Abstract

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most prevalent malignant tumor in males, and many patients remain at risk of biochemical recurrence (BCR) following initial treatment. Accurate prediction of BCR is vital for effective clinical management and treatment planning. This study evaluates the effectiveness of machine learning (ML) models in predicting BCR among prostate cancer patients, comparing their performance to traditional prognostic methods. We systematically searched four databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane) for studies employing ML techniques to predict prostate cancer BCR. Data extraction included model type, sample size, and the area under the curve (AUC). A meta-analysis was conducted using AUC as the primary performance metric to assess predictive accuracy and heterogeneity across models. Sixteen studies comprising a total of 17,316 prostate cancer patients were included. The pooled AUC for ML models was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.81–0.84). Deep learning and hybrid models outperformed traditional models (AUC = 0.83). Models using imaging data showed improved performance (AUC = 0.82). ML models were most effective in predicting 1-year BCR (AUC = 0.86), with performance slightly decreasing for longer time intervals. ML models outperform traditional methods in predicting BCR, especially in the short term. Incorporating multimodal data, such as imaging, enhances predictive accuracy. Future studies should optimize and validate these models through large-scale clinical trials.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-11445-5.

Subject terms: Oncology, Urology

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most common malignancies in men, with its incidence continually rising worldwide1. It has become the second most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men2.Despite significant advancements in early diagnosis and treatment, many patients still experience biochemical recurrence (BCR) after definitive therapies such as prostatectomy or radiation therapy, marked by a rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels3. BCR often indicates local or distant recurrence of the cancer, adversely affecting patient prognosis and reducing overall survival4,5.

Accurately predicting BCR is important for urologists in their clinical management and treatment planning6. Early recognition of high-risk BCR patients enables the prompt initiation of secondary treatments, which can delay disease progression, control metastasis, and enhance survival rates7. Predicting the BCR of PCa involves multiple factors, such as the patient’s clinical data and tumor characteristics8. Traditional prediction methods mainly rely on laboratory, imaging, and pathological data, using conventional statistical models such as CAPRA nomograms for comprehensive analysis9,10. These traditional methods often rely on single parameters, such as the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) score for MRI-based tumor characterization or shear wave elastography for measuring tissue stiffness. While these methods contribute to predictive accuracy, they suffer from several key limitations11.

The PI-RADS score, for instance, is heavily reliant on the interpretation of MRI images by radiologists, leading to potential subjectivity and inter-reader variability. Additionally, the shear wave elastography technique, while effective in assessing tissue stiffness, cannot fully capture the complex, multi-dimensional nature of prostate cancer and may miss subtle biomarkers indicative of BCR. These traditional approaches also tend to focus on limited, static datasets and may not dynamically adjust to changes in the patient’s condition over time, further limiting their predictive power12. These methods struggle to fully address the high heterogeneity and complexity of PCa, thus constraining their clinical applicability.

With the advancement of technology, the application of ML in disease prediction and diagnosis has become increasingly widespread13,14. Compared to traditional methods, ML can handle more complex data and uncover hidden nonlinear relationships, thereby improving predictive accuracy and stability. In predicting BCR, ML offers distinct advantages, including comprehensive multi-factor analysis, dynamic updates, and automated learning with parameter optimization15,16.

In recent years, numerous studies have explored the use of ML for BCR prediction in prostate cancer, demonstrating its potential in processing diverse data sources and enhancing model stability17,18. The performance of ML models is typically evaluated through cross-validation and external validation, with commonly used metrics including AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity19.

However, the results of different studies vary significantly, and a systematic comprehensive evaluation is lacking. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to thoroughly assess the effectiveness of ML models in predicting BCR in PCa. The results are expected to facilitate their application in prostate cancer management, improving patient treatment outcomes and quality of life.

Methods

Search strategy

Our study’s systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses20. The detailed search strategy and review protocol are available on Prospero (CRD42024553291). We performed a systematic literature search in four databases—PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane using the search strategy: “prostate cancer” AND “machine learning” AND “biochemical recurrence.” Additional terms related to biochemical recurrence include biochemical failure, PSA recurrence, and PSA failure.

Inclusion criteria

We included studies that reported the performance of ML in predicting the BCR of PCa and compared them with traditional models as a reference test. All types of original research (prospective and retrospective) that provided data on the validation, development, and validation of ML were included. Reviews, editorial materials, books, and commentaries were excluded.

After the automatic duplication check, Ling and Yao removed duplicates manually. Subsequently, they conducted a title review, excluding inappropriate publications such as reviews, case reports, editorial materials, books, and commentaries. They also excluded studies that focused on radiomics. This exclusion was based on the fact that the primary focus of this research is on ML models for predicting BCR of PCa, and radiomics-based approaches were outside the scope of this study. Furthermore, studies that employed ML models for predicting non-BCR outcomes or involved other malignancies were also excluded. Ling and Yao independently reviewed abstracts according to the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, eliminating studies that used biomarkers for predicting BCR and those without data or with inaccessible full texts. At this stage, any disagreements led to the inclusion of the article for further full-text review. Finally, Ling and Yao independently performed a full-text review, excluding articles that did not provide AUC data for both ML models and traditional statistical models. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and if consensus could not be reached, Li made the final decision (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Literature screening process.

Data extraction

Data extraction was independently conducted by Ling and Yao. They extracted and tabulated the following information from the articles: the first author, year of publication, treatment modalities such as radical prostatectomy (RP), radiotherapy (RT), and aobot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP), source data for testing the ML models, types of source data, various ML models used (including logistic regression, support vector machine, decision tree, random forest, eXtreme Gradient Boosting, and Neural Network), types of ML models, the sample size of the validation set, and the AUC of the validation set.

Additionally, since 14 out of 16 articles (87.5%) mentioned the time to BCR prediction, we included this data in the table as well. At the end of data extraction, Ling and Yao compared their results and discussed any discrepancies. The scope of ML applications and their AUC in predicting the BCR of PCa was the primary conclusion of the study. Additional results examined how ML models and conventional models performed differently for BCR prediction, as well as the differences between the various ML models.

Each study’s level of evidence was assessed using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine scale, and the risk of bias was evaluated using the QUADAS-2 tool (SI Fig. 1)21,22.

Data synthesis

Due to the variety of metrics used to measure model performance in the field of ML, no single metric can provide a complete picture. AUC, a combined measure of sensitivity and specificity, has become a standard in the field of diagnostic test accuracy. Since all 16 articles reported AUC, we chose it as the primary performance metric. As AUC is restricted to the interval between 0.5 and 1.0, we converted and linearized them to a continuous scale using the logit transformation formula  )23.

)23.

At this stage, we used the chi-squared test and the heterogeneity index I² to assess the statistical heterogeneity of the results included in the meta-analysis. A I² value less than 25% indicates low heterogeneity; an I² between 25% and 75% indicates moderate heterogeneity; and an I² greater than 75% indicates high heterogeneity. Since we anticipated moderate heterogeneity, a random-effects model was applied. Additionally, if high heterogeneity was observed, subgroup analyses were planned.

Meta-analysis methods

We used R and Stata 15 to aggregate the AUCs of all ML models. We tested the generalized point estimates of the effects and their credibility. To visualize the results of this analysis, we employed forest plots and funnel plots. Data processing tools included RevMan 5.3, Stata 15, and R.

Results

Search of study

After the initial search, we collected 1,095 relevant articles. Following screening and quality assessment, 16 articles published between 2007 and 2024 were ultimately included. All studies were prospective or retrospective cohort studies, encompassing data from approximately 17,316 cases of radical treatment for PCa. These studies included data from multiple institutions and countries. Only two articles did not specify the time interval for predicting the BCR of PCa.

Study characteristics

The basic characteristics of these included studies comprised the first author, year of publication, treatment modalities (RP, RT, RARP), source data for training and testing the ML models, types of source data, various ML models used, types of ML models, sample size of the validation set, and the AUC of the validation set.

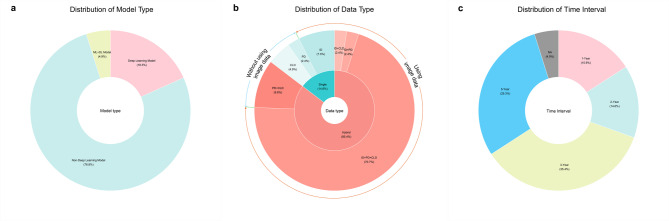

A total of 82 distinct models, spanning 25 different types, These 25 types refer to the different categories or methodologies of models used, such as logistic regression (LR), support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), and others. Each type may have been applied with different datasets, resulting in unique models. Since deep learning models are a subset of ML models24we categorized these 25 model categories into deep learning models, non-deep learning models (traditional ML models), and hybrid models (ML + DL models). Among the 82 included models, there were 15 deep learning models25–30accounting for approximately 18.3% of the total; 63 non-deep learning models26–29,31−40, making up about 76.8% of the total; and 4 hybrid models39,40representing 4.9% of the total (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

(a) The chart shows the prevalence of different model types, with Non-Deep Learning Models at 76.8%, Deep Learning Models at 18.3%, and ML + DL Models at 4.9%. (b) This chart highlights data type usage, with Hybrid data types at 85.4%, Single data types at 14.6%, and a mix of other types. (c) The chart displays time intervals used in the study, with 1-Year at 15.9%, 2-Year at 14.6%, 3-Year at 35.4%, 5-Year at 29.3%, and NA at 4.9%. ID imaging data, CLD clinical data, PD pathological data.

In terms of the source data for the ML models, we categorized the source data used in the included literature into single data and hybrid data. Single data includes clinical laboratory data (CLD), imaging data (ID), and pathological data (PD). Hybrid data refers to the combination of any two or all three types of single data.

Seventy (85.4%) of the 82 models that were included used hybrid data25–35,37−40. Of these, 58 models (70.7%) used a combination of ID + PD + CLD26–30,34,35,37,38,408 models (9.8%) used PD + CLD31,33,39and 2 models (2.4%) used either ID + CLD or ID + PD25,30,32,34. Only 12 models (14.6%) used single data25,30,32,34,36,39with 4 models (4.9%) using clinical laboratory data25,30,32,346 models (7.3%) using imaging data30,32,34,36,39and 2 models (2.4%) using pathological data30,34.

We noticed that a significant portion of the literature reported using imaging data as the source data for predictive models. A total of 68 models (82.9%) used ID25–30,32,34–40with the model in Lee et al. performing the best (AUC = 0.971)25. Only 14 models (17.1%) did not use ID25,30–34,39(Fig. 2-b).

Of the 16 included studies, 14 specified the time intervals for predicting BCR in PCa. Tan et al., Park et al., Wong et al., and Hou et al. mentioned 1-year BCR27,35,37,40; Leo et al., Lee et al., Lu et al., and Hou et al. mentioned 2-year BCR25,31,33,40; Hu et al., Tan et al., Lee et al., Sargos et al., Shiradkar et al., and Hou et al. mentioned 3-year BCR26,28,30,34,35,40; and Bourbonne et al., Tan et al., Lee et al., Cordon-Cardo et al., and Kim et al. conducted studies on 5-year BCR26,29,32,35,38. These studies included 78 different models (95.1%).

The number of predictive models for 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year BCR was 13 (15.9%), 12 (14.6%), 29 (35.4%), and 24 (29.3%). Among all 82 models, only 4 models (4.9%) did not predict the BCR of PCa within a specified time interval36,39(Fig. 2-c).

Thirteen studies focused on patients who underwent radical prostatectomy (RP) for PCa25,27,28,30–36,38,40; three studies reported on robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP)29,35,37; and two studies used radical radiotherapy (RT) as the treatment method25,39. Additionally, three studies compared the ML models with traditional clinical models30,35,40.

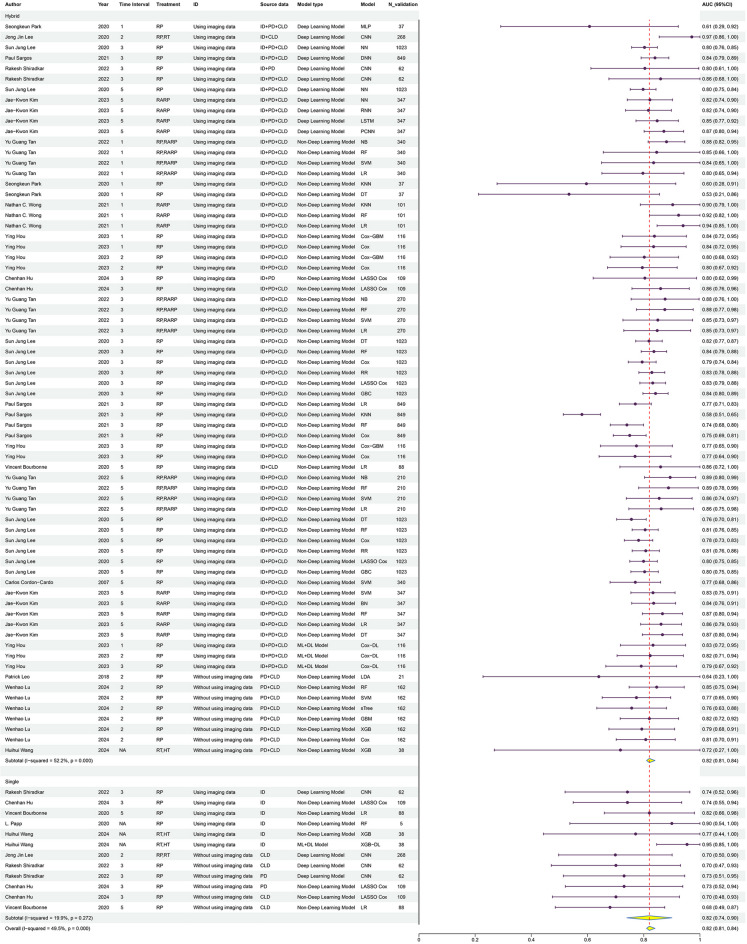

Main results

Our study indicates that ML models exhibit high performance in predicting the BCR of PCa. The meta-analysis revealed a pooled AUC of 0.82 (95% CI 0.81–0.84) with an I² of 49.5% (Fig. 3). The results suggest that ML models are reliable for predicting BCR in PCa. The I² value indicates moderate heterogeneity between studies, enhancing the credibility of the pooled results.

Fig. 3.

This figure shows the predictive performance (AUC) of machine learning models from various studies. The table lists the study details, and the forest plot on the right illustrates the AUC values with 95% confidence intervals.

Subgroup analysis

LR and RF were the most commonly utilized models among the 16 included studies. The pooled effect size for AUC was 0.84 (95% CI 0.79–0.88) for LR and 0.84 (95% CI 0.80–0.87) for RF. Although the number of other models was relatively limited, these also demonstrated good predictive performance (SI Fig. 2).

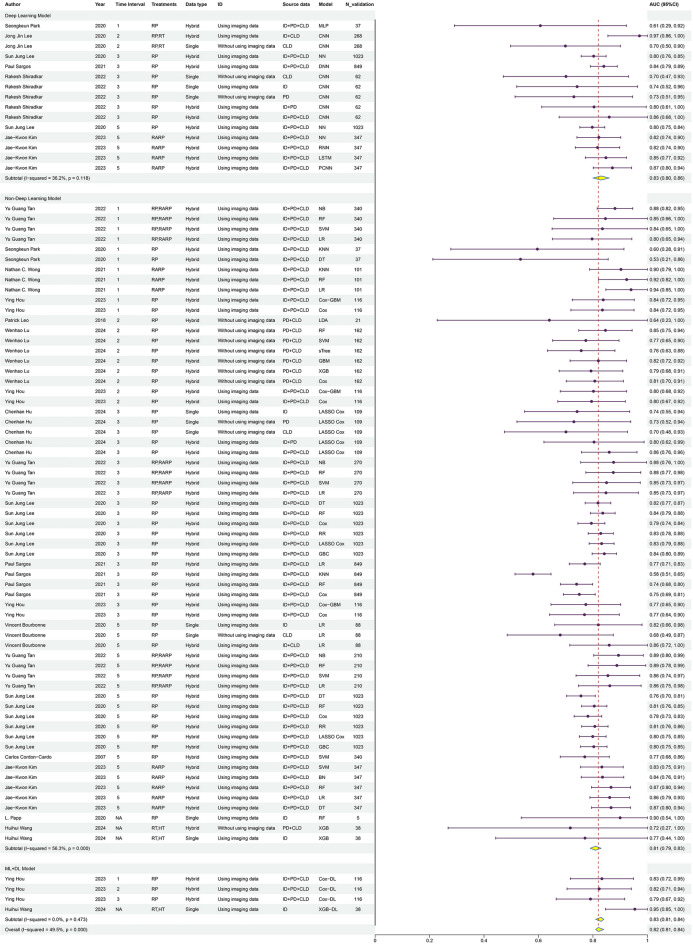

We also analyzed the types of source data (Fig. 4), categorizing them into single data and hybrid data. The pooled AUC for single data and hybrid data were 0.82 (95% CI: 0.74–0.90) and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.81–0.84), respectively. These results suggest that hybrid data models may exhibit more stable predictive performance compared to single data models.

Fig. 4.

This figure shows the summarized area under the curve (AUC) values with 95% confidence intervals for single and hybrid data types across various studies.

Since most studies used imaging data to build their models, we compared models with imaging data to those without it (Fig. 5). The pooled AUC were 0.82 for models with imaging data and 0.78 for those without. The results suggest that models utilizing imaging data may perform better. The higher AUC observed for models with imaging data highlights the potential benefit of imaging data in predicting the BCR of PCa, with the integration of multimodal data possibly enhancing model performance.

Fig. 5.

This figure shows the summarized area under the curve (AUC) values with 95% confidence intervals for studies using imaging data compared to other data types.

We also analyzed the types of ML models (Fig. 6), categorizing them into non-deep learning models, deep learning (DL) models, and ML + DL models. The AUC for the non-deep learning model group was 0.81 (95% CI 0.79–0.83), for the deep learning model group was 0.83 (95% CI 0.80–0.86), and for the ML + DL model group was 0.83 (95% CI 0.81–0.84). These results suggest that deep learning models and ML + DL models may outperform non-deep learning models in predicting BCR.

Fig. 6.

This figure shows the analysis results of the area under the curve (AUC) values with 95% confidence intervals for non-deep learning models, deep learning models, and ML + DL models across various studies.

The elevated AUC for deep learning and ML + DL models could reflect their enhanced ability to identify complex patterns and nonlinear relationships within the data, leading to improved predictive performance. Moreover, ML + DL models may demonstrate more stable performance compared to deep learning models alone.

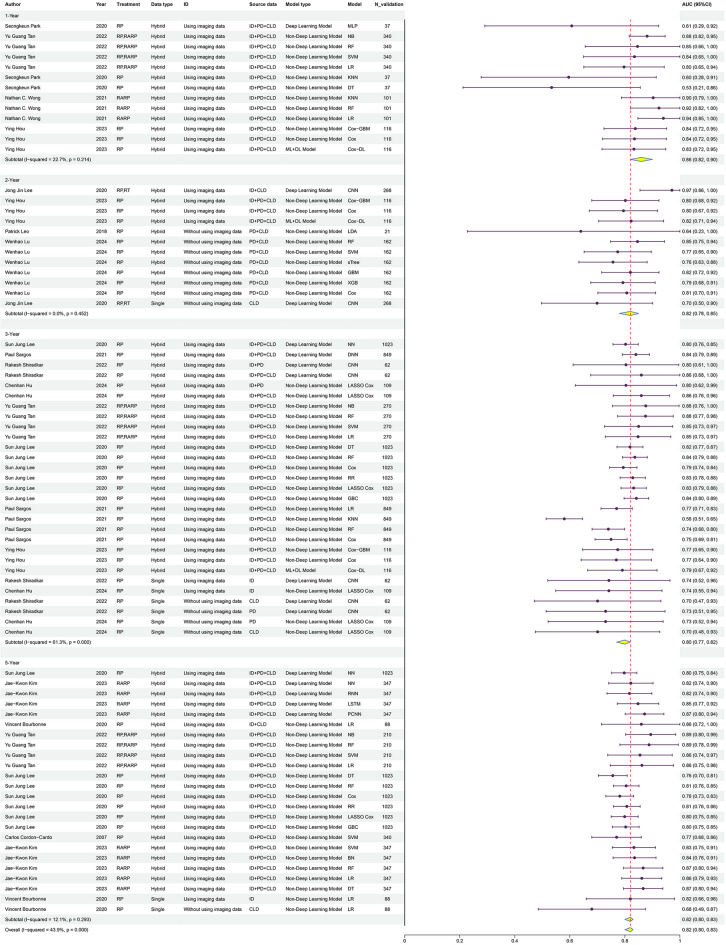

Finally, we conducted a subgroup analysis of the predictive ability of ML models for BCR across different post-treatment time intervals (Fig. 7). The AUC was 0.86 (95% CI 0.82–0.90) for 1-year BCR, 0.82 (95% CI 0.78–0.85) for 2-year BCR, 0.80 (95% CI 0.77–0.82) for 3-year BCR, and 0.82 (95% CI 0.80–0.83) for 5-year BCR. These findings suggest that ML models’ predictive capacity may vary over time, with the 1-year forecast demonstrating the best performance.

Fig. 7.

This figure shows the predictive performance (AUC with 95% CI) of various models across different time intervals (1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year).

Thus, it can be suggested that ML models may be reliable in predicting BCR in PCa, particularly in the short-term (1-year), but caution should be taken in making definitive conclusions regarding long-term prediction without further statistical validation.

In this meta-analysis, we also used a funnel plot to assess for the presence of publication bias. As shown in Fig. 8, the data points in the funnel plot are roughly symmetrically distributed, with most points clustered near the center line, indicating minimal publication bias in this analysis. The majority of the studies fall within the pseudo-95% confidence limits indicated by the dashed lines, suggesting that the effect estimates are consistent with the overall effect. The data points spread outward with increasing standard error, which aligns with the expected shape of a funnel plot, further validating the reliability of the study results.

Fig. 8.

This funnel plot visualizes the distribution of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Our analysis indicates that the impact of publication bias appears minimal, and the overall results show high consistency and reliability.

Noteworthy studies

It is worth mentioning that Lee et al.26Hou et al.40and Tan et al.35 used ML models to predict the BCR of PCa over different time intervals.

Lee et al.26 conducted long-term follow-up validation at 3-year and 5-year post-radical treatment, with AUCs of 0.82 and 0.79. Hou et al.40 reported results for 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year BCR, with AUCs of 0.84, 0.81, and 0.78. In Tan’s study35ML models predicted the BCR of PCa at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year intervals, achieving AUCs of 0.86, 0.86, and 0.88. Their studies all indicate that ML models exhibit high reliability in mid-to-long-term predictions of BCR in PCa.

Hou et al.40 aimed to provide a non-invasive method for predicting BCR by combining MRI data with AI models, reducing the reliance on biopsies. This approach allows patients to receive accurate predictions without undergoing invasive procedures, thereby decreasing the consumption of medical resources and lowering healthcare costs. Additionally, it reduces the risks of infection and complications associated with biopsies, making the patient experience more comfortable.

The study was based on extensive MRI imaging data for model training. Among the studies we included, 14 utilized imaging data for model training25–30,32,34–40. These models consistently demonstrated excellent performance, underscoring the significant role of imaging data in predicting BCR.

They also compared their AI model with nomograms (CAPRA, CAPRA-S) in predicting 5-year BCR. The results showed that the ML model outperformed traditional models in terms of net benefit and predictive performance.

Tan et al.35 compared their ML model with traditional nomograms used clinically to predict prostate BCR. Their model outperformed the nomograms in predicting the BCR of PCa. Shiradkar et al.30 compared their models with CAPRA and CAPRA-S, using deep learning techniques including convolutional neural networks (CNN) and radiomics analysis. They developed single-modality models and multimodality models. The multimodality model achieved an AUC of 0.860 in the test set, significantly higher than CAPRA (AUC = 0.684) and CAPRA-S (AUC = 0.705).

Additionally, they compared their models with CAPRA and CAPRA-S, using deep learning techniques including convolutional neural networks (CNN) and radiomics analysis. They developed single-modality models and multimodality models. The multimodality model achieved an AUC of 0.860 in the test set, significantly higher than CAPRA (AUC = 0.684) and CAPRA-S (AUC = 0.705).

Discussion

Our meta-analysis showed that ML models had good predictive performance in predicting PCa BCR with a pooled AUC of 0.82 (95% CI 0.81–0.84). And the I² value of 49.5% among the included studies suggests moderate heterogeneity, which supports the credibility of the results.

Within the included studies, deep learning models and ML + DL models outperformed non-deep learning models, achieving AUC of 0.83 compared to 0.81 for non-deep learning models. This suggests that more complex and diverse model structures have an advantage in handling patient data, as they can better capture complex patterns and nonlinear relationships within the data, thereby improving predictive performance41. Our data indicates that ML + DL models exhibit more stable performance than deep learning models alone, reflecting the potential superiority of multi-model ensemble approaches in handling large datasets42.

Our analysis further shows models using hybrid data are more stable in performance compared to single data models. It suggests that multimodal data fusion can more comprehensively reflect the clinical characteristics of patients43 The potential of integrating multiple types of source data is demonstrated by significantly improving the models’ predictive capabilities through combining different data types44therefore current research trends towards using hybrid data for predicting BCR.

This study also pointed out that models using imaging data performed better in predicting the BCR of PCa compared to those not using imaging data45. This underscores the critical role of imaging data in BCR prediction. Imaging data provides rich information about disease characteristics, revealing features such as tumor size, location, and its relationship with surrounding anatomical structures to identify potential tumor progression45,46. Combining imaging data with other types of data can form multimodal data fusion, providing more comprehensive information and enhancing the predictive power of the models47. This allows ML models to capture disease characteristics and progression more quickly and thoroughly48.

Meanwhile, we also evaluated the performance of ML in predicting BCR over different time intervals (1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year). The pooled AUC values for these time intervals were 0.86, 0.82, 0.80, and 0.82. These results indicate that ML models are the best at predicting BCR within 1-year. The predictive ability of the models shows some variation across different time intervals. While the AUC values for the 2-year and 3-year intervals are slightly lower, they remain above 0.8, suggesting that the models still demonstrate strong predictive performance. The AUC value for the 5-year interval is 0.82, which is similar to that of the 1-year interval, indicating that the models continue to perform well even for long-term predictions.

Although the predictive ability of ML models varies across different time intervals, they generally demonstrate good predictive performance49,50. Particularly in the short term (1-year). As time progresses, the prediction accuracy of the models decreases somewhat, but it improves again over the longer term (5-year), indicating the stability of ML models in long-term predictions. This further demonstrates their reliable dynamic predictive capabilities51.

Research has shown that ML models outperform traditional nomogram models in predicting the BCR of PCa. In Tan et al.‘s study35the AUCs for ML models were 0.86 or 0.88 at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year intervals, higher than the AUCs of the Kattan, JHH, and CAPSURE nomograms. Hou et al.40 also showed that AI models outperform the D’Amico, CAPRA, and CAPRA-S nomograms in predictive performance. Shiradkar et al.30 further demonstrated that the multimodal models constructed using deep learning techniques achieved an AUC of 0.860, significantly higher than the AUCs of the CAPRA and CAPRA-S models, which were 0.684 and 0.705. Sargos et al.28 also demonstrated that AI models have stronger predictive capabilities for the BCR of PCa compared to traditional CAPRA nomograms.

They applied deep neural networks (DNN) to predict BCR in PCa. Compared to other predictive models such as CAPRA score, LR, k-nearest neighbors (KNN), RF, and Cox regression, the study found that DNN exhibited higher accuracy in predicting 3-year BCR, with an AUC of 0.84, significantly outperforming the other models. This indicates that deep learning models have good potential for complex medical prediction tasks28.

Therefore, by integrating multiple types of source data and adopting complex model structures, predictive performance can be significantly enhanced, providing strong support for clinical decisions52.

In our meta-analysis on ML predictions of BCR in PCa, the results show that ML models exhibit reliable performance in this field, with a pooled AUC of 0.82 (95% CI 0.81–0.84). To further explore the significance of these results, we compared them with the study by Lorent et al.53which thoroughly assessed the performance of the CAPRA nomogram in predicting BCR in PCa, with a pooled AUC of 0.73 (95% CI 0.67–0.79). Evidently, ML models surpass the CAPRA scoring system in terms of predictive performance.

Lorent et al.53 used traditional statistical methods to evaluate the predictive ability and calibration of the CAPRA scoring system. They found that although the CAPRA nomogram performed well in terms of calibration and discrimination, its application showed certain limitations across different patient populations. Lorent et al.53 further explored the clinical utility of the CAPRA nomogram and found that its practicality in stratified medical decision-making was limited.

In contrast, ML models have the potential to assist clinicians in formulating more personalized treatment plans through more accurate predictions, thereby improving patient prognosis and quality of life. Because ML models possess strong adaptability and data processing capabilities, they excel at handling large-scale and complex data and demonstrate good generalization across different clinical settings54.

These findings have important implications for the clinical practice of urology. Efficient modern ML models can help clinicians more accurately predict the BCR of PCa, thereby improving patient prognosis.

Limitation

Despite the promising results, there are several limitations to this analysis. The heterogeneity between studies, including differences in patient populations and model types, may affect the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, most of the studies relied on retrospective data, which could introduce biases. The potential overfitting of deep learning models and the lack of standardization in data collection across studies are other factors that may limit the applicability of these models in clinical practice.

Outlook

With the increasing application of ML in clinical settings, research has confirmed its effectiveness and reliability in medical predictions55. Specifically, in low- and middle-income countries, ML models have the potential to provide cost-effective and timely predictions by integrating existing clinical data, reducing the need for expensive or invasive procedures, lowering patient risks, and overall healthcare costs. In these settings, ML can serve as an important tool for early diagnosis and treatment planning. Moreover, ML can guide clinicians by offering real-time predictions and recommendations, assisting them in making more accurate, personalized treatment decisions. However, the integration of AI into clinical practice also presents challenges, such as data quality, algorithm transparency, and the need for clinician training. AI should complement, not replace, clinical expertise. Future research should focus on optimizing these models to ensure their effective implementation in diverse healthcare environments.

Future research should optimize and validate these models and develop multimodal models that integrate various types of data. More advanced models can better understand the complexity of PCa recurrence, provide more accurate predictions, and aid in the early detection of disease progression. Non-invasive prediction methods help reduce the risk of infection, consumption of materials, and patient expenses, as well as alleviate patient suffering. Promoting and validating the effectiveness of these methods will improve healthcare efficiency and patient experience40. Moreover, as more data becomes available in the future, such as PSMA-PET/CT, ML can integrate this additional information, which will further enhance its predictive performance. Existing prediction methods should be updated to integrate multimodal data and ML techniques. The effectiveness and stability of new models should also be validated through multicenter clinical trials to enhance clinical trust56.Advancing the application of ML in PCa prediction involves optimizing models and integrating multimodal data. This approach can provide precise, personalized healthcare, improving prognosis and quality of life57.We believe that as technology and clinical practice advance, ML will play an increasingly significant role in precision medicine and personalized treatment.

Conclusion

Our research highlights the promising performance and reliability of ML models in predicting the BCR of PCa. However, further large-scale prospective clinical validation is needed to confirm these findings. Future studies should focus on optimizing and validating these models. In doing so, existing prediction tools may be refined, or more robust models could be developed, ultimately advancing healthcare and improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments for the support and editing of the content of this manu-script to Dr. Yujie wang, Ph.D, and Dr. Hengqing An, Ph.D.

Author contributions

All the authors contribute to the data collection, analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Ling and Tao: Analysis of the data and writing of the manuscript. An: Data management, data preparation, and statistical analysis. Yao and Zhang: Data collection, data preparation for analysis, and manuscript editing. AM and Pu: Writing and editing of the manuscript. Li and Wang: Study design, data collection, oversee data quality, analysis, and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82360476]. The Key Projects of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region [grant number 2022D01D39]. The Regional Collaborative Innovation Special Project of the Autonomous Region, Science and Technology Support Program for Xinjiang [grant number 2024E02054]. The Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region [grant number 2022D01C782].

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. Any additional data related to this study is available on request from the corresponding author. The data of this study has been stored for future reference and available upon reques.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

We agree to the publication of our research paper by the publisher.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors have contributed equally: Chenyang Ling and Ning Tao.

Contributor Information

Xiaodong Li, Email: 371099077@qq.com.

Yujie Wang, Email: 2338408282@qq.com.

Hengqing An, Email: 13201226586@163.com.

References

- 1.Bergengren, O. et al. Update on Prostate Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors-A Systematic Review. Eur Urol 84, 191–206, (2022). 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.021 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.74, 229–263. 10.3322/caac.21834 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budäus, L. et al. Defining biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy and timing of early salvage radiotherapy: informing the debate. Strahlenther Onkol. 193, 692–699. 10.1007/s00066-017-1140-y (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon, N. I., Parker, C., Hope, T. A. & Paller, C. J. Best approaches and updates for prostate Cancer biochemical recurrence. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book.42, 1–8. 10.1200/edbk_351033 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin, X. et al. Assessment of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. Int. J. Oncol.55, 1194–1212 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van den Broeck, T. et al. Biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer: the European association of urology prostate Cancer guidelines panel recommendations. Eur. Urol. Focus. 6, 231–234. 10.1016/j.euf.2019.06.004 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreno-Olmedo, E. et al. Prostate cancer: management of biochemical recurrence after surgery. Arch. Esp. Urol.76, 733–745. 10.56434/j.arch.esp.urol.20237610.89 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenkrantz, A. B. et al. Prostate cancer: utility of whole-lesion apparent diffusion coefficient metrics for prediction of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Am. J. Roentgenol.205, 1208–1214 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooperberg, M. R., Hilton, J. F. & Carroll, P. R. The CAPRA-S score: a straightforward tool for improved prediction of outcomes after radical prostatectomy. Cancer117, 5039–5046 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brajtbord, J. S., Leapman, M. S. & Cooperberg, M. R. The CAPRA score at 10 years: contemporary perspectives and analysis of supporting studies. Eur. Urol.71, 705–709 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padhani, A. R. et al. PI-RADS steering committee: the PI-RADS multiparametric MRI and MRI-directed biopsy pathway. Radiology292, 464–474 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockman, J. A. et al. Nomogram predicting prostate cancer–specific mortality for men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol.67, 1160–1167 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahiwade, D., Patle, G. & Meshram, E. in 3rd International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC). 1211–1215 (IEEE). 1211–1215 (IEEE). (2019).

- 14.Asif, S. et al. Advancements and prospects of machine learning in medical diagnostics: unveiling the future of diagnostic precision. Archives Comput. Methods Engineering, 1–31 (2024).

- 15.Kohli, P. S. & Arora, S. in 2018 4th International conference on computing communication and automation (ICCCA). 1–4 (IEEE).

- 16.Gupta, A. et al. Potential of AI and ML in oncology research including diagnosis, treatment and future directions: A comprehensive prospective. Comput. Biol. Med.189, 109918. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2025.109918 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, S. J. et al. Prediction system for prostate cancer recurrence using machine learning. Appl. Sci.10, 1333 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekşi, M. et al. Machine learning algorithms can more efficiently predict biochemical recurrence after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Prostate81, 913–920 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleiman, R. & Page, D. in International Conference on Machine Learning. 3439–3447 (PMLR).

- 20.Liberati, A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol.62, e1–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rousseau, D. M. The Oxford Handbook of evidence-based Management (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- 22.Whiting, P. F. et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med.155, 529–536 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrio, I., Arostegui, I., Rodríguez-Álvarez, M. X. & Quintana J.-M. A new approach to categorising continuous variables in prediction models: proposal and validation. Stat. Methods Med. Res.26, 2586–2602 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dargan, S., Kumar, M., Ayyagari, M. R. & Kumar, G. A survey of deep learning and its applications: a new paradigm to machine learning. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng.27, 1071–1092 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, J. J., Yang, H., Franc, B. L., Iagaru, A. & Davidzon, G. A. Deep learning detection of prostate cancer recurrence with (18)F-FACBC (fluciclovine, Axumin®) positron emission tomography. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 47, 2992–2997. 10.1007/s00259-020-04912-w (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, S. J. et al. Prediction system for prostate Cancer recurrence using machine learning. Appl. Sciences-Basel. 1010.3390/app10041333 (2020).

- 27.Park, S., Byun, J. & Woo, J. Y. A machine learning approach to predict an early biochemical recurrence after a radical prostatectomy. Appl. Sciences-Basel. 1010.3390/app10113854 (2020).

- 28.Sargos, P. et al. Deep neural networks outperform the CAPRA score in predicting biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy. Front. Oncol.1010.3389/fonc.2020.607923 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kim, J. K., Hong, S. H. & Choi, I. Y. Partial correlation analysis and Neural-Network-Based prediction model for biochemical recurrence of prostate Cancer after radical prostatectomy. Appl. Sciences-Basel. 1310.3390/app13020891 (2023).

- 30.Shiradkar, R. et al. Prostate surface distension and tumor texture descriptors from Pre-Treatment MRI are associated with biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy: preliminary findings. Front. Oncol.1210.3389/fonc.2022.841801 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Leo, P. et al. in SPIE Medical Imaging Symposium / 6th Digital Pathology Conference. (2018).

- 32.Bourbonne, V. et al. External validation of an MRI-Derived radiomics model to predict biochemical recurrence after surgery for High-Risk prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 1210.3390/cancers12040814 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Lu, W. H. et al. Explainable and visualizable machine learning models to predict biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. Clin. Translational Oncol.10.1007/s12094-024-03480-x (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu, C. et al. Development and validation of a multimodality model based on Whole-Slide imaging and biparametric MRI for predicting postoperative biochemical recurrence in prostate Cancer. Radiol. Imaging Cancer. 6, e230143. 10.1148/rycan.230143 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan, Y. G. et al. Incorporating artificial intelligence in urology: supervised machine learning algorithms demonstrate comparative advantage over nomograms in predicting biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy. Prostate82, 298–305. 10.1002/pros.24272 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papp, L. et al. Supervised machine learning enables non-invasive lesion characterization in primary prostate cancer with [(68)Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 PET/MRI. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 48, 1795–1805. 10.1007/s00259-020-05140-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong, N. C., Lam, C., Patterson, L. & Shayegan, B. Use of machine learning to predict early biochemical recurrence after robot-assisted prostatectomy. BJU Int.123, 51–57. 10.1111/bju.14477 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cordon-Cardo, C. et al. Improved prediction of prostate cancer recurrence through systems pathology. J. Clin. Invest.117, 1876–1883. 10.1172/jci31399 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, H. et al. Deep learning-based radiomics model from pretreatment ADC to predict biochemical recurrence in advanced prostate cancer. Front. Oncol.14, 1342104. 10.3389/fonc.2024.1342104 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou, Y. et al. Biopsy-free AI-aided precision MRI assessment in prediction of prostate cancer biochemical recurrence. Br. J. Cancer. 129, 1625–1633. 10.1038/s41416-023-02441-5 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang, L. Y. et al. Health system-scale Language models are all-purpose prediction engines. Nature619, 357–362. 10.1038/s41586-023-06160-y (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng, S. et al. Multi-Modal graph learning for disease prediction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 41, 2207–2216. 10.1109/tmi.2022.3159264 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sousa, J. V. et al. Single modality vs. Multimodality: what works best for lung Cancer screening?? Sens. (Basel). 2310.3390/s23125597 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Jin, W., Dong, S., Yu, C. & Luo, Q. A data-driven hybrid ensemble AI model for COVID-19 infection forecast using multiple neural networks and reinforced learning. Comput. Biol. Med.146, 105560. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105560 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujimoto, A. et al. Tumor localization by prostate imaging and reporting and data system (PI-RADS) version 2.1 predicts prognosis of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Sci. Rep.13, 10079. 10.1038/s41598-023-36685-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hosny, A., Parmar, C., Quackenbush, J., Schwartz, L. H. & Aerts, H. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 18, 500–510. 10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou, S. et al. Deep radiomics-based fusion model for prediction of bevacizumab treatment response and outcome in patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases: a multicentre cohort study. EClinicalMedicine65, 102271. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102271 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao, J. et al. Radiomic and clinical data integration using machine learning predict the efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibodies-based combinational treatment in advanced breast cancer: a multicentered study. J. Immunother Cancer. 1110.1136/jitc-2022-006514 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Parmezan, A. R. S., Souza, V. M. & Batista, G. E. Evaluation of statistical and machine learning models for time series prediction: identifying the state-of-the-art and the best conditions for the use of each model. Inf. Sci.484, 302–337 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyer, A. et al. Machine learning for real-time prediction of complications in critical care: a retrospective study. Lancet Respiratory Med.6, 905–914 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qureshi, K. N., Din, S., Jeon, G. & Piccialli, F. An accurate and dynamic predictive model for a smart M-Health system using machine learning. Inf. Sci.538, 486–502 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, L. et al. Predicting MiRNA-disease associations by multiple meta-paths fusion graph embedding model. BMC Bioinform.21, 470. 10.1186/s12859-020-03765-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lorent, M. et al. Meta-analysis of predictive models to assess the clinical validity and utility for patient-centered medical decision making: application to the CAncer of the prostate risk assessment (CAPRA). BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak.19, 2. 10.1186/s12911-018-0727-2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shafique, M. et al. in 2017 IEEE Computer society annual symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI). 627–632 (IEEE).

- 55.Sun, H. et al. Machine learning–based prediction models for different clinical risks in different hospitals: evaluation of live performance. J. Med. Internet. Res.24, e34295 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siontis, G. C. et al. Development and validation pathways of artificial intelligence tools evaluated in randomised clinical trials. BMJ Health & Care Informatics28 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Lee, S. W. et al. Multi-center validation of machine learning model for preoperative prediction of postoperative mortality. Npj Digit. Med.5, 91 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. Any additional data related to this study is available on request from the corresponding author. The data of this study has been stored for future reference and available upon reques.