Abstract

Purpose

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a prevalent liver disease characterized by steatosis, inflammation, and liver injury. Despite its increasing incidence, effective treatments are limited. Butein, a flavonoid with anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, has not been thoroughly studied for its potential therapeutic effects in NASH. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of butein in NASH using both in vivo and in vitro experimental models, with emphasis on elucidating the underlying molecular signaling mechanisms.

Methods

The leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mouse model of NASH, induced by the Gubra amylase NASH (GAN) diet, was employed to assess the therapeutic effects and mechanistic pathways of butein treatment. In vitro investigations utilized palmitic acid-induced HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and LX-2 hepatic stellate cells to explore butein’s impact on oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and fibrotic processes.

Results

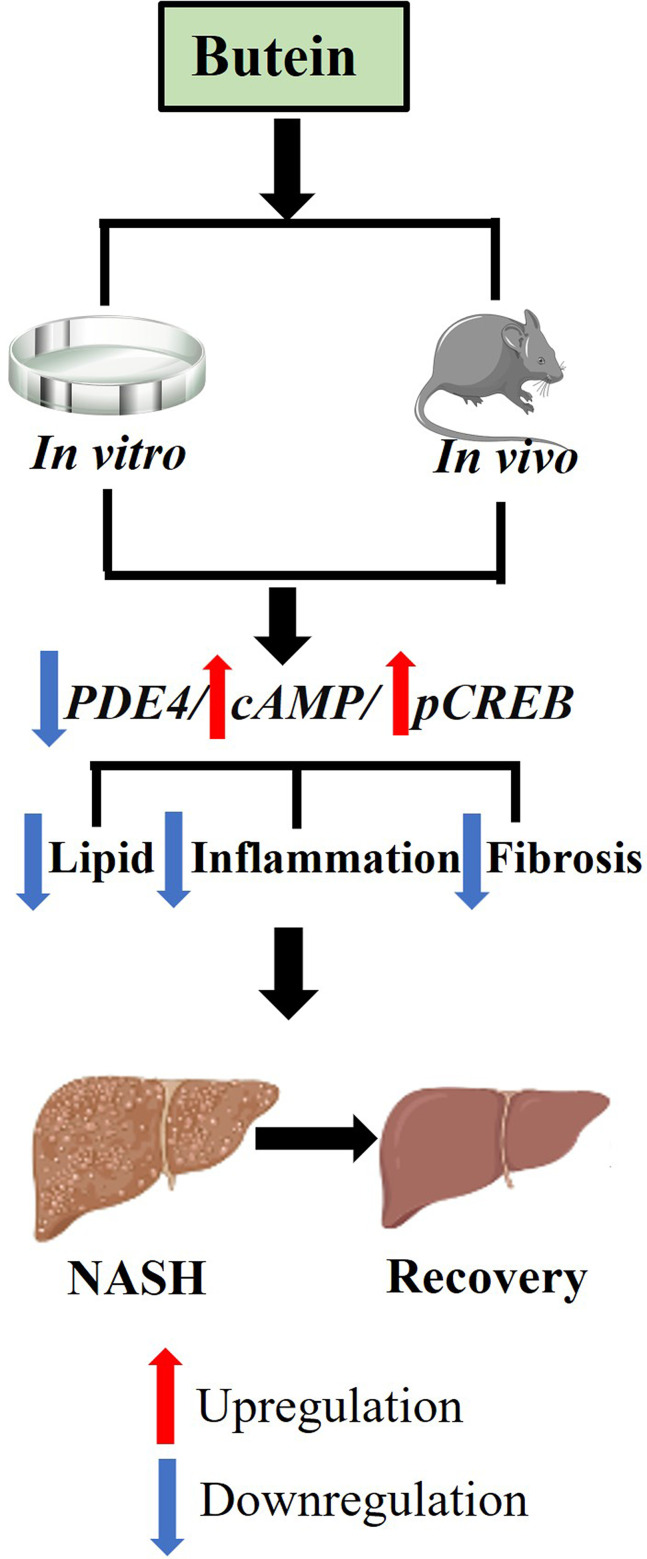

Butein treatment resulted in significant amelioration of glucolipid metabolism dysregulation, hepatic inflammation, and liver fibrosis in the mouse model, potentially mediated through modulation of the PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB signaling pathway. In in vitro experimental models, butein effectively attenuated lipid-induced oxidative stress in HepG2 cells and reduced inflammatory and fibrotic responses in LX-2 cells, demonstrating consistent protective effects across both experimental models.

Conclusion

These findings establish the protective effects of butein against NASH progression through PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathway modulation, supporting its potential as a therapeutic candidate for NASH treatment pending further clinical validation.

Keywords: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, lipid metabolism, inflammation, fibrosis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by lipid accumulation in more than 5% of hepatocytes without significant alcohol consumption, covering a range from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).1 NASH involves steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning and lobular inflammation, which raises the risk of severe fibrosis or cirrhosis in around 30% of cases.2–4 The pathogenesis of NASH progression remains unclear and Resmetirom is currently the only FDA-approved drug for treating moderate to severe liver fibrosis in NASH, representing a major advancement in its treatment. However, this approval is limited to a specific patient population, leaving those with earlier stages of NASH without effective treatments.5,6 Current treatments, including lifestyle changes and off-label drugs, show limited efficacy.7 The lack of targeted therapies for specific subgroups (eg, metabolic comorbidities) and the economic burden of NASH underscore the urgent need for more effective and inclusive therapies.8

Butein (3,4,2′,4′-tetrahydroxy chalcone), a constituent of the chalcone subclass within the flavonoid family, has been isolated from various botanical sources. This compound exhibits a multifaceted pharmacological profile, manifesting anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant, which underscores its potential as a therapeutic agent.9–16 It has been reported that butein is active in liver disease, especially in liver fibrosis, by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell proliferation, or reducing hydroxyproline and malondialdehyde levels in liver fibrosis mouse model induced by CCl4.17,18 While cell-based models provide important mechanistic insights, they fail to replicate the complex in vivo environment of liver disease. Conversely, CCl4-induced fibrosis models, although useful for rapid fibrosis induction, are limited by their high toxicity and inability to fully replicate the progressive, multifactorial nature of NASH.19,20 These shortcomings underscore the relevance of the current study, which employs more clinically relevant models to more effectively assess the therapeutic potential of butein in NASH.

There are many ways to model NASH or liver fibrosis. Among them, dietary models, chemical models and genetic models are the most common approach to study the NASH or liver fibrosis.21,22 Compared with chemical models, dietary models are more similar to the physiological, metabolism and histopathology of human NASH or liver fibrosis development. Studies have shown that butein protects the NAFLD in rats with methionine- and choline-deficient (MCD), by decreased hepatic lipid accumulation and oxidative stress.23 However, the effort of butein on progressive form NASH or liver fibrosis need to be further investigate. The MCD diet model is useful for studying early-stage NASH, especially inflammation and steatosis, but it does not replicate metabolic dysfunctions like insulin resistance and hyperlipidemia.24 In contrast, the Gubra amylase NASH (GAN)-diet model induces both metabolic dysfunction and fibrosis progression, offering a more comprehensive model that better reflects human NASH.25,26 Therefore, the GAN model is more suitable for evaluating the therapeutic effects of compounds like butein in advanced NASH stages.

The phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4)/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (p-CREB) signaling axis represents a critical regulatory network in hepatic pathophysiology.27 Dysregulation of this pathway has been increasingly recognized as a key pathogenic mechanism in chronic liver diseases, particularly NASH.28,29 Given the central role of PDE4 in modulating hepatic inflammatory and fibrotic processes, targeting this pathway represents a promising therapeutic strategy for liver disease intervention. Therefore, this study aims to investigate whether butein, as a PDE4 inhibitor, can exert its hepatoprotective effects through the PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathway.

To address this question, we employed a comprehensive experimental approach utilizing both in vivo and in vitro models. The therapeutic efficacy and underlying mechanisms of butein in NASH and liver fibrosis were evaluated using a GAN diet-induced ob/ob mouse model, with particular focus on metabolic and biochemical parameters, hepatic pathology, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease activity score (NAS), and fibrosis staging following 46 days of treatment. To further elucidate the cellular mechanisms, butein’s effects were investigated using palmitic acid (PA)-induced hepatic steatosis models in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells and hepatic stellate LX-2 cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals, Diet, and Drug Intervention

Male C57BL/6J and ob/ob mice, aged 24 weeks, were procured from Cavens Animal Inc. All mice were housed in a controlled environment (12 h light/dark cycle, temperature 22 ± 2°C, humidity 50 ± 10%). After adaptive feeding for one week, mice were stratified based on initial body weight (divided into light, medium, and heavy tertiles) and baseline liver function markers (ALT and AST levels). Within each stratum defined by these parameters, animals were randomly allocated to three experimental groups (n = 7 per group) using stratified randomization to ensure balanced baseline characteristics and minimize selection bias. The experimental groups comprised: the normal chow (NC) group consisting of C57BL/6J mice fed a standard chow diet, the vehicle control group consisting of ob/ob mice consuming a GAN diet (D09100310, Research Diets) with saline administration, and the butein treatment group consisting of ob/ob mice consuming a GAN diet with butein administration (200 mg/kg, orally, twice daily for 46 days). Parameters including food intake, body weight, and blood glucose levels were monitored regularly throughout the experimental period. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethical Committee of Shanxi Medical University.

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

Following a 12-hour fasting period on day 46, the mice received an oral glucose dose (2 g/kg body weight). Blood samples were collected from the tail vein at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min post-administration to measure glucose levels using a glucose meter (Abbott Diabetes Care Ltd.). The glucose area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using Origin Pro 9.0.

Serum and Hepatic Biomarker Analysis

Fasting blood glucose (FBG) and fasting insulin (FINS) levels were determined in blood samples using a glucose meter and an ELISA kit, respectively. Serum and hepatic parameters, including triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) and free fatty acids (FFA), were analyzed using an automatic biochemical analyser (Lcubio Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd). Levels of cAMP and inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-10 (IL-10), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) were assessed using ELISA kits. All assays were performed in triplicate, and the researchers conducting the analyses were blinded to the group allocations to minimize potential bias.

Histopathological Evaluation

Liver tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 10 μm slices. Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), Oil Red O, and Sirius Red to assess histological alterations. Stained sections were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ci-L microscope. To quantify lipid accumulation, Oil Red O-stained areas were analyzed, and the percentage of lipid droplet area was calculated by comparing the stained area to the total tissue area using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software. All histopathological analyses, including staining, imaging, and scoring, were performed by researchers blinded to experimental group allocation to minimize bias.

Cell Culture, Treatments and Oil Red O Staining

HepG2 and LX-2 cells were purchased from Boster Biological Technology Limited. Cells were cultured in DMEM/HIGH medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Solarbio). For steatosis induction, PA (Solarbio) was prepared by complexing with bovine serum albumin (BSA) at a molar ratio of 2:1 to ensure optimal solubility and cellular uptake. Briefly, 0.25 mmol/L PA was dissolved in serum-free medium containing BSA, and the resulting PA-BSA complex was sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter. Cells were treated with the 0.25 mmol/L PA-BSA complex in serum-free medium for 24 hours to induce lipid accumulation, while control cells received equivalent volumes of saline. Post-PA treatment, cells were treated with 5 μM butein for HepG2 cells or 2.5 µM or 5 µM butein for LX-2 cells or saline for 24 hours. Biochemical parameters in the supernatant, such as ALT, AST, TG, TC, LDH and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were analyzed using an automatic biochemical analyzer. Oil Red O staining was performed on HepG2 cells, which were fixed, stained, and imaged under a phase-contrast inverted microscope at 200× magnification. All experiments were performed with biological replicates (at least three independent samples).

Western Blot Analysis

Liver tissue proteins were extracted using enhanced RIPA buffer, with concentrations determined by BCA kit (Boster). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (BIO-RAD) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Blots were probed with antibodies against CREB, p-CREB, and GAPDH (1:1000; Abcam), visualized, and quantified using a ChemiDocTM XRS+ system with Image LabTM software (BIO-RAD). All experiments were performed with biological replicates (at least three independent samples).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from liver and cell samples using an RNA Rapid Extraction Kit (Mei5bio) and quantified with a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA synthesis was performed using PrimeScriptTM RT Master Mix (TaKaRa), followed by qPCR using Ultra SYBR Mastermix (CoWin Biosciences) with specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). RT-qPCR was conducted on a Bio-Rad C1000 Touch. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 15 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. After the final extension, melting curve analysis was performed by heating from 65°C to 95°C at a rate of 0.5°C per second. Expression levels of IL-6, IL-1β, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), type 1 collagen α1 (COL1A1), matrix metallopeptidase-9 (MMP-9), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), PDE 4B and PDE4D were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method with GAPDH as the reference gene. All experiments were performed with biological replicates (at least three independent samples).

Gene Expression Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis between hepatic triglyceride levels and gene expression was performed using Sparse Partial Least Squares (SPLS) software. Liver tissue samples from NC, Vehicle, and Butein groups were analyzed to determine associations between hepatic TG content and target gene expression levels. The analysis included fibrosis-related genes (COL1A1, TGF-β, TIMP-1) and inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α). Correlation coefficients were calculated to quantify the strength and direction of relationships between TG levels and individual gene expression patterns. Results were visualized using correlation matrix plots, where circle size represents correlation magnitude and numerical values indicate specific correlation coefficients.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Prior to statistical analysis, assumptions for one-way ANOVA were verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality of residuals and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Results

Butein Attenuated GAN Diet-Induced Obesity, Glucose Intolerance and Insulin Resistance

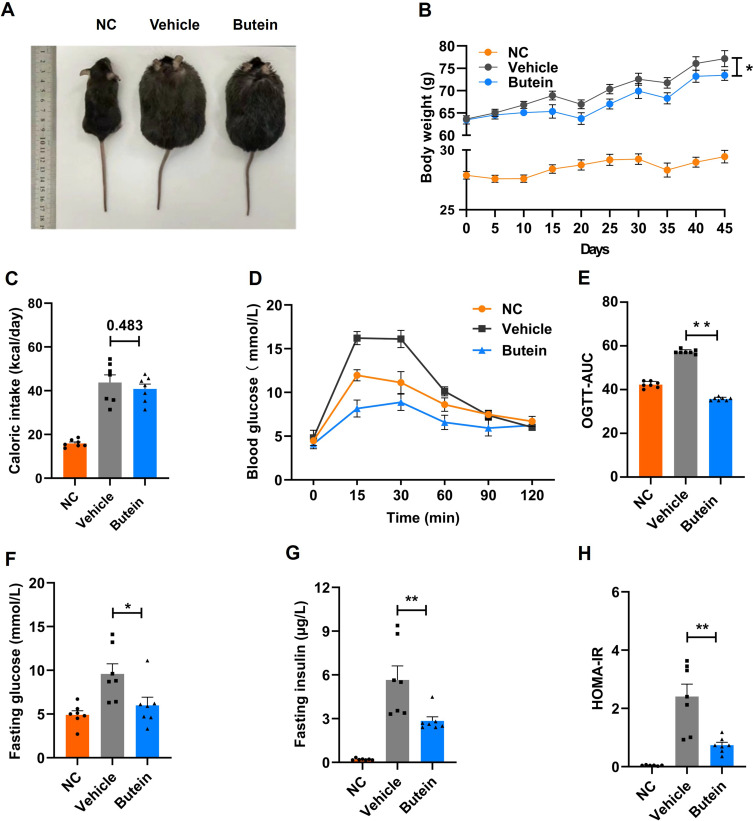

To investigate the therapeutic effects of butein on NASH, we administered a GAN diet to aged ob/ob mice for 46 days to establish a NASH model. As demonstrated in Figure 1A and B, by day 45 of treatment, the vehicle group of ob/ob mice attained an average body weight of 77.2 ± 1.8 g, representing an approximately 2.6-fold increase relative to age-matched C57BL/6J mice maintained on normal chow diet (NC group; 29.4 ± 0.5 g). Butein administration resulted in a significant reduction in body weight to 73.4 ± 1.1 g compared with the vehicle group. Notably, daily caloric intake remained comparable between butein-treated and vehicle groups, with no significant difference observed (p = 0.483) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Butein mitigates GAN diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance without impacting food intake in GAN ob/ob mice. (A) Depiction of the external morphological characteristics of mice at 46 days. (B) Growth curve illustrating body weight changes over time. (C) Representation of caloric intake (Kcal/day). (D–E) The plasma glucose profile following a 2 g/kg glucose oral challenge in mice and the mean area under the curve (AUC) measured between 0 and 120 minutes post-glucose loading. (F–H) Fasting glucose concentration, fasting insulin concentration, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=7 mice/group). Statistical significance is indicated by * for p < 0.05 and ** for p < 0.01 compared to the vehicle group. Comparison between groups is shown by p-values or asterisks.

Butein treatment markedly ameliorated glucose intolerance, as evidenced by a significantly reduced mean AUC during OGTT in the butein group (35.7 ± 0.3) versus the vehicle group (57.3 ± 0.4) (Figure 1D and E). Additionally, butein intervention significantly attenuated fasting glucose concentrations (6.0 ± 0.9 vs 9.6 ± 1.2 mM) and circulating insulin levels (2.8 ± 0.3 vs 5.7 ± 1.0 µg/L), while concurrently improving insulin sensitivity as assessed by HOMA-IR index (0.7 ± 0.1 vs 2.4 ± 0.43) (Figure 1F–H). Altogether, these findings indicate that butein exhibits potential to reduce body weight and improve blood glucose regulation.

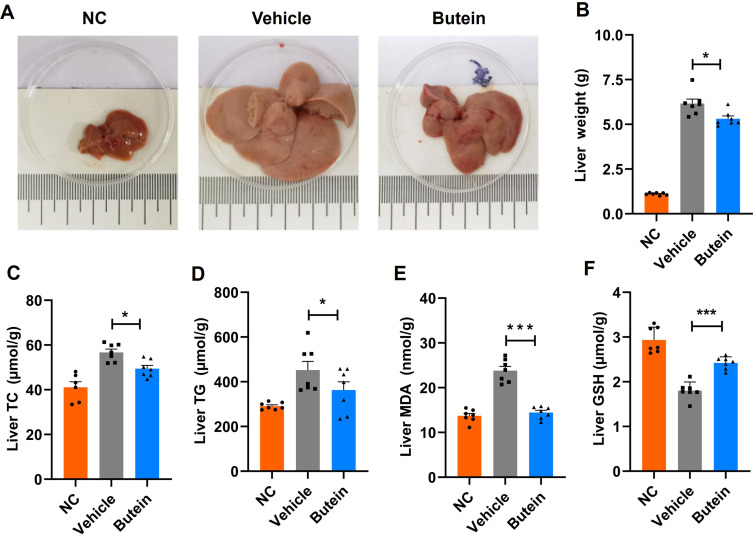

Butein Decreased Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Oxidative Stress

We next examined the effects of butein on hepatic lipid accumulation. The NC group mice fed a normal chow diet displayed dark-red liver appearance with normal liver mass (1.1 ± 0.0 g), whereas those in the vehicle group on a GAN diet exhibited enlarged and yellowish livers with a total liver mass 5.5-fold greater than the NC group. Treatment with butein significantly reduced liver mass (6.2 ± 0.3 vs 5.3 ± 0.2 g), total cholesterol (56.7 ± 1.5 vs 49.4 ± 1.4 µmol/g), and triglyceride levels (452.0 ± 38.7 vs 363.1 ± 36.7 µmol/g) compared to the vehicle group (Figure 2A–D). Furthermore, assessment of oxidative stress markers revealed that butein treatment significantly reduced MDA levels (23.8 ± 2.2 vs 14.3 ± 1.2 nmol/g) while concurrently elevating GSH concentrations (1.8 ± 0.1 vs 2.4 ± 0.1 µmol/g) compared to the vehicle group (Figure 2E and F). These results demonstrate that butein significantly attenuates GAN diet-induced lipid accumulation while improving hepatic health and enhancing antioxidant capacity.

Figure 2.

Butein decreased hepatic lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in GAN ob/ob mice. (A) Representative images of the liver. (B) Liver weight at necropsy (g). (C) Liver total cholesterol (TC) (µmol/g tissue). (D) Liver triglycerides (TG) (µmol/g tissue). (E) Liver malondialdehyde (MDA) (nmol/g tissue). (F) Liver glutathione (GSH) (µmol/g tissue). The data are expressed as mean ± SEM for 7 mice per group. *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001 compared to the vehicle group.

Butein Ameliorates Hepatic Steatosis, Inflammation and Fibrosis

To validate the protective effects of butein against hepatic steatosis and assess its influence on hepatic inflammation and fibrosis, histopathological analysis of liver tissues was conducted. H&E staining of liver sections showed extensive lipid droplet accumulation, inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning in the vehicle group, which were significantly alleviated by butein treatment (Figure 3, top row). To demonstrate lipid accumulation more clearly, we performed Oil Red O staining. The results demonstrated that GAN-diet promotes lipid accumulation in the liver, and this effect was reversed by butein treatment (Figure 3, middle row). The analysis of Oil Red O stained sections revealed that the lipid droplet area in the butein treatment was 55.5 ± 0.4%, lower than 67.9 ± 1.0% GAN-diet fed mouse livers, which was confirmed the ameliorates hepatic steatosis of butein (Supplementary Figure 1A).

Figure 3.

Butein mitigates steatohepatitis, inflammation and fibrosis in GAN ob/ob mice. Histological liver sections stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), Oil Red O, and Sirius Red across normal control, vehicle, and butein-treated mice. H&E staining (top row) displays cellular morphology; Oil Red O (middle row) visualizes lipid content; Sirius Red (bottom row) detects collagen. Scale bars = 100 µm.

The NAS score was used to assess the severity of NASH in mouse livers. Mice fed on GAN-diet with NAS score of 5.0 ± 0.2, comprising scores for steatosis (2.8 ± 0.2), ballooning (1.2 ± 0.2), and inflammation (1.3 ± 0.2). Butein treatment significantly reduced the NAS score to 2.2 ± 0.2 in GAN-diet fed mouse livers, with marked improvements in hepatocyte ballooning (0.3 ± 0.2) and inflammation (0.1 ± 0.0) (Supplementary Figure 1B–E).

Additionally, liver fibrosis was measured via Sirius Red staining, and the results indicated that GAN-induced liver fibrosis with extensive collagen fibers was reduced by butein treatment (Figure 3, bottom row). Butein treatment significantly reduced the collagen fiber area to 1.4 ± 0.4%, compared to 6.3 ± 0.8% in GAN-diet fed mouse livers (Supplementary Figure 1F). Collectively, these results confirmed the successful establishment of a NASH model in ob/ob mice using the GAN-diet. Based on this model, we found that butein effectively improves hepatic steatosis and significantly mitigates liver inflammation and fibrosis.

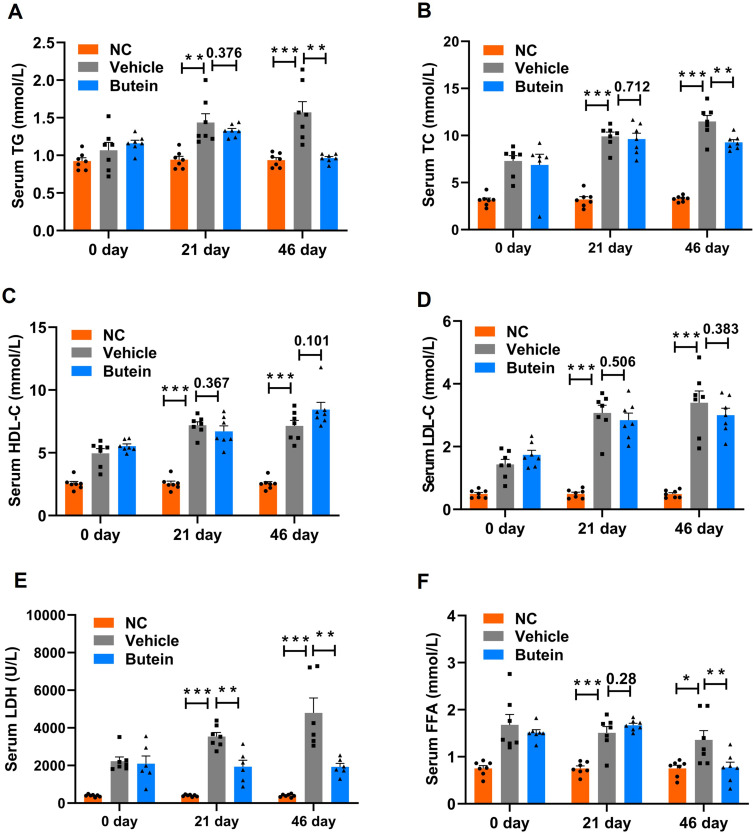

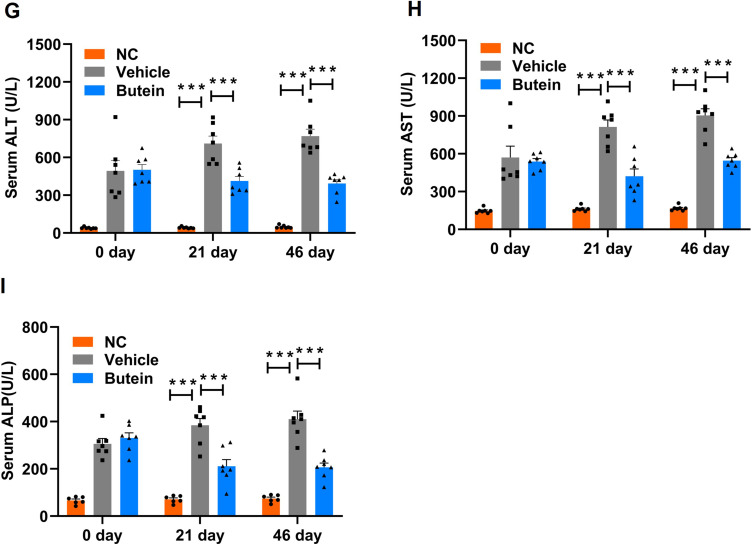

Butein Regulates Lipid Abnormalities and Alleviates Liver Injury

Overweight and obesity have been reported to enhance TG synthesis, disrupt lipid metabolism, and drive the progression of fatty liver diseases.30 As demonstrated in Figure 4A and B, circulating TG and TC concentrations were significantly elevated in mice maintained on the GAN diet relative to those fed normal chow at both day 21 and day 46 time points. Following 21 days of butein intervention, no statistically significant alterations in TG (p = 0.376) or TC (p = 0.712) levels were observed compared to the vehicle group; however, extended butein treatment for 46 days resulted in significant attenuation of both TG and TC concentrations relative to vehicle controls. Furthermore, comprehensive lipid profile analysis revealed that the vehicle group exhibited markedly elevated HDL-C, LDL-C, LDH, and FFA levels compared to the NC group at both experimental time points. Following 46 days of butein administration, significant reductions in LDH and FFA concentrations were observed, whereas HDL-C (p = 0.101) and LDL-C (p = 0.383) levels showed no statistically significant changes (Figure 4C–F).

Figure 4.

Continued.

Figure 4.

Serum biochemical parameters in GAN ob/ob mice. (A) Triglycerides (TG), (B) total cholesterol (TC), (C) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), (D) low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), (E) lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), (F) free fatty acids (FFA) (G), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), (H) aspartate aminotransferase (AST), (I) alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels at baseline 0 day, 21 days, and 46 days post-treatment with normal control, vehicle, and butein. Data represent mean ± SEM; *p<0.05 **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to the vehicle group. Comparison between groups is shown by p-values or asterisks.

Regarding the liver injury parameters, mice fed the GAN-diet exhibited higher ALT, AST, and ALP levels compared to normal chow-fed controls. Butein treatment significantly reduced ALT levels to 412.67 ± 46.03 U/L and 393.2 ± 29.76 U/L on days 21 and 46, respectively, versus 711.2 ± 67.8 U/L and 769.6 ± 59.1 U/L in GAN-diet fed mice (Figure 4G). Similarly, AST and ALP levels were markedly decreased following butein treatment (Figure 4H and I). Collectively, these findings suggest that butein partially mitigated the lipid disturbances induced by the GAN diet, and alleviated liver injury.

Butein Modulates Inflammatory Cytokines

Chronic liver injury can exacerbate inflammatory responses. In this study, serum inflammatory cytokines were assessed, revealing elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 in mice fed GAN-diet compared to the normal chow-fed controls. Following the administration of butein, the concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were significantly reduced to 489.9 ± 30.0 pg/mL, 75.1 ± 2.5 pg/mL and 58.4 ± 3.4 pg/mL, respectively, compared to 611.2 ± 16.3 pg/mL, 91.4 ± 2.7 pg/mL, and 69.1 ± 1.8 pg/mL in mice fed GAN-diet (Supplementary Figure 2A–C). Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was significantly elevated to 198.8 ± 11.5 pg/mL, compared to 172.7 ± 17.3 pg/mL in mice fed GAN-diet (Supplementary Figure 2D). These findings demonstrate that butein effectively mitigated the inflammatory response induced by the GAN-diet.

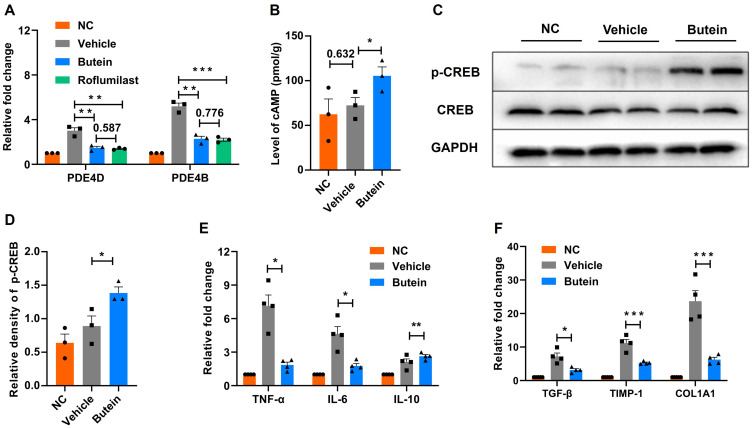

Butein Ameliorates NASH Potentially Through the cAMP Pathway

Previous studies have demonstrated that butein promotes lipolysis by inhibiting PDE in adipocytes.31 Therefore, this study aimed to explore whether the alleviating effects of butein on GAN diet-induced NASH in mice are mediated through PDE inhibition. Using RT-qPCR, the expression levels of PDE4D and PDE4B genes in liver tissues were quantified. In mice fed GAN-diet, expression levels of PDE4D and PDE4B were found to be 3.0 ± 0.4-fold and 5.2 ± 0.4-fold higher, respectively, than those observed in normal chow-fed controls. Treatment with butein downregulated the expression of PDE4D and PDE4B in the liver compared to GAN diet-fed mice. Furthermore, treatment with roflumilast, a PDE4 inhibitor, similarly resulted in significant downregulation of PDE4D and PDE4B gene expression levels compared to mice fed the GAN diet. When comparing butein and roflumilast treatments, no significant differences in PDE4D and PDE4B gene expression levels were observed (p = 0.587 and p = 0.776, respectively) (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Butein modulates PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathways in GAN ob/ob mice. (A) mRNA expression changes in phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) and phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B). (B) Levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in liver tissues. (C) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated cyclic AMP response element binding protein (p-CREB) relative to total CREB and GAPDH as a loading control. (D) Densitometry analysis of p-CREB normalized to total CREB. (E) mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6, and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. (F) mRNA expression of fibrosis-related genes transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1), and collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain (COL1A1). Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is denoted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to the vehicle group. Comparison between groups is shown by p-values or asterisks.

Cyclic AMP is a key intracellular second messenger in hormonal signaling.32 Butein, a cAMP-specific PDE inhibitor, has been shown to relax the rat aorta.33 In this study, we further investigated whether butein affects hepatic cAMP levels and p-CREB in GAN diet-induced mice, thereby modulating liver metabolism and alleviating NASH symptoms. cAMP levels showed no significant differences between GAN diet-fed mice and normal chow-fed controls (p = 0.632); however, they were significantly elevated in the butein-treated group (Figure 5B). Western blot analysis revealed stable CREB expression across all groups, while p-CREB levels were significantly elevated in the butein-treated group, reaching 1.6 ± 0.2 times the levels observed in the GAN diet-fed mice. (Figure 5C and D).

Furthermore, the expression levels of inflammatory and fibrogenic genes were analyzed in liver tissues. The butein group exhibited significant reductions in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (7.1 ± 0.8 vs 1.9 ± 0.2) and IL-6 (4.6 ± 0.6 vs 1.8 ± 0.2), alongside an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (2.1 ± 0.2 vs 2.6 ± 0.1) compared to the vehicle group (Figure 5E). Markers of liver fibrosis were also significantly decreased in the butein group compared to the vehicle group, including TGF-β (7.2 ± 0.9 vs 3.2 ± 0.3), TIMP-1 (11.2 ± 1.0 vs 5.3 ± 0.2), and COL1A1 (23.7 ± 2.7 vs 6.3 ± 0.6) (Figure 5F). Collectively, these data suggest that butein mitigates liver damage, particularly targeting inflammation and fibrosis, potentially through modulation of the PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathway.

Correlation Between Hepatic Triglycerides and Inflammation/Fibrosis Gene Expression

Correlation analysis revealed significant positive associations between hepatic TG content and the expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α), with elevated TG levels being concomitant with increased expression of IL-6 and TNF-α, suggesting activation of pro-inflammatory pathways. Despite IL-10 functioning as an anti-inflammatory cytokine, its positive correlation with TG content may indicate a compensatory response to mitigate persistent inflammation. Additionally, rising TG levels were associated with upregulation of fibrosis-related genes such as COL1A1, TGF-β, and TIMP-1, suggesting that lipid accumulation may contribute to hepatic fibrosis through the transcriptional activation of these genes (Supplementary Figure 3). Collectively, these findings highlight lipid metabolic dysfunction as a critical factor in the pathogenesis of both hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.

Butein Mitigates PA-Induced Lipid and Oxidative Stress in HepG2 Cells

Based on these findings, we confirmed that butein significantly improves GAN diet-induced NASH in ob/ob mice, likely through PDE4 inhibition and cAMP elevation. To further explore its translational potential, we examined its effects in a human cell-based liver injury model. Through the PA-induced lipid and oxidative stress model in HepG2 cells, extensive red lipid droplet accumulation was observed compared to the control group. Treatment with butein significantly reduced the lipid droplet area, highlighting its ability to alleviate lipid accumulation (Figure 6A). Furthermore, butein treatment markedly decreased ALT, AST, TG, TC, and LDH levels while significantly increasing SOD activity compared to cells treated with PA alone (Figure 6B–G). These results indicate that butein effectively mitigates PA-induced lipid accumulation and enhances the antioxidative capacity of HepG2 cells.

Figure 6.

Cellular steatosis and hepatocyte injury markers after butein treatment in palmitic acid (PA)-induced HepG2 cells. (A) Representative images of Oil Red O-stained HepG2 cells under control conditions, with PA induction, and PA induction followed by butein treatment. Butein mitigates lipid accumulation as visualized by decreased Oil Red O staining. (B–D) Enzymatic activity of ALT, AST, and TG within hepatocytes, respectively, indicating reduced hepatocellular injury and steatosis upon butein treatment. (E–G) Measurements of TC, LDH, and SOD in HepG2 cells, where butein demonstrates protective effects against PA-induced oxidative stress. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is denoted as **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the PA group.

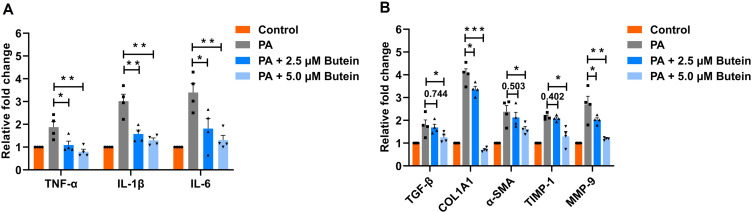

Butein Suppresses PA-Induced Inflammatory and Fibrotic Responses in LX-2 Cells

LX-2 cells are widely used as a representative in vitro model for studying liver inflammation and fibrosis.34–36 Treatment with butein at concentrations of 2.5 µM and 5 µM significantly downregulated the expression of inflammatory genes (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) compared to the PA-treated group. Specifically, for TNF-α expression, treatment with 2.5 µM butein resulted in significant suppression (p = 0.0424), while 5 µM butein achieved greater inhibition (p = 0.0079). Similarly, IL-1β expression was significantly reduced following treatment with 2.5 µM butein (p = 0.0065) and 5 µM butein (p = 0.0019). For IL-6, both 2.5 µM (p = 0.037) and 5 µM (p = 0.0014) butein treatments demonstrated significant downregulation compared to the PA-treated group (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Gene expression analysis in PA-treated LX-2 cells with butein administration. (A) mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines cells (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) show a dose-dependent decrease in expression with butein treatment. (B) Gene expression of fibrosis markers (TGF-β, COL1A1, α-SMA, TIMP-1, MMP-9) indicates that butein modulates the fibrogenic response in a dose-responsive manner, affirming its anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is denoted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the PA group. Comparison between groups is shown by p-values or asterisks.

Furthermore, butein treatment markedly suppressed the expression of fibrosis markers, including TGF-β, COL1A1, α-SMA, TIMP-1, and MMP-9, relative to the PA-treated group. TGF-β expression showed no significant change with 2.5 µM butein treatment (p = 0.744) but was significantly reduced with 5 µM butein (p = 0.047). COL1A1 expression was significantly downregulated by both 2.5 µM (p = 0.039) and 5 µM (p < 0.001) butein treatments. α-SMA expression remained unchanged following 2.5 µM butein treatment (p = 0.502) but was significantly suppressed with 5 µM butein (p = 0.039). TIMP-1 and MMP-9 exhibited similar expression patterns to the aforementioned genes (Figure 7B). These findings indicate that butein ameliorates PA-induced cellular damage by suppressing the expression of inflammatory and fibrotic marker genes. The protective effects of butein on gene expression were dose-dependent, with 5 µM butein demonstrating superior inhibitory activity compared to 2.5 µM treatment.

Discussion

The growing prevalence and serious impact of NASH have made it a pressing global health issue, highlighting the urgent need for effective therapeutic interventions. Currently, resmetirom is the only FDA-approved treatment for NASH; however, therapeutic options remain limited. In this study, we investigated the efficacy of butein in alleviating NASH in ob/ob mice induced by a GAN diet. Our findings suggest that butein supplementation may offer therapeutic potential for preventing diet-induced NASH.

Butein has been shown to protect against NAFLD in rats fed an MCD diet.23 Although the MCD diet is widely used for its rapid induction of NAFLD, it has significant limitations, including reduced body weight and a metabolic profile inconsistent with human NASH.37,38 To address these limitations, we employed the GAN diet model, which closely mimics key phenotypic and mechanistic features of human NASH.39–41 Additionally, we utilized older ob/ob mice (24 weeks), which are more susceptible to developing NASH under similar conditions compared to younger mice.42,43 Using this approach, we successfully established a NASH model characterized by lipid metabolism disorders, liver inflammation, and hepatic fibrosis. However, there are still several limitations that should be considered. The study duration was limited to 46 days, which was sufficient for inducing NASH but insufficient for evaluating long-term effects, particularly concerning advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. Longer-term studies are essential to assess the sustained impact of butein. Furthermore, although the GAN diet-induced ob/ob mouse model is relevant, NASH is a heterogeneous disease, with its pathology varying across genetic backgrounds and dietary conditions. Therefore, future studies should include additional models to comprehensively explore butein’s therapeutic potential.

Our study found that butein controls weight gain in NASH mice without suppressing food intake, offering an advantage over therapies like GLP-1 receptor agonists, which often cause appetite suppression.44 As indicated by our study, butein may alleviate NASH by modulating the PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathway, whereas Resmetirom improves hepatic lipid metabolism by activating thyroid hormone receptor-β, thereby reducing hepatic steatosis.45 Given the close association between NASH and insulin resistance, butein’s ability to regulate blood glucose, enhance insulin sensitivity, and reduce TG synthesis suggests its broader metabolic benefits.46 In contrast to Resmetirom, which primarily targets hepatic lipid regulation, butein may offer more comprehensive effects on systemic metabolic dysfunction.47 Furthermore, the administration of a single dose of butein in this study suggests the need for further investigation into its dose-dependent effects, as this could provide valuable insights for optimizing the therapeutic regimen and assessing the long-term efficacy in the context of NASH.

Butein’s therapeutic effects on NASH are primarily reflected in its ability to alleviate liver inflammation and fibrosis. These pathological features are closely associated with hepatic lipid accumulation and excessive depletion of GSH.48 In this study, butein effectively reduced the increase in TG and TC induced by a GAN diet, mitigating the stress response caused by lipid accumulation in the liver. Butein demonstrated selective lipid modulation, reducing serum TG, TC, LDH, and FFA levels while HDL-C and LDL-C remained unaltered. This selectivity indicates preferential targeting of hepatic lipid synthesis pathways rather than systemic cholesterol transport, potentially involving the PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathway. Notably, the CREB coactivator transcription coactivator 2 (CRTC2) plays a pivotal role in hepatic lipid metabolism by regulating sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1), a key insulin-responsive transcription factor that upregulates genes involved in hepatic fatty acid and TG biosynthesis, thus being integral to de novo lipogenesis.49,50 Alternatively, the unchanged cholesterol profile may reflect study duration limitations, as cholesterol homeostasis requires prolonged intervention periods. Additionally, butein reduced MDA levels and increased GSH, thereby effectively mitigating oxidative damage to the liver caused by lipid peroxidation and free radicals.

In addition to its beneficial effects observed in GAN diet-induced NASH mouse models, butein’s efficacy was further validated in a human cell model. In PA-induced HepG2 cells, butein significantly reduced levels of TG, TC, SOD, ALT, and AST, effectively mitigating lipid accumulation and oxidative stress-induced liver damage. These findings align with its effects observed in our NASH mouse model, reinforcing its potential as a therapeutic agent. Additionally, since hepatic stellate cells are key drivers of liver fibrosis,51 butein’s ability to suppress the expression of inflammation- and fibrosis-related genes in LX-2 cells further supports its antifibrotic properties and therapeutic relevance for NASH treatment.

Butein has been reported as a known PDE inhibitor capable of reduces cAMP hydrolysis.31,33 Elevated cAMP activates protein kinase A, leading to CREB phosphorylation. Phosphorylated CREB suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines, modulates macrophages and Kupffer cells, and inhibits activation, reducing fibrosis by decreasing TGF-β and collagen production for extracellular matrix degradation.52–54 Our findings demonstrate that butein significantly reduced hepatic PDE4D and PDE4B expression, increased cAMP and phosphorylated CREB levels, and downregulated pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6) and profibrotic (TGF-β, TIMP and COL1A1) genes in mouse liver. Critically, the validation of this mechanism is strengthened by comparative analysis with roflumilast, a selective PDE4 inhibitor clinically approved for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatment.55 Both butein and roflumilast achieved comparable downregulation of PDE4D and PDE4B expression levels, providing compelling pharmacological evidence for shared mechanistic targets and confirming that butein’s therapeutic effects are primarily mediated through PDE4 inhibition rather than non-specific anti-inflammatory actions.

While these findings demonstrate correlation between butein treatment and PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathway modulation, establishing definitive causation requires additional mechanistic validation through pathway-specific knockout models and rescue experiments. Beyond this mechanism, butein’s antioxidant properties may function through dual pathways: upstream by activating Nrf2/ARE signaling to reduce oxidative stress-induced PDE4 expression and downstream by protecting cAMP-responsive anti-inflammatory mediators from oxidative degradation.29,56,57 This dual antioxidant and cAMP signaling integration suggests a network-based therapeutic approach that requires further investigation to optimize butein’s therapeutic potential.

Based on these mechanistic insights and the promising preclinical results, further studies are crucial to fully assess butein’s translational potential in NASH therapy. Long-term animal models are needed to evaluate its sustained efficacy and potential in preventing fibrosis. Combination studies with other therapies, like GLP-1 receptor agonists or Resmetirom, could optimize treatment strategies. For the first-in-human clinical trial, a diverse patient population across NASH stages should be included, with endpoints focused on liver function, fat content, and metabolic markers. Safety monitoring and a dose-escalation strategy will be essential for determining the optimal dose. These studies will provide key data for butein’s clinical development in NASH.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the significant therapeutic potential of butein in treating NASH, primarily through its effects on glucolipid metabolism, hepatic inflammation, and fibrosis. A key finding is the modulation of the PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB pathway, advancing our understanding of NASH and supporting the development of targeted therapies. Future preclinical studies should focus on long-term efficacy, safety, and combination therapies, while first-in-human clinical trials should prioritize diverse patient populations and safety monitoring.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the invaluable and enthusiastic contributions of Zhang laboratory members.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073909); the Shanxi Province Higher Education “Billion Project” Science and Technology Guidance Project (BYJL024); the basic Research Plan in Shanxi Province of China (No. 20210302124584); the Special Fund from Medicinal Basic Research Innovation Center of Chronic Kidney Disease, Ministry of Education, Shanxi Medical University (No. CKD/SXMU-2024-01); the Shanxi Provincial Central Leading Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project (YDZJSX20231A059, YDZJSX2022A059); Four “Batches” Innovation Project of Invigorating Medical through Science and Technology of Shanxi Province (2023XM022); the Shanxi Provincial of Transformation projects of scientific and technological achievements (202304016); the Shanxi Medical University Research Initiation Grant for Doctoral Scholars (No. XD2119).

Highlights

Butein improves glucolipid metabolism in GAN diet-induced NASH mice.

It reduces hepatic inflammation and fibrosis significantly.

Butein modulates the PDE4/cAMP/p-CREB signaling pathways.

Decreases lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in hepatocytes.

Abbreviations

α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; COL1A1, type 1 collagen α; FBS, fasting blood glucose; FFA, free fatty acids; FINS, fasting insulin; GAN, Gubra amylase NASH; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-10, interleukin-10; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MDA, malondialdehyde; MMP-9, matrix metallopeptidase-9; NAS, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease activity score; NC, normal chow; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; PA, palmitic acid; PDE4B, phosphodiesterase 4B; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Ethics Approval

The animal study protocol was approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethical Committee of Shanxi Medical University (Approval No. SCXK2020-0008). The use of animals conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Shanxi Medical University (GBT 35892-2018).

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that no potential conflict of interest that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, et al. Endpoints and clinical trial design for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):344–353. doi: 10.1002/hep.24376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobbina E, Akhlaghi F. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)–pathogenesis, classification, and effect on drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Drug Metab Rev. 2017;49(2):197–211. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2017.1293683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Mauro S, Scamporrino A, Filippello A, et al. Clinical and molecular biomarkers for diagnosis and staging of NAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11905. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith A, Baumgartner K, Bositis C. Cirrhosis: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(12):759–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alshehade SA. Resmetirom’s approval: highlighting the need for comprehensive approaches in NASH therapeutics. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2024;48(7):102377. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2024.102377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keam SJ. Resmetirom: first Approval. Drugs. 2024;84(6):729–735. doi: 10.1007/s40265-024-02045-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kravchuk S, Bychkov M, Kozyk M, Strubchevska O, Kozyk A. Managing metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in the digital era: overcoming barriers to lifestyle change. Cureus. 2025;17(5):e84803. doi: 10.7759/cureus.84803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratziu V, Francque S, Sanyal A. Breakthroughs in therapies for NASH and remaining challenges. J Hepatol. 2022;76(6):1263–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padmavathi G, Roy NK, Bordoloi D, et al. Butein in health and disease: a comprehensive review. Phytomedicine. 2017;25:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ansari MY, Ahmad N, Haqqi TM. Butein activates autophagy through AMPK/TSC2/ULK1/mTOR pathway to inhibit IL-6 expression in IL-1β stimulated human chondrocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;49(3):932–946. doi: 10.1159/000493225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gay NH, Suwanjang W, Ruankham W, et al. Butein, isoliquiritigenin, and scopoletin attenuate neurodegeneration via antioxidant enzymes and SIRT1/ADAM10 signaling pathway. RSC Adv. 2020;10(28):16593–16606. doi: 10.1039/C9RA06056A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S, Yoon H, Park S-K. Butein increases resistance to oxidative stress and lifespan with positive effects on the risk of age-related diseases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxidants. 2024;13(2):155. doi: 10.3390/antiox13020155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehman M, Chaudhary R, Rajput S, et al. Butein ameliorates chronic stress induced atherosclerosis via targeting anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic and BDNF pathways. Physiol Behav. 2023;267:114207. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2023.114207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sulaiman S, Arafat K, Al-Azawi AM, AlMarzooqi NA, Lootah SNAH, Attoub S. Butein and frondoside-A combination exhibits additive anti-cancer effects on tumor cell viability, colony growth, and invasion and synergism on endothelial cell migration. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23(1):431. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tungalag T, Park KW, Yang DK. Butein ameliorates oxidative stress in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts through activation of the NRF2 signaling pathway. Antioxidants. 2022;11(8):1430. doi: 10.3390/antiox11081430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao L, Zhang W, Luan F, et al. Butein suppresses PD-L1 expression via downregulating STAT1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;157:114030. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo SW, Lee SH, Kang H-C, et al. Butein suppresses myofibroblastic differentiation of rat hepatic stellate cells in primary culture. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55(3):347–352. doi: 10.1211/002235702658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SH, Nan J-X, Zhao YZ, et al. The chalcone butein from Rhus verniciflua shows antifibrogenic activity. Planta Med. 2003;69(11):990–994. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubota N, Kado S, Kano M, et al. A high‐fat diet and multiple administration of carbon tetrachloride induces liver injury and pathological features associated with non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40(7):422–430. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuchida T, Lee YA, Fujiwara N, et al. A simple diet- and chemical-induced murine NASH model with rapid progression of steatohepatitis, fibrosis and liver cancer. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phung HH, Lee CH. Mouse models of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and their application to new drug development. Arch Pharm Res. 2022;45(11):761–794. doi: 10.1007/s12272-022-01410-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eng JM, Estall JL. Diet-induced models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: food for thought on sugar, fat, and cholesterol. Cells. 2021;10(7):1805. doi: 10.3390/cells10071805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alshammari GM, Balakrishnan A, Chinnasamy T. Butein protects the nonalcoholic fatty liver through mitochondrial reactive oxygen species attenuation in rats. Biofactors. 2018;44(3):289–298. doi: 10.1002/biof.1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Herck M, Vonghia L, Francque S. Animal models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—A starter’s guide. Nutrients. 2017;9(10):1072. doi: 10.3390/nu9101072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z, Qin X, Yi T, et al. Gubra amylin‐NASH diet induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with histological damage, oxidative stress, immune disorders, gut microbiota, and its metabolic dysbiosis in colon. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2024;68(15):e2300845. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202300845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flensted-Jensen M, Oró D, Rørbeck EA, et al. Dietary intervention reverses molecular markers of hepatocellular senescence in the GAN diet-induced obese and biopsy-confirmed mouse model of NASH. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12876-024-03141-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C, Liu M, Tao X. Targeting phosphodiesterase 4 in gastrointestinal and liver diseases: from isoform-specific mechanisms to precision therapeutics. Biomedicines. 2025;13(6):1283. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines13061285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Möllmann J, Kahles F, Lebherz C, et al. The PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast reduces weight gain by increasing energy expenditure and leads to improved glucose metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(4):496–508. doi: 10.1111/dom.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zahra N, Rafique S, Naveed Z, et al. Regulatory pathways and therapeutic potential of PDE4 in liver pathophysiology. Life Sci. 2024;345:122565. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee E, Korf H, Vidal-Puig A. An adipocentric perspective on the development and progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2023;78(5):1048–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuppusamy U, Das N. Effects of flavonoids on cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase and lipid mobilization in rat adipocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44(7):1307–1315. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90531-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wahlang B, McClain C, Barve S, Gobejishvili L. Role of cAMP and phosphodiesterase signaling in liver health and disease. Cell Signal. 2018;49:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu S-M, Cheng Z-J, Kuo S-C. Endothelium-dependent relaxation of rat aorta by butein, a novel cyclic AMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;280(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00190-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang F, Chen L, Kong D, et al. Canonical Wnt signaling promotes HSC glycolysis and liver fibrosis through an LDH-A/HIF-1α transcriptional complex. Hepatology. 2024;79(3):606–623. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaul S, Leszczynska A, Alegre F, et al. Hepatocyte pyroptosis and release of inflammasome particles induce stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2021;74(1):156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim KE, Lee J, Shin HJ, et al. Lipocalin-2 activates hepatic stellate cells and promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in high-fat diet-fed Ob/Ob mice. Hepatology. 2023;77(3):888–901. doi: 10.1002/hep.32569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Wang TX, Huang X, et al. Targeting ferroptosis alleviates methionine‐choline deficient (MCD)‐diet induced NASH by suppressing liver lipotoxicity. Liver Int. 2020;40(6):1378–1394. doi: 10.1111/liv.14428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu B, Li H, Lu B, et al. Indole supplementation ameliorates MCD-induced NASH in mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2022;107:109041. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2022.109041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen HH, Pors S, Andersen MW, et al. Semaglutide reduces tumor burden in the GAN diet-induced obese and biopsy-confirmed mouse model of NASH-HCC with advanced fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):23056. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-50328-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Møllerhøj MB, Veidal SS, Thrane KT, et al. Hepatoprotective effects of semaglutide, lanifibranor and dietary intervention in the GAN diet‐induced obese and biopsy‐confirmed mouse model of NASH. Clin Transl Sci. 2022;15(5):1167–1186. doi: 10.1111/cts.13235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen HH, Ægidius HM, Oro D, et al. Human translatability of the GAN diet-induced obese mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s12876-020-01356-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang B, Zhu X, Yu S, et al. Roflumilast ameliorates GAN diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by reducing hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in ob/ob mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024;722:150170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Lu Y, Liang X, et al. A new NASH model in aged mice with rapid progression of steatohepatitis and fibrosis. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0286257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trapp S, Brierley DI. Brain GLP-1 and the regulation of food intake: GLP-1 action in the brain and its implications for GLP-1 receptor agonists in obesity treatment. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179(4):557–570. doi: 10.1111/bph.15638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freund ME, van der Most F, Groeneweg S, van Geest FS, Visser WE. Thyroid hormone analogs: recent developments. Thyroid. 2025. doi: 10.1089/thy.2025.0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakurai Y, Kubota N, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T. Role of insulin resistance in MAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):4156. doi: 10.3390/ijms22084156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn W, Alkhouri N. Resmetirom for steatotic liver disease: does data support widespread use? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2025;27(1):53. doi: 10.1007/s11894-025-01002-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sui Y, Geng X, Wang Z, Zhang J, Yang Y, Meng Z. Targeting the regulation of iron homeostasis as a potential therapeutic strategy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2024;157:155953. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2024.155953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Han J, Li E, Chen L, et al. The CREB coactivator CRTC2 controls hepatic lipid metabolism by regulating SREBP1. Nature. 2015;524(7564):243–246. doi: 10.1038/nature14557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Viscarra J, Kim S-J, Sul HS. Transcriptional regulation of hepatic lipogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(11):678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm4074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao S, Zhu Q, Lee WH, et al. The adiponectin-PPARgamma axis in hepatic stellate cells regulates liver fibrosis. Cell Rep. 2025;44(1):115165. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.115165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li G, Jiang Q, Xu K. CREB family: a significant role in liver fibrosis. Biochimie. 2019;163:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee EJ, Hwang I, Lee JY, et al. Hepatic stellate cell-specific knockout of transcriptional intermediary factor 1 gamma aggravates liver fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2020;217(6):e20190402. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravnskjaer K, Madiraju A, Montminy M. Role of the cAMP pathway in glucose and lipid metabolism. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2016;233:29–49. doi: 10.1007/164_2015_32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crocetti L, Floresta G, Cilibrizzi A, Giovannoni MP. An overview of PDE4 inhibitors in clinical trials: 2010 to early 2022. Molecules. 2022;27(15):4964. doi: 10.3390/molecules27154964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee DS, Jeong GS. Butein provides neuroprotective and anti‐neuroinflammatory effects through Nrf2/ARE‐dependent haem oxygenase 1 expression by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(19):2894–2909. doi: 10.1111/bph.13569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lugnier C. The complexity and multiplicity of the specific cAMP phosphodiesterase family: PDE4, open new adapted therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10616. doi: 10.3390/ijms231810616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]