Abstract

Introduction

Globally, tobacco use causes 8.7 million deaths annually. Approximately 50 % of formerly homeless adults in permanent supportive housing (PSH) in the United States smoke cigarettes. Secondhand smoke exposure is high in the absence of smoke-free policies. There is a need to understand attitudes toward smoke-free policies and factors associated with smoke-free home adoption attempts among PSH residents.

Methods

Between 2022 and 2024, we recruited 400 PSH residents who smoked into a smoke-free home intervention trial in 40 multi-unit PSH sites. Using baseline data, we applied generalized linear mixed models to examine factors associated with past 3-month smoke-free home adoption attempts, adjusting for age, gender, and race-ethnicity.

Results

Median age was 56 years (IQR 46, 62), and 41.8 % were Black/African American. Of the sample, 34.8 % previously attempted to adopt a smoke-free home, daily cigarette consumption averaged 11.1 (SD 7.5), and 19.3 % used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. E-cigarette use (AOR 2.92, 95 % CI 1.48, 5.77) and positive attitudes toward smoke-free policies (AOR 2.13, 95 % CI 1.43, 3.18) were associated with increased odds of smoke-free home adoption attempts. Longer tenure at current residence (AOR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.89, 0.99), smoking within 5 min of waking (AOR 0.55, 95 % CI 0.31, 0.97), and having a serious mental illness (AOR 0.51, 95 % CI 0.30, 0.88) were associated with lower odds.

Conclusions

Support for smoke-free policies among PSH residents can be strengthened by promoting access to tobacco treatment, addressing the role of e-cigarette use, and providing tailored support for residents with serious mental illness.

Keywords: Permanent Supportive Housing, Smoke-free Home Adoption, Secondhand Smoke Exposure, Smoke-Free Policies, Cessation, Homelessness

Highlights

-

•

One-third of resident participants made smoke-free home adoption attempts.

-

•

Found substantial support for smoke-free policies among participants.

-

•

Having a serious mental illness decreased smoke-free home adoption attempts.

-

•

Higher tobacco dependence decreased the odds of smoke-free home adoption attempts.

-

•

Past 30-day e-cigarette use increased the odds of smoke-free home adoption attempts.

1. Introduction

Tobacco use and secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure cause approximately 8.7 million deaths globally each year, with the highest mortality rates in low- and middle-sociodemographic index countries (He et al., 2022). In the United States (US), tobacco use causes over 490,000 deaths annually, including 19,000 attributable to secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024), with low-income populations and those with mental health and substance use disorders disproportionately impacted (Tsai et al., 2018). These groups are overrepresented among the 400,000 U.S. adults living in permanent supportive housing (PSH), a type of subsidized housing that provides voluntary supportive services for formerly homeless individuals (The 2023 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, 2023; Tsemberis et al., 2004). Among residents of project-based PSH (multi-unit PSH housing developments where services and housing are co-located), smoking prevalence is 50 %-60 %, and tobacco-related diseases are the leading cause of death (Hawes et al., 2020; Henwood et al., 2015, Petersen et al., 2018).

Comprehensive smoke-free policies in the US are associated with reduced exposure to SHS and nicotine aerosols (e.g., e-cigarettes), increased cessation, and improved tobacco-related health outcomes (Hahn et al., 2018, Lightwood and Glantz, 2009, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2009). However, disparities in access to smoke-free policies persist, with racial and ethnic minorities and people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds less likely to have access to smoke-free policies (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024). In 2018, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) implemented smoke-free policies in public housing authority housing (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015), but the majority of subsidized housing, including multi-unit project-based PSH, lacks such policies (Vijayaraghavan and King, 2020). People living in multi-unit housing are particularly susceptible to SHS exposure where smoke can infiltrate living and shared spaces (Homa et al., 2015).

Smoke-free policies are uncommon in PSH because there is concern among PSH providers that smoke-free policies could increase homelessness if residents leave their housing because of the policy, receive a threat of eviction, or are evicted due to a violation of smoke-free policies (Vijayaraghavan and King, 2020). However, increasing access to smoke-free environments is critical to reducing the high burden of tobacco use among PSH residents.

Resident-supported approaches that promote the voluntary adoption of smoke-free homes (i.e., voluntary no-smoking rule in one’s home) may address the gap in access to smoke-free living environments and improve the implementation of smoke-free policies in PSH (Durazo et al., 2021). Such approaches provide information to residents about the impact of SHS exposure on their community, the benefits of creating a smoke-free home, and practical guidance on how to make their homes smoke-free (Durazo et al., 2021, Kegler et al., 2015). Resident-supported approaches are self-enforced, which increases buy-in and adherence to smoke-free policies while mitigating the threat of eviction (Petersen et al., 2020).

However, the emerging landscape of tobacco and nicotine products may pose further challenges to reducing indoor exposure to SHS and nicotine aerosols. People who currently use e-cigarettes may have less favorable attitudes toward smoke-free policies (Patel et al., 2022), may view e-cigarettes as less harmful and more socially acceptable than combustible tobacco, and use them as a replacement for smoking cigarettes indoors (Bandi et al., 2023). Dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes is harmful, and evidence suggests that people who use both cigarettes and e-cigarettes are more likely to use e-cigarettes in smoke-free environments compared to people who exclusively use e-cigarettes (Bandi et al., 2023, Glantz et al., 2024).

We are conducting a waitlist cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) in San Francisco Bay Area PSH sites to examine the efficacy of a resident-supported intervention to increase voluntary adoption of smoke-free homes. This manuscript uses baseline data from the RCT to describe participant characteristics, examine attitudes toward smoke-free policies, and identify factors associated with pre-intervention attempts to adopt a smoke-free home in the past 3 months. We hypothesized that positive attitudes toward smoke-free policies would be associated with greater odds of smoke-free home adoption attempts, whereas higher levels of nicotine dependence would be associated with lower odds. Findings from this analysis can help identify factors that influence smoke-free home adoption and inform the interpretation of the RCT’s efficacy results, exploratory analyses, and future studies.

2. Methods

The present study utilizes baseline data from participants recruited into a cluster RCT of a smoke-free home intervention in PSH for formerly homeless adults. The study protocol has been published (Odes et al., 2022), and the trial is registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04855357). The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved and monitored all study procedures (IRB # 20–33214), and all participants provided signed informed consent upon enrollment.

2.1. Study design

Between January 2022 and February 2024, we recruited 400 participants from 40 project-based PSH sites in the San Francisco Bay Area. All but six sites lacked indoor smoking policies, and the six with policies did not enforce them. Eligibility criteria were: (a) residence at a study site, (b) age 18 or older, (c) English-speaking, (d) ability to provide informed consent, (e) current cigarette use (at least five cigarettes per day in the past 7 days, verified by expired carbon monoxide,8 ppm) (Benowitz et al., 2002), and (f) smoking cigarettes in their home.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographics and residential history

Participants reported their age, gender identity (male, female, transgender, non-binary), and race and ethnicity (Black/African American, White, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan Native, multiracial). We assessed residential history by asking about the length of time at their current residence and where they lived before their current residence (emergency shelter, transitional housing, institution, a place not designed to live in, housing sharing with others, rented housing, or PSH). We assessed their history of homelessness by asking about the total length of time spent homeless during their lifetime.

2.2.2. Mental health and substance use

We screened for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms using the Primary Care-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Screen (PC-PTSD-5), applying a cut-off score of 4 to determine a positive screen (Bovin et al., 2021). We measured anxiety with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), categorized as minimal (score 0–4), mild (score 5–9), moderate (score 10–14), or severe (score 15–21) (Spitzer et al., 2006). We used the Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) to screen for depression (cut point = 10) (Andresen et al., 1994). We assessed psychological distress using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), with scores < 20 indicating little or no distress, 20–24 mild levels of distress, 25–29 moderate levels of distress, and 30 severe levels of distress. (Kessler et al., 2002). We defined having a mental health condition as screening positive on at least one of the following: CES-D-10, GAD-7 (moderate or severe), or PC-PTSD-5. We defined serious mental illness as self-reported schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder. We assessed community-level stressors using the 21-item Urban Life Stressors Scale (ULSS), where higher scores indicate greater levels of stress (Jaffee et al., 2005). We report past 30-day substance use, including the number of days participants used opioids, amphetamines, cocaine, and cannabis. We used the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test (CUDIT) to assess for problematic cannabis use (score 8) (Adamson and Sellman, 2003). We measured risky alcohol use with the AUDIT-C (4 for male and 3 for non-male participants) (Bradley et al., 2007).

2.2.3. Tobacco and nicotine product use

Participants reported their average daily cigarette consumption and time to first cigarette after waking ( min, 6–30 min, 31–60 min, 60 min). We asked participants about their intentions to quit smoking, whether they were advised to quit by healthcare providers, and whether they made a quit attempt in the past year (Al-Delaimy et al., 2015). For those who reported a past-year quit attempt, we asked about their use of any cessation aids (pharmacotherapy, counseling), or not using aids to quit (“quitting cold turkey” or cutting down to quit) (Al-Delaimy et al., 2015). We asked participants to report past 30-day use of e-cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, hookah, and blunts (i.e., cigars or cigar wrappers partly or completely filled with cannabis), and the number of days each was used (Schauer et al., 2020). We estimated the proportion of participants who used each of these products daily in the past 30 days. Among participants who used e-cigarettes, we explored motivations for e-cigarette use, the concentration of nicotine usually used in their e-cigarettes, and ways that they used their e-cigarettes (continuously throughout the day, in distinct bouts shorter than smoking cigarettes, and distinct bouts similar to smoking cigarettes). We asked participants how many times they used their e-cigarettes throughout the day, defining one use as 15 puffs or a session lasting around 10 min.

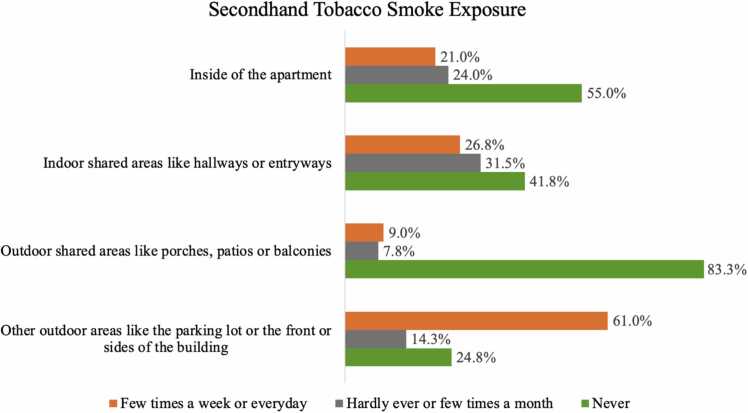

2.2.4. Secondhand smoke exposure and attitudes towards smoke-free policies

We asked participants to report how frequently in the past month they smelled or breathed tobacco smoke in indoor and outdoor areas of their housing site, including inside of their apartment, indoor shared areas like hallways, outdoor shared areas like porches, and other outdoor areas such as parking lots and in front of the building (Odes et al., 2022, Petersen et al., 2020). We categorized response options as (1) a few times per week or every day, (2) hardly ever or a few times a month, or (3) never (Fig. 1). We assessed attitudes toward a hypothetical indoor tobacco smoke-free policy by asking participants whether they would (1) support the policy, (2) try to cut down, (3) try to stop smoking, (4) continue smoking indoors, and (5) move out because of the policy. Response options ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). We created a composite score by averaging responses to all five items (Cronbach’s α = 0.72); higher scores indicated more favorable attitudes (Durazo et al., 2021, Petersen et al., 2018, Petersen et al., 2020, Vijayaraghavan and Pierce, 2015).

Fig. 1.

Locations where participants said they were most exposed to secondhand smoke (N = 400).

2.2.5. Current smoke-free home rules

We recorded participants’ current rules around smoking cigarettes in their homes (e.g., no rules around smoking, smoking is not allowed) and whether they tried to establish a smoke-free home rule within the 3 months prior to enrollment (Odes et al., 2022). We assessed their current intentions to make their home smoke-free (Petersen et al., 2020).

We defined the primary outcome as a binary indicator of “smoke-free home adoption attempts” in the three months prior to enrollment, including those who either reported an attempt to establish a smoke-free home rule (i.e., no smoking at any time in any part of the home) or refrained from smoking cigarettes in their home, even for one day.

2.3. Analysis

We report sample descriptive statistics using the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, or median and interquartile range for variables with a skewed distribution, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables for the overall sample and by smoke-free home status. We examined the characteristics of participants who used e-cigarettes, given the high prevalence of dual use in this sample and the possible association between e-cigarette use and attitudes toward smoke-free policies (Bandi et al., 2023).

We used generalized linear mixed models with a random intercept to account for clustering by PSH sites. We examined the association between smoke-free home adoption attempts (binary outcome) and the following independent variables: length of stay at current residence, mean cigarettes smoked per day (CPD), time to first cigarette after waking, past 30-day e-cigarette use, attitudes towards a smoke-free policy, intention to quit smoking, serious mental illness, illicit drug use, and cannabis use. These variables have been shown to be associated with smoke-free home adoption in prior research (Durazo et al., 2021, Odes et al., 2022). Smoke-free home adoption is more common in households with minor children; however, we did not include this variable in our model because of a low occurrence (N = 1) in our sample (Licht et al., 2012). We adjusted for age, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in the multivariable model and used Stata 17.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX) for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographics and residential history

Among the 400 participants, median age was 56 years (IQR = 46, 62), 62.8 % were male, and 41.8 % Black or African American (Table 1). The median length of time living at their current residence was 3 years (IQR = 1, 8), and participants who made a smoke-free home adoption attempt at baseline had a shorter length of stay in their residence compared to those who did not make an attempt. Before being housed in their current residence, 31 % of participants stayed in transitional housing (e.g., motel, single room occupancy housing), 21 % slept in an emergency shelter, and 18.8 % lived in a place not designed for living (e.g., car, street). The median years spent homeless in their lifetime was 7 (IQR = 2, 15).

Table 1.

Bivariate Analyses of Factors Associated with Smoke-free Home Adoption Attemptsa Among Participants in the Smoke-Free Home Study.

| Smoke-Free Home Attempt |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data | Total | No | Yes | P |

| Enrolled participants | 400 | 261 (65.25) | 139 (34.8) | |

| Age (median, IQR) | 56 (46, 62) | 57 (46, 63) | 56 (46, 62) | 0.569 |

| Genderb (N, %) | ||||

| Male | 251 (62.8) | 162 (62.1) | 89 (64.0) | 0.194 |

| Female | 130 (32.5) | 89 (34.1) | 41 (29.5) | |

| Transgender or non-binary | 17 (4.3) | 10 (3.8) | 7 (5.0) | |

| Race/ethnicityb (N, %) | ||||

| Black or African American | 167 (41.8) | 113 (43.3) | 54 (38.8) | 0.468 |

| White | 100 (25.0) | 69 (26.4) | 31 (22.3) | |

| More than one race | 48 (12.0) | 28 (10.7) | 20 (14.4) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 62 (15.5) | 36 (13.8) | 26 (18.7) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 10 (2.5) | 8 (3.1) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Asian | 4 (1.0) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Housing and homelessness | ||||

| Years of homelessness (lifetime) (median, IQR) | 7 (2, 15) | 10 (3, 17) | 5 (2, 10.8) | 0.003 |

| Previous place of stay (N, %) | ||||

| Emergency shelter or safe haven | 84 (21.0) | 62 (23.8) | 22 (15.9) | 0.508 |

| Transitional housing (transitional, hotel/motel, SRO) | 124 (31.0) | 78 (29.9) | 46 (33.3) | |

| Institution (e.g., hospital, jail, nursing home) | 16 (4.0) | 10 (3.8) | 6 (4.3) | |

| Place not designed to live within (e.g., car, unsheltered on the street) |

75 (18.8) | 46 (17.6) | 29 (21.0) | |

| In housing you shared with others, but did not own or rent |

35 (8.8) | 21 (8.0) | 14 (10.1) | |

| Housing that you rented | 34 (8.5) | 21 (8.0) | 13 (9.4) | |

| Permanent supportive housing | 31 (7.8) | 23 (8.8) | 8 (5.8) | |

| Length of time in current residence (years) (median, IQR) | 3 (1, 8) | 4 (2, 8.5) | 3 (1, 7) | 0.006 |

| Mental health characteristics (means and proportions) | ||||

| Self-reported serious mental illnessc (N, %) | 155 (38.8) | 113 (43.5) | 42 (30.2) | 0.010 |

| Any mental health conditiond (N, %) | 266 (66.5) | 170 (65.4) | 96 (69.1) | 0.457 |

| Depression (CES-D 10)e (N, %) | 222 (55.5) | 148 (56.9) | 74 (53.2) | 0.480 |

| Anxiety - GAD−7f (N, %) | ||||

| Minimal | 135 (33.8) | 85 (32.7) | 50 (36.0) | 0.912 |

| Mild | 95 (23.8) | 62 (23.8) | 33 (23.7) | |

| Moderate | 80 (20.0) | 54 (20.8) | 26 (18.7) | |

| Severe | 89 (22.3) | 59 (22.7) | 30 (21.6) | |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)g (N, %) | 122 (30.5) | 80 (30.9) | 42 (30.2) | 0.890 |

| Psychological distress (K10)h categorical (N, %) | ||||

| Little or no distress | 175 (43.8) | 109 (42.4) | 66 (47.8) | 0.193 |

| Mild distress | 66 (16.5) | 46 (17.9) | 20 (14.5) | |

| Moderate distress | 50 (12.5) | 28 (10.9) | 22 (15.9) | |

| Severe distress | 104 (26.0) | 74 (28.8) | 30 (21.7) | |

| Urban Life Stress Scalei (median, IQR) | 40 (30, 54) | 39 (30, 54) | 43 (31, 55) | 0.345 |

| Substance use characteristics | ||||

| Risky alcohol usej (N, %) | 122 (30.5) | 87 (33.50) | 35 (25.2) | 0.087 |

| Past 30-day substance use (N, %) | ||||

| Any illicit drugsk | 212 (53.0) | 142 (55.3) | 70 (52.2) | 0.570 |

| Amphetamine | 126 (31.5) | 83 (32.3) | 43 (31.9) | 0.929 |

| Cocaine | 109 (27.3) | 78 (30.4) | 31 (23.0) | 0.121 |

| Opioids | 79 (19.8) | 48 (18.7) | 31 (23.3) | 0.281 |

| Cannabis | 258 (64.5) | 172 (65.9) | 86 (63.2) | 0.597 |

Note

P-values are based on bivariate analyses comparing people who had a smoke-free home adoption attempt versus those who did not. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests, Pearson correlation, or corresponding nonparametric tests based on distributional properties. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher exact test.

⁎Presented proportions are column percents.

aThe primary outcome of smoke-free home adoption attempts was defined as either reporting an attempt to establish a smoke-free home rule (i.e., no smoking at any time in any part of the home) or reporting an attempt to refrain from smoking in their home, even for one day during the three months prior to enrollment in the intervention.

bTwo participants did not report their gender, and five participants did not report their race/ethnicity, resulting in percentages that do not add up to 100 %.

cSerious mental illness (SMI) included self-reported diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder.

dAny mental health condition included a positive screen on the CES-D-10, GAD-7, or PC-PTSD-5.

eWe used the Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) to screen for depression.

fWe measured anxiety with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7).

gWe screened for PTSD symptoms using the Primary Care-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Screen (PC-PTSD-5) and reported the screen-positive rate using a cut point of 4.

hWe assessed psychological distress using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), with scores < 20 indicating little or no distress, 20–24 mild levels of distress, 25–29 moderate, and 30 severe levels of distress.

iWe assessed community-level stressors using the 21-item Urban Life Stress Scale (ULSS) total score.

jWe measured risky alcohol use with the AUDIT-C (4 for male and 3 for non-male participants).

kIllicit drug use includes amphetamines, cocaine, and opioids.

3.2. Mental health and substance use

Over half (55.5 %) screened positive for depression, 42.3 % had moderate or severe anxiety, 38.5 % had moderate to severe psychological distress, and 30.5 % screened positive for PTSD (Table 1), with no difference by smoke-free home adoption attempts. Over half of the participants (53 %) reported illicit drug use in the past 30 days, 36.8 % screened positive for problematic cannabis use, and 30.5 % had risky alcohol use. The most common substances used in the past 30 days were cannabis (64.5 %), amphetamines (31.5 %), and cocaine (27.3 %).

3.3. Nicotine dependence and tobacco cessation history

Almost all participants smoked every day (94.3 %) (Table 2); participants who made a smoke-free home adoption attempt were less likely to smoke daily. The mean daily cigarette consumption was 11.1 cigarettes (SD 7.5), and 68.5 % smoked within 30 min of waking, with measures of nicotine dependence being lower among those who attempted to adopt a smoke-free home. Use of cigarettes with other tobacco products was common, with 30.8 % of participants reporting dual use of cigarettes with one non-cigarette tobacco product and 18 % reporting poly-use of cigarettes with two or more non-cigarette tobacco products in the past 30 days. The most common non-cigarette tobacco products used in the past 30 days were blunts (33.3 %), e-cigarettes, (19.3 %), and cigars/little cigars (15.8 %). Slightly more than half (51.5 %) attempted to quit smoking cigarettes in the past year, with 59.7 % reporting quitting cold turkey and 23.3 % reporting using cessation medications during their last quit attempt. Individuals who attempted to adopt a smoke-free home were more likely to quit in the past year than those who did not.

Table 2.

Bivariate Analyses of Tobacco Use Factors Associated with Smoke-free Home Adoption Attemptsa Among Participants in the Smoke-Free Home Study.

| Smoke-Free Home Attempt |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No | Yes | P | |

| Enrolled participants | 400 | 261 (65.25) | 139 (34.8) | |

| Cigarette frequency (N, %) | ||||

| Someday | 23 (5.8) | 8 (3.1) | 15 (10.8) | 0.002 |

| Everyday | 377 (94.3) | 253 (96.9) | 124 (89.2) | |

| Cigarettes smoked per day (mean, SD) | 11.1 (7.5) | 11.9 (8.0) | 9.6 (6.2) | 0.002 |

| Time to first cigarette after waking (N, %) | ||||

| Within 5 min | 156 (39.0) | 119 (45.6) | 37 (26.6) | < 0.001 |

| 6–30 min | 118 (29.5) | 67 (25.7) | 51 (36.7) | |

| 31–60 min | 55 (13.8) | 39 (14.9) | 16 (11.5) | |

| After 60 min | 71 (17.8) | 36 (13.8) | 35 (25.2) | |

| Intention to quit (N, %) | ||||

| I never expect to quit | 61 (15.3) | 50 (19.2) | 11 (7.9) | 0.012 |

| I may quit | 258 (64.5) | 165 (63.2) | 93 (66.9) | |

| I will quit in the next 6 months | 68 (17.0) | 40 (15.3) | 28 (20.1) | |

| I will quit in the next month | 13 (3.3) | 6 (2.3) | 7 (5.0) | |

| Advised to quit by a healthcare provider in past 12-months (N, %) |

194 (48.5) | 126 (48.3) | 68 (48.9) | 0.902 |

| Had a past 12 months quit attempt (N, %) | 206 (51.5) | 117 (44.8) | 89 (64.0) | < 0.001 |

| Products, methods or resources used to stop smoking (N, %) |

||||

| Cold turkey | 123 (59.7) | 72 (61.5) | 51 (57.3) | 0.539 |

| NRT or non-NRT smoking cessation medications | 48 (23.3) | 27 (23.1) | 21 (23.6) | 0.931 |

| Use of other tobacco products | ||||

| Dual tobacco product use (N, %)b | 123 (30.8) | 77 (29.5) | 46 (33.1) | 0.459 |

| Poly tobacco product use (N, %)c | 72 (18.0) | 43 (16.5) | 29 (20.9) | 0.277 |

| E-cigarettes | ||||

| Used in the past 30 days (N, %) | 77 (19.2) | 39 (14.9) | 38 (27.3) | 0.003 |

| Number of days used in the past 30 days (median, IQR) | 7 (3, 20) | 7 (3, 30) | 6.5 (3, 15) | 0.719 |

| Ways participants use their e-cigarette | ||||

| Continuously throughout the day | 21 (27.8) | 14 (35.9) | 7 (18.4) | 0.173 |

| Distinct bouts shorter than smoking cigarettes | 26 (33.8) | 9 (23.1) | 17 (44.7) | |

| Distinct bouts similar to smoking cigarettes | 20 (26.0) | 11 (28.2) | 9 (23.7) | |

| Other | 10 (13.0) | 5 (12.8) | 5 (13.2) | |

| Daily use (people who used every day in past 30 days). (N, %) |

18 (23.4) | 10 (25.6) | 8 (21.1) | 0.634 |

| Blunts | ||||

| Used in the past 30 days (N, %) | 133 (33.3) | 84 (32.2) | 49 (36.0) | 0.441 |

| Number of days used in the past 30 days (median, IQR) | 8 (2, 29) | 7.5 (2, 29.5) | 10 (2, 20) | 0.890 |

| Daily use (every day in past 30 days) (N, %) | 32 (24.1) | 21 (25.0) | 11 (22.4) | 0.740 |

| Cigars | ||||

| Used in the past 30 days (N, %) | 63 (15.8) | 42 (16.1) | 21 (15.1) | 0.797 |

| Number of days used in the past 30 days (median, IQR) | 4 (1, 20) | 7 (3, 20) | 2 (1, 4) | 0.028 |

| Daily use (every day in past 30 days) (N, %) | 14 (22.2) | 10 (23.8) | 4 (19.1) | 0.668 |

| Smokeless tobacco | ||||

| Used in the past 30 days (N, %) | 7 (1.8) | 6 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0.250 |

| Number of days used in the past 30 days (median, IQR) | 2 (1, 15) | 2 (1, 15) | 3 (3, 3) | 0.611 |

| Daily use (every day in past 30 days) (N, %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ---d |

| Hookah | ||||

| Used in the past 30 days (N, %) | 5 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (2.2) | 0.229 |

| Number of days used in the past 30 days (median, IQR) | 4 (2, 15) | 22.5 (15, 30) | 2 (1, 4) | 0.039 |

| Daily use (every day in past 30 days) (N, %) | 1 (20) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | ---d |

Note

P-values are based on bivariate analyses comparing people who had a smoke-free home adoption attempt versus those who did not. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests, Pearson correlation, or corresponding nonparametric tests based on distributional properties. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher exact test.

⁎Presented proportions are column percents.

aThe primary outcome of smoke-free home adoption attempts was defined as either reporting an attempt to establish a smoke-free home rule (i.e., no smoking at any time in any part of the home) or reporting an attempt to refrain from smoking in their home, even for one day during the three months prior to enrollment in the intervention.

bWe defined dual tobacco product use as using cigarettes and one other non-cigarette tobacco product.

cWe defined poly-tobacco product use as using cigarettes and two or more other non-cigarette tobacco products.

dP-value not calculated due to small sample size.

Of the 77 participants who reported e-cigarette use, 35 % reported using their device four or more times per day, 26 % reported using their device in distinct bouts similar to how they used cigarettes, 33.8 % used it in bouts shorter than how they smoked cigarettes, and 27.3 % said they used their device continuously throughout the day (Table 2). Among participants who used e-cigarettes, 80.5 % did not know the concentration of the nicotine used in their device. Participants who used e-cigarettes were younger, had a higher prevalence of serious mental illnesses and other mental health conditions and substance use, and were less likely to be advised to quit smoking by a healthcare provider compared to participants not using e-cigarettes (Supplementary Material).

3.4. Secondhand tobacco smoke exposure

Most participants (61 %) reported outdoor exposure (e.g., in front of their building) to secondhand tobacco smoke a few times a week or every day (Fig. 1). A minority (21 %) reported smelling secondhand tobacco smoke inside their apartment every day or a few days per week.

3.5. Attitudes towards smoke-free tobacco policies

When asked about a hypothetical policy restricting indoor tobacco use, 44.8 % (N = 179) agreed that they would support such a policy, 67.8 % (N = 271) said they would try to cut down because of the policy, and 35.8 % (N = 143) said they would try to stop smoking completely. While 73.5 % (N = 294) disagreed that they would move because of the policy, 59.8 % (N = 239) reported that they would continue to smoke indoors despite the policy. The median score for attitudes toward a smoke-free tobacco policy was 2.2 out of 4 (IQR, 1.4, 2.6).

3.6. Voluntary smoke-free home rules and adoption

At the time of enrollment, 98.3 % of participants reported that smoking was allowed in their homes. However, 70.8 % were thinking about making their home smoke-free, and 5.8 % had already decided to make their home smoke-free. In the three months prior to enrollment in the study, 34.8 % made a smoke-free home adoption attempt.

3.7. Factors associated with smoke-free home adoption attempts

In multivariable analysis (Table 3), past 30-day e-cigarette use (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] 2.92, 95 % Confidence Interval [CI] 1.48, 5.77) and more positive attitudes towards smoke-free policies (AOR 2.13, 95 % CI 1.43, 3.18) were associated with increased odds of smoke-free home adoption attempts. On the other hand, having a longer tenure at their current PSH residence (AOR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.89, 0.99), smoking within 5 min of waking (AOR 0.55, 95 % CI 0.31, 0.97), and having a serious mental illness (AOR 0.51, 95 % CI 0.30, 0.88) were associated with lower odds of smoke-free home adoption attempts.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Smoke-Free Home Adoption Attempts in the 3 Months Prior to Enrollment (N = 390)a.

| Outcome: smoke-free home adoption attemptb | ORc | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.03 |

| Gender (ref: male) | |||

| Female | 0.76 | 0.43 | 1.34 |

| Transgender/non-binary | 0.91 | 0.27 | 3.04 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: White) | |||

| Black | 0.91 | 0.46 | 1.81 |

| Hispanic | 1.50 | 0.66 | 3.43 |

| All other racesd | 1.37 | 0.62 | 3.02 |

| Length of stay in current residence | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.99⁎ |

| Mean cigarettes per day | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.01 |

| Smoking within 5 min of waking (ref: > than 5 min) | 0.55 | 0.31 | 0.97⁎ |

| Past 30-day e-cig use (ref: no use) | 2.92 | 1.48 | 5.77⁎ |

| Intention to quit (ref: never expect to quit) | |||

| I may quit | 1.76 | 0.74 | 4.16 |

| I will quit in the next 6 months | 1.44 | 0.51 | 4.04 |

| I will quit in the next month | 3.20 | 0.67 | 15.28 |

| Attitudes toward a smoke-free policy | 2.13 | 1.43 | 3.18⁎ |

| Serious mental illnesse (ref: no diagnosis) | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.88⁎ |

| Illicit drug usef (ref: no use) | 0.82 | 0.47 | 1.44 |

| Cannabis useg (ref: no use) | 0.72 | 0.42 | 1.25 |

| Model P < 0.001 | |||

Note

The analytic sample was 390, accounting for missing data on independent variables (nine participants did not report their illicit drug use, and one participant was missing length of stay at their current residence data).

The primary outcome variable was a binary indicator of whether a participant tried to establish a smoke-free rule in their home or attempted not to smoke in their home in the past 3 months.

Multivariable logistic regression mixed model (LMM) with a random intercept to address clustering by permanent supportive housing sites and adjusted for age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Other races included Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander, multi/biracial, and participants who did not report their race.

Serious mental illness (SMI) included a self-reported diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder.

Illicit drug use included any past 30-day use of opioids, amphetamines, or cocaine.

Any past 30-day use of cannabis.

Indicates significance at the < .05 level.

4. Discussion

Among PSH residents participating in a smoke-free home RCT, one-third had attempted to adopt a smoke-free home in the three months prior to joining the study. However, all were smoking in their homes at the time of enrollment, highlighting the need for effective approaches to sustain the voluntary adoption of smoke-free homes. Consistent with a previous study in PSH, we found that a positive attitude towards smoke-free policies was associated with increased attempts to adopt a smoke-free home (Durazo et al., 2021). Contrary to a previous study in a nationally representative sample of US adults that found vaping inside the home was associated with smoking in one’s home (Li et al., 2020), we found that e-cigarette use was associated with smoke-free home adoption attempts in PSH.

Perceptions that e-cigarettes are safer, less stigmatizing, or more socially acceptable, due to the absence of smoke odors and beliefs about reduced harm to others, may contribute to their indoor use (Bandi et al., 2023, Li et al., 2020, Shi et al., 2017). In addition, barriers to smoking outdoors, such as physical limitations, inclement weather, or stigma, may further increase indoor use of e-cigarettes among multi-unit housing residents (Vijayaraghavan et al., 2017, Vijayaraghavan et al., 2023). However, aerosols from e-cigarettes contain carcinogens and have been linked to increased cardiovascular disease risk and metabolic syndrome among people who use them (Cai and Bidulescu, 2023, Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, 2018, Glantz et al., 2024, Khadka et al., 2021, Salazar et al., 2025), and exposure to secondhand aerosol increases health risks for people who do not use e-cigarettes (Amalia et al., 2023, Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, 2018, Kapiamba et al., 2022). Moreover, smoke-free policies that are not inclusive of e-cigarettes may introduce confusion and decrease overall adherence to a smoke-free policy (American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation, 2025).

While some believe that switching completely from combustible cigarettes to e-cigarettes may reduce harm, 30–40 % of people who use e-cigarettes also use combustible cigarettes (Mayer et al., 2020; QuickStats, 2023), which may compound health risks compared to using either product alone (Benowitz et al., 2020, Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, 2018, Glantz et al., 2024, Khadka et al., 2021, Mohammadi et al., 2022). Population-based studies have also shown that e-cigarettes are not associated with tobacco cessation (Quach et al., 2025). Our finding that participants who also used e-cigarettes were less likely to be advised to quit highlights the need to address co-use in this population. As the use of e-cigarettes evolves, there will be a need to implement clean air policies inclusive of e-cigarette use to reduce the indoor dual use of these products in PSH.

Consistent with a prior study in multi-unit affordable housing, nearly half of the participants expressed support for a smoke-free policy (Patel et al., 2022). In our study, almost three-quarters of residents reported they would not move if a smoke-free policy were implemented, and a majority reported they would reduce their smoking if a policy were in place (Kingsbury and Reckinger, 2016). Among PSH residents who smoke, support for smoke-free policies is linked with higher rates of smoke-free home adoption, emphasizing the need for voluntary, ground-up approaches to foster resident support for these policies (Petersen et al., 2018, Vijayaraghavan and King, 2020). Approaches that include education, coaching, and self-enforcement align with the PSH framework and, when paired with building-wide policies and cessation support, could be impactful in reducing tobacco-related harm (Alizaga et al., 2020; Durazo et al., 2021).

The negative association between length of residence and smoke-free home adoption attempts suggests that longer-term residents who were 'grandfathered' into buildings with smoke-free policies (a minority in our sample) may have been less motivated to stop smoking in their homes compared to newer residents whose leases explicitly outlined the policy. Smoke-free policies that are not universally enforced for all residents can create confusion for new residents, undermine smoke-free policies, and make enforcement difficult for property managers (American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation, 2025; Kaufman et al., 2018).

Smoke-free policies and smoking cessation treatment have reinforcing effects in helping people quit tobacco use (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2009). Around half of the participants tried to quit smoking in the past year, but most did not use any evidence-based treatment. Barriers to using evidence-based cessation treatment include a lack of knowledge and misconceptions about treatment (e.g., side effects of medications), mistrust in providers, and a lack of co-located interventions in PSH (Aschbrenner et al., 2015, Nguyen et al., 2015). Providing tobacco treatment within PSH sites or linking residents with community-based tobacco treatment with smoke-free policies could increase the efficacy of quit attempts (Aschbrenner et al., 2015, Aschbrenner et al., 2019). Our findings also suggest that tobacco treatment needs to incorporate support for quitting e-cigarettes to help residents adopt a smoke-free home that is free from smoke and nicotine aerosols.

Prior research shows that serious mental illnesses are associated with higher smoking rates and greater difficulty sustaining cessation (Hawes et al., 2021). Our results extend these findings by showing that having a serious mental illness is associated with a decreased likelihood of adopting a smoke-free home. This relationship may be driven by impaired executive functioning, higher nicotine dependence, and reduced social support, which can make it more difficult to initiate and maintain behavior changes such as adopting a smoke-free home (Evins et al., 2015, Leutwyler et al., 2025). People with serious mental illness also experience impaired cognitive and adaptive functioning, which is further exacerbated by smoking, and social isolation can negatively impact mental well-being (Depp et al., 2015, Jenkins et al., 2023). Residents with serious mental illness may benefit from added support, such as peer-led interventions that reduce social isolation and promote physical activity, to increase engagement in smoke-free home adoption and smoking cessation (Cabassa et al., 2021, Hawes et al., 2021, Leutwyler et al., 2025).

Our study has limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we cannot make causal inferences. The use of self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall and social desirability bias. We did not conduct an exploratory factor analysis for the attitudes scale; however, the scale performed similarly in our previous studies of adults living in PSH (Durazo et al., 202; Petersen et al., 2018, Petersen et al., 2020; Vijayaraghavan and Pierce, 2015). Our sample of PSH residents was drawn from 40 multi-unit, project-based PSH sites in the San Francisco Bay area, which may limit generalizability to other models and geographic locations of PSH. Attitudes and smoke-free home attempts may differ among PSH residents in other states or countries with less robust smoke-free policies than California (American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation, 2025).

This study informs smoke-free home policy implementation in PSH and highlights support for smoke-free home adoption among residents. However, to realize the optimal health effects of smoke-free policies, there is a need to accompany policies with tobacco treatment and address the indoor use of e-cigarettes that might undermine smoke-free policies. Such support may be particularly beneficial for residents with serious mental illness, who comprise a substantial proportion of PSH residents and who face among the highest burdens of tobacco use in the US. Smoke-free home policies that reduce SHS and aerosol exposure and encourage smoking cessation can reduce the large disparities in tobacco-related morbidity and mortality among adults who have experienced homelessness.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hawes Mark R: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Deepalika Chakravarty: Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jessica Alway: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Investigation. Wendy Max: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Margot Kushel: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Narges Neyazi: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Fan Xia: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Maya Vijayaraghavan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 20–33214)

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R37 CA248448, PI: Vijayaraghavan). M.R.H. was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32DA057216) and the UCSF Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our deep appreciation to the Smoke-Free Home participants and our PSH partners for their commitment and dedication to the study. We also want to express deep appreciation to the Smoke-Free Home research staff in the field for their perseverance and commitment.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.dadr.2025.100363.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Data Availability

Deidentified data are available upon request.

References

- Adamson S.J., Sellman J.D. A prototype screening instrument for cannabis use disorder: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test (CUDIT) in an alcohol-dependent clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22(3):309–315. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Delaimy W., Edland S., Pierce J., Mills A., White M., Emory K., Boman M., Smith J. California Tobacco Survey (CTS) 2008. In California Tobacco Survey (CTS) [Application/pdf,image/jpeg,application/pdf,image/jpeg,application/pdf,image/jpeg,application/pdf,image/jpeg,application/octet-stream,application/octet-stream]. UC San Diego Library Digital. Collections. 2015 doi: 10.6075/J0KW5CX7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alizaga N.M., Nguyen T., Petersen A.B., Elser H., Vijayaraghavan M. Developing tobacco control interventions in permanent supportive housing for formerly homeless adults. Health Promot. Pract. 2020;21(6):972–982. doi: 10.1177/1524839919839358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amalia B., Fu M., Tigova O., Ballbè M., Paniello-Castillo B., Castellano Y., Vyzikidou V.K., O’Donnell R., Dobson R., Lugo A., Veronese C., Pérez-Ortuño R., Pascual J.A., Cortés N., Gil F., Olmedo P., Soriano J.B., Boffi R., Ruprecht A.…Fernández E. Exposure to secondhand aerosol from electronic cigarettes at homes: a real-life study in four European countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;854 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. (2025). States and municipalities with laws regulating use of electronic smoking devices (ESDs) [PDF]. 〈Https://no-smoke.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/ecigslaws.pdf〉. (n.d.).

- Andresen E.M., Malmgren J.A., Carter W.B., Patrick D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale) Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschbrenner K.A., Ferron J.C., Mueser K.T., Bartels S.J., Brunette M.F. Social predictors of cessation treatment use among smokers with serious mental illness. Addict. Behav. 2015;41:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschbrenner K.A., Naslund J.A., Gill L., Hughes T., O’Malley A.J., Bartels S.J., Brunette M.F. Qualitative analysis of social network influences on quitting smoking among individuals with serious mental illness. J. Ment. Health. 2019;28(5):475–481. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1340600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi P., Star J., Minihan A.K., Patel M., Nargis N., Jemal A. Changes in E-cigarette use among U.S. Adults, 2019–2021. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023;65(2):322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz N.L., Iii P.J., Ahijevych K., Jarvis M.J., Hall S., LeHouezec J., Hansson A., Lichtenstein E., Henningfield J., Tsoh J., Hurt R.D., Velicer W. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2002;4(2):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz N.L., St.Helen G., Nardone N., Addo N., Zhang J. (Jim), Harvanko A.M., Calfee C.S., Jacob P. Twenty-four-hour cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes compared with cigarette smoking in dual users. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020;9(23) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin M.J., Kimerling R., Weathers F.W., Prins A., Marx B.P., Post E.P., Schnurr P.P. Diagnostic accuracy and acceptability of the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen for the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fifth Edition) among US Veterans. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K.A., DeBenedetti A.F., Volk R.J., Williams E.C., Frank D., Kivlahan D.R. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31(7):1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa L.J., Stefancic A., Lewis-Fernández R., Luchsinger J., Weinstein L.C., Guo S., Palinkas L., Bochicchio L., Wang X., O’Hara K., Blady M., Simiriglia C., Medina McCurdy M. Main outcomes of a peer-led healthy lifestyle intervention for people with serious mental illness in supportive housing. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021;72(5):555–562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Bidulescu A. Associations between e-cigarette use or dual use of e-cigarette and combustible cigarette and metabolic syndrome: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Ann. Epidemiol. 2023;85:93–99.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems . In: Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Stratton K., Kwan L.Y., Eaton D.L., editors. National Academies Press; 2018. Board on population health and public health practice, health and medicine division, & national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine; p. 24952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depp C.A., Bowie C.R., Mausbach B.T., Wolyniec P., Thornquist M.H., Luke J.R., McGrath J.A., Pulver A.E., Patterson T.L., Harvey P.D. Current smoking is associated with worse cognitive and adaptive functioning in serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015;131(5):333–341. doi: 10.1111/acps.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazo A., Hartman-Filson M., Perez K., Alizaga N.M., Petersen A.B., Vijayaraghavan M. Smoke-free home intervention in permanent supportive housing: a multifaceted intervention pilot. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021;23(1):63–70. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evins A.E., Cather C., Laffer A. Treatment of tobacco use disorders in smokers with serious mental illness: toward clinical best practices. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):90–98. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz S.A., Nguyen N., Oliveira Da Silva A.L. Population-based disease odds for E-cigarettes and dual use versus cigarettes. NEJM Evid. 2024;3(3) doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2300229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn E.J., Rayens M.K., Wiggins A.T., Gan W., Brown H.M., Mullett T.W. Lung cancer incidence and the strength of municipal smoke-free ordinances. Cancer. 2018;124(2):374–380. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes M.R., Roth K.B., Wang X., Stefancic A., Weatherly C., Cabassa L.J. Ideal cardiovascular health in racially and ethnically diverse people with serious mental illness. J. Health Care Poor Under. 2020;31(4):1669–1692. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2020.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes M.R., Roth K.B., Cabassa L.J. Systematic review of psychosocial smoking cessation interventions for people with serious mental illness. J. Dual Diagn. 2021:1–20. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2021.1944712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Pan Z., Wu J., Hu C., Bai L., Lyu J. Health effects of tobacco at the global, regional, and national levels: results from the 2019 global burden of disease study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022;24(6):864–870. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood B.F., Byrne T., Scriber B. Examining mortality among formerly homeless adults enrolled in housing first: an observational study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1209. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homa D.M., Neff L.J., King B.A., Caraballo R.S., Bunnell R.E., Babb S.D., Garrett B.E., Sosnoff C.S., Wang L., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vol. 64. 2015. Vital signs: Disparities in nonsmokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke--United States, 1999-2012; pp. 103–108. (MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer . Vol. 13. WHO Press; Lyon, France: 2009. (Evaluating the effectiveness of smoke-free policies/IARC working group on the evaluation of the effectiveness of smoke-free policies). (n.d.) [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee K.D., Liu G.C., Canty-Mitchell J., Qi R.A., Austin J., Swigonski N. Race, urban community stressors, and behavioral and emotional problems of children with special health care needs. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005;56(1):63–69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins G.T., Janich N., Wu S., Shafer M. Social isolation and mental health: Evidence from adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2023;46(2):148–155. doi: 10.1037/prj0000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiamba K.F., Hao W., Owusu S.Y., Liu W., Huang Y.-W., Wang Y. Examining metal contents in primary and secondhand aerosols released by electronic cigarettes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022;35(6):954–962. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.1c00411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman P., Kang J., Kennedy R.D., Beck P., Ferrence R. Impact of smoke-free housing policy lease exemptions on compliance, enforcement and smoking behavior: a qualitative study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018;10:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler M.C., Bundy L., Haardörfer R., Escoffery C., Berg C., Yembra D., Kreuter M., Hovell M., Williams R., Mullen P.D., Ribisl K., Burnham D. A minimal intervention to promote smoke-free homes among 2-1-1 callers: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Public Health. 2015;105(3):530–537. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.-L.T., Walters E.E., Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadka S., Awasthi M., Lamichhane R.R., Ojha C., Mamudu H.M., Lavie C.J., Daggubati R., Paul T.K. The cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2021;23(5):40. doi: 10.1007/s11886-021-01469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury J.H., Reckinger D. Clearing the air: smoke-free housing policies, smoking, and secondhand smoke exposure among affordable housing residents in Minnesota, 2014–2015. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016;13 doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutwyler H., Mock J., Hubbard E., Bussell T., Zahedikia N., Vaghar N., Balestra D., Wuest S., Wallhagen M., Okoli C. Social and environmental factors during the smoking cessation process: The experiences of adults with serious mental illnesses. Schizophr. Res. 2025;277:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2025.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Shi H., Xie Z., Rahman I., McIntosh S., Bansal-Travers M., Winickoff J.P., Drehmer J.E., Ossip D.J. Home smoking and vaping policies among US adults: results from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, wave 3. Prev. Med. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht A.S., King B.A., Travers M.J., Rivard C., Hyland A.J. Attitudes, experiences, and acceptance of smoke-free policies among US multiunit housing residents. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102(10):1868–1871. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightwood J.M., Glantz S.A. Declines in acute myocardial infarction after smoke-free laws and individual risk attributable to secondhand smoke. Circulation. 2009;120(14):1373–1379. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.870691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M., Reyes-Guzman C., Grana R., Choi K., Freedman N.D. Demographic characteristics, cigarette smoking, and e-cigarette use among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi L., Han D.D., Xu F., Huang A., Derakhshandeh R., Rao P., Whitlatch A., Cheng J., Keith R.J., Hamburg N.M., Ganz P., Hellman J., Schick S.F., Springer M.L. Chronic E-cigarette use impairs endothelial function on the physiological and cellular levels. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022;42(11):1333–1350. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.317749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M.-A.H., Reitzel L.R., Kendzor D.E., Businelle M.S. Perceived cessation treatment effectiveness, medication preferences, and barriers to quitting among light and moderate/heavy homeless smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odes R., Alway J., Kushel M., Max W., Vijayaraghavan M. The smoke-free home study: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial of a smoke-free home intervention in permanent supportive housing. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2076. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., Donovan E.M., Liu M., Solomon-Maynard M., Schillo B.S. Policy support for smoke-free and e-cigarette free multiunit housing. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022;36(1):106–116. doi: 10.1177/08901171211035210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A.B., Stewart H.C., Walters J., Vijayaraghavan M. Smoking policy change within permanent supportive housing. J. Community Health. 2018;43(2):312–320. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0423-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A.B., Elser H., Nguyen T., Alizaga N.M., Vijayaraghavan M. Smoke-free or not: attitudes toward indoor smoke-free policies among permanent supportive housing residents. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020;34(1):32–41. doi: 10.1177/0890117119876763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach N.E., Pierce J.P., Chen J., Dang B., Stone M.D., Strong D.R., Trinidad D.R., McMenamin S.B., Messer K. Daily or nondaily vaping and smoking cessation among smokers. JAMA Netw. Open. 2025;8(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QuickStats: Percentage Distribution of Cigarette Smoking Status Among Current Adult E-Cigarette Users, by Age Group—National Health Interview Survey United States, 2021. Mmwr. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023;72(10):270. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7210a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar M.R., Saini L., Nguyen T.B., Pinkerton K.E., Madl A.K., Cole A.M., Poulin B.A. Elevated toxic element emissions from popular disposable e-cigarettes: sources, life cycle, and health risks. ACS Cent. Sci. 2025 doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5c00641. acscentsci.5c00641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer G.L., Njai R., Grant-Lenzy A.M. Modes of marijuana use – smoking, vaping, eating, and dabbing: Results from the 2016 BRFSS in 12 States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;209 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Cummins S.E., Zhu S.-H. Use of electronic cigarettes in smoke-free environments. Tob. Control. 2017;26(e1):e19–e22. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 2023 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress (2023). The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2023.〈Https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar/2023-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us.html〉. (n.d.).

- Tsai J., Homa D.M., Gentzke A.S., Mahoney M., Sharapova S.R., Sosnoff C.S., Caron K.T., Wang L., Melstrom P.C., Trivers K.F. Exposure to secondhand smoke among nonsmokers—United States, 1988–2014. Mmwr. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018;67(48):1342–1346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6748a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S., Gulcur L., Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am. J. Public Health. 2004;94(4):651–656. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2024). Eliminating Tobacco-Related Disease and Death: Addressing Disparities—A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015). U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Instituting smoke-free public housing (24 CFR Parts 965 and 966, Docket No. FR 5597-P-02, RIN 2577-AC97). Https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/12/05/2016-28986/instituting-smoke-free-public-housing. 2015.

- Vijayaraghavan M., King B.A. Advancing housing and health: promoting smoking cessation in permanent supportive housing. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(4):415–419. doi: 10.1177/0033354920922374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan M., Pierce J.P. Interest in smoking cessation related to a smoke-free policy among homeless adults. J. Community Health. 2015;40(4):686–691. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan M., Hurst S., Pierce J.P. A qualitative examination of smoke-free policies and electronic cigarettes among sheltered homeless adults. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017;31(3):243–250. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.150318-QUAL-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan M., Hartman-Filson M., Vyas P., Katyal T., Nguyen T., Handley M.A. Multi-level influences of smoke-free policies in subsidized housing: applying the COM-B model and neighborhood assessments to inform smoke-free policies. Health Promot. Pract. 2023;152483992311749 doi: 10.1177/15248399231174925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data are available upon request.