Abstract

Digital mental health (DMH) tools are a promising solution to the growing need for mental health care among teens because of their scalability and accessibility. Yet the key stakeholders—payors (who reimburse), caregivers (who facilitate adoption and access), and teens aged 13‐17 (the primary users of these tools)—often have conflicting priorities. These misaligned priorities can limit investment in tools that align with user needs and promote long-term engagement, ultimately hindering the effective deployment of DMH tools for teens. This viewpoint paper outlines payor, caregiver, and teen priorities for DMH tools and proposes novel strategies to align these priorities. We argue that this alignment is critical for driving meaningful improvements in teen well-being.

Introduction

The use of digital mental health (DMH) platforms has grown significantly, with increasing numbers of teens using these tools for support. Specifically, health-related app usage among those aged 14 to 22 was nearly 70% in 2020, showing an increase from 2018, particularly in apps focused on mental health issues such as stress and depression [1]. Digital tools such as apps, teletherapy, and artificial intelligence–driven platforms are transforming the way teens access mental health care [2]. These tools offer scalable and accessible ways to address a variety of mental health needs [3], making them an attractive solution for a range of stakeholders: for payors, they offer cost-efficiency; for caregivers, increased access and support for their child; and for teens, convenient, on-demand help.

A payor is an organization (eg, an insurance company) that covers health care costs, including mental health care such as therapy and counseling. In this paper, we use the term “caregivers” broadly to include primary caregivers and legal guardians who play a central role in supporting teens’ adoption and use of DMH tools. Teens in this paper are individuals aged 13 to 17, similar to the age range covered under pediatric mental health benefits by both public and private US insurance programs [4-6].

Payor, caregiver, and teen priorities in DMH are not aligned. Payors prioritize cost-effectiveness, scalability, and regulatory compliance, relying on standardized clinical outcomes to demonstrate return on investment (ROI) [7]. Caregivers and teens value safety, privacy, expert validation, and meaningful engagement, with teens particularly emphasizing autonomy, connectedness, and immediate support over traditional clinical measures [3-5]. Understanding and addressing competing priorities is essential to designing and implementing scalable DMH tools for teens and their families that can be integrated into a complex mental health care setting.

In this paper, we argue that greater attention must be paid to what users—teens and caregivers—actually want and need. By highlighting the perspectives and priorities of teens and caregivers, we suggest strategies to align these with payors’ objectives, encouraging payors to consider these needs when making decisions about which DMH solutions to cover and reimburse.

Payors’ Priorities in Digital Mental Health

Payors are crucial stakeholders because they determine which mental health programs (eg, therapy practices, and DMH tools) are accessible to their policyholders based on financial viability. In the absence of reimbursement from payors, providers (eg, clinicians, clinics, or organizations that deliver mental health services) struggle to offer programs because users cannot afford them. Payors prioritize scalability and regulatory compliance, with interventions that meet privacy and security standards (eg, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–HIPAA) more likely to gain approval and be integrated into broader health care plans [8]. Payors’ primary concern in DMH is ensuring that interventions are both cost-effective (delivering optimal outcomes relative to the cost) and yield measurable outcomes that demonstrate ROI, in which the financial benefits, such as reduced long-term costs, outweigh the initial investment [7]. With the rising cost of health care, payors are increasingly prioritizing solutions that improve patient outcomes and also reduce the overall cost of care such as preventive measures and early interventions that help avoid expensive treatments such as emergency room visits and hospitalizations [9].

In order to demonstrate cost-effectiveness and ROI, payors rigidly prioritize data-driven evidence tied to clinical symptoms such as depression and anxiety, neglecting to consider critical mental health outcomes that matter the most to users, such as stress, sleep, daily functioning, burnout, and quality of life [10]. Improving these broader outcomes has system-wide benefits, such as increased engagement in education and future employment, which further contribute to long-term economic gains [11]. Compounding this issue is the reliance on widely used standard measures for depression and anxiety (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] and General Anxiety Disorder [GAD-7]) and flawed cutoff scores that fail to capture the complexities and nuances of mental health challenges faced by teens in today’s society [12,13,14]. Furthermore, payors exclude teens from coverage who do not meet full diagnostic criteria or those who experience subthreshold symptoms and could benefit from DMH treatment [15,16]. Payors’ narrow view of what constitutes a worthwhile DMH tool restricts investment in innovative solutions that may better align with the preferences of teens and their caregivers.

Notably, sustained engagement with and adherence to DMH tools is low for teens [3]. This is influenced by several factors—for example, teens often use these tools during a mental health challenge or crisis [17]; yet, the tools typically target clinical outcomes (eg, depression and anxiety) that may not align with their immediate concerns. To improve engagement, digital tools need to target the outcomes that teens and caregivers care about most, rather than focusing solely on traditional symptom measures [18]. To truly advance mental health care, payors must expand their scope to include diverse outcomes and engaging, user-centered solutions capable of achieving meaningful improvements at scale.

Caregivers’ Priorities in Digital Mental Health

Caregivers play an important role in the way teens adopt DMH tools. They prioritize safety, expert validation, and effectiveness [4,5]. Caregivers also value DMH tools that foster positive communication and strengthen the caregiver-teen relationship. Yet, caregivers are challenged with balancing involvement in their teen’s privacy and independence as some teens welcome caregiver involvement while others prefer confidentiality [5,19]. Some research has shown that caregiver involvement in their teen’s DMH treatment actually boosts effectiveness [3]; therefore, it is important to ensure caregiver alignment and participation in the DMH interventions. Concerns about program effectiveness, privacy, and potential technology overuse further complicate caregivers’ support for these tools [20]. Many research-based DMH tools have demonstrated effectiveness in randomized controlled trials [3]. These tools were developed under the oversight of an ethics board and were designed to meet privacy standards such as HIPAA. In contrast, most commercially available DMH interventions for teens have not been rigorously evaluated and are not bound by the same privacy regulations as those in research trials [21]. As such, payors should offer and reimburse for DMH tools that provide evidence-based assurances for caregivers, meet industry privacy standards, and include features that facilitate meaningful caregiver-teen interaction [22,23].

Teens’ Priorities in Digital Mental Health

Teens engage with DMH tools that benefit them in the moment and are tailored to their unique needs and preferences, making it essential to align their priorities with those of payors and caregivers [24]. Differences in age, cultural background, gender identity, and mental health history can significantly influence how teens understand mental health, what types of support they consider acceptable or trustworthy, and how they engage with digital interventions [25,26]. Acknowledging this diversity helps ensure that DMH tools reflect teens’ varying needs, rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all approach.

DMH tools that feel relatable and foster a sense of connectedness are especially important [3,9,10]. This includes connections with peers who share lived experiences and with supportive professionals [20]. For example, teens using a DMH platform such as Kooth reported reduced psychological distress and loneliness [27]. These teens reported they learned from their peers’ suggestions and experiences and found a sense of purpose by supporting others. Such teen interactions create benefits such as emotional support and peer-driven learning that traditional clinical outcome measures fail to capture. In addition to connectedness, teens also seek DMH tools that provide immediate emotional relief and practical strategies that help them cope [20]. Privacy and anonymity are also important for teen engagement with DMH tools; however, fears of being judged or sharing information can discourage their use [20]. DMH platforms that are confidential and anonymous help to foster the sense of safety that teens need to open up about sensitive topics. Moreover, many teens value the control that DMH apps offer28 [29]30. Being able to take active steps toward addressing their mental health challenges on their own fosters a sense of agency and empowerment [31]. This sense of control, combined with personalized and immediate support, reflects the outcomes that teens value the most—outcomes that go beyond traditional metrics like symptom reduction and instead emphasize personal growth, emotional connection, and resilience. For payors, recognizing these broader, user-centered outcomes is essential to supporting effective DMH tools. A narrow focus on clinical metrics, such as reductions in depression or anxiety, overlooks the aspects of DMH tools that drive engagement and create meaningful impact for teens. By expanding their perspective to include outcomes that prioritize personalization, privacy, and empowerment, payors can better align their goals with teens’ actual needs, ensuring greater adoption and sustained success of DMH interventions.

Bridging the Gap: Strategies for Alignment

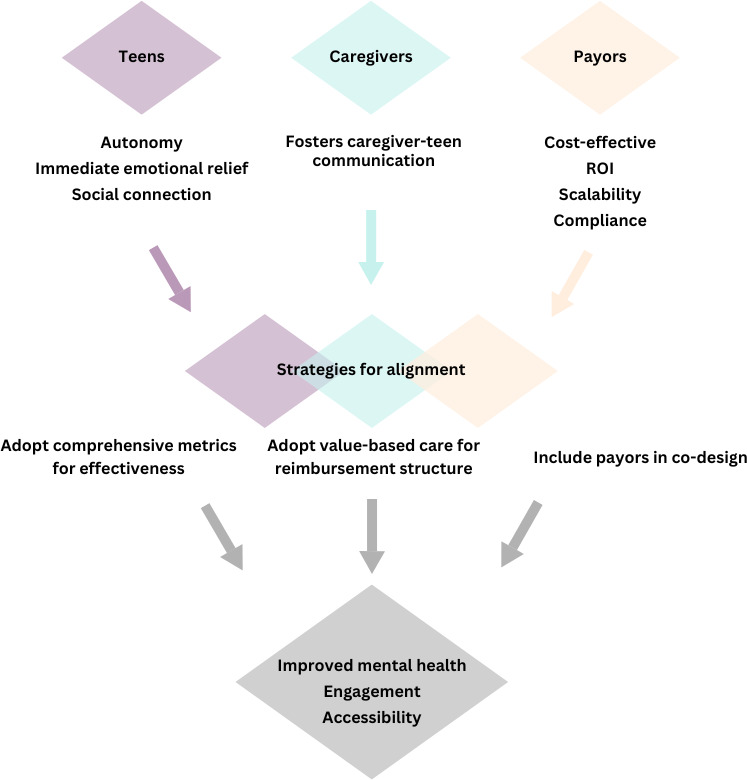

We suggest several novel but realistic ideas for aligning teen and caregiver priorities with payor priorities (Figure 1). First, we encourage researchers to involve payors in the co-design process of DMH tools. Teen and caregiver perspectives are used to inform product design and they are often included in usability testing, but payor perspectives and feedback are frequently overlooked [32]. Involving payors in product design and gaining their perspective may be an invaluable opportunity to tangibly incorporate their priorities in DMH tools. This information can also serve as a way for researchers and product designers to build relationships with payor stakeholders. If payors were involved in the design of DMH tools, they might better understand how meeting policyholder (ie, teen and caregiver) needs can ultimately meet their own needs, including reducing long-term costs, enhancing satisfaction, and improving member retention.

Figure 1. Stakeholder priorities in Digital Mental Health platforms and strategies for alignment. ROI: return on investment.

Another strategy to align competing priorities of teens, caregivers, and payors is to adopt more comprehensive metrics to evaluate the effectiveness and viability of DMH tools. These measures should include traditional symptom assessments (eg, PHQ-9, GAD-7), as well as short, empirically validated user-centric measures such as daily functioning and quality of life [33]. The integration of nonclinical outcomes into reimbursement models should be approached thoughtfully, with careful attention to regulatory guidance and ethical standards, particularly ensuring that such measures are scientifically validated, transparently reported, and equitably applied across populations. Implementing a wider range of metrics requires standardized protocols and pathways for acceptance within reimbursement frameworks, including greater use of existing, validated measures and demonstrating their relevance to outcomes payors currently recognize. Using a multifaceted approach will satisfy the current needs of the payors while beginning to develop an evidence base for outcomes that matter most to teens and caregivers. Over time, this approach could reshape how payors evaluate mental health interventions, shifting focus toward holistic outcomes that align with the real-life priorities of users.

Finally, in our existing health care ecosystem, payors ultimately need evidence that DMH tools are cost-effective and demonstrate a reasonable ROI. One way to bring stakeholders into alignment in this area is to adopt a reimbursement structure for DMH tools that is akin to value-based care. Value-based care is a model that rewards providers for improving outcomes rather than providing services, by, for example, putting a premium on preventive medicine [34]. Value-based care has already been adopted by many payors in traditional healthcare settings. We suggest adopting this model for DMH tools by, for example, encouraging payors to consider tools that impact outcomes tied to early intervention rather than symptom reduction. These might include outcomes that are important for teens and caregivers, such as missed school days, academic performance, and social functioning, as well as outcomes traditionally prioritized by payors, such as emergency department visits and costly prescriptions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper aimed to outline the priorities of three key stakeholders in the development and delivery of DMH tools for teens: payors, caregivers, and teens. Each of these stakeholder groups has unique priorities that often contradict each other, slowing the development of safe, engaging, accessible, and effective DMH tools for teens. Ultimately, we argued that the needs of caregivers and teens should be met, and that payors should adapt their priorities to align more with the needs of their policyholders. We highlighted feasible ways in which payor needs can more closely align with teens and caregivers, such as including payors in the co-design process, considering broader metrics in determining effectiveness, and adopting a value-based care lens for evaluating the viability of DMH tools for teens. A successful future for DMH tools depends on a collaborative, adaptive approach that prioritizes the unique needs of teens and caregivers while aligning with payor objectives. This synergy can foster the development of solutions that are effective and widely adopted, delivering benefits that resonate with teens and support their long-term well-being.

Abbreviations

- DMH

digital mental health

- GAD

General Anxiety Disorder

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- PHQ

Patient Health Questionnaire

- ROI

return on investment

Footnotes

Data Availability: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during this study

Authors’ Contributions: Conceptualization: JH; Writing – Original Draft: JY, JH, LS, LB; Writing – Review & Editing: JY, JH, LS, LB.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors are employees of Fit Minded, Inc. or Kooth Digital Health. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of these organizations.

References

- 1.Rideout V, Fox S, Peebles A, Robb MB. Common Sense Media; 2021. Coping with COVID‑19: how young people use digital media to manage their mental health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovanelli A, Ozer EM, Dahl RE. Leveraging technology to improve health in adolescence: a developmental science perspective. J Adolesc Health. 2020 Aug;67(2S):S7–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.020. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehtimaki S, Martic J, Wahl B, Foster KT, Schwalbe N. Evidence on digital mental health interventions for adolescents and young people: systematic overview. JMIR Ment Health. 2021 Apr 29;8(4):e25847. doi: 10.2196/25847. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Children and youth. Medicaid. [10-06-2025]. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/behavioral-health-services/children-and-youth URL. Accessed.

- 5.Mental health. InsureKidsNow.gov. [10-06-2025]. https://www.insurekidsnow.gov/initiatives/mental-health URL. Accessed.

- 6.Paying for care. Mental Health America. [10-06-2025]. https://mhanational.org/resources/paying-for-care/ URL. Accessed.

- 7.Buntrock C. Cost-effectiveness of digital interventions for mental health: current evidence, common misconceptions, and future directions. Front Digit Health. 2024;6:1486728. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2024.1486728. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyles CR, Adler-Milstein J, Thao C, Lisker S, Nouri S, Sarkar U. Alignment of key stakeholders’ priorities for patient-facing tools in digital health: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Aug 26;23(8):e24890. doi: 10.2196/24890. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chahal BPS, Sharma U, Bansal B. Driving Global Health and Sustainable Development Goals With Smart Technology. IGI Global Scientific Publishing; 2025. Innovative financing models and future directions in healthcare: evaluating the impact of financial strategies on digital health outcomes and innovation; pp. 267–302. doi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathews SC, McShea MJ, Hanley CL, Ravitz A, Labrique AB, Cohen AB. Digital health: a path to validation. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2(1):38. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0111-3. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veldman K, Reijneveld SA, Ortiz JA, Verhulst FC, Bültmann U. Mental health trajectories from childhood to young adulthood affect the educational and employment status of young adults: results from the TRAILS study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015 Jun;69(6):588–593. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204421. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue T, Tanaka T, Nakagawa S, et al. Utility and limitations of PHQ-9 in a clinic specializing in psychiatric care. BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Jul 3;12(1):73. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-73. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nandakumar AL, Vande Voort JL, Nakonezny PA, et al. Psychometric properties of the patient health questionnaire-9 modified for major depressive disorder in adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019 Feb;29(1):34–40. doi: 10.1089/cap.2018.0112. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiirikainen K, Haravuori H, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M. Psychometric properties of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Feb;272:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.004. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noyes BK, Munoz DP, Khalid-Khan S, Brietzke E, Booij L. Is subthreshold depression in adolescence clinically relevant? J Affect Disord. 2022 Jul 15;309:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.067. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peake E, Miller I, Flannery J, Chen L, Lake J, Padmanabhan A. Preliminary efficacy of a digital intervention for adolescent depression: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2024 Feb 7;26(1):e48467. doi: 10.2196/48467. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odgers CL, Jensen MR. Annual research review: adolescent mental health in the digital age: facts, fears, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;61(3):336–348. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13190. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bevan Jones R, Stallard P, Agha SS, et al. Practitioner review: co-design of digital mental health technologies with children and young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020 Aug;61(8):928–940. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13258. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Dea B, Leach C, Achilles M, King C, Subotic-Kerry M, O’Moore K. Parental attitudes towards an online, school-based, mental health service: implications for service design and delivery. Adv Ment Health. 2019 Jul 3;17(2):146–160. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2018.1514269. doi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho TQA, Le LKD, Engel L, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with web-based mental health interventions in young people: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2025 Jan;34(1):83–100. doi: 10.1007/s00787-024-02386-x. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schueller SM, Torous J. Scaling evidence-based treatments through digital mental health. Am Psychol. 2020 Nov;75(8):1093–1104. doi: 10.1037/amp0000654. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peyton D, Wadley G, Hackworth N, Hiscock H. Why parents do not use digital health interventions for their child’s mental health? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2024 Jan 25;310:1076–1080. doi: 10.3233/SHTI231130. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gee B, Clarke T, Garner J, et al. Understanding stakeholder views of the use of digital therapeutic interventions within children and young people’s mental health services. Front Psychiatry. 2025;16:1505345. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1505345. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludlow K, Russell JK, Ryan B, et al. Co-designing a digital mental health platform, “Momentum”, with young people aged 7-17: a qualitative study. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231216410. doi: 10.1177/20552076231216410. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manago AM, McKenzie J. In: Handbook of Adolescent Digital Media Use and Mental Health. Telzer EH, Nesi J, Prinstein MJ, editors. Cambridge University Press; 2022. Culture and digital media in adolescent development; pp. 162–187. doi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguirre Velasco A, Cruz ISS, Billings J, Jimenez M, Rowe S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Dec;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0. doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens M, Cartagena Farías J, Mindel C, D’Amico F, Evans-Lacko S. Pilot evaluation to assess the effectiveness of youth peer community support via the Kooth online mental wellbeing website. BMC Public Health. 2022 Oct 12;22(1):1903. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14223-4. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell BT, Fox L, Salhi L, Fitton D. Exploring adolescents’ and stakeholders’ perceptions of online and school‐based mental health provision. JCPP Advances. 2024 Dec;4(4):e12288. doi: 10.1002/jcv2.12288. doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribanszki R, Saez Fonseca JA, Barnby JM, et al. Preferences for digital smartphone mental health apps among adolescents: qualitative interview study. JMIR Form Res. 2021 Aug 27;5(8):e14004. doi: 10.2196/14004. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pretorius C, Chambers D, Coyle D. Young people’s online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: systematic narrative review. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Nov 19;21(11):e13873. doi: 10.2196/13873. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wies B, Landers C, Ienca M. Digital mental health for young people: a scoping review of ethical promises and challenges. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:697072. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2021.697072. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mimoso I, Figueiredo T, Midão L, et al. Co-Creation in the development of digital therapeutics: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024 Nov 28;21(12):1589. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21121589. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKnight PE, Kashdan TB. The importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009 Apr;29(3):243–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.005. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NEJM Catalyst What is value-based healthcare. Catal Carryover. 2017 Jan;3:1. doi: 10.1056/CAT.17.0558. doi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]