Abstract

Elimination of malaria will require new drugs with potent activity against Plasmodium falciparum mature stage V gametocytes, the only stages infective to the mosquito vector. The identification and comprehensive validation of molecules active against these quiescent stages is difficult due to the specific biology of gametocytes, challenges linked to their cultivation in vitro and the lack of animal models suitable for evaluating the transmission-blocking potential of drug candidates in vivo. Here, we present a transmission-blocking drug discovery and development platform that builds on transgenic NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 parasites engineered to conditionally produce large numbers of stage V gametocytes expressing a red-shifted firefly luciferase viability reporter. Besides developing a robust in vitro screening assay for the reliable identification of stage V gametocytocidal compounds, we also establish a preclinical in vivo malaria transmission model based on infecting female humanized NODscidIL2Rγnull mice with pure NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes. Using whole animal bioluminescence imaging, we assess the in vivo gametocyte killing and clearance kinetics of antimalarial reference drugs and clinical drug candidates and identify markedly different pharmacodynamic response profiles. Finally, we combine this mouse model with mosquito feeding assays and thus firmly establish a valuable tool for the systematic in vivo evaluation of transmission-blocking drug efficacy.

Subject terms: Parasite development, Phenotypic screening, Animal disease models, Malaria

Current antimalarials often fail to target mature stage V gametocytes. To aid antimalarial drug discovery, the authors present a preclinical malaria transmission-blocking drug research platform, using engineered parasites, that facilitates the screening for gametocytocidal compounds in vitro and the evaluation of transmission-blocking drug activity in vivo.

Introduction

Half of the world’s population lives at risk of contracting malaria, a devastating infectious disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium and transmitted by female Anopheles spp. mosquitoes. Over 95% of the global 249 million malaria cases and 608,000 deaths reported for 2022 were caused by P. falciparum1. Upon injection of sporozoites into the skin via an infectious mosquito bite and a first round of parasite multiplication inside hepatocytes, P. falciparum colonizes the human blood. Here, merozoites invade red blood cells (RBCs) and develop intracellularly through the ring and trophozoite stage before mitotic replication via schizogony produces up to 32 daughter merozoites that egress from the infected RBC (iRBC) to invade new erythrocytes. Continued repetition of these 48-hour replication cycles is responsible for all malaria symptoms and chronic infection. At the same time, a small proportion of parasites produced during each round of replication commit to gametocytogenesis via an epigenetic switch that activates expression of AP2-G, the master transcriptional regulator of sexual conversion2. These parasites produce sexual ring stage progeny that differentiate within ten to twelve days and across five morphologically distinct stages into either female or male stage V gametocytes, the only forms able to infect mosquitoes. While stage I-IV gametocytes sequester away from circulation, primarily in the bone marrow and spleen parenchyma, stage V gametocytes are released back into the bloodstream where they circulate as quiescent cells for up to several weeks3. Once ingested by a mosquito, female and male gametocytes are rapidly activated to release one macrogamete and eight flagellated microgametes, respectively. After fertilization, ookinete transformation and oocyst development, thousands of sporozoites eventually colonize the salivary glands for onward transmission to another human host.

The emergence and spread of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes and parasite strains partially resistant to first-line artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) threaten the malaria elimination and eradication agenda4,5. An additional major shortcoming of current antimalarials is their poor activity against gametocytes. Some drugs are inactive against all gametocyte stages (e.g. pyrimethamine) and while others are active against immature stage I-III (e.g. choloroquine) or even stage I-IV gametocytes (e.g. artemisinin and derivatives), almost all fail to kill quiescent stage V gametocytes6–10. As a consequence, infected individuals can remain infectious to mosquitoes for weeks even after asexual parasites and immature gametocytes have been cleared by drug treatment11–13. Primaquine (PQ), the only licensed drug with potent in vivo gametocytocidal and transmission-blocking activity, can cause severe hemolysis in people with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, a human genetic disorder frequently observed in malaria-endemic regions14,15. ACTs combined with a single low-dose of PQ of 0.25 mg/kg given on the first day of ACT treatment, as recommended by the WHO as a strategy to reduce malaria transmission16, have been shown to be safe and effective in preventing mosquito infection in the field17–20 but are not yet widely implemented. Furthermore, while artemether-lumefantrine, but not other ACTs, exerts potent transmission-reducing activity even in the absence of PQ21,22, there is growing concern about the spread of partial artemisinin resistance on the African continent23,24. This concern is fueled by indications that parasites with partial resistance to artemisinin are more likely to present gametocytes25 and may have a transmission advantage under artemisinin drug pressure26.

To guide the discovery and development of urgently needed new antimalarial drugs, the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) developed target candidate profiles (TCPs) describing the desired minimal and ideal properties of molecules to be combined in next generation medicines (target product profiles, TPPs)8. In addition to the strict requirement for drugs with potent activity against the disease-causing asexual blood stage parasites and novel mode-of-action to overcome drug resistance (TCP-1), transmission-blocking activity (TCP-5) is considered an essential property of new products for malaria elimination. Effective transmission-blocking drug combinations must have potent activity against asexual parasites and all gametocyte stages and can contain dual-active compounds or gametocyte-clearing compounds combined with molecules active against asexual blood stages. Although dual-active molecules are preferred from a drug development perspective, they are likely to lose their transmission-blocking effectiveness once drug resistance emerges, a risk much less likely to occur for compounds that specifically target the non-proliferative gametocyte stages7.

Due to the highly specialized biology of gametocytes, the development of suitable gametocytocidal drug assays is not straightforward. Gametocytes typically emerge at low frequency ( < 10%) from the pool of asexual parasites and require twelve days for full maturation2. During this period, gametocytes undergo dramatic cellular and metabolic transformations, culminating in the temporary quiescence of mature stage V gametocytes, while asexual parasites continue to replicate and produce new cohorts of gametocytes every second day27. One major challenge in assay development, therefore, lies in the need to produce pure and synchronous gametocyte populations for an accurate assessment of sexual stage-specific compound activity, and in large enough numbers to facilitate the screening of chemical libraries. Another challenge is that assay readouts capable of measuring cell viability, rather than proliferation, are required. Several laboratories addressed these challenges, and a multitude of different assay formats has been developed. Current protocols for gametocyte production apply conditions of high asexual parasitemia as a stress factor to enhance sexual commitment rates (SCRs). One approach employs daily medium changes without addition of fresh RBCs, which leads to overgrowth and death of asexual parasites while emerging gametocytes continue to mature with a rather poor level of synchronicity28–30. Alternatively, parasites are exposed to conditioned medium (i.e. the supernatant of high parasitemia cultures), followed by treating the progeny with N-acetyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc) to eliminate asexual parasites, which delivers synchronous gametocytes but relies on complicated culture treatment protocols31–34. Both approaches achieve SCRs rarely exceeding 30%, require large volumes of asexual feeder cultures, and many protocols rely on gametocyte enrichment by gradient centrifugation35–38 or magnetic capture6,9,39,40. Methods applied to assess gametocyte viability are based for instance on quantifying parasite metabolic10,35,37,41–47, enzymatic48,49 or mitochondrial activity6,50,51, luciferase reporter enzyme activity9,10,40,46,52–57 or gamete formation36,38,39,58,59. Regardless of the type of assay used, hit compounds must be further tested in the Standard Membrane Feeding Assay (SMFA), where mosquitoes feed on compound-exposed gametocytes60,61, to confirm effective transmission-blocking activity7,28.

The MMV Malaria Box, a selection of 400 molecules identified as active against asexual blood stage parasites in high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns62, has been tested against gametocytes on different assay platforms. These studies highlighted that inter-assay differences in gametocyte culture and purification protocols, level of gametocyte synchronicity, stage composition at the time of compound exposure, compound exposure times and/or the methods used to quantify gametocyte viability strongly impact assay outcome. Consequently, only about half of the gametocytocidal molecules reported showed consistent activity across multiple assays6,38–40,50,53,54,59,63,64. When considering hits identified at least twice independently, about 60 MMV Malaria Box compounds show low- to sub-micromolar activity against immature gametocytes (stage I-IV). Similar to antimalarial drugs, most of these compounds are more potent against early-stage gametocytes and lose their efficacy once gametocytes transitioned into their final stage of maturation6,39,59, underscoring the importance of performing primary screens on quiescent stage V gametocytes. A small number of compounds with potent activity against mature stage V gametocytes were still identified (e.g. MMV019918, MMV665941), and these hits are also active against immature stages and block parasite transmission to mosquitoes in SMFAs6,39,59,65. Several hundred additional dual-active molecules have been identified through the screening of over 17,000 experimental antimalarial compounds represented in the TCAMS and GNF Malaria Box libraries6,42,66. The screening of compound collections consisting of approved drugs, clinical drug candidates and pharmacologically active molecules37,63, inhibitors of human kinases63 or epigenetic regulators67,68, as well as HTS campaigns testing chemical diversity libraries totaling over 400,000 molecules6,47,52,53,69,70 identified no more than a few hundred compounds with promising activity against gametocytes, highlighting an extreme sparsity of gametocyte-targeting hits among molecules that have not been prescreened against asexual blood stage parasites. Interestingly, some of these hits show higher potency against gametocytes compared to asexual parasites, suggesting these molecules may target biological pathways/processes upregulated in or even specific to gametocytes6,46,52,69. Together, these studies identified numerous promising chemical starting points for the development of transmission-blocking drug candidates. However, since many of the above screening efforts used semi-synchronous late-stage gametocytes at the time of compound exposure, it remains unclear how many of the reported hits retain potent activity against quiescent stage V gametocytes.

Future efforts in transmission-blocking drug discovery and development will profit from improved and new methodologies overcoming the limitations of currently applied assays. Robust protocols for the cost-effective and efficient production of synchronous gametocytes will be important to allow better standardization of assays for stage-specific compound activity profiling and the screening of chemical libraries against mature stage V gametocytes. Furthermore, a preclinical model for gametocytocidal and transmission-blocking drug efficacy testing in vivo is urgently required. To tackle these challenges, we advanced our recently published NF54/iGP1 parasite line that allows for the mass production of synchronous gametocytes via controlled overexpression of gametocyte development 1 (GDV1)71, an upstream activator of AP2-G expression72. We engineered NF54/iGP1-RE9Hulg8 parasites expressing a red-shifted firefly luciferase specifically in gametocytes and established a simple and reliable in vitro luminescence-based stage-specific gametocyte viability assay. The screening of four chemical libraries validated this assay as a suitable tool for stage V gametocytocidal drug discovery. Most importantly, we also utilized NF54/iGP1-RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes to develop a NODscidIL2Rγnull (NSG) mouse model for P. falciparum transmission and applied this model to evaluate the in vivo gametocytocidal and transmission-blocking activities of antimalarial drugs and clinical drugs candidates.

Results

Engineering of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 parasites

NF54/iGP1 parasites carry a double conditional GDV1-GFP-DD-glmS expression cassette integrated into the non-essential cg6 locus (PF3D7_0709200)71,73. When cultured in the presence of 2.5 mM D-(+)-glucosamine hydrochloride (GlcN) and the absence of Shield-1 ( + GlcN/−Shield-1), the glmS riboswitch element in the 3’ untranslated region mediates gdv1-gfp-dd mRNA degradation and the C-terminal FKBP destabilisation domain (DD) mediates GDV1-GFP-DD protein degradation74,75. Under these conditions, NF54/iGP1 parasites display baseline sexual conversion rates (SCRs) of approximately 8%71. When GlcN is removed and 1.35 μM Shield-1 added for 48 h to a synchronous population of ring stage parasites (−GlcN/ + Shield-1), GDV1-GFP-DD is stably expressed and up to 75% of schizonts commit to sexual development, producing sexual ring stage progeny that differentiate in a synchronous manner into mature stage V gametocytes71.

Here, we engineered NF54/iGP1 parasites expressing the ATP-dependent red-shifted Photinus pyralis firefly luciferase variant PpyRE9H (RE9H)76 under control of the endogenous gametocyte-specific ulg8 (upregulated in late gametocytes 8) promoter (PF3D7_1234700)77 (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). RE9H-mediated oxidation of the D-luciferin substrate produces light at a peak emission wavelength of 617 nm (compared to 562 nm for wild type firefly luciferase)76. Because light above 600 nm has improved tissue penetration properties, red-shifted luciferases are preferred reporters for in vivo bioluminescence imaging78,79, and RE9H has successfully been used for the sensitive detection of Trypanosoma cruzi and T. brucei in experimental mouse infections models80,81. The ulg8 upstream and downstream regions have previously been shown to regulate the specific and robust expression of GFP and luciferase reporters in both female and male gametocytes, with increased expression observed in late-stage gametocytes77. Hence, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to tag the ulg8 gene in NF54/iGP1 parasites in frame with a sequence encoding the 2 A split peptide82,83 fused to RE9H (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). After drug selection of transgenic parasites, two clonal NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 populations were obtained by limiting dilution cloning. PCRs on genomic DNA (gDNA) confirmed correct editing of the ulg8 locus and NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 clone B2 (hereafter termed NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8) was selected for further experiments (Fig. S1).

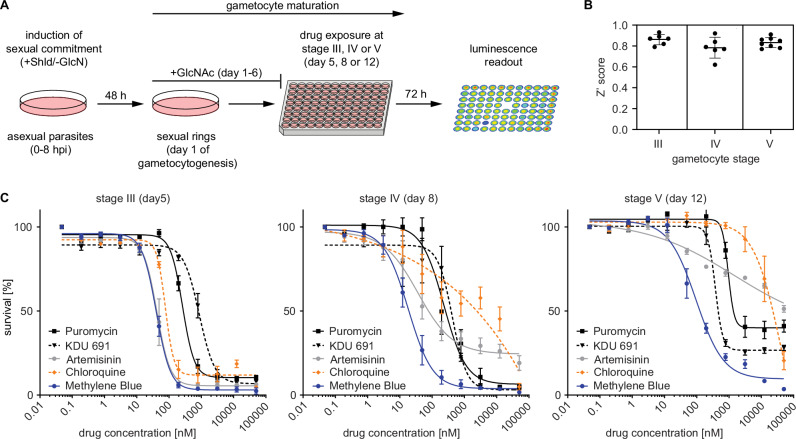

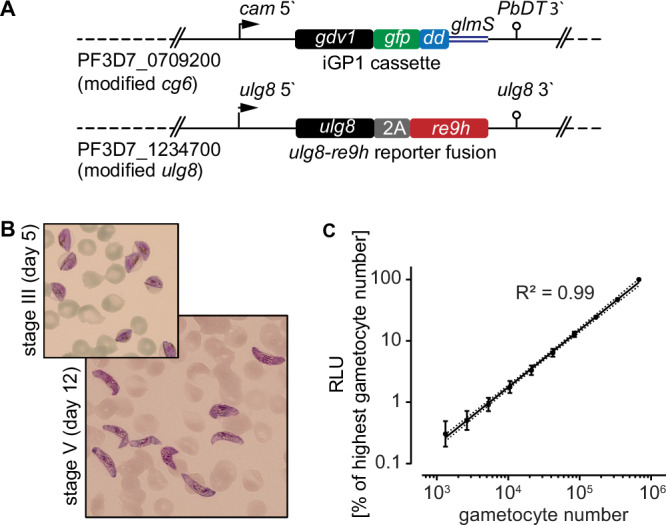

Fig. 1. NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte reporter line.

Engineering and validation of the NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 reporter line for gametocytocidal drug research. A Schematic maps of the genetically modified loci in NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 parasites. The cg6 locus carries an integrated conditional GDV1-GFP-DD over-expression cassette (iGP1) controlled by the P. falciparum calmodulin promoter (cam 5’) and the glmS ribozyme element followed by the P. berghei dihydrofolate-thymidylate synthase terminator (PbDT 3’)71. The ulg8 gene is tagged at the 3‘ end with a sequence encoding the 2 A split peptide and the RE9H luciferase. B Hemacolor-stained thin blood smears showing stage III (day 5) and mature stage V (day 12) NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes. Representative images of one of n = 4 biological replicates are shown. C Correlation between NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocyte numbers (day 12) and RE9H-catalysed bioluminescence. Values on the y-axis represent RLUs normalized to the mean signal emitted from the wells containing the highest gametocyte number, obtained from n = 4 biological replicates (mean ± s.d.). Linear regression (black line), coefficient of determination (R2) and confidence bands (dashed lines) are indicated.

NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 asexual parasites replicated with the same efficiency (multiplication rate of 7.0 ± 0.3 s.d.) compared to NF54 wild type parasites (6.9 ± 0.8 s.d.) as expected (Fig. S2). To test for synchronous gametocyte production, NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 ring stage parasites were treated with −GlcN/ + Shield-1 for 48 h to induce sexual commitment and the ring stage progeny (day 1 of gametocyte differentiation) was cultured in medium supplemented with 50 mM GlcNAc for six days to selectively eliminate asexual parasites32,33 and in normal culture medium thereafter. Based on microscopic inspection of Hemacolor-stained blood smears, NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes displayed typical morphology throughout development, gametocyte maturation was highly synchronous, and on day 12 virtually all gametocytes displayed stage V morphology (92.5% ± 4.5 s.d.) (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2). Starting with a ring stage parasitemia of 1–2 % in the induction cycle routinely delivered day 12 gametocyte cultures at 2–5% gametocytemia (3.6% ± 1.9% s.d.), making further purification or enrichment of gametocytes unnecessary. Furthermore, immunofluorescence assays using antibodies against the female-specific marker Pfg37784 revealed the expected female-biased sex ratio, and gamete activation assays demonstrated that male NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes exflagellated at rates comparable to those observed for NF54 wild type parasites (Fig. S2).

To verify and quantify expression of the RE9H luciferase in live cells, NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 day 12 gametocyte suspensions were serially diluted at constant hematocrit, incubated with D-luciferin (30 mg/ml) in black-wall 96-well assay plates under non-lysing conditions and bioluminescence was quantified using a camera-based detection system (IVIS Lumina II). Relative luminescence units (RLU) were highly correlated with absolute gametocyte numbers over a wide range ( ~ 1320-675,000 gametocytes/well) (Fig. 1C). A serial dilution experiment comparing day 12 gametocytes incubated for 72 h in the presence or absence of the gametocytocidal compound methylene blue (MB) (50 μM) revealed low background luminescence for MB-treated cells and excellent signal-to-background (S/B) and signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios across different gametocyte densities ( ~ 10,500–337,500 gametocytes/well; S/B = 3.2–57; S/N = 16–1276) (Fig. S2). Together, these results demonstrate that the RE9H reporter serves as an accurate and sensitive marker to quantify NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte viability.

Validation of the NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 line for in vitro stage-specific gametocytocidal drug activity profiling

To evaluate the suitability of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes for drug activity profiling and library screening purposes, we established a whole cell-based viability assay. Briefly, ring stage parasites are used as the starting material for the production of pure synchronous gametocyte populations according to the protocol explained above. Gametocytes are then exposed to test compounds at the desired stage of gametocyte development in 96-well cell culture plates (150 μl final volume; approx. 2% gametocytemia, 1.5% hematocrit, 450,000 gametocytes/well). After 72 h of drug exposure, 90 μl culture suspension is transferred to the wells of black-wall plates preloaded with 10 μl D-luciferin and gametocyte viability is assessed by quantifying RE9H-catalyzed luminescence (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Development of an in vitro gametocytocidal drug assay using NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes.

Assay setup and validation. A Schematic illustrating the workflow used to produce synchronous NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes and stage-specific gametocytocidal compound testing in a 96-well plate format. Gametocytes are exposed to compounds at the desired day of gametocyte development and gametocyte viability is determined 72 h later via RE9H-catalysed bioluminescence readout. Shld, Shield-1; GlcN, glucosamine, GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine. B Z‘ scores calculated from the RLUs obtained from four untreated (0.1% DMSO) and four treated (50 μM MB) samples (technical replicates) routinely included on each drug assay plate. Thick horizontal lines represent the mean Z‘ scores calculated from n = 6 (stage III and IV) or n = 8 (stage V) different assay plates, error bars indicate the s.d. and individual values are represented as black dots. C Dose-response curves for reference antimalarials (ART, CQ) and experimental compounds (KDU691, puromycin, MB) tested against synchronous NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes at three different stages of development. Values on the y-axis represent RLUs normalized to the mean signal emitted from cells exposed to the lowest drug concentration, obtained from n = 3 (stage III and IV) or n = 4 (stage V) biological replicates (mean ± s.e.m.). IC50 values are shown in Table S1.

To determine assay performance, we exposed NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes at stage III (day 5), stage IV (day 8) and mature stage V (day 12) to antimalarial drugs with known gametocytocidal activity. Dose response assays were performed in n = 3 biological replicates (each containing technical duplicates), and each plate included four replicate wells each of gametocytes treated with 50 μM MB (positive control) or the DMSO solvent only (0.1%; negative control) to calculate Z‘ scores for monitoring assay quality85. The luminescence signals measured from the positive and negative control samples on each plate indicated low variability and excellent assay robustness across the three different gametocyte stages tested (Z‘ score = 0.83 ± 0.04 s.d.) (Fig. 2B). Consistent with published data, chloroquine (CQ) was active only against stage III gametocytes, whereas artemisinin (ART) showed activity against stage III and IV gametocytes but failed to kill stage V gametocytes6. In contrast, the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI4K) inhibitor KDU69186 and the two control compounds MB and puromycin, all of which are active activity against all gametocyte stages in vitro6,9, showed the same characteristics in our assay (Fig. 2C, Table S1).

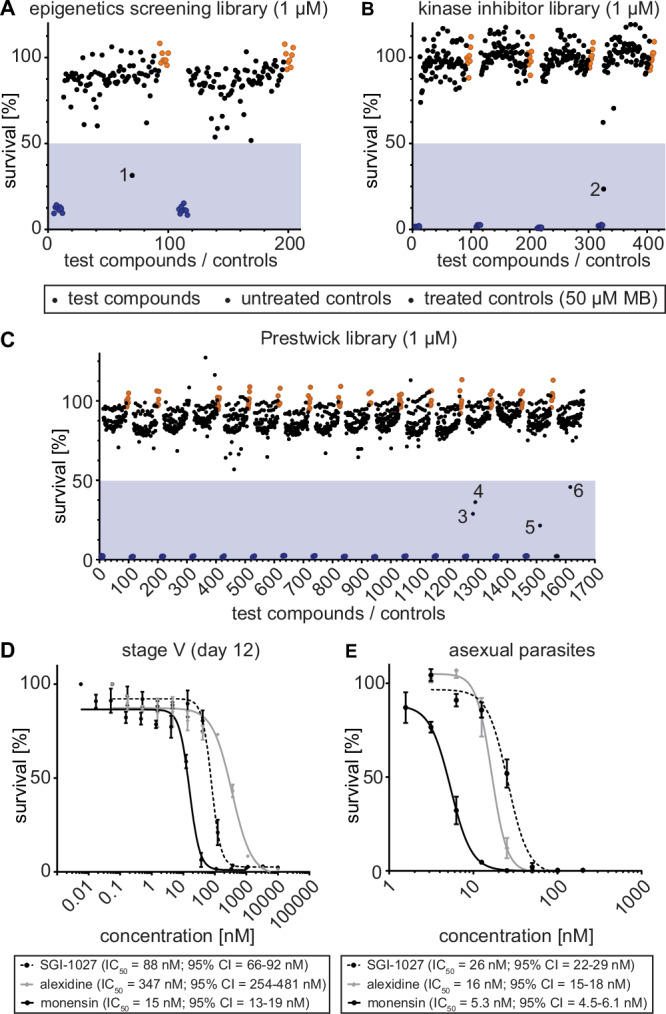

Screening of chemical libraries identifies molecules that kill NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 mature stage V gametocytes in vitro

To validate this assay as a tool for the discovery of compounds targeting quiescent stage V gametocytes, we screened 1740 molecules from four different chemical libraries. Mature NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 12) were exposed to compounds at two different concentrations (10 μM and 1 μM) for 72 h. Of the 148 molecules represented in the Epigenetics Screening Library (Cayman Chemical), 19 compounds reduced gametocyte viability by >50% at 10 μM (12.8% hit rate) (Fig. S3, Data file S1). When probed at 1 μM, only a single compound (SGI-1027), a quinoline-based inhibitor of the mammalian CpG-specific DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) DNMT1 and DNMT3A/3B87–89, showed greater than 50% inhibitory activity (68.8% inhibition) (0.7% hit rate) (Fig. 3A, Data file S1). Vanheer and colleagues recently screened a related library against P. falciparum stage IV/V gametocytes using a mitochondrial membrane potential-dependent fluorescence readout67. Among the 101 molecules shared between their and our study, the authors reported six compounds causing >50% inhibition at 1 μM and overall their results correlate well with our data (R2 = 0.60), with SGI-1027 identified as the most potent gametocytocidal molecule in both studies (Fig. S4, Data file S2). The slightly higher inhibitory effect of active molecules observed by Vanheer et al.67. compared to our study may be explained by the fact that our assay uses synchronous stage V gametocytes rather than a mixture of stage IV/V gametocytes (Fig. S4, Data file S2).

Fig. 3. Screening of chemical libraries against NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes.

Results from the primary screening of small- to medium-sized compound libraries. A–C Effect of compounds of the Epigenetics Screening Library (Cayman Chemical) (A), human kinase inhibitors (SelleckChem, Enzo Life Sciences) (B) or compounds of the Prestwick Chemical Library (C) on NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V (day 12) gametocyte viability (1 µM concentration). Each assay plate included eight treated (50 µM MB; blue dots) and untreated (0.1% DMSO; orange dots) samples each as positive and negative controls, respectively. Values on the y-axis represent RLUs normalized to the mean signal emitted from the negative controls, obtained from n = 1 experiment for each library. Compounds with >50% inhibitory activity (blue shaded areas) are highlighted by numbers (1, SGI-1027; 2, SU4312; 3, monensin; 4, alexidine dihydrocholride; 5, indoprofen; 6, equilin). D Dose-response curves of SGI-1027, monensin and alexidine dihydrochloride tested against NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 12). Values on the y-axis represent RLUs normalized to the mean signal emitted from cells exposed to the lowest drug concentration, obtained from n = 3 biological replicates (mean ± s.e.m.) E Dose-response curves of SGI-1027, monensin and alexidine dihydrochloride tested against NF54 wild type asexual blood stage parasite multiplication. Values on the y-axis represent [3H]-hypoxanthine incorporation normalized to the mean signal emitted from eight untreated control samples per plate, obtained from n = 3 biological replicates (mean ± s.e.m.). IC50 values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are indicated below the graphs.

We then screened a small focused in-house library consisting of 37 compounds targeting human DNMTs, histone methyltransferases (HKMTs), and deacetylases, several of which have demonstrated fast-acting activity against asexual blood stage parasites90–95. Nine of these molecules showed >50% inhibition at 10 μM (21.6% hit rate), but only 68”/LHER1320, a DNMT3A inhibitor harboring a quinazoline moiety designed to mimic the methyl donor S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)90, retained >50% inhibitory activity when probed at 1 μM (56.9% inhibition) (2.7% hit rate) (Fig. S3, Data file S3). Interestingly, BIX-01294, another quinazoline-based specific inhibitor of the human G9a HKMT96 with potent activity against asexual blood stages and male gamete formation94,95, also showed moderate activity against stage V gametocytes (30% inhibition at 1 μM) (Data files S1 and S3). Similarly active were three quinazoline-quinoline bisubstrate derivatives of 68”/LHER1320 that carry a quinoline moiety mimicking the targeted cytosine linked to the same (68/LH1326) or a differently substituted quinazoline moiety (20/LH1281, A/LH1514)90 and were previously shown to kill asexual blood stage parasites with low to mid nanomolar potency93 (Data file S3).

Next, we screened a library of 275 inhibitors of human kinases (SelleckChem, Enzo Life Sciences). At the 10 μM concentration, eight inhibitors reduced stage V gametocyte viability by >50% (2.9% hit rate) (Fig. S3, Data file S4), and only a single molecule (SU4312), a selective inhibitor of VEGFR2 and PDGFR receptor tyrosine kinases97, showed >50% inhibitory effect at 1 μM (76.5% inhibition) (0.4% hit rate) (Fig. 3B, Data file S4).

Lastly, we screened the Prestwick Chemical Library containing 1,280 compounds, most of which are FDA- and EMA-approved drugs. The Prestwick Chemical Library has previously been screened against P. falciparum asexual blood stage parasites and contains several dozen compounds, including known antimalarials, with >50% inhibitory activity at 5 μM98. Here, when tested on mature stage V gametocytes, 40 compounds showed >50% inhibition at 10 μM (3.1% hit rate), and four compounds displayed >50% inhibition at the 1 μM concentration (0.3% hit rate) (Fig. 3C, Fig. S3, Data file S5). These hits are the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug indoprofen99 (78.5% inhibition), the estrogenic steroid equilin100,101 (54.2% inhibition), the polyether ionophore monensin102 (71.2% inhibition), and alexidine dihydrochloride (63.2% inhibition), a broad-spectrum antimicrobial103.

We confirmed the activity of the six most potent compounds identified above through dose-response assays on mature stage V gametocytes and asexual blood stage parasites. All compounds showed a dose-dependent killing effect on stage V gametocytes with IC50 values in the nanomolar range (Fig. 3D, Fig. S5). Three of these compounds (SGI-1027, monensin, alexidine dihydrochloride) demonstrated potent dual-active properties as they also inhibited asexual parasite proliferation with low nanomolar activity (Fig. 3E). In contrast, SU4312, equilin and indoprofen were either inactive or showed marginal activity against asexual parasites (IC50 > 10 μM), which suggested these compounds may have specific activity against gametocytes (Fig. S5). However, an in vitro RE9H luciferase inhibition assay using NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte lysates revealed that SU4312 and indoprofen, and to some extent also equilin, directly inhibit RE9H enzyme activity and were therefore considered false-positive hits (Fig. S5).

Development of a preclinical humanized NODscidIL2Rγnull mouse model to evaluate stage V gametocytocidal drug activities in vivo

After the successful application of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes for in vitro drug activity profiling and screening, we anticipated these parasites may also be suitable to develop a preclinical NODscidIL2Rγnull (NSG) mouse model for evaluation of gametocytocidal and transmission-blocking drug efficacy in vivo. To this end, NSG mice were engrafted with human RBCs (hRBCs) as previously described104. In parallel, synchronous NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes were cultured in vitro according to the protocol explained above and purified by magnetic enrichment using MACS columns. To determine a suitable inoculum for a NSG infection model, hRBC-engrafted mice were infected with either 1 × 107, 1 × 108, 2 × 108 or 1 × 109 purified day 9 (stage IV/V) or day 11 (stage V) gametocytes via intravenous (i.v.) injection. The circulation of gametocytes in peripheral blood was then monitored daily via microscopic inspection of Hemacolor-stained thin smears prepared from tail blood. Gametocytes circulated in the peripheral blood of all engrafted mice and the initial gametocytemia was positively associated with inoculum size and gradually decreased over time, with circulating gametocytes detectable for more than ten days post-infection in mice infected with >108 gametocytes (limit of quantification (LoQ): one gametocyte per 10,000 RBCs) (Fig. S6). With an inoculum of 2 × 108 gametocytes, the average peripheral gametocytemia reached 0.5% ( ± 0.04 s.d.) 30 min after infection (Fig. S6). Based on these encouraging results, we tested whether the high gametocyte production rates achieved with the NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 line in vitro would allow us to infect mice with RBC pellets taken directly from NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte cultures without prior gametocyte enrichment. Indeed, the injection of packed RBCs containing 2 × 108 gametocytes even increased the peripheral gametocytemia to 0.9% ( ± 0.07 s.d.) compared to the 0.5% achieved with MACS-purified gametocytes, and circulating gametocytes were similarly detectable beyond 10 days post-infection (Fig. S6). Lastly, prior to performing whole animal in vivo bioluminescence imaging of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte-infected NSG mice, we confirmed that i.v. Injection of D-luciferin (150 mg/kg) had no effect on gametocyte densities and circulation times (Fig. S6). Together, these results demonstrate the successful establishment of a reliable humanized NSG mouse model for the exclusive infection with P. falciparum stage V gametocytes (NSG-PfGAM).

To determine whether the NSG-PfGAM model can be used to assess stage V gametocytocidal drug activity in vivo, we first tested the antimalarial reference drugs CQ and PQ. Mice were infected with packed RBCs containing 2 × 108 NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 11) as outlined above. One day after infection, mice were treated by oral gavage with either a single or four daily doses of CQ (1 × 50 mg/kg, 4 × 50 mg/kg), or with a single dose of PQ (1 × 50 mg/kg), or were left untreated. In mice treated with CQ, NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes were detectable in circulation until day 14 by both microscopy and in vivo bioluminescence imaging after D-luciferin injection. The decline in gametocytemia and bioluminescence signal over time was identical compared to untreated control mice, regardless of the received CQ dose or treatment regimen (Fig. 4A-C). On the contrary, gametocyte densities in PQ-treated mice began to decline on day two after treatment and reached the LoQ by day 7 when monitored by microscopy (Fig. 4A). The in vivo bioluminescence-based signals for gametocyte viability declined more rapidly already on day 1 after treatment and fell well below the LoQ by day 7 (Fig. 4B-C). These results clearly demonstrate that the NSG-PfGAM model can readily discriminate between drugs that are inactive or active against stage V gametocytes in vivo via the combined bioluminescence and microscopy readouts of gametocyte viability and clearance, respectively, and validate this system as a preclinical model suitable to evaluate antimalarial drugs and drug candidates with regard to their in vivo gametocytocidal properties.

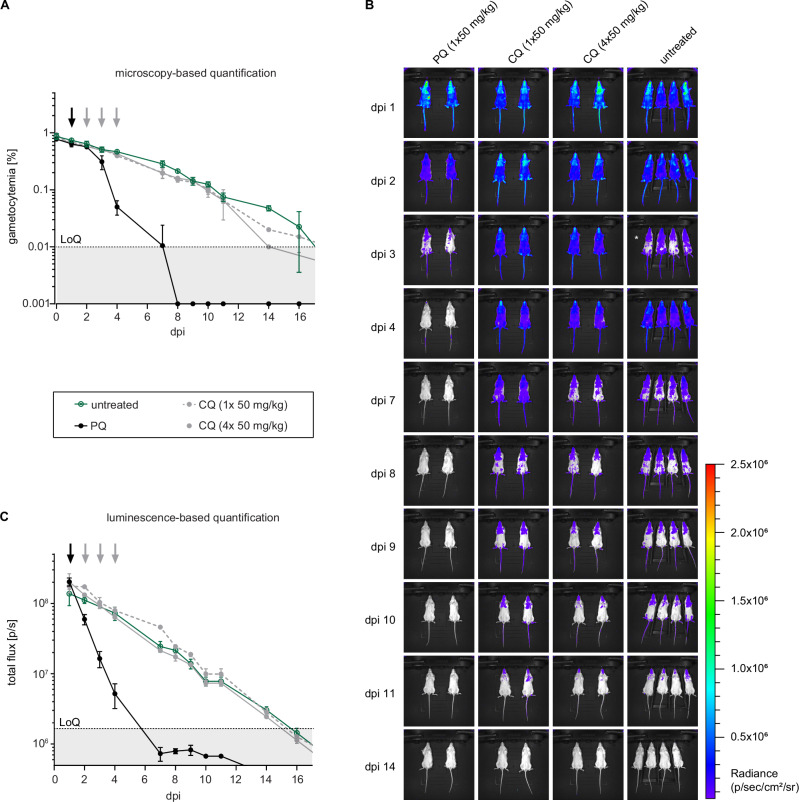

Fig. 4. Circulation and clearance of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes in the NSG-PfGAM in vivo model.

Mice were infected with 2 × 108 NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 11) and treated one day after infection with 1 × 50 mg/kg PQ, 1 × 50 mg/kg CQ or four daily doses of 1 × 50 mg/kg CQ (days 1–4) or were left untreated. A Peripheral gametocytemia in treated and untreated NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected mice as determined by microscopic inspection of Hemacolor-stained thin blood smears prepared daily from tail blood for 16 days. Arrows indicate the day(s) of treatment. Values on the y-axis represent gametocytemia (mean ± s.d.) obtained from n = 2 mice per drug/dose combination and n = 4 untreated control mice. B Representative ventral images of treated and untreated NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected mice. Pseudocolour heat-maps indicate RE9H-catalysed bioluminescence intensity from low (blue) to high (red). Circulation of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes was monitored daily for 16 days following infection (only a selection of images is shown). For technical reasons, the uninfected control mice on day 3 post-infection had to be imaged 30 min after D-luciferin injection (instead of 1 min after D-luciferin injection for all other mice), which resulted in reduced signals (white asterisk). C Quantification of in vivo bioluminescence emitted from treated and untreated NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected mice. Arrows indicate the day(s) of treatment. Values on the y-axis represent total photon flux (mean ± s.d.) obtained from n = 2 mice per drug/dose combination and n = 4 untreated control mice. dpi, days post infection; LoQ, limit of quantification (area below the LoQ is shaded gray); p/s, photons/second.

Using the NSG-PfGAM model to assess stage V gametocyte killing and clearance in vivo after treatment with clinical drug candidates

We then used the NSG-PfGAM model to assess five clinical antimalarial drug candidates that entered phase I (SJ733), phase II (KAE609/cipargamin, MMV390048, OZ439/artefenomel), and phase III trials (KAF156/ganaplacide) for their activity against stage V gametocytes in vivo. The dihydroisoquinolone SJ733 and the spiroindolone KAE609/cipargamin are chemically unrelated molecules that both target the Na+-ATPase PfATP4105,106. The imidazolopiperazine KAF156/ganaplacide interferes with protein secretion, but its specific target(s) have not yet conclusively been identified107,108. MMV390048 is a PI4K inhibitor109 and OZ439/artefenomel is a synthetic trioxolane with a peroxide pharmacophore related to that of artemisinin110. All five drug candidates have been described as potential transmission-blocking molecules based on in vitro assays, where these compounds showed gametocytocidal activity against mixed late stage gametocytes as assessed by microscopy (KAE609/cipargamin, KAF156/ganaplacide)107,111 or cellular viability readout (MMV390048)109, demonstrated inhibitory activity in female (OZ439/artefenomel)49, male (MMV390048)109 or dual female/male gamete formation assays (KAE609/cipargamin, KAF156/ganaplacide)112 or inhibited mosquito infection in SMFAs (KAE609/cipargamin, KAF156/ganaplacide, MMV390048, OZ439/artefenomel)49,107,109,113,114. Furthermore, all five clinical drug candidates demonstrated in vivo transmission-blocking activity in the P. berghei malaria mouse model105,107,109,115. To our knowledge, however, these molecules have never specifically been tested for their in vitro activity against mature stage V gametocytes, except for OZ439/artefenomel that was shown to be inactive6.

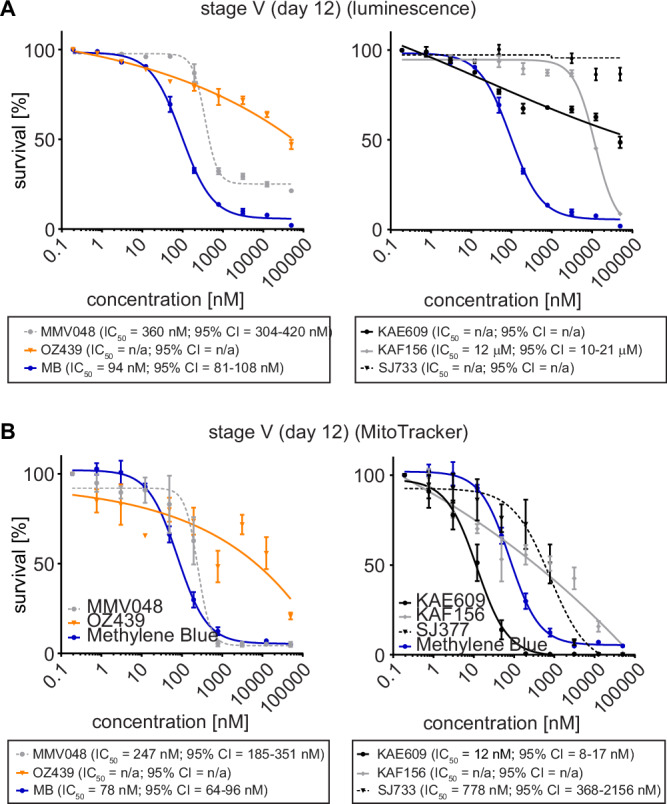

We therefore first performed in vitro dose-response assays to assess the potencies of all five clinical drug candidates against NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 mature stage V gametocytes (day 12) using the RE9H-based luminescence readout. These experiments confirmed the lack of activity of OZ439/artefenomel and revealed potent activity for MMV390048 (IC50 = 360 nM) and the positive control MB (IC50 = 94 nM) (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, stage V gametocyte viability was only poorly compromized by KAE609/cipargamin and KAF156/ganaplacide (IC50 = 12 μM) and unaffected by SJ733 (Fig. 5A), even though all compounds potently inhibited asexual parasite proliferation (Fig. S7). However, inspection of Hemacolor-stained thin blood smears revealed strong morphological defects (rounded, swollen gametocytes) upon KAE609/cipargamin exposure as previously observed111,116, even in the low nanomolar range (Fig. S7). The same phenotype was observed for SJ733-treated gametocytes but only at substantially higher concentrations. KAF156/ganaplacide-treated gametocytes also began to show aberrant morphology at concentrations >200 nM that was clearly distinct from the pyknotic cells observed after exposure to MB (Fig. S7). Hence, KAE609/cipargamin-, SJ733- and KAF156/ganaplacide-treated stage V gametocytes seem to maintain membrane integrity and metabolic activity despite severely compromised cellular morphology. To address this issue further, we employed high content imaging of MitoTracker- and Hoechst-stained cells as an alternative readout to quantify viable stage V gametocytes based on mitochondrial activity and cellular shape. These results uncovered highly potent activity against stage V gametocytes for KAE609/cipargamin (IC50 = 12 nM). SJ733 was also active albeit at ~70-fold reduced potency (IC50 = 778 nM) compared to KAE609/cipargamin (Fig. 5B). The results for KAF156/ganaplacide were less clear but activity was still apparent even though an IC50 value could not be determined. For MMV390048 (IC50 = 247 nM), OZ439/artefenomel (inactive) and MB (IC50 = 78 nM), the MitoTracker-/cellular shape-based dose response assays delivered highly congruent results compared to the RE9H luciferase-based viability readout (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Activities of clinical drug candidates against NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes in vitro.

Comparison of RE9H bioluminescence- and MitoTracker/gametocyte shape-based viability readouts for NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes treated with clinical drug candidates. A Dose-response curves of MMV390048 and OZ439/artefenomel (left graph) and KAE609/cipargamin, KAF156/ganaplacide and SJ733 (right graph) tested against NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 12) using RE9H-catalysed bioluminescence as viability readout. MB was used as a positive control (identical data shown in both graphs). Values on the y-axis represent RLUs normalized to the mean signal emitted from cells exposed to the lowest drug concentration, obtained from n = 3 biological replicates (mean ± s.e.m.). B Dose-response curves of MMV390048 and OZ439/artefenomel (left graph) and KAE609/cipargamin, KAF156/ganaplacide and SJ733 (right graph) tested against NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 12) using MitoTracker signal/gametocyte shape as viability readout. MB has been used as a positive control (identical data shown in both graphs). Values on the y-axis represent normalized mean numbers of viable gametocytes obtained from n = 3 biological replicates (n = 2 biological replicates for OZ439/artefenomel and MMV390048) (mean ± s.e.m.). IC50 values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown below the graphs.

With an improved understanding of their activity against stage V gametocytes in vitro, we tested these clinical drug candidates in vivo in the NSG-PfGAM model. One day after infection with 2 × 108 NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 11), mice were treated with either 1 × 40 mg/kg KAE609/cipargamin, 1 × 50 mg/kg SJ733, 1 × 20 mg/kg KAF156/ganaplacide, 1 × 50 mg/kg MMV390048, 1 × 50 mg/kg OZ439/artefenomel, or 1 × 50 mg/kg PQ as a positive control. KAF156/ganaplacide cleared gametocytes by day 4 after dosing with kinetics comparable to those observed after treatment with PQ (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, for both KAF156/ganaplacide and PQ, the bioluminescence readout indicated a faster onset of gametocyte killing compared to clearance, suggesting delayed elimination of dead gametocytes from circulation (Fig. 6B–D). MMV390048 displayed rapid stage V gametocyte killing activity similar to PQ but without any marked delay in gametocyte clearance (Fig. 6A–D). After treatment with OZ439/artefenomel, we observed a lag phase of four days before a slight reduction of gametocytemia and cellular viability could be detected, but circulating gametocytes were still detectable until day 10 and 14 by microscopy and bioluminescence readout, respectively (Fig. 6A–C). Treatment with KAE609/cipargamin resulted in highly rapid clearance of gametocytes to below the LoQ within two days of drug exposure (Fig. 6A–D). Interestingly, the bioluminescence imaging readout highlighted signal accumulation in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen, implying retention and clearance of KAE609/cipargamin-exposed gametocytes in the spleen (Fig. S8). In contrast to KAE609/cipargamin, SJ733 failed to eliminate stage V gametocytes from circulation and gametocytes were detectable by both readouts until day 14 after infection similar to the untreated controls (Fig. 6A–C).

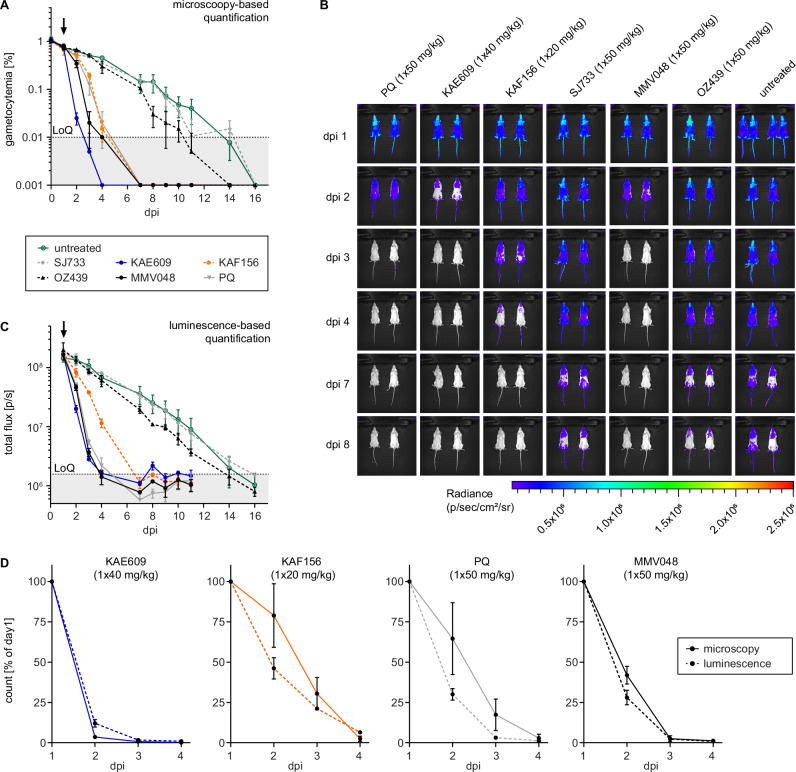

Fig. 6. In vivo therapeutic efficacy of clinical drug candidates against NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes in the NSG-PfGAM model.

Mice were infected with 2 × 108 NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 11) and were treated one day after infection with 1 × 40 mg/kg KAE609/cipargamin, 1 × 20 mg/kg KAF156/ganaplacide, 1 × 50 mg/kg SJ733, 1 × 50 mg/kg MMV390048, 1 × 50 mg/kg OZ439/artefenomel and 1 × 50 mg/kg PQ (positive control) or were left untreated. A Peripheral gametocytemia in treated and untreated NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected mice as determined by microscopic inspection of Hemacolor-stained thin blood smears prepared daily from tail blood for 16 days. The arrow indicates the day of treatment. Values on the y-axis represent gametocytemia obtained from n = 2 mice per drug/dose combination and n = 4 untreated control mice (mean ± s.d.). B Representative ventral images of treated and untreated NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected mice. Pseudocolour heat-maps indicate RE9H-catalysed bioluminescence intensity from low (blue) to high (red). Circulation of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes was monitored for 16 days following infection (only a selection of images up to day 8 is shown). C Quantification of in vivo bioluminescence signal emitted from treated and untreated NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected mice. The arrow indicates the day of treatment. Values on the y-axis represent total photon flux obtained from n = 2 mice per drug/dose combination and n = 4 untreated control mice (mean ± s.d.). D Direct comparison of peripheral gametocytemia (solid lines) and in vivo bioluminescence signal (dashed lines) in NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected mice treated with active molecules. Values on the y-axis represent % gametocytemia (microscopy readout) or total photon flux (luminescence readout) normalized to the corresponding values determined on day 1 after infection, obtained from n = 2 mice per drug/dose combination (mean ± s.d.) (same experiment as shown in panels A and C). dpi, days post infection; LoQ, limit of quantification (area below the LoQ is shaded gray); p/s, photons/second.

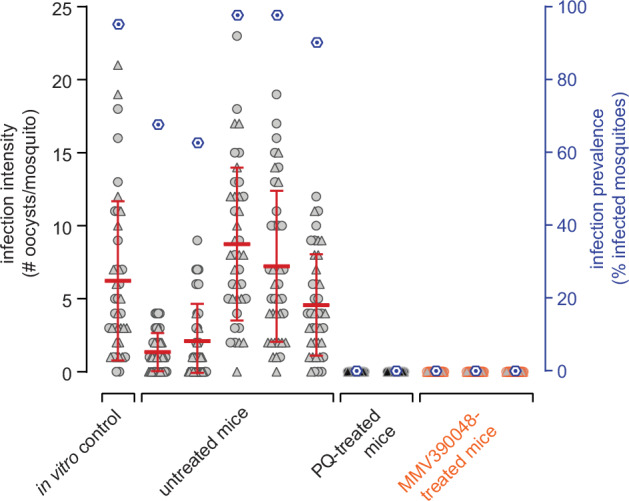

Using NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte-infected NODscidIL2Rγnull mice to assess the in vivo transmission-blocking potential of antimalarial drugs and drug candidates

Finally, to test if the NSG-PfGAM model allows assessing in vivo transmission-blocking efficacy of antimalarial drugs and drug candidates, we performed Membrane Feeding Assays (MFAs) using female Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes60,61. hRBC-engrafted mice were again infected with packed RBCs containing 2 × 108 NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 11) and treated on the subsequent day with PQ (1 × 50 mg/kg), MMV390048 (1 × 50 mg/kg) or were left untreated. Two days after treatment, whole blood was collected and mosquitoes were allowed to feed on duplicate blood samples of two PQ-treated mice (positive control for transmission blockade), three MMV390048-treated mice, and five untreated control mice (positive control for mosquito infection). Furthermore, a SMFA performed with the same NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte population used to infect the mice, but maintained in in vitro culture until the day of feeding, served as a positive control for mosquito infection. As shown in Fig. 7, mosquitoes feeding on the blood from untreated mice and the matched in vitro control sample showed a high infection prevalence and comparable infection intensities. In stark contrast, treating mice with a single dose of either PQ or MMV390048 completely blocked gametocyte transmission, with none of the mosquitoes carrying any oocysts (Fig. 7). These results validate the well-established transmission-blocking properties of PQ in this experimental mouse model and reveal that the PI4K inhibitor MMV390048 exhibits similar effectiveness in preventing gametocyte transmission to mosquitoes in vivo.

Fig. 7. In vivo transmission-blocking efficacy of clinical drug candidates as assessed using the NSG-PfGAM mouse model.

Female Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were allowed to feed on the blood taken from NODscidIL2Rγnull mice infected with 2 × 108 NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 11) and were left untreated (positive control for mosquito infection; five mice) or were treated one day after infection with either 1 × 50 mg/kg PQ (positive control for transmission blockade; two mice) or 1 × 50 mg/kg MMV390048 (three mice). Blood samples were prepared for MFAs three days after infection/two days after treatment (day 14 of gametocyte maturation). A day 14 aliquot of the same in vitro gametocyte culture used to infect the mice was prepared for SMFAs and served as a further positive control for mosquito infection. Values on the left y-axis (infection intensity) show the number of oocysts detected in each of the 20 mosquitoes dissected per n = 2 technical replicate feeds, with open circles and triangles representing the results obtained from the two separate feeds, respectively. The thick red horizontal lines represent the mean numbers of oocysts per mosquito, error bars indicate the s.d.. Values on the right y-axis (infection prevalence) represent the mean percentage of infected mosquitoes obtained from the combined replicate feeds for each condition (dark blue hexagons).

Discussion

Here, we engineered the NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 reporter line to establish a transmission-blocking drug discovery and development platform that overcomes most challenges associated with conducting in vitro gametocytocidal drug assays and, importantly, provides an urgently needed preclinical model for assessing transmission-blocking drug activity in vivo. NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 parasites have two major advantages compared to existing gametocyte reporter lines. First, they are equipped with an inducible GDV1 over-expression cassette allowing for the routine mass production of synchronous gametocytes71. Second, expression of the red-shifted firefly luciferase PpyRE9H not only facilitates quantifying gametocyte viability in vitro but also in vivo via whole animal bioluminescence imaging of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8-infected NSG mice. With these two exquisite properties combined, a simple and highly efficient cell culture protocol starting with a 10 ml ring stage culture routinely delivers 2 × 108 highly synchronous stage V gametocytes that can be directly used without further purification for both in vitro and in vivo drug testing.

For the in vitro assay, gametocytes at the desired stage of maturation are exposed to test compounds in a 96-well format for a defined period of time. At the assay endpoint, the D-luciferin substrate is added just before measuring gametocyte viability using a bioluminescence-based readout. This straightforward assay, requiring only a single well transfer step, shows excellent S/N ratios and high robustness (Z‘ score > 0.8), making it well-suited for higher throughput formats. While pure synchronous gametocyte populations are obtained as early as day 5 of maturation (stage III), we placed strong emphasis on using mature stage V gametocytes for drug screening as they represent the most difficult-to-kill stages. Of the 1,740 molecules screened against mature stage V gametocytes (day 12), only four compounds (monensin, alexidine dihydrochloride, SGI-1027, 68”/LHER1320) showed >50% activity at 1 µM, which underscores the general insensitivity of these quiescent stages to drug treatment. Importantly, dose-response assays performed for three of these compounds revealed potent dual activity, suggesting they target essential molecular processes shared between asexual parasites and mature stage V gametocytes.

Monensin, as well as other monovalent carboxylic polyether ionophores such as salinomycin and nigericin, are highly active against blood stage parasites in vitro and in vivo117–120, possess potent gametocytocidal and transmission-blocking activity63,117 and are interestingly also active against the dormant P. vivax hypnozoite stages121. Members of this class of ionophores are also active against other apicomplexan parasites and are widely used in the poultry industry to prevent coccidiosis, an intestinal disease caused by Eimeria spp.122,123. Ionophores are lipid-soluble compounds that bind cations and exert their toxicity by disrupting ionic membrane gradients, which in turn affects numerous biological processes123. In Toxoplasma gondii, monensin disrupts mitochondrial morphology and membrane potential and elicits oxidative stress, cell cycle arrest, and autophagy-induced cell death124–126. While the mechanism of action of monensin against P. falciparum has not been investigated, the profound morphological defects and cell death observed for gametocytes exposed to the dual-active ionophore maduramicin127 are linked to rapid cellular Na+ influx128, which interestingly also occurs with the Na+-transporter PfATP4 inhibitors KAE609/cipargamin, SJ733, and PA21A050105,128–130. The bis-biguanide alexidine dihydrochloride is a cationic antimicrobial that disrupts bacterial cell wall and membrane integrity and is used as an antiseptic in mouth washes and contact lens solutions103. Alexidine dihydrochloride is also active against various pathogenic fungi131, and its antifungal properties may be linked to inhibition of phospholipases132. Further, alexidine dihydrochloride is a specific inhibitor of the human mitochondrial tyrosine phosphatase PTPMT1133 and was shown to induce apoptosis in cancerous cells in vitro and in vivo134–136. Interestingly, alexidine dihydrochloride is listed in the MMV Pandemic Response Box (MMV396785) and was found to be active against Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites137 and, consistent with our findings, P. falciparum asexual parasites and late-stage gametocytes46. Moreover, alexidine dihydrochloride inhibits male gametogenesis and mosquito infection in both P. falciparum and P. berghei46,138. SGI-1027, a non-nucleoside quinoline-based inhibitor of mammalian DNMT1 and DNMT3A/B87,88, has been proposed to occupy both the cytidine and SAM substrate pockets139,140 but was then shown to act via DNA-competitive inhibition and destabilization of the DNMT-DNA-SAM complex89. The quinazoline-based compound 68”/LHER1320 is expected to compete with SAM co-factor binding, whereas the moderately gametocytocidal quinazoline-quinoline bisubstrate analogs are predicted to occupy both substrate pockets of DNMTs90,93. However, P. falciparum encodes only a single DNMT enzyme, PfDNMT2, that primarily acts as a tRNAASP methyltransferase141–143, like its orthologs in other eukaryotes144, and is not essential for asexual parasite growth, gametocytogenesis and male gamete formation142,143. Hence, while SGI-1027 and/or 68”/LHER1320 may still inhibit PfDNMT2 function, their lethal anti-parasitic effects are probably due to inhibition of other unknown vital targets. While HKMTs are obvious candidates to consider, P. falciparum eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit I has recently been identified as a direct target of compound 70145, a closely related analog of the bisubstrate inhibitor 68/LH1326 (parent of compound 68”/LHER1320)90. In summary, our screening efforts identified and confirmed potent dual-active compounds that may serve as starting points for future structure-activity relationship studies and chemical biology approaches aimed at identifying vulnerable targets in quiescent gametocytes.

Humanized NODscidIL2Rγnull (NSG) mice engrafted with hRBCs and infected with P. falciparum serve as invaluable in vivo models for the preclinical development of drugs against asexual blood stage parasites. They are widely employed to test drug candidates for therapeutic efficacy in a physiological environment similar to that of humans, able to capture the effects of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic properties, determine pharmacodynamic parameters and predict dosing regimens for use in humans146. However, these models have never been optimized for assessing drug activity against gametocytes and have, to our knowledge, been used only once to test the gold standard transmission-blocking drug PQ147, a prodrug that requires metabolic processing to unfold its activity in vivo148. Duffier et al. showed that in NSG mice infected with NF54 wild type parasites, four daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) PQ injections (2 mg/kg) cleared the gametocytes that naturally emerged during blood infection within three to six days after treatment initiation147. While this study provided important proof of concept that P. falciparum-infected NSG mice can be used to test transmission-blocking drugs, this model requires extensive immunomodulation by repeated i.p. injections, results in mixed infections composed of replicating asexual parasites and varying levels of gametocytes of all stages, and does not support quantifying gametocyte viability in vivo147. Here, we addressed these limitations by establishing a NSG model tailored for the systematic evaluation of P. falciparum transmission-blocking drug efficacies in vivo. This NSG-PfGAM model uses a comparatively simple standardized experimental setup, also with regard to animal preparation and handling, thus avoiding any stressful immunomodulation procedures. hRBC-engrafted NSG mice are infected i.v. with 2x108 pure NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 stage V gametocytes (day 11), resulting in a starting gametocytemia of around 1%, and are treated on the subsequent day with drugs/drug candidates administered by oral gavage. Gametocyte viability and clearance can then be monitored and correlated over a period of two weeks by in vivo bioluminescence imaging after D-luciferin injection and microscopic inspection, respectively, and transmission-blocking activity can be assessed by mosquito feeding experiments.

PQ was highly active in the NSG-PfGAM model and cleared stage V gametocytes within four to seven days after treatment, consistent with the findings reported by Duffier and colleagues147. Notably, we observed that gametocyte viability declined more rapidly than gametocyte density, demonstrating that PQ-mediated sterilization precedes gametocyte clearance. Indeed, two days of in vivo exposure to PQ rendered gametocytes non-infectious and blocked transmission to mosquitoes. This pharmacodynamic response mimics the gametocyte-sterilizing effect of PQ in human clinical trials, where single-dose PQ treatments consistently abolish gametocyte infectiousness to mosquitoes by day 2–3 post treatment but a substantial decline in gametocyte densities is only evident by day 717,19,149–152. KAF156/ganaplacide elicited a response similar to that seen with PQ; efficient gametocyte clearance was achieved by day 4 after treatment and the reduction in gametocyte density was preceded by a decline in cellular viability, suggesting that KAF156/ganaplacide also has gametocyte-sterilizing effects. This assumption is consistent with our in vitro data showing that KAF156/ganaplacide-exposed stage V gametocytes retain cellular integrity (despite distorted morphology) even at micromolar concentrations. MMV390048 caused a rapid and coincident decline in both gametocytemia and viability to below the LoQ by day 3 after dosing, and fully blocked transmission to mosquitoes as assessed two days after treatment. Interestingly, MMV390048 also showed promising transmission-blocking potential in recent mosquito infection experiments conducted with stage V gametocytes isolated from naturally infected carriers and exposed to the drug for 24 h ex vivo (IC50 ~ 200 nM)114. In a recent controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) study, however, single dose treatment of P. falciparum-infected volunteers with MMV390048 (80 mg) did not prevent stage V gametocyte formation and mosquito infection153, indicating higher dosing would be required to efficiently block transmission. OZ439/artefenomel has poor activity against mature gametocytes in cellular viability assays as shown here and elsewhere6,10,49, but displayed inhibitory effects in vitro on female gamete formation and transmission to mosquitoes with reported IC50 values of 100–200 nM49,113. In the NSG-PfGAM model, OZ439/artefenomel had no measurable impact on circulating gametocytes during the first three days after treatment, but a moderate reduction in both gametocyte viability and density compared to the untreated controls was observed from day 7 onwards, which may indicate a delayed impact on female and/or male gametocyte fitness. Overall, these results are consistent with those obtained in recent CHMI studies, where single dose treatment with OZ439/artefenomel alone (500 mg) or in combination with DSM265 (200 mg) failed to prevent stage V gametocyte formation and did not reduce their densities five days post treatment154,155. While these combined data suggest OZ439/artefenomel lacks in vivo transmission-blocking activity, mosquito feeding assays on treated NSG-PfGAM mice will be required to ultimately confirm this assumption.

Treatment with KAE609/cipargamin resulted in a ~ 30-fold and ~140-fold reduction in peripheral gametocytemia on the first and second day after dosing, respectively, the fastest in vivo gametocyte clearance rates observed in our study. Notably, this rapid elimination of gametocytes from circulation was linked to accumulation of gametocytes in the spleen. Previous in vitro studies have shown that KAE609/cipargamin inhibits the Na+-ATPase PfATP4 and thereby induces swelling and rigidification of asexual parasite-infected RBCs156,157 and gametocytes111,116 (also observed in this study), and that these physical changes prevent their passage through spleen-mimetic filter systems116,156. Spleen-dependent elimination of parasitized RBCs has indeed been proposed as the most likely mechanism explaining the rapid clearance of ring stage-infected RBCs in humans after KAE609/cipargamin administration156,158–160. Carucci et al. similarly hypothesized that KAE609/cipargamin-exposed stage V gametocytes may also be eliminated in the spleen116. The results obtained with our NSG-PfGAM model demonstrate for the first time that KAE609/cipargamin rapidly clears stage V gametocytes from circulation and provide direct in vivo evidence that splenic retention is indeed primarily responsible for this favorable outcome. In clinical studies, however, a single dose of KAE609/cipargamin (10–30 mg) administered to infected study participants was insufficient to prevent the development of gametocytes159,161, again showing that higher doses may be necessary to achieve effective gametocyte transmission-blocking activity. In stark contrast to KAE609/cipargamin, the second PfATP4 inhibitor we tested, SJ733, had no effect on reducing gametocyte densities throughout the 14 day follow-up period. This profoundly different pharmacodynamic response is likely due to the lower potency SJ733 has against stage V gametocytes in vitro as shown here and in previous SMFA experiments113,114, combined with inferior pharmacokinetic properties compared to KAE609/cipargamin105,106. However, because the bioluminescence-based readout obtained for SJ733-exposed gametocytes only informs about cellular but not functional integrity, we cannot entirely exclude that the gametocytes circulating in treated mice may be attenuated in their capacity to infect mosquitoes.

To date, efficacy assessments of transmission-blocking drug activity in vivo rely on phase 2 clinical trials in naturally infected gametocyte-positive patients participating in mosquito feeding assays before and after treatment; these trials are costly and can only be conducted in a handful of settings with access to specialized laboratories. In recent years, CHMI study protocols have undergone important modifications to enable transmission-blocking drug activity testing in earlier phases of clinical development. Infecting healthy volunteers using the induced blood stage malaria (IBSM) approach162 followed by piperaquine treatment, which kills asexual parasites but allows gametocytes to develop163,164, can achieve gametocyte densities high enough to support mosquito infection154,165 and has recently been used to demonstrate the transmission-reducing effect of single low-dose tafenoquine (50 mg) seven days post-treatment166. While the IBSM transmission model represents a major advance in the field, its implementation is again highly complex and expensive and the gametocyte densities obtained are still low and variable such that gametocyte enrichment from venous blood is required to achieve reliable mosquito infection rates154,165,166. The preclinical NSG-PfGAM transmission model developed here demonstrated excellent performance and allowed us for the first time to assess and directly compare the in vivo stage V gametocytocidal activities and transmission-blocking potential of several clinical drug candidates. The high starting gametocytemia, long gametocyte circulation times in untreated mice and the combined bioluminescence and microscopy readouts have proven particularly useful for determining and discriminating between the kinetics of gametocyte killing/sterilization and clearance, which highlighted marked differences in the pharmacodynamic responses effected by the different molecules tested. We were thus able to show that after treatment with a single high dose, two of the most advanced clinical drug candidates eliminated stage V gametocytes in vivo with similar (KAF156/ganaplacide) or superior (KAE609/cipargamin) activity compared to the gold standard drug PQ, underscoring their transmission-blocking potential. Furthermore, the NSG-PfGAM model recapitulated the gametocyte-sterilizing effect observed after PQ treatment in humans, indicated that KAF156/ganaplacide may have a similar effect, and revealed that KAE609/cipargamin leads to rapid elimination of stage V gametocytes from circulation, most likely via efficient clearance in the spleen. As previously suggested, the prediction of effective transmission-blocking human doses for drug candidates such as MMV390048, KAE609/cipargamin and KAF156/ganaplacide relies on understanding in vivo drug concentrations over time and their effects on the infectivity of circulating gametocytes113. Our NSG-PfGAM transmission model will allow determining in vivo minimum gametocyte-sterilizing concentrations, similar to the minimum parasiticidal concentrations that have been established for compounds active against asexual blood-stage parasites167, with the proviso that allometric scaling can misestimate pharmacokinetic profiles in humans168. We therefore believe that the NSG-PfGAM model, combined with mosquito feeding experiments, offers an invaluable and innovative tool for systematically evaluating transmission-blocking drug candidates and antibodies in vivo under controlled experimental conditions and at an affordable cost. In addition to early validation of candidate molecules during the preclinical phase of development, the NSG-PfGAM model is ideally suited for determining pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships and efficacious transmission-blocking doses for clinical candidates, antimalarial drugs and drug combinations as crucial parameters needed to optimally design subsequent clinical studies for efficacy testing in humans.

Methods

Plasmodium falciparum in vitro culture

NF54 wild type, NF54/iGP1 and NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 parasites were cultured using human erythrocytes (Blutspende SRK Zürich, Switzerland; blood groups AB+ or B + ) at a hematocrit of 5% in RPMI 1640 medium (10.44 g/l) (Fisher Scientific; #11544506) supplemented with 25 mM HEPES (Roth; #HN77.5), 370 μM hypoxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich; #H9377), 24 mM sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich; #S5761), 100 μg/ml neomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; #N6386) and 10% heat-inactivated AB+ human serum (Blutspende SRK Basel, Switzerland). For NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 asexual cultures, 2.5 mM D-(+)-glucosamine hydrochloride (GlcN) (Sigma-Aldrich; G1514) was routinely added to the growth medium to maintain the glmS ribozyme active. Intra-erythrocytic growth synchronization was performed using repeated sorbitol treatments169. Parasite cultures were maintained in an atmosphere of 3% O2, 4% CO2, and 93% N2 in air-tight chambers at 37 °C.

Cloning of transfection constructs

The pHF_gC-ulg8 CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid was generated by T4 DNA ligase-dependent insertion of annealed complementary oligonucleotides (ulg8_sg1F, ulg8_sg1R) encoding the single guide RNA (sgRNA) target sequence sgt_ulg8 along with compatible single-stranded overhangs into BsaI-digested pHF_gC72. The sgt_ulg8 target sequence (ggtcctttatacgacacagg) is positioned 243–223 bp upstream of the ulg8 STOP codon and has been designed using CHOPCHOP170. The pD_ulg8_re9h donor plasmid was generated by Gibson assembly171 of four PCR fragments. The first PCR fragment represented a 523 bp synthetic sequence (GenScript) corresponding to the 3’ end of the ulg8 gene, of which the first 275 bp constitute the 5’ homology box (HB) and the last 248 bp have been recodonized. PCR fragment 1 was amplified from plasmid pUC57-re-ulg8 (GenScript) using primers 5’ box_F and 5’ box_R. The second PCR fragment represented a sequence encoding an in-frame fusion of the 2A split peptide and the PpyRE9H luciferase. To generate this template, we inserted a sequence encoding the 2A split peptide directly upstream of the re9h coding sequence in plasmid pTRIX2-RE9h80. This was achieved by Gibson assembly of a PCR fragment encoding the 2A sequence, amplified from pSLI-BSD172 using primers 2a_F and 2a_R, and the BamHI-digested pTRIX2-RE9h plasmid, resulting in plasmid pTRIX2-2A-RE9h. PCR fragment 2 (2A-RE9H) was then amplified from pTRIX2-2A-RE9h using primers 2a-re9h_F and 2a-re9h_R. PCR fragment 3 represented the 830 bp 3’ HB spanning the last 226 bp of the ulg8 coding sequence and 604 bp of the downstream sequence (amplified from 3D7 gDNA using primers 3’ box_F and 3’ box_R). PCR fragment 4 represented the pD donor plasmid backbone amplified from pUC19 using primers PCRA_F and PCRA_R72. All oligonucleotide sequences used for cloning are provided in Table S2.

Transfection and selection of transgenic NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 parasites

NF54/iGP1 parasites were transfected and selected according to the protocol published by Filarsky and colleagues72. RBCs collected from a 5 ml culture of synchronous ring stage parasites (10% parasitemia) were co-transfected with 50 µg each of the pHF_gC-ulg8 CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid and the pD_ulg8_re9h donor plasmid using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Xcell Electroporation System (single exponential pulse, 310 V, 250 µF). Twenty hours after transfection, 5 nM WR99210 was added to the culture medium for six days to select for gene-edited parasites, and henceforth parasites were maintained in normal culture medium until a stably propagating parasite population was obtained. The transgenic NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 line was cloned out by limiting dilution cloning using an established plaque assay173 and successful editing of the ulg8 locus was confirmed by PCR on gDNA isolated from two clonal lines (A2 and B2). All oligonucleotide sequences provided in Table S2).

Parasite multiplication rates

Synchronous NF54 wild type and NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 ring stage cultures were seeded at approx. 1% parasitemia and incubated in culture medium supplemented with 2.5 mM GlcN until completion of one invasion cycle (48 h). Parasitemia at baseline and in the progeny was determined by microscopy (100x immersion oil objective) counting uninfected and at least 200 infected RBCs in thin blood smears stained with Hemacolor Rapid (Merck; #1.11956.2500, #1.11957.2500). Multiplication rates were calculated as the ratio of parasitemia measured in the progeny compared to baseline.

Induction of sexual commitment and gametocyte culture

Sexual commitment of NF54 wild type parasites was induced by exposing synchronous late ring stage cultures (20–28 h post invasion) to minimal fatty acid medium [culture medium containing 0.39% fatty acid-free BSA (Sigma-Aldrich; #A6003) instead of AlbuMAX II, supplemented with 30 μM oleic acid and 30 μM palmitic acid (Sigma-Aldrich; #O1008 and #P0500)]174. Sexual commitment of NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 parasites was triggered as described in Boltryk et al.71. Briefly, synchronous ring stage cultures (2–3% parasitemia) were grown for 48 h in medium lacking GlcN and containing 1.25 µM Shield-1 to induce GDV1-GFP-DD expression in trophozoites and schizonts. Eight hours after invasion into new RBCs (8–16 hpi asexual/sexual ring stage progeny; day 1 of gametocytogenesis), the induction medium was replaced with standard culture medium containing 50 mM N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (Sigma-Aldrich; #A3286) for six consecutive days to selectively kill asexual parasites32,33. From day 7 onwards, gametocytes were maintained in standard culture medium. The culture medium was exchanged daily during the first seven days of gametocyte development and subsequently every second day. Gametocytemia and gametocyte morphology was assessed by visual inspection of Hemacolor-stained thin blood smears using a 100x immersion oil objective.

Exflagellation assays

Exflagellation assays were conducted on NF54 wild type and NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 mature day 13 gametocyte cultures according to a previously published protocol28. In brief, culture suspensions were pelleted at 600 g for 3 min and the RBC pellet was resuspended in activation medium [serum-containing culture medium supplemented with 100 µM xanthurenic acid (Lucerna; #Y-W014666)]. After a 15 min incubation at room temperature, samples were applied to a Neubauer chamber, and exflagellation centers and RBC densities were quantified by bright-field microscopy (Leica DM1000 LED, 40x objective). Gametocytemia was determined by visual inspection of Hemacolor-stained thin blood smears prepared from the same samples. Exflagellation rates were determined as the proportion of gametocytes forming exflagellation centers.

Immunofluorescence assays

IFAs to visualize Pfg377 expression in NF54 wild type and NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 late stage gametocytes (day 10) were performed on thin blood smears fixed with ice-cold methanol/acetone (60:40). The slides were incubated for one hour in blocking solution (3% BSA in PBS) followed by one hour incubation with rabbit α-Pfg377antibodies84 (1:1000). After three washes with blocking solution, Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated α-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes; #A11011) secondary antibodies were applied (1:250) and the slides were incubated for 45 min in the dark. Slides were washed three times in PBS and mounted using Vectashield antifade containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories; #H-1200). A minimum of 200 gametocytes were counted to determine the sex ratio. Microscopy was performed using a Leica Thunder 3D Assay fluorescence microscope (63x objective) equipped with a Leica K5 cMOS camera and Leica Application Suite X software (LAS X version 3.7.5.24914). Identical settings were used for both image acquisition and processing with Fiji (ImageJ2 version 1.54 f).

Chemical compounds

Primaquine (PQ) (Sigma-Aldrich; #160393), chloroquine (CQ) (Sigma-Aldrich; #C6628), artemisinin (ART) (Sigma-Aldrich; #361593), methylene blue (MB) (Sigma-Aldrich; #M9140), puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich; #P8833), SU4312 (Sigma-Aldrich; #S8567, alexidine dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich; #A8986), monensin (Sigma-Aldrich; #475895), indoprofen (Sigma-Aldrich; #I3132), equilin (Sigma-Aldrich; #E8126), the clinical drug candidates KDU691, KAE609/cipargamin, KAF156/ganaplacide and the experimental antimalarials SJ733, MMV390048, OZ439/artefenomel (all provided by MMV) were prepared as 10 mM stock solutions in 100% DMSO (chloroquine was prepared in ddH20). The Epigenetics Screening Library (148 compounds) has been purchased from Cayman Chemical (#11076) (Data file S1). The 37 compounds targeting DNMTs, HKMT, and histone deacetylases were synthesized as described90–93,175,176 (Data file S3). The kinase inhibitor library of 275 compounds (SelleckChem and Enzo Life Sciences) (Data file S4) and the Prestwick Chemical Library of 1280 off-patent small molecules (Data file S5) were provided by the Biomolecular Screening Facility (BSF) (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland). All library compounds were provided as 10 mM stock solutions in 100% DMSO.

Establishment and validation of a whole cell-based RE9H luciferase assay for in vitro gametocytocidal drug screening

To determine the range within which the absolute number of viable NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocytes is linearly correlated with luminescence signals, stage V gametocyte cultures (day 12) were resuspended in culture medium containing 0.5% Albumax II (Gibco; #11021-037) instead of 10% human serum (assay medium) at ~2.5% gametocytemia and 3% hematocrit. 300 μl gametocyte suspension was transferred into the well of a 96-well cell culture plate (Corning; #353072) and serially diluted in assay medium at constant hematocrit in biological quadruplicates, each containing eight technical replicates (150 μl suspension/well; 10-step dilution series; 2-fold serial dilutions; ~1,125,000-2,200 gametocytes/well). To determine signal-to-noise (S/N) and signal-to-background (S/B) ratios, serially diluted stage V gametocyte suspensions (day 12) were prepared in assay medium containing MB (final concentration 50 μM) or the DMSO vehicle alone (final concentration 0.1%) in technical quadruplicates (150 μl suspension/well; 6-step dilution series; 2-fold serial dilutions; ~562,500-17,600 gametocytes/well), followed by a 72-hour incubation period under standard growth conditions. Wells containing uninfected RBCs at 3% hematocrit were used as a further control. To quantify RE9H-catalyzed bioluminescence, 90 µl of each suspension was added to individual wells of a black-wall 96-well plate (Greiner CELLSTAR; #7.655.086) preloaded with 10 µl D-luciferin in PBS (30 mg/ml) (PerkinElmer; #122799). After a 5 min incubation step, luminescence signals were quantified using an IVIS Lumina II in vivo imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, PerkinElmer) at exposure times varying between 30 sec and 3 min. Data were analyzed and exported to a numerical format (counts) using Living Image (v4.7.2, Perkin Elmer). Luminescence counts of technical replicates were averaged and the data imported into GraphPad Prism (version 8.2.1). S/N and S/B ratios were calculated using the following formulas:

| 1 |

| 2 |

Dose response assays on gametocytes using the RE9H luciferase-based readout

Dose response assays were performed in biological triplicates, each in technical duplicate. Synchronous NF54/iGP1_RE9Hulg8 gametocyte cultures (day 5, day 8 or day 12) were resuspended in assay medium at ~2% gametocytemia and 3% hematocrit. 75 µl gametocyte suspension ( ~ 450,000 gametocytes/well) was pipetted into each well of a 96-well cell culture plate, pre-loaded with 75 µl compound serially diluted in assay medium (11-step/12-step dilution series; 3-fold/4-fold serial dilutions). To monitor assay robustness using Z‘ scores, each plate included four wells containing MB (final concentration 50 µM) and the DMSO vehicle alone (final concentration 0.1%) as positive and negative controls, respectively. Gametocytes were exposed to the compounds for 72 h under standard culture conditions, followed by the transfer of 90 µl culture suspension to black-wall 96-well plates (Greiner CELLSTAR; #7.655.086) preloaded with 10 µl D-luciferin (30 mg/ml) (PerkinElmer; #122799). Luminescence signals were quantified as explained above. Luminescence counts of technical duplicates were averaged and the data imported into GraphPad Prism (version 8.2.1) and normalized to the plateau of sub-lethal compound concentrations using the “first mean in each data set” function. IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear, four parameter (variable slope) curve fitting. Z‘ scores were calculated using the luminescence signals emitted from the MB-treated and untreated (DMSO vehicle) control samples. Z‘ factor formula:

| 3 |