ABSTRACT

Background:

Obesity among medical students is a significant public health issue with various contributing factors, including dietary habits, physical activity, and genetic predisposition. This study aims to assess obesity prevalence and its associated factors among North Indian medical undergraduates.

Aim:

To assess the prevalence of obesity and its relationship with various factors among medical undergraduates in North India.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted from September 15, 2024, to October 15, 2024, at a tertiary care institute. All students from the MBBS Batch 2023 participated via convenient sampling. Data were collected through a Google form covering sociodemographic, dietary and physical habits, and mental health. Analysis was performed using SPSS Trial version 26.

Results:

Out of 208 students, 6% were underweight, 66.8% were normal weight, 17.8% were overweight, and 5.8% were obese. Significant associations were found between BMI and gender (P = .003), breakfast eating (P = .012), and family history of obesity (P = .006).

Conclusion:

Obesity prevalence among medical students in North India is influenced by a complex interplay of sociodemographic, lifestyle, and genetic factors. Targeted programs are needed to address these specific predictors and support health management in medical students.

Keywords: Body mass index, lifestyle, medical students, north India, obesity, risk factors

Introduction

Obesity is one of the lifestyle-related conditions in India, with a 9.4% incidence of overweight and 2.4% for obesity. Obesity is rapidly increasing worldwide. The ideal definition, based on percentage of body fat, is impractical for epidemiological purposes. The body mass index (weight/height2) is commonly employed in adult populations, and a cutoff value of 30 kg/m2 is universally recognized as an indicator of adult obesity. Obesity is one of the most significant difficulties that Indians face because we are genetically predisposed to gain weight.[1]

Obesity has numerous detrimental consequences on health. Individuals with obesity face a heightened risk of acquiring cardiovascular disease. Obesity adversely affects the digestive system and increases the likelihood of cancer. Obesity also has detrimental psychological effects and, in addition, leads to several issues in individuals’ lives.[2]

The genesis of obesity results from multiple elements, including nutrition, genetic predisposition, physical activity, physiological circumstances, and behavioral characteristics. Healthcare professionals have a crucial role in advocating for healthy lifestyles among the general population. However, research involving medical students and healthcare professionals across several nations substantiates this assertion.[3]

The global prevalence is rapidly increasing, with forecasts indicating that by 2030, around 57.8% of the adult population would be classified as overweight or obese. Obesity presents a significant challenge during university years, particularly as the transition from high school sometimes entails alterations in physical activity and dietary habits, often resulting in weight increase.[4]

In India, obesity has reached epidemic proportions, with 5% of the population obese, and the prevalence is fast increasing, particularly among adults. Punjab is one of India’s prosperous states, with residents traditionally indulging in energy-rich foods. This factor, coupled with increased urbanization, stress, sedentary lifestyle, and availability and affordability of junk/energy-dense food, likely puts this population at a higher risk of becoming obese.[5]

Considering this context, we conducted a study to evaluate the prevalence of obesity among medical undergraduates and its associated factors in a tertiary care teaching institution in North India.

Aim and Objective

To assess the prevalence of obesity in medical undergraduates

To assess the relationship of different factors and their association with obesity.

Material and Methods

Study type – a cross-sectional observational study.

Study duration – October − November 2024.

Study setting – a tertiary care institute of North India.

Sample size – Convenient sampling was used and all students of MBBS Batch 2023 were included in the study after obtaining informed consent.

Data analysis – data were collected using an online Google form. It consist of sociodemographic profile, dietary behavior, personal and family history, physical behavior, and mental health. Data collected were converted into Microsoft Excel 2021 and were cleaned. Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied wherever applicable. For Logistic Regression analysis. SPSS Trial version 26 was used.

BMI Calculation – Anthropometric measurement of height and weight was done as per WHO standards. Standardized and calibrated instruments were used for this purpose. Height and weight measurements were utilized to calculate the BMI, with BMI values falling below 18.5 kg/m2 indicating underweight, values between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 indicating normal weight, values between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 indicating overweight, and values equal to or exceeding 30 kg/m2 indicating obesity.

Each day students were called to check weight and height measurements using the BMI scale in the Department of Community Medicine until the completion of sample size.

Ethical clearance – the study was given approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee vide letter no Trg9 (310) 2024/32872.

Results

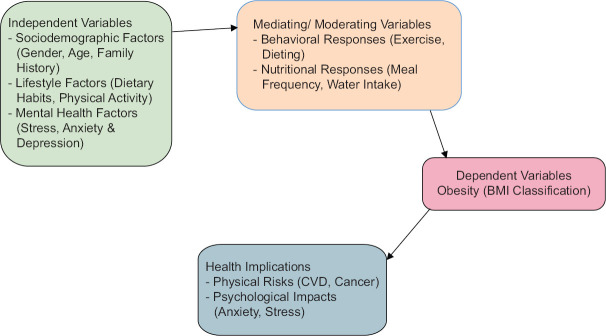

The conceptual framework in Figure 1 illustrates how sociodemographic, lifestyle, and mental health factors contribute to obesity in medical students, with mediating influences like exercise and dietary habits. This obesity status (BMI classification) impacts physical and psychological health, showing the complex relationships driving obesity risks among North Indian students.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework Diagram. The conceptual framework for study on obesity among North Indian medical students

Participant characteristics and BMI distribution

The study involved 208 students. The distribution of participants among different BMI groups was as follows: There were 20 (6%) underweight, 139 (66.8%) of normal weight, 37 (17.8%) overweight, and 12 (5.8%) obese.

Sociodemographic influences on BMI

The sociodemographic comparisons between BMI categories are shown in Table 1. A large proportion of participants (76.0%) were 18-20 years old, and in this group, the proportion of overweight and obese persons was somewhat higher. BMI was significantly associated with gender (P = .003) with males more likely to be overweight or obese and females more likely to be normal weight. We found no differences in location or wealth between the groups of BMI.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic comparison

| Under Weight (n=20) | Normal (n=139) | Overweight (n=37) | Obesity (n=12) | P | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 18−20 | 17 (85.0) | 81 (58.3) | 23 (62.2) | 8 (66.7) | 0.418 | NS |

| 20−22 | 3 (15.0) | 58 (41.7) | 14 (37.8) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 8 (40.0) | 41 (29.5) | 22 (59.5) | 7 (58.3) | 0.003 | HS |

| Female | 12 (60.0) | 98 (70.5) | 15 (40.5) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| Locality | ||||||

| Urban | 11 (55.0) | 88 (63.3) | 23 (62.2) | 8 (66.7) | 0.915 | NS |

| Rural | 7 (35.0) | 36 (25.9) | 8 (21.6) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| Peri-urban | 2 (10.0) | 15 (10.8) | 6 (16.2) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Per Capita Income | ||||||

| ₹9098 and above | 17 (85.0) | 87 (62.6) | 22 (59.5) | 7 (58.3) | 0.327 | NS |

| ₹4549−9097 | 1 (5.0) | 29 (20.8) | 8 (21.6) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| ₹2729−4548 | 1 (5.0) | 15 (10.8) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| ₹1364−2728 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.6) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| <₹1364 | 1 (5.0) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Dietary behavior and BMI

Table 2 shows that breakfast eating had a significant relationship with BMI (P = .012). Those who were overweight were more likely to skip breakfast than those who were average or underweight. There was a significant association between skipping meals and obesity (P = .026), with obese students less likely to skip meals. The consumption of fast food and water intake were not significantly different between groups (P > .05), but obese students drank more water on average.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of students BMI with dietary behavior of the students

| Under Weight | Normal | Overweight | Obesity | P | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you eat breakfast? | ||||||

| Never | 1 (5.0) | 5 (3.6) | 8 (21.6) | 1 (8.3) | 0.012 | S |

| Weekly | 1 (5.0) | 17 (12.2) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Daily | 18 (90.0) | 117 (84.2) | 27 (73.0) | 9 (75.0) | ||

| How often do you consume fast food? | ||||||

| Never | 1 (5.0) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.204 | NS |

| Weekly | 17 (85.0) | 126 (90.7) | 28 (75.7) | 10 (83.3) | ||

| Daily | 2 (10.0) | 11 (7.9) | 6 (16.2) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| How often do you drink soft drinks? | ||||||

| Never | 6 (30.0) | 43 (30.9) | 12 (32.4) | 3 (25.0) | 0.900 | NS |

| Weekly | 14 (70.0) | 85 (61.2) | 23 (62.2) | 8 (66.7) | ||

| Daily | 0 (0.0) | 11 (7.9) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| How many glasses of water do you drink per day? (1 glass=250 ml) | ||||||

| 0 – 4 Glasses | 6 (30.0) | 37 (26.6) | 6 (16.2) | 2 (16.7) | 0.404 | NS |

| 5 – 8 Glasses | 10 (50.0) | 78 (56.1) | 20 (54.1) | 9 (75.0) | ||

| 9 – 12 Glasses | 4 (20.0) | 20 (14.4) | 11 (29.7) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| 13 – 16 Glasses | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| How often do you skip meals? | ||||||

| Never | 9 (45.0) | 60 (43.2) | 12 (32.4) | 9 (75.0) | 0.026 | S |

| Weekly | 8 (40.0) | 69 (49.6) | 17 (45.9) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Daily | 3 (15.0) | 10 (7.2) | 8 (21.6) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Do you snack between meals? | ||||||

| Daily | 2 (10.0) | 19 (13.6) | 9 (24.3) | 3 (25.0) | 0.349 | NS9 |

| 3−4 times per Week | 7 (35.0) | 61 (43.9) | 9 (24.3) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| Rarely | 11 (55.0) | 55 (39.6) | 19 (51.4) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| Never | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Do you stress eat? | ||||||

| Daily | 2 (10.0) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (8.3) | 0.293 | NS |

| 3 – 4 times per Week | 2 (10.0) | 26 (18.6) | 9 (24.3) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| Rarely | 9 (45.0) | 70 (50.4) | 21 (56.8) | 7 (58.4) | ||

| Never | 7 (35.0) | 40 (28.8) | 5 (13.5) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| How often do you order food online/go out to eat? | ||||||

| Daily | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.481 | NS |

| 3–4 times per Week | 9 (45.0) | 43 (30.9) | 13 (35.1) | 7 (58.3) | ||

| Rarely | 10 (50.0) | 89 (64.0) | 22 (59.5) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| Never | 1 (5.0) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Total number of meals per day on an average? | ||||||

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.827 | NS |

| 2 | 5 (25.0) | 29 (20.9) | 11 (29.7) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| 3 | 14 (70.0) | 100 (71.9) | 24 (64.9) | 10 (83.4) | ||

| >3 | 1 (5.0) | 9 (6.5) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (8.3) |

Family health history and BMI

The relationship of BMI and personal/family history is summarized in Table 3. A strong relation was found between a family history of obesity and current BMI (P = .006), and obese students are more likely to have a family history of obesity. As such, historical obesity was highly associated with current obesity (P < .001).

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of students BMI with personal and family history of the students

| Under Weight | Normal | Overweight | Obesity | P | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have a family history of obesity? | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (10.0) | 27 (19.4) | 11 (29.7) | 7 (58.3) | 0.006 | HS |

| No | 18 (90.0) | 112 (80.6) | 26 (70.3) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| Does anyone in your family have a chronic illness (First-degree relative)? | ||||||

| Yes | 8 (40.0) | 48 (34.5) | 15 (40.5) | 4 (33.3) | 0.888 | NS |

| No | 12 (60.0) | 91 (65.5) | 22 (59.5) | 8 (66.7) | ||

| Do you have a chronic illness (e.g., diabetes, hypertension)? | ||||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.0) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.282 | NS |

| No | 20 (100.0) | 127 (91.4) | 30 (81.1) | 11 (91.7) | ||

| Don’t Know | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.6) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Have you been obese in the past? | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (5.0) | 21 (15.1) | 22 (59.5) | 8 (66.7) | <0.001 | HS |

| No | 19 (95.0) | 118 (84.9) | 15 (40.5) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| Do you have stretch marks? | ||||||

| Yes | 6 (30.0) | 60 (43.2) | 27 (73.0) | 9 (75.0) | 0.001 | HS |

| No | 14 (70.0) | 79 (56.8) | 10 (27.0) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| Do you get at least 6−8 h of sleep per day? | ||||||

| Yes | 15 (75.0) | 118 (84.9) | 28 (75.7) | 10 (83.3) | 0.478 | NS |

| No | 5 (25.0) | 21 (15.1) | 9 (24.3) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Do you consume alcohol? | ||||||

| Never | 20 (100.0) | 128 (92.1) | 31 (83.8) | 12 (100.0) | 0.109 | NS |

| Occasionally | 0 (0.0) | 11 (7.9) | 6 (16.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Do you smoke? | ||||||

| Regularly | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.247 | NS |

| Occasionally | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No | 19 (95.0) | 135 (97.1) | 37 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | ||

| Ex-Smoker | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Do you care about your body shape? | ||||||

| Yes | 18 (90.0) | 129 (92.8) | 32 (86.5) | 9 (75.0) | 0.183 | NS |

| No | 2 (10.0) | 10 (7.2) | 5 (13.5) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| What kind of entertainment do you choose in your spare time? | ||||||

| Sleep/Surf the Internet | 11 (55.0) | 89 (64.0) | 26 (70.3) | 6 (50.0) | 0.705 | NS |

| Reading | 2 (10.0) | 11 (7.9) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| Sports | 2 (10.0) | 14 (10.1) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Hanging out | 5 (25.0) | 25 (18.0) | 7 (18.9) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Do you have any ongoing medication? | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (5.0) | 18 (12.9) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (8.3) | 0.741 | NS |

| No | 19 (95.0) | 121 (87.1) | 33 (89.2) | 11 (91.7) |

Physical activity and mental health

There was no significant relationship between BMI and physical activity levels (P = .355; Table 4). Students who were overweight or obese were more likely to turn to gym and dieting to lose weight compared with normal-weight students (P < .001). No differences in electronic device use were found based on BMI.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of students BMI with physical behaviour of the students

| Under Weight | Normal | Overweight | Obesity | P | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you exercise for 30 min or more? | ||||||

| Never | 8 (40.0) | 41 (29.5) | 10 (27.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0.355 | NS |

| Weekly | 6 (30.0) | 69 (49.6) | 14 (37.8) | 7 (58.3) | ||

| Daily | 6 (30.0) | 29 (20.9) | 13 (35.1) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| Are you able to walk for 30 minutes without getting tired? | ||||||

| Yes | 15 (75.0) | 115 (82.7) | 31 (83.8) | 10 (83.3) | 0.847 | NS |

| No | 5 (25.0) | 24 (17.3) | 6 (16.2) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Have you ever tried to lose weight through gym and dieting? | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (10.0) | 48 (34.5) | 30 (81.1) | 9 (75.0) | <0.001 | HS |

| No | 18 (90.0) | 91 (65.5) | 7 (18.9) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| How many hours do you spend sitting or using electronic devices daily? | ||||||

| <4 h | 6 (30.0) | 41 (29.5) | 10 (27.0) | 3 (25.0) | 0.626 | NS |

| 4–8 h | 9 (45.0) | 73 (52.5) | 23 (62.2) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| >8 h | 5 (25.0) | 25 (18.0) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (33.3) |

As shown in Table 5, BMI had no significant relationship with reported stress levels (P = .984), with about 65% of students reporting stress, independent of BMI. The link between sadness or anxiety and BMI was close to significance (P = .093), but underweight students were more likely to report having these problems than obese people.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis of students BMI with mental health and stress of the students

| Under Weight | Normal | Overweight | Obesity | P | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you feel stressed often? | ||||||

| Yes | 13 (65.0) | 91 (65.5) | 23 (62.2) | 8 (66.7) | 0.984 | NS |

| No | 7 (35.0) | 48 (34.5) | 14 (37.8) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| Do you have difficulty managing stress? | ||||||

| Yes | 12 (60.0) | 67 (48.2) | 18 (48.6) | 7 (58.3) | 0.720 | NS |

| No | 8 (40.0) | 72 (51.8) | 19 (51.4) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| Have you experienced depression or anxiety in the last year? | ||||||

| Yes | 13 (65.0) | 56 (40.3) | 18 (48.6) | 3 (25.0) | 0.093 | NS |

| No | 7 (35.0) | 83 (59.7) | 19 (51.4) | 9 (75.0) |

Logistic regression analysis

The adjusted odds ratio analysis is shown in Table 6. BMI was highly predicted by gender, with males being more likely to be overweight or obese (OR = 34.999, P = .028). Current obesity also predicted past obesity (OR = 12.061, P = .032), whereas depression/anxiety had an inverse relationship with obesity (OR = 0.009, P = .017).

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis: Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for factors associated with obesity

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) | Lower | Upper | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 34.999 | 1.477 | 829.542 | 0.028 |

| Age | 0.667 | 0.299 | 1.489 | 0.323 |

| Family History of obesity | 4.605 | 0.516 | 41.088 | 0.171 |

| Family has a chronic illness | 0.401 | 0.039 | 4.175 | 0.445 |

| Obesity in the past | 12.061 | 1.236 | 117.668 | 0.032 |

| Ongoing medication | 15.223 | 0.329 | 705.280 | 0.164 |

| Walk for 30 minutes without getting tired | 0.755 | 0.047 | 12.258 | 0.844 |

| Tried to lose weight through gym and dieting | 9.875 | 0.596 | 163.552 | 0.110 |

| Water intake | 0.798 | 0.520 | 1.225 | 0.303 |

| Difficulty managing stress | 6.213 | 0.355 | 108.812 | 0.211 |

| Experienced depression or anxiety in the last year | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.433 | 0.017 |

| Feel stressed often | 0.423 | 0.033 | 5.351 | 0.506 |

| Feel fatigued easily or have difficulty engaging in physical activities | 6.666 | 0.452 | 98.340 | 0.167 |

Discussion

The increasing prevalence of obesity among medical students poses significant public health concerns. In our study, 23.6% of participants were overweight or obese, which aligns with findings from other studies conducted in India. For example, Gangwar et al. observed similar trends among medical students in North India, highlighting associations between obesity, dietary habits, and low levels of physical activity. Additionally, studies like that of Dumpala et al. in South India reflect comparable prevalence rates and underscore the influence of lifestyle patterns, such as frequent fast-food consumption and sedentary behavior, especially among male students.[6,7]

A major finding in our study was the significant association between BMI and gender. Male students were observed to have higher odds of being overweight or obese compared to female students (OR = 34.999, P = .028). This gender difference is consistent with the findings of Malik et al. and Makkawy et al.,[8,9] who reported similar trends among male students in Saudi Arabia, with increased fast-food consumption and lower physical activity levels contributing to elevated BMI in male students. In both studies, cultural norms and social habits among men, such as a higher likelihood of engaging in sedentary activities and consuming calorie-dense diets, were suggested as potential contributors. These gender-based differences indicate the need for tailored obesity prevention programs that consider specific lifestyle risks associated with each gender group.

Our study also identified a strong correlation between family history of obesity and current BMI, with 58.3% of obese and 29.7% of overweight against only 19.4% of normal weight students reporting a family history of obesity. This is corroborated by Fernandez et al.,[10] who reported that family history was a major determinant of BMI among medical students in Pune, India. Family history is a well-established predictor of obesity, as it encompasses both genetic predispositions and shared lifestyle habits within families. High BMI within families often results from a combination of genetic factors and environmental influences, such as shared dietary habits and physical activity levels. Targeted counseling and lifestyle interventions are particularly recommended for students with a known family history of obesity to help mitigate the risk associated with genetic predispositions.

Dietary habits also emerged as significant predictors of obesity in our study. We found a substantial correlation between BMI and breakfast consumption, with 34% of overweight and obese students reporting that they frequently skipped breakfast. This aligns with the work of Chhabra et al.,[11] who noted that skipping breakfast was common among overweight students and associated it with metabolic disruptions and compensatory eating later in the day. The omission of breakfast can trigger overeating later in the day, as hunger accumulates and leads to higher-calorie intake in subsequent meals. Regular breakfast consumption is known to improve metabolic rates and assist in maintaining balanced energy levels throughout the day, making it an essential component of healthy dietary practices for weight management.

Our study further highlighted the impact of high-calorie beverage consumption on BMI. Students who reported consuming beverages like tea, coffee, or sweetened juices more than five times a day exhibited significantly higher BMI levels. Similar results were observed in the systematic review by Malik et al.,[8] who found that high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages correlates with annual weight gain. In our population, the high intake of these beverages likely reflects a compensatory behavior for inadequate meals or long hours without eating, common among medical students who face intense academic schedules. This behavior not only increases daily caloric intake but can also disrupt metabolism over time, promoting weight gain. Reducing the intake of high-calorie beverages and opting for healthier alternatives, such as water or unsweetened teas, could be a beneficial intervention for weight management.

Regarding physical activity, our findings did not show a significant correlation between activity levels and BMI, although 47.7% of students reported inadequate physical activity. This lack of association contrasts with the results of Banerjee and Khatri, who observed a significant correlation between physical inactivity and BMI, noting that students with low physical activity levels were more likely to be overweight or obese. Banerjee and Khatri attributed this to barriers such as academic pressures and limited time for exercise, factors that are likely present in our sample as well. However, our findings might suggest that physical inactivity alone is insufficient as a predictor of obesity in medical students, possibly due to variations in baseline activity levels or access to exercise facilities in different regions. Despite the lack of direct correlation, promoting physical activity remains essential for overall health, as exercise contributes to energy balance, cardiovascular health, and mental well-being. Academic institutions could provide more accessible and flexible exercise options for students to encourage regular physical activity.[12]

Our study also examined the relationship between BMI and stress, finding no significant correlation between BMI and self-reported stress levels. Approximately 65% of students reported high stress levels, regardless of their BMI, indicating that stress may not directly influence BMI in this sample. This finding is consistent with the work of Srinivasan et al.[13] who noted that stress levels among medical students were not directly associated with weight gain. However, the relationship between stress and eating behaviors varies widely, with some individuals experiencing increased appetite and others losing appetite under stress. Stress management programs tailored to individual coping mechanisms may help address the varying impacts of stress on eating behaviors and weight management.

Interestingly, our study identified an inverse association between obesity and depression/anxiety, with an odds ratio of 0.009 (P = .017), suggesting that students with mental health concerns may be less likely to be obese. This finding is consistent with the results of Srinivasan et al.,[13] who observed that stress-induced appetite suppression could result in reduced caloric intake among students with high anxiety or depression levels. This inverse relationship highlights the complexity of the interaction between mental health and obesity, suggesting that some students may respond to stress with decreased food intake, whereas others may resort to stress-induced eating. Providing mental health support tailored to students’ specific needs and coping strategies could play a valuable role in managing obesity. Addressing both the psychological and physiological aspects of weight gain in medical students can provide a more holistic approach to obesity prevention and treatment.

Our findings on the significant relationship between higher BMI and the prevalence of stretch marks align with prior research conducted in India. For instance, Verma et al.[14] reported that approximately 43% of individuals with obesity developed stretch marks, indicating a clear correlation between increased body weight and dermal changes. This study supports our observations, where 73% of overweight and 75% of obese students exhibited stretch marks, compared to 43.2% in the normal weight category. Such consistency across studies underscores the need for effective weight management interventions to reduce the prevalence of obesity-related skin changes among at-risk populations.

Also, a significant association was found between skipping meals and BMI, with 75% of obese students never skipping meals, while only 32.4% of overweight and 43.2% of normal-weight students reported the same (P = .026). This contrasts with findings from Bhutani et al.[15] who noted that meal skipping was more prevalent among individuals with higher BMI, often leading to compensatory overeating later in the day. These differences emphasize the complex relationship between eating patterns and weight management.

Strengths

This study offers significant insights into the prevalence of obesity among North Indian medical students, a demographic frequently neglected in obesity research. The study provides a thorough examination of the relationships between BMI and characteristics such as family history, eating habits, and gender by emphasizing sociodemographic and lifestyle elements. The employment of a cross-sectional design with a sample from a tertiary institution guarantees extensive representation among this particular student demographic. The study used sophisticated statistical analysis, including logistic regression, to identify significant predictors of obesity, thereby enhancing the credibility of the findings and enabling tailored suggestions for obesity prevention among medical students.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study constrains causal inference, as it gathers data at a singular time point. Self-reported information regarding food, physical exercise, and mental health may add bias, potentially affecting accuracy. The research concentrates on a single higher institution in North India, perhaps constraining the applicability of the findings to other locations or student demographics. Convenient sampling may result in selection bias, as it includes only those people who are willing to participate. Furthermore, BMI, employed as the principal metric for obesity, fails to consider variables such as muscle mass, potentially neglecting particular health intricacies.

Recommendations

Institutions should put in place focused interventions, like gender-specific health programs that take into account students’ eating and exercise habits, to combat obesity among medical students. Frequent nutritional guidance, encouraging balanced eating, and cutting back on high-calorie beverages could all help to reduce the risk of obesity.

Implications

Obesity in North Indian medical students is influenced by various factors, including genetics, dietary habits, and mental health, contributing to increased risks of physical and psychological health issues. These findings highlight the urgency of addressing modifiable risk factors like breakfast skipping and sedentary lifestyles, as well as the importance of recognizing genetic predispositions

Conclusion

The findings from our study, supported by both descriptive and logistic regression analyses, identify several strong predictors of BMI, such as gender, family history, and certain dietary behaviors, with depression/anxiety showing an inverse relationship with BMI.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank all the medical undergraduates who took part in the study.

Funding Statement

This was a self-funded study.

References

- 1.Manojan K, Benny P, Bindu A. Prevalence of obesity and overweight among medical students based on new Asia-pacific BMI guideline. Kerala Med J. 2019;12:13–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue B, Zhang X, Li T, Gu Y, Wang R, Chen W, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of obesity among university students. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:4539–46. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assir MK, Khan Z, Shafiq M, Chaudhary A, Jabeen A. High prevalence of preobesity and obesity among medical students of Lahore and its relation with dietary habits and physical activity. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20:206–10. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.176357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alqassimi S, Elmakki E, Areeshi AS, Aburasain ABM, Majrabi AH, Masmali EMA, et al. Overweight, obesity, and associated risk factors among students at the faculty of medicine, Jazan university. Medicina. 2024;60:940. doi: 10.3390/medicina60060940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Sabharwal RK, Bajaj JK, Samal IR, Sood M. Age and gender based prevalence of obesity in residents of Punjab, India. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2019;8:1038. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gangwar V, Mandal SK, Verma MK. Study of overweight and obesity and associated factors among undergraduate medical students in North India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2019;7:102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumpala S, Chadaram B, Berad A. Prevalence of overweight/obesity among medical students at Suraram, India. [[Last accessed on 2025 Feb 26]];Int J Community Med Public Health. 2018 5:5338–42. Available from: https://www.ijcmph.com/index.php/ijcmph/article/view/3844 . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:274–88. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makkawy E, Alrakha A, Al-Mubarak A, Alotaibi H, Alotaibi N, Alasmari A, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and their associated factors among health sciences college students, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:961–7. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1749_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez K, Singru SA, Kshirsagar M, Pathan Y. Study regarding overweight/obesity among medical students of a teaching hospital in Pune, India. Med J Dr DY Patil Univ. 2014;7:279–83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chhabra P, Grover VL, Aggarwal K, Kanan AT. Nutritional status and blood pressure of medical students in Delhi. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:248–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee A, Khatri S. A study of physical activity habits of young adults. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:450–1. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.69292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srinivasan K, Vaz M, Sucharita S. A study of stress and autonomic nervous function in first-year undergraduate medical students. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;50:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma SB, Wollina U, Lotti T. Obesity and skin: Are we looking at the right perspectives? J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2017;10:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhutani S, Varma P, Tripathi A. Meal skipping, eating patterns, and BMI among young adults in urban India. Indian J Nutr Diet. 2020;57:287–95. [Google Scholar]