Abstract

Photothermal therapy (PTT) combined with chemotherapy is a promising strategy for tumor treatment. However, its efficacy is often limited by the uncertainty of the irradiation timing of the photothermal agent. Herein, we rationally designed a self-assembling peptide-drug conjugate, IR775-Phe-Phe-Lys(CPT)-Lys(Biotin)-OH (IR-FFKK-CPT), which spontaneously self-assembles into fluorescence (FL)-quenched nanoparticles with high photothermal conversion efficiency. After being uptaken by the cancer cells, the nanoparticles are hydrolysed by carboxylesterase and disassembled to release CPT, turning the FL “On”. The “On” FL displays not only the initiation of chemotherapy but also the decline of PTT efficacy. By leveraging the “On” FL as a temporal indicator, we precisely backtrack the optimal cell/tumor irradiation timing to be 4 h/12 h post-incubation/injection in cells/tumors. Subsequent therapeutic studies demonstrated that the timed irradiation on tumor at 12 h post injection significantly maximized tumor treatment outcomes, with average relative tumor volume on day 14 reduced to 13.7 % or 10.2 % of that in the groups of 6 h or 24 h, respectively. Guided by this timed PTT, IR-FFKK-CPT achieved an excellent tumor growth inhibition rate of 96.2 %, significantly outperforming the four positive control groups which showed tumor inhibition rates of 26.3 %–34.1 %. Our self-regulating theranostic strategy, that synchronizes timed PTT with visualized chemotherapy to maximize tumor treatment, provides people with a promising approach for precise tumor therapy.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Disassembly, Irradiation timing, Nanoparticle, Photothermal therapy

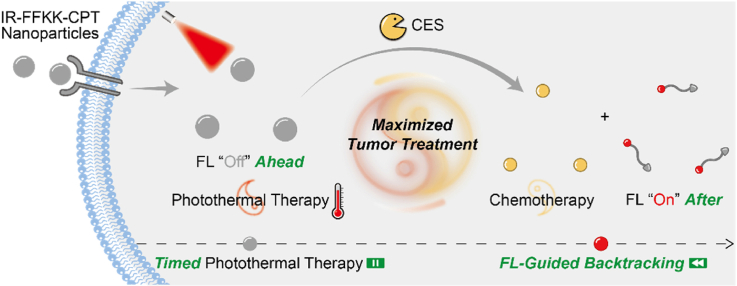

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A timed photothermal therapy combining fluorescence-on chemotherapy strategy.

-

•

It utilizes fluorescence activation as a temporal reference.

-

•

It realizes the backtracking of irradiation timing of photothermal therapy.

-

•

It realizes combinational therapy of chemotherapy with photothermal therapy.

-

•

It realizes maximized cancer cell apoptosis and tumor treatment.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, cancer persists as a leading cause of global mortality [1]. Conventional cancer therapeutic modalities (i.e., surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy) remain clinical mainstays [2]. However, each modality has intrinsic limitations, such as incomplete tumor resection [3], dose-limiting toxicity [4], and systemic side effects or multidrug resistance [5]. To address these issues, combinational therapies that integrate multiple treatment modalities have been widely explored to improve cancer treatment efficacy [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. For instance, postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been clinically applied to enhance tumor control and patient survival [10,11]. Nevertheless, such combination faces poor temporal coordination between treatment windows, potentially leading to tumor recurrence, metastasis, or drug resistance [[12], [13], [14]]. Therefore, there is still an urgent need to develop more synergistic combinational therapies. Photothermal therapy (PTT), which utilizes near-infrared (NIR) light to activate photothermal agents (PTAs) and generate localized hyperthermia for tumor ablation, has gained considerable attention due to its spatiotemporal controllability, non-invasiveness, and reduced systemic toxicity [[15], [16], [17], [18]]. The rising temperature generated by PTT can enhance cellular uptake of chemotherapeutic drugs and increase drug cytotoxicity [[19], [20], [21]]. Moreover, chemotherapy provides a systemic therapeutic effect to simultaneously treat both primary and distant tumors, compensating for the limited capability of PTT in treating metastatic tumors [[22], [23], [24]]. Therefore, leveraging the synergistic effects of hyperthermia-enhanced drug permeability and chemotherapy-sensitized thermal vulnerability, the combinational therapy of PTT with chemotherapy has emerged as a promising approach for more efficient tumor treatment.

To maximize the therapeutic efficacy of PTT combined with chemotherapy, both modalities should be precisely synchronized spatiotemporally. However, in conventional approach, chemotherapeutic drugs and PTAs are typically co-encapsulated into lipid-based nanocarriers or inorganic polymeric systems [25,26]. These non-covalent nano-encapsulation strategies often suffer from premature drug leakage during circulation and instability within the tumor microenvironment, consequently compromising the synergistic efficacy of the combined therapy [27,28]. To overcome these drawbacks, a more reliable strategy is to covalently conjugate the chemotherapeutic drug and the PTA into a single molecule [[29], [30], [31]]. Such covalent integration ensures co-localization and co-activation at the tumor site spatially, as the PTA and chemotherapeutic drug share the same circulation process and intracellular distribution, eliminating the uncertainty associated with non-covalent delivery platforms [32,33]. Moreover, if the covalent conjugate is engineered to self-assemble into nanostructures, its photothermal efficiency is promoted through the enhanced non-irradiative internal conversion of its PTA [[34], [35], [36]]. Moreover, through their enhanced permeability and retention effect, the nanostructures also increase the accumulation of the drug-PTA conjugate in tumors [37,38]. Therefore, the rational design of a self-assembling, covalent drug-PTA conjugate is an ideal strategy to achieve synchronized, highly efficient PTT and chemotherapy.

While the abovementioned strategy improves spatial precision of combinational therapy, accurately coordinating the activation timing of PTT and chemotherapy remains a challenge, especially for the irradiation timing of PTT [39,40]. Conventional irradiation schedules rely on empirical protocols, typically 2–6 h post-intratumoral injection or 12–24 h post-intravenous administration [41]. Such approaches ignore dynamic variations in drug pharmacokinetics and tumor heterogeneity, leading to suboptimal treatment outcomes. To improve the temporal precision, FL imaging is employed to guide the combinational therapy by leveraging the inherent optical properties of PTAs [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. However, a fundamental contradiction exists between PTT and FL imaging at the molecular level. Both processes originate from the same excited electronic state but diverge into two competing de-excitation pathways: non-radiative decay (heat generation for PTT) and radiative decay (FL emission) [47,48]. Therefore, enhancing FL emission (turn “on” for imaging) inevitably reduces the photothermal conversion efficiency (turn “off” for therapy), or vice versa [49]. This intrinsic photophysical inverse relationship brings about a great challenge in FL-guided PTT combined with chemotherapy, where high FL signal may misleadingly indicate low PTT performance. Thus, determining the optimal irradiation timing in PTT combined with chemotherapy is crucial for maximizing synergistic therapeutic efficacy. However, to the best of our knowledge, no prior study has systematically investigated the optimal irradiation timing of PTT in the combinational therapy.

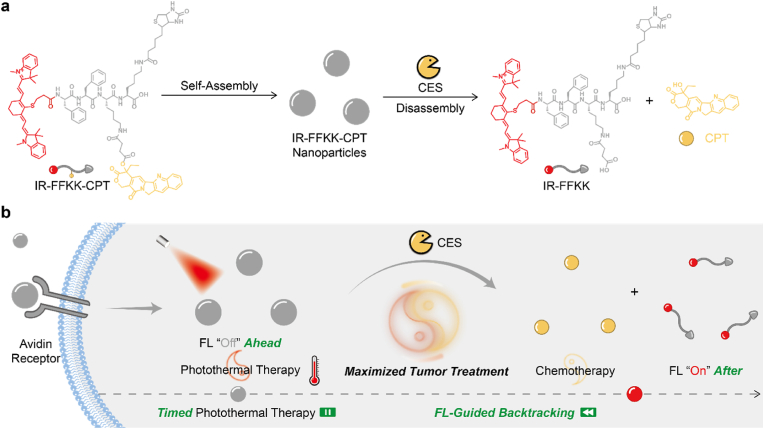

To address this challenge, we herein propose a timed PTT combining FL-on chemotherapy strategy. This strategy utilizes FL activation as a temporal reference to simultaneously visualize the initialization of chemotherapy and backtrack the optimal PTT irradiation timing to maximize tumor treatment. We rationally designed a multifunctional peptide-drug conjugate IR775-Phe-Phe-Lys(CPT)-Lys(Biotin)-OH (IR-FFKK-CPT, Scheme 1a), which integrates four parts: i) a self-assembling peptide backbone Phe-Phe-Lys-Lys (FFKK), where its hydrophobic Phe-Phe (FF) motif facilitates self-assembling of the conjugate via π–π interactions [50,51]; ii) IR775, a potent PTA for efficient light-to-heat conversion; iii) camptothecin (CPT), a chemotherapeutic drug conjugated to Lys via an intracellular carboxylesterase (CES)-cleavable ester bond; and iv) biotin, a tumor-targeting moiety. As shown in Scheme 1a, IR-FFKK-CPT spontaneously self-assembles into nanoparticles. Upon CES-mediated cleavage, IR-FFKK-CPT is hydrolysed into IR775-Phe-Phe-Lys(SA)-Lys(Biotin)-OH (IR-FFKK), accompanied by the disassembly of nanoparticles and CPT release. The intracellular mechanism is depicted in Scheme 1b. Specifically, IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles with suppressed FL and high PTT efficacy are efficiently internalized into cancer cells via biotin-avidin specific interactions. Then, intracellular CES hydrolyses the ester bond, triggering CPT release and nanoparticle disassembly-induced FL activation. The FL activation marks a decline in PTT efficiency and the initialization of chemotherapy. By leveraging FL dynamics as temporal reference, this strategy enables precise backtracking of the optimal irradiation timing, ensuring that laser irradiation occurs before substantial nanoparticle disassembly, not only eliminating the uncertainties of irradiation timing but also synchronizing timed PTT with chemotherapy spatiotemporally to maximize tumor treatment.

Scheme 1.

(a) Molecular design of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles, their CES-triggered disassembly to yield hydrophilic product IR-FFKK and CPT. (b) Schematic illustration of the mechanism of FL-guided backtracking of the optimal irradiation timing for combinational PTT with chemotherapy to maximize tumor treatment.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Preparation and characterizations of IR-FFKK-CPT

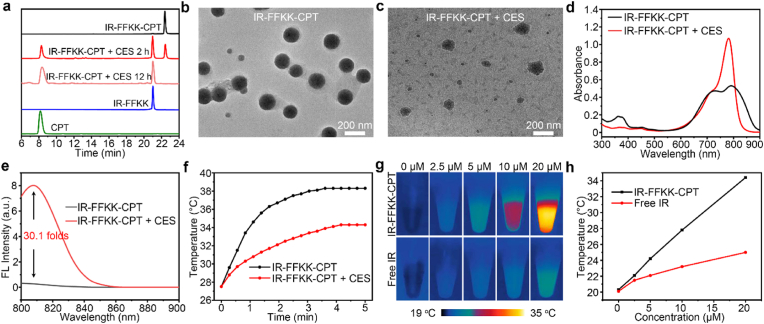

IR-FFKK-CPT and the control compounds, including FFKK (peptide backbone), IR-FFKK (the CES-hydrolysis product of IR-FFKK-CPT), and Phe-Phe-Lys(CPT)-Lys(Biotin) (FFKK-CPT, which lacks the PTA IR775) were synthesized and characterized (Schemes S1–S7, Fig. S1–S19, Table S1). To validate the Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR and 13C NMR) were utilized to verify the successful syntheses of the above compounds. The critical aggregation concentrations (CAC) values of IR-FFKK-CPT and IR-FFKK in PBS (pH 7.4) were measured to be 1.0 μM and 12.0 μM, respectively (Fig. S20). Based on the CAC values, subsequent experiments were conducted at compound concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μM. Then, we verified CES-responsive hydrolysis of IR-FFKK-CPT using HPLC. Specifically, 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) was incubated with 20 U mL−1 CES at 37 °C for 2 h or 12 h. HPLC analysis and ESI-MS showed that, most of IR-FFKK-CPT were hydrolysed to IR-FFKK, accompanied by CPT release after 2 h of incubation, and complete hydrolysis was observed by 12 h (Fig. 1a, S21, and S22, Table S2). We further verified the disassembly of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles after CES-responsive hydrolysis via transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation. As shown in Fig. 1b and Fig. S23, at a concentration of 10 μM, IR-FFKK-CPT self-assembles into nanoparticles with an average diameter of 180.9 ± 5.1 nm. Additionally, dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement results showed a hydrodynamic diameter of 208.5 nm, which aligned well with that of TEM-derived (Fig. S24). After incubation with CES for 2 h, the nanoparticles obviously disassembled, probably due to the leave of hydrophobic CPT and the yield of the more hydrophilic compound IR-FFKK (Fig. 1c). At a concentration exceeding its CAC value of 12.0 μM (e.g., 20 μM), IR-FFKK also self-assembles into nanoparticles with an average diameter of 182.6 ± 6.7 nm (Fig. S25). Next, we measured zeta potential of 10 μM free IR775 and IR-FFKK-CPT in PBS (pH 7.4). Results showed zeta potential values of +23.9 mV for free IR775 and + 14.8 mV for IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles (Fig. S26), respectively, confirming the positively charged surface of both compounds. Then, the photophysics of IR-FFKK-CPT were investigated before and after CES-mediated hydrolysis. We first examined the ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectra of IR-FFKK-CPT in PBS (pH 7.4) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). As shown in Fig. S27, at compound concentrations 1–10 μM, in DMSO, the absorption spectra of IR-FFKK-CPT showed a sharp absorption peak at 775 nm while in PBS the peak broadened into two peaks at 730 nm and 815 nm, validating it self-assembled into nanoparticles in aqueous solution. We then investigated the UV–vis spectrum of 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles after CES-mediated hydrolysis. The results showed that, after 2 h of incubation with 20 U mL−1 CES at 37 °C, the broad absorption peaks of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles at 650–850 nm transitioned into the sharp peak at 775 nm (Fig. 1d), confirming the enzymatic cleavage-induced disassembly of nanoparticles and the yield of the water-soluble product IR-FFKK. This was further corroborated by the FL spectra of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles with (or w/o) CES-mediated hydrolysis. As shown in Fig. 1e, after 2 h of incubation with 20 U mL−1 CES at 37 °C, the IR-FFKK-CPT + CES group exhibited a 30.1-fold higher FL intensity at 808 nm than that of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. In addition, we investigated the selectivity of IR-FFKK-CPT toward CES. As shown in Fig. S28, IR-FFKK-CPT showed a significant FL “Turn On” after incubation with 20 U mL−1 CES at 37 °C for 12 h. In contrast, IR-FFKK-CPT remained “Off” after incubation with other representative biological species including enzymes (i.e., alkaline phosphatase (ALP), caspase-3 (Casp-3)), metal ions (i.e., Fe3+, K+, Na+), and bioactive species (i.e., GSH, Cys). These results confirmed the high specificity of IR-FFKK-CPT for CES. Next, we investigated the reaction kinetics of IR-FFKK-CPT toward CES. First, the linear relationship between the peak area and concentration of CPT was obtained (Fig. S29a). Then, the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of CES on IR-FFKK-CPT was calculated to be 203.5 M−1s−1 (Fig. S29b). Collectively, these results demonstrated that IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles can be hydrolysed by CES, leading to the yield of hydrophilic product IR-FFKK and subsequent disassembly-induced FL activation. In addition, to investigate whether aggregation significantly influenced the optical properties of IR-FFKK, we measured the UV–vis and FL spectra of IR-FFKK at concentrations below or above its CAC (12.0 μM)–specifically at 10, 20, 30, 40, or 50 μM. As shown in Fig. S30a, 10 μM IR-FFKK (which was lower than its CAC) showed a sharp absorption peak at 775 nm. Upon exceeding CAC, its sharp peak broadened into two peaks at 700 nm and 775 nm. Besides, the FL intensity of IR-FFKK showed a concentration-dependent decrease when its concentration exceeds the CAC (Fig. S30b). These findings demonstrated that, upon exceeding its CAC, IR-FFKK undergoes self-assembly into nanoparticles, leading to significant changes in its optical properties (absorption peak broadening and FL quenching). We then investigated whether the CES-mediated hydrolysis influenced the photothermal properties of the IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. At concentration of 10 μM, IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles (with or w/o CES) and IR-FFKK were irradiated with an 808 nm laser (1 W cm−2) for 5 min and their temperature changes were monitored with a thermal imaging camera. As shown in Fig. 1f and S31a, temperatures of the three samples showed time-dependent increases and reached their plateau within 4 min. Notably, after 5 min of irradiation, the IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticle group showed a temperature increase of 10.8 °C which is 1.6- or 2.8-fold of that of the IR-FFKK-CPT + CES group (6.8 °C) or the IR-FFKK group (3.8 °C), respectively. These results indicated that the CES-triggered disassembly of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticle obviously reduced its photothermal performance. Next, we examined the temperature changes of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles, free IR775, and IR-FFKK at different compound concentrations under 808 nm laser irradiation (1 W cm−2, 5 min). As shown in Fig. 1g and h, S31b, and S31c, all three samples exhibited a concentration-dependent photothermal response. At compound concentration of 20 μM, IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles (temperature increase: 14.1 °C) showed a 2.9- or 2.5-fold higher temperature increment than free IR775 (temperature increase: 4.9 °C) or IR-FFKK (temperature increase: 5.6 °C), respectively. These results demonstrated that the self-assembly of IR-FFKK-CPT into nanoparticles markedly enhanced the photothermal conversion efficiency of photothermal moiety IR775. Additionally, we evaluated the photostability of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles by performing two cycles of NIR laser on/off experiments (808 nm, 1 W cm−2). Results showed that, compared with free IR775, IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles exhibited better photostability (Fig. S32). We then investigated the stability of IR-FFKK-CPT under physiological conditions. As shown in Fig. S33, 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT remained stable after incubation with PBS (pH 7.4) or 10 % fetal bovine serum at 37 °C for 14 days, demonstrating the good stability of IR-FFKK-CPT under physiological conditions.

Fig. 1.

(a) HPLC traces of 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT after incubation with 20 U mL−1 CES at 37 °C for 2 h or 12 h in PBS (pH 7.4). Wavelength for detection: 254 nm. (b) TEM images of 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT and (c) 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT after incubation with 20 U mL−1 CES at 37 °C for 2 h in PBS (pH 7.4). (d) Absorption and (e) FL spectra of 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT before and after incubation 20 U mL−1 CES at 37 °C for 2 h in PBS (pH 7.4). (f) Temperature-rising curves of 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT with (or w/o) CES upon laser irradiation at 808 nm (5 min, 1 W cm−2). (g) Thermal images of IR-FFKK-CPT and free IR775 at different compound concentrations after laser irradiation at 808 nm (5 min, 1 W cm−2). (h) Quantitative temperature analyses of thermal images in g.

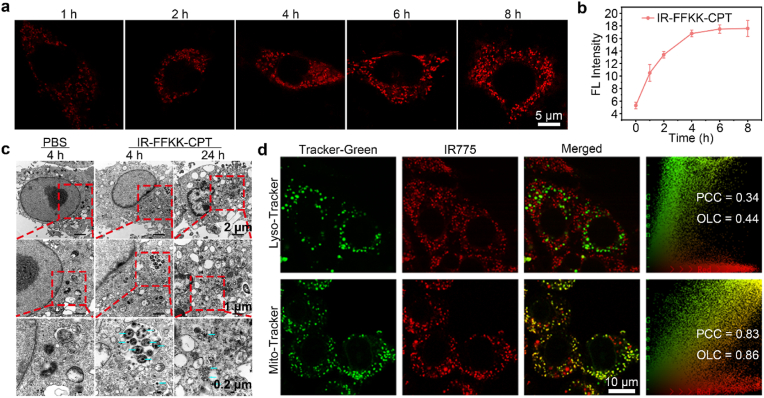

2.2. Cellular uptake and localization of IR-FFKK-CPT

Next, we evaluated the FL activation of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles at cellular level. Given the crucial role of CES in nanoparticle disassembly, we selected 4T1 cells, which overexpress CES, as the cellular model for subsequent experiments [52]. Confocal fluorescence imaging was first performed to monitor the intracellular FL activation of the nanoparticles over time (Fig. 2a). Results showed that the red FL gradually increased over time and plateaued at approximately 6 h. Quantitative FL analysis in Fig. 2b further confirmed this trend, showing that the FL intensity in cells at 6 h post-incubation was 3.3-fold higher than that at 0 h post-incubation. Based on these findings, we speculated that the optimal PTT irradiation timing on cells should be ahead of 6 h. To verify this, we examined the temperature increase of 4T1 cells incubated with 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles for 2 h, 4 h, or 6 h, followed by 808 nm laser irradiation (1 W cm−2, 5 min). As shown in Fig. S34a, after 5 min of laser irradiation, each group showed a cell temperature increment. Notably, the cell temperature in the 4 h group increased by approximately 10.5 °C, significantly higher than that observed in the 2 h group (7.9 °C) or 6 h group (6.9 °C), respectively (Fig. S34b). We further performed a CCK-8 assay to validate that 4 h was the optimal incubation time to ensure a maximum PTT efficacy for cell killing. To achieve this, 4T1 cells were incubated with PBS for 6 h (negative control) or 5 μM IR-FFKK-CPT for 2 h, 4 h, or 6 h. Then, the cells were irradiated with 808 nm laser (5 min, 1 W cm−2), cultured for an additional 24 h and subsequently subjected to CCK-8 assay. As shown in Fig. S35, 4 h incubation group showed the highest cytotoxicity on 4T1 cells (cell viability: 32.5 %), which was significantly higher than that of 2 h (cell viability: 52.4 %) or 6 h (cell viability: 45.3 %) incubation group. These results suggested that, after 4 h incubation with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles, the 4T1 cells not only generated the most efficient photothermal response but also showed the lowest cell viability upon 808 nm laser irradiation (1 W cm−2, 5 min) among the tested time points, confirming that 4 h was the optimal incubation time to ensure a maximum PTT efficacy for cell killing. To investigate the intracellular distribution of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles, 4T1 cells were treated with the nanoparticles (PBS as control) for 4 h or 24 h and subsequently analyzed with bio-transmission electron microscopy (bio-TEM). As shown in Fig. 2c, no exogenous nanoparticle was present in the cells of the PBS control group for 4 h. In contrast, obviously nanoparticles were found in the mitochondria of the cells treated with 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles for 4 h. Interestingly, after 24 h incubation, the nanoparticles were found dispersed in the cytoplasm with a significantly reduced size. These findings suggested that IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles were internalized by 4T1 cells and accumulated in mitochondria after 4 h of incubation, followed by CES-mediated disassembly. Given that the intrinsic positive charge of the IR775 moiety in IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles can facilitate electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged mitochondria, we speculated that the IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles are willing to accumulate in mitochondria. To verify this, we performed co-localization experiments on the 4T1 cells using LysoTracker Green (lysosomal marker) and MitoTracker (mitochondrial marker) as indicators. As shown in Fig. 2d, the IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles exhibited strong co-localization with mitochondria in the cells at 4 h post-incubation (average Pearson's correlation coefficient (PCC) value of 0.83 and average overlap coefficient (OLC) value of 0.86) rather than lysosome (average PCC value of 0.34 and average OLC value of 0.44) [53]. These results confirmed the efficient mitochondrial targeting ability of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. Next, we investigated the lysosomal escape process of IR-FFKK-CPT. Specifically, we performed dual-channel FL imaging using the intrinsic FL of CPT (blue channel) and IR775 (NIR channel) to observe the intracellular process of 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles at 1 h and 4 h post-incubation with 4T1 cells. As shown in Fig. S36a, at 1 h post-incubation, IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles were mainly located in lysosomes with PCC/OLC values of 0.75/0.78 (CPT) and 0.85/0.86 (IR775), respectively. In contrast, co-localization of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles with mitochondria was limited (PCC/OLC: 0.33/0.40 for CPT, 0.56/0.63 for IR775), indicating the predominant lysosomal localization of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles at early endocytosis stages. These results also suggested that CES-mediated cleavage was initiated within the lysosomes, where both CPT and IR moieties were “Turned on”. As displayed in Fig. S36b, by 4 h, FL signals of CPT and IR775 showed reduced co-localization with LysoTracker (PCC/OLC: 0.39/0.45 for CPT, 0.36/0.42 for IR775). This indicated the escape of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles from lysosomes, probably due to the positively charged nature of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles which disrupted the acidic lysosomal membrane through electrostatic interactions and consequently promoted lysosome permeabilization. The IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles exhibited strong co-localization with mitochondria with PCC/OLC values of 0.90/0.91 (IR775). Interestingly, CPT showed limited co-localization with mitochondria with PCC/OLC values of 0.48/0.54 at 4 h post-incubation, which was probably attributed to the fact that CPT is a hydrophilic, small-molecule chemotherapeutic agent without intrinsic mitochondrial-targeting capability. Upon CES-mediated cleavage, CPT was released as a free molecule and likely diffused throughout the cytoplasm, leading to a low mitochondria co-localization value. Collectively, these results demonstrated a lysosomal escape followed by mitochondrial accumulation of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles.

Fig. 2.

(a) Confocal fluorescence images of 4T1 cells after incubation with 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles at different time points. (b) Quantitative analyses of the FL intensities at different time points in a by flow cytometry (mean ± SD, n = 3). (c) Bio-TEM images of 4T1 cells after treatments with PBS at 4 h or 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles at 4 h or 24 h. (d) Co-localization detection in 4T1 cells after incubation with 10 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles for 4 h. The 4T1 cells were co-stained with Lyso-Tracker or Mito-Tracker.

2.3. Evaluation of cell cytotoxicity of IR-FFKK-CPT

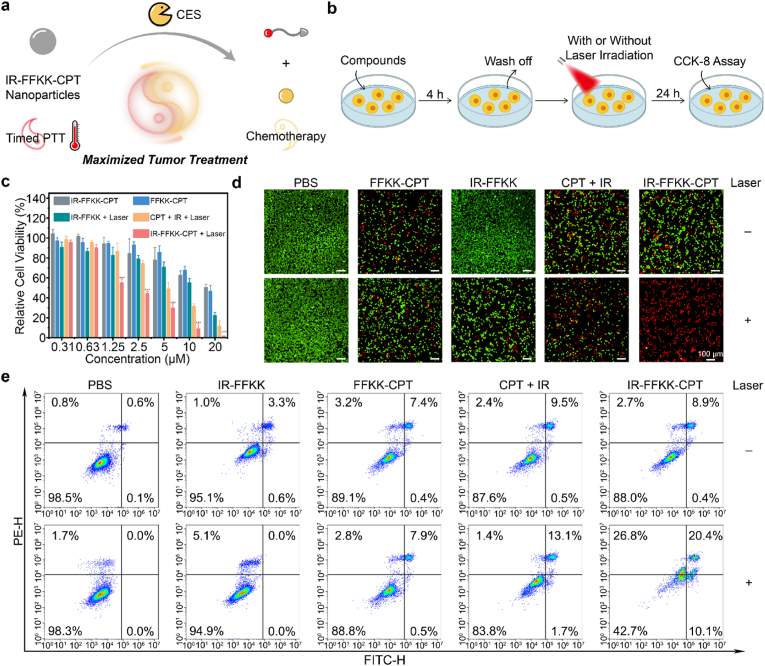

Since the optimal irradiation timing of 4 h was selected, we then testified whether IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles could maximize cancer cell treatment through the combinational therapy strategy (Fig. 3a). As illustrated in Fig. 3b, 4T1 cells were incubated with different compounds for 4 h, followed by washing to remove the residual drugs. Then, the 4T1 cells were irradiated with 808 nm laser (5 min, 1 W cm−2) or kept in the dark. Afterward, the cells were cultured for an additional 24 h and subsequently subjected to cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. First, we examined the cytotoxicity of FFKK, Free CPT, and FFKK-CPT on the 4T1 cells to investigate the impact of the self-assembling peptide scaffold FFKK on chemotherapeutic agent CPT. As shown in Fig. S37, the FFKK exhibited negligible cytotoxicity on the cells (cell viability above 80 % at a concentration up to 20 μM). In contrast, both FFKK-CPT and free CPT displayed dose-dependent cytotoxicity. At compound concentration of 20 μM, viability of 4T1 cells reduced to 46.3 % or 49.3 % in FFKK-CPT group or Free CPT group, respectively (Fig. S37). Notably, at same concentration, there was no significant difference between the cytotoxicity of FFKK-CPT and free CPT on the cells, suggesting that the peptide scaffold did not affect the therapeutic efficacy of CPT. Next, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of the PTAs free IR775, IR-FFKK, and their laser-treated counterparts at various concentrations. As shown in Fig. S38, in the absence of laser irradiation, both free IR775 and IR-FFKK showed negligible cytotoxicity on 4T1 cells, with 4T1 cell viability exceeding 80 % at compound concentration of 20 μM. However, upon 808 nm laser irradiation, both free IR775 and IR-FFKK exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity due to their photothermal effects. Interestingly, at concentration of 20 μM which exceeds its CAC value 12.0 μM (i.e., assembled into nanoparticles), IR-FFKK showed significantly enhanced photocytotoxicity on the cells (cell viability: 22.1 %) than free IR775 (cell viability: 38.3 %) upon laser irradiation. The above results collectively demonstrated that, although the peptide scaffold did not impose cytotoxicity on the cells, its property of self-assembling significantly improved the PTT efficacy of IR775.

Fig. 3.

(a) Illustration of maximized tumor treatment of combinational therapy with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. (b) Cartoon flowchart of CCK-8 assay. (c) Cell viabilities of 4T1 cells after different treatments as indicated (mean ± SD, n = 6, ∗∗∗P < 0.001). (d) Live/dead staining of 4T1 cells after different treatments. (e) Flow cytometry analyses of apoptosis/necrosis in 4T1 cells in each group.

Then, we evaluated the combinational therapeutic effect of IR-FFKK-CPT on 4T1 cells. In detail, one experimental group (i.e., IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser) and four positive control groups (i.e., IR-FFKK-CPT for dark cytotoxicity control, FFKK-CPT for chemotherapy-only control, IR-FFKK + Laser for PTT-only control, and CPT + IR + Laser for free drug combination control) were designed. PBS was designated as the negative control group. As depicted in Fig. 3c, all five groups showed dose-dependent cytotoxicity. At the same compound concentration and in the absence of laser irradiation, FFKK-CPT showed similar cytotoxicity with IR-FFKK-CPT, suggesting that PTA modification did not affect the cytotoxicity of CPT on 4T1 cells. At compound concentration of 20 μM, the combinational therapy of IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser showed the highest cytotoxicity on 4T1 cells (cell viability: 1.3 %). In contrast, the two groups of single therapy had much weaker cell killing effects (cell viability 46.3 % of FFKK-CPT for chemotherapy and cell viability 22.1 % of the IR-FFKK + Laser for PTT. Additionally, cell killing ability of the combinational therapy of CPT + IR + Laser group (cell viability 11.3 %) was also much weaker than that of the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser, suggesting self-assembly of IR-FFKK-CPT into nanoparticles greatly enhanced the PTT effect of IR775. Furthermore, we directly visualized the cell killing efficiency of the above groups using live/dead staining. 4T1 cells after the above treatments were incubated with calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Calcein-AM, indicating live cells with green FL) and propidium iodide (PI, indicating dead cells with red FL) at a compound concentration of 10 μM. As shown in Fig. 3d, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group exhibited the highest proportion of red FL compared to other control groups, indicating the highest cell death in the experimental group. These results were consistent with those of the CCK-8 viability assays (Fig. 3c), further validating the strongest combinational therapeutic efficacy of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles on 4T1 cells among the five groups. Furthermore, annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate/PI dual staining was performed, followed by flow cytometry analysis to quantify 4T1 cell apoptosis and necrosis. Considering the excessive cytotoxicity of the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group at high compound concentrations, a lower concentration of 5 μM was selected for the subsequent cellular experiments to avoid excessive cell death. As shown in Fig. 3e, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group induced 57.3 % cell apoptosis/necrosis, which was significantly higher than those of other control groups (cell apoptosis/necrosis ranging from 1.5 % to 16.2 %). These results aligned with those of the CCK-8 assays and live/dead staining, demonstrating the maximized cytotoxicity of combinational therapy of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles on 4T1 cells.

Next, we investigated the role of biotin in enhancing the combinational therapeutic efficacy of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles using biotin blocking experiments. In detail, 4T1 cells were pre-incubated with free biotin for 2 h to block biotin receptors (i.e., avidins) on 4T1 cells, followed by treatment with 10 μM free IR775, IR-FFKK, or IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. After 4 h of incubation, the residual drugs were washed off. Then, for fluorescence imaging analyses, 4T1 cells were directly subjected to fluorescence-microscopic imaging to assess the cellular uptake of the above compounds. For cytotoxicity evaluation, after 4 h incubation, the 4T1 cells were irradiated with an 808 nm laser (5 min, 1 W cm−2) and the cells were cultured for an additional 24 h before CCK-8 assay (Fig. S39a). As shown in Fig. S39b, in the absence of biotin, after 4 h incubation, all three groups showed strong red FL, indicating effective cellular uptake of the three compounds. In the presence of biotin, while cells treated with free IR775 showed similar strong FL similar to that of its non-blocked counterpart, cells treated with IR-FFKK or IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles exhibited significantly lower FL than that of their corresponding non-blocked control groups. These results indicated that, with the targeting warhead (i.e., biotin), cellular uptake of IR-FFKK or IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles is obviously improved. Cellular uptake directly affects the therapeutic efficacies of the compounds, as evidenced by following cytotoxicity studies. In the presence of biotin, cell viabilities of the IR-FFKK + Laser and the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser groups improved to 70.3 % and 60.1 % (Fig. S39c), while those were 22.1 % and 1.3 % in the absence of biotin (Fig. 3c), respectively. For CPT + IR + Laser group which does not have biotin targeting, in the presence/absence of biotin, cell viability was not significantly affected (12.8 %/11.3 %) (Figs. S39c and 3c). These results collectively demonstrated the vital role of biotin targeting in enhancing cellular uptake of IR-FFKK-CPT, as well as its therapeutic effects.

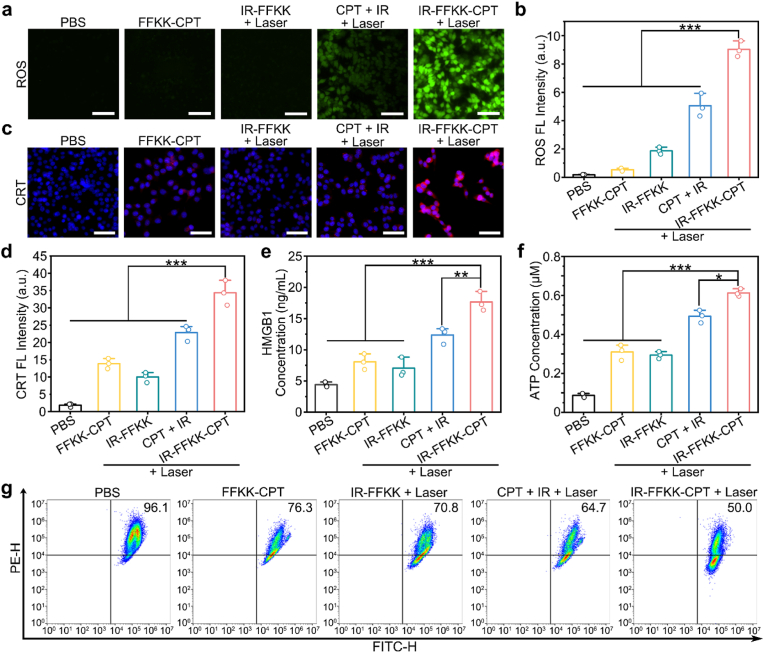

2.4. Investigation of underlying maximized apoptosis mechanisms of IR-FFKK-CPT

Next, we investigated the underlying maximized apoptosis mechanisms of combinational therapy on 4T1 cells. Previous studies have proved that reactive oxygen species (ROS) act as key mediators of apoptotic signaling, triggering mitochondrial damage, caspase activation, and oxidative DNA injury [54]. Therefore, we detected ROS levels using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), which indicates ROS with green fluorescence. Notably, among the eight groups studied, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group exhibited the strongest green FL, indicating the highest cellular ROS level in this group (Fig. 4a and S40a). Further quantitative analyses of the FL intensity in each group revealed that the FL intensity of the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group was 1.8- to 49.4-fold of that of control groups (Fig. 4b and S40b). These results demonstrated that the combinational therapy of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles rendered the highest ROS level to induce cell apoptosis. Considering that apoptosis can also exhibit immunogenic features, where cancer cells undergo immunogenic cell death (ICD) and release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), stimulating anti-tumor immunity [55]. Thus, we investigated the release of the key DAMPs, including calreticulin (CRT), high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), to explore the immunogenic potential of our combinational treatment strategy with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles [56,57]. We performed immunofluorescence staining to visualize the surface exposure levels of CRT on 4T1 cells. Notably, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group exhibited the strongest red FL among all groups, indicating the highest CRT exposure in this group (Fig. 4c and S41a). Further quantitative analyses of the FL intensity in each group revealed that the FL intensity of the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group was 1.5- to 18.9-fold of that of control groups (Fig. 4d and S41b). Next, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were employed to quantitatively assess the extracellular release of HMGB1 and ATP. As shown in Fig. 4e and f, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group showed the highest HMGB1 and ATP levels (4.0-fold and 7.1-fold of those of PBS group, respectively). In contrast, HMGB1 and ATP levels of the positive control groups were 1.6- to 2.8-fold and 3.4- to 5.7-fold of those of PBS group, respectively. These results collectively confirmed that combinational therapy with IR-FFKK-CPT could effectively induce ICD of the cancer cells. Mitochondrial integrity is essential to apoptosis, as mitochondrial membrane permeabilization leads to the release of pro-apoptotic factors, activating caspase-dependent cell death [58]. Given that IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles preferentially accumulated in mitochondria, the PTT-induced hyperthermia was speculated to disrupt mitochondrial integrity, subsequently triggering cell apoptosis. To verify this, we evaluated mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) disruption using JC-1 probes. JC-1 aggregates (red FL) indicate intact mitochondria with high MMP, while JC-1 monomers (green FL) represent mitochondrial depolarization and dysfunction. Compared to other groups, cells in the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group showed the mostly depolarized and dysfunctional mitochondria (Fig. 4g and Fig. S42). Collectively, these findings demonstrated that IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser treatment could enhance cancer cell apoptosis via three main pathways including cellular ROS production, ICD-associated DAMP release, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Fig. 4.

(a) Detection of ROS levels in 4T1 cells with DCFH-DA after incubation with PBS, 5 μM FFKK-CPT, 5 μM IR-FFKK, 5 μM CPT + 5 μM IR, or 5 μM IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. Specifically, the IR-FFKK, CPT + IR, and IR-FFKK-CPT groups were irradiated by 808 nm laser (5 min, 1 W cm−2) after 4 h incubation. Scale bar: 50 μm. (b) Relative FL intensity of DCFH-DA in a (mean ± SD, n = 3, ∗∗∗P < 0.001). (c) Images of calreticulin (CRT) immunofluorescence-staining in 4T1 cells after different treatments identical with those in a. Scale bar: 50 μm. (d) Quantitative analysis of CRT FL intensity in c (mean ± SD, n = 3, ∗∗∗P < 0.001). Quantitative results of released (e) HMGB1 and (f) ATP from 4T1 cells after different treatments identical with those in a (mean ± SD, n = 3, ∗P < 0.01, ∗∗P < 0.005, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001). (g) Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 probes via flow cytometry analysis after different treatments identical with those in a.

2.5. Validation of the FL-guided backtracking strategy in vivo

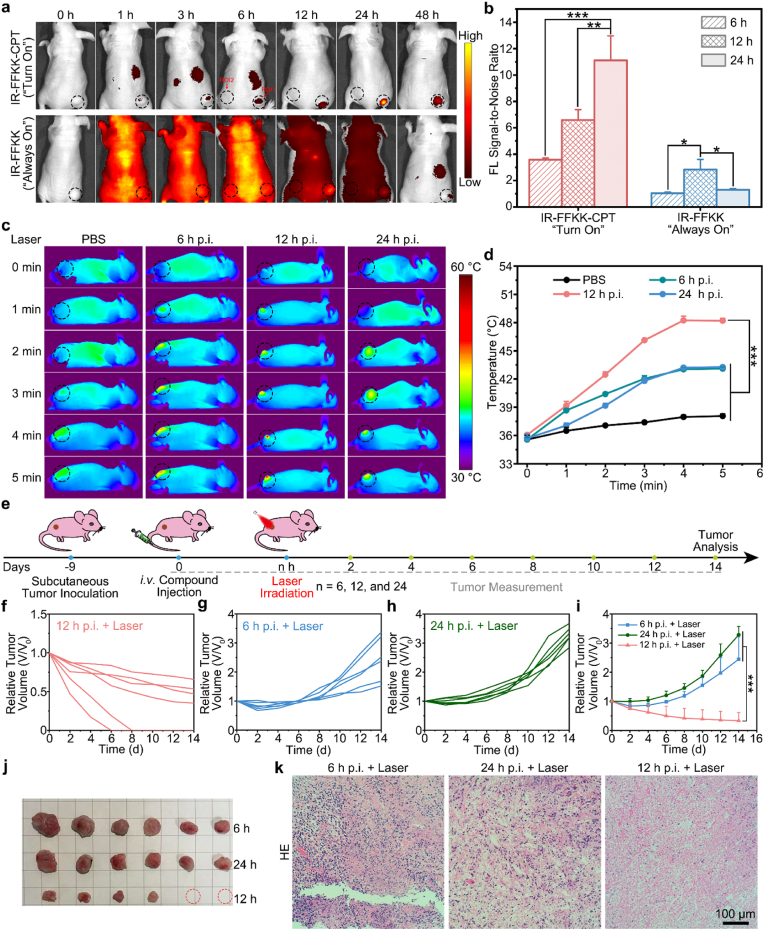

Encouraged by the above positive results of cellular experiments, we sought to validate the feasibility of the FL-guided backtracking strategy for determining the optimal PTT irradiation timing in vivo. A subcutaneous 4T1 tumor model was established by injecting 4T1 cells into the right flanks of nude mice. Nine days post-inoculation of tumors, mice were intravenously administered with 100 μL of 0.05 μmol kg−1 IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles (“Turn On” group) or IR-FFKK (“Always On” group). Then, we conducted real-time fluorescence imaging on mice using a small animal imaging system. As shown in Fig. 5a, FL in the “Turn On” group progressively increased from 1 h to 12 h post-injection (p.i.) and concentrated within tumor regions at 12 h. After that, tumor FL brightened, reached its plateau at 24 h, and declined at 48 h with detectable intensity. These suggested that the IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles might maximally accumulate in tumor region at 12 h but be disassembled by tumor CES at 24 h. Accordingly, tumor FL of IR-FFKK in the “Always On” group showed a continuous increase with 6 h, reached its plateau at 12 h p.i., and started to decline until 24 h. We then hypothesized that, for IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles, 12 h p.i. should be the optimized timing for tumor PTT. To validate this, we quantitated FL signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) of tumor (ROI1) to healthy tissue (ROI2) of IR-FFKK and IR-FFKK-CPT groups in Fig. 5a. As shown in Fig. 5b and S43, SNRs of the “Turn On” group of IR-FFKK-CPT continuously increased, specifically with values of 3.6, 6.6, and 11.1 for 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, respectively. In contrast, SNRs of the “Always On” group of IR-FFKK increased first, peaked at 12 h, and then declined, with values of 1.4, 2.8, and 1.3, respectively. Moreover, at all the time points (except 0 h), the SNRs in the “Turn On” group were higher than those in the “Always On” group, suggesting the superior tumor-targeting specificity and enhanced FL imaging contrast of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. These results collectively indicated that 12 h p.i. should be the optimal irradiation timing on IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles for tumor PTT, and the nanoparticles were maximally disassembled by CES in tumors at 24 h with bright “Turn On” FL. To verify our hypothesis, we conducted photothermal imaging of the 4T1 tumors. The tumor-bearing nude mice were intravenously injected with 20 μmol kg−1 IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles and then subjected to 808 nm laser irradiation (5 min, 1 W cm−2) at six time points (i.e., 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, or 48 h p.i.). Real-time infrared thermal imaging was used to monitor tumor temperature during irradiation. As shown in Fig. 5c and S44a, at any time point post injection, tumor temperatures showed irradiation time-dependent increase. And tumor temperatures of 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h were higher than those of 1 h, 3 h, or 48 h, accordingly. Quantitative results showed that after 5 min of irradiation (808 nm, 1 W cm−2), the irradiation at 12 h p.i. obtained the highest tumor temperature increase of 12.1 °C which was significantly higher than those of 6 h (7.5 °C) and 24 h (7.6 °C) (Fig. 5d), or those of other time points (Fig. S44b). These results directly suggested that the 12 h p.i. was the optimal PTT timing for tumor irradiation to achieve the maximal photothermal efficiency of IR-FFKK-CPT.

Fig. 5.

(a) Fluorescence images of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after intravenous injection of 0.05 μmol kg−1IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles (“Turn On” group) or IR-FFKK (“Always On” group) at different time points. (b) SNRs of FL intensity at 6, 12, and 24 h p.i. in a, calculated by ROI1/ROI2. ROI1 represents the right leg circle area (tumor area), and ROI2 represents the left hind leg area (healthy tissue) in each photo, respectively (mean ± SD, n = 3, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001). (c) Representative thermal images of mice exposed to laser (808 nm, 1 W cm−2) after intravenous injection of PBS or IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles at different time points. (d) Quantitative temperature changing curves at tumor sites of each mouse in c. (e) Schematic illustration of subcutaneous 4T1 tumor implantation, compound injection, laser irradiation, and tumor analysis. Changing curves of relative tumor volume of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after drug injection, and tumor tissues were irradiated by laser (808 nm, 1 W cm−2) at different time points as 12 h p.i. (f), 6 h p.i. (g) and 24 h p.i. (h). (i) Quantitative analyses of the relative tumor volume of mice irradiated at 6 h, 24 h, and 12 h during the 14-day period (mean ± SD, n = 6, ∗∗∗P < 0.001) (j) Photographs of excised tumors from mice irradiated at 6 h, 24 h, and 12 h at 14 d. (k) HE images of the tumor sections from mice irradiated at 6 h, 24 h, and 12 h at 14 d.

Next, we validated that the irradiation timing at 12 h p.i. could maximize the therapeutic efficacy of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles in vivo. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with 20 μmol kg−1 IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles, irradiated at 6 h, 12 h, or 24 h p.i. (808 nm laser, 1 W cm−2, 5 min), and tumor growth was monitored for 14 days (Fig. 5e). As shown in Fig. 5f, all the 6 mice in the 12 h p.i. + Laser group showed sustained tumor suppression during 14-day observation, and 2 of them achieved complete tumor eradication. In contrast, mice in the 6 h p.i. + Laser or 24 h p.i. + Laser group showed partial tumor inhibition during the first 6 days but rapid tumor regrowth thereafter (Fig. 5g and h). Quantitative analyses of the relative tumor volume showed that, on day 14, the relative tumor volume of the 12 h p.i. + Laser group was 13.7 % or 10.2 % of that of the 6 h p.i. + Laser or 24 h p.i. + Laser group, respectively (Fig. 5i). Photographs of the tumors of the above three groups were displayed in Fig. 5j. In addition, as shown in Fig. S45, the excised tumor weight of the 12 h p.i. + Laser group was 0.1 g, which was significantly lower than that of the 6 h p.i. + Laser group (0.4 g) or 24 h p.i. + Laser group (0.3 g). Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of the tumor sections showed the largest number of dead cancer cells in 12 h p.i. group, while substantial number of living cancer cells in the 6 h p.i. + Laser or 24 h p.i. + Laser group (Fig. 5k). These results demonstrated that 12 h p.i. was indeed the optimal PTT irradiation timing for tumor irradiation to achieve the maximal photothermal efficiency of IR-FFKK-CPT.

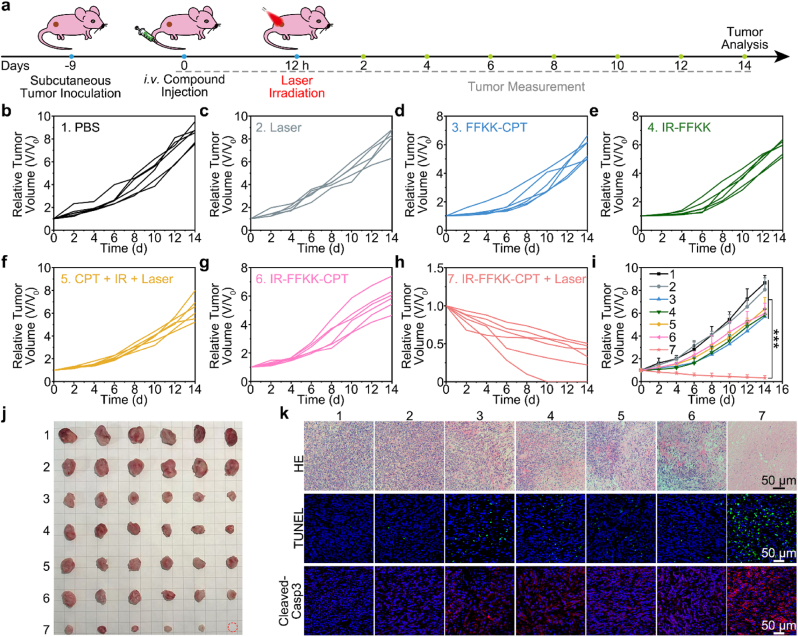

2.6. Evaluation of maximized anticancer efficacy of IR-FFKK-CPT in vivo

With the optimal irradiation timing of 12 h p.i. selected, we then compared our maximized combinational therapy of IR-FFKK-CPT with other therapies (individual chemotherapy, individual PTT, or chemotherapy + PTT) in vivo. To do this, two negative control groups (i.e. PBS and Laser) and four positive control groups (i.e., FFKK-CPT for chemotherapy-only, IR-FFKK + Laser for PTT only, CPT + IR + Laser for chemotherapy + PTT, and IR-FFKK-CPT for chemotherapy-only) were designed. Nude mice bearing subcutaneous 4T1 tumors on the right flanks were intravenously administered 20 μmol kg−1 of different compounds on day 9 post-inoculation and then irradiated by 808 nm laser (1 W cm−2, 5 min) at 12 h p.i. Tumor volumes were measured every two days, and mice were euthanized on day 14 for tumor analyses (Fig. 6a). As shown in Fig. 6b and c, the two negative control groups (i.e. PBS and Laser) showed negligible impact on tumor growth, with tumors rapidly growing over the 14-day period. In addition, four positive control groups showed limited therapeutic efficacy on tumors (Fig. 6d–g). In contrast, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group showed the most effective tumor suppression throughout the 14-day period, with one mouse achieving complete tumor eradication (Fig. 6h). Quantitative tumor growth analyses revealed that, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group exhibited an excellent tumor growth inhibition rate of 96.2 %, significantly higher than those observed in the four positive control groups (i.e., Laser group: 6.8 %, FFKK-CPT group: 34.1 %, IR-FFKK + Laser group: 32.6 %, CPT + IR + Laser group: 26.3 %, and IR-FFKK-CPT group: 31.2 %) (Fig. 6i). Excised tumor images on day 14 confirmed that tumors in the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group were significantly smaller than those in all control groups (Fig. 6j). Additionally, the average excised tumor weight in the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group was the lowest among those of all the groups (Fig. S46). These results demonstrated the significantly maximized tumor inhibition of our combinational therapy with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles. We then performed HE staining on excised tumor tissues to assess the cancer cell death after different treatments. As shown in Fig. 6k, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group exhibited the most significant cancer cell death over all six control groups. Moreover, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining and cleaved-caspase-3 (Cleaved-Casp3) immunofluorescence staining were employed to assess cell apoptosis in tumor tissues. As shown in Fig. 6k, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group showed the strongest green TUNEL FL and red Cleaved-Casp3 FL. Further quantitative analyses revealed that the TUNEL and Cleaved-Casp3 FL intensity ratios of the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group were 2.5- to 7.6-fold and 2.0- to 9.0-fold of those of control groups, respectively (Fig. S47). These findings demonstrated that the combinational therapy with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles significantly maximized tumor apoptosis in vivo. Additionally, we conducted hemolysis assays to examine the biocompatibility of different compounds (i.e., FFKK-CPT, IR-FFKK, CPT + IR, and IR-FFKK-CPT). As shown in Fig. S48, there was no significant hemolysis in any group, suggesting excellent hemocompatibility of these compounds. Body weight monitoring results showed no significant weight loss in any treatment group during the 14-day period, suggesting good biosafety of these treatments (Fig. S49a). Furthermore, histological analysis of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys) from both healthy and IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser-treated mice indicated no observable pathological abnormalities, confirming negligible side effects of the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser treatment (Fig. S49b). These results collectively demonstrated the good biocompatibility and biosafety of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticle, supporting its potential for future clinical translation.

Fig. 6.

(a) Schematic illustration of subcutaneous 4T1 tumor implantation, compound injection, laser irradiation, and tumor analysis. (b–h) Changing curves of relative tumor volume of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after different treatments as indicated. (i) Quantitative analyses of the relative tumor volume of mice in different groups (mean ± SD, n = 6, ∗∗∗P < 0.001). (j) Photographs of the excised tumors from mice in different groups at 14 d. (k) HE images, TUNEL staining, and Cleaved-Casp3 immunofluorescence staining of the excised tumors from the mice in different groups at 14 d.

3. Conclusions

In summary, we proposed a timed PTT combining FL-on chemotherapy strategy, leveraging FL-guided backtracking to precisely determine optimal PTT irradiation timing, to maximize tumor treatment. We rationally designed a peptide-drug conjugate IR-FFKK-CPT, which spontaneously self-assembles into nanoparticles with average diameter of 180.9 ± 5.1 nm. Upon CES-mediated cleavage, IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles were hydrolysed to yield hydrophilic products IR-FFKK, leading to nanoparticle disassembly and a 30.1-fold increase in FL intensity, simultaneously reducing their photothermal performance. Cellular confocal FL imaging showed that FL intensity peaked at 6 h post-incubation with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles in 4T1 cells. indicating the optimal irradiation timing should be ahead of 6 h. Thermal imaging of 4T1 cells indicated that cells incubated with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles for 4 h exhibited the highest temperature increase, which was1.4-fold or 1.6-fold of that in 2 h or 6 h group, respectively, suggesting the optimal PTT irradiation timing be 4 h post-incubation. Bio-TEM imaging and co-localization experiments confirmed that IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles preferred to localize in mitochondria. Notably, at compound concentration of 20 μM, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group exhibited the strongest cell killing effects (cell viability of 1.3 %) over those of the positive control groups (FFKK-CPT: 46.3 %, IR-FFKK + Laser: 22.1 %, and CPT + IR + Laser: 11.3 %), demonstrating the excellent therapeutic efficacy of combinational therapy with optimal irradiation timing. Furthermore, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser treatment could induce maximized tumor apoptosis via cellular ROS production, ICD-associated DAMP release, and mitochondrial dysfunction, as evidenced by the highest levels of apoptosis-related biomarkers (i.e., ROS, CRT, HMGB1, and ATP) and the strongest mitochondrial damage over all control groups. We further validated the FL-guided backtracking strategy in vivo. Real time FL imaging of the tumor-bearing mice injected with IR-FFKK-CPT showed that tumor FL peaked at 24 h p.i., indicating that the optimal irradiation timing should be ahead of this time point. Therefore, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h p.i. were selected to further investigate the optimal irradiation timing in vivo. Thermal imaging showed that the 12 h p.i. group exhibited the highest temperature increase (12.1 °C) at the tumor site upon 808 nm laser irradiation, which was 1.6-fold of that in 6 h p.i. group (7.5 °C) or 24 h p.i. group (7.6 °C). Notably, mice intravenously injected with IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles and irradiated at 12 h p.i. exhibited the best tumor inhibition, with the average relative tumor volume on day 14 being 13.7 % or 10.2 % of that in the 6 h p.i. or 24 h p.i. group, respectively. These results demonstrated the therapeutic advantage of precise irradiation timing in the combinational therapy. With the optimal irradiation timing of 12 h p.i., we further compared our maximized combinational therapy of IR-FFKK-CPT with other therapies in vivo. As expected, the IR-FFKK-CPT + Laser group exhibited the strongest inhibition of the tumors with tumor inhibition rate of 96.2 %. In contrast, single therapy or separated chemotherapy + PTT failed to suppress tumor growth, with tumor inhibition rate ranging from 26.3 % to 34.1 %. Finally, excellent biosafety and biocompatibility of IR-FFKK-CPT nanoparticles were demonstrated by the hemolysis assays and the histological analysis of major organs of the mice. Our work introduces an FL-guided backtracking strategy for optimal irradiation timing of PTT combined with chemotherapy to maximize tumor treatment. We anticipate that IR-FFKK-CPT be applied for effective tumor treatment in clinic in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Runqun Tang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ziyi Zhang: Writing – original draft, Methodology. Xiaoyang Liu: Methodology, Investigation. Hai-Dong Xu: Methodology, Investigation. Liangxi Zhu: Methodology. Xueqi Bai: Methodology. Yinxing Miao: Investigation. Wenjun Zhan: Methodology, Investigation. Zhonghua Shi: Resources, Methodology, Investigation. Gaolin Liang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal research processes were approved and supervised by the Southeast University Animal Care Committee (Permission number: 20241101004). All the authors were in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant 2023YFF0724100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 22234002), and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant BK20232007). We acknowledge the Analysis and Testing Center of Southeast University for instrumentation and technical support.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of editorial board of Bioactive Materials.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.07.051.

Contributor Information

Zhonghua Shi, Email: szh@njmu.edu.cn.

Gaolin Liang, Email: gliang@seu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

All the data of this study can be acquired from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Arafeh R., Shibue T., Dempster J.M., Hahn W.C., Vazquez F. The present and future of the cancer dependency map. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2025;25(1):59–73. doi: 10.1038/s41568-024-00763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tannock I.F. Conventional cancer therapy: promise broken or promise delayed? Lancet. 1998;351:SII9–SII16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyld L., Audisio R.A., Poston G.J. The evolution of cancer surgery and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12(2):115–124. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Ruysscher D., Niedermann G., Burnet N.G., Siva S., Lee A.W.M., Hegi-Johnson F. Radiotherapy toxicity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2019;5(1):13. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chabner B.A., Roberts T.G. Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5(1):65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer A.C., Sorger P.K. Combination cancer therapy can confer benefit via patient-to-patient variability without drug additivity or synergy. Cell. 2017;171(7):1678–1691.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gotwals P., Cameron S., Cipolletta D., Cremasco V., Crystal A., Hewes B., Mueller B., Quaratino S., Sabatos-Peyton C., Petruzzelli L., Engelman J.A., Dranoff G. Prospects for combining targeted and conventional cancer therapy with immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17(5):286–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayat Mokhtari R., Homayouni T.S., Baluch N., Morgatskaya E., Kumar S., Das B., Yeger H. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(23):38022–38043. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu L., Liu Y., Zeng W., Ishigaki Y., Zhou S., Wang X., Sun Y., Zhang Y., Jiang X., Suzuki T., Ye D. Smart lipid nanoparticle that remodels tumor microenvironment for activatable H2S gas and photodynamic immunotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145(50):27838–27849. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c11328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sauer R., Becker H., Hohenberger W., Rödel C., Wittekind C., Fietkau R., Martus P., Tschmelitsch J., Hager E., Hess Clemens F., Karstens Johann H., Liersch T., Schmidberger H., Raab R. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351(17):1731–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper Jay S., Pajak Thomas F., Forastiere Arlene A., Jacobs J., Campbell Bruce H., Saxman Scott B., Kish Julie A., Kim Harold E., Cmelak Anthony J., Rotman M., Machtay M., Ensley John F., Chao K.S.C., Schultz Christopher J., Lee N., Fu Karen K. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350(19):1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breugom A.J., Swets M., Bosset J.-F., Collette L., Sainato A., Cionini L., Glynne-Jones R., Counsell N., Bastiaannet E., van den Broek C.B.M., Liefers G.-J., Putter H., van de Velde C.J.H. Adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and surgery for patients with rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):200–207. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maduro J.H., Pras E., Willemse P.H.B., de Vries E.G.E. Acute and long-term toxicity following radiotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2003;29(6):471–488. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoop T.F., Theijse R.T., Seelen L.W.F., Groot Koerkamp B., van Eijck C.H.J., Wolfgang C.L., van Tienhoven G., van Santvoort H.C., Molenaar I.Q., Wilmink J.W., Del Chiaro M., Katz M.H.G., Hackert T., Besselink M.G. C. International collaborative group on locally advanced pancreatic, preoperative chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgical decision-making in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024;21(2):101–124. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overchuk M., Weersink R.A., Wilson B.C., Zheng G. Photodynamic and photothermal therapies: synergy opportunities for nanomedicine. ACS Nano. 2023;17(9):7979–8003. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c00891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao G., Sun X., Liang G. Nanoagent-promoted mild-temperature photothermal therapy for cancer treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31(25) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao G., Sun X., Liu X., Jiang Y.-W., Tang R., Guo Y., Wu F.-G., Liang G. Intracellular nanoparticle formation and hydroxychloroquine release for autophagy-inhibited mild-temperature photothermal therapy for tumors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31(34) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Du W., Zhang T., Zhu Y., Ni Y., Wang C., Sierra Raya F.M., Zou L., Wang L., Liang G. A self-evaluating photothermal therapeutic nanoparticle. ACS Nano. 2020;14(8):9585–9593. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Z., Hu K., Ma R., Yan Y., Ni B., Zhang Y., Wen L., Zhang Q., Cheng Y. Dendritic platinum–copper alloy nanoparticles as theranostic agents for multimodal imaging and combined chemophotothermal therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26(33):5971–5978. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L., Su H., Cai J., Cheng D., Ma Y., Zhang J., Zhou C., Liu S., Shi H., Zhang Y., Zhang C. A multifunctional platform for tumor angiogenesis-targeted chemo-thermal therapy using polydopamine-coated gold nanorods. ACS Nano. 2016;10(11):10404–10417. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b06267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su S., Ding Y., Li Y., Wu Y., Nie G. Integration of photothermal therapy and synergistic chemotherapy by a porphyrin self-assembled micelle confers chemosensitivity in triple-negative breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2016;80:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nam J., Son S., Ochyl L.J., Kuai R., Schwendeman A., Moon J.J. Chemo-photothermal therapy combination elicits anti-tumor immunity against advanced metastatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):1074. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ni W., Wu J., Fang H., Feng Y., Hu Y., Lin L., Chen J., Chen F., Tian H. Photothermal-chemotherapy enhancing tumor immunotherapy by multifunctional metal–organic framework based drug delivery system. Nano Lett. 2021;21(18):7796–7805. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c02782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang G., Chen X., Chen X., Du K., Ding K., He D., Ding D., Hu R., Qin A., Tang B.Z. Click-reaction-mediated chemotherapy and photothermal therapy synergistically inhibit breast cancer in mice. ACS Nano. 2023;17(15):14800–14813. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c03005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan W., Yung B., Huang P., Chen X. Nanotechnology for multimodal synergistic cancer therapy. Chem. Rev. 2017;117(22):13566–13638. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan Y.-J., Zhang Y., Chen B.-Q., Zhao Y., Wang J.-Y., Li C.-Y., Zhang D.-G., Kankala R.K., Wang S.-B., Liu G., Chen A.-Z. NIR-II light triggered burst-release cascade nanoreactor for precise cancer chemotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2024;33:311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulbrich K., Holá K., Šubr V., Bakandritsos A., Tuček J., Zbořil R. Targeted drug delivery with polymers and magnetic nanoparticles: covalent and noncovalent approaches, release control, and clinical studies. Chem. Rev. 2016;116(9):5338–5431. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J., Jiang X., Ashley C., Brinker C.J. Electrostatically mediated liposome fusion and lipid exchange with a nanoparticle-supported bilayer for control of surface charge, drug containment, and delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131(22):7567–7569. doi: 10.1021/ja902039y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin X.C., Guo Z.Y., Liu Z.M., Zhang W., Wan M.M., Yang B.W. Folic acid-conjugated graphene oxide for cancer targeted chemo-photothermal therapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2013;120:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X., Li F., Liang R., Liu W., Ma H., Lan T., Liao J., Yang Y., Yang J., Liu N. A smart benzothiazole-based conjugated polymer nanoplatform with multistimuli response for enhanced synergistic chemo-photothermal cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023;15(13):16343–16354. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c19246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mu R., Zhu D., Abdulmalik S., Wijekoon S., Wei G., Kumbar S.G. Stimuli-responsive peptide assemblies: design, self-assembly, modulation, and biomedical applications. Bioact. Mater. 2024;35:181–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Q., Zhou Z., Qiu N., Shen Y. Rational design of cancer nanomedicine: nanoproperty integration and synchronization. Adv. Mater. 2017;29(14) doi: 10.1002/adma.201606628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang D.-C., Wen L.-F., Du L., Luo C.-M., Lu Z.-Y., Liu J.-Y., Lin Z. A hypoxia-activated prodrug conjugated with a BODIPY-based photothermal agent for imaging-guided chemo-photothermal combination therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022;14(36):40546–40558. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c09071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiong Y., Rao Y., Hu J., Luo Z., Chen C. Nanoparticle-based photothermal therapy for breast cancer noninvasive treatment. Adv. Mater. 2023 doi: 10.1002/adma.202305140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oudjedi F., Kirk A.G. Near-infrared nanoparticle-mediated photothermal cancer therapy: a comprehensive review of advances in monitoring and controlling thermal effects for effective cancer treatment. Nano Sel. 2025;6(3) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang L., Chen Z., Dai J., Pan Y., Tu Y., Meng Q., Diao Y., Yang S., Guo W., Li L., Liu J., Wen H., Hua K., Hang L., Fang J., Meng X., Ma P.a., Jiang G. Recent advances in strategies to enhance photodynamic and photothermal therapy performance of single-component organic phototherapeutic agents. Adv. Sci. 2025;12(7) doi: 10.1002/advs.202409157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng L., Zhang F., Wang S., Pan X., Han S., Liu S., Ma J., Wang H., Shen H., Liu H., Yuan Q. Activation of prodrugs by NIR-triggered release of exogenous enzymes for locoregional chemo-photothermal therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58(23):7728–7732. doi: 10.1002/anie.201902476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C., Ou H., Liu R., Ding D. Regulating the photophysical property of organic/polymer optical agents for promoted cancer phototheranostics. Adv. Mater. 2020;32(3) doi: 10.1002/adma.201806331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao H., Xu J., Huang W., Zhan G., Zhao Y., Chen H., Yang X. Spatiotemporally light-activatable platinum nanocomplexes for selective and cooperative cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2019;13(6):6647–6661. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b00972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H., Di Y., Chen D., Madrid K., Zhang M., Tian C., Tang L., Gu Y. Combined chemo- and photo-thermal therapy delivered by multifunctional theranostic gold nanorod-loaded microcapsules. Nanoscale. 2015;7(19):8884–8897. doi: 10.1039/c5nr00473j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhi D., Yang T., O'Hagan J., Zhang S., Donnelly R.F. Photothermal therapy. J. Contr. Release. 2020;325:52–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhen X., Zhang J., Huang J., Xie C., Miao Q., Pu K. Macrotheranostic probe with disease-activated near-infrared fluorescence, photoacoustic, and photothermal signals for imaging-guided therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57(26):7804–7808. doi: 10.1002/anie.201803321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang D., Zhang J., Li Q., Tian H., Zhang N., Li Z., Luan Y. pH- and enzyme-sensitive IR820–paclitaxel conjugate self-assembled nanovehicles for near-infrared fluorescence imaging-guided chemo–photothermal therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10(36):30092–30102. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b09098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L., Wang X., Zhao J., Sun B., Wang W. Construction of targeting-peptide-based imaging reagents and their application in bioimaging. Chem. Biomed. Imaging. 2024;2(4):233–249. doi: 10.1021/cbmi.3c00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dou W.-T., Guo C., Zhu L., Qiu P., Kan W., Pan Y.-F., Zang Y., Dong L.-W., Li J., Tan Y.-X., Wang H.-Y., He X.-P. Targeted near-infrared fluorescence imaging of liver cancer using dual-peptide-functionalized Albumin particles. Chem. Biomed. Imaging. 2024;2(1):47–55. doi: 10.1021/cbmi.3c00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma D., Bian H., Gu M., Wang L., Chen X., Peng X. Recent advances in the design and applications of near-infrared II responsive small molecule phototherapeutic agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024;505 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y., Ren J., Shuai Z. Minimizing non-radiative decay in molecular aggregates through control of excitonic coupling. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):5056. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40716-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dai H., Pan J., Shao J., Xu K., Ruan X., Mei A., Chen P., Qu L., Dong X. Boosting nonradiative decay of boron difluoride formazanate dendrimers for NIR-II photothermal theranostics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025 doi: 10.1002/anie.202503718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo N., Liu L., Luo J., Zhou Z., Sun C.-L., Hua X., Luo L., Wang J., Geng H., Shao X., Zhang H.-L., Liu Z. Alternating donor-acceptor ladder-type heteroarene for efficient photothermal conversion via boosting non-radiative decay. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025;64(6) doi: 10.1002/anie.202418047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang H., Feng Z., Xu B. Intercellular instructed-assembly mimics protein dynamics to induce cell spheroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141(18):7271–7274. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b03346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao J., Zhan J., Yang Z. Enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA) and hydrogelation of peptides. Adv. Mater. 2020;32(3) doi: 10.1002/adma.201805798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao G., Jiang Y.-W., Zhan W., Liu X., Tang R., Sun X., Deng Y., Xu L., Liang G. Trident molecule with nanobrush–nanoparticle–nanofiber transition property spatially suppresses tumor metastasis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144(26):11897–11910. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c05743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sedgwick P. Pearson's correlation coefficient. BMJ Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2012;345 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matés J.M., Sánchez-Jiménez F.M. Role of reactive oxygen species in apoptosis: implications for cancer therapy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2000;32(2):157–170. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kroemer G., Galluzzi L., Kepp O., Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:51–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang X., Lu Y., Guo M., Du S., Han N. Recent strategies for nano-based PTT combined with immunotherapy: from a biomaterial point of view. Theranostics. 2021;11(15):7546–7569. doi: 10.7150/thno.56482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sweeney E.E., Cano-Mejia J., Fernandes R. Photothermal therapy generates a thermal window of immunogenic cell death in neuroblastoma. Small. 2018;14(20) doi: 10.1002/smll.201800678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kroemer G., Dallaporta B., Resche-Rigon M. The mitochondrial death/life regulator in apoptosis and necrosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1998;60:619–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data of this study can be acquired from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.