Abstract

Background

For patients with recurrent serous borderline ovarian tumors (BOT) who have undergone unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, there is a risk of reduced or even lost ovarian reserve after the second surgery; therefore, fertility preservation (FP) prior to re-operation in patients of childbearing age is challenging, and has attracted increasing attention. Here, we discuss the multidisciplinary whole-process management of a patient with recurrent serous BOT, from embryo cryopreservation (EC) before re-fertility-sparing surgery (re-FSS) to successful delivery.

Case presentation

We describe the treatment of a 28-year-old married, nulliparous female with recurrent serous BOT who requested FP. The patient underwent right salpingo-oophorectomy in July 2020 for serous BOT. In March 2023, B-ultrasound indicated BOT recurrence, and she underwent a second operation. After a multidisciplinary discussion and information on the risks, the patient strongly requested EC. We used letrozole (LE) combined with an antagonist for ovarian stimulation; 16 eggs were obtained, 15 eggs were MII, four embryos on the 3rd day and one blastocyst was formed and cryopreserved. One month later, laparoscopic cystectomy was performed, and pathological examination revealed serous BOT. Three months after the operation, resuscitation and transplantation of one blastocyst did not result in pregnancy through the natural cycle (NC), followed by resuscitation and transfer of two embryos on day 3 through hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which resulted in a successful pregnancy and live healthy male birth. No recurrence was reported at 19 months after re-FSS.

Conclusions

This case highlights the key points of comprehensive multidisciplinary management from the discovery of BOT recurrence, multidisciplinary team (MDT) consultation, ovarian stimulation (OS), egg retrieval, EC, re-FSS, frozen embryo transfer (FET), to delivery. Re-FSS is safe and effective for patients with recurrent serous BOT and strong fertility requirements, and EC before re-FSS is feasible.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-025-07918-0.

Keywords: Borderline ovarian tumor (BOT), Re-fertility-sparing surgery (re-FSS), Embryo cryopreservation (EC), Multidisciplinary team (MDT), Case report

Introduction

Borderline ovarian tumors (BOT) are low malignant potential tumors with biological behavior between benign and malignant, accounting for 10-15% of all epithelial ovarian cancers, including serous and mucous histological subtypes [1, 2]. Patients with BOT display a better prognosis than those with ovarian cancer. According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), the 5-year and 10-year survival rates for stage I-III patients are 95–97% and 90%, respectively, falling to 77% for stage IV patients [2]. A total of 80% of BOT are diagnosed as stage I, and women of childbearing age before 40 years account for more than 1/3 of cases [2, 3]. Various oncology nursing associations emphasize that regardless of treatment, prognosis, marital relationship, sex, sexual orientation, and age, patients and their families should receive counseling and advice on infertility risks and fertility preservation (FP) options associated with tumor treatments [4].

Surgery is the main treatment method for BOT, including fertility-sparing surgery (FSS) and radical surgery, with postoperative recurrence rates of 13% and 0–5%, respectively. Surgical methods are mainly determined by the preoperative diagnosis, histological type, stage, and desire for fertility. Although the postoperative recurrence rate of FSS is high, it does not affect the overall survival rate; therefore, women with pregnancy desire of childbearing age can undergo FSS [2, 5]. FP is also considered a major component of the clinical management of patients with BOT.

Whether to perform surgery or ovarian stimulation (OS) first is a difficult problem faced by gynecologists and reproductive doctors. If surgery is performed first, ovarian reserve function may be reduced or even lost, especially in patients with recurrence who have had one adnexa removed or bilateral ovarian tumors; while performing OS and oocyte pick-up (OPU) first may result in poor OS response, egg retrieval failure, and the risk of tumor spread [6]. Recent studies have reported that oocyte and embryo freezing for FP after FSS is relatively safe and effective [7–9]. However, the clinical management of embryo cryopreservation (EC) prior to re-FSS and subsequent pregnancies is rare.

FP prior to second surgery in patients with recurrent BOT is challenging. Although the patients can undergo re-FSS, there is a greater risk of reduced or even lost ovarian reserve function after surgery; therefore, FP should be actively considered in women of childbearing age with BOT who express fertility desires, provided they meet stringent oncologic safety criteria (e.g., early-stage disease and serous histology). These patients often require individual assessment and treatment by a multidisciplinary team (MDT).

This case describes a case of recurrent BOT treated while including EC and followed by re-FSS, which ultimately led to a successfully delivered live birth. We explored the seven key points of diagnosis and treatment, including tumor recurrence, MDT, OS, OPU, EC, re-FSS, and frozen embryo transfer (FET) to delivery.

Case presentation

The patient was 28 years old and married with a 2-year history of primary infertility. On July 3, 2020, she underwent right salpingo-oophorectomy in another hospital for serous BOT and was re-examined every 3–6 months. However, the FIGO stage could not be definitively determined due to Missing surgical records. On November 22, 2022, B-ultrasonography at an external hospital indicated a mixed mass of solid cysts of the left ovary with a size of approximately 22 mm × 17 mm. On March 23, 2023, B-ultrasound showed a mixed mass in the left ovary, approximately 33 mm × 25 mm in size, with an irregularly shaped solid part, visible papillae, and polycystic changes in the left ovary (Fig. 1 A). No significant abnormalities were identified in serous tumor markers, including CA125 (28 U/mL; normal range 0–47 U/mL); Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), 2.22 ng/mL; basic follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), 7.9 mIU/mL; luteinizing hormone (LH), 6.70 mIU/mL; and estradiol (E2), 130 pmol/L. The patient was diagnosed with BOT and infertility.

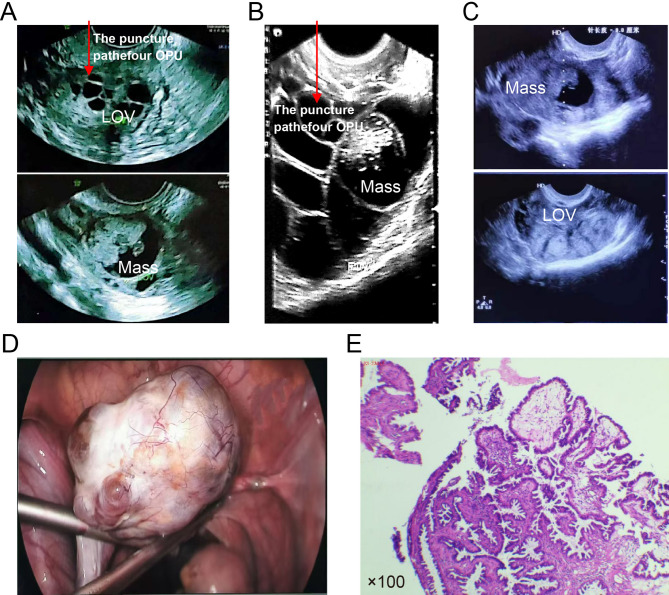

Fig. 1.

Examination and surgical results. A On March 23, 2023, B-ultrasound showed a mixed mass in the left ovary (LOV), approximately 33 mm × 25 mm in size, an irregularly shaped solid part, visible papillae, and polycystic changes. B Results of B-ultrasonography on the day of OPU before egg retrieval. Red arrows in A and B highlight the puncture path for oocyte pick-up (OPU). C B-ultrasonography results on the day of OPU after egg retrieval. D LOV appearance during laparoscopy. E Pathological examination

The gynecologists considered the possibility of BOT recurrence and recommended a second surgery. The patient strongly desired to have children and required FP before surgery. On March 28, 2023, an MDT consisting of experts in reproductive medicine, gynecology, pathology, and pharmacology discussed and recommended that the patient undergo oocyte and/or EC prior to surgery.

Starting March 31, 2023, the patient received an antagonist regimen for OS with recombinant follicle stimulating hormone β (rFSH-β) injection (200 IU subcutaneous injection q.d.) and letrozole (LE, 5 mg orally q.d.) for eleven days. When the maximum follicle reached 12.5 mm and serous E2 level was 1,085 pmol/L, ganirek was added 0.25 mg/day to trigger day. Ovulation was triggered with recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (rHCG, Ovidrel, 250 µg, subcutaneous injection) with a duration of action of 36 h. On trigger day, the serous E2 level was 3,374 pmol/L. Sixteen eggs were harvested, 15 of which were MII eggs, resulting in four embryos at the cleavage stage and one blastocyst which were cryopreserved (Fig. 1B-C). LE was continued for 10 days after OPU.

On April 24, 2023, B-ultrasonography revealed a mixed mass within the left ovary of approximately 29 mm × 23 mm in size. Laparoscopic cystectomy was performed in the gynecology department on May 10, 2023, which revealed a left ovarian cyst measuring 6 × 5 × 3 mm with an irregular surface (Fig. 1D), No visible implants were identified on the peritoneum or pelvic organs. Left ovarian cystectomy was performed, and the specimen was sent for intraoperative frozen section analysis, indicating serous BOT. Subsequently, omentectomy and peritoneal washings were performed, with both specimens submitted for histopathological examination. Final pathology confirmed the frozen section diagnosis of serous BOT (Fig. 1E). No malignant cells were detected in the omental tissue or peritoneal washings, and the FIGO stage was Ia.

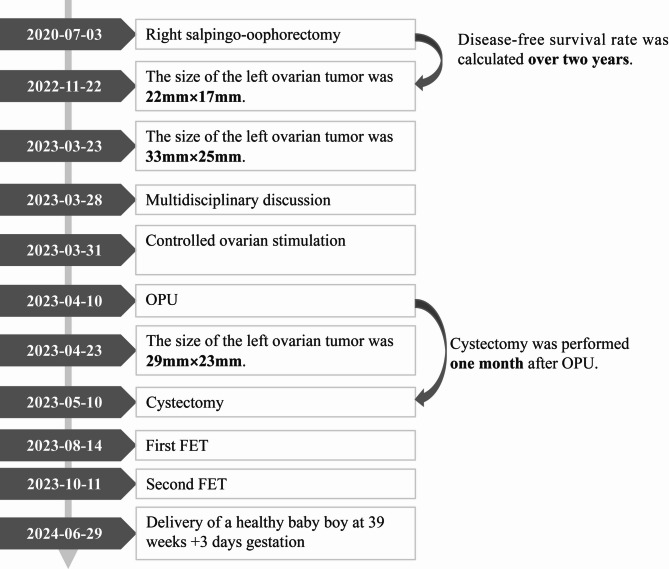

Transvaginal ultrasound during the second postoperative menstrual cycle showed normal ovarian morphology and follicular development, with no evidence of tumor recurrence. At the same time, the patient expressed urgent fertility desires due to a 2-year history of primary infertility. Therefore, in August 2023, resuscitation and transplantation of one blastocyst was performed and did not result in pregnancy through the natural cycle (NC) for endometrium preparation; on the day of endometrial transformation, follicular luteinization was found and the serous E2 level was 1,116 pmol/L. In September 2023 during the second FET cycle, HRT was selected as the endometrial preparation plan, and the endometrial membrane was transformed 12 days later after a low dose of estradiol valerate (2 mg orally twice daily) was given from the 4th day of menstruation, and two embryos were transplanted after luteal support 3 days later. The highest level of serous E2 during endometrial preparation was 498 pmol/L. The patient delivered a healthy male infant via spontaneous vaginal delivery at 39 weeks of gestation, with a birth weight of 3.5 kg. As of November 30, 2024, the patient has not reported tumor recurrence; the entire treatment process is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Patient treatment course

The compliance of the patient was very good throughout the treatment period and she made the followinf statement: “As a patient living with recurrent BOT, I feared losing my chance of motherhood. But the proactive approach of my clinical team made early pregnancy possible. Their end-to-end management, both medically and emotionally, was my anchor. This experience taught me that hope is a clinical strategy.”

This article was published with the patient’s written informed consent and was approved by the hospital ethics committee.

Disscussion and conclusions

BOT progresses slowly and has a low malignancy; 70% of patients are at stage I at diagnosis, and the 5-year survival rate is high [10]. The FSS and FP of BOT during the reproductive age are receiving increasing attention from both doctors and patients. Owing to the lack of high-quality evidence-based medical evidence on the safety and efficacy of FP prior to BOT surgery, it is recommended to establish an MDT to perform individualized diagnosis, treatment, and whole-process management for patients. In this case, the patient had a recurrent BOT and a strong desire for fertility. We established an MDT for experts in reproductive medicine, gynecology, pathology, and pharmacology for treatment and management. We discuss in detail the seven key issues in the diagnosis and treatment of this patient who underwent EC prior to re-FSS until delivery.

-

Is FSS safe and effective for BOT patient?

For BOT patients with a strong desire to have children, the first assessment was whether FSS could be performed, particularly if the uterus could be preserved. Currently, surrogacy is banned under Chinese law, and the only way to have a child is to maintain the uterus for BOT. Studies have shown that compared with non-FSS, the risk of BOT recurrence after FSS is increased but does not reduce patient survival. Generally, stage I patients still have BOT after recurrence, whereas stage II-IV patients have a higher risk of low-grade invasive ovarian cancer [11–13]. Therefore, most scholars suggest that stage I patients should consider FSS, whereas stage II-IV patients should receive individualized management [1]. In our case, the gynecologist concluded preoperatively that the patient was highly likely to have early recurrent BOT; therefore, FSS was administered.

-

Is FP necessary before FSS?

To determine whether FP is necessary for patients, it is first necessary to consider future fertility desire, age, ovarian reserve function, and the risk of reduced ovarian reserve function in subsequent treatments [6]. Cystectomy and partial ovariectomy can significantly reduce ovarian reserve function and might lead to declined fertility [13]. Our patient was a childbearing woman with a strong desire for fertility and a normal ovarian reserve. She underwent left salpingo-oophorectomy. It was necessary to perform FP before the second surgery, whether a cystectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy.

-

How to choose the method of FP before FSS?

Currently, commonly used FP methods include oocyte cryopreservation (OC), embryo cryopreservation (EC), ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC), and in vitro maturation of immature oocytes (IVM) [13, 14]. This is primarly determined by the patient’s marital status, severity of the primary disease, duration of treatment, and wishes. Current FP for recurrent BOT involves trade-offs as follows: OC is primarily used by postmenarchal women, allows for avoiding immediate sperm requirement, it necessitates stimulation and retains lower per-oocyte success than embryo freezing, offering the highest success rates per thawed unit but requiring sperm immediately and creating embryos with ethical/legal implications, both being clinically established options. IVM minimizes stimulation risk/delay. However, it yields significantly lower pregnancy rates due to technical challenges. OTC requires no stimulation delay, allows for the preservation of multiple follicles, and is vital for urgent cases/prepubertal girls. Nevertheless, it necessitates surgery and carries a theoretical malignancy reintroduction risk upon transplantation (which though remains low for BOT). Given the limited evidence for IVM and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC) in patients with BOT, these approaches are clinically not recommended. This perspective remains a personal opinion.

In this case, the patient was married and had both OC and EC options. She strongly requested an EC. From November 2022 to March 2023, the patient experienced 5 months of no significant increase in tumor size or normal tumor markers for five months, which was not an emergency surgery and had sufficient time for EC.

-

Is embryo cryopreservation (EC) before FSS safe?

Theoretically, OS and subsequent OPU are contraindicated in the presence of invasive ovarian tumors [15]. We believe that there are two issues to consider before EC in patients with BOT: (1) The application of fertility drugs during OS and delayed treatment might aggravate BOT; and (2) the nature and stage of the tumor cannot be accurately assessed before the operation, so OPU may lead to tumor rupture, or the tumor cells may spread to the pelvic cavity or vaginal wall through the puncture path, leading to tumor dissemination.

The 2024 Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine guidelines state that, although several studies have shown a small increase in the absolute risk of BOT after fertility drug treatment, there is insufficient consistent evidence that a particular fertility drug increases the risk of BOT [16]. In a study of 144 women conducted by Danish scholars in 2024, the type, time of first use, and cumulative dose of fertility drugs, including clomiphene, gonadotropin, gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor regulator, human chorionic gonadotropin, and progesterone, were not significantly correlated with BOT development [17]. In 2024, a retrospective study showed that ART with a long agonist, antagonist, and microstimulation regimen significantly increased the BOT recurrence rate in patients with a history of BOT but did not affect the overall survival rate [18]. These studies only addressed the effects of fertility drugs and high estrogen status in patients with a prior history of BOT and did not address whether there were negative effects in patients who were currently suffering from BOT.

The aromatase inhibitor LE inhibits estrogen synthesis and reduces the effects of high estrogen levels during OS. In the past 5 years, three teams have reported four cases of BOT patients that underwent OC before FSS: (1) In 2020, Filippi et al. reported that two patients with recurrent BOT received OS with LE before reoperation, and eventually successfully produced frozen eggs, during which no significant changes in the size of recurrent tumors were found [19]; (2) in 2024, Lombardi äh et al. successfully froze the oocytes of a 22-year-old patient with recurrent BOT using an LE combined antagonist regimen before re-FSS, and the tumor size did not increase 3 weeks later [13]; and (3) in 2024, Yae Ji Choi et al. reported a case of a patient with serous BOT who underwent two cycles of OS without LE and OC before the first and second FSS, respectively, and were able to resuscitate the eggs 2.5 years after OC and successfully delivered a healthy offspring [14]. The recurrence times after the first and secondary FSS in this patient were 11 and 15 months, respectively [14], while the mean recurrence time was 2 years [2]. These studies indicate that OS and OPU before FSS did not affect the overall survival rate, but only one case reported subsequent recovery and pregnancy with OC.

At the time of our patient’s visit, our doctor, with experience in OPU, first assessed that the OPU route would not directly pass through the mass (Fig. 1a, b) and that the risk of tumor rupture or overflow was low. Subsequently, LE combined with an antagonist regimen was administered for OS, OPU, and EC before surgery. The highest level of E2 was 3,374 pmol/L during OS. Since the left ovary of the patient was significantly enlarged, LE was continued until E2 returned to the baseline level 10 days after OPU. The reduction in the volume of the mass measured after OPU might reflect a measurement problem rather than an actual reduction, but it can indicate that EC before re-perforation for recurrent BOT was relatively safe. We suggest that in addition to assessing ovarian reserve function, these patients should also be evaluated to determine if the OPU puncture path can avoid passing through the mass and whether LE should be added to the OS to reduce the effect of high estrogen levels.

-

How to choose the surgical style of re-FSS for recurrent BOT patients?

In this study, ‘re-FSS’ refers to the repetition of fertility-sparing surgery (FSS) in a patient with recurrent BOT. The term “re-FSS” is proposed here to distinguish this iterative approach from primary FSS, reflecting the unique clinical challenges of managing recurrent BOT in fertility-desiring patients.

FSS includes unilateral or bilateral cystectomy and salpingo-oophorectomies. A retrospective study by Wang et al. found that for patients with recurrent BOT who underwent FSS for the first time, there was no significant difference in the recurrence rate between radical surgery and unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; the recurrence rate of cystectomy increased, although there was no significant difference in the overall survival rate between the three groups [20]. A multicenter study in France showed that the proportion of live births in patients with recurrent BOT after re-FSS could reach 1/4, and no other adverse events occurred [21]. Therefore, patients with local recurrence are encouraged to consider re-FSS after multidisciplinary discussion [21]. Our patient’s BOT was most likely confined to the ovary. Cystectomy was performed at the patient’s request, and no recurrence was found 19 months after surgery, up to the date the article was written, further validating the feasibility of re-FSS. However, long-term oncologic safety data for re-FSS remains limited and recurrence beyond 2 years requires further follow-up.

-

How to decide the timing and way to get pregnant after FSS?

The optimal timing for pregnancy following FSS remains undetermined. According to the 2022 Chinese Expert Consensus on Fertility Preservation in Ovarian Malignancies, patients not requiring postoperative chemotherapy could attempt conception 3–6 months after surgery under close monitoring. Delayed pregnancy might diminish fertility due to risks such as fallopian tube adhesions and advancing maternal age [22]. Consequently, we recommended initiating pregnancy attempts at 3 months postoperatively for our patient. Although she retained one ovary with normal follicular development, allowing for natural conception or another IVF round, two factors influenced her decision: (1) Financial constraints: Repeating oocyte retrieval would require high out-of-pocket investment (as fertility treatments for BOT are not covered by insurance in China); (2) Patient-centered concerns: A 2-year history of primary infertility, urgent desire for childbearing, and anxiety about tumor recurrence led the patient to decline natural conception or additional retrievals, insisting on frozen embryo transfer. As clinicians, we prioritized respecting patient autonomy in alignment with ethical guidelines for oncofertility [23] and opted for FET.

-

How to choose the endometrial Preparation regimen of FET after FSS?

Endometrial preparation regimens for FET include NC, stimulation cycles, and HRT. At present, there is no literature reporting which FET protocol should be selected for patients with recurrent BOT after FSS. Serous BOT with high-risk histological features (micropapillary pattern, interstitial microinfiltration, or peritoneal implantation) reportedly retains a higher risk of hormone-sensitive recurrence [24]. Although our patients do not have these high-risk factors, for safety reasons, we still selected the NC scheme for the first cycle. we selected the NC scheme for the first cycle. Despite the presence of an LH peak, follicular luteinization was observed, and the patient was not pregnant after thawing or transplanting the first embryo. The analysis indicates that the embryo was not synchronized with the endometrium because of the inaccurate timing of the progesterone elevation. In the second FET cycle, HRT with low-dose estrogen supplementation was selected for endometrial preparation, and the patient became successfully pregnant, resulting in the delivery of healthy offspring. The maximum serous E2 level (498 pmol/L) during the HRT was significantly lower than that on the LH peak day in the NC group (1,116 pmol/L). Therefore, in the hereby-presented case, HRT for endometrial preparation was deemed safe under close monitoring.

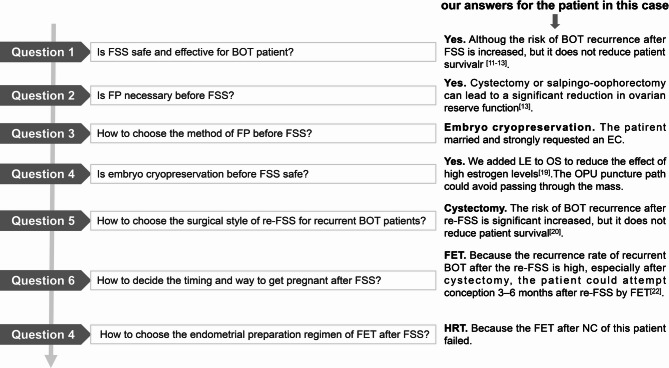

In conclusion, re-FSS is safe and effective in our patients with recurrent serous BOT with strong fertility requirements, and EC before re-FSS is feasible after MDT discussions and whole-process management (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Questions that need to be discussed step-by-step by the MDT for embryo cryopreservation before FSS in BOT patients and our answers for the patient in this case. MDT, multidisciplinary team; FSS, fertility-sparing surgery; BOT, borderline ovarian tumor; FP, fertility preservation; re-FSS, re-fertility-sparing surgery; LE, letrozole; OS, ovarian stimulation; OPU, oocyte pick-up; FET, frozen embryo transfer

However, this case report still has the following limitations: (1)The retrospective nature of this study limited access to historical surgical details (e.g., FIGO staging), potentially affecting comprehensive recurrence risk stratification. (2) Tumor progression was monitored solely through serial transvaginal ultrasound measurements of tumor size, serving as an indirect indicator, its sensitivity to subtle biological changes or microlesions remains limited. Consequently, we cannot definitively confirm whether OS directly influenced tumor progression. (3) Postoperative ovarian reserve parameters (e.g., serum AMH levels and antral follicle count) were not systematically assessed in this study. Therefore, the potential impact of OS on ovarian function remains unquantified, potentially limiting the comprehensive interpretation of FP strategy safety. (4) This individual case only represents the observation of this specific patient, generalizing the findings to the entire population is thus difficult. EC and OC safety and efficacy prior to re-FSS for recurrent BOT require further large-sample and multicenter studies, including the incorporation of longitudinal AMH monitoring and long-term follow-up to clarify OS risks on ovarian reserve depletion and tumor recurrence.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AMH

Anti-Müllerian hormone

- APHONa

Association Nurses of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology

- ART

Assisted reproductive technology

- BOT

Borderline ovarian tumor

- CANO/ACIO

Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology/Association Canadienne des Infirmières en Oncologie

- E2

Estradiol

- FET

Frozen embryo transfer

- FIGO

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- FP

Fertility preservation

- FSH

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- HRT

Hormone replacement therapy

- LE

Letrozole

- LH

Luteinizing hormone

- MDT

Multidisciplinary team

- NC

Natural cycle

- OC

Cryopreservation

- ONS

Oncology Nursing Society

- OPU

Oocyte pick up

- OS

Ovarian stimulation

- Re-FSS

Re-fertility sparing surgery

- rFSH-β

Recombinant follicle stimulating hormone β

- rHCG

Recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin

Authors’ contributions

Q.X. obtained patient consent and approval from the hospital ethics committee, conceived the manuscript, performed the literature search and analysis, and formulated the first version of the manuscript. L.T. was responsible for patient management and follow-up, and collated some clinical data. L.W. was responsible for the pathological examination and the provision of relevant data. BL was mainly responsible for the ultrasound examinations of patients and providing related images. Z.T. and N.L. monitored the ovarian stimulation and frozen embryo transfer. J.G. contributed to the surgery and provided the images. L.Z. contributed to the English translation of the article, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Regional Science Foundation Project (82260301), Science and Technology plan project of the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province (XDYC-QNRC-2023-0443), Yunnan Province High-level Scientific and Technological Talents and Innovation Team Selection Special-Young and Middle-aged Academic and Technical Leaders Reserve Talent Project (202405AC350060), and Kunming University of Science and Technology Medical Joint Project (KUST-KH2023021Y).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province (number: 2024-GN013). All the patients agreed to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient. The hospital ethics committee approved the publication of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qin Xu and Limei Tao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jing Ge, Email: 1719971601@qq.com.

Li Zhuan, Email: zhuanli.yunnan@163.com.

References

- 1.Gracia M, Alonso-Espías M, Zapardiel I. Current limits of conservative treatment in ovarian cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2023;35:389–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Della Corte L, Cafasso V, Mercorio A, Vizzielli G, Conte C, Giampaolino P. Management of borderline ovarian tumor: the best treatment is a real challenge in the era of precision medicine. Front Surg. 2023;10: 1167561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tortajada Valle M, Agustí N, Fusté P, Mensión E, Díaz-Feijóo B, Glickman A, Marina T, Torné A. Laparoscopic fertility-sparing management of borderline ovarian tumors: surgical and long-term oncological outcomes. J Clin Med. 2024. 10.3390/jcm13185458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fertility Preservation in Individuals with Cancer. A joint position statement from APHON, CANO/ACIO, and ONS. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2024;34:421–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morice P, Scambia G, Abu-Rustum NR, Acien M, Arena A, Brucker S, Cheong Y, Collinet P, Fanfani F, Filippi F, Eriksson AGZ, Gouy S, Harter P, Matias-Guiu X, Pados G, Pakiz M, Querleu D, Rodolakis A, Rousset-Jablonski C, Stepanyan A, Testa AC, Macklon KT, Tsolakidis D, De Vos M, Planchamp F, Grynberg M. Fertility-sparing treatment and follow-up in patients with cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, and borderline ovarian tumours: guidelines from ESGO, ESHRE, and ESGE. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:e602–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo M, Lindheim SR, Pereira N. Scoping out follicles - simultaneous laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy and oocyte retrieval for fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2024;123:75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosyns S, Van Moer E, De Quick I, Tournaye H, De Vos M. Reproductive outcomes in women opting for fertility preservation after fertility-sparing surgery for borderline ovarian tumors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309:2143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geoffron S, Lier A, de Kermadec E, Sermondade N, Varinot J, Thomassin-Naggara I, Bendifallah S, Daraï E, Chabbert-Buffet N, Kolanska K. Fertility preservation in women with malignant and borderline ovarian tumors: experience of the French ESGO-certified center and pregnancy-associated cancer network (CALG). Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:817–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khiat S, Provansal M, Bottin P, Saias-Magnan J, Metzler-Guillemain C, Courbiere B. Fertility preservation after fertility-sparing surgery in women with borderline ovarian tumours. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasconcelos I, de Sousa Mendes M. Conservative surgery in ovarian borderline tumours: a meta-analysis with emphasis on recurrence risk. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:620–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourdel N, Huchon C, Abdel Wahab C, Azaïs H, Bendifallah S, Bolze PA, Brun JL, Canlorbe G, Chauvet P, Chereau E, Courbiere B, De La Motte Rouge T, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Eymerit-Morin C, Fauvet R, Gauroy E, Gauthier T, Grynberg M, Koskas M, Larouzee E, Lecointre L, Levêque J, Margueritte F, D’Argent Mathieu E, Nyangoh-Timoh K, Ouldamer L, Raad J, Raimond E, Ramanah R, Rolland L, Rousset P, Rousset-Jablonski C, Thomassin-Naggara I, Uzan C, Zilliox M, Daraï E. Borderline ovarian tumors: French guidelines from the CNGOF. Part 2. Surgical management, follow-up, hormone replacement therapy, fertility management and preservation. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbonnel M, Layoun L, Poulain M, Tourne M, Murtada R, Grynberg M, Feki A, Ayoubi JM. Serous borderline ovarian tumor diagnosis, management and fertility preservation in young women. J Clin Med. 2021. 10.3390/jcm10184233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lombardi Fäh V, Del Vento F, Intidhar Labidi-Galy S, Undurraga M. Ovarian stimulation with letrozole in nulliparous young women with relapsing early-stage serous borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2024;56:101531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi YJ, Hong YH, Paik H, Kim SK, Lee JR, Suh CS. A successful live birth from a vitrified oocyte for fertility preservation of a patient with borderline ovarian tumor undergoing bilateral ovarian surgery: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2024;39:e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buonomo B, Peccatori FA. Fertility preservation strategies in borderline ovarian tumor recurrences: different sides of the same coin. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1217–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fertility drugs and. Cancer: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2024;122:406–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristensen AK, Frandsen CLB, Nøhr B, Viuff JH, Hargreave M, Frederiksen K, Kjær SK, Jensen A. Risk of borderline ovarian tumors after fertility treatment - results from a Danish cohort of infertile women. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;185:108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao H, Wei W, Li Y, Wei H, Wang N. Does controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in women with a history of borderline tumor influence recurrence rate? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309:1515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filippi F, Martinelli F, Somigliana E, Franchi D, Raspagliesi F, Chiappa V. Oocyte cryopreservation in two women with borderline ovarian tumor recurrence. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1213–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Zhong Q, Tang Q, Wang H. Second fertility-sparing surgery and fertility-outcomes in patients with recurrent borderline ovarian tumors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;306:1177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chevrot A, Pouget N, Bats AS, Huchon C, Guyon F, Chopin N, Rousset-Jablonski C, Beurrier F, Lambaudie E, Provansal M, Sabatier R, Heinemann M, Ngo C, Bonsang-Kitzis H, Lecuru F, Bailly E, Ferron G, Cornou C, Lardin E, Leblanc E, Philip CA, Ray-Coquard I, Hequet D. Fertility and prognosis of borderline ovarian tumor after conservative management: results of the multicentric OPTIBOT study by the GINECO & TMRG group. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.卵巢恶性肿瘤保留生育功能的中国专家共识(2022年版). [Chinese expert consensus on fertility preservation in ovarian malignancies (2022 edition)]. 中国实用妇科与产科杂志. 2022;38:705–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowell EE, Lautz TB, Lai K, Weidler EM, Johnson EK, Finlayson C, van Leeuwen K. The ethics of offering fertility preservation to pediatric patients: a case-based discussion of barriers for clinicians to consider. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2021;30: 151095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rousset-Jablonski C, Pautier P, Chopin N. Borderline ovarian tumours: CNGofs guidelines for clinical practice - hormonal contraception and MHT/HRT after borderline ovarian tumour. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2020;48:337–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.