Abstract

An important class of gels are those composed of a polymer network and fluid solvent. The mechanical and rheological properties of these two-fluid gels can change dramatically in response to temperature, stress, and chemical stimulus. Because of their adaptivity, these gels are important in many biological systems, e.g. gels make up the cytoplasm of cells and the mucus in the respiratory and digestive systems, and they are involved in the formation of blood clots. In this study we consider a mathematical model for gels that treats the network phase as a viscoelastic fluid with spatially and temporally varying material parameters and treats the solvent phase as a viscous Newtonian fluid. The dynamics are governed by a coupled system of time-dependent partial differential equations which consist of transport equations for the two phases, constitutive equations for the viscoelastic stresses, two coupled momentum equations for the velocity fields of the two fluids, and a volume-averaged incompressibility constraint. We present a numerical method based on a staggered grid, second order finite-difference discretization of the momentum equations and a high-resolution unsplit Godunov method for the transport equations. The momentum and incompressibility equations are solved in a coupled manner with the Generalized Minimum Residual (GMRES) method using a multigrid preconditioner based on box-relaxation. We present results on the accuracy and robustness of the method together with an illustration of the interesting behavior of this gel model for the four-roll mill problem.

Keywords: Mixture theory, Transient network model, Multiphase flow, Viscoelastic flow simulations, Krylov subspace, Multigrid

1. Introduction

An important class of gels are those composed of a polymer network immersed in a solvent. Because of their multiphase and multiscale nature, such gels exhibit a number of unique behaviors. In addition to stress due to deformations, these gels may exhibit osmotic and active stresses. Osmotic stress, or swelling stress, results from interactions between the solvent and polymer molecules. Active stresses arise in some biological gels, such as actomyosin, which are crosslinked with molecular motors that convert chemical energy into mechanical work. Additionally, when the polymer network is undergoing polymerization and depolymerization, the rheology of the mixture can be highly variable. In many biological gels such as biofilms, blood clots, mucus, and cytoplasm, polymerization/depolymerization and active/osmotic stresses are regulated as part of their biological function. An essential component in the study of these complex processes is good numerical methods to solve the equations that describe their mechanics.

In many instances, a gel is not adequately described as a single continuous medium. For example, during gel swelling the network moves outward while the solvent moves inward. Modeling the mechanics of gels requires a description beyond a single velocity field and single stress tensor. The two-fluid model is a widely used approach to describe gel mechanics [1,2]. In this model, both network and solvent coexist at each point of space, and each phase (network and solvent) is modeled as a continuum with its own velocity field and constitutive law. The coupled system of partial differential equations that describe the gel presents significant challenges both for analysis and for numerical simulation, and is therefore not well studied. Among the challenges posed by a gel model of this type are the need to determine two velocity fields and a pressure coupled through the two momentum equations and the incompressibility constraint. Another arises if the gel is not homogeneous in which case gel properties, including its elastic modulus, may vary spatially and temporally.

The appropriate rheological description of the network phase depends on the type of gel as well as the time scale of the problem. Gels with permanent crosslinks are usually described as elastic solids. If the crosslinks form and break dynamically, then the network is better described as a viscoelastic fluid or even as a viscous fluid, depending on the relative time scales of the deformation and the crosslinking. A model which captures all of these behaviors is the transient network model [3,4], which in its simplest form is like rubber elasticity with formation and rupture of crosslinks. In the limit that the rupture rate goes to zero, the material becomes a neo-Hookean elastic solid, and in the limit of very fast formation and breaking, the material becomes a viscous fluid. Because of its ability to describe such diverse materials behaviors, this is the type of model we consider in this paper. For other types of models of the dynamics of viscoelastic gels see, for example, [5–7] and the references therein.

When the polymer concentration is uniform, and the formation and rupture of crosslinks is in equilibrium, the equation for the stress tensor is equivalent to the upper convected Maxwell equation. We include an additional viscosity within the network, which makes the network an Oldroyd-B fluid. In this paper, we use a version of the model in which polymer concentration is variable, and the kinetics of link formation are not taken to be in equilibrium. This adds an extra equation for the link density. The elastic modulus of the network is proportional to the link density and so it too evolves in time [8].

Previously we developed algorithms for simulating the equations of gel mechanics using the two-fluid model in which the network and solvent were modeled as viscous fluids without inertia [9–11]. In this paper we extend this work to the case when the network is modeled as an Oldroyd-B fluid and inertia has an effect. The inertia of the fluid can play an important role in applications where the gel is in contact with a rapidly moving Newtonian fluid [12]. We use a conservative, high-resolution unsplit Godunov method on a staggered grid for treating the scalar equations describing the transport of the network and solvent volume fractions. We extend this method to handle the tensor equations for the viscoelastic stresses and elastic modulus. There are similarities of this method with previously developed techniques for treating single-phase viscoelastic fluids [8,13,14]. We use a second order finite-difference discretization of the momentum and incompressibility equations and adapt our iterative method from [9] to handle nonzero Reynolds number flows. This iterative method uses a Krylov subspace method together with a multigrid preconditioner for solving this coupled set of equations without splitting. We find that the adapted method is efficient and robust.

We present numerical experiments showing that our computational technique achieves second order accuracy in space and time for smooth solutions and is stable provided an appropriate CFL-type condition is satisfied. The experiments also show that our method can handle sharp material interfaces without problems, and that it is robust over a wide range of parameters, from cases where the gel behaves like a viscoelastic fluid to others in which it behaves like a viscoelastic solid.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we give a brief introduction to the two-fluid, viscoelastic gel model. In Section 3, we describe the computational method for simulating the gel model. In Section 4, we present several numerical examples including refinement studies illustrating the accuracy of the method and results from simulations involving strongly elastic materials and sharp interfaces between material parameters. In these numerical examples the flow is driven by a background force corresponding to the four-roll mill problem. We conclude the paper with some remarks in Section 5 on future enhancements to the model and computational method that will be considered.

2. Gel model

Our intention in this section is to give a brief introduction to the gel model considered in the present study. A more thorough derivation and discussion of this model and more general gel models can be found in the recent reviews [1,2] and the references therein.

We consider a gel composed of two materials, a polymer network and a fluid solvent. Each point in space is assumed to be occupied by a mixture of network and solvent, which is described by the volume fractions of the two different phases. Each material moves with its own velocity and the total amount of gel is assumed to remain constant. For the model considered in this study, the densities of the two materials are equal and set to a constant value, i.e. the networked material is neutrally buoyant. With these assumptions, conservation of mass leads to the following two equations for the volume fractions:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where , and are the respective volume fractions of the network and solvent, and and are the respective transport velocities. Adding Eqs. (1) and (2) and using reveals that the volume averaged velocity is incompressible:

| (3) |

The transport velocities are determined by Newton’s second law, which in this case are described by the solvent and network momentum equations

| (4) |

| (5) |

The solvent momentum equation reflects our assumption that the solvent behaves as a Newtonian fluid subject to a viscous force and a pressure force , and that it is also acted upon by a drag force when the solvent and polymer velocities differ. Similarly, the network is subject to viscous, pressure, and drag forces given, respectively, by , and , as well as to two additional forces. One is a viscoelastic force due to deformation and restructuring of the network, and the other is a chemical pressure (or osmotic pressure) force arising from chemical interactions due to the presence of the network. In these equations, is the density of the two fluids and is the drag coefficient.

The viscous stresses for both materials are the standard ones for a Newtonian fluid

| (6) |

| (7) |

where are the shear viscosities and are the bulk viscosities of the solvent and network ( is the spatial dimension). For this paper we assume that the chemical pressure is that used in Flory–Huggins polymer theory [15, p. 143]

| (8) |

where , and are constants. The constant affects the amount of mixing of polymer and solvent. In this study, we set and . With this choice of parameters, the chemical pressure favors some mixing and penalizes full phase separation of the gel.

The viscoelastic stress evolves according to the differential constitutive equation

| (9) |

which is derived in Appendix A. Our view of the elastic stresses in the gel is that they derive from deformation of a transient network. The parameter is the rate at which links in the network rupture. The strength of the network at any time and location is denoted by and is proportional to the density of crosslinks present. The variable evolves according to the equation

| (10) |

Here, is proportional to the rate at which new crosslinks form. In this paper, we use of the form

| (11) |

where is a parameter. This is similar to that used in the platelet aggregation model from [12,16] and is chosen to reflect the assumption that crosslinks connect two ‘pieces’ of network and so their formation should depend on the network volume fraction squared.

By defining and , Eq. (9) can be written as

| (12) |

which is similar to the upper convective Maxwell (UCM) equation [17]. The difference is that here the polymer viscosity , the relaxation time , and the elastic modulus are not material parameters, but are functions of the number of links . In this paper, we treat the rupture rate as constant, but it may be a function of and as in more general PTT-type models [18,19].

For ease of implementation, we manipulate (4) and (5) to look more like evolution equations for and . This is accomplished by expanding the derivatives in the left hand side of these equations and using (1) and (2) to simplify and eliminate the terms involving time derivatives of and . With this modification, the complete set of equations we simulate is given by

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

In this study we assume the boundary conditions are periodic. We do not explicitly nondimensionalize these equations because in doing so the number of parameters would not be reduced. Additionally, we avoid defining nondimensional parameters such as the Reynolds number, Weissenberg number, Deborah number, and elastic Mach number [20]. With 2 velocity fields, 4 viscosity parameters, 3 osmotic pressure parameters, a frictional drag coefficient, and a time-varying elastic modulus the rheology of the flow is difficult to characterize with these standard nondimensional numbers for single-phase viscoelastic flow.

3. Computational methodology

We start with a broad overview of the algorithm for numerically solving the coupled system of Eqs. (13)–(19). For notational simplicity, we use superscripts to denote values of the unknowns at different discrete times. The algorithm proceeds with the following staggered-in-time splitting of the equations:

Given the values , and at time , solve for the velocity fields and and the pressure at time using a discrete analog of (16)–(18).

Solve for at time using a discrete analog of (13) and the velocity field from the previous step. Then compute .

Solve for and at time using a discrete analog of (14) and (15) with the velocity field and computed from the two previous steps.

Return to step 1, with time equal to .

Variable time-stepping is employed in the algorithm, hence the notation is used to denote the time-step from to .

The details of the computational methods for each of the steps above is provided for the model equations in two spatial dimensions. Before discussing each method, however, we first describe the grid that is used and make some definitions that help simplify the discussion of the method.

3.1. Grid

A staggered grid in both space and time is used to represent discrete values of the variables as shown in Fig. 1. For simplicity, the mesh spacing in the and direction is set equal and is given by , where is the number of cell-centers in either direction. The time-step is given by . All values of the viscoelastic stress tensor are placed at the cell centers since then the stretching terms in (14) and (15) decouple for each cell center as discussed below. An alternative method common for single-phase viscoelastic flows is to place the diagonal terms of at the cell centers and the off-diagonal terms of at the cell corners. This arrangement of unknowns gives a more natural way of calculating the divergence of the stress tensor since it does not require averaging any entries of [20,21]. However, for our two-phase model, this would have the unattractive consequence of coupling the stretching terms in (14) and (15) and increasing the total computational cost.

Fig. 1.

Location of the unknowns in the space- and time-staggered grid for the 2-D gel model: ▹ = network/solvent horizontal velocity, Δ = network/solvent vertical velocity, •∙= pressure, ◯ = network/solvent volume fractions, □ = components of the viscoelastic stress tensor and .

Since the unknowns are not all collocated at the same spatial locations, averaging of the values is sometime necessary. Here we define the needed averages. Let be a generic grid variable defined at the cell-centers (whole integer pairs ), and and generic grid variables defined at the east-west (EW) and north-south (NS) cell-edges (mix of whole and half integer pairs), respectively. Then the following notation and definitions are used for averaging:

where and are non-negative integers.

3.2. Step 1: Solving the momentum equations and incompressibility constraint

This step is the most computationally intensive part of the algorithm. Letting , and and defining the operators

and the nonlinear terms

the momentum Eqs. (16) and (17) can be expressed as

| (20) |

and are subject to the volume averaged incompressibility constraint (18).

To approximate the solution of (20) and (18), we discretize first in space using centered, second order finite-differences as discussed in B. Replacing the operators and with the respective finite-difference approximations and , replacing the diagonal operators and with the approximations and , and replacing the nonlinear term and with the respective finite-difference approximation and , the semi-discrete system corresponding to (20) is given by

| (21) |

The discrete version of the volume averaged incompressibility constraint (18) can also be written using these discrete operators as

| (22) |

The coupled set of Eqs. (21) and (22) are to be solved to obtain the velocity fields and and pressure at the half-time level . The term involving on the right hand side of (21) is linear in (and ) and makes the system stiff compared to the other non-linear terms. We thus use a semi-implicit scheme for solving (21) in which the linear term is treated implicitly and the non-linear terms are treated explicitly. The semi-implicit scheme we use is the second order backward differentiation/extrapolated backward differentiation (BD/BDE2) method discussed and analyzed in detail in [22]. This scheme is a linear multistep method requiring values for the variables at two previous time levels. Since we use variable time-stepping in the algorithm (as discussed in Section 3.5) and the variables are staggered in time, the BD/BDE2 method given in [22] needs to be slightly modified, as discussed in [23, pp. 132–133].

Letting the time-step from time to be denoted by and the time-step between and be denoted by , we define the ratios and . Additionally, we use superscripts to denote values of the variables at time . With these definitions, we can write BD/BDE2 schemes for solving (21) as follows:

| (23) |

where

| (24) |

| (25) |

The values used for the network and solvent volume fractions in the entries of and are also extrapolated to the time-level in a similar manner as (24). The value for the pressure in (23) is determined from the constraint (22). To boot-strap the BD/BDE2 method we use one-step of the semi-implicit backward/forward Euler method to time and one-step of the BD/BDE2 method using values of the velocity fields at and .

The BD/BDE2 method only requires the solution of one linear-system per time-step to determine the solvent and network velocities and the pressure. Using the definitions for , and , and imposing the constraint (22), the linear system that arises for this method is given as follows:

| (26) |

Letting and , the matrix in (26) can be written in saddle point form as

The matrix is symmetric and positive definite and the matrix has one zero eigenvalue since it annihilates constant vectors. Moreover, it follows from [24, Theorem 3.6] that the eigenvalues of have nonnegative real part ( is positive semistable), i.e. Re for all , which can be advantageous for preconditioned Krylov subspace methods [24].

The method we use for solving (26) is based on the preconditioned Krylov subspace method first introduced for gels in [9] and developed further in [10,11]. The gel model considered in these studies was for two immiscible viscous-dominated fluids and did not contain inertial effects. The preconditioner for the resulting linear system was based on a multigrid procedure with box-relaxation (or symmetric coupled Gauss-Seidel smoothing) [25–27]. We generalized the box-type smoother from [9] for (26) and combined it with a multigrid V-cycle. This method is then used as the preconditioner for the generalized minimum residual (GMRES) method [28]. The presence of inertia in the system (26) makes it better conditioned than the viscous dominated system from [9], and the iterative method converges in very few iterations. In the numerical examples presented in Section 4, the maximum number of iterations required by the method was 8, with the most common numbers being 3 and 4.

The BD/BDE2 scheme has been successfully combined with various spatial discretizations in semi-discrete type formulations for the Navier-Stokes equations (see, for example [29,30]). However, it is not as popular as the semi-implicit scheme that combines Trapezoidal rule (or Crank-Nicholson) and second order Adams-Bashforth (CN/AB2). This is a bit surprising since the BD/BDE2 has many nicer properties. For example, it is -stable and almost always outperforms the CN/AB2 method in terms of stability and in terms of multigrid efficiency (as demonstrated for the convection-diffusion equation in [22]). Although the results are not presented here, we did implement the CN/AB2 scheme for advancing (21) in time. We found that for certain problems which start out transient but then go to a steady-state with zero velocities in both phases, the CN/AB2 scheme was not able to capture this behavior, but instead oscillated around the steady-state. The BD/BDE2 method was able to capture these steady-state solutions. Additionally, in all of our experiments we did not find any examples of problems which remained transient where the CN/AB2 method out performed the BD/BDE2 method.

3.3. Step 2: Solving the advection equation

To advance (13) in time we use a variant of the corner transport upwind (CTU) method of Colella [31], which is a conservative, second order, high-resolution, unsplit Godunov method. We review the details of this method since it will aid the description of the method we use for solving (14) and (15). For notational simplicity, we drop the subscript n from (13) in the description of the discretization below, and use to denote the network volume fraction.

The CTU scheme for advancing (13) in time from to at the cell center can be written in conservative form as

| (27) |

where

| (28) |

| (29) |

The two velocity components at the time level are obtained from Step 1 of the algorithm. The values of at the time level and at the EW and NS edges of the cell centered at are obtained by Taylor series expansions in which temporal derivatives are expressed in terms of spatial derivatives using (13). For each cell edge, this results in two approximations to , one from each of the two cells which share that edge. The approximations at the E and W edges for the cell are given by

| (30) |

where E and W correspond to the plus and minus case, respectively. The expression after the second equal sign is obtained by replacing with according to the advection Eq. (13), and then applying the product rule to . Similarly, the approximations at the N and south S horizontal edges are given by

| (31) |

The velocities at the time level in (30) and (31) are obtained by constant extrapolation of the velocity from the time level. These first order accurate extrapolated values are only used in the correction terms to the edge values of the volume fraction. Thus, the overall approximation of the edge values remains second order accurate.

There are two variants of the CTU algorithm that can be followed at this point. Starting with (30), the first variant is to approximate with limited differencing, approximate with (staggered) centered differencing, and approximate the transverse (conservative) derivative with upwind differencing. A similar approximation is used for the terms in (31). This variant can lead to overshoots or excessive smearing in the solution when it features large gradients that propagate obliquely to the grid [31, p. 182]. The second variant ameliorates this problem and is the one we use in this study. It is identical to the first variant except in the way the transverse derivatives in (30) and (31) are handled. The method can be viewed as a predictor-corrector method. In the predictor step, (30) and (31) are approximated without the transverse derivatives terms. The corrector step updates the predicted approximations with the transverse derivatives, where, for example, the volume fractions used in the approximation of in (30) are obtained from the first approximation of (31). The update to (31) with its transverse derivative is similarly obtained using the predicted approximation from (30).

The exact details of the predictor step are as follows. First, the two values of the volume fraction at each cell edge are approximated as

| (32) |

| (33) |

Dropping the superscript , the approximate derivatives operators and in (32) and (33) are given by

| (34) |

while and are monotonized central (MC) difference operators [32] and are given by

| (35) |

| (36) |

where

Next, the appropriate approximate edge values and are determined by upwinding:

The corrector step updates the edge values (32) and (33) as

| (37) |

| (38) |

The final step of the CTU scheme is to again use upwinding to choose the appropriate approximate edge values and for the fluxes in (28) and (29).

The use of limiting in (32) and (33) eliminates spurious oscillations in the CTU scheme (27), but it also reduces the order of accuracy to first order where the magnitude of the gradient of is large. In smooth regions, the method is second order accurate (see [31] for a discussion). There is no proof on the monotonicity properties of the CTU scheme, but in all of our experiments the method produces monotone results provided the time-step is chosen appropriately. We discuss the time-step selection in Section 3.5.

3.4. Step 3: Solving the viscoelastic stress equations

Eqs. (14) and (15) can be written in system form as

| (39) |

where we have again dropped the subscript n from the network volume fraction and velocity terms for notational simplicity. To advance this system in time, we use a CTU-type approximation of the advection terms and trapezoidal rule (or Crank-Nicolson) to approximate the remaining terms. The scheme can be written as the following system:

| (40) |

where the first superscript on indicates the time the entries of are taken, and the second superscript indicates that a discrete approximations to the derivatives in has been made (as discussed below). As alluded to in Section 3.1, since all values in reside at the cell-centers (and is computed from the Step 1 of the algorithm), the systems for determining in each of the cell-centers are decoupled. Thus, each can be determined by solving a 4-by-4 linear system. We use Gaussian elimination to compute these solutions.

While (39) is not a conservation law, we can still use the framework of the CTU method to obtain a high-resolution approximation of the fluxes in (40). These fluxes are given by

| (41) |

| (42) |

Following the same strategy as for the advection Eq. (13) from the previous section, the values of at the time level and the vertical and horizontal edges of the cell-center are obtained by Taylor series expansions and use of (39). The approximations of each component of at the E and W vertical edges for the cell are given by

| (43) |

where the equation after the second equal sign is obtained by replacing with the right hand side of (39). Approximations at the N and S horizontal edges are similarly given by

| (44) |

As in (30) and (31), the velocities at the time level in the above approximations are obtained by constant extrapolation of the velocity from the time level.

We use the same predictor-corrector variant of the CTU algorithm as described in the previous section to approximate (43) and (44). That is, all terms in (43) and (44) but the last transverse derivatives are first computed, then the approximations at the cell edges are updated with the transverse derivatives.

MC differencing (35) and (36) is used to approximate and , respectively, and centered differencing (34) is used for and . The discrete approximation to the entries in the matrices are also computed using centered, second order differencing. For the entries and , we again use (34), while for the remaining entries we use the approximations

| (45) |

We conclude the discussion of this step, by noting one modification we make to the final update of the entries in . A well-known property of UCM contitutive equations is that the viscoelastic stress tensor is positive semi-definite [33, p. 17]. Our UCM-type equations also have this property, i.e. , which follows from the derivation of the constitutive model given in A (in particular, see the integral representation (A.2)). The modified CTU/Trapezoidal rule method, however, does not necessarily preserve this property. Therefore, at the end of each time-step, we check all the cell centers for violations of the positive semi-definiteness of . In these violating cells, we perturb so that is the closest (in two-norm) positive semi-definite tensor using the method described in [8, Appendix A]. This method proceeds by first decomposing (now interpreted as a matrix) in the violating cells as and then letting

| (46) |

To make positive semidefinite, the entries of are then changed to

| (47) |

From our extensive numerical tests, we have found that the above procedure only becomes necessary when the viscoelastic stresses and the gradient of become very large.

3.5. Variable time-stepping

We use a variable time-step in the algorithm and choose its value based on different CFL constraints. To understand the relevant timescales and to derive these constraints we first linearize the system of Eqs. (13)–(17) and consider only the transport and elastic stretching terms. The resulting system is of the form

where we have redefined as , and the matrices and are given by

| (48) |

and

| (49) |

This system is hyperbolic if, for any constants and that are not both zero, the matrix has real eigenvalues and is diagonalizable [34, pp. 425–428]. Letting , the eigen-values of this matrix are

| (50) |

The algebraic and geometric multiplicities are 3 for the eigenvalue for , and 1 for the remaining eigenvalues. As discussed at the end of Section 3.4, is positive semi-definite. Additionally, and, for this study, (see (8)). Thus all the eigenvalues of are real and the system is hyperbolic.

We use the eigenvalues (50) corresponding to wave speeds in the - and -directions for determining the CFL constraint on the time-step. This corresponds to setting and in (50). With these values we choose the time-step as follows:

| (51) |

where the values for the velocities are used at the time-level and the values of the volume fraction, viscoelastic stress, and are used at the time-level. Through our numerical experiments we found that we could use a larger stable time-step if we allowed the constants and to differ. The use of different constants makes sense since the whole system (13)–(17) is not advanced in time simultaneously, but is instead split into different parts and different methods are used for each of these parts (see the previous section). In our numerical tests, the values and lead to stable time-stepping. From more extensive testing, we found that this value of is a good choice for a wide range of parameters. However, the value of is linked to the values of the network and solvent viscosities used in the momentum equations and may need to be lowered as these viscosities are lowered. This is related to the stability of the BD/BDE2 method used for advancing the momentum equations. A full analysis of how the viscosity effects the choice of stable time-step for this method applied to the Navier-Stokes equations is given in [30].

We conclude by noting that in general, it is possible to have osmotic potentials such that , which results in a destabilizing force that promotes de-mixing or phase separation [9,35,36]. Our method also works for these cases, however the time-step restriction (51) should be modified so that the absolute value of is used. In regions where is negative, the gel is unstable, and certain modes will grow there. In this case, we are concerned that our scheme does not artificially excite any modes in these regions. By using the absolute value of this term in (51), we err on the side of caution and make the time-step more restrictive than may be necessary.

4. Computational tests

We present a series of computational tests on the gel model (13)–(19) using the algorithm described in the previous section. This model has several parameters whose number cannot be reduced by non-dimensionalization and must therefore be specified. Our goal is not to present an exhaustive study of all the parameter ranges, but instead to present examples which test the accuracy and robustness of the method for some “moderate” and “difficult” parameter ranges and initial conditions. These examples correspond to different behaviors of the gel, from exhibiting characteristics of a viscoelastic fluid to characteristics of a viscoelastic solid. In all these tests, the domain is the periodic unit box centered at the origin.

We set certain relationships between the parameters in order to reduce their numbers. First, we set the bulk viscosity of each fluid to be twice the respective shear viscosity. In 2-D this means and . This relationship is well within the parameter range for many biological gels [37]. The solvent shear viscosity is chosen to be a multiple of the network shear viscosity . In biological gels, is typically many orders of magnitude less than [37]. In the numerical tests that follow, we satisfy this relationship. Similarly, we chose the coefficient of friction to be a multiple of . The ratio of to defines a length scale. The smaller this length scale is compared to the length scale for the domain of the problem (which is 1 for our tests), the more the drag force will dominate the network viscous forces. We always choose the ratio of to to be much less than one so that the drag force affects the gel dynamics.

The link formation constant in (11) is chosen to be inversely proportional to the product of the polymer relaxation time and the maximum of the square of the initial network volume fraction:

| (52) |

The initial value for the elastic modulus is chosen according to

| (53) |

which is the steady state solution to (15) when the network velocity is zero. Plugging the equation for into this expression shows that controls the maximum initial value of the elastic modulus. The initial value for the components of the viscoelastic stress are set equal to zero, which corresponds to the steady state solution of (14) with zero network velocity. Table 1 summarizes how the gel parameters are chosen, while Table 2 summarizes how the initial values of the state variables are chosen.

Table 1.

Summary of the parameters of the gel model and any relationships used for defining these parameters in this study.

| Parameter | Description | Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 1 | |

| Network shear viscosity | Free | |

| Network second coefficient of viscosity | ||

| Solvent shear viscosity | Proportional to | |

| Solvent second coefficient of viscosity | ||

| Drag coefficient | Proportional to | |

| Inverse of the polymer relaxation time | Free | |

| Link formation constant | ||

| Maximum initial value of the elastic modulus | Free | |

| Osmotic pressure constant | Free |

Table 2.

Summary of the gel state variables and the initial values that are used in this study.

| Variable | Description | Initial condition |

|---|---|---|

| Network volume fraction | free (spatially varying) | |

| Solvent volume fraction | ||

| Viscoelastic stress tensor | ||

| Elastic modulus | ||

| Network velocity | 0 | |

| Solvent velocity | 0 |

The flow of the gel is driven by a body force which is chosen to drive a Newtonian fluid with a steady state velocity of

| (54) |

which corresponds to four vortices in each of the quadrants of the periodic box. This four-roll mill problem has been used in several other numerical studies of (single-phase) viscoelastic fluids [12,38–40] and creates an interesting model since it exhibits both rotational and elongational flow. The body force associated with (54) is determined by substituting into the Navier–Stokes equations. This requires choosing a value for the density and the viscosity, , in the Navier–Stokes equations. We set the density to unity and the value of as a weighted average of the network and solvent viscosities that are used in the gel simulations:

For a uniform initial volume fraction, this is the viscosity of the volume averaged velocity field for the four-roll mill. With these values the resulting body force is

| (55) |

In all the tests that follow, both fluids are initially at rest, so (55) is applied gradually with the modification

| (56) |

We apply this force to both phases by adding the weighted term to (16) and to (17).

A total of five tests are performed with the four different parameter sets listed in Table 3. The first two tests correspond to the gel behaving like a viscoelastic fluid. We vary the relaxation time and the initial elastic modulus in these tests to correspond to a “moderate” and “difficult” viscoelastic fluid. Here “difficult” refers to longer relaxation times (smaller ) which allow the stresses to build up and the fluid to exhibit characteristics similar to those of High Weissenberg number flows. In the remainder of the tests, the gel behaves like a viscoelastic solid and contains a large spatial variation in material parameters. We illustrate the elastic effects of the gel in the last two experiments by first stretching and compressing it according to the four-roll mill geometry and then letting the gel snapback when the background force is removed. Similar to the first two tests, we vary the relaxation time to correspond to a “moderate” and “difficult” viscoelastic solid.

Table 3.

Parameter values used for the test problems. See Tables 1 and 2 for the relationships defining the other parameters.

For the first three tests we perform a refinement study to measure the accuracy of the algorithm. First, we compute a numerical solution to the problem specified using a fine grid spacing of , or a 512-by-512 grid. We then simulate the model at lower resolutions and compare those results to the high resolution solution. Since the algorithm uses a staggered grid, the values at the high resolution grid do not align with the values of the lower resolution grids. The values from the high resolution grid therefore need to be interpolated to the lower resolution grids. We use bicubic interpolation. Additionally, in our refinement studies, we do not use variable time-stepping. Instead we fix the time-step to be proportional to the grid spacing such that the CFL condition (51) is always satisfied. For the first two tests we set for , while for the third test .

4.1. Uniform volume fraction: refinement study

The parameters for the first two tests are listed in the Set 1 and Set 2 columns of Table 3. The ratio of the two viscosities for these tests is considered high, while the ratio of to (which defines a length scale) is considered moderate.

In the first test, we set the initial elastic modulus to and the inverse of the polymer relaxation time to . This is a moderate value for . The simulation is run up to time . The network volume fraction and the two velocity fields at this time are displayed in the left column of Fig. 2. The elastic modulus and the viscoelastic stresses are displayed in the left column of Fig. 3. The results of a refinement study for these 6 state variables are displayed in the right columns of Figs. 2 and 3. These results indicate that the algorithm is converging as in each of the , and norms, which is expected since the solutions are smooth.

Fig. 2.

Test 1: Left column of (a), (b), and (c) displays the respective network volume fraction, network velocity, and solvent velocity at using the Set 1 parameters. Right column displays the relative errors in the solutions for the corresponding variable in the left column using various values of the grid spacing .

Fig. 3.

Test 1: Continuation of Fig. 2, but for the (a) elastic modulus, (b) trace of the viscoelastic stress, and (c) viscoelastic shear stress.

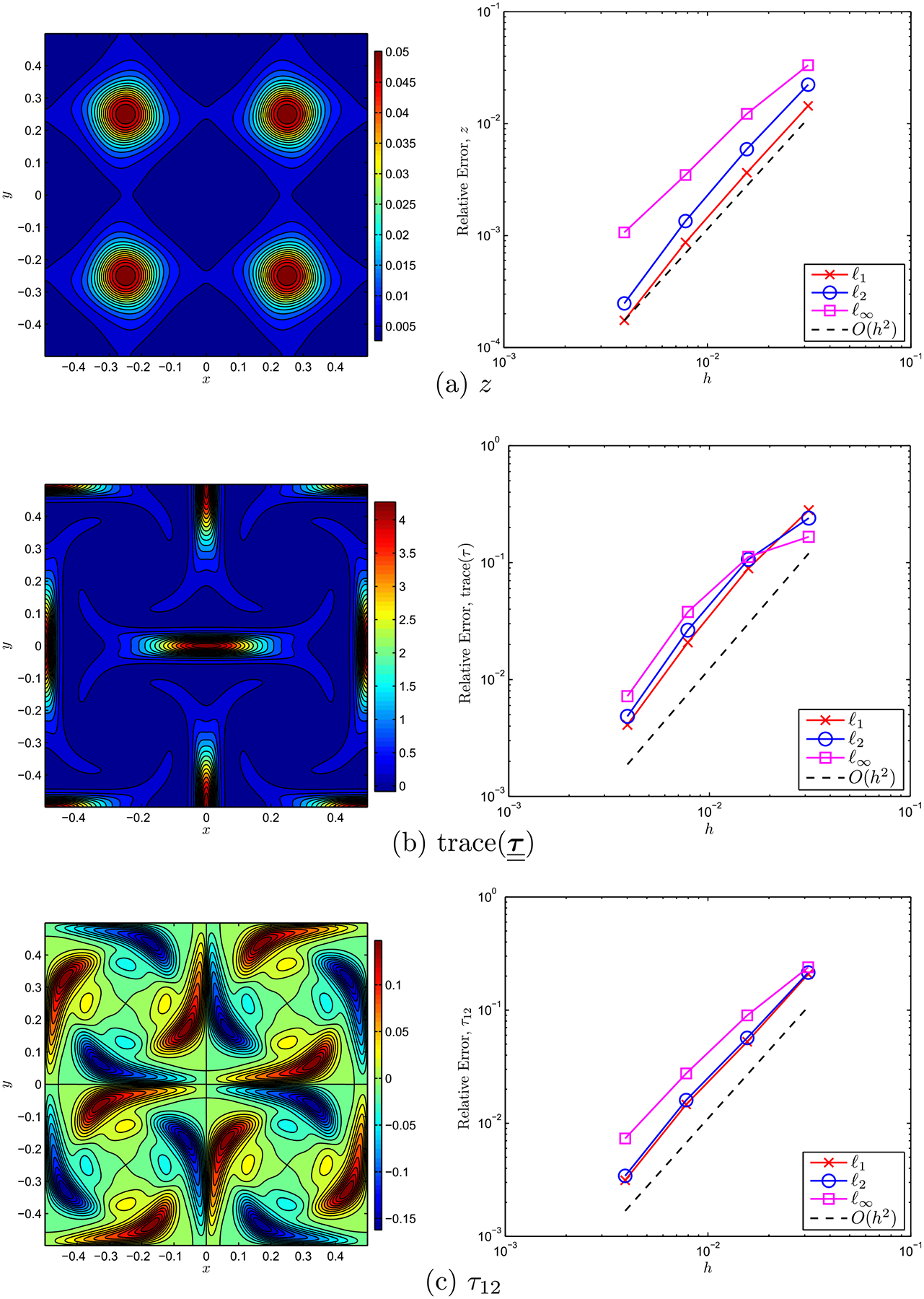

In the second test, we decrease and the initial elastic modulus to 0.01, which sets the initial polymer viscosity to be the same as the previous test. We can therefore see the effect of an increased relaxation time (decrease in ) without changing the polymer viscosity. This value of is considered difficult and the fluid exhibits characteristics of high Weissenberg number flow. The simulation is again run up to time . The network volume fraction and the two velocity fields are displayed in the left column of Fig. 4, while the elastic modulus and the viscoelastic stresses are displayed in the left column of Fig. 5. We see that the network volume fraction and the elastic modulus are much more concentrated at the centers of the four roll mill than in the first test. The speed of the two fluids is also higher than in the previous case (see the titles of the velocity field plots for the maximum speed). Finally, the trace and shear stresses are also larger and much more spatially concentrated. The results of a refinement study are displayed in the right columns of Figs. 4 and 5. The second order convergence results are very similar to Test 1.

Fig. 4. Test 2: Left column of (a), (b), and (c) displays the respective network volume fraction, network velocity, and solvent velocity at using the Set 2 parameters. Right column displays the relative errors in the solutions for the corresponding variable in the left column using various grid spacing .

Fig. 5.

Test 2: Continuation of Fig. 4, but for the (a) elastic modulus, (b) trace of the viscoelastic stress, and (c) viscoelastic shear stress.

As mentioned previously, it is difficult to define the classical non-dimensional numbers such as Weissenberg number used to classify standard viscoelastic flows for our two-fluid system. However, to put meaning to our use of the terms “moderate” and “difficult” viscoelastic flow, we can get an idea of what the Weissenberg number is for the two above experiments. The Weissenberg number is commonly defined as the ratio of the polymer relaxation time to the time scale of the fluid flow. To get a rough estimate of the Weissenberg number, we thus use (since our length scale is 1), where the velocities are taken at time . For the first experiment, and , giving a rough estimate for the Weissenberg number as 0.35, which is considered small. For the second experiment and , giving a rough estimate for the Weissenberg number as 10, which is considered high.

We conclude the discussion of these two tests by commenting on their behavior as the simulations are run for longer times. For the first test, all the forces come into balance and the system reaches a quasi steady-state. For the second, the viscoelastic forces continue to grow without bound along the and axes of the box. This behavior is similar to that of the Oldroyd-B model of single phase viscoelastic fluids at high Weissenberg number. For the four-roll mill problem, this model is known to develop singular structures in the stress fields [38]. Our numerical algorithm eventually breaks down as these singular structures develop in the gel model. This unphysical behavior is a common complaint of the Oldroyd-B model, which allows infinite extensibility of polymer chains. Other more physical models have been developed, which limit the extensibility of the polymer [19,41]. In the context of the polymer model used in the two-fluid gel model, the polymer extensibility can be limited by making a function of trace and , as done for a single-fluid in [12]. We will examine this type of model in a future study.

4.2. Concentrated volume fraction: refinement study

In the final refinement test, we set initial volume fraction to be concentrated in a circular region of radius 0.175 centered at the origin as displayed in Fig. 6. The exact form of the initial condition is

| (57) |

where . This initial condition has three continuous derivatives and the constants have been chosen such that . The remaining parameters for this test are listed in the column labeled Set 3 of Table 3. The ratio of the two viscosities is considered moderate in this case, while the ratio of to is considered high. The maximum initial polymer viscosity is now 5 times higher than in the first two tests. The simulation is run up to time , which is half the relaxation time. This test features sharp differences in material parameters and the gel exhibits behaviors of a viscoelastic solid.

Fig. 6.

Initial volume fraction (57) for the third refinement test.

The network volume fraction and the two velocity fields at the end of the simulation are displayed in the right column of Fig. 7 and the elastic modulus and the viscoelastic stresses are displayed in the left column of Fig. 8. The speed of the network is faster than in the previous two cases, while the speed of the solvent is much slower. This is a result of the increase in the drag coefficient. The trace of the viscoelastic stress is roughly of the same magnitude as in the second test, but it is much more spatially concentrated near the transition from low to high network volume fraction. The viscoelastic shear stresses are also much more spatially concentrated and larger than in the previous tests. The results of a refinement study are displayed in a similar manner to the previous tests in the right columns of Figs. 7 and 8. The rates of convergence for all variables, except the solvent velocity, are less than the previous tests. In the and norms, the convergence for the trace and shear stress now appears to be first order. This decrease in the convergence rate is expected since the solutions feature sharp gradients and the limiters used in (27) and (40) have been activated.

Fig. 7.

Test 3: Left column of (a), (b), and (c) displays the respective network volume fraction, network velocity, and solvent velocity at using the Set 3 parameters. Right column displays the relative errors in the solutions for the corresponding variable in the left column using various grid spacing .

Fig. 8.

Test 3: Continuation of Fig. 7, but for the (a) elastic modulus, (b) trace of the viscoelastic stress, and (c) viscoelastic shear stress. Note that only the region is displayed for the figures in the left column to better illustrate the structure of the variables near the concentration of network.

4.3. Concentrated volume fraction: snapback effect

In the remaining two tests, we further illustrate the robustness of the computational method by focusing on gels that exhibit characteristics of a viscoelastic solid. The tests are similar to the previous one in that we start with a concentrated polymer network centered at the origin and then stretch the gel along the -axis and compress it along the -axis according to the four-roll mill force. However, at time we turn off this background force and continue to run the simulation up to time . The parameters for both tests are set so that the polymer viscosity is relatively high and the relaxation times are relatively long, which make the gel have viscoelastic solid-like behavior. Thus, when the background force is removed the gel will snapback towards its original configuration.

For the first snapback test, we use the same parameters as the previous refinement test (Set 3 of Table 3). The relaxation time for these parameters is 5 and the background force is therefore turned off at half the relaxation time. Stills showing , and from the simulation at times , and 10 are displayed in Fig. 9. Initially, the polymer slowly expands radially outwards while the solvent correspondingly moves in towards the origin to fill the space, as can be seen in the still. The dynamics around this time are being driven by the osmotic pressure, which is designed to force the gel to mix. The effects of the background force do not dominate the dynamics until around . While the background force is turned off at , the polymer continues to be stretched because of inertial effects. This stretching stops around , (see the second row of Fig. 9) at which point the polymer slowly begins to snapback towards its initial state. The still at (see the third row of Fig. 9), shows that the polymer has moved closer to its initial state, but it is more swollen. The relaxation of the elastic stresses are now dominating the dynamics and network velocity has reversed direction as the polymer unwinds. In each of the four quadrants there are counter rotating vortices in the solvent. This pattern is formed by the complex interactions of the drag, pressure, and inertial forces on the solvent. At , the polymer has started to swell radially outwards from the configuration (see the fourth row of Fig. 9). This is an effect of the osmotic pressure, which again starts to drive the dynamics as the elastic stresses subside. The inertial effects on the solvent from the background force have diminished at this time and the solvent flow has reversed directions to correspond more to the network flow in the outer parts of the quadrants. The speed of the solvent is also now slower than the network.

Fig. 9.

Stills of , and from the first snapback test using the Set 3 parameters listed in Table 3. Red (dark) curves in velocity field plots correspond to the contour , while the yellow (light) curves correspond to the initial contour . (For interpretation of the references in colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In the second snapback test, we make the gel behave more like a viscoelastic solid by increasing the relaxation time by a factor of 10 from the previous test. All other values for the parameters are kept the same; see Set 4 from Table 3. Stills showing , and from the simulation at times , and 10 are displayed in Fig. 10. The dynamics of the gel for this parameter set are similar to the previous one up to approximately , as shown by comparing the first rows of Figs. 9 and 10. Beyond this time, however, the dynamics differ. For the gel with the longer relaxation, the network is not stretched out as far by the background force. Additionally, the stretching of the gel only continues up to approximately instead of as in the previous case as shown in the second row of Fig. 10. Still images of the gel at in the third row of Fig. 10 also show that the network has snapped back to a state that more closely resembles the initial condition than the previous test. Furthermore, the velocity has reversed direction at a much sooner time than the previous test. The final images in the fourth row of Fig. 10 show that the network has moved very little from its configuration and is much more concentrated than the previous test at . Finally, both the network and solvent velocities are higher and osmotic pressure is having little effect compared to the previous test.

Fig. 10.

Stills of , and from the second snapback test using the Set 4 parameters listed in Table 3. Red (dark) curves in velocity field plots correspond to the contour , while the yellow (light) curves correspond to the initial contour . (For interpretation of the references in colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We conclude this section with some comments on the performance of our numerical method for the two snapback tests. All the results presented were computed on a grid with spacing . Variable time-stepping was used as discussed in Section 3.5 and the simulation remained stable throughout the integration period. The tolerance for the multigrid-preconditioned GMRES solver for the momentum and incompressibility equations discussed towards the end of Section 3.2 was set to 10−8. Even with this relatively high tolerance, the solver performed exceptionally well. Fig. 11 displays time-traces of the number of iterations required for the solver for both snapback tests. The variations in the iteration count can partially be attributed to the use of smaller and larger time-steps at different times in the simulation and to good initial starting guesses based on the solution at the previous time-step.

Fig. 11.

Time traces of the number of iterations required for the iterative solver to reach a tolerance of 10−8) for the two snapback tests. The jump in iteration count from 3 to 6 in both tests corresponds to time when the background force is turned off.

5. Concluding remarks

Gels are important in many biological systems where they exhibit unique characteristics such as osmotic and active stresses. In many cases, the mechanics of these gels are appropriately described using a two-fluid model in which the gel is composed of a polymer network immersed in a fluid solvent. The resulting equations describing these models pose difficult challenges for simulation, and numerical methods have not previously been developed. We have presented the first computational technique for treating the whole coupled system of equations in two dimensions. The algorithm uses second order high-resolution methods for treating the scalar transport and tensor viscoelastic stress equations, and a second order finite-difference method for handling the momentum and incompressibility equations. For solving the large coupled linear system that results from the latter set of equations, we use a modified version of our previously developed preconditioned Krylov subspace method [9].

We have presented several numerical experiments using the four-roll mill to drive the gel motion. For smooth problems, our results confirm the computational algorithm is second order accurate in space and time. Additional numerical experiments presented show the method is also able to effectively handle sharp gradients that may develop in the solutions, but that the order of accuracy is decreased by the use of limiters to avoid oscillations. All experiments indicate the method is stable provided the variable time-step is restricted to satisfy an appropriate CFL-type condition. Finally, the five numerical experiments presented and further testing we performed separately show that the computational method is efficient, robust, and is able to handle gels with widely varying rheologies, ranging from characteristics of a viscoelastic fluid to those of a viscoelastic solid.

The polymer network in our model is treated as an Oldroyd-B fluid, which creates issues with the four-roll mill problem as this model allows singular structures in the stress field to develop [38]. In a future study we plan to extend our algorithm to treat more physical models for the network that limit the polymer extensibility, as in [12].

While our algorithm handles nonzero Reynolds number flows, in many biological applications the viscous terms dominate so that inertial terms are negligible [35–37,42,43]. Our algorithm can be modified to also handle these zero Reynolds number flow models. This would require removing the terms involving and from (26). In this case, the matrix that results is identical (up to boundary conditions) to the matrix from our previous study [9] where the multigrid preconditioned GMRES method was first developed.

Biologically relevant problems rarely occur in a bi-periodic box, but in much more geometrically complicated domains with boundaries. We have previously extended our method for simulating a viscous two fluid gel model to handle complex domains using a Cartesian grid embedded boundary method [11]. The extension of this technique to the viscoelastic two fluid gel model considered in this paper will also be pursued in a future study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NSF-DMS Grant 0540779 (GBW, RDG, JD, ALF), NSF-DMS Grant 0934581 (GBW), UCOP Grant 09-LR-03-116724-GUYR (RDG), and NSF-NIGMS Grant R01-GM090203 (ALF).

Appendix A. Viscoelastic constitutive equation

The viscoelastic stress arises from the deformation of a transient network of polymer chains. Links between the chains form at a rate that depends on the volume fraction of network, break at a constant rate, are transported with the network velocity, and are stretched by gradients of the network velocity. Let represent the concentration of links that connect the network at point to the network at point . This distribution satisfies the equation

| (A.1) |

where represents the formation rate of junctions, is the breaking rate, and it is assumed that the length scale of the chains is much smaller than the length scale associated with the fluid motion. If we assume that the force per link is , where is the stiffness coefficient, then the elastic stress within the network is

| (A.2) |

By multiplying Eq. (A.1) by and integrating over all , we obtain an equation for :

| (A.3) |

where .

The links form isotropically, and if there were no velocity gradient, then would remain isotropic. We assume that this stress from the presence of the links alone (i.e. not related to the deformation of the links) does not contribute to the viscoelastic stress. This isotropic stress is where satisfies the equation

| (A.4) |

We note that is proportional to the total number of links , and can be interpreted as the elastic modulus of the network. The viscoelastic stress is

| (A.5) |

By combining Eqs. (A.3) and (A.4), we see that satisfies Eq. (9).

Appendix B. Spatial discretization of the momentum equations

We use second order finite-differences on the staggered grid displayed in Fig. 1 to discretize the spatial derivatives in the momentum Eqs. (20) and volume-averaged incompressibility constraint (18). To make the presentation of the approximations more clear, we deviate from the subscript and superscript notation used in the main part of the paper. Here we use subscripts to indicate the location on the grid where the variables reside. Superscripts are used to differentiate between the network and solvent variables as well as the different components . We also use the overline notation discussed at the end of Section 3.1 to denote averages of certain variables.

The approximation of the first row of the semi-discrete Eq. (21) at ( is given by

| (B.1) |

while the approximation of the second row at is given by

| (B.2) |

The approximations for third and fourth rows of (21) corresponding to the network velocity are similar, but with the variables for the solvent replaced accordingly by the variables for the network. The network velocity equations include additional terms corresponding to the divergence of the weighted viscoelastic stress tensor and the gradient of the osmotic pressure. The approximation of that is included in the equation at is given by

| (B.3) |

while the approximation that is included in the equation at is given by

| (B.4) |

Finally, the volume average incompressibility constraint (22) is approximated at by

| (B.5) |

References

- [1].Cogan NG, Guy RD, Multiphase flow models of biogels from crawling cells to bacterial biofilms, HFSP J. 4 (2010) 11–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Doi M, Gel dynamics, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 78 (2009) 052001. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bird RB, Armstrong RC, Hassager O, Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, second ed., vol. 2, Wiley, New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Larson RG, Constitutive Equations for Polymer Melts and Solutions, Butterworth, Stoneham, MA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gado ED, Kob W, Structure and relaxation dynamics of a colloidal gel, Europhys. Lett 72 (6) (2005) 1032. <http://stacks.iop.org/0295-5075/72/i=6|a=1032>. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kroger M, Peleg O, Ding Y, Rabin Y, Formation of double helical and filamentous structures in models of physical and chemical gels, Soft Matter 4 (2008) 18–28, doi: 10.1039/B710147C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Suarez M-A, Kern N, Pitard E, Kob W, Out-of-equilibrium dynamics of a fractal model gel, J. Chem. Phys 130 (19) (2009) 194904, doi: 10.1063/1.3129247. http://link.aip.org/link/?JCP/130/194904/1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guy RD, Fogelson AL, A wave-propagation algorithm for viscoelastic fluids with spatially and temporally varying properties, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng 197 (2008) 2250–2264. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wright GB, Guy RD, Fogelson AL, An efficient and robust method for simulating two-phase gel dynamics, SIAM J. Sci. Comput 30 (2008) 2535–2565. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Du J, Fogelson AL, Wright GB, A parallel computational method for simulating two-phase gel dynamics on a staggered grid, Int. J. Numer. Meth. Fluids 60 (2009) 633–649. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Du J, Fogelson AL, A Cartesian grid method for two-phase gel dynamics on an irregular domain, Int. J. Numer. Meth. Fluids, in press, doi: 10.1002/fld.2445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fogelson AL, Guy RD, Immersed-boundary-motivated models of intravascular platelet aggregation, Comput. Meth. Appl. Mech. Eng 197 (2008) 2087–2104. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nonaka A, Trebotich D, Miller GH, Graves DT, Colella P, A higher-order upwind method for viscoelastic flow, Commun. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci 4 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Trebotich D, Colella P, Miller G, A stable and convergent scheme for viscoelastic flow in contraction channels, J. Comput. Phys 205 (2005) 315–342. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rubinstein M, Colby RH, Polymer Physics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fogelson AL, Continuum models of platelet aggregation: formulation and mechanical properties, SIAM J. Appl. Math 52 (1992) 1089–1110. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bird RB, Armstrong RC, Hassager O, Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, vol. 1, Wiley, New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Guy RD, Asymptotic analysis of PTT type closures for transient network models, J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 123 (2004) 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Phan-Thien N, Tanner RI, A new constitutive equation derived from network theory, J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 2 (1977) 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Owens RG, Phillips T, Computational Rheology, Imperial College Press., London, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gerritsma MI, Time dependent numerical simulations of a viscoelastic fluid on a staggered grid, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ascher UM, Ruuth SJ, Wetton BTR, Implicit-explicit methods for time-dependent partial differential equations, SIAM J. Numer. Anal 32 (1995) 797–823. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Peyret R, Spectral Methods for Incompressible Viscous Flow, Springer-Verlag, New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Benzi M, Golub GH, Liesen J, Numerical solution of saddle point problems, Acta Numerica 14 (2005) 1–137. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vanka SP, Block-implicit multigrid solution of Navier-Stokes equations in primitive variables, J. Comput. Phys 65 (1986) 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Trottenberg U, Oosterlee CW, Schüller A, Multigrid, Academic Press, London, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wesseling P, Oosterlee CW, Geometric multigrid with applications to computational fluid dynamics, J. Comput. Appl. Math 128 (2001) 311–334. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Saad Y, Schultz MH, GMRES: a generalized minimal residual algorithm for solving nonsymmetric linear systems, SIAM J. Sci. Comput 7 (1986) 856–869. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brüger A, Gustafsson B, Lötstedt P, Nilsson J, High order accurate solution of the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations, J. Comput. Phys 203 (1) (2005) 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gustafsson B, Lötstedt P, Göran A, A fourth order difference method for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations, in: Hafez MM (Ed.), Numerical simulations of incompressible flows, World Scientific Publishing, Singapore, 2003, pp. 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Colella P, Multidimesional upwind methods for hyperbolic conservation laws, J. Comput. Phys 87 (1990) 171–200. [Google Scholar]

- [32].van Leer B, Towards the ultimate conservative difference scheme, V. A second order sequel to Godunov’s method, J. Comput. Phys 32 (1979) 101–136. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Joseph DD, Fluid Dynamics of Viscoelastic Liquids, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [34].LeVeque RJ, Finite Volume Methods for Hyperbolic Problems, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cogan NG, Keener JP, Channel formation in gels, SIAM J. Appl. Math 65 (2005) 1839–1854. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Alt W, Dembo M, Cytoplasm dynamics and cell motion: two-phase flow models, Math. Biosci 156 (1999) 207–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dembo M, Harlow F, Cell motion, contractile networks, and the physics of interpenetrating reactive flow, Biophys. J 50 (1) (1986) 109–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Thomases B, Shelley M, Emergence of singular structures in Oldroyd-B fluids, Phys. Fluid 19 (2007) 103103. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Thomases B, Shelley M, Transition to mixing and oscillations in a Stokesian viscoelastic flow, Phys. Rev. Lett 103 (2009) 094501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Malaspinas O, Fin++tier N, Deville M, Lattice Boltzmann method for the simulation of viscoelastic fluid flows, J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 165 (23–24) (2010) 1637–1653. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bird RB, Dotson PJ, Johnson NL, Polymer solution rheology based on a finitely extensible bead-spring chain model, J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 7 (1980) 213–235. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dembo M, Mechanics and control of the cytoskeleton in Amoeba proteus, Biophys. J 55 (6) (1989) 1053–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].He X, Dembo M, On the mechanics of the first cleavage division of the sea urchin egg, Exp. Cell. Res 233 (1997) 252–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]