Abstract

Carbon emissions reduction is a global goal for climate change mitigation. Manufacturing is a key carbon emission emitter, with commensurate pressures on manufacturing enterprises to implement sustainable operations management (SOM). These pressures and responses have been studied for decades, with studies increasing significantly over the past decade. In this study, we identify 921 publications on this topic using the Scopus database. We recognize three categories for this research: internal sustainable manufacturing, external sustainable supply chain management, and competitive-cooperative relationships for environmental and economic performance improvement. The temporal analysis shows that corporate sustainable operations for carbon emissions reduction have four stages characterized by evolving research fields. Moreover, there has been an evolving geographical focus on the global dissemination of sustainable operations research. Notably, technological innovation, especially digital technologies, shows increasing promise. Three research directions see growth in interest: circular supply chain management with new business models, coordination mechanisms with multi-stakeholder involvement, and management-manufacturing (technologies) design interdisciplinary research. Furthermore, the literature review reveals that manufacturer SOM practices initially focused on internal practices and then shifted to external practices. SOM practices among manufacturers also showed a diffusion from developed to emergent economy countries. Finally, we include research propositions and directions for future research.

Keywords: Sustainability, Manufacturing, Supply chain, Climate change, Carbon neutrality, Greenhouse gas emissions, Literature review

1. Introduction

Organizations have encountered multiple pressures to implement sustainable operations management (SOM) [1]. Climate change concerns have made controlling carbon (and greenhouse gas) emissions a critical objective for SOM practices [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Many organizations have adopted SOM activities to mitigate carbon emissions, with greater growth after the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris.

The Sixth Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report showed that the industrial sector, including ores and minerals mining, manufacturing, construction, and waste management, contributed 20 Gigatons of CO2 emissions. These emissions account for 34% of the 2019 global carbon emissions [6]. Energy consumption is another major source of carbon emissions from manufacturing firms. Energy consumption reduction has been a major goal of environmentally conscious manufacturing (ECM) since early corporate sustainability investigations [7].

The global Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) has also motivated organizations to increase ambition and targets to combat climate change. From 2015 to 2020, companies adopting and monitoring targets cut emissions by 25% even when there was an increase of 3.4% in global energy and industrial emissions (https://www.un.org/en/climate-action/science-based-emissions-targets-heighten-corporate-ambition).

SOM activity and effort have evolved for carbon emission reductions as knowledge expands. This evolutionary understanding is important to help determine what foundations exist and how this foundational research can be strengthened.

SOM initially focused on internal sustainable manufacturing and later extended to sustainable supply chain management (SSCM), including green supplier management, reverse logistics, and eco-design [8]. For example, Huawei joined the Green Choice initiative supported by a non-governmental organization (NGO), the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), expanding its organizational environmental program scope to include greening its supply chains (https://www.huawei.com/en/sustainability/the-latest/stories/ipe-green-choice-initiative).

Organizations are also expanding their sustainability efforts on carbon neutrality to Scope 3 carbon emissions—managing carbon emissions beyond their organizational boundaries (Scope 1 and Scope 2-type emissions) to include suppliers and customers along their product life cycles [9,10]. For instance, in 2020, Apple announced its commitment to carbon neutrality for its supply chain by 2030 (https://www.apple.com/hk/en/newsroom/2020/07/apple-commits-to-be-100-percent-carbon-neutral-for-its-supply-chain-and-products-by-2030/). As this shift continues in carbon management, SSCM policies, practices, and programs increase in organizational prevalence and importance [11,12]. Nevertheless, managing emissions, especially Scope 3 emissions, makes organizational carbon management complex and difficult.

These important managerial and research evolutionary characteristics for carbon management across supply chains require further understanding of past and future research streams. Accordingly, this analysis provides an understanding of the foundational questions and directions of the research, setting the stage for determining what is known and what must be known. The evolution of research also provides insight into future projections and directions needed for effective organizational and supply chain management of carbon emissions with the goal of carbon neutrality. Another goal is to identify what researchers and proxy practitioners view as important challenges that require addressing. These challenges and research opportunities help set a critical research agenda for a responsible and carbon-friendly manufacturing industry supply chain.

To this end, this study explores how published SOM studies have evolved within carbon emissions reduction for the manufacturing industry sector. We evaluate selected publications from the Scopus database using a systematic literature review to achieve the research goal. Methodologically, bibliometric methods are applied to identify research trends and research clusters. Four stages of research development are identified, which provides insights into the current evolution of research for the decarbonization of supply chains. Future research directions are identified based on the review.

2. Data collection and methods

The evolution of research on how SOM relates to carbon-related sustainability performance is evaluated using a systematic literature review with supporting bibliometric analysis [13]. Bibliometrics help understand trends, keyword concentration, and relationships among literature sources and authors. More methodological details are now provided.

2.1. Data collection

The Scopus database is used to access the literature. Scopus is an electronic academic database owned and managed by Elsevier Publishers. Scopus has been widely used for literature reviews [6,7]. The database provides minimal quality for its collections, serving as an effective data source for our literature review research.

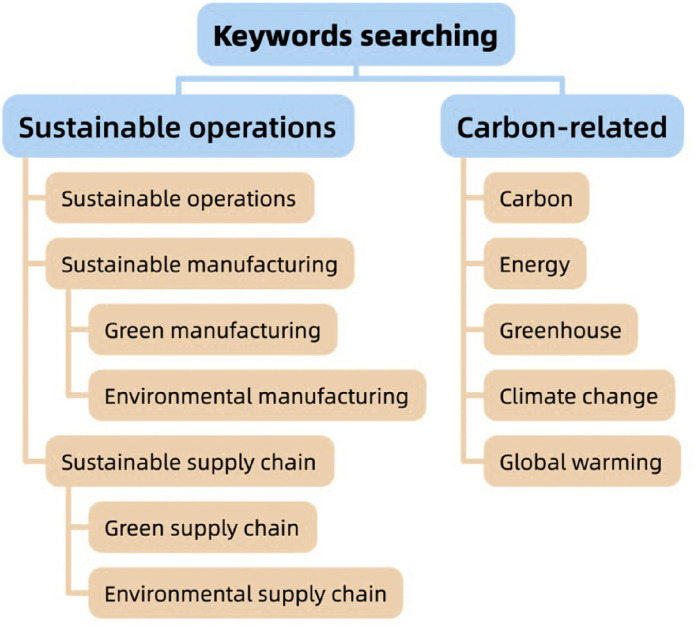

This study focuses on SOM research concentrating on carbon emissions management, including decarbonization, net-zero carbon emissions, and carbon neutrality. SOM and carbon emissions management and reduction studies continue to grow in several publications. Given the extant literature, we limited the search results to academic journal articles at the nexus of both fields. Two sets of keyword search terms were used: “sustainable operations management” and “carbon-related sustainability performance”. Fig. 1 illustrates the framework of the two sets of keywords.

Fig. 1.

Keywords searching framework.

Meanwhile, three levels of keywords are used for the general “sustainable operations management” category. The first level begins with one keyword, “sustainable operations”. The second-level keywords consider SOM in organizations. Using frequently used terms in previous studies, we selected three keywords: “sustainable manufacturing” [[8], [9], [10], [11]], “green manufacturing” [[11], [12]], and “environmental manufacturing” (or “environmentally conscious manufacturing”). The third level extends internal SOM to supply chains and includes three keywords: “sustainable supply chain” [[13], [14], [15], [16]], “green supply chain” [[11], [12], [13]], and “environmental supply chain”. To focus on the most relevant papers, given the thousands of potential publications, the keyword search was limited to the title field because we felt these papers would be most unambiguous within the scope of our search.

For carbon emissions management topics, we include “carbon” as the first direct keyword. Energy consumption is the primary source of carbon emissions, especially for manufacturing enterprises [17,18]. Thus, “energy” is the second keyword. In most studies, the term carbon emissions is used synonymously with greenhouse gases [19]. Therefore, we included the keyword “greenhouse”. Carbon emissions are important because of their influence on climate change and global warming, which supports the inclusion of two additional keywords: “climate change” and “global warming”. The search is limited to titles, keywords, and abstract fields.

Eventually, 851 papers were found using the search string: “((TITLE (“sustainable operations”) OR TITLE (“environmentally conscious manufacturing”) OR TITLE (“environmental manufacturing”) OR TITLE (“green manufacturing”) OR TITLE (“sustainable manufacturing”) OR TITLE (“sustainable supply chain”) OR TITLE (“green supply chain”) OR TITLE (“environmental supply chain”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“climate change”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (carbon) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (energy) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (greenhouse) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“global warming”))) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE,“j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ar”))”.

Additional papers from five high-ranking operations management journals were searched with “carbon-related” keywords. Some related papers in these operations management journals may not use the keywords we listed specifically for SOM. Many such papers may exist, but we narrowed the search to include highly reputable business and academic journals. Thus, our search set limits to five additional (University of Texas-Dallas ranking) UTD operations management-focused journals, including (1) Journal of Operations Management, (2) Management Science, (3) Operations Research, (4) Production and Operations Management, and (5) Manufacturing and Service Operations Management.

Energy is a common word widely mentioned in various studies; therefore, we removed the keyword “energy” in this search. Finally, 75 papers were identified with the test string: “(TITLE-ABS-KEY (“climate change”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (carbon) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (greenhouse) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“global warming”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (EXACTSRCTITLE, “Production And Operations Management”) OR LIMIT-TO (EXACTSRCTITLE, “Management Science”) OR LIMIT-TO (EXACTSRCTITLE, “Manufacturing And Service Operations Management”) OR LIMIT-TO (EXACTSRCTITLE, “Operations Research”) OR LIMIT-TO (EXACTSRCTITLE, “Journal Of Operations Management”)).” We reviewed all these 75 paper titles and abstracts; five papers were identified as irrelevant to the topic (three papers discuss transportation, one discusses farming, and the remaining discusses healthcare). Therefore, 70 papers were added to the previously identified 851 papers. The final study database includes 921 relevant publications.

2.2. Analysis methods

The main research method of this study is the systematic literature review with some bibliometric analysis to facilitate the review of the 921 papers. Initially, we analyze publication timelines, including observing publication quantity trends. Subsequently, the paper's content is evaluated. Co-word analysis with VOSviewer is used because of the large number of papers in the sample [20]. Co-word analysis identifies links of keywords within documents. Greater occurrence of similar keywords appearing in documents means greater connection. Co-word analysis helps to understand selection publication relationships, given the large number of documents. VOSviewer also helps to visualize the results. Section 3 presents the results of this analysis. The 921 papers are further categorized into topics across four stages, setting the stage for thematic analysis, and are presented in Section 4.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Publication trends

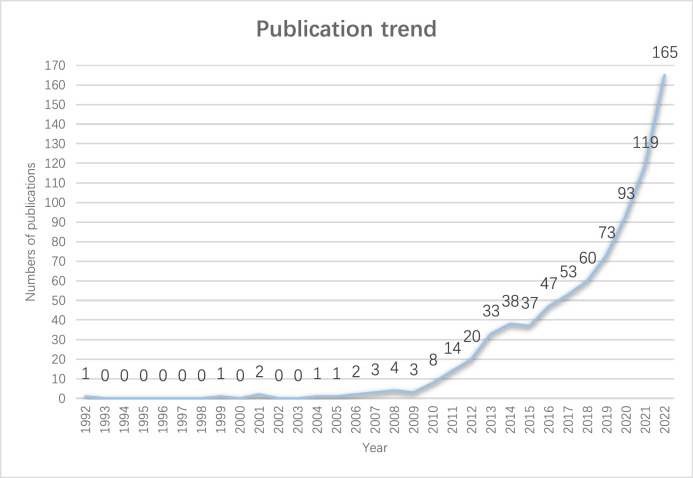

In total, 921 papers form the study's final dataset. Fig. 2 visually shows the publication trend across four temporal stages. The first paper appeared in 1992 [7]. No other papers fitting our search criteria were published in the following six years. The start of the twenty-first century commenced the first stage. Corporate SOM for carbon emissions reduction gradually attracted scholarly attention; approximately one to three papers were published yearly in the first decade, except for three years (i.e., 2000, 2002, and 2003) when no publications fitting our search criteria were recorded.

Fig. 2.

Quantity of publications in each year (until 2022).

The publication trend entered its second stage around 2010. The growth in numbers increased significantly at this stage. By the end of the second stage in 2013, the number of published papers had reached 11 times more each year up to 2009, increasing from 3 to 33. The third stage, a short one, showed some stabilization from 2013 to 2015, with approximately 35 papers published yearly. From 2016 until 2022, the publication trend entered its fourth stage—the second rapidly increasing publication stage. This last stage sees the number of publications growing geometrically, with 119 and 165 papers published in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

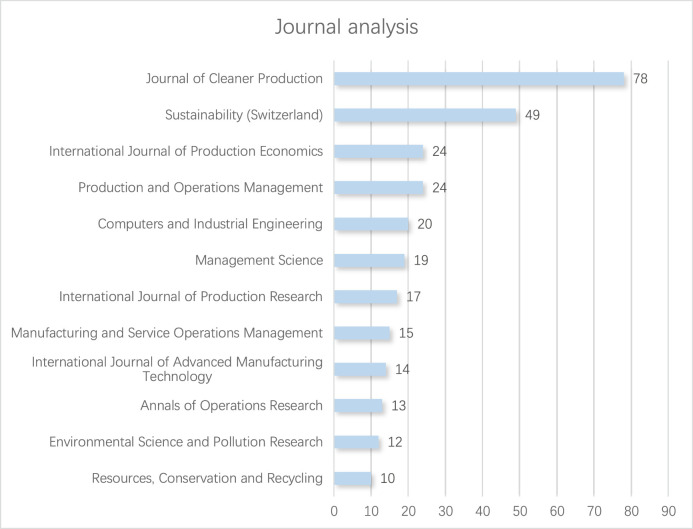

3.2. Journal analysis

The 921 study papers appeared in 346 different journals. This journal dispersion indicates a strong multi-disciplinary interest in SOM for carbon emissions reductions. Fig. 3 lists the top 12 journals that published 10 or more papers within the study dataset.

Fig. 3.

Journals with more than ten papers in the identified database.

The Journal of Cleaner Production (JCP), a journal focusing on green manufacturing, contributed the most studies with 78 papers. Following JCP, Sustainability (Switzerland), the International Journal of Production Economics (IJPE), Production and Operations Management (POM), and Computers and Industrial Engineering (CIE) contributed 49, 24, 24, and 20 papers, respectively. In the database, only these five journals published more than 20 papers. Seven other journals contributed more than ten papers, including Management Science (19), International Journal of Production Research (17), Manufacturing and Service Operations Management (15), International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (14), Annals of Operations Research (13), Environmental Science and Pollution Research (12), and Resources, Conservation and Recycling (10).

Although the 921 papers are scattered among many journals, the journals with more publications typically focus on sustainability or operations management. This result is not surprising and fits the two sets of selected keywords.

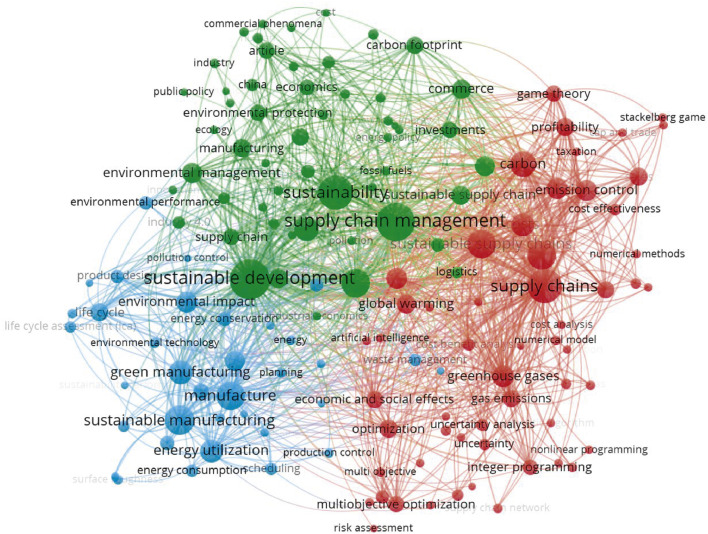

3.3. Keywords analysis

A co-word analysis was conducted to analyze the topics across the 921 papers. After adjusting the parameters to present the results (Layout Attraction: 1; Layout Repulsion: 0; Clustering Resolution: 0.8; Clustering Min. cluster size: 1), Fig. 4 was created. The keywords are divided into three clusters, which have significant overlaps. Nonetheless, unique characteristics exist across the three clusters.

Fig. 4.

Co-word analysis.

The blue cluster mainly focuses on green manufacturing and environmental impact assessment of manufacturing. For example, the keywords “life cycle assessment (LCA)” and “life cycle” reflect a primary methodological approach to evaluating environmental impacts. Keywords such as “planning”, “scheduling”, and “managers” also indicate that the papers explore manufacturing-operations issues.

The keywords “global warming”, “carbon”, “greenhouse gases”, and “costs” appear in the red cluster, representing environmental relationships to the manufacturing industry. Moreover, the scope of the red cluster is not limited to production; it further extends to the supply chain level. The three largest keyword nodes in the red cluster are “supply chains”, “green supply chain”, and “sustainable supply chains”. Methodologically, the red cluster also includes formal analytical methodologies that include many optimization models rather than predominant environmental assessment tools as those in the blue cluster.

The green cluster paper topics appear to be related to general sustainability and supply chain topics. Keywords widely include (green) supply chain management, sustainable development, and sustainability. An important large node between “sustainable development” and “sustainability” is “green supply chain management”, and this term is extremely long to be displayed in Fig. 4. Broadly speaking, the green cluster emphasizes achieving sustainable goals that reduce carbon emissions through corporate sustainable operations management. Under this broad topic, some key countries (e.g., “China” and “India”.) and some key directions (“circular economy” and “industry 4.0”) also appear as general categories. These additional topics are more recent.

4. Research development and future directions

As observed in the previous section, the trend of publications on corporate SOM for carbon emission reduction can be divided into four periods. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4, SOM for carbon emissions reduction publications cluster into green manufacturing, sustainable supply chain management, and sustainability-targeted analysis. We now provide insight into research development and directions using these results.

4.1. Evaluating the research development stages

In the earliest development stage (1992–2009) (see Section 3.1 for the description of developmental stages), published studies focused on sustainable manufacturing. In the second development stage (2010–2014), the concept of SSCM emerged as a critical practice for carbon emissions reduction. During these two initial stages, energy-related issues with a predominately input resource focus were central to most research. Although global warming, manufacturing, and supply chains are global, most publications occurred in Western nations, specifically the USA, the UK, and Germany [21].

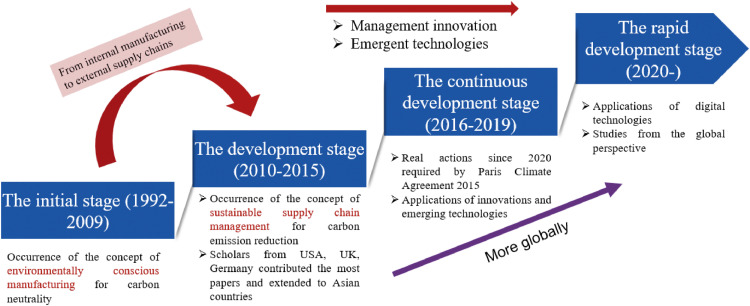

Innovations and emerging technologies became more pronounced during the third publications stage (2015–2019). Since 2020, digital technologies and global SSCM emerged as major research streams in the field. These globalization and technological issues provided a greater context for Chinese scholars to increase their contributions significantly. Fig. 5 summarizes these four research development stages.

Fig. 5.

Evolution of research development stages.

We now delve more deeply into additional content analysis of publications within these stages.

Stage 1: Initial stage and introduction of the concept of environmentally conscious manufacturing for carbon neutrality (1992–2009).

The earliest publication in our data set was published in 1992 [7], and this publication introduces environmentally conscious manufacturing (ECM) and stipulates that ECM can enhance energy conservation. The Energy Policy Act of 2005, introduced as a US regulatory measure, required enterprises to improve energy efficiency. Thus, energy-related climate policy resulted in corporate risks and needed careful investigation, including investigation related to carbon emissions [22]. One study initiated ECM research directions for carbon neutrality [2]. The US regulatory policy was not the only influence on ECM and carbon neutrality. European mandatory emission trading schemes in the United States also represented risks for carbon emissions management as part of ECM and general organizational contexts [23].

Stage 2: Emergence of sustainable supply chain management for carbon emissions reduction (2010–2015).

After 2010, SOM studies on carbon emissions management extended to a broader product life cycle management approach, lengthening and broadening considerations beyond internal ECM practices [24]. Studies further explored broader closed-loop [25] and supply chain network design [19,20] for carbon emissions reduction. Whether and how green supply chain management (GSCM) can balance environmental gains, including energy savings and emissions reductions, with economic benefits were examined empirically [4]. This evaluation assessed various conflicts between environmental and business goals at multiple organizational planning (strategic and tactical) levels [26]. Topics that started emerging from the closed-loop perspective included practices such as remanufacturing [27]. Part of this balance discussion included improving eco-efficiency [28] and engaging supply chains [29] as effective SOM approaches for carbon emission reduction.

A review study published in 2014 [26] evaluated sustainable manufacturing as a critical discipline for the twenty-first century. In this evaluation, which focused on carbon emissions, government programs, and LCA techniques and standards, various product design issues arose [30]. This situation meant greater concerns with managing external pressures and internal capabilities and tools to help address SOM carbon emissions reduction. This joint perspective became more popular during this period as operations management researchers more carefully evaluated regulatory regimes, institutional pressures, and organizational responses related to building resources and capabilities. This perspective is unlike earlier aspects that primarily considered internal organizational capabilities development.

During this second stage, there were calls for extending GSCM to SSCM by including social aspects and calls for mathematical modeling studies, expanding the focus from green to sustainable [31]. Part of this evaluation and breadth of study expansion included the explicit consideration of social costs associated with carbon emissions [32]. Investment in energy technology [33] and eco-design for product use in sustainable manufacturing [34] were reinforced as solutions for carbon emissions reduction.

Looking back at sustainable operations [35], evolution occurred during this stage for the period 1988–2015. This review found that energy technology plays an essential role in reducing carbon emissions. Furthermore, during the second period, enterprises in Europe and North America ramped up outsourcing manufacturing to Asia. This fundamental shift may explain why supply chain management emerged as a critical issue in managing carbon reduction. Similar to our early findings, the USA, the UK, and Germany contributed the most publications on this topic, while Asian scholars emerged as leading SOM scholars during later periods [21].

Stage 3: Furthering the understanding of innovations and emerging technologies for carbon emissions reduction (2016–2019).

The Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 had 178 country signatories who agreed to take real actions on climate reduction beginning in 2020. Owing to this global agreement and the emergence of technologies, manufacturing enterprises sought technological innovations to support their SOM practices. Consequently, studies on SSCM in Stage 3 extended to be more focused on carbon emissions reduction and eco-innovation application. This period from 2016 to 2019 and up to 2020 played a critical role in countries and organizations ramping up carbon emissions reduction efforts. The Paris Agreement led to stricter climate policies. Thus, GSCM became an important spotlight as an enterprise action to balance carbon emission reduction with economic objectives, building on some earlier but not as intensive studies [[27], [28], [29]].

During this third stage, carbon market uncertainties arose as a significant focus (eventually, net-zero carbon emissions and carbon neutrality entered the lexicon, with carbon markets and taxes more fully representing the earlier terminology) [34]. These uncertainties were integrated into sustainable manufacturing investment decisions, among other operational and business concerns. This area of uncertainty was also represented as a continuation of earlier stage 1 and 2 research where energy management and electricity pricing uncertainties for sustainable manufacturing remained a concern [36].

Eco-innovations [37] and supply chain design [38] increased in emphasis as these activities were deemed necessary for achieving a low-carbon environment through SSCM implementation. Simultaneously, SOM studies expanded their focus from manufacturing enterprises to service companies [39]. Strategic investment in renewable energy in these contexts was also explored [36]. Innovation and technologies meant that collaboration mechanisms across supply chains [40] and technology choice models [41] were introduced, especially those that considered government policy incentives.

The pressures from the Paris Accords also led to more emphasis on climate change supply chain risks [42], where coordination of supply chain members increased in importance as the shift to scope three (supply chain) emissions occurred [3]. Information-based technological approaches for SOM studies in carbon emissions reduction were part of the greater technological focus. For example, internet-of-things (IoT) technologies were employed for real-time carbon emission data collection along with bill of material (BOM)-based LCA evaluations for carbon emissions for evaluating product life cycles [42]. Moreover, the design implications of extended producer responsibility regulations were investigated [43].

In addition to collaboration across supply chain partners, coopetition-collaboration among competitors in green supply chains and energy-saving regulations became an innovative direction for sustainability and carbon emissions reduction goals [44]. Coopetition for sustainability and carbon emissions reduction may not necessarily be seen from anti-monopoly and anti-trust concerns, given that the ultimate goal is a social and environmental benefit. For example, the consolidation of the logistics capacity of competing companies and coopetition in the supply chain transportation area in a retail setting may benefit overall carbon emissions reduction from a shipping perspective [45].

Analytical models also saw greater emphasis. One of the more popular approaches is game theoretic analytical modeling, which investigates regulatory mechanisms, SOM, and carbon emissions reduction. One such exemplary study is an evolutionary game model that explores the dynamic relationship between governments and manufacturing due to climate change pressures [46].

As mentioned earlier, Scope 3 emissions increased in importance during this period. Some of this popularity can be traced to the Carbon Disclosure Project's (CDP's) Climate Change Supply Chain initiative. The Scope 3 indirect greenhouse gas emissions result from the sourcing and distribution of goods and services [47]. The CDP database has proven valuable for various research streams that incorporate strategic and operational empirical studies [48].

Stage 4: Greater emphasis on digital technologies and global perspectives (2020-current)

Real actions required by the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015 meant that SOM research in 2020 increased in practical, actionable issues related to carbon emissions reduction. Over half of the publications (520 out of 921) appear during this latest and relatively short stage, fully showing the importance of raised global agreements and awareness of climate change concerns.

The topics during this latter stage had threads like those in earlier stages. A major difference is the rapid increase in publication quantities, although they covered topics similar to those in previous stages. This ramp-up is due to the implementation of many technologies and interest because of the Paris Accords and the outcomes. Enterprises implemented SOM practices for various reasons ranging from improving production efficiency (business reasons) to reducing carbon emissions (environmental reasons) [5]. Similar to Stages 2 and 3, technology investment and policy intervention are represented as key contexts for sustainable operations studies [49].

There was a shift in emergent technologies and innovation types. For example, multi-stakeholder technologies such as blockchain and Industry 4.0 started seeing research on their integration with SSCM [[26], [27], [28]]. Geographic information systems (GISs) also became important within green supply chain models to account for carbon price uncertainty [50]. Agile capability, supported by technologies and new processes, also becomes critical for enterprises to implement sustainable operations effectively [51]. Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI)-based technology have provided automated learning and improvement environments to overcome many barriers associated with complex SSC networks [52].

As mentioned in the third stage discussion, globalization continued its emergence. Institutional pressures have driven enterprises to elicit carbon transparency in global supply chains [53]. Thus, SSCM matured further along a global perspective, considering cross-regional sustainable supply chains [54].

Research has also shown greater nuances associated with economic gains of carbon abatement as terms such as net-zero and carbon-neutral terminology became more prevalent in studies with significant differences for global firms [55]. Firm decisions for controllable carbon emissions were linked to marketing and consumer behavior as consumer preferences for low-carbon products emerged as societal institutional norms shifted. Governmental regulation and efforts are major institutional drivers, and consumer awareness and demands have also increased [56].

Governmental intervention and institutional pressure are critical factors for enterprises to implement carbon reduction-targeted sustainable operations [55]. Beyond mandatory requirements, enterprises have voluntarily disclosed carbon-related information about their suppliers, expanding the scope of reporting [57]. Retailers like Walmart became supply chain leaders and have been motivated to induce their suppliers to abate their emissions through net-zero initiatives [58]. Sustainable operations efforts for carbon emissions expanded across organizational functions such as green human resource management [59].

4.2. Future research directions

SOM carbon emissions reduction studies have seen significant shifts over the past few decades. Research on SOM carbon emissions reduction is growing in many directions. Three emergent areas show considerable promise: new business models along the social innovation of circular economy (circular supply chain management), expanding considerations and coordination of multiple stakeholders, and interdisciplinary research.

(1) Circular supply chain management and new business models

Circular supply chain management (CSCM) incorporates forward and reverse supply chains [60]. CSCM is central to circular economy practices and aims to increase the recovery rate and the level of end-of-life products and materials. CSCM as a whole system can reduce the need to consume virgin components and materials, which typically consume large amounts of energy, resulting in greater carbon emissions.

CSCM requires redesigning supply chains and relationships among supply chain members. CSCM challenges exist, including market cannibalization between circular and new products, the impact of fashion changes, the standards and regulations-related challenges (taxation and policy instruments misalignment, metrics, lack of standards), cultural issues specific to circular systems, data privacy and security at the end-of-use, and the willingness to pay for reclaimed products [61].

To implement CSCM successfully, new business models are necessary, such as a shift from product ownership to leasing and product-service CSCM business models. Multi-level cooperation and collaboration between firms along supply chains should be explored to overcome the difficulty associated with CSCM business models. A broader question is whether and when CSCM and its business models can contribute to SOM carbon emissions reduction. It may be “typical” or expected, but sometimes, depending on the context (e.g., material, product, industry, location), reductions in carbon emissions may not occur. Thus, careful examination is necessary to determine when CSCM results in carbon emissions reduction.

Based on this brief discussion, we introduce two research propositions:

Proposition 1–1

Manufacturers with a higher consideration and implementation level of circular supply chain management can better reduce carbon emissions.

Proposition 1–2

Innovative business models and materials, industry, and product characteristics can moderate or mediate the relationship between circular supply chain management and carbon emissions reduction.

(2) Coordination mechanisms with multi-stakeholder involvement

One common theme across the multiple stages of research development is the integral role of governments. Governments developed regulations and policies to motivate or require enterprises to implement SOM practices for carbon emissions reduction. These aspects have been intensively studied. NGOs are also more recent but key stakeholders in SOM. For example, NGOs may disclose information about carbon emissions from enterprises, especially when they identify violations and emission levels. These disclosures influence other concerned stakeholders, such as communities, consumers, and investors. These disclosures can incur reputational impacts and affect stock prices for publicly traded enterprises, even potential longer-term market share loss.

Disclosure of sustainability-related violations by NGOs can affect the reputation of firms and even their customers. Consequently, understanding such a loss, many enterprises have paid considerable attention to the role of NGOs and balanced reputation loss and costs associated with SOM efforts [62].

More enterprises have pursued collaboration or coordination with multiple stakeholders, such as governments, NGOs, and consumers. In this case, competitors, through coopetition efforts, have also collaborated to manage carbon emission-related issues to meet requirements from their common stakeholders. However, the various influences and relationships across these multiple stakeholders and the role of adopting SOM carbon emission reduction practices, whether they are in an organization, across the supply chain, or globally, require investigation. More studies are necessary to explore cooperation-competition relationships among enterprises and coordination mechanisms by different stakeholders, especially those that influence SOM practices for carbon emission reduction. It also calls for more transdisciplinary research involving practitioners, academics, and multiple disciplines [63].

Based on these observations, we introduce two general research propositions.

Proposition 2–1

The involvement of external stakeholders beyond supply chains, such as governments, NGOs, and consumers, can influence and moderate the relationship between sustainable operations management and carbon emission reduction. The transdisciplinary nature of this work will be more effective when multiple stakeholders collaborate.

Proposition 2–2

The involvement of external stakeholders beyond supply chains, such as governments, NGOs, and consumers, is a crucial step (mediation) in the role of sustainable operations management and carbon emission reduction.

(3) Management- technologies-design interdisciplinary research

In addition to management, cross and transdisciplinary studies that include technologies and design as well as systems thinking are necessary to guarantee the effectiveness of SOM efforts for carbon emissions reduction. To meet regulatory pressure from governments or requirements from other stakeholders, manufacturing enterprises traditionally try to improve their energy efficiency to reduce carbon emissions. Research has shown that in addition to management action, technologies and innovations are necessary to help reduce carbon emissions in the manufacturing industry. Digital technologies such as AI, blockchain, cloud computing, and big data can be further applied in SOM for carbon emissions reduction by facilitating data collection and sharing, information traceability and transparency, and data processing.

In some cases, facilities, processes, and products must be redesigned. Beyond improving energy efficiency, avoiding energy waste (unnecessary energy consumption) can be even more critical to reducing carbon emissions for enterprises [14]. However, technologies and redesign have become necessary to identify and eliminate this energy waste. Cross- and transdisciplinary management-technology-design systems thinking approaches are underdeveloped to implement SOM effectively for carbon emission reduction and need further research and development to determine the most effective systems to develop and adopt.

Emergent technologies, including new green technologies for energy production and digital technologies for data collection and analysis, have been applied to SOM practices among enterprises. Future research must explore design approaches and their integration with approaches and tools of management and technologies, especially with the growth of multi-stakeholder and integrated technologies related to Industry 4.0. These technologies may help in some instances but may hinder the goal of carbon emission reduction at other times, and research is required [64].

Given this discussion, we introduce two research propositions.

Proposition 3–1

Technology applications influence the relationship between sustainable operations management and carbon emissions reduction. There is likely a contingency in whether the technologies help.

Proposition 3–2

Eco-design or design for environmental technology and multi-stakeholder technology can moderate or mediate the relationship between sustainable operations management and carbon emission reduction.

5. Conclusion

Regulatory and reputational pressures have caused manufacturing enterprises to consider serious efforts to reduce carbon emissions for themselves and along their upstream and downstream supply chains (the IPCC Scope 3 emissions). SOM has become increasingly important for enterprises in terms of carbon management and carbon neutrality. Using the results of the systematic literature review and supporting bibliometric analysis of 921 publications, this research contributes to the body of knowledge by identifying three clusters of SOM research. It reveals four development stages for SOM research evolution.

The history of these efforts from an SOM perspective can be traced back to 1992 and likely earlier. During our study, manufacturing enterprises extended their SOM efforts from internally focused green manufacturing initiatives to externally and globally focused SSCM. The first stage (1992–2009) sought to define the role of environmentally conscious manufacturing with less emphasis on carbon neutrality. The second stage (2010–2015) saw the term environment shift to environmental sustainability with an extension to sustainable supply chains, expanding the scope to multiple organizations. What occurred during this period is an extension to the term sustainability, causing additional confusion and complexity regarding the topic. Social issues began to play a more prominent role as the overlap with corporate social responsibility became a more important topic. However, the concern may be that considering social constraints such as equity and inclusiveness may result in limiting initiatives, although justice concerns will be served. These tradeoffs became more prevalent and a concern.

Since 2016, emergent technologies, especially digital technologies, have emerged to facilitate SSCM for carbon emissions tracing, analysis, and control. SOM has also gained attention as a globally focused concept. Multinational enterprises have implemented SOM practices in their supply chains and globally, and these areas have been more effectively studied, although several research questions remain. For example, the issue of embedded carbon footprints and international trade has started to be investigated further.

SOM studies have historically focused on the USA, the UK, and Germany before 2015; China and India-based research has significantly increased recently. The need for developing country voices requires further enhancement. Moreover, in 2015, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were introduced and adopted. This year, the SDGs brought together issues related to climate change, as well as developing country and international concerns. SDGs contributed to growth in issues of global equity and inclusion and became more prominent from a policy perspective, with academic scholarship following closely.

SOM studies have been published across policy, environmental management, and operations management journals. Extending from forward to reverse supply chain management, CSCM has evolved as an approach for innovative carbon management, while new business models are necessary for collaboration among supply chain members. This issue has become even more prevalent as circular economy and carbon emissions relationships have started to see increased investigation. Propositions 1–1 and 1–2 must be investigated as the co-benefits associated with the circular economy can help multiple environmental benefits, including material resource depletion mitigation, biodiversity and species management, and carbon emissions reductions. These co-beneficial environmental outcomes relationships and investigating propositions can provide significant insights into managing carbon emissions and practices.

Stakeholders beyond supply chain actors, such as governments, NGOs, and consumers, play more critical roles in SOM. This development of multiple stakeholder involvement means more co-creation and cooperation in the research and development of solutions along a transdisciplinary route. Additionally, SOM needs further interdisciplinary integration of management, technology, policy, and design to achieve carbon emissions reduction. Future research can extend to broader boundaries, more stakeholders, and other disciplines for carbon emission reduction through SOM. It will be interesting to see if these more complex cooperative research systems evolve in a world where specialized reductionist research is the major approach. Theoretically, as social networks and institutional relationships expand, corporate and operational strategies will likely evolve as well. In this case, regulatory relationships between long-term policies and organizational operational SOM decisions can be evaluated.

The technological dimensions become even more critical as the third major set of propositions serves institutional roles by setting new norms of communication. Thus, stakeholder voice will become more critical. Multistakeholder technologies can support this communication among social networks critical for carbon reduction and is an avenue for future research and investigation. Part of this multiple-stakeholder technology involvement means capturing data, performance, and outcome data that can be contributed to and used by stakeholders. The development of architectures and the involvement of these multiple stakeholders will be critical for advancement, given the integration and issues of inclusiveness and equity. A measurement for evaluating progress and not merely greenwashing of initiatives is necessary. Given the continued increases in carbon emissions, many studies for improvement have yet to make a true impact. This situation calls for determining the effect of research and developments to determine if the difference is made in policy and practice.

This study focuses on exploring SOM for carbon emissions reduction in manufacturing industries. Manufacturers also produce carbon emissions through transportation, and logistics can be critical for low-carbon SOM among manufacturers. Thus, understanding SOM efforts in transportation and logistics activities, as well as their linkage to SOM, is worthy of future research. Finally, aside from reducing carbon emissions, enterprises have struggled to improve other environmental and social performance outcomes. Balancing these different organizational goals is another important direction in exploring practical effort and research domains.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72221001) and Major Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (72192833, 72192830).

Biographies

Duanyang Geng got his Ph. D. from the Center for Industrial Sustainability, Institute for Manufacturing (IfM), University of Cambridge, and he is an assistant professor in School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. His research focuses on energy waste, energy management, etc.

Qinghua Zhu is a chair professor in Antai College of Economics and Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Her research focuses on sustainable operations management, corporate low-carbon management.

References

- 1.Kleindorfer P.R., Singhal K., Van Wassenhove L.N. Sustainable operations management. Prod. Oper. Manage. 2005;14(4):482–492. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbett L.M. Sustainable operations management: A typological approach. J. Ind. Eng. Manage. 2009;2(1):10–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brusset X., Bertrand J.L. Hedging weather risk and coordinating supply chains. J. Oper. Manage. 2018;64:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Q., Geng Y., Sarkis J., et al. Evaluating green supply chain management among Chinese manufacturers from the ecological modernization perspective. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011;47(6):808–821. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartal A., Rodríguez M., Vázquez X.H. From efficiency-driven to low-carbon operations management: Implications for labor productivity. J. Oper. Manage. 2020;66(3):310–325. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhakal S., et al. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA: 2022. Emissions Trends and Drivers in IPCC 2022. [Online]. Available. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watkins R.D., Granoff B. Introduction to environmentally conscious manufacturing. MRS Bull. 1992;17(3):34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Q., Sarkis J. Relationships between operational practices and performance among early adopters of green supply chain management practices in Chinese manufacturing enterprises. J. Oper. Manage. 2004;22(3):265–289. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song S., Lian J., Skowronski K., et al. Customer base environmental disclosure and supplier greenhouse gas emissions: A signaling theory perspective. J. Oper. Manage. 2024;70(3):355–380. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song S., Dong Y., Kull T., et al. Supply chain leakage of greenhouse gas emissions and supplier innovation. Prod. Oper. Manage. 2023;32(3):882–903. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar B., Sarkar M., Ganguly B., et al. Combined effects of carbon emission and production quality improvement for fixed lifetime products in a sustainable supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021;231 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadav D., Kumari R., Kumar N., et al. Reduction of waste and carbon emission through the selection of items with cross-price elasticity of demand to form a sustainable supply chain with preservation technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;297 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitchenham B. Procedures for undertaking systematic reviews. Joint Technical Report, Computer Science Department, Keele University (TR/SE-0401) and National ICT Australia Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng D., Evans S. A literature review of energy waste in the manufacturing industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022;173 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geng D., Feng Y., Zhu Q. Sustainable design for users: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27(24):29824–29836. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nujoom R., Mohammed A., Wang Q. A sustainable manufacturing system design: A fuzzy multi-objective optimization model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25(25):24535–24547. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seth D., Rehman M.A.A. Critical success factors-based strategy to facilitate green manufacturing for responsible business: An application experience in Indian context. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022;31(7):2786–2806. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu P., Zhou Y., Zhou D.K., et al. Energy Performance Contract models for the diffusion of green-manufacturing technologies in China: A stakeholder analysis from SMEs’ perspective. Energy Policy. 2017;106:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolai M., Manna A.K., Mondal S.K. Sustainable manufacturing model with considering greenhouse gas emission and screening process of imperfect items under stochastic environment. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2022;8(3):93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zupic I., Čater T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods. 2015;18(3):429–472. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu X., Niu Z., Yeh M.K. Research trends in sustainable operation: A bibliographic coupling clustering analysis from 1988 to 2016. Cluster Comput. 2016;19(4):2211–2223. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker E. Increasing risk and increasing informativeness: Equivalence theorems. Oper. Res. 2006;54(1):26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmona R., Hinz J. Risk-neutral models for emission allowance prices and option valuation. Manage. Sci. 2011;57(8):1453–1468. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barreto L.V., Anderson H.C., Anglin A., et al. Product Lifecycle Management in support of green manufacturing: Addressing the challenges of global climate change. Int. J. Manuf. Technol. Manage. 2010;19(3–4):294–305. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quariguasi Frota Neto J., Walther G., Bloemhof J., et al. From closed-loop to sustainable supply chains: The WEEE case. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010;48(15):4463–4481. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Albuquerque G.A., Maciel P., Lima R.M.F., et al. Strategic and tactical evaluation of conflicting environment and business goals in green supply chains. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. Pt. A. 2013;43(5):1013–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fatimah Y.A., Biswas W., Mazhar I., et al. Sustainable manufacturing for Indonesian small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): The case of remanufactured alternators. J. Remanuf. 2013;3(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aflaki S., Kleindorfer P.R., De Miera Polvorinos V.S. Finding and implementing energy efficiency projects in industrial facilities. Prod. Oper. Manage. 2013;22(3):503–517. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jira C., Toffel M.W. Engaging supply chains in climate change. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manage. 2013;15(4):559–577. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogue R. Sustainable manufacturing: A critical discipline for the twenty-first century. Assem. Autom. 2014;34(2):117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandenburg M., Govindan K., Sarkis J., et al. Quantitative models for sustainable supply chain management: Developments and directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014;233(2):299–312. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng. S.W. Hung S.C. A strategic decision-making model considering the social costs of carbon dioxide emissions for sustainable supply chain management. J. Environ. Manage. 2014;133:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.11.023. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker E., Solak S. Management of energy technology for sustainability: How to fund energy technology research and development. Prod. Oper. Manage. 2014;23(3):348–365. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanyé-Mengual E., Pérez-López P., González-García S., et al. Eco-designing the use phase of products in sustainable manufacturing: The importance of maintenance and communication-to-user strategies. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014;18(4):545–557. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Z., Dababneh F., Li L. Joint energy, maintenance, and throughput modeling for sustainable manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020;50(6):2101–2112. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aflaki S., Netessine S. Strategic investment in renewable energy sources: The effect of supply intermittency. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manage. 2017;19(3):489–507. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jabbour C.J.C., Neto A.S., Gobbo J.A., et al. Eco-innovations in more sustainable supply chains for a low-carbon economy: A multiple case study of human critical success factors in Brazilian leading companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015;164:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S.J., Cachon G.P., Lai G., et al. Supply chain design and carbon penalty: Monopoly vs. monopolistic competition. Prod. Oper. Manage. 2015;24(9):1494–1508. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gill A. Green sustainable operations: A case from service industry. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manage. 2017;26(4):411–427. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding H., Zhao Q., An Z., et al. Collaborative mechanism of a sustainable supply chain with environmental constraints and carbon caps. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016;181:191–207. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drake D.F., Kleindorfer P.R., Van Wassenhove L.N. Technology choice and capacity portfolios under emissions regulation. Prod. Oper. Manage. 2016;25(6):1006–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mishra S., Singh S.P. Carbon management framework for sustainable manufacturing using life cycle assessment, IoT and carbon sequestration. Benchmarking. 2019;28(5):1396–1409. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang X., Atasu A., Beril Toktay L. Design implications of extended producer responsibility for durable products. Manage. Sci. 2019;65(6):2573–2590. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hafezalkotob A. Competition, cooperation, and coopetition of green supply chains under regulations on energy saving levels. Transp. Res. Part E. 2017;97:228–250. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trapp A.C., Harris I., Rodrigues V.S., et al. Maritime container shipping: Does coopetition improve cost and environmental efficiencies? Transp. Res. Part D. 2020;87 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahmoudi R., Rasti-Barzoki M. Sustainable supply chains under government intervention with a real-world case study: An evolutionary game theoretic approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018;116:130–143. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dahlmann F., Roehrich J.K. Sustainable supply chain management and partner engagement to manage climate change information. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019;28(8):1632–1647. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahapatra S.K., Schoenherr T., Jayaram J. An assessment of factors contributing to firms’ carbon footprint reduction efforts. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021;235 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma S., He Y., Gu R., et al. Sustainable supply chain management considering technology investments and government intervention. Transp. Res. Part E. 2021;149 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ren H., Zhou W., Guo Y., et al. A GIS-based green supply chain model for assessing the effects of carbon price uncertainty on plastic recycling. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020;58(6):1705–1723. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geyi D.G., Yusuf Y., Menhat M.S., et al. Agile capabilities as necessary conditions for maximising sustainable supply chain performance: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020;222 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naz F., Agrawal R., Kumar A., et al. Reviewing the applications of artificial intelligence in sustainable supply chains: Exploring research propositions for future directions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022;31(5):2400–2423. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villena V.H., Dhanorkar S. How institutional pressures and managerial incentives elicit carbon transparency in global supply chains. J. Oper. Manage. 2020;66(6):697–734. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen D., Ignatius J., Sun D., et al. Pricing and equity in cross-regional green supply chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020;280(3):970–987. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blanco C.C. A classification of carbon abatement opportunities of global firms. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manage. 2022;24(5):2648–2665. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao F., Souza G.C. Carbon offsetting with eco-conscious consumers. Manage. Sci. 2022;68(11):7879–7897. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalkanci B., Plambeck E.L. Managing supplier social and environmental impacts with voluntary versus mandatory disclosure to investors. Manage. Sci. 2020;66(8):3311–3328. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gopalakrishnan S., Granot D., Granot F., et al. Incentives and emission responsibility allocation in supply chains. Manage. Sci. 2021;67(7):4172–4190. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Acquah I.S.K., Agyabeng-Mensah Y., Afum E. Examining the link among green human resource management practices, green supply chain management practices and performance. Benchmarking. 2021;28(1):267–290. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong C.Y., Zhu Q. A research agenda for sustainability and business. Edward Elgar Publishing; Padfield: 2023. Research agenda for green supply chain management; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bressanelli G., Perona M., Saccani N. Challenges in supply chain redesign for the circular economy: A literature review and a multiple case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019;57:7395–7422. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo L., Yin H., Zhao X., et al. Managing your own low-tier suppliers with social and environmental responsibility violations via donation to NGOs: Why do multi-national corporations bother? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022;250 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bergendahl J.A., Sarkis J., Timko M.T. Transdisciplinarity and the food energy and water nexus: Ecological modernization and supply chain sustainability perspectives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018;133:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bai C., Dallasega P., Orzes G., et al. Industry 4.0 technologies assessment: A sustainability perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020;229 [Google Scholar]