Abstract

Congenital bile acid synthesis disorder type 1 is an extremely rare disease with around 100 cases identified worldwide. Diagnosis remains challenging for pediatricians in view of the non-specific, variable clinical presentations of cholestasis, fat malabsorption, and liver cirrhosis. Early diagnosis and therapy with cholic acid are crucial to reverse the hepatopathy and prevent fatal outcomes. This paper sheds light on the diagnostic challenges of congenital bile acid synthesis disorder type 1 in a patient with an unusual presentation and a previously unreported mutation in the HSD3B7 gene. Moreover, this report aims to increase awareness of this treatable disorder among pediatricians. A 4-year-old child presented to our Medical Center with splenomegaly, fever, multiple lymphadenopathies, and mild cholestasis without hepatomegaly. History was remarkable for recurrent infections since the age of 3 years. Differential diagnosis included viral infections, malignancies, and inherited metabolic disorders. After an extensive negative work-up, genetic testing by next-generation sequencing identified a previously unreported homozygous disease-causing variant in the HSD3B7 gene, confirming the diagnosis of congenital bile acid synthesis disorder type 1. Suggestive abnormal urinary bile acids metabolites were also identified. Bile acid replacement therapy was initiated with reversal of cholestasis. This case highlights an unusual phenotypic presentation and the diagnostic challenges of an extremely rare disorder of bile acid synthesis. An increased awareness among pediatricians and the use of next-generation sequencing as a first-tier test in the setting of non-specific clinical presentations may shortcut the list of extensive investigations, allowing an early diagnosis of such treatable disorders, thus improving the patients’ outcomes.

Keywords: bile acid synthesis disorder, HSD3B7 gene, cholic acid, exome sequencing, case report

Introduction

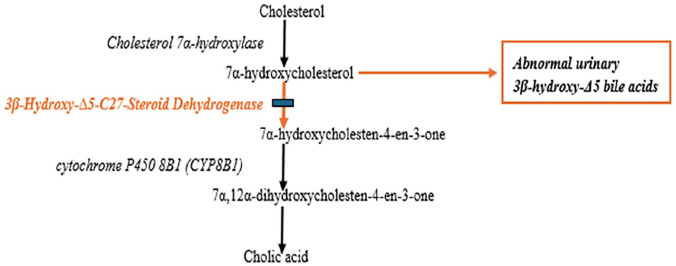

Congenital bile acid synthesis disorder type 1 (CBAS1; OMIM 607765) is an extremely rare inherited metabolic disease first described in 1987. 1 Since then, around 100 cases have been reported worldwide, in patients from Asian, 2 Arab, 3 and European 4 descent. It is secondary to 3β-Δ5-hydroxy-C27-steroid oxidoreductase (3β-HSD) enzyme deficiency associated to bi-allelic disease-causing variants in the HSD3B7 gene. This enzyme catalyzes the second step of the bile acids synthesis pathway, converting 7α-hydroxycholesterol to 7α-hydroxycholest-4-en-3-one leading ultimately to the formation of the primary bile acids, chenodeoxycholic acid and cholic acid. In case of 3β-HSD deficiency, 7α-hydroxycholesterol will be diverted to side-chain oxidation pathways producing abnormal 3β-hydroxy-Δ5-bile acids. These intermediate toxic metabolites accumulate in the liver causing bile-stasis related hepatotoxicity 5 and are excreted in high concentrations in the urine (Figure 1). 6

Figure 1.

Bile acids synthesis pathway: 3-5-hydroxy-C27-steroid oxidoreductase enzyme deficiency.

Biochemical diagnosis of this condition relies on urine bile acids spectrometry revealing an increased proportion of 3β-hydroxy-Δ5-bile acids. 7 HSD3B7 gene sequencing confirms the diagnosis. Cholestasis is the hallmark of this disorder, frequently present since the neonatal period.2,4 Few late-onset presentations are reported in the literature. 8 Manifestations usually include hepatomegaly with or without splenomegaly, cholestasis with normal gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and absence of pruritus, fat malabsorption leading to deficiency in fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) in addition to renal lesions in some cases. 2 Early diagnosis is critical since bile acid replacement therapy with cholic or chenodeoxycolic acid is effective in preventing liver cirrhosis and poor outcomes. 9

Here, we report an unusual presentation of CBAS1, associated to a previously unreported mutation in the HSD3B7 gene, in a 4-year-old girl with splenomegaly, fever, and diffuse lymphadenopathies. This peculiar case delineates the diagnostic challenges of an extremely rare yet treatable disorder.

Case Presentation

The patient, a 4-year-old girl, presented to the emergency department for fever, nausea without vomiting, and diarrhea of 5 days duration. For the past year, the patient has been having recurrent febrile episodes associated with upper respiratory tract symptoms for which she received multiple courses of antibiotics. Parents are first degree cousins and family history was positive for B lymphoblastic leukemia in a cousin. Neonatal history was positive for prolonged jaundice (9 days) requiring phototherapy, as per parents. On admission, all growth parameters were normal for age. The clinical examination was significant for splenomegaly with a normal liver span. Laboratory tests were remarkable for thrombocytopenia at 59 000 per cubic millimeter with mild cholestasis and normal gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) (Table 1). Abdomen and pelvis ultrasound as well as computed tomography scan (Figure 2) confirmed the presence of an enlarged spleen measuring 13 cm in length (normal for 3-5 years: 5.5-9.5 cm) with supra- and infra-diaphragmatic enlarged lymph nodes. The liver measured 8.2 cm (normal for 3-5 years: 6.5-11.5 cm) with mild heterogeneous echotexture. No renal abnormalities were detected.

Table 1.

Blood tests of a patient with congenital bile acid synthesis disorder type 1: at presentation and at follow-up.

| Variable | Values at presentation | Values at 1 month after presentation (before treatment) | Values at 6 months after treatment | Reference range for age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.3 | 10.5 | 13.2 | 9.5-14.0 |

| White blood cells (per cubic millimeter) | 3700 | 4800 | 4900 | 5000-17000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 1073 | 1800 | 2300 | 1500-11000 |

| Platelets (per cubic millimeter) | 59.000 | 63.000 | 89.000 | 150 000-400 000 |

| Bilirubin total (mg/dL) | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0-1.2 |

| Bilirubin direct (mg/dL) | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0-0.3 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 10 | 9 | 7 | ⩽40 |

| SGPT (IU/L) | 26 | 29 | 19 | 0-50 |

| SGOT (IU/L) | 61 | 52 | 9 | 0-50 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 174 | 198 | 170 | 142-335 |

| International normalized ratio | 2.7 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.9-1.2 |

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of abdomen and pelvis, coronal view: splenomegaly with normal liver size.

This constellation of findings was suggestive of a lymphoproliferative disorder. In view of the history and these findings, the differential diagnosis included viral infections, immunologic disorders, and malignancies.

Extensive infectious workup including blood, urine, stool, and bone marrow cultures, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus and brucella antibodies, toxoplasma, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, bartonella serologies, tuberculosis interferon gamma release assay, leishmania polymerase chain reaction as well as quantitative immunoglobulins, and immune profile was negative. Immunologic work-up was also performed: anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant. In addition, acute leukemia, lymphoma, and myelodysplastic syndromes were investigated by bone marrow aspirate/biopsy and positron emission tomography scan. All tests were negative. Fever, nausea, and diarrhea subsided within a week. Repeat abdominal ultrasound, 2 months after the initial presentation, revealed a resolution of the lymphadenopathies with persistence of the splenomegaly. At this point, the possibility of an inherited metabolic disorder (tyrosinemia type 1 or Gaucher disease) or a primary liver disease was considered. Plasma amino acids chromatography showed mildly increased tyrosine (219 umol/L; normal: 24-115) and methionine (57 umol/L; normal: 7-47) levels, suggestive of liver insult. Gaucher disease was ruled out by normal enzymatic assay activities in peripheral blood. Liver elastography by Fibroscan (Figure 3) showed a fibrosis score of F3 that represents severe fibrosis. Furthermore, echocardiography and ophthalmological exam were normal.

Figure 3.

Liver elastography (Fibroscan): severe fibrosis, F3 score.

Finally, exome sequencing study performed at a reference laboratory identified a homozygous frameshift mutation in the HSD3B7 gene: NM_025193.3: c.551del, p.(Leu184Argfs*2), classified as pathogenic according to the recommendations of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, confirming the diagnosis of CBAS1. Urine bile acids by liquid chromatography (LC/MS) 10 coupled to mass spectrometry was then sent to a reference laboratory outside the country revealing the presence of abnormal metabolites of 3β-Δ5-hydroxy-C27-steroid oxidoreductase (3β-HSD) deficiency (Table 2). Repeat blood tests 1 month after presentation revealed persistent thrombocytopenia at 63 000 per cubic millimeter (150 000-400 000) with stable liver markers (Table 1). In addition, low blood levels of fat-soluble vitamins were detected: vitamin E (1.3 mg/l; normal: 3.0-9.0 mg/L), Vitamin A (0.2 mg/l; normal: 0.20-0.50 mg/l), and Vitamin D (13.3 ng/ml; desirable: >25 ng/mL). Cholic acid therapy was initiated at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day along with fat-soluble vitamins supplementation. At follow-up 6 months later, cholestasis had resolved (Table 1), however the spleen size remained unchanged, and urinary abnormal bile acid metabolites increased (Table 2) necessitating an optimization of cholic acid dosing up to 15 mg/kg/day.

Table 2.

Urinary bile acids profile by LC/MS in a patient with congenital bile acid synthesis disorder type 1: at presentation and at 6 months after cholic acid therapy.

| Urine bile acids | At diagnosis µmol/L | At 6 months µmol/L | Reference range µmol/L |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | |||

| Glycocholic | <0.6 | 4.73 | <0.6 |

| Taurocholic | <0.6 | 0.85 | <0.6 |

| Glycochenodeoxycholic | 1.02 | 1.64 | 0 |

| Taurochenodeoxycholic | <0.6 | 0.62 | <0.6 |

| Secondary | |||

| Glycodeoxycholic | <0.6 | 1 | <0.6 |

| Taurodeoxycholic | <0.6 | 0.72 | <0.6 |

| Glycoursodeoxycholic | 0.00 | <0.6 | 0 |

| Tauroursodeoxycholic | 0.00 | <0.6 | 0 |

| Total physiologic bile acids | 3.42 | 10.14 | 0-10 |

| 3β-HSD deficiency metabolites | 85.8 | 496 | 0 |

| Percentage of abnormal bile acid metabolites | 96% | 96% | 0 |

Discussion

In this report, we describe the diagnostic challenges of a rare inherited metabolic disorder of bile acid synthesis. Only 53 cases were described up to 2017; 11 since then, the number of diagnosed patients has almost doubled 2 with 100 patients identified worldwide. Apart from a cohort of 11 patients from Saudi Arabia, 3 this is the first case of CBAS1 from Arab countries. Although 3β-HSD deficiency is the most common among bile acid synthesis defects, the number of diagnosed patients remains scarce in view of the variable and non-specific clinical presentations, 12 such as chronic diarrhea in infancy. 13

In our patient the predominant clinical manifestations were related to isolated splenomegaly and hypersplenism which delayed the final diagnosis. The association of cholestasis with normal GGT could be mostly suggestive of a bile acid synthesis disorder or progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 1 or 2. 14 This patient displayed mild biochemical cholestasis without clinical symptoms of fat-soluble vitamins malabsorption. None of the other suggestive signs like jaundice, hepatomegaly, pruritus, or failure to thrive was present. Furthermore, renal lesions, significantly prevalent in HSD3B deficiency, 2 were absent.

To our knowledge, only one other patient reported by Zhao et al 2 had a history of isolated splenomegaly upon presentation, but it was associated with recurrent cholestasis. The wide differential diagnosis of splenomegaly encompassing different etiologies from infectious, immunologic, hematologic, lymphoproliferative to inherited metabolic diseases warranted a comprehensive, but expensive, work-up that was non-revealing.

Ultimately, genetic testing by exome sequencing followed by urine bile acids mass spectrometry confirmed the diagnosis. The homozygous pathogenic variant in the HSD3B7 gene: NM_025193.3: c.551del, p.(Leu184Argfs*2), identified in our patient, was not previously reported in the literature. To date, there is no clear genotype-phenotype correlation in congenital bile acid synthesis disorder type 1, 2 therefore the identification of specific bi-allelic disease-causing variant in the HSD3B7 gene confirms the diagnosis but cannot predict the severity and the outcome of this disease.

Early cholic acid therapy was shown to drastically reverse liver fibrosis and prevent the need for liver transplantation. 15 Our patient was initially treated with the lowest recommended dose (5 mg/kg/day) to alleviate the financial burden on the family; however, in view of the increase of urinary abnormal bile acid metabolites at 6 months of follow-up, higher doses were prescribed (15 mg/kg/day) although no worsening symptoms were noted.

This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of CBAS1. Urine bile acid mass spectrometry being not readily available in most resource-constrained countries as well as the cost of genetic testing may delay the diagnosis; on the other hand, the lack of financial coverage for cholic acid therapy can hinder its prescription and long-term compliance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in populations with high consanguinity rates, the autosomal recessive CBAS1 is expected to occur frequently; however, many patients may die undiagnosed in view of the wide clinical heterogeneity and non-specific presentations. The use of next-generation sequencing as a first-tier testing may identify and confirm such treatable disorders, shortcutting the long list of investigations and the associated incurred expenses. Nevertheless, an increased awareness of CBAS1 among pediatricians is crucial to allow an early diagnosis and treatment, thus improving the patients’ outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient’s parents for permission to share their child’s medical information to be used for educational purposes and publication.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Pascale E. Karam  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0164-4935

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0164-4935

Ethical Considerations: The institutional review board of the American University of Beirut-Lebanon waived the requirement for approval for this case report.

Consent for Publication: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this case report and accompanying figures.

Author Contributions: Nadine Yazbeck: Conceptualization; Methodology; Data curation; Writing—original draft. Rima Hanna-Wakim: Conceptualization; Methodology; Data curation; Writing—original draft. Dolly Noun: Data curation. Pascale E. Karam: Conceptualization; Methodology; Data curation; Supervision; Writing—original draft.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Clayton PT, Leonard JV, Lawson AM, et al. Familial giant cell hepatitis associated with synthesis of 3-beta,7-alpha-dihydroxy- and 3-beta,7-alpha,12-alpha-trihydroxy-5-cholenoic acids. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1031-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhao J, Setchell KDR, Gong Y, et al. Genetic spectrum and clinical characteristics of 3β-hydroxy-Δ5-C27-steroid oxidoreductase (HSD3B7) deficiency in China. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Al-Hussaini AA, Setchell KDR, AlSaleem B, et al. Bile acid synthesis disorders in Arabs: a 10-year screening study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(6):613-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jahnel J, Zöhrer E, Fischler B, et al. Attempt to determine the prevalence of two inborn errors of primary bile acid synthesis: results of a European survey. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(6):864-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heubi JE, Setchell KDR, Bove KE. Inborn errors of bile acid metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2018;22(4):671-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clayton PT. Disorders of bile acid synthesis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(3):593-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nittono H, Suzuki M, Suzuki H, et al. Navigating cholestasis: identifying inborn errors of bile acid metabolism for precision diagnosis. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1385970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Subramaniam P, Clayton PT, Portmann BC, Mieli-Vergani G, Hadzić N. Variable clinical spectrum of the most common inborn error of bile acid metabolism–3beta-hydroxy-Delta 5-C27-steroid dehydrogenase deficiency. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50(1):61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Setchell KD, Heubi JE. Defects in bile acid biosynthesis–diagnosis and treatment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S17-S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang W, Jha P, Wolfe B, et al. Tandem mass spectrometric determination of atypical 3β-hydroxy-Δ5-bile acids in patients with 3β-hydroxy-Δ5-C27-steroid oxidoreductase deficiency: application to diagnosis and monitoring of bile acid therapeutic response. Clin Chem. 2015;61(7):955-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bossi G, Giordano G, Rispoli GA, et al. Atypical clinical presentation and successful treatment with oral cholic acid of a child with defective bile acid synthesis due to a novel mutation in the HSD3B7 gene. Pediatr Rep. 2017;9(3):7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Y, Yang CF, Wang WZ, Cheng YK, Sheng CQ, Li YM. Prognosis and clinical characteristics of patients with 3β-hydroxy-Δ5-C27-steroid dehydrogenase deficiency diagnosed in childhood: a systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(7):e28834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Powell GK, Jones LA, Richardson J. A new syndrome of bile acid deficiency-a possible synthetic defect. J Pediatr. 1973;83(5):758-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mandato C, Zollo G, Vajro P. Cholestatic jaundice in infancy: struggling with many old and new phenotypes. Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gonzales E, Matarazzo L, Franchi-Abella S, et al. Cholic acid for primary bile acid synthesis defects: a life-saving therapy allowing a favorable outcome in adulthood. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]