Abstract

Backgrounds

The role of sex- and gender-related traits has often been downplayed in clinical studies and periodontal disease is no exception. Sex and gender represent distinct biological and sociocultural factors that may independently influence periodontal disease. These factors can affect the risk and progression of periodontal disease as well as response to treatment. This clinical observational study was designed to evaluate gender distribution and the impact of sex and gender on health of gingival tissue using bleeding on probing and probing depth (Periodontal Screening Index “PSI”).

Methods

Four hundred thirty patients were included in this study. Clinical parameters were retrieved from standard examination and a questionnaire was used to assess gender. Sex was characterized as indicated in the birth certificate, a short version of a Swiss-Canadian gender questionnaire was used for the assessment of gender. In addition, patients were asked about self-attribution of gender and the gender Score (GS) was constructed for each subject.

Results

53.0% (228 patients) were females and 47.0% (202 patients) males. No statistically significant differences were observed regarding sex distribution between the categorization of PSI in two and three groups (p = 0.68 and p = 0.57 respectively). The mean gender score (GS) in the subjects with Gingivitis/Mild Periodontitis was 51.75 ± 41.77 while in the subjects with claimed Periodontitis was 51.74 ± 40.55 (One-way ANOVA F = 0.00 p = 0.98). There was no statistically significant association between GS and periodontitis.

Conclusions

This study is one of the first to examine both sex and gender using a validated score in relation to periodontal disease. The outcomes of the cross-sectional study demonstrate that gender is not an indicator for the presence of periodontal disease in Swiss population, emphasizing the need to consider sex and gender as separate factors in clinical studies. Clinical screening protocols may not need to be adjusted based on gender-related traits.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-06719-3.

Keywords: Periodontal disease, Sex, Gender, Periodontitis

Background

The role of sex and gender characteristics has been neglected in clinical studies [1]; although their role in health and disease has been stated by health organizations, sex and gender characteristics have not been sufficiently featured as individual markers in health research for a long time [2, 3].

Notably, sex and gender as independent terms need to be clarified. Whereas sex is a biological variable, relatively unchanging, referring to genetic inheritance and anatomical differences between male and female [4], gender refers more to environmental, social and cultural influences as well as values, attitudes, behaviours and roles, so it is rather a social construct and can change over time.

Whereas for sex as a biological variable the sex on the birth certificate is used by consensus, there is no definite consensus for the assessment of gender [5, 6]. Gender includes psychological and sociocultural variables and differentiates participants beyond the level of biological sex. Gender scores have been developed that aim at integrating the different dimensions of gender into a single variable. This strategy obviously has pros and cons, but it allows to integrate at least some gender aspects in clinical studies [7, 8].

Previous studies in cardiovascular research for example have elucidated a stronger association of death after an acute coronary event with GS than biological sex [5, 9]. This reflects the importance of gender as an independent variable.

Periodontal disease is a complex non-communicable inflammatory condition within the tooth-supporting soft and hard tissues, i.e. gingiva and alveolar bone, thereby resulting in pocket formation, bleeding/suppuration and loss of attachment [10]. It represents a worldwide major public health concern and represents one of the predominant causes for tooth loss and is implicated with several systemic disease conditions [11, 12]. Notably, severe periodontitis is the sixth most prevalent condition worldwide, with a global age-standardized prevalence of 11.2% [13] and the prevalence of periodontitis in the United States accounts to almost 50% [11]. Smoking and diabetes have been elaborated as among the major contributing factors in the progression of periodontitis [14]. Epidemiologic evidence has also demonstrated an evident disparity in periodontitis prevalence between men and women, affecting significantly more men than women [11]. In general, oral health seems to be influenced by sex and gender [15].

Several studies have encountered challenges in distinguishing between sex and gender. A study by Vader et al., 2023 suggests gender plays a major role in chronic diseases [16]. It could be assumed, that periodontitis as well has a large gender component. In another recent study by Su et al., 2022, women in the United States practice better oral hygiene behaviour, supporting the idea that gender has an impact on oral health and oral diseases [17].

While sex and gender are often mentioned in periodontal literature, they are rarely analysed as distinct variables using validated tools. This limits the ability to understand the independent contributions of biological and sociocultural factors to periodontal health. Most existing studies use gender only descriptively without formal measurement.

To add more data to this field of research, the present study was designed to evaluate possible associations between periodontal disease, sex and gender – using a validated gender questionnaire to construct a Gender Score (GS). The hypothesis was that periodontitis is associated with gender as well as sex and that risk factors like smoking and diabetes have an impact on the development of periodontitis.

Methods

Population and sample size calculation

Ethics approval was obtained before the start of the study by “Swiss ethics” (Swiss Association of Research Ethics Committees, BASEC-Nr 2020–02864, date of approval: 16th March 2021).

A selective sample size calculation was carried out taking into account that the sample arbitrarily represents 8′000 patients (number of patients at the Division of Periodontology, Center of Dental Medicine in Zurich, Switzerland), the confidence level was set at 95% with a margin error of 5%. The sample size was calculated accounting for a response rate of 91%, which is based on studies with a similar design [18, 19]. This procedure yielded a sample size of 367. To account for non-responders, the sample size was increased by 15% to improve the validity of the methods resulting in a final required sample size of 422.

Subjects treated at the Division of Periodontology at the Center of Dental Medicine in Zurich, Switzerland were questioned about socioeconomic and sociocultural aspects related to gender. The scientific study included patients suffering from periodontal disease during therapy or during maintenance phase. This population was selected to ensure sufficient representation of individuals with varying stages of periodontal disease. All those patients in the waiting area received the questionnaire. Further inclusion criteria were the following: consent to the use of personal data for research purposes, male and female patients of legal age and willingness to fill out the questionnaire.

Exclusion criteria included a refusal to use personal data and a linguistic or cognitive inability to understand the study.

Questionnaire and clinical assessment

Biological sex was obtained from birth certificates. The short version of a Swiss-Canadian gender questionnaire was used [5]. The gender questionnaire resulted of a multi-stage validation process: The conceptual framework was developed by social scientists and clinicians within the GENESIS-PRAXY programme, built on the four gender dimensions (roles, relations, identity, institutionalised gender) [9]. Data-driven reduction via principal-component analysis [9] was executed to identify items best representing gendered traits. This was followed by sex-stratified logistic regression, producing β-coefficients used to compute an individual Gender Score (0–100). The full version of the questionnaire was validated in the GENESIS-PRAXY cardiovascular cohort study [9]. For a cross-cultural validation, the questionnaire was adapted and validated in a German aging cohort, making the questionnaire transferable to a European cohort [7]. The questionnaire was ultimately shortened, using the three most informative variables, to make it more suitable for clinical use. The short version of the gender questionnaire was modified (in terms of the educational system) for Switzerland and used for the assessment of gender (see additional files) [20]. In addition, patients were asked about self-attribution of gender [9].

Data was collected from May 2021 to October 2022. Volunteering patients completed the questionnaire before their appointment, providing thereby answers to five health and life-style questions (concerning variables such as preventive oral health measures, tobacco usage and systemic diseases that have been shown to play a role in periodontal disease) and eight questions related to age, education, social status, income and a self-assessment of gender and gender-related characteristics.

In addition, clinical data (i.e. Periodontal Screening Index “PSI” including both bleeding on probing “BOP” and probing depth [21] and also dichotomous questions to clinical attachment loss, radiological bone loss, radiological furcation involvement and missing teeth) were collected.

Data analysis

Data were entered into Excel (Microsoft Office, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WS, USA) and analysed using STATA® 18.5 statistical software (StatCorp., Austin, TX, USA) at a statistically significant level of p < 0.05. Qualitative variables were described in terms of absolute and relative frequencies. Associations between categorical variables were tested using Pearson’s chi-square. Quantitative variables were represented by measures of position and variability. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the differences between parametric variables.

The PSI recorded at subject level as the highest score recorded, was grouped into three or two categories: subjects with Healthy/Gingivitis (PSI0-2), Mild Periodontitis (PSI3), Claimed Periodontitis (PSI4) or subjects with Healthy/Gingivitis/Mild Periodontitis (PSI0-3). Claimed Periodontitis refers to a diagnosis based on a PSI grade 4 score, indicating periodontal pockets deeper than 5.5 mm [21]. To classify gender, a gender score (GS) was constructed [7, 9], which ranged from 0 (purely masculine) to 100 (purely feminine). First, a bivariate analysis was performed for the variables obtained in the gender questionnaire and for each significantly correlated pair of variables with a coefficient equal or greater than 0.80, one of the two variables was randomly removed to avoid redundancy and multicollinearity. This approach ensured more stable and interpretable results. Next, PCA analysis was conducted with a varimax rotation method to validate the component matrix result. In interpreting the factor analysis, an item was said to load on a given component if the factor loading was 0.40 or greater for that component and was less for other components (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Principal component analysis of sex and questionnaire items

| Component | Eigenvalue (Difference) | Proportion | Cumulative | |

| First component | 2.12 (0.97) | 0.43 | 0.43 | |

| Second component | 1.15 (0.18) | 0.23 | 0.66 | |

| Third component | 0.97 (0.22) | 0.19 | 0.85 | |

| Fourth component | 0.75 (0.75) | 0.15 | 1.00 | |

| Component |

1st component |

2nd component |

3rd component |

4th component |

| Educational level | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.06 | 0.65 |

| Stress Level | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.04 |

| Affirmative rule | 0.57 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.50 |

| Auto-identification of sex | 0.03 | −0.47 | 0.85 | −0.24 |

Number of obs = 389 Number of comparison = 4

Based on the remaining variables, Logistic regression (LR) models for the association with sex were calculated one by one and all non-significant variables were removed in a descending order based on the size of their non-significant p-value. Bases on this, a gender score was obtained for every patient.

Results

A total of 433 questionnaires were retrieved. Three questionnaires had to be excluded, due to lack of answers either from the personal questions of the patient or the clinical data. Finally, 430 patients were included in the analysis.

Role of biological sex for PSI

53.0% (228 patients) were females and 47.0% (202 patients) males. No statistically significant differences were observed regarding sex distribution between the categorization of PSI in two and three groups (p = 0.68 and p = 0.57 respectively). A slightly higher prevalence of claimed periodontitis was found in females than in males (53.9% versus 49.1%, respectively) (data not in tables).

Assessment of gender and creation of Gender Score (GS)

The results of significant personal characteristics are shown in Table 1 with the educational level, stress level and self-description of patients distributed by sex. A statistically significant difference was noted among sex and educational level, stress level and affirmative rule. 50.3% of the male patients reported a medium level of stress, a lower percentage (46.9%) of females reported the same level of stress. With 40.6%, more females than males see themselves as highly affirmative.

Tables 2 and 3 show the outcomes derived from the full logistic model (Table 2) and the outcomes of all covariates statistically significant at bivariate analysis. The educational level with a p-value of 0.02 suggests a significant association to sex. Two other covariates (stress level and affirmative rule) are also statistically significant, but with a more moderate association.

Table 2.

Distribution of the sample by sex and questionnaire items

|

Males n (%) |

Females n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Educational level | ||

| Primary level | 22 (40.00) | 33 (60.00) |

| Secondary level | 102 (42.68) | 137 (57.32) |

| University | 77 (57.04) | 58 (42.96) |

| χ2(2) = 8.33 p = 0.01 Cuzick's test with rank scores z = 2.65 p < 0.01 | ||

| Stress Level | ||

| Low | 110 (13) | 95 (46.34) |

| Medium | 73 (40.78) | 106 (59.22) |

| High | 17 (40.48) | 25 (59.52) |

| χ2(2) = 7.14 p = 0.03 Cuzick's test with rank scores z = 2.43 p = 0.02 | ||

| Affirmative rule | ||

| Low | 43 (50.59) | 42 (49.41) |

| Medium | 94 (51.93) | 87 (48.07) |

| High | 50 (36.23) | 88 (14) |

| χ2(2) = 8.57 p = 0.03 Cuzick's test with rank scores z = 2.39 p = 0.02 | ||

| Auto-identification of sex | ||

| Male | 173 (93.51) | 12 (6.49) |

| Female | 27 (11.69) | 204 (88.31) |

| χ2(2) = 275.53 p < 0.01 | ||

Table 3.

Logistic regression of the odds of sex and questionnaire items

| Sex | OR (SE) | p-value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level | 0.52 (0.14) | 0.02 | 0.30/0.90 |

| Stress Level | 1.59 (0.43) | 0.09 | 0.93/2.70 |

| Affirmative rule | 1.41 (0.35) | 0.16 | 0.88/2.28 |

| Auto-identification of sex | 103.73 (39.82) | < 0.01 | 48.88/220.12 |

| constant | 0.001 (0.001) | < 0.01 | 0.0001/0.01 |

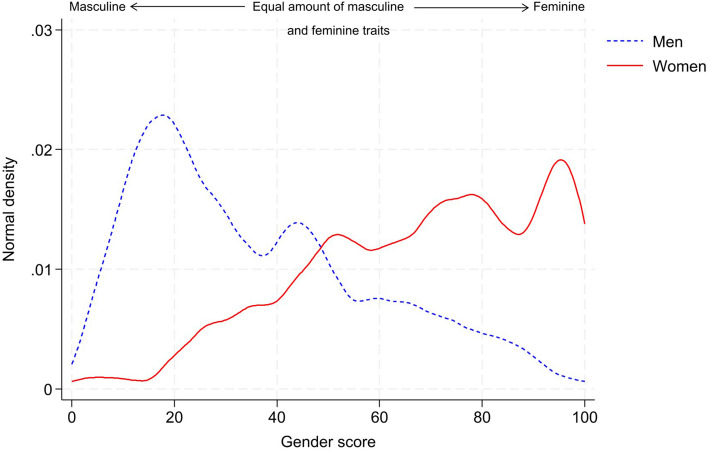

The constructed GS for each patient ranged from 3 to 99, with higher scores representing more feminine traits (see Fig. 1).

Fig.1.

Gender score distribution for men and women

Auto-identification of gender (AI)

Patients were asked to identify themselves along a spectrum from female to male. Of those registered male at birth, 93.5% identified as male and 6.5% identified as female. Among those registered female at birth, 88.3% identify themselves as female, 11.7% identify as male. A higher proportion of individuals assigned female at birth see themselves in the opposite gender spectrum.

Association of Gender Score (GS) and AI with periodontitis

The mean gender score in the subjects with Gingivitis/Mild Periodontitis was 51.75 ± 41.77 while in the subjects with claimed Periodontitis was 51.74 ± 40.55 (One-way ANOVA F = 0.00 p = 0.98) (Table 4). Principal Component Analysis was performed on the data set (Table 5). The first two principal coordinates together account for 66% of the total variance (43 and 23% respectively). 389 data points were included in the analysis.

Table 4.

Logistic model including all covariates statistically significant at bivariate analysis after evaluation of effect modifier

| Sex | OR (SE) | p-value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level | 0.55 (0.11) | < 0.01 | 0.38/0.82 |

| Stress Level | 2.05 (0.41) | < 0.01 | 1.39/3.03 |

| Affirmative rule/Auto-identification of sex | 5.15 (0.90) | < 0.01 | 3.65/7.26 |

| constant | 0.006 (0.005) | < 0.01 | 0.001/0.03 |

Table 5.

Distribution of periodontal status by gender score

| Gender score mean ± SD |

|

|---|---|

| Gingivitis/Mild Periodontitis | 51.75 ± 41.77 |

| Claimed Periodontitis | 51.74 ± 40.55 |

| Anova one way F = 0.00 p = 0.98 |

There was no statistically significant association between GS and periodontitis (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Association of GS with periodontitis, feminine vs. masculine characteristics

Discussion

This study contributes to the inclusion of gender into clinical research. With the use of the gender score, not only sex but the construct of gender with its sociocultural aspects can be measured and compared. However, this study could not demonstrate that gender is a significant indicator for the presence of periodontal disease in this Swiss population. While no statistically significant differences in GS or PSI categories were found between gender groups, the absence of clinically relevant disparities suggests that, in this sample, gender-related traits do not meaningfully influence periodontal disease. Therefore, current clinical screening protocols may not require adjustments based on gender traits.

Regarding the occurrence of periodontitis by sex, Lipsky et al., 2021, were able to show the following results in their review. Reasons of men developing periodontal disease besides their sex and greater tobacco use were poorer oral hygiene behaviour [23]. Furuta et al.2011, showed this in an earlier study with young adults [24]. Also Shiau & Reynolds, 2010, report a higher prevalence for periodontitis in men [25]. Contrary to existing literature, our study found a higher prevalence of chronic periodontitis among women (53.9% vs 49.1%). This finding may be influenced by the composition of our sample, which included only patients receiving periodontal care and not overall population. Women are using health care possibilities more and are likely to follow recommendations by the dentist, potentially leading to higher detection rates [26, 27].

Ioannidou, 2017, addressed the problem of missing gender data in her article about sex and gender intersection in chronical periodontitis. She stated, that even though trial demographics have been presented at study baseline, the outcomes were not disaggregated by gender factors [12]. Michelson et al., as well concluded in their meta-research regarding the SAGER guidelines, that in clinical trial reporting “sex and gender differences were frequently disregarded”. This could potentially limit the comprehension of sex and gender differences in clinical trials who are related to periodontitis [28]. Therefore, there are too few current studies to compare our study with. The Gender Score should provide a tool to incorporate the gender variable in clinical trials.

In the field of other inflammatory disease, studies have shown the importance of gender in clinical research. Tarannum et al., 2023 highlight the influence of gender on inflammatory arthritis, particularly concerning “how individuals perceive illness, seek healthcare, interact with healthcare professionals and cope with the condition” [22]. They also point out that with regard to the socioeconomic status, men tend to rather visit a specialist than a general doctor and thus might be diagnosed earlier [29].

A study in Canada to inflammatory bowel disease [30] highlighted gender-related effects, such as men being less likely to seek healthcare. Nonetheless, the authors state that “there is no clear evidence suggesting that sex or gender influences the incidence or severity of any IBD-complication” [30].

Chronic health conditions were tested for masculine gender affects in a study by Vader et al. [16]. The study suggests that patients with more masculine traits are linked to fewer chronic health conditions. Although periodontitis is considered a chronic inflammatory illness, it was not specifically examined in the study. Therefore, if the protective effects of masculine traits could also apply to periodontitis remains unclear and further research is needed.

Implications for clinical practice and research

We have seen the importance of the inclusion of gender in clinical research as well as into clinical practice. Using the GS provides a tool to compare and evaluate gender aspects. There should be a greater interest to integrate it into research. The GS was calculated in a retrospective manner, meaning that also existing data could be tested for an association of gender with study variables.

Limitations of the study

We used a selective sample size procedure, meaning our sample size does not represent overall population and thus might make it difficult to draw conclusions about overall population. Only patients with chronic periodontitis in therapy or maintenance phase were included. This is shown by the fact, that < 15% of subjects showed PSI 0—2. In contrary, this reflects a strength of the study comparing periodontitis patients, as only 1 subject showed no clinical signs of periodontitis (PSI 0).

Medical information of the patients was only partly collected and data on pregnancy status or hormonal medications were not assessed. These factors may have influenced the outcome especially for women. Further research studies should incorporate a more comprehensive medical assessment.

A full periodontal status was not collected due to logistical and ethical constraints in a large-scale clinical setting. This may limit the diagnostic depth of the study.

Clinical data, namely PSI, were conducted by different dentists and dental hygienists, resulting in possible bias of the examiner. Psychological factors, e.g. stress, were only partly included.

Previous studies comparing GS were linked to illnesses. Periodontitis as an immune response also has genetic associations, potentially making it less comparable to existing studies.

Self-reported data as collected via the questionnaire presents with limitations, particularly on sensitive subjects such as gender identity. Social desirability bias as well as cultural and contextual influences might affect the accuracy of the responses and furthermore compromise the construction and validity of the GS.

Furthermore, the development of GS is as strength as well as a weakness. It helps to measure and compare gender with a score, making it standardized and replicable. Nevertheless, it relies on self-reported data and only a selection of factors is reflected in it. For future research, it may need refinement in cultural sensitivity and validity, as well as integrating qualitative approaches.

Regarding the generalizability of the study and the number of subjects, the study results only apply to our sample. Nevertheless, this novel approach can be expanded and thus applied to a larger population.

Conclusion

Gender in clinical trials and research remains an underrepresentation. This study makes a new contribution by introduction and applying the Gender Score as a quantitative tool to assess gender-related traits in the context of periodontal disease. We provide a more nuanced perspective on potential sociocultural influences that are often overlooked in dental research. We recommend that future periodontal studies routinely include gender metrics like the GS. Clinicians should pay attention to gender-related habits such as oral hygiene behaviour and healthcare-seeking patterns.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the study for completing the questionnaire and for consenting to the use of their data. Thanks also go to the staff for collecting the clinical parameter.

Abbreviations

- BOP

Bleeding on probing

- GS

Gender score

- PD

Probing depth

- PSI

Periodontal screening index

Authors’ contributions

L.L. designed the survey, acquired the primary data, and wrote the draft. V.R.-Z. interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. P.G. interpreted the data, performed the statistical analysis, and prepared figures. G.C. supervised the project, contributed to the data interpretation, and assisted with the statistical analysis and design. P.S. conceived the project, contributed to the design, and supervised the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no external financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

Data is available on request from the authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained before the start of the study by “Swiss ethics” (Swiss Association of Research Ethics Committees, BASEC-Nr 2020–02864, date of approval: 16th March 2021). Written informed consent of the participants was obtained prior to their inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schiebinger L, Stefanick ML. Gender Matters in Biological Research and Medical Practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(2):136–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins FS, Tabak LA. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature. 2014;505(7485):612–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Commission. Fact Sheet: Gender Equality in Horizon 2020. 2013.

- 4.Phillips SP. Defining and measuring gender: a social determinant of health whose time has come. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelletier R, Khan NA, Cox J, Daskalopoulou SS, Eisenberg MJ, Bacon SL, et al. Sex Versus Gender-Related Characteristics: Which Predicts Outcome After Acute Coronary Syndrome in the Young? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(2):127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith PM, Koehoorn M. Measuring gender when you don’t have a gender measure: constructing a gender index using survey data. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nauman AT, Behlouli H, Alexander N, Kendel F, Drewelies J, Mantantzis K, et al. Gender score development in the Berlin Aging Study II: a retrospective approach. Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilote L, Karp I. GENESIS-PRAXY (GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: From bench to beyond-Premature Acute Coronary SYndrome). Am Heart J. 2012;163(5):741-6.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelletier R, Ditto B, Pilote L. A composite measure of gender and its association with risk factors in patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(5):517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ, CDC Periodontal Disease Surveillance workgroup: James Beck (University of North Carolina CH, U. S. A.), Gordon Douglass (Past President, American Academy of Periodontology), R.y Page (University of Washin. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91(10):914–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ioannidou E. The Sex and Gender Intersection in Chronic Periodontitis. Front Public Health. 2017;5:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93(11):1045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eke PI, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Borrell LN, Borgnakke WS, Dye B, et al. Risk Indicators for Periodontitis in US Adults: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2016;87(10):1174–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell SL, Gordon S, Lukacs JR, Kaste LM. Sex/Gender differences in tooth loss and edentulism: historical perspectives, biological factors, and sociologic reasons. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57(2):317–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vader SS, Lewis SM, Verdonk P, Verschuren WMM, Picavet HSJ. Masculine gender affects sex differences in the prevalence of chronic health problems. Prev Med Rep. 2023;33: 102202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su S, Lipsky MS, Licari FW, Hung M. Comparing oral health behaviours of men and women in the United States. J Dent. 2022;122: 104157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusnoor SV, Koonce TY, Hurley ST, McClellan KM, Blasingame MN, Frakes ET, et al. Collection of social determinants of health in the community clinic setting: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geoghegan F, Birjandi AA, Machado Xavier G, DiBiase AT. Motivation, expectations and understanding of patients and their parents seeking orthodontic treatment in specialist practice. J Orthod. 2019;46(1):46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gebhard CE, Sütsch C, Gebert P, Gysi B, Bengs S, Todorov A, et al. Impact of sex and gender on post-COVID-19 syndrome, Switzerland, 2020. Euro Surveill. 2024;29(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Landry RG, Jean M. Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR) Index: precursors, utility and limitations in a clinical setting. Int Dent J. 2002;52(1):35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarannum S, Widdifield J, Wu CF, Johnson SR, Rochon P, Eder L. Understanding sex-related differences in healthcare utilisation among patients with inflammatory arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(2):283–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipsky MS, Su S, Crespo CJ, Hung M. Men and Oral Health: A Review of Sex and Gender Differences. Am J Mens Health. 2021;15(3):15579883211016360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furuta M, Ekuni D, Irie K, Azuma T, Tomofuji T, Ogura T, et al. Sex differences in gingivitis relate to interaction of oral health behaviors in young people. J Periodontol. 2011;82(4):558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiau HJ, Reynolds MA. Sex differences in destructive periodontal disease: a systematic review. J Periodontol. 2010;81(10):1379–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coda Bertea P, Staehelin K, Dratva J, Zemp SE. Female gender is associated with dental care and dental hygiene, but not with complete dentition in the Swiss adult population. J Public Health. 2007;15(5):361–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tada A, Hanada N. Sexual differences in oral health behaviour and factors associated with oral health behaviour in Japanese young adults. Public Health. 2004;118(2):104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michelson C, Al-Abedalla K, Wagner J, Swede H, Bernstein E, Ioannidou E. Lack of attention to sex and gender in periodontitis-related randomized clinical trials: A meta-research study. J Clin Periodontol. 2022;49(12):1320–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarannum S, Leung YY, Johnson SR, Widdifield J, Strand V, Rochon P, et al. Sex- and gender-related differences in psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(9):513–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Targownik LE, Bollegala N, Huang VH, Windsor JW, Kuenzig ME, Benchimol EI, et al. The 2023 Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: The Influence of Sex and Gender on Canadians Living With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023;6(Suppl 2):S55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on request from the authors.