Abstract

Abstract

Background

Challenges within prehospital emergency care (PEC) have significant implications for the provision of emergency department (ED) care. However, ED overcrowding is a prevalent issue with negative impacts on patient outcomes. It can be attributed to multiple factors, such as non-emergency attendances, inaccessible alternative care service pathways (ACSPs) and inefficiencies in emergency medical service operations. ED overcrowding has prompted healthcare systems worldwide to implement interventions. These include tele-triaging, virtual ED and non-conveyance protocols that primarily aim to reduce demand for ED care and increase the supply of alternative services. However, despite such efforts, there remain unaddressed limitations that prevent PEC interventions from being successfully implemented. Moreover, prior studies and reviews have found mixed results, and that ED overcrowding interventions remain underused. Therefore, there is a need for this qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis to capture the complexities of implementation challenges and identify enablers required to complement PEC interventions.

Objectives

This systematic review and meta-synthesis aims to offer a consolidated overview of PEC interventions intended to reduce ED overcrowding. It focuses on presenting international perspectives on the current challenges these interventions face. The enablers presented in this review could also better inform the actions taken by healthcare systems aiming to implement similar interventions.

Methods

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Complete, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Scopus was conducted to obtain a set of qualitative studies. Following a quality appraisal with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool, data from the included studies were extracted and meta-synthesised.

Results

A final 21 qualitative intervention-based studies were included. Through these studies, four themes were identified: (1) types of PEC interventions to alleviate ED demands and right-site patients, (2) perceived benefits of interventions, (3) challenges in implementing interventions and (4) key enablers for successful implementation of interventions. Our results describe key factors such as the importance of ACSPs and support for PEC healthcare workers in the form of standardised guidelines, as well as education and training.

Conclusion

We further discuss how enablers can integrate into current PEC systems to complement the interventions explored. Discussions are concentrated on several key interventions (tele-triaging, virtual ED and non-conveyance protocols) as they were perceived to hold significant potential in addressing PEC challenges and could be further elevated through various enablers. Overall, we could conclude that each intervention needs to be complemented by enablers to optimise its benefits.

Keywords: Systematic Review, Health policy, International health services, Emergency Departments

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Included studies were sourced from a wide range of databases.

Quality of the studies was appraised and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist.

The majority of the 21 included studies were conducted in Westernised settings (n=19), limiting international perspectives and restricting comparisons to similar populations and cultures.

Relevant non-English studies and their findings may have been overlooked, as only articles in English were included in this review.

Introduction

Globally, Emergency Departments (EDs) are facing stark increases in demand for acute care, resulting in ED overcrowding,1,5 causing long wait times, ambulance ramping, delayed assessment and treatment, poorer quality of care and therefore poorer medical outcomes.4,7 Among the various factors, high non-emergency ED attendance is commonly cited to contribute towards ED overcrowding,1 8 9 which in turn could be caused by patients’ help-seeking behaviour (eg, perceived convenience and comprehensiveness of ED care),1 2 demographic and societal changes such as ageing populations with more complex chronic illnesses4 5 and supply factors (eg, lack of access to primary care or after-hours services).2 4 5 9

This has led to the growth of Pre-hospital Emergency Care (PEC) services and new interventions aimed at addressing root causes by proactively connecting individuals with appropriate resources and directing non-emergent cases to Alternative Care Service Pathways (ACSPs), thereby reducing the burden on emergency services and improving overall public health outcomes. ACSPs involve medical (eg, primary, allied health, mental health) and non-medical social services to direct non-emergent patients to appropriate care, reducing ED demand.10 Prior research has shown that PEC interventions that redirect non-emergency patients to outpatient community settings help to enhance patient access to ACSPs and are fundamental to mitigating ED overcrowding by addressing mismatches between supply and demand for appropriate healthcare services.11 Other studies have suggested that PEC interventions require legislation for them to effect meaningful change in reducing ED overcrowding, as healthcare providers and relevant stakeholders may require additional support when implementing novel interventions.12

However, despite heavy investments in implementing such interventions by many countries, some systematic reviews of quantitative studies have noted that the effectiveness of PEC interventions remains underused, and findings on their effectiveness can be inconsistent and contradictory.13 14 For instance, some studies found a non-significant reduction in ED use following increased capacity of ACSPs in community settings, while others reported a 9%–54% decrease in ED use.13 Patient education also showed great variability in reducing ED demand, with up to 80% reductions in one study, but non-significant reductions in others.13 14 Moreover, these systematic reviews commonly reported limitations of potential confounders that were not controlled for in the quantitative studies, such as social structures, cultural factors and the presence of comorbidities. Therefore, a qualitative meta-synthesis is needed to capture and account for such nuances present across studies. This would aid in the identification and consolidation of enablers which can help to advance PEC interventions by addressing implementation challenges.

The focus on input strategies such as ACSPs and implementation was shaped by two key considerations. First, the scope of the review was deliberately limited to PEC interventions aimed at diverting or triaging patients prior to ED presentation. While these upstream strategies have high potential impact, they appear to be less systematically reviewed compared with outflow-focused approaches. Second, the emphasis on implementation reflects the recognition that many PEC models exist in theory but are rarely adopted at scale. Understanding implementation can help identify critical factors such as resource constraints, stakeholder buy-in and organisational readiness. Therefore, this qualitative meta-synthesis aims to consolidate the existing literature on PEC interventions such as ACSPs (eg, tele-triaging, community referrals by emergency medical service (EMS), health and social care professionals). We also aim to highlight key challenges and enablers. The research question is: Among PEC interventions targeting patients before ED presentation, what factors influence the successful implementation of strategies connecting patients to ACSPs? The findings presented here can be used to inform future steps taken in implementing similar interventions, taking into special account the possible enablers mentioned.

Methodology

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients and the public were not involved in this study.

Search strategy

Initial searches were conducted on PubMed and Embase to identify keywords that encompassed the target population and exposure in the titles and abstracts of relevant studies. These keywords, along with Boolean operators and truncation symbols, were used to develop the full search strategy and expanded to six databases, PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Complete, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Scopus. Searches were restricted to research articles written in English and published from the inception of each database until 18 July 2024. The full search strategy is shown in online supplemental table 1. Subsequently, duplicated references were removed with EndNote V.21. Three reviewers (CC, SJ, HWK) screened the titles, abstracts and full text of possible studies. Any disagreement on the suitability of studies included was resolved through extensive discussion and consensus. The search was pre-planned to seek all available studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they (1) had any qualitative data, including mixed-method studies, where findings were obtained through focus group discussions, open-ended surveys or interviews, (2) analysed the perceptions of healthcare professionals and policymakers on benefits, challenges, enablers or implementation of innovations, (3) focused on PEC innovations and (4) published from the inception of each database until 18 July 2024. They were excluded if they (1) were not written in English, (2) did not have a qualitative study design or (3) focused on hospital throughput and output interventions, or were restricted to medical treatment or emergent care (eg, prehospital medical interventions for emergent cases or medication reviews).

Quality appraisal

Three reviewers (CC, SJ, HWK) independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool.15 CASP was used to facilitate quality appraisal by evaluating (1) clarity of research aims, (2) appropriateness of qualitative methodology, (3) study design, (4) participant recruitment and (5) data collection method. As well as considering (6) researcher-participant relations, (7) other ethical issues, (8) rigour of analysis, (9) clarity of findings and (10) value of the study. This was conducted through a 10-item questionnaire, with discrete ‘Yes’, ‘Can’t Tell’ and ‘No’ options, quantified as 3 points, 2 points and 1 point, respectively. CASP score of the included studies ranged from 27 to 30, with an average of 28.0 points (online supplemental table 2). This process was used to add rigour to the synthesis, rather than identifying and excluding studies with low CASP scores.15 16 Additionally, all studies were given equal consideration, regardless of CASP score.

Data extraction

The included studies were analysed, and relevant data were extracted by three reviewers (CC, SJ, HWK). As detailed in online supplemental table 3, the following information was extracted from the qualitative studies—study details (title, author, year and country of publication), methodology (aims, study design, analysis method), study characteristics (sample size, inclusion criteria, participants’ characteristics), intervention studied (type, capabilities) and results (themes, subthemes). The screening process was equally divided between the reviewers and took weeks.

Data synthesis

We adopted Sandelowski and Barroso’s approach to data meta-synthesis.17 Following data extraction, results from the studies were compared, and recurring findings were summarised and categorised into codes by four reviewers (CC, SJ, HWK, EC). Codes were further categorised into themes and subthemes. Discussions among the three reviewers were held regularly to resolve any discrepancies, with consultations from a fourth reviewer (YFL). The finalised themes and subthemes were used to generate new concepts through meta-synthesis. Triangulation was consistently applied during the data synthesis process, by drawing comparisons between the included studies, generated codes, subthemes and themes, to obtain a more robust and rigorous analysis of the findings.

Results

Characteristics of studies

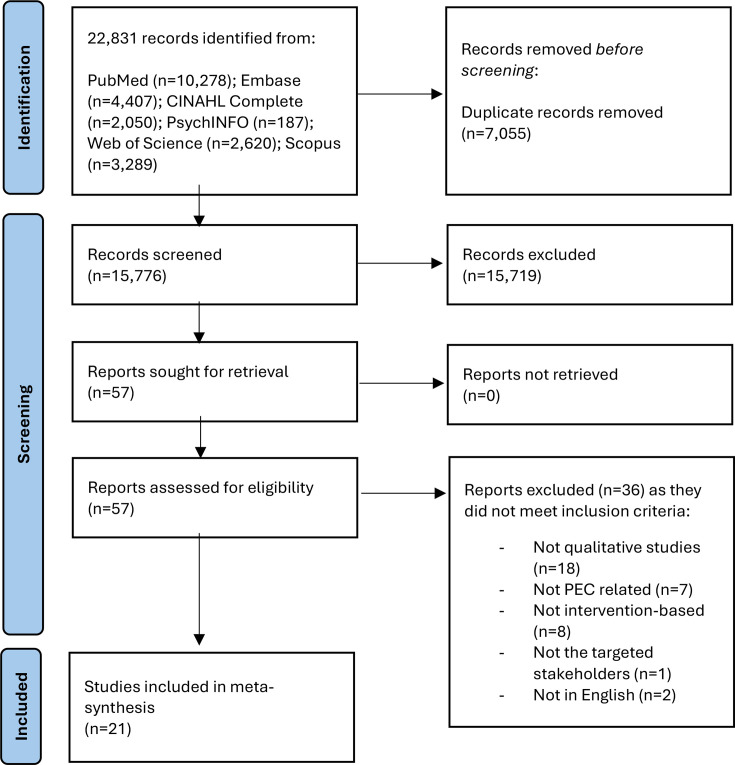

The search retrieved a total of 22 831 records across the six databases. Through the EndNote V.21 Software, 7055 duplicates were removed. Another 15 720 articles were removed via review of their title and abstract, and the remaining 57 articles were reviewed in full text. 21 articles were included in the final review (figure 1). Of these articles, most employed a descriptive qualitative (n=9)18,26 or mixed-method (n=8)27,34 study design. Some others used a participatory study design (n=1),35 grounded theory (n=2)36 37 or phenomenological approach (n=1).38 12 of the studies were conducted in Europe (UK, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, Czech Republic).19,2325 27 Four were published in North America (USA, Canada),26 30 37 38 two in Asia (Iran, India),18 34 another two in Australia32 36 and one in Africa (Rwanda).24 In most of the studies, data were collected via semistructured interviews (n=14).18,2931 38 39 Others used a combination of focus groups and individual interviews (n=4),3034,36 open-ended surveys (n=2)32 33 or focus group discussions (n=1).37 For data analysis, studies used content analysis (n=10),18,2022 28 30 thematic analysis (n=10)2123 24 26 27 29 35,39 or cross-case analysis (n=1).25 Online supplemental table 3 details study characteristics. Most studies involved healthcare professionals (emergency physicians, nurses and paramedics) as participants. Many also included healthcare administrators or policymakers. The studies’ participant characteristics are detailed in table 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. This depicts the screening process of the included studies. PEC, prehospital emergency care; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1. Participant characteristics of each study.

| Study | Paramedics | Physicians | Nurses | Call handlers | Healthcare administrators/policymakers | Information Technology (IT) representatives | Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammadi et al, 202218 | o | ||||||

| O’Hara et al, 201927 | o | o | o | o | |||

| Vicente et al, 202019 | o | ||||||

| Todorova et al, 202120 | o | ||||||

| Snooks et al, 200428 | o | ||||||

| O’Cathain et al, 201829 | o | o | o | o | |||

| Knowles et al, 201821 | o | o | |||||

| Brydges et al, 201538 | o | ||||||

| Vicente et al, 202122 | o | ||||||

| Scott et al, 202123 | o | o | o | ||||

| Schooley et al, 201330 | o | o | o | o | o | ||

| Raaber et al, 201631 | o | ||||||

| Niyonsaba et al, 202324 | o | o | o | o | o | ||

| Cassarino et al, 202035 | o | o | o | ||||

| Walker et al, 202136 | o | o | o | ||||

| Bagot et al, 202332 | o | o | o | o | |||

| Sykora et al, 202033 | o | o | |||||

| Menon et al, 202134 | o | o | o | ||||

| Armour et al, 202137 | o | ||||||

| Ramsay et al, 202225 | o | ||||||

| Shuldiner et al, 202226 | o |

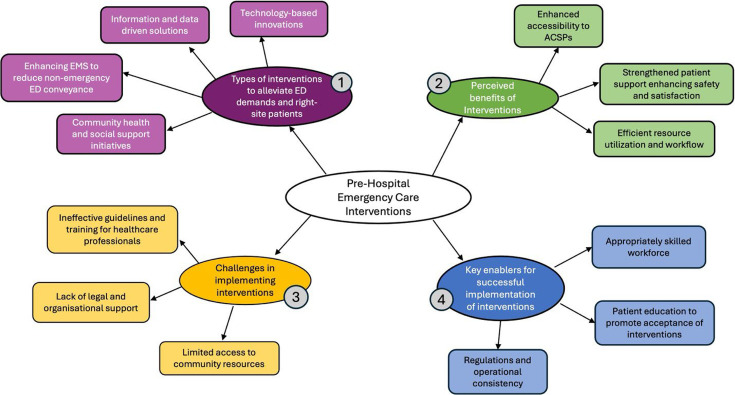

Findings of the studies were meta-synthesised, forming four main themes: (1) types of PEC interventions to alleviate ED demands and right-site patients, (2) perceived benefits of interventions, (3) challenges in implementing interventions and (4) key enablers for successful implementation of interventions (figure 2).

Figure 2. Overview of meta-synthesised themes and subthemes. This depicts the overview of the themes and subthemes generated in this systematic review. ACSPs, alternative care service pathways; ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical service.

Theme 1: types of PEC interventions to alleviate ED demands and right-site patients

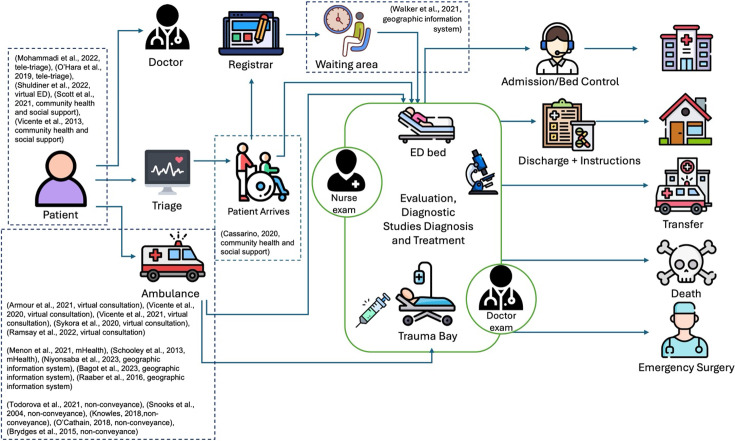

Four main types of PEC interventions were explored in the studies: (1) technology-based solutions, (2) information and data-driven solutions, (3) enhancing EMS to reduce non-emergency ED conveyance and (4) community health and social support initiatives. Overall, the interventions were introduced to address current limitations within PEC, and figure 3 illustrates how each intervention could integrate into current systems.

Figure 3. Patient flow diagram. This illustrates how the interventions could integrate into current PEC systems. ED, emergency department; PEC, prehospital emergency care.

Technology-based solutions

Tele-triaging was one technology-based solution studied.18 27 37 Some tele-triaging services had nurses or clinicians give medical advice to callers with non-emergency conditions, instead of an ambulance dispatch.18 27 In addition, O’Hara et al reported that call takers had access to a national directory of services and local sources of information, to help with directing patients to available ACSPs.27 This helped redirect non-emergency patients to alternative care services and prevented unnecessary ED visits, which reduced ED overcrowding.

Virtual consultations were also common.19 22 25 26 33 This includes virtual ED as described by Shuldiner et al, which connects patients with emergency physicians by coordinating same-day virtual consultations over Zoom (videoconferencing platform).26 This virtual ED model operated in tandem with a physical ED, resulting in several possible outcomes for patients: (1) care is managed during the virtual consultation, (2) advised to seek primary care, (3) scheduled for follow-up investigations or (4) scheduled for urgent in-person ED assessment.26 Other virtual consultation interventions aimed to reduce conveyance of non-emergency patients to EDs by providing paramedics with additional support from emergency physicians when assessing and treating patients on-site.19 22 25 37

Information and data-driven solutions

Software and mobile health tools have been used to facilitate secure collection, transfer and sharing of patient health data to enhance various processes within PEC.30 32 34 Software and systems, such as mobile Health (mHealth),30 are used by PEC healthcare professionals for enhanced transfer of patient care.30 34 mHealth can perform retrieval, storage and handover of patients’ prehospital biomedical data such as vital signs.30 The data are subsequently made available for healthcare providers to make more informed clinical decisions.30 34

Geographic information systems (GISs) could enhance the efficiency of EMS systems.24 31 36 Healthcare GISs support geolocation of response teams for efficient dispatch of ambulances.24 Moreover, data obtained through healthcare GISs (eg, ambulance real-time estimated arrival time, ED wait times) can be displayed in EDs to improve communication between prehospital and hospital to support clinical decision making and preparation.24 31 36 The positive perception of mHealth and GIS data by clinicians through these qualitative studies suggests a culture of openness to technology and innovation within the organisation.

Enhancing EMS to reduce non-emergency ED conveyance

Interventions intended to reduce ED conveyance of non-emergency patients by delivering a more appropriate level of care were explored in multiple studies.20 21 28 29 Protocols and decision-making processes on whether a patient requires ED conveyance have been analysed.21 Snooks et al studied paramedics’ perceptions on transporting suitable patients to more appropriate ACSPs, such as Minor Injury Units (MIUs).28

Besides ambulances with conventional EMS personnel, the dispatch of psychiatric emergency response teams, consisting of nurses specialised in psychiatric care, has been explored.20 This concept introduced a new avenue of care for patients with mental health issues, as they were equipped with access to patient medical records and an expanded drug arsenal (eg, basic sedatives, antipsychotic drugs).20

Another is the paramedics initiated community referrals by EMS programme.38 It leverages paramedics’ capabilities in identifying individuals at risk of deterioration. The programme enables paramedics to engage community healthcare services and initiate referrals for patients who do not require emergent care, but require long-term care directed at addressing unmet social or medical needs.38

Community health and social support initiatives

Strengthening continuity of care between hospital and community settings was identified as an important factor for meeting healthcare needs, thereby mitigating ED overcrowding.23 35 39 This could be achieved through health and social care professional teams comprised medical social workers and allied health professionals (eg, clinical pharmacists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists).35 They enhance integration of care in EDs by providing ‘specialised skills’ and ‘optimising care’ for patients with non-emergent needs such as management of chronic conditions.35 Scott et al also described ‘social prescribing’, where patients are similarly referred to non-clinical ACSPs (eg, befriending services, social activities) by primary care general practitioners (GPs), nurses and paramedics.23

Theme 2: perceived benefits of interventions

Several key benefits were identified across the studies reviewed: (1) enhanced accessibility to ACSPs, (2) strengthened patient support enhancing safety and satisfaction and (3) efficient resource utilisation and workflow. Overall, the interventions are not only intended to address PEC challenges, but also to enhance patient outcomes in the process.

Enhanced accessibility to ACSPs

From a clinician’s perspective, many telemedicine services were seen as a viable ACSP, thereby contributing towards reducing demand for ED care. Virtual ED, for instance, was viewed to be a suitable option for managing the care of patients who require ‘follow-up from a diagnostic test’, have ‘mental health issues’ and require support for ‘episodic care’.26 Therefore, ‘easing the burden of in-person care’26 and relieving pressure on EDs.19 26 27

In several studies, integrated community care models, such as ED-based health and social care professional teams were credited with building stronger linkages to community services, enabling safer discharge and reducing the likelihood of reattendance.35 Second, enhanced community care fosters preventative care,38 early intervention and better management of chronic diseases,35 resulting in overall improved community health and lower need for ED care.

The introduction of psychiatric emergency response teams in Todorova et al’s study increased non-conveyance rates by opening up ‘new dimensions of care for patients with mental illnesses’.20 Participants mentioned that they were able to ‘treat more patients at home’, giving patients ‘the right level of care from the beginning’.20 Therefore, similar interventions promoting non-conveyance could lower ED demand by providing appropriate levels of care.19 20 22 25 27 Perceived accessibility benefits of these ACSPs reflect more than just convenience, they signal a broader shift in what is considered legitimate, safe and acceptable care outside the ED. These may address a fundamental system gap, which is the mismatch between patient needs and the traditional ED-centric model of care.

Strengthened patient support enhancing safety and satisfaction

Conveyance of non-emergency patients to MIUs was perceived to be more efficient, as both the ‘ambulance service and patients benefitted in terms of job cycle time, (and) waiting time’.28 This translated into greater ‘satisfaction with care’ among MIU patients, who were reported to be ‘7.2 times as likely to rate their overall care as excellent as A&E (accident and emergency) patients’.28

Employing health and social care professional teams in EDs promoted integration of multidisciplinary perspectives into ED care to improve patient outcomes.35 Both patients and providers in Cassarino et al’s study expressed that the health and social care professional teams were able to provide accessible, comprehensive and timely treatment, leading to increased patient satisfaction.35

Virtual ED was also perceived to provide valuable care by ‘advising on the need for an in-person visit, booking a diagnostic test, referral to a specialist’ or outpatient follow-up.26 Virtual ED enhanced patient support by coordinating any ‘follow-up referrals to appropriate ACSPs’, thereby facilitating continuity of care following a virtual consultation.26

Several interventions were provided early assurance for patients. Virtual consultations between paramedics and emergency physicians were perceived to increase patient safety and trust due to the presence of a specialist providing guidance on clinical decisions.19 22 Hence, patients perceived decision-making on triaging, assessments and conveyance to be more well-informed and were more satisfied with their care, leading to decreased ED conveyance.19 22 Similarly, the presence of psychiatric nurses on psychiatric emergency response teams ‘increased patient confidence’, due to the perception that a psychiatric nurse would conduct ‘more reliable assessments’.20 These benefits suggest that the relational aspects of care such as trust, confidence, continuity, are central to perceived value.

Efficient resource utilisation and workflow

Digital technologies that connect near-patient data with hospital-based clinical teams are increasingly recognised for their potential to streamline care coordination, reduce avoidable demand and optimise the use of limited healthcare resources. These tools can enhance both patient flow and clinical decision-making, particularly in high-pressure environments such as PEC. One such example is the use of mHealth capabilities that relay information from prehospital to EDs, which could improve the efficiency of PEC workflows. Paramedics at the scene can transmit images and videos to EDs, allowing ED personnel to estimate the severity of a patient’s condition. In Schooley et al’s study,30 clinicians reported that visual data sent from the scene helped ‘raise the level of situational awareness and better allocate needed resources at the hospital’, facilitating timely interventions and reducing bottlenecks. Similarly, Bagot et al noted that early notification of diagnostic needs allowed teams to prepare for ‘scans or tests… straight away’, reducing delays in care on arrival and improving overall patient throughput.32

In parallel, GISs that integrate ED wait time and location data were found to support more efficient decision-making by prehospital staff. Most paramedics agreed that GISs’ healthcare data would assist them in diverting suitable patients to EDs with shorter wait times, facilitating load-spreading and enhancing efficiency of patient care.36 Importantly, while many of these digital tools were seen to improve efficiency, their perceived value extended beyond time savings. Clinicians valued technologies that supported more accurate triage, reduced unnecessary conveyance and enabled earlier access to diagnostics and specialist input. In this way, digital interventions were seen as enabling smarter and not just faster care.

Theme 3: challenges in implementing interventions

Challenges that limited the effectiveness of a proposed intervention or prevented successful implementation of interventions were identified: (1) ineffective guidelines and training for healthcare professionals, (2) lack of legal and organisational support, (3) limited access to community resources and (4) mismatch in patient expectations or misuse of interventions.

Lack of guidelines and training for healthcare professionals

Studies on both tele-triaging and ambulance non-conveyance expressed a lack of proper clinical guidelines. A participant of Mohammadi et al’s study on tele-triaging revealed that ‘existing guidelines are ambiguous’.18 This caused confusion among tele-triaging personnel, who felt that they consequently ‘could not give satisfactory counselling’ to patients. Therefore, ‘a single set of comprehensive protocols for dispatchers’ was perceived to be necessary.18 Similarly, ambulance personnel struggled to identify when and how to appropriately use and facilitate conveyance to ACSPs.29

This is compounded by inadequate training and education on referring patients to ACSPs for paramedics.18 28 38 Paramedics felt unprepared in making appropriate referrals as they were ‘unclear on how… (to) best handle situations’ and ‘unsure of the appropriate channels to go through’.38 These challenges could lead to ineffective directing of patients and put a patient’s life at risk if the wrong information is given in life-threatening situations.18 Furthermore, a lack of follow-through on referrals was mentioned to limit the effectiveness of referral pathways. Some participants felt that ‘community referrals by EMS… never got to where it’s supposed to go… They don’t really care if it’s going to go forward or not’.38 Such sentiments could result in a disinclination for patients and providers to use similar services in the future.

Lack of legal and organisational support

Risk aversion and fear of litigation among healthcare providers were raised in several studies. Risk management was viewed as a key consideration in effectively directing patients and delivering medical advice in tele-triaging. Providers and call takers were commonly described as risk averse, and therefore more predisposed to dispatching an ambulance or advising callers to seek ED care.27 29 Fear of litigation was also prevalent among paramedics.21 28 29 Some expressed that with the thought of litigation ‘always… in the back of your mind’,28 paramedics were less willing to practise non-conveyance.

Response time targets within EMS were seen as a crucial organisational barrier. Ambulance turnover times inevitably increase with more time spent assessing and treating patients during non-conveyance. This was seen to be ‘in direct contrast with traditional values and requirements associated with EMS…and transporting all patients without delay’.38 Due to resistance to such changes, response time targets were prioritised over making appropriate non-conveyance decisions, which were perceived to ‘take paramedics away from core frontline business’.29 Similarly, though social prescribing provides suitable alternatives for patients with social needs, participants of Scott et al felt that social prescribing was inappropriate, as ‘the time resources that that would take up would be horrendous’ and could result in a ‘massive demand on ambulance services’.23

Limited access to community resources

The lack of community resources was a key limitation for non-conveyance protocols and tele-triaging.19 21 27 28 Paramedics expressed concerns about not transporting patients to an ED, thereby limiting patient access to necessary investigations such as X-rays and lab tests.19 Similarly, O’Hara et al’s study mentioned that ‘the effectiveness of telephone advice is limited by the range of options available to clinicians’ for directing patients, and that the ‘availability of alternative options may reduce the level of recontacts’.27

Furthermore, some ACSPs, such as MIUs, were perceived to have insufficient facilities.28 This could limit conveyance or referring of patients to ACSPs as paramedics ‘don’t have the resources to do hear and treat effectively… (when MIUs are) massively under resourced’.21 These show that adequate resourcing and accessibility of ACSPs could be key determinants in reducing demand for ED care.

Theme 4: key enablers for successful implementation of interventions

Several key enablers were identified: (1) appropriately skilled workforce, (2) regulations and operational consistency, (3) collaborative and supportive structure and (4) addressing cultural perceptions and enhancing patient education to promote intervention acceptance. This theme considers how these enablers could facilitate the implementation of interventions or enhance their effectiveness as discussed in the studies.

Appropriately skilled workforce

Sustained education efforts are essential for tele-triaging personnel. This is to ensure that they are equipped with ‘updated academic knowledge’ and ‘awareness of clinical guidelines’,18 to give them the confidence and skills required for resolving calls, addressing both medical and social needs.22 27 This could help mitigate challenges such as lack of training and proper clinical guidelines, for more effective triaging and directing patients towards ACSPs.39

Other studies also noted that employing PEC healthcare providers with an extended and more specialised skillset beyond standard training could be beneficial.21 38 Paramedics with extended skills would have ‘more confidence to discharge patients at scene’,21 or recognise patients who require emergent care during non-conveyance protocols.21 38 Therefore, paramedics with specialised skill sets could help to further enhance non-conveyance rates.

Regulations and operational consistency

Though national healthcare policies in countries such as England advocate for non-conveyance and community referrals by EMS to ACSPs, studies have identified that these policies require further development and regulation,21 27 ‘given the inconsistency in availability and access to services’.27 Establishing formal referral pathways and triaging protocols could have several benefits. First, formal referral methods ‘filled a much-needed void’, by ensuring that referrals were thoroughly followed through with proper transfer of care.38 As such, patient healthcare needs could be better met, enhancing the effectiveness of referrals to ACSPs. Second, enforcing protocols or guidelines to support paramedics could also mitigate risk aversion and fear of litigation, thereby increasing ‘motivation levels to undertake non-conveyance’.21 Lastly, standardising protocols could reduce variation in telephone advice given,27 conferring consistent and reliable access to ACSPs through tele-triaging services.

A directory of services with information on available ACSPs is provided for tele-triaging personnel or paramedics to direct patients.23 27 These directories of services should be kept updated and relevant as they ‘play an important role in supporting staff to identify relevant services to which patients can be referred’,23 and enable greater efficiency in referring patients to ACSPs during tele-triaging, non-conveyance or social prescribing interventions. Otherwise, such directories could even ‘become a barrier to social prescribing when information is incomplete or out-of-date’,23 causing inaccurate referrals to be made.

Addressing cultural perceptions and enhancing patient education to promote intervention acceptance

Patients also have a role to play in supporting novel healthcare solutions and interventions.18 23 35 ‘Promoting acceptability and trust’ among patients was expressed to be ‘a crucial enabler of change’.35 This could be facilitated by patient education or awareness programmes18 23 that help patients ‘understand what (an intervention) entails and how it might be useful’ for patient care.23 Patient education should also convey the value of an intervention by describing how practical support is provided for patients, thereby promoting acceptance of and trust in new interventions.23 From a cultural perspective, while the need for certain ACSPs such as social prescribing is recognised, some patients may be resistant to such interventions. This resistance is often rooted in misunderstanding the concept or associated stigma. Similarly, clinician habits and cultural norms were identified as the strongest predictors of intention to use PEC app, but also as significant barriers to its adoption.

Discussion

This qualitative meta-synthesis sought to consolidate existing literature on the perception and experiences of PEC interventions to right site patients to appropriate services and alleviate ED demands. These include technology-based solutions (ie, virtual consultations, tele-triaging), data and information-driven solutions (ie, mHealth tools and GISs for collection of healthcare data), interventions that enhance EMS systems (ie, non-conveyance, psychiatric emergency response teams), community and social support initiatives (ie, health and social care professional teams and community referrals by EMS). However, each country has its distinct culture and demographics, and each healthcare system has its differences. Therefore, localised studies are needed to identify population-specific needs and adapt interventions to sociocultural contexts pertaining to healthcare delivery.

The concept of virtual consultations, although relatively matured, has gained new applications. This review focuses on the provision of virtual emergency medicine through virtual ED and virtual consultations that support EMS personnel.19 22 25 26 33 In particular, virtual ED was largely well-perceived in Shuldiner et al’s study, with 71% of participants willing to fully adopt the practice of virtual ED.26 As described in our results, this model of virtual ED was perceived to not only provide enhanced patient support, but also serve as an ACSP for patients with non-emergency conditions, with Kelly et al’s study reporting up to 70% of over 2000 cases being redirected away from physical EDs.40 All non-emergency patients discharged from this virtual ED model were referred to GPs or other community outpatient services for follow-ups, providing patients with a safety net for any unresolved health conditions. Hence, well-established pathways between virtual ED and ACSPs could be a contributing factor towards the high rate of diversion from physical EDs in this model.40 Other research studies have indicated the importance of appropriately skilled workforce and communication skills to be incorporated into emergency medicine training.41 42 Therefore, defining the role of virtual emergency medicine and determining which skillsets are most appropriate could be crucial for the advancement of virtual consultations. Some suggestions include continued education, supplementing virtual consultations models with a multidisciplinary team to facilitate patient care,42 as well as using the provision of virtual emergency medicine as an inroad into prolonging the careers of senior emergency physicians.41 However, cultural factors such as trust in digital care, expectations of face-to-face interactions and language or literacy barriers can affect patient engagement. In some populations, virtual care may be perceived as impersonal or inadequate, particularly among older adults or those with limited digital access or literacy.42 As such, the success of virtual EDs depends on culturally sensitive implementation strategies, including multilingual resources and education campaigns to bridge trust gaps.

Tele-triaging received contradicting views regarding its effectiveness. While it is intended to manage demand for ED care by directing suitable patients towards appropriate ACSPs, community resources are not easily accessible, limiting the extent to which a tele-triaging service can support patients.23 27 Therefore, several prior research studies have highlighted the importance of linking a tele-triage system to community-based ACSPs.43 44 For example, Eastwood et al’s study suggested that building partnerships with GPs or home visiting services for patient referrals could help to improve continuity of care and long-term patient outcomes through better management of chronic conditions.43 Another case study on the dispatch of a home care team to suitable non-emergency patients in Ireland made similar conclusions.45 It was reported that the provision of multidisciplinary care in this manner not only reduces non-emergency ED conveyance but also minimises future ED presentation by addressing both medical and social needs.45 Other ACSPs could also include health and social care professional teams in EDs. From our findings, these teams comprising medical social workers and allied health professionals could enhance integration of care in EDs for non-emergent needs.35 Furthermore, other reviews have shown that more of such ACSPs should be accessible 24/7 with the introduction of a tele-triage system; the lack thereof could have negative unintended consequences on the overall workload of EDs.44 Therefore, besides providing appropriate tele-triage services, future localised studies could explore which ACSPs should be connected to tele-triaging services. This could help identify healthcare needs of specific demographics and patient groups, as well as existing gaps in the supply of services. Allowing for a tele-triaging service and its network of ACSPs to be tailored to specific populations, potentially enabling effective diversion of non-emergency patients from EDs.44

From our findings, ambulatory non-conveyance protocols, such as psychiatric emergency response teams and conveyance to MIUs, face resistance from both providers and patients. Clinicians often cite risk aversion, fear of litigation and unclear triaging protocols as barriers to adoption.2127,29 Social and cultural expectations also play a role; patients may equate ambulance services with hospital care and view alternative dispositions as unsafe or dismissive, particularly in the absence of adequate explanation.44 This view is supported by a prior quantitative systematic review on similar non-conveyance interventions,46 which identified a fear of being held responsible for patient outcomes among EMS personnel, who therefore chose not to practise non-conveyance and sought to minimise risk by conveying patients to an ED. This could be further attributed to a lack of formal referral methods and comprehensive triaging protocols to help guide non-conveyance decisions. This is corroborated by multiple literature reviews,47,49 which also recommend the need for well-developed protocols48 that cater to the specific needs of individual healthcare systems.47 However, some reviews also noted that low success of non-conveyance could be attributed to suboptimal utilisation of the protocols rather than the protocols themselves.48 50 This suggests that proper and regular training and education on the use of protocols is required in tandem to ensure that EMS personnel are appropriately skilled and supported in practising non-conveyance.44 47 It could also be suggested that according greater legal and liability protection to EMS personnel could boost confidence levels, encouraging increased adoption of non-conveyance.46 However, there is a lack of evidence on how policies or regulations that confer greater liability protection to EMS personnel can impact non-conveyance rates. Liability protection to help address challenges associated with risk aversion or fear of litigation was also not extensively explored in the studies of this review. This presents a critical need for further evaluation of this avenue, potentially enabling non-conveyance as an intervention to reduce non-emergency ED conveyances.

Lastly, patient education and awareness could help to promote acceptance of and trust in novel PEC interventions.18 23 35 This is supported by a narrative review, which found that patient education initiatives could have larger impacts on ED use if they were incorporated into multifaceted interventions, compared with if they were implemented as stand-alone interventions.44 Patient education also emerged as a recurring theme in promoting trust and engagement.18 23 35 However, its effectiveness is often contingent on how well educational content is tailored to cultural values, health beliefs and literacy levels. Therefore, future studies could make evidence-supported suggestions on how patient education can be integrated with the implementation of specific interventions to reach appropriate target audiences. For instance, a population with a higher incidence of chronic diseases could benefit from programmes that empower patients with knowledge on self-management of chronic diseases during their regular primary care check-ups. Thereby supporting that increasing patient education could potentially generate public acceptance of and trust in new interventions.

Strengths and limitations

With multiple different types and iterations of interventions being analysed in this review, each study was heavily summarised for their key findings to capture the extensive breadth of interventions explored in present PEC systems. Furthermore, of the studies that used a mixed-method study design, only relevant qualitative data were extracted and analysed. Therefore, this review might not have fully reflected the depth and complexities of each study. Additional referencing to the original studies could be beneficial for interested readers. Nonetheless, there are strengths to simultaneously assessing different types of interventions and how they could potentially integrate with one another to offer a more comprehensive solution to multifaceted challenges that PEC systems face. Moreover, the interventions raised here are not necessarily new but can be given new perspectives, in terms of enhancements and enablers, with the qualitative studies reviewed here.

Nonetheless, there are some limitations. Our findings derived from the studies were made under different contexts and settings (eg, country and healthcare system, population healthcare needs, study design, data analysis method). Thus, local studies and further context-specific explorations should be used to corroborate the findings of this review and better inform the implementation of interventions under different settings.

Conclusion

This meta-synthesis offered insight into the global landscape of interventions intended to address challenges in PEC and provided an understanding of the limitations and key enablers that could enhance the implementation of interventions. It also highlights the multifaceted nature of PEC interventions and their dependence not only on technological efficacy or system integration, but also on the sociocultural environments in which they operate. Trust, education, expectations of care and accessibility all play critical roles in shaping how patients engage with PEC alternatives. However, our findings also show that these interventions still face some challenges in implementation. Lack of formal clinical guidelines, limited access to ACSPs and patient awareness were cited to be key challenges of non-conveyance and tele-triaging-related interventions. For which, standardised protocols and policy development could be key enablers, by conferring consistency to triaging and referral options as well as offering legal and management support for its providers.

Supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-097457).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Data availability free text: All data has been provided via supplemental files. Any further information can be requested from the corresponding author via email upon reasonable request.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:1358–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koh VTJ, Ong RHS, Chow WL, et al. Understanding patients’ health-seeking behaviour for non-emergency conditions: a qualitative study. Singapore Med J. 2023 doi: 10.4103/singaporemedj.SMJ-2020-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson G, Karlberg I. Lack of integration, and seasonal variations in demand explained performance problems and waiting times for patients at emergency departments: a 3 years evaluation of the shift of responsibility between primary and secondary care by closure of two acute hospitals. Health Policy. 2001;55:187–207. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morley C, Unwin M, Peterson GM, et al. Emergency department crowding: A systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0203316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartini M, Carbone A, Demartini A, et al. Overcrowding in Emergency Department: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions-A Narrative Review. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10:1625. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ting JYS. The potential adverse patient effects of ambulance ramping, a relatively new problem at the interface between prehospital and ED care. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1:129. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.43201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter EJ, Pouch SM, Larson EL. The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46:106–15. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su Y, Sharma S, Ozdemir S, et al. Nonurgent Patients’ Preferences for Emergency Department Versus General Practitioner and Effects of Incentives: A Discrete Choice Experiment. MDM Policy Pract. 2021;6:23814683211027552. doi: 10.1177/23814683211027552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:126–36. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar A, Liu Z, Ansah JP, et al. Viewing the Role of Alternate Care Service Pathways in the Emergency Care System through a Causal Loop Diagram Lens. Systems. 2023;11:215. doi: 10.3390/systems11050215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savioli G, Ceresa IF, Gri N, et al. Emergency Department Overcrowding: Understanding the Factors to Find Corresponding Solutions. J Pers Med. 2022;12:279. doi: 10.3390/jpm12020279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabin E, Kocher K, McClelland M, et al. Solutions To Emergency Department ‘Boarding’ And Crowding Are Underused And May Need To Be Legislated. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1757–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan SR, Chang AM, Alqatari M, et al. Non-emergency department interventions to reduce ED utilization: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:969–85. doi: 10.1111/acem.12219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flores-Mateo G, Violan-Fors C, Carrillo-Santisteve P, et al. Effectiveness of organizational interventions to reduce emergency department utilization: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler A, Hall H, Copnell B. A Guide to Writing a Qualitative Systematic Review Protocol to Enhance Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Health Care. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13:241–9. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadelson S, Nadelson LS. Evidence‐Based Practice Article Reviews Using CASP Tools: A Method for Teaching EBP. Worldviews Ev Based Nurs. 2014;11:344–6. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:905–23. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammadi F, Jeihooni AK, Sabetsarvestani P, et al. Exploring the challenges to telephone triage in pre-hospital emergency care: a qualitative content analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;22 doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08585-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vicente V, Johansson A, Ivarsson B, et al. The Experience of Using Video Support in Ambulance Care: An Interview Study with Physicians in the Role of Regional Medical Support. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8:106. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todorova L, Johansson A, Ivarsson B. A Prehospital Emergency Psychiatric Unit in an Ambulance Care Service from the Perspective of Prehospital Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;10:50. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10010050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowles E, Bishop-Edwards L, O’Cathain A. Exploring variation in how ambulance services address non-conveyance: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e024228. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vicente V, Johansson A, Selling M, et al. Experience of using video support by prehospital emergency care physician in ambulance care - an interview study with prehospital emergency nurses in Sweden. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21:44. doi: 10.1186/s12873-021-00435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott J, Fidler G, Monk D, et al. Exploring the potential for social prescribing in pre-hospital emergency and urgent care: A qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29:654–63. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niyonsaba M, Nkeshimana M, Uwitonze JM, et al. Challenges and opportunities to improve efficiency and quality of prehospital emergency care using an mHealth platform: Qualitative study in Rwanda. Afr J Emerg Med. 2023;13:250–7. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2023.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsay AIG, Ledger J, Tomini SM, et al. Prehospital video triage of potential stroke patients in North Central London and East Kent: rapid mixed-methods service evaluation. Southampton (UK): National Institute for Health and Care Research; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuldiner J, Srinivasan D, Hall JN, et al. Implementing a Virtual Emergency Department: Qualitative Study Using the Normalization Process Theory. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9:e39430. doi: 10.2196/39430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Hara R, Bishop-Edwards L, Knowles E, et al. Variation in the delivery of telephone advice by emergency medical services: a qualitative study in three services. BMJ Qual Saf . 2019;28:556–63. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snooks H, Foster T, Nicholl J. Results of an evaluation of the effectiveness of triage and direct transportation to minor injuries units by ambulance crews. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:105–11. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.009050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Cathain A, Knowles E, Bishop-Edwards L, et al. Understanding variation in ambulance service non-conveyance rates: a mixed methods study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schooley B, Abed Y, Murad A, et al. Design and field test of an mHealth system for emergency medical services. Health Technol. 2013;3:327–40. doi: 10.1007/s12553-013-0064-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raaber N, Duvald I, Riddervold I, et al. Geographic information system data from ambulances applied in the emergency department: effects on patient reception. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:39. doi: 10.1186/s13049-016-0232-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagot KL, Bladin CF, Vu M, et al. Factors influencing the successful implementation of a novel digital health application to streamline multidisciplinary communication across multiple organisations for emergency care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2024;30:184–98. doi: 10.1111/jep.13923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sykora R, Renza M, Ruzicka J, et al. Audiovisual Consults by Paramedics to Reduce Hospital Transport After Low-Urgency Calls: Randomized Controlled Trial. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2020;35:656–62. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X2000117X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menon AK, Adhya S, Kanitkar M. Health technology assessment of telemedicine applications in Northern borders of India. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77:452–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cassarino M, Quinn R, Boland F, et al. Stakeholders’ perspectives on models of care in the emergency department and the introduction of health and social care professional teams: A qualitative analysis using World Cafés and interviews. Health Expect. 2020;23:1065–73. doi: 10.1111/hex.13033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker K, Stephenson M, Loupis A, et al. Displaying emergency patient estimated wait times: A multi-centre, qualitative study of patient, community, paramedic and health administrator perspectives. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;33:425–33. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armour R, Helmer J, Tallon J. Paramedic-delivered teleconsultations: a grounded theory study. CJEM. 2022;24:167–73. doi: 10.1007/s43678-021-00224-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brydges M, Spearen C, Birze A, et al. A Culture in Transition: Paramedic Experiences with Community Referral Programs. CJEM . 2015;17:631–8. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly JT, Mitchell N, Campbell KL, et al. Implementing a virtual emergency department to avoid unnecessary emergency department presentations. Emerg Med Australas. 2024;36:125–32. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.14328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staib A, Gourley S. Virtual emergency department: It is not all in the name. Emerg Med Australas. 2023;35:894–5. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.14324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talevski J, Semciw AI, Boyd JH, et al. From concept to reality: A comprehensive exploration into the development and evolution of a virtual emergency department. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open . 2024;5:e13231. doi: 10.1002/emp2.13231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eastwood K, Morgans A, Stoelwinder J, et al. The appropriateness of low-acuity cases referred for emergency ambulance dispatch following ambulance service secondary telephone triage: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van den Heede K, Van de Voorde C. Interventions to reduce emergency department utilisation: A review of reviews. Health Policy. 2016;120:1337–49. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Brien C, Hogan L, Ward P, et al. Pathfinder; alternative care pathways for older adults who phone the emergency medical services in North Dublin: a case study. IJOT . 2022;50:58–62. doi: 10.1108/IJOT-12-2021-0030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oosterwold J, Sagel D, Berben S, et al. Factors influencing the decision to convey or not to convey elderly people to the emergency department after emergency ambulance attendance: a systematic mixed studies review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021732. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blodgett JM, Robertson DJ, Pennington E, et al. Alternatives to direct emergency department conveyance of ambulance patients: a scoping review of the evidence. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29:4. doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-00821-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fraess-Phillips AJ. Can Paramedics Safely Refuse Transport of Non-Urgent Patients? Prehosp Disaster med. 2016;31:667–74. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X16000935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ebben RHA, Vloet LCM, Speijers RF, et al. A patient-safety and professional perspective on non-conveyance in ambulance care: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25:71. doi: 10.1186/s13049-017-0409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snooks HA, Dale J, Hartley-Sharpe C, et al. On-scene alternatives for emergency ambulance crews attending patients who do not need to travel to the accident and emergency department: a review of the literature. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:212–5. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695–700. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]