Abstract

Objectives:

The prolapse quality-of-life (P-QOL) questionnaire is frequently used to assess changes in symptoms before and after surgery in patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP). This study investigated whether P-QOL scores were significantly affected by pre- and postoperative conditions in patients with surgically treated POP.

Materials and Methods:

The study enrolled 158 patients who underwent surgery for POP at our hospital between May 2016 and May 2023. Seventy-two patients underwent laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC), whereas 86 underwent transvaginal mesh (TVM) surgery. To evaluate the POP-related conditions, the 60-min pad test and the Japanese version of P-QOL were used before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery.

Results:

In patients with stage 4 POP, all P-QOL component scores, except for sleep/energy, significantly declined after surgery in the LSC group. Conversely, some component scores did not show a significant difference after the surgery in the TVM group. No significant differences in the rate of urinary incontinence, mesh exposure, or prolapse recurrence (PR) were observed between the two groups; however, the rate of PR was much higher in the TVM group than in the LSC group, although no significant differences were found in patients with stage 4 POP. Accordingly, some P-QOL component scores were significantly higher in the TVM group than in the LSC group (all P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The surgical outcomes of POP have a significant effect on P-QOL. Postoperative conditions can be evaluated using P-QOL scores.

Keywords: laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, prolapse quality-of-life questionnaire, transvaginal mesh surgery

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is used to describe the condition in which the lack of connective tissue support causes one or more pelvic organs, such as the uterus, apex of the vagina, or bowels, to descend from their natural position.[1] Because of population aging and the rising obesity rates, the incidence of POP is increasing. For those aged > 50 years, the lifetime prevalence of POP is between 30% and 50%.[2] Women aged 80 years have an 11.1% possibility to undergo surgeries for prolapse or urinary incontinence (UI).[3] POP is linked to physical, psychological, and sexual issues and disabilities with detrimental effects on women’s quality of life (QOL).[4]

In recent years, transvaginal mesh (TVM) surgery or laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) is performed in Japan to treat patients with POP.[5] For the surgical treatment of POP, both techniques appear to have promising outcomes.[5,6] According to several studies, TVM is an effective choice for high-risk women, such as older patients,[7,8,9] whereas LSC is typically reserved for younger patients who engage in greater sexual activity.[10,11] However, in our experience, using different techniques according to the severity of POP rather than age is more practical. Moreover, LSC was associated with a lower recurrence rate for treating POP at POP Quantification (POP-Q) System stage 4 and was also a safe procedure with a low complication rate.[12,13,14] However, no significant difference in preoperative outcomes was found in patients with POP at stage ≤3 in our experience.

In previous studies, the residual urine volume, 60-min pad weight testing, International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), Overactive Bladder Symptom Score (OABSS), and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) were used to evaluate the change in the QOL after surgery for POP.[15,16] On the contrary, the prolapse QOL questionnaire (P-QOL) is frequently applied to measure improvement in patients with POP.[17] However, our previous studies did not include the P-QOL results because of insufficient data.[15,16] Conversely, the present study analyzed data from patients with complete P-QOL component scores before and after surgery.

In the present study, we investigated whether P-QOL scores were affected by the preoperative conditions and postoperative outcomes in patients who underwent surgical treatment for POP. In addition, whether P-QOL scores were associated with the difference in postoperative outcomes including complication rates was also evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Medical records of 158 patients who underwent LSC (n = 72) or TVM (n = 86) between May 2016 and May 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. Surgery was indicated for stage ≥2 POP with symptoms such as vaginal prolapse, hydronephrosis, or hydroureter, and asymptomatic POP.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures performed in this study complied with the ethical guidelines of the National Defense Medical College (Saitama, Japan; ID: 4219). On August 21, 2020, the National Defense Medical College Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent before surgery. Patients who underwent either of the surgeries within the aforementioned time frame were eligible and included in this study, but those who declined to participate were excluded.

The median postoperative observation period was 24.6 months (range: 12.2–36.9). Table 1 shows the clinical data such as age, body mass index (BMI), POP-Q stage, details of POP, previous laparotomies, blood loss, operative time, and major complications.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients

| LSC (n=72) | TVM (n=86) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), median (IQR) or mean±SD | 73.5 (68.3-77) | 76.4±6.9 | 0.0004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.5±2.4 | 24.9±3.7 | <0.0001 |

| POP-Q stage | Stage 2 5 | Stage 2 0 | 0.0135 |

| Stage 3 52 | Stage 3 75 | ||

| Stage 4 15 | Stage 4 11 | ||

| Past transabdominal surgery | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 0.0443 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 2 (0−7.5) | 26.5 (16−61.5) | <0.0001 |

| Operating time (h) | 3.2 (2.6-4.5) | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Major complications | Bladder injury 2 | No complications |

LSC, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. TVM, transvaginal mesh surgery. IQR, interquartile range. SD, standard deviation. BMI, body mass index. POP-Q, pelvic organ prolapse quantification

Values for normally distributed measurements are expressed as mean ± SD, and values for non-normally distributed values are expressed as median variables (IQR). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine significant difference in age, history of abdominal surgery, blood loss, and operative time. Student’s t-test was used to test for significant difference in BMI. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to determine the difference in the POP-Q stage between the LSC and TVM groups. LSC: laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. TVM: transvaginal mesh surgery. SD: standard deviation. IQR: interquartile range. BMI: body mass index. POP-Q: pelvic organ prolapse quantification

Surgical methods

The LSC was performed following the method described by Wattiez et al.[18] Briefly, after the patient was placed in the lithotomy position and induction of general anesthesia, an 18-Fr urinary catheter was inserted into the bladder. To access the abdominal cavity, the umbilical region was cut open, and a 10-mm camera port was installed. Both 5-mm ports were placed at two lateral digits to the left and right superior anterior iliac spine (for the surgeon’s left hand and for the assistant), and a 10-mm port was placed (for the surgeon’s right hand). The patient was placed in a Trendelenburg position with all ports in place and inclined 15° from the horizontal position, and the bowel was pushed toward the head to obtain a view of the pelvic cavity. The following procedures were performed: (1) dissection of the anterior vaginal wall and bladder and fixation of the anterior wall mesh (Polyform™ [Boston Scientific Japan, Japan, Tokyo] or ORIHIME® [Kono Seisakusho, Japan, Tokyo]), (2) subtotal hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy in the presence of a uterus, (3) dissection of the posterior vaginal wall and rectum and fixation of the posterior wall mesh, (4) mesh retroperitonealization and closure of the pelvic floor peritoneum, and (5) mesh fixation on the anterior longitudinal ligament.

Our Uphold-type TVM was carried out in accordance with the techniques reported by Takazawa et al.[10] Briefly, after hydrodissection with 20 mL of saline with 1:500,000 epinephrine, the anterior vaginal wall was incised vertically from the point below the bladder neck to the lowest portion of the prolapse. To reach the sacrospinous ligaments, a full-thickness blunt dissection of the pubocervical fascia was performed laterally. From the ischial spines toward the sacrum, dissections were performed at a distance of 1–2 finger breadths. Further dissections were made toward the sacrum, 1–2 fingerbreadths below the ischial spines. Then, the skin was incised 3 cm down and 4 cm lateral to the anal center. Using a Shimada needle with a hole on the tip threaded with a nylon monofilament suture, the sacrospinous ligaments were penetrated from this incision at the point of two fingerbreadths (about 3 cm) medial to the ischial spine. The arms of the Uphold®-shaped mesh were pulled out using the nylon monofilament loops through the penetrated point of the sacrospinous ligaments. This allowed the mesh beneath the bladder to spread and take the shape of a trapezoid. Finally, traction on the exteriorized arms ensured proper placement, and vaginal wound was closed with 2-0 Vicryl® (Johnson and Johnson, Japan, Tokyo).

Assessment methods of preoperative and postoperative parameters

To assess POP-related conditions, a 60-min pad test and Japanese version of P-QOL were administered before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery. Although a later validated Japanese version exists,[19] we used the Japanese version published earlier by Fukumoto et al.[20] We did not use the validated version because we determined that the version of Fukumoto et al. was sufficient to assess symptoms related to POP. This P-QOL questionnaire contains eight multi-item domains, namely, general health perceptions, prolapse impacts, role limitations, physical/social limitations, personal relationships, emotions, sleep/energy, and severity measures.[20] Possible P-QOL scores range from 0 (best health perception) to 100 (worst health perception), which is based on the original version reported by Digesu et al.[17]

Prolapse was quantified using POP-Q. Prolapse recurrence (PR) was defined as the most dependent portion being at POP-Q stage ≥ 2, which means that the most distal prolapse portion is ≥?1?cm from the hymen plane, according to Takazawa −1 cm from the hymen plane, according to Takazawa et al.[10] UI occurrence was defined by a daily life disturbance with incontinence. Mesh exposure (ME) was vaginally and/or visually examined using a vaginal scope.

Statistical analysis

The Kruskal–Wallis and unpaired t-tests were used to compare the differences in variables between the LSC and TVM groups. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to compare the preoperative POP-Q stage and postoperative complication rates between the LSC and TVM groups. To investigate for variations in P-QOL domains between the two assessment points (before surgery vs. 6 and 12 months after surgery), the Wilcoxon rank test was performed. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP PRO version 17 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient parameters of the laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy and transvaginal mesh groups

The median age was 73.5 years in the LSC group and the mean age was 76.4 years in the TVM group, which showed a significant difference (P = 0.0004). The mean BMI was 22.5 kg/m2 in the LSC group and 24.9 kg/m2 in the TVM group, which showed a significant difference (P < 0.0001). Fifteen patients from the LSC group had stage 4, while 11 from the TVM group had stage 4, which showed a significant difference (P = 0.0135). The median number of past transabdominal surgeries was 0 in both groups, which did not show any significant difference (P = 0.0443). However, the median blood loss was 2 mL in the LSC group and 26.5 mL in the TVM group, which showed a significant difference (P < 0.0001). The median operating time was 3.2 h in the LSC group and 1.0 h in the TVM group, which also showed a significant difference (P < 0.0001) [Table 1]. Major complications during surgeries were also shown in Table 1. Bladder injuries were repaired during both procedures. All of them were rated as Clavien–Dindo classification grade 1.[21]

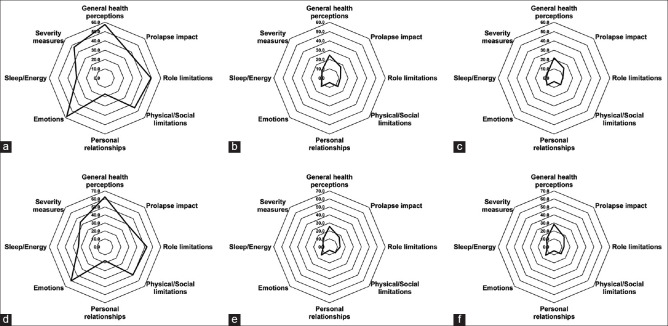

In all patients, all P-QOL domain scores significantly declined 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with the preoperative condition in the LSC and TVM groups [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

All patients. Prolapse quality-of-life (P-QOL) domain scores before surgery (a), 6 months after surgery (b), and 12 months after surgery (c) in the laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) group. P-QOL scores before surgery (d), 6 months after surgery (e), and 12 months after surgery (f) in the transvaginal mesh (TVM) group. They are expressed as a percentage of the full score. In both the LSC and TVM groups, each P-QOL domain score significantly decreased 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with preoperative values (all P < 0.0001)

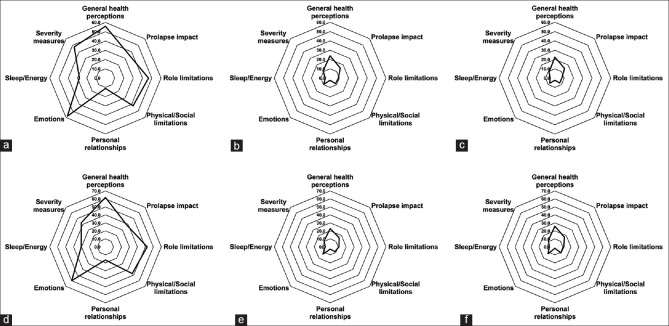

In patients with stage ≤ 3 POP, all P-QOL domain scores also significantly decreased 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with the preoperative condition in the LSC and TVM groups [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Patients with stage ≤ 3 pelvic organ prolapse. Prolapse quality-of-life (P-QOL) domain scores before surgery (a), 6 months after surgery (b), and 12 months after surgery (c) in the laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) group. P-QOL scores before surgery (d), 6 months after surgery (e), and 12 months after surgery (f) in the transvaginal mesh (TVM) group. They are expressed as a percentage of the full score. In both the LSC and TVM groups, each P-QOL component score significantly decreased 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with preoperative values (all P < 0.01)

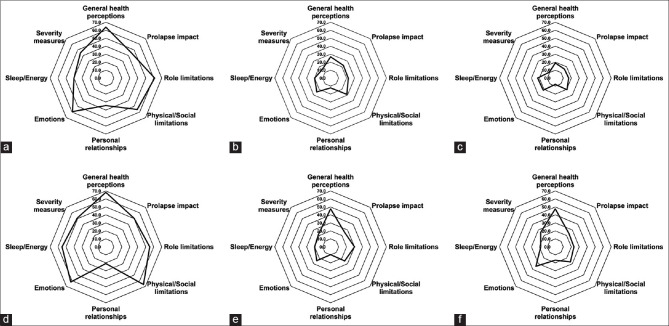

In patients with stage 4 POP, all P-QOL domain scores, except for sleep/energy, significantly declined 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with the preoperative condition in the LSC group. On the contrary hand, the role limitations scores were not significantly different 6 months after surgery, the personal relationships scores were not significantly different 6 and 12 months after surgery, and the emotions scores were not significantly different 12 months after surgery compared with the corresponding preoperative conditions in the TVM group [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Patients with stage 4 pelvic organ prolapse. Prolapse quality-of-life (P-QOL) domain scores before surgery (a), 6 months after surgery (b), and 12 months after surgery (c) in the laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) group. P-QOL scores before surgery (d), 6 months after surgery (e), and 12 months after surgery (f) in the transvaginal mesh (TVM) group. They are expressed as a percentage of the full score. In the LSC group, each P-QOL domain score, except for sleep/energy, significantly decreased 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with preoperative values (all P < 0.05). In the TVM group, the role limitations score 6 months after surgery, personal relationships scores 6 and 12 months after surgery, and emotions score 12 months after surgery did not show any significant difference compared with the preoperative values. Except for them, each P-QOL domain score significantly decreased 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with preoperative values (all P < 0.05)

No significant differences in the incidence of UI, ME, or PR were observed between the LSC and TVM groups in patients with stage ≤ 3 POP; however, the UI rate was higher in the TVM group than in the LSC group. Moreover, the P-QOL domain scores were not significantly different between the LSC and TVM groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association between surgical methods and the presence of incontinence, mesh exposure, prolapse recurrence, the P-QOL in patients with POP-Q ≤stage 3

| LSC (n=57) Median (IQR) |

TVM (n=75) Median (IQR) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incontinence | Present | 4 (7.0) | 12 (16.0) | 0.1173 |

| Absent | 53 (93.0) | 63 (84.0) | ||

| Mesh exposure | Present | 1 (1.8) | 4 (5.3) | 0.2860 |

| Absent | 56 (98.2) | 71 (94.7) | ||

| Prolapse recurrence | Present | 2 (3.5) | 5 (6.7) | 0.4226 |

| Absent | 55 (96.5) | 70 (93.3) | ||

| P-QOL | General health perceptions | 2 (0-2.5) | 1 (1-3) | 0.5721 |

| Prolapse impact | 9 (3.5-16) | 11.5 (6-17.25) | 0.3466 | |

| Role limitations | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-1.25) | 0.5333 | |

| Physical/Social limitations | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 0.5205 | |

| Personal relationships | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0.7419 | |

| Emotions | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-2) | 0.1119 | |

| Sleep/Energy | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0.25) | 0.4852 | |

| Severity measures | 0 (0-2) | 1 (0-3) | 0.364 |

LSC, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. TVM, transvaginal mesh surgery. IQR, interquartile range. P-QOL, prolapse quality of life questionnaire No significant differences in the rates of urinary incontinence, mesh exposure, and prolapse recurrence were found in patients with stage ≤ 3 POP between the LSC and TVM groups. Each P-QOL domain score did not differ significantly between the LSC and TVM groups. LSC: laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. TVM: transvaginal mesh surgery. IQR: interquartile range. P-QOL: prolapse quality of life questionnaire

No significant differences in the rates of UI, ME, or PR were found between the LSC and TVM groups in patients with stage 4 POP. However, the PR rate was higher in the TVM group than in the LSC group in patients with stage 4 POP, although no significant differences were noted (P = 0.0577). The general health perception, prolapse impact, and severity measures scores of the P-QOL were significantly higher in the TVM group than in the LSC group (P = 0.0045, P = 0.0485, P = 0.0314, respectively) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association between surgical methods and the presence of incontinence, mesh exposure, prolapse recurrence, the P-QOL in patients with POP-Q stage 4

| LSC (n=15) Median (IQR) |

TVM (n=11) Median (IQR) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incontinence | Present | 2 (13.3) | 3 (27.3) | 0.3729 |

| Absent | 13 (86.7) | 8 (72.7) | ||

| Mesh exposure | Present | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | No Value |

| Absent | 15 (100) | 11 (100) | ||

| Prolapse recurrence | Present | 1 (6.7) | 4 (36.4) | 0.0577 |

| Absent | 14 (93.3) | 7 (63.6) | ||

| P-QOL | General health perceptions | 1 (0-2) | 3 (2-4) | 0.0045 |

| Prolapse impact | 11 (3-15) | 17 (12.5-23.25) | 0.0485 | |

| Role limitations | 0 (0-2) | 0.5 (0-2.5) | 0.451 | |

| Physical/Social limitations | 1 (0-4) | 2.5 (0-6) | 0.3878 | |

| Personal relationships | 0 (0-0.75) | 0 (0-1.25) | 0.8008 | |

| Emotions | 0 (0-3) | 3 (0-4.5) | 0.224 | |

| Sleep/Energy | 0 (0-2) | 3 (0-2.25) | 0.7589 | |

| Severity measures | 0 (0-2) | 3 (0.75-5) | 0.0314 |

LSC, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. TVM, transvaginal mesh surgery. IQR, interquartile range. P-QOL, prolapse quality of life questionnaire No significant differences in the rates of urinary incontinence, mesh exposure, and prolapse recurrence were found in patients with stage 4 POP between the LSC and TVM groups. However, the prolapse recurrence rate was higher in the TVM group than in the LSC group. The general health perception score, prolapse impact score, and severity measures score of the P-QOL were significantly higher in the TVM group than in the LSC group 12 months after surgery. LSC: laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. TVM: transvaginal mesh surgery. IQR: interquartile range. P-QOL: prolapse quality of life questionnaire

DISCUSSION

In this study, the P-QOL scores significantly decreased 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with the preoperative scores in patients with every stage of POP in the LSC group, except for the sleep/energy score 6 and 12 months after surgery in patients with stage 4 POP [Figures 2 and 3 and Tables 2 and 3]. On the contrary, the P-QOL scores significantly decreased 6 and 12 months after surgery compared with the preoperative scores in patients with every stage of POP in the TVM group, except for the role limitations score 6 months after surgery, personal relationships score 6 and 12 months after surgery, and emotions score 12 months after surgery in stage 4 POP [Figures 2 and 3 and Tables 2 and 3]. These differences were consistent with the rates of postoperative UI and PR between the LSC and TVM groups.

In previous studies, patients who underwent TVM had favorable surgical outcomes.[15,16] TVM is suggested to have comparable postoperative results to LSC when limited to POP-Q stage ≤ 3. TVM was also effective not only in repairing POP but also in improving symptoms of urinary difficulty and overactive bladder.[10,15,16] On the contrary, LSC revealed satisfactory postoperative outcomes and was effective in repairing POP and improving dysuria and overactive bladder.[22,23] To our knowledge, both surgical techniques are highly effective treatments in treating POP and POP-related urinary symptoms in our experience.

To choose the most appropriate clinical treatment in each case (surgical or conservative) and assess its efficacy, symptom severity, and influence on the QOL of women with POP must be considered.[17] In actuality, the primary goal of any prolapse treatment is to improve the patient’s QOL. Because women feel uncomfortable when being assessed clinically, the effect of the assessment on patients may be difficult or erroneous to determine. In this sense, the P-QOL questionnaire is simple to use in research and clinical settings. In fact, P-QOL has been used to assess QOL before and after surgery for POP.[24] It has also been translated into and approved for use in languages other than English.[25] As an alternative, the extent of POP improvement was evaluated through physical examination and medical interview while the patient was in the lithotomy position, and IPSS was utilized to assess voiding dysfunction in female patients with POP because P-QOL data were missing from our earlier investigations.[15,16] P-QOL data were completely filled out in this study.

In the present study, the Japanese version of the P-QOL was used according to the report by Fukumoto et al.[20] The study patients found the Japanese version of the P-QOL easy to comprehend, and they did not report any difficulties. This could be attributed to the straightforward questions and answers. Because the Japanese version was found relevant in every QOL component, it did not require adaptation to Japanese culture. Even if the P-QOL questionnaire might be designed with a European population, the meaning, intent, and structure in the original version were nearly preserved in the Japanese translation.[20]

Outcome measures in clinical trials were ought to demonstrate responsiveness in addition to validity and reliability.[26] A factor to consider in scale selection is to assess whether the effectiveness of a therapeutic intervention is responsive or sensitive to change, which refers to the capacity to recognize changes caused by therapy or disease progression. In actuality, a poor response may cause a type II error, i.e. a lack of difference when a true difference exists, which could result in underestimating the treatment’s effectiveness.[27] On the contrary, responsiveness is important in women’s urology because the primary goal of an intervention is to improve the patient’s QOL.[28] Thus, responsiveness, an essential psychometric feature, must be evaluated. The general health perceptions domain had the highest scores in patients with stage 4 POP in the TVM group, whereas the general health perceptions domain garnered the lowest scores in patients with stage 4 POP in the LSC group. Accordingly, the P-QOL scores declined if POP was cured, which means that the P-QOL scores are considerably associated with pre- and postoperative POP-related conditions.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a single-center, retrospective study. Second, the patient sample was relatively small. Finally, the median postoperative observation period was 24.6 months, which appeared to be a little short. Despite these limitations, this study presents the usefulness of P-QOL reflecting the difference in postoperative outcomes between the two surgical methods.

CONCLUSION

P-QOL scores are sufficiently affected by the surgical outcomes of POP. P-QOL scores can be used to assess the postoperative conditions, as well as IPSS, OABSS, and ICIQ-SF.

Author contributions

Data collection and analysis were performed by Kenji Kuroda, Koetsu Hamamoto, Kazuki Kawamura, Ayako Masunaga. Project development was developed by Akio Horiguchi and Keiichi Ito. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kenji Kuroda and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biler A, Ertas IE, Tosun G, Hortu I, Turkay U, Gultekin OE, et al. Perioperative complications and short-term outcomes of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, and laparoscopic pectopexy for apical prolapse. Int Braz J Urol. 2018;44:996–1004. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2017.0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Prediction model and prognostic index to estimate clinically relevant pelvic organ prolapse in a general female population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1013–21. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forde JC, Chughtai B, Anger JT, Mao J, Sedrakyan A. Role of concurrent vaginal hysterectomy in the outcomes of mesh-based vaginal pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:1183–95. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvie HS, Honeycutt AA, Neuwahl SJ, Barber MD, Richter HE, Visco AG, et al. Responsiveness and minimally important difference of SF-6D and EQ-5D utility scores for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:265.e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obinata D, Sugihara T, Yasunaga H, Mochida J, Yamaguchi K, Murata Y, et al. Tension-free vaginal mesh surgery versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse: Analysis of perioperative outcomes using a Japanese national inpatient database. Int J Urol. 2018;25:655–9. doi: 10.1111/iju.13587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei D, Wang P, Niu X, Zhao X. Comparison between laparoscopic uterus/sacrocolpopexy and total pelvic floor reconstruction with vaginal mesh for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:915–22. doi: 10.1111/jog.13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu CK, Tsai CP, Chou MM, Shen PS, Chen GD, Hung YC, et al. Acomparative study of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy and total vaginal mesh procedure using lightweight polypropylene meshes for prolapse repair. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:552–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park YH, Yang SC, Park ST, Park SH, Kim HB. Laparoscopic reconstructive surgery is superior to vaginal reconstruction in the pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11:1082–8. doi: 10.7150/ijms.9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sukgen G, Türkay Ü. Effect of pelvic organ prolapse reconstructive mesh surgery on the quality of life of Turkish Patients: A prospective study. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2020;9:204–8. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_32_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takazawa N, Fujisaki A, Yoshimura Y, Tsujimura A, Horie S. Short-term outcomes of the transvaginal minimal mesh procedure for pelvic organ prolapse. Investig Clin Urol. 2018;59:133–40. doi: 10.4111/icu.2018.59.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aubé M, Guérin M, Rheaume C, Tu LM. Efficacy and patient satisfaction of pelvic organ prolapse reduction using transvaginal mesh: A Canadian perspective. Can Urol Assoc J. 2018;12:E432–7. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotani Y, Murakamsi K, Kai S, Yahata T, Kanto A, Matsumura N. Comparison of surgical results and postoperative recurrence rates by laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with other surgical procedures for managing pelvic organ prolapse. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2021;10:221–5. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_127_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotani Y, Murakami K, Kanto A, Takaya H, Nakai H, Matsumura N. Measures for safe laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography and perioperative ultrasonography. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2021;10:114–6. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_1_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato H, Otsuka S, Abe H, Miyagawa T. Medium-term risk of recurrent pelvic organ prolapse within 2-Year Follow-Up after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2023;12:38–43. doi: 10.4103/gmit.gmit_59_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuroda K, Hamamoto K, Kawamura K, Masunaga A, Kobayashi H, Horiguchi A, et al. Favorable postoperative outcomes after transvaginal mesh surgery using a Wide-Arm ORIHIME®Mesh. Cureus. 2024;16:e53388. doi: 10.7759/cureus.53388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuroda K, Hamamoto K, Kawamura K, Kobayashi H, Horiguchi A, Ito K. Efficacy of transvaginal surgery using an ORIHIME mesh with wider arms and adjusted length. Cureus. 2024;16:e57106. doi: 10.7759/cureus.57106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Digesu GA, Khullar V, Cardozo L, Robinson D, Salvatore S. P-QOL: A validated questionnaire to assess the symptoms and quality of life of women with urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:176–81. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wattiez A, Boughizane S, Alexandre F, Canis M, Mage G, Pouly JL, et al. Laparoscopic procedures for stress incontinence and prolapse. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1995;7:317–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeyama M, Ikeda S, Kobayashi M, Sugimoto T, Kato C, Kiuchi H, et al. Validation of the Prolapse Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (P-QOL) in Japanese version in Japanese women. J Jpn Continence Soc. 2014;25:327–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukumoto Y, Uesaka Y, Yamamoto K, Ito S, Yamanaka M, Takeyama M, et al. Assessment of quality of life in women with pelvic organ prolapse: Conditional translation and trial of P-QOL for use in Japan. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;99:531–42. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol1989.99.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozet F, Mandron E, Arroyo C, Andrews H, Cathelineau X, Mombet A, et al. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy approach for genito-urinary prolapse: Experience with 363 cases. Eur Urol. 2005;47:230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawada Y, Kitagawa Y, Hayashi T, Tokiwa S, Nagae M, Cortes AR, et al. Clinical outcomes after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse: A 3-year follow-up study. Int J Urol. 2021;28:216–9. doi: 10.1111/iju.14436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obut M, Oğlak SC, Akgöl S. Comparison of the quality of life and female sexual function following laparoscopic pectopexy and laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy in apical prolapse patients. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2021;10:96–103. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_67_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belayneh T, Gebeyehu A, Adefris M, Rortveit G. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the cross-cultural adaptations and translations of the Prolapse Quality of Life (P-QoL) questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1989–2000. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-03920-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Methods for assessing responsiveness: A critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:459–68. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber MD, Walters MD, Cundiff GW PESSRI Trial Group. Responsiveness of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) in women undergoing vaginal surgery and pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1492–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aponte MM, Rosenblum N. Repair of pelvic organ prolapse: What is the goal? Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15:385. doi: 10.1007/s11934-013-0385-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.