Abstract

Background

As an essential component of public health infrastructure, public health education plays an important role in advancing health equity. In China, the large migrant population, while contributing substantially to socioeconomic development, continues to face significant health risks and inequalities due to frequent rural-to-urban mobility and occupational transitions. These issues not only undermine the well-being of migrants but also impede balanced social and economic progress. In this context, the present study systematically investigated the impact of public health education on health inequalities among the migrant population and explored the underlying mechanisms through which it exerts its influence.

Methods

Based on data from the China Migrants Dynamic Survey, this study employed the Recentred Influence Function regression method—a two-dimensional decomposition technique—combined with Instrumental Variable approaches to examine how public health education influences health inequality and to explore the underlying mechanisms.

Results

The findings indicated that health inequality among migrants followed a pro-rich socioeconomic gradient, with substantial regional heterogeneity. Participation in public health education programs was associated with a significant reduction in health inequality. After accounting for endogeneity, receiving two or more types of public health education was linked to a 0.102-unit decline in the Wagstaff-Erreygers Index (p < 0.001), implying that the income-related health concentration curve might have narrowed by approximately 47.4% relative to the equality line. Heterogeneity analysis showed that these effects were more pronounced among non-interprovincial migrants and self-employed individuals. Further analysis suggested that the inequality-reducing effect of public health education was mediated primarily through improved healthcare availability, which exerted stronger mediating effects than enhanced healthcare accessibility.

Conclusion

Enhancing the provision and effectiveness of public health education and safeguarding the health rights of vulnerable groups are vital to narrowing health disparities. Accelerating the development of an inclusive public health system tailored to the migrant population will support the reduction of health inequality and contribute to the coordinated advancement of the Healthy China initiative.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-025-13123-8.

Keywords: Migrant population, Public health education, Health inequality

Background

Health is a vital component of human capital. In the context of advancing the Healthy China Initiative, ensuring comprehensive and continuous protection of people’s health has become increasingly urgent. As a key tool for promoting this initiative, public health education aims to improve residents’ awareness, prevention skills, and emergency response capacities for infectious diseases and other public health emergencies, thereby enhancing population health outcomes [1]. However, the migrant population—a vulnerable group in health prevention and care—faces higher health risks and is more prone to falling into negative health cycles. According to China’s Seventh National Population Census (2021), there are 376 million migrants, accounting for 27% of the total population. Such large-scale mobility exacerbates structural vulnerabilities in the public health system, notably through epidemic surveillance gaps caused by dynamic migration and resource allocation imbalances rooted in the household registration system [2]. Therefore, improving migrants’ access to public health education is crucial for enhancing their health, strengthening national health infrastructure, and advancing the Healthy China Initiative.

Health status arises from the complex interactions between multidimensional factors, including socio-environmental conditions, biological endowments, and individual behaviors [3]. This complexity highlights the systemic nature of health inequalities, which stem from persistent disparities in resource distribution embedded within societal structures. The 14th Five-Year Plan and the Long-Range Objectives for 2035 emphasize not only overall population health but also health equity. Since the 1980 s, widespread academic attention has focused on health inequalities, establishing consensus that socioeconomically advantaged groups have better resource access, leading to health advantages—a phenomenon known as health stratification [4–6]. For migrants marginalized in urban areas, health outcomes depend not only on socioeconomic status but also on factors such as employment status, migration distance, and mobility frequency, which together perpetuate complex health inequalities within this group [7]. As a country with massive population mobility, identifying the determinants and mechanisms to reduce health inequalities among migrants, while improving their health status, has become a critical research priority [8].

In recent years, public health education has emerged as a vital tool for enhancing health literacy and promoting healthier behaviours among residents [9]. It plays an increasingly important role in mitigating health inequalities and promoting health equity [10]. Unlike the indirect effects typically associated with general educational attainment, public health education directly influences health outcomes by shaping health knowledge, risk perceptions, and service navigation, especially among marginalized populations such as migrants [11]. Prior studies suggest that public health education can enhance the accessibility and efficiency of medical service utilization, thereby improving overall health status [12]. For example, Granda and Jimenez found that preventive services, including health education, yield higher marginal benefits among disadvantaged groups and help narrow health disparities [13]. Similarly, in a comparative study of welfare states, Thomson et al. highlighted the effectiveness of systematic health education policies in promoting health equity [14].

In China, equalization policies for basic public health services have incorporated health education as a vital component, particularly for migrant populations [15]. However, migrants still encounter institutional barriers, unequal resource distribution, and information asymmetry when accessing these services [16, 17]. The mechanisms through which public health education reduces health inequalities, such as improving healthcare accessibility, remain insufficiently explored [18], especially in causal inference studies targeting migrants. Moreover, existing research on health inequality largely focuses on factors such as healthcare policy reforms, social capital, and urbanization [19–21], while paying limited attention to public health education intervention pathways for migrant populations.

Although hukou system reforms have improved health rights protection for migrants [22], China continues to face severe health inequalities among this large population. These disparities limit migrants’ personal development and exacerbate broader societal inequities. This study asked: Can public health education reduce health inequalities among migrants? Does this effect vary across different groups? What mechanisms underlie its impact? To address these questions, this study used data from the 2018 China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS) and applied an Instrumental Variable (IV) approach to control for endogeneity to investigate how public health education influences health inequality and its underlying mechanisms. The aim was to provide evidence-based insights for optimizing public health policies, advancing the Healthy China Initiative, and promoting equitable development.

Methods

Data source and processing

This study used data from the 2018 CMDS, a nationally representative dataset administered by the National Health Commission. The survey focused on internal migrants aged 15 years and above who had lived in their current location for more than one month. It covered all 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities in mainland China. The available data includes information on migrants’ living conditions, mobility, access to public health services, and family planning.

To explore the impact of public health education on health inequality, the CMDS microdata were combined with macro-level data on the number of community service centers in the fourth quarter of 2018, obtained from the Ministry of Civil Affairs. The sample was restricted to domestic migrants, and observations with missing values for key variables (Dependent variable, Core explanatory variables, Control variables) were excluded. The final sample comprised 125,220 individuals.

Measurement method and econometric model

Measurement of health inequality

When defining the concept of health inequality, researchers often use the terms “health inequity” and “health inequality” interchangeably, though they differ in meaning. Health inequity implies unjust health disparities based on moral, ethical, and value judgments, whereas health inequality refers to the quantitative evaluation of health differences between groups [23]. The concept of health inequality has various connotations that can be categorised into three types. The first is structural health differences that result from social structural differences caused by systems or policies, leading to socially disadvantaged groups such as women, the poor, and minorities experiencing higher health risks [24]. Second, from a biological perspective, health inequality is a general term for differences, variations, and gaps between an individual’s and a group’s health level [25, 26]. Third, this term refers to the phenomenon of health stratification linked to socioeconomic status, which relates to the phenomenon of differences in the health status of people with different socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., social class, occupation, social ranking, gender, income, education, culture) [6], with those of higher socioeconomic status having a better health status. Of the three types of health inequality, most scholars consider health differences caused by socioeconomic status to reflect the true sense of health inequality [27]. Therefore, this study focused on health inequality related to economic income; specifically, the differences in the distribution of health outcomes among different income groups.

Among the methods used to measure health inequality, Wagstaff et al. (1989) introduced the Concentration Index (CI), linking health and income for the first time to explore the health distribution differences of groups of different socioeconomic status [28]. Since then, the CI has become a widely recognised and used measurement method for health inequality in both domestic and international academia. Another index, the Erreygers Index (EI), was proposed by Erreygers (2009) to address the arbitrariness of the CI in defining individual health levels by specifying the upper and lower limits of the health level [29]. Subsequently, the Wagstaff-Erreygers Index (WI) introduced further refinements of the EI to enhance measurement precision [30]. However, each health inequality index has its limitations in practice. Therefore, this study employed the CI, EI, and WI indices to measure health inequality, ensuring the robustness of the measurement results. All three indices examine the distribution of health and income, and their calculation formulas are as follows:

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

where  represents the health level of the individual

represents the health level of the individual  ,

,  represents the mean health level of the group,

represents the mean health level of the group,  represents the income ranking of the individual

represents the income ranking of the individual  ,

,  represents the lower limit of the health levels, and

represents the lower limit of the health levels, and  represents the upper limit of the health levels. The CI, EI, and WI indices range from [− 1 to 1]. A negative index value indicates that there is a “pro-poor” health difference; an index value of zero indicates that there is no health inequality related to income differences among the groups; a positive index value indicates that there is a “pro-rich” health difference; that is, the higher-income group has a better health status.

represents the upper limit of the health levels. The CI, EI, and WI indices range from [− 1 to 1]. A negative index value indicates that there is a “pro-poor” health difference; an index value of zero indicates that there is no health inequality related to income differences among the groups; a positive index value indicates that there is a “pro-rich” health difference; that is, the higher-income group has a better health status.

The health inequality regression model: RIF-I-OLS decomposition model

This study investigated the impact of public health education on income-related health inequalities among migrant populations. The CI decomposition method proposed by Wagstaff et al. (2003) essentially involves unidimensional decomposition of population health metrics [6], and its reliance on multiple restrictive assumptions during decomposition may introduce biases in the results [31]. To address these limitations, this study employed the Recentred Influence Function-Index-Ordinary Least Squares (thereafter referred to as RIF-I-OLS) decomposition model based on the Recentred Influence Function (thereafter referred to as RIF) to investigate factors influencing health inequalities among migrant populations. The RIF-I-OLS model, proposed by Swedish scholar Heckley in 2016 [32], employs the Recentred Influence Function value of a health inequality index I (denoted as RIF-I) to construct the individual-level health inequality index. The principle relies on the property that  , which means the expected value of the recentred influence function value of the health inequality index I is equal to I itself. This allows the target statistic I to be expressed as a function of the explained variable through iterative expectations

, which means the expected value of the recentred influence function value of the health inequality index I is equal to I itself. This allows the target statistic I to be expressed as a function of the explained variable through iterative expectations  . Therefore, the marginal effect of the regression with

. Therefore, the marginal effect of the regression with  as the explained variable is equivalent to that of the regression on

as the explained variable is equivalent to that of the regression on  . This allows for the estimation of public health education on health inequality among a migrant population.

. This allows for the estimation of public health education on health inequality among a migrant population.

The RIF-I-OLS estimation involved two stages. In the first stage, the RIF values for each target statistic were calculated, namely RIF_CI, RIF_EI, and RIF_WI, representing the RIF transformations of the health inequality indices CI, EI, and WI, respectively. The specific expressions are as follows:

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

10 |

where  is the absolute CI;

is the absolute CI;  ,

,  , and

, and  are the target statistics, determined by the joint distribution of health level

are the target statistics, determined by the joint distribution of health level  and income level

and income level

; and IF is the influence function of the target statistics.1

; and IF is the influence function of the target statistics.1

In the second stage, the RIF-based linear regression model was constructed. The linear regression equation was as follows:

|

11 |

where  represents the RIF-transformed health inequality index (CI, EI, or WI) for migrant individual

represents the RIF-transformed health inequality index (CI, EI, or WI) for migrant individual  , i.e., the recentred influence function value;

, i.e., the recentred influence function value;  is the core explanatory variable of this study, indicating the individual

is the core explanatory variable of this study, indicating the individual  ’s exposure to public health service education;

’s exposure to public health service education;  is the control variable; and

is the control variable; and  is the random disturbance item.

is the random disturbance item.

To address potential endogeneity arising from bidirectional causality and omitted variables, an IV approach was employed for causal identification. The IV was constructed as the interaction term between the provincial-level count of community service centres (Q4 2018) and the community-average number of public health education programs participated in by migrant workers. From a macro perspective, community service centres serve as primary platforms for disseminating public health education. A higher density of such centres positively correlates with migrants'uptake of health education programs, satisfying the relevance requirement. Simultaneously, provincial-level counts of community service centres—as an objective institutional indicator—remain largely unaffected by individual migrants’ health status, ensuring exogenous variation. At the micro level, the migrant population was divided into 1,177 groups based on their communities. The community-level mean of public health education participation captures peer effects: individuals’ health education engagement correlates with group-level behaviours, while personal health status has a limited effect on the group mean—further supporting the validity of the IV. To maximize robustness, macro-level infrastructure data (community service centres) were combined with micro-level behavioural metrics (community-level mean of public health education participation) to derive an interaction term as the IV for this study. Then, using a two-stage least squares (2SLS) framework, the following system was estimated:

|

12 |

|

13 |

In Eqs. (12) and (13),  represents the selected IV,

represents the selected IV,  and

and  are random disturbance items, and

are random disturbance items, and  In addition, to test the mediating effects of medical accessibility and approachability for the migrant population, based on controlling endogeneity using IVs, this study used the mediation effect model of Wen and Ye to enhance the reliability of the mediator variable and the robustness of the regression results [33].

In addition, to test the mediating effects of medical accessibility and approachability for the migrant population, based on controlling endogeneity using IVs, this study used the mediation effect model of Wen and Ye to enhance the reliability of the mediator variable and the robustness of the regression results [33].

Definition and description of variables

The dependent variable in this study was health inequality. To analyse the bivariate health inequality index derived from the joint distribution of health and income, three indices were calculated—the CI, EI, and WI—collectively denoted as I. Using the RIF transformation, we generated corresponding RIF values (RIF_CI, RIF_EI, RIF_WI), which served as core dependent variables in the subsequent regression analyses. Based on the formation mechanism of the RIF_I values, the mean values of RIF_CI, RIF_EI, and RIF_WI for all individuals in the sample were equal to the CI, EI, and WI values, respectively. Additionally, given that the WI represents a refined measure of health inequality, RIF_WI was selected as the dependent variable for heterogeneity analysis and mediation mechanism tests.

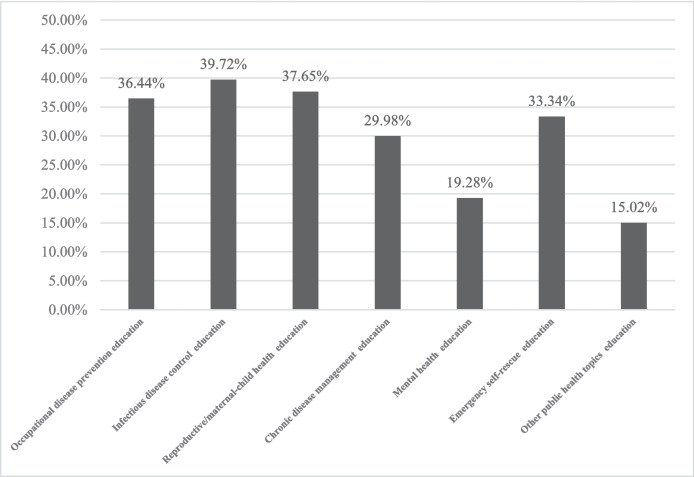

The core explanatory variable in this study was public health education. Drawing on the CMDS2018 dataset, this variable was operationalized using the survey item: “In the past year, have you received health education in your current residential community (village/neighbourhood committee) on any of the following topics: occupational disease prevention, infectious disease control, reproductive/maternal-child health, chronic disease management, mental health, emergency self-rescue, or other public health topics?” Respondents who received education in two or more topics were coded as 1, while the others were coded as 0. Figure 1 presents the distribution of public health education participation among migrants. Overall, participation rates remained below 50% across all health education categories. Specifically:

Infectious disease control education showed the highest participation rate at nearly 40%.

Mental health education had the lowest uptake at only 19.28%.

Participation rates for occupational disease prevention and reproductive/maternal-child health education were comparable at 36.44% and 37.65%, respectively.

The remaining categories were in the following descending order: Emergency self-rescue education: 33.34%, Chronic disease management education: 29.98%, Other health education topics: 15.02%.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of public health education participation among migrants

Several control variables that could influence health inequality in the migrant population were also included, such as demographic, socioeconomic, employment, and mobility characteristics [34]. In terms of demographic characteristics, age, gender, marital status, and household size were controlled for. The socioeconomic characteristics were represented by income and education variables. The income variable was transformed into the logarithm of average monthly income, and the education variable was categorised into four groups: primary school, junior high school, high school/special secondary school, and college or above, with below primary school as the reference group. In terms of employment characteristics, employment type (self-employed), weekly working hours, and insurance status were controlled for. At the same time, the health status of the migrant population is also affected by the incidence of diseases; the presence of a disease/injury in the past year was used as a proxy variable. Finally, in terms of mobility characteristics, willingness to stay in the city and migration types served as control variables. Additionally, regional dummy variables were included to capture geographic heterogeneity. Table 1 provides detailed descriptive statistics for all variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable name | Variable definition | Mean value | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health inequality | Using the Recentred Influence Function (RIF) | 0.0081 | 0.0668 |

| transformation generates corresponding RIF | 0.0417 | 0.3372 | |

| values(RIF_CI RIF_EI, RIF_WI) | 0.2150 | 0.2440 | |

| Public health education | Respondent received public health education on two or more topics = 1; otherwise = 0 | 0.5159 | 0.4997 |

| Age | Continuous variable of age | 37.0503 | 11.2036 |

| Gender | Female = 1; male = 0 | 0.4859 | 0.4998 |

| Marital status | Married = 1; unmarried = 0 | 0.8079 | 0.3940 |

| Household size | Count variable of the number of household members | 3.1406 | 1.2108 |

| Income | Continuous variable of the logarithm of average monthly income | 8.7511 | 0.6064 |

| Primary school | Education level is primary school = 1, otherwise = 0 | 0.1351 | 0.3418 |

| Junior high school | Education level is junior high school = 1, otherwise = 0 | 0.4218 | 0.4938 |

| High school/special secondary school | Education level is high school/special secondary school = 1, otherwise = 0 | 0.2238 | 0.4168 |

| University and above | Education level is university and above = 1, otherwise = 0 | 0.1940 | 0.3954 |

| Disease status | Illness/injury in the past year = 1; otherwise = 0 | 0.1139 | 0.3177 |

| Employment types | Self-employed = 1; otherwise = 0 | 0.3743 | 0.4839 |

| Working hours | Continuous variable of weekly working hours | 58.2667 | 19.7162 |

| Employee health insurance | Participation in employee health insurance = 1; otherwise = 0 | 0.2505 | 0.4333 |

| Willingness to stay in the city | Planning to stay in the area for a while in the future = 1; otherwise = 0 | 0.8510 | 0.3561 |

| Migration types migration | Interprovincial Migration = 1; otherwise = 0 | 0.5055 | 0.5000 |

Results

Distribution of health status and disparities among China's migrant population

The distribution of the health status of the migrant population was analysed in terms of gender, education level, and income. The results are shown in Table 2. Among the migrant population, a relatively large proportion of individuals self-assessed their health as “very healthy”. Gender disparities were evident, with males generally exhibiting better health outcomes compared to females. This aligns with the gender-health paradox, which posits that while females tend to have a longer life expectancy, their physical health status is often inferior to males [35]. From the perspective of education, those with a primary school education or below had significantly lower health levels than those with higher education levels, and health status showed an increasing trend with improvement in education level. Similarly, health status showed a positive association with income tiers, where higher income quintiles correlated with better health metrics. The mean health scores revealed minimal gender-based differences in overall health status. However, both educational attainment and income level exhibited statistically significant positive correlations with health outcomes, providing empirical confirmation of the positive association between socioeconomic status (SES) and health status.

Table 2.

Health distribution of the migrant population

| Health status | Gender | Education level | Income | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Primary school and below | Junior high school | High school/special secondary school | University and above | Low income | Middle income | High income | |

| Very unhealthy | 0.09% | 0.08% | 0.32% | 0.05% | 0.04% | 0.02% | 0.17% | 0.04% | 0.02% |

| Unhealthy | 1.66% | 2.41% | 7.00% | 1.52% | 0.91% | 0.30% | 3.68% | 1.02% | 0.67% |

| Healthy | 10.84% | 11.35% | 18.30% | 10.94% | 9.37% | 7.44% | 13.24% | 9.72% | 9.55% |

| Very healthy | 87.40% | 86.16% | 74.38% | 87.49% | 89.68% | 92.24% | 82.91% | 89.22% | 89.76% |

| Average score | 3.8559 | 3.8555 | 3.6674 | 3.8586 | 3.8869 | 3.9189 | 3.7888 | 3.8812 | 3.8905 |

Table 3 depicts the regional health disparities among migrant populations using the CI, EI, and WI across four regions: Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern China. As shown in Table 3, all three indices—CI, EI, and WI—were statistically significant and positive at both national and regional levels, indicating a pronounced pro-rich health gradient where higher-income groups demonstrated stronger health advantages. Notably, cross-regional comparisons indicate that the values of these indices are the lowest in the Eastern region, suggesting that health inequality among residents there is more pronounced than in the Central, Western, and Northeastern regions. Overall, migrant health inequalities revealed significant regional disparities.

Table 3.

The assessment of health disparities among the migrant population across various regions in China

| CI index | EI index | WI index | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National | 0.0081*** | 0.0417*** | 0.2150*** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0008) | (0.0042) | |

| Eastern China | 0.0025*** | 0.0129*** | 0.0856*** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0010) | (0.0069) | |

| Central China | 0.0061*** | 0.0316*** | 0.1840*** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0018) | (0.0103) | |

| Western China | 0.0105*** | 0.0531*** | 0.2250*** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0017) | (0.0071) | |

| Northeast China | 0.0258*** | 0.1280*** | 0.3680*** |

| (0.0009) | (0.0044) | (0.0125) |

***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The robust standard errors are in parentheses

Empirical examination of the impact of public health education on migrant health inequalities

In this section, RIF regressions were employed to quantify the impact of public health education on three measures of health inequality: the CI, EI, and WI. As shown in Column (6) of Table 4, the two-stage least squares (2SLS) IV approach revealed a statistically significant negative association between public health education and WI-measured health inequality (β = − 0.1020, p < 0.01). The first-stage F-statistic of 385.03 (exceeding the Stock-Yogo critical value of 10) validated the strength of the IV. This effect magnitude represents a 45.9% increase compared to the OLS estimate (β = − 0.0701), underscoring the substantial downward bias introduced by endogeneity in conventional models.

Table 4.

The impact of public health education on health inequality in the migrant population based on RIF-I-OLS

| OLS | 2SLS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| RIF_CI | RIF_EI | RIF_WI | RIF_CI | RIF_EI | RIF_WI | |

| Public health education | -0.0041*** | -0.0204*** | -0.0701*** | -0.0059*** | -0.0295*** | -0.1020*** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0014) | (0.0053) | (0.0012) | (0.0062) | (0.0226) | |

| Other variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Provincial effect | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| The first-stage F-statistic | / | / | / | 385.0300 | 385.0300 | 385.0300 |

| Observed value | 125,220 | 125,220 | 125,220 | 123,730 | 123,730 | 123,730 |

| R-squared | 0.1040 | 0.1040 | 0.0930 | 0.1050 | 0.1050 | 0.0940 |

***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10% levels, respectively. The robust standard errors are in parentheses

Notably, public health education exhibited significant negative effects across all three inequality metrics, with the strongest marginal reduction observed for the WI (β = − 0.102). This pattern suggests that the WI measure, which incorporates distributional adjustments, provides heightened sensitivity for evaluating public health education interventions. The models, which controlled for provincial heterogeneity and individual covariates, demonstrated moderate explanatory power, with R2 values consistently within the 0.0940–0.1050 range, supporting the robustness of our specification.

The quantitative analysis of economic effects demonstrated that public health education held significant policy value in mitigating health inequalities among migrant populations. Taking the WI as an example, migrants receiving two or more public health education programs exhibited a 0.102-unit reduction in health inequality after accounting for endogeneity. Given the baseline WI of 0.215 in the sample, this translates to a 0.474-fold contraction of the area between the income-related health concentration curve and the 45° equality line, indicating direct mitigation of health inequality through multi-component health education. The observed effect may be due to the “pro-rich” distribution of health resources among migrants (WI > 0), while public health education has a “pro-poor” effect on health improvement. Specifically, low-income migrants derive greater marginal health benefits from community outreach activities like public health education compared to their high-income counterparts [36], thereby effectively mitigating health disparities. From a policy perspective, enhancing public health education service delivery not only directly reduces health inequality but also advances the common prosperity agenda through promoting equitable access to essential public services. These findings provide critical evidence for implementing China's Healthy China 2030 strategy, particularly in addressing systemic inequities through targeted health interventions.

Additionally, subgroup analyses were performed to explore the heterogeneous effects of public health education on health inequality among migrant populations stratified by migration and employment types. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Heterogeneous analysis by migration and employment types based on the RIF-I-OLS model

| (1) Migration Types | (2) Employment Types | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Interprovincial | Non-interprovincial | Self-employed | Non-self-employed |

| Public health education | −0.0651*** | −0.0727*** | −0.0568*** | −0.0766*** |

| (0.0089) | (0.0065) | (0.0084) | (0.0067) | |

| Other variables | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Provincial effect | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −6.219*** | −6.122*** | −6.179*** | −6.107*** |

| (0.1050) | (0.0794) | (0.0970) | (0.0845) | |

| Observations | 46,864 | 78,356 | 46,940 | 78,280 |

| R-squared | 0.0870 | 0.0990 | 0.0890 | 0.0970 |

***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The robust standard errors are in parentheses

First, based on the migration types reported by respondents (interprovincial, intra-provincial cross-city, and intra-city cross-county), migrants were categorized into two groups: those selecting “interprovincial migration” were classified as Group 1, i.e., interprovincial migrants, while those choosing “intra-provincial cross-city migration” or “intra-city cross-county migration” were grouped as Group 2, i.e., non-interprovincial migrants. Column (1) of Table 5 shows that non-interprovincial migrants exhibited a significantly stronger reduction in health inequality (coefficient: − 0.0727***, SE = 0.0065) compared to interprovincial migrants (− 0.0651***, SE = 0.0089), suggesting that shorter migration distances correlate with greater health equity improvements. This disparity might be attributed to several factors. Specifically, migrants with shorter migration distances experience greater convenience in accessing healthcare services [34, 37]. They are more likely to maintain their original medical insurance coverage from their hometowns, which enables smoother medical reimbursement processes. Moreover, as their mobility occurs within the same province or even the same city, they benefit from shared linguistic, cultural, and lifestyle norms that facilitate better comprehension of health information and easier access to medical resources, and this ultimately contributes to higher life satisfaction [38]. The stronger presence of kinship networks further ensures practical caregiving support during health emergencies. In contrast, interprovincial migrants face compounded challenges in these dimensions, including insurance continuity barriers, cultural adaptation difficulties, and reduced social support. Consequently, public health education interventions demonstrate relatively weaker effectiveness in improving health equity outcomes for this population group.

Second, a categorical analysis of migrants’ employment types was conducted by classifying migrants into two distinct groups: self-employed and non-self-employed. Column (2) reveals that self-employed migrants experienced a significantly larger reduction in health inequality (− 0.0568***, SE = 0.0084) compared to non-self-employed workers (− 0.0766***, SE = 0.0067), indicating that self-employment partially mitigates health disparities. This disparity might be attributed to the occupational autonomy inherent in self-employment, which grants this population greater agency in health decision-making, enabling more flexible scheduling of medical visits. Simultaneously, the income volatility characteristic of small business ownership fosters stronger preventive health investment tendencies among the self-employed, manifesting in more proactive health maintenance behaviours [39].

Further analysis

After examining how public health education could alleviate health inequality in the migrant population, the pathways through which public health education alleviates health inequalities among migrant populations were investigated. To investigate the mediating mechanisms, the RIF_WI index was employed as the health inequality measure, and data from the CMDS were analysed. Two variables, “Whether a health record was established” and “Whether a family doctor was contracted”, were selected as proxies for healthcare availability and accessibility, coded as 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no”. Statistical analysis revealed that only 28% of migrants had established health records, and 12% had contracted family doctors, indicating substantial room for improvement in healthcare access. Methodologically, a two-stage approach was adopted: the first stage employed the Probit model to address endogeneity, while the second stage utilized RIF-I-OLS regression to assess the mediating mechanisms of healthcare accessibility indicators.

In Table 6, Columns (1) and (2) present the relationships between public health education (core explanatory variable) and the mediators under endogeneity control. The findings indicated that public health education exhibited statistically significant positive coefficients at the 1% level for both mediators, implying that migrant participation in health education programs significantly improves healthcare availability and accessibility. Columns (3) and (4) further show the joint effects of public health education and mediators on health inequality. The results demonstrated that both healthcare availability and accessibility significantly reduced health inequality (RIF_WI index), with coefficients significant at the 1% level. The main effect of public health education remained significantly negative, confirming the partial mediation role of healthcare access indicators.

Table 6.

Analysis of the mechanism of the impact of public health education on health inequality among the migrant population

| Probit Model | RIF-I-OLS Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Medical availability | Medical accessibility | RIF_WI | RIF_WI | |

| Public health education | 0.543*** | 0.603*** | −0.0685*** | −0.0716*** |

| (0.00917) | (0.0122) | (0.0061) | (0.0061) | |

| Medical availability | −0.0389*** | |||

| (0.0062) | ||||

| Medical accessibility | −0.0322*** | |||

| (0.0083) | ||||

| Control variable | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Constant | −1.350*** | −1.711*** | −6.1710*** | −6.1800*** |

| (0.0925) | (0.121) | (0.0699) | (0.0701) | |

| Observed value | 99,928 | 101,694 | 99,928 | 101,694 |

***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The robust standard errors are in parentheses

Discussion

This study empirically examined potential links between public health education and health inequality among migrant populations. From the perspective of health accumulation, health can be viewed as an “investment product” that may increase human capital stock, potentially extending participation in various activities and supporting health status sustainability [40]. Improving public health education could serve as a valuable strategy to facilitate health human capital accumulation, possibly leading to better health outcomes through enhanced healthcare knowledge. These relationships, however, require further verification. As a population often vulnerable in terms of health risk management, implementing community-based public health education programs for migrants remains crucial for infectious disease control and wellbeing [1].

Research highlights economic differences in education acceptance rates, with lower-income groups tending to participate more than higher-income groups [41]. One possible explanation for this result is that higher-income groups possess greater social capital and more flexible medical channels, enabling them to access a wider range of health services [42] while lower-income groups have limited access to healthcare services, making public health education an effective means of promoting their health human capital accumulation and improving their labour supply and performance in the job market. Consequently, there is a higher demand for access to public health education. Based on the positive association between public health education and health, our empirical findings suggest that the migrant population’s acceptance of public health education mitigates income-related health inequality.

Regarding mechanisms, healthcare availability and accessibility were explored as potential mediating factors. Medical access, which encompasses availability, accessibility, and other dimensions [43, 44], was operationalized through health records (as an indicator of availability) and family doctor contracts (as an indicator of accessibility). To elaborate, local governments often utilize health records to coordinate public health services for migrant populations, including basic health management and disease prevention [45], which may reflect aspects of medical availability. Similarly, contracted family doctor services could be interpreted as representing long-term care relationships that may facilitate healthcare accessibility by providing consistent medical support.

Public health education appears to serve as a critical intervention for enhancing healthcare access among migrant populations, suggesting multi-level systemic impacts [46]. Through continuous health knowledge dissemination, migrants may not only develop a better understanding of healthcare systems (e.g., health records and family doctor programs) but also potentially acquire improved skills for independently navigating medical services [34]. This dual advancement in knowledge and practical capacity seems to help reduce healthcare barriers associated with information gaps.

For low-income migrants facing systemic healthcare disadvantages, public health education may simultaneously expand coverage of preventive and treatment services (thereby increasing care access) [47] and reduce health disparities through what might be optimized resource allocation and behavioural guidance [48]. This shift could be viewed as more than just expanded service provision—it may substantially restructure healthcare opportunity distribution mechanisms, potentially leading to fairer access to health rights. Our analysis suggests a potential pathway linking public health education to health inequality reduction: public health education → improved medical availability/accessibility → mitigated health disparities.

The following suggestions are proposed in light of the research findings of this study. First, the effectiveness of the public health education supply should be enhanced to alleviate health inequality among the migrant population. The migrant population exhibited a relatively low rate of public health education acceptance. Local grassroots departments should increase the intensity of support for public health education for the migrant population, with a particular focus on mental health education. One way to promote the diversity of public health education for the migrant population is through the scientific development of publicity materials, full utilisation of network information technology to promote personalised health education, and the delivery of free health consultations and educational lectures. Furthermore, it is important to improve the awareness and utilisation rates of various public health education activities among the migrant population. This can enhance individual health literacy and healthcare awareness and ensure the effectiveness of public service provision.

Second, it is important to strengthen and protect the health rights and interests of vulnerable groups and contribute to building a Healthy China. The government and society should adopt effective measures to protect the health rights and interests of economically disadvantaged groups, increase investment in public health education for the migrant population, and allocate public health education resources appropriately towards vulnerable migrant populations. Differentiated and targeted public health education activities should be implemented for different migrant population groups to mitigate health inequality and facilitate the effective implementation of the Healthy China Strategy.

Third, it is important to leverage the functions of health record management and contracted family doctors to enhance the medical availability and accessibility of the migrant population. To improve health management services for the migrant population, electronic health records can be constructed through network platforms. Additionally, the contractual relationships between family doctors and the migrant population should be strengthened to form fixed, normalized, and regular medical service provisions. Local governments in the inflow areas should also strengthen filing and contracting services for the migrant population, providing them with efficient and effective disease prevention and diagnostic services conveniently and quickly, thereby further enhancing their medical availability and accessibility and, ultimately, reducing health inequality among the migrant population.

Strengths and limitations

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, this study expands the literature foundation for promoting a Healthy China by exploring the mitigating mechanisms of health inequality from the perspective of public health education. Second, the edited health inequality indices (EI and WI) were employed to measure health inequality among the migrant population based on the traditional CI. This provides a more comprehensive measurement method for health inequality. Additionally, IV was constructed, and the RIF was introduced to estimate the effects on health inequality for the migrant population. Third, public health education was found to effectively alleviate health inequality among the migrant population by enhancing the availability and accessibility of healthcare services, providing a valuable policy reference for improving China’s public health service system, promoting the construction of a Healthy China, and solidly advancing the collaborative leap toward common prosperity.

While this study systematically investigated the association between public health education and health inequality among China's migrant population, there are several limitations that should be considered. First, this study used cross-sectional survey data, which has certain limitations in the vertical dimension. Second, this study explored the availability and accessibility of healthcare services as mediating variables. However, there may be multiple mediating pathways from other perspectives. Future research could utilize panel data to track individual changes for a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, potential mediating variables, such as social interaction, could be further considered to expand the depth and scope of future research.

Conclusion

This study systematically investigated the association between public health education and health inequality among China's migrant population using data from the 2018 CMDS. The analysis revealed that health inequality among migrants exhibits a pro-rich socioeconomic gradient with significant regional variation. The empirical results indicated that increased participation in public health education programs effectively mitigates health inequality. Specific coefficient estimates indicated that, after addressing endogeneity concerns, migrants receiving two or more types of public health education exhibit a 0.102-unit reduction in the WI, suggesting that the income-related health concentration curve narrowed by approximately 0.474-fold relative to the equality line. Heterogeneity analysis indicated that these associations are stronger among non-interprovincial migrants and self-employed individuals. Mechanistic evidence tentatively suggested that public health education may contribute to inequality reduction primarily through enhancing healthcare availability, with this pathway demonstrating relatively stronger mediating effects compared to improved healthcare accessibility.

Looking to the future, promoting a Healthy China requires improving the health of the migrant population and addressing health inequality. It is crucial to prioritize public health education for this group, accelerate the development of a robust public health system, and promote coordinated development to alleviate health inequality and construct a Healthy China.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- CI

Concentration Index (A health inequality index)

- EI

Erreygers Index (A health inequality index)

- WI

Wagstaff-Erreygers Index (A health inequality index)

- RIF

Recentred Influence Function

- RIF_I

Recentred Influence Function value of a health inequality index I

- RIF-CI

RIF transformations of the health inequality indices CI

- RIF-EI

RIF transformations of the health inequality indices EI

- RIF-WI

RIF transformations of the health inequality indices WI

- RIF-I-OLS

Recentred Influence Function-Index-Ordinary Least Squares

- IV

Instrumental Variable

- CMDS

China Migrants Dynamic Survey

- OLS

Ordinary Least Squares

- 2SLS

Two-Stage Least Squares

Authors’ contributions

D S. Z. and Z Y. L. designed the study and conducted the Data collection. D S. Z. and L Y. C. contributed to the Data analysis and interpretation, Drafting the article and Critical revision of the article. all authors approve the paper to submission, and All authors contributed to the revisions.

Funding

This work was sponsored by National Social Science Youth Fund under Grant (24CRK021), Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX25_0542) and National Bureau of Statistics National Statistical Science Research Project of China (2024LY099).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study design was approved by the ethical review committee of Anhui University of Finance & Economics. All participants gave written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The China Migrants Dynamic Survey 2018 was officially approved for release by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (Population Mobility Dynamics Survey Report, National Statistics [2018] No. 45). Detailed information can be obtained from the following website: https://doi.org/10.12213/11.A000T.202205.84.V1.0. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from all participants during the data collection process. The data used in this study were also approved by the Mobility Service Center of the National Health and Wellness Commission of China. It is important to note that all procedures conducted in this study adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The authors declared that no generative AI or large language models were used in any stage of preparing this manuscript, including but not limited to writing, editing, or data analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The influence function is expressed as:

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang C, Yin J. Public health education and medical seeking behavior of infections diseases of Internet migrants in China. China Econ Quarterly. 2022;2:569–90. 10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2022.02.11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Len C, Zhu Z. Basic Public Health Services for Floating Population in China: Current Situation and Factor Analysis. Reform of Economic System (in Chinese). 2020;06:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pu T, Tang D. A study on the health effect of labor migrant and its mechanism in China. Population J. 2024;46(03):85–100. 10.16405/j.cnki.1004-129X.2024.03.006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black D, Morris JN, Townsend P. Inequalities in health: the black report. Harmondsworth:Penguin 39–233.

- 5.Link BG, Phelan JC. Evaluating the fundamental cause explanation for social disparities in health. Handbook of medical sociology. 2000;5:33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagstaff A, Van Doorslaer E, Watanabe N. On decomposing the causes of health sector inequalities with an application to malnutrition inequalities in Vietnam. J Econ. 2003;112(1):207–23. 10.1016/S0304-4076(02)00161-6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou J, Zhao D. Analysis on the health self-assessment of floating population and its influencing factors in China. Population J. 2020;04:93–102. 10.16405/j.cnki.1004-129X.2020.04.008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou DS, Wen X. Self-employment and health inequality of migrant workers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–13. 10.1186/s12913-022-08340-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu L, Li W, Wang S, Weihua G, Wang X. Research on the health status and influencing factors of the older adult floating population in Shanghai. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1361015. 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1361015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pommier J, Ferron C. Health promotion at last? Trends in French health education over the past decade. Sante Publique (Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, France). 2013;2:s113-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu M, Liu C, Yang M. Effects of public health policies on the health status and medical service utilization of Chinese internal migrants. China Econ Rev. 2020;62:101464. 10.1016/j.chieco.2020.10146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Huang F, Zhou Q. Equality of public health service and family doctor contract service utilisation among migrants in China. Soc Sci Med. 2023;333:116148. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granda ML, Jimenez WG. The evolution of socioeconomic health inequalities in Ecuador during a public health system reform (2006–2014). Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:1–2. 10.1186/s12939-018-0905-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson K, Bambra C, McNamara C, Huijts T, Todd A. The effects of public health policies on population health and health inequalities in European welfare states: protocol for an umbrella review. Syst Rev. 2016;5:1–9. 10.1186/s13643-016-0235-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Y, Ji Y, Chang C, Liverani M. The evolution of health policy in China and internal migrants: continuity, change, and current implementation challenges. Asia Pacific Policy Stud. 2020;1:81–94. 10.1002/app5.294. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang G, Yang D, Wang L, Wang Z, Liang Y, Yang J. Experiences and challenges of implementing universal health coverage with China’s National Basic Public Health Service Program: literature review, regression analysis, and insider interviews. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;7:e31289. 10.2196/31289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths SM, Li LM, Tang JL, Ma X, Hu YH, Meng QY, Fu H. The challenges of public health education with a particular reference to China. Public Health. 2010;4:218–24. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jing R, Zhang H, Hu H. Exploring residents’ healthcare utilization under the family physician contract service system in China: implications for primary healthcare. Health Soc Care Community. 2024;1:2745653. 10.1155/2024/2745653. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu M, Tang Z. Can long-term care insurance alleviate health inequality? Insurance Studies. 2024;04:90–100. 10.13497/j.cnki.is.2024.04.007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.He W, Shen S. Does the integration of urban and rural medical insurance policy alleviate health inequality? evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in prefecture- level cities of China. China Rural Survey. 2021;3:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miao S, Xiao Y. Can In-Situ urbanization alleviate the health inequity of migrants: a study based on MDMS 2014. Urban Development Studies (in Chinese). 2021;28(02):39+116. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng X. Does a different household registration affect migrants’ access to basic public health services in China? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4615. 10.3390/ijerph16234615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):27106. 10.3402/gha.v8.27106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, LaVeist T, Borrell LN, Manderscheid R, Troutman A. Health disparities and health equity: the issue is justice. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):S149–55. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodward A, Kawachi I. Why reduce health inequalities? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(12):923–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gakidou EE, Murray CJ, Frenk J. Defining and measuring health inequality: an approach based on the distribution of health expectancy. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(1):42–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–104. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagstaff A, Van Doorslaer E, Paci P. Equity in the finance and delivery of health care: some tentative cross-country comparisons. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. 1989;5(1):89–112. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erreygers G. Correcting the concentration index. J Health Econ. 2009;28(2):504–15. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagstaff A. Correcting the concentration index: a comment. J Health Econ. 2009;28(2):516–20. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erreygers G, Kessels R. Regression-based decompositions of rank-dependent indicators of socioeconomic inequality of health. Health and inequality. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 2013;21:227–59. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heckley G, Gerdtham UG, Kjellsson G. A general method for decomposing the causes of socioeconomic inequality in health. J Health Econ. 2016;48(7):89–106. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wen Z, Ye B. Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Adv Psychol Sci. 2014;5:731–45. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou D, Cheng L, Wu H. The impact of public health education on migrant workers’ medical service utilization. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15879. 10.3390/ijerph192315879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu H, Feng X. Research status que and prospects: health inequality in the background of “Heaithy China.” Study and Practice (in Chinese). 2018;4:91–8. 10.19624/j.cnki.cn42-1005/c.2018.04.011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cros M. Unlocking Challenges of Universal Health Coverage in Haiti. The Heller School for Social Policy and Management: Brandeis University; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu Y, Qin L. Healthy migrant and salmon bias hypotheses: a study of health and internal migration in China. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:41–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng G, Yang D, Li J. Does migration distance affect happiness? Evidence from internal migrants in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:913553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao J, Zhou D. Effects of self-employment on the health of migrant workers. World Econ. 2021;44:184–204. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grossman M. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J Polit Econ. 1972;80(2):223–55. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Cai J, He Z, Huang Y, Tang G. Current status of migrant health education and its influence factors in China. Chin J Health Educ. 2021;04:291–6. 10.16168/j.cnki.issn.1002-9982.2021.04.001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y, Zhang T, Wang D. Changes in inequality in utilization of preventive care services: evidence on China’s 2009 and 2015 health system reform. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–10. 10.1186/s12939-019-1078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–40. 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deng R. How does the accessibility to health services affect the subjective life quality of migrant workers? Evidence based on thematic survey in key areas of health of migrant population. China Rural Survey. 2022;2:165–84. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vamos S, Okan O, Sentell T, et al. Making a case for “Education for health literacy”: An international perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1436. 10.3390/ijerph17041436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reid JJA. Future of public health. BMJ. 1964;2(5423):1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fagan AA, Bumbarger BK, Barth RP, et al. Scaling up evidence-based interventions in US public systems to prevent behavioral health problems: challenges and opportunities. Prev Sci. 2019;20:1147–68. 10.1007/s11121-019-01048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.