Summary

Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 exhibits the anti-ovarian cancer activity by modulating aerobic glycolysis, but its role in reprogramming sterol metabolism remains unclear. This research utilized transcriptomic and lipidomic to identify the key metabolic pathways and targets influenced by 20(S)-Rg3. 20(S)-Rg3 altered 175 mRNAs and 64 metabolites in ovarian cancer cells, and cluster analysis found that the differentially expressed genes and metabolites were highly associated with the steroid biosynthesis. Multi-omics analysis revealed squalene epoxidase (SQLE), a rate-limiting enzyme in steroid biosynthesis, was upregulated by 20(S)-Rg3. Silencing of SQLE attenuated the inhibitory effects of 20(S)-Rg3 on ovarian cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo, as well as cell migration, invasion, and cholesterol synthesis. 20(S)-Rg3 enhanced SQLE expression by downregulating HIF-1α. Co-immunoprecipitation confirmed the interaction between SQLE and farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 (FDFT1), another rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol metabolism. These findings suggest that 20(S)-Rg3 exerts anti-ovarian cancer effects by HIF-1α/SQLE/FDFT1 to reprogram cholesterol metabolism.

Subject areas: cancer, health sciences, medical biochemistry, natural product chemistry, secondary metabolite sources

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

20(S)-Rg3 reprograms sterol metabolism via upregulating SQLE in ovarian cancer

-

•

SQLE silencing reverses 20(S)-Rg3's suppression on growth, migration and cholesterol synthesis

-

•

20(S)-Rg3 upregulates SQLE by downregulating HIF-1α

Cancer; Health sciences; Medical biochemistry; Natural product chemistry; Secondary metabolite sources

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most malignant gynecological cancers. Despite the advancements in treatment options, the five-year survival rate remains low. Advanced ovarian cancer is characterized by widespread and rapid metastasis to the peritoneal cavity, contributing to its poor prognosis. The malignant progression of ovarian cancer confers a series of metabolic changes, such as glycol-metabolism and lipid metabolism, which further support its malignancy.1,2,3,4 Therefore, identifying key metabolism-modulating genes in ovarian cancer is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms underlying disease progression and for developing effective targeted therapies.

Ginseng, a traditional herb, is gaining popularity worldwide because of its pharmacological properties.5,6,7 Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 is an active ginsenoside saponin monomer extracted from red ginseng that presents anti-tumor activities in various cancers.8,9,10 Studies have shown that 20(S)-Rg3 significantly inhibits ovarian cancer cells' growth and metastasis, partly by suppressing aerobic glycolysis.11,12 However, the effects of 20(S)-Rg3 on other metabolic pathways in ovarian cancer remain poorly understood. A comprehensive examination of the pivotal genes mediating the metabolism-modulating activity of 20(S)-Rg3 within ovarian cancer cells could significantly advance the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Squalene epoxidase (SQLE) catalyzes the conversion of squalene to monooxy squalene, which is the rate-limiting step in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. The evidence regarding the function of SQLE in cancer are inconsistent. In some types of cancer, such as lung squamous cell, colon and pancreatic cancer, SQLE acts as a proto-oncogene.13,14,15 But in other cancers, SQLE exerts a suppressive function that the downregulation of SQLE accelerates colorectal cancer progression and metastasis.16 To date, little is known about the role of SQLE in ovarian cancer.

Integrated multi-omics analysis provides significant advantages for the in-depth exploration of the complex mechanisms underlying disease development and progression. The combinatorial analysis of multi-omics data can reveal important interactions among different levels to facilitate the study of biological phenotypes and regulatory mechanisms, and compensate for missing data and noise in single-omics analysis.

In this study, we integrated transcriptomic and targeted lipidomic analyses to identify SQLE as a hub gene mediating the anticancer activity and metabolic reprogramming effect of 20(S)-Rg3 in ovarian cancer cells.

Results

20(S)-Rg3 altered the transcriptome profile of ovarian cancer cells

To investigate the anti-cancer mechanism of 20(S)-Rg3 in ovarian cancer, next-generation sequencing was performed to identify the 20(S)-Rg3-influenced mRNAs in SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells. Raw mRNA sequencing data were submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database with GEO accession number GSE118216 (GEO: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE118216). A total of 13,251 mRNAs were detected, among which 122 mRNAs were significantly decreased and 53 mRNAs were significantly increased by 20(S)-Rg3 in SKOV3 cells (fold change >1.5, or <0.67, p < 0.05, FDR <0.05; Figures 1A and S1). GO annotation indicated that the differentially expressed mRNAs were involved in a variety of biological processes such as cholesterol biosynthesis, steroid biosynthesis, and sterol biosynthesis (Figure 1B). KEGG pathway analysis showed that the differentially expressed mRNAs were involved in nine pathways: steroid biosynthesis (the most significantly enriched pathway), terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, metabolic pathways, ovarian steroidogenesis, phenylalanine metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, steroid hormone biosynthesis, PPAR signaling pathway, and butanoate metabolism (Figure 1C). Specifically, eight mRNAs, involved in steroid biosynthesis, were upregulated in 20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 cells, including FDFT1 (20(S)-Rg3 vs. NC, 2.17), SQLE (3.24), LSS (2.43), CYP51A1 (2.48), MSMO1 (4.03), NSDHL (2.18), HSD17B7 (2.31), and SC5D (2.00).

Figure 1.

20(S)-Rg3 induced the differential expression of 175 genes, mainly enriched in cholesterol biosynthetic, steroid biosynthetic, and sterol biosynthetic pathways

(A) Heatmap of the 53 upregulated mRNAs in the 20(S)-Rg3 treatment group (EXP) vs. the control group (NC).

(B) GO biological process analysis of the differentially expressed mRNAs.

(C) KEGG pathway analysis of the differentially expressed genes.

20(S)-Rg3 changed the lipid metabolites profile in SKOV3 cell

A total of 540 metabolites were detected in 20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 cells and negative control cells using LC-MS/MS. To ensure the significant inter-group differences while maintaining low intra-group variation, the principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure 2A), and partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) model were constructed. The model evaluation parameters (R2X = 0.727, R2Y = 1, and Q2 = 0.965) indicated high stability and reliability, as values closer to 1 reflect a more robust model (Figure 2B). A total of 36 metabolites were significantly upregulated, 28 were downregulated, and 476 remained unchanged in 20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 cells compared to the negative control group in the volcano plot (Figure 2C). The 64 differentially expressed metabolites were classified into five major categories: glycerol phosphate (GP), glycerol lipid (GL), sterol lipids (ST), fatty acids (FA), and sphingolipids (SL) (Figure 2D). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the primary enriched pathways were: metabolic pathways (83.33%), glycerophospholipid metabolism (68.52%), retrograde endocannabinoid signaling (44.44%), fat digestion and absorption (27.78%), cholesterol metabolism (25.93%), and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis (25.93%) (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Differential lipid metabolite changes induced by 20(S)-Rg3 in SKOV3 cells

(A) PCA three-dimensional diagram. The PCA analysis revealed distinct clustering characteristics among the three groups: control (NC) represented by green dots, the experimental group (EXP) indicated by red dots, and the quality control group (Mix) depicted in purple.

(B) OPLS-DA model validation diagram. The OPLS-DA model provided insights into the classification effectiveness of the groups. The x-axis represents the model accuracy, and the y axis indicates the frequency of model classification outcomes. A threshold of p < 0.05 indicates the optimal model performance.

(C) Volcano plot of differential metabolites. The volcano plot illustrates the distribution of metabolites, highlighting 36 metabolites that were significantly upregulated (red circles) and 28 metabolites that were significantly downregulated (green circles). A total of 476 metabolites showed no significant change (gray circles).

(D) Clustering heatmap of differential metabolites. The heatmap illustrates the relationships among metabolites, with the following abbreviations for key metabolites: GP (Glycerol Phosphate), GL (Glycerol Lipid), ST (Sterol lipids), FA (Fatty Acids), and SL (Sphingolipids).

(E) KEGG pathway analysis of differential metabolites. The KEGG classification diagram annotates the number of differentially regulated metabolites in respective pathways, along with their proportion relative to the annotated total.

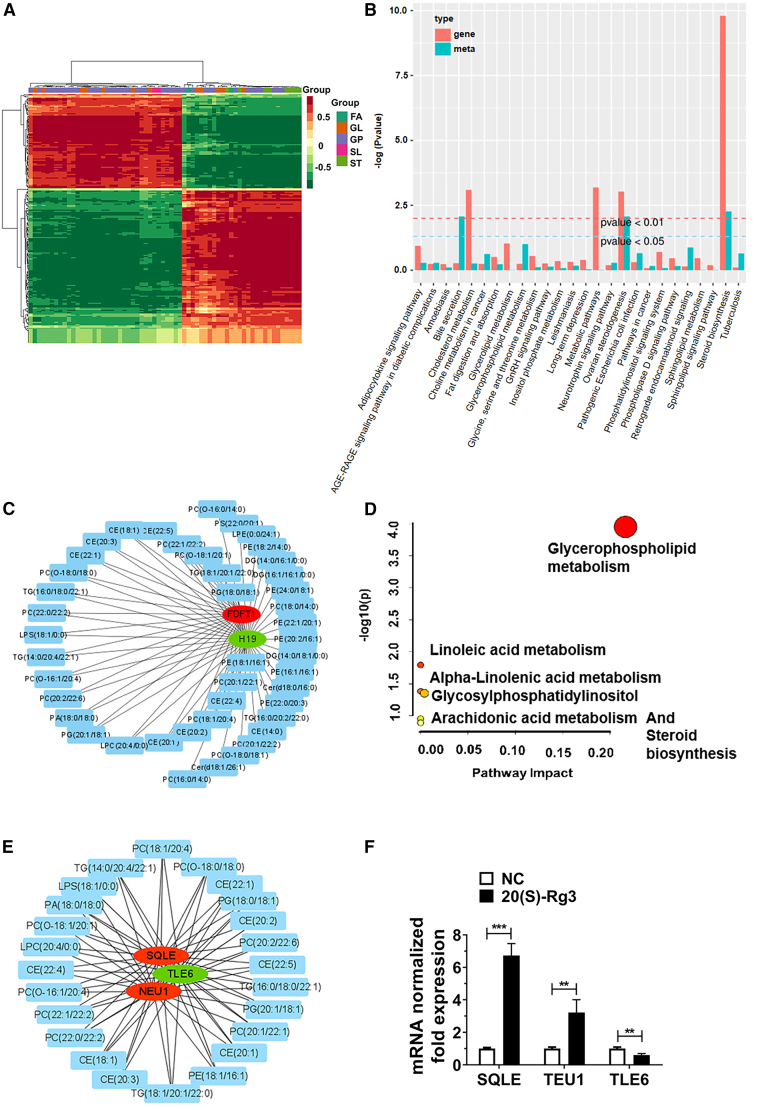

Combined analysis of transcriptomics and lipidomics data identified SQLE as a 20(S)-Rg3-modulated hub gene in ovarian cancer

To elucidate the mechanism responsible for the 20(S)-Rg3-induced lipid metabolic changes in SKOV3 cells at the transcriptomic level, we constructed a fully connected network involving 64 differential metabolites and 175 differentially expressed genes through integrated analyses of targeted lipidomics and transcriptomics. Clustering analysis of the differential metabolites and gene correlation coefficients identified five major classes of substances: FA, GP, GL, SL, and ST (Figure 3A). Further integrated analyses of differential metabolites and gene enrichment highlighted several critical pathways involved in 20(S)-Rg3-treated ovarian cancer cells, including ovarian steroidogenesis, cholesterol metabolism, and steroid biosynthesis (Figure 3B). In view of our previous findings that 20(S)-Rg3 downregulated H19 and upregulated farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 (FDFT1) to inhibit the malignant phenotypes of ovarian cancer cells, we utilized Cytoscape to identify metabolites associated with H19 or FDFT1 (Figure 3C). The identified 24 metabolites included Phosphatidylcholine (PC): PC (18:1/20:4), PC (20:1/22:1), PC (22:0/22:2), PC (22:1/22:2), PC (20:2/22:6), PC (O-18:0/18:0), PC (O-18:1/20:1), PC (O-16:1/20:4); Phosphatidylglycerol (PG): PG (18:0/18:1), PG (20:1/18:1); Triglyceride (TG):TG (16:0/18:0/22:1), TG (18:1/20:1/22:0), TG (14:0/20:4/22:1); Phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE): PE (18:1/16:1); Cholesterol ester (CE): CE (18:1), CE (20:1), CE (22:1), CE (20:2), CE (20:3), CE (22:4), CE (22:5); Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC): LPC (20:4/0:0); Lysophosphatidylserine (LPS): LPS (18:1/0:0), and Phosphatidic acid (PA): PA (18:0/18:0). The relationship of these 24 metabolites with various metabolic pathways, such as Glycerophospholipid metabolism, Linoleic acid metabolism, Alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism, Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) biosynthesis, Arachidonic acid metabolism, and Steroid biosynthesis, was analyzed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (Figure 3D and Table 1). Among these, Glycerophospholipid metabolism emerged as the most dysregulated pathway, as evidenced by its maximal bubble diameter in the critical quadrant. The quantity of the differential metabolites in the steroid biosynthesis pathway is the greatest. The mRNAs associated with these 24 metabolites were further analyzed, and squalene epoxidase (SQLE), neuraminidase 1 (NEU1), and TLE family member 6, subcortical maternal complex member (TLE6) were ultimately identified (Figure 3E). Real-time quantitative PCR results showed the relative expression levels of these genes in 20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 cells vs. negative control cells were as follows: SQLE (6.73, p < 0.001), NEU1 (3.21, p < 0.01), and TLE6 (0.61, p < 0.01), among which SQLE was the most significantly upregulated gene by 20(S)-Rg3 (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

SQLE was a 20(S)-Rg3-stimulated gene crucial for lipid metabolic changes in ovarian cancer cells

(A) Cluster heatmap of correlation coefficient between differential genes and metabolites. Differential metabolites with correlation coefficients above 0.8 were selected for calculation and analysis.

(B) Histogram of differential metabolite and gene enrichment analysis. The enrichment degree of the pathway with both differential metabolites and differential genes was shown, and the higher the ordinate, the higher the enrichment degree.

(C) Metabolites associated with H19 or FDFT1 were analyzed using Cytoscape. Ellipse: genes; Round Rectangle: metabolites; Red: upregulated; Green: downregulated.

(D) Bubble diagram of significantly differed pathways by MetaboAnalyst. The pathways with large bubbles in the upper right quadrant are typically the core differential pathways. The horizontal axis represents pathway impact and the vertical axis represents -log10.

(E) SQLE, TEU1, and TLE6 were closely linked to 24 20(S)-Rg3-related metabolites in the Cytohubba and Metscape analysis.

(F) Relative mRNA expression of SQLE, TEU1 and TLE6 genes in 20(S)-Rg3 treated SKOV3 cells versus negative control cells. Significance :∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Table 1.

The table of differential pathway analysis using MetaboAnalyst

| No. | Pathways | Total | Impact | Expected | −log10(p) | Holm adjust |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 36 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 3.95E+00 | 9.37E-03 |

| 2 | Linoleic acid metabolism | 5 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.79E+00 | 1.00E+00 |

| 3 | Alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism | 13 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 1.38E+00 | 1.00E+00 |

| 4 | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol | 14 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.35E+00 | 1.00E+00 |

| 5 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | 36 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 9.55E-01 | 1.00E+00 |

| 6 | Steroid biosynthesis | 42 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 8.91E-01 | 1.00E+00 |

Total represents the total number of compounds in the pathway. Impact is the pathway impact value calculated from the pathway topology analysis. Holm adjust is the p value adjusted by the Holm-Bonferroni method.

20(S)-Rg3 upregulated squalene epoxidase gene in ovarian cancer cells

To further validate the effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on SQLE expression in ovarian cancer cells, qPCR and Western blot were conducted and the results showed that SQLE was increased at both mRNA and protein levels in 20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 and 3AO cells compared to the negative control cells (Figures 4A, 4B, and S2). Cellular immunofluorescence assays showed that SQLE was located in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of ovarian cancer cells, and that the level of SQLE protein was significantly increased in 20(S)Rg3-treated cells (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

20 (S)-Rg3 upregulated SQLE in ovarian cancer cells

(A) SQLE mRNA level was elevated by 20(S)-Rg3 in SKOV3 and 3AO cells. Statistics were based on three independent experiments. Asterisks indicated statistical significance (∗∗∗p < 0.001).

(B) 20(S)-Rg3 increased SQLE protein level in SKOV3 and 3AO cells.

(C) Cell immunofluorescence assay showed SQLE was increased in 20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 and 3AO cells relative to negative control cells. Scale was 25 μm.

20(S)-Rg3 suppressed ovarian cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion by upregulating squalene epoxidase gene

To determine the role of SQLE in the anticancer activity of 20(S)-Rg3, SQLE was inhibited by siRNA in 20(S)-Rg3-treated cells (Figures 5A, 5B, and S3). EdU cell proliferation, plate colony formation assays and Transwell assays showed that knockdown of SQLE reversed the inhibitory effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on cell proliferation (Figures 5C and 5D), migration, and invasion (Figure 5E) in SKOV3 and 3AO cells. These results indicated that SQLE upregulation mediated the anti-ovarian cancer activity of 20(S)-Rg3.

Figure 5.

Knocking down of SQLE mitigated the anti-ovarian cancer activity of 20(S)-Rg3

(A) Knocking down of SQLE reduced SQLE in 20(S)-Rg3-treated cells at mRNA level. Statistical significance :∗p < 0.05.

(B) SQLE was decreased at protein level by siRNA transfection in 20(S)-Rg3-treated cells.

(C) Knocking down of SQLE reversed the inhibitory effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on cell proliferation as shown by EdU cell proliferation assay. Scale was 25 μm.

(D) 20(S)-Rg3 impaired the plate colony formation ability of ovarian cancer cells, which was offset by SQLE siRNA.

(E) SQLE interference weakened the inhibitory effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on the in vitro migration and invasion of SKOV3 and 3AO cells. Scale was 50 μm.

20(S)-Rg3 reprogrammed cholesterol metabolism of ovarian cancer cells via squalene epoxidase gene and farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1

To elucidate the reprogramming effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on cholesterol metabolism in ovarian cancer cells, we measured the relative levels of free cholesterol and cholesteryl esters in SKOV3 and 3AO cells. The results indicated that 20(S)-Rg3 significantly reduced the intracellular levels of free cholesterol and cholesteryl esters in ovarian cancer cells, an effect that was reversed by the knockdown of SQLE (Figures 6A and 6B). Additionally, the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA: http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/)17 utilizing TCGA (OV Tumor) and GTEx (Ovary) expression datasets revealed a significant positive correlation between SQLE and FDFT1 (R = 0.26, p = 7.2e-08) (Figure 6C). To further investigate the relationship between SQLE and FDFT1, the mRNA expression of FDFT1 was examined and the results showed FDFT1 was upregulated by 20(S)-Rg3 in both SKOV3 and 3AO cells (Figure 6D). The enhanced expression of FDFT1 was attenuated by SQLE small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figures 6E, 6F, and S3). But the inhibition of FDFT1 did not affect the expression of SQLE in 20(S)-Rg3-treated cells (Figures 6G and S4). Immunoprecipitation assays confirmed the interaction between SQLE and FDFT1 (Figures 6H and S5). And immunofluorescence co-localization studies indicated that both SQLE and FDFT1 proteins were localized in the nucleus and plasma membrane, with higher expression levels of fluorescently labeled SQLE and FDFT1 in 20(S)-Rg3-treated cells compared to the negative control group (Figure 6I). Therefore, in ovarian cancer cells, 20(S)-Rg3 concurrently upregulated the expression of SQLE and FDFT1, and SQLE stimulated FDFT1, thereby reprogramming cellular cholesterol metabolism in ovarian cancer.

Figure 6.

20(S)-Rg3 modulated cholesterol metabolism by upregulating SQLE in ovarian cancer cells

(A and B) SQLE inhibition reversed the inhibitory effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on intracellular free cholesterol and cholesterol ester. Statistical significance :∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(C) The expression correlation between SQLE and FDFT1 evaluated by GEPIA.

(D) 20(S)-Rg3-stimulated FDFT1 mRNA level in SKOV3 and 3AO cells detected by real-time PCR. Statistical significance :∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(E and F) Knockdown of SQLE expression reversed the upregulation of FDFT1 caused by 20(S)-Rg3 at both mRNA and protein levels.Statistical significance :∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(G) Knocking down FDFT1 in SKOV3 and 3AO cells did not affect SQLE protein expression induced by 20(S)-Rg3.

(H) Immunoprecipitation results showed the interaction between SQLE and FDFT1. IgG served as the negative control. Input as the positive control and anti-FDFT1-IP as the experimental sample.

(I) Cellular immunofluorescence assays revealed the co-localization of SQLE and FDFT1. SQLE protein was labeled with red fluorescence, FDFT1 protein was labeled with green fluorescence, and DAPI-stained nucleus was labeled with blue fluorescence. The scale bar is 75 μm.

Squalene epoxidase gene was negatively regulated by HIF-1α in ovarian cancer cells

Based on the previous results that 20(S)-Rg3 downregulated HIF-1α, the relationship between HIF-1α and SQLE was then investigated.18 20(S)-Rg3 significantly reduced HIF-1α protein level in SKOV3 and 3AO cells (Figure 7A). 20(S)-Rg3-induced SQLE expression was reversed by the overexpression of HIF-1α at both mRNA and protein levels (Figures 7B, 7C, and S6). Knockdown of HIF-1α led to an upregulation of SQLE at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figures 7D, 7F, and S7). In parallel, the overexpression of HIF-1α in SKOV3 and 3AO cells resulted in a downregulation of SQLE (Figures 7G–7I and S6). But when SQLE and FDFT1 were silenced in SKOV3 and 3AO cells, HIF-1α protein expression remained unchanged (Figures 7J, 7K, S3, and S4). In summary, HIF-1α negatively correlated with SQLE, and 20(S)-Rg3 upregulated SQLE expression through downregulating HIF-1α in ovarian cancer.

Figure 7.

20(S)-Rg3 downregulated HIF-1α to upregulate SQLE

(A) 20(S)-Rg3 reduced HIF-1α protein level in SKOV3 and 3AO cells.

(B and C) Overexpression of HIF-1α suppressed 20(S)-Rg3-induced SQLE upregulation at mRNA and protein levels.Statistical significance :∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D–F) Knocking down HIF-1α increased SQLE at both mRNA and protein levels.Statistical significance :∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(G–I) Overexpression of HIF-1α downregulated mRNA and protein levels of SQLE.Statistical significance :∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(J and K) Inhibition of SQLE and FDFT1 did not recover 20(S)-Rg3-reduced HIF-1α protein level.

Squalene epoxidase gene knockdown promoted subcutaneous tumor formation in nude mice

To determine the role of SQLE in ovarian carcinogenesis in vivo, SQLE was stably knocked down in SKOV3 cells with shSQLE lentivirus combined with puromycin selection (Figures 8A–8C and S8). The constructed cells were injected subcutaneously into 5-week-old female nude mice, and the weights of the nude mice and the sizes of the subcutaneous xenografts were recorded every other day for 23 days. There was no significant difference in body weights between the control group and the shSQLE group (p > 0.05, Figure 8D), but the volumes of the subcutaneous xenografts of the shSQLE group was significantly larger than those of the control group (p < 0.01, Figures 8E and 8F). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the xenograft tissues were shown in Figure 8G. The immunohistochemical staining showed that the expression level of SQLE protein in the shSQLE group was significantly lower than that in the control group (Figure 8H). These results indicated that knockdown of SQLE could promote tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 8.

Knocking down of SQLE by shSQLE-lentivirus promoted tumor growth in ovarian cancer cell line-derived subcutaneous xenograft models

(A) The images of SKOV3 cells infected by shSQLE lentivirus and control virus LV3-NC carrying GFP. The scale is 50 μm.

(B, C) SQLE was knocked down by shSQLE lentivirus verified by qPCR and Western blot. Statistical significance: ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) No changes of mice body weights were observed between shSQLE and LV3-NC groups.

(E) The subcutaneous tumor volumes were larger in nude mice of the shSQLE group than in the LV3-NC group.

(F) The images of subcutaneous tumors after 23 days of inoculation.

G) Images of H&E staining of xenograft tissues. Representative H&E staining of xenograft tissues (n = 3 per group) showed the presence of ovarian cancer cell morphology. The scale is 50 μm.

(H) Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of SQLE in xenograft tissues. According to the H-score system, the expression of SQLE protein was downregulated in the subcutaneous xenograft tumor tissues of shSQLE group nude mice compared with the control group. The scale is 50 μm.

Squalene epoxidase gene inhibition reversed the in vivo anti-cancer activity of 20(S)-Rg3

During the process of the establishment of the subcutaneous xenograft models in nude mice, subcutaneous xenografts were observed in the shSQLE group on the seventh day after cell inoculation. Monotherapy with 20(S)-Rg3 resulted in an 84.5% reduction in tumor volume compared to PBS-treated controls at the experimental endpoint (0.11 ± 0.06 g vs. 0.71 ± 0.26 g, p < 0.01). This anti-tumor effect was partially attenuated in the shSQLE+20(S)-Rg3 group, with an 85.9% recovery in tumor volume relative to the 20(S)-Rg3 group (0.78 ± 0.22 g vs. 0.11 ± 0.06 g, p < 0.01) (Figures 9A and 9B). The dynamic curve of the volume increase of subcutaneous xenografts further validated the aforementioned results (Figure 9C). Thereby, shRNA-mediated SQLE knockdown significantly rescued tumor proliferative capacity in 20(S)-Rg3-treated xenografts. The body weight of the mice increased significantly over time in the three groups, and no significant differences were observed among groups (Figure 9D). H&E staining demonstrated the structural integrity and organization of tissues in all groups (Figure 9F). Western blotting and immunohistochemical staining results indicated that the expression of SQLE protein was increased in the 20(S)-Rg3 group, and the knockdown of SQLE eliminated the upregulatory effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on SQLE (Figures 9E, 9G, and S9). This pharmacological-genetic epistasis confirmed SQLE as the indispensable molecular target of 20(S)-Rg3.

Figure 9.

Knocking down of SQLE interfered the therapeutic effects of 20(S)-Rg3 in ovarian cancer xenografts

(A) Representative images of subcutaneous tumors (left panel) and corresponding excised masses (right panel) at experimental endpoint (Day 25). BALB/c nude mice (n=5/group) were randomly allocated into three experimental cohorts: control lentivirus (LV3-NC)+PBS administration; LV3-NC+20(S)-Rg3 monotherapy; and shSQLE+20(S)-Rg3 combination.

(B) Terminal tumor weights demonstrating 84.5% reduction in 20(S)-Rg3 monotherapy group (0.11 ± 0.06 g) vs. control group (0.71 ± 0.26 g, p < 0.01), with partial recovery (85.9%) in the shSQLE+20(S)-Rg3 group (0.78 ± 0.22 g). Statistical significance: ∗∗p < 0.01.

(C) Tumor growth curves validating therapeutic dynamics (20(S)-Rg3 monotherapy group vs. control group: p < 0.01; shSQLE+20(S)-Rg3 group vs. 20(S)-Rg3 monotherapy group: p < 0.01). Statistical significance: ∗∗p < 0.01.

(D) Body weight trajectories showed time-dependent weight gain.

(E) Histopathological evaluation of xenografts by H&E staining. Scale bar is 100 μm (black).

(F) IHC results showed SQLE upregulation by 20(S)-Rg3 was reversed by SQLE knocking down. Scale bar is 100 μm (black).

(G) Western blot analyses demonstrated that 20(S)-Rg3-induced SQLE upregulation was abolished by shSQLE knockdown.

Discussion

Our previous studies showed that 20(S)-Rg3 exerted anti-ovarian cancer activity partially by upregulated FDFT1, one of the rate-limiting enzymes regulating cholesterol biosynthesis.19,20 Therefore, we conducted targeted lipidomics to observe lipometabolism changes stimulated by 20(S)-Rg3, and combined these changes with transcriptomic sequencing data to identify the crucial target mediating the effect of 20(S)-Rg3 to reprogram cholesterol metabolism. 64 metabolites and 175 mRNAs were found modulated by 20(S)-Rg3 in SKOV3 cells. Of note, SQLE, a rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis, was found upregulated by 20(S)-Rg3.

SQLE gene is located on human chromosome 8q24, acting as a key rate-limiting enzyme catalyzing sterol and cholesterol biosynthesis.21,22,23 SQLE has been found associated with cancer, but the functions of SQLE in tumors are inconsistent. SQLE is highly expressed in pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer, acts as a pro-cancer gene to promote tumor cell proliferation and invasion.24,25,26 Interestingly, studies have suggested that SQLE promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer, while another study has reported that the downregulation of SQLE accelerates the progression and metastasis of colorectal cancer.14,16,27 The role of SQLE has not been fully studied in ovarian cancer.

Our study showed that SQLE knockdown promoted the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells in vitro and in vivo, and reversed the inhibitory effect of 20(S)-Rg3 on the invasion and migration of ovarian cancer cells. Our previous studies have shown that 20(S)-Rg3 upregulates FDFT1 to inhibit ovarian cancer progression.19 FDFT1 and SQLE are two key enzymes catalyzing the cholesterol biosynthesis process. The interaction between these two molecules remains largely unknown. In this study, the interaction between SQLE and FDFT1 was verified via online database analyses of the expression correlation, and experimental evidence of subcellular co-localization and co-IP. Of note, SQLE knockdown caused FDFT1 reduction at mRNA and protein levels, but not vice versa. Studies still need to explore the mechanism responsible for the promoting effect of SQLE on FDFT1 transcription. The present data indicate that 20(S)-Rg3 stimulates SQLE and FDFT1 expression and interaction to reprogram cholesterol biosynthesis and abrogate the malignant phenotypes of ovarian cancer cells.

Tumor cells exhibit metabolic abnormalities that counterbalance the elevated energy and biosynthetic demands associated with rapid tumor growth and cell division, such as altered cholesterol/lipid metabolism.28,29,30,31 20(S)-Rg3 modulates cholesterol biosynthetic/metabolic processes, steroid biosynthetic/metabolic processes, and ovarian steroidogenesis in ovarian cancer. SQLE knockdown recovered 20(S)-Rg3-reduced intracellular free cholesterol and cholesteryl esters. Since 20(S)-Rg3 affected other enzymes involved in cholesterol metabolism as revealed by transcriptomic sequencing, including EBP, SC5D, DHCR7, and DHCR24, 20(S)-Rg3 could reduce the distal to proximal cholesterol metabolism.

A systematic pan-cancer analysis has found that key metabolic genes are closely associated with hypoxia.32 SQLE is the first rate-limiting enzyme in the cholesterol biosynthesis that requires molecular oxygen. Our results showed that SQLE expression was negatively regulated by HIF-1α. Our previous studies have exhibited that 20(S)-Rg3 activates the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to promote HIF-1α degradation and reduce HIF-1α protein level.33 While the precise molecular mechanism underlying the HIF-1α-mediated suppression of SQLE transcriptional activity remains to be fully elucidated, our data reveal that 20(S)-Rg3 potentiates SQLE expression through HIF-1α attenuation. This discovery delineates a previously unrecognized 20(S)-Rg3/HIF-1α/SQLE signaling axis governing the metabolic reprogramming in ovarian carcinogenesis.

In conclusion, the metabolic rearrangement of tumors is not just an incidental phenomenon of tumorigenesis, but is one of the key components contributing to cancer. Targeting dysregulated metabolism may be an effective strategy for suppressing tumor growth. SQLE inhibits the malignant phenotypes of ovarian cancer. 20(S)-Rg3 exerts anti-ovarian cancer activity via modulating HIF-1α-SQLE-FDFT1-cholesterol pathway. 20(S)-Rg3 is a potential anti-cancer therapeutic option for ovarian cancer.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we revealed that 20(S)-Rg3 suppressed HIF-1α and upregulated SQLE to reprogram cholesterol metabolism and inhibit the malignant phenotypes of ovarian cancer. However, the mechanism by which HIF-1α inhibits SQLE was not elucidated. Subsequently, we will conduct further in-depth studies on this specific regulatory mechanism.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xu Li (lixu56@mail.xjtu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

The Raw mRNA sequencing data reported in this study have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. It is publicly available. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

The data from this study are presented in the text and supplementary materials. The datasets will be made available to the lead contact upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2024JC-YBQN-0800 and 2023-JC-QN-0872), and the Institutional Foundation of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’ an Jiaotong University (Grant No. 2021ZYTS-28 and 2022MS-19).

Author contributions

F.H. and L.Z. wrote the original draft, performed the formal analysis, and performed the functional experiments. Y.Y.Z.: Transcriptomic experiments. J.F.: Investigation and formal analysis. S.X.C.: Cell culture. X.C.: Western blot. Z.Z.F.: Plasmid extraction and cell transfection. L.Z. and X.L. designed the study and reviewed the article critically.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-SQLE | Santa Cruz | Sc-271651; RRID: AB_10708249 |

| Anti-FDFT1 | Proteintech | 13128-1-AP; RRID: AB_2294094 |

| Anti-FDFT1 | Abcam | Ab195046; RRID: AB_2860018 |

| Anti-HIF-1α | Abcam | H1alpha67 |

| β-actin | Cell Signaling Technology | 3700; RRID: AB_2242334 |

| Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | 7076; RRID: AB_330924 |

| Anti- goat IgG, HRP-linked Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | 7074; RRID: AB_2099233 |

| goat anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor 647) | Abcam | ab150115; RRID: AB_2687948 |

| goat anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor 488) | Abcam | ab150113; RRID: AB_2576208 |

| goat anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor 488) | Abacm | ab150077; RRID: AB_2630356 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| shSQLE lentivirus | GenePharma | SH750 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 | Tasly Pharmaceutical Company | PCM-YMC-017 |

| Trizol | Invitrogen | 15596018 |

| siHIF-1α | Santa Cruz | Sc-35561 |

| X-treme GENE™ transfection reagent | Roche | 04476093001 |

| X-treme GENE HP DNA transfection reagent | Roche | 06366236001 |

| RIPA lysis buffer | Beyotime | P0013B |

| Matrigel | Corning | 356234 |

| protein A/G magnetic beads | Millipore | LSKMAGAG02 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit | TaKaRa | RR047A |

| TB Green Premix Ex Taq™ II kit | TaKaRa | RR820 |

| bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) protein assay kit | CWBIO | CW0014 |

| The Ion Total RNA-Seq Kit v2.0 | ThermoFisher | 4479789 |

| EdU assays | RIBO | R11053.9 |

| Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit | Invitrogen | A12216 |

| SP Histochemistry Kit | ZSGB-BIO | SP-9000 |

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell lines

Human ovarian cancer cell lines SKOV3 and 3AO were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C under 5% CO₂ humidified atmosphere.

Transient knockdown: siRNA transfection was performed using X-tremeGENE™ siRNA Transfection Reagent, following the manufacturer's protocol.

Transient overexpression: Plasmid transfection was conducted with X-tremeGENE™ HP DNA Transfection.

Stable knockdown: SQLE-knockdown SKOV3 cells were established by lentiviral transduction (shSQLE vs. LV3-NC control) followed by selection with 2.0 μg/mL puromycin for 7 days.

Cell hypoxic model: cells were cultured in a Bugbox M hypoxic workstation at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 1% O2, 5% CO2.

Animal model

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University (Approval No. XJTU1AF2024LSYY-191) in compliance with NIH Guidelines. Female BALB/c nude mice (5 weeks old) were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at 24±1°C with 12/12-hour light/dark cycles, and provided irradiated feed and autoclaved water ad libitum.

Method details

Cell culture

The human ovarian cancer cell line SKOV3 was obtained from the Shanghai Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China), and the 3AO cell line was obtained from the Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (Jinan, China). The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL, 31800-014; Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. For hypoxic assays, cells were cultured in a Bugbox M hypoxic workstation (Ruskinn; Britain) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 1% O2, 5% CO2 for 24 h for RNA extraction or for 48 h for protein preparation. SKOV3 and 3AO cells were treated with 80 or 160 μg/mL of 20(S)-Rg3 (Tasly Pharmaceutical Company, PCM-YMC-017; Tianjin, China) for 24 h to extract total RNA or 48 h to extract total protein.

mRNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Total RNAs was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA). The Ion Total RNA-Seq Kit v2.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.; 4479789, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to prepare the complementary DNA libraries. Single-end sequencing was performed using the Ion Torrent Proton platform from Novel Bioinformatics Ltd. Co. The mRNA deep-sequencing data were filtered to obtain clean data. The mRNA counts were calculated using a BAM file. The differentially expressed mRNAs were filtered using an empirical bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments34 (EB-Seq) algorithm after significant analysis and false discovery rate (FDR) analysis according to the following criteria: (1) fold change >2 or <0.5, (2) p-value < 0.05, and (3) FDR < 0.05. Gene ontology (GO) analysis was used to categorize the biological implications of differentially expressed mRNAs. KEGG pathway analysis was performed to identify the main biochemical and signaling pathways associated with differentially expressed mRNAs.

Targeted lipidomics analysis

20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 cells and the negative control cells were digested with trypsin and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. Cell precipitates were gently washed with pre-cooled PBS, centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 1,000 rpm, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for 3 min, and sent to Metware Biotechnology (Wuhan, China) for targeted lipidomics using a liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system (SCIEX; Framingham, MA, USA). The mass spectrometry conditions primarily include: Electrospray ionization (ESI) at a temperature of 500°C, with a mass spectrometry voltage of 5,500 V in positive ion mode and −4,500 V in negative ion mode. Ion source gas 1 (GS1) was set to 45 psi, gas 2 (GS2) to 55 psi, and curtain gas (CUR) to 35 psi. The collision-activated dissociation (CAD) parameters were set to Medium.

The raw data were used for quality control analysis, principal component analysis (PCA), and clustering analysis. Differential Metabolite Selection Criteria: (1) Metabolites with a fold change (FC) ≥ 2 or ≤0.5 were selected. (2) If biological replicates are present within the sample groups, metabolites with a Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) value ≥1 were selected in addition to the above criteria. Significantly enriched pathways were identified using a hypergeometric test’ p-value.

Integrative analysis of transcriptomics and targeted lipidomics

PCA was performed to visualize the differences in the transcriptome and metabolome between 20(S)-Rg3-treated SKOV3 cells and negative control cells. Metabolites (VIP ≥1, FC ≥ 2 or ≤0.5, and p < 0.05) were considered as potential biomarkers. To understand the relationship between genes and metabolites, pathway and correlation analyses were performed, including KEGG, differential correlation, and canonical correlation analyses (CCA). The OPLS model was established by selecting all the differentially expressed genes and metabolites. The variables with higher correlation and weight in different data were determined using the load diagram, and important variables that affected another group of studies were screened. Regulatory networks of differential genes and differential metabolites were constructed using Cytohubba and Metscape, which were Cytoscape plugins for visualizing and interpreting metabolomic data in the context of human metabolic networks, to track the connections between metabolites and genes, and visualize compound networks.

siRNA and plasmid transfection

SKOV3 and 3AO cells were seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 h prior to transfection with siRNAs targeting SQLE, FDFT1 (Ribo-Bio Co. Ltd.; Guangzhou, China), HIF-1α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-35561; Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or negative control siRNA using X-treme GENE transfection reagent (Roche, 04476093001; Indianapolis, IN, USA), with all procedures performed according to the manufacturer’s optimized protocol. The siRNA sequences used were as follows: siSQLE-1: GCACCACAGTTTAAAGCAA; siSQLE-2: GAAAGAACCATTCTTAGAA; siSQLE-3: CACGGAAGATTCATCATGA; siFDFT1-1: GCAGAATCTTCCCAAC TGT; siFDFT1-2: GTGCCTGAATGAACTTATA. The HIF-1α-expressing plasmid and the empty vector were transfected into cells using X-treme GENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche; Indianapolis, 06366236001; Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 h of transfection, cells were treated with 20(S)-Rg3 (80 μg/mL for SKOV3 and 160 μg/mL for 3AO) for 24 h (for RNA extraction) or 48 h (for protein extraction).

Extraction of total RNA and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596018; Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, RR047A; Dalian, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was then used as a template for qPCR with TB Green Premix Ex Taq II kit (Takara, RR820; Dalian, China) on a CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA). The primer sequences of the SQLE gene were as follows: 5′-CAGATAATCTCCGCCTTGACC-3′(forward); 5′-AAAGTGATGAAGTCCCCGA AC-3′(reverse). Primer sequences for FDFT1, HIF-1α, and β-actin have been reported in the literature.19,33,35 β-actin was used as an internal reference gene.

Western blot

Total protein samples were extracted from cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, P0013B; Shanghai, China) and quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) protein assay kit (CW Biotech, CW0014; Taizhou, China). Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed. The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Pall Life Science, P-N66485; Port Washington, NY, USA). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against SQLE (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-271651; Santa Cruz, CA, USA), FDFT1 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 13128-1-AP; Wuhan, China), HIF-1α (1:1,000, Abcam, H1alpha67; Cambridge, MA, USA), and β-actin (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, 3700; Danvers, MA, USA) after blocking with 5% non-fat milk, followed by five times of 8 min TBST washes and subsequent 1 h incubation at 25°C with horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 7076/7074, Danvers, MA, USA) Chemiluminescent signals were observed using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Tanon; Shanghai, China).

5-Ethynyl-2′- deoxyuridine (EdU) assay

SKOV3 and 3AO cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 3000 cells per well and cultured for 24 h. Transfection experiments were then performed. 20(S)-Rg3 was added after 24 h of transfection. EdU assays were conducted after 24 h of 20(S)-Rg3 treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Ribo-Bio, R11053.9; Guangzhou, China).

Colony formation assay

After 48 h of siRNA transfection, the cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 600 cells/well and cultured for 10 days. The colonies were fixed with methanol for 30 min and washed with PBS. Colonies were visualized by staining with 1% crystal violet and washing with running water. The numbers of colonies containing more than 50 cells was counted under a microscope.

In vitro migration and invasion assays

After 48 h of siRNA transfection, 1×105 cells in 100 μL of serum-free 1,640 medium were re-inoculated into the upper Millicell chambers (Millipore, PTEP24H48; Bedford, MA, USA) and cultured for 24 h for the in vitro migration assay. 2 × 105 cells were inoculated into the upper Millicells that had been pre-layered with Matrigel (Corning, 356234; Bedford, MA, USA) for 48 h for the in vitro invasion assay. Five hundred microliters of 1,640 medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum were added to the bottom layer of the chambers as a chemoattractant. After 24 h or 48 h of culture, the cells in the upper chambers were cleared with swabs. The cells were fixed with methyl alcohol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature. The number of migrated and invaded cells was counted under an inverted microscope (original magnification, 200×).

Cellular immunofluorescence assay

SKOV3 and 3AO cells were inoculated in 24-well plates for 24 h and, then treated with 20(S)-Rg3 for 48 h. The cells were then washed, fixed, and perforated with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Serum was used to block non-specific binding sites of intracellular proteins for 1 h at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies, including SQLE (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-271651; Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or FDFT1 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 13128-1-AP; Wuhan, China) at 4°C. The cells were then incubated with secondary antibodies, including goat anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor 647), goat anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor 488), and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor 488) (1:300, Abcam Inc., ab150115, ab150113 and ab150077; Cambridge, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI for 3–5 min, mounted, and photographed using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Detection of intracellular free cholesterol and cholesteryl esters

Cells were washed twice with PBS, trypsinized, suspended, and counted. The cells were resuspended in reaction buffer and seeded into light-proof 96-well plates (10,000 cells per well, three replicates per sample). Intracellular free cholesterol and cholesteryl esters were examined according to the Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit instructions (Invitrogen, A12216; Carlsbad, CA, USA) on a fluorescence microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.; Winooski, VT, USA) with excitation in the range 530–560 nm and emission detection at ∼590 nm.

Co-immunoprecipitation(Co-IP)

SKOV3 and 3AO cells were inoculated into 10 cm dishes. When the cell density reached 90%, the cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. The lysate was centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C, 12,000 rpm, and the supernatant was aspirated. The supernatant was divided into the IgG, input, and anti-FDFT1-IP groups. The IgG antibody (1:1,000) and FDFT1 antibody (1:1,000, Ab195046, Abcam; Cambridge, MA, USA) were added to the IgG and IP protein suspensions, respectively. The protein mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C in a shaker. The IgG and anti-FDFT1-IP protein mixtures were then added to pre-washed protein A/G magnetic beads (Millipore, LSKMAGAG02; Bedford, MA, USA) and shaken at 4°C for 4 h. The immunoprecipitation mixture was washed to 3–5 times, resuspended in 50 μL of 1 × SDS spiking buffer, and boiled for 10 min. IgG and IP samples were separated transiently using a magnetic holder. The supernatant was carefully aspirated for Western blotting analysis.

Establishment of a stable SQLE knock-down ovarian cancer cell line

The shSQLE-expressing lentivirus and its LV3-negative control virus (GenePharma, SH750; Shanghai, China) were infected into SKOV3 cells in 24-well plates according to the manuscript’s instruction. The medium was changed to RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum after 24 h of infection. Puromycin (0.5 μg/mL) was added to the medium after 72 h of infection. SQLE gene expression was determined by qPCR and Western blot.

Subcutaneous xenograft model in nude mice

Six 5-week-old female nude mice were randomly divided into two groups (shSQLE group vs. negative control group). 2 × 106 cells in 100 μL of PBS was subcutaneously inoculated into the axillary side of the right forelimb of the nude mice. Nude mice were closely monitored for changes in body weight and subcutaneous tumor volume. The longest diameter (L) and shortest diameter (W) of the xenografts were measured every other day, and the tumor volumes were calculated using the formula V = 0.5236 × L × W2. After 23 days of inoculation, the nude mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxia, photographed, and the tumor tissues were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Animal models and treatment

Fifteen 5-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were randomly allocated into three experimental groups (n = 5/group). LV3-NC ovarian cancer cells (2 × 106 cells in 100 μL PBS) were subcutaneously inoculated into the right axillary region adjacent to the dorsal midline of control groups and 20(S)-Rg3 treatment group, while shSQLE+20(S)-Rg3 group received shSQLE-transfected cells. When tumor volumes exceeded 10 mm3 (calculated as V = 0.5236 × L × W2), therapeutic intervention was initiated: 20(S)-Rg3 groups and shSQLE+20(S)-Rg3 group received intratumoral multipoint injections of 20(S)-Rg3 (5 mg/kg in PBS) every 48 h for 25 consecutive days, whereas control group received equivalent PBS volumes. Body weight, feeding behavior, and neurological status were monitored throughout the study period. After 25-day treatment, mice were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation. Resected tumor tissues underwent either 4% paraformaldehyde fixation for histopathological analysis or snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen for subsequent protein extraction. All procedures complied with institutional animal care guidelines (Ethics Approval No.: XJTU1AF2024LSYY-191).

H&E staining and immunohistochemical staining

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h, the subcutaneous xenograft tissues from nude mice were washed, dehydrated, cleared, immersed in paraffin, embedded in liquid paraffin and stored at 4°C. Using a paraffin slicer (Leica; Wetzlar, Germany), the paraffin-embedded tissues were sliced into sections with a thickness of 4 μm. The sections were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through decreasing concentrations of ethanol, and washed in PBS, followed by being stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol and xylene, mounted and observed with a microscope. Another set of sections, after dewaxing, rehydrating, antigen retrieving, blocking and overnight incubating with SQLE primary antibody (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-271651; Santa Cruz, CA, USA), were subjected to immunohistochemistry staining following the steps of the SP Histochemistry Kit (ZSGB-BIO, SP-9000; Beijing, China).

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0) or ImageJ or Microsoft Excel (2019). The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from at least three independent experiments. Under the condition of passing the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, the unpaired t-tests (for two groups) or one-way ANOVA (for three or more groups) were used for statistical analysis. For non-normal and heterogeneous variance data, non-parametric test methods such as the Kruskal-Wallis H test or Friedman test were used. Statistical significance was defined as follows: ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Published: July 1, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112853.

Contributor Information

Le Zhao, Email: zhaole2@mail.xjtu.edu.cn.

Xu Li, Email: lixu56@mail.xjtu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Chen J., Hong J.H., Huang Y., Liu S., Yin J., Deng P., Sun Y., Yu Z., Zeng X., Xiao R., et al. EZH2 mediated metabolic rewiring promotes tumor growth independently of histone methyltransferase activity in ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2023;22:85. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y., Liu L., Xia L., Wu N., Wang Y., Li H., Chen X., Zhang X., Liu Z., Zhu M., et al. TRPM7 silencing modulates glucose metabolic reprogramming to inhibit the growth of ovarian cancer by enhancing AMPK activation to promote HIF-1α degradation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022;41:44. doi: 10.1186/s13046-022-02252-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xuan Y., Wang H., Yung M.M., Chen F., Chan W.S., Chan Y.S., Tsui S.K., Ngan H.Y., Chan K.K., Chan D.W. SCD1/FADS2 fatty acid desaturases equipoise lipid metabolic activity and redox-driven ferroptosis in ascites-derived ovarian cancer cells. Theranostics. 2022;12:3534–3552. doi: 10.7150/thno.70194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y., Wang Y., Zhao G., Orsulic S., Matei D. Metabolic dependencies and targets in ovarian cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023;245 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W., Yao P., Vong C.T., Li X., Chen Z., Xiao J., Wang S., Wang Y. Ginseng: A bibliometric analysis of 40-year journey of global clinical trials. J. Adv. Res. 2021;34:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan W., Fan L., Wang Z., Mei Y., Liu L., Li L., Yang L., Wang Z. Rare ginsenosides: a unique perspective of ginseng research. J. Adv. Res. 2024;66:303–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2024.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan L., Qian C., Yang C., Peng S., Dong G., Cheng P., Zong G., Han H., Shao M., Gong G., et al. Ginseng polysaccharides ameliorate ulcerative colitis via regulating gut microbiota and tryptophan metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;265 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li F., Cai C., Wang F., Zhang N., Zhao Q., Chen Y., Cui X., Wang S., Zhang W., Liu D., et al. 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg3 suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting E2F-DP dimerization. Phytomedicine. 2025;141 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia J., Zhang S., Zhang R., Wang A., Zhu Y., Dong M., Ma S., Hong C., Liu S., Wang D., Wang J. Targeting therapy and tumor microenvironment remodeling of triple-negative breast cancer by ginsenoside Rg3 based liposomes. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:414. doi: 10.1186/s12951-022-01623-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang R., Li L., Li H., Bai H., Suo Y., Cui J., Wang Y. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 reduces KIF20A expression and promotes CDC25A proteasomal degradation in epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Ginseng Res. 2024;48:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2023.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng X., Zhou Y., Chen W., Chen L., Lu J., He F., Li X., Zhao L. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 prevents PKM2-targeting miR-324-5p from H19 sponging to antagonize the warburg effect in ovarian cancer cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;51:1340–1353. doi: 10.1159/000495552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y., Zheng X., Lu J., Chen W., Li X., Zhao L. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 inhibits the warburg effect via modulating DNMT3A/MiR-532-3p/HK2 pathway in ovarian cancer cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;45:2548–2559. doi: 10.1159/000488273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo Z.W., Sun Y.Y., Xia W., Xu J.Y., Xie D.J., Jiao C.M., Dong J.Z., Chen H., Wan R.W., Chen S.Y., et al. Physical exercise reverses immuno-cold tumor microenvironment via inhibiting SQLE in non-small cell lung cancer. Mil. Med. Res. 2023;10:39. doi: 10.1186/s40779-023-00474-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He L., Li H., Pan C., Hua Y., Peng J., Zhou Z., Zhao Y., Lin M. Squalene epoxidase promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation through accumulating calcitriol and activating CYP24A1-mediated MAPK signaling. Cancer Commun. 2021;41:726–746. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan J., Liu R., Lu W., Peng H., Yang J., Zhang Q., Yu T., Huo B., Wei X., Liang H., et al. SQLE-catalyzed squalene metabolism promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and tumor development in K-ras-driven cancer. Cancer Lett. 2025;616 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jun S.Y., Brown A.J., Chua N.K., Yoon J.Y., Lee J.J., Yang J.O., Jang I., Jeon S.J., Choi T.I., Kim C.H., Kim N.S. Reduction of squalene epoxidase by cholesterol accumulation accelerates colorectal cancer progression and metastasis. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1194–1207.e28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang Z., Li C., Kang B., Gao G., Li C., Zhang Z. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu J., Chen H., He F., You Y., Feng Z., Chen W., Li X., Zhao L. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 upregulates HIF-1alpha-targeting miR-519a-5p to inhibit the Warburg effect in ovarian cancer cells. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020;47:1455–1463. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu J., Zhou Y., Zheng X., Chen L., Tuo X., Chen H., Xue M., Chen Q., Chen W., Li X., Zhao L. 20(S)-Rg3 upregulates FDFT1 via reducing miR-4425 to inhibit ovarian cancer progression. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020;693 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2020.108569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai D., Zhong G.C., Dai X., Zhao Z., Chen M., Hu J., Wu Z., Cheng L., Li S., Gong J. Targeting FDFT1 reduces cholesterol and bile acid production and delays hepatocellular carcinoma progression through the HNF4A/ALDOB/AKT1 axis. Adv. Sci. 2025;12:e2411719. doi: 10.1002/advs.202411719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagai M., Sakakibara J., Wakui K., Fukushima Y., Igarashi S., Tsuji S., Arakawa M., Ono T. Localization of the squalene epoxidase gene (SQLE) to human chromosome region 8q24.1. Genomics. 1997;44:141–143. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laden B.P., Tang Y., Porter T.D. Cloning, heterologous expression, and enzymological characterization of human squalene monooxygenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;374:381–388. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan H., Huang X., Zhou Y., Mu Y., Zhang S., Cao Y., Wu W., Xu Z., Chen X., Zhang X., et al. Disturbing cholesterol/sphingolipid metabolism by squalene epoxidase arises crizotinib hepatotoxicity. Adv. Sci. 2025;12:e2414923. doi: 10.1002/advs.202414923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S., Dong L., Ma L., Yang S., Zheng Y., Zhang J., Wu C., Zhao Y., Hou Y., Li H., Wang T. SQLE facilitates the pancreatic cancer progression via the lncRNA-TTN-AS1/miR-133b/SQLE axis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2022;26:3636–3647. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang W., Xu F., Zhao M., Zhang S. Ferroptosis regulators, especially SQLE, play an important role in prognosis, progression and immune environment of breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08892-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xun S.G., Ma Z.H., Yu M.H., Ding J., Xue W., Qi J. Squalene epoxidase metabolic dependency is a targetable vulnerability in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2022;82:3032–3044. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-21-3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C., Wang Y., Liu D., Wong C.C., Coker O.O., Zhang X., Liu C., Zhou Y., Liu Y., Kang W., et al. Squalene epoxidase drives cancer cell proliferation and promotes gut dysbiosis to accelerate colorectal carcinogenesis. Gut. 2022;71:2253–2265. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vahabi M., Comandatore A., Franczak M.A., Smolenski R.T., Peters G.J., Morelli L., Giovannetti E. Role of exosomes in transferring chemoresistance through modulation of cancer glycolytic cell metabolism. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2023;73:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2023.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H., Feng Z., He M.L. Lipid metabolism alteration contributes to and maintains the properties of cancer stem cells. Theranostics. 2020;10:7053–7069. doi: 10.7150/thno.41388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corn K.C., Windham M.A., Rafat M. Lipids in the tumor microenvironment: From cancer progression to treatment. Prog. Lipid Res. 2020;80 doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2020.101055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krieg S., Fernandes S.I., Kolliopoulos C., Liu M., Fendt S.M. Metabolic signaling in cancer metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2024;14:934–952. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-24-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haider S., McIntyre A., van Stiphout R.G.P.M., Winchester L.M., Wigfield S., Harris A.L., Buffa F.M. Genomic alterations underlie a pan-cancer metabolic shift associated with tumour hypoxia. Genome Biol. 2016;17:140. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0999-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu T., Zhao L., Zhang Y., Chen W., Liu D., Hou H., Ding L., Li X. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 targets HIF-1alpha to block hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leng N., Dawson J.A., Thomson J.A., Ruotti V., Rissman A.I., Smits B.M.G., Haag J.D., Gould M.N., Stewart R.M., Kendziorski C. EBSeq: an empirical Bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1035–1043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu J., Wang L., Chen W., Wang Y., Zhen S., Chen H., Cheng J., Zhou Y., Li X., Zhao L. miR-603 targeted hexokinase-2 to inhibit the malignancy of ovarian cancer cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019;661:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Raw mRNA sequencing data reported in this study have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. It is publicly available. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

The data from this study are presented in the text and supplementary materials. The datasets will be made available to the lead contact upon reasonable request.