Abstract

Background

Teacher well-being in primary and secondary schools is crucial to ensuring sustainable development in the field of education, and it is an important topic that needs attention in the management of primary and secondary schools in China. The leadership style of school administrators plays a key role in enhancing teacher well-being. This study aimed to explore the mechanism of spiritual leadership on teacher well-being and to test the mediating effects of teachers’ trust in leaders as well as organizational justice in this relationship.

Methods

This study utilized a non-probability purposive sampling method and a web-based questionnaire to survey 311 primary and secondary school teachers in China. In order to validate the research model, this study used Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and analyzed the collected data using SmartPLS 4.0 software.

Results

It was found that spiritual leadership positively and significantly affected teacher well-being. Teachers’ trust in leaders played a positive mediating role between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being. Although spiritual leadership positively and significantly affected organizational justice, organizational justice did not have a significant effect on teacher well-being, and lastly, the mediating effect of organizational justice between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being was not supported. Additionally, the variables of spiritual leadership, teachers’ trust in leaders, and organizational justice collectively explained 47.9% of the variance in teacher well-being.

Conclusions

The findings enriched the research on spiritual leadership and teacher well-being and deepened the understanding of the relationship between them. Spiritual leadership should be actively cultivated and promoted in primary and secondary school management practices to enhance teachers’ trust in leaders, thereby effectively enhancing teacher well-being in primary and secondary schools.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-025-03039-7.

Keywords: Spiritual leadership, Teacher well-being, Teachers’ trust in leaders, Organizational justice

Introduction

In the background of China’s new era, enhancing teacher well-being in primary and secondary schools is a key foundation for realizing moral education and improving the quality of education [1]. Teacher well-being refers to the sustained experience of happiness brought about by teachers’ satisfaction in life and work, enhanced professional development, and realization of professional ideals [2]. Teacher well-being is not only crucial to teachers’ personal development, but also a “barometer” for schools to understand the status of internal management, which can help improve the quality of education and teaching in schools [3]. However, in China, primary and secondary school teachers’ workload, title evaluation, and other pressures have led to the phenomenon of “involution” becoming more and more serious, which in turn generates anxiety, uneasiness, panic, and other emotions, and teacher well-being is not experienced as high [4]. Therefore, how to improve teacher well-being and create a healthier working environment to ensure the sustainable development of the complex and dynamic field of education has become an important issue for primary and secondary school administrators in China [5]. To improve teacher well-being in primary and secondary school teachers, numerous scholars have begun to explore the various factors affecting teacher well-being, which are mainly categorized into the internal factors of the teachers themselves and the external environmental factors in which the teachers live [6].

In recent years, the leadership style of school administrators has been found to be an influential external environmental factor in teacher well-being [7–9]. In China, school administrators, as the core leaders of school development, not only determine the direction and organizational climate of the school, but also have a direct relationship with the working environment and psychological state of teachers [10]. Research has shown that the leadership style of school administrators significantly influence teachers’ organizational citizenship behavior [11], affective commitment [12], and professional calling [13]. Being a new style of leadership, spiritual leadership focuses on subordinates’ emotions, values, and beliefs, and motivates subordinates’ intrinsic motivation through motivation, inspiration, and guidance to achieve organizational goals [14]. The research revealed that spiritual leadership had a favorable impact on enhancing teacher well-being [15, 16]. This may provide a new way of thinking about education management in Chinese primary and secondary schools, namely, to create a more humanized management style by developing spiritual leadership, thus effectively enhancing teacher well-being and promoting the healthy development of education.

Trust is an indispensable prerequisite and cornerstone in the interpersonal interaction between school administrators and teachers. Research reveals that teachers’ trust in leaders has a significant impact on explaining and predicting their performance [17]. Teachers’ trust in leaders is effective in promoting their professional growth [18], enhancing self-efficacy [19], and increasing job satisfaction [20]. Teachers’ trust in leaders is seen as an important intrinsic predictor of teacher well-being [21].

Organizational justice is seen as an external motivator that effectively predicts people’s organizational behavior [22, 23]. Improving organizational justice can facilitate school organizational functioning and increase teachers’ positive feelings and behaviors in the organization, such as organizational commitment [24], organizational identification [25], and organizational citizenship behaviors [26], which, in turn, enhances teacher well-being [27].

Despite the growing scholarly attention to the relationship between leadership style and teacher well-being, the mechanisms by which spiritual leadership influences teacher well-being have not been fully explored in comparison to other leadership styles, and in particular, there is a lack of systematic examination of mediating pathways [15]. Self-determination theory implies that personal behavior stem from an interplay between internal factors and the external environment. The external environment indirectly shapes an individual’s behavioral performance through its effect on their external and internal motivation (e.g., external motivations such as organizational justice, intrinsic motivations such as trust in leaders) [28]. This reveals that spiritual leadership as an important organizational contextual factor may have a conductive effect on teacher well-being through the dual paths of teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice, but the mediating mechanism is still a theoretical black box.

In view of this, based on the Chinese educational organizational context and using self-determination theory as a framework, this study aimed to explore the interrelationships among spiritual leadership, teachers’ trust in leaders, organizational justice, and teacher well-being, and to further validate the potential mediating roles of teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice in the relationship between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being. By systematically analyzing the role of leadership styles in influencing teacher well-being, this study not only reveals the generative mechanism of teacher well-being at the theoretical level, but also provides a scientific decision-making basis for optimizing the effectiveness of governance in primary and secondary schools and promoting the enhancement of teacher professional well-being at the practical level.

Literature review and research hypothesis

Spiritual leadership and teacher well-being

Spiritual leadership, as an emerging leadership style, emphasizes on the leader’s ability to motivate self and team members by intrinsically motivating them so that they feel spiritually existent grounded in their mission and membership [14]. The core trait of spiritual leadership, as compared to other leadership styles, is its focus on and care for the spiritual dimension of team members. Spiritual leadership includes three dimensions: vision, hope or faith, and altruistic love [14]. Research has shown that spiritual leadership positively predicts corporate employee well-being [29, 30], and also has a positive and significant effect on the well-being of nurses [31] and civil servants [32]. In the field of education, there are relatively few studies exploring the link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being. However, the findings of Samar and Chaudhary [16] and Li et al. [33] showed that spiritual leadership is a positive predictor of teacher well-being. Self-determination theory suggests that the fulfillment of basic psychological needs is key in determining an individual’s well-being [34]. School spiritual leadership focuses on shaping a shared school vision and setting specific and challenging goals as a way to raise teachers’ expectations and commitment to their educational endeavors and to inspire a sense of professional mission [13] and positive attitudes toward the future [35]. By giving teachers hope and confidence in realizing their vision, they can work steadfastly towards their set goals even when they encounter setbacks and difficulties, which helps to enhance their psychological resilience [36] and self-efficacy [37]. In addition, the selfless care and support of spiritual leadership helps to build an atmosphere of trust, tolerance, love, and harmony, and such a team environment provides teachers with a sense of emotional security, which enhances their psychological capital [38] and job satisfaction [33]. Thus, spiritual leadership may be able to effectively meet the basic psychological needs of teachers [39] by shaping a mission vision, inspiring hope and faith, and manifesting altruistic concern, thereby enhancing their well-being.

Therefore, this study proposes hypotheses:

H1: Spiritual leadership positively and significantly affects teacher well-being.

The mediating role of teachers’ trust in leaders

Teachers’ trust in leaders refers to the psychological state in which teachers have favorable expectations of school administrators and believe that administrators will care for their interests, protect their rights, and take uncertain risks [40]. The relationship between teachers and school administrators is an important factor in driving sustained change inside the school [41]. Teachers’ trust in leaders is particularly critical in this relationship because it directly affects teachers’ attitudes and behaviors toward assigned tasks [42]. Research has shown that leadership behavior has a significant effect on teachers’ trust in leaders [19, 43, 44]. Nonetheless, the relationship between spiritual leadership and teachers’ trust in leaders has not been extensively studied. However, several other leadership styles, such as transformational leadership [20], ethical leadership [45], and distributed leadership [46], have been found to significantly increase teachers’ trust in leaders. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that spiritual leadership may also have a positive and significant effect on teachers’ trust in leaders. By shaping a shared vision and leading by example, school spiritual leadership helps them reach their personal development goals while pursuing school goals. Such leadership prompts teachers to actively internalize organizational goals into personal values, inspires intrinsic motivation and a sense of belonging, satisfies teachers’ basic psychological needs [47], which builds a solid sense of trust within the teacher community.

And when teachers are in an organization with an atmosphere of trust, they feel a sense of teacher well-being because of the mutual trust of their school, colleagues, and leaders [17]. Based on their trust in leaders, teachers increase their identification with a sense of meaning in teaching and learning, and are more likely to actively accept and positively perform the tasks given by school leaders [48], creating a sustained intrinsic motivation. In the process of performing tasks, they increase work engagement and decrease emotional burnout [49]. This trust-based collaboration not only fosters the smooth running of educational activities, but also enhances teachers’ sense of commitment and belonging to the educational endeavor [50]. In this way, teachers fulfill their values in teaching practice, experience a sense of accomplishment and enjoyment in their educational work [20], and ultimately achieve a deeper level of well-being.

Therefore, the research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2

Spiritual leadership positively and significantly affects teachers’ trust in leaders.

Hypothesis 3

Teachers’ trust in leaders positively and significantly affects teacher well-being.

Hypothesis 4

Teachers’ trust in leaders mediates the link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being.

The mediating role of organizational justice

Organizational justice is an indispensable factor for the stability and sustainable development of organizations, which ensures the fair flow of resources among organizations [51]. The teachers organizational justice refers to the school in the teaching of front-line teachers in school management, resource allocation, and relevant decisions involving fairness feelings [52]. School administrators play a crucial role in creating a fair culture in school organizations. Research has found that leadership styles such as inclusive leadership [53] and ethical leadership [54] have a significant positive impact on improving organizational justice. Similarly, spiritual leadership has been shown to directly and positively influence teachers organizational justice [55]. Spiritual leadership attach importance to fairness, ethics and value issues, and they tend to be group-oriented and committed to creating a fair organizational environment [56]. Under this leadership style, every teacher is treated fairly and equally. In the aspects of benefit distribution, organizational procedure formulation and interpersonal relationship handling, spiritual leadership can ensure fairness, justice and transparency, thus effectively promoting the realization of organizational justice [57].

The cultural atmosphere of organizational justice can directly or indirectly affect the behavior and effect of individual employees in specific situations [22]. Self-determination theory emphasizes that the external environment influences behavioral outcomes through motivational internalization mechanisms. When extrinsic motivation is perceived as autonomy-supportive by the individual, it can be translated into self-identified norms [58]. It is found that organizational justice is positively correlated with teachers’ job autonomy, and positively and significantly affects teacher well-being [59]. Spiritual leadership builds fair and transparent institutional environments, reduces teachers’ anxiety due to ambiguous rules or favoritism [60], and facilitates the internalization of extrinsic motivation by enabling teachers to view external constraints as autonomous choices rather than forced obedience [61]. When teachers are in a fair and just cultural atmosphere, they are more deeply aware of the consistency of individual contribution and return and the school’s recognition of individual contribution [62]. At the same time, the transparent decision-making process also enhances teachers’ sense of control and participation, making them more confident and satisfied with the school [63]. Such a cultural atmosphere also helps to improve the quality of communication and interaction among teachers and between teachers and school administrators, make teachers feel respected and supported, and enhance their satisfaction of emotional needs and well-being [64].

Therefore, the research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5

Spiritual leadership positively and significantly affects teachers organizational justice.

Hypothesis 6

Teachers organizational justice positively and significantly affects teacher well-being.

Hypothesis 7

Teachers organizational justice mediates the link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being.

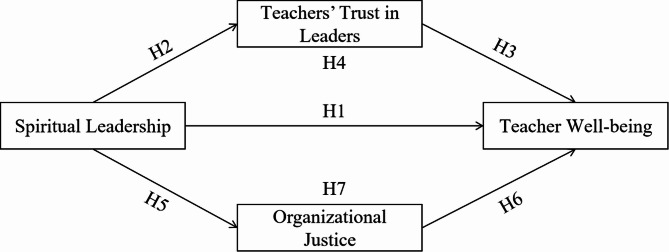

Self-determination theory emphasizes that the external environment influences behavioral outcomes by regulating the internalization of extrinsic motivation and the maintenance of intrinsic motivation together [65]. Spiritual leadership as an external environmental factor facilitates the internalization of extrinsic motivation by adjusting a fair institutional environment that provides a stable environmental base for psychological need satisfaction, which leads teachers to automatically comply with teaching rules [66]; Teachers’ trust in leaders serves as an emotional link to basic psychological need satisfaction, allowing teachers to more actively internalize organizational goals as self-motivation and stimulating intrinsic interest in their work [41]. Extrinsic motivation reduces behavioral conflict through internalization, and intrinsic motivation is consistently reinforced by need satisfaction, thus satisfying teachers’ basic psychological needs and enhancing their well-being [58] Therefore, based on self-determination theory, this present study aims to explore the intrinsic mechanism of spiritual leadership’s effect on teacher well-being in primary and secondary schools, and to verify the mediating effect of teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice in this process. This is of great significance for improving school management, enhancing teacher well-being in primary and secondary schools, and promoting the sustainable development of schools and teachers. The mediation model developed in this present study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical model

Methods

Subjects and steps of the study

Non-probability purposive sampling was used in this study and data were collected using an online questionnaire. The researcher posted the questionnaire on the online platform and sent the generated questionnaire link or QR code to the respondents. Respondents anonymously participated in this study by clicking on the questionnaire link or scanning the QR code. Guidance notes were provided in the questionnaire and respondents were notified that involvement in the study was voluntary and they could opt out at any stage of completing the questionnaire. If respondents completed the questionnaire, they were considered to have tacitly agreed to participate in this study. A total of 311 primary and secondary school teachers from public schools in Shandong Province, China volunteered to participate. Kline [67] suggested that a sample size exceeding 200 is generally considered large and suitable for most research models. Therefore, the sample size of this research is adequate. Of the total participants, 248 were female and 63 were male. The age distribution was as follows: <25 years old (n = 13), 25 ~ 35 years old (n = 106), 36–45 years old (n = 128) ≥ 46 years old (n = 64). Regarding professional titles, 122 teachers have junior titles, 162 teachers have intermediate titles, and 27 teachers have senior titles. There were 17 people with college degrees, 275 with bachelor’s degrees, and 19 with master’s degrees. There were 281 primary school teachers, and 30 secondary school teachers.

Research tools

Teacher well-being

Teacher well-being was measured using the Employee Well-Being Scale developed by Chinese scholars Zheng et al. [68]. The scale has three dimensions: life well-being (LWB), workplace well-being (WWB) and psychological well-being (PWB). Studies have shown that the scale is suitable for measuring primary and secondary school teacher well-being [69, 70]. The scale consists of 18 items and the answers are scored on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 to 7, indicating strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher scores on the scale demonstrate greater teacher well-being. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for LWB, WWB and PWB in this study were 0.913, 0.916 and 0.904 respectively.

Spiritual leadership

Spiritual leadership was assessed with the Spiritual Leadership Scale by Fry [14] as revised by Tang et al. [71] based on the Chinese context. The scale has three dimensions: vision (VI), hope/faith (HO), and altruistic love (AL). The researchers made educational contextualizations in using the scale. Research has shown that the scale is suitable for the Chinese educational system [13]. The scale contains 14 items, and the responses are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, denoting strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher scores on the scale indicate a better role of spiritual leadership style. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for VI, HO and AL in this study were 0.929, 0.894 and 0.930 respectively.

Teachers’ trust in leaders

Teachers’ trust in leaders (TTL) was measured using the Subordinates’ Trust in Leaders Scale developed by Brockner et al. [72] revised by Li and Yang [73] based on the Chinese cultural context. The study showed that the scale is suitable for measuring primary and secondary school teachers’ trust in leaders [74]. The scale comprises of 3 items, with responses rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher scores on the scale indicate greater teachers’ trust in leaders. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.952.

Organizational justice

Organizational justice was assessed with the Organizational Justice Scale developed by Niehoff and Moorman [51], which was revised by He [75] based on the Chinese cultural context. The scale has three dimensions: distributive justice (DJ), interactional justice (IJ) and procedural justice (PJ). Research has shown that the scale is suitable for measuring organizational justice among elementary and secondary school teachers [76, 77]. The scale consists of 14 items, with responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher scores on the scale indicate a greater sense of organizational justice among teachers. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for DJ, IJ, and PJ in this study were 0.826, 0.936, and 0.89, respectively.

Data analysis

This study employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to validate the research model, as it aligns with the study’s aim of theory development and prediction [78]. PLS-SEM is particularly suited for maximizing explained variance (R²) and forecasting relationships among constructs, rather than solely testing established theories. The choice is further justified by the model’s complexity, which includes mediating effects and formative higher-order constructs - elements that PLS-SEM can accommodate but CB-SEM cannot [79]. Moreover, PLS-SEM allows for the use of both formative and reflective measurement models, unlike CB-SEM which is limited to reflective constructs [80]. Considering the above factors, where the research model involves both reflective and formative constructs, we have decided to use PLS-SEM for this study. This study focused on analyzing the data samples in a two-step approach using SmartPLS 4.0 software [81]. First, measurement models were assessed, including reflective and formative measurement models. Second, the structural model was validated, focusing on assessing the significance and relevance of the path coefficients and assessing the explanatory power of the model [82].

Results

Common method bias

Common method bias is prone to occur when respondents are required to answer questions on both exogenous and endogenous variables when completing self-reported questionnaires [83, 84]. Avoiding this situation, two approaches were used in this study: procedural approach and statistical approach. In the procedural approach aspect, the researcher clearly informed the respondents that the data collected remained anonymous and that there were no right or wrong options in the questionnaire. In addition, the scales were carefully designed to be categorized into different scoring ranges. As for statistical analysis, this study used the full collinearity test proposed by Kock [85]. If the value of the variance inflation factor (VIF) exceeds 5, this means that there is a serious covariance problem. However, as shown in Table 1, all the values of VIF are below 5, so it can be determined that there is no serious covariance problem in this study.

Table 1.

Full collinearity testing

| VI | HO | AL | TTL | DJ | IJ | PJ | LWB | WWB | PWB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.140 | 2.356 | 1.820 | 2.277 | 1.332 | 2.769 | 2.602 | 2.197 | 2.948 | 3.034 |

Measurement model

Since the current research model contains three formative second-order constructs (spiritual leadership, organizational justice, and teacher well-being), this study used a two-stage approach to assess the measurement model [79].

Reflective measurement model

In assessing the reliability of the indicators using loading, it was found that the loading values of all indicators were in the range of 0.623–0.965, which is greater than the acceptable threshold of 0.5 [82] as shown in Table 2. This indicates that the reliability of the indicators is satisfactory. The values of Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR) for all constructs ranged from 0.826 to 0.969, surpassing the threshold of 0.7, indicating good internal consistency reliability [79] The values of Average Variance Extraction (AVE) were all above 0.5, which meets the criteria for convergent validity [86]. To test discriminant validity, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was employed. From Table 3, the square root of the mean variance extracted for each indicator was higher than its correlations with other variables, indicating the presence of appropriate discriminant validity [86].

Table 2.

Construct reliability and convergent validity assessment

| Construct | Item Code | Outer Loading | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vision (VI) | 0.929 | 0.947 | 0.780 | ||

| VI1 | 0.826 | ||||

| VI2 | 0.898 | ||||

| VI3 | 0.894 | ||||

| VI4 | 0.913 | ||||

| VI5 | 0.883 | ||||

| Hope/faith (HO) | 0.894 | 0.922 | 0.704 | ||

| HO1 | 0.825 | ||||

| HO2 | 0.901 | ||||

| HO3 | 0.754 | ||||

| HO4 | 0.831 | ||||

| HO5 | 0.878 | ||||

| Altruistic Love (AL) | 0.930 | 0.945 | 0.713 | ||

| AL1 | 0.910 | ||||

| AL2 | 0.882 | ||||

| AL3 | 0.848 | ||||

| AL4 | 0.917 | ||||

| AL5 | 0.623 | ||||

| AL6 | 0.880 | ||||

| AL7 | 0.814 | ||||

| Teachers’ trust in leaders (TTL) | 0.952 | 0.969 | 0.912 | ||

| TTL1 | 0.963 | ||||

| TTL2 | 0.965 | ||||

| TTL3 | 0.937 | ||||

| Distributive Justice (DJ) | 0.826 | 0.884 | 0.657 | ||

| DJ1 | 0.763 | ||||

| DJ2 | 0.810 | ||||

| DJ3 | 0.858 | ||||

| DJ4 | 0.808 | ||||

| Interactional Justice (IJ) | 0.936 | 0.949 | 0.757 | ||

| IJ1 | 0.884 | ||||

| IJ2 | 0.879 | ||||

| IJ3 | 0.896 | ||||

| IJ4 | 0.897 | ||||

| IJ5 | 0.833 | ||||

| IJ6 | 0.829 | ||||

| Procedural Justice (PJ) | 0.892 | 0.925 | 0.756 | ||

| PJ1 | 0.863 | ||||

| PJ2 | 0.849 | ||||

| PJ3 | 0.905 | ||||

| PJ4 | 0.859 | ||||

| Life Well-being (LWB) | 0.913 | 0.933 | 0.701 | ||

| LWB1 | 0.835 | ||||

| LWB2 | 0.834 | ||||

| LWB3 | 0.880 | ||||

| LWB4 | 0.874 | ||||

| LWB5 | 0.880 | ||||

| LWB6 | 0.709 | ||||

| Workplace Well-being (WWB) | 0.916 | 0.935 | 0.704 | ||

| WWB1 | 0.829 | ||||

| WWB2 | 0.861 | ||||

| WWB3 | 0.852 | ||||

| WWB4 | 0.817 | ||||

| WWB5 | 0.839 | ||||

| WWB6 | 0.837 | ||||

| Psychological well-being (PWB) | 0.904 | 0.926 | 0.677 | ||

| PWB1 | 0.775 | ||||

| PWB2 | 0.815 | ||||

| PWB3 | 0.858 | ||||

| PWB4 | 0.860 | ||||

| PWB5 | 0.862 | ||||

| PWB6 | 0.760 |

Table 3.

Discriminant validity assessment (Fornell-Larcker)

| AL | DJ | HO | IJ | LWB | PJ | PWB | TTL | VI | WWB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 0.844 | |||||||||

| DJ | 0.610 | 0.810 | ||||||||

| HO | 0.736 | 0.567 | 0.839 | |||||||

| IJ | 0.758 | 0.649 | 0.613 | 0.870 | ||||||

| LWB | 0.431 | 0.469 | 0.505 | 0.389 | 0.837 | |||||

| PJ | 0.777 | 0.678 | 0.615 | 0.834 | 0.414 | 0.869 | ||||

| PWB | 0.428 | 0.381 | 0.674 | 0.353 | 0.645 | 0.331 | 0.822 | |||

| TTL | 0.694 | 0.499 | 0.673 | 0.630 | 0.499 | 0.611 | 0.527 | 0.955 | ||

| VI | 0.777 | 0.558 | 0.793 | 0.684 | 0.556 | 0.675 | 0.554 | 0.767 | 0.883 | |

| WWB | 0.524 | 0.522 | 0.637 | 0.489 | 0.693 | 0.445 | 0.734 | 0.576 | 0.659 | 0.839 |

Formative measurement model

Spiritual leadership [87], organizational justice [88], and teacher well-being [68] is a reflective-formative second-order structure. In formative measurement modeling, redundancy analysis was used to assess convergent validity [79]. That is, the relationship between the formative measurement construct and a single global item is assessed. Therefore, at the questionnaire design stage, this study included single global items on spiritual leadership, organizational justice, and teacher well-being in the questionnaire. Hair et al. [79] concluded that the relationship between formative measurement constructs and single global items should be 0.708 or higher. Table 4 shows that the relationships between spiritual leadership, organizational justice, and teacher well-being and single global items are 0.824, 0.790, and 0.850, respectively, which are higher than 0.708 as defined by Hair et al. [79]. The results indicate that the three formative measurement models, spiritual leadership, organizational justice, and teacher well-being, have been established with convergent validity.

Table 4.

Formative measurement model assessment

| Constructs higher-order | Constructs lower-order | Convergent validity | Outer Weight | Sample Mean | T Value | P Value | Outer Loading | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spiritual Leadership (SL) |

VI | 0.824 | 0.516 | 0.515 | 7.770 | 0.000 | 0.956 | 3.344 |

| HO | 0.228 | 0.227 | 2.659 | 0.008 | 0.882 | 2.942 | ||

| AL | 0.340 | 0.341 | 5.770 | 0.000 | 0.898 | 2.631 | ||

|

Organizational Justice (OJ) |

DJ | 0.790 | 0.355 | 0.354 | 4.561 | 0.000 | 0.848 | 1.913 |

| IJ | 0.445 | 0.446 | 4.479 | 0.000 | 0.925 | 3.110 | ||

| PJ | 0.314 | 0.310 | 3.296 | 0.001 | 0.917 | 3.450 | ||

|

Teacher Well-being (TWB) |

LWB | 0.850 | 0.174 | 0.176 | 1.532 | 0.126 | 0.798 | 2.077 |

| WWB | 0.630 | 0.630 | 6.147 | 0.000 | 0.965 | 2.638 | ||

| PWB | 0.291 | 0.283 | 2.320 | 0.020 | 0.868 | 2.367 |

VIF was used to assess indicator covariance. As can be seen in Table 4, the values of VIF were in the range of 1.913–3.344, which are less than 5, demonstrating that there is no serious issue of covariance [79]. T-value was used to assess the significance of indicator weights. In this study, the significance level was set at 5% and if the T-value is higher than 1.960 (two-tailed test) it indicates that the indicator weights are statistically significant [82]. The data in Table 4 found that the T-values for all other indicators met the specified thresholds, except for LWB. Although the T-value for LWB was not significant, the loadings for this indicator were greater than 0.5, and according to the recommendations of Hair et al. [86], this indicator should be retained. This study also assessed the correlation of the indicator weights, being normalized to values between − 1 and + 1, consistent with the range of intervals recommended by Hair et al. [86].

Structural model

Considering that covariance may lead to instability in PLS-SEM assessment, the covariance issue was examined in this study before performing structural modeling tests. As shown in Table 5, all the VIF values ranging from 1.000 to 3.984 were less than 5, indicating that the covariance problem was not serious [82].

Table 5.

Structural model assessment

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Beta | Se | T values | P values | LL | UL | R 2 | f2 | VIF | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SL -> TWB | 0.578 | 0.096 | 6.035 | 0.000 | 0.374 | 0.750 | 0.479 | 0.162 | 3.984 | Supported |

| H2 | SL -> TTL | 0.782 | 0.026 | 29.965 | 0.000 | 0.729 | 0.831 | 0.610 | 1.574 | 1.000 | Supported |

| H3 | TTL -> TWB | 0.171 | 0.077 | 2.211 | 0.027 | 0.023 | 0.322 | 0.022 | 2.590 | Supported | |

| H4 | SL -> TTL -> TWB | 0.134 | 0.062 | 2.174 | 0.030 | 0.018 | 0.258 | Supported | |||

| H5 | SL -> OJ | 0.788 | 0.025 | 31.585 | 0.000 | 0.737 | 0.835 | 0.620 | 1.643 | 1.000 | Supported |

| H6 | OJ -> TWB | -0.030 | 0.088 | 0.342 | 0.732 | -0.194 | 0.156 | 0.001 | 2.659 |

Not Supported |

|

| H7 | SL -> OJ -> TWB | -0.024 | 0.070 | 0.341 | 0.733 | -0.151 | 0.123 |

Not Supported |

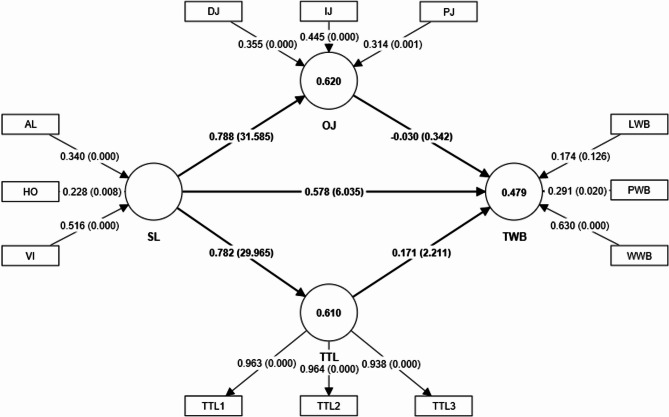

Bootstrapping 5000 was used to evaluate the significance of the hypothesized effects at the 0.95 confidence level, and the results are shown in Table 5; Fig. 2. Assessing the significance of the path coefficients can be judged either by the T-value or the confidence interval. A T-value above 1.960 (two-tailed test) when the significance level is 5% indicates that the path is statistically significant [79]. Alternatively, confidence intervals that do not include 0 similarly indicate that the pathway is statistically significant [79].

Fig. 2.

The final mediation model

Five direct hypotheses were in total tested in this study and according to the PLS-SEM results, four research hypotheses were supported and one was not supported. (H1) Spiritual leadership has a positive and significant effect on teacher well-being (β = 0.578, t = 6.035, p = 0.000). (H2) Spiritual leadership has a positive and significant effect on teachers’ trust in leaders (β = 0.782, t = 29.965, p = 0.000). (H3) Teachers’ trust in leaders has a positive and significant effect on teacher well-being (β = 0.171, t = 2.211, p = 0.027). (H5) Spiritual leadership has a positive and significant effect on organizational justice (β = 0.788, t = 31.585, p = 0.000). (H6) Organizational justice has no significant effect on teacher well-being (β=-0.030, t = 0.342, p = 0.732). In order to improve the predictive power of this study, two mediating variables were introduced within the research framework, which were teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice. The results showed that (H4) the indirect effect of teachers’ trust in leaders on the link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being was positive and significant (β = 0.134, t = 2.174, p = 0.030). (H7) The indirect effect of organizational justice on the link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being is not significant (β=-0.024, t = 0.341, p = 0.733).

The results of data analysis in Table 5 show that exogenous variables have strong explanatory power for endogenous variables in the framework of this study. The variables of spiritual leadership, teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice together explained 47.9% of the variance in teacher well-being. Spiritual leadership had a strong explanatory power of 61.0% and 62.0% for teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice, respectively. According to the effect size criteria proposed by Cohen [89], the explanatory strength is described as small, medium, and large when the R2 values are 0.02, 0.13, and 0.26, respectively. As a result, it can be judged that all endogenous variables in this study exhibit a large explanatory strength. The effect size is determined by the f2 value and can be categorized as small (0.02), medium (0.15), and large (0.35) [89]. The results showed that spiritual leadership had a large effect on teachers’ trust in leaders (f2 = 1.574) and organizational justice (f2 = 1.643), spiritual leadership had a medium effect on teacher well-being (f2 = 0.162), and teachers’ trust in leaders had a small effect on teacher well-being (f2 = 0.022).

Following the suggestion of Shmueli et al. [90], the PLS predict program was run to estimate the measurement error by comparing the root mean square error (RMSE) of the PLS and the linear model (LM), which in turn evaluates the predictive ability of the model. As recommended by Hair et al. [86], when most of the values of PLS-SEM_RMSE are less than the values of LM_RMSE, it shows that the model has medium predictive ability. As can be seen from Table 6, except for PJ4 and PWB4, the values of PLS-SEM_RMSE are less than the value of LM_RMSE, which indicates that the model constructed in this study has medium predictive ability.

Table 6.

PLS predict

| Indicators | Q²predict | PLS-SEM_RMSE | LM_RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| DJ1 | 0.196 | 0.828 | 0.862 |

| DJ2 | 0.215 | 0.842 | 0.868 |

| DJ3 | 0.364 | 0.638 | 0.647 |

| DJ4 | 0.236 | 0.760 | 0.788 |

| IJ1 | 0.522 | 0.570 | 0.574 |

| IJ2 | 0.433 | 0.615 | 0.644 |

| IJ3 | 0.480 | 0.584 | 0.596 |

| IJ4 | 0.449 | 0.579 | 0.607 |

| IJ5 | 0.387 | 0.625 | 0.649 |

| IJ6 | 0.380 | 0.665 | 0.697 |

| LWB1 | 0.202 | 1.032 | 1.074 |

| LWB2 | 0.243 | 1.073 | 1.117 |

| LWB3 | 0.234 | 1.176 | 1.223 |

| LWB4 | 0.211 | 1.102 | 1.149 |

| LWB5 | 0.176 | 1.171 | 1.216 |

| LWB6 | 0.182 | 1.610 | 1.626 |

| PJ1 | 0.419 | 0.623 | 0.650 |

| PJ2 | 0.409 | 0.678 | 0.693 |

| PJ3 | 0.522 | 0.613 | 0.628 |

| PJ4 | 0.476 | 0.566 | 0.565 |

| PWB1 | 0.240 | 0.941 | 0.978 |

| PWB2 | 0.291 | 0.896 | 0.912 |

| PWB3 | 0.303 | 0.905 | 0.933 |

| PWB4 | 0.365 | 0.814 | 0.812 |

| PWB5 | 0.379 | 0.852 | 0.870 |

| PWB6 | 0.271 | 1.006 | 1.037 |

| TTL1 | 0.562 | 0.776 | 0.824 |

| TTL2 | 0.576 | 0.781 | 0.812 |

| TTL3 | 0.509 | 0.854 | 0.888 |

| WWB1 | 0.276 | 1.202 | 1.244 |

| WWB2 | 0.353 | 1.100 | 1.125 |

| WWB3 | 0.317 | 1.107 | 1.151 |

| WWB4 | 0.329 | 1.081 | 1.092 |

| WWB5 | 0.308 | 1.048 | 1.062 |

| WWB6 | 0.325 | 1.078 | 1.087 |

Discussion

This study’s primary purpose was to reveal the link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being and to explore the role of teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice as mediators in this relationship.

Direct effect of spiritual leadership on teacher well-being

The current study found that the relationship between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being is confirmed in the teacher groups, supporting the views of Hunsaker [91] and Li et al. [92]. An important feature of spiritual leadership is to construct a vision that is consistent between subordinates and the organization, give subordinates hope and confidence that the vision will be achieved, selfless care, and make subordinates have a sense of membership and mission to improve individual and organizational performance [93]. Therefore, teacher burnout is alleviated through spiritual leadership that fulfills teachers’ psychological needs, gives them hope and faith, and enables them to experience pleasure in work and life [94], thus achieving work, life, and psychological well-being. This suggests that spiritual leadership is a key external contributor in enhancing teacher well-being, which extends the understanding and contribution to the role of spiritual leadership and well-being in the field of education.

Mediating effect of teachers’ trust in leaders

The current study indicated that teachers’ trust in their leaders mediated the link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being, and research hypotheses 2, 3, and 4 were supported. This means that spiritual leadership is effective in enhancing teacher well-being due to the mediating effect of teachers’ trust in leaders. The present study analyzed in depth the relatively neglected area of the link between spiritual leadership and teachers’ trust in leaders. It was found that spiritual leadership, like transformational leadership [95] and distributed leadership [96], had a significant impact on enhancing teachers’ trust in leaders. Spiritual leadership builds the foundation of teachers’ trust in leaders on a psychological level by portraying a clear vision that provides teachers with a common goal and direction that fulfills their search for meaning in their work [97]. Spiritual leadership inspires teachers’ optimism [98] and work engagement [99] by demonstrating unwavering hope and belief, and this positive future vision and intrinsic motivation contributes to a sense of trust. Spiritual leadership’s selfless care and support for teachers strengthens teachers’ emotional trust and social exchange [100], making teachers feel respected and valued, which in turn enhances their teachers’ trust in leaders in schools. When teachers’ trust in leaders, they are more inclined to be proactive in accepting the guidance of leaders and their values [101]. This helps to increase their identification and engagement with the school’s goals and culture, which in turn stimulates teachers’ intrinsic motivation [19], pushes them to strive for continuous improvement in their professional development and personal fulfillment [44], and experience more positive emotions and well-being in their work and personal lives [102].

Mediating effects of organizational justice

The current study found that spiritual leadership has a positive predictive effect on organizational justice, and research hypothesis 5 was supported, a result that is consistent with what previous research [66] has suggested. School administrators’ behaviors directly or indirectly affect organizational justice in the process of building an organizational cultural climate, developing and implementing rules and regulations, and daily administration [57]. Spiritual leadership in schools is concerned with the growth and well-being of teachers, and tends to allocate resources equitably and ensure procedural fairness. At the same time spiritual leadership focuses on the needs of teachers and personalizes their care, which fosters a trusting relationship between leaders and teachers’ trust in leaders and promotes interactive equity [55].

However, the study showed that organizational justice did not have a significant effect on teacher well-being, while it also failed to mediate between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being, and research hypotheses 6 and 7 were not supported. This result differs from the findings of Liang and Gao [103]. This suggests that although organizational justice is seen as an important factor in the work environment, it does not appear to directly determine teacher well-being, nor does it play the expected mediating role between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being. This finding suggests that teacher well-being is influenced by a combination of complex factors, and that organizational justice is only one of many factors whose influence may not be as strong as expected. Moreover, teachers’ perceptions of organizational justice vary according to individual differences [104] and cultural differences [105]. It is also possible that certain factors moderate the relationship between organizational justice and teacher well-being, such as perceived organizational support [106, 107], school culture [108, 109], teacher autonomy [110, 111]. These factors may have contributed to the fact that organizational justice did not have a significant effect on teacher well-being in this study. However, when teachers perceive no organizational justice, this may have a negative impact on their work attitudes, behaviors, and overall well-being [112]. Therefore, when enhancing teacher well-being, we should comprehensively consider other potential factors including job satisfaction [33], social support [113], and burnout [114] to comprehensively promote teacher well-being. At the same time, we need to take steps to ensure organizational justice in order to reduce the sense of unfairness and teacher well-being experienced by teachers.

Conclusions and implications

Conclusions

By using PLS-SEM, this study analyzed survey data from 311 Chinese primary and secondary school teachers, aiming to investigate the effects of spiritual leadership on primary and secondary school teacher well-being and to test the mediating effects of teachers’ trust in leaders as well as organizational justice in this context. The results of the study show that:

(1) Direct effects: This study confirms a significant positive correlation between spiritual leadership, teachers’ trust in leaders and primary and secondary school teacher well-being, while the effect of organizational justice on teacher well-being is not significant. It was also found that spiritual leadership positively predicts teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice.

(2) Indirect effect: This study deeply explored the mechanism of spiritual leadership on teacher well-being and found that spiritual leadership indirectly had a positive predictive effect on teacher well-being through the mediating variable of teachers’ trust in leaders. However, organizational justice did not play a mediating role between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being.

Theoretical implications

This study has important theoretical implications. Firstly, this study broadens the contextual applicability of spiritual leadership theory. Although Chinese scholars have conducted relevant research on spiritual leadership, it is still insufficient compared to the West, especially in the field of education. While most of the existing research on spiritual leadership focuses on corporations, this study shifts the focus to the Chinese basic education scenario and verifies its effectiveness in primary and secondary school organizations in a collectivist culture. This provides a new empirical basis for cross-cultural leadership research and also injects new theoretical perspectives into the field of educational administration. Secondly, although existing studies have explored the effects of leadership styles on teacher well-being, research on the specific relationship between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being is still insufficient. By analyzing the effects of spiritual leadership on teacher well-being, this study not only clarifies the direct relationship between the two, but also reveals the mediating role played in it by teachers’ trust in leaders, highlighting the critical role of trust as an emotional bond in leadership effectiveness.These findings further enrich and deepen our understanding of the intrinsic link between spiritual leadership and teacher well-being, making the relationship clearer. Finally, this study expands the boundaries of the application of self-determination theory in the field of educational administration. Using self-determination theory as a framework and spiritual leadership as an external environmental factor, this study reveals the mechanism by which organizational leadership style affects teacher well-being, and provides a new empirical basis for the application of self-determination theory in school organizational management.

Practical implications

From the perspective of leadership, this study reveals that spiritual leadership not only directly enhances teacher well-being, but also indirectly enhances it by increasing teachers’ trust in leaders. This finding provides a practical path for enhancing teacher well-being, which has important application value. Firstly, primary and secondary schools should actively nurture and promote spiritual leadership. Schools should offer specialized leadership training courses for spiritual leaders to assist school administrators in deeply understanding and practicing the core ideas and methods of spiritual leadership; Schools need to focus on creating an organizational culture that emphasizes shared vision, mission, and altruism to provide strong environmental support and atmosphere for the growth of spiritual leadership; In terms of talent selection and leadership assessment, spiritual leadership should be taken as an important indicator. Secondly, primary and secondary school administrators should make “trust” a key cornerstone of leadership effectiveness. School administrators should adhere to the principle of fairness and impartiality in resource allocation and title evaluation, create a supportive communication environment, establish a regular communication mechanism, and encourage teachers to actively participate in the decision-making process in order to enhance trust in their leaders and belonging to the organization.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Although the research explored how spiritual leadership enhances teacher well-being in primary and secondary schools in the context of Chinese education and revealed its underlying mechanisms, there are still shortcomings that need to be improved in the future research. Firstly, as the research used a questionnaire to collect cross-sectional data, this may have affected the reliability of the findings to some extent. Future research could consider adopting diversified research tools such as longitudinal research methods as well as mixed methods, thus ensuring more objective and robust findings. Secondly, the sampling method of the present research has certain limitations that affect the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the research sample is limited to Shandong, China, which does not adequately represent the national situation. Future research could consider adopting a stratified sampling method while expanding the geographic area and coverage of subjects to ensure that the findings are more generalizable and practical. Finally, there are numerous influencing factors in exploring the impact of spiritual leadership on teacher well-being. In this study, only teachers’ trust in leaders and organizational justice were selected as mediating variables to be explored. Future studies could further explore other potential mediating and moderating variables in depth; Also, there is a need to explore whether moderating variables such as perceived organizational support, school culture, and teacher autonomy exist between organizational justice and teacher well-being.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AL

Altruistic love

- DJ

Distributive justice

- HO

Hope/faith

- IJ

Interactional justice

- LWB

Life well-being

- OJ

Organizational justice

- PJ

Procedural justice

- PWB

Psychological well-being

- SL

Spiritual leadership

- TTL

Teachers’ trust in leaders

- TWB

Teacher well-being

- VI

Vision

- WWB

Workplace well-being

Author contributions

Jing Li and Soon-Yew Ju had the research idea, conceptualised and designed the research. Shuang Li, Xiaodong Peng and Wei Zhang collected and curated the data. Jing Li wrote the main manuscript text. Nana Jiang and Man Li reviewed and edited the paper. Lai-Kuan Kong and Soon-Yew Ju supervised the process. All authors have read and approved the final draft.

Funding

Jing Li was funded by the teachers’ visiting training grant for ordinary undergraduate colleges and universities in Shandong Province, China.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Heze University Ethics Committee conducted a comprehensive assessment on January 8, 2024 and approved the study design based on the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. We obtained written informed consent for this investigation from primary and secondary school teachers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Song H, Lin M, Ou Y, Wang X. Reframing teacher well-being: a case study and a holistic exploration through a Chinese lens. Teachers Teach. 2024;30(6):818–34. 10.1080/13540602.2023.2285874. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao R. The current situation of Chinese primary and secondary school teacher well-being: an investigation and strategies. Chin J Special Educ. 2019;3:90–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ao N, Zhang S, Tian G, et al. Exploring teacher wellbeing in educational reforms: a Chinese perspective. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1265536. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1265536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu RX, Wu JQ, Cha YZ, et al. A study on the current situation of teachers’ professional happiness in primary and secondary schools. Educational Sci Forum. 2023;20:54–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang W, Song H, Sun R. Can a professional learning community facilitate teacher well-being in china?? The mediating role of teaching self-efficacy. Educational Stud. 2022;48(3):358–77. 10.1080/03055698.2020.1755953. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian J, Mao YQ, Tian ZH, et al. The influence of transformational leadership on teachers’ well-being: the mediating role of social emotional competence and teacher-student relationship. J Educational Stud. 2021;3:154–65. 10.14082/j.cnki.1673-1298.2021.03.013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali AYS, Dahie AM. Leadership style and teacher job satisfaction: empirical survey from secondary schools in Somalia. Leadership. 2015;5(8):33–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallego-Nicholls JF, Pagán E, Sánchez-García J, et al. The influence of leadership styles and human resource management on educators’ well-being in the light of three sustainable development goals. Acad Revista Latinoam De Administración. 2022;35(2):257–77. 10.1108/ARLA-07-2021-0133. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meidelina O, Saleh AY, Cathlin CA, et al. Transformational leadership and teacher well-being: a systematic review. J Educ Learn (EduLearn). 2023;17(3):417–24. 10.11591/edulearn.v17i3.20858. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong JW. Thoughts and practices on enhancing the governance ability of primary and secondary school principals toward the goal of education modernization. People’s Educ. 2024;Z2:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shie EH, Chang SH. Perceived principal’s authentic leadership impact on the organizational citizenship behavior and well-being of teachers. Sage Open. 2022;12(2):21582440221095003. 10.1177/21582440221095003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarence M, Devassy VP, Jena LK, et al. The effect of servant leadership on ad hoc schoolteachers’ affective commitment and psychological well-being: the mediating role of psychological capital. Int Rev Educ. 2021;67(3):305–31. 10.1007/s11159-020-09856-9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Ju SY, Kong LK, et al. A study on the mechanism of spiritual leadership on burnout of elementary and secondary school teachers: the mediating role of career calling and emotional intelligence. Sustainability. 2023;15(12):9343. 10.3390/su15129343. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry LW. Introduction to the leadership quarterly special issue: toward a paradigm of spiritual leadership. Leadersh Q. 2005;5:619–22. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Ju SY. The correlation between spiritual leadership and the well-being of Chinese primary and secondary school teachers. Int J Acad Res Progressive Educ Dev. 2023;12(2):1667–81. 10.6007/IJARPED/v12-i2/17251. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samar S, Chaudhary AH. A study of relationship between spiritual leadership and workplace well-being of teachers in secondary schools, Lahore Pakistan. Al-Idah. 2021;39(2):21–31. 10.37556/al-idah.039.02.0726. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkovich I. Typology of trust relationships: profiles of teachers’ trust in principal and their implications. Teachers Teach. 2018;24(7):749–67. 10.1080/13540602.2018.1483914. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendawy Al-Mahdy YF, Hallinger P, Emam M, et al. Supporting teacher professional learning in oman: the effects of principal leadership, teacher trust, and teacher agency. Educational Manage Adm Leadersh. 2024;52(2):395–416. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng X, Yin H, Liu Y. The relationship between distributed leadership and teacher efficacy in china: the mediation of satisfaction and trust. Asia-Pacific Educ Researcher. 2019;28:509–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eliophotou-Menon M, Ioannou A. The link between transformational leadership and teachers’ job satisfaction, commitment, motivation to learn, and trust in the leader. Acad Educational Leadersh J. 2016;20(3):12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu P, Chen XF, Cheng YX, et al. Understanding the relationship between teacher leadership and teacher well-being: the mediating roles of trust in leaders and teacher efficacy. J Educational Adm. 2023;61(6):646–61. 10.1108/JEA-09-2022-0152. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balven R, Fenters V, Siegel DS, et al. Academic entrepreneurship: the roles of identity, motivation, championing, education, work-life balance, and organizational justice. Acad Manage Perspect. 2018;32(1):21–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deschamps C, Rinfret N, Lagacé MC, et al. Transformational leadership and change: how leaders influence their followers’ motivation through organizational justice. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61(3):194–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jehanzeb K, Mohanty J. The mediating role of organizational commitment between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: power distance as moderator. Personnel Rev. 2020;49(2):445–68. 10.1108/PR-09-2018-0327. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terzi AR, Dülker AP, Altin F, et al. An analysis of organizational justice and organizational identification relation based on teachers’ perceptions. Univers J Educational Res. 2017;5(3):488–95. 10.13189/ujer.2017.050320. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong LNT, Phuong NND. Organizational justice, job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior in higher education institutions: a research proposition in Vietnam. J Asian Finance Econ Bus. 2018;5(3):113–9. 10.13106/jafeb.2018.vol5.no3.113. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrera C, Torres-Vallejos J, Martínez-Líbano J, et al. Perceived collective school efficacy mediates the organizational justice effect in teachers’ subjective well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10963. 10.3390/ijerph191710963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

- 29.Hunsaker WD. Spiritual leadership and work-family conflict: mediating effects of employee well-being. Personnel Rev. 2021;50(1):143–58. 10.1108/PR-04-2019-0143. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srivastava S, Mendiratta A, Pankaj P, et al. Happiness at work through spiritual leadership: a self-determination perspective. Empl Relations: Int J. 2022;44(4):972–92. 10.1108/ER-08-2021-0342. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou W, Zeng Y, Peng Q, et al. The influence of spiritual leadership on the subjective well-being of Chinese registered nurses. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2020;28(6):1432–42. 10.1111/jonm.13106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang CL, Arisanti I. How does spiritual leadership influences employee well-being? Findings from PLS-SEM and FsQCA. Emerg Sci J. 2022;6(6):1358–74. 10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-06-09. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Ju SY, Kong LK, et al. How spiritual leadership boosts elementary and secondary school teacher well-being: the chain mediating roles of grit and job satisfaction. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(23):20742–53. 10.1007/s12144-024-05803-1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan RM, Deci EL. The darker and brighter sides of human existence: basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychol Inq. 2000;11(4):319–38. 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_03. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang M, Guo T, Ni Y, et al. The effect of spiritual leadership on employee effectiveness: an intrinsic motivation perspective. Front Psychol. 2019;9:2627. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed SS, Khan MM, ur Rahman M. Unlocking employees resilience in turbulent times: the role of spiritual leadership and meaning. Continuity Resil Rev. 2023;5(3):249–61. 10.1108/CRR-12-2022-0036. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L, Wen T, Wang J, et al. The impact of spiritual leadership on employee’s work engagement - a study based on the mediating effect of goal self-concordance and self-efficacy. Int J Mental Health Promotion. 2022;24(1):69–84. 10.32604/ijmhp.2022.018932. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abou Zeid MAG, El-Ashry AM, Kamal MA, et al. Spiritual leadership among nursing educators: a correlational cross-sectional study with psychological capital. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):377. 10.1186/s12912-022-01163-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Yang F, Gao NN. Enhancing career satisfaction: the roles of spiritual leadership, basic need satisfaction, and power distance orientation. Curr Psychol. 2022;41:1856–67. 10.1007/s12144-020-00712-5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Mossholder KW. Examining the effects of trust in leaders: a bases-and-foci approach. Leadersh Q. 2010;21(1):50–63. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansor AN, Abdullah R, Jamaludin KA. The influence of transformational leadership and teachers’ trust in principals on teachers’ working commitment. Humanit Social Sci Commun. 2021;8(1):1–9. 10.1057/s41599-021-00985-6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Çoban Ö, Özdemir N, Bellibaş MŞ. Trust in principals, leaders’ focus on instruction, teacher collaboration, and teacher self-efficacy: testing a multilevel mediation model. Educational Manage Adm Leadersh. 2023;51(1):95–115. 10.1177/1741143220968170. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kars M, Inandı Y. Relationship between school principals’ leadership behaviors and teachers’ organizational trust. Eurasian J Educational Res. 2018;18(74):145–64. 10.14689/ejer.2018.74.8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karacabey MF, Bellibaş MŞ, Adams D. Principal leadership and teacher professional learning in Turkish schools: examining the mediating effects of collective teacher efficacy and teacher trust. Educational Stud. 2022;48(2):253–72. 10.1080/03055698.2020.1749835. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vikaraman SS, Mansor AN, Hamzah MIM. Influence of ethical leadership practices in developing trust in leaders: a pilot study on Malaysian secondary schools. Int J Eng Technol. 2018;7(330):444–8. 10.14419/ijet.v7i3.30.18348. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bektaş F, Kılınç AÇ, Gümüş S. The effects of distributed leadership on teacher professional learning: mediating roles of teacher trust in principal and teacher motivation. Educational Stud. 2022;48(5):602–24. 10.1080/03055698.2020.1793301. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haque MJ, Nawaz MZ, Shaikh HA, Tariq MZ. Spiritual leadership and unit productivity: does psychological need mediate the relationship between spiritual leadership and unit productivity? Public Integr. 2021;24(7):615–28. 10.1080/10999922.2021.1957271. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayer RC, Gavin MB. Trust in management and performance: who Minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Acad Manag J. 2005;48(5):874–88. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-083025. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dworkin AG, Tobe PF. The effects of standards based school accountability on teacher burnout and trust relationships: a longitudinal analysis. Trust and school life: The role of trust for learning, teaching, leading, and bridging. 2014; 121–143. 10.1007/978-94-017-8014-8_6

- 50.Thomsen M, Karsten S, Oort FJ. Distance in schools: the influence of psychological and structural distance from management on teachers’ trust in management, organisational commitment, and organisational citizenship behaviour. School Eff School Improv. 2016;27(4):594–612. 10.1080/09243453.2016.1158193. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niehoff BP, Moorman RH. Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad Manag J. 1993;36(3):527–56. 10.5465/256591. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou XH, Li WJ. The relationship between occupational well-being, organizational justice and psychological capital of preschool teachers. Occup Health. 2020;36(14):1939–42. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tran TBH, Choi SB. Effects of inclusive leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating roles of organizational justice and learning culture. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2019;13:e17. 10.1017/prp.2019.10. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halbusi H, Williams KA, Mansoor HO, et al. Examining the impact of ethical leadership and organizational justice on employees’ ethical behavior: does person - organization fit play a role? Ethics Behav. 2020;30(7):514–32. 10.1080/10508422.2019.1694024. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jassmy BAK, Mahdi SK. Spiritual leadership and its impact on organizational justice: an analytical study of opinions of a sample of teaching staff in Iraqi private universities in the middle euphrates provinces. AL-Qadisiyah J Administrative Economic Sci. 2022; 24(3).

- 56.Nedaei M, Ramzgooyan G. Effectiveness of spiritual leadership and organizational justice on the commitment and administrative integrity in Iranian National tax administration. Trans Data Anal Social Sci. 2021;3(1):1–13. 10.47176/TDASS/2021.1. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaid ZS, Adriani Z, Solikhin A. The influence of spiritual leadership on individual performance: the role of organizational culture as a mediation. J Bus Stud Manage Rev. 2024;7(2):139–50. 10.22437/jbsmr.v7i2.35223. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghanbari S, Norollahee S, Jabbari Zohd F. The effect of organizational justice on job well-being of teachers mediated by job autonomy among elementary teachers of Hamedan City. Psychol Researches Manage. 2024;10(3):135–60. 10.22034/jom.2024.2032007.1220. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zeng XP, Chen YW. A research on illegitimate tasks, job autonomy, organizational justice and job anxiety——Inspired by standardization management. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Conference on E-business, Management and Economics (ICEME ‘22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2022; 556–562. 10.1145/3556089.3556096

- 61.Zhao S, Ma Z, Li H, Wang Z, Wang Y, Ma H. The impact of organizational justice on turnover intention among primary healthcare workers: the mediating role of work motivation. Risk Manage Healthc Policy. 2024;17:3017–28. 10.2147/RMHP.S486535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Capone V, Petrillo G. Teachers’ perceptions of fairness, well-being and burnout: a contribution to the validation of the organizational justice index by Hoy and tarter. Int J Educational Manage. 2016;30(6):864–80. 10.1108/IJEM-02-2015-0013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao JX, Wu MM. Research on the impact of organizational justice on employees’ work well-being. J North Polytechnic Univ. 2021;33(02):16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bakhtiari E, Sabahi P, Karami A, Saffarinia M. The effect of perceived organizational justice and organizational norms on teacher’s psychological well-being. J Sch Psychol. 2021;9(4):2–19. 10.32598/JSPI.9.4.1. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annual Rev Organizational Psychol Organizational Behav. 2017;4:19–43. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barkhoda J, Asadi M, Zabardast MA. Effect of spiritual leadership of principals on spirituality at work: mediating role of organizational justice. School Adm. 2018;5(2):255–76. https://doi.org/1JSA-1705-1148(R1). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kline RB. Beyond significance testing: reforming data analysis methods in behavioural research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng XM, Zhu WC, Zhao HX, Zhang C. Employee well-being in organizations: theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J Organizational Behav. 2015;36(5):621–44. 10.1002/job.1990. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang W, He E, Mao Y, Pang S, Tian J. How teacher social-emotional competence affects job burnout: the chain mediation role of teacher-student relationship and well-being. Sustainability. 2023;15(3):2061. 10.3390/su15032061. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhai Y, Xiao W, Sun C, Sun B, Yue G. Professional identity makes more work well-being among in-service teachers: mediating roles of job crafting and work engagement. Psychol Rep. 2023;00332941231189217. 10.1177/00332941231189217. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Tang Z, Zhang H, Zhao JJ, Wang MH. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the spiritual leadership scale. Psychol Res. 2014;7(02):68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brockner J, Siegel PA, Daly JP, Tyler T, Martin C. When trust matters: the moderating effect of outcome favorability. Adm Sci Q. 1997;42(3):558–83. 10.2307/2393738. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li J, Yang Z. The impact mechanism of authoritarian leadership on group voice climate. Bus Manage J. 2018;40(06):53–68. 10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2018.06.004. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Handford V, Leithwood K. Why teachers trust school leaders. J Educational Adm. 2013;51(2):194–212. 10.1108/09578231311304706. [Google Scholar]

- 75.He X. Why employees know but don’t speak: an empirical study on localization of employee silence behavior. Nankai Manage Rev. 2010; (3): 45–52.

- 76.Liu S, Hallinger P. The effects of instructional leadership, teacher responsibility and procedural justice climate on professional learning communities: a cross-level moderated mediation examination. Educational Manage Adm Leadersh. 2024;52(3):556–75. 10.1177/17411432221089185. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang S, Long R, Bowers AJ. Supporting teacher knowledge sharing in china: the effect of principal authentic leadership, teacher psychological empowerment and interactional justice. Educational Manage Adm Leadersh. 2022;17411432221120330. 10.1177/17411432221120330.

- 78.Akter S, Fosso Wamba S, Dewan S. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Prod Plann Control. 2017;28(11–12):1011–21. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dash G, Paul J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2021;173:121092. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(3):411–23. 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017.

- 83.Ngah AH, Zainuddin Y, Thurasamy R. Barriers and enablers in adopting of Halal warehousing. J Islamic Mark. 2015;6(3):354–76. 10.1108/JIMA-03-2014-0027. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff N. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann Rev Psychol. 2012;63(1):539–69. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kock N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collaboration. 2015;11(4):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: a workbook. Springer Nat. 2021. 10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract. 2011;19(2):139–52. 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang M, Fry L. The role of spiritual leadership in reducing healthcare worker burnout. J Manage Spiritual Relig. 2018;15(4):305–24. 10.1080/14766086.2018.1482562. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shmueli G, Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah JH, Ting H, Vaithilingam S, Ringle CM. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur J Mark. 2019;53(11):2322–47. 10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hunsaker WD. Spiritual leadership and job burnout: mediating effects of employee well-being and life satisfaction. Manage Sci Lett. 2019;9:1257–68. 10.5267/j.msl.2019.4.016. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li J, Ju SY, Kong LK. The effect of spiritual leadership on primary and secondary school teachers’ professional well-being: the mediating role of career calling. J Nusantara Stud (JONUS). 2024;9(1):294–319. 10.24200/jonus.vol9iss1pp294-319. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fry LW, Latham JR, Clinebell SK, Krahnke K. Spiritual leadership as a model of performance excellence: a study of Baldrige award recipients. J Manage Spiritual Relig. 2017;14(1):22–47. 10.1080/14766086.2016.1202130. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ardhani MA, Aini Q. The effect of spiritual leadership and spiritual intelligence on low nurse burnout in a hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Venez Farmacol Ter. 2022;41:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jain P, Duggal T, Ansari AH. Examining the mediating effect of trust and psychological well-being on transformational leadership and organizational commitment. Benchmarking: Int J. 2019;26(5):1517–32. 10.1108/BIJ-07-2018-0191. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu L, Liu P, Yang H, Yao H, Thien LM. The relationship between distributed leadership and teacher well-being: the mediating roles of organisational trust. Educational Manage Adm Leadersh. 2024;52(4):837–53. 10.1177/17411432221113683. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tsui KT, Lee JCK, Zhang Z, Wong PH. The relationship between teachers’ perceived spiritual leadership and organizational commitment: a multilevel analysis in the Hong Kong context. Asian J Social Sci Humanit. 2019;8(3):55–72. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen G, Huang C. The influence of spiritual leadership on job satisfaction: the mediating effect of employee’s optimism and the moderating effect of Machiavellian personality. Proc 2022 2nd Int Conf Mod Educational Technol Social Sci (ICMETSS 2022). 2022;634–647. 10.2991/978-2-494069-45-9_77.

- 99.Sheikh AA, Inam A, Rubab A, Najam U, Rana NA, Awan HM. The spiritual role of a leader in sustaining work engagement: a teacher-perceived paradigm. Sage Open. 2019;9(3):2158244019863567. 10.1177/21582440198635. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pradesa HA, Tanjung H. The effect of principal’s spiritual leadership dimension on teacher affective commitment. Al-Tanzim: Jurnal Manajemen Pendidikan Islam. 2021;5(3):69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Islam MN, Furuoka F, Idris A. Mapping the relationship between transformational leadership, trust in leadership and employee championing behavior during organizational change. Asia Pac Manage Rev. 2021;26(2):95–102. 10.1016/j.apmrv.2020.09.002. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kelloway EK, Turner N, Barling J, Loughlin C. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: the mediating role of employee trust in leadership. Work Stress. 2012;26(1):39–55. 10.1080/02678373.2012.660774. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liang HM, Gao MJ. An empirical study on the impact of perceived justice of professional development on teachers’ occupational cognitive well-being. Mod Educational Manage. 2021;990. 10.16697/j.1674-5485.2021.09.012.

- 104.Minibas-Poussard J, Le Roy J, Erkmen T. The moderating role of individual variables in the relationship between organizational justice and organizational commitment. Personnel Rev. 2017;46(8):1635–50. 10.1108/PR-12-2015-0311. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Najafi H, KHaleghkhah A. The prediction of perceived organizational justice of teachers based on the components of organizational culture: A new strategy for improving school management. School Adm. 2019;7(2):148–65. 10.34785/J010.2019.785. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Masyhuri M, Pardiman P, Siswanto S. The effect of workplace spirituality, perceived organizational support, and innovative work behavior: the mediating role of psychological well-being. J Econ Bus Account Ventura. 2021;24(1):63–77. 10.14414/jebav.v24i1.2477. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Twumasi E, Addo B. Perceived organisational support as a moderator in the relationship between organisational justice and affective organisational commitment. Econ Cult. 2020;17(2):22–9. 10.2478/jec-2020-0017. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Erdogan B, Liden RC, Kraimer ML. Justice and leader-member exchange: the moderating role of organizational culture. Acad Manag J. 2006;49:395–406. 10.5465/amj.2006.20786086. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Erkutlu H. The moderating role of organizational culture in the relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2011;32(6):532–54. 10.1108/01437731111161058. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Haar JM, Spell CS. How does distributive justice affect work attitudes? The moderating effects of autonomy. Int J Hum Resource Manage. 2009;20(8):1827–42. 10.1080/09585190903087248. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rousseau V, Salek S, Aubé C, Morin EM. Distributive justice, procedural justice, and psychological distress: the moderating effect of coworker support and work autonomy. J Occup Health Psychol. 2009;14(3):305–17. 10.1037/a0015747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mota AI, Lopes J, Oliveira C. The burnout experience among teachers: a profile analysis. Psychol Sch. 2023;60(10):3979–94. 10.1002/pits.22956. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Turner K, Thielking M, Prochazka N. Teacher wellbeing and social support: a phenomenological study. Educational Res. 2022;64(1):77–94. 10.1080/00131881.2021.2013126. [Google Scholar]