Abstract

Background:

Some validated scales for assessing upper gastrointestinal (UGI) cleanliness have been developed, though none have been widely implemented.

Objectives:

To evaluate the association between the presence of clinically significant lesions (CSLs) in the UGI tract and mucosal cleanliness using the Barcelona Scale. The secondary objective includes assessing the safety of water lavage during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

Design:

Multicenter prospective study conducted in 14 hospitals in Spain.

Methods:

From January 2022 to December 2023, patients undergoing EGD were included. After cleansing, the esophagus, fundus, corpus, antrum, and duodenum were scored from 0 (unassessable due to content) to 2 (fully visualized mucosa), with a maximum score of 10.

Results:

A total of 641 patients were included, and 3205 segments were assessed: 2594 scored “2,” 604 “1,” and 7 “0.” In 272 patients, 327 CSLs were identified: 93 (14.5%) in the esophagus, 223 (34.8%) in the stomach, and 11 (1.7%) in the duodenum. Only five cases of neoplasia were found, all in segments scored “2” (global score ⩾ 9). The CSL detection rates were 0%, 5.3%, and 11.4% for scores 0, 1, and 2, respectively (p < 0.001), with a significantly higher rate for score “2” compared to “1” (OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.57–3.34). Besides the degree of cleanliness, several factors were independently associated with CSL detection, including the use of a high-definition endoscope (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.14–3.23), male sex (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.1–2.17), and age ⩾58 years (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.09–2.17).

Conclusion:

The Barcelona scale may be a valid instrument for assessing the quality of cleanliness during EGD in real clinical practice, as it improves the detection of CSL in the UGI.

Keywords: cleanliness, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, quality, upper gastrointestinal tract, visualization

Plain language summary

The Barcelona scale is a valid and safe instrument for assessing the quality of cleanliness during EGD in real clinical practice

This study prospectively assessed the validity of the Barcelona Cleanliness scale as a tool for evaluating cleanliness during real-time EGD and demonstrated its significant association with the detection of CSL. This clear and simple scale is a 3-point scoring system (0 to 2) that assesses the entire upper GI tract (esophagus, stomach and duodenum) and divides the stomach into three segments: fundus, body and antrum. The Barcelona scale has demonstrated to be a valid and reproducible scale with minimal training among endoscopists with different levels of expertise. We believe these findings might help endoscopists to assess the mucosal cleanliness quality during EGD, using the Barcelona scale.

Introduction

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the gold standard for diagnosing upper gastrointestinal cancer and precancerous lesions. In addition to factors as sufficient examination time and appropriate photo documentation, proper visualization of the mucosa is crucial for achieving accurate diagnosis and identifying clinically significant lesions (CSLs).

Despite advancements in improving EGD quality and the adoption of new endoscopic technologies, a significant number of gastric cancer cases remain undetected during EGD. Reports from Western countries indicate that between 4.6% and 14.4% of gastric cancers were preceded by a negative EGD within the previous 3 years.1–3 This issue can be partly explained by the fact that precancerous gastric lesions and early gastric cancer are subtle and nearly imperceptible. Therefore, a meticulous and detailed examination is essential, and mucosal cleanliness must be optimal.

There has been increasing interest in improving the quality and standardizing the protocols of EGD. 4 However, no widely accepted upper gastrointestinal (UGI) cleanliness scale has been sufficiently validated, nor has one been uniformly adopted and used in routine endoscopy practice. On the one hand, the most widely used and validated scale during colonoscopy is the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), which assesses mucosal visibility after all necessary cleansing maneuvers and shows a significant association with clinical outcomes, such as polyp detection rates. 5 On the other hand, a recently developed scale for assessing EGD cleanliness, similar to the BBPS, evaluates three segments (esophagus, stomach, and duodenum). This scale, known as the PEACE system, has demonstrated that adequate cleanliness is associated with a higher detection rate of CSL when used by expert endoscopists. 6

The use of water lavage during gastroscopy is, therefore, essential and should be part of standard practice. However, no studies have specifically assessed the safety of instilling large volumes of water during the gastroscopy procedure when sedation is employed. In Spain, we developed a novel mucosal cleanliness scoring system designed for use during EGD following cleansing maneuvers. This system, known as the Barcelona scale, evaluates all segments of the UGI tract and divides the stomach into three different segments, assigning a score ranging from 0 to 2 points for each of segment. 7 During its development, the Barcelona cleanliness scale was evaluated by multiple endoscopists in both tertiary and community hospitals, demonstrating good interobserver and intraobserver agreement, with mean kappa values 0.82 and 0.89, respectively.

The current study aimed to assess the clinical impact of the Barcelona cleanliness scale by evaluating the association between the detection of CSL in the UGI tract and the degree of cleanliness. Secondary objectives included evaluating the safety of water lavage during EGD.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This is a prospective observational multicenter study conducted across 14 Spanish hospitals (eight tertiary and six community) involving 15 endoscopists with varying levels of experience: two endoscopists with less than 5 years of experience, two with 5 to 10 years of experience, and 11 with more than 10 years of experience. These endoscopists had previously participated in the evaluation of the scale’s applicability after completing a brief training session. 7 This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (HCB/2020/1436) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The reporting of this study conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies. 8

Consecutively, patients aged over 18 years who underwent a diagnostic upper GI endoscopy for any reason from January 2022 to December 2023 were included. Exclusion criteria included patients under surveillance for previously known UGI pathology, suspicion of GI obstruction, history of prior UGI surgery, therapeutic EGD, and urgent EGD.

Endoscopic procedure

All patients underwent an EGD following a standard protocol, which included fasting for at least 2 h for liquids and 6 h for solids, with sedation administered according to the standard practice of each center. The following endoscopes were used: GIF-1100, GIF-HQ190, and GIF-H180J, with the EVIS EXERA III and X1 systems (Olympus Europe, Hamburg, Germany); Fujifilm EG-600WR, EG-600ZW with VP 7000 system (Fujifilm Europe, Düsseldorf, Germany); Sonoscape EG-550 with the HD-550 4 LED system and Pentax EG29-90, EG27-90 with EPK-i7000 system. The duration of the EGD was measured using a stopwatch. Chromoendoscopy was used at the discretion of the endoscopist, as well as biopsies following the Sydney protocol.

Assessment of validity of the Barcelona cleanliness scale

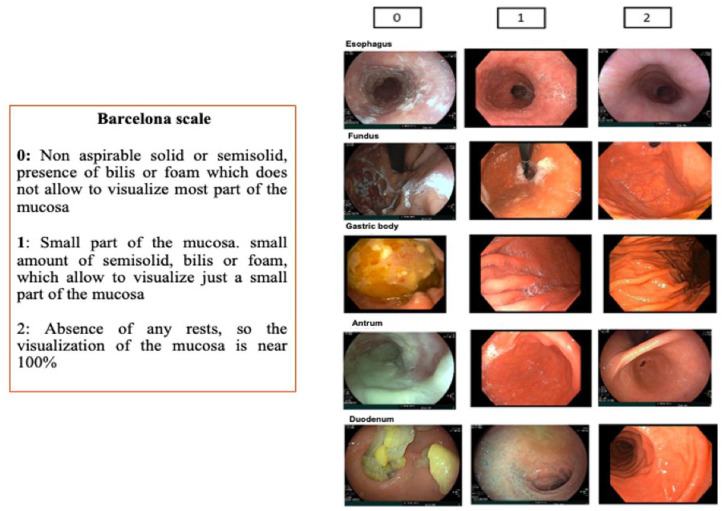

After all necessary cleansing maneuvers, five segments were evaluated independently (esophagus, fundus including the cardia assessment, body, antrum including incisura angularis, and duodenum) and scored from 0 to 2 points for each segment. The scoring criteria were as follows: 0 = non-aspirable solid or semisolid matter, the presence of bile or foam that prevents visualization of most of the mucosa; 1 = small amount of semisolid matter, bile, or foam, allowing visualization of most of the mucosa; 2 = absence of any residual material, allowing nearly 100% visualization of the mucosa (Figure 1). 7 The partial scores were summed to obtain a global score, ranging from a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 10.

Figure 1.

Description of the Barcelona cleanliness scale.

Source: Reproduced with permission. 7

The substances used for cleansing were either water alone or a combination of water and simethicone, according to routine practice. Irrigation was performed using a foot pump and irrigator. No premedication with mucolytic drinks or N-acetylcysteine was used. Pictures from each segment were taken.

Clinically significant lesions

The primary outcome was the detection of CSLs, defined as follows:

Esophagus: esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal ulcers, malignant neoplasms.

Stomach: ulcers, gastric mucosal atrophy, gastric intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia, polyps (excluding fundic gland polyps), subepithelial lesions, and gastric neoplasms (adenocarcinoma, lymphoma).

Duodenum: ulcers, neoplasms, duodenal polyps.

Lesions were characterized using virtual or conventional chromoendoscopy, with biopsies were taken and pictures captured. Polyps were classified according to the Paris classification.

Additional data collection

The duration of lavage and inspection per segment, as well as the total procedure time, was recorded.

Adverse events (AEs) were documented during the procedure and immediately afterward while the patient was recovering from sedation. Sedation-related AEs were defined according to the recommendations of Mason et al. 9 Severe AEs were defined as follows: oxygen desaturation with SpO2 < 75% at any time or SpO2 < 90% for more than 60 s, prolonged apnea (⩾60 s), cardiovascular collapse, cardiac arrest/absent pulse, life-threatening arrhythmias, or bleeding requiring blood transfusion or hospitalization.

All the variables were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture10,11 electronic data capture tools, hosted at the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology (Asociación Española de Gastroenterología – AEG).

Sample size calculation

For sample size estimation, we used a conservative approach based on detecting a 10% absolute difference in proportions between groups 1 and 2 (e.g., 10% vs 20%), with a two-sided α of 0.05 and 80% power. Under these conditions, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be approximately 588 participants.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the characteristics of the patients. Continuous variables were presented as median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical significance between groups was analyzed using the Student’s t-test for parametric and Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric variables, and either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the strength of association between CSL detection and significant variables. Candidate variables for inclusion in the model were those achieving a p value ⩽ 0.1 in the univariate analysis. For continuous variables, the median value was used. The results were expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population characteristics

The population characteristics and additional details are summarized in Table 1. A total of 641 patients were included, with a median age of 58 years (IQR 45–69), and 389 (60.7%) were female. The median fasting time was over 8 h. The most common indication was dyspepsia (n = 250, 39%), and sedation was administered to 602 (93.9%) patients. The median duration of gastric lavage was 60 s (IQR 43–120), with a median total cleansing time of 2 min (IQR 1.24–3), and a median total procedure time of 8 min (IQR 6.09–9.66).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the population and endoscopic details.

| Total (n = 641) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Female, n (%) | 389 (60.7%) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 58 (45–69) |

| Frequency of explorations in patients > 50 years old, n (%) | |

| Performed by experts | 162 (61.8%) |

| Performed by non-experts | 260 (68.6%) |

| Indication, n (%) | |

| Dyspepsia | 250 (39%) |

| GERD | 120 (18.7%) |

| Anemia | 77 (12%) |

| Dysphagia | 66 (10.3%) |

| Abdominal pain | 48 (7.5%) |

| Diarrhea | 18 (2.8%) |

| Total fasting hours, n (%) | |

| 3–4 h | 9 (1.4%) |

| 4–6 h | 17 (2.7%) |

| 6–8 h | 84 (13.1%) |

| >8 h | 531 (82.8%) |

| Healthcare facility level, n (%) | |

| Tertiary hospitals | 8 (57.1%) |

| Community hospitals | 6 (42.9%) |

| Endoscopist’s experience, n (%) | |

| Experts | 8 (53.3%) |

| Non-experts | 7 (46.6%) |

| Number of explorations according to the endoscopist’s experience | |

| Performed by non-experts | 379 (59%) |

| Performed by experts | 262 (41%) |

| Endoscopes, n (%) | |

| High-definition endoscopy | 552 (86.1%) |

| Chromoendoscopy | 259 (40%) |

| Electronic chromoendoscopy | 256 (39%) |

| Procedure duration, median (IQR) | |

| Total procedure duration (minutes) | 8 (6.1–9.7) |

| Experts | 7.5 (6.2–9.1) |

| Non-experts | 8 (6.2–10) |

| Total inspection duration (minutes) | 4.5 (3–6) |

| Duration of gastric inspection (minutes) | 2.5 (1.5–3.5) |

| Cleansing duration (minutes) | 2 (1.2–3) |

| Duration of gastric cleansing (seconds) | 60 (43–120) |

| Cleansing liquid, n (%) | |

| Water | 331 (56%) |

| Water + simethicone | 251 (43%) |

| Adverse events, n (%) | |

| Severe adverse events | 0 |

| Allergic reaction | 1 (0.2%) |

| Bleeding | 4 (0.6%) |

| Respiratory depression | 7 (1%) |

Data were presented as numbers and percentages (N (%)).

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Cleansing assessment according to the Barcelona scale

In 641 patients, a total of 3205 segments were assessed: 2594 segments received a score of “2” points, 604 segments received a score of “1” point, and 7 segments (all of them in the stomach) received a score of “0” points. A description of the scores assigned to each segment can be found in Appendix 1 (Supplemental Material). The median global score per patient was 9 points (IQR 8–10).

Endoscopic findings and Barcelona scale scoring

A total of 327 CSLs were identified in 272 patients. Of these, 93 (14.5%) were found in the esophagus, 223 (34.8%) in the stomach, and 11 (1.72%) in the duodenum (Table 2). Only five cases of neoplasia were identified (four in the antrum and one in the fundus). All were located in segments scored as “2” and had a global score of 10. Other CSLs, requiring further endoscopic surveillance due to their preneoplastic nature, were also detected in segments scored as “2” (100% of Barrett’s esophagus and 89.7% of gastric atrophy/intestinal metaplasia).

Table 2.

Types of clinically significant lesions identified in total and by score.

| Type of lesions per segment | n (%) | Scoring per segment affected | Global score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score 0 | Score 1 | Score 2 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Esophageal CSL | 93 (14.5%) | 0 | 8 | 85 | 3 | 9 | 15 | 26 | 40 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 79 (12.3%) | 0 | 7 | 72 | 1 | 9 | 13 | 21 | 35 |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 13 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Ulcer | 1 (0.15%) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastric CSL | 223 (34.8%) | 0 | 24 | 199 | 5 | 10 | 38 | 63 | 107 |

| Gastric atrophy | 154 (24%) | 0 | 16 | 138 | 5 | 8 | 28 | 43 | 70 |

| Polyp | 34 (5.3%) | 0 | 5 | 29 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 20 |

| Ulcer | 13 (2%) | 0 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 11 (3.4%) | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| Subepithelial tumor | 6 (0.94%) | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Neoplasm | 5 (0.78%) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Duodenal CSL | 11 (1.7%) | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| Ulcer | 8 (1.24%) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Subepithelial lesion | 3 (0.47%) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

CSL, clinically significant lesión.

Total lesions per segment in bold.

The detection rate of CSLs was 0%, 5.3%, and 11.4% for scores “0,” “1,” and “2,” respectively (p < 0.001), with a significantly higher detection rate for score “2” compared to score “1” (OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.57–3.34) (Table 3). In the segment analysis, higher scores showed a trend towards increased CSL detection; however, the association was only significant in the antrum, where a score of “2” was more likely to present a CSL compared to a score “1” (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.01–5.70).

Table 3.

CSL identification according to cleanliness scores globally and per segments.

| Group/Location | Score 0 | Score 1 | Score 2 | p-Value 0 vs 1 | p-Value 0 vs 2 | p-Value 1 vs 2 | Global | OR 2 vs 1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All segments | ||||||||

| N | 7 | 604 | 2594 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (5.3%) | 295 (11.4%) | 0.532 | 0.345 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2.29 (1.57–3.34) |

| Experts | ||||||||

| N | 0 | 137 | 1173 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 114 (9.7%) | — | — | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.072–1.124) |

| Non-experts | ||||||||

| N | 7 | 467 | 1421 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (6.6%) | 181 (12.8%) | 0.481 | 0.322 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 1.97 (1.33–2.93) |

| Per segment | ||||||||

| Esophagus | ||||||||

| N | 0 | 56 | 585 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 8 (14%) | 85 (14.5%) | — | — | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.47–2.23) |

| Stomach | ||||||||

| Fundus, N | 3 | 225 | 413 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.8%) | 17 (4.1%) | 0.948 | 0.882 | 0.085 | 0.2 | 2.37 (0.79–7.14) |

| Body, N | 2 | 165 | 474 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 14 (8.5%) | 54 (11.4%) | 0.839 | 0.786 | 0.186 | 0.514 | 1.39 (0.75–2.57) |

| Antrum, N | 2 | 57 | 582 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (10.5%) | 128 (22%) | 0.805 | 0.609 | 0.026 | 0.097 | 2.4 (1.01–5.71) |

| Duodenum | ||||||||

| N | 0 | 101 | 540 | |||||

| CSL, n (%) | 0 | 0 (0) | 11 (2%) | — | — | 0.228 | 0.228 | — |

CI, confidence interval; CSL, clinically significant lesion; OR, odd ratio.

Considering the global score, the number of patients with at least one CSL was 0 for a score “≤5,” 6 (31.5%) for a score of “6,” 16 (34%) for a score of “7,” 45 (42%) for a score of “8,” 76 (45.7%) for a score of “9,” and 129 (43.2%) for a score of “10” (p = 0.49) (Appendix 2, see Supplemental Material). When sub-analyzing the global score only in the stomach, the distribution was as follows: 0 patients for a score of “≤2,” 5 patients (16.1%) for a score of “3,” 13 patients (14.9%) for a score of “4,” 49 patients (27.2%) for a score of “5,” and 106 patients (31.2%) for a score of “6” (p = 0.03) (Figure 2). A correlation analysis showed a significant positive association between the global gastric score and the proportion of patients with at least one CSL in the stomach (ρ = 0.928, p = 0.008; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Global score distribution in the stomach and number of patients with at least one gastric CSL per global score (p = 0.03).

CSL, clinically significant lesion.

Figure 3.

Study flow diagram.

Besides the degree of cleanliness, other factors were independently associated with CSL detection, such as male sex (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.1–2.17), age ⩾ 50 years (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.08–2.16), and the use of high-definition endoscopes and chromoendoscopy (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.1–3.2 and 1.97, 95% CI 1.34–2.89, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with CSL detection rates.

| Variable | CSL detection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSL identified n (%) | No CSL n (%) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |||

| Age ⩾ 58 years (n = 321) |

153 (48%) | 168 (52%) | 1.54 (1.12–2.1) | 0.008 | 1.54 (1.09–2.18) | 0.014 |

| Age < 58 years (n = 320) |

119 (37%) | 201 (63%) | ||||

| Age ⩾ 50 years (n = 219) | 79 (36%) | 140 (64%) | 1.49 (1.07–2.09) | 0.024 | 1.6 (1.08–2.16) | 0.016 |

| Age < 50 years (n = 422) | 193 (45.7%) | 229 (54.3%) | ||||

| Sex, male (n = 252) |

126(50%) | 125 (50%) | 1.70 (1.20–2.30) | 0.002 | 1.54 (1.10–2.17) | 0.015 |

| Sex, female (n = 389) |

146 (37.5%) | 243 (62.5%) | ||||

| High-definition endoscopy (n = 552) |

250 (45.3%) | 302 (54.4%) | 2.64 (1.57–4.43) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.10–3.20) | 0.022 |

| Standard endoscope (n = 88) |

21 (24%) | 67 (76%) | ||||

| Explorations performed by experts (n = 262) | 95 (36.3%) | 167 (64%) | 1.54 (1.12–2.13) | 0.011 | 1.42 (1.01–2.01) | 0.044 |

| Explorations performed by non-experts (n = 379) | 177 (47%) | 202 (53%) | ||||

| Chromoendoscopy performed (n = 259) | 140 (54%) | 119 (46%) | 2.56 (1.78–3.52) | <0.001 | 1.97 (1.34–2.89) | <0.001 |

| Chromoendoscopy not performed (n = 382) | 132 (34.6%) | 250 (65.4%) | ||||

| Simethicone used for lavage (n = 253) | 104 (41%) | 149 (59%) | 0.81 (0.59–1.14) | 0.312 | ||

| Water only lavage (n = 331) |

151 (45.6%) | 180 (54.4%) | ||||

| Anemia (n = 77) |

41 (53%) | 36 (47%) | 1.64 (1.02–2.65) | 0.049 | 1.48 (0.87–2.52) | 0.146 |

| No anemia (n = 564) |

231 (41%) | 333 (59%) | ||||

| Procedure time ⩾ 8 min (n = 346) |

166 (48%) | 180 (52%) | 1.75 (1.25–2.44) | <0.001 | 1.43 (0.96–2.01) | 0.080 |

| Procedure time <8 min (n = 255) |

88 (34.5%) | 167 (65.5%) | ||||

| Total inspection time > 4.5 min (n = 314) | 156 (49.7%) | 158 (50.3%) | 1.80 (1.31–2.47) | <0.001 | 1.15 (0.78–1.70) | 0.480 |

| Total inspection time ⩽ 4.5 min (n = 327) | 116 (35.5%) | 211 (64.5%) | ||||

| Fasting time ⩽ 8 h (n = 110) |

43 (39%) | 67 (61%) | 1.19 (0.78–1.80) | 0.460 | ||

| Fasting time > 8 h (n = 531) |

229 (43%) | 302 (57%) | ||||

| Global Barcelona score = 10 (n = 298) |

129 (43.3%) | 169 (56.7%) | 1.07 (0.78–1.46) | 0.690 | ||

| Global Barcelona score ⩽ 9 (n = 343) |

143 (41.7%) | 200 (58.3%) | ||||

Data were presented as numbers and percentages (N (%)).

CI, confidence interval; CSL, clinically significant lesion; OR, odd ratio.

Adverse events

No patient experienced any serious AEs. Only 12 (1.87%) AEs occurred during the procedure: one allergic reaction, four cases of bleeding, and seven instances of respiratory depression. The duration of the procedure was not associated with AEs (<8 min, 1.7% vs ⩾8 min, 1.2%; p = 0.74), nor was the time spent on cleansing maneuvers (<2 min, 1.5% vs ⩾2 min 1.9%, p = 0.77).

Discussion

This study prospectively assessed the validity of the Barcelona Cleanliness scale as a tool for evaluating cleanliness during real-time EGD and demonstrated its significant association with the detection of CSL. The Barcelona scale was developed in response to the need for an objective method of evaluating cleanliness during EGD. This clear and simple scale is a three-point scoring system (ranging from 0 to 2) that assesses the entire upper GI tract (esophagus, stomach, and duodenum), with the stomach divided into three segments: the fundus, body, and antrum. The Barcelona scale has been demonstrated to be a valid and reproducible tool with minimal training required for endoscopists of varying expertise levels. 7

The quality of an EGD during the procedure is influenced by various factors, with a detailed examination being crucial. Consequently, the cleanliness and visibility of the gastric mucosa are of utmost importance. However, the level of gastric cleanliness is not routinely reported in clinical practice. The scale introduced by Kuo and later modified by Chang et al. 12 is the most widely used in studies evaluating the effect of premedication on gastric cleanliness. Therefore, this scale, as well as the GRACE (Gastroscopy Rate of Cleanliness Evaluation) scale, 13 is applied before the washing process, not afterward. Indeed, the GRACE scale evaluated, in real time, the impact of cleanliness on the actions taken by the endoscopists during the exploration and actions that included the option of performing washings. Recently, two new EGD cleaning scales have been developed to assess post-washing preparation quality: the PEACE (Polprep: Effective Assessment of Cleanliness in Esophagogastroduodenoscopy) 6 and the TUGS (Toronto Upper Gastrointestinal Cleaning Score). 14 These two scales are built like the BBPS, assigning a score from 0 to 3 to each segment. However, while the PEACE scale evaluates the entire GI tract, the TUGS scale excludes the esophagus, based on the assumption that the lesions found there are highly specific and differ from those in the stomach and duodenum. Very recently, the PEACE scale has been validated for detecting lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tract and has demonstrated that adequate cleanliness is associated with a higher detection rate of CSL.

The basic principles of the Barcelona cleanliness scale for the EGD are similar to those used in the development of the BBPS for colonoscopy, which facilitates its implementation. The BBPS is a widely accepted scale used during routine colonoscopies. 15 Total BBPS scores have been associated with clinical outcomes such as polyp detection rates, 5 recommendations for repeated procedures, and colonoscope insertion and withdrawal times.4,16,17 It has also been shown that inadequate preparation for colonoscopy, as assessed by the BBPS, is a risk factor for missing advanced adenomas and cancer. 18 In this study, the Barcelona cleanliness scale demonstrated its utility in clinical practice, as higher scores were associated with an increased risk of CSL detection (OR 2.29 for score “2” vs score “1”). Interestingly, all neoplastic lesions were gastric and detected at a score of 2. Besides, in the segment analysis, the association between higher scores and CSL detection was only significant in the antrum, highlighting the importance of adequate mucosal cleanliness for gastric neoplasia detection even in areas easier to assess, such as the antrum. Since no lesions were detected in segments scored as “0,” a cleaning level could be considered adequate when a minimum score of “1” is achieved. Although a trend toward higher CSL detection was observed in cases with higher global cleanliness scores, it was not statistically significant. This may reflect the variability in lesion types and their localization within the upper GI tract. By contrast, when considering the global score only in the stomach, a significant association was observed between cleanliness and CSL detection, suggesting that mucosal visualization quality in this segment may have a greater impact on CSL identification.

Unlike the BBPS, which assigns scores from 0 to 3, the Barcelona scale uses a 3-point scoring system ranging from 0 to 2. This approach was chosen after observing very poor agreement during preliminary phases when assuming four possible scores per segment, particularly between scores “0” and “1” (data not published). By contrast, by adopting the three-point scoring system, we demonstrated excellent agreement with the consensus score after minimal training, showing that the Barcelona scale is a valid and reproducible measure. The other prospectively validated scoring system for EGD, the PEACE, uses the same four-point scale as the BBPS. However, in practice, it was reduced to a three-point scale, as no segment was assigned a score of “0.” This can be easily explained by the differences in the type of content in the upper digestive tract and the colon, which make it easier to achieve proper cleaning in the stomach. Moreover, the PEACE scale did not find significant differences in CSL detection in segments scored as “2” and “3.” However, they decided to maintain the scoring system used in the BBPS and to explore the differences between scores “2” and “3” in future studies. Another scale, the TUGS, uses the same four-point scoring system as the BBPS for assessing the stomach and duodenum, but excludes the esophagus from the evaluation. 14 To date, this scale has not demonstrated its clinical applicability yet.

In addition to proper cleanliness, the EGD duration appears to be an essential and complementary indicator of high-quality EGD.2,4,6,19–21 However, neither the total duration of the EGD nor the inspection time was an independent factor associated with the detection of CSL in our study. The lack of a positive impact of fasting times longer than 8 h on CSL detection supports the idea that extending fasting beyond this duration may not provide additional benefits. Other factors linked to the detection of CSLs included the use of high-definition endoscopes and chromoendoscopy, age ⩾ 50 years, and male sex. The addition of simethicone to the lavage water did not enhance lesion detection, as demonstrated in other studies. 6

The strength of our study lies in the fact that it was evaluated by a large number of endoscopists with varying levels of expertise, working at both academic and community hospitals. This demonstrates that the Barcelona scale can be easily disseminated to a wide range of practice settings worldwide through simple training. Furthermore, to facilitate the implementation of the scale, we have considered only three possible scores.

Our study has several limitations. First, the primary desired outcome was the impact on the detection of UGI neoplastic lesions. Our country constitutes a low-risk area for GC, with a low prevalence of neoplastic lesions (0.7% in our series), which limits the scale’s validation in high-risk groups. Second, it is likely that the participating endoscopists paid more attention to mucosal cleansing and thorough exploration of the mucosa. Third, chromoendoscopy and Sydney protocol were not systematically performed, and the number of significant findings could have been underestimated. Fourth, the small number of subepithelial lesions included prevents us from concluding this type of lesion. Moreover, we did not evaluate the impact of the scale on the diagnosis of lesions based on morphology and size.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the degree of mucosal cleanliness assessed by the Barcelona scale correlates with the detection of CSLs in the UGI tract. A cleaning level may be considered adequate when a minimum score of “1” is achieved in each segment. The Barcelona scale may serve as a useful tool for evaluating mucosal cleanliness in the UGI tract and could help improve the quality of upper endoscopy in future studies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848251363873 for Prospective validation of the Barcelona scale for the assessment of mucosal cleanliness during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy by Henry Córdova, Irina Luzko, Javier Tejedor-Tejada, Edgar Castillo-Regalado, Eva Barreiro-Alonso, Pedro Delgado-Guillena, Pilar Diez Redondo, Martin Galdin, Ana García-Rodríguez, Luis Hernández, Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez, Agustín Seoane, Javier Jiménez Sánchez, Joaquín Cubiella, Rodrigo Jover, Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús, Cautar El Maimouni, Leticia Moreira, Oswaldo Ortiz, Joan Llach and Gloria Fernández-Esparrach in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-tag-10.1177_17562848251363873 for Prospective validation of the Barcelona scale for the assessment of mucosal cleanliness during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy by Henry Córdova, Irina Luzko, Javier Tejedor-Tejada, Edgar Castillo-Regalado, Eva Barreiro-Alonso, Pedro Delgado-Guillena, Pilar Diez Redondo, Martin Galdin, Ana García-Rodríguez, Luis Hernández, Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez, Agustín Seoane, Javier Jiménez Sánchez, Joaquín Cubiella, Rodrigo Jover, Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús, Cautar El Maimouni, Leticia Moreira, Oswaldo Ortiz, Joan Llach and Gloria Fernández-Esparrach in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-tag-10.1177_17562848251363873 for Prospective validation of the Barcelona scale for the assessment of mucosal cleanliness during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy by Henry Córdova, Irina Luzko, Javier Tejedor-Tejada, Edgar Castillo-Regalado, Eva Barreiro-Alonso, Pedro Delgado-Guillena, Pilar Diez Redondo, Martin Galdin, Ana García-Rodríguez, Luis Hernández, Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez, Agustín Seoane, Javier Jiménez Sánchez, Joaquín Cubiella, Rodrigo Jover, Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús, Cautar El Maimouni, Leticia Moreira, Oswaldo Ortiz, Joan Llach and Gloria Fernández-Esparrach in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Gloria Fernández-Esparrach  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3378-3940

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3378-3940

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Henry Córdova, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínic, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain.

Irina Luzko, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínic, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain.

Javier Tejedor-Tejada, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, Spain.

Edgar Castillo-Regalado, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Spain.

Eva Barreiro-Alonso, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA), Oviedo, Spain.

Pedro Delgado-Guillena, Hospital de Mérida, Mérida, Badajoz, Spain.

Pilar Diez Redondo, Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid, Spain.

Martin Galdin, Consorci Hospitalari de Vic, Vic, Spain.

Ana García-Rodríguez, Servicio de Digestivo, Unidad de Endoscopia, Hospital de Viladecans, Barcelona, Spain.

Luis Hernández, Hospital Santos Reyes, Aranda de Duero, Spain.

Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez, Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid, Spain.

Agustín Seoane, Digestive Department, Endoscopy Unit, Hospital del Mar, Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, Spain.

Javier Jiménez Sánchez, Hospital de Orihuela, Alicante, Spain.

Joaquín Cubiella, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Universitario de Ourense, Research Group in Gastrointestinal Oncology-Ourense, CIBERehd, Ourense, Spain.

Rodrigo Jover, Servicio de Medicina Digestiva, Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria ISABIAL, Universidad Miguel Hernández, Alicante, Spain.

Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús, Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo, Spain.

Cautar El Maimouni, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínic, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain.

Leticia Moreira, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínic, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain.

Oswaldo Ortiz, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínic, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain.

Joan Llach, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínic, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain.

Gloria Fernández-Esparrach, Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínic, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), c. Casanova, 143, Barcelona 08036, Spain.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The ethics committee of the Hospital Clínic of the Barcelona approved this study (HCB/2020/1436). All patient information was kept confidential in this study, and the requirement for informed consent was waived because the data were anonymized.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Henry Córdova: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Irina Luzko: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Javier Tejedor-Tejada: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Edgar Castillo-Regalado: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Eva Barreiro-Alonso: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Pedro Delgado-Guillena: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Pilar Diez Redondo: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Martin Galdin: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Ana García-Rodríguez: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Luis Hernández: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Agustín Seoane: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Javier Jiménez Sánchez: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Joaquín Cubiella: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Rodrigo Jover: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Cautar El Maimouni: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Leticia Moreira: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Oswaldo Ortiz: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Joan Llach: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Gloria Fernández-Esparrach: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Grant from the Esophagus-Stomach-Duodenum Workgroup of the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology in June 2021.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (mgfernan@clinic.cat).

References

- 1. Delgado Guillena PG, Morales Alvarado VJ, Jimeno Ramiro M, et al. Gastric cancer missed at esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a well-defined Spanish population. Dig Liver Dis 2019; 51: 1123–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fernández-Esparrach G, Marín-Gabriel JC, Díez Redondo P, et al. Documento de posicionamiento de la AEG, la SEED y la SEAP sobre calidad de la endoscopia digestiva alta para la detección y vigilancia de las lesiones precursoras de cáncer gástrico. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 44: 448–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Menon S, Trudgill N. How commonly is upper gastrointestinal cancer missed at endoscopy? a meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open 2014; 02: E46–E50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bisschops R, Areia M, Coron E, et al. Performance measures for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. Endoscopy 2016; 48: 843–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, et al. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69: 620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romańczyk M, Ostrowski B, Lesińska M, et al. The prospective validation of a scoring system to assess mucosal cleanliness during EGD. Gastrointest Endosc 2024; 100: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Córdova H, Barreiro-Alonso E, Castillo-Regalado E, et al. Applicability of the Barcelona scale to assess the quality of cleanliness of mucosa at esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024; 47: 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mason KP, Green SM, Piacevoli Q. Adverse event reporting tool to standardize the reporting and tracking of adverse events during procedural sedation: a consensus document from the World SIVA International Sedation Task Force. Br J Anaesth 2012; 108: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang C-C, Chen S-H, Lin C-P, et al. Premedication with pronase or N-acetylcysteine improves visibility during gastroendoscopy: an endoscopist-blinded, prospective, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 444–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Esposito G, Dilaghi E, Costa-Santos C, et al. The Gastroscopy RAte of Cleanliness Evaluation (GRACE) scale: an international reliability and validation study. Endoscopy 2025; 57(4): 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khan R, Gimpaya N, Vargas JI, et al. The toronto upper gastrointestinal cleaning score: a prospective validation study. Endoscopy 2023; 55: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calderwood AH, Jacobson BC. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72: 686–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coe SG, Crook JE, Diehl NN, et al. An endoscopic quality improvement program improves detection of colorectal adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 219–226; quiz 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shaukat A, Rector TS, Church TR, et al. Longer withdrawal time is associated with a reduced incidence of interval cancer after screening colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 952–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pantaleón Sánchez M, Gimeno Garcia A, Bernad Cabredo B, et al. Prevalence of missed lesions in patients with inadequate bowel preparation through a very early repeat colonoscopy.Dig Endosc 2022; 34: 1176–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawamura T, Wada H, Sakiyama N, et al. Examination time as a quality indicator of screening upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for asymptomatic examinees. Dig Endosc 2017; 29: 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park WG, Shaheen NJ, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for EGD. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81: 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teh JL, Tan JR, Lau LJF, et al. Longer examination time improves detection of gastric cancer during diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848251363873 for Prospective validation of the Barcelona scale for the assessment of mucosal cleanliness during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy by Henry Córdova, Irina Luzko, Javier Tejedor-Tejada, Edgar Castillo-Regalado, Eva Barreiro-Alonso, Pedro Delgado-Guillena, Pilar Diez Redondo, Martin Galdin, Ana García-Rodríguez, Luis Hernández, Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez, Agustín Seoane, Javier Jiménez Sánchez, Joaquín Cubiella, Rodrigo Jover, Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús, Cautar El Maimouni, Leticia Moreira, Oswaldo Ortiz, Joan Llach and Gloria Fernández-Esparrach in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-tag-10.1177_17562848251363873 for Prospective validation of the Barcelona scale for the assessment of mucosal cleanliness during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy by Henry Córdova, Irina Luzko, Javier Tejedor-Tejada, Edgar Castillo-Regalado, Eva Barreiro-Alonso, Pedro Delgado-Guillena, Pilar Diez Redondo, Martin Galdin, Ana García-Rodríguez, Luis Hernández, Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez, Agustín Seoane, Javier Jiménez Sánchez, Joaquín Cubiella, Rodrigo Jover, Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús, Cautar El Maimouni, Leticia Moreira, Oswaldo Ortiz, Joan Llach and Gloria Fernández-Esparrach in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-tag-10.1177_17562848251363873 for Prospective validation of the Barcelona scale for the assessment of mucosal cleanliness during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy by Henry Córdova, Irina Luzko, Javier Tejedor-Tejada, Edgar Castillo-Regalado, Eva Barreiro-Alonso, Pedro Delgado-Guillena, Pilar Diez Redondo, Martin Galdin, Ana García-Rodríguez, Luis Hernández, Ma Henar Núñez Rodríguez, Agustín Seoane, Javier Jiménez Sánchez, Joaquín Cubiella, Rodrigo Jover, Antonio Rodríguez-D’Jesús, Cautar El Maimouni, Leticia Moreira, Oswaldo Ortiz, Joan Llach and Gloria Fernández-Esparrach in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology