Highlights

-

•

Bacillus siamensis produced levan yield of 15.74 % (w/v) in a batch bioreactor.

-

•

B. siamensis yielded 17.96 % (w/v) levan in a continuous stirred-tank system.

-

•

X-ray diffraction revealed the amorphous structure of the levan.

-

•

Sucrose had a significant impact on levan production by B. siamensis.

Keywords: Levan, Bacillus siamensis, Bioreactor, Response surface methodology, Continuous stirred tank bioreactor

Abstract

Levan, a promising fructan polysaccharide for biopharmaceuticals, has limited large-scale production studies. This research optimized and scaled up levan biosynthesis from Bacillus siamensis in continuous stirred-tank bioreactors based on response surface methodology (RSM). Batch cultures optimized for 30 % (w/v) sucrose, pH 5.0, and 48 h incubation yielded a maximum 15.74 % (w/v) levan. The optimal batch conditions were evaluated in a continuous stirred-tank bioreactor, where dilution rates and mixing speeds were examined. At a dilution rate of 0.021 h⁻¹ and an agitation speed of 200 rpm, the maximum productivity was 17.96 % (w/v), and steady-state conditions were attained after three days of continuous fermentation. X-ray diffraction confirmed the amorphous nature of the levan, ideal for biomaterial applications. These results underline the potential of B. siamensis for high-yield levan production and provide a systematic approach for bioprocess parameter optimization, serving as a strong basis for its increased application in industrialized polysaccharide-based bioprocessing.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Levan, a fructan polysaccharide, has attracted considerable interest due to its distinctive its structural and functional characteristics, which are characterized by β-(2,6)-glycosidic bonds along the main chain and β-(2,1)-glycosidic bonds in the branches. Levan is a fructan-type polysaccharide, and its molecular weight, degree of polymerization (DP), and viscosity depend heavily on its source (microbial vs. plant) and the conditions of synthesis [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. In addition to its chemical characteristics, stirring the levan in water and precipitating it with 75 % alcohol allows the polysaccharide to be purified and separated [[7], [8], [9]]. Most of the microbial levans are produced by different species of bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis [10], Zymomonas mobilis and Gluconobacter japonicus LMG 1417 [11], B. aryabhattai [12], and B. siamensis [13]. These exhibit physicochemical properties with a wide applicability range and can be commercially manufactured at a large scale for industrial applications.

Levan has many uses across multiple industries, including food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. It can serve as a medium for beneficial gut microbiota in the food industry, a stabilizer, and an adhesive agent in many formulations [[14], [15], [16]]. Levan has also been reported by various studies for its antitumor [17], anticancer and anti-inflammatory [[18], [19], [20]] applications as one of the promising biomaterials for therapeutic use [[21], [22], [23]]. These different uses highlight the significance of levan in the development of new biomaterials and the facilitation of pharmaceutical innovation [[24], [25], [26], [27], [28]].

The optimization of microbial levan production remains an important of research focus due to its industrial significance. In a prior study, the researchers isolated B. siamensis from Thai traditional fermented soybeans, and the B. siamensis levansucrase demonstrated the ability to produce levan in a sucrose medium [13]. Related studies have attempted to investigate different parameters (carbon and nitrogen sources, pH, fermentation dynamics) to improve levan yields, although the outcomes vary. For example, Pseudomonas fluorescens produced 0.86 g/L of levan with optimized parameters of sucrose and yeast extract concentration using a central composite design (CCD) [5]. Likewise, after 14 h of fermentation, B. subtilis var. natto produced 41.44 g/L of levan with 250 g/L sucrose [29]. The efficacy of CCD in enhancing yields was also illustrated through optimizations where Z. mobilis produced up to 40.20 g/L of levan under ideal sucrose, pH, and incubation conditions [14]. Halomonas elongata also achieved optimal levan yields via statistical optimization for use in pharmaceuticals [30].

However, there are very few studies on B. siamensis, a potential levan producer. Further studies are needed to capitalize on its industrial applications [13,31]. Hence, the structural features of the levan must be mapped out to obtain a high yield of levan to satisfy demand in applications. As with other single bacterial polysaccharides, the determination of levan structure is of great significance to improve levan production efficiency. In this study, a response surface methodology (RSM) approach was used to evaluate the effect of sucrose concentration, initial pH, and incubation time on the production of levan by B. siamensis in a batch-stirred tank bioreactor. High productivity is essential, and this work illustrates how to explore and characterize the ideal conditions for levan biosynthesis and the potential for scaling up levan production in continuous bioreactor systems. A complete approach and robust framework related to B. siamensis were included in this research to improve levan production, address production challenges, and facilitate its industrial application.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microorganism

The bacterium B. siamensis was isolated from fermented soybeans through established protocols and identified using molecular analysis of its 16S rDNA gene sequences, as described in our previous studies [13,32]. The facultative, rod-shaped, and gram-positive bacterium forms creamy-white colonies, which measure 3–4 mm in diameter [33]. Furthermore, its high industrial value has been widely recognized [34], particularly due to its unique ability to produce levan and other exopolysaccharides. In addition, the isolate was cultured on nutrient agar plates (HIMEDIA, India) at 4 °C, and was subcultured weekly to ensure the viability and repeatability of the experiments [35].

2.2. Inoculum preparation

B. siamensis was routinely grown from glycerol stock on nutrient agar medium (HIMEDIA, India), containing peptone (5 g/L), NaCl (5 g/L), yeast extract (1.5 g/L), agar (15 g/L), and beef extract (1.5 g/L), and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h [36]. A colony was isolated and inoculated into 100 mL of sterilized inoculum medium (50 g/L sucrose, 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl; pH 6.0, adjusted with 0.1 M HCl or NaOH) in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask and incubated with shaking at 200 rpm at 37 °C for 24 h. After the incubation, the optical density (OD600) of biomass was measured using a UV–visible light spectrophotometer at 600 nm [23]. To prepare the inoculum, this protocol was standardized to establish homogeneous and comparable conditions for the start of the fermentation experiment. This approach aligns with accepted techniques, which provided the ideal microbiological growth environment to be used for B. siamensis [7,24,29].

2.3. Fermentation conditions and statistical analysis

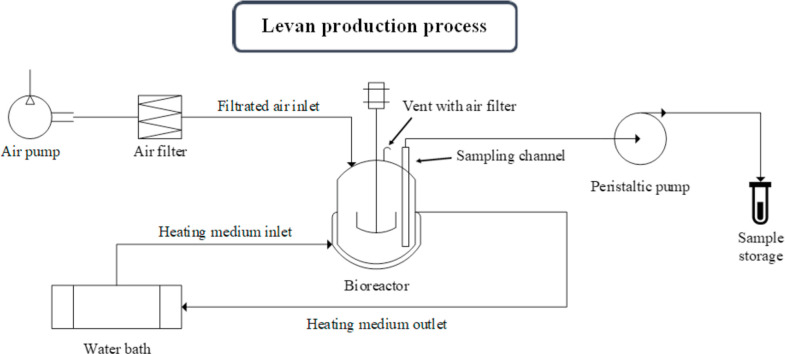

The sterilized fermentation medium was composed of 10 %–30 % (w/v) sucrose, 3.5 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.8 g/L NaH2PO4, 0.2 g/L MgSO4, 3.5 g/L NaNO3, and 5 g/L yeast extract. The pH value was adjusted to 5–7 using 0.1 M HCl or NaOH. Using a 1 L stirred tank bioreactor (20 cm height, 8.5 cm diameter) with a 0.5 × 3.5 cm two-blade impeller, each bath experiment was inoculated with 10 % (v/v) of subculture, which represented 200 mL of a working volume. Air was filtered through a 0.2 µm air filter and bubbled into the bioreactor. The bioreactor was run at 37 °C using a cooling jacket and recycling water (water bath) with an agitation speed of 200 rpm. Fig. 1 shows a schematic of the bioreactor and cultivation system. For the levan quantity results, design runs were prepared with the aid of Minitab® for Windows (version 21.1; Minitab, LLC., Pennsylvania, USA) for each experiment. Table 1 displays the coded parameters and the level used for the experiment. The experiments were performed applying Central Composite Design (CCD) (α = 1) to test the three factors at three levels. The three levels were −1, 0, and +1 corresponding to the lowest, central, and highest points, respectively [14]. The fermentation condition parameters, including sucrose concentrations, initial pH, and incubation time, were adjusted according to the design of a plan experiment (Table 2). A total of 20 experiments with three replications were performed to ensure accuracy and precision. B. siamensis growth was assessed by measuring the optical density at 600 nm with a UV-visible spectrophotometer.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of bioreactor and cultivation system.

Table 1.

Coded parameters and their levels used for the experiment.

| Factors | Symbols | Unit | −1 | 0 | +1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose concentration | X1 | % (w/v) | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| pH | X2 | – | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 |

| Incubation time | X3 | h | 24 | 36 | 48 |

Table 2.

Experimental design results in levan quantity produced by B. siamensis.

| Std | Run | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Observed response | Predicted response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1: Sucrose concentration ( % (w/v)) | X2: pH | X3: Incubation Time (h) | Levan ( % (w/v)) | Levan ( % (w/v)) | ||

| 16 | 1 | 20 | 6.0 | 36 | 9.04 | 9.59 |

| 19 | 2 | 20 | 6.0 | 36 | 9.04 | 9.59 |

| 17 | 3 | 20 | 6.0 | 36 | 8.98 | 9.59 |

| 4 | 4 | 30 | 7.0 | 24 | 13.78 | 13.83 |

| 8 | 5 | 30 | 7.0 | 48 | 13.44 | 14.08 |

| 1 | 6 | 10 | 5.0 | 24 | 4.79 | 4.28 |

| 11 | 7 | 20 | 5.0 | 36 | 7.93 | 8.76 |

| 20 | 8 | 20 | 6.0 | 36 | 9.85 | 9.59 |

| 12 | 9 | 20 | 7.0 | 36 | 10.46 | 9.14 |

| 2 | 10 | 30 | 5.0 | 24 | 14.87 | 14.71 |

| 5 | 11 | 10 | 5.0 | 48 | 5.44 | 5.52 |

| 14 | 12 | 20 | 6.0 | 48 | 11.34 | 10.58 |

| 3 | 13 | 10 | 7.0 | 24 | 6.18 | 6.51 |

| 10 | 14 | 30 | 6.0 | 36 | 14.86 | 14.55 |

| 18 | 15 | 20 | 6.0 | 36 | 9.87 | 9.59 |

| 9 | 16 | 10 | 6.0 | 36 | 6.06 | 5.88 |

| 6 | 17 | 30 | 5.0 | 48 | 15.74 | 15.54 |

| 13 | 18 | 20 | 6.0 | 24 | 9.56 | 9.84 |

| 15 | 19 | 20 | 6.0 | 36 | 9.72 | 9.59 |

| 7 | 20 | 10 | 7.0 | 48 | 6.87 | 7.16 |

The response surface model was fitted to respond to the levan concentration in relation to the sucrose concentration, pH, and incubation time. The relationship between levan concentration and the dependent parameters was observed using the quadratic equation, which is given by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where β0 is the constant value representing the average value of Y, β1, …, β23 represent the first order, quadratic, and interaction coefficients, respectively [14,37].

2.4. Levan and residue sugar analysis

After fermentation, 2 mL samples were taken to analyze levan and residual sugar. Centrifugation was done at 9100 × g for 1 h, followed by separation of the supernatant, which was then boiled at 100 °C for 10 min to inactivate enzymes [7]. Residual sugars present in the supernatant were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Luna NH2 column (Phenomenex, California, USA) and a refractive index (RI) detector. The mobile phase was 80 % HPLC-grade acetonitrile, and the flow rate was maintained at 1 mL/min. The injection volume and the column temperature were 10 µL and 40 °C, respectively [38].

The concentration of levan was measured using a TSKgel Amide-80 gel-permeation column (TOSOH, Tokyo, Japan) under the same conditions as those for the analysis of residual sugar [39]. The combination of these two parameters allowed us to directly quantify levan and unconsumed sugar, a crucial measurement for evaluating fermentation efficiency.

2.5. Bacterial growth

Samples for monitoring the growth of B. siamensis during the bioreactor fermentation were taken at 0, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h of incubation. Each 3 mL sample was centrifuged for 1 hour at 9100 × g to separate the cells. Furthermore, the resulting pellet was rinsed twice with normal saline and resuspended in the same solution. Additionally, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was read by ultraviolet-visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometer. Based on this measure, microbial growth was accurately determined to monitor the accumulation of the biomass during fermentation [40,41].

2.6. Levan purification

Levan was then purified to allow for downstream applications and to guarantee its quality after the fermentation process [13,32]. Residual bacterial cells were isolated from the bioreactor culture by centrifugation (9100 × g for 1 hour). To inhibit the enzymatic action, the obtained supernatant was heated at 100 °C for 10 min [42]. For Levan precipitation, a twofold volume of cold absolute ethanol (−20 °C) was introduced, and subsequently, the mixture was stored at 4 °C for 24 h for precipitation.

The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 9100 × g for one hour and resuspended in deionized water [43]. To obtain a more purified levan and to eliminate lower-molecular-weight impurities, the solution was dialyzed using a Spectra/Por dialysis membrane (MWCO: 12–14 kDa) for an additional three days [44]. The dialysate underwent another round of ethanol precipitation, and the pellet was washed with deionized water and lyophilized. A high-purity levan suitable for structural and functional studies was obtained by a multi-step purification protocol.

2.7. X-ray diffraction analysis

Purified levan was subjected to X-ray diffraction (XRD) [13,25], which helped to achieve an overview regarding its material properties, and possible applications. The analysis was carried out using a Bruker AXS D2 PHASER system (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), with Ni filtered Cu Kβ radiation operating at 30 kV and 10 mA. A 2θ scattering angle range of 5–80° was used, with a step interval of 0.025° and 20 s counting per step. This apparatus allowed for accurate determination of the amorphous or crystalline status of the levan.

2.8. Scaling up of levan production in continuous stirred tank bioreactor

Furthermore, the scale-up levan production via B. siamensis was performed in a one-liter lab-scale continuous stirred-tank bioreactor. Silicone tubing (sterilized) was used to link the inlet and outlet feed systems with the aid of peristaltic pumps. For pre-cultivation, inoculation in the bioreactor was carried out using 10 % (v/v) inoculum with a working volume of 780 mL. The batch phase was run according to response surface methodology (RSM) (i.e., optimal sucrose concentration, pH, and incubation time) under ideal conditions. At this stage, the bioreactor was operated without a feed system at 37 °C and 200 rpm for 48 h [23,34].

After the batch phase, the bioreactor was switched to continuous operation to investigate the effect of different dilution rates (0.021, 0.028, and 0.042 h⁻¹) on levan production. The steady-state was defined when the cell density, levan concentration, and residual sucrose reached a point of balance [14]. This, in turn, guaranteed a consistent operation of the system, supplying accurate data to assess production efficiency. To improve and optimize levan yield, the influence of agitation speeds (100, 200, and 300 rpm) was investigated at the optimal dilution rate established by RSM analysis. These varying speeds were applied to the continuous system to determine their impact on mixing efficiency, substrate utilization, and overall production.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The effect of sucrose concentration on growth of B. siamensis

In a 1 L bioreactor with a working volume of 200 mL, the impact of different sucrose concentrations on B. siamensis growth was assessed. Fermentation was performed for 48 h at controlled conditions: 37 °C, pH 6.0, and agitation speed of 200 rpm. The samples were centrifuged, washed, and resuspended in normal saline, and optical density reading (at 600 nm) determined biomass. Fig. 2 summarizes growth trends across sucrose concentrations.

Fig. 2.

The growth of B. siamensis in a fermentation medium containing various sucrose concentrations with agitation speed of 200 rpm at pH 6.0 and 37 °C for 48 h.

The finding shows that biomass production was maximized at a sucrose concentration of 10 % (w/v), suggesting that this was the best condition for B. siamensis proliferation. In this study, a significant decrease in cell growth was detected with increasing sucrose concentration, corroborating prior reports by Belghith et al. [45] and the thermophilic Bacillus species in their study had reduced growth rates at increasing sucrose concentrations. Their study, in particular, noted reducing cell concentrations at 5 % (w/v) sucrose, which decreased dramatically by a concentration of 40 % (w/v).

The observed inhibition at high concentrations of sucrose can be explained by osmotic stress, which negatively affects cell metabolism and hinders microbial growth [46]. However, we have to keep in mind that elevated sucrose levels are in fact known to stimulate levansucrase activity, playing a role in levan synthesis [16]. Such enzymatic stimulation may compensate for the drop in biomass due to higher levan production rates reported in previous studies [14,45,47].

3.2. Kinetics of levan synthesis by B. siamensis in batch bioreactor culture

The kinetics of B. siamensis-produced levan were evaluated in a batch bioreactor under different concentrations (10 %–30 % (w/v)) of sucrose. Fermentation at pH 6 and 37 °C was carried out with aeration and agitation at 200 rpm for 48 h. Fig. 3 shows the concentrations of levan and residual sucrose throughout fermentation, which reveals a complex interplay between substrate utilization and product formation.

Fig. 3.

Kinetics of sucrose consumption and levan production by B. siamensis with fermentation medium containing 10, 20, and 30 % (w/v) of sucrose with agitation speed of 200 rpm at pH 6.0 and 37 °C for 48 h.

There was a rapid consumption of sucrose between 6 and 12 h of incubation, which coincided with an increase in cellular mass (as indicated by OD600 in the Fig. 2). This, in part, would explain the active growth of B. siamensis during the exponential growth period when sucrose consumption was at its highest. Elevated initial sucrose levels resulting in residual sucrose after fermentation (20 % and 30 % (w/v)) showed a trend also seen in Z. mobilis, where high initial sucrose concentrations resulted in incomplete substrate utilization as a mechanism of osmotic tolerance [14].

The strongest levan synthesis occurred within the initial 24 h of fermentation, followed by increased synthesis, which plateaued as sucrose became less accessible in the medium. Accordingly, in the 20 % (w/v) sucrose medium, the levan concentration also dropped slightly after 36 h. This might be a consequence of acid hydrolysis caused by the accumulation of fermentation by-products, as observed previously in Vieira et al. [29], Hassan and Ibrahim [47], and Bekers et al. [48] studies. Results of the study showed that the highest levan yield (15.01 % (w/v)) was retrieved after a 48-hour period of incubation in a medium containing 30 % (w/v) sucrose. This outcome emphasizes the importance of balancing the sucrose concentration to optimize substrate utilization and levan production. Sucrose, at high levels, can stimulate more production and can relate to unproductiveness as residue sugar and hydrolytic degradation [14,47].

3.3. Optimization of levan biosynthesis

Using response surface methodology (RSM), the optimal conditions for levan biosynthesis by B. siamensis were examined with respect to the sucrose concentration (X1), the initial pH of the culture medium (X2), and the incubation time (X3). The highest levan concentration (15.75 % (w/v)) was obtained from conditions consisting of sucrose 30 % (w/v), pH 5.0, and the overnight incubation period (48 h), using 20 experimental trials (Table 2). The exceeded level was used to verify the model, which was provisionally found to be in agreement with a predicted levan yield of 15.54 % (w/v). This showed good agreement with the mean value of levan concentration and supported the accuracy of the model [32].

The regression model was validated with ANOVA statistical analysis. The high degree of correlation (R2 = 0.9741) indicated that 97.41 % of the variability in levan production was explained by the model. The lack of fit was insignificant (p > 0.05), which confirms that the developed model reasonably well represented the experimental data [14,47].

| (2) |

To describe levan production, a quadratic equation was applied. ANOVA results (Table 3) indicated sucrose concentration (X1) as the most significant factor (p < 0.05). Furthermore, there was a significant (p < 0.05) interaction between sucrose concentration and initial pH, indicating that these two parameters exhibited a synergistic effect on levan production [7].

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and regression coefficients for model regression representing levan production (R2 = 0.9741).

| Source | DFa | Coefficient | Seq SSb | Adj MSc | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 9 | 198.235 | 22.026 | 41.78 | <0.001 | |

| Constant | −28.6 | <0.001 | ||||

| Linear | 3 | 189.639 | 63.213 | 119.91 | <0.001 | |

| Sucrose conc. | 1 | 0.677 | 187.922 | 187.922 | 356.48 | <0.001 |

| pH | 1 | 9.79 | 0.384 | 0.384 | 0.73 | 0.413 |

| Time | 1 | −0.190 | 1.332 | 1.332 | 2.53 | 0.143 |

| Square | 3 | 3.522 | 1.174 | 2.23 | 0.148 | |

| Sucrose conc. × Sucrose conc. | 1 | 0.00631 | 1.096 | 1.096 | 2.08 | 0.180 |

| pH × pH | 1 | −0.634 | 1.104 | 1.104 | 2.09 | 0.178 |

| Time × Time | 1 | 0.00432 | 1.062 | 1.062 | 2.01 | 0.186 |

| Interaction | 3 | 5.074 | 1.691 | 3.21 | 0.070 | |

| Sucrose conc. × pH | 1 | −0.0776 | 4.821 | 4.821 | 9.14 | 0.013 |

| Sucrose conc. × Time | 1 | −0.00084 | 0.082 | 0.082 | 0.16 | 0.702 |

| pH × Time | 1 | −0.0122 | 0.171 | 0.171 | 0.32 | 0.581 |

| Residual error | 10 | 5.272 | 0.527 | |||

| Lack of fit | 5 | 4.312 | 0.862 | 4.49 | 0.062 | |

| Pure error | 5 | 0.960 | 0.192 | |||

| Total | 19 | 203.506 |

Response surfaces and contour plots were drawn using visual analyses through Minitab® software (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6). Complimentary insights into the interplay of the variables are also presented. Varying the initial pH using these plots indicated that maximum levan production was observed at the highest incubation time with 30 % (w/v) sucrose, but with decreasing levels above the initial pH set at 5.0 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Response surface plot (a) and contour plot (b) for levan concentration against variation of incubation time and initial pH with constant initial sucrose concentration (30 % (w/v)).

Fig. 5.

Response surface plot (a) and contour plot (b) for levan concentration against variation of sucrose concentration and incubation time with constant initial pH (5.0).

Fig. 6.

Response surface plot (a) and contour plot (b) for levan concentration against variation of sucrose concentration and initial pH with constant incubation time (48 h).

The 3D surface plot and corresponding contour plot (Fig. 5) emphasized the key role of sucrose concentration in promoting levan production. Although levan yield significantly grows with increasing sucrose content, the marginal effect of incubation time indicates that shorter incubation times can be used in an industrial context to enhance economic feasibility [39].

The interaction of sucrose concentration and initial pH was further explored by fixing the incubation time to 48 h (Fig. 6), demonstrating that levan yield increases were proportional to sucrose levels between 10 % and 30 % (w/v). These results are in agreement with studies on Enterococcus faecium MC-5, which showed a linear relationship between the concentration of sucrose and the level of levan produced [15]. Nevertheless, levan production started to decrease from 30 % (w/v) sucrose, a trend that has also been reported in other bacterial systems [14].

Sucrose is essential for levan production, acting as a precursor that, through the enzyme levansucrase, leads to levan formation. Higher sucrose concentrations generally boost levansucrase production and enhance the process of transfructosylation, which directly increases levan yield. Furthermore, a critical observation has revealed that sucrose concentrations exceeding a certain threshold can paradoxically impede bacterial proliferation, underscoring the necessity of a finely tuned equilibrium for maximizing production [49]. The optimum pH for levan production depends on the bacterial strain and varies over a wide range of pH. Levan produced by B. amyloliquefaciens KKSB7 levansucrase was potentially synthesized within a pH range of 6.0–8.0, while the activity of B. velezensis KKSB6 levansucrase dropped when pH increased from 6.0 to 8.0 [49]. Other strains, such as Calidifontibacillus erzurumensis LEV207, secreted levansucrase that had potential for levan production at a pH of 5.0–8.0, but its activity massively decreased when the pH was lower than 5.0 and higher than 9.0 [50]. The pH of the culture medium might directly affect enzymatic function, thereby impacting levan yield, cell proliferation, and levansucrase activity [51,52]. Incubation time directly affects cell proliferation and sucrose utilization and transformation. Levan yield is inversely proportional to the sucrose residue during the fermentation period. In particular, towards the end of fermentation, sucrose concentration decreased, with only a small concentration remaining, but levan yield was maximized and stable at the end of incubation [14,29,53].

3.4. X-ray diffraction

In our previous study, levan was identified and confirmed by 1H and 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy, which explored the β-(2,6)-fructofuranose linkages and characteristics of glycosidic linkages pertaining to carbohydrate polymers [13]. However, to observe compatibility for industrial applications, levan was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

Fig. 7 shows the diffractogram result of XRD that characterized the structural properties of levan produced by B. siamensis. Only one broad peak at 17° (2θ) was obtained for the diffraction pattern, indicating an amorphous structure and no defined narrow peaks. This result confirms previous studies on levan produced by various microorganisms where amorphous characteristics were also obtained [41,54,55].

Fig. 7.

XRD diffractogram of levan produced from B. siamensis using batch bioreactor.

Amorphous biomolecules, like the levan in the present work, have great importance in medical and pharmaceutical applications due to the different physical properties (solubility and flexibility) unique to these biomacromolecules. In contrast, microbial levan structures have been shown to present some variability in their structures, with some demonstrating both narrow and broad peaks, which suggest a semi-crystalline nature [55,56] . This variability reflects the different types of levan produced by microbial sources and emphasizes the effect of production conditions on structural content.

3.5. Levan production by B. siamensis using continuous stirred tank bioreactor

In a subsequent step, based on the optimal conditions attained in batch cultures, B. siamensis levan was produced in a continuous stirred-tank bioreactor with a working volume of 780 mL. The effects of dilution rates and agitation speeds on levan synthesis were systematically investigated.

The effect of different dilution rates (0.021, 0.028, and 0.042 h⁻¹) on levan production was investigated at a constant agitation speed of 200 rpm and optimal fermentation parameters (30 % (w/v) sucrose concentration, pH 5.0, and 37 °C). The maximum levan concentration of 17.96 % (w/v) was achieved at a dilution rate of 0.021 h⁻¹ (Fig. 8a). After three days of operation, stable biomass, residual sucrose, and levan concentrations indicated that steady-state conditions had been reached. Moreover, these results showed the highest OD600 (1.4776) and the lowest amount of residual sucrose (1.92 % (w/v)) at this dilution rate indicating its high utilization of substrate [32].

Fig. 8.

Levan production by B. siamensis in the continuous stirred tank bioreactor under various dilution rates including a) 0.021 h-1, b) 0.028 h-1, and c) 0.042 h-1 at 37 °C, 200 rpm for 7 days.

Increasing the dilution rate also decreased the maximum levan yields while increasing the residual concentration of sugar, which is consistent with continuous fermentation of other microorganisms like Z. mobilis [14]. These conditions have been shown to decrease cell densities and impair substrate conversion in such systems, limiting product synthesis [56,57]. Approaches such as cell immobilization may provide answers to questions addressing cell density and productivity during continuous fermentation [58].

In turn, this optimal dilution rate of 0.021 h⁻¹ was applied to examine the effect of agitation rates (100, 200 and 300 rpm) on levan production (Fig. 9). The levan yield was highest at 200 rpm (17.96 % (w/v)). Although increasing agitation enhances mixing, aeration and heat transfer, excessive agitation at 300 rpm decreased the yields, likely due to shear forces causing levansucrase denaturation and cell autolysis [[59], [60], [61]]. On the other hand, lower agitation speeds (100 rpm) resulted in limited distribution of substrate and oxygen, which may have prevented production [61].

Fig. 9.

Levan production by B. siamensis in the continuous stirred tank bioreactor under various agitation speeds including a) 100 rpm, b) 200 rpm, and c) 300 rpm with dilution rate of 0.021 h-1 at 37 °C for 7 days.

4. Conclusions

Through this study, the researchers successfully demonstrated the production of levan, an important fructan polysaccharide, generated by using a novel strain of B. siamensis as well as the optimization of the bioprocess in batch and continuous stirred-tank bioreactors. Response surface methodology (RSM) analysis was employed to systematically investigate how each parameter influencing levan production (sucrose concentration, initial pH of the solution, and incubation period) affects levan production. The best conditions identified were 30 % (w/v) sucrose, pH of 5.0, and 48 h of incubation, resulting in 15.74 % (w/v) of levan. The results confirmed that sucrose concentration was of pivotal importance to the biosynthesis of levan, but that other factors such as pH and incubation time also had significant roles.

The X-ray diffraction profile confirmed the amorphous nature of levan as produced by B. siamensis, which demonstrates its suitability as a valuable polysaccharide for medical, pharmaceutical, and industrial applications. Such a structural feature makes it a particularly valuable candidate for biomaterial development and new therapeutic approaches, and confirms the potential of microbial levan as a versatile bioproduct.

A higher dilution rate at 0.021 h⁻¹ and 200 rpm also significantly increased levan yields, generating up to 17.96 % (w/v) concentration upon scaling up production in a continuous stirred-tank bioreactor. These optimal conditions allowed not only the production of levan but also highlighted the importance of operational parameters such as dilution rates and agitation speeds, ensuring high efficiency and low energy consumption.

A general approach is proposed for the optimization and scale-up of microbial levan, which will bridge laboratory and industrial-scale production. The results add to the existing knowledge of B. siamensis as a possible levan-producing microorganism, capable of meeting the demand in different areas such as biomaterial manufacturing and the pharmaceutical branch.

This further research may encompass bioprocessing approaches to improve yield, including substrate pairings, co-culture systems, or improved immobilization techniques. Additionally, exploring the different functional characteristics and the potential use of B. siamensis. This could open up new industrial applications and shows its potential in new fields.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Pongtorn Phengnoi: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Nuttinee Teerakulkittipong: Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Kosin Teeparuksapun: Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Gary Antonio Lirio: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Witawat Jangiam: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, and Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Burapha University, Thailand provided laboratory facilities.

This study received a research funding from the Graduate School, Burapha University, Thailand and the Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Burapha University, Thailand (Grant no. PJ.5/2563), and a Graduate Research Assistantship: GRA Phase 3 from the Faculty of Engineering, Burapha University, Thailand. This work was financially supported by (i) Burapha University (BUU), (ii) Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), and (iii) National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) (Fundamental Fund: Grant no. FF.29/2566).

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) of Burapha University (Approval no. IBC 009/2565).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Arvidson S.A., Rinehart B., Gadala-Maria F. Concentration regimes of solutions of levan polysaccharide from Bacillus sp. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006;65:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.12.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srikanth R., Reddy C.H.S.S.S., Siddartha G., Ramaiah M.J., Uppuluri K.B. Review on production, characterization and applications of microbial levan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014;120:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Öner E.T., Hernández L., Combie J. Review of Levan polysaccharide: from a century of past experiences to future prospects. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016;34:827–844. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Permatasari N.U., Ratnaningsih E., Hertadi R. The use of response surface method in optimization of levan production by heterologous expressed levansucrase from halophilic bacteria Bacillus licheniformis BK2. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018;209 doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/209/1/012015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korany S.M., El-Hendawy H.H., Sonbol H., Hamada M.A. Partial characterization of levan polymer from Pseudomonas fluorescens with significant cytotoxic and antioxidant activity. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2021;28:6679–6689. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riseh R.S., Fathi F., Vatankhah M., Kennedy J.F. Exploring the role of levan in plant immunity to pathogens: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;279 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asker M.M., Ibrahim A.Y., Mahmoud M.G., Mohamed S.S. Production and characterization of exopolysaccharide from novel Bacillus sp. M3 and evaluation on development sub chronic aluminum toxicity induced Alzheimer’s disease in male rats. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015;11:92–103. doi: 10.3844/ajbbsp.2015.92.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagh V.S., Said M.S., Bennale J.S., Dastager S.G. Isolation and structural characterization of exopolysaccharide from marine Bacillus sp. and its optimization by Microbioreactor. Carbohydr. Polym. 2002;285 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veerapandian B., Shanmugam S.R., Sivaraman S., Sriariyanun M., Karuppiah S., Venkatachalam P. Production and characterization of microbial levan using sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) juice and chicken feather peptone as a low-cost alternate medium. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veerapandian B., Shanmugam S.R., Varadhan S., Sarwareddy K.K., Mani K.P., Ponnusami V. Levan production from sucrose using chicken feather peptone as a low cost supplemental nutrient source. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;227 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira J.d.A.S., Sampaio I.C.F., Hora C.E.d.C., Matos J.B.T.L., Almeida P.F.d., Chinalia F.A. Culturing strategy for producing levan by upcycling oil produced water effluent as base medium for Zymomonas mobilis. Process Biochem. 2022;115:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2022.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasir A., Sattar F., Ashfaq I., Lindemann S.R., Chen M., Ende W.V.d., Ӧner E.T., Kirtel O., Khaliq S., Ghauri M.A., Anwar M.A. Production and characterization of a high molecular weight levan and fructooligosaccharides from a rhizospheric isolate of Bacillus aryabhattai. LWT. 2020;123 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakham N., Thaweesak S., Teerakulkittipong N., Traiosot N., Kaikaew A., Lirio G.A., Jangiam W. Structural characterization of functional ingredient levan synthesized by Bacillus siamensis isolated from traditional fermented food in Thailand. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020;2022 doi: 10.1155/2020/7352484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silbir S., Dagbagli S., Yegin S., Baysal T., Goksungur Y. Levan production by Zymomonas mobilis in batch and continuous fermentation systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;99:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilwani Y.M., Lakra A.K., Domdi L., Yadav S., Jha N., Arul V. Optimization and physicochemical characterization of low molecular levan from Enterococcus faecium MC-5 having potential biological activities. Process Biochem. 2021;110:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2021.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domżał-Kędzia M., Ostrowska M., Lewińska A., Łukaszewicz M. Recent developments and applications of microbial levan, A versatile polysaccharide-based biopolymer. Molecules. 2023;28:5407. doi: 10.3390/molecules28145407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahech I., Belghith K.S., Belghith H., Mejdoub H. Partial purification of a Bacillus licheniformis levansucrase producing levan with antitumor activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012;51:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esawy M.A., Amer H., Gamal-Eldeen A.M., Enshasy H.a.E., Helmy W.A., Abo-Zeid M.A., Malek R., Ahmed E.F., Awad G.E. Scaling up, characterization of levan and its inhibitory role in carcinogenesis initiation stage‘. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;95:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gamal A.A., Abbas H., Abdelwahed N.A., Kashef M.T., Mahmoud K., Esawy M.A., Ramadan M.A. Optimization strategy of Bacillus subtilis MT453867 levansucrase and evaluation of levan role in pancreatic cancer treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;182:1590–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wahab W.A.A., Shafey H.I., Mahrous K.F., Esawy M.A., Saleh S.A.A. Coculture of bacterial levans and evaluation of its anti-cancer activity against hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Sci. Rep. 2024;14:3173. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-52699-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramachandran M., Vaccaro A., Walle T.v.d., Georganaki M., Lugano R., Vemuri K., Kourougkiaouri D., Vazaios K., Hedlund M., Tsaridou G., Uhrbom L., Pietilä I., Martikainen M., Hooren L.v., Bontell T.O., Jakola A.S., Yu D., Westermark B., Essand M., Dimberg A. Tailoring vascular phenotype through AAV therapy promotes anti-tumor immunity in glioma. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1134–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zainulabdeen S.M.S., Khalaf K.J., Salman J.A.S. Levan, medical applications and effect on pathogens. Rev. Res. Med. Microbiol. 2023;34:207–213. doi: 10.1097/mrm.0000000000000358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahyoun A.M., Min M.W., Xu K., George S., Karboune S. Characterization of levans produced by levansucrases from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and gluconobacter oxydans: structural, techno-functional, and anti-inflammatory properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023;323 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang X., Ye X., Hu Y., Tang Z., Zhang T., Zhou H., Zhou T., Bai X., Pi E., Xie B., Shi L. Exopolysaccharides of paenibacillus polymyxa: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;261 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freitas F., Torres C.A.V., Reis M.A.M. Engineering aspects of microbial exopolysaccharide production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017;245:1674–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bashkeran T., Sakai S., Nurhayati R.W., Nguyen M.H., Mubarok W., Goto R., Lubis D.S.H., Luthfi A., Nadzir M.M. Microbial Exopolysaccharides. 1st ed. CRC Press; Florida: 2024. Biomedical applications of exopolysaccharides; pp. 250–274. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadhana S.L., Dharshini K.P., Devi D.R., Naryanana V.H.B., Veerapandian B., Luo R., Yang J., Shanmugam S.R., Ponnusami V., Brzezinski M., Zheng Y. Investigation of Levan-derived nanoparticles of Dolutegravir: a promising approach for the delivery of anti-HIV drug as milk admixture. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024;113:2513–2523. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2024.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tekin A., Tornacı S., Boyacı D., Li S., Calligaris S., Maalej H., Öner E.T. Hydrogels of levan polysaccharide: a systematic review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025;315 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.144430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vieira A.M., Zahed F., Crispim A.C., Bento E.d.S., França R.d.F.O., Pinheiro I.O., Pardo L.A., Carvalho B.M. Production of levan from Bacillus subtilis var. Natto and apoptotic effect on SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;273 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altıntaş Ö.E., Öner E.T., Çabuk A., Çelik P.A. Biosynthesis of Levan by Halomonas elongata 153B: optimization for enhanced production and potential biological activities for pharmaceutical field. J. Polym. Environ. 2023;31:1440–1455. doi: 10.1007/s10924-022-02681-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phengnoi P., Sattavanich S., Charoensup C., Nuengnoon S., Janthorn K., Teerakulkittipong N., Jangiam W. Production and characterization of levan by Bacillus siamensis at flask and bioreactor. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food. 2023;16:15–23. doi: 10.37221/eaef.16.1_15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phengnoi P., Thakham N., Rachphirom T., Teerakulkittipong N., Lirio G.A., Jangiam W. Characterization of levansucrase produced by novel Bacillus siamensis and optimization of culture condition for levan biosynthesis. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sumpavapol P., Tongyonk L., Tanasupawat S., Chokesajjawatee N., Luxananil P., Visessanguan W. Bacillus siamensis sp. nov., isolated from salted crab (poo-khem) in Thailand. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009;60:2364–2370. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.018879-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L., Wu D., Xu H., Zhao Z., Chen Q., Li H., Wei Z., Chen L. Characterization, production optimization, and fructanogenic traits of levan in a new microbacterium isolate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;250 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen R.A., Bakken L.R. Viability of soil bacteria: optimization of plate-counting technique and comparison between total counts and plate counts within different size groups. Microb. Ecol. 1987;13:59–74. doi: 10.1007/bf02014963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sha Y., Zeng Q., Sui S. Screening and application of Bacillus strains isolated from nonrhizospheric rice soil for the biocontrol of rice blast. Plant Pathol. J. 2020;36:231–243. doi: 10.5423/ppj.oa.02.2020.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manmai N., Balakrishnan D., Obey G., Ito N., Ramaraj R., Unpaprom Y., Velu G G. Alkali pretreatment method of dairy wastewater based grown Arthrospira platensis for enzymatic degradation and bioethanol production. Fuel. 2022;330 doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Shazly M., Tai C., Wu T., Csupor D., Hohmann J., Chang F., Wu Y. Use, history, and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry chemical analysis of Aconitum. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015;24:29–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han J., Feng H., Wang X., Liu Z., Wu Z. Levan from Leuconostoc citreum BD1707: production optimization and changes in molecular weight distribution during cultivation. BMC Biotechnol. 2021;21:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12896-021-00673-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatiboruah D., Devi D.Y., Namsa N.D., Nath P. Turbidimetric analysis of growth kinetics of bacteria in the laboratory environment using smartphone. J. Biophotonics. 2020;13 doi: 10.1002/jbio.201960159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mantovan J., Bersaneti G.T., Faria-Tischer P.C., Celligoi M.a.P.C., Mali S. Use of microbial levan in edible films based on cassava starch. Food Packag. Shelf Life. 2018;18:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fpsl.2018.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abou-Taleb K., Abdel-Monem M., Yassin M., Draz A. Production, purification and characterization of Levan polymer from Bacillus lentus V8 strain. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2014;5:22–32. doi: 10.9734/bmrj/2015/12448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdel-Fattah A.M., Gamal-Eldeen A.M., Helmy W.A., Esawy M.A. Antitumor and antioxidant activities of levan and its derivative from the isolate Bacillus subtilis NRC1aza. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;89:314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Homann A., Biedendieck R., Götze S., Jahn D., Seibel J. Insights into polymer versus oligosaccharide synthesis: mutagenesis and mechanistic studies of a novel levansucrase from Bacillus megaterium. Biochem. J. 2007;407:189–198. doi: 10.1042/bj20070600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belghith K.S., Dahech I., Belghith H., Mejdoub H. Microbial production of levansucrase for synthesis of fructooligosaccharides and levan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012;50:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chirife J., Herszage L., Joseph A., Kohn E.S. In vitro study of bacterial growth inhibition in concentrated sugar solutions: microbiological basis for the use of sugar in treating infected wounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1983;23:766–773. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.5.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassan S.W.M., Ibrahim H.A.H. Production, characterization and valuable applications of exopolysaccharides from marine Bacillus subtilis SH1. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2017;66:449–462. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.7001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bekers M., Upite D., Kaminska E., Laukevics J., Grube M., Vigants A., Linde R. Stability of levan produced by Zymomonas mobilis. Process Biochem. 2024;40:1535–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2004.01.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wannasutta R., Laopeng S., Yuensuk S., McCloskey S., Riddech N., Mongkolthanaruk W. Biopolymer-levan characterization in Bacillus species isolated from traditionally fermented soybeans (Thua Nao) ACS Omega. 2025;10:1677–1687. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.4c09641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prakash P.O., Rayasam K., Peddireddy V., Chaitanya K.V. Improved levan production by novel calidifontibacillus erzurumensis LEV207 using one variable at a time approach. Int. J. Microbiol. 2025;28:1033–1045. doi: 10.1007/s10123-024-00597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.González-Torres M., Hernández-Rosas F., Pacheco N., Salinas-Ruiz J., Herrera-Corredor J.A., Hernández-Martínez R. Levan production by Suhomyces kilbournensis using sugarcane molasses as a carbon source in submerged fermentation. Molecules. 2024;29:1105. doi: 10.3390/molecules29051105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu M., Zhang L., Zhao F., Wang J., Zhao B., Zhou Z., Han Y. Cloning and expression of levansucrase gene of Bacillus velezensis BM-2 and enzymatic synthesis of Levan. Processes. 2021;9:317. doi: 10.3390/pr9020317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gojgic-Cvijovic G.D., Jakovljevic D.M., Loncarevic B.D., Todorovic N.M., Pergal M.V., Ciric J., Loos K., Beskoski V.P., Vrvic M.M. Production of levan by Bacillus licheniformis NS032 in sugar beet molasses-based medium. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;121:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ragab T.I., Shalaby A.S.G., Awdan S.a.E., El-Bassyouni G.T., Salama B.M., Helmy W.A., Esawy M.A. Role of levan extracted from bacterial honey isolates in curing peptic ulcer: in vivo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;142:564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mendonça C.M., Oliveira R.C., Freire R.K., Piazentin A.C., Pereira W.A., Gudiña E.J., Evtuguin D.V., Converti A., Santos J.H., Nunes C., Rodrigues L.R., Oliveira R.P. Characterization of levan produced by a paenibacillus sp. isolated from Brazilian crude oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;186:788–799. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu W., Liu Q., Bai Y., Yu S., Zhang T., Jiang B., Mu W. Physicochemical properties of a high molecular weight levan from brenneria sp. EniD 312. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;109:810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y., Xiong H., Chen Z., Fu Y., Xu Q., Chen N. Effect of fed-batch and chemostat cultivation processes of C. glutamicum CP for l-leucine production. Bioengineered. 2021;12:426–439. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1874693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Desjardins P., Meghrous J., Lacroix C. Effect of aeration and dilution rate on nisin Z production during continuous fermentation with free and immobilized lactococcus lactis UL719 in supplemented whey permeate. Int. Dairy J. 2001;11:943–951. doi: 10.1016/s0958-6946(01)00128-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mummaleti G., Sarma C., Kalakandan S., Sivanandham V., Rawson A., Anandharaj A. Optimization and extraction of edible microbial polysaccharide from fresh coconut inflorescence sap: an alternative substrate. LWT. 2020;138 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radchenkova N., Vassilev S., Martinov M., Kuncheva M., Panchev I., Vlaev S., Kambourova M. Optimization of the aeration and agitation speed of Aeribacillus palidus 418 exopolysaccharide production and the emulsifying properties of the product. Process Biochem. 2014;49:576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2014.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh R., Singh T., Kennedy J.F. Enzymatic synthesis of fructooligosaccharides from inulin in a batch system. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.carpta.2020.100009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.