Abstract

A major challenge in effective cancer treatment is the variability of drug responses among patients. Patient-derived organoids greatly preserve the genetic and histological characteristics even the drug sensitivities of primary tumor tissues, therefore provide a compelling approach to predict clinical outcome. However, the individual organoid culture and following drug response test are time and cost-consuming, which hinders the potential clinical application. Here, we developed PharmaFormer, a clinical drug response prediction model based on custom Transformer architecture and transfer learning. PharmaFormer was initially pre-trained with the abundant gene expression and drug sensitivity data of 2D cell lines, and was then finalized through a model further fine-tuned with the limited organoid pharmacogenomic data accumulated at the present stage. Our results demonstrate that PharmaFormer, integrating both pan-cancer cell lines and organoids of a specific type of tumor, provides a dramatically improved accurate prediction of clinical drug response. This study highlights that advanced AI models combined with biomimetic organoid models will accelerate precision medicine and future drug development.

Subject terms: Cancer, Predictive markers

Introduction

Drug response variability among cancer patients remains a critical challenge in clinical oncology1–4. Despite recent advances in tumor biomarker discovery and precision medicine5, the overall response rates for both chemotherapy and targeted therapy remain suboptimal. A meta-analysis6 of 570 phase II single-drug clinical trials, encompassing 32,149 patients, reported a median response rate of 11.9% for chemotherapy, while personalized target therapy achieved a slightly higher response rate of 30%.

Traditional treatment strategies rely on clinical intuition and limited biomarkers. Recently, there has been growing interest in employing artificial intelligence (AI) to systematically predict drug responses from comprehensive genomic data, thus enhancing clinical decision-making. Personalized treatment has shown the potential to significantly improve cancer treatment outcomes7. Large-scale tumor cell line screening efforts, such as the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC)8,9 and the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP)10, have tested over 1000 human cancer cell lines with hundreds of anticancer drugs, generating extensive parallel drug response data. These datasets have promoted the development of various drug response prediction algorithms11–14. However, traditional 2D cell lines often fail to recapitulate the complexity of tumor microenvironments, restricting their predictive efficacy for clinical drug responses.

Patient-derived tumor organoids stably retain the genomic mutations and gene expression profiles, together with multiple cell populations and three-dimensional morphology of tumor tissues. These organoids have emerged as a promising model for reflecting clinical responses to cancer therapies15. Numerous studies have confirmed that organoids can guide treatment decisions in cancers such as colon16,17, bladder18, pancreatic19, and liver cancer20, marking a new frontier for precision medicine. Despite their potential, the clinical implementation of organoids is hindered by challenges such as high costs, low establishment success rates in organoid culture, and extensive drug testing periods21,22. These limitations have motivated the development of computational algorithms to predict drug sensitivity based on organoid data. Furthermore, organoids, as a relatively novel research model, suffer from an additional challenge: the pharmacogenomic data available for organoids is currently insufficient to meet the large data requirements of deep learning models. To overcome this, integrating the extensive pharmacogenomic data from traditional 2D cell lines with the biomimetic advantages of organoids presents a strategic solution to build accurate and scalable predictive models for clinical drug responses.

Recently, several foundational models based on Transformer architectures, such as scGPT23, AlphaFold24, and GeneFormer25, have shown that transfer learning can mitigate the impact of limited training data by generalizing knowledge from large datasets and adapting it to specific tasks. Additionally, transfer learning has also been used to integrate bulk RNA-seq and single-cell sequencing data for drug response prediction26. Through this approach, we can fine-tune models pre-trained on extensive cell line drug response datasets with limited drug response data from tumor-specific organoids, thus facilitating drug response predictions.

In this study, we proposed PharmaFormer, a clinical drug response prediction model based on a custom Transformer architecture and a transfer learning strategy. PharmaFormer enhances drug response prediction in patients by incorporating organoid-specific pharmacogenomic data with large-scale cell line drug testing data. Furthermore, PharmaFormer showed a better performance in clinical drug response predictions of multiple molecules in three different tumor cohorts. This study demonstrates how transfer learning accelerates the application of tumor organoids in precision medicine and drug development.

Results

Overview of PharmaFormer

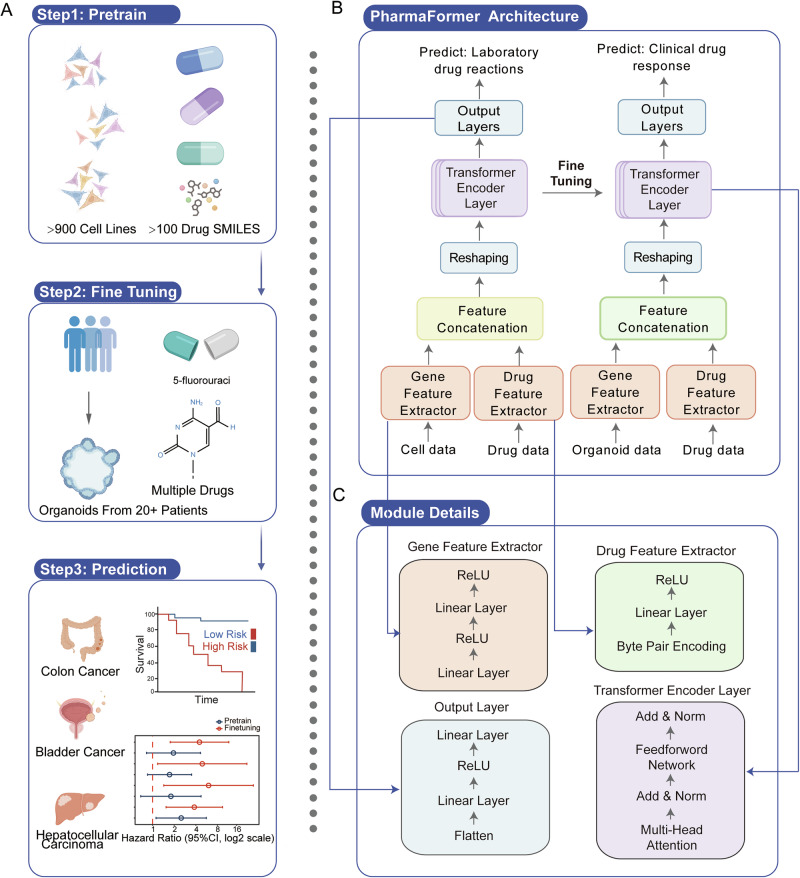

To predict clinical drug responses from bulk RNA-seq data of patient tumor tissues, we developed PharmaFormer, a drug response prediction model based on a custom Transformer architecture (see Methods for details). A key challenge in developing deep learning models for clinical drug response prediction lies in the limited availability of large-scale parallel drug response datasets. Although cell lines are widely used in preclinical models and provide extensive parallel drug response data, they are criticized for low biological fidelity27 and cross-contamination issues28. To address this, we implemented a transfer learning strategy that integrates pan-cancer cell line data and tumor-specific organoid data. PharmaFormer was constructed in three key stages (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Schematic of the PharmaFormer model.

PharmaFormer leverages large-scale parallel drug testing on cell lines combined with gene expression data to build a pre-trained model that is further fine-tuned with organoid-specific data for clinical drug response predictions. A Workflow of PharmaFormer. B The architecture of PharmaFormer includes a feature extractor that integrates cellular and drug structural data into a transformer encoder tailored for drug response prediction. C Detailed composition of each algorithmic module, highlighting its role in prediction accuracy.

Stage 1: Gene expression profiles of over 900 cell lines and area under the dose–response curve (AUC) of over 100 drugs were obtained from Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC, version 2)8. We developed a pre-trained model by integrate these gene expression matrices and each drug’s simplified molecular-input line entry system (SMILES)29 structure, to predict cell line responses using a 5-fold cross-validation approach.

Stage 2: We fine-tuned this pre-trained model using a small dataset of tumor-specific organoid drug response data, applying L2 regularization and other techniques to fully optimize model parameters to generate the final organoid-fine-tuned model.

Stage 3: The organoid-fine-tuned model was subsequently applied to predict clinical drug responses in specific tumor types. Gene expression profiles of tumor tissues, pharmaceutical therapy strategies, and overall survival of specific tumor cohorts were fetched from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA). Patients were scored with the organoid-fine-tuned model to be divided into high-risk and low-risk groups, and the prognosis was then compared using Kaplan–Meier plot and hazard ratios.

As shown in Fig. 1B, PharmaFormer processes cellular gene expression profiles and drug molecular structures separately using distinct feature extractors. After feature concatenation and reshaping, the data flows into a Transformer encoder consisting of three layers, each equipped with eight self-attention heads. The encoder subsequently outputs drug response predictions through a flattening layer, two linear layers, and a ReLU activation function. The gene feature extractor consists of two linear layers with a ReLU activation, while the drug feature extractor incorporates the Byte Pair Encoding, a linear layer, and a ReLU activation (Fig. 1C).

Performance benchmarking of PharmaFormer pre-trained models

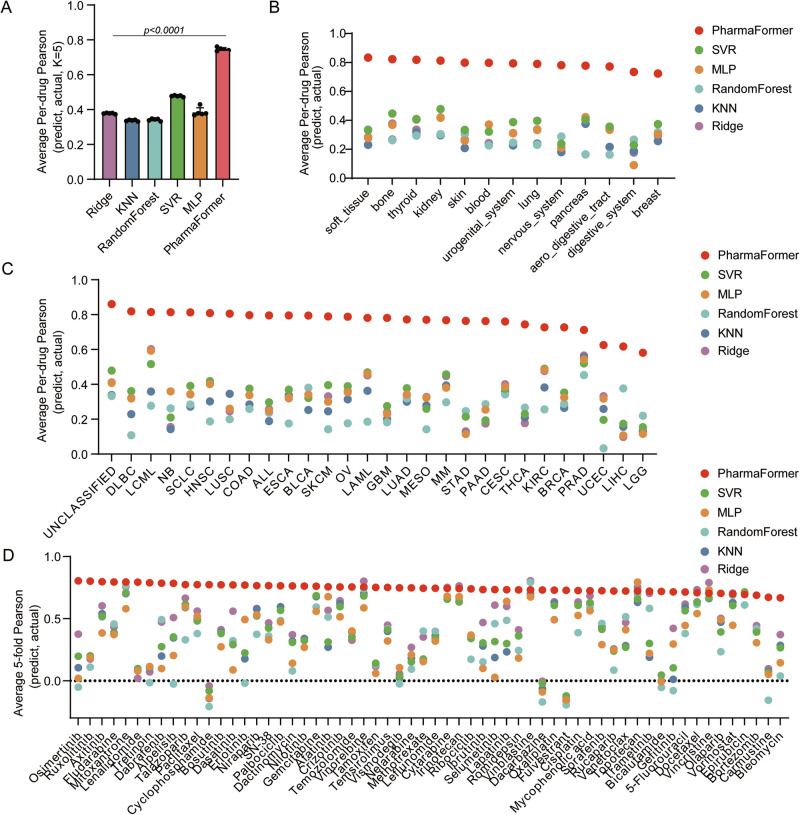

To establish the benchmark performance of the PharmaFormer pre-trained model during its initial training phase, we compared its performance against classical machine learning algorithms, including Support Vector Machines (SVR), Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP), Random Forests (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Ridge Regression (Ridge). For robust performance evaluation, we applied five-fold cross-validation and randomly divided the dataset into five non-overlapping subsets. For each fold, four subsets were used for training, and the remaining subset was used for testing. For each model, we calculated Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between predicted and actual responses for each drug individually across all cell lines.

As shown in Fig. 2A and Supplementary Data 1, the PharmaFormer pre-trained model outperformed with the highest Pearson correlation coefficient (0.742) compared to SVR (0.477), MLP (0.375), RF (0.342), Ridge (0.377), and KNN (0.388). These results underscore PharmaFormer’s superior predictive accuracy, probably attributed to its ability to capture complex interactions in gene expression and drug structure through its Transformer-based architecture.

Fig. 2. Comparative analysis of PharmaFormer pre-trained model versus classical machine learning models on cell line dataset.

A Five-fold validation of average per-drug Pearson correlation coefficients comparing PharmaFormer to classical machine learning models. B Performance comparison of PharmaFormer and classical machine learning models across various tissue types, represented by average per-drug Pearson correlation coefficients. C Average per-drug Pearson correlation coefficients of PharmaFormer versus those of classical machine learning models across each TCGA tumor category. D Pearson correlation coefficients of PharmaFormer and classical machine learning models across FDA-approved drugs.

Subsequently, we applied a stratified-cross-validation approach, retaining 20% of the target cells for prediction and using the remaining 80% for training. This method assessed model performance across various tissue types and TCGA tumor subgroups. To further dissect the model’s performance, we evaluated its predictive accuracy for each of the 60 FDA-approved drugs individually, with the results presented in Fig. 2D. We also found no significant difference in predictive performance when comparing targeted therapies against conventional chemotherapies, or between FDA-approved and non-FDA-approved drugs, highlighting the model’s consistent accuracy across diverse drug classes. Compared to other strategies (Fig. 2B–D), PharmaFormer consistently outperformed other models and demonstrated enhanced stability across most tissues, tumor types, and drugs, with similar results observed in Spearman correlation (Supplementary Fig. 1). Such consistency emphasizes the robustness and adaptability of PharmaFormer over classical models.

To provide an even more granular view of performance within the tumor types of primary interest in this study, we further analyzed the predictions for key therapeutic agents within colorectal and bladder cancer cell lines. In colorectal cancer, the correlations for 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin were 0.6012 and 0.6185, respectively. In bladder cancer, the correlations for cisplatin and gemcitabine were 0.6557 and 0.6275, respectively. In liver cancer, the correlations for Sorafenib were 0.9662. The detailed performance metrics for all drugs across all available tumor types are provided in the Supplementary Data 2.

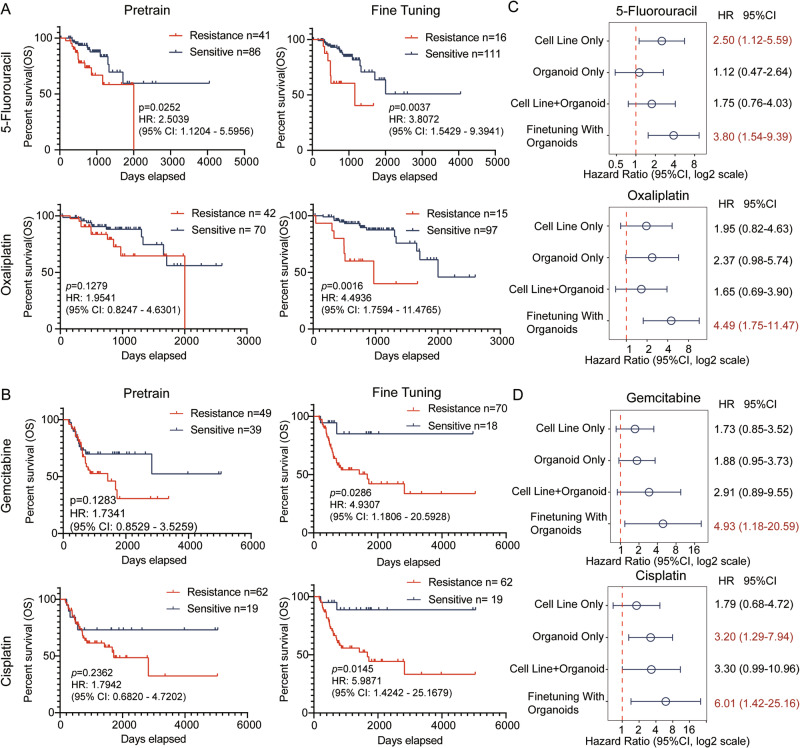

PharmaFormer enables accurate assessment of clinical drug response

To further evaluate PharmaFormer’s ability to predict drug responses in real-world clinical settings, we fine-tuned the pre-trained model using data from 29 patient-derived colon cancer organoids. We then applied both the pre-trained and fine-tuned models to predict drug response in bulk RNA-seq data from TCGA colon cancer patients. As 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin are the most commonly used compounds in colon cancer, these two molecules were prioritized for further investigation. Patients were categorized into drug-sensitive and drug-resistant groups according to their predicted response scores. As illustrated in Fig. 3A and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, the predictive performance of the organoid-fine-tuned model outperformed the pre-trained model for colon cancer patients. Specifically, hazard ratios for 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin improved from 2.5039 (95% CI: 1.1204–5.5956) and 1.9541 (95% CI: 0.8247–4.6301) to 3.9072 (95% CI: 1.5429–9.3941) and 4.4936 (95% CI: 1.7594–11.4765), respectively.

Fig. 3. Evaluation of PharmaFormer model in predicting drug response in colon cancer cohort and bladder cancer cohort.

A Kaplan–Meier survival curves for colon cancer patients receiving 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin treatment, comparing predictions from both the pre-trained and fine-tuned PharmaFormer models. B Kaplan–Meier survival curves for bladder cancer patients treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin, comparing predictions from PharmaFormer’s pre-trained and fine-tuned models. C Forest plot illustrating the effect of various training strategies on PharmaFormer’s predictive performance in colon cancer, including training with cell lines only, colon cancer organoids only, a combined dataset of cell lines and organoids, and a sequential training approach of cell lines followed by organoid fine-tuning. D Forest plot comparing PharmaFormer’s performance in bladder cancer under different training conditions: cell lines only, bladder cancer organoids only, combined cell lines and organoids, and sequential pre-training with cell lines followed by organoid fine-tuning. Statistical significance, hazard ratios, and confidence intervals were derived using the Cox proportional hazards model (CoxPHFitter) from the lifelines package.

A similar enhancement in predictive accuracy was observed for bladder cancer patients treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). In gemcitabine, the pre-trained hazard ratio was 1.7245 (95% CI: 0.8522–3.4895), while the fine-tuned hazard ratio increased to 4.9120 (95% CI: 1.1775–20.4892). In cisplatin, the pre-trained hazard ratio was 1.8004 (95% CI: 0.86861–4.7239), with the fine-tuned model achieving a hazard ratio of 6.0137 (95% CI: 1.4329–25.2391). Additionally, for hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib, the fine-tuned model significantly improved the differentiation of drug response (pre-trained hazard ratio: 1.3434, 95% CI: 0.3643–4.9531; fine-tuned hazard ratio: 5.6677, 95% CI: 1.4877–21.5923) (Supplementary Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 5).

To validate the efficiency of the proposed transfer learning strategy, we compared four training strategies: cell lines only, organoids only, a combined cell line-organoid dataset without transfer learning, and cell line pre-training followed by organoid fine-tuning. Results indicate that the organoid fine-tuning approach yielded the best predictive performance across all drugs tested (Fig. 3C, D and Supplementary Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that transfer learning can effectively integrate 2D cell line data with 3D organoid models, enhancing predictive accuracy in clinical drug response prediction.

To further validate our model’s generalizability, we evaluated the pre-trained and organoid-fine-tuned PharmaFormer models on four independent colorectal cancer cohorts treated with 5-fluorouracil30. We applied the models to predict the response for each patient and assessed their ability to classify patients according to their known treatment outcomes. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, the organoid-fine-tuned model consistently demonstrated a greater ability to distinguish between responsive and non-responsive patients across all four datasets compared to the model trained only on cell lines. This independent validation strongly supports our central claim that fine-tuning with patient-derived organoid data can generally enhance the model’s capability to identify patients who will benefit from a specific drug therapy.

Transfer learning with organoid data boosts prediction accuracy

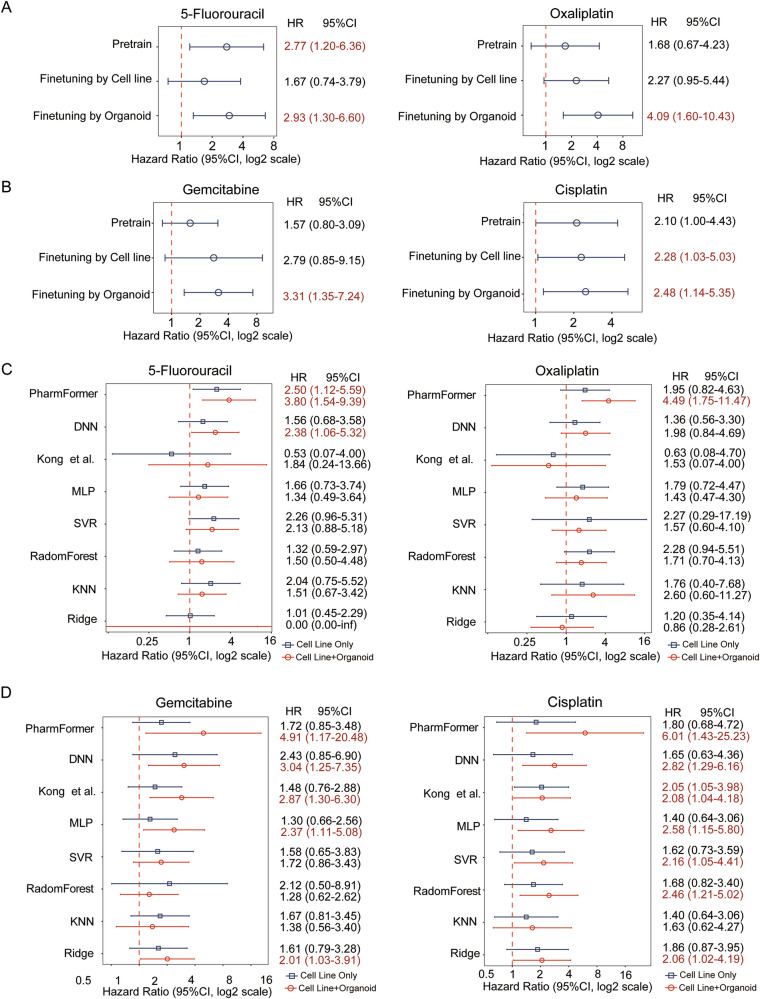

Although drug-parallel experiments using patient-derived organoids are considered to show higher accuracy than 2D cell lines in reflecting individual patient responses to treatment31, it remains uncertain whether the enhancement of the fine-tuned model is solely attributed to organoids. Therefore, we initiated another pre-trained model with drug response data in pan-cancer cell lines, excluding colon cancer cell lines, and then fine-tuned this model with data from either colon cancer cell lines or colon cancer organoids. The results revealed that the model fine-tuned with colon cancer cell lines was less predictive for clinical drug response to 5-fluorouracil. In contrast, the model fine-tuned with colon cancer organoids achieved the best predictive accuracy among all configurations (Fig. 4A). A similar trend was witnessed in bladder cancer, where models fine-tuned with bladder cancer organoids outperformed those fine-tuned with cell lines (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Performance evaluation of PharmaFormer with different fine-tuned dataset and canonical machine learning methods.

A, B Forest plots assessing the impact of the transfer learning approach on clinical drug response predictions, based on cell line and organoid data from matched tumor types (colon and bladder cancer). C, D Comparative clinical prediction performance of PharmaFormer against benchmark models for colon and bladder cancer. The analysis benchmarks PharmaFormer against classical machine learning algorithms, a biological network-based method, and a deep neural network (DNN). Forest plots display hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals, comparing models trained on cell lines only (blue) versus models pre-trained on cell lines and fine-tuned with organoid data (red). All metrics were computed using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Performance evaluation of PharmaFormer versus canonical machine learning methods

To comprehensively benchmark PharmaFormer’s clinical prediction performance, we compared it against a wide range of methods: five classical machine learning algorithms, a biological network-based model32, and a deep neural network (DNN) model. Several of these comparator models, such as SVR and the DNN, exhibited limited predictive ability in specific cases (e.g., for bladder cancer patients treated with cisplatin) and showed suboptimal performance overall. In contrast, PharmaFormer consistently demonstrated superiority in predicting clinical drug responses across a range of tumor types and drug classes. The Transformer-based architecture was specifically designed to leverage a transfer learning strategy, effectively capturing complex interactions between gene expression and drug structure. Such a design enabled a distinctively higher predictive accuracy than that of any other model. Moreover, the risk stratification coefficients generated by PharmaFormer were significantly higher than those of all other models (Fig. 4C, D and Supplementary Fig. 2C). This underscores its robust capability in predicting clinical outcomes for both first-line chemotherapies and multi-targeted agents across diverse tumor origins.

Discussion

PharmaFormer offers an innovative approach to predicting drug responses in cancer patients based on genome-wide expression profiles. By leveraging a Transformer encoder architecture, PharmaFormer establishes a robust relationship among transcriptomic data, drug structure, and clinical drug response. Our results demonstrate that PharmaFormer consistently outperforms classical algorithms, delivering superior predictive accuracy across multiple tumor types and first-line drugs.

In the high-risk field of drug development, the transition from preclinical research to clinical application is hindered by a high failure rate exceeding 90%33–35. Currently, organoids are widely used in the preclinical stage, particularly as alternatives to animal model for preclinical drug testing. This research indicates that transfer learning algorithms can leverage drug sensitivity results from organoids to predict therapeutic efficacy in patients, especially in predicting overall survival prognosis. This approach holds great potential for accelerating drug development and improving the success rate of new drug discoveries.

Recent advances in single-cell sequencing technology have facilitated the prediction of drug sensitivity29–31. However, PharmaFormer offers unique advantages: (1) compared to single-cell sequencing, bulk RNA-seq is significantly more affordable and accessible for routine clinical use; (2) extended development periods enable the accumulation of more bulk-seq data for larger models; and (3) drug sensitivity predictions based on single-cell sequencing often rely on indirect inference methods like knowledge graphs, which might introduce bias occasionally.

Preclinical models have an irreplaceable benefit in conducting parallel drug testing27,36, and recent studies have explored efficient ways to utilize pre-existing cell line drug sensitivity data. For instance, Failli et al. integrated pharmacogenomic knowledge from pan-cancer cell lines to identify therapeutic options for hepatoblastoma37, while Ma et al. applied a Few-shot learning strategy using MLP to transfer cell line pharmacogenomic data to patient-derived tumor xenografts (PDXs)38. Other advanced DNN-based models have also shown high predictive accuracy, though often by operating within a single data domain, such as predicting cell line response from cell line data or patient response from patient data39. Our work builds on these concepts, and our direct comparisons show that PharmaFormer’s Transformer-based transfer learning approach offers superior clinical prediction accuracy compared to not only classical algorithms but also other advanced strategies, including biological network-based and alternative deep neural network architectures. With advancements in patient-derived organoid libraries and Transformer-based algorithms, PharmaFormer extends the application of drug response prediction to the clinical patient level, thus taking a significant step forward.

Based on the promising results of PharmaFormer, we propose several directions for future development. First, while PharmaFormer currently builds its predictions solely on gene expression levels, incorporating additional genomic features, such as copy number variations and mutation profiles, could provide a more comprehensive view of cellular status. Second, future evaluations across a wider range of tumor types are needed since the current study is limited due to the size of the available organoid biobank and patient drug response data. Expanding the scale of organoid pharmacogenomic data is expected to further enhance the generalizability of the model. Breast cancer is a high-priority area for future work, where established organoid biobanks offer ideal resources for fine-tuning40,41. The model also holds significant promise for gastric cancer, given that its common chemotherapy regimens overlap with those of colorectal cancer, facilitating effective knowledge transfer42. Furthermore, for highly heterogeneous non-epithelial tumors like sarcomas, fine-tuning with patient-specific organoids could be a powerful strategy to develop personalized predictive models43. Ultimately, expanding the scale and diversity of organoid pharmacogenomic data will be critical to enhancing our model’s generalizability and accelerating the progress of precision medicine.

In conclusion, PharmaFormer introduces a novel paradigm for clinical drug response prediction by effectively integrating different types of preclinical models through transfer learning. This study underscores the potential synergy between advanced organoid models and frontier AI models to accelerate precision medicine and drug development.

Methods

Data collection and preprocessing

Gene expression data for 956 cancer cell lines were obtained from the Cell Model Passports (https://cellmodelpassports.sanger.ac.uk/)44 as transcripts per million (TPM) format. Corresponding drug response data, specifically area under the curve (AUC) values, were acquired from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC2) (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/, version 8.5, accessed on November 6, 2023)9. We chose the AUC as our primary drug response metric for its robustness over point metrics like IC50, as supported by recent analyses45. Drug response data (AUC or inhibition rate) and gene expression profiles for 29 colon organoids31, 65 bladder organoids18, and 21 hepatocellular carcinoma organoids20 were obtained from the published research. A detailed summary of the sample sizes for each of these datasets, including the number of organoids, molecules, and drug response tests, is provided in Supplementary Table 6. All organoid gene expression data were processed to ensure consistency with the cell line data. To specifically assess performance on clinically relevant agents, drugs were annotated based on their FDA approval status. We cross-referenced the drug names from our dataset with the FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations(https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book), downloaded from the official FDA website. Gene expression data of tumor tissues, clinical therapy strategies, and survival data of indicated tumor patients were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). All RNA sequencing data were log-transformed using log2(TPM + 1) to stabilize variance and normalize the distribution. To accurately identify patient cohorts for survival analysis, detailed clinical data, including pharmaceutical therapy records, were downloaded from the TCGA database. This was performed using the TCGAbiolinks R package, which provides access to curated clinical follow-up data. For each drug-specific analysis (e.g., 5-fluorouracil or oxaliplatin in colon cancer), we filtered the patient pool to include only those with explicit, positive confirmation of having received that specific therapy in their treatment regimen records. Patients for whom treatment information was ambiguous, not recorded, or who lacked corresponding RNA-seq and survival data were excluded from the analysis.

Gene expression and drug response data were standardized and normalized using the StandardScaler and MinMaxScaler functions from the scikit-learn library46 before model training. Drug structures formatted as simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) were downloaded from DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/, version 5.1.12), which contains SMILES representations for 11,925 drugs. These structures were encoded using a byte pair encoding (BPE) strategy47, generating a drug structure dictionary of size 10,000.

PharmaFormer, the custom transformer model

PharmaFormer is a deep learning model designed to predict drug responses by integrating gene expression profiles and drug molecular structures. The architecture consists of three main components: feature extractors for genes and drugs, a Transformer encoder, and an output prediction layer (Fig. 1B).

It consists of three stacked Transformer encoder layers, each employing eight self-attention heads to effectively capture dependencies within the input sequence. Each encoder layer has a feedforward network dimension of 2048 and a dropout rate of 0.1, and includes three key components: multi-head self-attention, position-wise feedforward networks, and layer normalization with residual connections, detailed as follows:

The gene feature extractor processes high-dimensional gene expression data to produce a condensed latent representation. The input to this component is a vector of gene expression values for each sample. Specifically, in the input gene expression vector , is the number of genes profiled. In our implementation, corresponds to the number of protein-coding genes shared across all datasets.

The gene feature extractor consists of two fully connected (dense) layers:

First gene layer: It reduces the input dimensionality from to 8192 neurons. It performs the following transformation:

| 1 |

where and .

Second gene layer: It processes the output of the first layer, maintaining the dimensionality at 8192 neurons:

| 2 |

where and .

These layers employ rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation functions to introduce non-linearity and capture essential patterns relevant to drug response.

Drug feature extractor processes the drug structures. Drug molecules are represented by their SMILES strings. The SMILES strings are processed using BPE to convert them into numerical token sequences. Each SMILES string is encoded into a fixed-length vector , where sequences longer than 128 tokens are truncated, and shorter sequences are padded with zeros. The drug feature extractor consists of a single fully connected layer:

| 3 |

where and .

Feature concatenation and reshaping

The outputs from the gene and drug feature extractors, and , are concatenated to form a combined feature vector :

| 4 |

This combined vector is reshaped into a sequence suitable for input to the Transformer encoder. Specifically, is reshaped into a matrix , where is the sequence length and is the feature dimension per token. In our implementation, = 128 (feature dimension), and (sequence length).

The Transformer encoder in PharmaFormer is designed to model complex interactions within the combined feature sequence (gene and drug features) through a self-attention mechanism48. It consists of three stacked Transformer encoder layers, each employing eight self-attention heads to effectively capture dependencies within the input sequence. Each encoder layer includes multi-head self-attention, position-wise feedforward networks, and layer normalization and residual connections, detailed as follows: (1) multi-head self-attention: in each encoder layer, the multi-head self-attention mechanism enables the model to focus on various parts of the input sequence simultaneously, capturing dependencies across different feature tokens. Specifically, each attention head performs scaled dot-product attention, calculating the relevance (or “attention”) between tokens based on their embedded representations. By using eight attention heads, the encoder is able to capture multiple types of relationships within the sequence, allowing it to attend to both short- and long-range dependencies on gene and drug features. (2) Position-wise feedforward networks: After self-attention, the output for each position in the sequence is processed independently by a position-wise feedforward network (PFFN). This network consists of two fully connected layers with a ReLU activation function between them, applied independently at each position. The purpose of the PFFN is to enhance the model’s ability to capture complex and non-linear patterns within the features for each position, without mixing information across positions. This layer helps transform and enrich the feature representations for each token in the sequence. (3) Layer normalization and residual connections: To stabilize training and facilitate gradient flow, each sub-layer within the encoder (both the multi-head self-attention and PFFN) is followed by a layer normalization step. In addition, residual connections are applied by adding the input of each sub-layer to its output before normalization. These residual connections ensure that the model can preserve and refine feature representations over multiple layers, enhancing the model’s ability to learn and maintain meaningful feature representations through each encoder layer. Overall, each encoder layer refines the input representation by using these components to produce an output sequence , where is the sequence length and is the feature dimension. This output sequence contains enriched feature representations that encapsulate the relationships within the gene and drug input features, capturing both their individual properties and their interactions.

Output layer flattened output sequence from the Transformer encoder into a vector :

| 5 |

This vector is passed through two fully connected layers with ReLU activation functions and dropout regularization:

First output layer:

| 6 |

where and .

Second output layer:

| 7 |

where and .

Final prediction layer outputs , which is a scalar value representing the predicted drug response:

| 8 |

where and

Model training

The PharmaFormer has two steps, including pre-training and fine-tuning.

Pre-training proceeds with cell line data. The initial training of PharmaFormer was conducted using the extensive cell line dataset from GDSC2. This dataset included 87,596 cell line-drug pairs, each representing a specific cell line exposed to a particular drug. The dataset was constructed to predict the AUC values for these pairs. The predicted AUC values provided an estimate of drug sensitivity, with higher AUC values indicating lower sensitivity to the drug. Mean squared error (MSE) was investigated as a loss function, and the model was then optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1 × 10−5. A five-fold cross-validation strategy was employed to ensure the robustness of the model, with each fold involving training on 80% of the data and validation on the remaining 20%.

Fine-tuning proceeds with organoid data. To adapt the model to data of higher physiological relevance, PharmaFormer was fine-tuned using the organoid datasets specific to colon (116 organoid-drug pairs), bladder (575 organoid-drug pairs), and Hepatocellular carcinoma (168 organoid-drug pairs). During fine-tuning, the learning rate was kept at 1 × 10−5 to allow careful adjustments based on the new data, and early stopping was implemented based on validation loss to prevent overfitting. L2 regularization and dropout were also applied to stabilize training on the smaller datasets. The model robustness was enhanced by setting a dropout rate of 0.3, avoiding potential noise or overfitting caused by the limited number of samples.

Model evaluation

Model performance was evaluated using five-fold cross-validation during both pre-training and fine-tuning stages. To ensure a rigorous and unbiased assessment of predictive accuracy and to directly address the potential confounding effect of inter-drug variability, our primary evaluation was conducted on a per-drug basis. During this evaluation, any drug with fewer than five corresponding samples in the validation set was excluded from the analysis to ensure statistical robustness. Stratified cross-validation ensured that cell lines or organoids from the same tissue type were evenly distributed across folds, enhancing the robustness of the evaluation.

Predictive performance was assessed using Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between predicted and actual drug responses in both cell lines and organoids. To evaluate PharmaFormer’s performance, several classical machine learning models were also evaluated on the same datasets for comparison. These models included Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Random Forest Regressor (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors Regressor (KNN), and Ridge Regression (Ridge). These models were implemented using the cuML library for GPU acceleration, considerably reducing the time required for training and evaluation. Each classical model underwent the same five-fold cross-validation procedure, with Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients adopted as primary evaluation metrics to ensure comparability with PharmaFormer.

When applying the model to clinical data, the model’s continuous output score was used to stratify patients into high-risk (predicted resistant) and low-risk (predicted sensitive) groups. To determine the optimal cutoff threshold for this stratification in a data-driven manner, we utilized Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis on the prediction scores. The optimal threshold was identified as the point on the ROC curve that maximizes the Youden’s J statistic (J = sensitivity + specificity − 1), which balances the trade-off between the true positive rate and false positive rate. This procedure was performed without using patient survival information to avoid data leakage and ensure an unbiased evaluation of prognostic significance.

For these stratified patient groups, Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were conducted to compare overall survival, and the log-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of any survival differences. Furthermore, each variable, such as drug response scores, age, gender, tumor site, etc., was individually assessed for its association with survival outcomes, and this provided unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and p-values to identify potential predictors. Variables with p < 0.10 in univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in multivariate models. The difference between these two methods was statistically assessed by Wald tests.

To further validate the performance of PharmaFormer, we tested its predictions for 5-fluorouracil response on four independent colorectal cancer patient cohorts obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database: GSE396449, GSE19860, GSE10464550, and GSE10658451. Since these datasets were generated using microarray platforms (probe-based), we processed the raw data and mapped the probe IDs to HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) gene symbols to ensure consistency with the gene features used for our model trained on TCGA RNA-seq data. Patient response annotations provided in the original publications were used as the ground truth.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Python libraries, including scikit-learn46 for data preprocessing, and lifelines52 for survival analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were utilized to determine optimal thresholds for risk stratification. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Cox regression models. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Computational resources and software availability

All computations were performed on servers equipped with NVIDIA Tesla A100 GPUs. The models were implemented using PyTorch (version 2.4.1+cu12.6)53, as well as cuML (version 24.8.0), and were developed in Python (version 3.11.10). Reproducibility was ensured by setting random seeds for NumPy, PyTorch, and Python’s random module. Data preprocessing and analysis utilized scikit-learn (version 1.5.2) and lifelines (version 0.29.0). Byte pair encoding was performed through the subword-nmt package (version 0.3.8).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study is sponsored by bioGenous BIOTECH and Bing Zhao.

Author contributions

Y.Z. and B.Z. conceived the project. Y.Z., Q.D., Y.X., S.W., and M.C. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. M.C. and B.Z. Supervised the study. Y.Z., M.C., and B.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Cell line gene expression data can be accessed via the Cell Model Passport database (https://cellmodelpassports.sanger.ac.uk/), and drug response data for cell lines are available through GDSC2 (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). Organoid gene expression and drug response datasets were retrieved from previously published studies18,20,31. Clinical patient information, including gene expression and survival data, was obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.

Code availability

The PharmaFormer model, including all codes for training, evaluation, training data, and model parameter files, is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/zhouyuru1205/PharmaFormer/).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Minzhang Cheng, Email: mzcheng@ncu.edu.cn.

Bing Zhao, Email: bingzhao@ncu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41698-025-01082-6.

References

- 1.Foulkes, W. D., Smith, I. E. & Reis-Filho, J. S. Triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.363, 1938–1948 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruix, J. et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet389, 56–66 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Beltran, A. et al. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer. BMJ384, e076743 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo, L. et al. Molecular profiling provides clinical insights into targeted and immunotherapies as well as colorectal cancer prognosis. Gastroenterology165, 414–428.e7 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Passaro, A. et al. Cancer biomarkers: emerging trends and clinical implications for personalized treatment. Cell187, 1617–1635 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwaederle, M. et al. Impact of precision medicine in diverse cancers: a meta-analysis of phase II clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol.33, 3817–3825 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sicklick, J. K. et al. Molecular profiling of cancer patients enables personalized combination therapy: the I-PREDICT study. Nat. Med.25, 744–750 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, W. et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res.41, D955–D961 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iorio, F. et al. A landscape of pharmacogenomic interactions in cancer. Cell166, 740–754 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rees, M. G. et al. Correlating chemical sensitivity and basal gene expression reveals mechanism of action. Nat. Chem. Biol.12, 109–116 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuenzi, B. M. et al. Predicting drug response and synergy using a deep learning model of human cancer Cells. Cancer Cell38, 672–684.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang, L. et al. DeepTTA: a transformer-based model for predicting cancer drug response. Brief. Bioinforma.23, bbac100 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia, P. et al. Deep generative neural network for accurate drug response imputation. Nat. Commun.12, 1740 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan, Y. et al. iBT-Net: an incremental broad transformer network for cancer drug response prediction. Brief. Bioinform24, bbad256 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clevers, H. Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell165, 1586–1597 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Wetering, M. et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell161, 933–945 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedayat, S. et al. Circulating microRNA analysis in a prospective co-clinical trial identifies MIR652-3p as a response biomarker and driver of regorafenib resistance mechanisms in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.30, 2140–2159 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrill, N. M. et al. Integrative drug screening and multiomic characterization of patient-derived bladder cancer organoids reveal novel molecular correlates of gemcitabine response. Eur. Urol.86, 434–444 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boilève, A. et al. Organoids for functional precision medicine in advanced pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology167, 961–976.e13 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu, Y. et al. Integrated characterization of hepatobiliary tumor organoids provides a potential landscape of pharmacogenomic interactions. Cell Rep. Med.5, 101375 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veninga, V. & Voest, E. E. Tumor organoids: opportunities and challenges to guide precision medicine. Cancer Cell39, 1190–1201 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foo, M. A. et al. Clinical translation of patient-derived tumour organoids- bottlenecks and strategies. Biomark. Res.10, 10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui, H. et al. scGPT: toward building a foundation model for single-cell multi-omics using generative AI. Nat. Methods21, 1470–1480 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature630, 493–500 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theodoris, C. V. et al. Transfer learning enables predictions in network biology. Nature618, 616–624 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen, J. et al. Deep transfer learning of cancer drug responses by integrating bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Commun.13, 6494 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drost, J. & Clevers, H. Organoids in cancer research. Nat. Rev. Cancer18, 407–418 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu, M. et al. A resource for cell line authentication, annotation and quality control. Nature520, 307–311 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci.28, 31–36 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang, X. et al. Identification of genes related to 5-fluorouracil based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol.13, 887048 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farin, H. F. et al. Colorectal cancer organoid-stroma biobank allows subtype-specific assessment of individualized therapy responses. Cancer Discov.13, 2192–2211 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong, J. et al. Network-based machine learning in colorectal and bladder organoid models predicts anti-cancer drug efficacy in patients. Nat. Commun.11, 5485 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullard, A. Parsing clinical success rates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.15, 447–447 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dowden, H. & Munro, J. Trends in clinical success rates and therapeutic focus. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.18, 495–496 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullard, A. R&D budgets boom, but success rates falter. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.21, 249 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Honkala, A. et al. Harnessing the predictive power of preclinical models for oncology drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.21, 99–114 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Failli, M. et al. Computational drug prediction in hepatoblastoma by integrating pan-cancer transcriptomics with pharmacological response. Hepatology80, 55–68 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma, J. et al. Few-shot learning creates predictive models of drug response that translate from high-throughput screens to individual patients. Nat. Cancer2, 233–244 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chawla, S. et al. Gene expression based inference of cancer drug sensitivity. Nat. Commun.13, 5680 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sachs, N. et al. A living biobank of breast cancer organoids captures disease heterogeneity. Cell172, 373–386.e10 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang, J. et al. CTR-DB 2.0: an updated cancer clinical transcriptome resource, expanding primary drug resistance and newly adding acquired resistance datasets and enhancing the discovery and validation of predictive biomarkers. Nucleic Acids Res.53, D1335–D1347 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nie, R.-C. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: a retrospective, multicenter, observational study. Ann. Surg. Oncol.30, 4014–4025 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo, T. et al. Biomimetic targeted co-delivery system engineered from genomic insights for precision treatment of osteosarcoma. Adv. Sci.12, e2410427 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Meer, D. et al. Cell Model Passports-a hub for clinical, genetic and functional datasets of preclinical cancer models. Nucleic Acids Res.47, D923–d929 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Codicè, F. et al. The specification game: rethinking the evaluation of drug response prediction for precision oncology. J. Cheminform.17, 33 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res.12, 2825–2830 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sennrich, R. et al. Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units. Proc. of ACL1, 1715–1725 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 30, 5998–6008 (2017).

- 49.Graudens, E. et al. Deciphering cellular states of innate tumor drug responses. Genome Biol.7, R19 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okita, A. et al. Consensus molecular subtypes classification of colorectal cancer as a predictive factor for chemotherapeutic efficacy against metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget9, 18698–18711 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu, J. et al. Evaluation of frozen tissue-derived prognostic gene expression signatures in FFPE colorectal cancer samples. Sci. Rep.6, 33273 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson-Pilon, C. Lifelines: survival analysis in Python. J. Open Source Softw.4, 1317 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paszke, A. et al. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst.32, 8026–8037 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Cell line gene expression data can be accessed via the Cell Model Passport database (https://cellmodelpassports.sanger.ac.uk/), and drug response data for cell lines are available through GDSC2 (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). Organoid gene expression and drug response datasets were retrieved from previously published studies18,20,31. Clinical patient information, including gene expression and survival data, was obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.

The PharmaFormer model, including all codes for training, evaluation, training data, and model parameter files, is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/zhouyuru1205/PharmaFormer/).