Abstract

Ferrate (Fe(VI)) is a prospective green oxidant owing to producing highly reactive Fe(IV)/Fe(V) for micropollutant degradation. However, the performance is significantly compromised by the severe side reaction of Fe(VI) self-decay with H2O, generating H2O2 byproduct that quickly quenches Fe(IV)/Fe(V). In this study, we synthesized a single-ruthenium-atom catalyst (RuGN) to activate Fe(VI) to selectively produce Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) for antibiotic degradation, with record-fast ciprofloxacin (CIP) degradation kinetics (~18.7 min−1 g−1 L). Since Fe(VI) preferentially reacts with RuGN rather than H2O, RuGN inhibits Fe(VI) self-decay, thus decreasing the H2O2 production. Moreover, RuGN consumes H2O2 (that quenches Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V)) in the reaction system, which significantly improves the Fe(VI) utilization rate. Compared with other typical transition metal single-atom catalysts, RuGN exhibits moderate interactions with Fe(VI) and thus facilitates the electron transfer via Ru-O-Fe coordination to activate Fe(VI) for efficient CIP degradation. The RuGN/Fe(VI) system resists interference from background substances coexisting in water, achieving efficient CIP degradation under complex water chemistry conditions and in real water samples. The system can also efficiently degrade CIP in continuous-flow reactors. This work develops a promising strategy for improving Fe(VI) activation via regulating the interaction between the metal site and Fe(VI), holding immense potential for deep wastewater purification.

Subject terms: Heterogeneous catalysis, Pollution remediation

RuGN single atom catalyst with Ru-O4 structure can effectively mitigate the self-decay of Fe(VI), eliminate the H2O2 byproduct, and activate Fe(VI) through Ru-O-Fe coordination, resulting in excellent degradation performance of the RuGN/Fe(VI) system towards micropollutants in water.

Introduction

Emerging micropollutants such as antibiotics in water bodies present significant threats to ecological security and human health1,2. To address this issue, advanced oxidation processes, leveraging the generation of reactive oxidizing radicals (e.g., hydroxyl and sulfate radicals), have been extensively studied as potential means of treating micropollutants in water3,4. However, these reactive radicals with short half-life periods (10−6–10−9 s) can be easily consumed by background substances such as co-existing ions and natural organic matter (NOM) in water before reacting with target organic pollutants, which ultimately reduces the efficacy of pollutant degradation5,6.

Due to the production of highly reactive Fe(IV) (FeIVO44−) and Fe(V) (FeVO43−) intermediates with long half-life periods (~0.1 s), ferrate (FeVIO42–, denoted as “Fe(VI)”) has been employed in the field of organic pollutants degradation7–9. Note that this Fe(VI) self-decay process with H2O simultaneously generates H2O2 that can quench Fe(IV)/Fe(V) (Eqs. S1–7), which significantly decreases the utilization rate of Fe(VI)10–13. Since homogeneous agents such as reductive metal ions13,14, sulfite, and low molecular-weight organic acids can efficiently provide electrons15,16, they have been used to activate Fe(VI) to produce Fe(IV)/Fe(V), and inhibit the side reaction between Fe(VI) and H2O. However, these techniques inevitably introduce undesired dissolved products, which would potentially lead to secondary contamination. Therefore, it motivates us to explore heterogeneous catalysts that enable the selective formation of reactive Fe(IV)/Fe(V) species with minimal side reactions to produce H2O2.

Via the coordination of metal sites with the oxygen atom of Fe(VI), metal-based heterogeneous catalysts, rather than H2O, can preferentially provide electrons to activate Fe(VI) and thus efficiently avoid the self-decay of Fe(VI) with H2O17,18. However, the efficiency of Fe(VI) activation is still limited by the sluggish electron transfer process in typical metal catalysts due to the insufficient exposed reactive metal sites for Fe(VI) coordination. To address this issue, one effective method is the engineering of metal single atom sites that can provide numerous exposed reactive sites to improve electron transfer from metal catalysts to Fe(VI). Developing efficient single-atom catalysts (SACs) by loading appropriate metal single atoms on catalyst support to simultaneously regulate Fe(VI) coordination and the subsequent electron transfer process is crucial for Fe(VI) activation19,20. Ruthenium (Ru) species, especially Ru(III), containing an electronic configuration in half-filled 4d orbitals (4d5), prefer to be the electron donor, which has been reported to provide electrons to activate periodate for the production of reactive species and Ru(IV)/Ru(V)21. Inspired by the intrinsic property of Ru(III), we speculate that deposing Ru(III) single atom on a suitable support can interact with and donate electron to Fe(VI), satisfying the requirement for inhibited Fe(VI) self-decay and effective Fe(VI) activation to produce highly reactive Fe(IV)/Fe(V).

In this work, we provide a promising strategy for the fabrication of Ru SAC furnished graphene supports (RuGN) for the inhibition of Fe(VI) self-decay and efficient Fe(VI) activation to produce Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) via an electron transfer process. It achieved record-fast CIP decomposition kinetics (~18.7 min−1 g−1 L, complete removal within 7 min), surpassing other previously reported Fenton-like systems. We demonstrate that RuGN can significantly improve the utilization rate of Fe(VI) via the production of Ru(V), and the mitigation of H2O2 intermediate that can quench Fe(IV)/Fe(V). Compared with other typical transition metal SACs, RuGN exhibits moderate interactions with Fe(VI) and inhibits excessive elongation of the Fe-O bond, facilitating the efficient electron transfer via Ru-O-Fe coordination to activate Fe(VI) for efficient CIP degradation. The RuGN/Fe(VI) system shows superior efficacy in treating CIP in complex water matrix conditions and real water samples, including waste water, tap water, sea water, and lake water. Ultimately, the RuGN catalyst was integrated into different continuous-flow reactors for practical CIP degradation, and achieved efficient CIP degradation (0.17 min−1 for cycling-pass reactor and >91% removal rate for single-pass reactor within successive 12 h). These results demonstrate that the RuGN SAC designed in this study is a credible option for the activation of Fe(VI) and holds promise for micropollutant remediation in water.

Results

Characterization of RuGN SAC

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images reveal that RuGN preserves the two-dimensional structure of graphene (GN) while displaying a rough surface (Supplementary Fig. 1). Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) shows the presence of single Ru atoms (highlighted by green circles) dispersed throughout the GN matrix (Fig. 1a, b). The associated elemental mapping exhibited uniform distribution of Ru atoms, with no observed aggregation of metal particles (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Structure characterization and local atomic coordination environment analysis of Ru-based catalysts.

a HAADF-STEM image and b AC HAADF-STEM image of RuGN, the single atoms are marked with green circles in (b). c Elemental mapping for RuGN corresponding with (a). d Ru K-edge XANES spectra (inset: relationship between Ru K-edge absorption energy (E0) and oxidation state for RuGN) and e k3-weighted Fourier-transformed EXAFS of Ru foil, RuO2, and RuGN. f Corresponding K-edge EXAFS fitting curves in R space for RuGN. Inset: optimized model of RuGN: Ru (red), O (yellow), and C (gray). WT-EXAFS plots for K-edge for g Ru foil, h RuGN, and i RuO2.

No characteristic peak for metallic Ru (JCPDS, 06-0663) or RuO2 (JCPDS, 43-1027) was observed in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of RuGN (Supplementary Fig. 3)22. The result confirmed that Ru species in RuGN was not in the form of Ru particles or RuO2 but Ru single atoms23. The two broad and weak diffraction peaks at approximately 26° (002) and 44° (101) were attributed to the defective and disordered GN structure24,25. Raman spectra reveal an intensity ratio (ID/IG) of the D band (1348 cm−1) to the G band (1588 cm−1) of 0.94 for RuGN, which is lower than the reported GN value26, indicating the presence of carbon-defects on the surface of RuGN (Supplementary Fig. 4).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of RuGN show the Ru 3p3/2 peaks at 463 eV (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating that Ru is in an oxidation state of Ru(III)27. To further investigate the coordination environment of Ru within the RuGN catalyst at the atomic level, we conducted X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements. The X-ray absorption near-edge structure reveals that the absorption edge position for RuGN lay between that of Ru foil and RuO2 references, but is notably closer to that of RuO2 (Fig. 1d). The oxidation state of Ru species was calculated to be +3.1 based on the linear fitting curve of Ru valence vs. Ru K-edge absorption energy (E0) that determined from maximum value in the first-order derivative (the inset of Fig. 1d). Therefore, the Ru species in RuGN predominantly exist in an oxidative state close to Ru(III) which is consistent with the XPS results. Further examination of the precise Ru coordinative structures was conducted through the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis (Fig. 1e). The EXAFS of RuGN exhibits a broad peak at approximately 1.44 Å, which can be attributed to the Ru-O coordination of atomic Ru coordinated with O28,29. When comparing with Ru foil and RuO2, RuGN shows no characteristic peak corresponding to Ru-O bond (1.59 Å) from clustered RuO2 and metallic Ru-Ru bond (2.4 Å) from Ru foil, which means Ru is located on the surface of the GN with an isolated single atomic structure.

The fitted curves (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 6) and quantitative EXAFS fitting parameters (Supplementary Table 1) for RuGN suggest a coordination number of 3.7 for Ru-O bonding at an average distance of 1.86 Å. These fitting results suggest a square-pyramidal configuration for the Ru-O4 coordination structure (schematically shown in the inset of Fig. 1f), which is similar to the Mn-N/O bonding coordination reported in Mn-N3O1 SAC30. The wavelet transform (WT) plot of Ru foil displays a prominent signal (9.7 Å−1, 2.4 Å) attributed to metallic Ru-Ru bonds, while the two main WT signals (6.9 Å−1, 1.6 Å and 8.5 Å−1, 3.0 Å) are assigned to Ru-O and the Ru-Ru bonds from RuO2 (Fig. 1g–i). In contrast, RuGN exhibits a prominent WT signal around 4.0 Å−1 in k space and 1.3 Å in R space, attributed to Ru-O bonds. These observations collectively validate the configuration of atomic Ru with Ru-O4 coordination in RuGN.

Catalytic performance of the RuGN/Fe(VI) system

The performance of GN supported SACs (MGN, M = Ru, Pt, Co, and Fe) in activating Fe(VI) was assessed using CIP as a representative micropollutant (Supplementary Table 2). Only approximately 3, 30, and 9% of CIP has been removed by the control systems, including the Fe(VI), RuGN and GN/Fe(VI) systems (Fig. 2a), respectively, whereas the RuGN/Fe(VI) leads to a complete elimination of CIP within merely 7 min. Notably, the observed pseudo-first-order CIP degradation rate constant (kobs) value for the RuGN/Fe(VI) of 0.935 min−1 is 187, 14, and 58 times higher than that for the Fe(VI) (0.005 min−1), RuGN (0.065 min−1), and GN/Fe(VI) (0.016 min−1) systems, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7), underscoring the essential role of Ru single-atom sites in the Fe(VI) activation. The optimal amounts of the RuGN and Fe(VI) added to the system have been determined to be [RuGN] = 50 mg L−1 and [Fe(VI)] = 30 μM (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Fig. 2. Catalytic performance and active species production in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system.

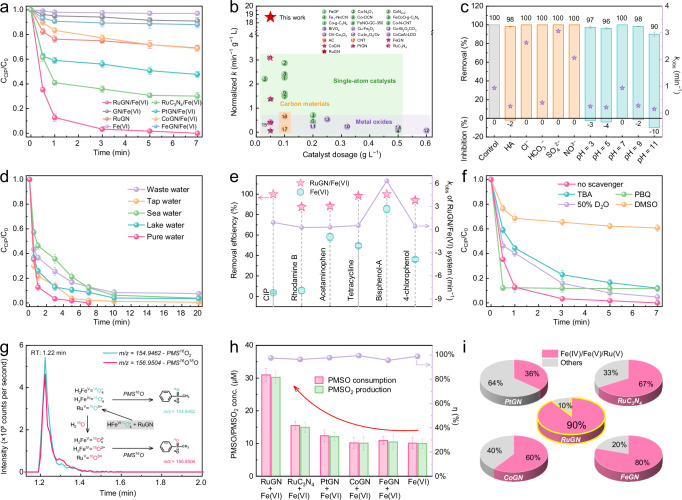

a Removal of CIP in various reaction systems. b Comparison analysis of normalized kinetics of emerging pollutant degradation in this study and the literature reports (details in Supplementary Table 4). c The impact of water chemistry factors on the RuGN/Fe(VI) system (removal (%) refers to the percentage of CIP removed in different systems, while inhibition (%) refers to the inhibition percentage of CIP removal compared to the control group). d The degradation rates of CIP in diverse aqueous medium when using the RuGN/Fe(VI) system as the degradation system. e Comparison of the degradation rates of multiple contaminants in the Fe(VI) and RuGN/Fe(VI) systems. f CIP degradation performance in the presence of active species quencher. g EIC of PMS16O16O and PMS16O18O generated from the oxidation of PMS16O in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system in H218O (inset: the reaction process in the RuGN/Fe(VI)/PMS16O/H218O system). h The PMSO/PMSO2 concentration and PMSO to PMSO2 conversion rate (η) in the SACs/Fe(VI) and Fe(VI) alone systems (the red arrow indicates that the production of PMSO2 is the highest in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system among these Fe(VI)-based systems). i The contribution ratios of high-valent metal intermediates and other reactive species over different SACs. Reaction conditions: (a, c–f, h) If not otherwise specified, all the batch experiments were conducted in [pollutant] = 10 μM, [catalyst] = 50 mg L−1, [Fe(VI)] = 30 μM, reaction time = 7 min. c [HA] = 0.5 mg L−1, [Cl−] = [HCO3−] = [SO42−] = [NO3−] = 5 mM, reaction time = 20 min. e [CIP] = [RHB] = [APAP] = [TC] = [BPA] = [4−CP] = 10 μM, reaction time = 10 min. f [TBA] = 50 mM, [PBQ] = 0.5 mM, [DMSO] = 50 mM. h [PMSO] = 50 μM. Error bars represent the standard deviation and are calculated based on three independent experiments.

The RuGN/Fe(VI) system demonstrates superior removal rates in CIP degradation (100% in 7 min) compared to that of the PtGN/Fe(VI) (52%), CoGN/Fe(VI) (31%), and FeGN/Fe(VI) (12%) systems, which suggests Ru single-atom sites exhibit higher reactivity than Pt, Co, and Fe sites. The functional role of GN supports has been proven to be beneficial for the CIP degradation—only approximately 70 and 75% of CIP was degraded within the first 7 min when using an alternative g-C3N4 support for Ru atoms (RuC3N4/Fe(VI)) or homogeneous Ru3+/Fe(VI) systems (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 9). We also investigated the effects of various oxidants on the degradation efficiency, founding that RuGN/Fe(VI) exhibits high performance among RuGN/H2O2, RuGN/PMS, and RuGN/PDS systems in terms of CIP removal efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating that RuGN/Fe(VI) may generate more reactive species for CIP degradation.

We have conducted a comparative analysis of the RuGN/Fe(VI) system with several state-of-the-art catalytic systems that are reported for the degradation of emerging organic pollutants using Fe(VI) (Supplementary Table 3) and other oxidants (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 4). This analysis, which specifically focused on catalyst dosage and kinetic rates, reveals that the RuGN/Fe(VI) system demonstrates fast reaction kinetics (~18.7 min−1 g−1 L) with a low catalyst dosage, which is superior to that of previously reported SACs, metal oxides, and carbon-based systems (Fig. 2b).

Various water chemistry factors, including NOM, inorganic ions, and pH, may influence the efficacy of wastewater treatment based on previous reports31–33. We investigated the impact of humic acid (HA), a representative NOM, on the degradation of CIP using the RuGN/Fe(VI) system. With an increase in HA concentration from 0.5 to 5 mg L−1, the removal rate decreased from 100 to 84% (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). The inhibited degradation performance for CIP degradation can be attributed to the competition between HA and CIP to consume reactive species in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system. A similar phenomenon has been previously reported in Fe(VI)-based systems34,35, especially with low concentration of Fe(VI)36. With slightly increasing Fe(VI) dosage to 50 μM, it can completely degrade CIP within 5 min even in the presence of 5 mg L−1 HA (Supplementary Fig. 11c). To evaluate the effect of inorganic ions on CIP degradation, four representative ions (Cl−, HCO3−, SO42−, and NO3−) were introduced individually, and the removal rates remained consistently at approximately 100% under all circumstances (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, the kobs bolsters from 0.935 min−1 (without the addition of inorganic ions) to 2.6, 3.1, and 2.1 min−1 after adding 5 mM Cl−, SO42−, and NO3−, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 12). This enhancement can be attributed to the formation of other reactive species (·Cl, SO4·−, etc.)15,37. Moreover, owing to the efficient Fe(VI) activation by RuGN to produce highly reactive species, the RuGN/Fe(VI) system demonstrates efficient CIP degradation over a broad pH range from 3 to 11 with the highest degradation kinetics at pH 7 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 13). High degradation performance at the neutral condition has been also observed in previously reported systems based on Fe(VI) activation16,38,39.

To further illustrate the versatility of the RuGN/Fe(VI) system in degrading CIP in real aquatic environments, the degradation rates of CIP in tap water, lake water, sea water and waste water (99.5%, 96.4%, 96.1%, and 92.4%, respectively) are comparable to these in pure water (Fig. 2d). Note that the degradation rates are negatively related to the CODMn in real water samples (Supplementary Table 5). The slightly inhibited degradation performance could be attributed to the consumption of reactive species by NOM or dissolved organic matter co-existing in real water samples40,41. The above observations demonstrate that the RuGN/Fe(VI) system can effectively circumvent interference from environmental impurities and serve as a promising technique in practical water decontamination.

The RuGN/Fe(VI) system can effectively degrade CIP with different initial concentrations range from 1 to 15 μM (Supplementary Fig. 14). Furthermore, RuGN/Fe(VI) system also demonstrates highly efficient degradation of various representative emerging micropollutants, including Rhodamine B, acetaminophen, tetracycline, bisphenol A and 4-chlorophenol with degradation percentages exceeding ~90% (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 15, and Supplementary Table 6). The results significantly show the great universality of RuGN/Fe(VI) system in micropollutant degradation.

Identification of active species in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system

The redox reaction of Fe(VI) and Ru species results in the formation of Fe(IV)/Fe(V) and Ru(V) species as the primary active species (see details in the next section), and Fe(IV)/Fe(V) exhibit 2–5 orders of magnitude higher reactivity with organics than Fe(VI)21,42–44, accompanied by the generation of several intermediate (e.g ·OH, ·O2−, 1O2) that was detected by electron spin resonance (ESR) (Supplementary Fig. 16). To identify the dominant active species in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system, we conducted quenching and ESR experiments. Our findings indicate that ·OH has minor contributions to CIP degradation, as evidenced by using tert-butyl alcohol (TBA, with kTBA/·OH of 6 × 108 M−1 s−1)45, which resulted in only a slight reduction in the CIP removal rate to 88% (Fig. 2f). The use of p-benzoquinone (with of 1 × 109 M−1 s−1)45 as a ·O2− quencher had an insignificant effect on CIP removal. Purging O2 or N2 (to remove dissolved O2) into the RuGN/Fe(VI) system did not significantly affect CIP degradation (Supplementary Fig. 17), which indicated that ·O2− and its precursor (dissolved O2) did not contribute to CIP degradation in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system17. The characteristic peak intensity of ·OH and ·O2− intermediates in corresponding ESR spectra remains weak upon the addition of the RuGN to Fe(VI), suggesting that ·OH and ·O2− are not the predominant active species in the reaction (Supplementary Fig. 16a, b). The replacement of H2O by 50% D2O (that can improve performance in 1O2-dominated system5) in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system resulted in similar CIP degradation rates (Fig. 2f), and the 1:1:1 triplet signal of 2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinol-1O2 can be barely observed (Supplementary Fig. 16c), indicating 1O2 did not contribute to the degradation significantly.

The introduction of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a known quencher of reactive high-valent metal intermediates such as Fe(IV), Fe(V) and Ru(V)46, dramatically inhibited the CIP degradation with kobs decreased from 0.935 min−1 (without quencher) to 0.091 min−1 in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system (Supplementary Fig. 18). These phenomena demonstrate that reactive high-valent metal intermediates including Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) make a significant contribution to the degradation of CIP, rather than ·OH, ·O2−, and 1O2.

Selective generation of active high-valent metal species

We investigated the oxidation contribution of reactive high-valent metal intermediates (including Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V)) using methyl phenyl sulfoxide (PMSO) as a probe. PMSO was selected due to its exclusive conversion to methyl phenyl sulfone (PMSO2) by reactive Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) through the oxygen-atom transfer (OAT) process47, while the PMSO2 production via the reaction of Fe(VI) and ROS with PMSO was found to be negligible. The conversion of PMSO to PMSO2 () in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system is ~100% at the initial concentration of PMSO used, ranging from 50 to 500 μM (Supplementary Fig. 19), suggesting the dominant role of reactive high-valent metal intermediates (Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V)), rather than ROS, in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system. The generation of Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) was also confirmed by the production of PMS16O18O (m/z = 156.9504) in isotope-labeling experiments using H218O as the solvent (Fig. 2g). It should be noted that due to the self-decay of Fe(VI) producing small amounts of Fe(IV)/Fe(V), a concentration of 10 μM PMSO2 was generated in the Fe(VI) alone system, whereas the RuGN/Fe(VI) system enabled 30 μM PMSO2 production (Supplementary Fig. 20). The result suggests that RuGN facilitates the selective conversion of Fe(VI) to Fe(IV)/Fe(V).

Moreover, the cumulative concentrations of ·OH and ·O2− are much lower than those of Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) (Supplementary Fig. 21), confirming the selective generation of Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V). In comparison to the RuC3N4/Fe(VI), PtGN/Fe(VI), CoGN/Fe(VI), and FeGN/Fe(VI) systems, the RuGN/Fe(VI) system exhibits the highest yield of Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 22). The relative contribution of Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) to the overall catalytic activity in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system was calculated to be 90% (Fig. 2i)48, and this value is higher than that in other MGN/Fe(VI) system (Supplementary Fig. 23), which suggests that Ru sites are more efficient for selective generation of reactive high-valent metal intermediate species during the Fe(VI) activation process.

To further confirm the generation of Fe(IV)/Fe(V) in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system, in situ Raman spectroscopy was conducted. Specifically, RuGN exhibits two characteristic signals at 1348 and 1588 cm−1, corresponding to defect- (D-) and graphitic- (G-) bands of GN substrate (Fig. 3a). The only broad signal at 1060 cm−1 in the Raman spectroscopy of Fe(VI) corresponds to Fe-O vibrations49. Upon the introduction of Fe(VI) into the RuGN catalyst, new signals at 1042, 917, and 842 cm−1 can be observed in the Raman spectra, which are attributed to the formation of RuGN-Fe(VI)*, Fe(V), and Fe(IV), respectively17,39,50. In contrast, none of these signals were observed in the Fe(VI) alone system (Supplementary Fig. 24), indicating the efficient generation of Fe(IV)/Fe(V) in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system. As the reaction proceeds, the signals corresponding to the RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex, Fe (V), and Fe(IV) gradually decrease, while the Fe(III) signals (at 483 and 617 cm−1) remain obvious49. These results demonstrate that Fe(VI) reacts with the RuGN to form Fe(IV)/Fe(V), which is eventually converted into Fe(III). Consistently, 30 μM of Fe(VI) was completely activated by RuGN, while only 2 μM of Fe(VI) decomposed in the Fe(VI) alone system within 7 min (Supplementary Fig. 25).

Fig. 3. Mechanistic insights into the degradation of CIP in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system.

a In situ Raman spectra obtained from the RuGN/Fe(VI), RuGN, and Fe(VI) systems. b The corresponding Koutecky-Levich plot of rotating RuGN film disc electrode in the Fe(VI)-containing Na2SO4 electrolyte. Influence of the RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex on the reaction stoichiometries for the reactions between Fe(VI) and c ABTS, d As(III), and e the formation of H2O2 in the Fe(VI) and RuGN/Fe(VI) systems in the presence of ABTS or As(III) probe. f Adsorption kinetics and isotherms recorded for the CIP and Fe(VI) onto RuGN, RuC3N4, GN, and g-C3N4, respectively. g Open-circuit potential curves obtained on the RuGN electrode in different systems. h Fitting of the linear relationship between the oxygen reduction potential of SACs and the degradation efficiency of CIP. i Chronopotentiometry curves tested for the RuGN-coated electrode and blank electrode. Error bars represent the standard deviation and are calculated based on three independent experiments.

The presence of Fe(V) indicates that the specific one-electron transfer process to produce RuIV=O/Fe(V) occurs in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system. By using the differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) analysis51, we further reveal the generation of RuIV=O intermediate in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system (Supplementary Fig. 26), which shows reactivity towards CIP and other organic pollutants (Supplementary Fig. 27). For quantitative determination the valence of final high-valent Ru species, we further conducted the rotating ring-disc electrode (RRDE) experiment to reveal the electron number transferred from RuGN to Fe(VI) (Supplementary Fig. 28). Based on the Koutechy–Levich equation, the electron transfer number was calculated to be 2.06 according to the fitted K-L slope value of 4.63 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 29), which demonstrates that an overall two-electron transfer process occurs from the RuIIIGN to Fe(VI) to produce RuV=O species as a final product, which also contain oxidative capability for degrading various organic pollutants42,52. After the reaction of high-valent Ru species and organic pollutants, the high-valent Ru species can be reduced to RuIII53. This process can thereby maintain the stability of the RuIIIGN. These results confirm that the interaction between RuGN and Fe(VI) can produce RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex and subsequently generate high-valent reactive intermediates, including Fe(IV), Fe(V), and Ru(V).

The selective Fe(VI) activation to produce Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) is expected to increase the utilization rate of Fe(VI) by reducing the side reaction between Fe(VI) and H2O to produce H2O2 that can even quench reactive Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) in reaction system10,13. The effects of RuGN on the production of Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system were investigated by using 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS) and AsIII (H3AsO3) as probes (Fig. 3c, d)11,54. The ABTS can only be oxidized to ABTS* via a one-electron transfer process, and the reaction stoichiometry of [Fe(VI)]:[ABTS*] was 1:1.17 in the Fe(VI)/ABTS system with 10 mM borate buffer (Fig. 3c), suggesting that 100% of Fe(VI) and 17% of produced Fe(IV)/Fe(V) participate in ABTS oxidation54. In contrast, the presence of RuGN/Fe(VI) notably changes the stoichiometry of Fe(VI) and ABTS* to 1:1.79 and significantly reduces the production of H2O2 (Fig. 3c, e). It is suggested that RuGN-Fe(VI)* acts as a more effective electron acceptor from ABTS, thereby promoting the formation of the reactive high-valent intermediates, including Fe(V), Fe(IV), and Ru(V) via e− transfer process (Eqs. S8–10).

Fe(VI)/Fe(IV)/Ru(V) react with As(III) to generate the Fe(IV)/Fe(II)/Ru(III), and As(V) (as HAsO2−) through a two-electron transfer process. In the RuGN/Fe(VI)/As(III) system, the reaction stoichiometry ratio of [produced As(V)] to [Fe(VI)] is approximately 1.37:1, which is higher than that in the Fe(VI)/As(III) system (1.13:1) (Fig. 3d). Meanwhile, the yield of H2O2 decreased in the RuGN/Fe(VI)/As(III) system (Fig. 3e). These findings confirm that the RuGN can enhance the surface electrons transfer and increase the utilization efficiency of the Fe(IV) intermediate via 2e− transfer process (Eqs. S11–14). Note that H2O2 by-product that is generated by the self-decay of Fe(VI) can quench Fe(IV)/Fe(V) and decrease its utilization15. Interestingly, RuGN can react with the H2O2 to produce reactive ·O2− for CIP degradation (Supplementary Fig. 30). Thus, RuGN not only suppresses the generation of H2O2, but it also eliminates H2O2 in the Fe(VI) based system (Eqs. S15, 16), preventing the subsequent quenching of reactive high-valent intermediates by H2O2, thereby enhancing the overall utilization rate of Fe(VI) (Supplementary Fig. 31).

RuGN mediated efficient electron transfer process

Electron transfer process among organic pollutants, metal sites, and Fe(VI) is crucial for Fe(VI) activation and subsequent pollutant degradation. Owing to the strong π–π interaction with organic pollutants (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 32 and Supplementary Table 7) and efficient electron conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 33), GN rather than g-C3N4 is a preferred support for metal sites. Moreover, RuGN exhibited larger electron density in LSV analysis and a smaller Nyquist arc radius in EIS spectrum than other MGN (PtGN, CoGN, FeGN), regardless of the presence of Fe(VI) (Supplementary Fig. 34), indicating that Ru reactive sites can decrease the charge transfer resistance and improve the interfacial reaction kinetics45. Consistently, ESR analysis indicates that RuGN can serve as the most efficient electron donor to reduce 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl to non-paramagnetic substances among all other SACs prepared in this study (Supplementary Fig. 35)55, which may facilitate the coordination and activation of Fe(VI).

When Fe(VI) is introduced into the RuGN, a higher open-circuit potential (OCP, 0.313 V) than that in the Fe(VI) alone system (0.153 V) can be observed (Fig. 3g). This increased OCP value could be attributed to the generation of RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex with higher oxidation potential compared to Fe(VI) alone, which was consistent with the in situ Raman spectra. Note that the OCP values of different MGN/Fe(VI) system were found to be positively correlated with their catalytic CIP degradation performance (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 36), suggesting that a higher oxidation potential of intermediates in the MGN/Fe(VI) system is advantageous for the degradation of CIP.

During the subsequent Fe(VI) activation process, a notable negative current occurred after the introduction of Fe(VI) into the RuGN system (Fig. 3i), indicating fast electron transfer from the RuGN to Fe(VI) to form Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V). The subsequently introduced CIP first accelerated the electron transfer process of RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex to generate Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) and then provided electrons to Ru(V) that was generated on the RuGN electrode, leading to the rebounding signal for the transient current curve48. Meanwhile, the open-circuit potential of the RuGN-Fe(VI)* decreased to 0.175 V after the addition of CIP (Fig. 3g), which proves that CIP can supply electrons to RuGN-Fe(VI)* and its products (i.e., Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V)) and be subsequently oxidized. Similarly, larger LSV current of the RuGN electrode can be observed after the addition of CIP, confirming increased electron density of the RuGN driven by the electron transfer from CIP (Supplementary Fig. 37). To further confirm the CIP oxidation via electron transfer process, galvanic oxidation process (GOP) was further conducted in a two-compartment cell (Supplementary Fig. 38). A current was detected after the addition of Fe(VI) into the compartment that contains the RuGN electrode, while no obvious signal was observed in the control Fe(VI) or GN/Fe(VI) system (Supplementary Fig. 39). The result confirmed the electron transfer process from CIP to RuGN-Fe(VI)* and its intermediate products (i.e. Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V)) driven by due to the electric potential difference between two separated electrodes. Overall, due to the transfer of 2.06 e− from RuGN to Fe(VI) within RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex, Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) can be selectively produced to accept electrons from CIP for efficient CIP degradation in RuGN/Fe(VI) system (Supplementary Fig. 40).

Moderate interaction facilitates Fe(VI) activation

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to elucidate the catalytic mechanism, specifically examining how the electronic structure of the catalytic metal center dictates the activation of Fe(VI) at the atomic level (Supplementary Fig. 41). According to the Sabatier principle, an optimal catalyst’s catalytic center should have a moderate binding strength to obtain reactive high-valent intermediates56. Thus, the balanced strength is crucial for ensuring efficient adsorption and desorption of reactive high-valent metal intermediates. Metal (Ru, Pt, Co, and Fe)-O4 sites were constructed on a GN support, and Fe(VI) adsorption states were analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 42). Metal single atom furnishing GN exhibits significantly lower adsorption energy (from −3 to −4 eV) towards Fe(VI) molecules compared to the GN support itself (−1.1 eV) (Fig. 4a), indicating that the metal sites of MGN exhibit a stronger affinity with Fe(VI) than the carbon atoms of GN. The integrated projected crystal orbital Hamilton population (−IpCOHP) analysis confirms that the interaction between metal centers and O of adsorbed Fe(VI) (>4.0) is much stronger than that between carbon atoms of GN and O of adsorbed Fe(VI) (0.27) (Fig. 4b). Among these four SACs, the values of −IpCOHP follow the trend of FeGN > CoGN > PtGN > RuGN, which suggests that compared with other SACs, RuGN contains a lower interaction with Fe(VI). The result is also confirmed by the d-band centers of MGN with the presence of Fe(VI) (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 43). Therefore, the typical volcano-type correlations of −IpCOHP/catalytic activity and d-band centers/catalytic activity were observed (Fig. 4d), which indicates that the moderate interaction between the metal centers and Fe(VI) contributes to the highest catalytic activity of RuGN.

Fig. 4. Theoretical investigations on the RuGN/Fe(VI) catalytic activity.

a The adsorption energies between different catalysts and Fe(VI), and the bond lengths of Fe-O in Fe(VI). b pCOHP and −IpCOHPs of Fe(VI) adsorbed on the surfaces of SACs and graphene. c PDOS of Ru, Pt, Co, and Fe d orbitals in SACs and SACs-Fe(VI) systems. d Correlation between the d-band center and CIP removal rate, and −IpCOHP and CIP removal rate of different catalysts. e Bader charge analysis of different catalysts with the adsorption of Fe(VI). f The PDOS of O 2p and RuGN 4d states of RuGN and RuGN/Fe(VI), and the integrated overlapping area is labeled in the top left. g Electronic density difference (pink and yellow regions represent the increase and decrease of electron density, respectively) and adsorption energy of different catalysts.

To further reveal the impacts of interaction between catalysts and the Fe(VI) species on the Fe(VI) activation, the length of the Fe-O bond was determined in different systems. Strong bonding of metal sites of MGN and O in Fe(VI) leads to excessive elongation of the Fe-O bond (IFe-O) in Fe(VI), following the trend of FeGN > CoGN ≈ PtGN > RuGN (Fig. 4a). This excessive elongation would result in the sluggish electron transfer from metal sites to Fe via M-O-Fe coordination. According to Bader charge analysis, the charge transfer from other metal sites are lower than that from Ru-O4 site with moderate interaction with Fe(VI) (1.15e−) (Fig. 4e). The increased overlap between the Ru 4d and O 2p orbitals (6.05 vs. 1.37, Fig. 4f) as well as high charge-density difference after Fe(VI) adsorption onto the surface further confirmed the efficient electron-transfer ability between RuGN and Fe(VI) (Fig. 4g). After Fe(VI) activation via electron transfer process, the downshift of the d-band center for Ru sites, moving away from the Fermi level (EF) upon Fe(VI) adsorption (Fig. 4c), result in the weaker interaction between Ru sites (after providing electrons) and reduction products of Fe(VI) (after accepting electrons), which facilitates the release of the produced Fe(IV)/Fe(V) species on the RuGN surface for the following pollutant degradation57. Overall, the RuGN exhibiting moderate interaction with Fe(VI), supported by the moderate −IpCOHP (4.56), d-band centers, can avoid the excessive elongation of the Fe-O bond with a small IFe-O value (1.59 Å). The moderate interaction between RuGN and Fe(VI) results in the formation of RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex, as indicated by characteristic peak at 1042 cm−1 in in situ Raman spectra (Fig. 3a) and elevated open-circuit potential value for RuGN/Fe(VI) system in the electrochemical experiment (Fig. 3g). Subsequently, efficient electron transfer through Ru-O-Fe coordination is facilitated for the effective generation of reactive Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) (Fig. 2h) to degrade pollutants in water (Fig. 2a).

Insights into CIP degradation process

Compared to that in Fe(VI) alone system, CIP degradation in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system produced fewer types of byproducts with lower concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 44), as measured by liquid chromatograph mass spectrometer (LC-MS) (Supplementary Tables 8 and9 and Supplementary Figs. 45 and 46). Post-degradation toxicity assessments, which include criteria such as the 48-h LC50 for Daphnia magna, developmental toxicity, mutagenicity, and the bioaccumulation factor, suggest that the byproducts, particularly those with low molecular weight, pose a lower environmental risk compared to the parent compound, CIP (Supplementary Figs. 47 and 48). Fukui functions index (f0) were further calculated to deeply analyze the accurate reactive sites on CIP molecules (Supplementary Fig. 49)58, which shows that N19, C15, and O6 are the major reactive sites with f− = 0.245, 0.082 and 0.077 (Supplementary Table 10) that are more susceptible to be attacked. Combined with DFT calculations and LC-MS analysis, four CIP degradation pathways in the RuGN/Fe(VI) system were proposed, including defluorination, hydroxylation, cleavage, and deamination reactions by Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) both in the RuGN/Fe(VI) and Fe(VI) systems (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 50). All byproducts can be further decomposed into CO2 and H2O with a high rate of total organic carbon (TOC) removal (55.1%) (Supplementary Fig. 51). The high TOC removal rate underscores the deep catalytic oxidation capacity of the RuGN/Fe(VI) system. Therefore, the RuGN/Fe(VI) not only effectively removed pollutants in water but also significantly reduced the environmental risks associated with the pollutant degradation.

Fig. 5. Evaluation of the practical application.

a Proposed degradation pathways for the CIP degradation driven by high-valent metal-oxygen species. b Practical cycling-pass continuous-flow reactor with flow-through and flow-by modes. c Pressure difference between the inlet and outlet measured by two separate pressure sensors, and d the CIP removal rates under different flow modes and velocities. e Expanded single-pass continuous-flow reactor with flow-by mode. f The CIP removal rates in the single-pass continuous-flow reactor. Error bars represent the standard deviation and are calculated based on three independent experiments.

Evaluation of practical water purification of RuGN/Fe(VI)

Further stability tests have demonstrated that the RuGN/Fe(VI) system maintained high activity over five consecutive reaction cycles (Supplementary Fig. 52). XRD analysis revealed that the structure integrity of RuGN was preserved after multiple uses. Additionally, a negligible amount of leached Ru ions (<0.075 μg L−1, 0.03%) has been detected from RuGN during the reaction process, confirming the robust stability of RuGN within the RuGN/Fe(VI) system.

The RuGN/Fe(VI) system exhibits satisfactory catalytic performance for degrading organic pollutants (Fig. 2). This success prompted us to pursue device integration of the catalyst for water purification. A water-purification membrane was fabricated by immobilizing RuGN onto a polyether sulfone membrane (1 cm × 1 cm) using Nafion ionomer as a binder (Supplementary Fig. 53). To sufficiently utilize the oxidation capacity of added Fe(VI) for efficient CIP degradation, we first placed this catalyst coated membrane in a cycling-pass continuous-flow reactor featuring a serpentine-type flowplate with the active area of 1 cm2 (Fig. 5b). In the cycling-pass reactor, we explored the impacts of two flow modes (i.e., flow-through and flow-by modes) and different flow velocities on the CIP removal performance, aiming to establish effective protocols for CIP treatment. The flow-through mode (the feedstock flowing through the membrane) was anticipated to provide better treatment efficiency due to improved catalyst-pollutant contact, albeit with a higher pressure drop (i.e., energy penalty). Conversely, the flow-by mode (the feedstock flowing by the membrane) was expected to have a lower pressure drop but slightly inferior treatment performance (Fig. 5c, d). As anticipated, under both tested flow velocities of 5 and 10 mL min−1, CIP degradation kinetics within 10 min were higher with the flow-through mode (0.11 and 0.17 min−1, respectively) compared to that with the flow-by mode (0.03 and 0.08 min−1, respectively) (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 54). However, the pressure difference between the inlet and outlet significantly increased when wastewater flowed through the RuGN membrane (33.3 Kpa, 10 mL min−1) (Fig. 5c). Note that too excessive pressure difference would result in high energy consumption, while water flows perpendicularly through the membrane would easily result in membrane clogging, which limit its practical applications. Owing to the satisfying CIP degradation kinetics (0.08 min−1) with a flow rate of 10 mL min−1, the flow-by mode emerged as a favorable option for water treatment in the continuous-flow reactor.

To achieve successive CIP degradation in water, we further employ a larger single-pass continuous-flow reactor which contains a water-purification membrane fabricated by immobilizing RuGN onto an expanded polyether sulfone membrane (100 cm2) (Supplementary Fig. 55). During the treatment process (details in Supplementary Table 11), the mixture of Fe(VI) and CIP flow by the RuGN membrane in the single-pass reactor (Fig. 5e). Notably, over 91% of CIP can be consistently degraded by RuGN/Fe(VI) system in the single-pass continuous-flow reactor throughout the entire 12-h reaction process (Fig. 5f). The total iron concentrations in the inlet (Cup A) and outlet (Cup B) were determined by Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) to be ~1.6 mg L−1 (~30 μM Fe(VI)), respectively. These results confirm that the amount of iron remaining on the catalyst membrane is negligible, indicating no membrane clogging. The overall degradation process demonstrates outstanding stability of RuGN and high catalytic performance for CIP removal. These findings indicate that owing to the excellent stability of RuGN, the RuGN/Fe(VI) combined with a single-pass continuous-flow reactor system exhibits excellent feasibility and significant practical application potential for long-term removal of micropollutants from water.

Discussion

In summary, we synthesized a Ru SAC with electron-rich graphene support (RuGN) to selectively activate Fe(VI) to produce Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) for antibiotic degradation, especially achieving record-fast CIP degradation kinetics. Since Fe(VI) can preferentially react with RuGN rather than H2O, RuGN can mitigate Fe(VI) self-decay with H2O, thus decreasing the production of H2O2 that can quench Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V). Moreover, RuGN can even activate H2O2 in the reaction system to produce ·O2− for CIP degradation. Therefore, the utilization rate of Fe(VI) can be overall improved with RuGN. Compared with other typical transition metal SAC, RuGN contains moderate interaction with Fe(VI) to produce RuGN-Fe(VI)* complex, which can inhibit excessive elongation of Fe-O bond and facilitate the efficient electron transfer via Ru-O-Fe coordination. Selective Fe(VI) activation to produce Fe(IV)/Fe(V)/Ru(V) with an increased Fe(VI) utilization rate is thus achieved for CIP degradation. Moreover, the RuGN/Fe(VI) system resists the interference from water background substances and exhibits excellent degradation performance in real water samples. Ultimately, the RuGN catalyst was integrated into different continuous-flow reactors for practical CIP degradation, and achieved efficient CIP degradation (0.17 min−1 for cycling reactor and >91% removal rate for one-pass reactor within successive 12 h). This work provides a rational strategy for improving the utilization rate of Fe(VI) during Fe(VI) activation via regulating the interaction between the metal site and Fe(VI), which is promising to address deep wastewater purification.

Methods

Catalyst preparation

For the synthesis of the RuGN SAC catalyst furnished with GN supports, 50 mg of GN powder was well dispersed in triethanolamine solution (100 mL, 10%, v/v), followed by the addition of RuCl3 precursor (0.5 mL, 500 mg L−l). After overnight stirring, the as-prepared sample was washed several times with deionized water and ethanol, dried in an oven at 60 °C, and then annealed at 450 °C for 2 h under a nitrogen atmosphere to obtain Ru single atom loaded graphene (RuGN). PtGN, CoGN, and FeGN were fabricated following a similar protocol with the substitution of RuCl3 by HPtCl6, Co(acac)2, and Fe(OAc)2, respectively. For the synthesis of RuC3N4, 50 mg C3N4 powder was well dispersed in triethanolamine solution (100 mL, 10%, v/v). Ru was loaded onto the surface of C3N4 as a cocatalyst using an in situ photo-deposition method with a RuCl3 precursor (0.5 mL, 500 mg L−l) for 30 min. The as-prepared sample was washed with deionized water and ethanol several times, dried in an oven at 60 °C, and finally annealed at 450 °C for 2 h under a nitrogen atmosphere to obtain Ru single atom loaded C3N4 (RuC3N4).

Catalyst characterization

PXRD (D8 ADVANCE, Bruker, Germany), XPS (ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher, USA), SEM (S-4800, HITACHI, Japan), Raman (DXRxi, Thermo Fisher, USA), HAADF-STEM (Themis Z, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and XAS (spring 8, Japan Synchrotron Radiation Facility) were employed to reveal the chemical and structural properties of SACs. ESR analysis (Bruker EMX, Bruker, Switzerland), UV-vis DRS (UV3600PLUS, Shimadzu, Japan), EIS (CHI760E, Chenhua, China), and Zeta analysis (Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, UK) were performed to investigate the reaction mechanisms of the RuGN/Fe(VI) system.

Pollutant degradation experiments

Pollutant degradation experiments were conducted in a 100 mL beaker at 25 ± 2 °C under magnetic stirring. In a typical CIP degradation experiment, a certain mass of RuGN was added to the CIP solution with an initial concentration of 10 µM. To initiate the catalytic degradation reaction, a certain amount of Fe(VI) was added (with the final Fe(VI) concentration of 30 μM). At given time intervals, 1 mL of sample was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane, followed by the addition of Na2S2O3 to quench the residual Fe(VI). The concentration of CIP is determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent U3000).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2022YFC3201801 to Z.L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 41171005 to Z.L.), and the general program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 22478008 to Z.B.Z.).

Author contributions

Z.B.Z. and Z.L. supervised the project. Z.B.Z., Z.L., and Y.C. conceived the study and designed experiments. Y.C. and X.G. performed the experiments and data curation, and Z.B.Z., Y.C., and J.L. performed the formal analysis, made figures, and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript writing.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chuanyi Wang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zishuai Bill Zhang, Email: zszhang@pku.edu.cn.

Zhenshan Li, Email: lizhenshan@pku.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-62930-4.

References

- 1.Wong, F. et al. Discovery of a structural class of antibiotics with explainable deep learning. Nature626, 177–185 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu, K. J. Y. et al. An antibiotic preorganized for ribosomal binding overcomes antimicrobial resistance. Science383, 721–726 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang, S., Zheng, H. & Tratnyek, P. G. Advanced redox processes for sustainable water treatment. Nat. Water1, 666–681 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu, F. et al. Rapid self-heating synthesis of Fe-based nanomaterial catalyst for advanced oxidation. Nat. Commun.14, 4975 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu, Q.-Y., Yang, Z.-W., Wang, Z.-W. & Wang, W.-L. Oxygen doping of cobalt-single-atom coordination enhances peroxymonosulfate activation and high-valent cobalt-oxo species formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA120, e2219923120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao, Y. et al. Selective degradation of electron-rich organic pollutants induced by CuO@biochar: the key role of outer-sphere interaction and singlet oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol.56, 10710–10720 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma, V. K. et al. Reactive high-valent iron intermediates in enhancing treatment of water by ferrate. Environ. Sci. Technol.56, 30–47 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, X. et al. CoN1O2 single-atom catalyst for efficient peroxymonosulfate activation and selective cobalt(IV)=O generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202303267 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antolini, C. et al. Photochemical and photophysical dynamics of the aqueous ferrate(VI) ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 22514–22527 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu, J. et al. Overlooked role of Fe(IV) and Fe(V) in organic contaminant oxidation by Fe(VI). Environ. Sci. Technol.54, 9702–9710 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao, B. et al. Iron(III)-(1,10-phenanthroline) complex can enhance ferrate(VI) and ferrate(V) oxidation of organic contaminants via mediating electron transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 17144–17153 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang, Z.-Y. et al. Dry chemistry of ferrate(VI): a solvent-free mechanochemical way for versatile green oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 10949–10953 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, Z. et al. How should we activate ferrate(VI)? Fe(IV) and Fe(V) tell different stories about fluoroquinolone transformation and toxicity changes. Environ. Sci. Technol.58, 4812–4823 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, X. et al. Enhanced removal of phenolic compounds by ferrate(VI): unveiling the Bi(III)-Bi(V) valence cycle with in situ formed bismuth hydroxide as catalyst. Water Res.248, 120827 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao, B., Dong, H., Sun, B. & Guan, X. Role of ferrate(IV) and ferrate(V) in activating ferrate(VI) by calcium sulfite for enhanced oxidation of organic contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol.53, 894–902 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu, Y. et al. Oxidation of emerging contaminants by S(IV) activated ferrate: identification of reactive species. Water Res.251, 121100 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu, Y. et al. Enhanced oxidation of organic compounds by the ferrihydrite-ferrate system: the role of intramolecular electron transfer and intermediate iron species. Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 16662–16672 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian, B. et al. Promoting effect of silver oxide nanoparticles on the oxidation of Bisphenol B by Ferrate(VI). Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 15715–15724 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem.3, 634–641 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han, L. et al. A single-atom library for guided monometallic and concentration-complex multimetallic designs. Nat. Mater.21, 681–688 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu, L. et al. Ferrate(VI)/periodate system: synergistic and rapid oxidation of micropollutants via periodate/iodate-modulated Fe(IV)/Fe(V) intermediates. Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 7051–7062 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu, H. et al. Engineering ZrO2-Ru interface to boost Fischer-Tropsch synthesis to olefins. Nat. Commun.15, 5143 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou, Y. et al. Peripheral-nitrogen effects on the Ru1 centre for highly efficient propane dehydrogenation. Nat. Catal.5, 1145–1156 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia, W. et al. Defect-rich graphene nanomesh produced by thermal exfoliation of metal-organic frameworks for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 13354–13359 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, X. & Zhang, L. Green and facile production of high-quality graphene from graphite by the combination of hydroxyl radicals and electrical exfoliation in different electrolyte systems. RSC Adv.9, 3693–3703 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei, S. et al. Self-carbon-thermal-reduction strategy for boosting the Fenton-like activity of single Fe-N4 sites by carbon-defect engineering. Nat. Commun.14, 7549 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng, L. et al. Valence oscillation of Ru active sites for efficient and robust acidic water oxidation. Adv. Mater.35, 2305939 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, P. et al. Boosting oxygen evolution of single-atomic ruthenium through electronic coupling with cobalt-iron layered double hydroxides. Nat. Commun.10, 1711 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, C. et al. Single-atomic ruthenium catalytic sites on nitrogen-doped graphene for oxygen reduction reaction in acidic medium. ACS Nano11, 6930–6941 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang, Y. et al. O-, N-atoms-coordinated Mn cofactors within a graphene framework as bioinspired oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalysts. Adv. Mater.30, 1801732 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu, D. et al. Electronic structure modulation of iron sites with fluorine coordination enables ultra-effective H2O2 activation. Nat. Commun.15, 2241 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, X. et al. Nanoconfinement-triggered oligomerization pathway for efficient removal of phenolic pollutants via a Fenton-like reaction. Nat. Commun.15, 917 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, T. et al. Water decontamination via nonradical process by nanoconfined Fenton-like catalysts. Nat. Commun.14, 2881 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang, T. et al. Comparative study on ferrate oxidation of BPS and BPAF: kinetics, reaction mechanism, and the improvement on their biodegradability. Water Res.148, 115–125 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian, B. et al. Ferrate(VI) oxidation of bisphenol E-Kinetics, removal performance, and dihydroxylation mechanism. Water Res.210, 118025 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, H. et al. Enhanced ferrate(VI)) oxidation of sulfamethoxazole in water by CaO2: the role of Fe(IV) and Fe(V). J. Hazard. Mater.425, 128045 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dang, Q. et al. Bias-free driven ion assisted photoelectrochemical system for sustainable wastewater treatment. Nat. Commun.14, 8413 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, J. et al. Peracetic acid enhances micropollutant degradation by Ferrate(VI) through promotion of electron transfer efficiency. Environ. Sci. Technol.56, 11683–11693 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo, M. et al. Efficient activation of ferrate(VI) by colloid manganese dioxide: comprehensive elucidation of the surface-promoted mechanism. Water Res.215, 118243 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, D. et al. Comprehending the practical implementation of permanganate and ferrate for water remediation in complex water matrices. J. Hazard. Mater.462, 132659 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo, M. et al. Insights into the role of in-situ and ex-situ hydrogen peroxide for enhanced ferrate(VI) towards oxidation of organic contaminants. Water Res.203, 117548 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li, R. et al. Peracetic acid-ruthenium(III) oxidation process for the degradation of micropollutants in water. Environ. Sci. Technol.55, 9150–9160 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang, J. et al. Activation of periodate by self-recycled Ru(III)/TiO2 for selective oxidation of aqueous organic pollutants: essential role of homogeneous Ru(V)=O species. Chem. Eng. J.473, 145012 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 44.McBeath, S. T., Zhang, Y. & Hoffmann, M. R. Novel synthesis pathways for highly oxidative iron species: generation, stability, and treatment applications of ferrate(IV/V/VI). Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 18700–18709 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, D. et al. Dynamic active-site induced by host-guest interactions boost the Fenton-like reaction for organic wastewater treatment. Nat. Commun.14, 3538 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang, T. et al. UVA-LED-assisted activation of the ferrate(VI) process for enhanced micropollutant degradation: important role of ferrate(IV) and ferrate(V). Environ. Sci. Technol.56, 1221–1232 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo, J. et al. Fenton-like activity and pathway modulation via single-atom sites and pollutants comediates the electron transfer process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA121, e2313387121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo, Z.-Y. et al. Crystallinity engineering for overcoming the activity-stability tradeoff of spinel oxide in Fenton-like catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA120, e2220608120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sitter, A. J., Reczek, C. M. & Terner, J. Heme-linked ionization of horseradish peroxidase compound II monitored by the resonance raman Fe(IV)=O stretching vibration. J. Biol. Chem.260, 7515–7522 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, M. et al. Highly selective synthesis of surface FeIV=O with nanoscale zero-valent iron and chlorite for efficient oxygen transfer reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA120, e2304562120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sathiyan, K. et al. Revisiting the electron transfer mechanisms in Ru(III)-mediated advanced oxidation processes with peroxyacids and ferrate(VI). Environ. Sci. Technol.58, 11822–11832 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, S. et al. Ruthenium-driven catalysis for sustainable water decontamination: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett.21, 3377–3391 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li, D. et al. Ru(III)-periodate for high performance and selective degradation of aqueous organic pollutants: important role of Ru(V) and Ru(IV). Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 12094–12104 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang, Z.-S. et al. Impact of phosphate on ferrate oxidation of organic compounds: an underestimated oxidant. Environ. Sci. Technol.52, 13897–13907 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu, F. et al. Periodate activation by pyrite for the disinfection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria: performance and mechanisms. Water Res.230, 119508 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen, Z. W. et al. Unusual Sabatier principle on high entropy alloy catalysts for hydrogen evolution reactions. Nat. Commun.15, 359 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greiner, M. T. et al. Free-atom-like d states in single-atom alloy catalysts. Nat. Chem.10, 1008–1015 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou, Q. et al. Generating dual-active species by triple-atom sites through peroxymonosulfate activation for treating micropollutants in complex water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA120, e2300085120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.