Abstract

Growth factor-induced RTK/RAS/MAPK signaling is crucial for cell cycle progression, including G1 to S and G2 to M phase transitions. However, the regulatory mechanism of MAPK (ERK) in the S–G2M phase remains unclear. In this study, we analyzed the nuclear translocation dynamics of fluorescently labeled ERK induced by EGF during cell cycle progression and simultaneously analyzed the membrane translocation dynamics of GRB2 and PI3K. The transient ERK dynamics in a population of cells with a high frequency of G0/G1 cells became sustained with the increase in S–G2M cells. The sustained localization of PI3K, rather than GRB2, showed a stronger correlation with nuclear ERK localization. PI3K-mediated PAK1 activation was essential for ERK translocation. EGFR/PI3K clusters frequently formed on the plasma membrane and were rapidly endocytosed in the high G0/G1 cell population, resulting in transient PI3K localization, whereas dispersed PI3K predominated in the high S–G2M cells, resulting in sustained PI3K localization. On the other hand, PAK1 remained on the plasma membrane. Our results suggest that the sustained spatial colocalization of PI3K and PAK1, particularly in the S–G2M phase, prolonged the PAK1 signaling for ERK activation. Sustained ERK activation was also correlated with a shorter time to cell division.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-13686-w.

Subject terms: Growth factor signalling, Cellular imaging

Introduction

Growth factor signals drive cell cycle progression by regulating the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)/RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway and cyclin-Cdk complex/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) activity1,2. Earlier studies using quiescent cells led to a model in which cells sense MAPK activation in the early G1 phase, before passing the restriction point (R point), and synthesize DNA for cell division3,4. However, recent studies using cycling cells have revealed that MAPK signaling regulates cell cycle progression in the G2 phase as well as the G1 phase5–7. However, the regulatory mechanisms of MAPK signaling in each cell cycle phase and their contribution to cell cycle progression are not completely understood.

Extracellular related kinase 1 and 2 (ERK), a MAPK, plays an important role in cell cycle progression in response to epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation6,8. After phosphorylation, ERK is translocated into the nucleus and regulates transcription factors related to cell cycle progression9–11. In the G1 phase, ERK activation promotes the transcription of cyclin D1, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6), and CDK2 to support the G1 to S transition8. ERK activation also regulates the expression level of the Cdk inhibitor p21Cip1, which inhibits the cyclin-CDK complex and arrests the cell cycle12,13. The balance between ERK-induced cyclin D1 and p21Cip1 expression levels depends on the amount and duration of ERK activation14,15. Low or transient ERK activation induces cell cycle arrest, while high or sustained activation promotes progression, through reciprocal regulation of cyclin D1 and p21. ERK also facilitates G2/M transition by promoting nuclear translocation and activation of CDK1/cyclin B16–20. Cyclin D1 expression and CDK2 activity are also stimulated by ERK in the G2 phase, leading to continuous cell cycle progression5,6,21. However, some reports have shown that sustained activation of the ERK pathway with hepatocyte growth factor or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate in the S‒G2 phase causes cell cycle arrest in the G2 phase22,23. Thus, although the duration of ERK activation is an important factor in cell cycle progression, the effects of the strength and duration of activation depend on the cell type, and the role of ERK activity during the G2 phase remains controversial.

Various molecular mechanisms have been proposed to regulate the activation dynamics of ERK. These include growth factor and RTK-dependent regulation24positive and negative feedback loops in the RAF‒mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)‒ERK cascade25,26crosstalk between the RAS‒MAPK and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)‒AKT pathways27,28and RAS- and RAS-related protein (RAP)-dependent regulation29–31. Many RTKs activate PI3K‒AKT signaling in addition to the RAS‒MAPK pathway. Although AKT signaling negatively regulates ERK activation32the GRB2-associated binder 1 (GAB1)‒PI3K pathway provides a positive feedback loop that enhance ERK activation28,33. PI3K mediates AKT and 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) recruitment to the plasma membrane via phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) production. Additionally, PI3K activates Rac1 GTPase (RAC1), which stimulates p21-activated kinase (PAK1/2) to scaffold AKT activation by PDK134. PAK1/2 and PDK1 phosphorylate and activate RAF, MEK, and ERK35–37. We previously showed that SHC-mediated PI3K signaling prolongs the duration of ERK activation and is important in determining cellular responses38. Genetic alterations such as K-RAS mutation is one of the most common driver mutations in lung cancer39activating RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, and playing crucial roles in regulating cell cycle progression40.

In the present study, we sought to determine the specificity of the ERK dynamics and elucidate the mechanism involved in the regulation of ERK activation specific to each cell cycle phase. We used multi-mode dual-color fluorescence microscopy to observe fluorescently labeled GRB2, PI3K, and ERK in asynchronous human lung adenocarcinoma cells (A549) stimulated with EGF, and analyzed the translocation dynamics of these proteins in each cell cycle phase. The biochemical and imaging analyses revealed that sustained ERK activation is mainly observed in the S–G2M phase and is regulated by membrane-localized PI3K‒PAK1 signaling.

Results

Cell cycle progression in A549 cells

We measured the cell cycle transition in A549 cells using the Cell-Clock cell cycle assay kit. Approximately 80% of the cells were arrested in the G0/G1 phase after serum starvation for 24 h (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Subsequent supplementation with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) promoted cells to shift from the G0/G1 phase to the S–G2M phase over time. The fraction of cells in the G0/G1 phase was lowest at 6 h but then increased, and these cells were predominant at 12 h. To identify the cell cycle phase of live cells under a fluorescence microscope, we quantified DNA content by staining with a cell-permeable DNA fluorescent dye (Supplementary Fig. S1b, c). As expected, the fluorescence intensity of the nucleus increased over time after supplementing the serum-starved synchronous cells with 10% FBS (Supplementary Fig. S1b). The fluorescence intensity distributions at each timepoint were fitted with the sum of two log-normal functions corresponding to the G0/G1 and S–G2M states, respectively (as described in the Materials and Methods). The ratios of the two populations changed over time after serum supplementation, consistent with the cell cycle progression measured using the Cell-Clock cell cycle assay kit (Supplementary Table S1).

For the following experiments, we divided the total distribution of asynchronous cells into two fractions at the intersection between the two log-normal distributions (Supplementary Fig. S1c). The low- and high-DNA-stained fractions included a mixture of G0/G1 and S–G2M cells. The low-DNA-stained fraction mainly contained cells in the G0 and G1 phases (hereafter referred to as low-DNA cells), and the high-DNA-stained fraction mainly contained cells in the S, G2, and M phases (hereafter referred to as high-DNA cells) (Supplementary Table S2). Although the separation of the two populations into G0/G1 and S–G2M phases was imperfect, the accuracy was considered sufficient for our analyses at examining differences in molecular response dynamics. We estimated that the high-DNA cells included ~ 17% G0/G1 cells and the low-DNA cells included ~ 9% S–G2M cells.

The ERK response became sustained as the population of S–G2M cells increased

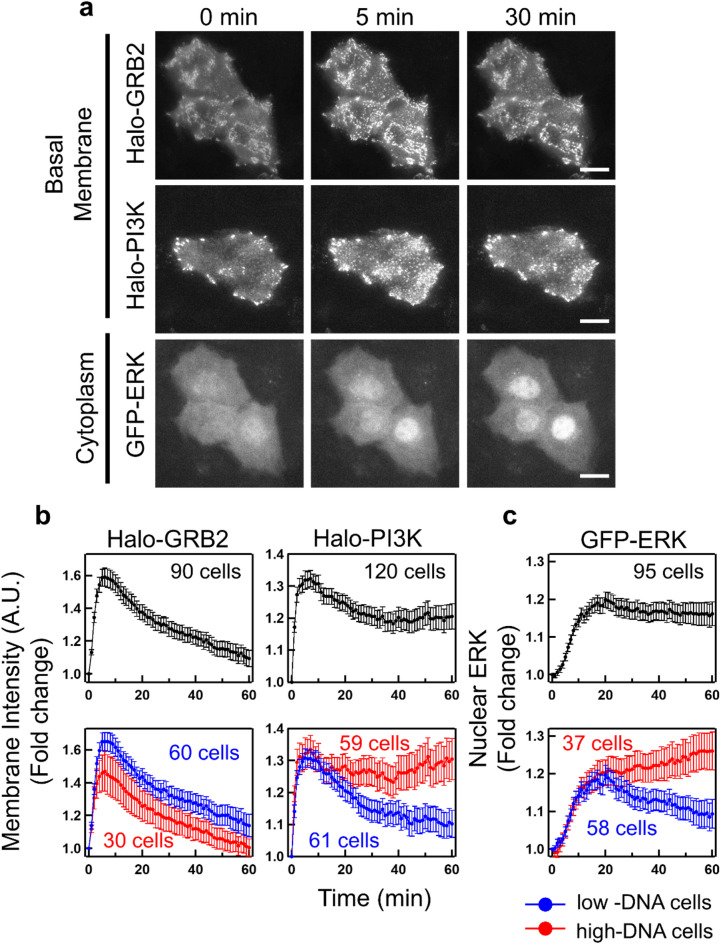

To visualize GRB2 and ERK, or PI3K and ERK simultaneously in the same cells, Halo protein was fused to the N-terminus of GRB2 and PI3K (p85α subunit), hereafter referred to as Halo-GRB2 and Halo-PI3K (Supplementary Fig. S2a), and green fluorescent protein (GFP) was fused to ERK2 (GFP-ERK) (Supplementary Fig. S2b). The apparent molecular masses of Halo-GRB2, Halo-PI3K, and GFP-ERK proteins were determined by Western blotting analysis to be 57, 118, and 72 kDa, respectively, consistent with their expected molecular sizes. The relative expression levels of transfected Halo-GRB2, Halo-PI3K, and GFP-ERK were similar to or lower than those of the endogenous molecules and did not affect endogenous expression (Supplementary Fig. S2c). To investigate the spatiotemporal characteristics of the responses of GRB2, PI3K, and ERK to EGF stimulation, we observed the translocation of these proteins in asynchronous cell populations. Halo-GRB2 and Halo-PI3K were conjugated with tetramethyl rhodamine (TMR) and observed using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. GFP-ERK was observed using epi-illumination (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Translocation dynamics of GRB2 and PI3K to the plasma membrane and ERK to the nucleus. (a) TIRF images of Halo-GRB2 and Halo-PI3K on the basal plasma membrane and epi-fluorescence images of GFP-ERK in A549 cells before (0 min) and after (5 and 30 min) EGF stimulation at 25 °C. The images of GRB2 and ERK were acquired in the same field of view. Scale bar = 20 μm. (b, c) Time courses of the fluorescence intensities of Halo-GRB2 and Halo-PI3K on the basal membrane (b) and GFP-ERK in the nucleus (c) in cells stimulated with 16 nM EGF at time 0. The vertical axes show the fold changes normalized to the values obtained before stimulation. Data for all cells (upper graph, black), low-DNA cells (lower graph, blue), and high-DNA cells (upper graph, red) are shown as the mean ± SEM, based on the number of cells indicated in (b) and (c) from 3‒4 independent experiments.

Halo-GRB2 and Halo-PI3K were partially present on the plasma membrane in the resting cells, and their membrane localization increased after EGF stimulation. GFP-ERK was found in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, and translocated from the cytoplasm into the nucleus following EGF stimulation (Fig. 1a). mEGFP-C2 (GFP) alone was distributed throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus, and its nuclear concentration did not increase after EGF stimulation, but ERK tagged with Tag-RFP-T instead of GFP was found to undergo EGF-induced translocation into the nucleus, indicating the translocation was specific for ERK (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b). Although, nuclear concentrations of GFP-ERK (or Tag-RFP-T-ERK) were correlated with corresponding cytoplasm concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S3c, d), the fold-increase in the nuclear translocation of ERK after EGF stimulation was not affected by this ratio (Supplementary Fig. S3e, f).

We compared the fold-increase in the translocation dynamics of Halo-GRB2, Halo-PI3K, and GFP-ERK averaged across all cells (Fig. 1b, c upper). The nuclear translocation of GFP-ERK was sustained, the membrane localization of Halo-PI3K was more transient, and the membrane localization of GRB2 was even more transient.

DNA staining just after the translocation measurements allowed us to classify the measured cells into low- and high-DNA cells and to find differences in protein translocation dynamics between each cell population. This revealed that the sustainability of PI3K and ERK activation dynamics, but not GRB2 activation dynamics depended on the cell cycle phases (Fig. 1b, c lower). The membrane localization of Halo-GRB2 was transient, and minor differences were observed between cells with different levels of DNA staining (Fig. 1b). Western blotting showed that the phosphorylation of ERBB receptors and RAF, a RAS effector similar to PI3K, did not differ significantly in terms of persistence between serum-starved cells and cells supplemented with FBS for 6 h after serum starvation (Supplementary Fig. S4). We observed minor differences in the peak levels between the early response of ERBB3 and ERBB4 (Supplementary Fig. S4a, b). The membrane localization of Halo-PI3K and the phosphorylation of PI3K were transient in the low-DNA and serum-starved cells, respectively, but these changes were sustained for up to 60 min after EGF stimulation in the high-DNA cells and in cells supplemented with FBS, respectively (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S4b). The translocation dynamics of GFP-ERK were transient in low-DNA cells but sustained in high-DNA cells. EGF-stimulated ERK phosphorylation showed a more sustained response in cells supplemented with FBS for 6 h after serum starvation compared with that in serum-starved cells (Supplementary Fig. S4a, b). These results support the idea that ERK activation is more transient in G0/G1 cells and more sustained in S–G2M cells.

ERK dynamics in S–G2M cells are dependent on PI3K activity

To elucidate the molecular mechanism involved in the regulation of the activation dynamics of ERK, we focused on the effect of PI3K activity. Pretreating cells with a PI3K inhibitor (GDC-0032) even at the highest concentration used in this study (10 µM) did not significantly affect the phosphorylation levels of ERBB1‒4, RAF, or MEK, suggesting that PI3K inhibition does not influence the activation of these proteins. By contrast, GDC-0032 significantly decreased the phosphorylation levels of PAK1/2 and AKT, substrates of PI3K, that were dependent on the concentration of GDC-0032 (Supplementary Fig. S5). Thus, GDC-0032 inhibition selectively modulated the PI3K‒AKT pathway. Furthermore, treatment with 10 µM GDC-0032 decreased ERK phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S5a, c), suggesting that PI3K activity regulates ERK phosphorylation.

We next measured the translocation dynamics of ERK to the nucleus in cells pretreated with 0.01 µM and 10 µM of GDC-0032, referred to as low-GDC and high-GDC, respectively (Fig. 2a). Although the peak amplitude at the initial response (~ 20 min) was decreased after low-GDC treatment, the initial and late amplitudes (> 30 min) of ERK were decreased after high-GDC treatment (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Effects of PI3K inhibition on the translocation dynamics of ERK. (a) Epi-fluorescence images of GFP-ERK in cells pretreated with 0.01 µM (low-GDC) and 10 µM (high-GDC) GDC-0032 before (0 min) and after (15 and 60 min) EGF stimulation. Scale bar = 20 μm. (b, c) Time courses of the nuclear translocation of GFP-ERK following EGF stimulation. (b) shows cells pretreated with low (orange) or high (black) GDC. The time course of ERK for cells in the control condition (shown in Fig. 1c) is provided for comparison (red in b). The vertical axes show the fold changes normalized to the values obtained before stimulation. Data for all cells (b), low-DNA cells (c, blue), and high-DNA cells (c, red) are shown as the mean ± SEM, based on the number of cells indicated in (b) and (c) from 4–5 independent experiments. (d) Initial amplitude (upper graph) and late amplitude (lower graph) calculated as the average initial peak (15–25 min) and late response (50–60 min) in each cell. Dot plots for low-DNA cells (blue circles) and high-DNA (red circles) cells show the mean ± SEM (black lines). *p < 0.05 (two-tailed Welch’s t-test).

We separated the cell responses for the high- and low-DNA populations (Fig. 2c, d). In the high-DNA cells, the initial and late amplitudes of the ERK response decreased after low-GDC treatment. In the low-DNA cells, however, only a decrease in the initial peak was observed under the same GDC treatment. high-GDC treatment decreased the initial and late amplitudes in the low- and high-DNA cells, although the magnitude of decreases was greater in the high-DNA cells. The stronger effects of GDC on the high-DNA cells than on the low-DNA cells suggest that regulatory effects of PI3K on ERK dynamics are stronger in the S–G2M phase than in the G0/G1 phase. The late amplitude in the high-DNA cells was particularly sensitive to PI3K inhibition. These findings suggest that the sustainability of the ERK response in the high-DNA cells was likely to be maintained by PI3K signaling.

Plasma membrane-localized PAK1 is a positive regulator of ERK activation

To elucidate how PI3K signaling maintains ERK activation, we next focused on two downstream kinases, PAK1/2 and PDK1, which activate AKT and partially facilitate ERK phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of PAK1 at Thr423 by PDK1 is known to induce its activation41. Since PI3K inhibition decreased the phosphorylation of PAK1/2 (Thr423/Thr402) (Supplementary Fig. S5a, c), we investigated whether PAK1/2 is involved in PI3K–ERK signaling in a cell cycle-dependent manner.

Similar to PI3K inhibition, pretreatment with the PAK1 inhibitor (IPA-3) did not significantly decrease in the phosphorylation levels of ERBB1‒4, RAF, or MEK (Fig. 3a‒c). Additionally, the phosphorylation levels of PAK1/2, AKT, and ERK decreased with increasing IPA-3 concentration, suggesting that PAK1 regulates ERK phosphorylation. Pretreatment with the PDK1 inhibitor (MP7) decreased AKT phosphorylation, but did not significantly decrease ERK phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S6a‒c). Thus, PAK1, rather than PDK1, seems to be involved in the regulation of PI3K‒ERK signaling.

Fig. 3.

Effects of the PAK1 inhibitor IPA-3 on RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling. (a) Phosphorylation levels of the ERBBs (B1–B4), RAF, MEK, ERK, AKT, and PAK1/2 at the indicated positions after EGF stimulation for 5 min determined by Western blotting. Cells were pretreated with IPA-3 at logarithmic concentrations (0‒10 µΜ) at 37 °C for 30 min before EGF stimulation. Although IPA-3 is specific for PAK187, p-PAK1 and p-PAK2 could not be distinguished in the Western blot. These gel images are cropped. Full-length blots are provided in the Source Data file. (b, c) The phosphorylation levels of the indicated proteins. Data are the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. The black dotted line indicates the normalized value of 1 in cells not exposed to IPA-3. Statistical significance was determined using a Two-tailed paired t-test by comparing values for cells exposed to IPA-3 against those not exposed. *p < 0.05. (d) Epi-fluorescence images of GFP-ERK in cells pretreated with 10 µM IPA-3 before (0 min) and after (15 and 60 min) EGF stimulation. Scale bar = 20 μm. (e, f) Time courses of the nuclear translocation of GFP-ERK following EGF stimulation. In (e), cells pretreated with 10 µM IPA-3 (green) were examined. The time course of ERK in cells under the control conditions (shown in Fig. 1c) is provided for comparison (red in e). The vertical axes show the fold changes normalized to the values obtained before stimulation. Data for all cells (e), low-DNA cells (f, blue), and high-DNA cells (f, red) are shown as the mean ± SEM, based on the number of cells indicated in (e) and (f) from three independent experiments.

We measured the translocation dynamics of ERK in cells pretreated with IPA-3 (Fig. 3d, e). For the average of all cells, the amplitude of the initial response decreased after IPA-3 treatment to a level similar to that observed after low-GDC treatment (Figs. 2b and 3e). After separating the cells into low- and high-DNA cells, we noticed that PAK1 inhibition reduced the initial and late amplitudes of ERK dynamics in high-DNA cells (Fig. 3f). In low-DNA cells, only a slight decrease in the initial response was observed. Although the effect differed between low- and high-DNA cells, IPA-3 inhibited the ERK response in both cell populations. By contrast, PDK1 inhibition caused an increase in the amplitude of the ERK response after the initial peak, mainly affecting the response in low-DNA cells (Supplementary Fig. S6d, e). It is likely that both PAK1 and PDK1 regulate the activation dynamics of ERK across the cell cycle phases, but their roles differ. In the G0/G1 phase, PAK1 positively regulates the initial activation of ERK, whereas PDK1 negatively regulates the ERK activation, mainly in the late response. In the S–G2M phase, PAK1 increases the ERK response throughout the time course, although PDK1 has a minor effect. Overall, PAK1 is a more important factor in mediating ERK dynamics via PI3K.

Spatial segregation of PI3K and PAK1 is correlated with PAK1 activation dynamics

To investigate which factor determines the differences in PI3K translocation dynamics correlated with the cell cycle phase, we focused on the spatial distribution of PI3K on the plasma membrane. PI3K formed foci on the plasma membrane after EGF stimulation in a subset of cells (Fig. 4a, b). By contrast, GRB2 constantly formed foci in cells after EGF stimulation (Fig. 4c). PI3K foci were more frequently observed in low-DNA cells than in high-DNA cells (Fig. 4d). EGF stimulation led to a transient increase in the fluorescence intensity of PI3K foci, peaking at about 10 min, followed by a decrease to the basal levels (Fig. 4e). Therefore, we assessed whether the formation of PI3K foci is correlated with the dynamics of PI3K localization throughout the plasma membrane (Fig. 4f), and we found transient localization of PI3K in cells that formed PI3K foci. This result was not affected by the DNA-staining intensity.

Fig. 4.

Foci formation and localization dynamics of PI3K. (a) TIRF images of Halo-PI3K on the basal plasma membrane before (0 min) and after (5 min) EGF stimulation. Scale bar = 10 μm. The upper panels show a cell that formed PI3K foci and the lower panels show a cell that did not form PI3K foci. (b) Magnified views of the boxed areas in (a), with arrows indicating PI3K foci. Scale bar = 5 μm. (c) TIRF images of Halo-GRB2 on the basal plasma membrane before (0 min) and after (5 min) EGF stimulation. Scale bar = 10 μm. (d) The number of cells examined for the formation of PI3K foci. The numbers in parentheses indicate the fractions of low- and high-DNA cells. The correlation between DNA content and PI3K foci formation was statistically significant (p < 0.05, χ2 test for independence). (e) Time course of the change in intensity of the PI3K foci. The intensity changes were averaged for each cell (39‒86 particles per cell) and the data are shown as the mean ± SEM across 11 cells. (f) Time courses of the plasma membrane localization of PI3K in cells that did (green) or did not (yellow) form foci. The vertical axes show the fold changes normalized to the values obtained before stimulation. Data are the mean ± SEM, based on the number of cells indicated in (d) from six independent experiments.

To investigate the details of foci formation, cells expressing GFP-tagged GRB2 (GFP-GRB2) or PI3K (GFP-PI3K) were stimulated with fluorescently labeled EGF (Rh-EGF) (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S7). GFP-GRB2 and GFP-PI3K foci colocalized with Rh-EGF on the plasma membrane, indicating their incorporation into a complex of EGF ligand-bound EGFRs (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S7a). Subsequently, colocalized Rh-EGF and GFP-GRB2 or GFP-PI3K were accumulated near the nucleus, probably due to EGFR endocytosis (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S7b). Although PAK1 was localized near PI3K foci, it neither accumulated within the foci nor internalized with PI3K (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. S7c upper), and remained localized on the plasma membrane in all cell cycle phases (Fig. 5d, e). RAC1 is required for PAK1 activation42,43but GFP-RAC1 also did not accumulate on the endosomes after EGF stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S7c lower). PAK1/2 phosphorylation was transient in enriched G0/G1 cells (Supplementary Fig. S4b), suggesting that, although PAK1 remains on the plasma membrane regardless of the cell cycle, its activation varies with the cell cycle phase due to differences in PI3K membrane localization. In the S–G2M phase, the localization of PI3K on endosomes is inhibited to prevent segregation from PAK1, which is constantly present on the plasma membrane, resulting in sustained activation of PAK1 and ERK.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of PI3K and PAK1 on the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm after EGF stimulation. (a) TIRF images of GFP-PI3K localization on the plasma membrane in cells before (0 min) and after (5 min) Rh-EGF stimulation. Scale bar = 10 μm. The insets are magnified views of the boxed areas (5 × 5 μm) in the merged images to show the colocalization of the GFP and Rh signals. (b) Confocal images of GFP-PI3K localization in the cytoplasm of cells before (0 min) and after (5 and 30 min) Rh-EGF stimulation. Scale bar = 20 μm. The insets are magnified views of the boxed areas (10 × 10 μm) in the merged images. (c) TIRF images of Halo-PI3K and GFP-PAK1 localization on the plasma membrane in cells before (0 min) and after (5 and 30 min) EGF stimulation. Scale bar = 10 μm. The right-most images are magnified views of the boxed area at 5 min. Scale bar = 1 μm. (d, e) Time courses of the membrane intensity of GFP-PAK1 following EGF stimulation. The vertical axes show the fold changes normalized to the values obtained before stimulation. Data for all cells (d), low-DNA cells (e, blue), and high-DNA cells (e, red) are shown as the mean ± SEM, based on the number of cells indicated in (d) and (e) from three independent experiments.

The dynamics of PI3K and ERK are correlated in single cells

We performed hierarchical clustering of single-cell dynamics data following Halo-PI3K translocation using dynamic time warping (DTW) (Supplementary Fig. S8a). The validation and statistical analyses (Supplementary Fig. S8b‒e) indicated that cells could be classified into at least two populations: one exhibiting transient-like PI3K responses (referred to as transient) and the other exhibiting sustained-like PI3K responses (sustained) (Supplementary Fig. S8f). Based on the PI3K dynamics clustering, we divided the simultaneously measured GFP-ERK dynamics into two corresponding groups, and found a good correlation between PI3K and ERK dynamics in the averages of the cell populations (Supplementary Fig. S8f, g). Specifically, cells with transient PI3K dynamics also showed transient ERK dynamics, while cells with sustained PI3K dynamics showed sustained ERK dynamics. Conversely, two cell populations classified based on ERK dynamics clustering showed transient and sustained dynamics of ERK and PI3K (Supplementary Fig. S9). We also measured DNA content in the same single cells. PI3K dynamics tended to be transient in low-DNA cells, whereas PI3K and ERK dynamics were more likely to be sustained in high-DNA cells (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6.

The correlation between PI3K and ERK dynamics depends on the cell cycle phase. (a, b) Percentages of cells in the low- and high-DNA populations assigned to each class of PI3K (a) and ERK (b) as shown in Supplementary Figs. S8a and S9a, respectively. The number of cells within each of the low- and high-DNA populations is shown above each bar. (c) Correlation between the cluster distributions of PI3K and ERK in the same low-DNA (left panel) and high-DNA (right panel) cells. The numbers in the center of each box indicate the number of cells observed. The percentages in the gray areas represent the fractions of PI3K trajectories assigned to the transient (left) or sustained (right) classes in cells with sustained (upper) or transient (lower) ERK dynamics. The percentages in the white areas represent the fractions of ERK trajectories assigned to the sustained (upper) or transient (lower) classes in cells with transient (left) or sustained (right) PI3K dynamics. The correlation between PI3K and ERK dynamics was statistically significant (p < 0.05, χ2 test for independence). (d) Model for the regulation of ERK activation dynamics by PI3K‒PAK1 signaling. In the G0/G1 phase (left), PI3K accumulates in coated-pit/caveola-like foci with EGFR after EGF stimulation. These foci are internalized, which terminates plasma membrane PI3K‒PAK1 signaling. In the S–G2M phase (right), PI3K is not incorporated into the foci and remains on the cell membrane. Membrane-localized PI3K maintains PAK1 phosphorylation via RAC1 to sustain ERK activation.

The cell population was divided into four groups based on the simultaneous classifications of PI3K and ERK (Fig. 6c). This analysis revealed a significant correlation between the PI3K and ERK dynamics (p < 0.05; χ2 test for independence). The sustained PI3K dynamics were correlated with sustained ERK dynamics regardless of DNA staining level, but the transient PI3K dynamics were hardly correlated with the ERK dynamics. From the perspective of ERK dynamics, the sustained ERK dynamics were primarily observed in high-DNA cells with sustained PI3K dynamics. By contrast, in the low-DNA cells, the sustained ERK dynamics were negatively correlated with the sustained PI3K dynamics. Furthermore, the transient ERK dynamics were strongly correlated with the transient PI3K dynamics in the low-DNA cells, but not in the high-DNA cells. On the other hand, GRB2 dynamics predominantly exhibited transient across the cell population, and ERK dynamics did not differ significantly between two groups based on GRB2 dynamics clustering, regardless of DNA staining levels (Supplementary Figs. S10a‒g and S11a‒c).

In summary, although the PI3K dynamics in the low-DNA cells were biased towards transient activity, this bias did not effectively regulate the sustainability of the ERK dynamics. By contrast, in high-DNA cells, PI3K dynamics, but not GRB2, were biased towards sustained activity with a strong correlation with sustained ERK dynamics, indicative of increased importance of PI3K regulation in the S–G2M phase (Fig. 6d).

Cells with a sustained ERK response were ready for cell division

Finally, to examine the correlation between EGF-stimulated ERK dynamics and cell cycle progression, we measured ERK dynamics and the time to cell division for up to 9 h after EGF stimulation in cells pretreated with or without a MEK inhibitor (trametinib) (Fig. 7a, b). EGF stimulation accelerated the cell cycle progression and cell division in control cells without trametinib, but these effects were suppressed by 1 nM trametinib. Pretreatment with 1 nM trametinib partially inhibited the basal ERK phosphorylation but did not inhibit basal MEK, RAF, and PI3K phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). Notably, inhibition of ERK phosphorylation was more pronounced after EGF stimulation. Higher concentrations of trametinib increased RAF and MEK phosphorylation in the basal state, possibly due to the inhibition of negative feedback from ERK.

Fig. 7.

ERK dynamics and cell division. (a, b) Typical epi-fluorescence images of GFP-ERK in cells following EGF stimulation at 37 °C. Cells were pretreated without (a) or with (b) 1 nM trametinib. Scale bar = 10 μm. (c) The relative nuclear concentration of ERK before EGF stimulation (nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio) in divided (red), non-divided (gray) cells without trametinib, and cells pretreated with 1 nM trametinib (green). Single-cell data (dots) are shown with the mean ± SEM (black lines). No divided cells were detected after treatment with trametinib. ns, not significant in the two-tailed Student’s t-test. (d) Time-course of ERK translocation following EGF stimulation in cells observed in (c). The vertical axis shows the fold change normalized to the value obtained before stimulation. Data for each cell category are shown as the mean ± SEM, based on the number of cells indicated in (d) from three independent experiments. (e) Heatmap and dendrogram depicting the clustering of normalized ERK translocation dynamics (63 cells). The right color bar indicates divided (red) and non-divided (gray) cells. (f) Cumulative probability of cell division to the time after EGF stimulation for the cells shown in (d). The populations shown in red and blue (e, f) exhibited sustained and transient ERK responses, respectively.

There was no significant difference in basal ERK localization between the control cells that exhibited or not exhibited EGF-induced cell division, nor between the trametinib-treated cells (Fig. 7c). However, nuclear translocation of ERK within 60 min of EGF stimulation was stronger and more sustained in divided cells than in non-divided cells (Fig. 7d). In the trametinib-treated cells, ERK translocation resembled that in the non-divided control cells. No cell division was observed after EGF stimulation for cells pretreated with trametinib. When cells without trametinib treatment were classified into two populations according to the ERK translocation dynamics (Fig. 7e), cells with a sustained response were significantly more likely to divide within 9 h after EGF stimulation. Trametinib treatment increased the proportion of cells exhibiting a transient ERK response (Supplementary Fig. 12c). These results suggest that ERK activation following EGF stimulation, rather than the basal ERK activity, promotes cell cycle progression and cell division.

Discussion

ERK activation, regulated by the RAS‒MAPK and PI3K‒AKT pathways, plays a critical role in cell cycle progression. It is thought that the intensity and dynamics of ERK are important for regulating cellular functions. However, the regulation of ERK activation dynamics in each cell cycle phase remains unclear. Here, we investigated the translocation dynamics of GRB2, PI3K, and ERK2, corresponding to their activation process, in different cell cycle phases. We found that PI3K and ERK2 dynamics in response to EGF stimulation varied with the cell cycle phase, and the dynamics were transient in the G0/G1-accumulated population (low-DNA cells) and sustained in the S–G2M-accumulated population (high-DNA cells) of A549 cells (Fig. 1b, c). In single cells, the sustained ERK2 dynamics were strongly correlated with the sustained PI3K dynamics in the high-DNA cells, but the transient ERK2 dynamics were weakly correlated with the transient PI3K dynamics in the low-DNA cells (Fig. 6c). These results suggest that the regulation of PI3K and ERK2 activation during EGF stimulation changes during cell cycle progression. In particular, PI3K-mediated PAK1 activation on the plasma membrane is essential for sustained ERK2 activation, especially during the S–G2M phase (Fig. 6d). We further revealed that PI3K-PAK1-mediated regulation of ERK is an important mechanism for cell division, and that this mechanism changes dynamically depending on the cell cycle phase. ERK1 and ERK2 are functionally redundant and exhibit a similar nuclear translocation responses44,45therefore, our observations should reflect general ERK dynamics.

The effects of inhibitors suggested that PI3K regulates the activation dynamics of ERK through PAK1 localized on the plasma membrane (Figs. 2 and 3). PAK1 and PDK1, which lie downstream of PI3K, contribute to AKT phosphorylation and RAS/MAPK signaling. PDK1 phosphorylates AKT (Thr308), while PAK1 modulates AKT indirectly by influencing upstream or parallel signaling pathways35–37. PAK1 phosphorylates RAF (Ser338) and MEK1 (Ser298), to enhance MEK1 phosphorylation (Ser218/222) and its subsequent activation44–46. PDK1 directly phosphorylates MEK1 (Ser222) and MEK2 (Ser226) without influencing RAF activation47. In our experimental conditions, the effects of PAK1 and PDK1 were distinct. Treatment with a PAK1 inhibitor decreased ERK translocation depending on the cell cycle phase, similar to the effects of a PI3K inhibitor (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S5). Although both inhibitors decreased AKT phosphorylation (Thr308), PDK1 inhibition did not decrease but actually increased ERK translocation, probably due to a decreased negative feedback effect of AKT (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. S6c). However, this feedback is unlikely to account for the cell cycle-dependent sustainability of ERK activation.

EGF binds to EGFR (ERBB1), inducing either homodimerization or heterodimerization with the other three ERBBs, and subsequently promotes oligomer formation and phosphorylation of ERBB1‒4. We confirmed that ERBB1‒4 phosphorylation after EGF stimulation, implying receptor activation via hetero-oligomer formation (Supplementary Fig. S4). ERBB phosphorylation dynamics hardly differed between the cell cycle phases; only slight decreases in ERBB3 and ERBB4 phosphorylation were observed after serum treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4b), indicating that the ERBB activation dynamics may not account for the differences in PI3K dynamics. By contrast, the endocytosis of EGF with PI3K binding sites induces transient PI3K translocation to the plasma membrane (Fig. 4a, f). Foci formation and endocytosis of the PI3K binding sites were less stimulated in the S–G2M accumulated population (Fig. 4d). Although clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) was previously thought to be suppressed during mitosis48,49recent studies suggest CME persists throughout the cell cycle50–52. These reports and our experiments suggest that it is not the ease of endocytosis that varies, but rather the amount of PI3K associated with EGFR endosomes that varies among the cell cycle phases.

The roles of PI3K endosomal signaling remain to be elucidated. Several studies using various cell types and stimuli have suggested that growth factor-dependent activation of PI3K occurs on the endosomal compartments along microtubules with PIP3 production and AKT activation53–55. However, in our experiments, PAK1 and AKT showed weak, transient activation in serum-starved cells with enriched G0/G1 cells and strong PI3K accumulation on endosomes. Strong or sustained responses of AKT and PAK1 were observed after serum application that induced the transition of cells to the S–G2M phase, correlating with sustained membrane localization of PI3K (Supplementary Fig. S4b). EGFR is internalized via CME and non-clathrin endocytosis (NCE), depending on the cellular and growth conditions56–58. It was reported that stimulation with a low concentration of EGF (1 ng/mL) leads to internalization of EGFR via CME and recycling to the cell membrane. However, at high concentrations of EGF (20–100 ng/mL), EGFR is internalized via CME and NCE and is predominantly trafficked to lysosomes for degradation59. The internalized EGFR may have been degraded and PI3K signaling terminated due to the loss of membrane association sites. However, we observed PI3K accumulation in the EGF endosomes, even after 30 min of EGF stimulation (Fig. 5b). AKT signaling may occur on endosomes, whereas PAK1 signaling seems to occur on the plasma membrane. Using TIRF and confocal imaging, we observed that PAK1 and RAC1 remained localized at the plasma membrane after EGF stimulation (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. S7c). RAC1 is known to mediate PAK1/2 activation upon activation by PI3K34. We also found that sustained PI3K localization at the plasma membrane correlated with prolonged PAK1 activation (Supplementary Fig. S4). PAK1/2 are the activators of RAF44–46. Our findings suggest that the localization of PI3K on the plasma membrane regulates the sustainability of RAF activation caused by RAC1-PAK1/2 signaling. Thus, the modulation of PI3K localization during the cell cycle influences the duration of ERK signaling.

We observed localization of PI3K to regions resembling focal adhesion structures, especially in the low-DNA cells (Figs. 1a and 4a). Appropriate changes in the cytoskeleton and cell adhesion during cell cycle progression are essential for normal cell proliferation60. Destruction of the actin cytoskeleton in the G1 phase leads to S phase arrest61,62. Conversely, enhanced cell adhesion in the G2 phase reduces the number of cells entering mitosis63. PI3K interacts with proteins involved in cell adhesion and cytoskeletal remodeling64–66. The early endosomes colocalize with focal adhesions and are involved in the adhesion turnover67–69. In addition, actin cytoskeletal structures restrict the diffusion of EGFR across the cell membrane70. The EGFR clusters become critical nodes in EGF signaling71 and serve as sites for CME and/or NCE72,73. Modifications to the cytoskeleton and cell adhesion during cell cycle progression may influence the ease with which PI3K and EGFR form a complex, as well as the dynamics of their cell membrane localizations that are dependent on the cell cycle phase.

Correlation strength between PI3K and ERK dynamics varied according to the cell cycle phase (Fig. 6c). In the low-DNA cells, the sustained ERK dynamics were hardly correlated with the PI3K dynamics. One potential explanation for this is the presence of additional regulatory mechanisms to PI3K‒PAK1 signaling that maintain ERK dynamics during the G0/G1 phase. Several studies using serum-starved cells have proposed mechanisms for positive regulation of ERK activation, including feedback loops of the RAF‒MEK‒ERK cascade25transcription-induced feedback regulation74and RAS- and RAP-dependent regulation29–31. These mechanisms may maintain the sustained ERK activity in the G0/G1 phase independent of the membrane localization dynamics of PI3K. By contrast, a strong correlation between the sustained PI3K and ERK dynamics was observed in the high-DNA cells (Fig. 6c). This suggests that the effects of the ERK regulatory mechanisms in the G0/G1 phase (described above) decrease in the S–G2M phase, and that PI3K activation has a greater effect on the regulation of ERK sustainability.

The strength of cell–cell communication may vary depending on the cell cycle phases and affect the reaction dynamics. Previous studies have observed the propagation of coordinated ERK waves between neighboring cells, which depends on intercellular communication75–77. However, in our current conditions, we did not observe such propagation or coordinated ERK activation patterns, possibly due to the relatively low cell density. Collective ERK dynamics may emerge under more confluent conditions or in tissue-like environments, thereby enabling an integrated analysis in the mixed context of intracellular coordination and cell cycle dependence. To enable dual-color fluorescence measurements of the reaction dynamics within the same single cells, we roughly classified the cells based on their DNA content. Further subdivision of the cell cycle phases (e.g., early G1, late G1, S, G2, and M phases) using markers such as FUCCI or cyclin-based reporters may enable the detection of more specific phase-dependent PI3K-ERK dynamics. Future studies with a finer subdivision of cell cycle phases will reveal more subtle or detailed phase-specific differences in signaling responses.

Cells with sustained ERK response showed increased cell division efficiency (Fig. 7d, f). This observation is consistent with the assumption that the differential ERK responsiveness to EGF stimulation between the cell cycle phases affects cell cycle progression. Furthermore, sustained ERK activation promotes cell cycle progression. Inhibition of ERK phosphorylation with a low concentration of a MEK inhibitor effectively suppressed cell division, indicating a functional requirement of ERK activation in cell cycle progression (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. S12). Notably, the inhibitory effect was more pronounced on the sustainability in the EGF-stimulated ERK dynamics than the basal ERK activity, suggesting that the post-stimulated ERK response, rather than the basal activity level, is critical for cell division. Our observations are based on the A549 cell line (human lung adenocarcinoma cells), which carries a constitutively active K-RAS mutation (G12S)78,79 that may amplify PI3K signaling, roles of PI3K signaling might be specifically important in cancer cells with enhanced RAS/MAPK or PI3K/AKT signaling. However, the importance of the post-stimulation of ERK activity, rather than the basal activity, for cell division, supports the possibility that similar regulatory mechanisms also work in wild-type or non-transformed cells. Considering that the cell cycle duration of A549 cells is ~ 12 h (Supplementary Fig. S1), the cell division observed after the EGF response is mainly caused by G2 phase cells. However, other reports have suggested that the sustained ERK activation leads to a delay in the G2 phase or cell cycle arrest22,23. This may explain why cell division was not observed in all cells that exhibited sustained ERK activation (Fig. 7e). The response intensity may be a factor promoting cell division of G2 phase cells (Fig. 7d). Another potential explanation is that the low-DNA population contained cells that exhibited sustained ERK dynamics (Fig. 6b).

In conclusion, we found that the prolonged interaction between PI3K and PAK1 on the plasma membrane is a key factor in maintaining the ERK response related to the G2‒M transition. Protein trafficking, which elicits spatial segregation between PI3K and PAK1, is crucial for regulating ERK dynamics. Further studies on the spatial coordination between plasma membrane signaling and endosome signaling of PI3K will reveal details of the mechanisms involved in ERK activation and cell cycle progression.

Methods

Plasmid construction

The cDNA for p85α was kindly provided by Pablo Rodriguez-Viciana at the UCL Cancer Institute. The pmEGFP-C2 (BD Biosciences) transfer vector harboring a monomeric mutation of GFP was constructed by direct point mutation of A206K in the pEGFP-C2 vector, as previously described80. To construct the mEGFP-GRB2 (GFP-GRB2) and mEGFP-ERK2 (GFP-ERK) transfection vectors, CMV-GRB281 and CMV-ERK82 were subcloned into the pmEGFP-C2 vector, as previously described83. The cDNA for PAK1 was obtained from the Kazusa DNA Research Institute. To construct the mEGFP-p85α (GFP-PI3K) and mEGFP-PAK1 (GFP-PAK1) transfection vectors, p85α and PAK1 inserts were subcloned into the EcoRI-BamHI and HindIII-KpnI sites of the pmEGFP-C2 vector, respectively. The cDNA for RAC1 was kindly provided by Toshihide Yamashita at Osaka University. mEGFP-RAC1 was constructed by subcloning RAC1 into the HindIII-BamHI sites of EGFP-C1 (Takara Bio). TagRFP-T-ERK2 was constructed by replacing the mEGFP in the mEGFP-ERK2 vector with the TagRFP-T from the TagRFP-T-C1 vector (Clontech) using the NheI and HindIII restriction sites. The Halo7-C1 vector was constructed by exchanging mEGFP for Halo7 (pFN19 HaloTag T7 SP6 Flexi vector, Promega) in the EGFP-C1 vector. To construct the Halo7-GRB2 (Halo-GRB2) and Halo7-p85α (Halo-PI3K) transfer vectors, the CMV-GRB2 and p85α inserts were subcloned into the BglII-SalI and EcoRI-BamHI sites of the Halo7-C1 vector, respectively.

Cell culture and transfection

A549 cells (RCB3677) were obtained from the RIKEN BioResource Center. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Wako Pure Chemical Industries) supplemented with 10% FBS (Corning) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The cells were then transfected with the expression vectors using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) as previously described84with the modification that the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM at 3 h after transfection. To observe Halo-GRB2 and Halo-PI3K, these probes were labeled with 100 nM HaloTag TMR (Promega) in the culture medium at 37 °C for 15 min, and then washed repeatedly with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Subsequently, the medium was replaced with minimum essential medium (MEM, Nissui) containing 5 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)−1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; pH 7.4; Nacalai Tesque) and 0.1% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA, Wako Pure Chemical Industries).

Cell cycle assay and DNA quantification

For serum starvation, cells were cultured for 24 h in a CO2 incubator with MEM containing 1.5 mg/mL NaHCO3, 0.3 mg/mL L-glutamine, 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA. The changes in the distribution of FBS-released serum-starved cells in each cell cycle phase were analyzed using the Cell-Clock cell cycle assay kit (Biocolor Ltd.). After staining, the cells were photographed using an inverted culture microscope (CK40, Olympus) equipped with a digital camera (CAMEDIA C-3040ZOOM, Olympus). To determine the proportion of cells in each cell cycle phase, images were analyzed using ImageJ. The images were converted to the HSB (Hue, Saturation, Brightness), and the Hue channel was extracted. Mean pixel intensity was measured for each cell. Threshold settings for classifying cells into color tones (yellow, green, and dark blue) were manually adjusted based on visual inspection of the images, with consistency maintained across all analyses.

To identify the cell cycle phase of individual cells immediately after measuring protein translocation dynamics, the DNA content was quantified by staining with cell-permeable DNA fluorescent dye (Vybrant DyeCycle green stain, Invitrogen). After measuring the mean fluorescence intensity per unit nucleus area, the histogram of DNA fluorescence intensities (x) was fitted with the sum of two log-normal functions using Igor Pro 9.05 (WaveMetrics) as

|

Here, µi and σi are the mean and standard deviation of the fluorescence intensities of the dye in the two components (i = 1, 2), respectively. N1 and N-N1 are the respective fractions of the two components. µ1 and σ1 for G0/G1 cells are the global parameters for the histograms obtained for all conditions used in this study. The values of the other parameters change during cell cycle progression. The proportions of G0/G1 and S–G2 phase cells were calculated using the integral value of each log-normal function (Supplementary Table S1). The two populations used for the analysis of translocation dynamics (low- and high-DNA cells) were separated at the intersection of the two distributions.

Fluorescence imaging

Halo-GRB2, Halo-PI3K, or GFP-PAK1 on the plasma membrane and GFP-ERK in the cytoplasm and nucleus were simultaneously measured using a TIRF microscopy system based on an inverted microscope (IX83, Olympus) equipped with a 60×, NA 1.50 oil immersion objective (UPlanApo, Olympus) as previously described85,86. For fluorescence excitation of GFP and TMR, we used a laser diode illuminator (LDI-7, 89 North; 470 and 555 nm) and a dichroic mirror (ZT 405/470/555/640rpc, Chroma Technology). For simultaneous acquisition of the emission signals at the wavelengths of 505–530 nm (GFP) and 560–650 nm (TMR), we used image-splitting optics (WVIEW GEMINI-2 C, Hamamatsu Photonics) equipped with a dichroic mirror (T560lpxr, Chroma Technology) and two emission filters (ET510/40m, Chroma Technology for GFP and ET590/40m, Chroma Technology for TMR). The fluorescence images were acquired using two digital CMOS cameras (ORCA-Flash 4.0 V3, Hamamatsu Photonics) with an exposure time of 100 ms.

The asynchronous cells without serum starvation were observed under the microscope at 25 °C. The cells were stimulated with 16 nM (final concentration) of recombinant murine EGF (PeproTech) or a mixture of 5 nM Rh-EGF (Molecular Probes) and 11 nM unlabeled EGF. To inhibit the kinase activities of PI3K, PAK1, and PDK1, the cells were pretreated with 10 nM or 10 µM GDC-0032 (Cayman Chemical), 10 µM IPA (Tocris Bioscience), and 10 µM MP7 (ChemScene), respectively, for 30 min before EGF stimulation. To inhibit the MEK1/2 activation, cells were pretreated with 1 nM trametinib (ChemScene) in DMSO (final concentration 0.05%) for 1 h before EGF stimulation.

The translocation dynamics of proteins to the plasma membrane and nucleus were observed for 60 min after EGF stimulation by timelapse imaging (1 min intervals). The illumination mode was alternated between total internal reflection and epi using an S-335 Piezo tip/tilt platform (PI) and MetaMorph (Molecular Devices)38. To quantify the relative localization of the proteins, the mean fluorescence intensity per unit area on the basal plasma membrane or nucleus was calculated. The amplitude dynamics of translocation were normalized to the values obtained before stimulation in each cell.

Confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy was performed using a laser scanning microscope (FLUOVIEW FV3000, Olympus) equipped with a 60×, NA 1.35 objective lens (UPlanSApo, Olympus) at 25 °C, with excitation at 488 and 561 nm, and detection at 505–530 nm and 600–670 nm for GFP and TMR, respectively.

Dynamics clustering

Prior to clustering the single-cell time-series of GRB2, PI3K and ERK, the amplitude of each trajectory was normalized to the value measured before stimulation and then divided by the difference between the maximum and minimum values of each trajectory. Hierarchic clustering of these trajectories was performed using the DTW distance and Ward2 linkage method. To validate the clustering results, the average silhouette width and statistical tests for separation into two clusters were used. To perform this procedure, we made an R script using the R packages tsclust, cluster, factoextra, and fpc.

Cell division assay

The translocation dynamics of ERK and consecutive cell divisions after EGF stimulation in asynchronous cells pretreated with or without 1 nM trametinib were monitored by timelapse imaging (10 min intervals) with a TIRF microscope (IX83, Olympus). The cells were maintained at 5% CO2 and 37 °C with a Stage Top incubator (INUG2-ZILCS, TOKAI HIT) under microscopic observation. We performed hierarchic clustering of ERK dynamics for 0–60 min after EGF stimulation. The time of cell division was determined by eye for the cumulative probability plots.

Western blotting

For Western blotting analysis, we used the antibodies for following proteins: GRB2 (610111, BD Biosciences), PI3K (ABS234, Millipore), ERK (4696 S, Cell Signaling Technology [CST]), and β-actin (A5441, Sigma-Aldrich); to evaluate the phosphorylation levels of ERBB1 (pTyr1068, 3777 S, CST), ERBB2 (pTyr1139, ab53290, Abcam), ERBB3 (pTyr1262, AF5817-sp, R&D Systems), ERBB4 (pTyr1162, ab68478, Abcam), RAF (pSer338, 05-538, Millipore), MEK1/2 (pSer217/221, 9121 S, CST), ERK1/2 (pThr202/pTyr204, 9106 S, CST), PI3K p85α (pTyr508, sc-12929-R, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), AKT (pThr308, 9275, CST), and PAK1/2 (Thr423/Thr402, 2601, CST). To compare the phosphorylation levels, we applied two normalization steps. Initially, all experimental data were normalized to the staining intensities of β-actin. Subsequently, the time-series data acquired from the same experiment were normalized to the value at 5 min for serum-starved cells or to the values obtained for cells not exposed to the inhibitors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hiromi Sato for technical assistance, Yukinobu Arata for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript, and Pablo Rodriguez-Viciana and Toshihide Yamashita for providing expression vectors.

Author contributions

R.Y. designed and performed most of the experiments reported. Y.S. provided guidance throughout. R.Y. acquired and analyzed the data. R.Y. and Y.S. wrote the manuscript. Y.S. advised on experiments and manuscript preparation.

Data availability

All relevant data can be found within the article and its supplementary information.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang, Z. Regulation of cell cycle progression by growth Factor-Induced cell signaling. Cells1010.3390/cells10123327 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Jones, S. M. & Kazlauskas, A. Connecting signaling and cell cycle progression in growth factor-stimulated cells. Oncogene19, 5558–5567. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203858 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardee, A. B. A restriction point for control of normal animal cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.71, 1286–1290. 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1286 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberg, R. A. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell81, 323–330. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hitomi, M. & Stacey, D. W. Cellular Ras and Cyclin D1 are required during different cell cycle periods in Cycling NIH 3T3 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol.19, 4623–4632. 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4623 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang, H. W., Chung, M., Kudo, T. & Meyer, T. Competing memories of mitogen and p53 signalling control cell-cycle entry. Nature549, 404–408. 10.1038/nature23880 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Min, M., Rong, Y., Tian, C. & Spencer, S. L. Temporal integration of mitogen history in mother cells controls proliferation of daughter cells. Sci. (New York N Y). 368, 1261–1265. 10.1126/science.aay8241 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meloche, S. & Pouysségur, J. The ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as a master regulator of the G1- to S-phase transition. Oncogene26, 3227–3239. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210414 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunet, A. et al. Nuclear translocation of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for growth factor-induced gene expression and cell cycle entry. EMBO J.18, 664–674. 10.1093/emboj/18.3.664 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouchard, C., Marquardt, J., Bras, A., Medema, R. H. & Eilers, M. Myc-induced proliferation and transformation require Akt-mediated phosphorylation of FoxO proteins. EMBO J.23, 2830–2840. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600279 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caunt, C. J. & McArdle, C. A. ERK phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation: insights from single-cell imaging. Biochem. Soc. Trans.40, 224–229. 10.1042/bst20110662 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sewing, A., Wiseman, B., Lloyd, A. C. & Land, H. High-intensity Raf signal causes cell cycle arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol. Cell. Biol.17, 5588–5597. 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5588 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods, D. et al. Raf-induced proliferation or cell cycle arrest is determined by the level of Raf activity with arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol. Cell. Biol.17, 5598–5611. 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5598 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bottazzi, M. E., Zhu, X., Böhmer, R. M. & Assoian, R. K. Regulation of p21(cip1) expression by growth factors and the extracellular matrix reveals a role for transient ERK activity in G1 phase. J. Cell Biol.146, 1255–1264. 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1255 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang, C. Y., Lee, C. & Kwon, K. S. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2-dependent phosphorylation induces cytoplasmic localization and degradation of p21Cip1. Mol. Cell. Biol.29, 3379–3389. 10.1128/mcb.01758-08 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamemoto, H. et al. Biphasic activation of two mitogen-activated protein kinases during the cell cycle in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem.267, 20293–20297 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambard, J. C., Lefloch, R., Pouysségur, J. & Lenormand, P. ERK implication in cell cycle regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1773, 1299–1310. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.11.010 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh, S., Margolis, S. S. & Kornbluth, S. Phosphorylation of the Cyclin b1 cytoplasmic retention sequence by mitogen-activated protein kinase and Plx. Mol. Cancer Research: MCR. 1, 280–289 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright, J. H. et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase activity is required for the G(2)/M transition of the cell cycle in mammalian fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.96, 11335–11340. 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11335 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts, E. C. et al. Distinct cell cycle timing requirements for extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathways in somatic cell mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol.22, 7226–7241. 10.1128/mcb.22.20.7226-7241.2002 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer, S. L. et al. The proliferation-quiescence decision is controlled by a bifurcation in CDK2 activity at mitotic exit. Cell155, 369–383. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.062 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park, Y. Y., Nam, H. J. & Lee, J. H. Hepatocyte growth factor at S phase induces G2 delay through sustained ERK activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.356, 300–305. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.123 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dangi, S., Chen, F. M. & Shapiro, P. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in G2 phase delays mitotic entry through p21CIP1. Cell Prolif.39, 261–279. 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00388.x (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birtwistle, M. R. et al. Ligand-dependent responses of the erbb signaling network: experimental and modeling analyses. Mol. Syst. Biol.3, 144. 10.1038/msb4100188 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avraham, R. & Yarden, Y. Feedback regulation of EGFR signalling: decision making by early and delayed loops. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.12, 104–117. 10.1038/nrm3048 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos, S. D., Verveer, P. J. & Bastiaens, P. I. Growth factor-induced MAPK network topology shapes Erk response determining PC-12 cell fate. Nat. Cell. Biol.9, 324–330. 10.1038/ncb1543 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egan, S. E. et al. Association of Sos Ras exchange protein with Grb2 is implicated in tyrosine kinase signal transduction and transformation. Nature363, 45–51. 10.1038/363045a0 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiyatkin, A. et al. Scaffolding protein Grb2-associated binder 1 sustains epidermal growth factor-induced mitogenic and survival signaling by multiple positive feedback loops. J. Biol. Chem.281, 19925–19938. 10.1074/jbc.M600482200 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao, S., Jaiswal, R. K., Kolch, W. & Landreth, G. E. Identification of the mechanisms regulating the differential activation of the Mapk cascade by epidermal growth factor and nerve growth factor in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem.276, 18169–18177. 10.1074/jbc.M008870200 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakakuki, T. et al. Topological analysis of MAPK cascade for kinetic erbb signaling. PLoS One. 3, e1782. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001782 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasagawa, S., Ozaki, Y., Fujita, K. & Kuroda, S. Prediction and validation of the distinct dynamics of transient and sustained ERK activation. Nat. Cell. Biol.7, 365–373. 10.1038/ncb1233 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galetic, I., Maira, S. M., Andjelkovic, M. & Hemmings, B. A. Negative regulation of ERK and elk by protein kinase B modulates c-Fos transcription. J. Biol. Chem.278, 4416–4423. 10.1074/jbc.M210578200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aasrum, M., Odegard, J., Sandnes, D. & Christoffersen, T. The involvement of the Docking protein Gab1 in mitogenic signalling induced by EGF and HGF in rat hepatocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1833, 3286–3294. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.10.004 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higuchi, M., Onishi, K., Kikuchi, C. & Gotoh, Y. Scaffolding function of PAK in the PDK1-Akt pathway. Nat. Cell. Biol.10, 1356–1364. 10.1038/ncb1795 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Viciana, P. et al. Role of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase in cell transformation and control of the actin cytoskeleton by Ras. Cell89, 457–467. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80226-3 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toker, A. & Cantley, L. C. Signalling through the lipid products of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase. Nature387, 673–676. 10.1038/42648 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanhaesebroeck, B., Leevers, S. J., Panayotou, G. & Waterfield, M. D. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases: a conserved family of signal transducers. Trends Biochem. Sci.22, 267–272. 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01061-x (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshizawa, R. et al. p52Shc regulates the sustainability of ERK activation in a RAF-independent manner. Mol. Biol. Cell. 32, 1838–1848. 10.1091/mbc.E21-01-0007 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Domvri, K., Darwiche, K., Zarogoulidis, P. & Zarogoulidis, K. Following the crumbs: from tissue samples, to pharmacogenomics, to NSCLC therapy. Translational Lung Cancer Res.2, 256–258. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2012.12.06 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang, Z. B. et al. Combined use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors synergistically inhibits lung cancer with EGFR and KRAS mutations. Oncol. Rep.36, 365–375. 10.3892/or.2016.4770 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King, C. C. et al. p21-activated kinase (PAK1) is phosphorylated and activated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1). J. Biol. Chem.275, 41201–41209. 10.1074/jbc.M006553200 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shankaran, H., Zhang, Y., Tan, Y. & Resat, H. Model-based analysis of HER activation in cells co-expressing EGFR, HER2 and HER3. PLoS Comput. Biol.9, e1003201. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003201 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan, T. L. et al. Differential effector engagement by oncogenic KRAS. Cell. Rep.22, 1889–1902. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.051 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eblen, S. T., Extracellular-Regulated & Kinases Signaling from Ras to ERK substrates to control biological outcomes. Adv. Cancer Res.138, 99–142. 10.1016/bs.acr.2018.02.004 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park, E. R., Eblen, S. T. & Catling, A. D. MEK1 activation by PAK: a novel mechanism. Cell. Signal.19, 1488–1496. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.018 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zang, M., Hayne, C. & Luo, Z. Interaction between active Pak1 and Raf-1 is necessary for phosphorylation and activation of Raf-1. J. Biol. Chem.277, 4395–4405. 10.1074/jbc.M110000200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato, S., Fujita, N. & Tsuruo, T. Involvement of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 in the MEK/MAPK signal transduction pathway. J. Biol. Chem.279, 33759–33767. 10.1074/jbc.M402055200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berlin, R. D., Oliver, J. M. & Walter, R. J. Surface functions during mitosis I: phagocytosis, pinocytosis and mobility of surface-bound Con A. Cell15, 327–341. 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90002-8 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fielding, A. B., Willox, A. K., Okeke, E. & Royle, S. J. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is inhibited during mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.109, 6572–6577. 10.1073/pnas.1117401109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kunduri, G., Acharya, U. & Acharya, J. K. Lipid polarization during cytokinesis. Cells11, 3977. 10.3390/cells11243977 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tacheva-Grigorova, S. K., Santos, A. J., Boucrot, E. & Kirchhausen, T. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis persists during unperturbed mitosis. Cell. Rep.4, 659–668. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.017 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boucrot, E. & Kirchhausen, T. Endosomal recycling controls plasma membrane area during mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.104, 7939–7944. 10.1073/pnas.0702511104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly, K. L., Ruderman, N. B. & Chen, K. S. Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase in isolated rat adipocytes. Activation by insulin and subcellular distribution. J. Biol. Chem.267, 3423–3428 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato, M., Ueda, Y., Takagi, T. & Umezawa, Y. Production of PtdInsP3 at endomembranes is triggered by receptor endocytosis. Nat. Cell. Biol.5, 1016–1022. 10.1038/ncb1054 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thapa, N. et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signalling is spatially organized at endosomal compartments by microtubule-associated protein 4. Nat. Cell. Biol.22, 1357–1370. 10.1038/s41556-020-00596-4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boucrot, E. et al. Endophilin marks and controls a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Nature517, 460–465. 10.1038/nature14067 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sigismund, S. et al. Clathrin-independent endocytosis of ubiquitinated cargos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.102, 2760–2765. 10.1073/pnas.0409817102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lund, K. A., Opresko, L. K., Starbuck, C., Walsh, B. J. & Wiley, H. S. Quantitative analysis of the endocytic system involved in hormone-induced receptor internalization. J. Biol. Chem.265, 15713–15723 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sigismund, S. et al. Clathrin-mediated internalization is essential for sustained EGFR signaling but dispensable for degradation. Dev. Cell.15, 209–219. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.012 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones, M. C., Zha, J. & Humphries, M. J. Connections between the cell cycle, cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci.374, 20180227. 10.1098/rstb.2018.0227 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Assoian, R. K. & Zhu, X. Cell anchorage and the cytoskeleton as partners in growth factor dependent cell cycle progression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol.9, 93–98. 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80157-3 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang, S. & Ingber, D. E. A discrete cell cycle checkpoint in late G(1) that is cytoskeleton-dependent and MAP kinase (Erk)-independent. Exp. Cell Res.275, 255–264. 10.1006/excr.2002.5504 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones, M. C., Askari, J. A., Humphries, J. D. & Humphries, M. J. Cell adhesion is regulated by CDK1 during the cell cycle. J. Cell Biol.217, 3203–3218. 10.1083/jcb.201802088 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parsons, J. T. Focal adhesion kinase: the first ten years. J. Cell. Sci.116, 1409–1416. 10.1242/jcs.00373 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delcommenne, M. et al. Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.95, 11211–11216. 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11211 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deng, S. et al. PI3K/AKT signaling tips the balance of cytoskeletal forces for cancer progression. Cancers (Basel). 14, 1652. 10.3390/cancers14071652 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown, M. C. & Turner, C. E. Paxillin: adapting to change. Physiol. Rev.84, 1315–1339. 10.1152/physrev.00002.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang, Y., Cao, H., Chen, J. & McNiven, M. A. A direct interaction between the large GTPase dynamin-2 and FAK regulates focal adhesion dynamics in response to active Src. Mol. Biol. Cell. 22, 1529–1538. 10.1091/mbc.E10-09-0785 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alharbi, B. F., Al-Fahad, D. & Richard Dash, P. Roles of endocytic processes and early endosomes on focal adhesion dynamics in MDA-MB-231 cells. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biology. 10, 145–155. 10.52547/rbmb.10.2.145 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lajoie, P. et al. Plasma membrane domain organization regulates EGFR signaling in tumor cells. J. Cell Biol.179, 341–356. 10.1083/jcb.200611106 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hiroshima, M. et al. Transient acceleration of epidermal growth factor receptor dynamics produces Higher-Order signaling clusters. J. Mol. Biol.430, 1386–1401. 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.02.018 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goh, L. K., Huang, F., Kim, W., Gygi, S. & Sorkin, A. Multiple mechanisms collectively regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Cell Biol.189, 871–883. 10.1083/jcb.201001008 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goh, L. K. & Sorkin, A. Endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol.5, a017459. 10.1101/cshperspect.a017459 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tarcic, G. et al. EGR1 and the ERK-ERF axis drive mammary cell migration in response to EGF. Faseb J.26, 1582–1592. 10.1096/fj.11-194654 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aoki, K. et al. Propagating wave of ERK activation orients collective cell migration. Dev. Cell.43, 305–317e305. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.10.016 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aikin, T. J., Peterson, A. F., Pokrass, M. J., Clark, H. R. & Regot MAPK activity dynamics regulate non-cell autonomous effects of oncogene expression. eLife910.7554/eLife.60541 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Gagliardi, P. A. et al. Collective erk/akt activity waves orchestrate epithelial homeostasis by driving apoptosis-induced survival. Dev. Cell.56, 1712–1726e1716. 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.05.007 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blanco, R. et al. A gene-alteration profile of human lung cancer cell lines. Hum. Mutat.30, 1199–1206. 10.1002/humu.21028 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tate, J. G. et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res.47, D941–d947. 10.1093/nar/gky1015 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hibino, K., Shibata, T., Yanagida, T. & Sako, Y. Activation kinetics of RAF protein in the ternary complex of RAF, RAS-GTP, and kinase on the plasma membrane of living cells: single-molecule imaging analysis. J. Biol. Chem.286, 36460–36468. 10.1074/jbc.M111.262675 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morimatsu, M. et al. Multiple-state reactions between the epidermal growth factor receptor and Grb2 as observed by using single-molecule analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.104, 18013–18018. 10.1073/pnas.0701330104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takahashi, M., Shibata, T., Yanagida, T. & Sako, Y. A protein switch with tunable steepness reconstructed in Escherichia coli cells with eukaryotic signaling proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.421, 731–735. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.071 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yoshizawa, R., Umeki, N., Yamamoto, A., Murata, M. & Sako, Y. Biphasic Spatiotemporal regulation of GRB2 dynamics by p52SHC for transient RAS activation. Biophys. Physicobiology. 18, 1–12. 10.2142/biophysico.bppb-v18.001 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakamura, Y., Hibino, K., Yanagida, T. & Sako, Y. Switching of the positive feedback for RAS activation by a concerted function of SOS membrane association domains. Biophys. Physicobiology. 13, 1–11. 10.2142/biophysico.13.0_1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yoshizawa, R., Umeki, N., Yanagawa, M., Murata, M. & Sako, Y. Single-molecule fluorescence imaging of RalGDS on cell surfaces during signal transduction from Ras to Ral. Biophys. Physicobiology. 14, 75–84. 10.2142/biophysico.14.0_75 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Imaizumi, T. et al. Assessing transfer entropy from biochemical data. Phys. Rev. E. 105, 034403. 10.1103/PhysRevE.105.034403 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Viaud, J. & Peterson, J. R. An allosteric kinase inhibitor binds the p21-activated kinase autoregulatory domain covalently. Mol. Cancer Ther.8, 2559–2565. 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-09-0102 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data can be found within the article and its supplementary information.