Abstract

Importance:

Dalbavancin is a long-acting intravenous lipoglycopeptide that may be effective for treatment of complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia without requiring long-term intravenous access.

Objective:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of dalbavancin versus standard therapy for completion of treatment of complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.

Design, Setting, Participants:

Open-label, assessor-masked, randomized clinical trial conducted from April 2021 to December 2023 at 23 medical centers in the US (n=22) and Canada (n=1). Follow-up: 70 days (180 days for participants with osteomyelitis); date of final follow-up: December 1, 2023. Hospitalized adults with complicated S. aureus bacteremia who achieved blood culture clearance following ≥72 hours but ≤10 days of initial antibacterial therapy. Participants were excluded if they had central nervous system infection, retained infected prosthetic material, left-sided endocarditis, or severe immune compromise.

Interventions:

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 2 doses of intravenous dalbavancin (n=100; 1500 mg on days 1 and 8) or 4–8 total weeks of standard intravenous therapy (n=100; cefazolin or anti-staphylococcal penicillin if methicillin-susceptible; vancomycin or daptomycin if methicillin-resistant).

Main outcomes and Measures:

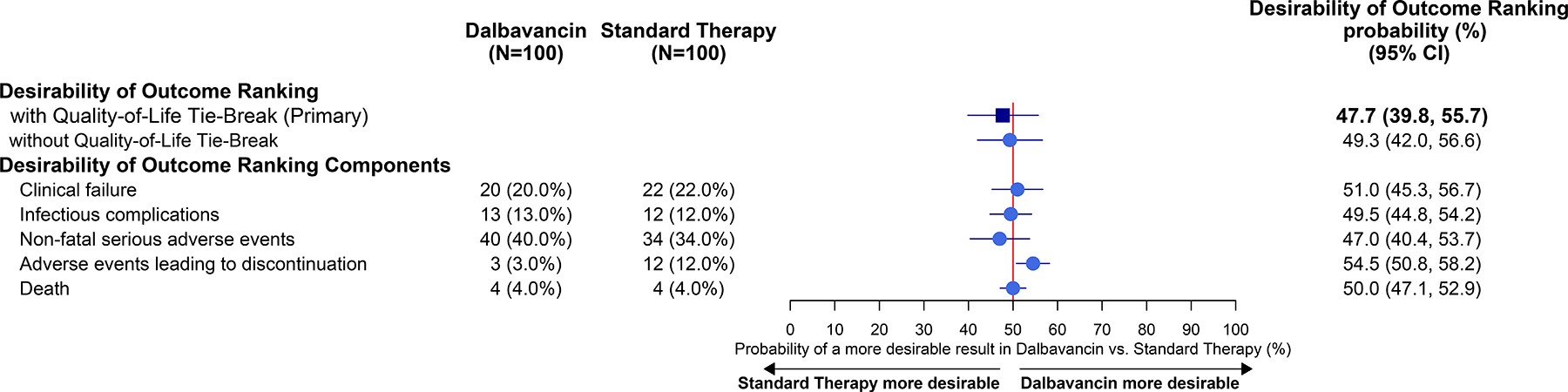

The primary outcome was the desirability of outcome ranking (DOOR) at day 70 which involved 5 components (clinical success, infectious complications, safety complications, mortality, and health-related quality of life) and was assessed for superiority (achieved if the 95% CI for the probability of dalbavancin having a superior DOOR was > 50%). Secondary outcomes included clinical efficacy at day 70 (pre-specified non-inferiority margin of 20%) and safety. Clinical outcomes were assessed by a review committee masked to treatment allocation.

Results:

Of 200 participants randomized (mean age, 56 [SD 16.2] years; 62 [31%] women), 167 (84%) survived to day 70 and had an efficacy assessment, and participants without a day 70 efficacy assessment were treated as clinical failures in the analyses. The probability of a more desirable day 70 outcome with dalbavancin versus standard therapy was 47.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 39.8 to 55.7%). Regarding secondary outcomes, clinical efficacy was documented in 73 of 100 for dalbavancin and 72 of 100 for standard therapy (difference: 1.0%, 95% CI: −11.5 to 13.5%), meeting the non-inferiority criterion. Serious adverse events were reported in 40 of 100 participants who received dalbavancin and 34 of 100 participants who received standard therapy; treatment-related adverse events were uncommon in both groups (8 of 100 with dalbavancin, 6 of 100 with standard therapy).

Conclusions and Relevance:

Among adult participants with complicated S. aureus bacteremia who achieved blood culture clearance, dalbavancin was not superior to standard therapy by desirability of outcome ranking. When considered with other efficacy and safety outcomes these findings may help inform use of dalbavancin in clinical practice.

Trial registration:

Clinical Trials.gov identifier: NCT04775953.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is the leading bacterial cause of death due to bloodstream infection worldwide,1 and randomized clinical trials informing the management of S. aureus bacteremia are limited.2–4 Treatment generally requires prolonged administration of intravenous antibiotics, which can be associated with complications such as catheter-associated thrombosis or secondary infection.5,6

Dalbavancin is an appealing treatment option given its long terminal half-life of 14 days and potent in vitro activity against S. aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]).7 Pharmacokinetic modeling predicts that 2 weekly 1500 mg infusions provide plasma drug levels well above S. aureus’ minimum inhibitory concentration for over 6 weeks.8 The 55 participants enrolled in previous randomized trials assessing dalbavancin for other indications who were subsequently found to have S. aureus bacteremia achieved microbiologic success.9–13 Several case series of dalbavancin for endocarditis and bacteremia have also reported high clinical success rates.14–17 However, failures of dalbavancin therapy for complicated S. aureus infections have also been reported, highlighting the need for high-quality data to guide clinicians.18–20 Here, we report the results of a randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of dalbavancin among hospitalized participants with complicated S. aureus bacteremia or right-sided endocarditis. To reflect anticipated real-world use, participants were randomized after they had achieved blood culture clearance on initial therapy (e.g., dalbavancin was compared with standard therapy during the consolidation phase of treatment).

METHODS

Trial Design and Oversight

Dalbavancin as an Option for Treatment of S. aureus Bacteremia (DOTS) was an open-label, assessor-masked, randomized, superiority trial conducted at 23 medical centers in the US and Canada from April 2021 to December 2023 (Supplement). A central institutional review board approved the protocol, with assent from each participating center’s local institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was published in advance.21 An independent data and safety monitoring board supervised the trial. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines were followed.22

Participants

Hospitalized adults (≥18 years of age) with complicated S. aureus bacteremia were eligible if they achieved blood culture clearance and resolution of fever. Participants received 72 hours but no more than 10 days of initial antibacterial therapy prior to randomization. For study purposes, complicated bacteremia was defined as any case not meeting criteria for uncomplicated bacteremia per 2011 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines (Supplement). These guidelines defined uncomplicated bacteremia as infections in which endocarditis had been excluded, there are no implanted prostheses, follow-up blood cultures 2 to 4 days after initial blood cultures do not grow S. aureus, defervescence has occurred within 72 hours of initiating effective therapy, and there is no evidence of metastatic sites of infection.23 Race and ethnicity of participants were self-reported according to multiple prefixed categories and were included to adequately describe the study population.

Exclusion criteria included: 1) infectious central nervous system involvement; 2) known or suspected left-sided endocarditis or perivalvular abscess; 3) planned right-sided valve replacement surgery; 4) presence of a prosthetic heart valve, cardiac device, or intravascular graft unless removal was planned; 5) presence of infected prosthetic joint or other infected extravascular hardware unless removal was planned; 6) polymicrobial bacteremia; 7) significant hepatic insufficiency; 8) severe immunosuppression; 9) known hypersensitivity to dalbavancin; 10) receipt of dalbavancin or oritavancin in the preceding 60 days; 11) pregnant or nursing females; or 12) infections in which S. aureus is not susceptible to dalbavancin. Dalbavancin susceptibility was inferred from vancomycin susceptibility.24,25 Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the previously published protocol and Supplement.21

Trial Groups and Randomization

Eligible participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either dalbavancin 1500 mg intravenously on day 1 and day 8 from randomization (with dose adjustment to 1125 mg for participants with creatinine clearance <30 mL/minute and not receiving dialysis) or standard therapy. Standard therapy was restricted to a single agent – cefazolin or an anti-Staphylococcal penicillin for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and vancomycin or daptomycin for MRSA. Exceptions were permitted for medication allergy or other contraindication. Standard therapy agents were dosed according to local practice of each site. Treatment duration in the standard therapy group was left to the discretion of the treating clinician, but limited to ≥4 and ≤8 weeks total.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was desirability of outcome ranking (DOOR) at day 70 post randomization, assessed by an independent committee of 4 infectious diseases experts who were masked to treatment assignment. The DOOR endpoint was selected because it better reflects clinical decision-making: in contrast to binary efficacy outcomes, DOOR explicitly integrates efficacy, safety, and quality of life to inform the optimal treatment for a patient. The DOOR endpoint was specifically developed and validated for bacteremia and consisted of 5 components: clinical success (defined as survival with resolution of signs and symptoms of S. aureus bacteremia), infectious complications (development of new sites of infection, relapse of bacteremia, or requirement for additional unplanned source control procedures), safety complications (serious adverse events or adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation), mortality, and health-related quality of life.26–28 Note that clinical success is a summary assessment at time of follow-up visit whereas infectious complications are cumulative events that occur throughout study participation. Thus, it is possible for a patient to achieve clinical success in the end despite experiencing infectious complications along the way. The highest DOOR rank included participants who experienced treatment success without infectious or safety complications, whereas the lowest rank included participants who died. Intermediate ranks included participants who survived but with treatment failure or complications (Supplement).27 The day 70 follow-up interval was selected because most participants were anticipated to complete treatment by day 42 and the majority of S. aureus bacteremia relapses occur within 30 days of treatment completion.29

Health-related quality of life was assessed at each visit using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) physical function short form, a subset of a survey derived from PROMIS which has been specifically evaluated for tracking patient-centered outcomes in S. aureus bacteremia (Supplement).26,28 For surviving participants with identical DOOR, change in health-related quality of life from baseline to day 70 served as a tie-breaker.27

Secondary outcomes included clinical efficacy (defined as a composite of the lack of clinical failure, infectious complications, or mortality) and safety (incidence of serious adverse events or adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation). For safety purposes, acute kidney injury was defined as an increase in creatinine to 1.5 times the upper limit of normal or 1.5 times the baseline creatinine. Exploratory outcomes included microbiologic success (defined as no post-randomization growth of the baseline pathogen from blood cultures or other usually sterile body sites), additional safety measures (adverse events categorized by type, severity, and relationship to treatment), and osteomyelitis recurrence by day 180 among participants with osteomyelitis at randomization. The prolonged follow-up interval for participants with osteomyelitis was selected because relapsed infection commonly presents several months after the end of treatment.30,31

Statistical Analysis

Primary and secondary clinical efficacy outcomes were assessed as randomized. The safety analysis was conducted in the safety population, defined as any participants receiving at least 1 dose of study-directed antibiotics post-randomization and allocated according to treatment received. Clinical efficacy was adjudicated by the same treatment-blinded independent review committee as the primary outcome. If the adjudication committee lacked sufficient data to determine clinical efficacy (a component of both DOOR and clinical efficacy outcomes), the patient’s missing outcome was classified as a clinical failure.

The study was powered to evaluate for superiority by DOOR. Assuming a 65% probability that the dalbavancin group would have a superior DOOR while accounting for up to 12% loss to follow-up, we calculated that 200 participants would need to be enrolled to achieve 90% power with a one-sided alpha of 0.025. Similar power was estimated for the secondary clinical efficacy outcome (87–94%) with a one-sided alpha of 0.025 and a pre-specified 20% non-inferiority margin (Supplement).

For the primary outcome, the DOOR probability was estimated using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U statistic with the corresponding 95% confidence interval calculated using Halperin’s method.32 Superiority of dalbavancin could be concluded if the 95% CI for the probability of dalbavancin having a superior DOOR was > 50%. For the secondary clinical efficacy outcome, difference in clinical efficacy (dalbavancin group minus standard therapy group) was determined and a two-sided 95% confidence interval for the difference calculated using linear regression. The non-inferiority test for clinical efficacy was based on the lower bound of the confidence interval being within a prespecified non-inferiority margin of 20% and the upper bound containing 0%. The selected 20% non-inferiority margin aligns with the margin used in other contemporary infection trials,4,33 and also reflects the trade-off in efficacy clinicians and participants might be willing to accept given dalbavancin’s hypothesized advantages over prolonged intravenous therapies. For example, survey data indicates that many clinicians would consider a 20% margin acceptable if the alternative treatment provided some beneficial trade-off,34 such as shorter duration or improved safety. Moreover, dalbavancin avoids the estimated 18–22% complication risk associated with prolonged intravenous access.5,6

No formal hypothesis testing was conducted for exploratory outcomes, subgroup analyses, or other analysis populations. For subgroup analyses, only point estimates with 95% CIs were reported. Widths of the subgroup analyses’ confidence intervals were not adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used to infer definitive treatment effects.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Between April 2021 and December 2023, 200 participants were enrolled from 23 sites in the US and Canada (Figure 1, eTable 1); 100 were randomly assigned to dalbavancin and 100 to standard therapy. All participants received at least 1 study drug dose. In the dalbavancin group, 4 participants did not receive the second dose due to death (n=2), adverse event (n=1), or loss to follow-up (n=1). See eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement for summary of antibiotic selection and duration for participants receiving standard therapy. See eTable 4 in Supplement for source control procedures.

Figure 1:

Recruitment, Randomization and Patient Flow in the DOTS Trial

Baseline characteristics and infection features were generally balanced, although bacteremia durations >4 days and chronic kidney disease were numerically more common in the standard therapy group while immunosuppression and soft tissue infections were numerically more common in the dalbavancin group (Table 1). Overall, common comorbidities among participants with S. aureus bacteremia were well represented in the trial population, including 15.0% of participants with injection drug use and 8.0% with implanted prosthetic materials. Reflecting current epidemiology in the US, 67.0% of isolates were methicillin-susceptible and 33.0% were methicillin-resistant.35

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Participants in the DOTS Trial

| Characteristic | Dalbavancin (N=100) |

Standard Therapy (N=100) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 56 (41–66) | 56 (41–68) |

| Age ≥80 years, No. (%) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 70 (70) | 68 (68) |

| Female | 30 (30) | 32 (32) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 68 (68) | 69 (69) |

| Black or African-American | 20 (20) | 29 (29) |

| Asian | 5 (5) | 1 (1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Not reported | 5 (5) | 1 (1) |

| Hispanic or Latino, No. (%) | 11 (11) | 14 (14) |

| Body mass indexa, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 27.6 (24.3–31.7) | 26.9 (23.3–33.5) |

| Persons who inject drugs, No. (%) | 16 (16) | 13 (13) |

| Medical comorbidities, No. (%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (44) | 48 (48) |

| Immunosuppressed conditionb | 35 (35) | 26 (26) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 20 (20) | 30 (30) |

| Heart failure | 21 (21) | 19 (19) |

| Cancer | 21 (21) | 17 (17) |

| Receiving dialysis | 12 (12) | 13 (13) |

| Liver disease | 14 (14) | 8 (8) |

| Participants who had implanted prosthetic materials, No. (%) | 12 (12) | 4 (4) |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, No. (%) | 34 (34) | 32 (32) |

| Anatomic Site of Infectionc, No. (%) | ||

| Soft tissue infection | 40 (40) | 30 (30) |

| Osteomyelitis, non-vertebral | 17 (17) | 19 (19) |

| Septic arthritis | 12 (12) | 14 (14) |

| Septic thrombophlebitis | 10 (10) | 14 (14) |

| Pneumonia / empyema | 11 (11) | 5 (5) |

| Septic pulmonary emboli | 8 (8) | 7 (7) |

| Right-sided endocarditis | 6 (6) | 4 (4) |

| Vascular graft infection/mycotic aneurysm | 4 (4) | 6 (6) |

| Vertebral osteomyelitis | 5 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Cardiac device infection | 4 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Prosthetic joint infection | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Visceral abscess | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Deep-seated infectiond, No. (%) | 54 (54) | 51 (51) |

| Days of bacteremia, No. (%) | ||

| <2 | 77 (77) | 64 (64) |

| 2–4 | 21 (21) | 26 (26) |

| >4 | 2 (2) | 10 (10) |

| Transthoracic echocardiography performed, No. (%) | 73 (73) | 71 (71) |

| Transesophageal echocardiography performed, No. (%) | 27 (27) | 29 (29) |

| Duration of pre-randomization therapy, median (IQR), days | 8 (6–9) | 7 (6–9) |

| Participants who underwent source control interventions, No. (%) | ||

| Surgical debridement | 27 (27) | 23 (23) |

| Central venous catheter removal | 9 (9) | 14 (14) |

| Amputation | 1 (1) | 8 (8) |

| Percutaneous drainage | 4 (4) | 4 (4) |

| Cardiac device removal | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Other device removale | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Vascular graft excision | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Cardiac valve surgery | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Percutaneous mechanical aspiration | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Osteomyelitisf | 22 (22) | 20 (20) |

| Underwent surgical debridementg | 8 (36) | 8 (40) |

Denominators are the number of randomized participants, unless specified otherwise.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Severe immunosuppression was excluded from the trial (see Supplement for detailed exclusion criteria). Here, immunosuppressed refers to participants with human immunodeficiency virus and a CD4+ cell count of >50 to ≤200, history of transplant >3 months prior and not receiving augmented immune suppression for treatment of rejection, participants receiving steroids equivalent to prednisone 40 mg daily or greater, participants receiving immune suppressive medications for rheumatologic conditions, and participants receiving chemotherapy but without sustained neutropenia below an absolute neutrophil count of 100 cells/mm3

Anatomic sites of infection may sum to greater than the number of participants in each arm as participants could have more than 1 anatomic site of infection.

Defined as the presence of at least 1 of the following anatomic sites of infection: endocarditis, osteoarticular infection, cardiac device infection, septic thrombophlebitis, or deep (non-cutaneous) abscess (e.g., psoas abscess, splenic abscess).

Including 1 peritoneal dialysis catheter, 1 external fixation device, and 1 percutaneous nephrostomy tube.

Including participants with osteomyelitis (vertebral or non-vertebral) at baseline.

Denominators are the number of participants who had osteomyelitis at baseline.

Among the 200 participants in the intention to treat population, the distribution of infection categories was similar between groups; S. aureus bacteremia was related to soft tissue infection in 70 (35.0%), osteoarticular infection (including osteomyelitis, septic arthritis and prosthetic joint infection) in 55 (27.5%), endovascular infection (including septic thrombophlebitis, right-sided endocarditis, cardiac device infection, and vascular graft infection or mycotic aneurysm) in 45 (22.5%), or pulmonary infection (including pneumonia, septic pulmonary emboli, and empyema) in 29 (14.5%). Ten participants had known right-sided endocarditis (6 in dalbavancin group, 4 in standard therapy). Median hospital length of stay was 3 days (IQR 2–7) in the dalbavancin group and 4 days (IQR 2–8) in the standard therapy group.

Primary Outcome

The probability that a patient randomly selected from the dalbavancin group would have a superior DOOR versus standard therapy group was 47.7% (95% CI: 39.8–55.7%; Figure 2), which did not demonstrate superiority of dalbavancin treatment. Individual DOOR components were similar between dalbavancin and standard therapy, though adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation were more common with standard therapy compared with dalbavancin (12.0% vs 3.0%; Figure 2A, 2B; details in Supplement eTables 5, 6, 7, 8 and eFigure 1). To address the issue that dalbavancin cannot be discontinued after receipt of the second dose, a post-hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted that excluded treatment discontinuation as a DOOR component, with no significant change in overall outcome (Supplement eTable 9).

Figure 2:

Primary Outcome (As Randomized Population)

A: Desirability of Outcome Ranking and Components by Treatment Group

B: Table of Desirability of Outcome Rankings with Components

C: Distribution of Desirability of Outcome Ranking by Treatment Group

Desirability of Outcome Ranking with Quality-of-Life (QoL) tie-break represents the DOOR probability that a participant in the dalbavancin group will experience a more favorable outcome compared to a participant in the standard therapy group. In cases where 2 participants achieve the same DOOR, change in QoL is used as a tie-breaker to provide a more nuanced distinction between them, except when both participants have died. The probability was estimated using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney statistic, with the corresponding 95% CI (confidence interval) calculated using the Halperin et al. (1989)’s method.23 If the 95% CI for the probability excluded the point of 50%, the difference in the DOOR endpoint between groups was regarded as significant. The individual components of the DOOR—clinical failure, non-fatal serious adverse events, adverse events leading to discontinuation, and QoL—were analyzed in the same manner as the DOOR. For clinical failure, non-fatal serious adverse events, and adverse events leading to discontinuation, the number of events and the proportion by group were presented. The adjudication committee did not have sufficient evidence to determine clinical failure for 11 participants in the dalbavancin group and 14 participants in standard therapy group were, therefore these participants were treated as having clinical failure. Rank 1: Alive with no events; Rank 2: Alive with 1 event; Rank 3: Alive with 2 events; Rank 4: Alive with 3 events. Details of adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation and clinical failures can be found in eTables 7 and 8.

Baseline and day 70 quality of life measures were similar between dalbavancin and standard therapy (Supplement eTable 10). Overall DOOR probability was similar whether or not change in health-related quality of life was used as a tie-breaker (Figure 2A).

Secondary Outcomes

A total of 73 of 100 participants in the dalbavancin group and 72 of 100 participants in the standard therapy group had overall clinical success (difference: +1.0%, 95% CI −11.5 to 13.5%; Table 2). The lower bound of the 95% confidence interval was within the prespecified margin of −20%, indicating that dalbavancin met criteria for non-inferiority relative to standard therapy.

Table 2:

Secondary and Exploratory Efficacy Analyses (As Randomized Population)

| Outcomes | Dalbavancin (N=100) |

Standard Therapy (N=100) |

Difference in Proportions (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| number (percent) | |||

| Secondary Outcome | |||

| Clinical Efficacy – Day 70 | 73 (73) | 72 (72) | 1.0 (-11.5, 13.5)a,b |

| Exploratory Outcomes | |||

| Microbiologic Success | |||

| Microbiologic success, Day 70 | 84/85 (99) | 79/82 (96) | 2.5 (-2.2, 7.3)c |

| Osteomyelitis Late Recurrence | |||

| Osteomyelitis – Day 180 recurrence | 3/15 (20) | 1/14 (7) | 12.9 (-15.7 to 40.3)d |

Clinical efficacy was defined as lack of clinical failure (lack of resolution in signs or symptoms of S. aureus bacteremia such that additional or ongoing antibiotic therapy was required), infectious complications, or mortality at day 70 assessment.

Clinical efficacy was compared using the difference in proportions, and the corresponding 95% CI (confidence interval) (CI) was calculated by assuming a normal distribution to approximate the distribution of the difference between the two-sample proportion. If the lower limit of the CI was larger than the noninferiority margin of −20%, it was considered that noninferiority of the dalbavancin group over the standard therapy group was established.

Microbiologic success was compared using difference in proportions and the corresponding 95% CI, which were estimated using the IPW (inverse probability weighting) approach to adjust for the missing microbiological outcomes. The weights were calculated using logistic regression, including age, sex, and treatment group as covariates.

For difference in osteomyelitis late recurrence proportions recurrence, and the corresponding 95% CI was calculated by the Miettinen–Nurminen method (Miettinen and Nurminen 1985).32

Exploratory Outcomes

Additional exploratory efficacy outcomes are presented in Table 2. Among evaluable participants, 84 of 85 (98.8%) achieved microbiologic success in the dalbavancin group as compared with 79 of 82 (96.3%) in the standard therapy group (difference: +2.5%, 95% CI: −2.2 to 7.3). Among participants with known osteomyelitis at the time of randomization, recurrence by day 180 occurred in 3 of 15 (20.0%) in the dalbavancin group compared with 1 of 14 (7.1%) in the standard therapy group (difference: 12.9%, 95% CI: −15.7 to 40.3).

Repeating the primary DOOR and secondary clinical efficacy analyses yielded similar outcomes within the clinically evaluable population (excluding those with missing data or major protocol deviations) as for all randomized participants (see eTables 11, 12, eFigure 2, eTable 13 in Supplement).

Safety Outcomes

Serious adverse events were common overall and similar between participants receiving dalbavancin (40 of 100) and standard therapy (34 of 100, Table 3). Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were numerically more frequent with standard therapy (12 of 100) than with dalbavancin (3 of 100; see eTable 7 in Supplement for summary; all adverse events occurring in >2% of participants are summarized in eTable 14 of Supplement). Nine total treatment-related adverse events were reported among 8 participants in the dalbavancin group; 6 participants receiving standard therapy experienced treatment-related adverse events. Among participants receiving dalbavancin, 4 (44.4%) were grade 1 and 5 (55.6%) were grade 3. Grade 1 adverse events consisted of transient rash or pruritus (2 of 4) or transient mild elevation in aspartate or alanine aminotransferases (2 of 4). Grade 3 adverse events attributed to dalbavancin included an infusion reaction (1 of 5 – consisting of transient fever, rigors, tachycardia), palmar rash (1 of 5), acute renal injury (1 of 5), and aspartate or alanine aminotransferase elevations (2 of 5 events, occurring within the same participant).

Table 3:

Adverse Events Occurring Through Day 70 Follow-up (Safety Population)

| Adverse Event | Dalbavancin (N=100) |

Standard Therapy (N=100) |

|---|---|---|

| number (percent) | ||

| Serious adverse events | 40 (40) | 34 (34) |

| Adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation | 3 (3) | 12 (12) |

| Grade 3 or higher Adverse Events | 51 (51) | 39 (39) |

| Adverse Events of Special Interestb | 12 (12) | 8 (8) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase elevation | 4 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Central line associated infection | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Acute kidney injury | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Rash/pruritus | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Catheter associated thrombosis | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| Infusion site infiltration | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Infusion reaction | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Generalized itching | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Hypotension | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Treatment Related Adverse Eventsb | 8 (8) | 6 (6) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase elevation | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Rash/pruritus | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Hemolytic anemia | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Infusion reaction | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Eosinophilic pneumonia | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Elevated blood creatine phosphokinase | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

One additional participant suffered hepatic failure approximately 4 weeks after dalbavancin receipt and improved following treatment for possible acetaminophen toxicity. Etiology of hepatic failure was attributed to polysubstance use by the data and safety monitoring group.

Treatment-emergent resistance occurred in 1 participant from each treatment group. Initial blood cultures from 1 patient with vertebral osteomyelitis randomized to dalbavancin showed vancomycin-susceptible MRSA. Swab cultures collected on day 41 from a non-healing spinal wound grew MRSA that was vancomycin intermediate and daptomycin non-susceptible (while specific dalbavancin susceptibilities were not performed, activity can be inferred from vancomycin).24 Initial blood cultures from 1 patient with osteomyelitis receiving daptomycin as standard therapy grew MRSA that was daptomycin-susceptible. Operative cultures collected during bone debridement on day 6 subsequently grew MRSA that was not susceptible to daptomycin.

Subgroup Analyses

Treatment effect was consistent for pre-specified analyses of DOOR, clinical efficacy, and microbiologic success across baseline pathogen (MSSA versus MRSA), all categories of infection (though there were very few pulmonary infections), by bacteremia duration, among persons who inject drugs, and participants that were immunosuppressed (DOOR and clinical efficacy in Figure 3; microbiologic success in Supplement eFigure 3).

Figure 3:

Subgroup Analyses (As Randomized Population)

A: Desirability of Outcome Ranking at Day 70

B: Clinical Efficacy at Day 70

A: The numbers display the number of participants by group in each subgroup. The 95% CIs (confidence interval) for the probability were calculated using the Halperin et al. (1989)’s method,23 except for pulmonary only subgroup. For the pulmonary-only subgroup, the pseudo-score approach based on Halperin et al. (1989) was used to calculate the CI, as the subgroup size was small and unbalanced between the groups. Other or unknown infections included 9 of unknown source, 5 deep muscle abscesses or myositis, 3 catheter/port related infections, 3 foot infections, 3 pyelonephritis or urosepsis or renal abscesses, 1 surgical site infection, 1 inoculation via drug injection, 1 arm infection without specified depth, 1 peritonitis, 1 arteriovenous fistula infection, 1 sacroiliac infection. Any subjects missing a day 70 clinical efficacy assessment were considered clinical failures.

B: The numbers display the number of clinical success and proportion by group in each subgroup. The 95% CIs for difference in proportions were calculated by assuming a normal distribution to approximate the distribution of the difference between the two-sample proportion. Other or unknown infections included 9 of unknown source, 5 deep muscle abscesses or myositis, 3 catheter/port related infections, 3 foot infections, 3 pyelonephritis or urosepsis or renal abscesses, 1 surgical site infection, 1 inoculation via drug injection, 1 arm infection without specified depth, 1 peritonitis, 1 arteriovenous fistula infection, 1 sacroiliac infection. Any subjects missing a day 70 clinical efficacy assessment were considered clinical failures.

DISCUSSION

In this assessor-masked trial enrolling participants with complicated S. aureus bacteremia, dalbavancin was not superior to standard therapy by DOOR. Dalbavancin met pre-specified criteria for non-inferiority by clinical efficacy, a secondary outcome. These findings remained consistent across all key subgroups – including anatomic site of infection, pathogen (MRSA or MSSA), immunosuppressed status, duration of bacteremia, and among persons who inject drugs. Dalbavancin was well-tolerated – consistent with its prior safety record in the treatment of soft tissue infections.9,10,36

While prior approvals of daptomycin4 and ceftobiprole3 have expanded treatment options for S. aureus bacteremia, all treatments currently approved with an indication for bacteremia require prolonged intravenous access. Switching from intravenous to oral therapy has proven successful in participants with bacterial endocarditis or osteomyelitis, but S. aureus (especially MRSA) are under-represented in existing trials with another large trial ongoing.37–39 Consequently, safe and effective treatment options are still needed. Dalbavancin is increasingly used for the management of S. aureus bacteremia – particularly in situations where clinicians or participants want to avoid prolonged intravenous access. Published observational data suggest high rates of clinical success with dalbavancin.14–17

We hypothesized that dalbavancin might prove superior to standard therapy by improving treatment completion rates, avoiding complications associated with long-term intravenous access, and improving patient quality of life. In contrast to binary outcomes that focus solely on clinical success or failure, we selected the primary DOOR outcome as it better reflects the full balance of efficacy, safety, and quality of life considerations clinicians and participants actually use to determine treatment. Rates of adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation and select adverse events of special interest (e.g., catheter-associated thrombosis) were numerically more frequent in the standard therapy group. However, overall DOOR and health-related quality of life scores were similar between dalbavancin and standard therapy, suggesting that the captured aspects of patient experience did not substantially differ between treatment groups. This result is consistent with other recent trials that sought to minimize or avoid prolonged intravenous antibiotics. Neither the Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotics trial (OVIVA), using European Quality of Life-5 Dimension score, nor the Partial Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotic Treatment of Endocarditis trial (POET), using Short Form 36, found significant differences in quality of life between parenteral versus oral treatment groups.37,38,40 It is unclear whether this lack of observed difference indicates that current tools fail to capture relevant differences or that the route of antimicrobial therapy minimally affects patient experience. Notably, while the survey used in this trial was intended to capture general function, it did not directly assess specific measures such as burdens associated with intravenous access, caregiver concerns, or the need for home health visits.

Importantly, treatment-emergent resistance developed in 1 patient within each treatment group. Treatment-emergent resistance to daptomycin has been well-described previously.32,41 Case reports of treatment-emergent resistance on dalbavancin describe similar susceptibility patterns to those we observed, typically daptomycin non-susceptibility and vancomycin intermediate resistance.18–20 Although infrequent, any instance of treatment-emergent resistance underscores the importance of adequate evaluation and management of deep-seated foci of infection including device removal and/or debridement.

Trial strengths included enrollment of persons who inject drugs (15.0% of participants) – a key population at risk of S. aureus bacteremia, and infections with MRSA (33.0% of participants). Additionally, we utilized a bacteremia-specific DOOR as the primary endpoint, which may better reflect the balance of risks and benefits than simple clinical efficacy outcomes. This primary outcome was paired with a more traditional secondary non-inferiority endpoint. The experimental group tested a simple 2-dose dalbavancin regimen based on pharmacological modeling and designed to reflect anticipated real-world use.7,8,14,15,17 Loss to follow-up rates for the primary outcome were within the estimates used for power calculations. Participants missing a day 70 assessment were handled conservatively (as clinical failure) and participants adjudicated as failures due to missingness were similar between treatment groups (Figure 1).

Limitations

Our study also has several key limitations. First, it was open label which may result in bias, although outcomes were assessed by a treatment-masked clinical adjudications committee. Second, mortality was lower than typically reported with S. aureus bacteremia, likely because participants were enrolled after clearance of bacteremia, selecting for a population more likely to survive. Third, inclusion of treatment discontinuation as a DOOR component might favor a long-acting agent since dalbavancin cannot be discontinued after the second dose, although a sensitivity analysis excluding this component was performed and the outcome was unchanged. Fourth, bacteremia duration >4 days was numerically more common among participants randomly assigned to standard therapy, suggesting that some participants in the standard therapy group may have had more severe infection. Fifth, late recurrence was numerically more common among participants with osteomyelitis receiving dalbavancin, though overall follow-up rates were lower for the prolonged day 180 follow-up and numbers were too small to make a reliable comparison. Sixth, since only a single 2-dose regimen was studied, it remains possible that select patient populations might have benefited from an alternative dosing regimen of dalbavancin. Seventh, discharge disposition was not captured, thus, while dalbavancin recipients had a shorter median length of hospital stay, the study results do not necessarily inform whether this allowed participants to be discharged directly home.

Conclusion

Among adult participants with complicated S. aureus bacteremia who achieved blood culture clearance, dalbavancin was not superior to standard therapy by desirability of outcome ranking. When considered with other efficacy and safety outcomes, these findings may help inform use of dalbavancin in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question:

Is dalbavancin a superior treatment option for complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia compared with standard care?

Findings:

In this randomized clinical trial that included 200 adults completing therapy for complicated S. aureus bacteremia, the probability of a more desirable outcome at day 70 with dalbavancin versus standard therapy was 47.7%, which did not achieve the prespecified criterion for superiority.

Meaning:

Among participants with complicated S. aureus bacteremia who achieved blood culture clearance, dalbavancin was not superior to standard therapy for achieving a more desirable outcome at day 70.

Funding:

This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under NIAID Award No. 5UM1Al104681. Study drug was provided by Abbvie.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, Duke University, or the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

Members of the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (arlg.org) were responsible for design and conduct of the study. Study drug was provided by AbbVie but employees of AbbVie were not involved in study conduct. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health served as study sponsor. The Emmes Company was responsible for collection, management and analysis of data. Staff from Abbvie did not have any role in data management or analysis. The NIH established an independent data and safety monitoring board to monitor safety. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors wish to thank Michael W. Dunne, MD; Sailaja Puttagunta, MD; and David Melnick, MD, who contributed to earlier protocol drafts.

Data Sharing Statement:

References

- 1.Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;400(10369):2221–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong SYC, Fowler VG Jr., Skalla L, Holland TL. Management of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia: A Review [Published online ahead of print]. JAMA. 2025. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2025.4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland TL, Cosgrove SE, Doernberg SB, et al. Ceftobiprole for Treatment of Complicated Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(15):1390–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler VG Jr., Boucher HW, Corey GR, et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):653–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller SC, Williams D, Gavgani M, et al. Rates of and Risk Factors for Adverse Drug Events in Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(1):11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billmeyer KN, Ross JK, Hirsch EB, Evans MD, Kline SE, Galdys AL. Predictors of adverse safety events and unscheduled care among an outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) patient cohort. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023;10:20499361231179668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper MM, Preslaski CR, Shihadeh KC, Hawkins KL, Jenkins TC. Multiple-Dose Dalbavancin Regimens as the Predominant Treatment of Deep-Seated or Endovascular Infections: A Scoping Review. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2021;8(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrothers TJ, Chittenden JT, Critchley I. Dalbavancin Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Target Attainment Analysis. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2020;9(1):21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunne MW, Puttagunta S, Giordano P, Krievins D, Zelasky M, Baldassarre J. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Single-Dose Versus Weekly Dalbavancin for Treatment of Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(5):545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jauregui LE, Babazadeh S, Seltzer E, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of once-weekly dalbavancin versus twice-daily linezolid therapy for the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1407–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raad I, Darouiche R, Vazquez J, et al. Efficacy and safety of weekly dalbavancin therapy for catheter-related bloodstream infection caused by gram-positive pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(3):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seltzer E, Dorr MB, Goldstein BP, Perry M, Dowell JA, Henkel T. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus standard-of-care antimicrobial regimens for treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(10):1298–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina KC, Lunowa C, Lebin M, et al. Comparison of Sequential Dalbavancin With Standard-of-Care Treatment for Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryson-Cahn C, Beieler AM, Chan JD, Harrington RD, Dhanireddy S. Dalbavancin as Secondary Therapy for Serious Staphylococcus aureus Infections in a Vulnerable Patient Population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(2):ofz028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Vinuesa D, Plata A, et al. DALBACEN cohort: dalbavancin as consolidation therapy in patients with endocarditis and/or bloodstream infection produced by gram-positive cocci. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2019;18(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman-Meza D, Weiss RE, Poimboeuf ML, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Long-Acting Lipoglycopeptides vs Standard-of-Care Antibiotics in Serious Bacterial Infections. JAMA Network Open. 2025;8(5):e2511641–e2511641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Polenakovik H, Barreras Beltran IA, et al. Emergence of Dalbavancin, Vancomycin, and Daptomycin Nonsusceptible Staphylococcus aureus in a Patient Treated With Dalbavancin: Case Report and Isolate Characterization. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(9):1641–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werth BJ, Jain R, Hahn A, et al. Emergence of dalbavancin non-susceptible, vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) after treatment of MRSA central line-associated bloodstream infection with a dalbavancin- and vancomycin-containing regimen. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(4):429.e421–429.e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werth BJ, Ashford NK, Penewit K, et al. Dalbavancin exposure in vitro selects for dalbavancin-non-susceptible and vancomycin-intermediate strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(6):910.e911–910.e918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner NA, Zaharoff S, King H, et al. Dalbavancin as an option for treatment of S. aureus bacteremia (DOTS): study protocol for a phase 2b, multicenter, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopewell S, Chan AW, Collins GS, et al. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Randomized Trials. JAMA. 2025;333(22):1998–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Adults and Children. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;52(3):e18–e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sader HS, Mendes RE, Duncan LR, Pfaller MA, Flamm RK. Antimicrobial Activity of Dalbavancin against Staphylococcus aureus with Decreased Susceptibility to Glycopeptides, Daptomycin, and/or Linezolid from U.S. Medical Centers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tebano G, Zaghi I, Baldasso F, et al. Antibiotic Resistance to Molecules Commonly Prescribed for the Treatment of Antibiotic-Resistant Gram-Positive Pathogens: What Is Relevant for the Clinician? Pathogens. 2024;13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King HA, Doernberg SB, Miller J, et al. Patients' Experiences With Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Bacterial Bloodstream Infections: A Qualitative Descriptive Study and Concept Elicitation Phase To Inform Measurement of Patient-reported Quality of Life. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(2):237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doernberg SB, Tran TTT, Tong SYC, et al. Good Studies Evaluate the Disease While Great Studies Evaluate the Patient: Development and Application of a Desirability of Outcome Ranking Endpoint for Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(10):1691–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King HA, Doernberg SB, Grover K, et al. Patients' Experiences With Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-Negative Bacterial Bloodstream Infections: Results From Cognitive Interviews to Inform Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(2):ofab622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang FY, Peacock JE Jr., Musher DM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: recurrence and the impact of antibiotic treatment in a prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(5):333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang W-S, Ho M-W, Lin P-C, et al. Clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of hematogenous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis, 12-year experience from a tertiary hospital in central Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2018;51(2):235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park K-H, Cho O-H, Lee JH, et al. Optimal Duration of Antibiotic Therapy in Patients With Hematogenous Vertebral Osteomyelitis at Low Risk and High Risk of Recurrence. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016;62(10):1262–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halperin M, Hamdy MI, Thall PF. Distribution-free confidence intervals for a parameter of Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney type for ordered categories and progressive censoring. Biometrics. 1989;45(2):509–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaye KS, Shorr AF, Wunderink RG, et al. Efficacy and safety of sulbactam-durlobactam versus colistin for the treatment of patients with serious infections caused by Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex: a multicentre, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority clinical trial (ATTACK). The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2023;23(9):1072–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pong S, Fowler RA, Mitsakakis N, et al. Noninferiority Margin Size and Acceptance of Trial Results: Contingent Valuation Survey of Clinician Preferences for Noninferior Mortality. Med Decis Making. 2022;42(6):832–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrel M, Smith M, Shi Q, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Outpatient Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(6):e2417199–e2417199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzalez PL, Rappo U, Mas Casullo V, et al. Safety of Dalbavancin in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infections (ABSSSI): Nephrotoxicity Rates Compared with Vancomycin: A Post Hoc Analysis of Three Clinical Trials. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(1):471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iversen K, Ihlemann N, Gill SU, et al. Partial Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotic Treatment of Endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li HK, Rombach I, Zambellas R, et al. Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotics for Bone and Joint Infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):425–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Kretser D, Mora J, Bloomfield M, et al. Early Oral Antibiotic Switch in Staphylococcus aureus Bacteraemia: The Staphylococcus aureus Network Adaptive Platform (SNAP) Trial Early Oral Switch Protocol. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;79(4):871–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bundgaard JS, Iversen K, Pries-Heje M, et al. Self-assessed health status and associated mortality in endocarditis: secondary findings from the POET trial. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(9):2655–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marty FM, Yeh WW, Wennersten CB, et al. Emergence of a clinical daptomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate during treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and osteomyelitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(2):595–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.