Abstract

Background

Rotavirus A group (RVA) is a leading cause of viral diarrhea, posing a substantial economic and public health burden. Compared to other enteric viruses, RVA possesses diverse genetic mechanisms, making it more challenging to control and prevent. Moreover, surveillance and evolutionary studies on RVA remain limited in Southern China.

Methods

We collected diarrheal stool samples from sentinel hospitals in Shenzhen and Zhuhai between 2020 and 2023. RVA-positive samples were identified via RT-PCR, followed by RNA extraction, sequencing, and genome assembly, yielding 57 RVA strains, comprising 604 sequences. Genotype trends were analyzed statistically. For phylogenetic analysis, global sequences were curated by CD-HIT, aligned with contributed sequences by MAFFT, and analyzed using IQ-TREE. Recombination and reassortment events were detected via RDP4.

Results

We analyzed the temporal distribution and genetic diversity of 57 newly sequenced strains from Shenzhen and Zhuhai in the context of global sequences. Our findings reveal that the prevalent genotypes of RVA in China have undergone changes over time with the decreasing of G9P[8] and the rising of G8P[8]. Phylogenetic analysis focusing on the VP7 and VP4 genes revealed distinct evolutionary patterns among different genotypes across temporal and geographical dimensions. Additionally, we discovered one reassortment event in the VP7 gene and two recombination events in the NSP1 and NSP5/6 gene.

Conclusions

we observed significant variability and complexity in the evolutionary characteristics of RVA in Shenzhen and Zhuhai. These insights enhance our understanding of global evolution and transmission of RVA and provide guidance for future research and vaccine development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11953-8.

Keywords: Rotavirus, Genotype, Genetic diversity, Reassortment, Recombination

Introduction

Diarrheal disease is one of the top leading causes of infectious disease morbidity, particularly in low-and middle-income countries. Although most diarrheal diseases are generally self-limiting, severe symptoms may occur, including nausea, vomiting, physical weakness, and even more serious illness and death [1]. With improved sanitation and drinking water conditions, gastroenteritis viruses have gradually replaced bacteria and other pathogens as the primary cause of diarrheal illnesses in children and the elderly worldwide [2]. Among these gastroenteritis viruses, rotavirus A group (RVA) is recognized as one of the major pathogens, which causes millions of hospitalizations and deaths each year [3, 4].

Rotavirus A is a non-enveloped double-stranded RNA virus that has a complex architecture of three concentric capsids that surround a genome of 11 RNA segments [5]. The RNA segments 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9 encode six structural viral proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3, VP4, VP6, VP7, respectively), while the segments 5, 7, 8, 10, and 11 encode six non-structural proteins (NSP1, NSP2, NSP3, NSP4 and NSP5/6, respectively) [6]. Rotavirus can be classified into different genotypes based on sequence variations in 11 genomic segments. The full genotype constellation of an RVA strain is denoted by the form Gx-P[x]-Ix-Rx-Cx-Mx-Ax-Nx-Tx-Ex-Hx, corresponding to the encoding viral proteins VP7-VP4-VP6-VP1-VP2-VP3-NSP1-NSP2-NSP3-NSP4-NSP5/6 [7]. Within this genotyping system, primary focus is the G type and P type,, forming the dual nomenclature system for rotaviruses [8].To date, 42 G types and 58 P types of RVAs have been reported in humans and other animals [9]. Generally, most common RVA genotypes include G1, G2, G3, G4, and G9, associated with P[8], P[4], and P[6] genotypes [10]. The global prevalence of rotavirus genotypes fluctuates periodically, with dominant strains declining and new immune-evasive variants emerging approximately every 5–8 years [11, 12]. The most critical characteristic of rotavirus, distinguishing it from other enteric viruses, is its segmented genome. On the one hand, this makes collecting the complete 11-segment genome of rotaviruses more challenging, compared to other enteric viruses, and therefore the complete genomic sequence of all 11 segments is relatively limited. On the other hand, the segmented genome of rotavirus also brings about more complex evolutionary mechanisms, including mutations, recombination, and reassortment [13]. These diverse mechanisms may endow rotavirus with a stronger potential for genetic evolution and immune evasion compared to other enteric viruses.

In China, rotavirus gastroenteritis accounts for approximately 34% hospitalizations and outpatient visits related to diarrheas among the children under 5 [14], imposing a substantial burden on healthcare systems. Furthermore, according to the analysis of epidemiological characteristics of rotavirus cases in children under 5 years old in China from 2005 to 2018 [15], the reported number of rotavirus cases in the southern region (745,526 cases) is nearly 10 times that of the northern region (74,935 cases). Hence, understanding the genetic evolution of RVA in Southern China is crucial. Prominent coastal cities in Southern China include Shenzhen and Zhuhai, both of which are special economic zones with high population density and strong mobility [16, 17]. These factors can greatly facilitate the transmission of rotavirus. Nevertheless, data for the epidemiology of RVA from these regions are significantly limited. Therefore, the surveillance and analysis of rotavirus are crucial for enhancing public health security and disease prevention, particularly in Southern China.

In this research, we investigated the evolutionary characteristics of rotavirus in Shenzhen and Zhuhai from 2020 to 2023. First, we collected clinical RVA samples, established sequencing criteria, sequenced complete genomes, assembled all the genomic segments, and contributed these sequences to online databases. After investigating the genotypes of sequences contributed in this research, we performed a statistical analysis on the RVA genotype distribution at different geographical levels. In the context of global RVA sequences, we systematically analyzed the genetic characteristics of the strains identified in Shenzhen and Zhuhai since 2020. Specifically, we focused on phylogenetic analysis, with a particular focus on the VP4 and VP7 genes, and performed a thorough analysis of the associated evolutionary clades. We also identified and verified the existence of one reassortment event in our contributed strains. Moreover, we investigated the recombination characteristics of RVA and identified two recombination events associated with the Shenzhen strains. This study contributed 604 sequences and helped address the lack of complete genomic data of RVAs in Asia, particularly in Southern China. Additionally, within the global context of rotavirus, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the viral genome, phylogenetic relationships, reassortment, recombination, and other genetic evolutionary features.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Between January 2020 and December 2023, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Shenzhen and Zhuhai received stool samples from acute gastroenteritis (AGE) patients who treated in sentinel hospitals. Each sample, approximately 5–10 mL, was collected in a sterile stool sampling cup. Samples were frozen at − 20 °C for later use. During the sampling process, the dual fluorescent PCR (polymerase chain reaction) nucleic acid detection kit was used to detect the viral nucleic acid of RVA.

Detection of rotavirus

The samples were subjected to etiology detection using a fluorescent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid detection kit. Fresh fecal samples were first prepared into a 2% suspension using phosphate-buffered saline and then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min. Afterward, 200 mL of the supernatant was collected. Nucleic acid detection was performed using reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). The Rotavirus Group A Detection Kit (Juji Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used alongside a real-time PCR platform (Applied Biosystems 7500). The reaction conditions included reverse transcription at 50 °C for 15 min, denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of amplification (denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, annealing and extension at 55 °C for 30 s). Samples with a cycle threshold (CT) value less than 28 and showing exponential amplification on the standard curve were considered positive.

Clustering and sequencing

Nucleotides from samples that tested positive for RVA via generic PCR were used to generate RNA libraries. The U-mRNA Seq Library Prep Kit was employed for this purpose. The size of the library fragments was assessed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the library concentration was quantified using a Qubit fluorometer. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform, which produced 150-bp paired-end reads. Raw FASTQ files were assessed with the FastQC tool v.0.11.9 and filtered using Trimmomatic v.0.39 [18]. The contigs were built with default parameters of the SPAdes program v.3.15.526 [19]. These paired-end reads were then assembled into complete genomic sequences using Unicycler v0.4.7 and Geneious v2023.2.1 software [20, 21]. The assembled sequences were deposited to the NCBI Genbank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).

Phylogenetic analysis of genomic segments

In order to contextualize our phylogenetic studies within a global framework of RVA sequences, we included both contributed sequences and online data from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank), collectively constituting the studied RVA sequences. Considering the redundancy of online sequences, before the phylogenetic research, we reduced the redundancy of background sequences by eliminating those with high sequence similarity, based on CD-HIT [22]. Additionally, we selectively retained genotypes G1, G2, G3, G8, G9, P[4], and P[8], which encompass all genotypes of the contributed strains. The remaining genotypes, which were filtered out, constituted a minor proportion of the overall RVA genotype composition. This approach allows for a clearer observation of the evolutionary history of the contributed strains. Then, multiple sequence alignment was carried out on studied RVA sequences using MAFFT v7.520 [23]. The maximum likelihood method in IQ-TREE v2.1.4 was employed to construct phylogenetic trees for RVA [24]. For each genomic segment of RVA, a corresponding phylogenetic tree was constructed, resulting in a total of 11 trees.

Recombination analysis

We conducted a detailed recombination analysis of RVA strains. For this, we used sequences from 11 genomic segments that had been previously aligned. Recombination events were identified using the Recombination Detection Program (RDP4) v4.101 software [25]employing seven different computational models for recombination detection: RDP [26]GeneConv [27]Bootscan [28]MaxChi [29]CHIMAERA [30]SisScan [31]and 3SEQ19 [32]. These models were selected for their independence and the use of distinct detection algorithms, in line with approaches taken in similar recombinant studies. A recombination event was considered reliable if it was identified by at least four of the seven methods listed above.

Reassortment analysis

We primarily identified reassortment sequences by comparing the differences between phylogenetic trees. Specifically, we detect the reassortment events of a RVA strain by its inconsistent positions in the phylogenetic trees of different segments. Meanwhile, we also verified the detected reassortment from another perspective. Specifically, we concatenated the RVA genomic segments from 1 to 11 into a whole-genome sequence and conducted recombination analysis on the whole-genome sequence by RDP. According to the RDP results, recombination events occurring at the level of entire genomic segments can be recognized as a verified reassortment event.

Results

Epidemiological analysis of RVAs

From January 2020 to December 2023, the Shenzhen CDC collected fecal samples from diarrhea patients at four sentinel hospitals, while the Zhuhai CDC collected samples from three sentinel hospitals. A total of 5207 acute gastroenteritis samples were collected, among which 940 cases of viral diarrhea were detected by sentinel hospitals, with 158 of those being positive for rotavirus. The rotavirus positivity rate among AGE patients was 3.03%, and the positivity rate among patients with viral diarrhea was 16.81%. After nucleic acid extraction and PCR testing, we included 57 eligible samples with a CT value less than 28 for sequencing. Among these 57 samples, 48 were from children under 5 years old, accounting for 84.21%, which is consistent with previous studies [33]. The epidemiological information for these 57 samples is detailed (Table S1).

Whole-genome sequencing of 57 rotavirus samples yielded a total of 604 nucleotide sequences, reflecting the segmented nature of rotavirus. Among these, 40 strains were found to possess complete genome sequences, while 13 strains were missing only a single segment. All assembled sequences were successfully submitted to the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). The related information of those sequences was summarized (Table S2).

Genotype analysis of RVAs

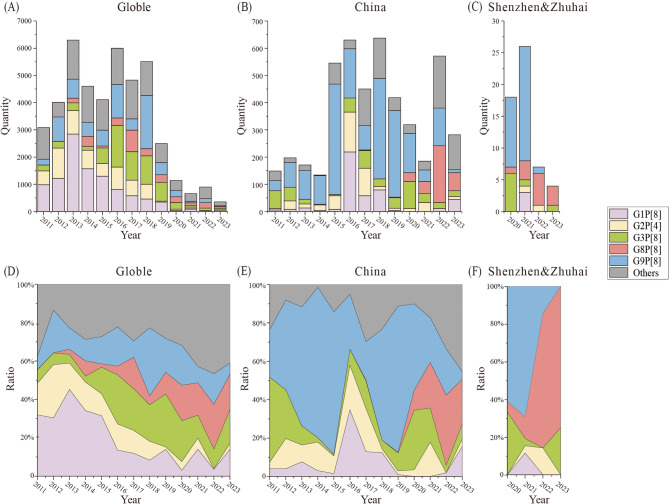

All contributed strains were genotyped successfully (Table S2). Among them, the most common G/P combined genotype was G9P[8] (52.63%, 30/57), followed by G8P[8] (21.05%, 12/57). To investigate the temporal trends of rotavirus genotypes, we compared the evolutionary trends of RVAs at different geographical levels. Specifically, we analyzed the prevalence of rotavirus genotypes post-2011 in both China and across the world, along with the trends observed in the Shenzhen and Zhuhai regions between 2020 and 2023 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The temporal genotype distribution of rotavirus in different geographical levels. Temporal distribution bar chart of RVA genotypes in Global (A), in China (B), in Shenzhen and Zhuhai (C). Temporal distribution percentage stacked area chart of RVA genotypes in Global (D), in China (E), in Shenzhen and Zhuhai (F) Different norovirus genotypes are indicated by color

In terms of genotypes, the distribution patterns demonstrated both similarities and differences across global, national, and regional levels. Globally, the G1P[8] genotype was predominantly circulating before 2015, accounting for the majority of cases (Fig. 1A, D). However, a decline of G1P[8] was observed afterward, with G3P[8] and G9P[8] emerging as the dominant genotypes. G3P[8] exhibited a sharp increase in prevalence, becoming the leading genotype worldwide, whereas G9P[8] increased more gradually. Additionally, G8P[8], though initially rare, had risen to prominence in recent years, even contributing to a decline in dominant strains such as G9P[8]. Similarly in China, the G1P[8] genotype also showed a decreasing trend, albeit with greater fluctuations compared to the global pattern (Fig. 1B, E). In China, G3P[8] and G9P[8] replaced G1P[8] as the predominant genotypes, consistent with global trends. However, a notable divergence occurred after 2020: the G8P[8] genotype, which was rare both globally and in China before this period, experienced a rapid and significant increase, establishing itself as a major genotype in the following years. This trend of G8P[8] expansion aligns with the global rise, but its increasing magnitude in China was particularly pronounced, leading to a more significant decline in dominant strains such as G9P[8] in recent years. In terms of Shenzhen and Zhuhai, their trends exhibited unique regional characteristics (Fig. 1C, F). The G9P[8], which had a significant presence in China, was also the dominant genotype in Shenzhen and Zhuhai between 2020 and 2021. However, in 2022 and 2023, the G8P[8] genotype suddenly became the majority and swept out previous local predominant strains like G9P[8], eventually accounting for a significant proportion of cases, reaching astonishing percentages of 71.43% and 75%, respectively. Although the growth trend of G8P[8] in Shenzhen and Zhuhai may align with that of China, the magnitude of such growth and sweeps in this region was significantly more pronounced.

Phylogenetic analysis of VP7 and VP4

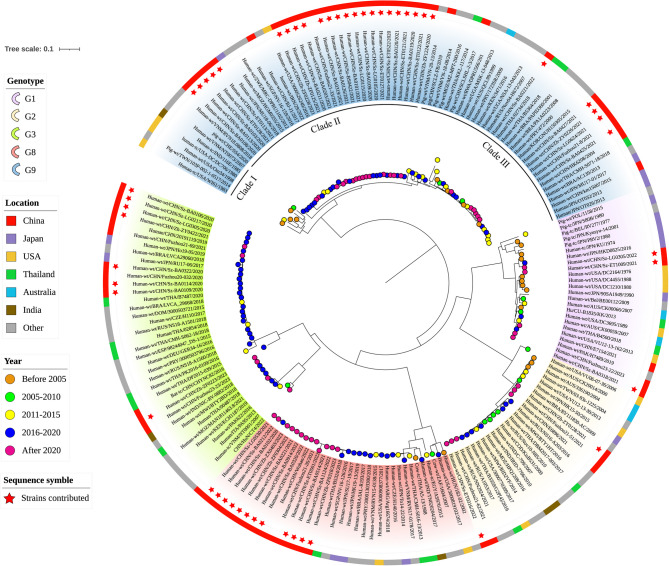

In this study, we conducted phylogenetic analyses of all rotavirus segments for the genetic relationships between our sequences and global RVA strains. Phylogenetic trees on the VP7 and VP4 genes were visualized (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively), with the other trees provided in the supplementary files (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of complete genome sequence of VP7 gene. The background color of the tree represents the genotype, the color strip outside depicts the location, and the color of solid circle represents the time. The strains contributed in this study are indicated by red stars outside. Other sequences can be downloaded from the GenBank database, with accession numbers shown in the Table S2.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of complete genome sequence of VP4 gene. The background color of the tree represents the genotype, the color strip outside depicts the location, and the color of solid circle represents the time. The strains contributed in this study are indicated by red stars outside. Other sequences can be downloaded from the GenBank database, with accession numbers shown in the Table S2

The phylogenetic tree for VP7 (Fig. 2) contained 53 newly sequenced strains, forming five major genotypes along with other RVA strains: G1, G2, G3, G8, and G9. Among these genotypes, the G9 genotype had the largest number of sequences in Shenzhen and Zhuhai. Hence, the G9 genotype predominated in Shenzhen and Zhuhai in 2020 and 2021, which is consistent with our previous observation (Fig. 1). This G9 genotype can be further divided into three evolutionary clades: Clade I, Clade II and Clade III. Among those clades, the majority of our contributed strains were clustered in Clade II, demonstrating a strong genetic relationship with strains in 2021 from Fuzhou, China. The remaining contributed strains were closely related to some strains reported in Japan in 2018. Within Clade III, most of the contributed strains exhibited a close genetic relationship with strains found in Fuzhou and Hong Kong, China, with one exceptional strain being far from others. Besides the G9 genotype, our contributed sequences were also widely distributed in the G8 genotype. Notably, these strains were clustered together and were genetically related to viral strains from Fuzhou and Wuhan during 2011–2022.

Moreover, we find some interesting phenomenon through the temporal distribution on the phylogenetic tree of VP7 (Fig. 2). Within the G9 genotype, all the strains in Clade I were relatively early, being before 2010. In Clade II, which contains the most newly sequenced strains, strains had a temporal distribution mostly after 2016, indicating that these strains have only been discovered in recent years. Clade III was an intermediate between Clade I and Clade II, evidenced by the presence of both older strains and recent ones. Distinct from the G9 genotype, the majority of G8 strains were generally recent. This phenomenon corresponds with our previous observation, indicating that G8 is an emerging novel genotype.

The phylogenetic tree for VP4 (Fig. 3) contained 54 newly sequenced strains and primarily demonstrated two major genetic lineages, P[4] and P[8]. Generally, P[8] comprised more than half of the tree, consistent with the previous report that P[8] was the predominant circulating rotavirus globally [34]. Within the P[8] branch, two evolutionary clades were formed, namely Clade I and Clade II. Clade II contains a significant number of prototype strains with high internal sequence similarity, clustered together on the phylogenetic tree, and are closely related to strains from Japan and Fuzhou, China. Clade I consists of P[8] strains that show genetic relationships similar to those found in India, USA, and Fuzhou, China. In terms of our contributed strains in P[8] genotype, most of them were distributed in Clade II, with only a few strains being classified into Clade I. In contrast to the P[8] genotype, P[4] only accounted for a small part of the evolutionary tree (Fig. 3). Similarly, the P[4] genotype only contains two strains contributed in this research. within the P[4] lineage are from Shenzhen and Zhuhai respectively. The G2P[4] strain from Shenzhen exhibits a close genetic relationship with strains from Fuzhou, China, Japan, and India, whereas the G2P[4] strain from Zhuhai shares a similar evolutionary relationship with strains from Australia, Japan, and Vietnam.

One intriguing phenomenon is that the lineages within the P[8] genotype can exhibit distinct temporal and regional distribution characteristics. Generally, the P[8] genotype consists of two major Clades: Clade I and Clade II. In Clade I, most of the strains date back to before 2015, with a relatively dispersed regional distribution, predominantly in the United States, India, China, and Australia. Notably, the evolution of this branch might come to an abrupt end without further development, instead giving rise to a new clade. On the contrary, most strains in Clade II were dated after 2016, suggesting that this group have been emerging in the past decade. In terms of the regional distribution, this clade was mainly distributed in East Asia, with the newly sequenced strains from China and closely related strains from Japan. This significant temporal and geographic differences between two P[8] evolutionary clades may indicate their different potential evolutionary directions of these clades.

Reassortment analysis of RVAs

In this study, we identified a genetic reassortment in a sequenced strain. This reassortment segment (PV943222, Fig. 4) was collected from Shenzhen in 2022. According to the phylogenetic trees, the VP7 segment of this strain was classified into the G9 genotype (Figs. 2 and 4A, VP7 segment), whereas the other segments were observed to be more closely related to corresponding segments of the G1 genotype. We selected three representative segments summarized in the reassortment analysis (Fig. 4B to D), with the complete phylogenetic trees of these nine segments presented in Fig. S1.

Fig. 4.

Reassortment analysis of the reassortant strain. Phylogenetic trees were presented for VP7 (A), VP2 (B), VP1 (C), and VP6 (D). The reassortant strain is indicated by red solid square outside. (E). Reassortment results verified by RDP. Reassortant strain name is highlighted in red. The colored lines represent the pairwise similarity between sequences

To further verify this reassortment, we choose the reassortment strain and its genetically related strains for further investigations. For each strain, we concatenated the genomic segments from 1 to 11 into a whole-genome sequence. Then, we conducted RDP analysis on those whole-genome sequences for recombination detections (Fig. 4E). A segment exchange was observed at VP7, in which the breakpoint of this genetic exchange was precisely located within the full-length region of the VP7 gene. Therefore, this result confirmed the occurrence of a reassortment event, in which the major parent was a G1P[8] strain from China, in 2022, and the minor parent was a G9P[8] strain from Uganda in 2013.

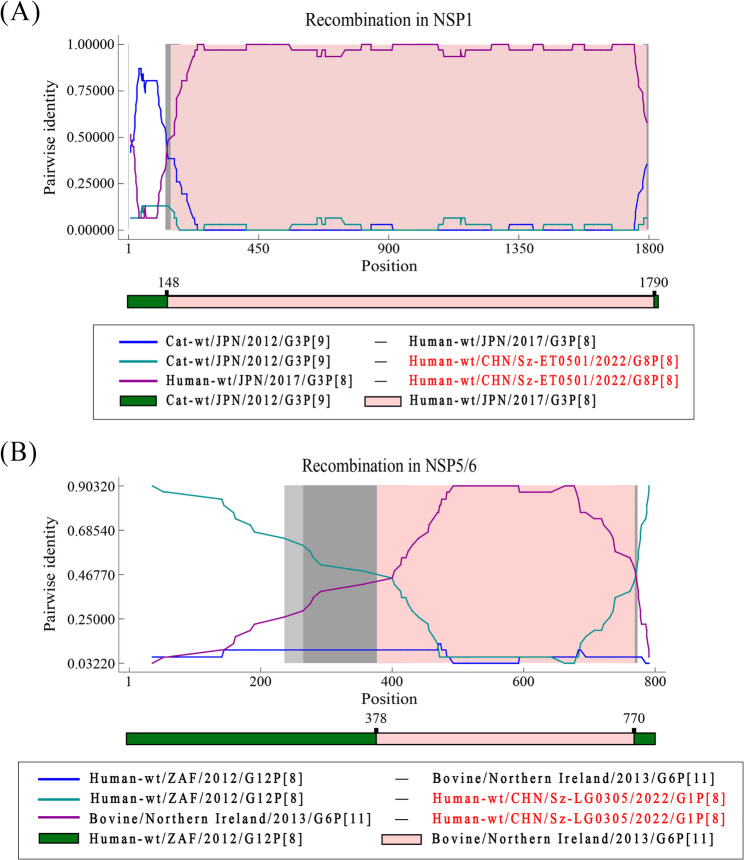

Recombination analysis of RVAs

Based on previous research [11–13]recombination is considered one significant driver of viral evolution. Consequently, we conducted a recombination analysis on all the 11 rotavirus gene segments by RDP4 (Fig. 5). The sequences used for recombination analysis included the remaining global RVA sequences and our own contributed sequences. We primarily focused on recombination events related to our newly sequences from the Shenzhen and Zhuhai. Overall, recombination events associated with our 57 newly sequenced strains included two cases.

Fig. 5.

Recombination analysis of rotavirus in NSP1 and NSP5/6. A. Event in NSP1. B Event in NSP5/6. The green line compares the minor parent to the recombinant, purple line compares the major parent to the recombinant, and the blue line compares the major parent to the minor parent. The gray areas represent the degree of confidence. Recombinant strain names are highlighted in red

One recombination event occurred in the NSP1 gene of the G8P[8] strain from Shenzhen (PV948568). The major parent was a G3P[9] strain from Japan in 2012 (LC790348), and the minor parent was a G3P[8] strain from Japan in 2017 (LC542388). The recombination breakpoints were located at 148 bp and 1790 bp, covering almost the entire fifth segment, which encodes the NSP1. The other recombination event was identified in the NSP5/6 gene of the G1P[8] strain (PV943291), also from Shenzhen. the major parent was a G12P[8] strain from South Africa in 2012 (KJ752360), and the minor parent was a G6P[1] strain from Ireland in 2017 (OL988992). The recombination breakpoints were found to be at 378 bp and 770 bp. Interestingly, the two fragments in the recombinant strain are approximately of the same length. Therefore, the genomic contribution of the major parent and the minor parent to the recombinant strain is nearly identical.

We also discovered a noteworthy phenomenon from a geographical perspective. The recombinant strains on NSP1 gene are derived from two Japanese strains, which is relatively reasonable considering Japan’s geographic proximity to China. However, for another recombinant strain on NSP5/6 gene, its recombination fragments are derived from a South African strain and an Irish strain, which can be vastly rare considering their geographic distances.

Discussion

Diarrhea caused by gastroenteritis viruses is a widespread infectious disease globally. It is a major contributor to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), accounting for 74.4 million DALYs in 2016, with 40.1 million occurring in children younger than 5 years old [35]. Rotavirus, as one of the most harmful diarrheal viruses, imposes a substantial disease burden annually. In China, numerous studies have analyzed the significant disease burden of rotavirus and have also identified some regional epidemics, suggesting a possible shift in rotavirus genotypes [36–40]. Based on this, our study focuses on two important special economic zone cities in Southern China: Shenzhen and Zhuhai. We collected diarrhea samples from these two regions, assembled genomic sequences, and conducted comprehensive evolutionary investigations on those strains, including genotype, phylogenetic analysis, reassortment research, and recombination investigations.

The distributions of RVA genotype in Shenzhen and Zhuhai reveals a significant trend: the decline of G9P[8] and the rise of G8P[8] (Fig. 1). In this trend, G8P[8] is a unique genotype. After emerging in China in 2020, it quickly became the dominant genotype, aggressively spreading and being reported in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and other regions in China [41–44]. Correspondingly, there have been reports of G8P[8] transmission globally in recent years [45–48]. These reports suggest that G8P[8] may possess higher viral fitness compared to other RVA strains in recent years. Considering the further expansion of RVA vaccination in recent years, one possible driving factor behind this phenomenon is that G8P[8] may have the potential to evade immunity provided by current rotavirus vaccines [49]. Notably, studies indicate that cross-protection against heterotypic strains also involves proteins other than VP7 and VP4, and variations in these regions may alter immune recognition [50]. Relevant literature indicates that G8P[8] exhibits genetic variations in certain epitopes that could potentially alter its immune recognition by vaccine-induced antibodies [51]. However, to date, there is limited evidence directly confirming this, making it an important focus of our future research.

Compared to other enteric viruses, one significant feature of rotavirus is the availability of vaccines, which may exert additional influence on its genetic evolution. Since the oral rotavirus vaccine was licensed in 2006 and the World Health Organization recommended rotavirus vaccination to all countries in 2009, over 100 countries have included rotavirus vaccines into their routine infant immunization programs for decades [52]. Although vaccines have a certain degree of effectiveness in preventing rotavirus infections, there are still concerns. After the vaccine introduction, the incidence of rotavirus disease dropped significantly in the first year, but the incidence has been increasing annually thereafter, suggesting that the vaccine may not provide long-lasting population immunity [43]. This phenomenon is also reflected in our findings. For example, there are significant fluctuations in certain RVA genotypes (Fig. 1), which may be influenced by the promotion of vaccines. In the phylogenetic trees on VP7 and VP4 gene (Figs. 2 and 3), some clades abruptly disappeared in earlier years. Meanwhile, we also observed some new clades for certain genotypes, suggesting significant genetic evolution of these strains. These phenomena, including the fluctuation of older strains and the rise of new ones, might be attributed to the widespread use of vaccines, which could have altered the selection pressures on RVA, thereby shifting its evolutionary trajectory. Relevant studies have also shown that certain strains developed resistance to the vaccine, thereby achieving higher adaptability and transmissibility within vaccinated populations [53].

In terms of China, the licensed vaccines include Lanzhou lamb rotavirus vaccine (LLR, Lanzhou Institute of Biological Products, Lanzhou, China) and RotaTeq (Merck & Co., West Point, PA, USA) [54]. Specifically, LLR, domestically developed in 2000, covers the rotavirus G10P[15], whereas RotaTeq, introduced in 2018, covers G1–G4, G9, P[5] and P[8] [55]. According to our observations (Fig. 1), the prevalence of rotavirus genotype G1P[8] in China had nearly vanished, and the quantity of G9P[8] had significantly decreased. Notably, these changes coincided with the introduction of RotaTeq in 2018, suggesting a possible temporal association. This phenomenon is similar to other countries after the introduction of the vaccine [56–59]due to the protective effect of the rotavirus vaccine against the same G and P genotypes. However, the heterospecific and cross-reactive responses caused by RotaTeq may be relatively limited. Therefore, the genotype G8P[8], which was previously absent in China, gradually became dominant after the introduction of RotaTeq (Fig. 1), due to RotaTeq’s lack of coverage for G8. This phenomenon can be also observed in our results in Shenzhen and Zhuhai, suggesting that these newly emerging RVA genotypes could gradually become dominant strains. This trend poses new challenges for public health interventions. In our subsequent work, it is essential to maintain continuous monitoring of rotavirus prevalence and genotype dynamics to prevent and control potential outbreaks.

Regarding the phylogenetic analysis, our studies revealed the genetic diversity of rotavirus on VP7 gene in Shenzhen and Zhuhai (Fig. 2). Among various genotypes of VP7, the G9 genotype has the most frequently detected in RVA-positive samples. G9 is divided into three clades, each with its own temporal and geographical characteristic. Clade I includes no newly sequenced strains from Shenzhen and Zhuhai. Meanwhile, most of its strains are distributed in the United States with a relatively early temporal distribution. This may indicate that this clade is possibly the progenitor of the G9 type. Clade II contains most of the strains contributed in this study, with an overall temporal distribution in recent years. These strains have a close genetic relationship with strains from Vietnam, Japan, and Fuzhou China, suggesting a potential transmission route among surrounding Asian countries. Regarding Clade III, its strains show a close genetic relationship with strains from Hong Kong and Fuzhou in China, indicating a possible domestic diffusion process. Another important genotype is G8P[8], which emerged and rapidly dominated in multiple regions of China, supplanting previous predominant strains in Shenzhen and Zhuhai between 2022 and 2023. According to previous research, the G8 genotype initially emerged from bovine hosts [60]. This can be verified by the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2), in which bovine rotavirus appears in the G8 genotype, whereas it does not appear in other genotypes. The bovine origin of the G8 genotype suggests that cross-species transmission is possible from animals to humans in RVA. In fact, previous studies have reported such phenomena, primarily involving recombination and reassortment events between animal and human rotavirus genes within a host organism. Considering that recombinant and reassortant strains have already been identified in RVA strains we sequenced, the risk posed by other zoonotic RVA strains cannot be ignored.

Following the phylogenetic analysis of the VP7 gene, a similar approach was applied to the VP4 gene to further explore the genetic variation and evolutionary dynamics of rotavirus. The phylogenetic tree of VP4 (Fig. 3) is mainly divided into P[4] and P[8] genotypes. The P[4] genotype appears to be an earlier genotype, with the earliest P[4] strains traceable to the 1970s. Interestingly, despite its early origin, P[4] strains are still circulating at present. For instance, this research contributed a G2P[4] strain in Shenzhen in 2022, suggesting that P[4] is undergoing a low-scale but persistent transmission process. The P[8] genotype, on the other hand, is the most predominant rotavirus genotype and can be primarily divided into Clade I and Clade II. From the perspective of temporal distribution, Clade II emerged abruptly as a new lineage from Clade I, with a relatively recent distribution. Clade I, in contrast, represents a relatively older lineage. From the perspective of geographic distribution, most strains in Clade II are concentrated in China and Japan, whereas Clade I contains a higher proportion of strains originating from western countries like the United States. This regional divergence between the two clades may be related to the observed differences in viral evolution and transmission patterns.

Genetic reassortment is a significant feature that distinguishes rotavirus from other enteric viruses. Reassortment can exchange the whole genomic segment, which significantly changes the viral genome. It has long been recognized as a common and critical driving force of viral evolution. Multiple studies have reported on the reassortment evolution of rotavirus, including reassortment with vaccine strains and animal strains [61, 62]. One study specifically identified a reassortant strain involving the NSP4 gene in China in 2023, which has been suggested to enhance the viral ability for immune escape [63]. Although several studies have identified reassortment events in rotavirus, reassortment involving the VP7 gene is relatively rare. Nevertheless, this research identified a rare and valued reassortment event related to the VP7 gene (Fig. 4). Specifically, this strain was categorized into the G9 type in VP7 gene, whereas all its other segments were clustered within the G1 type. The VP7 gene is one of the most important genes of rotavirus and forms the basis for the viral nomenclature, playing a decisive role in the viral transmissibility and pathogenicity [53]. Considering the significance of VP7, the reassortant strain we identified on VP7 gene could potentially have a significant impact on the subsequent transmission and evolution of rotavirus. Therefore, the emergence of rare reassortant strains further enhances the necessity for surveillance, which is also one of the key directions for our future work.

Recombination is likewise a significant evolutionary mechanism for viruses. Previous recombination analyses have identified 109 potential recombination events, 67 of which were strongly supported [64]. They proved that the recombination may be a significant driver of rotavirus evolution and may influence circulating strain diversity. In this study focusing on rotavirus in Shenzhen and Zhuhai, we identified two recombination events (PV948568 and PV943291), located in NSP1 and NSP5/6 respectively (Fig. 5). Notably for NSP1 recombination event, the recombination region covers a large portion of the segment, exhibiting a strong recombination signal. One important phenomenon is that both recombination strains were genetically related to animal origins in their parentage. For the first recombinant event, its primary parent for the segment 5 was classified as a cat rotavirus (Fig. 5A). On the contrary, for the other recombinant event, the secondary parent for the segment 11 was categorized into the bovine rotavirus. This recombination suggests that a genetic exchange between animal and human rotavirus in a recombinant rotavirus, which could be relatively common according to relevant reports [65, 66]. Meanwhile, such a recombination event between viruses of different hosts can be a significant driver for the rotavirus evolution, which enables the new virus to potentially become zoonotic or even acquire the ability for cross-species transmission, thereby triggering emerging outbreaks. This highlights that the recombination and evolutionary characteristics of RVA exhibit greater diversity and complexity, emphasizing the critical importance of comprehensive monitoring and prevention strategies.

Conclusions

This research conducted an in-depth investigation and characterization of the genomic sequences of rotavirus infections in clinical samples collected from Shenzhen and Zhuhai between 2020 and 2023, in the background of global RVA sequences. The genotype statistical analysis exhibited regular changing patterns in global, China and Shenzhen and Zhuhai, characterized by a shift in the predominant genotypes every few years. Currently, the G9P[8] genotype is gradually decreasing and G8P[8] is becoming prevalent in China. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the newly sequenced RVA strains are genetically more similar to viruses from Japan, Fuzhou in China, and other Asian regions. Notably, we identified a rare reassortment event of G1 becoming G9 in Shenzhen in 2022 exhibited in the VP7 gene. RDP analysis detected recombination events in NSP1 gene and NSP5/6 gene. This study provides valuable insights into the evolution of RVA in Southern China. Continuous surveillance of RVA genotypes and evolutionary characteristics is crucial for epidemic prevention and vaccine evaluation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the researchers and laboratories for sharing the genome sequences via GenBank.

Authors’ contributions

HMD, LYX, ZR and WX performed the research and analyzed the data. LYQ, HHT and YWS collected the samples. LKX, LWQ and FJJ sequenced the viral genomes. WBQ, ZXR and AMT participated in analysis and discussion. WX, ZR, HMD and RHG drafted the manuscript. SHB, RHG and HXF conceived the study. All authors contributed to the study and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 7232229), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 32070025, 62206309), the Research Project of the State Key Laboratory of Pathogen and Biosecurity (grant nos. SKLPBS2214, SKLPBS2234).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

I certify that this manuscript is original and has not been published and will not be submitted elsewhere for publication while being considered by BMC Genomics. The study is not split up into several parts to increase the quantity of submissions and submitted to various journals or to one journal over time. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines and regulations for research involving human subjects. The collection and use of human stool samples were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Shenzhen CDC and the Zhuhai CDC (approval numbers: SZCDC-IRB2024032).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mingda Hu, Yixiong Lin, Rui Zhang and Xin Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hongbin Song, Email: hongbinsong@263.net.

Hongguang Ren, Email: bioren@163.com.

Xiaofeng Hu, Email: xiaofenghu1988@sohu.com.

References

- 1.Rossouw E, Brauer M, Meyer P, du Plessis NM, Avenant T, Mans J. Virus etiology, diversity and clinical characteristics in South African children hospitalised with gastroenteritis. Viruses. 2021;13(2):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn TG, Olortegui MP, Kosek MN. Viral gastroenteritis. Lancet. 2024;403(10429):862–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang L, Shi S, Na C, et al. Rotavirus and norovirus infections in children under 5 years old with acute gastroenteritis in Southwestern China, 2018–2020. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022;12(3):292–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troeger C, Khalil IA, Rao PC, et al. Rotavirus vaccination and the global burden of rotavirus diarrhea among children younger than 5 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(10):958–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah PNM, Gilchrist JB, Forsberg BO, et al. Characterization of the rotavirus assembly pathway in situ using cryoelectron tomography. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31(4):604–e6154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Z, Zhao S, Jin X, Wen X, Ran X. Host and structure-specific codon usage of G genotype (VP7) among group A rotaviruses. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11: 1438243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthijnssens J, Ciarlet M, Rahman M, et al. Recommendations for the classification of group A rotaviruses using all 11 genomic RNA segments. Arch Virol. 2008;153(8):1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford SE, Ramani S, Tate JE, et al. Rotavirus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donato CM, Roczo-Farkas S, Kirkwood CD, Barnes GL, Bines JE. Rotavirus disease and genotype diversity in older children and adults in Australia. J Infect Dis. 2020;225(12):2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damtie D, Gelaw A, Wondimeneh Y, et al. Rotavirus A infection prevalence and spatio-temporal genotype shift among under-Five children in Amhara National regional state, ethiopia: a multi-center cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2024;12(8):866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasebotsa S, Mwangi PN, Mogotsi MT, et al. Whole genome and in-silico analyses of G1P[8] rotavirus strains from pre- and post-vaccination periods in Rwanda. Sci Rep. 2020;10:13460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mwangi PN, Mogotsi MT, Seheri ML, et al. Whole genome in-silico analysis of South African G1P[8] rotavirus strains before and after vaccine introduction over a period of 14 years. Vaccines. 2020;8(4): 609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallah T, Mansour Ghanaiee R, Karimi A, Zahraei SM, Mahmoudi S, Alebouyeh M. Comparative analysis of the RVA VP7 and VP4 antigenic epitopes circulating in Iran and the Rotarix and RotaTeq vaccines. Heliyon. 2024;10(13):e33887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian Y, Yu F, Zhang G, et al. Rotavirus outbreaks in China, 1982–2021: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1423573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo Hongmei. Analysis of epidemiological characteristics of report cases of rotavirus diarrhea in children under 5 years old in China, 2005–2018. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine. Published online February 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Zhu YN, Ye YH, Zhang Z, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of parechovirus A in children with acute gastroenteritis in Shenzhen, 2016–2018. Arch Virol. 2020;165(6):1377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu W, Yang H, long Zhang H, et al. Surveillance of pathogens causing gastroenteritis and characterization of Norovirus and Sapovirus strains in Shenzhen, China, during 2011. Arch Virol. 2014;159(8):1995–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE, Unicycler. Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(6):e1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma C, Gunther S, Cooke B, Coppel RL. Geneious plugins for the access of PlasmoDB and PiroplasmaDB databases. Parasitol Int. 2013;62(2):134–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(23):3150–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katoh K, Kuma K, ichi, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(2):511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-tree: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;32(1):268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genetic characteristics of classical astroviruses in Shenzhen. China, 2016–2019 - Hu– 2023 - Journal of Medical Virology - Wiley Online Library. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Martin D, Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(6):562–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin DP, Lemey P, Lott M, Moulton V, Posada D, Lefeuvre P. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2462–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin DP, Posada D, Crandall KA, Williamson C. A modified bootscan algorithm for automated identification of recombinant sequences and recombination breakpoints. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21(1):98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldo L, Bordenstein S, Wernegreen JJ, Werren JH. Widespread recombination throughout Wolbachia genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(2):437–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaya FR, Brito BP, Darling AE. Evaluation of recombination detection methods for viral sequencing. Virus Evol. 2023;9(2): vead066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalton CS, Workentine ML, Leclerc LM, Kutz S, van der Meer F. Next-generation sequencing approach to investigate genome variability of parapoxvirus in Canadian muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus). Infect Genet Evol. 2023;109: 105414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bay RA, Bielawski JP. Recombination detection under evolutionary scenarios relevant to functional divergence. J Mol Evol. 2011;73(5–6):273–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen AL, Platts-Mills JA, Nakamura T, et al. Aetiology and incidence of diarrhoea requiring hospitalisation in children under 5 years of age in 28 low-income and middle-income countries: findings from the global pediatric diarrhea surveillance network. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(9):e009548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadiq A, Khan J. Rotavirus in developing countries: molecular diversity, epidemiological insights, and strategies for effective vaccination. Front Microbiol. 2024;14:1297269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collaborators G. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(11):1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X, Li S, Yu J, et al. Establishment of a reverse genetics system for rotavirus vaccine strain LLR and developing vaccine candidates carrying VP7 gene cloned from human strains circulating in China. J Med Virol. 2024;96(12): e70065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo X, Deng J, Luo M, Yu N, Che X. Detection and characterization of bacterial and viral acute gastroenteritis among outpatient children under 5 years old in Guangzhou, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024;110(4):809–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang S, Tian L, Lu Y, et al. Synergistic effects of rotavirus and co-infecting viral enteric pathogens on diarrheal disease - Guangzhou city, Guangdong province, China, 2019. China CDC Wkly. 2023;5(33):725–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang H, Zhang Y, Xu X et al. Clinicpidemiological, and genotypic characteristics of rotavirus infection in hospitalized infants and young children in Yunnan Province. Arch Virol. 2023;168(9):229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Wang SJ, Chen LN, Wang SM, et al. Genetic characterization of two G8P[8] rotavirus strains isolated in Guangzhou, China, in 2020/21: evidence of genome reassortment. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Wang Y, Chen N, et al. Surveillance of human rotaviruses in Wuhan, China (2019–2022): Whole-genome analysis of emerging DS-1-like G8P[8] rotavirus. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15): 12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiao Y, Han T, Qi X, et al. Human rotavirus strains circulating among children in the capital of China (2018–2022)_ predominance of G9P[8] and emergence of G8P[8]. Heliyon. 2023;9(8): e18236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian Y, Shen L, Li W, et al. Major changes in prevalence and genotypes of rotavirus diarrhea in Beijing, China after RV5 rotavirus vaccine introduction. J Med Virol. 2024;96(5):e29650. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Zhong H, Jia R, Xu M, et al. Emergence and high prevalence of unusual rotavirus G8P[8] strains in outpatients with acute gastroenteritis in Shanghai, China. J Med Virol. 2024;96(1): e29368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan-It W, Chanta C, Ushijima H. Predominance of DS-1-like G8P[8] rotavirus reassortant strains in children hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in Thailand, 2018–2020. J Med Virol. 2023;95(6): e28870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medeiros RS, França Y, Viana E, et al. Genomic constellation of human rotavirus G8 strains in Brazil over a 13-year period: detection of the novel bovine-like G8P[8] strains with the DS-1-like backbone. Viruses. 2023;15(3):664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Degiuseppe JI, Torres C, Mbayed VA, Stupka JA. Phylogeography of rotavirus G8P[8] detected in Argentina: evidence of transpacific dissemination. Viruses. 2022;14(10):2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim KG, Kee HY, Park HJ, Chung JK, Kim TS, Kim MJ. The long-term impact of rotavirus vaccines in Korea, 2008–2020; emergence of G8P[8] strain. Vaccines. 2021;9(4): 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou W, Yu Q, Liu Y, et al. Genotype analysis of rotaviruses isolated from children during a phase III clinical trial with the hexavalent rotavirus vaccine in China. Virol Sin. 2023;38(6):889–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heylen E, Zeller M, Ciarlet M et al. Comparative analysis of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine strains and G8 rotaviruses identified during vaccine trial in Africa. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Park JG, Alfajaro MM, Cho EH, et al. Development of a live attenuated trivalent porcine rotavirus A vaccine against disease caused by recent strains most prevalent in South Korea. Vet Res. 2019;50:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burnett E, Parashar UD, Tate JE. Global impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrhea hospitalizations and deaths among children < 5 years old: 2006–2019. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(10):1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li W, Lei M, Li Z, et al. Development of a genetically engineered bivalent vaccine against Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and Porcine rotavirus. Viruses. 2022;14(8):1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee B. Update on rotavirus vaccine underperformance in low- to middle-income countries and next-generation vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;17(6):1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathew S, Khatib HAA, Ibrahim MA, et al. Vaccine evaluation and genotype characterization in children infected with rotavirus in Qatar. Pediatr Res. 2023;94(2):477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeller M, Patton JT, Heylen E, et al. Genetic analyses reveal differences in the VP7 and VP4 antigenic epitopes between human rotaviruses circulating in Belgium and rotaviruses in rotarix and RotaTeq. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(3):966–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeller M, Rahman M, Heylen E, et al. Rotavirus incidence and genotype distribution before and after National rotavirus vaccine introduction in Belgium. Vaccine. 2010;28(47). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Tosisa W, Regassa BT, Eshetu D, Irenso AA, Mulu A, Hundie GB. Rotavirus infections and their genotype distribution pre- and post-vaccine introduction in Ethiopia: a systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matthijnssens J, Heylen E, Zeller M, Rahman M, Lemey P, Van Ranst M. Phylodynamic analyses of rotavirus genotypes G9 and G12 underscore their potential for swift global spread. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(10):2431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Damtie D, Gelaw A, Wondimeneh Y, et al. Prevalence, genotype diversity, and zoonotic potential of bovine rotavirus A in Amhara National regional state, Ethiopia: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Virus Res. 2024;350: 199504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gentsch JR, Laird AR, Bielfelt B, et al. Serotype diversity and reassortment between human and animal rotavirus strains: implications for rotavirus vaccine programs. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(Suppl 1):S146–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miao Q, Pan Y, Gong L, et al. Full genome characterization of a human-porcine reassortment G12P[7] rotavirus and its pathogenicity in piglets. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69(6):3506–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peng R, Li D, Wang J, et al. Reassortment and genomic analysis of a G9P[8]-E2 rotavirus isolated in China. Virol J. 2023;20(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoxie I, Dennehy JJ. Intragenic recombination influences rotavirus diversity and evolution. Virus Evol. 2020;6(1): vez059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gao L, Shen H, Zhao S, et al. Isolation and pathogenicity analysis of a G5P[23] Porcine rotavirus strain. Viruses. 2023;16(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Charoenkul K, Janetanakit T, Bunpapong N, et al. Molecular characterization identifies intra-host recombination and zoonotic potential of canine rotavirus among dogs from Thailand. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68(3):1240–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.