Abstract

Background: Infectious proctitis remains an underrecognized entity, although sexually transmitted diseases, especially bacterial infections, exhibit a marked increase in their incidence. Methods: Here, we report a case of a 44-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with lower abdominal and rectal pain, tenesmus, fever and night sweats for the past 6 days. Results: The computed tomography initially revealed a high suspicion of metastatic rectal cancer. The endoscopic findings showed a 5 cm rectal mass, suggestive of malignancy. The histologic examination showed, however, no signs of malignancy and lacked the classical features of an inflammatory bowel disease, so an infectious proctitis was further suspected. The patient reported to have had unprotected receptive anal intercourse, was tested positive for Treponema pallidum serology and received three doses of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G. A control rectosigmoidoscopy, imaging at 3 months and histological evaluation after antibiotic treatment showed a complete resolution of inflammation. Conclusions: Syphilitic proctitis may mimic various conditions such as rectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease and requires a high degree of suspicion. Clinicians need to be aware of infectious proctitis in high-risk populations, while an appropriate thorough medical history may guide the initial diagnostic steps.

Keywords: proctitis, syphilis, sexually transmitted diseases, rectal ulcer

1. Introduction

Rectal ulcerations are uncommon and underrecognized manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) due to their non-pathognomonic clinical features and inconclusive histopathological findings [1]. However, STDs must be considered in every patient presenting with rectal symptoms, due to the major implications regarding treatment and prognosis [2]. Furthermore, according to the Global Burden of Diseases 1990–2019 analyses, STDs reported a consistent increase in their absolute incidence [3].

During the last decade, in the light of emerging effective HIV treatments, the control of STDs has reached a plateau or may have even worsened for diseases such as syphilis [3,4]. The most commonly transmitted anorectal pathogens are represented by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum and Herpes simplex virus (HSV), out of which T. pallidum reported the most marked increase since 1993 [3,5]. This trend is emphasized in higher income countries with functional screening programs, where there has been a significant rise in the incidence of bacterial infections, namely a 28% increase in gonorrhea and a 74% increase in syphilis, as reported in 2021 in the United States [4]. Syphilis exhibits a markedly high prevalence of up to 7.5% in men who have sex with men (MSM) [6]. Moreover, there are significant synergistic associations in the case of a HIV and syphilis co-infection; HIV weakens the immune system, predisposing to syphilis acquisition while syphilis fragilizes the rectal mucosa making it more vulnerable to HIV acquisition [7]. Infectious proctitis may be asymptomatic in some gonococcal and chlamydia infections [2], or may present as multiple ulcers mimicking an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or even a malignant tumour [8,9]. Based on these aspects, the initial acquisition of a broad personal history is of utmost importance before guiding the first diagnostic steps.

We present a case of syphilitic proctitis in a young man firstly confounded with an advanced rectal carcinoma, highlighting the most important features in the diagnosis of infectious proctitis. Moreover, the aim of our paper is to suggest a possible diagnostic work-up for proctitis and to summarize the most relevant aspects in the differential diagnosis of rectal ulcerations.

2. Case Presentation

A 44-year-old male patient presented to the Emergency Department of our hospital, complaining of a 6-day history of abdominal pain with migratory localisation and tenesmus. Moreover, the patient reported accompanying flu-like symptoms such as fever and malaise as well as night sweats. On the day of presentation, the abdominal pain was mainly localised in the left lower quadrant. The stools were normally formed and coloured; however, they exhibited a high frequency, up to hourly, and were painful. Weight loss was denied by the patient. The medical history was insignificant, revealing only well-controlled asthma. The family history was negative for malignancy as well as for IBD. Upon clinical examination, the patient reported tenderness on palpation in the left lower abdominal quadrant. Vital signs were normal with a blood pressure of 125/79 mmHg, heart rate of 95/min and an oxygen saturation of 97% on room air.

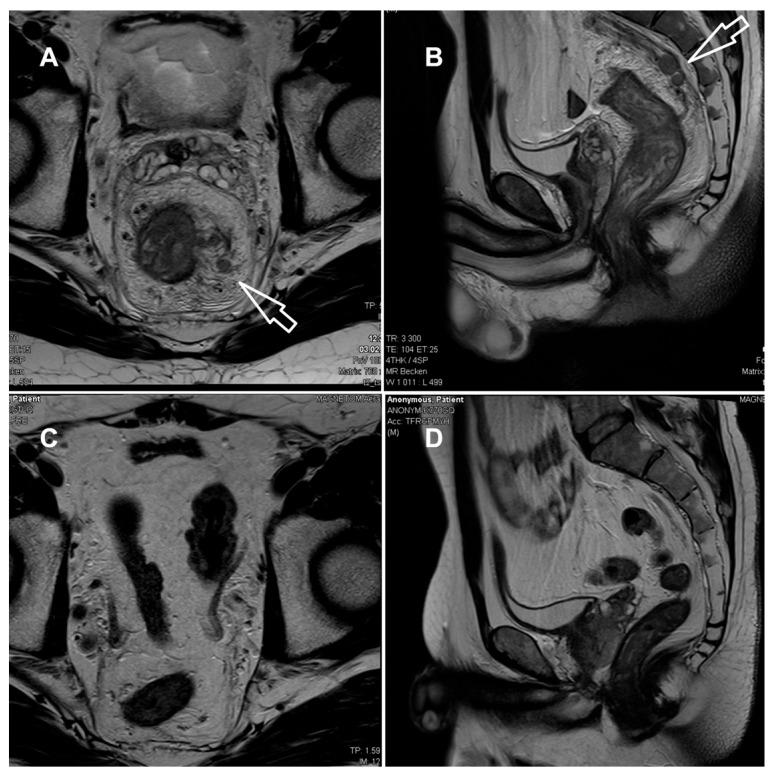

The laboratory parameters showed signs of inflammation with an elevated C-reactive protein of 110 mg/L; a leukocyte count of 4.3 G/L was normal. The computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a high suspicion of rectal carcinoma in the middle and distal third of the rectum with multiple regional and non-regional lymph nodes metastases. The patient was subsequently admitted to hospital and scheduled for a coloscopy with biopsy on the following day. The coloscopy showed a 5 cm tumour in the distal rectum with unremarkable surrounding mucosa in the rest of the colon and terminal ileum (Figure 1A). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis was advised for better definition and further described a semi-circumferential rectal carcinoma with vascular invasion, lymph nodes metastases and possible peritoneal involvement (Figure 2A,B). A CT scan of the thorax was unremarkable. The histological evaluation of the mucosal biopsies showed features of acute inflammation with erosions, cryptic abscesses with focal distribution and crypt destruction; in the lamina propria, there was an increased chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with granulation tissue and epitheloid cell granulomas. There was no architectural disorder or signs of malignancy (Figure 3A,B). The Wartin–Starry stain and T. pallidum immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure 3C,D) highlighted multiple spirochetic bacteria on the mucosal surface in a band-like distribution, without clear evidence of intraepithelial bacteria, as characteristic of T. pallidum infection.

Figure 1.

(A) Semicircular, ulcerating mass at the rectosigmoidal junction with irregular margins, consistent with a neoplastic process, without signs of perforation or obstruction. (B) Complete resolution of inflammation after antibiotic treatment.

Figure 2.

MRI of the rectum at presentation (A,B) and after 3 months (C,D). (A,B) T2-weighted axial (A) and sagittal (B) at initial presentation, showing long-segment, circumferential thickening of the rectal wall (white arrows) with marked mural irregularities, edema, perineural and perivascular infiltration; multiple lymph nodes with irregular shape within and beyond the mesorectal fascia, extending to the external iliac region. Infiltration of the mesorectal fascia and peritoneum with mucosal diffusion restriction. Mild pelvic ascites. Suspected colorectal carcinoma staged as T4a N2b M1 MRF+ EMVI+. (C,D) After antibiotic treatment, complete regression of the rectal wall and mesorectal fascia thickening; regression of edema and no lymphadenopathy. (MRF = mesorectal fascia, EMVI = extramural vascular invasion).

Figure 3.

Histology of rectal biopsies taken before (A–D) and after (E) antibiotic treatment. (A) Colon mucosa with increased chronic active inflammation in the lamina propria, erosions (white arrow) and preserved architecture. (B) Cryptitis and crypt abscesses (black circle). (C,D) Immunohistochemistry for T. pallidum highlights superficially distributed spirochetic bacteria on the mucosal surface (arrow) and in crypt lumina (black arrowhead). (E) Unremarkable colon mucosa post antibiotic treatment. H&E hematoxylin and eosin.

After clinicopathologic correlation of the available investigations, further serologic testing of the patient was performed. The patient reported a history of multiple sexual male partners. Tests for HIV and hepatitis B and C were negative. Both treponemal-specific tests (T. pallidum-hemagglutination-assay = TPHA and T. pallidum-antibodies) and a nontreponemal test (rapid plasma reagin, RPR) were positive. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results of a rectal swab were negative for T. pallidum, N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis and HSV 1/2. Due to the negative T. pallidum-PCR from the rectal swab and lack of previous syphilis testing, which could have helped to estimate the time of infection, we diagnosed a late latent syphilis. Therefore, a treatment with a total of three doses of 2.4 million units of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G (once a week for 3 weeks) was recommended. The patient was symptom-free after the completion of the antibiotic treatment and no Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction was observed. A control rectosigmoidoscopy (Figure 1B), as well as the MRI (Figure 2C,D) at 3 months and the histologic evaluation (Figure 3E) showed a complete resolution of the inflammation.

3. Discussion

Syphilitic proctitis is a rare condition, which requires a high degree of suspicion before diagnosis and can otherwise mimic multiple conditions, extending from IBD to malignant patterns. Our case emphasizes the importance of a broad clinical history before initiating diagnostic steps, usually difficult to be performed in an emergency department. Despite the increasing incidence of STDs, especially of bacterial infections, the infectious proctitis seems to remain underrecognized. Firstly, rectal STD screening among MSM is less frequently performed compared to urethral screening [10]. Previous research showed that sexual health providers were two to six times more likely to perform urethral STD testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia than rectal testing [11]. Since the diagnosis of another STD is one of the most significant predictors of HIV acquisition and asymptomatic carriage is possible, testing for urethral, pharyngeal and rectal STDs should simultaneously be performed [12]. The clinical presentation is in the great majority of cases identical in STD and IBD proctitis, as symptoms such as anal discharge, tenesmus, fever, vomiting or weight loss significantly overlap [13]. Endoscopically, STD proctitis is associated with friable, ulcerated and hyperemic mucosa, which is also encountered in IBD. Moreover, the presence of rectal strictures or masses may indicate signs of malignancy [14,15]. Therefore, the diagnosis is often suspected based on the histologic examination, which fails to identify malignancy or IBD features. Histologically, the STD colitis lacks the IBD features such as cryptic damage, mucosal eosinophilia or presence of granulomas, being characterized by an abundant submucosal and perivascular plasma cell infiltrate [16].

To the best of our knowledge, there are approximately 50 cases of syphilitic proctitis described beginning from the 1960s. A summary of the available cases in the literature published in the last 25 years and their clinical and histological features is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cases of syphilitic proctitis published in the scientific literature.

| No. | Author, Year | Gender, Age | Clinical Presentation | Imagistic Findings |

Endoscopic Findings |

Clinical Diagnosis |

Histology | Laboratory Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hunter, 2025 [15] | Male, 60, MSM |

|

N/A | Due to patient discomfort not performed | Haemorrhoids, suspected HPV and LGV lesions |

|

T. pallidum: TPPA and RPR positive, rectal swab PCR positive HIV negative |

| 2 | Yin, 2024 [17] |

Male, 29 MSM |

|

MRI: rectal wall thickening, inguinal and mesenteric lymphadenopathy |

Nodular, irregular lesions with scattered ulcers and hemorrhage | Rectal carcinoma |

|

Not mentioned |

| 3 | Cantu Lopez, 2024 [18] |

TGW, 49 | Left abdominal pain, non-bloody emesis, weight loss, constipation with mucous | CT: rectal wall thickening, perirectal adenopathy | Erythema, inflammation, thickened rectal folds with near luminal obstruction | Lymphoma, colitis |

|

T. pallidum: RPR/FTA-ABS positive HIV negative |

| 4 | Afzal, 2024 [19] |

Male, 64 MSM |

Significant change in bowel habits, palpable rectal mass | CT: mild rectal wall thickening of the rectum, local lymphadenopathy; MRI: normal |

10-mm elevated rectal lesion with central ulceration, 5–6 cm from the anal verge | Rectal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: EIA and RPR positive HIV negative |

| 5 | Bae, 2024 [20] |

Male, 23 | Right-sided inguinal mass, tenderness in the right inguinal area | CT: inguinal, mesorectal and presacral adenopathy, 10 cm-long circumferential rectal wall thickening | Edematous and hyperemic mucosa, rectal wall thickening | Rectal lymphoma |

Dense infiltration of polymorphic lymphoid cells and histiocytes in the lamina propria with ulcers, increased numbers of plasma cells and eosinophils |

T. pallidum: RPR/FTA-ABS positive HIV negative |

| 6 | Ranabhotu, 2023 [21] |

Male, 72 | Rectal bleeding and pain | N/A | Firm perianal mass | Anal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: RPR/FTA-ABS positive HIV negative |

| 7 | Peine, 2023 [22] |

Male, 38 MSM | Two weeks of obstipation and abdominal pain | CT: large bowel obstruction by a 7 cm × 6.8 cm rectal mass MRI: mesorectal fascia involvement |

Benign-appearing rectal stricture at 2 cm from the anal verge | Rectal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: RPR positive N. gonorrhoeae PCR: positive HIV positive |

| 8 | Alcantara, 2023 [23] |

Male, 35 MSM |

Rectal bleeding, tenesmus | N/A | Rectal ulcers with clean bases and raised edges | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: RPR/FTA-ABS positive C. trachomatis: IgM and IgG positive HIV positive, |

| 9 | Mansilla, 2023 [24] | Male, 40 | Rectal ulceration | Rectal lesion with mesenteric and extra mesenteric adenopathy | Ulcerated rectal vegetating lesion | Rectal carcinoma |

Non-specific polymorphous inflammation |

T. pallidum: serology positive HIV positive |

| 10 | Smith, 2022 [25] |

Male, 39 MSM | Right upper quadrant pain, tenesmus and diarrhoea | CT: short irregular thickening of the rectal wall, mesorectal adenopathy | 2-cm ulcer with heaped margins and a necrotic base in the distal rectum | Metastatic rectal cancer |

Ulceration with chronic inflammation, atypical crypt epithelium, no evident malignant changes |

T. pallidum: RPR positive HIV positive |

| 11 | Cain, 2022 [26] |

Female, 46 | Rectal bleeding | N/A | 1-cm-submucosal mass inside the anal verge | Carcinoid or gastrointestinal stromal tumour | Small lymphocytes infiltrating lamina propria | T. pallidum: antibody test, EIA and RPR negative |

| 12 | Costales, 2021 [27] | Male, 32, MSM | Lower abdominal and rectal pain, diarrhoea with hematochezia for 2 weeks | CT: distal sigmoid and rectal wall thickening, perirectal, pelvic, retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy | Rectal non-bleeding ulcers, friable ulcerated mucosa | STD colitis, later rectal malignancy |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and TPPA positive |

| 13 | Ahmed, 2020 [28] |

Male, 59 MSM |

Fever, rectal pain | PET/CT: intense metabolic activity in the rectum, porta hepatis and internal mammary lymph nodes | 5-cm-rectal mass | Lymphoproliferative process |

|

T. pallidum: RPR positive HIV positive |

| 14 | Patil, 2020 [29] |

Male, 66, MSM | Constipation, abdominal pain | CT: diffuse rectal mucosal thickening, perirectal fat stranding, mesorectal adenopathy |

Two lesions in the distal rectum, edema and erythema | Rectal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: TPPA, RPR and IgM positive HIV positive |

| 15 | Siddiqui, 2020 [30] | Male, 25, MSM | Rectal bleeding, pain, tenesmus, fatigue, weight loss, no night sweats or fever | N/A | Severe ulcerative proctitis, anal fissure | STD or IBD |

|

T. pallidum: RPR positive C. trachomatis: rectal swab PCR positive HIV negative |

| 16 | Kumar, 2019 [31] |

Male, 41 MSM |

6-month-anal pain, no rectal discharge, perianal ulceration | N/A | N/A | STD | N/A |

T. pallidum: VDRL positive C. trachomatis: PCR positive HIV negative |

| 17 | Sousa, 2019 [8] |

Male, 66 MSM |

Rectal bleeding, mucoid discharge, proctalgia and fever | CT: concentric thickening of the distal rectum, densification of the mesorectal fat | Irregularity, edema, hyperemia and mucus in the distal rectal mucosa |

N/A | Inconclusive |

T. pallidum: RPR and antibody test positive C. trachomatis: IgM positive ∙ Rectal swabs inconclusive |

| 18 | Teng, 2018 [32] | Male, 47, MSM | Rectal discharge and bleeding, tenesmus | N/A | Multiple irregular and friable ulcerations | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: VDRL and TPHA positive HIV and hepatitis B positive |

| 19 | Lopez, 2018 [33] |

Male, 48 | Rectal bleeding, tenesmus, popular erythematous rash on the trunk and extremities, inguinal lymph nodes | N/A | Serpiginous ulcers with erythematous and edematous surrounding mucosa | N/A | Acute inflammatory cells spirochetes staining positive |

T. pallidum: serology positive HIV negative |

| 20 | Alcantara, 2018 [34] | Male, 53, MSM | Rectal bleeding, pain and tenesmus, penis ulcers, inguinal adenopathy | N/A | Ulcer covering 70% of the rectal circumference in the distal rectum, well defined and firm edges, ulcer base covered with mucus | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: VDRL non-reactive, FTA-ABS positive HIV positive |

| 21 | Allan, 2018 [35] |

Male, 50 | No symptoms (routine screening) |

N/A | Rectal polyp, nodular areas in the distal rectum (routine screening colonoscopy) | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and TPPA positive HIV positive |

| 22 | Serigado, 2018 [36] | Male, 47, MSM | Rectal bleeding, fatigue, decreased appetite, abdominal pain | CT: left lateral wall thickening in the distal rectum, hypodense hepatic lesions, splenomegaly | One 3-cm, firm, raised and centrally ulcerated mass at the anorectal junction, with irregular borders and bleeding |

Rectal carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma, STD |

|

T. pallidum: VDRL and FTA-ABS positive HIV positive |

| 23 | Diaz, 2017 [37] |

Male, 35 MSM |

Two-week history of intermittent bloody stools |

N/A | Irregular rectal ulcer with a fibrinous surface and friable mucosa | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and TPHA positive HIV positive |

| 24 | Zeidman, 2016 [38] | Male, 33, MSM | Rectal bleeding | N/A | mucosal inflammation of the distal rectum, patchy erythema and edema | Crohn’s disease |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and antibody test positive HIV negative |

| 25 | Gopal, 2015 [39] |

Male, 52 MSM |

Anal canal ulcer | N/A | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: RPR nonreactive, FTA-ABS reactive, PCR perianal swab positive HIV positive |

|

| 26 | Gopal, 2015 [39] |

Male, 44 | Nonhealing anal canal ulcer | N/A | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and FTA-ABS positive HIV unknown |

|

| 27 | Gopal, 2015 [39] |

Male, 51 | Anal canal ulcer | N/A | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and TPPA positive HIV unknown |

|

| 28 | Gopal, 2015 [39] |

Male, 31 MSM |

Anal canal mass and rectal bleeding | N/A | N/A |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and antibody test positive HIV positive |

|

| 29 | Cerreti, 2015 [40] |

Male, 48 MSM |

|

MRI: thickening of the rectal wall, infiltration of the mesorectal fat, lymph nodes in the perirectal fat | Single ulcer with regular edges and lunate shape, occupying one-third of the rectal circumference | Rectal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: serology positive HIV positive |

| 30 | Bensusan, 2014 [41] | Male, 50, MSM | Rectal bleeding, frequent stools | CT: reduction in the rectal caliber, locoregional, abdominal, and inguinal adenopathy | Rectal ulcer with elevated and smooth edges and fibrinous surface | STD |

|

T. pallidum: RPR positive HIV negative |

| 31 | Yilmaz, 2011 [42] | Male, 38, MSM |

|

CT: unremarkable | Hard, ulcerative lesion in distal rectum | Crohn’s disease |

|

T. pallidum: VDRL and FTA/ABS positive HIV negative |

| 32 | Milligan,2010 [43] | Male, 51 MSM |

|

MRI: malignancy features | Findings suggesting rectal malignancy | Rectal carcinoma |

|

Genito-urinary screening positive for T. pallidum |

| 33 | Cha, 2010 [44] | Male, 45, MSM | Anal pain, tenesmus, bloody stools, mucus discharge, inguinal adenopathy | CT: irregular rectal wall thickening, adenopathy MRI: rectal wall thickening, perirectal fat infiltration |

3×4 cm well-demarcated, deep ulcer on the lower rectum extending from the anal canal | Rectal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: RPR and TPPA positive |

| 34 | Zhao, 2010 [45] |

Male, 51 | Anorectal discomfort, tenesmus, mucous discharge and bloody stools, weight loss | CT: local inhomogeneous rectal wall thickening 3 cm from the anal verge | Irregular ulcerated mass, hyperemia and erosion of the rectal wall | Rectal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: TPPA positive Hepatitis B serology positive HIV negative |

| 35 | Furman, 2008 [46] | Male, 28 | Rectal pain | N/A | Ulcerative proctitis | NA | Chronic active colitis with cryptitis and ulceration T. pallidum: Steiner staining positive |

T. pallidum: RPR and FTA-ABS positive HIV positive |

| 36 | Song, 2005 [47] | Male, 30, MSM | Rectal pain and bleeding, tenesmus, inguinal adenopathy | N/A | Two indurated masses of ca. 2 cm in the middle and lower rectum with ulcerated and depressed surface | Rectal carcinoma |

|

T. pallidum: VDRL, FTA-ABS positive HIV negative |

| 37 | Chan, 2003 [48] |

Male, 32, MSM | Rectal discharge, macular rash on the soles, inguinal lymphadenopathy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

T. pallidum: RPR and TPHA positive HIV positive, C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae positive |

CT = computed tomography, EIA = enzyme immunoassay, FTA-ABS = fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, IBD = inflammatory bowel disease, IHC = immunohistochemistry, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, HPV = human papilloma virus, LGV = Lymphogranuloma venereum, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, MSM = men who have sex with men, N/A = not applicable, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, RPR = rapid plasma regain, STD = sexually transmitted diseases, TGW = transgender woman, TPHA= T. pallidum-hemagglutination-assay, TPPA = T. pallidum-particle agglutination, VDRL = Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

Based on the previously published clinical data on STD proctitis, we suggest a possible algorithm, which can guide a reasonable diagnosis in patients presenting with rectal symptoms (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed diagnostic algorithm in patients presenting with rectal symptoms. Created in BioRender. Pop, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ohvs81s. (CMV = cytomegalovirus, CT = computed tomography, FTA-ABS = fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, HIV= human immunodeficiency virus, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, MSM = men who have sex with men, NAAT = nucleic acid amplification test, NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, RAI = receptive anal intercourse, RPR = rapid plasma reagin, STD = sexually transmitted diseases, TPPA = Treponema pallidum particle agglutination, VDRL = Venereal Disease Research Laboratory).

All cases were diagnosed in men and transgender women, initially presenting with symptoms and clinical findings related to rectal malignancy. A first diagnosis of infectious proctitis sparing an elaborate imagistic and histologic work-up was encountered only in cases of HIV-positive MSM or in patients presenting directly to a sexual health service with chronic symptoms [30,31,32,33,34,37].

A thorough medical history before initiating further endoscopic and imagistic diagnosis is important, as the identification of risk factors such as MSM, receptive anal intercourse (RAI) in the last 6 months or HIV seropositive status warrants STD testing [2]. If patients omit or refuse to mention these aspects, then a complete clinical examination could identify the presence of condylomata or anal fissures. Condylomata may sometimes be misdiagnosed as haemorrhoids and in patients presenting with multiple rectal and systemic symptoms a simple diagnosis of haemorrhoids should be doubted [38]. The number and localization of anal fissures matters, as the vast majority of anal fissures are due to mechanic stress, being in 90% of cases located in the posterior midline [49]. The presence of multiple or lateral fissures may indicate systemic disease such as syphilis, HIV, malignancy, Crohn’s disease or tuberculosis [49,50]. An acute presentation with new onset symptoms (fever, severe anal and abdominal pain, vomiting) can pose difficulties in following a specific algorithm, by necessitating an immediate diagnosis. An imagistic scan is not usually recommended as a first-line investigation, as it may lead to false diagnosis, such as rectal malignancy [51]. However, a CT scan may be performed when peritoneal signs are present, in a case in which an endoscopy is contraindicated, or in order to evaluate for possible internally draining abscess, strictures or mucosal ulcerations in the more proximal intestine [1]. Due to its higher costs, MRI is not a standard tool in an emergency department and is therefore performed in a later setting.

When infectious proctitis is suspected, several pathogens must be taken into consideration and simultaneously tested for identifying co-infections. The most prevalent rectal pathogens in MSM are C. trachomatis (average prevalence 9%) and N. gonorrhoeae (average prevalence 6.1%), which are both in the majority of cases asymptomatic; appropriate testing relies on the detection of pathogens by nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) performed from rectal swabs [52]. Lymphogranuloma venereum, caused by the C. trachomatis genovars L1, L2 and L3, is an endemic infection in MSM and usually presents as proctitis with purulent anal discharge, rectal bleeding and pain with possible pelvic lymphadenopathy; the detection of specific C. trachomatis-DNA is diagnostic and should be performed in all MSM with positive C. trachomatis rectal swabs [53]. Testing for rectal M. genitalium is not routinely recommended in MSM, since it has not been significantly associated with the development of proctitis and should be considered only in cases with persistent anal symptoms after excluding other infectious causes [2]. Cytomegalovirus can also cause rectal ulcerations and must always be tested in HIV-positive patients, as it is considered an indicator of advanced disease [2].

A combination of directly identified pathogens on the histologic sample and a positive serologic test is the preferred method for diagnosing an infectious proctitis [54]. In our case, there was no direct evidence of T. pallidum bacteria on the rectal biopsy; however, the lack of malignant and IBD classic features together with the serologic confirmation of an active syphilis indicated the diagnosis of a syphilitic proctitis. A diagnosis of primary rectal syphilis is frequently difficult as the rectal chancre, characteristic of this stage, is painless, superficial and discharges clear secretion. On the other hand, syphilitic proctitis indicates the progression to a secondary syphilis, being accompanied by systemic manifestations like fever or generalized lymphadenopathy [54].

The actual guidelines recommend the use of treponemal screening tests such as TPHA, T. pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA) or enzyme immunoassay (EIA), which are sensitive in detecting early syphilis, but may give false positive results. Nontreponemal tests such as RPR or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) can detect only active syphilis and can miss very early forms of disease. If screening is based on the performance of both a treponemal and nontreponemal test, then the nontreponemal test must be performed quantitatively [54]. It is important to mention that in some patients a negative nontreponemal test may be followed by a positive treponemal test. This is due to an excess of antibodies in the undiluted serum, referred to as the prozone phenomenon in the early stages of syphilis, and is more often encountered in HIV-positive patients [34,39]. In our medical centre, however, a treponemal test is always first performed, and is, when positive, followed by a nontreponemal test. This allows the detection of the disease in early stages and reduces the chance of false negative interpretations due to the prozone phenomenon.

PCR tests are recommended for atypical sites of syphilis, such as oral cavity or rectum, where a distinction from the commensal spirochetes is needed [55]. However, the sensitivity and specificity of PCR in the secondary and latent stages of syphilis remain low, which impairs PCR testing from becoming a routine diagnostic tool. In a study by Shields et al., the sensitivity of PCR swabs in secondary syphilis was 50%, while the specificity was 100% [56]. Another study conducted by Costa-Silva et al. reported a sensitivity of 81% with the same high specificity of 100% [57]. The high chance of false negative PCR swabs in secondary syphilis was partially explained by various research groups based on the following possible hypotheses: the sample collection in routine PCRs usually lacks the required quality for a correct acquisition and the high antibody titres encountered in secondary syphilis impair the development of a high treponemal DNA load in tissue samples [58,59,60]. The direct visualization of spirochetes using dark-field microscopy or Warthin–Starry staining is specific, but difficult to be performed and often provides a false negative result [54]. When serology is negative, the IHC staining has excellent specificity in diagnosing secondary syphilis, but is not part of the routine diagnosis [58].

In our case, the sexual history, lack of malignant features on the histologic sample and the positive T. pallidum serology were considered suggestive and enough for sustaining the diagnosis of syphilitic proctitis, which was later confirmed by the resolution of symptoms under appropriate antibiotic therapy.

4. Conclusions

Syphilitic proctitis, although relatively rare among causes of infectious proctitis, requires a high degree of suspicion in order to avoid clinical overdiagnosis. It may mimic various conditions from IBD to rectal malignancy. Therefore, clinicians must be aware of the increasing incidence of STDs and perform the appropriate screening tests in high-risk populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.P., R.Z. and A.K.-W.; data curation, A.M.P., R.Z., M.C., A.I.G., D.M. and E.M., writing—original draft preparation, A.M.P., A.I.G., D.M. and A.K.-W., writing—review and editing, M.C., E.M., S.P. and A.K.-W., supervision, S.P. and A.K.-W., funding acquisition, A.M.P. and A.K.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the presentation of a single case report.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Wil Hospital.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Struyve M., Meersseman W., Van Moerkercke W. Primary syphilitic proctitis: Case report and literature review. Acta Gastroenterol. Belg. 2018;81:430–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Vries H.J.C., Nori A.V., Kiellberg Larsen H., Kreuter A., Padovese V., Pallawela S., Vall-Mayans M., Ross J. 2021 European Guideline on the management of proctitis, proctocolitis and enteritis caused by sexually transmissible pathogens. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021;7:1434–1443. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng Y., Yu Q., Lin Y., Zhou Y., Lan L., Yang S., Wu J. Global burden and trends of sexually transmitted infections from 1990 to 2019: An observational trend study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022;22:541–551. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinka K. The global burden of sexually transmitted infections. Clin. Dermatol. 2024;42:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2023.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Refugio O.N., Klausner J.D. Syphilis incidence in men who have sex with men with human immunodeficiency virus comorbidity and the importance of integrating sexually transmitted infection prevention into HIV care. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2018;16:321–331. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1446828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuboi M., Evans J., Davies E.P., Rowley J., Korenromp E.L., Clayton T., Taylor M.M., Mabey D., Chico R.M. Prevalence of syphilis among men who have sex with men: A global systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000–20. Lancet Glob. Health. 2021;9:e1110–e1118. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su R., Liu Y., Shan D., Li P., Ge L., Li D. Prevalence of HIV/syphilis co-infection among men who have sex with men in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:1297. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-22499-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sousa M., Pinho R., Rodrigues A. Infectious proctitis due to syphilis and chlamydia: An exuberant presentation. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2019;111:813–814. doi: 10.17235/reed.2019.6175/2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coelho R., Ribeiro T., Abreu N., Gonçalves R., Macedo G. Infectious proctitis: What every gastroenterologist needs to know. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2023;36:275–286. doi: 10.20524/aog.2023.0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoover K.W., Butler M., Workowski K., Carpio F., Follansbee S., Gratzer B., Hare B., Johnston B., Theodore J.L., Wohlfeiler M., et al. STD screening of HIV-infected MSM in HIV clinics. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2010;37:771–776. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e50058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson R.J., Collibee C., Maksut J.L., Earnshaw V.A., Rucinski K., Eaton L. High levels of undiagnosed rectal STIs suggest that screening remains inadequate among Black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2022;98:125–127. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun D.L., Marzel A., Steffens D., Schreiber P.W., Grube C., Scherrer A.U., Kouyos R.D., Günthard H.F., Swiss HIV Cohort Study High Rates of Subsequent Asymptomatic Sexually Transmitted Infections and Risky Sexual Behavior in Patients Initially Presenting With Primary Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;66:735–742. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall R., Patel K., Poullis A., Pollok R., Honap S. Separating Infectious Proctitis from Inflammatory Bowel Disease-A Common Clinical Conundrum. Microorganisms. 2024;12:2395. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12122395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferzacca E., Barbieri A., Barakat L., Olave M.C., Dunne D. Lower Gastrointestinal Syphilis: Case Series and Literature Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021;8:ofab157. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter I., Wang G., Grennan T. Syphilis proctitis: An uncommon presentation of Treponema pallidum mimicking malignancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2025;18:e263948. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2024-263948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold C.A., Roth R., Arsenescu R., Harzman A., Lam-Himlin D.M., Limketkai B.N., Montgomery E.A., Voltaggio L. Sexually transmitted infectious colitis vs inflammatory bowel disease: Distinguishing features from a case-controlled study. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015;144:771–781. doi: 10.1309/AJCPOID4JIJ6PISC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin W., Yan Q., Zhou T., Zhong X. Syphilitic Proctitis Masquerading as Suspected Rectal Cancer. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2024;33:306. doi: 10.15403/jgld-5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantu Lopez C., Herrera-Gonzalez S., Shamoon D., Dacosta T.J., Bains Y. The Great Mimicker Gets Caught: A Rare Case of Syphilis in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Cureus. 2024;16:e59222. doi: 10.7759/cureus.59222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afzal Z., Hussein A., O’Donovan M., Bowden D., Davies R.J., Buczacki S. Diagnosis and management of rectal syphilis-case report. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024;2024:rjac102. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjac102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae H., Cho J., Kim H.J., Jang S.K., Na H.Y., Paik J.H. Primary Rectal Syphilis Mimicking Lymphoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Korean Soc. Radiol. 2024;85:801–806. doi: 10.3348/jksr.2023.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranabhotu A., Habibian N., Patel B., Farrell E., Do J., Sedghi S., Sedghi L. Case Report: Resolution of high grade anal squamous intraepithelial lesion with antibiotics proposes a new role for syphilitic infection in potentiation of HPV-associated ASCC. Front. Oncol. 2023;13:1226202. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1226202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peine B., Ved K.J., Fleming T., Sun Y., Honaker M.D. Syphilitic proctitis presenting as locally advanced rectal cancer: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023;107:108358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.108358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alcántara-Figueroa C.E., Calderón Cabrera D.C., Estela-Vásquez E.F., Coronado-Rivera E.F., Calderón-De la Cruz C.A. Rectal syphilis: A case report. Rev. Gastroenterol. Mex. (Engl. Ed.) 2023;88:186–188. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmxen.2023.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansilla S., Pouy A., Domínguez F., Misa R. Rectal syphilis. Cir. Esp. (Engl. Ed.) 2023;101:214. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2022.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith M.J., Ong M., Maqbool A. Tertiary syphilis mimicking metastatic rectal cancer. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022;2022:rjac093. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjac093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cain D.D., Martin K., Gibson B. Rectal Tonsil in a Patient With Positive Syphilis Serology. Cureus. 2022;14:e23812. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costales-Cantrell J.K., Dong E.Y., Wu B.U., Nomura J.H. Syphilitic Proctitis Presenting as a Rectal Mass: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021;36:1098–1101. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06414-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sohail Ahmed D., Poliquin M., Julien L.A., Routy J.P. Extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma recurring with syphilis in an HIV-infected patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e235204. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-235204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patil R.V., Stephenson I., Richards C.J., Griffin Y. Rectal cancer mimic: A rare case of syphilitic proctitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e235522. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-235522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiqui W.T., Schwartz H.M. Infectious Proctitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1906077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar N., Bahadur T., Agrawal S.K. Concurrent syphilis and Chlamydia trachomatis infection in bisexual male: A rare case of proctitis. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care. 2019;8:1495–1496. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_43_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng K.T., Lee Y.J., Chang C.C. An Easily Overlooked Cause of Mucus and Bloody Material Passage During Defecation in a 47-Year-Old Man. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:e3–e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López Álvarez M., Souto Ruzo J., Guerrero Montañés A. Rectal syphilitic ulcer. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2018;110:597. doi: 10.17235/reed.2018.5592/2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alcántara Figueroa C., Nuñez Calixto N., Vargas Cárdenas G., Chian García C. Rectal syphilis in a HIV patient from Peru. Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru. 2018;38:381–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allan-Blitz L.T., Beaird O.E., Dry S.M., Kaneshiro M., Klausner J.D. A Case of Asymptomatic Syphilitic Proctitis. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2019;46:e68–e69. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serigado J., Lewis E., Kim G. Rectal bleeding caused by a syphilitic inflammatory mass. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e226595. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-226595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Díaz-Jaime F., Satorres Paniagua C., Bustamante Balén M. Primary chancre in the rectum: An underdiagnosed cause of rectal ulcer. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2017;109:236–237. doi: 10.17235/reed.2017.4457/2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeidman J.A., Shellito P.C., Davis B.T., Zukerberg L.R. Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 25-2016. A 33-Year-Old Man with Rectal Pain and Bleeding. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:676–682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1602815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gopal P., Shah R.B. Primary Anal Canal Syphilis in Men: The Clinicopathologic Spectrum of an Easily Overlooked Diagnosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2015;139:1156–1160. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0487-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pisani Ceretti A., Virdis M., Maroni N., Arena M., Masci E., Magenta A., Opocher E. The Great Pretender: Rectal Syphilis Mimic a Cancer. Case Rep. Surg. 2015;2015:434198. doi: 10.1155/2015/434198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grilo Bensusan I., Gómez-Regife L. Primary syphilitic chancre in the rectum. Endoscopy. 2014;46:E533. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yilmaz M., Memisoglu R., Aydin S., Tabak O., Mete B., Memisoglu N., Tabak F. Anorectal syphilis mimicking Crohn’s disease. J. Infect. Chemother. 2011;17:713–715. doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milligan R., Dent B., Hoare T., Henry J., Katory M. Gummatous rectal syphilis imitating rectal carcinoma. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:1269–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cha J.M., Choi S.I., Lee J.I. Rectal syphilis mimicking rectal cancer. Yonsei Med. J. 2010;51:276–278. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.2.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao W.T., Liu J., Li Y.Y. Syphilitic proctitis mimicking rectal cancer: A case report. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2010;1:112–114. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v1.i3.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furman D.L., Patel S.K., Arluk G.M. Endoscopic and histologic appearance of rectal syphilis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2008;67:161. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song S.H., Jang I., Kim B.S., Kim E.T., Woo S.H., Park M.J., Kim C.N. A case of primary syphilis in the rectum. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2005;20:886–887. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.5.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan D.J., Michelmore H.M., Gold J. A diagnosis unmasked by an unusual reaction to ceftriaxone therapy for gonorrhoeal infection. Med. J. Aust. 2003;178:404–405. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNeil C.J., Barroso L.F., 2nd, Workowski K. Proctitis: An Approach to the Symptomatic Patient. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2024;108:339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2023.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herzig D.O., Lu K.C. Anal fissure. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2010;90:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guniganti P., Lewis S., Rosen A., Connolly S., Raptis C., Mellnick V. Imaging of acute anorectal conditions with CT and MRI. Abdom. Radiol. 2017;42:403–422. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0982-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dewart C.M., Bernstein K.T., DeGroote N.P., Romaguera R., Turner A.N. Prevalence of Rectal Chlamydial and Gonococcal Infections: A Systematic Review. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2018;45:287–293. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Vries H.J.C., de Barbeyrac B., de Vrieze N.H.N., Viset J.D., White J.A., Vall-Mayans M., Unemo M. 2019 European guideline on the management of lymphogranuloma venereum. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019;33:1821–1828. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Janier M., Unemo M., Dupin N., Tiplica G.S., Potočnik M., Patel R. 2020 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021;35:574–588. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Hernandez D., Vall-Mayans M., Coll-Estrada S., Naranjo-Hans L., Armengol P., Iglesias M.A., Barberá M.J., Arando M. Human intestinal spirochetosis, a sexually transmissible infection? Review of six cases from two sexually transmitted infection centres in Barcelona. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2021;32:52–58. doi: 10.1177/0956462420958350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shields M., Guy R.J., Jeoffreys N.J., Finlayson R.J., Donovan B. A longitudinal evaluation of Treponema pallidum PCR testing in early syphilis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012;12:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costa-Silva M., Coutinho D., Sobrinho-Simões J., Azevedo F., Lisboa C. Cross-sectional study of Treponema pallidum PCR in diagnosis of primary and secondary syphilis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018;57:46–49. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luo Y., Xie Y., Xiao Y. Laboratory Diagnostic Tools for Syphilis: Current Status and Future Prospects. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;10:574806. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.574806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Golden M., O’Donnell M., Lukehart S., Swenson P., Hovey P., Godornes C., Romano S., Getman D. Treponema pallidum Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing To Augment Syphilis Screening among Men Who Have Sex with Men. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57:e00572-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00572-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou C., Zhang X., Zhang W., Duan J., Zhao F. PCR detection for syphilis diagnosis: Status and prospects. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019;33:e22890. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.