift to a higher 2θ position. However, the scattering for pseudo-TaS3 gradually fades and eventually disappear upon extended cycling. Indeed, when the in operando PXRD patterns were collected from the 35th charged electrode (Figure S19a), pseudo-TaS3 was no longer detectable. Meanwhile, the presence of the M phase strengthened, showing a typical zigzag-style continuous variation of PXRD patterns possibly indicating a solid solution reaction within Li d Mg f TaS3 (d < 2; f ≈ 0) upon intercalation (lattice expansion) and deintercalation (lattice contraction) (Figure S19b). The Raman spectra of the TaS3 NF electrodes during the initial 2 cycles were collected and are compared in Figure c. In the spectrum of the first discharged (1D) electrode, signals for pristine TaS3 completely disappear and several new broad peaks arise, indicating a highly disordered structure in phase M. Most notably, the broad peak at approximately 425 cm–1 is attributed to Ta–S stretching mixed with Li–S bond stretching, similar to the behavior reported for Li2TiS3, while the signals at approximately 283 cm–1, 185 cm–1, and 147 cm–1 could be assigned to the Li–S vibration mode in the lithiated electrode (Li2TaS3). After charging, the vibration modes for Li2TaS3 are replaced by another set of broad peaks, which can be ascribed to highly disordered and poorly crystallized pseudo-TaS3. The reappearance of the stretching mode of disulfide bridges at approximately 490 cm–1 demonstrates the reversible S2 2–/S2– anionic redox in the TaS3 NF electrode. The second cycle exhibits similar behavior to the first cycle, except for a slight red shift of peaks, possibly due to structural adjustment resulting from the trapping of some Li+ cations in the lattice host. Although the structures of the TaS3 NF electrodes at 1D0.4 V and 2D0.4 V states differ significantly from the as-synthesized cubic Li2TaS3, their Raman spectra appear to be quite similar. Several factors could contribute to this: (a) the Raman bands are predominantly influenced by Li–S bond vibrations, which could overshadow other structural features related to Ta–S bonding and lead to spectral similarities despite the distinct structural phases; (b) the low resolution of the Raman spectra for both the highly disordered discharged TaS3 NF electrodes and cubic Li2TaS3 complicates the precise descrimination between subtle Ta–S stretching modes, potentially masking structural differences.

6.

(a) Initial three (dis)charge curves (left) of the TaS3 NF electrode obtained at a current density of 50 mA g–1 and their contour plots (right) of the corresponding in operando PXRD patterns. Note that the red marks indicate the presence of an inactive unknown minor impurity in the electrode material in operando cell, and blue marks indicate the diffraction of stainless steel from the cell casing. (b) Zoomed in operando PXRD plot taken from (a), in which red, pink, and blue arrows represent the peaks for pristine TaS3 NF, phase M, and pseudo-TaS3, respectively. (c) Raman spectra of the uncycled, the first discharge (1D0.4V), first charge (1C2.2 V), second discharge (2D0.4 V), and second charge (2C2.2 V) states of the TaS3 NF electrode.

Subsequently, a series of electrochemical techniques were employed to investigate the charge storage behavior and kinetics of the TaS3 NF electrode. To explore the charge storage mechanism electrochemically, CV experiments were conducted, and the resulting CV curves were collected at various scan rates of 0.1 mV s–1, 0.2 mV s–1, 0.3 mV s–1, 0.4 mV s–1, and 0.5 mV s–1. The experimental data presented in Figure a were analyzed using Equations S1–2. Notably, the b parameter typically ranges from 0.5 to 1.0. A b value of 1.0 (I = av) indicates pseudo capacitance-controlled behavior, while a b value of 0.5 (I = av 1/2) signifies a diffusion-controlled process. The cathodic/anodic peak currents were collected and plotted as the log values against log v accordingly (Figure b). The linear fits to these data produced b values of 0.863 ± 0.003 and 0.715 ± 0.009 for the two dominant cathodic/anodic peaks, indicating a mixed charge storage behavior. Pseudo capacitance-controlled behavior represents rapid ion adsorption and/or intercalation on the (near) surface of the nanofibers, which favors cycling performance at high current densities, while diffusion-controlled behavior represents the intercalation of Li+ cations into the bulk crystal of the TaS3 material. Similar blended charge storage mechanisms to that observed have been reported in the literature, for example, in TiNb2O7 (b = 0.816) and VS2 nanosheets (b = 0.790/0.883) in MLIBs, , and in TiO2 nanocrystals (b = 0.787 and 0.787) in MIBs.

7.

Charge storage mechanism, Li+ ion diffusion kinetics, and interfacial resistance properties of the TaS3 NF electrode: (a) CV curves obtained at different scan rates of 0.1 mV s–1 (green), 0.2 mV s–1 (orange), 0.3 mV s–1 (violet), 0.4 mV s–1 (pink), and 0.5 mV s–1 (light green), respectively. (b) Plots of the measured and fitted log reductive (green) and log oxidative (orange) peak currents against the log of scan rates v, in which the solid lines represent the linear fits (adjusted R-squared values, RR 2 = 0.9999, RO 2 = 0.9995). (c) Histogram of the separate capacitance and diffusion contributions to the charge storage at various scan rates. (d) Discharge and charge GITT curves at a current density of 25 mA g–1. (e) Plots of discharge and charge diffusivities against Li+ cation level applying the data derived from the GITT curves. (f) Measured (thin lines with open circles) and fitted (thick lines) EIS spectra for the (−)Mg|LiAPC|TaS3 NFs(+) cells after the first charge and the 20th charge cycles. The equivalent circuit is shown as an inset in the graph.

The proportion of pseudo capacitance- and diffusion-controlled charge storage was further determined using Equation S3. By linearly fitting data for i/v 1/2 against 1/v 1/2 (obtained from Figure a), both constants were derived and used to deduce the relative proportions of the pseudo capacitance- and diffusion-controlled charge storage contributions. At scan rates of 0.1 mV s–1, 0.2 mV s–1, 0.3 mV s–1, 0.4 mV s–1, and 0.5 mV s–1, the percentages of pseudo capacitance in TaS3 NF are 86%, 88%, 89%, 91%, and 91%, respectively (Figure c). The substantial proportion of pseudo capacitative charge storage suggests rapid charge transfer and ion transport occurring on the (near) surface during (dis)charge processes, particularly when the fibers were appreciably exfoliated and became increasingly thin (as observed from the electrode morphology in extended cycles). The presence of considerable pseudo capacitance undoubtedly enhances the rate performance of the TaS3 NF electrode, as evidenced by the voltage–time profiles at high current densities (discharged and charged within ca. 17 and 7 min at 500 and 1000 mA g–1, respectively; Figure S20)

To further investigate and analyze the kinetics of the Li+ ion diffusion (neglecting the trace amount of Mg2+) in the structure of the TaS3 NF electrode material, GITT experiments were conducted, with detailed procedures outlined in the Supporting Information. Subsequently, Li+ cation diffusion coefficients (D) were calculated based on Equation S4 and the as-measured GITT curves (Figure d). These values, as a function of x (Li x TaS3) at various discharge and charge states, were plotted, as depicted in Figure e. During the discharge and charge processes, diffusion coefficients range from 4.7 × 10–11 cm2 s–1 to 1.3 × 10–10 cm2 s–1 and from 6.4 × 10–12 cm2 s–1 to 9.1 × 10–11 cm2 s–1, respectively. Notably, two broad peaks reveal minimum diffusivities of 4.7 × 10–11 cm2 s–1 and 5.2 × 10–11 cm2 s–1 at discharge states approximating to “Li0.32TaS3” and “Li1.59TaS3”, respectively, suggesting a two-stage Li+ cation intercalation diffusion in the host lattice. In the charging process, as Li+ cations are extracted from the lattice, the diffusivity steadily decreases to a point of 4.3 × 10–11 cm2 s–1 after it passes a minimum diffusivity of 6.4 × 10–12 cm2 s–1. The slight disparity between the discharge and charge diffusivity profiles may stem from the slightly different Li+ ion diffusion pathways during insertion/extraction, influenced by the adjustment of the extended and local structures upon incorporating/releasing Li+ ions, a phenomenon also noted in other cases. , In short, the obtained diffusion coefficients (average D discharge of ca. 7.1 × 10–11 cm2 s–1) are comparable to or higher than other chalcogenides, such as VS4, VS2, TiS2, and MoS2, reported as cathode materials for MLIBs in the literature, ,,− indicating good ion diffusion kinetics in the TaS3 NF electrode.

EIS was conducted to elucidate the charge transfer resistance as well as interfacial properties and ion diffusion processes in the TaS3 NF electrode. Figure f and Figure S22 show the obtained Nyquist plots and corresponding equivalent circuits (fitted using Aftermath software) of three selected Mg|LiAPC|TaS3 NFs cells (before cycling, after the first charge, and after the 20th charge at a current density of 50 mA g–1). The modified Randles circuit model consists of three resistors (R0, R1, and R2), two CPEs (CPE1 and CPE2), and a Warburg impedance (W0). In the Nyquist plots, the starting point (R0) of the curve from Z r -axis represents the internal resistance caused by electrolyte, current collector, etc. The high-frequency region is modeled as a combination of resistance and capacitive elements (R1 + CPE1 in parallel), corresponding to the solid-electrolyte-interphase (SEI) film. The remaining section of the model ((CPE2 + W0) and Q2 in parallel) accounts for a blend of charge transfer and diffusion-mediated behavior in the electrodes. Detailed fitting results (Table S6) reveal significant changes in interphase resistance (R1) and charge transfer/diffusion behavior (R2 and W0). Notably, R1 decreases substantially from ca. 3296 Ω to ca. 21 Ω after the first charge, indicating a modification process involving the removal of passivation or oxidized layers on the TaS3 NF electrode and the Mg anode. After 20 cycles, the R1 element increases slightly to ca. 55 Ω, likely due to the establishment of a thickened electrolyte-electrode surface following adsorption after the interfacial modification process and exfoliation observed in the SEM results (exposing new nucleation surfaces). Regarding charge transfer/diffusion behavior, R2 decreases significantly to ca. 742 Ω after the first charge from ca. 7999 Ω in the uncycled electrode and drops further to 230 Ω after 20 cycles. Concurrently, the Warburg impedance W0 decreases continuously to ca. 146 Ω s–1/2 after 20 cycles from the initial large value (ca. 794 Ω s–1/2). These results suggest that charge transfer and Li+ cation diffusion in the TaS3 NF electrode improve gradually upon initiating the cycling measurement, owing to a so-called “activation process” involving the electrochemical cleaning of passivated or oxidized surface layers, as frequently observed in similar systems. ,

Based on the above findings, we further provide the following perspectives on the reliability of the current electrode architecture and future material design strategies. First, the self-standing fibrous architecture plays a pivotal role in the cycling stability of TaS3: it mitigates exfoliation-induced active material loss while preserving structural integrity, and simultaneously takes advantage of in situ nanosizing caused by exfoliation, which leads to shortened ion migration pathways and enhanced pseudo capacitive behavior. Second, such nondestructive exfoliation within the fibrous film framework does not progress indefinitely; rather, it is largely completed after the second cycle. This precludes the possibility that newly exposed active sites are the primary contributor to capacity retention during extended cycling. Third, although complex phase transitions occur during the initial cycles - driving exfoliation - the structural evolution becomes more homogeneous and stabilizes into a solid-solution-like behavior over prolonged cycling (Figure S18), thereby reducing further volume changes and exfoliation, as evidenced by the stable morphology after 50 cycles (Figure f). This structural stabilization also underpins the long-term cycling performance observed in our system.

However, such exfoliation-associated volume changes may present challenges in practical full-cell configurations. Moreover, the resulting in situ nanosizing can increase side reactions with the electrolyte, leading to a thicker SEI (Figure f). Future improvement may focus on a pretreatment strategy involving chemical intercalation and subsequent oxidation to produce a pre-exfoliated fiber film, which could alleviate volume changes and suppress excessive SEI formation during operation.

4. Conclusions

In this work, self-standing flexible TaS3 NF films have been synthesized using the PVT method and introduced as cathode materials in MLIBs for the first time. This electrode, devoid of carbon, binder, and supporting matrix, circumvents capacity/energy density loss resulting from inactive battery components. Moreover, the uniform structure of the film electrodes, comprised of numerous cross-linked nanofibers, ensures reliable electrical conductivity and stable charge transfer and ion transport. Consequently, the TaS3 NF electrode exhibits promising electrochemical performance, including high rate performance, very stable cycling, and superior capacity retention (91.6%), compared to powdered TaS3 (56.1%). Mechanistic studies shed light on the structure, morphology, and electrochemistry underlying the performance of the TaS3 NF electrode. Analysis of postcycle morphological changes suggests that maintaining the integrity of microstructure during exfoliation is pivotal in bringing about the excellent performance, contrasting to the powdered trisulfides, which suffer from the detachment of active materials. TaS3 NF electrodes undergo a partially reversible phase transition to form a Li2TaS3-like phase, M, in the initial cycles. This phase transition behavior gradually diminishes, with structural expansion and contraction occurring solely within phase M during extended cycling. The ion storage capacity arises from a dual redox mechanism involving the S2 2–/S2– anionic redox and the cationic couple Ta5+/Ta3+, together with a large proportion of pseudo capacitance originating from the nanosizing effect of exfoliated fibers. Additionally, the demonstrated retention of flexibility, even after extended cycling, highlights the electrode’s potential for integration into wearable energy storage devices. Although related tantalum materials such as TaS2, Ta2O5, and metallic Ta have demonstrated good biocompatibility in prior studies, − the biosafety of TaS3 specifically has yet to be systematically evaluated. Future studies involving in vitro and in vivo biological assessments are warranted to determine its suitability for such applications. This study provides the groundwork for the development of future high-performance rechargeable batteries through the design of self-standing, flexible, carbon- and binder-free electrodes, which could enable applications in next-generation flexible and wearable electronics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.H.G. and P.J. thank the University of Glasgow and the China Scholarship Council for a PhD studentship for P.J. The authors acknowledge Prof. Huimin Lu for assistance with TEM measurements (Beihang University). Dr. Christopher Kelly (University of Glasgow) is thanked for assistance with XPS measurements. Acknowledgment is also extended to the Institute for Molecular Science for providing access to the BL2A beamline of the UVSOR Synchrotron Facility, supported under the IMS Program with grant code 24IMS6007.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.5c09460.

Digital photos of synthesis and products, PXRD patterns, Rietveld refinement results, SEM images, EDS spectra, TG-DSC curves, CV curves, (dis)charge curves, and EIS spectrum (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Ragupathy P., Bhat S. D., Kalaiselvi N.. Electrochemical energy storage and conversion: An overview. WIREs Energy and Environment. 2023;12(2):e464. doi: 10.1002/wene.464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Li M., Abd El-Hady D., Alshitari W., Al-Bogami A. S., Lu J., Amine K.. Commercialization of Lithium Battery Technologies for Electric Vehicles. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019;9(27):1900161. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201900161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mu T., Wang Z., Yao N., Zhang M., Bai M., Wang Z., Wang X., Cai X., Ma Y.. Technological penetration and carbon-neutral evaluation of rechargeable battery systems for large-scale energy storage. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023;69:107917. doi: 10.1016/j.est.2023.107917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F., Hu J., Tian J., Zhou X., Li Z., Li C.. In Situ Plating of Porous Mg Network Layer to Reinforce Anode Dendrite Suppression in Li-Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10(15):12678–12689. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b00989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon J., Bucur C. B., Gregory T.. Quest for Nonaqueous Multivalent Secondary Batteries: Magnesium and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2014;114(23):11683–11720. doi: 10.1021/cr500049y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Zhao S., Li T., Su D., Guo S., Wang G.. Recent Advances in Rechargeable Magnesium-Based Batteries for High-Efficiency Energy Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020;10(21):1903591. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201903591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maroni F., Dongmo S., Gauckler C., Marinaro M., Wohlfahrt-Mehrens M.. Through the Maze of Multivalent-Ion Batteries: A Critical Review on the Status of the Research on Cathode Materials for Mg2+ and Ca2+ Ions Insertion. Batteries & Supercaps. 2021;4(8):1221–1251. doi: 10.1002/batt.202000330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. J., Cheng Y., Choi D., Dong H., Li G., Liu J., Sprenkle V. L., Yao Y.. Rechargeable Mg-Li hybrid batteries: status and challenges. J. Mater. Res. 2016;31(20):3125–3141. doi: 10.1557/jmr.2016.331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; From Cambridge University Press Cambridge Core

- Gao T., Han F., Zhu Y., Suo L., Luo C., Xu K., Wang C.. Hybrid Mg2+/Li+ Battery with Long Cycle Life and High Rate Capability. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015;5(5):1401507. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201401507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Xu H., Cui Z., Hu P., Chai J., Du H., He J., Zhang J., Zhou X., Han P.. et al. High energy density hybrid Mg2+/Li+ battery with superior ultra-low temperature performance. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2016;4(6):2277–2285. doi: 10.1039/C5TA09591C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Xu C., An Q., Wei Q., Sheng J., Xiong F., Pei C., Mai L.. Robust LiTi2(PO4)3 microflowers as high-rate and long-life cathodes for Mg-based hybrid-ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2017;5(27):13950–13956. doi: 10.1039/C7TA03392C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rashad M., Zhang H., Li X., Zhang H.. Fast kinetics of Mg2+/Li+ hybrid ions in a polyanion Li3V2(PO4)3 cathode in a wide temperature range. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2019;7(16):9968–9976. doi: 10.1039/C9TA00502A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pei C., Xiong F., Sheng J., Yin Y., Tan S., Wang D., Han C., An Q., Mai L.. VO2 Nanoflakes as the Cathode Material of Hybrid Magnesium-Lithium-Ion Batteries with High Energy Density. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9(20):17060–17066. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Xue X., Liu P., Wang C., Yi X., Hu Y., Ma L., Zhu G., Chen R., Chen T.. et al. Atomic Substitution Enabled Synthesis of Vacancy-Rich Two-Dimensional Black TiO2‑x Nanoflakes for High-Performance Rechargeable Magnesium Batteries. ACS Nano. 2018;12(12):12492–12502. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b06917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z., Zhu G., Wu H., Shi G., Xu P., Yi H., Mao Y., Wang B., Yu X.. Hydrochloric Acid-Assisted Synthesis of Highly Dispersed MoS2 Nanoflowers as the Cathode Material for Mg-Li Batteries. ACS Applied Energy Materials. 2022;5(5):6274–6281. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.2c00611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y., Zhao Y., Wang D., Yang D., Gao Y., Lian R., Chen G., Wei Y.. Fast Li+ diffusion in interlayer-expanded vanadium disulfide nanosheets for Li+/Mg2+ hybrid-ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2018;6(14):5782–5788. doi: 10.1039/C8TA00418H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Xu H., Li B., Li Z., Zhang K., Zou J., Hu Z., Laine R. M.. Using amorphous CoSx hollow nanocages as cathodes for high-performance magnesium-lithium dual-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022;598:153768. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Choi J. W., Yang Y., Jeong S., La Mantia F., Cui L.-F., Cui Y.. Highly conductive paper for energy-storage devices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106(51):21490–21494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908858106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaji N., Santhosh N. M., Zavašnik J., Nanthagopal M., Kim T., Sung J. Y., Jiang F., Jung S. P., Cvelbar U., Lee C. W.. Moving toward Smart Hybrid Vertical Carbon/MoS2 Binder-Free Electrodes for High-Performing Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023;11(8):3260–3269. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c05996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Qin X., Zhao S., Wang A., Luo J., Wang Z. L., Kang F., Lin Z., Li B.. Advanced Matrixes for Binder-Free Nanostructured Electrodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2020;32(24):1908445. doi: 10.1002/adma.201908445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Tu X., Liu Y., Zhu Y., Zhang J., Wang J., Shi R., Li L.. Morphology Engineering of VS4 Microspheres as High-Performance Cathodes for Hybrid Mg2+/Li+ Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023;15(31):37442–37453. doi: 10.1021/acsami.3c06471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.-L., Jiang Z.-H., Lu B.-R., Liu J.-T., Cao F.-H., Li H., Yu Z.-L., Yu S.-H.. MoS2 nanoplates assembled on electrospun polyacrylonitrile-metal organic framework-derived carbon fibers for lithium storage. Nano Energy. 2019;61:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang F., Cheng F., Sun Y., Yang X., Lu W., Amal R., Dai L.. Recent advances in flexible batteries: From materials to applications. Nano Research. 2023;16(4):4821–4854. doi: 10.1007/s12274-021-3820-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Britto S., Leskes M., Hua X., Hébert C.-A., Shin H. S., Clarke S., Borkiewicz O., Chapman K. W., Seshadri R., Cho J.. et al. Multiple Redox Modes in the Reversible Lithiation of High-Capacity, Peierls-Distorted Vanadium Sulfide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(26):8499–8508. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu Z., Wang C., Yi X., Chen R., Ma L., Hu Y., Zhu G., Chen T., Tie Z.. et al. Highly Branched VS4 Nanodendrites with 1D Atomic-Chain Structure as a Promising Cathode Material for Long-Cycling Magnesium Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2018;30(32):1802563. doi: 10.1002/adma.201802563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing P., Lu H., Yang W., Cao Y., Xu B., Cai W., Deng Y.. Polyaniline-coated VS4@rGO nanocomposite as high-performance cathode material for magnesium batteries based on Mg2+/Li+ dual ion electrolytes. Ionics. 2020;26(2):777–787. doi: 10.1007/s11581-019-03239-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang C., Yi X., Hu Y., Wang L., Ma L., Zhu G., Chen T., Jin Z.. Hybrid Mg/Li-ion batteries enabled by Mg2+/Li+ co-intercalation in VS4 nanodendrites. Energy Storage Materials. 2019;23:741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.ensm.2019.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O̅nuki Y., Inada R., Tanuma S., Yamanaka S., Kamimura H.. Electrochemical characteristics of transition-metal trichalcogenides in the secondary lithium battery. Solid State Ionics. 1983;11(3):195–201. doi: 10.1016/0167-2738(83)90024-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnill, C. W. Synthesis, characterisation and properties of tantalum based inorganic nanofibres; University of Glasgow: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnill C. W., Edwards H. K., Brown P. D., Gregory D. H.. Single-Step Synthesis and Surface-Assisted Growth of Superconducting TaS2 Nanowires. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45(42):7060–7063. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conny J. M., Powell C. J.. Standard test data for estimating peak parameter errors in x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy III. Errors with different curve-fitting approaches. Surf. Interface Anal. 2000;29(12):856–872. doi: 10.1002/1096-9918(200012)29:12<856::AID-SIA940>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain V., Biesinger M. C., Linford M. R.. The Gaussian-Lorentzian Sum, Product, and Convolution (Voigt) functions in the context of peak fitting X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) narrow scans. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;447:548–553. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.03.190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AfterMath; Pine Research Instrumentation: 2023. https://pineresearch.com/shop/kb/knowledge-category/downloads/

- Mayorga-Martinez C. C., Sofer Z., Luxa J., Huber Š., Sedmidubský D., Brázda P., Palatinus L., Mikulics M., Lazar P., Medlín R.. et al. TaS3 Nanofibers: Layered Trichalcogenide for High-Performance Electronic and Sensing Devices. ACS Nano. 2018;12(1):464–473. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b06853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K., Chen B., Cai H., Blei M., Bennett J., Yang S., Wright D., Shen Y., Tongay S.. Unusual Pressure Response of Vibrational Modes in Anisotropic TaS3 . J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;121(50):28187–28193. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b10263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma D. D., Rao C. N. R.. XPES studies of oxides of second- and third-row transition metals including rare earths. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1980;20(1):25–45. doi: 10.1016/0368-2048(80)85003-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet M. E., Harmer S. L., Liu X., Nesbitt H. W.. Polarized X-ray absorption spectroscopy and XPS of TiS3: S K- and Ti L-edge XANES and S and Ti 2p XPS. Surf. Sci. 2005;584(2):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2005.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Momma K., Izumi F.. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011;44(6):1272–1276. doi: 10.1107/S0021889811038970. (acccessed 2024/12/23) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Tang Q., Liu Y., Zhu Y., Zhang J., Wang J., Shi R.. Anion vacancy engineering in carbon coating VS4 microspheres assembled by nanorod arrays for high-performance rechargeable Mg-Li hybrid batteries. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2024;497:154966. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.154966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Yang D., He T., Li J., Wei L., Wang D., Wang Y., Wang X., Chen G., Wei Y.. Vacancy engineering in VS2 nanosheets for ultrafast pseudocapacitive sodium ion storage. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2021;421:129715. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.129715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, B. Digital Micrograph. In Transmission Electron Microscopy: Diffraction, Imaging, and Spectrometry, Carter, C. B. , Williams, D. B. , Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2016; pp 167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y.-E., Huang Y., Zhang L., Fan W., Lai F., Liu T.. Electrospun porous carbon nanofiber@MoS2 core/sheath fiber membranes as highly flexible and binder-free anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Nanoscale. 2015;7(25):11093–11101. doi: 10.1039/C5NR02711J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Lin C.-C., Wu C., Qaiser N., Cai Y., Lu A.-Y., Qi K., Fu J.-H., Chiang Y.-H., Yang Z.. et al. Three-dimensional hierarchically porous MoS2 foam as high-rate and stable lithium-ion battery anode. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):6006. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33790-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P., Zhang W., Hu X., Yuan L., Huang Y.. Synthesis of hierarchical MoS2 and its electrochemical performance as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2014;2(10):3498–3504. doi: 10.1039/C3TA13994H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chianelli R. R., Dines M. B.. Reaction of butyllithium with transition metal trichalcogenides. Inorg. Chem. 1975;14(10):2417–2421. doi: 10.1021/ic50152a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]